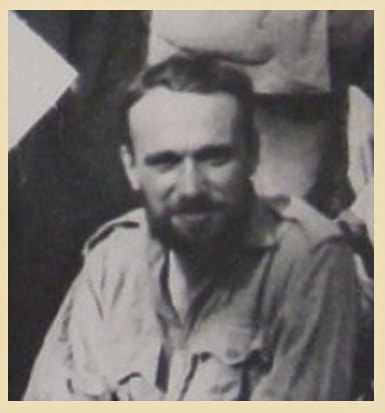

Pte. Sean Dermody

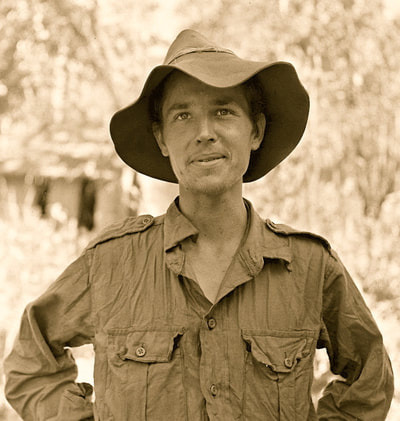

Pte. Sean Dermody in India.

Pte. Sean Dermody in India.

3662755 Pte. Sean Dermody was born in 1921. He was the son of John and Rose Dermody from the shores of Loch Gowna in County Longford, Republic of Ireland. It is rumoured that Sean used to be a jockey back home before he became one of the many men from Ireland to enlist into the British Army during WW2. He enlisted using his older brother’s name of Bernard and possibly served at Dunkirk with, judging by his Army number, the South Lancashire Regiment. After returning to England from the beaches of Dunkirk, he was transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment.

Although I had read about Pte. Dermody in many of the books written about the Chindits, I only really became aware of his full contribution on both Wingate campaigns after receiving an email contact in late December 2010, from his great nephew, Thomas O’Connor:

Dear Steve,

Thank you for your email and the information about my great uncle, Sean Dermody. I'm not sure if he was a jockey in civilian life, but his family did come from rural Ireland and so it is likely that he handled horses. I do know that my mother always said that he had been in charge of mules in Burma, she also tells me my great aunt had a photograph of him that she got from the BBC. This came from a screening of an episode of World at War which was shown in the 1970's. I was surprised to learn from you that he served on both Chindit expeditions. Strange to think he had to be rescued at the Irrawaddy; the family were all good swimmers as they were born and bred on the shores of Loch Gowna in County Longford, the old house is still there today.

I showed my mother and one of her sisters the emails and information you sent over and they were thrilled and a discussion commenced on what they remembered. It was the first time my aunt had seen the photo from the Illustrated magazine cutting though both her and mum recognised it straight away. I know that somewhere there is a portrait of Sean, clean shaven and proudly wearing his slouch hat. From discussions with the family it is now believed that he was at least two years younger than 23 when he died, this is the age given by the CWGC on line. Another discussion centred on how Sean actually died, with mum and my aunt seeming to think it had something to do with a tank causing his injuries. I will however read the books you have told me about and get back in touch.

Please accept our thanks Steve for what you have told us and indeed sent. I am going to print off all the pictures and information and put it all together for my mum and the rest of the family. Also thanks for the picture of his gravestone which touched me greatly. I noticed the inscription at the bottom which may have been instructed by his parents. I had seen a picture of the cemetery from the CWGC website, but it hits harder when you see the actual name.

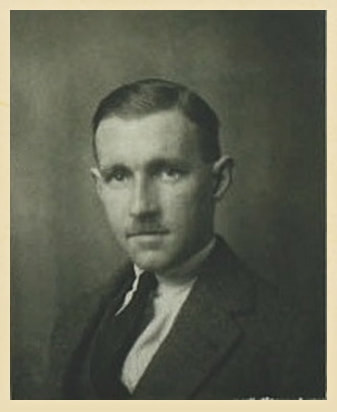

Pte. Dermody, known affectionately as Paddy to his Army comrades served on Operation Longcloth as Brigadier Wingate’s groom, journeying alongside the Chindit Commander in his Brigade Head Quarters. Sean had struck up a good relationship with Brigadier Wingate during training and this continued on through the operation behind enemy lines in 1943. On the 24th March, Wingate was instructed by India Command to return his troops to India and after holding an emergency conference with his column commanders, decided to end the expedition and head for home.

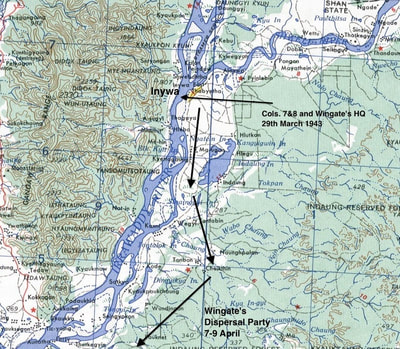

By the 29th March, Brigade HQ were back on the east banks of the Irrawaddy River in the company of Nos. 7 and 8 Columns, and close to the village of Inywa. Unfortunately, the attempted crossing was compromised when a large Japanese patrol attacked the leading Chindit boats with machine gun and mortar fire. The crossing at Inywa was duly abandoned, the remaining columns and Wingate's HQ melted back into the jungle on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy.

The three units agreed there and then to split up and make their own way back to Allied held territory individually. 7 Column retraced their steps and set off northeast towards the Shweli River and ultimately exited Burma via the Chinese Yunnan borders. 8 Column under Major Scott eventually crossed the Irrawaddy two weeks later with the help of some native boats, while Wingate, after breaking his Brigade Head Quarters up into five separate dispersal groups, took his own smaller party back into the jungle close to Inywa, in the hope that the Japanese activity in the area would die down and their progress to India could resume unmolested. Eight days later after a long and tiresome period of recuperation, Wingate led his dispersal party away from Inywa and headed south, but always kept the Irrawaddy close to his right hand side.

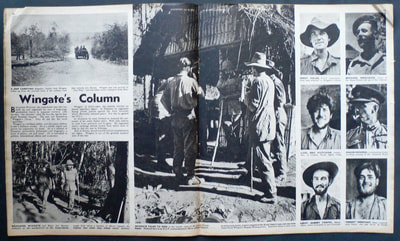

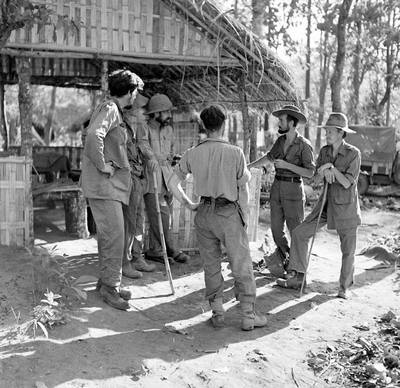

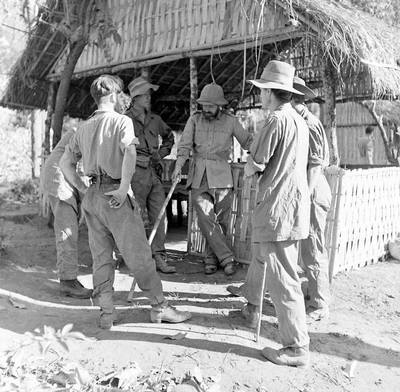

Seen below is a group photograph showing Brigadier Wingate and some of the men from his dispersal group. This image was taken during the period in the jungle between 30th March and 7th April 1943. Sean Dermody I believe, is the man on Wingate's shoulder to the immediate right.

Although I had read about Pte. Dermody in many of the books written about the Chindits, I only really became aware of his full contribution on both Wingate campaigns after receiving an email contact in late December 2010, from his great nephew, Thomas O’Connor:

Dear Steve,

Thank you for your email and the information about my great uncle, Sean Dermody. I'm not sure if he was a jockey in civilian life, but his family did come from rural Ireland and so it is likely that he handled horses. I do know that my mother always said that he had been in charge of mules in Burma, she also tells me my great aunt had a photograph of him that she got from the BBC. This came from a screening of an episode of World at War which was shown in the 1970's. I was surprised to learn from you that he served on both Chindit expeditions. Strange to think he had to be rescued at the Irrawaddy; the family were all good swimmers as they were born and bred on the shores of Loch Gowna in County Longford, the old house is still there today.

I showed my mother and one of her sisters the emails and information you sent over and they were thrilled and a discussion commenced on what they remembered. It was the first time my aunt had seen the photo from the Illustrated magazine cutting though both her and mum recognised it straight away. I know that somewhere there is a portrait of Sean, clean shaven and proudly wearing his slouch hat. From discussions with the family it is now believed that he was at least two years younger than 23 when he died, this is the age given by the CWGC on line. Another discussion centred on how Sean actually died, with mum and my aunt seeming to think it had something to do with a tank causing his injuries. I will however read the books you have told me about and get back in touch.

Please accept our thanks Steve for what you have told us and indeed sent. I am going to print off all the pictures and information and put it all together for my mum and the rest of the family. Also thanks for the picture of his gravestone which touched me greatly. I noticed the inscription at the bottom which may have been instructed by his parents. I had seen a picture of the cemetery from the CWGC website, but it hits harder when you see the actual name.

Pte. Dermody, known affectionately as Paddy to his Army comrades served on Operation Longcloth as Brigadier Wingate’s groom, journeying alongside the Chindit Commander in his Brigade Head Quarters. Sean had struck up a good relationship with Brigadier Wingate during training and this continued on through the operation behind enemy lines in 1943. On the 24th March, Wingate was instructed by India Command to return his troops to India and after holding an emergency conference with his column commanders, decided to end the expedition and head for home.

By the 29th March, Brigade HQ were back on the east banks of the Irrawaddy River in the company of Nos. 7 and 8 Columns, and close to the village of Inywa. Unfortunately, the attempted crossing was compromised when a large Japanese patrol attacked the leading Chindit boats with machine gun and mortar fire. The crossing at Inywa was duly abandoned, the remaining columns and Wingate's HQ melted back into the jungle on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy.

The three units agreed there and then to split up and make their own way back to Allied held territory individually. 7 Column retraced their steps and set off northeast towards the Shweli River and ultimately exited Burma via the Chinese Yunnan borders. 8 Column under Major Scott eventually crossed the Irrawaddy two weeks later with the help of some native boats, while Wingate, after breaking his Brigade Head Quarters up into five separate dispersal groups, took his own smaller party back into the jungle close to Inywa, in the hope that the Japanese activity in the area would die down and their progress to India could resume unmolested. Eight days later after a long and tiresome period of recuperation, Wingate led his dispersal party away from Inywa and headed south, but always kept the Irrawaddy close to his right hand side.

Seen below is a group photograph showing Brigadier Wingate and some of the men from his dispersal group. This image was taken during the period in the jungle between 30th March and 7th April 1943. Sean Dermody I believe, is the man on Wingate's shoulder to the immediate right.

Another soldier with Wingate at this time was Signalman Eric Hutchins. Eric recalled those days in the jungle near Inywa:

I found this time very exacting and boring, we could not talk in more than a whisper and the mules had to be kept quiet. Eventually we killed all the mules and broke up our large equipment and dumped it in the jungle. Although we were concerned about the Japanese still being about, It was a relief to be on the move again.

On 7th April, Wingate made a second attempt at crossing the Irrawaddy, 25 miles south of Inywa. For two days they had searched the bank for boats, but Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles could only find one boat and this could hold only seven people at a time. The group began crossing late in the afternoon, but quite suddenly automatic fire was heard from the north and the native boatman made off taking his boat with him and leaving the final party stranded on the east bank.

Eric Hutchins, now suffering badly with dysentery was with this last party waiting to cross the river, together with him were; Squadron Leader Longmore, Flight Lieutenant Tooth, Flight Sergeant Fidler, Lieutenant Rose of the Gurkhas and Private Dermody and Private Weston of the King's.

Eric remembered:

The first six boat parties made their way safely to the opposite bank. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the opposite bank we could find no trace of the others. Wingate's excuse when we met him later, was he 'thought' we had been captured by the Japanese, whereas he had abandoned us without maps or any means of finding our way back to our own lines. Such is my regard for a commander who later became world famous.

So we set out west only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Our problems now really began, because we could not find a suitable boat. Eventually we found a boat that had seen better days and decided to take a chance crossing at night, using our rifles as oars. Of course the inevitable happened and the boat capsized.

I and others swam to the west shore, where we had to rescue two of our party who were clutching on to a floating plant because they could not swim. At light of day we found that Squadron Leader Longmore was missing. Later at the end of the war I found out that he had remained clutching the boat and floated down river and was eventually captured. We found we were on another island and right opposite a very large village and most of the inhabitants walked across the shallow water to the island, presumably out of curiosity.

We had lost everything when the boat capsized and had no arms to defend ourselves, except that I still had a hand grenade. We went with the villagers and enjoyed a meal of rice and obtained two sacks of rice, cooking pans, a flint stone to make a fire, salt and juggery, the latter unrefined sugar.

Suddenly there was a commotion in the village and the locals started to disperse, which was a signal to us that the Japs had arrived. We made a quick retreat and proceeded to climb the hills behind the village and make our way westwards. Our progress after that was mainly at night, avoiding paths and villages. I remember the beautiful clear moonlit nights with the stars to guide us. I often look for a constellation set at dead 270 degrees which we used as our direction arrow as we kept walking westwards.

Daytime was spent trying to sleep in the intense heat with no water, setting out at dusk to find water and cook a meal. I was suffering severely from dysentery, but somehow raised the strength to carry on. As we neared the Chindwin we found a small chaung in which were some pools of water containing fish. We caught one by swimming under water, but then became greedy and thought if we threw my grenade into the water we could have a real feast. This was not to be because the grenade failed to explode as I had forgotten to prime it.

On seeing the river valley of the Chindwin we now became over-confident and started to abandon our policy of avoiding footpaths. On rounding a bend we ran into a Japanese sentry guarding the path. We immediately plunged into the jungle to our left, but Weston was captured because he was too weak to react quickly. We were forced to stand in a marsh for thirty-six hours while the Japs set fire to it to try to draw us out. Meanwhile we could hear the screams of Weston as they slowly tortured him to death with their bayonets.

On the second night we came out of the marsh only to walk straight through the Jap occupied village. We walked on down the path leading to the Chindwin and then, practising the usual dispersal drill on leaving a path, hid in the jungle nearby. Within fifteen minutes a party of Japs came down the track, following our footprints by torch light. Fortunately for us they hesitated where our footprints finished and then carried on. This was our cue and we retreated deeper into the jungle.

Within half an hour they were back searching the spot we had left. We were now under real pressure and headed for the Chindwin, but could not find a boat to cross. We were walking along the path on the river bank and came to a small clearing with Lieutenant Rose leading. He suddenly turned round and yelled Japs' and in the sudden rush to retreat I fell over. I scrambled to my feet, leaving behind the rice sack I was carrying. The others had a good fifty yards' start on me and machine gun bullets were whizzing all around. I think I broke the world record for 200 yards and reached the jungle on the opposite side of the clearing before the others.

Here we lost Lieutenant Rose and I heard after the war he was later captured and also survived the prison camp. We decided to regain the hills and walk northwards hoping there would be fewer Japs to encounter in that direction. We came upon a hut in the middle of a paddy field and found a native sitting inside. He immediately beckoned us to lie down in the paddy and pointed to a road about fifty yards away where Jap lorries were moving. He indicated to follow him crawling on our bellies to a small copse, it was here that our miracle occurred.

He brought us food twice a day for three days while we got our strength back. He could not get us a boat but when we drew bamboo poles he understood and on each night visit he brought two bamboo poles. Finally we had enough to make a raft and took them down to the river at the dead of night and our saviour tied them together. We had no money and could not reward him, but gave him a note saying how he had helped us and that he should be rewarded by the British if he produced the document.

This man, a complete stranger, possibly a Buddhist, displayed all the ethics of a Good Samaritan and has remained in my deepest thoughts all my life. That day in 1943 on the banks of the Chindwin I learned to believe in miracles. I was the only strong swimmer and pushed the raft from the rear. Some of the other survivors were too weak to swim and had to be hauled back on the raft. Eventually we reached the other side and rested for the night. In the morning we walked into the nearest village which was occupied by Gurkhas.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I found this time very exacting and boring, we could not talk in more than a whisper and the mules had to be kept quiet. Eventually we killed all the mules and broke up our large equipment and dumped it in the jungle. Although we were concerned about the Japanese still being about, It was a relief to be on the move again.

On 7th April, Wingate made a second attempt at crossing the Irrawaddy, 25 miles south of Inywa. For two days they had searched the bank for boats, but Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles could only find one boat and this could hold only seven people at a time. The group began crossing late in the afternoon, but quite suddenly automatic fire was heard from the north and the native boatman made off taking his boat with him and leaving the final party stranded on the east bank.

Eric Hutchins, now suffering badly with dysentery was with this last party waiting to cross the river, together with him were; Squadron Leader Longmore, Flight Lieutenant Tooth, Flight Sergeant Fidler, Lieutenant Rose of the Gurkhas and Private Dermody and Private Weston of the King's.

Eric remembered:

The first six boat parties made their way safely to the opposite bank. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the opposite bank we could find no trace of the others. Wingate's excuse when we met him later, was he 'thought' we had been captured by the Japanese, whereas he had abandoned us without maps or any means of finding our way back to our own lines. Such is my regard for a commander who later became world famous.

So we set out west only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Our problems now really began, because we could not find a suitable boat. Eventually we found a boat that had seen better days and decided to take a chance crossing at night, using our rifles as oars. Of course the inevitable happened and the boat capsized.

I and others swam to the west shore, where we had to rescue two of our party who were clutching on to a floating plant because they could not swim. At light of day we found that Squadron Leader Longmore was missing. Later at the end of the war I found out that he had remained clutching the boat and floated down river and was eventually captured. We found we were on another island and right opposite a very large village and most of the inhabitants walked across the shallow water to the island, presumably out of curiosity.

We had lost everything when the boat capsized and had no arms to defend ourselves, except that I still had a hand grenade. We went with the villagers and enjoyed a meal of rice and obtained two sacks of rice, cooking pans, a flint stone to make a fire, salt and juggery, the latter unrefined sugar.

Suddenly there was a commotion in the village and the locals started to disperse, which was a signal to us that the Japs had arrived. We made a quick retreat and proceeded to climb the hills behind the village and make our way westwards. Our progress after that was mainly at night, avoiding paths and villages. I remember the beautiful clear moonlit nights with the stars to guide us. I often look for a constellation set at dead 270 degrees which we used as our direction arrow as we kept walking westwards.

Daytime was spent trying to sleep in the intense heat with no water, setting out at dusk to find water and cook a meal. I was suffering severely from dysentery, but somehow raised the strength to carry on. As we neared the Chindwin we found a small chaung in which were some pools of water containing fish. We caught one by swimming under water, but then became greedy and thought if we threw my grenade into the water we could have a real feast. This was not to be because the grenade failed to explode as I had forgotten to prime it.

On seeing the river valley of the Chindwin we now became over-confident and started to abandon our policy of avoiding footpaths. On rounding a bend we ran into a Japanese sentry guarding the path. We immediately plunged into the jungle to our left, but Weston was captured because he was too weak to react quickly. We were forced to stand in a marsh for thirty-six hours while the Japs set fire to it to try to draw us out. Meanwhile we could hear the screams of Weston as they slowly tortured him to death with their bayonets.

On the second night we came out of the marsh only to walk straight through the Jap occupied village. We walked on down the path leading to the Chindwin and then, practising the usual dispersal drill on leaving a path, hid in the jungle nearby. Within fifteen minutes a party of Japs came down the track, following our footprints by torch light. Fortunately for us they hesitated where our footprints finished and then carried on. This was our cue and we retreated deeper into the jungle.

Within half an hour they were back searching the spot we had left. We were now under real pressure and headed for the Chindwin, but could not find a boat to cross. We were walking along the path on the river bank and came to a small clearing with Lieutenant Rose leading. He suddenly turned round and yelled Japs' and in the sudden rush to retreat I fell over. I scrambled to my feet, leaving behind the rice sack I was carrying. The others had a good fifty yards' start on me and machine gun bullets were whizzing all around. I think I broke the world record for 200 yards and reached the jungle on the opposite side of the clearing before the others.

Here we lost Lieutenant Rose and I heard after the war he was later captured and also survived the prison camp. We decided to regain the hills and walk northwards hoping there would be fewer Japs to encounter in that direction. We came upon a hut in the middle of a paddy field and found a native sitting inside. He immediately beckoned us to lie down in the paddy and pointed to a road about fifty yards away where Jap lorries were moving. He indicated to follow him crawling on our bellies to a small copse, it was here that our miracle occurred.

He brought us food twice a day for three days while we got our strength back. He could not get us a boat but when we drew bamboo poles he understood and on each night visit he brought two bamboo poles. Finally we had enough to make a raft and took them down to the river at the dead of night and our saviour tied them together. We had no money and could not reward him, but gave him a note saying how he had helped us and that he should be rewarded by the British if he produced the document.

This man, a complete stranger, possibly a Buddhist, displayed all the ethics of a Good Samaritan and has remained in my deepest thoughts all my life. That day in 1943 on the banks of the Chindwin I learned to believe in miracles. I was the only strong swimmer and pushed the raft from the rear. Some of the other survivors were too weak to swim and had to be hauled back on the raft. Eventually we reached the other side and rested for the night. In the morning we walked into the nearest village which was occupied by Gurkhas.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Pte. Dermody was one of the very few Other Ranked soldiers to take part in both Chindit expeditions. In 1944, he became groom to newly promoted, Brigadier Mike Calvert, tasked with looking after his pony named Jean. Sean was all set to enter Burma for a second time on the 5th March 1944. This time he was scheduled to fly in aboard Glider 15P, which was going to be towed by a Dakota transport plane in the first instance, before being released when the glider was over the chosen landing area, codenamed Broadway. As it turned out, Glider 15P sustained last minute damage to her tail wing and another aircraft was sort. The new gilder had not fitted been with a horse-stall and so Pte. Dermody and Jean had to stand down and were later flown into Broadway by Dakota a few days later.

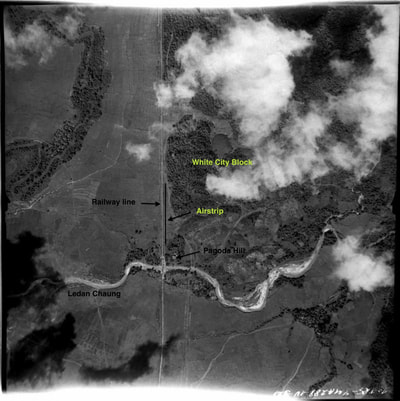

Sean was never far from Brigadier Calvert's side during the early months of Operation Thursday. He was with him as 77th Brigade set up the defences for the first Chindit stronghold at Broadway and fought alongside his commander at Pagoda Hill on the 13th March 1944. This action against the Japanese, who were defending a 70 ft. hill at a place called Henu, ended in a bloody and almost medieval hand to hand battle with the enemy in which no quarter was given, or indeed asked by either side. Shortly after this action, the Chindits set up their second stronghold adjacent to the railway line at Henu. This block was eventually given the codename of White City, due to the large amount of white silk parachutes from Chindit supply drops that adorned the trees in the location.

Not long afterwards, on the 21st March, the Japanese returned to White City and put in a full-blooded attack on the stronghold. From his book, Fighting Mad, Mike Calvert recalls this incident which includes some memories of Sean Dermody:

Again it was the South Staffords who bore the brunt of the fighting and during the night the Japs got a foothold on two positions within the White City perimeter, albeit at great loss to themselves. Our 3-inch mortars broke up attacks on other defence sectors but intermittent fighting went on for most of the night. Towards dawn Colonel Richards of the South Staffords asked me for two platoons to launch a counter-attack on the Japs who had broken through. I sent him the men he wanted and at first light he led them himself in a whirlwind charge which drove the enemy from White City and restored our defence position. The Colonel had shown outstanding courage but he was badly wounded in the chest.

I went forward to see what damage the Japs had done and, as always, L/Cpl. Young and Paddy Dermody were with me. We had named one of our hills, Bare Hill, because most of the trees on its slopes had been cut down, and as we went up it Paddy shouted 'Look out, sir,' and gave me a shove. At the same time he fell himself, badly wounded in the groin. I charged round a tree trunk and emptied my revolver into a wounded Jap who had fired at us, then Young and I carried Paddy down to the dressing station. Bare Hill was supposed to be clear of the enemy but I suspected more were there so I sent in the Gurkhas to clear it. They killed eleven Japs who had stayed behind either because they were wounded or because they wanted to take some of us with them before committing suicide. They could have caused a lot of trouble if we hadn't found them so quickly.

Back at the dressing station our two doctors were doing a magnificent job, working non-stop on the wounded and up to their elbows in blood. Our padres were helping to comfort the men and I spoke to some of them, including Colonel Richards and Paddy, who was in great pain. It was sad for me to see him like that, for he was a great little man. He was a former jockey who had joined the Irish Free State Army and became a Sergeant. In 1940 he decided the British needed a bit of strengthening from the Irish and marched his whole platoon on to the boat for Liverpool, where they all volunteered for the King's (Liverpool) Regiment.

When the King's joined the Chindits Wingate took Paddy as his groom and he came to me later. He taught me a lot about riding. I sat in the saddle with my toes out, military style. 'Never ride like that, sir,' he said, 'it's so easy for another rider to tip you off.' He came up alongside me, put his foot under mine and the next moment I was on the ground. 'You see what I mean, sir,' Paddy said with rather more than his usual touch of brogue, for I was a Brigadier and he was only an Acting Corporal. He helped me up. 'I could never have done that if you kept your toes down.'

My pony Jean and several others had been flown in with the mules and in some parts of the jungle — not the really dense stuff — I would move around from unit to unit by pony. We always carried four-second grenades and Paddy and I and a few others had perfected a method of throwing them while riding. We had hooks fixed on to our saddles so that we could get the pin out with one hand while keeping hold of the reins with the other.

We put this into practice one day when I was out with Paddy and several others, about six in all, in the area around White City. We came upon a party of Japs quite suddenly. They far outnumbered us and it was a moment for swift decision. We spurred on our ponies and raced past the enemy patrol, hurling grenades as fast as we could before they had a chance to stop us. We went flat out and never looked back, in case more Japs were around, but we must have done quite a lot of damage and it was pleasing to know that the time we had spent working on this exercise had now paid off. It must have been the last cavalry charge of the British Army!

The fierce fighting around White City went on for another day or so, but by the 23rd the Japs had retired, beaten, to Mawlu. Once again close air support had helped us enormously; once again our casualties were high. We had thirty-four killed, including six officers, and forty-two wounded. Our consolation was that we had inflicted at least twice as many casualties on the Japs.

Seen below is a photograph taken from Pagoda Hill at Henu in 2008. It shows the outline of the White City stronghold and the railway line to the left hand side as we look at the image.

Sean was never far from Brigadier Calvert's side during the early months of Operation Thursday. He was with him as 77th Brigade set up the defences for the first Chindit stronghold at Broadway and fought alongside his commander at Pagoda Hill on the 13th March 1944. This action against the Japanese, who were defending a 70 ft. hill at a place called Henu, ended in a bloody and almost medieval hand to hand battle with the enemy in which no quarter was given, or indeed asked by either side. Shortly after this action, the Chindits set up their second stronghold adjacent to the railway line at Henu. This block was eventually given the codename of White City, due to the large amount of white silk parachutes from Chindit supply drops that adorned the trees in the location.

Not long afterwards, on the 21st March, the Japanese returned to White City and put in a full-blooded attack on the stronghold. From his book, Fighting Mad, Mike Calvert recalls this incident which includes some memories of Sean Dermody:

Again it was the South Staffords who bore the brunt of the fighting and during the night the Japs got a foothold on two positions within the White City perimeter, albeit at great loss to themselves. Our 3-inch mortars broke up attacks on other defence sectors but intermittent fighting went on for most of the night. Towards dawn Colonel Richards of the South Staffords asked me for two platoons to launch a counter-attack on the Japs who had broken through. I sent him the men he wanted and at first light he led them himself in a whirlwind charge which drove the enemy from White City and restored our defence position. The Colonel had shown outstanding courage but he was badly wounded in the chest.

I went forward to see what damage the Japs had done and, as always, L/Cpl. Young and Paddy Dermody were with me. We had named one of our hills, Bare Hill, because most of the trees on its slopes had been cut down, and as we went up it Paddy shouted 'Look out, sir,' and gave me a shove. At the same time he fell himself, badly wounded in the groin. I charged round a tree trunk and emptied my revolver into a wounded Jap who had fired at us, then Young and I carried Paddy down to the dressing station. Bare Hill was supposed to be clear of the enemy but I suspected more were there so I sent in the Gurkhas to clear it. They killed eleven Japs who had stayed behind either because they were wounded or because they wanted to take some of us with them before committing suicide. They could have caused a lot of trouble if we hadn't found them so quickly.

Back at the dressing station our two doctors were doing a magnificent job, working non-stop on the wounded and up to their elbows in blood. Our padres were helping to comfort the men and I spoke to some of them, including Colonel Richards and Paddy, who was in great pain. It was sad for me to see him like that, for he was a great little man. He was a former jockey who had joined the Irish Free State Army and became a Sergeant. In 1940 he decided the British needed a bit of strengthening from the Irish and marched his whole platoon on to the boat for Liverpool, where they all volunteered for the King's (Liverpool) Regiment.

When the King's joined the Chindits Wingate took Paddy as his groom and he came to me later. He taught me a lot about riding. I sat in the saddle with my toes out, military style. 'Never ride like that, sir,' he said, 'it's so easy for another rider to tip you off.' He came up alongside me, put his foot under mine and the next moment I was on the ground. 'You see what I mean, sir,' Paddy said with rather more than his usual touch of brogue, for I was a Brigadier and he was only an Acting Corporal. He helped me up. 'I could never have done that if you kept your toes down.'

My pony Jean and several others had been flown in with the mules and in some parts of the jungle — not the really dense stuff — I would move around from unit to unit by pony. We always carried four-second grenades and Paddy and I and a few others had perfected a method of throwing them while riding. We had hooks fixed on to our saddles so that we could get the pin out with one hand while keeping hold of the reins with the other.

We put this into practice one day when I was out with Paddy and several others, about six in all, in the area around White City. We came upon a party of Japs quite suddenly. They far outnumbered us and it was a moment for swift decision. We spurred on our ponies and raced past the enemy patrol, hurling grenades as fast as we could before they had a chance to stop us. We went flat out and never looked back, in case more Japs were around, but we must have done quite a lot of damage and it was pleasing to know that the time we had spent working on this exercise had now paid off. It must have been the last cavalry charge of the British Army!

The fierce fighting around White City went on for another day or so, but by the 23rd the Japs had retired, beaten, to Mawlu. Once again close air support had helped us enormously; once again our casualties were high. We had thirty-four killed, including six officers, and forty-two wounded. Our consolation was that we had inflicted at least twice as many casualties on the Japs.

Seen below is a photograph taken from Pagoda Hill at Henu in 2008. It shows the outline of the White City stronghold and the railway line to the left hand side as we look at the image.

The casualties from the Battle at Op Hill including Corporal Dermody, were flown out of White City by the light planes of the United States Air Force. From his other book entitled, Prisoners of Hope, Mike Calvert remembered his thoughts and feelings from that time:

It was hot, wet and sticky as we moved slowly and fitfully along the valley away from White City. Now that we were on the move again I could not help thinking of the casualties we had taken. I had received from Paddy Ryan in hospital a letter in which he could not disguise the pain he was in, but he wished us good hunting, and said that he had been proud to be with us.

I was told that he, Colonel Richards and Paddy Dermody were all in the Special Forces Hospital in Sylhet under Matron McGearey, who had looked after us the year before and who had nursed Wingate back to health after his typhoid in 1942. After Wingate's death, this was one of the first of his structures to be torn down. These three men, who had been undergoing penicillin treatment — the penicillin we were obtaining from the Americans, as penicillin had not yet been allotted to the Burma theatre — were dragged off to the hell-hole of Dacca, a most unhealthy place with a very bad reputation amongst the troops as a death centre, where, taken off penicillin, they had died. This was not a very good omen as to how Special Force would be treated now that the influence of Wingate had departed.

NB. General Wingate had been killed in an aircraft crash on March 24th 1944.

Corporal Sean Dermody died on the 6th July 1944. It seems unlikely that he perished inside Dacca Military Hospital, as suggested by Brigadier Calvert in his book, Prisoners of Hope. I only say this because Sean is buried in Calcutta Bhowanipore Cemetery and this is located nearly 200 miles from the city of Dacca, situated in present-day Bangladesh. There is also another clue to his place of death in the 77th Brigade Rear Base War diary, where an entry, which is fully transcribed in the next section, places him at the 47th British General Hospital in Calcutta on the 6th July.

The following epitaph can be read upon his gravestone at the cemetery in Calcutta and as great-nephew Tom O'Connor mentioned earlier, it is likely that his parents and family were involved in the choosing of these words:

It was hot, wet and sticky as we moved slowly and fitfully along the valley away from White City. Now that we were on the move again I could not help thinking of the casualties we had taken. I had received from Paddy Ryan in hospital a letter in which he could not disguise the pain he was in, but he wished us good hunting, and said that he had been proud to be with us.

I was told that he, Colonel Richards and Paddy Dermody were all in the Special Forces Hospital in Sylhet under Matron McGearey, who had looked after us the year before and who had nursed Wingate back to health after his typhoid in 1942. After Wingate's death, this was one of the first of his structures to be torn down. These three men, who had been undergoing penicillin treatment — the penicillin we were obtaining from the Americans, as penicillin had not yet been allotted to the Burma theatre — were dragged off to the hell-hole of Dacca, a most unhealthy place with a very bad reputation amongst the troops as a death centre, where, taken off penicillin, they had died. This was not a very good omen as to how Special Force would be treated now that the influence of Wingate had departed.

NB. General Wingate had been killed in an aircraft crash on March 24th 1944.

Corporal Sean Dermody died on the 6th July 1944. It seems unlikely that he perished inside Dacca Military Hospital, as suggested by Brigadier Calvert in his book, Prisoners of Hope. I only say this because Sean is buried in Calcutta Bhowanipore Cemetery and this is located nearly 200 miles from the city of Dacca, situated in present-day Bangladesh. There is also another clue to his place of death in the 77th Brigade Rear Base War diary, where an entry, which is fully transcribed in the next section, places him at the 47th British General Hospital in Calcutta on the 6th July.

The following epitaph can be read upon his gravestone at the cemetery in Calcutta and as great-nephew Tom O'Connor mentioned earlier, it is likely that his parents and family were involved in the choosing of these words:

Under the shadow of

Thy Sacred Heart,

Dear Jesus, may he rest.

Sorrowing mother and family.

Thy Sacred Heart,

Dear Jesus, may he rest.

Sorrowing mother and family.

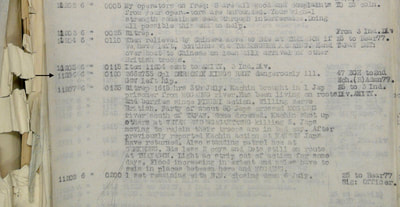

It is clear from the many entries in the 77th Brigade HQ War diary, that Brigadier Calvert and others had been continuously enquiring about the health of their former comrade, Paddy Dermody. On the 30th May 1944, a message was sent from 77 Brigade HQ to the 17th British General Hospital at Dacca, simply stating:

Whereabouts urgently required of Corporal Dermody.

On the 6th July at 0130 hours, a message came into Brigade Rear Base from the 47th British General Hospital (Calcutta), stating:

Corporal Dermody, the King's Regiment, dangerously ill, gunshot wound to the left hip.

Sadly, just a few short hours later another message came into Rear Base HQ:

0840 hours: 3662755 Corporal Dermody has died of wounds in hospital.

At 1245 hours on the 7th July, Rear HQ sent the following message to 77 Brigade:

Regret to announce the death of Corporal Dermody.

One can only imagine the sadness felt on hearing this news, by all those that had known Cpl. Dermody during his Chindit days and in particular by Brigadier Calvert, whose life Sean had so bravely saved at White City. Shown below is another gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Tom O'Connor and his family for all their help in bringing this important Chindit story to these website pages. There can be no doubt that Sean Dermody was a special and much loved character and an exceedingly brave man. It is not often that a Corporal receives mention in a British Army War diary and less still in later books about the campaign in which he fought; to his credit, Sean features in both these sets of writings, not once, but many times.

Update 05/04/2020.

Sean Dermody is also remembered on the Longford Historical Society's Facebook page:

www.facebook.com/Longford-Historical-Society-269890479807793/?tn-str=k*F

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2017.

Update 05/04/2020.

Sean Dermody is also remembered on the Longford Historical Society's Facebook page:

www.facebook.com/Longford-Historical-Society-269890479807793/?tn-str=k*F

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2017.