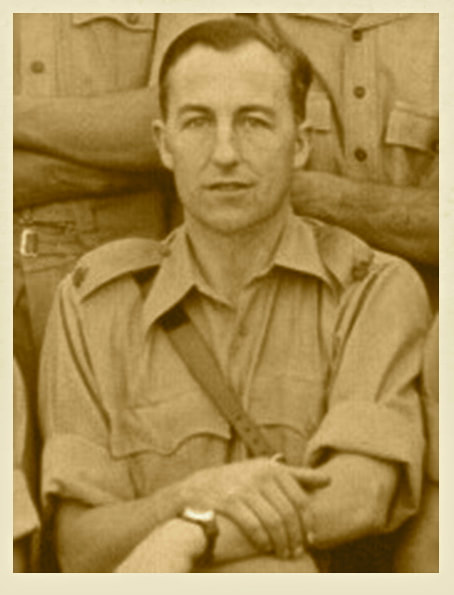

Corporal Fred Morgan

Corporal Frederick William Morgan.

Corporal Frederick William Morgan.

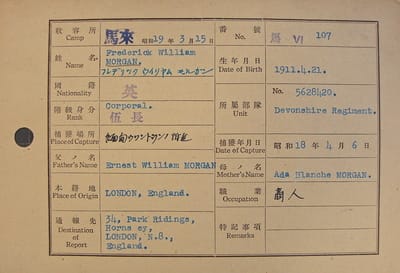

Fred Morgan was born on the 21st April 1914 and was the son of Ernest William and Ada Blanche Morgan from New Malden in Surrey. Fred began his Army service with the Devonshire Regiment and probably voyaged to India on the same troopship as my own grandfather, who was also formerly with the Devon's. Both men were subsequently transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment and arrived at Saugor, the location of the first Chindit training camp on the 26th September 1942.

Corporal 5628420 Frederick William Morgan trained as a Bren gunner and was posted into Chindit Column No. 7 under the overall command of Major Kenneth Gilkes, formerly of the North Staffordshire Regiment. Fred's story first came to my attention from within the pages of the book March or Die. The books author, Phil Chinnery recounted:

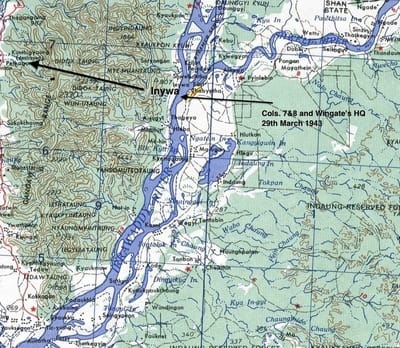

Fred Morgan, another member of 7 Column was among the two platoons of the column that had already crossed the Irrawaddy at Inywa on the 29th March when the Japanese intervened. Apparently he was not with Charles Aves and his group and Fred was soon bagged by the enemy. He told me:

As soon as we landed a decision was made to move off in small groups as quickly as possible, since we did not want to attract too much attention to ourselves. After all, we had no idea as to the strength of the Japanese patrol. The small group I was with was led by Lieutenant Stock. We had paused for a while, resting our heads on our packs, when all of a sudden a number of Japs came tearing up the hillside towards us. Needless to say we beat a hasty retreat up the hill.

Somehow the Bren gun was left behind and I handed my rifle to someone and went back for it. I grabbed it, but found the magazine was empty and therefore useless. On the way back up I started to strip the gun and began throwing the pieces to the four winds. I finally caught up with Lieutenant Stock and found he was in possession of a revolver, but no ammunition. I think we had words with one another over that omission.

We eventually lost contact with each other and I met up with him again in Rangoon Jail. Now I was all by myself. I was alone, tired and frightened. I found myself climbing a very large hill and when I reached the top I started down the other side and began to cross a paddy field. No sooner had I got to the centre of the field when I heard shouting and what appeared to be animal noises. I stopped and turned around to see three Japanese running towards me. One of them had a sword and the other two had fixed bayonets and they started to prod me in the stomach. The Jap with the sword slapped my face and then knocked me to the ground.

My hands were tied behind my back and I was marched back to what must have been an advanced post, complete with a look-out tower, situated just outside Wuntho. I was interrogated by a very tall Japanese officer, who asked me all sorts of military questions about the strengths and whereabouts of the British Army in India. I replied that that sort of information was not available to an ordinary NCO. I was accused of lying and beaten up again.

Along with a number of other Chindits I was taken to Maymyo, where there was a Japanese field prison. Here we were made to learn their language, in particular the various words of command. It behove us all to learn as quickly as possible in order to avoid being beaten up. At the end of the working day, which was spent digging air raid shelters and repairing houses, we had to stand around a flag pole with the Japanese 'Rising Sun' flag fluttering in the breeze. We then had to bow towards the east in honour of their Emperor. After this charade we had to have a sing-song to relieve the tension we felt. Much to the amusement of the guards, a mate of mine, Sergeant Gilbert Josling and myself used to sing Max Miller's song I fell in love with Mary from the Dairy. Sadly, Sergeant Josling did not make it home from Rangoon Jail.

Our compound was surrounded by very heavy iron railings and the Japanese guards used to patrol around this perimeter. Every time the guard passed by, we had to stop what we were doing and bow. At this time I was sitting on the ground with Sergeant Josling's head in my lap, because he was very ill with beri-beri, so I did not get up and bow. The Jap saw me and started shouting obscenities at me, so I laid Gilbert's head down gently and went over to the fence and bowed. The Jap thrust his rifle through the railings butt first and belted me in the stomach and testicles for not bowing to him in the first place. When I returned to Josling he had passed away.

Corporal 5628420 Frederick William Morgan trained as a Bren gunner and was posted into Chindit Column No. 7 under the overall command of Major Kenneth Gilkes, formerly of the North Staffordshire Regiment. Fred's story first came to my attention from within the pages of the book March or Die. The books author, Phil Chinnery recounted:

Fred Morgan, another member of 7 Column was among the two platoons of the column that had already crossed the Irrawaddy at Inywa on the 29th March when the Japanese intervened. Apparently he was not with Charles Aves and his group and Fred was soon bagged by the enemy. He told me:

As soon as we landed a decision was made to move off in small groups as quickly as possible, since we did not want to attract too much attention to ourselves. After all, we had no idea as to the strength of the Japanese patrol. The small group I was with was led by Lieutenant Stock. We had paused for a while, resting our heads on our packs, when all of a sudden a number of Japs came tearing up the hillside towards us. Needless to say we beat a hasty retreat up the hill.

Somehow the Bren gun was left behind and I handed my rifle to someone and went back for it. I grabbed it, but found the magazine was empty and therefore useless. On the way back up I started to strip the gun and began throwing the pieces to the four winds. I finally caught up with Lieutenant Stock and found he was in possession of a revolver, but no ammunition. I think we had words with one another over that omission.

We eventually lost contact with each other and I met up with him again in Rangoon Jail. Now I was all by myself. I was alone, tired and frightened. I found myself climbing a very large hill and when I reached the top I started down the other side and began to cross a paddy field. No sooner had I got to the centre of the field when I heard shouting and what appeared to be animal noises. I stopped and turned around to see three Japanese running towards me. One of them had a sword and the other two had fixed bayonets and they started to prod me in the stomach. The Jap with the sword slapped my face and then knocked me to the ground.

My hands were tied behind my back and I was marched back to what must have been an advanced post, complete with a look-out tower, situated just outside Wuntho. I was interrogated by a very tall Japanese officer, who asked me all sorts of military questions about the strengths and whereabouts of the British Army in India. I replied that that sort of information was not available to an ordinary NCO. I was accused of lying and beaten up again.

Along with a number of other Chindits I was taken to Maymyo, where there was a Japanese field prison. Here we were made to learn their language, in particular the various words of command. It behove us all to learn as quickly as possible in order to avoid being beaten up. At the end of the working day, which was spent digging air raid shelters and repairing houses, we had to stand around a flag pole with the Japanese 'Rising Sun' flag fluttering in the breeze. We then had to bow towards the east in honour of their Emperor. After this charade we had to have a sing-song to relieve the tension we felt. Much to the amusement of the guards, a mate of mine, Sergeant Gilbert Josling and myself used to sing Max Miller's song I fell in love with Mary from the Dairy. Sadly, Sergeant Josling did not make it home from Rangoon Jail.

Our compound was surrounded by very heavy iron railings and the Japanese guards used to patrol around this perimeter. Every time the guard passed by, we had to stop what we were doing and bow. At this time I was sitting on the ground with Sergeant Josling's head in my lap, because he was very ill with beri-beri, so I did not get up and bow. The Jap saw me and started shouting obscenities at me, so I laid Gilbert's head down gently and went over to the fence and bowed. The Jap thrust his rifle through the railings butt first and belted me in the stomach and testicles for not bowing to him in the first place. When I returned to Josling he had passed away.

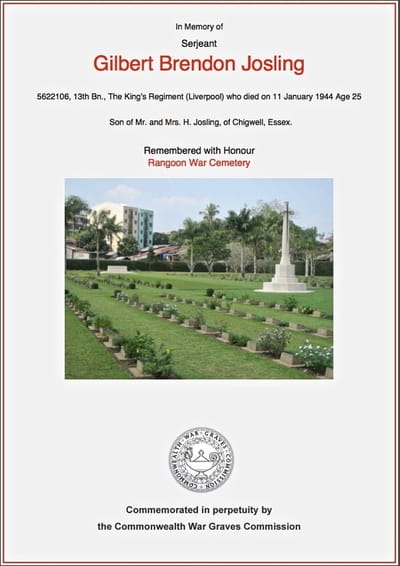

Sgt. Gilbert Brendon Josling was the son of Mr. and Mrs. H. Josling from Chigwell in Essex. Gilbert was another former Devonshire Regiment soldier, of which there were quite a few within the ranks of 7 Column in 1943. He was the senior NCO with No. 14 Rifle Platoon in 7 Column and was also one of the men from the column that had made it over the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March at Inywa. Not much is known about Sgt. Josling's capture by the Japanese, but there is in existence a witness statement by a former comrade from 7 Column, Sgt. A.B. Dickson of the 13th King's:

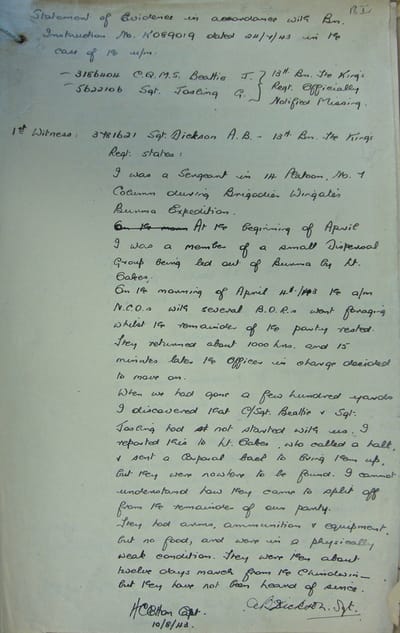

Statement of Evidence dated 24th July 1943, in the case of 3186404 CQMS. J. Beattie and 56222106 Sgt. G. Josling:

3781621 Sgt. A.B. Dickson of the 13th King's states: I was a Sergeant in 14 Platoon, No. 7 Column during Brigadier Wingate's Burma Expedition. At the beginning of April 1943, I was a member of a small dispersal group being led out of Burma by Lt. Oakes. On the morning of April 4th the above mentioned NCO's with several British Other Ranks went foraging (for food) whilst the remainder of the party rested. They returned about 10.00 hours and 15 minutes later the Officer in charge (Oakes) decided to move on.

When we had gone a few hundred yards I discovered that Beattie and Josling had not started with us. I reported this fact to Lt. Oakes who called a halt and sent a Corporal back to bring them up, but they were nowhere to be found. I cannot understand how they came to split off from our party? They had arms, ammunition and equipment, but no food and were in a physically weak condition. They were about 12 days march from the Chindwin River, but they have not been heard of since.

NB. There is a copy of Sgt. Dickson's witness statement in the Gallery of images immediately below this section of the story. To read more about the men from the Devonshire Regiment that became Chindits in 1943, please click on the following link: The Devonshire's Journey

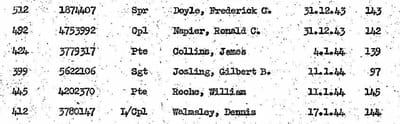

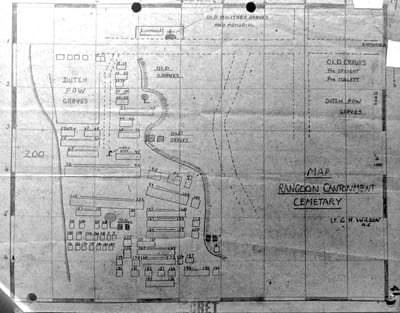

We now know that Gilbert Josling was lost to his unit on the 4th April 1943 along with fellow Chindit James Beattie. Both men had been part of Platoon 14 under the command of Lieutenant Oakes and both became prisoners of war shortly after being reported as missing. Although Sgt. Beattie, from Hawick in Scotland survived his time as a POW, sadly Gilbert Josling died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on 11th January 1944, suffering from the efects of the disease beri beri. His POW number was recorded as being 339 and he was originally buried in grave no. 97 at the English Cantonment Cemetery located near the Royal Lakes in the eastern sector of Rangoon city.

Seen below are some images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Statement of Evidence dated 24th July 1943, in the case of 3186404 CQMS. J. Beattie and 56222106 Sgt. G. Josling:

3781621 Sgt. A.B. Dickson of the 13th King's states: I was a Sergeant in 14 Platoon, No. 7 Column during Brigadier Wingate's Burma Expedition. At the beginning of April 1943, I was a member of a small dispersal group being led out of Burma by Lt. Oakes. On the morning of April 4th the above mentioned NCO's with several British Other Ranks went foraging (for food) whilst the remainder of the party rested. They returned about 10.00 hours and 15 minutes later the Officer in charge (Oakes) decided to move on.

When we had gone a few hundred yards I discovered that Beattie and Josling had not started with us. I reported this fact to Lt. Oakes who called a halt and sent a Corporal back to bring them up, but they were nowhere to be found. I cannot understand how they came to split off from our party? They had arms, ammunition and equipment, but no food and were in a physically weak condition. They were about 12 days march from the Chindwin River, but they have not been heard of since.

NB. There is a copy of Sgt. Dickson's witness statement in the Gallery of images immediately below this section of the story. To read more about the men from the Devonshire Regiment that became Chindits in 1943, please click on the following link: The Devonshire's Journey

We now know that Gilbert Josling was lost to his unit on the 4th April 1943 along with fellow Chindit James Beattie. Both men had been part of Platoon 14 under the command of Lieutenant Oakes and both became prisoners of war shortly after being reported as missing. Although Sgt. Beattie, from Hawick in Scotland survived his time as a POW, sadly Gilbert Josling died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on 11th January 1944, suffering from the efects of the disease beri beri. His POW number was recorded as being 339 and he was originally buried in grave no. 97 at the English Cantonment Cemetery located near the Royal Lakes in the eastern sector of Rangoon city.

Seen below are some images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In August 2012, I was extremely fortunate to be contacted by Corporal Fred Morgan's son, Philip:

Dear Steve

I have been following the various websites in connection with the POWs from Rangoon Jail in WW2. My father, Fred Morgan, was imprisoned there between 1943 and 1945. You have mentioned him in one of your pieces. Fortunately, he was one of the few survivors and returned to the UK to resume his family life. During his time in the jail, my father witnessed the deaths of many of his Army comrades. Although he survived the prison camp and lived to the good age of 90 years, his later years were constantly troubled by memories of the men he had left behind. He had hoped to visit Myanmar a couple of years before he died, but was not deemed fit to travel. Just before he died, he asked me if I ever had the chance to travel to Yangon, that I might visit their graves and pay his respects. I have that chance next month.

After Philip's initial contact we exchanged a few more emails and one or two pieces of information about his father's time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon. In December this year (2016), I received a new and very welcome communication from Philip:

Hello Steve

I have finally returned to the UK after working away in China. I know it seems a long time ago now, but I promised to let you have copies of the photos that I took in Rangoon. I have attached these to three Powerpoint files, together with a brief description of the images. I have also managed to track down a photo of my Dad from his Army days and have also included a copy of his short memoir about those times. I spent about three days in Rangoon, having travelled by a roundabout route from Beijing. This was an interesting journey. I had arranged a local guide to assist me during my time there.

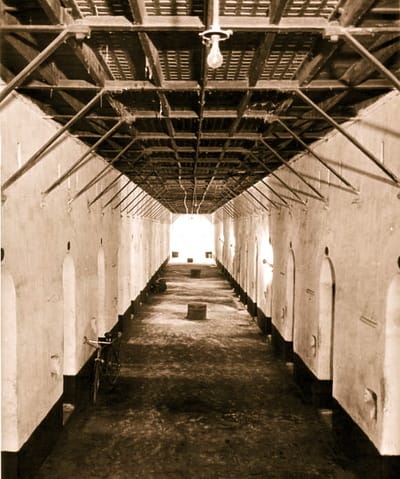

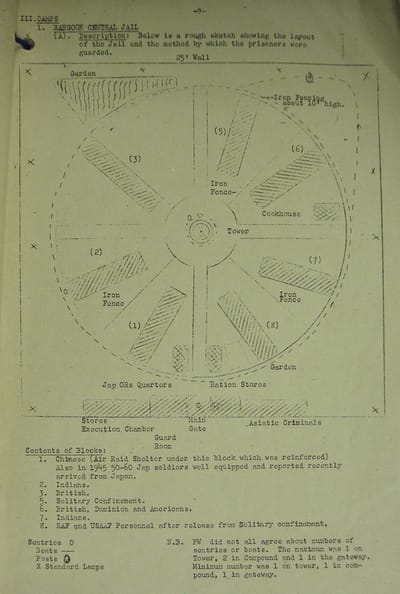

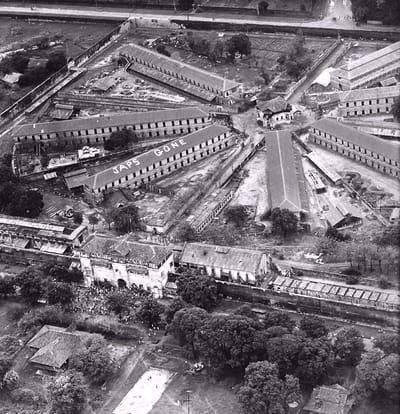

On my first full day, I asked them to take me to the site of Rangoon Central Jail. They seemed a little puzzled by my request and I realized why when we pulled up outside of the new Central Jail! We then proceeded to the site of the old jail. The entire compound covered a large area, but surprisingly was situated within the local community as such. This must have seemed very strange for the POWs, to be part of, yet separate from the Rangoon community. The old jail compound was divided into three parts. At one end was a modern University complex for training nurses. At the other end was a military building, which was heavily guarded. However, the middle part of the compound had reverted to nature and had become overgrown with trees and other vegetation.

You will see from my photographs that it looks so tranquil. My guide became extremely nervous when I asked if I could enter the compound. They offered to to go in on my behalf, as they were worried about a foreigner being seen entering a restricted area. But having come so far, how could I not take this opportunity to go inside. It was very emotional for me as I thought of all the suffering that had taken place there. None of the old jail structure has survived, not that I could see anyway. However, on the northern side of the compound, just outside the railings, was what I was told by a friendly local, the remains of the original hospital buildings. You can see these from the photos. All around the compound was what I took to be the original fencing. After leaving the site of the jail, we then travelled to Rangoon War Cemetery where I was keen to pay my respects to a comrade of my father, Gilbert Josling.

The photographs Philip sent over are quite fascinating, I have seen similar images for the area which was once the English Cantonment Cemetery, which is now a Government sponsored park. This was the cemetery where most of the Chindit casualties from Rangoon Jail were originally buried, including my grandfather and of course Gilbert Josling.

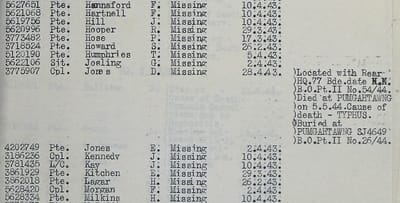

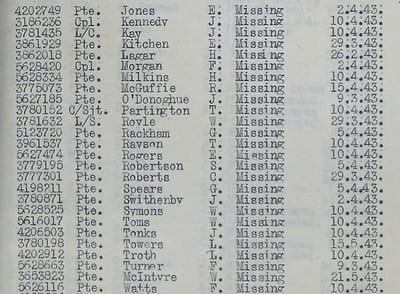

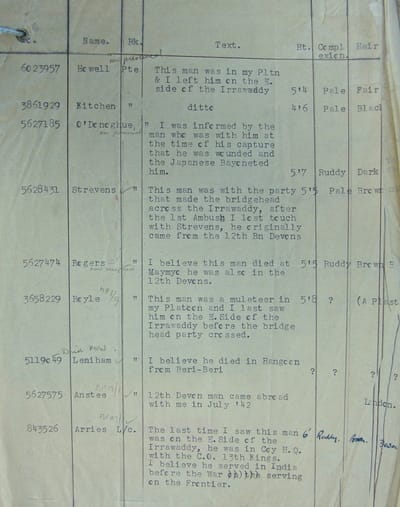

Seen below is a Gallery of images showing some of the photographs sent to me by Philip Morgan, along with some more contemporary images of Rangoon Jail from the WW2 period. Also included in this gallery is the missing in action listing for 7 Column, which includes the entry for Fred Morgan, recording him as missing as of the 2nd April 1943. The other image depicted is his POW index card, these are held at the National Archives in London under the reference WO345. The details shown on the card include his POW number 107, his date of capture, the 6th April 1943 and the place where Fred was captured, directly translated from the Kanji characters as Wantun or Uwantun. I actually believe this refers to the railway town of Wuntho, which matches up with some of the other anecdotal evidence which will become apparant later in this narrative.

Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Dear Steve

I have been following the various websites in connection with the POWs from Rangoon Jail in WW2. My father, Fred Morgan, was imprisoned there between 1943 and 1945. You have mentioned him in one of your pieces. Fortunately, he was one of the few survivors and returned to the UK to resume his family life. During his time in the jail, my father witnessed the deaths of many of his Army comrades. Although he survived the prison camp and lived to the good age of 90 years, his later years were constantly troubled by memories of the men he had left behind. He had hoped to visit Myanmar a couple of years before he died, but was not deemed fit to travel. Just before he died, he asked me if I ever had the chance to travel to Yangon, that I might visit their graves and pay his respects. I have that chance next month.

After Philip's initial contact we exchanged a few more emails and one or two pieces of information about his father's time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon. In December this year (2016), I received a new and very welcome communication from Philip:

Hello Steve

I have finally returned to the UK after working away in China. I know it seems a long time ago now, but I promised to let you have copies of the photos that I took in Rangoon. I have attached these to three Powerpoint files, together with a brief description of the images. I have also managed to track down a photo of my Dad from his Army days and have also included a copy of his short memoir about those times. I spent about three days in Rangoon, having travelled by a roundabout route from Beijing. This was an interesting journey. I had arranged a local guide to assist me during my time there.

On my first full day, I asked them to take me to the site of Rangoon Central Jail. They seemed a little puzzled by my request and I realized why when we pulled up outside of the new Central Jail! We then proceeded to the site of the old jail. The entire compound covered a large area, but surprisingly was situated within the local community as such. This must have seemed very strange for the POWs, to be part of, yet separate from the Rangoon community. The old jail compound was divided into three parts. At one end was a modern University complex for training nurses. At the other end was a military building, which was heavily guarded. However, the middle part of the compound had reverted to nature and had become overgrown with trees and other vegetation.

You will see from my photographs that it looks so tranquil. My guide became extremely nervous when I asked if I could enter the compound. They offered to to go in on my behalf, as they were worried about a foreigner being seen entering a restricted area. But having come so far, how could I not take this opportunity to go inside. It was very emotional for me as I thought of all the suffering that had taken place there. None of the old jail structure has survived, not that I could see anyway. However, on the northern side of the compound, just outside the railings, was what I was told by a friendly local, the remains of the original hospital buildings. You can see these from the photos. All around the compound was what I took to be the original fencing. After leaving the site of the jail, we then travelled to Rangoon War Cemetery where I was keen to pay my respects to a comrade of my father, Gilbert Josling.

The photographs Philip sent over are quite fascinating, I have seen similar images for the area which was once the English Cantonment Cemetery, which is now a Government sponsored park. This was the cemetery where most of the Chindit casualties from Rangoon Jail were originally buried, including my grandfather and of course Gilbert Josling.

Seen below is a Gallery of images showing some of the photographs sent to me by Philip Morgan, along with some more contemporary images of Rangoon Jail from the WW2 period. Also included in this gallery is the missing in action listing for 7 Column, which includes the entry for Fred Morgan, recording him as missing as of the 2nd April 1943. The other image depicted is his POW index card, these are held at the National Archives in London under the reference WO345. The details shown on the card include his POW number 107, his date of capture, the 6th April 1943 and the place where Fred was captured, directly translated from the Kanji characters as Wantun or Uwantun. I actually believe this refers to the railway town of Wuntho, which matches up with some of the other anecdotal evidence which will become apparant later in this narrative.

Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

There now follows a transcription of Fred Morgan's short memoir in relation to his time as a Chindit and as a prisoner of war. Much of the content is a repeat of what Fred told to author Phil Chinnery in 1996, as part of the research for the book March or Die.

The Memories of Ex-Corporal Fred Morgan, 13th Battalion Kings (Liverpool) Regiment

The 1943 Chindit Expedition

A formation was created known as the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade consisting of the 13th Battalion Kings Liverpool Regiment, 3rd/2nd Gurkhas, 2nd Battalion of the Burma Rifles, and the 142 Commando Company. In the January of 1943, I was asked by my Column Commander, Major Ken Gilkes whether or not I was fit enough to go on this venture into Burma. I had previously been in hospital at Saugor with two fractured ribs, having had a slight accident with a mule. Having replied to Major Gilkes in the affirmative, I found myself on the long march up the Manipur Road. We marched by night, to allow the trucks to move supplies by day.

In due course, we reached Imphal and spent a week there recuperating from the march. The Officers had T.E.W.T's, I believe, and the BOR's spent their time in further training. Early in February, the expedition was assembled and inspected by Lord Wavell, and then marched off to Tamu bound for Burma. The first main obstacle we had to overcome was the River Chindwin. I cannot recall the name of the village (Tonhe) at the crossing point, but I remember the difficulty we had in getting the mules into the water, until some bright individual suggested that the officer's chargers should be sent in, and then hopefully the mules would follow, which of course they did. Being a non-swimmer, I seized the opportunity of putting my kit into a rubber dinghy, then I grabbed the tail of a big black mule, and so crossed the Chindwin, pretty damp but safe.

After completing the various tasks that Wingate had set each Column, the powers that be back in India had decided to recall the entire Brigade.

The whole Brigade was assembled on the East Bank of the Irrawaddy, and two platoons from 7 Column were detailed to cross and form a bridgehead to enable the Brigade as a whole to cross safely. I was in the second boat, when we came under machine gun fire from the Japanese, who were hidden in the undergrowth on the West Bank. Wingate saw what was happening and in his wisdom moved the Brigade away from that crossing point, and we found ourselves completely isolated. We engaged the enemy, and after a while we split up into several groups and endeavoured to make our way out, travelling due west back to India.

The small group I was with was led by Lieutenant Stock. We had paused for a while, resting our heads on our packs, when all of a sudden a number of Japs came tearing up the hillside towards us. Needless to say we beat a hasty retreat up the hill. Somehow the Bren gun was left behind and I handed my rifle to someone and went back for it. I grabbed it, but found the magazine was empty and therefore useless. On the way back up I started to strip the gun and began throwing the pieces to the four winds. Sometime later I lost contact with my party.

Owing to the denseness of the jungle around me, I found that I was alone, tired and rather frightened. However, I battled on and found myself climbing what appeared to be a very large hill, and upon reaching the summit I followed an animal track downwards. When I reached the bottom, I decided to cross the paddy field. No sooner had I got to the centre, I heard shouting, and what appeared to be animal noises.

I stopped and turned around to see three Japanese running towards me, one of them had a sword, and the other two had fixed bayonets and they started to prod me in the stomach. The Jap with the sword, slapped my face and then knocked me to the ground, my hands were tied behind my back and I was marched back to what must have been an advance post, complete with a look-out tower, situated just outside Wuntho.

I was interrogated by a very tall Japanese officer, who asked me all sorts of military questions about the strengths and whereabouts of the British Army in India. I replied, saying that this sort of information was not available to an ordinary NCO. I was accused of lying and was beaten again.

NB. a T.E.W.T. is a Tactical Exercise Without Troops.

Before continuing with Fred Morgan's memoir, I thought I should include at this juncture, a transcription of the only eye witness account that mentions his last known movements as a free man in April 1943.

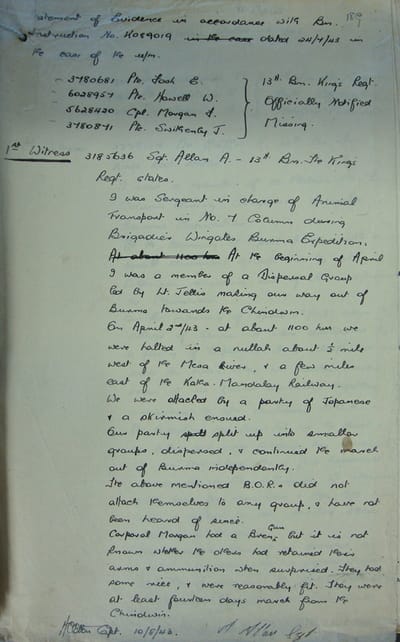

Statement of evidence, dated 24th July 1943, in the case of:

3780681 Pte. E. Fosh

6028957 Pte. W. Howell

5628420 Cpl. F. Morgan

3780871 Pte. J. Swithenby

3185636 Sgt. A. Allan of the 13th King's states: I was the Sergeant in charge of Animal Transport in No. 7 Column during Brigadier Wingate's Burma Expedition. At the beginning of April I was a member of a dispersal group led by Lt. Jelliss, making our way out of Burma towards the Chindwin River. On April 2nd 1943, at about 11.00 hours we were halted in a nullah about half a mile west of the Mesa River and a few miles east of the Katha-Mandalay Railway.

We were attacked by a party of Japanese and a skirmish ensued. Our party split up into smaller groups, then dispersed and continued the march out of Burma independently. The above-mentioned BOR's did not attach themselves to any group and have not been heard of since. Corporal Morgan had a Bren Gun, but it is not known whether the others had retained their arms and ammunition when surprised by the Japanese. They had some rice and were reasonably fit. They were at least 14 days march from the Chindwin.

Here is what I know about the other men listed as missing alongside Fred Morgan; the information is taken from the 13th Battalion's 'Missing in Action' files, held under reference WO361/442 at the National Archives in London:

Pte. 3780681 Edgar John Fosh, was a soldier with 7 Column on Operation Longcloth and was presumed killed on the 2nd April 1943, whilst lost in the Meza Valley, a half-mile from the Meza River and close to the Mandalay-Myitkhina Railway. Edgar has no known grave and so is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, located in the grounds of Taukkyan War Cemetery which is situated in the northern outskirts of the capital city.

Pte. 6023957 William Robert Thomas Howell was the son of Robert and Ethel Howell from Shoreditch in London. William was also a soldier with 7 Column on Operation Longcloth and was also presumed killed on the 2nd April 1943 at the Meza River ambush. He has no known grave and so is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial alongside his comrade Edgar Fosh.

Pte. 37800871 James Swithenby was the son of Nehemiah and Lily Swithenby and the husband of Edith Hannah Swithenby from Leigh in Lancashire. James has exactly the same details recorded to his name as both Edgar Fosh and William Howell, apart from the fact that due to the alphabetical nature of his surname, he is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan.

To read more testimonies about the men from 7 Column who crossed the Irrawaddy in those lead boats on the 29th March 1943, please click on the following links:

Pte. Charles Aves

Robert Valentine Hyner

Captain David Hastings

Seen below is another Gallery of images in relation to this section of the story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The Memories of Ex-Corporal Fred Morgan, 13th Battalion Kings (Liverpool) Regiment

The 1943 Chindit Expedition

A formation was created known as the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade consisting of the 13th Battalion Kings Liverpool Regiment, 3rd/2nd Gurkhas, 2nd Battalion of the Burma Rifles, and the 142 Commando Company. In the January of 1943, I was asked by my Column Commander, Major Ken Gilkes whether or not I was fit enough to go on this venture into Burma. I had previously been in hospital at Saugor with two fractured ribs, having had a slight accident with a mule. Having replied to Major Gilkes in the affirmative, I found myself on the long march up the Manipur Road. We marched by night, to allow the trucks to move supplies by day.

In due course, we reached Imphal and spent a week there recuperating from the march. The Officers had T.E.W.T's, I believe, and the BOR's spent their time in further training. Early in February, the expedition was assembled and inspected by Lord Wavell, and then marched off to Tamu bound for Burma. The first main obstacle we had to overcome was the River Chindwin. I cannot recall the name of the village (Tonhe) at the crossing point, but I remember the difficulty we had in getting the mules into the water, until some bright individual suggested that the officer's chargers should be sent in, and then hopefully the mules would follow, which of course they did. Being a non-swimmer, I seized the opportunity of putting my kit into a rubber dinghy, then I grabbed the tail of a big black mule, and so crossed the Chindwin, pretty damp but safe.

After completing the various tasks that Wingate had set each Column, the powers that be back in India had decided to recall the entire Brigade.

The whole Brigade was assembled on the East Bank of the Irrawaddy, and two platoons from 7 Column were detailed to cross and form a bridgehead to enable the Brigade as a whole to cross safely. I was in the second boat, when we came under machine gun fire from the Japanese, who were hidden in the undergrowth on the West Bank. Wingate saw what was happening and in his wisdom moved the Brigade away from that crossing point, and we found ourselves completely isolated. We engaged the enemy, and after a while we split up into several groups and endeavoured to make our way out, travelling due west back to India.

The small group I was with was led by Lieutenant Stock. We had paused for a while, resting our heads on our packs, when all of a sudden a number of Japs came tearing up the hillside towards us. Needless to say we beat a hasty retreat up the hill. Somehow the Bren gun was left behind and I handed my rifle to someone and went back for it. I grabbed it, but found the magazine was empty and therefore useless. On the way back up I started to strip the gun and began throwing the pieces to the four winds. Sometime later I lost contact with my party.

Owing to the denseness of the jungle around me, I found that I was alone, tired and rather frightened. However, I battled on and found myself climbing what appeared to be a very large hill, and upon reaching the summit I followed an animal track downwards. When I reached the bottom, I decided to cross the paddy field. No sooner had I got to the centre, I heard shouting, and what appeared to be animal noises.

I stopped and turned around to see three Japanese running towards me, one of them had a sword, and the other two had fixed bayonets and they started to prod me in the stomach. The Jap with the sword, slapped my face and then knocked me to the ground, my hands were tied behind my back and I was marched back to what must have been an advance post, complete with a look-out tower, situated just outside Wuntho.

I was interrogated by a very tall Japanese officer, who asked me all sorts of military questions about the strengths and whereabouts of the British Army in India. I replied, saying that this sort of information was not available to an ordinary NCO. I was accused of lying and was beaten again.

NB. a T.E.W.T. is a Tactical Exercise Without Troops.

Before continuing with Fred Morgan's memoir, I thought I should include at this juncture, a transcription of the only eye witness account that mentions his last known movements as a free man in April 1943.

Statement of evidence, dated 24th July 1943, in the case of:

3780681 Pte. E. Fosh

6028957 Pte. W. Howell

5628420 Cpl. F. Morgan

3780871 Pte. J. Swithenby

3185636 Sgt. A. Allan of the 13th King's states: I was the Sergeant in charge of Animal Transport in No. 7 Column during Brigadier Wingate's Burma Expedition. At the beginning of April I was a member of a dispersal group led by Lt. Jelliss, making our way out of Burma towards the Chindwin River. On April 2nd 1943, at about 11.00 hours we were halted in a nullah about half a mile west of the Mesa River and a few miles east of the Katha-Mandalay Railway.

We were attacked by a party of Japanese and a skirmish ensued. Our party split up into smaller groups, then dispersed and continued the march out of Burma independently. The above-mentioned BOR's did not attach themselves to any group and have not been heard of since. Corporal Morgan had a Bren Gun, but it is not known whether the others had retained their arms and ammunition when surprised by the Japanese. They had some rice and were reasonably fit. They were at least 14 days march from the Chindwin.

Here is what I know about the other men listed as missing alongside Fred Morgan; the information is taken from the 13th Battalion's 'Missing in Action' files, held under reference WO361/442 at the National Archives in London:

Pte. 3780681 Edgar John Fosh, was a soldier with 7 Column on Operation Longcloth and was presumed killed on the 2nd April 1943, whilst lost in the Meza Valley, a half-mile from the Meza River and close to the Mandalay-Myitkhina Railway. Edgar has no known grave and so is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, located in the grounds of Taukkyan War Cemetery which is situated in the northern outskirts of the capital city.

Pte. 6023957 William Robert Thomas Howell was the son of Robert and Ethel Howell from Shoreditch in London. William was also a soldier with 7 Column on Operation Longcloth and was also presumed killed on the 2nd April 1943 at the Meza River ambush. He has no known grave and so is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial alongside his comrade Edgar Fosh.

Pte. 37800871 James Swithenby was the son of Nehemiah and Lily Swithenby and the husband of Edith Hannah Swithenby from Leigh in Lancashire. James has exactly the same details recorded to his name as both Edgar Fosh and William Howell, apart from the fact that due to the alphabetical nature of his surname, he is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan.

To read more testimonies about the men from 7 Column who crossed the Irrawaddy in those lead boats on the 29th March 1943, please click on the following links:

Pte. Charles Aves

Robert Valentine Hyner

Captain David Hastings

Seen below is another Gallery of images in relation to this section of the story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Fred Morgan continues his memoir:

After a while quite a number of Chindits had been rounded up and we were then taken up to Maymyo, the hill station of Burma in which there was a Japanese field prison. Here we were made to learn their language in particular the various words of command. It behove us all to learn as quickly as possible in order to avoid being beaten up. An interesting point arose whilst I was there. At the end of the working day which consisted of digging air raid shelters, and repairing houses, we all stood around a flag pole, with the Japanese flag fluttering in the breeze. We then had to bow towards the East in honour of their Emperor.

After this charade, we then had to have a sing-song. Much to the amusement of the guards, a mate of mine Sgt. Gilbert Josling and myself used to sing Max Miller's song "I fell in love with Mary from the Dairy" - this became a daily ritual. When we were locked up for the night in our one room cell, a slice of brown bread and a banana was pushed under our respective doors, this was very much appreciated. The day eventually came when we were all taken by truck to Mandalay via a zig-zag route. Since it was apparently a Burmese water festival celebrating the New Year, at every village we came to, the villagers started to throw water over us, since the days were hot, this gesture was also appreciated. We then went from Mandalay by train to Rangoon in metal trucks.

The journey took us about three days and was very uncomfortable, it was like sitting in an oven. Along the way the train stopped at certain points to allow for a comfort stop and to pick up a number of stragglers from the other Columns that had been captured. Upon reaching Rangoon station we were marched to the Central Gaol which was situated in Commissioner Road. Once inside we entered what became known as No.6 Block. Here we were met by a number of men from the Brigade: Captain Whitehead, Lieutenant's Stibbe, Stock and Spurlock, and numerous other men that I can visualize in my mind's eye, but cannot put names to them. This is not surprising since one's memory fades to a certain extent after fifty-two years.

Our daily routine in Rangoon was monotonous, it began with Tenko or Roll Call, after that we had a so-called breakfast of rice and soup, tea as we knew it was non-existent, just hot water with a few green stalks added, no milk. After this repast we assembled for working parties, men were split up and either sent to the docks to unload rice from the barges, or to dig air raid shelters in and around Rangoon. The treatment shown by the Nips to all POW's was one of humiliation. If we did not understand what was required of us, the guards would either hit you across the face with their clenched fists or kick your shin bones with their iron-toed boots.

During my time in Rangoon, I was detailed, along with fifteen other fellows to go on a working party to a place called Insein, just north of Rangoon. This was a Japanese transport camp, and we were put to work either in the tyre shop (re-treading) or the Blacksmith's and engine shop. The average Nip was not too bad providing you did your job properly. If not, some of them were exceptionally cruel. I was working in the Blacksmith's shop as his ''tapper". Unfortunately, being in a rather weak state, I missed the anvil with the 7lb hammer I was wielding, and it hit the foot of the "smithy" nicknamed "frog face." Needless to say, I was felled to the ground, which I thought was uncalled for.

I well remember when it was the Emperor's birthday, all the Japanese dignitaries and their ladies in their colourful kimonos were coming up from Rangoon to visit this camp for an afternoon's concert. Prior to their arrival we were asked by the senior Jap officer whether any of the POW's could play an instrument, so that they could take part in the festivities. To play it safe, I said that I could play the piano. On the day, it was my turn to clean the rice vat that afternoon, and I noticed an Army truck coming up the track. It stopped opposite the cookhouse and low and behold there was a baby grand on board. Naturally I was scared stiff, but thankfully I was not asked to play and neither were any of the other fellows, much to their relief. We stayed with this transport company for about two months, and then we returned to the gaol for more coolie work.

During my entire sojourn in the gaol, quite a number of men went down with beri-beri and diarrhea. The panacea for these distressing ailments was charcoal and rice water. Needless to say it did not alleviate the suffering. On one particular occasion, several of the men were suffering from abdominal cramps which apparently was the onset of cholera, about a dozen men were lost during this epidemic and their bodies were burnt by the gaol as soon as they had died.

I also recall an incident which happened to me whilst I was in No.6 Compound. On the perimeter of each compound there were very heavy iron railings and the Japanese guards used to patrol around this perimeter, and every time the guard passed by, we had to stop what we were doing and bow. At the time I was sitting on the ground with Sgt Josling's head in my lap because he was very ill with beri-beri. I did not get up and bow to the Nip, who saw me and started shouting obscenities at me, so I laid Josling's head down gently and went over to the Nip and bowed. He thrust his rifle through the railings butt first and belted me in the stomach and testicles for not bowing to him in the first place. When I returned to Josling, he had passed away.

A little later on, as I became more or less fit, I was sent over to No.3 Block, commanded by the Senior British Officer, Brigadier Hobson. He was well over six foot tall and he suffered numerous beatings from the Japanese, who had to stand on a box in order to thump him. The majority of men in this block had been there since 1942. The building itself consisted of two floors, the ground floor was cemented and the upper floor was of wood with barred windows on each side which were open to the elements. As far as possible each room was occupied by about thirty men belonging to a particular Regiment, these included the Cameronians, West Yorkshire's and KOYLI's (King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry).

All the fit men were assigned to daily working parties in all kinds of weather. The monsoon season was the worst since it was difficult to get dry, and invariably we used to go to bed wet and then shivered with the cold. It is a wonder to me, on looking back at these happenings, why more men did not succumb to the harshness of their surroundings and the brutality of the Japanese soldiery.

The following account is of the Japanese attempt to evacuate four hundred POW's from the gaol and march them to Thailand. It took place on the 25th April 1945. My memory of this episode is a little sketchy, but we found ourselves marching along the road to a town called Pegu.

We had several stops along the way, and there were those among us who were all for making an escape, but then decided against making the attempt. I remember walking along a railway line to a wood, and here the Japanese Commandant and his party left us, and Brigadier Hobson informed us that at last we were free men. Nearly all of us wept openly at this news. Now that we were free again, we became extra vigilant, for we knew that our troops could not be very far away.

After a little while, we noticed a number of aircraft machine gunning an area about a mile away and it was decided that a ground panel should be laid on the ground to attract these planes. This we did, using our clothing for the purpose. It so happened that one did fly over us and then went away, but not long after four Hurricanes came over and circled the wood and at the same time began machine gunning us. As soon as I saw my opportunity, I ran towards a temple like building, I have never run so fast in all my life! After the planes had gone, the whole area seemed to come alive with naked men and they could be seen rushing across the paddy fields towards the cover of a village. I stayed the night there in one of the houses, which was raised up on stilts. During the night we could hear the Japanese soldiers crawling beneath us trying to flee the oncoming British troops. Eventually we were rescued by a unit of the West Yorkshire Regiment.

Additional notes:

(1). The reason why some men decided against making an escape, earlier on the march to Pegu, was because they feared that the Japanese guards would exact severe reprisals against those who remained with the main party.

(2). In the friendly fire incident involving the four Hurricanes only one British casualty resulted. Ironically, this was Brigadier Clive Donald Hobson, the senior officer present on the march.

(3). On reflection, how I would have loved to have heard Fred and Gilbert sing Mary From the Dairy, from their time at the Maymyo Camp.

After a while quite a number of Chindits had been rounded up and we were then taken up to Maymyo, the hill station of Burma in which there was a Japanese field prison. Here we were made to learn their language in particular the various words of command. It behove us all to learn as quickly as possible in order to avoid being beaten up. An interesting point arose whilst I was there. At the end of the working day which consisted of digging air raid shelters, and repairing houses, we all stood around a flag pole, with the Japanese flag fluttering in the breeze. We then had to bow towards the East in honour of their Emperor.

After this charade, we then had to have a sing-song. Much to the amusement of the guards, a mate of mine Sgt. Gilbert Josling and myself used to sing Max Miller's song "I fell in love with Mary from the Dairy" - this became a daily ritual. When we were locked up for the night in our one room cell, a slice of brown bread and a banana was pushed under our respective doors, this was very much appreciated. The day eventually came when we were all taken by truck to Mandalay via a zig-zag route. Since it was apparently a Burmese water festival celebrating the New Year, at every village we came to, the villagers started to throw water over us, since the days were hot, this gesture was also appreciated. We then went from Mandalay by train to Rangoon in metal trucks.

The journey took us about three days and was very uncomfortable, it was like sitting in an oven. Along the way the train stopped at certain points to allow for a comfort stop and to pick up a number of stragglers from the other Columns that had been captured. Upon reaching Rangoon station we were marched to the Central Gaol which was situated in Commissioner Road. Once inside we entered what became known as No.6 Block. Here we were met by a number of men from the Brigade: Captain Whitehead, Lieutenant's Stibbe, Stock and Spurlock, and numerous other men that I can visualize in my mind's eye, but cannot put names to them. This is not surprising since one's memory fades to a certain extent after fifty-two years.

Our daily routine in Rangoon was monotonous, it began with Tenko or Roll Call, after that we had a so-called breakfast of rice and soup, tea as we knew it was non-existent, just hot water with a few green stalks added, no milk. After this repast we assembled for working parties, men were split up and either sent to the docks to unload rice from the barges, or to dig air raid shelters in and around Rangoon. The treatment shown by the Nips to all POW's was one of humiliation. If we did not understand what was required of us, the guards would either hit you across the face with their clenched fists or kick your shin bones with their iron-toed boots.

During my time in Rangoon, I was detailed, along with fifteen other fellows to go on a working party to a place called Insein, just north of Rangoon. This was a Japanese transport camp, and we were put to work either in the tyre shop (re-treading) or the Blacksmith's and engine shop. The average Nip was not too bad providing you did your job properly. If not, some of them were exceptionally cruel. I was working in the Blacksmith's shop as his ''tapper". Unfortunately, being in a rather weak state, I missed the anvil with the 7lb hammer I was wielding, and it hit the foot of the "smithy" nicknamed "frog face." Needless to say, I was felled to the ground, which I thought was uncalled for.

I well remember when it was the Emperor's birthday, all the Japanese dignitaries and their ladies in their colourful kimonos were coming up from Rangoon to visit this camp for an afternoon's concert. Prior to their arrival we were asked by the senior Jap officer whether any of the POW's could play an instrument, so that they could take part in the festivities. To play it safe, I said that I could play the piano. On the day, it was my turn to clean the rice vat that afternoon, and I noticed an Army truck coming up the track. It stopped opposite the cookhouse and low and behold there was a baby grand on board. Naturally I was scared stiff, but thankfully I was not asked to play and neither were any of the other fellows, much to their relief. We stayed with this transport company for about two months, and then we returned to the gaol for more coolie work.

During my entire sojourn in the gaol, quite a number of men went down with beri-beri and diarrhea. The panacea for these distressing ailments was charcoal and rice water. Needless to say it did not alleviate the suffering. On one particular occasion, several of the men were suffering from abdominal cramps which apparently was the onset of cholera, about a dozen men were lost during this epidemic and their bodies were burnt by the gaol as soon as they had died.

I also recall an incident which happened to me whilst I was in No.6 Compound. On the perimeter of each compound there were very heavy iron railings and the Japanese guards used to patrol around this perimeter, and every time the guard passed by, we had to stop what we were doing and bow. At the time I was sitting on the ground with Sgt Josling's head in my lap because he was very ill with beri-beri. I did not get up and bow to the Nip, who saw me and started shouting obscenities at me, so I laid Josling's head down gently and went over to the Nip and bowed. He thrust his rifle through the railings butt first and belted me in the stomach and testicles for not bowing to him in the first place. When I returned to Josling, he had passed away.

A little later on, as I became more or less fit, I was sent over to No.3 Block, commanded by the Senior British Officer, Brigadier Hobson. He was well over six foot tall and he suffered numerous beatings from the Japanese, who had to stand on a box in order to thump him. The majority of men in this block had been there since 1942. The building itself consisted of two floors, the ground floor was cemented and the upper floor was of wood with barred windows on each side which were open to the elements. As far as possible each room was occupied by about thirty men belonging to a particular Regiment, these included the Cameronians, West Yorkshire's and KOYLI's (King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry).

All the fit men were assigned to daily working parties in all kinds of weather. The monsoon season was the worst since it was difficult to get dry, and invariably we used to go to bed wet and then shivered with the cold. It is a wonder to me, on looking back at these happenings, why more men did not succumb to the harshness of their surroundings and the brutality of the Japanese soldiery.

The following account is of the Japanese attempt to evacuate four hundred POW's from the gaol and march them to Thailand. It took place on the 25th April 1945. My memory of this episode is a little sketchy, but we found ourselves marching along the road to a town called Pegu.

We had several stops along the way, and there were those among us who were all for making an escape, but then decided against making the attempt. I remember walking along a railway line to a wood, and here the Japanese Commandant and his party left us, and Brigadier Hobson informed us that at last we were free men. Nearly all of us wept openly at this news. Now that we were free again, we became extra vigilant, for we knew that our troops could not be very far away.

After a little while, we noticed a number of aircraft machine gunning an area about a mile away and it was decided that a ground panel should be laid on the ground to attract these planes. This we did, using our clothing for the purpose. It so happened that one did fly over us and then went away, but not long after four Hurricanes came over and circled the wood and at the same time began machine gunning us. As soon as I saw my opportunity, I ran towards a temple like building, I have never run so fast in all my life! After the planes had gone, the whole area seemed to come alive with naked men and they could be seen rushing across the paddy fields towards the cover of a village. I stayed the night there in one of the houses, which was raised up on stilts. During the night we could hear the Japanese soldiers crawling beneath us trying to flee the oncoming British troops. Eventually we were rescued by a unit of the West Yorkshire Regiment.

Additional notes:

(1). The reason why some men decided against making an escape, earlier on the march to Pegu, was because they feared that the Japanese guards would exact severe reprisals against those who remained with the main party.

(2). In the friendly fire incident involving the four Hurricanes only one British casualty resulted. Ironically, this was Brigadier Clive Donald Hobson, the senior officer present on the march.

(3). On reflection, how I would have loved to have heard Fred and Gilbert sing Mary From the Dairy, from their time at the Maymyo Camp.

Fred Morgan and the other men from Rangoon Jail were flown back to India and hospitalised at Calcutta. After being treated for all the ills from his time as a prisoner of war and then enjoying a long period of recuperation, Fred eventually re-joined the 13th King's who were now based at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. By the end of 1945, most of the POW's from Rangoon Jail, including Fred Morgan had been repatriated back to the United Kingdom.

Seen below is another Gallery of images in relation to Fred's time as a prisoner of war, including a photograph of some of the men after their liberation near the Burmese town of Pegu. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Seen below is another Gallery of images in relation to Fred's time as a prisoner of war, including a photograph of some of the men after their liberation near the Burmese town of Pegu. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Kenneth Gilkes post WW2.

Kenneth Gilkes post WW2.

As a footnote to his Burma memoir, Fred Morgan recalled an incident that occurred in April 1985, whilst he was living in the West Sussex town of Worthing:

One morning I happened to be walking along the promenade, when I noticed a very tall gentleman coming towards me, and funnily enough I recognised the way he walked. It was my Column Commander, Major Ken Gilkes.

I stopped him and asked, Major Gilkes?

"Yes" he replied.

I said the last time I saw you was on the East Bank of the Irrawaddy when you detailed my section to cross the river to form a bridgehead. He was overjoyed at seeing me again and we met on several occasions after that, going over those momentous times in 1943.

Sadly he died in the November of that year. I attended his funeral in West Chiltington and amongst those present were Wingate's son (Orde Jonathan) and Mike Calvert.

One morning I happened to be walking along the promenade, when I noticed a very tall gentleman coming towards me, and funnily enough I recognised the way he walked. It was my Column Commander, Major Ken Gilkes.

I stopped him and asked, Major Gilkes?

"Yes" he replied.

I said the last time I saw you was on the East Bank of the Irrawaddy when you detailed my section to cross the river to form a bridgehead. He was overjoyed at seeing me again and we met on several occasions after that, going over those momentous times in 1943.

Sadly he died in the November of that year. I attended his funeral in West Chiltington and amongst those present were Wingate's son (Orde Jonathan) and Mike Calvert.

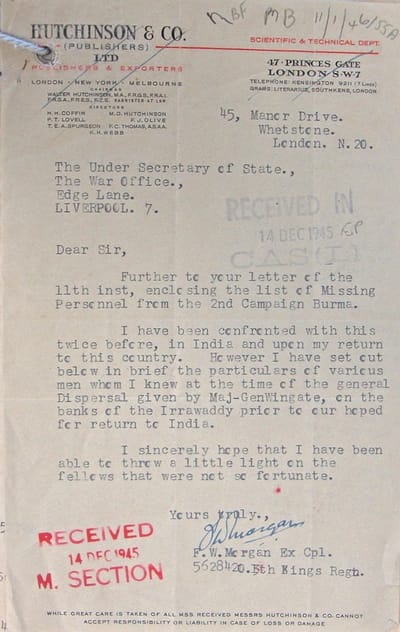

After the war, Fred was asked on numerous occasions to assist the War Office in their quest to ascertain what had happened to the many casualties from the first Wingate expedition. On the 11th December 1945, he received this request for help from the Under Secretary of State to the War Office, sent from the departments temporary offices at the Blue Coat School in Wavertree, Liverpool:

Memorandum for: 5628420 Corporal F.W. Morgan

Missing Personnel, The King's Regiment

The attached list of names are those of men from the The King's Regiment, who are still posted as missing from operations in Burma and it is thought you may be in possession of some useful information concerning them. It will be appreciated if you will forward statements for all those whom you can furnish information showing date, place and circumstances, and if possible, full physical description, civil occupation and home town of the men you have in mind.

Your co-operation in these cases will greatly assist the Department and a prepaid label is enclosed for you reply.

Signed S.C. Bowyer.

Fred replied almost immediately:

Dear Sir,

Further to your letter of the 11th December, enclosing the list of Missing Personnel from the 2nd Burma Campaign. I have been confronted with this list twice before, in India and upon my return to this country. However, I have set out below in brief the particulars of various men whom I knew at the time of the general dispersal, given by Major-General Wingate on the banks of the Irrawaddy prior to our hoped return to India.

I sincerely hope that I have been able to throw a little light on the fellows that were not so fortunate.

Yours truly. F.W. Morgan

Fred then provided a list of some nine casualties from the 13th King's who were lost to the battalion in 1943, four of whom were formerly with the Devonshire Regiment. This list can be viewed in the gallery of images shown immediately below this section of the story.

As an interesting aside, Fred's wife Nora Morgan, also took the time to write down her memories from those difficult days before her husband's safe return from Burma in 1945. She recalled:

VE Day (9 May 1945) was followed by two days public holiday. For me, my war was not over, with my husband having been reported missing in the Far East. The following week I was hoping to be accepted for a one- year teacher-training course; my son was nearly three and his father

had never seen him. On May 13th, however, I received the following telegram: “Alive and well, home soon. Fred Morgan."

I then learned my husband had been one of the Wingate’s Chindits and then a prisoner of war. The survivors from Rangoon were taken to hospital in India, where the nurses were shocked at their condition. Back home, our life together resumed, and before long we were expecting our second child. One night, however, I was awakened by my husband seemingly checking over my face and body. The explanation was simple. In the prison camp many men were dying and the fit men used to watch over each other and should one of them die, the other man would compress the body immediately, as the Japanese only provided half a rice sack for burial. If rigor mortis had set in, they then had to break the limbs of the dead man to get them into the smallest size sack.

In 1999, the Emperor of Japan paid a state visit to Britain. The Far East P.O.W.s and their friends wrote to H.M. the Queen setting out the welcome they would give him as the state coach proceeded up the Mall. They assured the Queen of their loyalty to her, and she understood. As the state coach entered the Mall, the Far East P.O.W.s turned their backs and hooted and jeered. Another occasion I remember, was when my husband was on his way out to Australia and stopped overnight in Rangoon. The following morning, on the plane, he got talking to the Prime Minister of Burma, who assured him that the stories about Japanese atrocities during the war were not true, but politically motivated. “Not so”, said my husband. “I was there.”

My husband and I had a happy and fruitful life together, until the 11th July 2004 when he sadly died, leaving me with our three sons and one daughter, 11 grandchildren and 3 great-grandchildren.

Nora Morgan.

Later in life, Fred Morgan was an enthusiastic member of the Chindit Old Comrades, Burma Star and Far East Prisoners of War Associations. He also regularly attended the reunions held for the ex-POW's from Rangoon Jail, which often included appearances from some of the United States Air Force personnel who had been imprisoned in Rangoon from late 1944. These men had the misfortune to crash-land or be shot down over southern Burma during the last few months of the Japanese occupation. It is true to say that some very strong friendships were formed as a result of these reunions which lasted for many years.

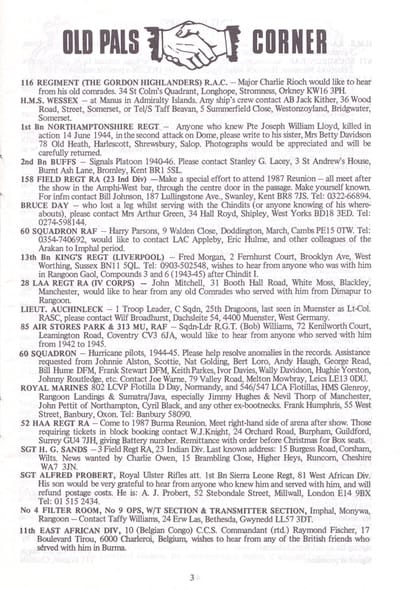

Seen below is another Gallery of images in relation to Fred's Story. These include the casualty listing he sent to the War Office in December 1945 and his search for old comrades from his time in Rangoon Jail, published in the Winter editon of the Burma Star magazine in 1986. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Memorandum for: 5628420 Corporal F.W. Morgan

Missing Personnel, The King's Regiment

The attached list of names are those of men from the The King's Regiment, who are still posted as missing from operations in Burma and it is thought you may be in possession of some useful information concerning them. It will be appreciated if you will forward statements for all those whom you can furnish information showing date, place and circumstances, and if possible, full physical description, civil occupation and home town of the men you have in mind.

Your co-operation in these cases will greatly assist the Department and a prepaid label is enclosed for you reply.

Signed S.C. Bowyer.

Fred replied almost immediately:

Dear Sir,

Further to your letter of the 11th December, enclosing the list of Missing Personnel from the 2nd Burma Campaign. I have been confronted with this list twice before, in India and upon my return to this country. However, I have set out below in brief the particulars of various men whom I knew at the time of the general dispersal, given by Major-General Wingate on the banks of the Irrawaddy prior to our hoped return to India.

I sincerely hope that I have been able to throw a little light on the fellows that were not so fortunate.

Yours truly. F.W. Morgan

Fred then provided a list of some nine casualties from the 13th King's who were lost to the battalion in 1943, four of whom were formerly with the Devonshire Regiment. This list can be viewed in the gallery of images shown immediately below this section of the story.

As an interesting aside, Fred's wife Nora Morgan, also took the time to write down her memories from those difficult days before her husband's safe return from Burma in 1945. She recalled:

VE Day (9 May 1945) was followed by two days public holiday. For me, my war was not over, with my husband having been reported missing in the Far East. The following week I was hoping to be accepted for a one- year teacher-training course; my son was nearly three and his father

had never seen him. On May 13th, however, I received the following telegram: “Alive and well, home soon. Fred Morgan."

I then learned my husband had been one of the Wingate’s Chindits and then a prisoner of war. The survivors from Rangoon were taken to hospital in India, where the nurses were shocked at their condition. Back home, our life together resumed, and before long we were expecting our second child. One night, however, I was awakened by my husband seemingly checking over my face and body. The explanation was simple. In the prison camp many men were dying and the fit men used to watch over each other and should one of them die, the other man would compress the body immediately, as the Japanese only provided half a rice sack for burial. If rigor mortis had set in, they then had to break the limbs of the dead man to get them into the smallest size sack.

In 1999, the Emperor of Japan paid a state visit to Britain. The Far East P.O.W.s and their friends wrote to H.M. the Queen setting out the welcome they would give him as the state coach proceeded up the Mall. They assured the Queen of their loyalty to her, and she understood. As the state coach entered the Mall, the Far East P.O.W.s turned their backs and hooted and jeered. Another occasion I remember, was when my husband was on his way out to Australia and stopped overnight in Rangoon. The following morning, on the plane, he got talking to the Prime Minister of Burma, who assured him that the stories about Japanese atrocities during the war were not true, but politically motivated. “Not so”, said my husband. “I was there.”

My husband and I had a happy and fruitful life together, until the 11th July 2004 when he sadly died, leaving me with our three sons and one daughter, 11 grandchildren and 3 great-grandchildren.

Nora Morgan.

Later in life, Fred Morgan was an enthusiastic member of the Chindit Old Comrades, Burma Star and Far East Prisoners of War Associations. He also regularly attended the reunions held for the ex-POW's from Rangoon Jail, which often included appearances from some of the United States Air Force personnel who had been imprisoned in Rangoon from late 1944. These men had the misfortune to crash-land or be shot down over southern Burma during the last few months of the Japanese occupation. It is true to say that some very strong friendships were formed as a result of these reunions which lasted for many years.

Seen below is another Gallery of images in relation to Fred's Story. These include the casualty listing he sent to the War Office in December 1945 and his search for old comrades from his time in Rangoon Jail, published in the Winter editon of the Burma Star magazine in 1986. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Philip Morgan for all his help in bringing his father's wartime experiences to these website pages and especially in allowing me to include quotes from Fred's memoir. Philip told me:

Steve,

Many many thanks for sending over all the material relating to my Dad. Reading the material you sent through, I just wish I had asked my Dad many more questions. But knowing him, he would probably say, 'why are you doing all of this, it was all in the past!'

Best wishes, Philip.

I would like to dedicate this story to the memory of Sergeant Gilbert Brendon Josling, an Essex man who, like many other soldiers from the Devonshire Regiment, became a Kingsman and a Chindit in 1942. The strong bond of friendship between Fred Morgan and Gilbert Josling is clear to see, revealed not least in the way Fred nursed Gilbert through his final moments of life. At that saddest of moments, I wonder if Fred quietly hummed Mary From the Dairy to help his pal through.

Steve,

Many many thanks for sending over all the material relating to my Dad. Reading the material you sent through, I just wish I had asked my Dad many more questions. But knowing him, he would probably say, 'why are you doing all of this, it was all in the past!'

Best wishes, Philip.

I would like to dedicate this story to the memory of Sergeant Gilbert Brendon Josling, an Essex man who, like many other soldiers from the Devonshire Regiment, became a Kingsman and a Chindit in 1942. The strong bond of friendship between Fred Morgan and Gilbert Josling is clear to see, revealed not least in the way Fred nursed Gilbert through his final moments of life. At that saddest of moments, I wonder if Fred quietly hummed Mary From the Dairy to help his pal through.

I fell in love with Mary from the dairy

But Mary wouldn't fall in love with me.

Down by an old mill stream

We both sat down to dream

Little did she know that I was thinking up a scheme,

She said, 'Let's pick some buttercups and daisies',

But those buttercups were full of margarine

She slipped and we both fell

Down by a wishing well

In the same place where I fell for Nellie Dean.

I fell in love with Mary from the Dairy,

But Mary wouldn't fall in love with me;

Down by an old mill stream

We both sat down to dream:

That was when I offered her my strawberries and cream.

We walked and talked together in the moonlight,

She asked me what I knew of farmery,

I said, 'Mary, I'm no fool,

You can't milk Barney's Bull.'

That's when Mary from the dairy fell for me.

The wife she says that she is going to leave me,

The moment that she does then I am free,

There's a little girl I know

I'll take her and I'll show,

Where Mary from the Dairy fell for me.

'Now on our farm,' said Mary from the dairy,

'We've got the finest cows you've ever seen.

I don't do things by halves -

I'll let you see my calves,

And they're not the same shape calves as Nellie Deans.

But Mary wouldn't fall in love with me.

Down by an old mill stream

We both sat down to dream

Little did she know that I was thinking up a scheme,

She said, 'Let's pick some buttercups and daisies',

But those buttercups were full of margarine

She slipped and we both fell

Down by a wishing well

In the same place where I fell for Nellie Dean.

I fell in love with Mary from the Dairy,

But Mary wouldn't fall in love with me;

Down by an old mill stream

We both sat down to dream:

That was when I offered her my strawberries and cream.

We walked and talked together in the moonlight,

She asked me what I knew of farmery,

I said, 'Mary, I'm no fool,

You can't milk Barney's Bull.'

That's when Mary from the dairy fell for me.

The wife she says that she is going to leave me,

The moment that she does then I am free,

There's a little girl I know

I'll take her and I'll show,

Where Mary from the Dairy fell for me.

'Now on our farm,' said Mary from the dairy,

'We've got the finest cows you've ever seen.

I don't do things by halves -

I'll let you see my calves,

And they're not the same shape calves as Nellie Deans.

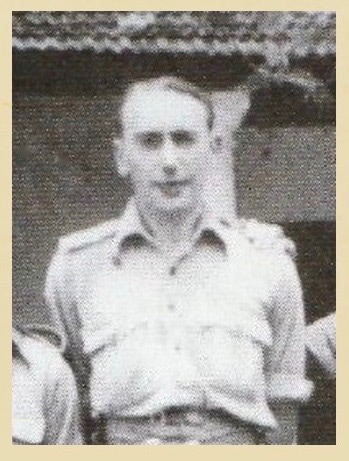

Sgt. Arthur Bernard 'Abe' Dickson.

Sgt. Arthur Bernard 'Abe' Dickson.

Update 08/04/2017.

Back in January 2017, I was immensely pleased to receive an email contact from the grandson of Sgt. A. B. Dickson, the soldier who supplied the witness statement in regards the last known whereabouts of Gilbert Josling, after the contested crossing of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March 1943. Richard Dickson was introduced to me by another Chindit grandson, Daniel Berke, whose grandfather, Frank Berkovitch had also served on Operation Longcloth with Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters.

Sgt. 3781621 Arthur Bernard Dickson (formerly Dikovski), known as Abe to his family and friends was born on the 17th December 1910. We know that Abe was a soldier with the 13th King's C' Company in 1942. It is possible that he was an original member of the 13th Battalion, that sailed to India in December 1941 from Liverpool aboard the troopship Oronsay. Certainly, his Army service number is from the sequence of numbers given to the King's Regiment for the WW2 period.

From his witness statement about Gilbert Josling, we also know that Abe was part of No. 14 Rifle Platoon in 7 Column, which was commanded by Lt. William Alfred Jelliss. The three rifle platoons (13, 14 and 15) from 7 Column were often used as scouting patrols during the early months of the expedition, so it is likely that he saw action against the Japanese on more than one occasion before the ill-fated crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March. Sgt. Dickson was probably a Section Leader within the rifle platoon, which would normally consist of 6-8 men, but on Operation Longcloth the formation of a rifle platoon was slightly different and each Section was comprised of 10-12 Riflemen.

Richard told me that:

As seems to be the case for many Burma veterans, Grandpa did not say too much about his experiences in Burma. My Dad tells me that Abe came home weighing just six and a half stones and that he and his Chindit comrades, ended up eating just about anything they could lay their hands on by the end of their journey back to India. My Dad and his brother Mark, are trying to collect together all the old papers they can find and I still have Grandpa's Burma Star medal. We will send over anything that seems relevant to his story. This has been an incredible and very emotional experience for me as I was only five when Abe passed away. Thank you so much for all your help and I look forward to finding out more.

Back in January 2017, I was immensely pleased to receive an email contact from the grandson of Sgt. A. B. Dickson, the soldier who supplied the witness statement in regards the last known whereabouts of Gilbert Josling, after the contested crossing of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March 1943. Richard Dickson was introduced to me by another Chindit grandson, Daniel Berke, whose grandfather, Frank Berkovitch had also served on Operation Longcloth with Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters.

Sgt. 3781621 Arthur Bernard Dickson (formerly Dikovski), known as Abe to his family and friends was born on the 17th December 1910. We know that Abe was a soldier with the 13th King's C' Company in 1942. It is possible that he was an original member of the 13th Battalion, that sailed to India in December 1941 from Liverpool aboard the troopship Oronsay. Certainly, his Army service number is from the sequence of numbers given to the King's Regiment for the WW2 period.

From his witness statement about Gilbert Josling, we also know that Abe was part of No. 14 Rifle Platoon in 7 Column, which was commanded by Lt. William Alfred Jelliss. The three rifle platoons (13, 14 and 15) from 7 Column were often used as scouting patrols during the early months of the expedition, so it is likely that he saw action against the Japanese on more than one occasion before the ill-fated crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March. Sgt. Dickson was probably a Section Leader within the rifle platoon, which would normally consist of 6-8 men, but on Operation Longcloth the formation of a rifle platoon was slightly different and each Section was comprised of 10-12 Riflemen.

Richard told me that:

As seems to be the case for many Burma veterans, Grandpa did not say too much about his experiences in Burma. My Dad tells me that Abe came home weighing just six and a half stones and that he and his Chindit comrades, ended up eating just about anything they could lay their hands on by the end of their journey back to India. My Dad and his brother Mark, are trying to collect together all the old papers they can find and I still have Grandpa's Burma Star medal. We will send over anything that seems relevant to his story. This has been an incredible and very emotional experience for me as I was only five when Abe passed away. Thank you so much for all your help and I look forward to finding out more.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2016. With special thanks to Liam Brady for the photographs of the Rangoon Jail reunion in 1988.