Sergeant James 'Jock' Masterton

2986215 Sergeant James Masterton MM was serving with A' Company, 2nd battalion the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in Malaya just before the fall of Singapore in 1942. Brought up in the village of Doune near Stirling, James worked as a costing clerk with W. Alexander and Sons, before joining the Army in 1939.

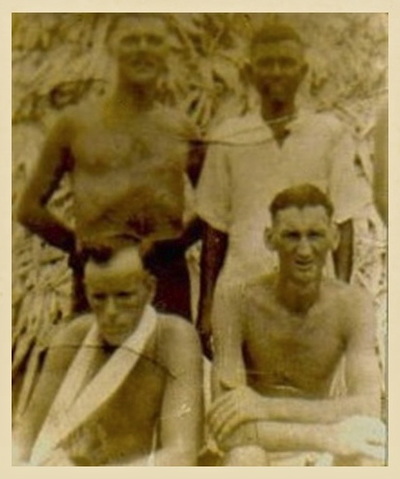

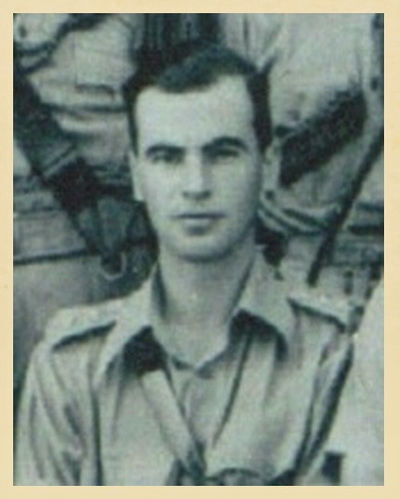

As it became clear to James (pictured left at Port Dickson, Malaya in 1941) that the Japanese were closing in on Singapore and that being taken prisoner was inevitable, he and 13 other men decided to make a run for freedom. They stole an old Chinese ‘junk’ and set sail for Sumatra with the intentions of making for Allied held territory, this was to become a well-used pathway for soldiers attempting to escape impending imprisonment by the all-conquering Japanese Army. Very few succeeded.

It is not clear how far James and the other men managed to travel under their own steam back then, but they were eventually rescued by an Allied Naval Destroyer in the Indian Ocean. They were transported to the port of Colombo, Ceylon.

Having been extremely fortunate to survive the dramas of his escape from Singapore, James spent some time in hospital in Ceylon recovering from his ordeal. He then was transferred to the Seaforth Highlanders Regiment and took up a staff posting in India. It must have been from here that he decided to join the new Chindit force, which were training in the Central Provinces of India. He was posted into Wingate’s Brigade Head Quarters and became the Cipher Sergeant under the command of Lieutenant ‘Willie’ Wilding.

From Lt. Wilding's written memoir:

The Brigade was camped out about three miles from Saugor railway station and there I met my Cipher Sergeant, James Masterton. As he was a Scotsman he was known as Jock, but to me he was always simply 'Sergeant' and this he remained until after the war. He was a splendid chap who had escaped form Singapore in 1942. Apparently some legalistic idiot had accused him of being a deserter, on the crazy grounds that he and the others with him had escaped Singapore before the actual surrender. Thankfully, some sensible chap had sorted things out to the great advantage of 77 Brigade in general and me in particular. Jock always maintains that my first words to him were: Hello Sergeant, catch that bloody mule will you. He may well be right. Alas, I have now lost touch with him.

Not much is known about Masterton and his actual experiences on Operation Longcloth apart from what is written about Wingate’s own time in 1943. James was last seen as a free man on 30th April that year, as Brigade HQ split up into 5 dispersal groups on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. He was taken prisoner on the 11th May, after nearly two weeks spent trying to cross that great watery obstacle. He would have been in poor physical condition by this time as food and decent drinking water were very hard to come by. It is highly likely that James would have been part of the dispersal group led by Lieutenant Wilding and Captain Graham Hosegood, although this cannot be confirmed at this time.

So having made one miraculous escape from the Japanese the year before, James could not repeat the trick a second time and now found himself a POW after all. He was to spend the next two years in Rangoon Jail with the POW number of 114. After a spell in solitary confinement he moved into Block 6 in the jail, which was full of other Longcloth prisoners. He went to work in the makeshift hospital in the jail and under the medical officers his sterling efforts helped keep many Chindits going through those terrible times.

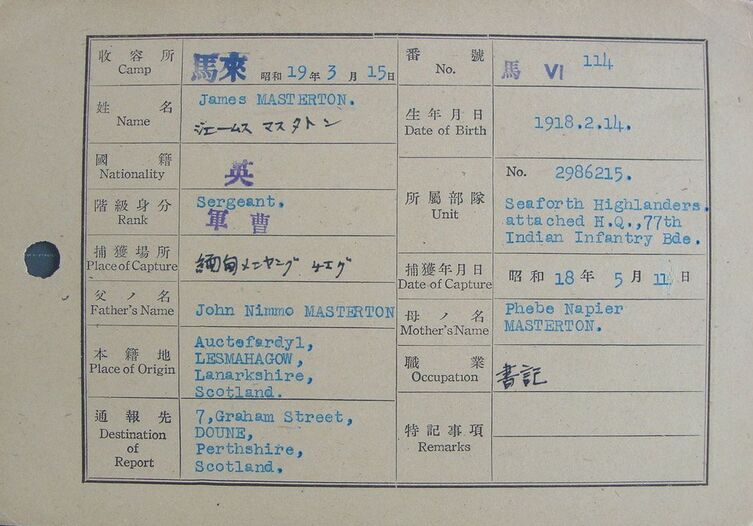

Seen below is an image of James' POW index card, showing such details as his date of capture, Army number and next of kin details.

As it became clear to James (pictured left at Port Dickson, Malaya in 1941) that the Japanese were closing in on Singapore and that being taken prisoner was inevitable, he and 13 other men decided to make a run for freedom. They stole an old Chinese ‘junk’ and set sail for Sumatra with the intentions of making for Allied held territory, this was to become a well-used pathway for soldiers attempting to escape impending imprisonment by the all-conquering Japanese Army. Very few succeeded.

It is not clear how far James and the other men managed to travel under their own steam back then, but they were eventually rescued by an Allied Naval Destroyer in the Indian Ocean. They were transported to the port of Colombo, Ceylon.

Having been extremely fortunate to survive the dramas of his escape from Singapore, James spent some time in hospital in Ceylon recovering from his ordeal. He then was transferred to the Seaforth Highlanders Regiment and took up a staff posting in India. It must have been from here that he decided to join the new Chindit force, which were training in the Central Provinces of India. He was posted into Wingate’s Brigade Head Quarters and became the Cipher Sergeant under the command of Lieutenant ‘Willie’ Wilding.

From Lt. Wilding's written memoir:

The Brigade was camped out about three miles from Saugor railway station and there I met my Cipher Sergeant, James Masterton. As he was a Scotsman he was known as Jock, but to me he was always simply 'Sergeant' and this he remained until after the war. He was a splendid chap who had escaped form Singapore in 1942. Apparently some legalistic idiot had accused him of being a deserter, on the crazy grounds that he and the others with him had escaped Singapore before the actual surrender. Thankfully, some sensible chap had sorted things out to the great advantage of 77 Brigade in general and me in particular. Jock always maintains that my first words to him were: Hello Sergeant, catch that bloody mule will you. He may well be right. Alas, I have now lost touch with him.

Not much is known about Masterton and his actual experiences on Operation Longcloth apart from what is written about Wingate’s own time in 1943. James was last seen as a free man on 30th April that year, as Brigade HQ split up into 5 dispersal groups on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. He was taken prisoner on the 11th May, after nearly two weeks spent trying to cross that great watery obstacle. He would have been in poor physical condition by this time as food and decent drinking water were very hard to come by. It is highly likely that James would have been part of the dispersal group led by Lieutenant Wilding and Captain Graham Hosegood, although this cannot be confirmed at this time.

So having made one miraculous escape from the Japanese the year before, James could not repeat the trick a second time and now found himself a POW after all. He was to spend the next two years in Rangoon Jail with the POW number of 114. After a spell in solitary confinement he moved into Block 6 in the jail, which was full of other Longcloth prisoners. He went to work in the makeshift hospital in the jail and under the medical officers his sterling efforts helped keep many Chindits going through those terrible times.

Seen below is an image of James' POW index card, showing such details as his date of capture, Army number and next of kin details.

It is rumoured that James Masterton was also one of the top men in Rangoon for laying his hands on the contraband goods that were used to help supplement the poor diet of plain polished rice. He would beg or even steal these items while out in the city on working parties, right under the noses of the Japanese guards and if caught would pay a heavy price in the shape of a severe beating.

Masterton was one of the so-called ‘fit’ men who were chosen to march out of the jail in late April 1945. This group have become known by researchers as the Pegu marchers (see the Chindit POW’s page). After liberation in early May, Masterton was one of four men chosen to take part in a radio interview set up by the Red Cross in Rangoon. Here is a section of the transmission involving his views on food in the jail:

When asked about the type and quantity of food, he his answer was:

“Well, it was worst when we first went in, in solitary confinement for six or seven weeks, while we were being questioned. At that stage we only got three meals a day. And they were like this. In the morning a cupful of rice and half a cupful of a kind of porridge, made out of rice husks."

NB. This porridge was called ‘nuka’ within the jail, it was a foul tasting paste, but provided the POW’s with a vital intake of vitamin B, which helped stave off beri beri.

He went on: “In the middle of the day another cupful of rice and what you might call soup." (This was pumpkin, marrow and any green leaves available around the jail, boiled and served as a liquid). James continues: “Then in the evening we got another cupful of rice and sometimes a bit of meat, about an inch square. That happened once or twice a week-if we were lucky."

He hints at the black market trade in Rangoon and perhaps his involvement within it with his last quote on the subject of food. When asked if the food was better in solitary or when he lived in Block 6, he answered: “Well I suppose the food was much the same, but at least we were able to share it (in Block 6) and a few extras did come in."

On return to the United Kingdom James spent a period of time in a military hospital, where he was treated for all the medical complaints accrued from two years in Rangoon, these included malaria and jungle sores.

Jim Masterton at the Taj Mahal Gardens in 1942.

Jim Masterton at the Taj Mahal Gardens in 1942.

Update 08/08/2012

I have recently made contact with Gordon Masterton who is compiling the wider Masterton family tree. Here is what he had to say on finding this new addition to his research:

Steve, what an excellent website, and I've only just touched a part of it. I am researching Mastertons worldwide, and have a website with information gathered to date. Sergeant James "Jock" Masterton is one of the branches I've labelled "Biggar Mastertons" because of their first appearance in the records around that geographical area. Before seeing your site I hadn't been aware of him but I had two other siblings in his family (there are probably more) and a pedigree that goes back to mid 18th century.

I have found some details of his later life. He married in Stirling in 1947, his bride was a Margaret McMartin Neill, but she died at the age of only 43 of a coronary occlusion in 1961. When he died he was at an address that looks like he was visiting an uncle. His death certificate is posted on the website on his genealogy page.

Please click on the links below for more updated details and some fantastic photographs of James. My great thanks go to Gordon for this new information about Jim Masterton.

http://www.themastertons.org/james-masterton-chindit-POW.html

http://www.themastertons.org/genealogy_tng/showmedia.php?mediaID=1284&albumlinkID=187

I have recently made contact with Gordon Masterton who is compiling the wider Masterton family tree. Here is what he had to say on finding this new addition to his research:

Steve, what an excellent website, and I've only just touched a part of it. I am researching Mastertons worldwide, and have a website with information gathered to date. Sergeant James "Jock" Masterton is one of the branches I've labelled "Biggar Mastertons" because of their first appearance in the records around that geographical area. Before seeing your site I hadn't been aware of him but I had two other siblings in his family (there are probably more) and a pedigree that goes back to mid 18th century.

I have found some details of his later life. He married in Stirling in 1947, his bride was a Margaret McMartin Neill, but she died at the age of only 43 of a coronary occlusion in 1961. When he died he was at an address that looks like he was visiting an uncle. His death certificate is posted on the website on his genealogy page.

Please click on the links below for more updated details and some fantastic photographs of James. My great thanks go to Gordon for this new information about Jim Masterton.

http://www.themastertons.org/james-masterton-chindit-POW.html

http://www.themastertons.org/genealogy_tng/showmedia.php?mediaID=1284&albumlinkID=187

Lance-Sergeant William Royle

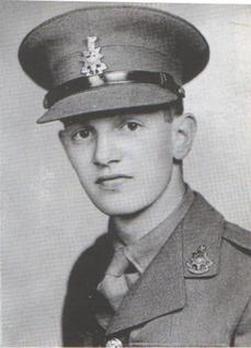

William Royle (pictured left, probably in India in 1942) found himself part of Column 7 on Operation Longcloth in 1943, he was promoted on or just before the trip into Burma to Lance Sergeant and therefore would have led at least a section of troops during the expedition. Originally from Sale in Lancashire, William was one of the older men on the operation, aged 32.

In late March 1943, Wingate called a halt to the operation in Burma, after being instructed by the Army HQ in India to get as many of his now knowledgeable and experienced Chindit Brigade back safely to Allied territory. Wingate's HQ Brigade had been shielded by columns 7 and 8 for most of the operation in 1943 and it was these three groups that found themselves on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March that year.

Close to the Burmese town of Inywa was chosen as the river crossing point by the column commanders, Ken Gilkes and Water Purcell Scott. As the men prepared to cross some enemy activity was seen on the far bank. Wingate and his commanders felt that the Japanese posed little threat in their present numbers, and so pressed on with the crossing. Some lead boats did manage to get over, but others came under heavy mortar and machine gun fire and began to get into difficulties. One such boat contained William Royle, alongside William was Northern Section Adjutant, Captain David Hastings, Corporal Harold Hodkinson and Ptes. James Baker and Edward Kitchen. This boat was struggling to make the western bank and was continuously under heavy fire from the Japanese positions. From some eye witness accounts it would seem very likely that Hastings and William Royle were wounded during this time, here is an eye witness account from Pte. J.S. Critchley of the 13th Kings and Column 7:

"About three weeks before I was left behind by the column, I saw Capt. David Hastings together with Sgt. W. Royle, both of the 13th Bn. Kings Liverpool Regiment, carried down the Irrawaddy on a dinghy. They were never heard of again. This incident took place during an opposed crossing of the Irrawaddy near Inyawa."

Critchley himself is a very interesting character from 1943. He was left behind in late April that year with another soldier Corporal David Humphrey Jones. These two men managed to survive for nearly a whole year, living as natives in the Burmese village of Lalaw. Considering their physical condition at the time of operation Longcloth and the continual presence of Japanese patrols in the area, this was quite an incredible achievement. Sadly, Jones died from the disease scrub typhus shortly after the pair had been discovered living in the village by the following year's Chindit expedition.

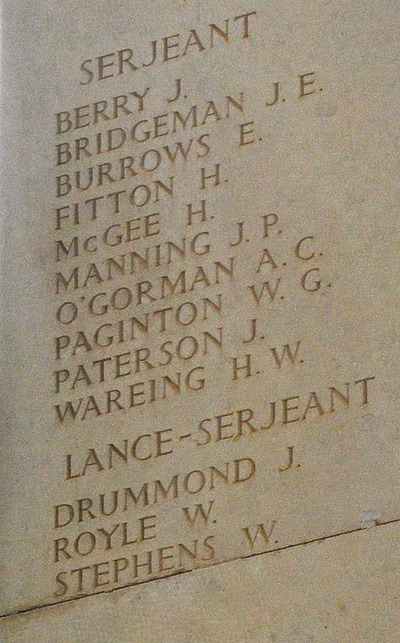

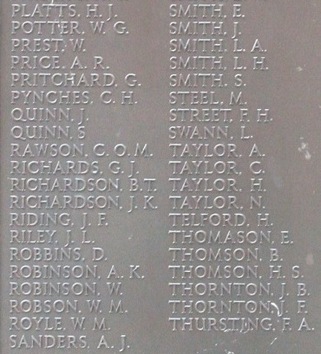

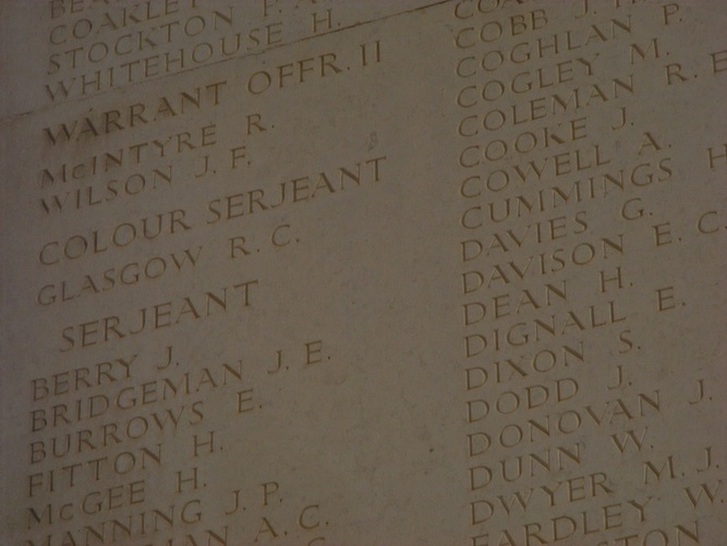

Seen below are the inscription panels from the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery, showing the names of William Royle (image courtesy of Tony B) and James Baker (image courtesy of Marc Fogden). Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

From the pages of the Manchester Evening News dated Tuesday 18th December 1945 and under the headline, Roll of Honour:

Official news has just been received that Cpl. 3781521 Harold Hodgkinson (13th King's Regiment) was killed on the Irrawaddy, March 29th 1943. His life for his country he nobly gave. Memories are mine dear husband. From your wife, May. Followed by: Happy memories always pal. From brother-in-law, John. And finally: We will always remember you smiling son. From Mam and Pop Hewitt.

In late March 1943, Wingate called a halt to the operation in Burma, after being instructed by the Army HQ in India to get as many of his now knowledgeable and experienced Chindit Brigade back safely to Allied territory. Wingate's HQ Brigade had been shielded by columns 7 and 8 for most of the operation in 1943 and it was these three groups that found themselves on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March that year.

Close to the Burmese town of Inywa was chosen as the river crossing point by the column commanders, Ken Gilkes and Water Purcell Scott. As the men prepared to cross some enemy activity was seen on the far bank. Wingate and his commanders felt that the Japanese posed little threat in their present numbers, and so pressed on with the crossing. Some lead boats did manage to get over, but others came under heavy mortar and machine gun fire and began to get into difficulties. One such boat contained William Royle, alongside William was Northern Section Adjutant, Captain David Hastings, Corporal Harold Hodkinson and Ptes. James Baker and Edward Kitchen. This boat was struggling to make the western bank and was continuously under heavy fire from the Japanese positions. From some eye witness accounts it would seem very likely that Hastings and William Royle were wounded during this time, here is an eye witness account from Pte. J.S. Critchley of the 13th Kings and Column 7:

"About three weeks before I was left behind by the column, I saw Capt. David Hastings together with Sgt. W. Royle, both of the 13th Bn. Kings Liverpool Regiment, carried down the Irrawaddy on a dinghy. They were never heard of again. This incident took place during an opposed crossing of the Irrawaddy near Inyawa."

Critchley himself is a very interesting character from 1943. He was left behind in late April that year with another soldier Corporal David Humphrey Jones. These two men managed to survive for nearly a whole year, living as natives in the Burmese village of Lalaw. Considering their physical condition at the time of operation Longcloth and the continual presence of Japanese patrols in the area, this was quite an incredible achievement. Sadly, Jones died from the disease scrub typhus shortly after the pair had been discovered living in the village by the following year's Chindit expedition.

Seen below are the inscription panels from the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery, showing the names of William Royle (image courtesy of Tony B) and James Baker (image courtesy of Marc Fogden). Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

From the pages of the Manchester Evening News dated Tuesday 18th December 1945 and under the headline, Roll of Honour:

Official news has just been received that Cpl. 3781521 Harold Hodgkinson (13th King's Regiment) was killed on the Irrawaddy, March 29th 1943. His life for his country he nobly gave. Memories are mine dear husband. From your wife, May. Followed by: Happy memories always pal. From brother-in-law, John. And finally: We will always remember you smiling son. From Mam and Pop Hewitt.

After the disaster of this attempted crossing, the remaining columns and Wingate's HQ melted back into the jungle on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy. The three units agreed there and then to split up and make their own way back to safety individually. Column 7 retraced their steps and set off toward the Chinese Yunnan borders. Column 8 under Major Scott eventually crossed the Irrawaddy with the help of some native boats, while Wingate held back for over a week, hoping that the Japanese activity in the area would die down and their progress to India could resume unmolested.

Here are William Royle's CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2523816/ROYLE,%20WILLIAM

My thanks must go to Steve Hall, the grandson of William Royle for some of the information used here and especially for the image of William from 1942.

Update 29/06/2013.

William Malloy Royle was born in the first quarter of 1911 in what was known back then as Bucklow RD of Rural District. He attended St. Joseph's School before becoming a plasterer with the firm H. Matthews & Son. His brother, Norman, also served in WW2 and worked with William for the same firm of plasterers.

William married Esther A. Cummins in Bucklow during the summer of 1936. He joined the Army in 1939 and was one of the more fortunate men to be rescued at Dunkirk in May 1940. He was then sent to India in late 1941 with the King's Regiment, serving eventually as one of Wingate's Chindits in the first operation in 1943.

From the local newspaper at the time (13/08/1943): "William Royle and others were crossing the Irrawaddy River in a boat, when it was hit by enemy shell fire and lost." He was reported as missing in the Indian theatre of war, with Elizabeth's address stated as 13 Russell Street, Salford, then later as, 48 Poplar Grove, Sale. (Some of these details were also reported in the 21st December 1945 edition of the Sale & Stretford Guardian).

For more information on the Bucklow Rural district, please click on the link below: http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit/10027494

Seen below are photographs of William Royle's Burma Star medal, sent to me by his grandson Steve and his memorial inscription upon the Sale & Ashton War Memorial, School Road, Sale.

Here are William Royle's CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2523816/ROYLE,%20WILLIAM

My thanks must go to Steve Hall, the grandson of William Royle for some of the information used here and especially for the image of William from 1942.

Update 29/06/2013.

William Malloy Royle was born in the first quarter of 1911 in what was known back then as Bucklow RD of Rural District. He attended St. Joseph's School before becoming a plasterer with the firm H. Matthews & Son. His brother, Norman, also served in WW2 and worked with William for the same firm of plasterers.

William married Esther A. Cummins in Bucklow during the summer of 1936. He joined the Army in 1939 and was one of the more fortunate men to be rescued at Dunkirk in May 1940. He was then sent to India in late 1941 with the King's Regiment, serving eventually as one of Wingate's Chindits in the first operation in 1943.

From the local newspaper at the time (13/08/1943): "William Royle and others were crossing the Irrawaddy River in a boat, when it was hit by enemy shell fire and lost." He was reported as missing in the Indian theatre of war, with Elizabeth's address stated as 13 Russell Street, Salford, then later as, 48 Poplar Grove, Sale. (Some of these details were also reported in the 21st December 1945 edition of the Sale & Stretford Guardian).

For more information on the Bucklow Rural district, please click on the link below: http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit/10027494

Seen below are photographs of William Royle's Burma Star medal, sent to me by his grandson Steve and his memorial inscription upon the Sale & Ashton War Memorial, School Road, Sale.

Update 11/11/2016.

I was pleased to receive another email contact from Steve Hall recently, informing me that his mother, Helen, who is William Royle's daughter, had identified William from another photograph that features on my website:

Hi Steve, just a quick note to say that my Mum has positively identified William, from a photograph on WW2live website on line. I believe my grandfather is fifth person from the left in the second row from the back. Is there any way you can confirm this from your records? We were totally shocked to see the image, but it is definitely him. Thanks again buddy and great to see all the latest submissions from Chindit relatives.

I replied:

The photograph in question (shown below) was sent to me by the daughter of Captain Tommy Roberts, an officer with the original 13th Battalion of the King's, who was taken prisoner by the Japanese during Operation Longcloth. This is a photograph aboard the troopship Oronsay, the ship that took the 13th King's most of the way to India in late 1941. The image depicts the section of men Roberts was responsible for aboard the Oronsay, but it is highly likely that this group of men, were those from the platoon he commanded dating back to the days of the battalions coastal defence duties in England. I must admit, the man in the second row from the back really does look like William.

Tommy Roberts became a member of 5 Column on Operation Longcloth, which means that William must have transferred from his platoon at some point in mid-1942, switching over to 7 Column. This was very common, especially for NCO's, moving around to wherever they were required. This is all I can really tell you. Please find attached the original image, where I have marked William with a star. Your Mum spotting her father in this way is exactly what I always hope for, as it is difficult for me to view a new photograph and try and cross reference it with all the others I have received over the last five years or more.

Since I last spoke with Steve, I have managed to add the story of Captain David Hastings to these website pages. Captain Hastings was in the same dinghy as William Royle when it was fired upon by the Japanese from the western banks of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March 1943. Seen below are some images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Colour Sergeant-Major John Fraser Wilson

John Fraser Wilson was born in Gateshead in 1913 and like many men from the Northeast he worked in the mining industry for a time during his youth. According to his service records he enlisted into the British Army in November 1931 and was posted into the King’s Own Scottish Borderer’s regiment.

John was a member of the B.E.F. in 1940, but saw no real action in France that year, instead he found himself being transferred into C Company of the 13th battalion King’s Liverpool regiment on the 6th July. This newly formed infantry battalion was desperately short of experienced NCO officers and had recruited such men from many regiments found all over the British Isles.

It is probable that John joined the battalion at their original training camp at Jordan Hill barracks, Glasgow. It is definite that he sailed with the battalion aboard the troopship Oronsay, after their posting came through to India in late 1941.

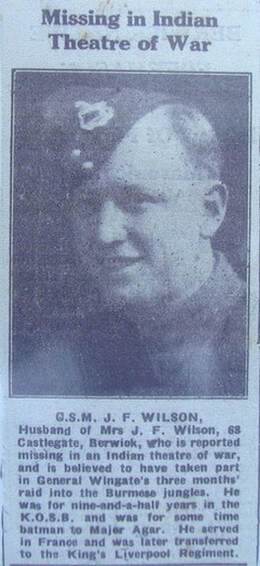

I saw a post from family member Sandra Clemmet on one of the WW2 Forums asking for information about John Fraser Wilson (pictured left) and it was from this contact that I learned of his Army and family background.

After the initial Chindit training had begun in the Central Provinces of India, John found himself a member of Northern Group's Head Quarters. Here he would have led an infantry platoon section in the numerically smaller lead brigade. When Wingate decided to call a halt to the operation in March 1943, the HQ Section were on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River along with columns 7 and 8 and also Wingate's own HQ Brigade. This large unit of soldiers was then broken down into separate dispersal groups.

The first time CSM Wilson’s name appeared on a document was sadly the Missing in Action lists for HQ Section in 1943. He was last seen on 30/04/43 according to these lists, but more information was to appear in the form of a witness statement from the Regimental Sergeant Major of the 13th Kings and column 8, William Livingstone. One way or another his (Wilson's) dispersal group must have joined up with Major Scott’s 8th column on their journey out, toward the safety of the Assam border with Burma.

Here is the full wording from the RSM’s statement:

“The above mentioned Warrant Officer was missing from his column after the engagement on the Kaukkwe Chaung, half a mile east of Okthaik on the 30th April 1943. Number 7011253 RSM Livingstone W. states that he was next to CSM Wilson when firing opened up at 16.15 hours. CSM Wilson lay down with his Tommy gun in a firing position behind a tree. He was not seen after that, although parties remained in the location until evening." (Map reference S.H. 3529).

Signed as a true statement by Lieutenant G.H. Borrow (Kings Reg.)

Below you have photographs of the two men involved in the recording of John Fraser Wilson's missing report. Seen pictured left is William Livingstone, photographed just days before the Kaukkwe Chaung incident. Seen pictured right is George Borrow, probably taken sometime in 1942, as he is still wearing the uniform of the Royal Sussex Regiment, which was his original Army unit.

John was a member of the B.E.F. in 1940, but saw no real action in France that year, instead he found himself being transferred into C Company of the 13th battalion King’s Liverpool regiment on the 6th July. This newly formed infantry battalion was desperately short of experienced NCO officers and had recruited such men from many regiments found all over the British Isles.

It is probable that John joined the battalion at their original training camp at Jordan Hill barracks, Glasgow. It is definite that he sailed with the battalion aboard the troopship Oronsay, after their posting came through to India in late 1941.

I saw a post from family member Sandra Clemmet on one of the WW2 Forums asking for information about John Fraser Wilson (pictured left) and it was from this contact that I learned of his Army and family background.

After the initial Chindit training had begun in the Central Provinces of India, John found himself a member of Northern Group's Head Quarters. Here he would have led an infantry platoon section in the numerically smaller lead brigade. When Wingate decided to call a halt to the operation in March 1943, the HQ Section were on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River along with columns 7 and 8 and also Wingate's own HQ Brigade. This large unit of soldiers was then broken down into separate dispersal groups.

The first time CSM Wilson’s name appeared on a document was sadly the Missing in Action lists for HQ Section in 1943. He was last seen on 30/04/43 according to these lists, but more information was to appear in the form of a witness statement from the Regimental Sergeant Major of the 13th Kings and column 8, William Livingstone. One way or another his (Wilson's) dispersal group must have joined up with Major Scott’s 8th column on their journey out, toward the safety of the Assam border with Burma.

Here is the full wording from the RSM’s statement:

“The above mentioned Warrant Officer was missing from his column after the engagement on the Kaukkwe Chaung, half a mile east of Okthaik on the 30th April 1943. Number 7011253 RSM Livingstone W. states that he was next to CSM Wilson when firing opened up at 16.15 hours. CSM Wilson lay down with his Tommy gun in a firing position behind a tree. He was not seen after that, although parties remained in the location until evening." (Map reference S.H. 3529).

Signed as a true statement by Lieutenant G.H. Borrow (Kings Reg.)

Below you have photographs of the two men involved in the recording of John Fraser Wilson's missing report. Seen pictured left is William Livingstone, photographed just days before the Kaukkwe Chaung incident. Seen pictured right is George Borrow, probably taken sometime in 1942, as he is still wearing the uniform of the Royal Sussex Regiment, which was his original Army unit.

Whether CSM Wilson was killed outright at Kaukkwe or taken prisoner by the Japanese it is impossible to say. What is true to say however is that very few men from column 8 or from this geographical position in Burma ever ended up in any the POW camps.

It may be useful here to explain the lead up and the action at Kaukkwe Chaung (also known in some books and diaries as Kawkeraik), especially as it accounted for so many men of column 8.

On about the 25th April column 8 came across a large open clearing in the Burmese jungle, it was here that the famous ‘Piccadilly Dakota’ landing took place and 17 sick and wounded men were flown back to India. John would have been one of the men who waved good-bye to that plane as it took off for Assam. The column had taken a full supply drop during that period and all the men had enjoyed a few days rest whilst the decision was made as to whether all of them might be air lifted back to india in the same manner. This was not to be.

Accepting their fate of having to walk the last remaining miles back to India, the column headed off once more. All the men had a full ration supply (14 days) and sported new boots and kit. As they skirted the nearby village of Okthaik the unit found itself up against an unexpected obstacle in the form of the 80 yard wide Kaukkwe Chaung. The river was in full spate and crossing it proved very difficult indeed. The men cobbled together makeshift rafts using their life belts and bamboo struts cut from the local area.

Thunderstorms had been raging all day, which had made conditions still worse, when suddenly from out of the southwest corner a Japanese patrol opened fire on the struggling column as it pressed hard to cross the water. Some of the column had reached the other bank, whilst others found themselves with their backs to the water and engaged the enemy in a ferocious firefight.

Several NCO officers found themselves in this group, presumably having waited as rearguard until their platoons had made the difficult river crossing. Sergeants Cheevers and Delaney fired heavily into the Japanese with Tommy and Bren gun giving the other men valuable time to get clear. As reported earlier Wilson and Livingstone were providing similar covering fire.

In all around 10-12 men were killed or lost during this action on the 30th April 1943. Included amongst them were Lieutenant David Rowland, who was shot in the chest and CSM Robert Glasgow who, though only wounded in the leg, refused to be helped away to safety by his comrades and remained to cover their withdrawal, resulting sadly in his eventual death. Also lost in the engagement were Lance Corporal Curry, Corporal James and of course CSM Wilson.

The remaining men from this group eventually disengaged with the enemy and made off double quick into the nearby hills. The cost to the unit was not just the casualties they had incurred, as this quote from the column War Diary shows:

“After the action at Kaukkwe, the group bivouacked for the night 5 miles north west of Okthaik, of the 57 remaining men, only 7 had their packs in tact. Excellent work from RSM Livingstone, CSM Cheevers and Sergeants Glasgow and Delaney."

Here are the CWGC details for John Fraser Wilson and Robert Glasgow:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2528552/WILSON,%20JOHN%20FRASER

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/3069841/GLASGOW,%20ROBERT%20CLARK

Below is part of Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, showing the inscriptions for John Fraser Wilson and Robert Glasgow. Image courtesy of asiawargraves.com

Lance-Corporal Dennis Walmsley

My contact for the personal side of Dennis Walmsley’s story was a man named Brian Seward who now lives in Canada, but who originally came from Ashton-under-Lyne. He emailed me having seen my Chindit 1 interest on the British Medal forum in the autumn of 2008.

His connection to Lance Corporal Walmsley was that his older brother and Dennis were very great friends. Back in those days in Ashton they were inseparable and it was a terrible shock to the Seward family when the news came back from Burma that Dennis had sadly died. Brian also told me that Dennis and a girl called Lily Matthews had become engaged just before he went off to India in 1941.

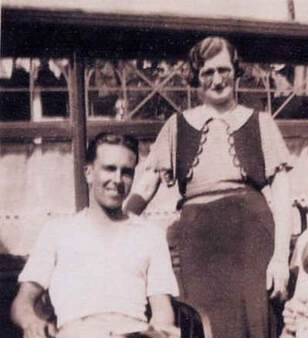

The photo of Dennis Walmsley (pictured left) was taken in 1938 at Lytham St. Ann's. Seen with Dennis is Mrs. Seward, Brian's mother. The photo was taken with an old 'Box Brownie' camera, but still shows up the man's good looks, of which all who knew him seem to comment.

Brian Seward recalls that another man from Ashton had been with Dennis in Burma and on returning to the UK had told the family about his fate in 1943. Here is how Brian related this account to me, in an email in September 2008:

“He actually joined up with another young man from Ashton who had the same Surname beginning with Wa (Forget the rest) so they were together all the time, The other chap survived the war and he told the family that the group were going down a trail when a firefight started and they dove into the underbrush and that’s the last time he saw Dennis!!!! .. That is as much as I know about it."

In 1942 when the King’s battalion found themselves part of Wingate’s fledgling Chindits, Lance Corporal Walmsley was placed into Bernard Fergusson’s column 5. Within this unit he took control of a section of Lieutenant Philip Stibbe’s platoon number 7. In Stibbe’s book ‘Return via Rangoon’, the officer tells a story of how he was forced to make up a man to Lance Corporal with immediate effect, because one of his NCO’s had been demoted and punished for falling asleep on a night watch.

I have often wondered if this might have been Dennis’s promotion, but then Brian told me that he (Dennis) had been home on leave earlier in the war, sporting a very new and very white stripe on his uniform sleeve, so perhaps not.

Column 5 had been involved in the destruction of the railway tracks and bridge at a place called Bonchaung in early March 1943. Dennis and Stibbe’s platoon had played their part in the operation. As the column marched away from Bonchaung and deeper into northeast Burma, they had to leave behind them their first casualties on the operation.

Dennis Walmsley was still very much part of the unit at this point, but it was not very long (just a matter of a few days) before he too found himself adrift from the main group. From all the reading and research I have done in regard to column 5, Walmsley’s disappearance is described no less than three times, which is unusual for a soldier of his rank.

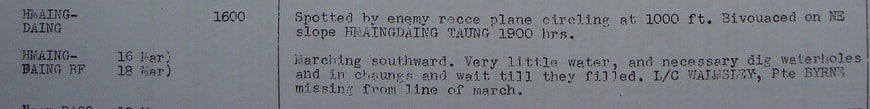

From the column War diary in 1943 comes this small statement:

His connection to Lance Corporal Walmsley was that his older brother and Dennis were very great friends. Back in those days in Ashton they were inseparable and it was a terrible shock to the Seward family when the news came back from Burma that Dennis had sadly died. Brian also told me that Dennis and a girl called Lily Matthews had become engaged just before he went off to India in 1941.

The photo of Dennis Walmsley (pictured left) was taken in 1938 at Lytham St. Ann's. Seen with Dennis is Mrs. Seward, Brian's mother. The photo was taken with an old 'Box Brownie' camera, but still shows up the man's good looks, of which all who knew him seem to comment.

Brian Seward recalls that another man from Ashton had been with Dennis in Burma and on returning to the UK had told the family about his fate in 1943. Here is how Brian related this account to me, in an email in September 2008:

“He actually joined up with another young man from Ashton who had the same Surname beginning with Wa (Forget the rest) so they were together all the time, The other chap survived the war and he told the family that the group were going down a trail when a firefight started and they dove into the underbrush and that’s the last time he saw Dennis!!!! .. That is as much as I know about it."

In 1942 when the King’s battalion found themselves part of Wingate’s fledgling Chindits, Lance Corporal Walmsley was placed into Bernard Fergusson’s column 5. Within this unit he took control of a section of Lieutenant Philip Stibbe’s platoon number 7. In Stibbe’s book ‘Return via Rangoon’, the officer tells a story of how he was forced to make up a man to Lance Corporal with immediate effect, because one of his NCO’s had been demoted and punished for falling asleep on a night watch.

I have often wondered if this might have been Dennis’s promotion, but then Brian told me that he (Dennis) had been home on leave earlier in the war, sporting a very new and very white stripe on his uniform sleeve, so perhaps not.

Column 5 had been involved in the destruction of the railway tracks and bridge at a place called Bonchaung in early March 1943. Dennis and Stibbe’s platoon had played their part in the operation. As the column marched away from Bonchaung and deeper into northeast Burma, they had to leave behind them their first casualties on the operation.

Dennis Walmsley was still very much part of the unit at this point, but it was not very long (just a matter of a few days) before he too found himself adrift from the main group. From all the reading and research I have done in regard to column 5, Walmsley’s disappearance is described no less than three times, which is unusual for a soldier of his rank.

From the column War diary in 1943 comes this small statement:

Then there is this quote from Bernard Fergusson’s book Wild Green Earth:

“I lost three men altogether on the expedition, lost in the literal sense, that is on the line of march. The first was a private soldier (5627646 Pte. George Harry Gray) who was found to be missing after a midday halt: he was never heard of again. The second man (3780147 L.Corporal Dennis Walmsley) was a man who walked out of the perimeter to fetch water from a waterhole a hundred yards away, and failed to return: he was probably lost, it was easy to lose your bearings even so close to the bivouac. The third (3779403 Pte. T.P. Byrne) I lost only one day later: he too nipped out of the column when it had moved only a short distance from the bivouac in search of some lost equipment, he never returned."

The other variation comes from the eyewitness statement mentioned earlier by Walmsley’s pal on his return to Britain after the war. There is some indication that Byrne and Walmsley were together when they went missing, but it is difficult to place too much emphasis on any one account. In Fergusson’s version of the tale, the author does not name the men in question and it is only from my research that I can piece together the events and identify the men involved. Pte. George Gray for instance, I know was sent to liaise with Lieutenant John Kerr at the village of Taungmaw on the 5th March, his job, to lead Kerr's platoon back to the main column unit. He never made that rendezvous.

Fergusson continues: “Both the last two were lost in an area remote from villages and I am quite certain miles from any Japanese; yet both fell into enemy hands, the first after wandering for a day, the second after only 5 minutes. The first died in Rangoon Jail, like most of the others; the second (Byrne) survived and it is from him that we know what happened.”

Being captured so early in the operation (March 18th) would mean that Dennis Walmsley was one of the longest held POW Chindits in 1943. He would have been held in one of the pre-Rangoon prison camps, such as Bhamo or Maymyo. He did make it down to Rangoon in late May that year and like all his fellow Chindit comrades been herded into Block 6 of the jail.

In the jail the officer in charge of a section of POW’s would pair off the men into ‘buddies’. The idea was that your mate would keep an eye on you and attempt to keep your spirits up if you began to take a downward turn. As the men from Operation Longcloth began to lose the battle for life, it was not uncommon for the ‘buddy’ to follow his pal and perish quite quickly after the first man had died.

Dennis Walmsley’s ‘buddy’ was Pte. Leon Frank from Column 7. This is how he described his relationship with his comrade and those terrible early months in Rangoon Jail:

"If you had a friend in there (Rangoon Jail) it was not like a friend in normal times, he was your life. Although you felt mostly on your own in prison and felt so very lonely all the time, your friend was a lifeline.

And often, as sure as fate, when somebody died, a week or two later his mate would also die, almost of a broken heart. I had a friend, Dennis Walmsley from Lancashire, he was my twin to the day, both of us born on April 21st 1920. He was a handsome young lad, he looked just like the film actor Ray Milland. Dennis was a lovely fellow and we were just like brothers. We both suffered from 'dry' beri beri and after a days work outside the jail, we would each massage the other's feet to ease away the terrible discomfort this disease caused us.

Then he died, Dennis did, probably from the beri beri. We had his funeral and as they were carrying him out, some of the lads, they looked over to me and said 'he'll be next you see!' They expected me to follow the usual pattern you understand, your mate dies, then you are going to follow him. I said to myself, "No your not Leon, you haven't even lived yet."

Leon (seen here, left) did very well to survive Rangoon and it was from his account of the jail life that I learnt of Dennis Walmsley’s death. Leon gave an interview to the Imperial War Museum in the 1990’s and he was devastated in January 1944 when his best friend and ‘buddy’ finally gave up his fight against malnutrition and disease and passed away. Lance Corporal Walmsley, POW number 412, was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery near the Royal Lakes in Rangoon and for identification purposes was recorded buried in grave number 144.

Here are the CWGC details for Dennis Walmsley: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2261373/WALMSLEY,%20DENNIS

Pictured below is a very old image of the English Cantonment Cemetery, Rangoon. This was probably from the period between the two wars, my guess being around 1920. It gives you an idea of the place and was where all British citizens whether military of civilian were buried having died in Rangoon or the near vicinity.

Dennis Walmsley’s ‘buddy’ was Pte. Leon Frank from Column 7. This is how he described his relationship with his comrade and those terrible early months in Rangoon Jail:

"If you had a friend in there (Rangoon Jail) it was not like a friend in normal times, he was your life. Although you felt mostly on your own in prison and felt so very lonely all the time, your friend was a lifeline.

And often, as sure as fate, when somebody died, a week or two later his mate would also die, almost of a broken heart. I had a friend, Dennis Walmsley from Lancashire, he was my twin to the day, both of us born on April 21st 1920. He was a handsome young lad, he looked just like the film actor Ray Milland. Dennis was a lovely fellow and we were just like brothers. We both suffered from 'dry' beri beri and after a days work outside the jail, we would each massage the other's feet to ease away the terrible discomfort this disease caused us.

Then he died, Dennis did, probably from the beri beri. We had his funeral and as they were carrying him out, some of the lads, they looked over to me and said 'he'll be next you see!' They expected me to follow the usual pattern you understand, your mate dies, then you are going to follow him. I said to myself, "No your not Leon, you haven't even lived yet."

Leon (seen here, left) did very well to survive Rangoon and it was from his account of the jail life that I learnt of Dennis Walmsley’s death. Leon gave an interview to the Imperial War Museum in the 1990’s and he was devastated in January 1944 when his best friend and ‘buddy’ finally gave up his fight against malnutrition and disease and passed away. Lance Corporal Walmsley, POW number 412, was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery near the Royal Lakes in Rangoon and for identification purposes was recorded buried in grave number 144.

Here are the CWGC details for Dennis Walmsley: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2261373/WALMSLEY,%20DENNIS

Pictured below is a very old image of the English Cantonment Cemetery, Rangoon. This was probably from the period between the two wars, my guess being around 1920. It gives you an idea of the place and was where all British citizens whether military of civilian were buried having died in Rangoon or the near vicinity.

Update 12/02/2024.

It is with great sadness that I have to report the passing of Brian Seward. As you will have read from the story above, Brian was one of the very first people to contribute to my website back in 2008. Brian served in the military himself, as you can read from the transcription of his obituary below, first published by North Shore News (Vancouver) in September 2023.

SEWARD, Leonard Brian

December 12, 1927 - August 20, 2023

Captain Leonard Brian Seward MMM.CD, passed away peacefully August 20th, 2023. He will be sadly missed by his wife Donna, daughter Sheree Butler (Adrian), son James Seward (Lana), 4 grand- children; Tara, Dianna, Christina, Joel, and 3 great-grandchildren. Brian loved spending time with his family near and far. He loved to cook and there was no one who made the Christmas trifle better than him.

Brian was born in England, immigrating to Canada in 1955. He was a veteran of WWII serving in the Royal Navy, and then in the UN Korean War, later joining the Merchant Navy. After coming to Canada he served 28 years with the 6th Field Engineers Squadron of North Vancouver, moving up the ranks from Sergeant- Major to Captain. He also had a long history of working with the Cadets. Being an avid historian, and thanks to his determination and 50 years of acquiring artifacts, the squadron opened a museum in his name on November 11th, 2006. With his vast knowledge of history and military medals, he was asked to restore medals for war veterans, First Responders, and other dignitaries. He was even consulted by director Steven Spielberg to advise and design medals for three of his movies.

Captain Seward was the recipient of the Military Order of Canada, UN Korean War medals, Naval Service Medal, Minister of Veterans Affairs Commendation Medal (2010), Jubilee Medal, and Canadian Decoration and Two Clasps. His travels took him around the world several times while in the Navy. Many a story was told of his adventures to Sri Lanka, Russia, China, South America. He also enjoyed the arts, starring in a play at the Fringe Festival and singing at many events. After retirement he enjoyed working at the Vancouver Court House and the sheriffs department.

All in all I'm sure he would say, "I've had a great ride".

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2011.