Flight Sergeant Alan Montague Fidler

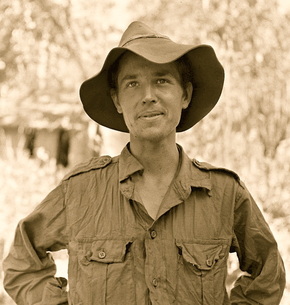

Alan Fidler shortly after returning from Burma.

Alan Fidler shortly after returning from Burma.

Alan Montague Fidler was born on the 10th January 1920 at a place called Steyning, a small rural town and civil parish in the Horsham District of West Sussex. He decided to join the RAF as a boy entrant at the tender age of just fourteen and trained as a wireless operator in England, before being posted to India in the late 1930's. Rising to the Rank of Warrant Officer (RAF Service number 550693) in India, he built up his required flying hours whilst stationed in the Sind District, which today forms part of Pakistan.

Alan Fidler is the paternal uncle of BBC War Corresponsdent, John Simpson CBE. In his book 'Days from a Different World', John remembered the first time he met Uncle Alan (his father's younger brother) in the autumn of 1945:

When I was six, Uncle Alan came home on leave, and I met him for the first time. He looked like everyone's ideal image of the empire-builder: handsome, immensely confident, with the kind of moustache that all colonial officers seemed to have in those days, broad-shouldered and dressed in an excellent pin-striped suit.

He had a blonde woman on his arm who seemed to me to be dazzlingly glamorous. The only way I could tell that he and my father were related was that they were the same size and general build, and their feet stuck out at an identical angle as they walked down the street laughing.

Flight Sergeant Fidler, always looking for excitement and a new challenge, volunteered for the first Chindit operation in the late summer of 1942. He had seen a notice back at his RAF station in India, asking for experts in ground to air communications to join a new and secret unit which was looking to develop new techniques in jungle warfare. Like many of the RAF contingent that signed up with 77 Brigade, Alan had absolutely no idea what he was letting himself in for.

He needn't have worried, he took to Wingate's methods and philosophies like the proverbial duck to water, sometimes quite literally. The emphasis on fitness, of both body and mind appealed greatly to Alan, who thrived during the weeks of training at the Saugor Camp. He was eventually attached to Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters and it seems made quite an impression on his Brigadier. Wingate's ideas for Long Range Penetration would rely heavily upon the skills of the RAF Liaison section in each Chindit column, whose role was to guide the supply aircraft of 31 Squadron safely to the agreed drop zone once the Brigade was inside Burma.

It is probably safe to say that Alan idolised his commander. He was drawn, not only to Wingate's methodology and techniques, but also to his total belief in the attributes of the British soldier. There had built up, during the first two years of the Japanese advance across South East Asia, an impression that the enemy was invincible in the jungle, elevating him almost to the superhuman. Wingate saw the danger of this situation continuing:

"If the British soldier is allowed to get the notion that he cannot take hardships that men of other nations can, he had better reconcile himself to being a member of a third rate nation ... I personally am quite satisfied the British soldier has a better body and a better mind than average humanity. He can not only equal but beat the Japanese."

On the 18th November 1942, just before the final Chindit training exercise at the Jhansi rail terminus, Alan and a few of the other RAF recruits to 77 Brigade, were given special leave dispensation and travelled together to Bombay. This was to be their last chance to left off some steam, before the commencement of Operation Longcloth and the advance into Burma.

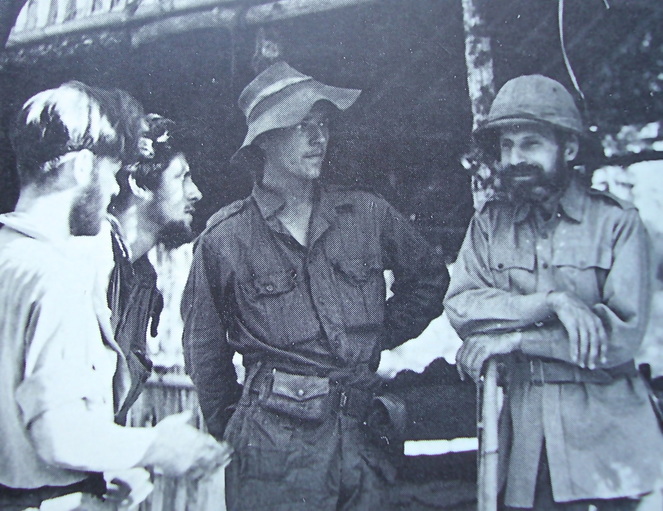

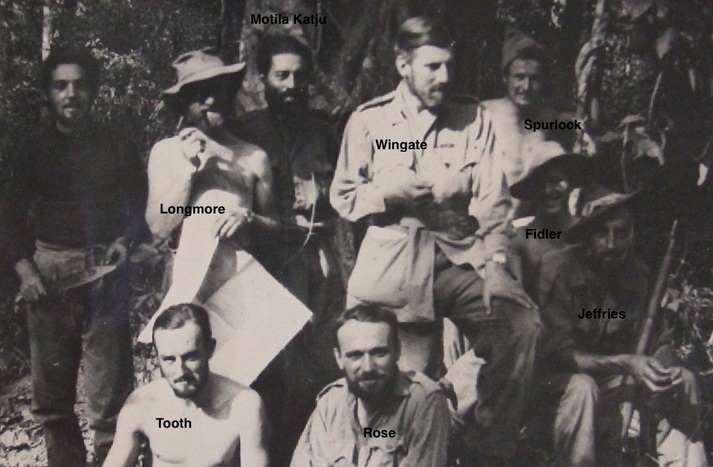

Seen below are two photographs depicting the same moment in time, differing only by a couple of frames from the camera that captured them. These images have appeared in many of the books concerning Wingate's first Chindit expedition of 1943, some profess them to be prior Operation Longcloth, while others suggest they were taken just after Wingate's safe return. Either way, I feel that the photographs illustrate the magnetism of the man and his ability to captivate an audience, including in this instance Flight Sergeant Alan Fidler, who is pictured in both images on Wingate's immediate right.

Please click on either photograph to bring them forward on the page.

Alan Fidler is the paternal uncle of BBC War Corresponsdent, John Simpson CBE. In his book 'Days from a Different World', John remembered the first time he met Uncle Alan (his father's younger brother) in the autumn of 1945:

When I was six, Uncle Alan came home on leave, and I met him for the first time. He looked like everyone's ideal image of the empire-builder: handsome, immensely confident, with the kind of moustache that all colonial officers seemed to have in those days, broad-shouldered and dressed in an excellent pin-striped suit.

He had a blonde woman on his arm who seemed to me to be dazzlingly glamorous. The only way I could tell that he and my father were related was that they were the same size and general build, and their feet stuck out at an identical angle as they walked down the street laughing.

Flight Sergeant Fidler, always looking for excitement and a new challenge, volunteered for the first Chindit operation in the late summer of 1942. He had seen a notice back at his RAF station in India, asking for experts in ground to air communications to join a new and secret unit which was looking to develop new techniques in jungle warfare. Like many of the RAF contingent that signed up with 77 Brigade, Alan had absolutely no idea what he was letting himself in for.

He needn't have worried, he took to Wingate's methods and philosophies like the proverbial duck to water, sometimes quite literally. The emphasis on fitness, of both body and mind appealed greatly to Alan, who thrived during the weeks of training at the Saugor Camp. He was eventually attached to Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters and it seems made quite an impression on his Brigadier. Wingate's ideas for Long Range Penetration would rely heavily upon the skills of the RAF Liaison section in each Chindit column, whose role was to guide the supply aircraft of 31 Squadron safely to the agreed drop zone once the Brigade was inside Burma.

It is probably safe to say that Alan idolised his commander. He was drawn, not only to Wingate's methodology and techniques, but also to his total belief in the attributes of the British soldier. There had built up, during the first two years of the Japanese advance across South East Asia, an impression that the enemy was invincible in the jungle, elevating him almost to the superhuman. Wingate saw the danger of this situation continuing:

"If the British soldier is allowed to get the notion that he cannot take hardships that men of other nations can, he had better reconcile himself to being a member of a third rate nation ... I personally am quite satisfied the British soldier has a better body and a better mind than average humanity. He can not only equal but beat the Japanese."

On the 18th November 1942, just before the final Chindit training exercise at the Jhansi rail terminus, Alan and a few of the other RAF recruits to 77 Brigade, were given special leave dispensation and travelled together to Bombay. This was to be their last chance to left off some steam, before the commencement of Operation Longcloth and the advance into Burma.

Seen below are two photographs depicting the same moment in time, differing only by a couple of frames from the camera that captured them. These images have appeared in many of the books concerning Wingate's first Chindit expedition of 1943, some profess them to be prior Operation Longcloth, while others suggest they were taken just after Wingate's safe return. Either way, I feel that the photographs illustrate the magnetism of the man and his ability to captivate an audience, including in this instance Flight Sergeant Alan Fidler, who is pictured in both images on Wingate's immediate right.

Please click on either photograph to bring them forward on the page.

Wingate and his Brigade HQ moved through the jungles of Burma during the first few weeks of Operation Longcloth, orchestrating the Chindit columns of Northern Group as they carried out their various pre-arranged assignments and demolitions. For the most part things went well and the Brigade suffered only minor casualties. Alan Fidler, along with his RAF comrades in Brigade HQ, Albert Tooth and Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore, successfully delivered their side of the bargain and brought in the planes of 31 Squadron to feed and re-equip the marching Chindit columns.

By early April 1943, Wingate and his Brigade were planning their exit from Burma after six weeks of raiding behind enemy lines. On the 29th March three Chindit units (Columns 7 and 8, plus Brigade HQ) had massed on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River near the town of Inywa. The idea was to get across this wide expanse of water as quickly as possible and then, once over, move off westwards and return to India. Wingate had previously crossed the Irrawaddy at Inywa on the outward journey and thought the Japanese would not expect him to retrace his steps.

Unfortunately, the crossing was contested by a large patrol of Japanese soldiers positioned on the opposite bank of the river. The men in the leading boats soon came under severe machine gun and mortar fire, resulting in many casualties. Wingate, after a speedy consultation with his column commanders, decided to call off the crossing and the dispirited Chindits melted away into the jungle. Columns 7 and 8 soon moved away from the Irrawaddy, both heading roughly south-east. Wingate took his men deep in to the surrounding scrub-jungle close to Inywa, where they would wait patiently for several days until the heat had died down and the enemy had left the area.

During their time hiding out in the jungle, Wingate gave orders for the remaining mules to be killed and that the men should eat the mule flesh to bolster their depleted rations. He also split his Head Quarters up at this time into smaller dispersal groups of around 25-35 men per party. On 7th April, Wingate and his party made a second attempt at crossing the Irrawaddy, this time 25 miles south of Inywa. For two days they searched the riverbank for boats, but Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles could only find one boat and this would take only seven people at a time. They began crossing late that afternoon, but when half of the party were over, automatic fire was heard from the north and the native boatman made off with his craft, leaving the rest of the men stranded on the east bank.

Those who successfully made it across the river included Wingate, Majors Anderson and Jefferies, Captains Aung Thin and Katju, and twenty-four Other Ranks. They were not, however, on the west bank of the river. They were, in fact, on an island in the middle of the Irrawaddy and so they immediately moved on towards the only village (Nyaungbintha) where they found another large boat and made the final crossing at dusk. Once over, they moved on for a couple of miles and then lay up for the night. The mosquitoes in this area were intolerable and they got very little sleep.

Signaller Eric Hutchins was in the last party waiting to cross the river, together with Squadron Leader Longmore, Flight Lieutenant Tooth, Flight Sergeant Fidler, Lieutenant Rose of the Gurkhas, Private Dermody and Private Weston of the King's. Eric remembered:

The first six boat parties made their way safely to the opposite bank. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the opposite bank we could find no trace of the others. Wingate's excuse when we met him later, was he 'thought' we had been captured by the Japanese, whereas he had abandoned us without maps or any means of finding our way back to our own lines.

So we set out west only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Our problems now really began, because we could not find a suitable boat. Eventually we found a boat that had seen better days and decided to take a chance crossing at night, using our rifles as oars. Of course the inevitable happened and the boat capsized.

I and others swam to the west shore, where we had to rescue two of our party who were clutching on to a floating plant because they could not swim. At light of day we found that Squadron Leader Longmore was missing. Later at the end of the war I found out that he had remained clutching the boat and floated down river and was eventually captured. We found we were on another island and right opposite a very large village and most of the inhabitants walked across the shallow water to the island, presumably out of curiosity.

We had lost everything when the boat capsized and had no arms to defend ourselves, except that I still had a hand grenade. We went with the villagers and enjoyed a meal of rice and obtained two sacks of rice, cooking pans, a flint stone to make a fire, salt and juggery, the latter unrefined sugar.

Suddenly there was a commotion in the village and the locals started to disperse, which was a signal to us that the Japs had arrived. We made a quick retreat and proceeded to climb the hills behind the village and make our way westwards. Our progress after that was mainly at night, avoiding paths and villages. I remember the beautiful clear moonlit nights with the stars to guide us. I often look for a constellation set at dead 270 degrees which we used as our direction arrow as we kept walking westwards.

Daytime was spent trying to sleep in the intense heat with no water, setting out at dusk to find water and cook a meal. I was suffering severely from dysentery, but somehow raised the strength to carry on. As we neared the Chindwin we found a small chaung in which were some pools of water containing fish. We caught one by swimming under water, but then became greedy and thought if we threw my grenade into the water we could have a real feast. This was not to be because the grenade failed to explode as I had forgotten to prime it.

On seeing the river valley of the Chindwin we now became over-confident and started to abandon our policy of avoiding footpaths. On rounding a bend we ran into a Japanese sentry guarding the path. We immediately plunged into the jungle to our left, but Weston was captured because he was too weak to react quickly. We were forced to stand in a marsh for thirty-six hours while the Japs set fire to it to try to draw us out. Meanwhile we could hear the screams of Weston as they slowly tortured him to death with their bayonets.

On the second night we came out of the marsh only to walk straight through the Jap occupied village. We walked on down the path leading to the Chindwin and then, practising the usual dispersal drill on leaving a path, hid in the jungle nearby. Within fifteen minutes a party of Japs came down the track, following our footprints by torch light. Fortunately for us they hesitated where our footprints finished and then carried on. This was our cue and we retreated deeper into the jungle.

Within half an hour they were back searching the spot we had left. We were now under real pressure and headed for the Chindwin, but could not find a boat to cross. We were walking along the path on the river bank and came to a small clearing with Lieutenant Rose leading. He suddenly turned round and yelled Japs' and in the sudden rush to retreat I fell over. I scrambled to my feet, leaving behind the rice sack I was carrying. The others had a good fifty yards' start on me and machine gun bullets were whizzing all around. I think I broke the world record for 200 yards and reached the jungle on the opposite side of the clearing before the others.

Here we lost Lieutenant Rose and I heard after the war he was later captured and also survived the prison camp. We decided to regain the hills and walk northwards hoping there would be fewer Japs to encounter in that direction. We came upon a hut in the middle of a paddy field and found a native sitting inside. He immediately beckoned us to lie down in the paddy and pointed to a road about fifty yards away where Jap lorries were moving. He indicated to follow him crawling on our bellies to a small copse, it was here that our miracle occurred.

He brought us food twice a day for three days while we got our strength back. He could not get us a boat but when we drew bamboo poles he understood and on each night visit he brought two bamboo poles. Finally we had enough to make a raft and took them down to the river at the dead of night and our saviour tied them together. We had no money and could not reward him, but gave him a note saying how he had helped us and that he should be rewarded by the British if he produced the document.

This man, a complete stranger, possibly a Buddhist, displayed all the ethics of a Good Samaritan and has remained in my deepest thoughts all my life. That day in 1943 on the banks of the Chindwin I learned to believe in miracles.

I was the only strong swimmer and pushed the raft from the rear. Some of the other survivors were too weak to swim and had to be hauled back on the raft. Eventually we reached the other side and rested for the night. In the morning we walked into the nearest village which was occupied by Gurkhas.

Wingate was my hero before the campaign, but after his deliberate abandonment on the east bank of the Irrawaddy I know he only considered his own safety and not others. He would deliberately abandon anyone whom he considered to be a handicap. This was proved later when our signals officer, Ken Spurlock, who was in Wingate's boat party, was abandoned in a village not far from the Chindwin because he was weak with dysentery. I was weak with dysentery but my companions never abandoned me.

To read more about Lieutenant Rose and his time as a prisoner of war, please click on the following link: Lewis William Rose

By early April 1943, Wingate and his Brigade were planning their exit from Burma after six weeks of raiding behind enemy lines. On the 29th March three Chindit units (Columns 7 and 8, plus Brigade HQ) had massed on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River near the town of Inywa. The idea was to get across this wide expanse of water as quickly as possible and then, once over, move off westwards and return to India. Wingate had previously crossed the Irrawaddy at Inywa on the outward journey and thought the Japanese would not expect him to retrace his steps.

Unfortunately, the crossing was contested by a large patrol of Japanese soldiers positioned on the opposite bank of the river. The men in the leading boats soon came under severe machine gun and mortar fire, resulting in many casualties. Wingate, after a speedy consultation with his column commanders, decided to call off the crossing and the dispirited Chindits melted away into the jungle. Columns 7 and 8 soon moved away from the Irrawaddy, both heading roughly south-east. Wingate took his men deep in to the surrounding scrub-jungle close to Inywa, where they would wait patiently for several days until the heat had died down and the enemy had left the area.

During their time hiding out in the jungle, Wingate gave orders for the remaining mules to be killed and that the men should eat the mule flesh to bolster their depleted rations. He also split his Head Quarters up at this time into smaller dispersal groups of around 25-35 men per party. On 7th April, Wingate and his party made a second attempt at crossing the Irrawaddy, this time 25 miles south of Inywa. For two days they searched the riverbank for boats, but Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles could only find one boat and this would take only seven people at a time. They began crossing late that afternoon, but when half of the party were over, automatic fire was heard from the north and the native boatman made off with his craft, leaving the rest of the men stranded on the east bank.

Those who successfully made it across the river included Wingate, Majors Anderson and Jefferies, Captains Aung Thin and Katju, and twenty-four Other Ranks. They were not, however, on the west bank of the river. They were, in fact, on an island in the middle of the Irrawaddy and so they immediately moved on towards the only village (Nyaungbintha) where they found another large boat and made the final crossing at dusk. Once over, they moved on for a couple of miles and then lay up for the night. The mosquitoes in this area were intolerable and they got very little sleep.

Signaller Eric Hutchins was in the last party waiting to cross the river, together with Squadron Leader Longmore, Flight Lieutenant Tooth, Flight Sergeant Fidler, Lieutenant Rose of the Gurkhas, Private Dermody and Private Weston of the King's. Eric remembered:

The first six boat parties made their way safely to the opposite bank. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the opposite bank we could find no trace of the others. Wingate's excuse when we met him later, was he 'thought' we had been captured by the Japanese, whereas he had abandoned us without maps or any means of finding our way back to our own lines.

So we set out west only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Our problems now really began, because we could not find a suitable boat. Eventually we found a boat that had seen better days and decided to take a chance crossing at night, using our rifles as oars. Of course the inevitable happened and the boat capsized.

I and others swam to the west shore, where we had to rescue two of our party who were clutching on to a floating plant because they could not swim. At light of day we found that Squadron Leader Longmore was missing. Later at the end of the war I found out that he had remained clutching the boat and floated down river and was eventually captured. We found we were on another island and right opposite a very large village and most of the inhabitants walked across the shallow water to the island, presumably out of curiosity.

We had lost everything when the boat capsized and had no arms to defend ourselves, except that I still had a hand grenade. We went with the villagers and enjoyed a meal of rice and obtained two sacks of rice, cooking pans, a flint stone to make a fire, salt and juggery, the latter unrefined sugar.

Suddenly there was a commotion in the village and the locals started to disperse, which was a signal to us that the Japs had arrived. We made a quick retreat and proceeded to climb the hills behind the village and make our way westwards. Our progress after that was mainly at night, avoiding paths and villages. I remember the beautiful clear moonlit nights with the stars to guide us. I often look for a constellation set at dead 270 degrees which we used as our direction arrow as we kept walking westwards.

Daytime was spent trying to sleep in the intense heat with no water, setting out at dusk to find water and cook a meal. I was suffering severely from dysentery, but somehow raised the strength to carry on. As we neared the Chindwin we found a small chaung in which were some pools of water containing fish. We caught one by swimming under water, but then became greedy and thought if we threw my grenade into the water we could have a real feast. This was not to be because the grenade failed to explode as I had forgotten to prime it.

On seeing the river valley of the Chindwin we now became over-confident and started to abandon our policy of avoiding footpaths. On rounding a bend we ran into a Japanese sentry guarding the path. We immediately plunged into the jungle to our left, but Weston was captured because he was too weak to react quickly. We were forced to stand in a marsh for thirty-six hours while the Japs set fire to it to try to draw us out. Meanwhile we could hear the screams of Weston as they slowly tortured him to death with their bayonets.

On the second night we came out of the marsh only to walk straight through the Jap occupied village. We walked on down the path leading to the Chindwin and then, practising the usual dispersal drill on leaving a path, hid in the jungle nearby. Within fifteen minutes a party of Japs came down the track, following our footprints by torch light. Fortunately for us they hesitated where our footprints finished and then carried on. This was our cue and we retreated deeper into the jungle.

Within half an hour they were back searching the spot we had left. We were now under real pressure and headed for the Chindwin, but could not find a boat to cross. We were walking along the path on the river bank and came to a small clearing with Lieutenant Rose leading. He suddenly turned round and yelled Japs' and in the sudden rush to retreat I fell over. I scrambled to my feet, leaving behind the rice sack I was carrying. The others had a good fifty yards' start on me and machine gun bullets were whizzing all around. I think I broke the world record for 200 yards and reached the jungle on the opposite side of the clearing before the others.

Here we lost Lieutenant Rose and I heard after the war he was later captured and also survived the prison camp. We decided to regain the hills and walk northwards hoping there would be fewer Japs to encounter in that direction. We came upon a hut in the middle of a paddy field and found a native sitting inside. He immediately beckoned us to lie down in the paddy and pointed to a road about fifty yards away where Jap lorries were moving. He indicated to follow him crawling on our bellies to a small copse, it was here that our miracle occurred.

He brought us food twice a day for three days while we got our strength back. He could not get us a boat but when we drew bamboo poles he understood and on each night visit he brought two bamboo poles. Finally we had enough to make a raft and took them down to the river at the dead of night and our saviour tied them together. We had no money and could not reward him, but gave him a note saying how he had helped us and that he should be rewarded by the British if he produced the document.

This man, a complete stranger, possibly a Buddhist, displayed all the ethics of a Good Samaritan and has remained in my deepest thoughts all my life. That day in 1943 on the banks of the Chindwin I learned to believe in miracles.

I was the only strong swimmer and pushed the raft from the rear. Some of the other survivors were too weak to swim and had to be hauled back on the raft. Eventually we reached the other side and rested for the night. In the morning we walked into the nearest village which was occupied by Gurkhas.

Wingate was my hero before the campaign, but after his deliberate abandonment on the east bank of the Irrawaddy I know he only considered his own safety and not others. He would deliberately abandon anyone whom he considered to be a handicap. This was proved later when our signals officer, Ken Spurlock, who was in Wingate's boat party, was abandoned in a village not far from the Chindwin because he was weak with dysentery. I was weak with dysentery but my companions never abandoned me.

To read more about Lieutenant Rose and his time as a prisoner of war, please click on the following link: Lewis William Rose

In the book 'Days from a Different World', John Simpson describes his uncle's seemingly difficult relationship with the mules that carried the wireless set and other equipment. Three animals were required to carry the batteries, charger and the 1082/88 wireless set, which had been the standard set for the Blenheim Bomber during WW2. These mules tended to be the larger examples imported from Argentina and the United States, rather than the smaller specimens from India.

"Alan found his particular mules a serious nuisance. One of them tended to get excited in the claustrophobic conditions of the forest, and when a Japanese patrol passed by, it almost gave Alan's position away by braying noisily."

Also described in the book was an incident just before the aborted crossing at Inywa, when Alan and a Chindit companion became separated from Brigade HQ:

Sometimes the Japanese would dress the dead bodies of Burmese villagers in Japanese uniforms and tie them to the upper branches of trees in the firing position, as if they were snipers. Late one afternoon, as they were looking for a convenient place to set up their transmitting equipment, Alan and his partner spotted one of the supposed snipers and fired.

A six-man Japanese patrol, hiding close by, heard the shots and burst through the undergrowth, trapping them. Alan and his companion were seized and knocked to the ground. The Japanese tied their hands, then marched them triumphantly along the jungle path towards their base. Both men were determined to escape, and they walked slowly, so that a short gap built up between them and the Japanese soldiers in front.

Choosing his moment, Alan threw himself into the thick jungle to his left, and the other man followed him. Wingate had always taught them to move independently through the forest, and they headed off separately for the stream they knew would be somewhere ahead of them. The Japanese fired at random into the thick vegetation, but were reluctant to follow. Alan reached the stream, then walked down through the cool water to a convenient little beach on a bend. Within a couple of minutes his companion found him. They cut each other's ropes, and decided to hide out until the hunt had died down.

In telling the story during the years to come, Alan didn't try to present himself as the hero of the adventure; but he disliked his partner intensely. 'A real know-it-all', he described him, 'a line-shooter.'

They decided to wait until dark, and then head back to the place where they had hidden their mules and their equipment; they believed, rightly as it turned out, that the Japanese hadn't discovered these things. As they were walking silently through the trees they heard voices close by and saw lights. A dozen or so men were walking in line along a pathway, carrying lanterns.

'They're Burmese,' whispered the other man. 'Must be a funeral party. We should just slip out behind them and follow them. That way we can get closer to the village and save a bit of time.' Alan agreed. They waited till the last man had passed, then stepped on to the path behind him. Fifty yards farther down, the man ahead of Alan turned round and his lantern shone full on his face and uniform. They weren't following a Burmese funeral party; it was a Japanese patrol searching for them.

Alan was always quick-tempered. He said later that he shouted at his companion, 'You bloody idiot, these aren't Burmese, they're bloody Japs.' He probably didn't shout at all; but the Japanese were alerted anyway. Both men had to throw themselves off the path into the jungle once again, with more bullets cutting through the foliage about their heads, and they had to find the same stream all over again.

They got away successfully, and duly reached their mules and their equipment; but Alan couldn't stop belabouring the know-it-all for making such a mistake. After they rejoined the main column Wingate made Alan his personal wireless operator, and in spite of the difference in rank, the difficult jungle conditions brought them close together.

After Operation Longcloth was over, Alan spent many weeks recuperating back in India, including a stay in hospital at Imphal. Eventually he returned to his RAF unit, but his health did not improve enough for him to be considered for further combat duties. He would in fact suffer from recurring bouts of malaria for the rest of his life. In October 1943 Alan's mother, Eva Fidler, received a telegram from the War Office informing her that her son was recovering well and no longer on the seriously ill list.

The first Chindit operation was never regarded as being a triumph in military terms, indeed it had some very high profiled detractors and critics back at India Command. However, the mission had proved that the Japanese could be at least equalled in the Burmese jungle and the powers that be, including Winston Churchill looked to use the expedition as a propaganda tool in the British Press. An example of this came in the form a short article in the Daily Mail, dated 7th July 1943:

Wingate's Follies, Get Back From Jungle

These grinning, bearded men are back on British territory after three months spent behind the Japanese lines in the Burma jungle. They are members of Brigadier Wingate's famous expedition (Wingate's Follies) which penetrated more than 200 miles into Japanese-occupied land destroying dumps, cutting communications, and collecting valuable information. They lived on the country apart from supplies dropped by parachute in the jungle clearings.

Alongside the short article was a photograph of five members of 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, including 5 Column commander, Major Bernard Fergusson and Flight Sergeant Alan Fidler. A rather damaged example of this newspaper cutting can be viewed in the final gallery of images for this story shown below.

On the 24th March 1944, Alan received the news that Orde Wingate had perished in a plane crash whilst visiting the various forward bases in Burma during the second Chindit operation. Like many of the men who had served under this unconventional and eccentric leader, Alan was totally devastated.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story, including portraits of some of the men that eventually crossed the Irrawaddy River with Flight Sergeant Fidler in early April 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

"Alan found his particular mules a serious nuisance. One of them tended to get excited in the claustrophobic conditions of the forest, and when a Japanese patrol passed by, it almost gave Alan's position away by braying noisily."

Also described in the book was an incident just before the aborted crossing at Inywa, when Alan and a Chindit companion became separated from Brigade HQ:

Sometimes the Japanese would dress the dead bodies of Burmese villagers in Japanese uniforms and tie them to the upper branches of trees in the firing position, as if they were snipers. Late one afternoon, as they were looking for a convenient place to set up their transmitting equipment, Alan and his partner spotted one of the supposed snipers and fired.

A six-man Japanese patrol, hiding close by, heard the shots and burst through the undergrowth, trapping them. Alan and his companion were seized and knocked to the ground. The Japanese tied their hands, then marched them triumphantly along the jungle path towards their base. Both men were determined to escape, and they walked slowly, so that a short gap built up between them and the Japanese soldiers in front.

Choosing his moment, Alan threw himself into the thick jungle to his left, and the other man followed him. Wingate had always taught them to move independently through the forest, and they headed off separately for the stream they knew would be somewhere ahead of them. The Japanese fired at random into the thick vegetation, but were reluctant to follow. Alan reached the stream, then walked down through the cool water to a convenient little beach on a bend. Within a couple of minutes his companion found him. They cut each other's ropes, and decided to hide out until the hunt had died down.

In telling the story during the years to come, Alan didn't try to present himself as the hero of the adventure; but he disliked his partner intensely. 'A real know-it-all', he described him, 'a line-shooter.'

They decided to wait until dark, and then head back to the place where they had hidden their mules and their equipment; they believed, rightly as it turned out, that the Japanese hadn't discovered these things. As they were walking silently through the trees they heard voices close by and saw lights. A dozen or so men were walking in line along a pathway, carrying lanterns.

'They're Burmese,' whispered the other man. 'Must be a funeral party. We should just slip out behind them and follow them. That way we can get closer to the village and save a bit of time.' Alan agreed. They waited till the last man had passed, then stepped on to the path behind him. Fifty yards farther down, the man ahead of Alan turned round and his lantern shone full on his face and uniform. They weren't following a Burmese funeral party; it was a Japanese patrol searching for them.

Alan was always quick-tempered. He said later that he shouted at his companion, 'You bloody idiot, these aren't Burmese, they're bloody Japs.' He probably didn't shout at all; but the Japanese were alerted anyway. Both men had to throw themselves off the path into the jungle once again, with more bullets cutting through the foliage about their heads, and they had to find the same stream all over again.

They got away successfully, and duly reached their mules and their equipment; but Alan couldn't stop belabouring the know-it-all for making such a mistake. After they rejoined the main column Wingate made Alan his personal wireless operator, and in spite of the difference in rank, the difficult jungle conditions brought them close together.

After Operation Longcloth was over, Alan spent many weeks recuperating back in India, including a stay in hospital at Imphal. Eventually he returned to his RAF unit, but his health did not improve enough for him to be considered for further combat duties. He would in fact suffer from recurring bouts of malaria for the rest of his life. In October 1943 Alan's mother, Eva Fidler, received a telegram from the War Office informing her that her son was recovering well and no longer on the seriously ill list.

The first Chindit operation was never regarded as being a triumph in military terms, indeed it had some very high profiled detractors and critics back at India Command. However, the mission had proved that the Japanese could be at least equalled in the Burmese jungle and the powers that be, including Winston Churchill looked to use the expedition as a propaganda tool in the British Press. An example of this came in the form a short article in the Daily Mail, dated 7th July 1943:

Wingate's Follies, Get Back From Jungle

These grinning, bearded men are back on British territory after three months spent behind the Japanese lines in the Burma jungle. They are members of Brigadier Wingate's famous expedition (Wingate's Follies) which penetrated more than 200 miles into Japanese-occupied land destroying dumps, cutting communications, and collecting valuable information. They lived on the country apart from supplies dropped by parachute in the jungle clearings.

Alongside the short article was a photograph of five members of 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, including 5 Column commander, Major Bernard Fergusson and Flight Sergeant Alan Fidler. A rather damaged example of this newspaper cutting can be viewed in the final gallery of images for this story shown below.

On the 24th March 1944, Alan received the news that Orde Wingate had perished in a plane crash whilst visiting the various forward bases in Burma during the second Chindit operation. Like many of the men who had served under this unconventional and eccentric leader, Alan was totally devastated.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story, including portraits of some of the men that eventually crossed the Irrawaddy River with Flight Sergeant Fidler in early April 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After the war, Alan joined the Malayan Police Force, working as a Senior Intelligence Officer during the Communist Emergency. On retirement he returned to England and became a leading figure with the Chindits Old Comrades Association, ensuring that the name of the Chindits and their originator, Orde Wingate was kept alive.

As with so many veterans from the Burma Campaign, and particularly those who had been held as prisoners of war, Alan maintained his mistrust and dislike of the Japanese throughout his life. A quote from another book written by John Simpson, 'Not Quite World's End', paints a fairly accurate picture of Alan's attitude to his former foe:

"To call Uncle Alan anti-Japanese scarcely began to touch his emotional response to country. I remembered coming home and telling him, after my first visit to Tokyo in 1979, what a wonderfully civilised place it was. I thought he was going to have a major infarction.

'Bloody animals,' he spluttered. It was some moments before he felt strong enough to pick up his gin and tonic again, and he scarcely spoke to me for the crest of evening."

Alan Montague Fidler passed away in December 1970, his death was registered in the council offices at Maidstone in Kent. In October 2013 I attempted to make contact with John Simpson via the BBC and by letter. Sadly, I was not able to reach him at that time. I sincerely hope that he will enjoy reading about his uncle on these website pages at some point in the future.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, with additional information from the books of John Simpson CBE. January 2016.

As with so many veterans from the Burma Campaign, and particularly those who had been held as prisoners of war, Alan maintained his mistrust and dislike of the Japanese throughout his life. A quote from another book written by John Simpson, 'Not Quite World's End', paints a fairly accurate picture of Alan's attitude to his former foe:

"To call Uncle Alan anti-Japanese scarcely began to touch his emotional response to country. I remembered coming home and telling him, after my first visit to Tokyo in 1979, what a wonderfully civilised place it was. I thought he was going to have a major infarction.

'Bloody animals,' he spluttered. It was some moments before he felt strong enough to pick up his gin and tonic again, and he scarcely spoke to me for the crest of evening."

Alan Montague Fidler passed away in December 1970, his death was registered in the council offices at Maidstone in Kent. In October 2013 I attempted to make contact with John Simpson via the BBC and by letter. Sadly, I was not able to reach him at that time. I sincerely hope that he will enjoy reading about his uncle on these website pages at some point in the future.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, with additional information from the books of John Simpson CBE. January 2016.