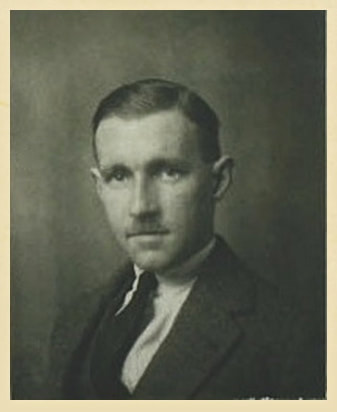

RAF Sergeant Maurice Holmes

Maurice Leslie Holmes.

Maurice Leslie Holmes.

Maurice Leslie Holmes was born on the 23rd April 1921 and was the son of Bernard and Esther Holmes from Thurcroft in Yorkshire. On the 5th November 2017, I received the following email contact from Amir Louka, who lives in the United States of America:

Hello, I am looking for any information you may have or be able to find in regards to my grandfather, Maurice Holmes. He was an RAF Radio Operator who served with the Chindits. He was present at least for the first operation and survived, but we are not sure if he was involved with the second. Many thanks.

I replied to Amir a few days later:

Dear Amir,

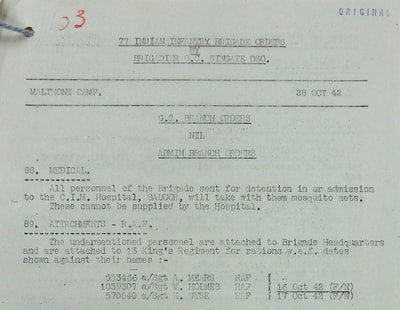

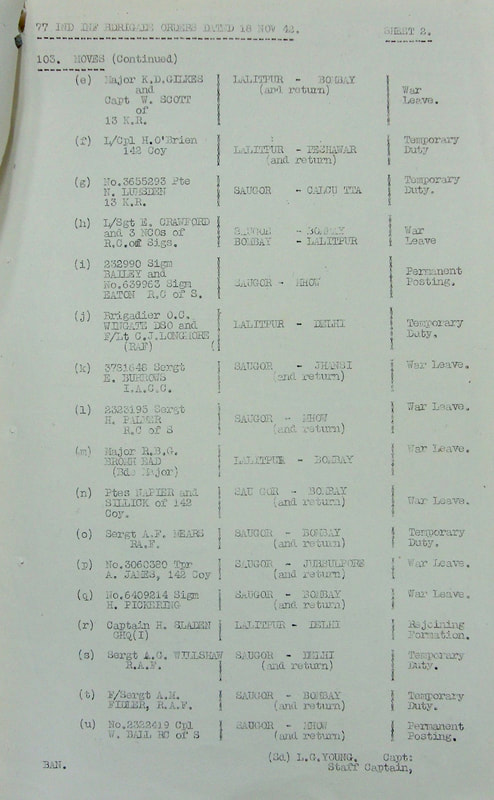

Thank you for your contact email via my website. I do have knowledge of a RAF Sergeant M. Holmes from one of the war diaries I have read. His RAF service number is given as 1039307 and he volunteered for the first Chindit operation, arriving at the training camp at Malthone in India on the 16th October 1942. According to an entry in the 142 Commando War diary, he was posted to Brigade Head Quarters, which was the command centre for the entire Chindit Brigade. This is sadly all I know about him, it is unclear which Column he served with inside Burma on Operation Longcloth, it may well be that he remained with Brigade HQ, in which case he was with Brigadier Wingate during the operation. I would be very interested to learn more about him and his life before and after WW2. If you possess a photograph of him that you would be willing to share, I would very much like to put this up on the website.

Over the coming days I received some more information from Amir, including one vital piece of information which confirmed in my mind, that Maurice had indeed served with Wingate's Brigade HQ on Operation Longcloth. This was mention of his best friend from his RAF days in India, RAF Sergeant Arthur Willshaw.

Amir continued:

Thanks so much for your quick reply Steve. That small bit of information from the War diary means the world to me. I never knew which column he was attached to, but if likely it was HQ I can now trace their movements from books and your website and learn more about his particular experiences. I've attached a photo of Maurice with his wife, Alma, who drove an ambulance in the ATS during the war. I'll have my mum write a bit about his pre/post war years as she will know more detail than me and I'll get that to you soon.

You may know more about his good friend, Arthur Willshaw, who was another RAF Signalman. My grandfather spoke of him fondly and often - as I understand it they made the trip out together after Wingate's order to disperse, but that may not be correct if Arthur (Arty) wasn't with HQ. They definitely spent a lot of time together in India during training. Unfortunately, much of my information comes from stories he told me as a child and teenager and my recollection isn't perfect, sadly he died of pancreatic cancer in 2007.

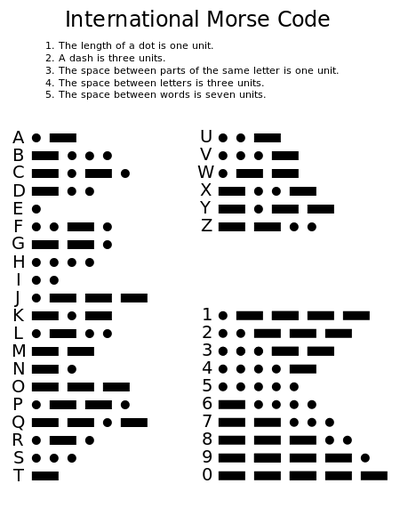

My grandfather grew up in the mining village of Moorends, near Doncaster. His father was a foreman in the local coal mine, but after developing black lung disease made his son swear to never set foot in a mine. Maurice volunteered for service in the RAF early in the war (as he told it, because he knew he'd get drafted and preferred their uniforms). He was selected for training as a Radio Operator and soon sailed to India where he was tasked with sending coded messages via morse code. In 1942 he was offered a pay raise and promotion from Corporal to Sergeant to participate in an upcoming mission - although details of the mission were not initially disclosed.

To his surprise he found himself at the Bush Warfare School with 142 Commando, who were preparing for Operation Longcloth. He had multiple interactions with Orde Wingate which he recalled fondly, although he pointed him out to be quite eccentric. It seems he may have been attached to Brigade HQ for some time. He took a photo of Wingate once, and gave him a copy, which he then found some 40 years later in a magazine. He survived crossing the Chindwin and Irrawaddy Rivers, and made it back to India, although he was suffering badly from malaria by that time.

Ultimately he made it home to England in February 1946 and married his pre-war sweetheart, Alma Teresa Bathurst, just two weeks later on the 23rd February. They ran a grocery story in Eyam village (the famous Plague Village) and raised a son, Malcolm, and a daughter, Julia. Maurice and Alma retired to Wakefield near Leeds where he lived the rest of his life. Although he frequently recounted his time in India and Burma he had clearly had his fill of adventure and never again left England. It wasn't until after his death in 2007 that I found his service book and learned that relatives could apply for medals owed. I am immensely proud of all he did and endured for his country, and his Burma Star will forever be one of our family's most treasured possessions, along with his kukri and bush hat.

Another story my mum just reminded me of and one of Grandad's favourites; was when he received an invitation to a garden party at the home of the Maharajah of Tikumgarh. Before Longcloth, he and a friend, possibly Arty Willshaw, were told about this party by others in the compound where they were based. They went together to the palace only to find it was a trick, and only officers had been invited. The sentry at the gate told them someone had been putting them on, but he decided to let them in anyway and they had a rare taste of luxury, enjoying the dancing, food and drinks. They returned to the base late in the evening and thanked the guys who had told them about the party, much to their surprise and never letting on they knew it had been a prank.

Until the day he died he kept his promise to never step foot in a mine, even in his 80's on a family visit to the Yorkshire coal mining museum. He also never forgot the morse code which for months kept those men supplied from the air, and up to the day he died could recite the alphabet as well as he could in 1942. I truly appreciate all you're doing to keep the memory of the Chindits alive so their sacrifices will never be forgotten. To those of us who owe our freedom to them, but now have only memories left, it means so much.

I would like to thank Amir and his family for all these invaluable anecdotes about Maurice and his time with the Chindits. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Hello, I am looking for any information you may have or be able to find in regards to my grandfather, Maurice Holmes. He was an RAF Radio Operator who served with the Chindits. He was present at least for the first operation and survived, but we are not sure if he was involved with the second. Many thanks.

I replied to Amir a few days later:

Dear Amir,

Thank you for your contact email via my website. I do have knowledge of a RAF Sergeant M. Holmes from one of the war diaries I have read. His RAF service number is given as 1039307 and he volunteered for the first Chindit operation, arriving at the training camp at Malthone in India on the 16th October 1942. According to an entry in the 142 Commando War diary, he was posted to Brigade Head Quarters, which was the command centre for the entire Chindit Brigade. This is sadly all I know about him, it is unclear which Column he served with inside Burma on Operation Longcloth, it may well be that he remained with Brigade HQ, in which case he was with Brigadier Wingate during the operation. I would be very interested to learn more about him and his life before and after WW2. If you possess a photograph of him that you would be willing to share, I would very much like to put this up on the website.

Over the coming days I received some more information from Amir, including one vital piece of information which confirmed in my mind, that Maurice had indeed served with Wingate's Brigade HQ on Operation Longcloth. This was mention of his best friend from his RAF days in India, RAF Sergeant Arthur Willshaw.

Amir continued:

Thanks so much for your quick reply Steve. That small bit of information from the War diary means the world to me. I never knew which column he was attached to, but if likely it was HQ I can now trace their movements from books and your website and learn more about his particular experiences. I've attached a photo of Maurice with his wife, Alma, who drove an ambulance in the ATS during the war. I'll have my mum write a bit about his pre/post war years as she will know more detail than me and I'll get that to you soon.

You may know more about his good friend, Arthur Willshaw, who was another RAF Signalman. My grandfather spoke of him fondly and often - as I understand it they made the trip out together after Wingate's order to disperse, but that may not be correct if Arthur (Arty) wasn't with HQ. They definitely spent a lot of time together in India during training. Unfortunately, much of my information comes from stories he told me as a child and teenager and my recollection isn't perfect, sadly he died of pancreatic cancer in 2007.

My grandfather grew up in the mining village of Moorends, near Doncaster. His father was a foreman in the local coal mine, but after developing black lung disease made his son swear to never set foot in a mine. Maurice volunteered for service in the RAF early in the war (as he told it, because he knew he'd get drafted and preferred their uniforms). He was selected for training as a Radio Operator and soon sailed to India where he was tasked with sending coded messages via morse code. In 1942 he was offered a pay raise and promotion from Corporal to Sergeant to participate in an upcoming mission - although details of the mission were not initially disclosed.

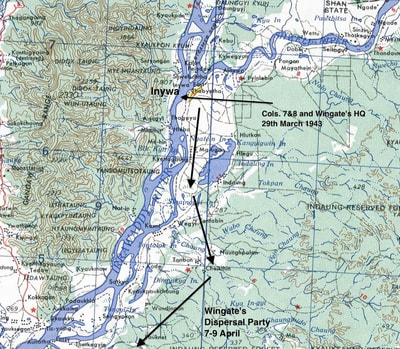

To his surprise he found himself at the Bush Warfare School with 142 Commando, who were preparing for Operation Longcloth. He had multiple interactions with Orde Wingate which he recalled fondly, although he pointed him out to be quite eccentric. It seems he may have been attached to Brigade HQ for some time. He took a photo of Wingate once, and gave him a copy, which he then found some 40 years later in a magazine. He survived crossing the Chindwin and Irrawaddy Rivers, and made it back to India, although he was suffering badly from malaria by that time.

Ultimately he made it home to England in February 1946 and married his pre-war sweetheart, Alma Teresa Bathurst, just two weeks later on the 23rd February. They ran a grocery story in Eyam village (the famous Plague Village) and raised a son, Malcolm, and a daughter, Julia. Maurice and Alma retired to Wakefield near Leeds where he lived the rest of his life. Although he frequently recounted his time in India and Burma he had clearly had his fill of adventure and never again left England. It wasn't until after his death in 2007 that I found his service book and learned that relatives could apply for medals owed. I am immensely proud of all he did and endured for his country, and his Burma Star will forever be one of our family's most treasured possessions, along with his kukri and bush hat.

Another story my mum just reminded me of and one of Grandad's favourites; was when he received an invitation to a garden party at the home of the Maharajah of Tikumgarh. Before Longcloth, he and a friend, possibly Arty Willshaw, were told about this party by others in the compound where they were based. They went together to the palace only to find it was a trick, and only officers had been invited. The sentry at the gate told them someone had been putting them on, but he decided to let them in anyway and they had a rare taste of luxury, enjoying the dancing, food and drinks. They returned to the base late in the evening and thanked the guys who had told them about the party, much to their surprise and never letting on they knew it had been a prank.

Until the day he died he kept his promise to never step foot in a mine, even in his 80's on a family visit to the Yorkshire coal mining museum. He also never forgot the morse code which for months kept those men supplied from the air, and up to the day he died could recite the alphabet as well as he could in 1942. I truly appreciate all you're doing to keep the memory of the Chindits alive so their sacrifices will never be forgotten. To those of us who owe our freedom to them, but now have only memories left, it means so much.

I would like to thank Amir and his family for all these invaluable anecdotes about Maurice and his time with the Chindits. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As has already been mentioned, Maurice Holmes' best friend from his time in India was RAF Sergeant Arthur Willshaw. After final dispersal was called, Willshaw was never far from Brigadier Wingate's side as the group headed back towards the Chindwin. In fact, he was one of the five Chindits who eventually swam the Chindwin River in the company of Wingate on the 28/29th April 1943. Contained within the pages of the book Wingate's Lost Brigade, written by Philip Chinnery, is a short account from RAF Wireless Operator Sgt. Arthur Willshaw, which describes the last few days march, before the men regained the west banks of the river:

After crossing the Mu River we faced the last sixty miles over almost impossible country to the Chindwin. It was here that we met an old Burmese Buddhist hermit, who appeared one evening just out of nowhere. He explained via the interpreters, that he had been sent to lead to safety a party of white strangers who were coming into his area. He was asked who had sent him and his only answer was that his God had warned him.

It was a risk we had to take, especially as we knew from information from friendly villagers that the Japs, now wise to our escape plan, were watching every road and track from the Mu to the Chindwin. Day after day he led us along animal trails and elephant tracks, sometimes wading for a day at a time through waist-high mountain streams. At one point on a very high peak we saw, way in the distance, a thin blue ribbon, it was the Chindwin. What added spirit this gave our flagging bodies and spent energies.

All our supplies were gone and we were really living on what we could find. A kind of lethargy was slowly taking its toll on us, we just couldn't care less one way or the other. The old hermit took us to within a few miles of the Chindwin and disappeared as strangely as he had appeared. It was then around the 23rd April.

A villager we stopped on the track told us that the Japanese were everywhere and that it would be impossible to get boats to cross the river as they had it so well guarded. Wingate selected five swimmers who would, with himself, attempt to get to the Chindwin, swim it and send back boats to an agreed rendezvous with the others. These swimmers were Brigadier Wingate, Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles, Captain Jefferies, Sergeant Carey of the Commandos, Private Boardman of the 13th King's, and myself.

At 0400 hours on the morning of 29th April 1943 the six of us set out for the river. Soon we struck a terrible stretch of elephant grass, seven or eight feet high and with an edge like a razor. We reconnoitred along it but could see no end to it, and no track through it, so the decision was made to push through it. Each man in turn dived headlong into it while the others pushed him flat; after a few minutes another took his place at the front. In four hours we had covered about 300 yards and were making such a noise that we feared the Japanese would be waiting when we broke out of the other side.

We pushed our way into a small clearing and collapsed; I couldn't have gone another foot and I know that we all had the same sickening thought. After all we had been through, how could we find the strength to go on? Then Wingate crawled to a gap in the grass and disappeared, only to reappear within minutes beckoning us to join him. We pushed our way another few feet and there it was, the Chindwin, right under our noses. Arms and legs streaming with blood, we decided to chance the Japs and swim for it right away. Among the many things I asked for on my pre-operational stocking-up visit to Karachi was a number of 'Mae West' lifejackets. I had carried mine throughout the whole of the expedition; I wore it as a waistcoat, used it as a pillow, used it to ford rivers and streams, and I still have it today. It was to save my life and that of Aung Thin that day.

Blowing it up, I explained that I would swim last and that if anybody got into difficulties they could hang on to me and we would drift downstream if necessary. How I feared that crossing, even though the Mae West was filthy and muddy from our time in Burma, it would soon wash clean in the water and what a bright orange coloured target it would make for the waiting Japs! And so into the water; ten yards made, twenty yards, fifty, one hundred, now almost just drifting, thoroughly exhausted. Aung Thin with a last despairing effort made it to my side and together we struggled the remaining fifty yards to the other bank. We dragged ourselves up the bank and into cover, I still relive those fifteen minutes waiting for the burst of machine-gun fire that thankfully didn't come.

To read the full story of Brigadier Wingate's journey back to India, please click on the following link: Wingate's Journey Home

Maurice Holmes sadly died back home in Wakefield on the 29th May 2007, he was 86 years old. I would like to thank Amir and his family once again for the information they have passed on to me and sincerely hope to learn more about RAF Sergeant Maurice Holmes in the near future.

Update 02/05/2019.

I was delighted recently to receive another contact email from Maurice Holmes' grandson, Amir Louka:

Steve,

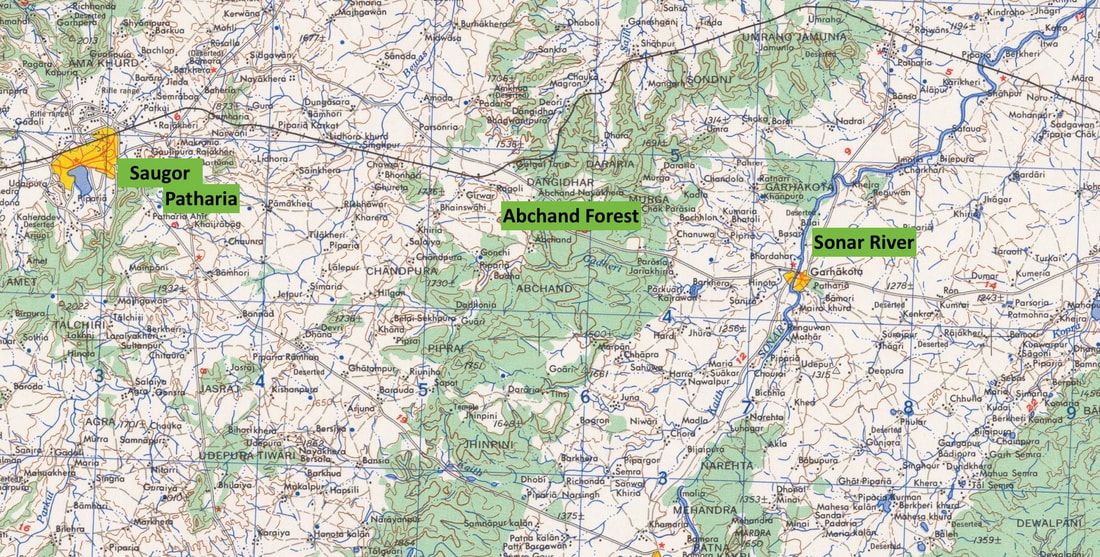

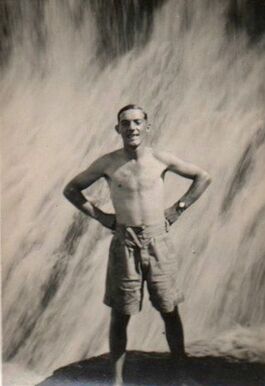

Please find attached to this email some photographs of my grandfather's time in India during the war. He sent these back to my grandmother along with many dozens of letters which unfortunately were not preserved. He always told us he had many more photos taken in Burma, but they were lost during a river crossing when the friend to whom he had lent the camera was swept away and drowned. Most of the ones we have left have a few describing words on the back as you will see. Some provide locations throughout India and corresponding dates. Feel free to add them to your archive on the website as you see fit.

Years ago my grandad was in hospital after an injury and he spotted a magazine with an article about the Chindits. Imagine his surprise when he opened it to see his own personal photograph of Wingate staring back at him! Apparently grandad asked if he could take a portrait and Wingate agreed on the condition that he could have a copy of the photo. The duplicate must have made its way home to his family because my grandads original photo never left the kitchen cupboard in over 50 years.

Seen below are just a few of the photographs mentioned by Amir, including the portrait of Brigadier Wingate at the Saugor training camp. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After crossing the Mu River we faced the last sixty miles over almost impossible country to the Chindwin. It was here that we met an old Burmese Buddhist hermit, who appeared one evening just out of nowhere. He explained via the interpreters, that he had been sent to lead to safety a party of white strangers who were coming into his area. He was asked who had sent him and his only answer was that his God had warned him.

It was a risk we had to take, especially as we knew from information from friendly villagers that the Japs, now wise to our escape plan, were watching every road and track from the Mu to the Chindwin. Day after day he led us along animal trails and elephant tracks, sometimes wading for a day at a time through waist-high mountain streams. At one point on a very high peak we saw, way in the distance, a thin blue ribbon, it was the Chindwin. What added spirit this gave our flagging bodies and spent energies.

All our supplies were gone and we were really living on what we could find. A kind of lethargy was slowly taking its toll on us, we just couldn't care less one way or the other. The old hermit took us to within a few miles of the Chindwin and disappeared as strangely as he had appeared. It was then around the 23rd April.

A villager we stopped on the track told us that the Japanese were everywhere and that it would be impossible to get boats to cross the river as they had it so well guarded. Wingate selected five swimmers who would, with himself, attempt to get to the Chindwin, swim it and send back boats to an agreed rendezvous with the others. These swimmers were Brigadier Wingate, Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles, Captain Jefferies, Sergeant Carey of the Commandos, Private Boardman of the 13th King's, and myself.

At 0400 hours on the morning of 29th April 1943 the six of us set out for the river. Soon we struck a terrible stretch of elephant grass, seven or eight feet high and with an edge like a razor. We reconnoitred along it but could see no end to it, and no track through it, so the decision was made to push through it. Each man in turn dived headlong into it while the others pushed him flat; after a few minutes another took his place at the front. In four hours we had covered about 300 yards and were making such a noise that we feared the Japanese would be waiting when we broke out of the other side.

We pushed our way into a small clearing and collapsed; I couldn't have gone another foot and I know that we all had the same sickening thought. After all we had been through, how could we find the strength to go on? Then Wingate crawled to a gap in the grass and disappeared, only to reappear within minutes beckoning us to join him. We pushed our way another few feet and there it was, the Chindwin, right under our noses. Arms and legs streaming with blood, we decided to chance the Japs and swim for it right away. Among the many things I asked for on my pre-operational stocking-up visit to Karachi was a number of 'Mae West' lifejackets. I had carried mine throughout the whole of the expedition; I wore it as a waistcoat, used it as a pillow, used it to ford rivers and streams, and I still have it today. It was to save my life and that of Aung Thin that day.

Blowing it up, I explained that I would swim last and that if anybody got into difficulties they could hang on to me and we would drift downstream if necessary. How I feared that crossing, even though the Mae West was filthy and muddy from our time in Burma, it would soon wash clean in the water and what a bright orange coloured target it would make for the waiting Japs! And so into the water; ten yards made, twenty yards, fifty, one hundred, now almost just drifting, thoroughly exhausted. Aung Thin with a last despairing effort made it to my side and together we struggled the remaining fifty yards to the other bank. We dragged ourselves up the bank and into cover, I still relive those fifteen minutes waiting for the burst of machine-gun fire that thankfully didn't come.

To read the full story of Brigadier Wingate's journey back to India, please click on the following link: Wingate's Journey Home

Maurice Holmes sadly died back home in Wakefield on the 29th May 2007, he was 86 years old. I would like to thank Amir and his family once again for the information they have passed on to me and sincerely hope to learn more about RAF Sergeant Maurice Holmes in the near future.

Update 02/05/2019.

I was delighted recently to receive another contact email from Maurice Holmes' grandson, Amir Louka:

Steve,

Please find attached to this email some photographs of my grandfather's time in India during the war. He sent these back to my grandmother along with many dozens of letters which unfortunately were not preserved. He always told us he had many more photos taken in Burma, but they were lost during a river crossing when the friend to whom he had lent the camera was swept away and drowned. Most of the ones we have left have a few describing words on the back as you will see. Some provide locations throughout India and corresponding dates. Feel free to add them to your archive on the website as you see fit.

Years ago my grandad was in hospital after an injury and he spotted a magazine with an article about the Chindits. Imagine his surprise when he opened it to see his own personal photograph of Wingate staring back at him! Apparently grandad asked if he could take a portrait and Wingate agreed on the condition that he could have a copy of the photo. The duplicate must have made its way home to his family because my grandads original photo never left the kitchen cupboard in over 50 years.

Seen below are just a few of the photographs mentioned by Amir, including the portrait of Brigadier Wingate at the Saugor training camp. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

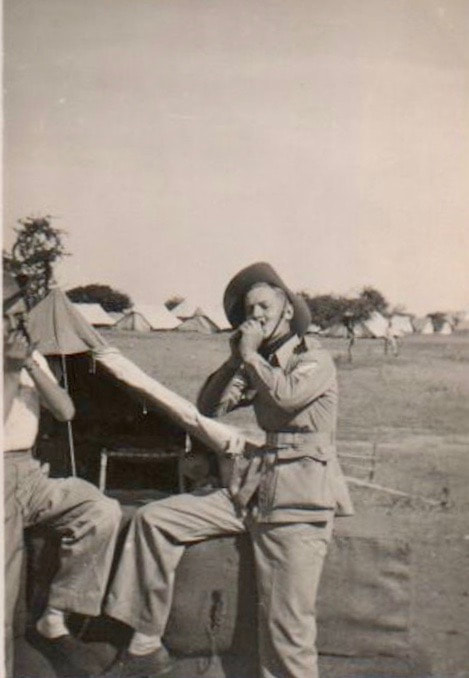

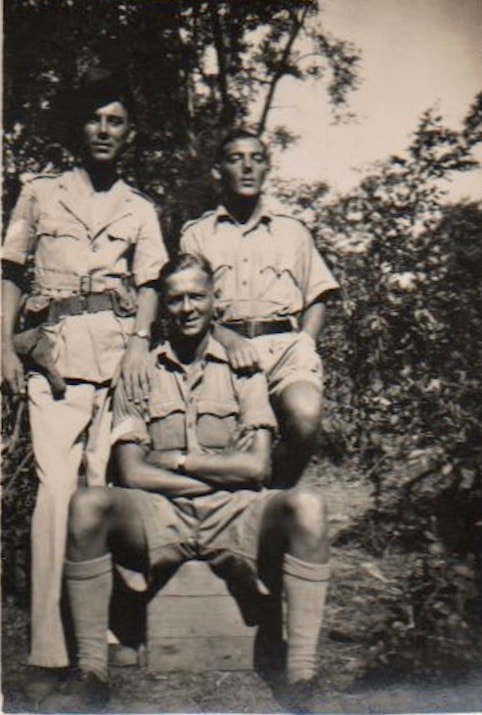

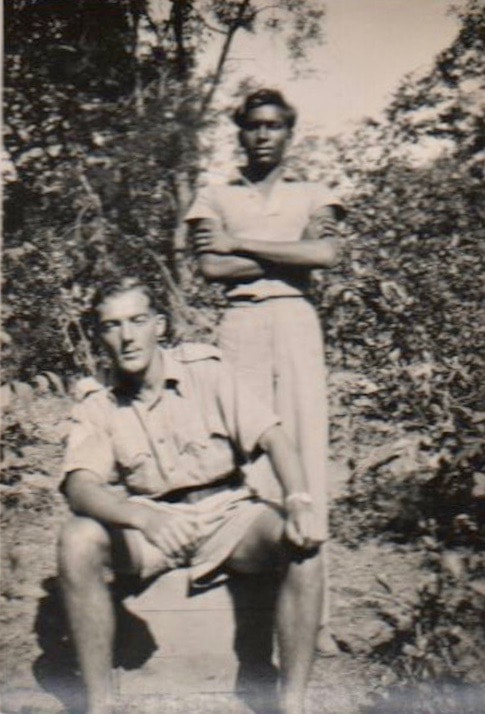

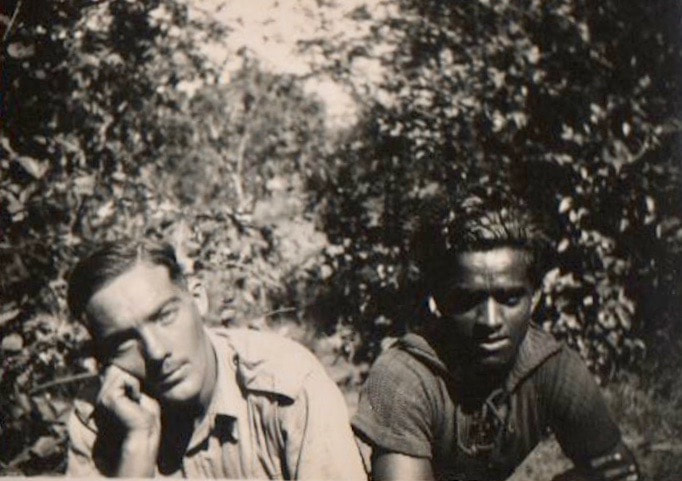

Arthur Willshaw during Chindit training in 1942.

Arthur Willshaw during Chindit training in 1942.

RAF Sergeant Arthur Willshaw

One of the most rewarding aspects of viewing the photograph collection of Sgt. Maurice Holmes, was finally and definitively seeing an image of Arthur Willshaw, one of Maurice's closest friends during the first Wingate expedition in 1943. It seems rather fitting to include Arthur's story here, alongside that of his great Chindit pal.

Arthur is mentioned in several books about the Chindits and as mentioned previously on these pages, was one of the men who swam the Chindwin River with Orde Wingate on the return journey to India after Operation Longcloth was closed. Probably the most detailed information in regards his time with the Chindits comes from the book, Wingate's Lost Brigade, by Philip Chinnery:

Two of the most important innovations to be tried out by Wingate's men were the use of long-range radio communications and the dropping of supplies to the men in the field by the Royal Air Force. Wingate took the unusual but very sensible decision to take Royal Air Force personnel with him to co-ordinate the air drops. Who better to talk to a pilot in the air than a pilot on the ground? In April 1942, a message was received at Headquarters 222 Group (RAF) in Colombo, Ceylon:

'Volunteers are required for a special mission — officers who have knowledge of Japanese aircraft and wireless operators who have a thorough knowledge of ground-to-air communication.'

Arthur Willshaw, a wireless operator by trade, received the message in code. An alleged friend in the Orderly Room told him the rumour was that a captured Japanese aircraft in India was wanted for examination back in the UK and a pilot was needed to fly it and a wireless operator to work signal stations on the route. 'This was just up my street,' Arthur recalled.

I had been a wireless operator in Singapore from 1939 until it fell and I had worked every wireless and signals station from Singapore to the UK during this time. I wanted to fly and above all I wanted to get home to take an eagerly awaited chance at Aircrew. After an interview with my Commanding Officer, a signal was received from Headquarters at New Delhi instructing me to report for an interview with the AOC-in-C. It was on Colombo railway station that I met up with my first two compatriots, a Flight Lieutenant Longmore and a Sergeant Davies, who knew no more than I did — except a rumour. Their rumour very nicely agreed with mine — little did we know!

During the journey from Ceylon, across India to Delhi, we got to know each other. Jack Longmore was an ex-rubber planter from Malaya, the first man, he told me, ever to loop a glider. Cliff Davies was an Australian, quiet, studious, wanting anything except a nice secure desk job. And so to Headquarters in New Delhi. Marble staircases, a very ornate office and a personal interview with Air Vice-Marshal D'Albiac. His questions rather puzzled me. What were my teeth like? Could I live on hard biscuits for a few weeks? And finally, the truth! A senior Army officer was going behind the Japanese lines in Burma. We had to try to get on to a Japanese airfield where we would take some photographs, probably even throw a few grenades, and then a quick return to India. He assured us that this would be all over in a matter of weeks. The clinching argument came: 'How long have you been overseas?' Two and a half years, sir.' H'm — well by the time you have done this job we should be able to see you home immediately afterwards.' Twelve months later, having walked some 1,500 miles over some of the most difficult country in the world, in the company of some of the world's finest soldiers, the Air Vice-Marshal kept his word!

In those twelve months I had enough adventures to last me a dozen lifetimes. We were ordered to report to a Long-Range Penetration Group, training in the Central Provinces at Jhansi in India. Our RAF element had now been joined by Flight Sergeant Alan Fidler and we arrived at Jhansi in best uniform — tailored gabardine — in the middle of the monsoon. Getting off our train we were told that the brigade we were to join was in camp at Malthone some ten miles away in the jungle. On asking for transport we were none too politely told there was none available and that orders were that all personnel joining the brigade were to walk it. Leaving our suitcases behind, walk we did, the first few miles along a reasonable road and then a plunge on to a jungle track which we followed to our destination. Most of the track was signposted with the odd Army notice board and for the last few miles it was completely under water. Wet, miserable, bedraggled we reached the Brigade Headquarters — just a few tents in a jungle clearing. All around, people seemed to be living in trees and the surrounding water was deep enough in places to swim in. Tired, weary and fed up with life in general, I found myself having to make a bed in the forks of a large tree and then, dreaming of wild animals, especially snakes, I dropped off to sleep.

And so began three months of hard and bitter experience. How I hated it — used to the comforts of barrack life, it became a fight for existence. We were paraded before daybreak, plunged into icy cold rivers, taught how to build bridges, how to cross lakes and fast-flowing rivers, how to shoot, how to handle explosives, how to be amateur Tarzans swinging on ropes from tree to tree, how to travel in the jungle and, above all, how to live off the jungle. The explosives tent was always open — take what you want and learn how to use it. Woe betide the careless! March, march, march ten, fifteen, twenty miles from camp along the only track in existence. We were then turned off the track into the jungle and told to find our way back to Headquarters. Added information was that the track we had come down was mined and anyone found on it was likely to be shot. It was — and they were! Soon we began to be exactly what Brigadier Wingate, our commander, required — an efficient jungle warfare force.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To read more about some of the above mentioned Chindits, please click on the following links:

Squadron Leader Longmore

RAF Sgt. Alan Fidler

One of the most rewarding aspects of viewing the photograph collection of Sgt. Maurice Holmes, was finally and definitively seeing an image of Arthur Willshaw, one of Maurice's closest friends during the first Wingate expedition in 1943. It seems rather fitting to include Arthur's story here, alongside that of his great Chindit pal.

Arthur is mentioned in several books about the Chindits and as mentioned previously on these pages, was one of the men who swam the Chindwin River with Orde Wingate on the return journey to India after Operation Longcloth was closed. Probably the most detailed information in regards his time with the Chindits comes from the book, Wingate's Lost Brigade, by Philip Chinnery:

Two of the most important innovations to be tried out by Wingate's men were the use of long-range radio communications and the dropping of supplies to the men in the field by the Royal Air Force. Wingate took the unusual but very sensible decision to take Royal Air Force personnel with him to co-ordinate the air drops. Who better to talk to a pilot in the air than a pilot on the ground? In April 1942, a message was received at Headquarters 222 Group (RAF) in Colombo, Ceylon:

'Volunteers are required for a special mission — officers who have knowledge of Japanese aircraft and wireless operators who have a thorough knowledge of ground-to-air communication.'

Arthur Willshaw, a wireless operator by trade, received the message in code. An alleged friend in the Orderly Room told him the rumour was that a captured Japanese aircraft in India was wanted for examination back in the UK and a pilot was needed to fly it and a wireless operator to work signal stations on the route. 'This was just up my street,' Arthur recalled.

I had been a wireless operator in Singapore from 1939 until it fell and I had worked every wireless and signals station from Singapore to the UK during this time. I wanted to fly and above all I wanted to get home to take an eagerly awaited chance at Aircrew. After an interview with my Commanding Officer, a signal was received from Headquarters at New Delhi instructing me to report for an interview with the AOC-in-C. It was on Colombo railway station that I met up with my first two compatriots, a Flight Lieutenant Longmore and a Sergeant Davies, who knew no more than I did — except a rumour. Their rumour very nicely agreed with mine — little did we know!

During the journey from Ceylon, across India to Delhi, we got to know each other. Jack Longmore was an ex-rubber planter from Malaya, the first man, he told me, ever to loop a glider. Cliff Davies was an Australian, quiet, studious, wanting anything except a nice secure desk job. And so to Headquarters in New Delhi. Marble staircases, a very ornate office and a personal interview with Air Vice-Marshal D'Albiac. His questions rather puzzled me. What were my teeth like? Could I live on hard biscuits for a few weeks? And finally, the truth! A senior Army officer was going behind the Japanese lines in Burma. We had to try to get on to a Japanese airfield where we would take some photographs, probably even throw a few grenades, and then a quick return to India. He assured us that this would be all over in a matter of weeks. The clinching argument came: 'How long have you been overseas?' Two and a half years, sir.' H'm — well by the time you have done this job we should be able to see you home immediately afterwards.' Twelve months later, having walked some 1,500 miles over some of the most difficult country in the world, in the company of some of the world's finest soldiers, the Air Vice-Marshal kept his word!

In those twelve months I had enough adventures to last me a dozen lifetimes. We were ordered to report to a Long-Range Penetration Group, training in the Central Provinces at Jhansi in India. Our RAF element had now been joined by Flight Sergeant Alan Fidler and we arrived at Jhansi in best uniform — tailored gabardine — in the middle of the monsoon. Getting off our train we were told that the brigade we were to join was in camp at Malthone some ten miles away in the jungle. On asking for transport we were none too politely told there was none available and that orders were that all personnel joining the brigade were to walk it. Leaving our suitcases behind, walk we did, the first few miles along a reasonable road and then a plunge on to a jungle track which we followed to our destination. Most of the track was signposted with the odd Army notice board and for the last few miles it was completely under water. Wet, miserable, bedraggled we reached the Brigade Headquarters — just a few tents in a jungle clearing. All around, people seemed to be living in trees and the surrounding water was deep enough in places to swim in. Tired, weary and fed up with life in general, I found myself having to make a bed in the forks of a large tree and then, dreaming of wild animals, especially snakes, I dropped off to sleep.

And so began three months of hard and bitter experience. How I hated it — used to the comforts of barrack life, it became a fight for existence. We were paraded before daybreak, plunged into icy cold rivers, taught how to build bridges, how to cross lakes and fast-flowing rivers, how to shoot, how to handle explosives, how to be amateur Tarzans swinging on ropes from tree to tree, how to travel in the jungle and, above all, how to live off the jungle. The explosives tent was always open — take what you want and learn how to use it. Woe betide the careless! March, march, march ten, fifteen, twenty miles from camp along the only track in existence. We were then turned off the track into the jungle and told to find our way back to Headquarters. Added information was that the track we had come down was mined and anyone found on it was likely to be shot. It was — and they were! Soon we began to be exactly what Brigadier Wingate, our commander, required — an efficient jungle warfare force.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To read more about some of the above mentioned Chindits, please click on the following links:

Squadron Leader Longmore

RAF Sgt. Alan Fidler

Arthur Willshaw continues:

We lived off the jungle, no food except biscuits — if we wanted food we foraged for it. We ate snakes, frogs, lizards, fish, roots, leaves, in fact we tried everything at least once! Pigeons were a great favourite, but there isn't much left of a pigeon that's been shot with a .303 from short range. Six pigeons just about made a meal. Stuffed with broken biscuit and served with young bamboo shoots — I can still taste them. But, of course, as we foraged, game became scarcer. Peacocks, which were plentiful to start with (they taste very much like sweet turkey), soon left the area and most of the other bigger game too. This meant foraging further and further afield into the jungle in order to get food, in order to live.

We learned by experience which leaves, when dried, made tobacco substitute and which leaves to use for other vital necessities. One of my most painful recollections was the time when, somewhat in a hurry, I picked the largest leaf handy, only to find, too late, that it was covered with small hairs that, when crushed, caused a nasty itchy rash. I never made that mistake again! And so after three months of this type of living we had toughened up considerably. Flabby flesh had disappeared, chests had filled out, muscles developed where only outlines had existed before and we began to glory in a new feeling of self-reliance that was to be so important in the coming task.

I found myself allocated to the Headquarters column together with Flight Sergeant Alan Fidler and Squadron Leader (now promoted) Longmore. Our main job was to co-ordinate the requirements of all columns, the RAF element of each being an RAF officer and two NCOs. These teams would recce for a suitable area for an air supply drop, co-ordinate the requirements of all columns and pass the information to the Brigade Head Quarters via the RAF wireless set. They would then go out, light flare paths in a line with the dropping zone and supervise the drop from the ground. My job on HQ column was to keep wireless contact with all the columns and also with RAF HQ at New Delhi who planned and put into execution the requirement for the air supply drops. We were to carry our wireless equipment on mules and learning how to look after and cope with these obstinate animals became part of our daily life. Together with these mules we marched many, many miles on exercises in the central provinces of India.

Our wireless equipment was the best then available, but still formed quite a cumbersome load which was carried in two leather panniers — one on each side of a mule's back. Ensuring that we had the best equipment caused quite a stir. I was instructed to proceed to Karachi to the Maintenance Unit at Drigh Road and to take what we needed from the shelves of the depot, then to bring the whole lot of equipment back by rail to Jhansi. I was assured that everything had been arranged and that I would be expected. I travelled by train from Jhansi to Gwalior, thence by BOAC Sunderland flying boat across India to Karachi. I was anything but expected, but put yourselves in their shoes; here was an NCO, with only an identification card, saying that he was authorised to take what he pleased of your scarce and important stocks.

In next to no time I found myself in custody in the guardroom, and it was only when a disbelieving officer placed a telephone call directly to Air Headquarters, New Delhi and spoke to Air Vice-Marshal D'Albiac — who, on being given a situation report, requested the call be transferred to the Commanding Officer of the depot — did things start to happen my way. I found myself walking around the radio spares section saying, 'Ten of those, twelve of these, all of those', while a very worried equipment officer was wondering how on earth he was to get replacements. All the items were packed on the spot and, together with a Corporal Stonelake, two truckloads of equipment were escorted across India by rail back to Jhansi. I will always remember the look on Corporal Stonelake's face, whom I am certain had been specially chosen to ensure that the precious equipment reached a service destination, when he saw our jungle home, and I know that an audible sigh of relief passed his lips when he escaped back to a normal RAF existence.

We lived off the jungle, no food except biscuits — if we wanted food we foraged for it. We ate snakes, frogs, lizards, fish, roots, leaves, in fact we tried everything at least once! Pigeons were a great favourite, but there isn't much left of a pigeon that's been shot with a .303 from short range. Six pigeons just about made a meal. Stuffed with broken biscuit and served with young bamboo shoots — I can still taste them. But, of course, as we foraged, game became scarcer. Peacocks, which were plentiful to start with (they taste very much like sweet turkey), soon left the area and most of the other bigger game too. This meant foraging further and further afield into the jungle in order to get food, in order to live.

We learned by experience which leaves, when dried, made tobacco substitute and which leaves to use for other vital necessities. One of my most painful recollections was the time when, somewhat in a hurry, I picked the largest leaf handy, only to find, too late, that it was covered with small hairs that, when crushed, caused a nasty itchy rash. I never made that mistake again! And so after three months of this type of living we had toughened up considerably. Flabby flesh had disappeared, chests had filled out, muscles developed where only outlines had existed before and we began to glory in a new feeling of self-reliance that was to be so important in the coming task.

I found myself allocated to the Headquarters column together with Flight Sergeant Alan Fidler and Squadron Leader (now promoted) Longmore. Our main job was to co-ordinate the requirements of all columns, the RAF element of each being an RAF officer and two NCOs. These teams would recce for a suitable area for an air supply drop, co-ordinate the requirements of all columns and pass the information to the Brigade Head Quarters via the RAF wireless set. They would then go out, light flare paths in a line with the dropping zone and supervise the drop from the ground. My job on HQ column was to keep wireless contact with all the columns and also with RAF HQ at New Delhi who planned and put into execution the requirement for the air supply drops. We were to carry our wireless equipment on mules and learning how to look after and cope with these obstinate animals became part of our daily life. Together with these mules we marched many, many miles on exercises in the central provinces of India.

Our wireless equipment was the best then available, but still formed quite a cumbersome load which was carried in two leather panniers — one on each side of a mule's back. Ensuring that we had the best equipment caused quite a stir. I was instructed to proceed to Karachi to the Maintenance Unit at Drigh Road and to take what we needed from the shelves of the depot, then to bring the whole lot of equipment back by rail to Jhansi. I was assured that everything had been arranged and that I would be expected. I travelled by train from Jhansi to Gwalior, thence by BOAC Sunderland flying boat across India to Karachi. I was anything but expected, but put yourselves in their shoes; here was an NCO, with only an identification card, saying that he was authorised to take what he pleased of your scarce and important stocks.

In next to no time I found myself in custody in the guardroom, and it was only when a disbelieving officer placed a telephone call directly to Air Headquarters, New Delhi and spoke to Air Vice-Marshal D'Albiac — who, on being given a situation report, requested the call be transferred to the Commanding Officer of the depot — did things start to happen my way. I found myself walking around the radio spares section saying, 'Ten of those, twelve of these, all of those', while a very worried equipment officer was wondering how on earth he was to get replacements. All the items were packed on the spot and, together with a Corporal Stonelake, two truckloads of equipment were escorted across India by rail back to Jhansi. I will always remember the look on Corporal Stonelake's face, whom I am certain had been specially chosen to ensure that the precious equipment reached a service destination, when he saw our jungle home, and I know that an audible sigh of relief passed his lips when he escaped back to a normal RAF existence.

Arthur Willshaw's story concludes:

Another three months followed, getting prepared, getting fitter, experimenting, breaking down the myth that the Japanese were the world's finest jungle fighters. It was drummed into our heads that the jungle was like the sea — boundless — in which men could move around for weeks, even months on end, within rifle shot of the enemy but without ever encountering him. We were taught to regard the jungle as our environment, and as a friend. Halfway through our training the sickness rate became very high and Wingate had to put his foot down.

'Everyone is to be taught to be doctor minded,' he said. 'Although it is all right in normal civilian life, where ample medical facilities are available, it will not apply to us in the jungle. You have to diagnose your own complaints and then cure yourselves. When we go into action and you are sick, it will be just too bad. We shall not stop for you, for our very lives may be jeopardised by waiting for stragglers. If you are sick you are of no use to us — you become an unwanted liability, we shall leave you to affect your own salvation.' Attending sick parades without good cause became a punishable offence and doctors only gave treatment to the seriously injured and really ill.

We were all given our own small dispensary — quinine and atebrin for malaria, sulfaguanadin for dysentery, and other sulphur drugs for infectious wounds. We learned lessons that were to prove invaluable during our months behind the Japanese lines. Individual training progressed to platoon training, platoon to column, column to group, and group would exercise against group. Problems arose on all sides, signals, ciphers, transport, demolitions, all having to be solved and solved quickly. Exercises got stiffer, those that were considered unfit were weeded out. Soldiers were made NCOs and NCOs were made soldiers and had to prove themselves worthy of the leadership that would be required of them before either being ousted or re-admitted to the fold.

And so in January 1943 we moved as a Brigade by rail from Jhansi to Dimapur, which was a railhead at the head of the road which leads via Imphal and Tamu to the Chindwin and Burma. It was here that we first heard of our new name - The Chindits - even now after all these years I still have a great sense of pride in knowing that I was one of them and even more so, in the fact that I was one of the very few RAF Chindits.

Another three months followed, getting prepared, getting fitter, experimenting, breaking down the myth that the Japanese were the world's finest jungle fighters. It was drummed into our heads that the jungle was like the sea — boundless — in which men could move around for weeks, even months on end, within rifle shot of the enemy but without ever encountering him. We were taught to regard the jungle as our environment, and as a friend. Halfway through our training the sickness rate became very high and Wingate had to put his foot down.

'Everyone is to be taught to be doctor minded,' he said. 'Although it is all right in normal civilian life, where ample medical facilities are available, it will not apply to us in the jungle. You have to diagnose your own complaints and then cure yourselves. When we go into action and you are sick, it will be just too bad. We shall not stop for you, for our very lives may be jeopardised by waiting for stragglers. If you are sick you are of no use to us — you become an unwanted liability, we shall leave you to affect your own salvation.' Attending sick parades without good cause became a punishable offence and doctors only gave treatment to the seriously injured and really ill.

We were all given our own small dispensary — quinine and atebrin for malaria, sulfaguanadin for dysentery, and other sulphur drugs for infectious wounds. We learned lessons that were to prove invaluable during our months behind the Japanese lines. Individual training progressed to platoon training, platoon to column, column to group, and group would exercise against group. Problems arose on all sides, signals, ciphers, transport, demolitions, all having to be solved and solved quickly. Exercises got stiffer, those that were considered unfit were weeded out. Soldiers were made NCOs and NCOs were made soldiers and had to prove themselves worthy of the leadership that would be required of them before either being ousted or re-admitted to the fold.

And so in January 1943 we moved as a Brigade by rail from Jhansi to Dimapur, which was a railhead at the head of the road which leads via Imphal and Tamu to the Chindwin and Burma. It was here that we first heard of our new name - The Chindits - even now after all these years I still have a great sense of pride in knowing that I was one of them and even more so, in the fact that I was one of the very few RAF Chindits.

Arthur Willshaw is also mentioned in the book, Fire in the Night, a biography of Orde Wingate written by John Bierman and Colin Smith, which coincidentally features the same photograph of Wingate taken by Maurice Holmes at Saugor in 1942, on the front cover. Arthur is also mentioned in Wilfred Burchett's book, Wingate's Adventure.

On the Imperial War Museum website, there are three mentions of Sgt. Willshaw from within the museum online catalogue:

1. A photograph of a Chindit Wireless operator taken during Operation Longcloth, believed to be Sgt. Arthur Willshaw:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194376

2. A short film showing the men of Operation Longcloth, but sadly no longer viewable on line:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1060034985

3. Perhaps most interesting of all, a photographic image of the Mae West life preserver used by Willshaw during the re-crossing of the Chindwin. Sadly, this is also not viewable online:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30151088

In his own memoir, Arthur Willshaw talks about some of the food the Chindits prepared for themselves during the expedition in Burma and in particular the recipe for, Bamboo Baked Rice:

Take a 12" length of bamboo cane about 1" in circumference, fill it to within 2" of the top with rice. Add 1" of water and plug the open end with clay or leaves. Place onto a burning fire and let the outer bamboo skin burn away. Take the cane out of the fire, allow to cool and then peel off the burnt bamboo. This makes a stick of rice already cooked which you can break off like a stick of rock and eat one piece at a time. Such a stick of rice will last for weeks before going sour.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to Arthur Willshaw and his Chindit adventure. I would like to thank Amir Louka once more, for giving me permission to reproduce some of his grandfather's photographs on these website pages. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rather fittingly, I will leave the final word to Arthur himself:

I went into Burma just over nine stones in weight and came out a mere five and a half stones. After a month in hospital the adventure was over for me. Air Marshal D'Albiac did keep his word and after flying to Delhi and then on to Bombay, I boarded the next boat to the United Kingdom via the Cape and was home by August.

On the Imperial War Museum website, there are three mentions of Sgt. Willshaw from within the museum online catalogue:

1. A photograph of a Chindit Wireless operator taken during Operation Longcloth, believed to be Sgt. Arthur Willshaw:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194376

2. A short film showing the men of Operation Longcloth, but sadly no longer viewable on line:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1060034985

3. Perhaps most interesting of all, a photographic image of the Mae West life preserver used by Willshaw during the re-crossing of the Chindwin. Sadly, this is also not viewable online:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30151088

In his own memoir, Arthur Willshaw talks about some of the food the Chindits prepared for themselves during the expedition in Burma and in particular the recipe for, Bamboo Baked Rice:

Take a 12" length of bamboo cane about 1" in circumference, fill it to within 2" of the top with rice. Add 1" of water and plug the open end with clay or leaves. Place onto a burning fire and let the outer bamboo skin burn away. Take the cane out of the fire, allow to cool and then peel off the burnt bamboo. This makes a stick of rice already cooked which you can break off like a stick of rock and eat one piece at a time. Such a stick of rice will last for weeks before going sour.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to Arthur Willshaw and his Chindit adventure. I would like to thank Amir Louka once more, for giving me permission to reproduce some of his grandfather's photographs on these website pages. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rather fittingly, I will leave the final word to Arthur himself:

I went into Burma just over nine stones in weight and came out a mere five and a half stones. After a month in hospital the adventure was over for me. Air Marshal D'Albiac did keep his word and after flying to Delhi and then on to Bombay, I boarded the next boat to the United Kingdom via the Cape and was home by August.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2017.