Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore

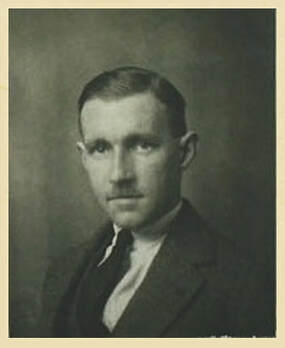

Cecil Longmore in 1931.

Cecil Longmore in 1931.

Jack Longmore was a Squadron-Leader from RAF Bomber command and was captured at the Irrawaddy in 1943 whilst on special duty with 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. He had over 500 parachute jumps to his credit and was with the Cobham Circus in the 1930's. He was an ex-rubber planter on a short-term RAF commission and aged 35 when captured. He was a humorist, though quiet and a steadying influence.

This is a quote from the book, Roll On, by fellow Chindit, Tommy Roberts. Both men had been captured by the Japanese in late April 1943 and both were chosen to be transferred from Burma for further interrogation by the Japanese secret police, the Kempai-tai at Changi POW camp in Singapore.

Cecil John Longmore was born in Bombay on the 17th November 1908 and spent the earliest years of his life in India before moving to Hampshire, where his father became a Market Gardener in the Fareham suburb of Lock's Heath. In the 1930's he had been a member of Cobham's Flying Circus, before taking up the role of rubber planter with the Kuala Lumpur Rubber Company (Malaya) in 1936. In January 1931, Cecil, known to his family and friends as Jack, acquired his flying certificate and membership of the British Aero Club, after a test flight in a DH60 Cirrus Moth aeroplane at the Hampshire Aero Club.

In the autumn of 1942, Squadron Leader Longmore volunteered for a secret assignment, advertised on the notice-board at his RAF airfield barracks. This resulted in him joining Wingate's 77th Brigade at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India, where he became the senior officer for the RAF Liaison Section of the Brigade. During this time, and amongst other things, he developed the fire-lighting techniques which were to become vital in bringing in the supply drop Dakotas successfully during operations inside Burma. On the 19th January 1943, a number of night time supply drop exercises were carried out on the Manipur Road in preparation for the forthcoming expedition. This in effect was a final dress-rehearsal before the Brigade crossed the Chindwin and into Burma.

Seen below is a transcription of a report on the success of the above mentioned exercises, as written by India GHQ at Delhi:

Many were dubious as to the ability of pilots to find their way by night, but experiences proved that the pilot preferred dropping by night, compared with by day and if anything found it easier to find his target and preferred the freedom from potential enemy fighter interference. The experimental drops were a success, and tribute should be paid to Squadron Leader Longmore (Commander of the RAF Detachment) and Flight Lieutenant Edmonds who was attached to No. 1 Group. All ranks in the Brigade were greatly heartened by this convincing demonstration of the ability of the RAF to deliver the goods (quite literally).

This is a quote from the book, Roll On, by fellow Chindit, Tommy Roberts. Both men had been captured by the Japanese in late April 1943 and both were chosen to be transferred from Burma for further interrogation by the Japanese secret police, the Kempai-tai at Changi POW camp in Singapore.

Cecil John Longmore was born in Bombay on the 17th November 1908 and spent the earliest years of his life in India before moving to Hampshire, where his father became a Market Gardener in the Fareham suburb of Lock's Heath. In the 1930's he had been a member of Cobham's Flying Circus, before taking up the role of rubber planter with the Kuala Lumpur Rubber Company (Malaya) in 1936. In January 1931, Cecil, known to his family and friends as Jack, acquired his flying certificate and membership of the British Aero Club, after a test flight in a DH60 Cirrus Moth aeroplane at the Hampshire Aero Club.

In the autumn of 1942, Squadron Leader Longmore volunteered for a secret assignment, advertised on the notice-board at his RAF airfield barracks. This resulted in him joining Wingate's 77th Brigade at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India, where he became the senior officer for the RAF Liaison Section of the Brigade. During this time, and amongst other things, he developed the fire-lighting techniques which were to become vital in bringing in the supply drop Dakotas successfully during operations inside Burma. On the 19th January 1943, a number of night time supply drop exercises were carried out on the Manipur Road in preparation for the forthcoming expedition. This in effect was a final dress-rehearsal before the Brigade crossed the Chindwin and into Burma.

Seen below is a transcription of a report on the success of the above mentioned exercises, as written by India GHQ at Delhi:

Many were dubious as to the ability of pilots to find their way by night, but experiences proved that the pilot preferred dropping by night, compared with by day and if anything found it easier to find his target and preferred the freedom from potential enemy fighter interference. The experimental drops were a success, and tribute should be paid to Squadron Leader Longmore (Commander of the RAF Detachment) and Flight Lieutenant Edmonds who was attached to No. 1 Group. All ranks in the Brigade were greatly heartened by this convincing demonstration of the ability of the RAF to deliver the goods (quite literally).

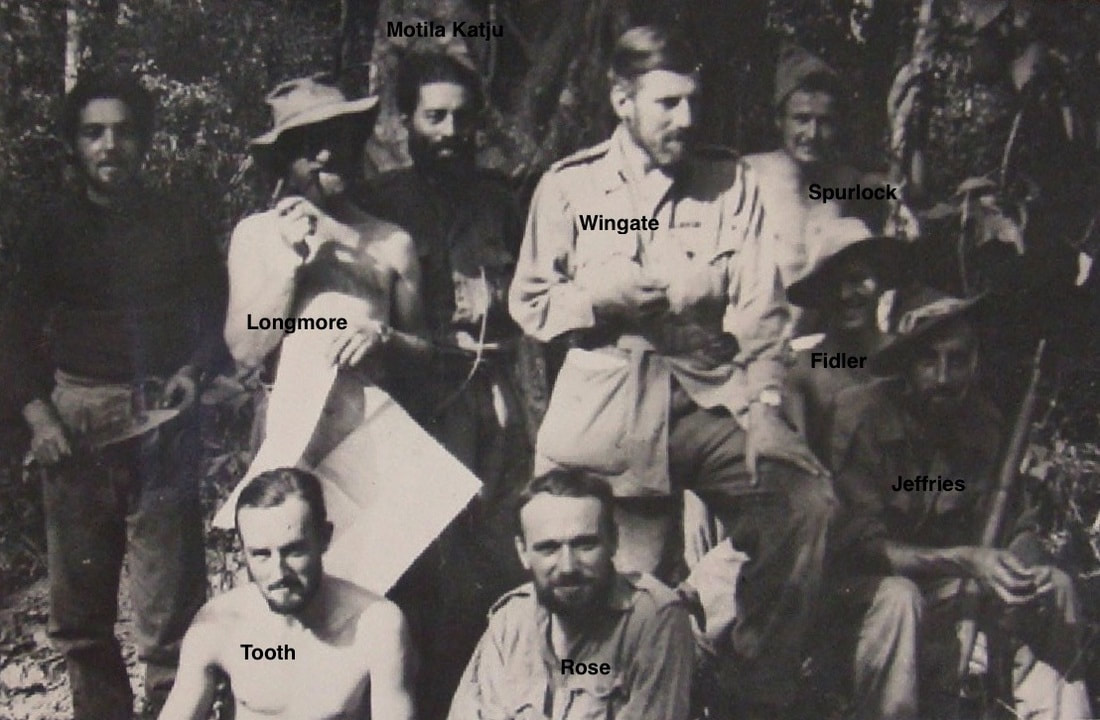

Wingate and his Brigade HQ moved through the jungles of Burma during the first few weeks of Operation Longcloth, orchestrating the Chindit columns of Northern Group as they carried out their various pre-arranged assignments and demolitions. For the most part things went well and the Brigade suffered only minor casualties. Squadron Leader Longmore, alongside his second in command, Flight Lieutenant Albert Tooth successfully delivered their side of the bargain and brought in the planes of 31 Squadron to feed and re-equip the marching Chindit columns.

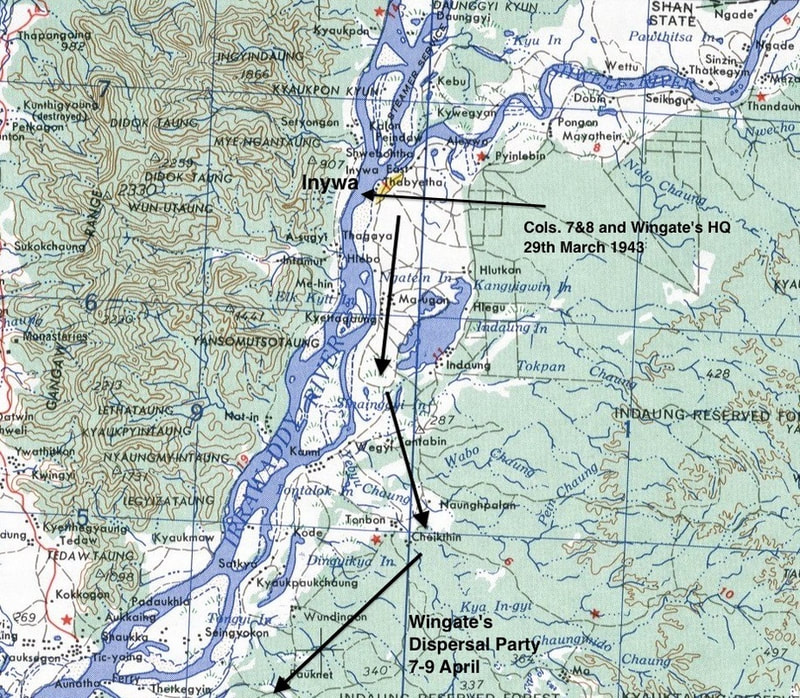

By late March 1943, Wingate and his Brigade were planning their exit from Burma after six weeks of raiding behind enemy lines. On the 29th March, three Chindit units (Columns 7 and 8, plus Brigade HQ) had massed on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River near the town of Inywa. The idea was to get across this wide expanse of water as quickly as possible and then, once over, move off westwards and return to India. Wingate had previously crossed the Irrawaddy at Inywa on the outward journey and thought the Japanese would not expect him to retrace his steps.

Unfortunately, the crossing was contested by a large patrol of Japanese soldiers positioned on the opposite bank of the river. The Chindits in the leading boats soon came under severe machine gun and mortar fire, resulting in many casualties. Wingate, after a speedy consultation with his column commanders, decided to call off the crossing and the dispirited columns melted away into the jungle. Columns 7 and 8 soon moved away from the Irrawaddy, both heading roughly south-east. Wingate took his men deep in to the surrounding scrub-jungle close to Inywa, where they would wait patiently for several days until the heat had died down and the enemy had left the area.

During their time hiding out in the jungle, Wingate gave orders for the remaining mules to be killed and that the men should eat the mule flesh to bolster their depleted rations. He also split his Head Quarters up at this time into smaller dispersal groups of around 25-35 men per party. On 7th April, Wingate and his dispersal party (some 43 men) made a second attempt at crossing the Irrawaddy, this time 25 miles south of Inywa. For two days they searched the riverbank for boats, but Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles could only find one boat and this would take only seven people at a time. They began crossing late that afternoon, but when half of the party were over, automatic fire was heard from the north and the native boatman made off with his craft, leaving the rest of the men stranded on the east bank.

Those who successfully made it across the river included Wingate, Majors Anderson and Jefferies, Captains Aung Thin and Motilal Katju, and twenty-four Other Ranks. They were not, however, on the west bank of the river. They were in fact, on an island in the middle of the Irrawaddy and so they immediately moved on towards the only village (Nyaungbintha), where they found another large boat and made the final crossing at dusk. Once over, they moved on for a couple of miles and then lay up for the night. The mosquitoes in this area were intolerable and they got very little sleep.

To read more about Brigadier Wingate's dispersal in 1943, please click on the following link: Wingate's Journey Home

Jack Longmore was in the last party waiting to cross the river, together with Flight Lieutenant Tooth, Flight Sergeant Fidler, Lieutenant Rose of the Gurkha Rifles, Private Dermody and Private Weston of the King's and Signaller Eric Hutchins.

Eric Hutchins recalled:

The first six boat parties made their way safely to the opposite bank. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the opposite bank we could find no trace of the others. Wingate's excuse when we met him later, was he 'thought' we had been captured by the Japanese, whereas he had abandoned us without maps or any means of finding our way back to our own lines.

So we set out west only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Our problems now really began, because we could not find a suitable boat. Eventually we found a boat that had seen better days and decided to take a chance crossing at night, using our rifles as oars. Of course the inevitable happened and the boat capsized. I and others swam to the west shore, where we had to rescue two of our party who were clutching on to a floating plant because they could not swim. At light of day we found that Squadron Leader Longmore was missing. Later at the end of the war I found out that he had remained clutching the boat and floated down river and was eventually captured.

To read more about Eric Hutchins and the rest of his group at the Irrawaddy, please click on the following link: Signalman Eric Hutchins

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this part of the story, including a map of the area around Inywa on the Irrawaddy. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

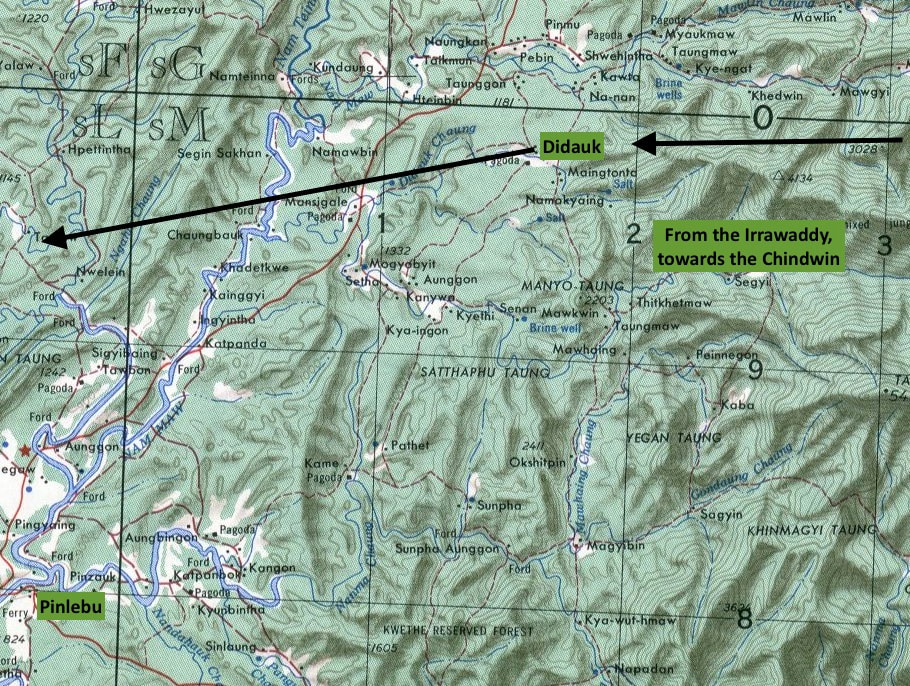

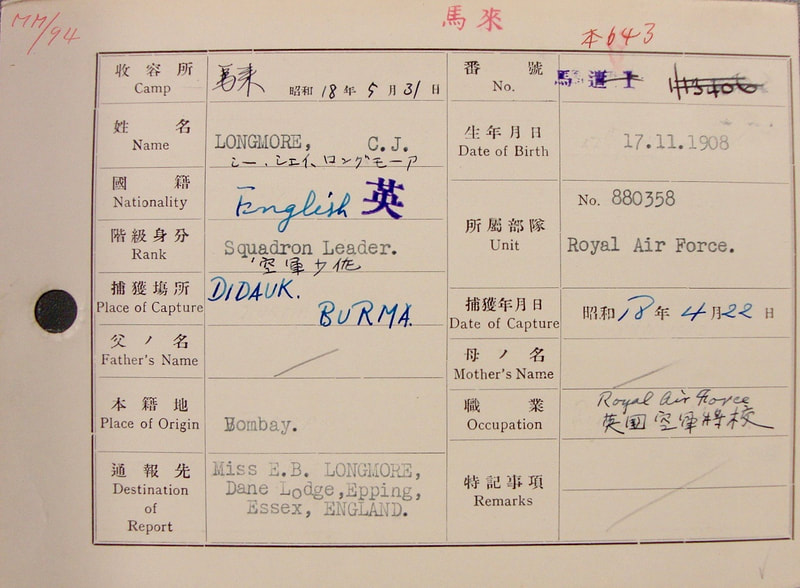

As already mentioned by Signalman Eric Hutchins, there was a strongly held belief that Jack Longmore had drowned at the Irrawaddy on the 9/10th April. In fact, his death was recorded in the pages of Wingate's Adventure, written by war correspondent Wilfred Burchett shortly after Operation Longcloth was officially closed. Thankfully, this was not the case and from other reports from that time it is now known that he had attempted to rescue some Gurkha soldiers in the river who could not swim and had been washed away downstream in doing so. On his POW index card it states that Jack was captured on the 22nd April 1943 near the Burmese village of Didauk on the Pinlebu Road.

In order to have reached this village during his final days of freedom, Jack must have been washed up on the west banks of the Irrawaddy some miles to the north of where the Brigade had crossed and then proceeded to march directly for India. It is not known whether he was alone at this point, or whether he was in the company of the Gurkha soldiers he had tried to rescue. Didauk is approximately 45 miles from the Irrawaddy across unforgiving and undulating country and is the same number of miles from the sanctuary of the Chindwin River and what was back then Allied held territory. He was effectively half-way home when he was captured by the Japanese.

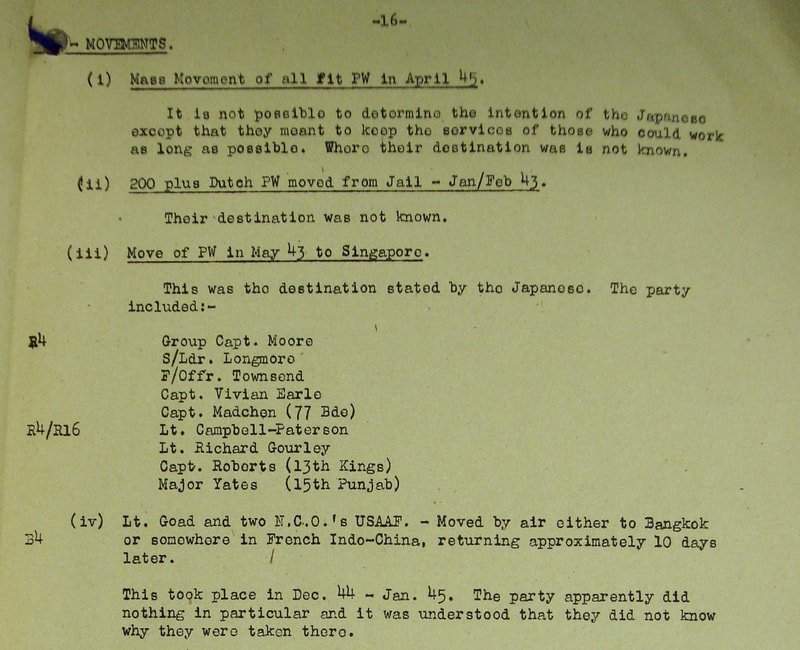

We know that Squadron Leader Longmore was taken initially to Rangoon Central Jail, where he met up with many of his former Chindit comrades from Operation Longcloth. Then in May, he was taken by air, along with other officers held at Rangoon to the Changi POW Camp in Singapore, to be interrogated by the Japanese secret police, the Kempai-tai. It must be presumed that the Japanese were interested in what Jack and the other officers may have known about the aims and objectives of Wingate's first raid into Burma. In any case, for the next two years, Jack and his comrades were held as prisoners of war in various camps in the local Changi area.

From Captain Tommy Roberts' book, Roll On (Volume One):

On the 30th May, I was moved by air via Bangkok to the island of Singapore. In my party were: Captain Machin, Captain B. Yates, Lieutenants K. Gourlie and Campbell-Paterson and Squadron Leader W. Matheson. We were housed in the old Changi Maternity Hospital. Already there, having been flown from Rangoon the previous week, were: Group Captain G.C. More, Squadron Leader Longmore, Pilot Officer J. Townsend RAF, Captain Vivian Earle and Pilot Officers Jensen and Baggett of the United States Army Air Force.

We were responsible for our own cooking which we managed rather well, with three men having a two-day stint of cooking duty on rotation. Food was decent, but barely sufficient and the Red Cross supplied us with soap and toothpaste and some tins of Malayan foods. With the small amount of money, mostly in the hands of the Americans, we were able to purchase locally some biscuits, bread, tobacco and nut toffee. In general, we were interrogated infrequently, with these sessions attended by Japanese interpreters which we named the Terrifiers. We have been told that soon we will be transferred to a real POW Camp up country, but nothing seems to happen. The RAF and USAAF chaps spend most of their time playing cards. Townsend is learning Nippongo (Japanese), I'm pecking at it too although I find concentrating very difficult.

Jack Longmore's POW number inside Changi was 643, and he had to recite this number in Japanese (roku-shi-san) at the morning and evening roll calls or tenkos, as they were called at the camp. Compared to conditions in Rangoon Jail, where food was scarce and of low quality and where men were expected to sleep forty to a cell-room, Jack, Tommy and the other Chindits at Changi were being treated much more favourably. They were in effect left to their own devices by the Japanese, cooking, washing and entertaining themselves through the long and repetitive days. They were all detailed onto work parties during their time in Singapore, often leading teams on projects such as the building of air-raid shelters and roadways and at one time working on building a new aerodrome for the Japanese Air Force to use. Disease was still a concern, especially dysentery, malaria and beri beri and there was also the continuous worry that you might be sent up-country to work on the infamous Burma Railway.

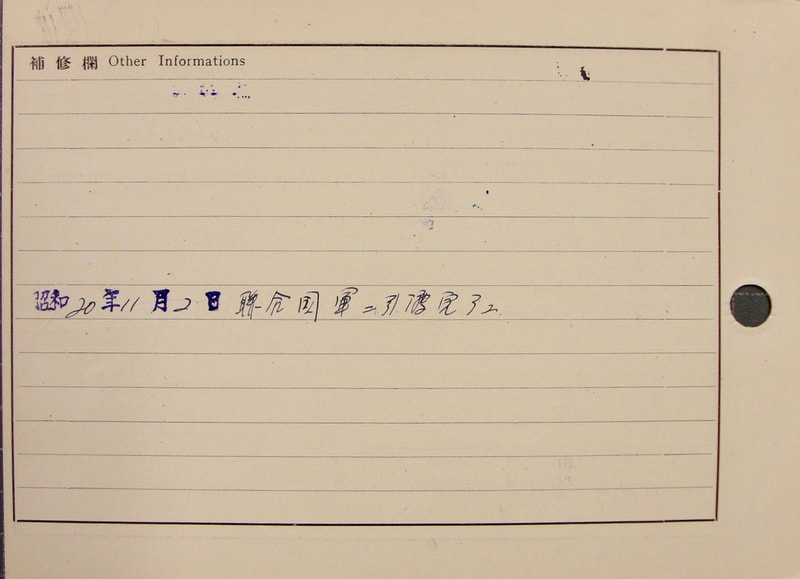

Throughout August 1945, the tension at Changi had become palpable as the news that the war had ended reached the ears of the prisoners. They had often discussed what might happen to them if the Japanese began to lose the war and especially what might happen if the Allies began to bomb the Japanese mainland. They were seriously worried that they might be murdered by their captors in retribution for any civilian casualties back home in Japan. Thankfully, even after the dropping of the two Atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nothing happened to any POW's at Changi and the Union Jack was flying once more over Singapore by the first week of September. According to his POW index card, Jack Longmore was liberated on the 2nd November 1945.

Seem below is another gallery of images in relation to this story, including Jack Longmore's POW index card. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In order to have reached this village during his final days of freedom, Jack must have been washed up on the west banks of the Irrawaddy some miles to the north of where the Brigade had crossed and then proceeded to march directly for India. It is not known whether he was alone at this point, or whether he was in the company of the Gurkha soldiers he had tried to rescue. Didauk is approximately 45 miles from the Irrawaddy across unforgiving and undulating country and is the same number of miles from the sanctuary of the Chindwin River and what was back then Allied held territory. He was effectively half-way home when he was captured by the Japanese.

We know that Squadron Leader Longmore was taken initially to Rangoon Central Jail, where he met up with many of his former Chindit comrades from Operation Longcloth. Then in May, he was taken by air, along with other officers held at Rangoon to the Changi POW Camp in Singapore, to be interrogated by the Japanese secret police, the Kempai-tai. It must be presumed that the Japanese were interested in what Jack and the other officers may have known about the aims and objectives of Wingate's first raid into Burma. In any case, for the next two years, Jack and his comrades were held as prisoners of war in various camps in the local Changi area.

From Captain Tommy Roberts' book, Roll On (Volume One):

On the 30th May, I was moved by air via Bangkok to the island of Singapore. In my party were: Captain Machin, Captain B. Yates, Lieutenants K. Gourlie and Campbell-Paterson and Squadron Leader W. Matheson. We were housed in the old Changi Maternity Hospital. Already there, having been flown from Rangoon the previous week, were: Group Captain G.C. More, Squadron Leader Longmore, Pilot Officer J. Townsend RAF, Captain Vivian Earle and Pilot Officers Jensen and Baggett of the United States Army Air Force.

We were responsible for our own cooking which we managed rather well, with three men having a two-day stint of cooking duty on rotation. Food was decent, but barely sufficient and the Red Cross supplied us with soap and toothpaste and some tins of Malayan foods. With the small amount of money, mostly in the hands of the Americans, we were able to purchase locally some biscuits, bread, tobacco and nut toffee. In general, we were interrogated infrequently, with these sessions attended by Japanese interpreters which we named the Terrifiers. We have been told that soon we will be transferred to a real POW Camp up country, but nothing seems to happen. The RAF and USAAF chaps spend most of their time playing cards. Townsend is learning Nippongo (Japanese), I'm pecking at it too although I find concentrating very difficult.

Jack Longmore's POW number inside Changi was 643, and he had to recite this number in Japanese (roku-shi-san) at the morning and evening roll calls or tenkos, as they were called at the camp. Compared to conditions in Rangoon Jail, where food was scarce and of low quality and where men were expected to sleep forty to a cell-room, Jack, Tommy and the other Chindits at Changi were being treated much more favourably. They were in effect left to their own devices by the Japanese, cooking, washing and entertaining themselves through the long and repetitive days. They were all detailed onto work parties during their time in Singapore, often leading teams on projects such as the building of air-raid shelters and roadways and at one time working on building a new aerodrome for the Japanese Air Force to use. Disease was still a concern, especially dysentery, malaria and beri beri and there was also the continuous worry that you might be sent up-country to work on the infamous Burma Railway.

Throughout August 1945, the tension at Changi had become palpable as the news that the war had ended reached the ears of the prisoners. They had often discussed what might happen to them if the Japanese began to lose the war and especially what might happen if the Allies began to bomb the Japanese mainland. They were seriously worried that they might be murdered by their captors in retribution for any civilian casualties back home in Japan. Thankfully, even after the dropping of the two Atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nothing happened to any POW's at Changi and the Union Jack was flying once more over Singapore by the first week of September. According to his POW index card, Jack Longmore was liberated on the 2nd November 1945.

Seem below is another gallery of images in relation to this story, including Jack Longmore's POW index card. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After Operation Longcloth and with Jack a prisoner of war at Changi, it fell to Flight-Lieutenant Robert Thompson to supply the powers that be with a debrief on how the RAF Liaison sections had performed in Burma. Generally, the feedback was positive and the success of the supply dropping program on the first Chindit expedition was confirmed as one of the great plus points of the entire venture.

This is what Brigadier Wingate thought about their efforts in 1943:

The most important thing to note is that SD (Supply Drop) was a brilliant and unexpected success in 1943. All kinds of gloomy prophesies had been made by the the experts. None was fulfilled. The RAF officers and men provided were of the highest quality. The course of this particular operation did not afford them nearly enough scope to learn as was first hoped, nevertheless they were of great value to the Columns. It is essential to have RAF personnel with Long Range Penetration columns, as they afford the unit: continual air co-operation with rear base, vital air intelligence and the exploitation for calling in strategic bombing raids etc. on previously unknown enemy positions.

To read more about the overall performance of the RAF on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link:

Squadrons 31 and 194 Manna From Heaven

This is what Brigadier Wingate thought about their efforts in 1943:

The most important thing to note is that SD (Supply Drop) was a brilliant and unexpected success in 1943. All kinds of gloomy prophesies had been made by the the experts. None was fulfilled. The RAF officers and men provided were of the highest quality. The course of this particular operation did not afford them nearly enough scope to learn as was first hoped, nevertheless they were of great value to the Columns. It is essential to have RAF personnel with Long Range Penetration columns, as they afford the unit: continual air co-operation with rear base, vital air intelligence and the exploitation for calling in strategic bombing raids etc. on previously unknown enemy positions.

To read more about the overall performance of the RAF on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link:

Squadrons 31 and 194 Manna From Heaven

In January 2019, I was delighted to receive the following email from Alexander Morrison:

Squadron-Leader Cecil Longmore was my great uncle and we have some family materials that might fill in a few more gaps in the Chindit story that you have so generously put together. I shall request his wartime service record, as you recommend. Can I ask if you know anything more about his role as RAF liaison officer, other than what is already recorded on your website?

I have found an obituary for my great uncle written in The Journal of the British Association of Malaysia, August 1964 edition. This may well add some new information to his story for you.

Squadron Leader C. J. Longmore

The recent sudden death of Jack Longmore came as a great shock to his family and friends; his loss is a grievous one to them and he is deeply mourned.

Squadron Leader Longmore commenced his Malayan planting career in 1936 and retired as manager of Gemas Estate in 1957. Jack was not only a most efficient planter with the (then) Kuala Lumpur Rubber Company, but in addition he ran a highly successful sawmill on his estate. He was full of ideas for additional sources of revenue and the only man of the writer’s acquaintance to experiment with growing balsa trees from seed.

Jack was modest and unassuming and it was known to very few that he was an expert flyer with over 500 parachute jumps to his credit; he was also the first pilot to loop-the-loop in a glider. He served under Wingate in the Burma campaign where he was taken prisoner-of-war in 1943.

When he retired he did not remain idle, but took up strawberry cultivation; first in the open at Ballynona, and latterly under cloches at Ummera House, Timoleague, County Cork. He died in harness (so to speak) collapsing while picking his fruit, and surviving only a short time in hospital. The affection in which he was held locally was manifest by the large attendance at his funeral in Timoleague; ex-Malayans, Irish friends and his own garden workers. The inscription on the coffin was as modest as the man himself: Jack Longmore died 25th June, 1964.

To his widow, his six and a half year old son and all who loved him, our deepest sympathy is offered. (Author E.J.C.).

Squadron-Leader Cecil Longmore was my great uncle and we have some family materials that might fill in a few more gaps in the Chindit story that you have so generously put together. I shall request his wartime service record, as you recommend. Can I ask if you know anything more about his role as RAF liaison officer, other than what is already recorded on your website?

I have found an obituary for my great uncle written in The Journal of the British Association of Malaysia, August 1964 edition. This may well add some new information to his story for you.

Squadron Leader C. J. Longmore

The recent sudden death of Jack Longmore came as a great shock to his family and friends; his loss is a grievous one to them and he is deeply mourned.

Squadron Leader Longmore commenced his Malayan planting career in 1936 and retired as manager of Gemas Estate in 1957. Jack was not only a most efficient planter with the (then) Kuala Lumpur Rubber Company, but in addition he ran a highly successful sawmill on his estate. He was full of ideas for additional sources of revenue and the only man of the writer’s acquaintance to experiment with growing balsa trees from seed.

Jack was modest and unassuming and it was known to very few that he was an expert flyer with over 500 parachute jumps to his credit; he was also the first pilot to loop-the-loop in a glider. He served under Wingate in the Burma campaign where he was taken prisoner-of-war in 1943.

When he retired he did not remain idle, but took up strawberry cultivation; first in the open at Ballynona, and latterly under cloches at Ummera House, Timoleague, County Cork. He died in harness (so to speak) collapsing while picking his fruit, and surviving only a short time in hospital. The affection in which he was held locally was manifest by the large attendance at his funeral in Timoleague; ex-Malayans, Irish friends and his own garden workers. The inscription on the coffin was as modest as the man himself: Jack Longmore died 25th June, 1964.

To his widow, his six and a half year old son and all who loved him, our deepest sympathy is offered. (Author E.J.C.).

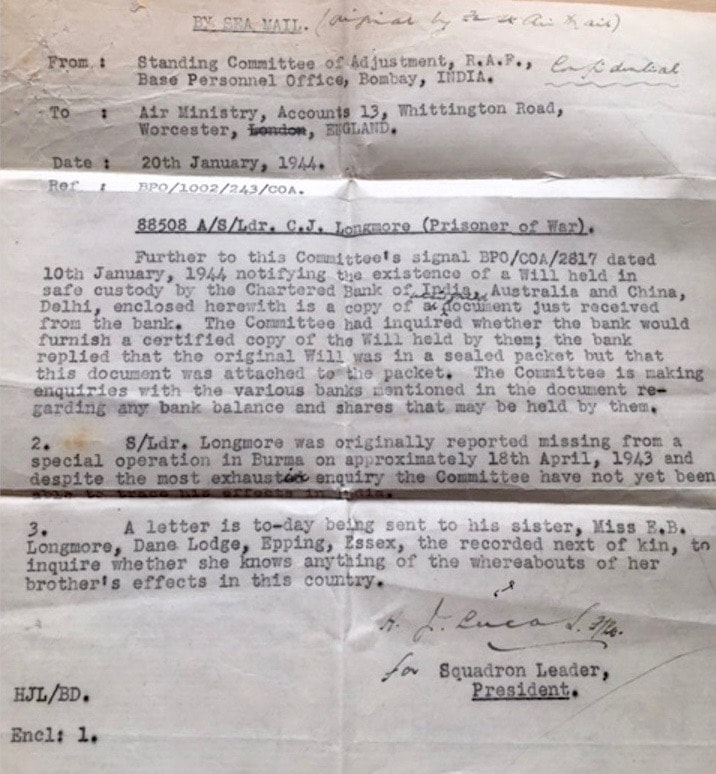

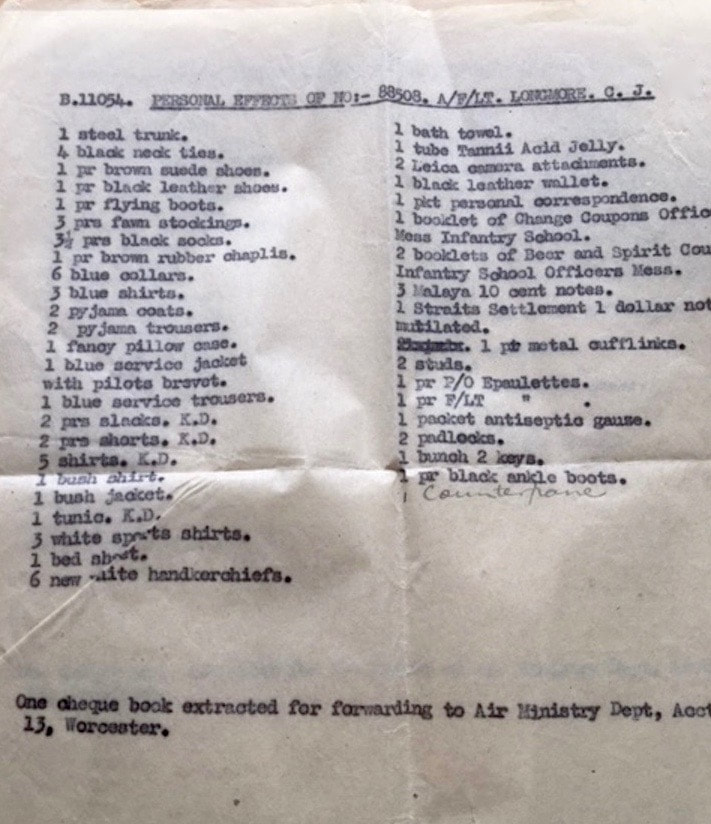

Jack Longmore's papers.

Jack Longmore's papers.

Update 15/05/2021.

Back in January (2021), I was delighted to receive an email contact from Squadron Leader Longmore's son, Michael:

I have just read what was effectively an obituary for my father, and providing a very moving insight into his life. As the article says at the end, I was only six and a half years old when he died.

I doubt there is any more information which you hold about him and his time of service, especially with the depth of the article. However, even now some more details may still be available about him, from how he came to become a Chindit, and what he was involved in during his service. You may have received some more information from my cousin Alexander Morrison, who is mentioned in the revised article on the webpage.

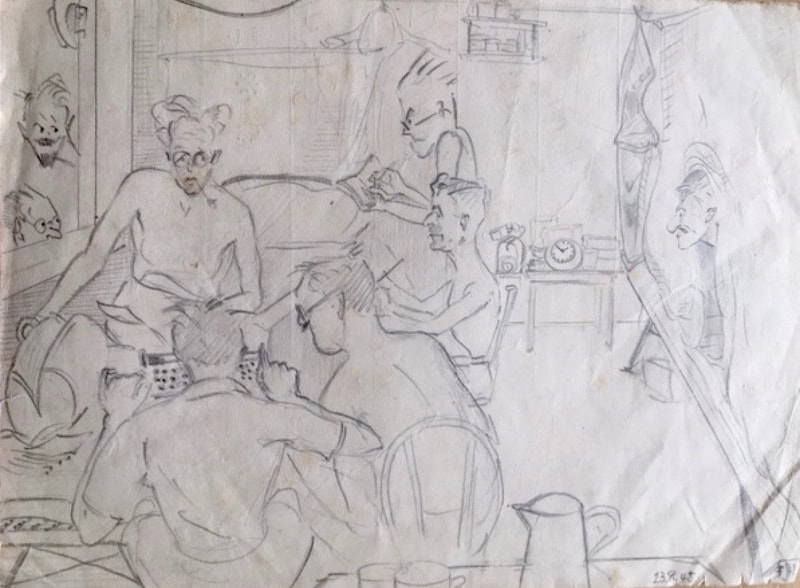

There are papers I hold, with what looks like an original hand drawn coloured map of Burma and correspondence with his sister about his initial disappearance before his capture was confirmed. Documents from his time in Changi including sketches of scenes in the hut, a letter from his commanding officer forbidding an escape plan by plane, a wager about the timing of the end of the war and at least one lewd and long poem.

These would not be easily copied as some have become very feint overtime, but I might be able to photograph various others and send these, if they might be of interest to you. Apart from the papers relating to a planned escape by aeroplane, there are also several pages of handwritten lists of controls found in Japanese aircraft.

Kind regards, Michael Longmore.

As you can imagine, I was excited to hear from Michael and about the documents he described in his email communications. Since first making contact, he has provided me with many of his father's wartime papers and some of these form the basis of this update.

We begin, not surprisingly with the above mentioned escape plan. It was every Allied serviceman's duty to attempt escape whilst a prisoner of war, in order to cause the enemy to expend time and energy in the re-capture of the escapee and hopefully at the great expense of the enemy's actual battle objectives. It was however, almost impossible for Allied personnel in the South East Asian theatre to effect an escape due to their conspicuous white skin and the great distances needed to be travelled to regain Allied held territory.

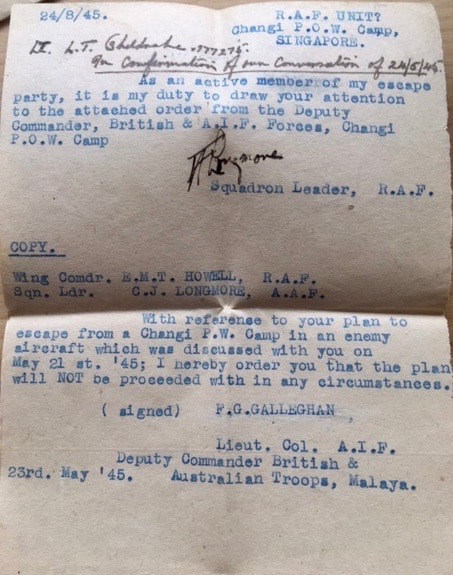

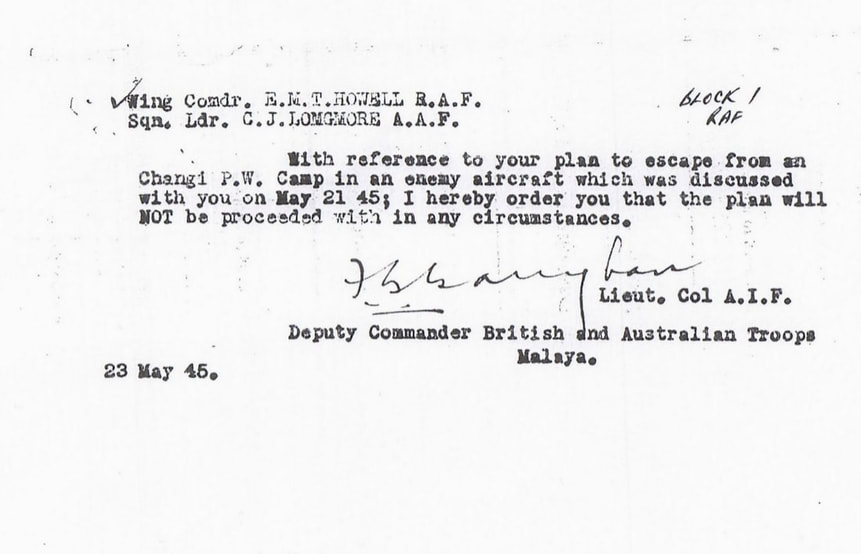

The plan involving Jack Longmore and four other POWs was eventually written out on a five-page document as a record for the RAF Air Ministry back in the United Kingdom. The planned escape was to take place in the summer of 1945 and would entail six officers taking control of a Japanese trainer-type aircraft present at the newly built aerodrome close to the Changi POW Camp in Singapore and fly these back to Allied territory. It is highly likely that Jack Longmore and his co-conspirators had been previously involved in the construction of the aerodrome, as many Allied POWs had been commandeered to work as slave labour for the project.

The six officers involved were: Squadron Leader Longmore, Wing Commander Tom Howell, Lieutenant Jensen of the USAAF, Captain Harold Machin of the 5/15 Punjabi Regiment, Major Evans of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles and Lieutenant Sheldrake, RASC.

The plan was:

The party was to proceed to the aerodrome by the following route. On the east side of the prison camp at the north end was a large cement drain about 3 feet deep. This connected a point about 30 yards north of the main Japanese guard room and about 10 yards east of the hospital kitchen and eventually led under the camp perimeter and barbed wire fence. The drain was deep and afforded plenty of cover for the following 250 yards along the Tanah Merah Road.

Once across the aerodrome perimeter fence the party travelled about one mile to the northeast through long grass, bush and swamp, eventually reaching the east side of the airstrip. There they would wait and observe the comings and goings of the Japanese guards and training planes. The object was to board the aircraft using the door on the port side of the fuselage. They had noticed that the Japanese had carried out the training flights using only one instructor and one pupil per plane and that three to five aircraft would be used at any one time. Each plane would taxi close to the swamp and long grass and then stop for a short time waiting for the other planes to land after each circuit. The plan was for each of the six escapees to quietly board a plane, wait until the pilot had taken off, trimmed the aircraft and was halfway round the circuit, before knocking both the pilot and pupil unconscious with a blunt instrument and taking control of the plane.

If successful in their endeavours, back at the POW Camp mock funerals would be held for the six escapees to allow the Japanese guards to mark these men as dead and strike them from the camp rosters. In the end, this audacious escape never took place and was in fact cancelled and forbidden (see document in the gallery below) by the Deputy Commander, British and Australian Troops (Changi), Lieutenant-Colonel P.G. Callaghan.

Back in January (2021), I was delighted to receive an email contact from Squadron Leader Longmore's son, Michael:

I have just read what was effectively an obituary for my father, and providing a very moving insight into his life. As the article says at the end, I was only six and a half years old when he died.

I doubt there is any more information which you hold about him and his time of service, especially with the depth of the article. However, even now some more details may still be available about him, from how he came to become a Chindit, and what he was involved in during his service. You may have received some more information from my cousin Alexander Morrison, who is mentioned in the revised article on the webpage.

There are papers I hold, with what looks like an original hand drawn coloured map of Burma and correspondence with his sister about his initial disappearance before his capture was confirmed. Documents from his time in Changi including sketches of scenes in the hut, a letter from his commanding officer forbidding an escape plan by plane, a wager about the timing of the end of the war and at least one lewd and long poem.

These would not be easily copied as some have become very feint overtime, but I might be able to photograph various others and send these, if they might be of interest to you. Apart from the papers relating to a planned escape by aeroplane, there are also several pages of handwritten lists of controls found in Japanese aircraft.

Kind regards, Michael Longmore.

As you can imagine, I was excited to hear from Michael and about the documents he described in his email communications. Since first making contact, he has provided me with many of his father's wartime papers and some of these form the basis of this update.

We begin, not surprisingly with the above mentioned escape plan. It was every Allied serviceman's duty to attempt escape whilst a prisoner of war, in order to cause the enemy to expend time and energy in the re-capture of the escapee and hopefully at the great expense of the enemy's actual battle objectives. It was however, almost impossible for Allied personnel in the South East Asian theatre to effect an escape due to their conspicuous white skin and the great distances needed to be travelled to regain Allied held territory.

The plan involving Jack Longmore and four other POWs was eventually written out on a five-page document as a record for the RAF Air Ministry back in the United Kingdom. The planned escape was to take place in the summer of 1945 and would entail six officers taking control of a Japanese trainer-type aircraft present at the newly built aerodrome close to the Changi POW Camp in Singapore and fly these back to Allied territory. It is highly likely that Jack Longmore and his co-conspirators had been previously involved in the construction of the aerodrome, as many Allied POWs had been commandeered to work as slave labour for the project.

The six officers involved were: Squadron Leader Longmore, Wing Commander Tom Howell, Lieutenant Jensen of the USAAF, Captain Harold Machin of the 5/15 Punjabi Regiment, Major Evans of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles and Lieutenant Sheldrake, RASC.

The plan was:

The party was to proceed to the aerodrome by the following route. On the east side of the prison camp at the north end was a large cement drain about 3 feet deep. This connected a point about 30 yards north of the main Japanese guard room and about 10 yards east of the hospital kitchen and eventually led under the camp perimeter and barbed wire fence. The drain was deep and afforded plenty of cover for the following 250 yards along the Tanah Merah Road.

Once across the aerodrome perimeter fence the party travelled about one mile to the northeast through long grass, bush and swamp, eventually reaching the east side of the airstrip. There they would wait and observe the comings and goings of the Japanese guards and training planes. The object was to board the aircraft using the door on the port side of the fuselage. They had noticed that the Japanese had carried out the training flights using only one instructor and one pupil per plane and that three to five aircraft would be used at any one time. Each plane would taxi close to the swamp and long grass and then stop for a short time waiting for the other planes to land after each circuit. The plan was for each of the six escapees to quietly board a plane, wait until the pilot had taken off, trimmed the aircraft and was halfway round the circuit, before knocking both the pilot and pupil unconscious with a blunt instrument and taking control of the plane.

If successful in their endeavours, back at the POW Camp mock funerals would be held for the six escapees to allow the Japanese guards to mark these men as dead and strike them from the camp rosters. In the end, this audacious escape never took place and was in fact cancelled and forbidden (see document in the gallery below) by the Deputy Commander, British and Australian Troops (Changi), Lieutenant-Colonel P.G. Callaghan.

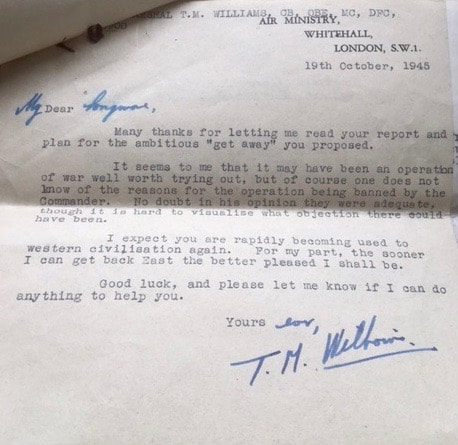

Other documents provided by Michael included a letter from the Air Ministry dated October 19th 1945, congratulating Jack on his planned escape from Changi and wishing him good luck when returning to the UK. There were other papers relating to Jack's POW status, his possessions back in India and the location of his Will. Some of these documents can be viewed in the gallery below.

Also present within the papers was a postcard depicting a Japanese soldier in uniform. On the reverse of the card was the name, Yamamoto Seidai Shigehiro and the postcard was addressed to, Mr. Choy Sonde of Namwon Village, North Jeolla Province, Korea. It is not known why Jack would have had this item in his possession.

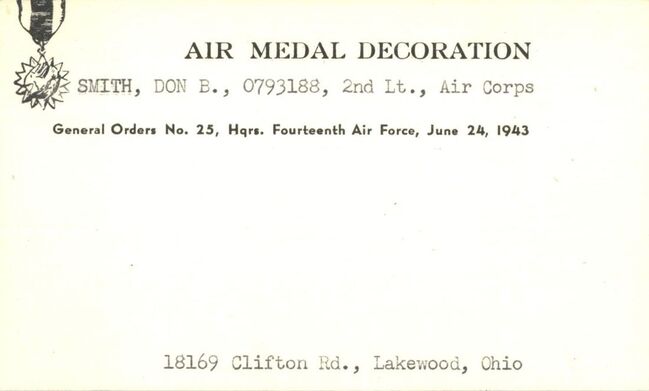

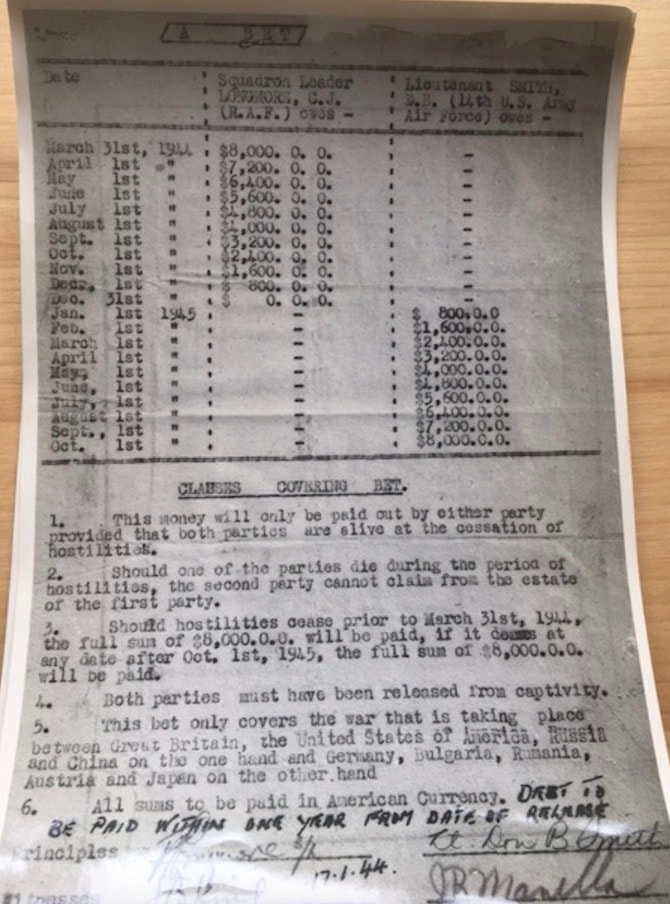

On the brighter side, there was also a typed note relating to a wager Jack undertook with Lt. Don B. Smith of the United States Army Air Force on the 17th January 1944. The basis of the wager was the date for the end of hostilities (the end of the war). Clearly Lt. Smith was far more optimistic and would receive a sliding scale of winnings if the war ended between March and December 1944, with Jack taking the loot if this event happened later, between January and October 1945. Either man could have walked away with as much as 8,000 dollars. The wager document can be seen in the gallery below, it is not known if Lt. Smith paid up!

NB. Lieutenant 0793188 Don B. Smith was from Clifton Road, Lakewood City in the state of Ohio and was a member of the 14th (United States) Air Force. From other documents on line, it is suggested that he had been captured by the Japanese earlier in the war after bailing out of his aircraft over Haiphong in Indochina. He was awarded the United States Air Medal Decoration on his return home.

Also present within the papers was a postcard depicting a Japanese soldier in uniform. On the reverse of the card was the name, Yamamoto Seidai Shigehiro and the postcard was addressed to, Mr. Choy Sonde of Namwon Village, North Jeolla Province, Korea. It is not known why Jack would have had this item in his possession.

On the brighter side, there was also a typed note relating to a wager Jack undertook with Lt. Don B. Smith of the United States Army Air Force on the 17th January 1944. The basis of the wager was the date for the end of hostilities (the end of the war). Clearly Lt. Smith was far more optimistic and would receive a sliding scale of winnings if the war ended between March and December 1944, with Jack taking the loot if this event happened later, between January and October 1945. Either man could have walked away with as much as 8,000 dollars. The wager document can be seen in the gallery below, it is not known if Lt. Smith paid up!

NB. Lieutenant 0793188 Don B. Smith was from Clifton Road, Lakewood City in the state of Ohio and was a member of the 14th (United States) Air Force. From other documents on line, it is suggested that he had been captured by the Japanese earlier in the war after bailing out of his aircraft over Haiphong in Indochina. He was awarded the United States Air Medal Decoration on his return home.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the above update, including one of the sketches mentioned by Michael, of Jack's prison room at Changi. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Commandant Howell, RAF Henlow 1963.

Commandant Howell, RAF Henlow 1963.

Update 21/04/2024.

In March 2024, I was delighted to receive the following email from Michael Howell:

My father Tom Howell and Jack Longmore had a plan to escape from Changi in a stolen Japanese bomber and fly it to Burma. This was planned for May 1945, but the escape never took place due to the concern of Japanese reprisals for those who remained behind at Changi. Would you be interested in the documentary evidence to place on your website?

Of course I was only too pleased to receive Michael's information, in the form of short war-time (and beyond) biography about his father including the planned escape alongside Jack Longmore.

Evelyn Michael Thomas (Tom) Howell (1913-2008) was a career RAF Officer who, at age 18, joined the RAF from school and flew fighters through the 1930s and early 1940s, both in the UK and Egypt. During the early years of WW2 (1939-41), he played a key role at Air Ministry HQ near London as Squadron Leader supporting the provision of air armaments to the fighter squadrons in southeast England which were defending London during the blitz and Luftwaffe bombing raids. Already married with two daughters, and at Squadron Leader rank, he was not an active fighter pilot but did keep up his flying skills well into his early 50s. His last type of certification course was on a Canberra bomber, circa 1960.

In 1941, Tom was transferred to the Far East as Wing Commander (at 28, the youngest in the RAF at the time) arriving by sea to Malaya in early 1942, to take command of a new Air Armament Training Station in Kuantan. But the British were immediately overrun by Japanese forces sweeping down from the north. Hurricane aircraft that he had shipped in from UK were progressively destroyed by Japanese air raids and Tom escaped from Malaya to Singapore, thence to Sumatra and finally to Java, seeking to evade capture. He kept a diary during that period which makes for salutary reading about the challenges of being “on the run”. This has since been typed-up and is available.

Due to loss of all his companions during a Japanese strafing run on a beach, and having a bad dose of malaria, he was taken into captivity in late 1942 and was held in Java (Bandoeng and Batavia) and then Singapore (Changi). He was billeted with James Clavell, a very successful postwar author, who wrote the bestselling novel King Rat about their experiences. The name of the book is due to the exploits of an inmate (non-fictional) of the hut, an American who made a relative fortune by breeding rats and selling them to his fellow prisoners. Tom’s intricately planned May 1945 escape to Burma from Singapore with a colleague in an enemy aircraft was forbidden by his commanding officer due to the anticipated reprisals. Two weeks after liberation while still suffering from the after-effects of malnutrion, he flew an Avro York (converted Lancaster bomber) in stages from Singapore via Burma, India and Persia (Iran) to the UK.

After WW2, Tom advanced to become a senior armaments officer. He was seconded to the Indian Air Force 1955-57, played an important role in Bomber Command in establishing the British nuclear deterrent during 1957-60, and towards the end of his career, was Commandant of the RAF Technical College in Henlow, Bedfordshire 1962-65. He was promoted to Air Vice-Marshal on assuming the role of A/O Commanding RAF Technical Training Command at Brampton in 1965, but retired for personal reasons in 1967. He sadly passed away in 2008, aged 94, and his obituary and official photograph are visible via the following links:

https://www.roll-of-honour.org.uk/h/html/howell-tom.htm

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp135929/evelyn-michael-thomas-howell

Seen below is a copy of the letter sent to Tom Howell and Jack Longmore, denying them permission to undertake their planned escape from Changi by acquiring a Japanese aircraft in May 1945. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Michael Howell for allowing me to add the above information about his father's war-time experiences and his association with Chindit Jack Longmore to my website.

In March 2024, I was delighted to receive the following email from Michael Howell:

My father Tom Howell and Jack Longmore had a plan to escape from Changi in a stolen Japanese bomber and fly it to Burma. This was planned for May 1945, but the escape never took place due to the concern of Japanese reprisals for those who remained behind at Changi. Would you be interested in the documentary evidence to place on your website?

Of course I was only too pleased to receive Michael's information, in the form of short war-time (and beyond) biography about his father including the planned escape alongside Jack Longmore.

Evelyn Michael Thomas (Tom) Howell (1913-2008) was a career RAF Officer who, at age 18, joined the RAF from school and flew fighters through the 1930s and early 1940s, both in the UK and Egypt. During the early years of WW2 (1939-41), he played a key role at Air Ministry HQ near London as Squadron Leader supporting the provision of air armaments to the fighter squadrons in southeast England which were defending London during the blitz and Luftwaffe bombing raids. Already married with two daughters, and at Squadron Leader rank, he was not an active fighter pilot but did keep up his flying skills well into his early 50s. His last type of certification course was on a Canberra bomber, circa 1960.

In 1941, Tom was transferred to the Far East as Wing Commander (at 28, the youngest in the RAF at the time) arriving by sea to Malaya in early 1942, to take command of a new Air Armament Training Station in Kuantan. But the British were immediately overrun by Japanese forces sweeping down from the north. Hurricane aircraft that he had shipped in from UK were progressively destroyed by Japanese air raids and Tom escaped from Malaya to Singapore, thence to Sumatra and finally to Java, seeking to evade capture. He kept a diary during that period which makes for salutary reading about the challenges of being “on the run”. This has since been typed-up and is available.

Due to loss of all his companions during a Japanese strafing run on a beach, and having a bad dose of malaria, he was taken into captivity in late 1942 and was held in Java (Bandoeng and Batavia) and then Singapore (Changi). He was billeted with James Clavell, a very successful postwar author, who wrote the bestselling novel King Rat about their experiences. The name of the book is due to the exploits of an inmate (non-fictional) of the hut, an American who made a relative fortune by breeding rats and selling them to his fellow prisoners. Tom’s intricately planned May 1945 escape to Burma from Singapore with a colleague in an enemy aircraft was forbidden by his commanding officer due to the anticipated reprisals. Two weeks after liberation while still suffering from the after-effects of malnutrion, he flew an Avro York (converted Lancaster bomber) in stages from Singapore via Burma, India and Persia (Iran) to the UK.

After WW2, Tom advanced to become a senior armaments officer. He was seconded to the Indian Air Force 1955-57, played an important role in Bomber Command in establishing the British nuclear deterrent during 1957-60, and towards the end of his career, was Commandant of the RAF Technical College in Henlow, Bedfordshire 1962-65. He was promoted to Air Vice-Marshal on assuming the role of A/O Commanding RAF Technical Training Command at Brampton in 1965, but retired for personal reasons in 1967. He sadly passed away in 2008, aged 94, and his obituary and official photograph are visible via the following links:

https://www.roll-of-honour.org.uk/h/html/howell-tom.htm

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp135929/evelyn-michael-thomas-howell

Seen below is a copy of the letter sent to Tom Howell and Jack Longmore, denying them permission to undertake their planned escape from Changi by acquiring a Japanese aircraft in May 1945. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Michael Howell for allowing me to add the above information about his father's war-time experiences and his association with Chindit Jack Longmore to my website.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, March 2019. With great and sincere thanks to Alexander Morrison and Michael Longmore.