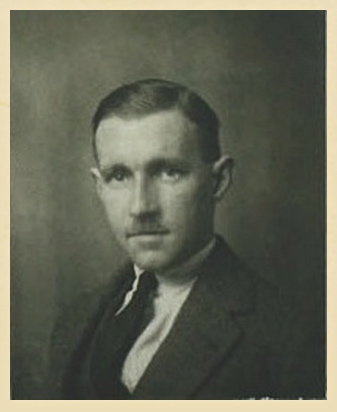

Signalman, L/Corporal Eric Hutchins

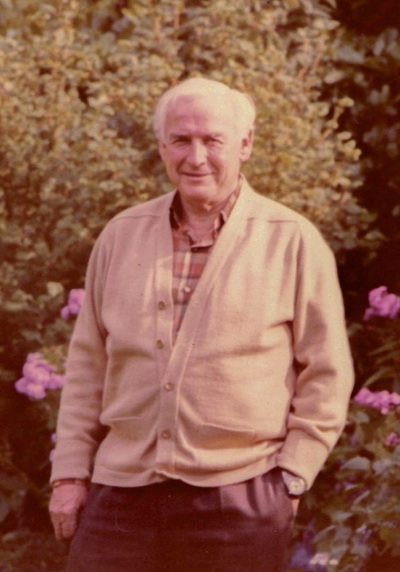

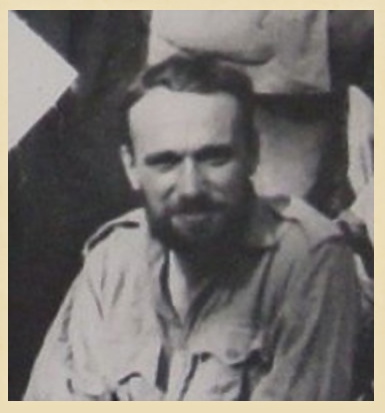

Eric Hutchins after his return to India.

Eric Hutchins after his return to India.

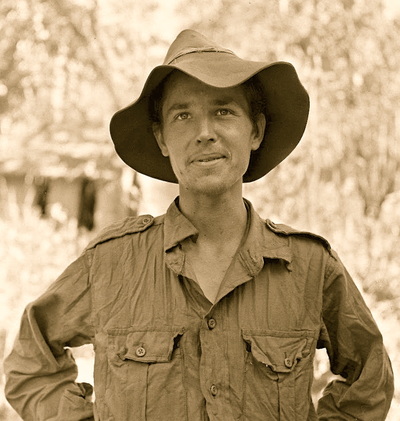

Probably, one of the most well known images from the first Wingate expedition, is that of Signalman Eric Hutchins, photographed at Imphal just after his safe return from Burma in late April 1943. Just over 50 years later, in January 1995, Eric sat down at the Imperial War Museum in London with interviewer Conrad Wood and spoke about his experiences during WW2 and in particular his participation on Operation Longcloth.

To listen to Eric's recollections first hand, please click on the following link:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80014479

Eric William Frederick Hutchins was born in Tooting, London during the first quarter of 1921. He recalled that during his childhood his father had been in the Royal Navy for a time, before becoming a Male Nurse. Like so many of his working class contemporaries, Eric Hutchins left school at the age of 14 and after a succession of short-term jobs, settled down in the textile trade as a leatherworker.

In 1936, he decided to join his local Territorial Army unit, looking for, as Eric put it: "a feeling of adventure and a sense of service to his country." It was becoming abundantly clear that war with Germany, under the aggressive and expansive leadership of Adolf Hitler was now inevitable. Eric was posted to the Royal Corps of Signals, 1st City of London Division (56 Divisional Signals) and began his training at the RCOS base in London's Docklands.

He enjoyed his TA days and received excellent training in wireless communications and associated signalling techniques. All this he remembered, for the princely sum of £5 per year in wages. Eric was enjoying a drink with his mates in the Prince of Orange public house in Rotherhithe, when the news came through that war had been declared. Although he was extremely tall and very well built, Eric was too young to be allowed to serve overseas and so missed out on joining the BEF in France, or taking part in the British raids in Norway. He spent the first year of the war in Kent, involved primarily in coastal defence duties at Eastbourne. He frustratingly remembered this period as "dull, just like being on a long summer holiday as a schoolboy."

During September 1940, the country was constantly on an emergency footing, fully expecting to see German paratroops dropping from the sky at any moment. Eric recalled watching dogfights between pilots from the RAF and the Luftwaffe overhead on numerous occasions and whilst stationed at Dover, experiencing the long-range German artillery fire from the batteries at Cap Gris Nez on the French coast. After being posted to another barracks, this time in Suffolk, a disheartened Eric decided to volunteer for the Commandos. He was accepted and travelled up to Scotland and commenced his special forces training at Achnacarry.

In late 1941, he was given notice of a transfer to a newly formed unit, 142 Company (Royal Engineers), which was then posted overseas to work on a secret mission in China. Eric travelled aboard the converted cargo ship, the Nieuw Holland and with some humour recalled the terrible conditions he experienced on the voyage out to Bombay. The Nieuw Holland, part of Convoy WS 17 which set sail from Liverpool Docks on the 23rd March 1942, carried over 3000 troops in very cramped quarters, consisting of strung hammocks across what was during the daytime, the men's mess hall. To make matters worse, Eric suffered for the first part of the voyage with raging toothache, which was only dealt with some weeks later, when the convoy docked at Capetown and the offending tooth was removed by a local dentist.

Finally arriving at Bombay in mid-May, Eric was sent to the Signals Depot at Agra, where he had the misfortune in contracting dysentery and spent the next six weeks in hospital. His enforced stay in hospital resulted in him missing the Commando mission to China, in which his comrades assisted the Chinese Army in their fight against the Japanese. After recovering from his illness, Eric was sent to Mhow for an intense Signals training course, working for the most part with the FS6 Wireless Set, a new radio system developed in Australia during the early years of WW2. It was whilst training at Mhow that Eric first came into contact with Lieutenant Kenneth Spurlock, also of the Royal Corps of Signals.

Later, he was transferred to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at their jungle training camp at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. Here he joined Brigade Head Quarters and was promoted to HQ Wireless Operator under the command of none other than Lt. Spurlock. Once again he worked with the FS6 Radio and was impressed by the set and its ability to continue to work, even under the most exacting of conditions. He remembered how his radio had been accidentally dropped into a river during one training exercise, but after only a few hours drying out, had worked perfectly well once more. He remarked that this was in direct contrast to the wireless equipment that the RAF were using, which was poor and failed dramatically when in use in Burma. When asked why he had been given the vitally important role of Brigade HQ Wireless Operator, Eric replied: I don't know why he (Spurlock) chose me. I was pretty good at reading and sending morse, at 25-30 words per minute. I probably was the most experienced signaller in the Brigade at that time and seemed to have the ability, or luck to always get through to India, when we were out in the jungle in Burma.

Working within Brigade HQ Eric often came into contact with Brigadier Wingate. He was genuinely impressed and even inspired by his new commanders methods and ideas. Eric recounted: "What I liked most was that he frowned on unnecessary Army discipline and bull-shit."

In January 1943, many of the Signallers from 142 Company RE, that had previously served with the Chinese on the 204 Military Mission joined up with 77th Brigade as it made the final preparations for the move up to the Assam-Burmese border.

Seen below are some images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

To listen to Eric's recollections first hand, please click on the following link:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80014479

Eric William Frederick Hutchins was born in Tooting, London during the first quarter of 1921. He recalled that during his childhood his father had been in the Royal Navy for a time, before becoming a Male Nurse. Like so many of his working class contemporaries, Eric Hutchins left school at the age of 14 and after a succession of short-term jobs, settled down in the textile trade as a leatherworker.

In 1936, he decided to join his local Territorial Army unit, looking for, as Eric put it: "a feeling of adventure and a sense of service to his country." It was becoming abundantly clear that war with Germany, under the aggressive and expansive leadership of Adolf Hitler was now inevitable. Eric was posted to the Royal Corps of Signals, 1st City of London Division (56 Divisional Signals) and began his training at the RCOS base in London's Docklands.

He enjoyed his TA days and received excellent training in wireless communications and associated signalling techniques. All this he remembered, for the princely sum of £5 per year in wages. Eric was enjoying a drink with his mates in the Prince of Orange public house in Rotherhithe, when the news came through that war had been declared. Although he was extremely tall and very well built, Eric was too young to be allowed to serve overseas and so missed out on joining the BEF in France, or taking part in the British raids in Norway. He spent the first year of the war in Kent, involved primarily in coastal defence duties at Eastbourne. He frustratingly remembered this period as "dull, just like being on a long summer holiday as a schoolboy."

During September 1940, the country was constantly on an emergency footing, fully expecting to see German paratroops dropping from the sky at any moment. Eric recalled watching dogfights between pilots from the RAF and the Luftwaffe overhead on numerous occasions and whilst stationed at Dover, experiencing the long-range German artillery fire from the batteries at Cap Gris Nez on the French coast. After being posted to another barracks, this time in Suffolk, a disheartened Eric decided to volunteer for the Commandos. He was accepted and travelled up to Scotland and commenced his special forces training at Achnacarry.

In late 1941, he was given notice of a transfer to a newly formed unit, 142 Company (Royal Engineers), which was then posted overseas to work on a secret mission in China. Eric travelled aboard the converted cargo ship, the Nieuw Holland and with some humour recalled the terrible conditions he experienced on the voyage out to Bombay. The Nieuw Holland, part of Convoy WS 17 which set sail from Liverpool Docks on the 23rd March 1942, carried over 3000 troops in very cramped quarters, consisting of strung hammocks across what was during the daytime, the men's mess hall. To make matters worse, Eric suffered for the first part of the voyage with raging toothache, which was only dealt with some weeks later, when the convoy docked at Capetown and the offending tooth was removed by a local dentist.

Finally arriving at Bombay in mid-May, Eric was sent to the Signals Depot at Agra, where he had the misfortune in contracting dysentery and spent the next six weeks in hospital. His enforced stay in hospital resulted in him missing the Commando mission to China, in which his comrades assisted the Chinese Army in their fight against the Japanese. After recovering from his illness, Eric was sent to Mhow for an intense Signals training course, working for the most part with the FS6 Wireless Set, a new radio system developed in Australia during the early years of WW2. It was whilst training at Mhow that Eric first came into contact with Lieutenant Kenneth Spurlock, also of the Royal Corps of Signals.

Later, he was transferred to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at their jungle training camp at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. Here he joined Brigade Head Quarters and was promoted to HQ Wireless Operator under the command of none other than Lt. Spurlock. Once again he worked with the FS6 Radio and was impressed by the set and its ability to continue to work, even under the most exacting of conditions. He remembered how his radio had been accidentally dropped into a river during one training exercise, but after only a few hours drying out, had worked perfectly well once more. He remarked that this was in direct contrast to the wireless equipment that the RAF were using, which was poor and failed dramatically when in use in Burma. When asked why he had been given the vitally important role of Brigade HQ Wireless Operator, Eric replied: I don't know why he (Spurlock) chose me. I was pretty good at reading and sending morse, at 25-30 words per minute. I probably was the most experienced signaller in the Brigade at that time and seemed to have the ability, or luck to always get through to India, when we were out in the jungle in Burma.

Working within Brigade HQ Eric often came into contact with Brigadier Wingate. He was genuinely impressed and even inspired by his new commanders methods and ideas. Eric recounted: "What I liked most was that he frowned on unnecessary Army discipline and bull-shit."

In January 1943, many of the Signallers from 142 Company RE, that had previously served with the Chinese on the 204 Military Mission joined up with 77th Brigade as it made the final preparations for the move up to the Assam-Burmese border.

Seen below are some images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Brigade HQ, in the company of Chindit Columns 7 and 8 crossed the Chindwin River close to the village of Tonhe in mid-February 1943. All of Eric's wireless equipment was carried by Animal Transport in the form of mules. He recalled with some humour and affection that: "Mules were terrific, once you broke them in, they were totally loyal and never let you down. I crossed the Chindwin in a canoe, with the mules being led behind."

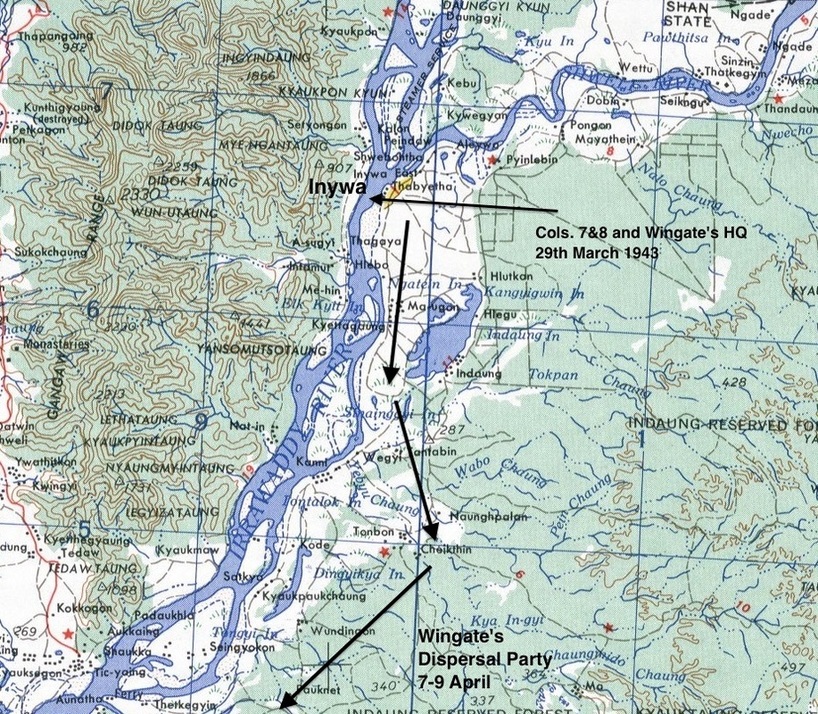

The Brigade then moved on to a arranged supply drop at a place called Tonmakeng. Then passed over the sparsely inhabited area of the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment, before dropping down into the valleys around Banmauk. Eric was successful in most of his radio signals during this initial period behind enemy lines. However, after crossing the Irrawaddy and moving further east, it became more and more difficult to contact Rear Base and supply drops became more precarious to organise and then carry out. Added to this, the Brigade were now too far east for the Dakotas sent to drop their supplies to enjoy the security of fighter escorts. On the 24th March, Wingate was instructed by India Command to return his troops to India. By the 29th March, Brigade HQ was back on the east banks of the Irrawaddy, close to the town of Inywa.

Eric Hutchins was sent over in one of the first boats to help form a bridgehead on the far bank. As these lead boats approached the west bank they came under heavy enemy machine gun and mortar fire and many men were killed or wounded. Eric and his RCOS colleague Corporal Crawford managed to turn their boat around and paddled back to the east bank. On reaching the shoreline, both men jumped out of their boat and began running back along the sand, suddenly a single shot rang out and Corporal Crawford fell to the ground. He had been shot in the head by a sniper's bullet and had died instantly.

Wingate decided to call general dispersal that evening and sent both 7 & 8 Columns away. He then split his own Brigade HQ into several dispersal groups of around 50-60 men in each. Eric Hutchins remained with the Brigadier, who then moved his party deeper into the dense bamboo jungle close to the river near Inywa. Here they waited for around 10 days, in the hope that the situation would calm down and the Japanese would move away. Eric recalled: "I found this time very exacting and boring, we could not talk in more than a whisper and the mules had to be kept quiet. Eventually we killed all the mules and broke up our large equipment and dumped it in the jungle. Although we were concerned about the Japanese still being about, It was a relief to be on the move again."

On 7th April, Wingate made a second attempt at crossing the Irrawaddy, 25 miles south of Inywa. For two days they searched the bank for boats, but Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles could only find one boat and this could hold only seven people at a time. They began crossing late in the afternoon, but quite suddenly automatic fire was heard from the north and the native boatman made off with the boat, leaving the last party stranded on the east bank.

The Brigade then moved on to a arranged supply drop at a place called Tonmakeng. Then passed over the sparsely inhabited area of the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment, before dropping down into the valleys around Banmauk. Eric was successful in most of his radio signals during this initial period behind enemy lines. However, after crossing the Irrawaddy and moving further east, it became more and more difficult to contact Rear Base and supply drops became more precarious to organise and then carry out. Added to this, the Brigade were now too far east for the Dakotas sent to drop their supplies to enjoy the security of fighter escorts. On the 24th March, Wingate was instructed by India Command to return his troops to India. By the 29th March, Brigade HQ was back on the east banks of the Irrawaddy, close to the town of Inywa.

Eric Hutchins was sent over in one of the first boats to help form a bridgehead on the far bank. As these lead boats approached the west bank they came under heavy enemy machine gun and mortar fire and many men were killed or wounded. Eric and his RCOS colleague Corporal Crawford managed to turn their boat around and paddled back to the east bank. On reaching the shoreline, both men jumped out of their boat and began running back along the sand, suddenly a single shot rang out and Corporal Crawford fell to the ground. He had been shot in the head by a sniper's bullet and had died instantly.

Wingate decided to call general dispersal that evening and sent both 7 & 8 Columns away. He then split his own Brigade HQ into several dispersal groups of around 50-60 men in each. Eric Hutchins remained with the Brigadier, who then moved his party deeper into the dense bamboo jungle close to the river near Inywa. Here they waited for around 10 days, in the hope that the situation would calm down and the Japanese would move away. Eric recalled: "I found this time very exacting and boring, we could not talk in more than a whisper and the mules had to be kept quiet. Eventually we killed all the mules and broke up our large equipment and dumped it in the jungle. Although we were concerned about the Japanese still being about, It was a relief to be on the move again."

On 7th April, Wingate made a second attempt at crossing the Irrawaddy, 25 miles south of Inywa. For two days they searched the bank for boats, but Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles could only find one boat and this could hold only seven people at a time. They began crossing late in the afternoon, but quite suddenly automatic fire was heard from the north and the native boatman made off with the boat, leaving the last party stranded on the east bank.

Eric Hutchins, now suffering badly with dysentery was with the last party waiting to cross the river, together with him were; Squadron Leader Longmore, Flight Lieutenant Tooth, Flight Sergeant Fidler, Lieutenant Rose of the Gurkhas and Private Dermody and Private Weston of the King's.

Eric remembered:

The first six boat parties made their way safely to the opposite bank. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the opposite bank we could find no trace of the others. Wingate's excuse when we met him later, was he 'thought' we had been captured by the Japanese, whereas he had abandoned us without maps or any means of finding our way back to our own lines. Such is my regard for a commander who later became world famous.

So we set out west only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Our problems now really began, because we could not find a suitable boat. Eventually we found a boat that had seen better days and decided to take a chance crossing at night, using our rifles as oars. Of course the inevitable happened and the boat capsized.

I and others swam to the west shore, where we had to rescue two of our party who were clutching on to a floating plant because they could not swim. At light of day we found that Squadron Leader Longmore was missing. Later at the end of the war I found out that he had remained clutching the boat and floated down river and was eventually captured. We found we were on another island and right opposite a very large village and most of the inhabitants walked across the shallow water to the island, presumably out of curiosity.

We had lost everything when the boat capsized and had no arms to defend ourselves, except that I still had a hand grenade. We went with the villagers and enjoyed a meal of rice and obtained two sacks of rice, cooking pans, a flint stone to make a fire, salt and juggery, the latter unrefined sugar.

Suddenly there was a commotion in the village and the locals started to disperse, which was a signal to us that the Japs had arrived. We made a quick retreat and proceeded to climb the hills behind the village and make our way westwards. Our progress after that was mainly at night, avoiding paths and villages. I remember the beautiful clear moonlit nights with the stars to guide us. I often look for a constellation set at dead 270 degrees which we used as our direction arrow as we kept walking westwards.

Daytime was spent trying to sleep in the intense heat with no water, setting out at dusk to find water and cook a meal. I was suffering severely from dysentery, but somehow raised the strength to carry on. As we neared the Chindwin we found a small chaung in which were some pools of water containing fish. We caught one by swimming under water, but then became greedy and thought if we threw my grenade into the water we could have a real feast. This was not to be because the grenade failed to explode as I had forgotten to prime it.

On seeing the river valley of the Chindwin we now became over-confident and started to abandon our policy of avoiding footpaths. On rounding a bend we ran into a Japanese sentry guarding the path. We immediately plunged into the jungle to our left, but Weston was captured because he was too weak to react quickly. We were forced to stand in a marsh for thirty-six hours while the Japs set fire to it to try to draw us out. Meanwhile we could hear the screams of Weston as they slowly tortured him to death with their bayonets.

On the second night we came out of the marsh only to walk straight through the Jap occupied village. We walked on down the path leading to the Chindwin and then, practising the usual dispersal drill on leaving a path, hid in the jungle nearby. Within fifteen minutes a party of Japs came down the track, following our footprints by torch light. Fortunately for us they hesitated where our footprints finished and then carried on. This was our cue and we retreated deeper into the jungle.

Within half an hour they were back searching the spot we had left. We were now under real pressure and headed for the Chindwin, but could not find a boat to cross. We were walking along the path on the river bank and came to a small clearing with Lieutenant Rose leading. He suddenly turned round and yelled Japs' and in the sudden rush to retreat I fell over. I scrambled to my feet, leaving behind the rice sack I was carrying. The others had a good fifty yards' start on me and machine gun bullets were whizzing all around. I think I broke the world record for 200 yards and reached the jungle on the opposite side of the clearing before the others.

Here we lost Lieutenant Rose and I heard after the war he was later captured and also survived the prison camp. We decided to regain the hills and walk northwards hoping there would be fewer Japs to encounter in that direction. We came upon a hut in the middle of a paddy field and found a native sitting inside. He immediately beckoned us to lie down in the paddy and pointed to a road about fifty yards away where Jap lorries were moving. He indicated to follow him crawling on our bellies to a small copse, it was here that our miracle occurred.

He brought us food twice a day for three days while we got our strength back. He could not get us a boat but when we drew bamboo poles he understood and on each night visit he brought two bamboo poles. Finally we had enough to make a raft and took them down to the river at the dead of night and our saviour tied them together. We had no money and could not reward him, but gave him a note saying how he had helped us and that he should be rewarded by the British if he produced the document.

This man, a complete stranger, possibly a Buddhist, displayed all the ethics of a Good Samaritan and has remained in my deepest thoughts all my life. That day in 1943 on the banks of the Chindwin I learned to believe in miracles.

I was the only strong swimmer and pushed the raft from the rear. Some of the other survivors were too weak to swim and had to be hauled back on the raft. Eventually we reached the other side and rested for the night. In the morning we walked into the nearest village which was occupied by Gurkhas.

Wingate was my hero before the campaign, but after his deliberate abandonment on the east bank of the Irrawaddy I know he only considered his own safety and not others. He would deliberately abandon anyone whom he considered to be a handicap. This was proved later when our signals officer, Ken Spurlock, who was in Wingate's boat party, was abandoned in a village not far from the Chindwin because he was weak with dysentery. I was weak with dysentery but my companions never abandoned me.

Seen below is a galley of photographs depicting some of the men present with Eric Hutchins in that last boat at the Irrawaddy River. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Eric remembered:

The first six boat parties made their way safely to the opposite bank. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the opposite bank we could find no trace of the others. Wingate's excuse when we met him later, was he 'thought' we had been captured by the Japanese, whereas he had abandoned us without maps or any means of finding our way back to our own lines. Such is my regard for a commander who later became world famous.

So we set out west only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Our problems now really began, because we could not find a suitable boat. Eventually we found a boat that had seen better days and decided to take a chance crossing at night, using our rifles as oars. Of course the inevitable happened and the boat capsized.

I and others swam to the west shore, where we had to rescue two of our party who were clutching on to a floating plant because they could not swim. At light of day we found that Squadron Leader Longmore was missing. Later at the end of the war I found out that he had remained clutching the boat and floated down river and was eventually captured. We found we were on another island and right opposite a very large village and most of the inhabitants walked across the shallow water to the island, presumably out of curiosity.

We had lost everything when the boat capsized and had no arms to defend ourselves, except that I still had a hand grenade. We went with the villagers and enjoyed a meal of rice and obtained two sacks of rice, cooking pans, a flint stone to make a fire, salt and juggery, the latter unrefined sugar.

Suddenly there was a commotion in the village and the locals started to disperse, which was a signal to us that the Japs had arrived. We made a quick retreat and proceeded to climb the hills behind the village and make our way westwards. Our progress after that was mainly at night, avoiding paths and villages. I remember the beautiful clear moonlit nights with the stars to guide us. I often look for a constellation set at dead 270 degrees which we used as our direction arrow as we kept walking westwards.

Daytime was spent trying to sleep in the intense heat with no water, setting out at dusk to find water and cook a meal. I was suffering severely from dysentery, but somehow raised the strength to carry on. As we neared the Chindwin we found a small chaung in which were some pools of water containing fish. We caught one by swimming under water, but then became greedy and thought if we threw my grenade into the water we could have a real feast. This was not to be because the grenade failed to explode as I had forgotten to prime it.

On seeing the river valley of the Chindwin we now became over-confident and started to abandon our policy of avoiding footpaths. On rounding a bend we ran into a Japanese sentry guarding the path. We immediately plunged into the jungle to our left, but Weston was captured because he was too weak to react quickly. We were forced to stand in a marsh for thirty-six hours while the Japs set fire to it to try to draw us out. Meanwhile we could hear the screams of Weston as they slowly tortured him to death with their bayonets.

On the second night we came out of the marsh only to walk straight through the Jap occupied village. We walked on down the path leading to the Chindwin and then, practising the usual dispersal drill on leaving a path, hid in the jungle nearby. Within fifteen minutes a party of Japs came down the track, following our footprints by torch light. Fortunately for us they hesitated where our footprints finished and then carried on. This was our cue and we retreated deeper into the jungle.

Within half an hour they were back searching the spot we had left. We were now under real pressure and headed for the Chindwin, but could not find a boat to cross. We were walking along the path on the river bank and came to a small clearing with Lieutenant Rose leading. He suddenly turned round and yelled Japs' and in the sudden rush to retreat I fell over. I scrambled to my feet, leaving behind the rice sack I was carrying. The others had a good fifty yards' start on me and machine gun bullets were whizzing all around. I think I broke the world record for 200 yards and reached the jungle on the opposite side of the clearing before the others.

Here we lost Lieutenant Rose and I heard after the war he was later captured and also survived the prison camp. We decided to regain the hills and walk northwards hoping there would be fewer Japs to encounter in that direction. We came upon a hut in the middle of a paddy field and found a native sitting inside. He immediately beckoned us to lie down in the paddy and pointed to a road about fifty yards away where Jap lorries were moving. He indicated to follow him crawling on our bellies to a small copse, it was here that our miracle occurred.

He brought us food twice a day for three days while we got our strength back. He could not get us a boat but when we drew bamboo poles he understood and on each night visit he brought two bamboo poles. Finally we had enough to make a raft and took them down to the river at the dead of night and our saviour tied them together. We had no money and could not reward him, but gave him a note saying how he had helped us and that he should be rewarded by the British if he produced the document.

This man, a complete stranger, possibly a Buddhist, displayed all the ethics of a Good Samaritan and has remained in my deepest thoughts all my life. That day in 1943 on the banks of the Chindwin I learned to believe in miracles.

I was the only strong swimmer and pushed the raft from the rear. Some of the other survivors were too weak to swim and had to be hauled back on the raft. Eventually we reached the other side and rested for the night. In the morning we walked into the nearest village which was occupied by Gurkhas.

Wingate was my hero before the campaign, but after his deliberate abandonment on the east bank of the Irrawaddy I know he only considered his own safety and not others. He would deliberately abandon anyone whom he considered to be a handicap. This was proved later when our signals officer, Ken Spurlock, who was in Wingate's boat party, was abandoned in a village not far from the Chindwin because he was weak with dysentery. I was weak with dysentery but my companions never abandoned me.

Seen below is a galley of photographs depicting some of the men present with Eric Hutchins in that last boat at the Irrawaddy River. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Eric Hutchins' invaluable audio account of his time on Operation Longcloth, adds yet more detail to the other connected stories on these website pages. To read more about the trials and tribulations of Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters in 1943, please click on any of the following links:

Wingate's Journey Home

Alan Fidler

Lieutenant Lewis William Rose

Flight-Lieutenant Albert Tooth

Lance Corporal 2573556 Eric Hutchins concludes his story, firstly with some more thoughts about Brigadier Wingate:

"At first he was my hero, but after the campaign he had become my great disappointment. I did not volunteer for any further campaigns with Wingate. I went into the Y Service, working on intercept signals at the 14th Army HQ."

Eric was repatriated to the United Kingdom shortly after the Japanese surrender in August 1945, but was not officially demobbed from the British Army until midway through 1946. After the war he enjoyed a successful career in the Police Force. One of the last things he mentioned during his conversations at the Imperial War Museum, was the sad and in his view unnecessary loss of so many of his RCOS comrades on Operation Longcloth:

"Some of my fellow Signallers just completely disappeared in Burma and were never heard of again. We were the guinea pigs, we were the people that the higher command learned through by their mistakes, and they did learn, because the second Chindit campaign was far better organised."

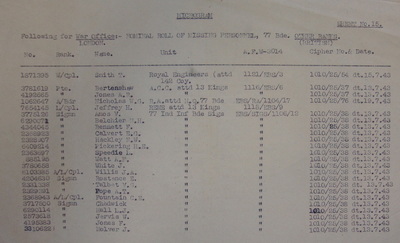

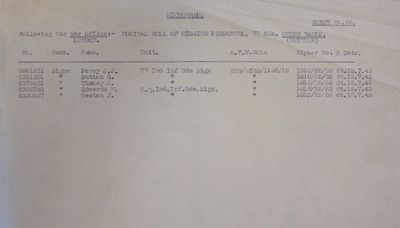

To end this story; seen below is a two page listing of those men from the Royal Corps of Signals, who were reported as missing in action during the first Chindit expedition in 1943, many of whose bodies or final resting places were never found. Please click on either image to bring ot forward on the page.

Wingate's Journey Home

Alan Fidler

Lieutenant Lewis William Rose

Flight-Lieutenant Albert Tooth

Lance Corporal 2573556 Eric Hutchins concludes his story, firstly with some more thoughts about Brigadier Wingate:

"At first he was my hero, but after the campaign he had become my great disappointment. I did not volunteer for any further campaigns with Wingate. I went into the Y Service, working on intercept signals at the 14th Army HQ."

Eric was repatriated to the United Kingdom shortly after the Japanese surrender in August 1945, but was not officially demobbed from the British Army until midway through 1946. After the war he enjoyed a successful career in the Police Force. One of the last things he mentioned during his conversations at the Imperial War Museum, was the sad and in his view unnecessary loss of so many of his RCOS comrades on Operation Longcloth:

"Some of my fellow Signallers just completely disappeared in Burma and were never heard of again. We were the guinea pigs, we were the people that the higher command learned through by their mistakes, and they did learn, because the second Chindit campaign was far better organised."

To end this story; seen below is a two page listing of those men from the Royal Corps of Signals, who were reported as missing in action during the first Chindit expedition in 1943, many of whose bodies or final resting places were never found. Please click on either image to bring ot forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, September 2016.