Captain Roy McKenzie

The family request for information about Roy McKenzie placed on the Burma Star website, was one of the first Chindit stories I ever read concerning a survivor of Operation Longcloth. Nephew Jack Oullette placed the material on the website I am guessing, sometime in the early 2000's, but sadly his given email contact address is now unobtainable. My hope is that by reproducing the information here, this might somehow re-open the communication channel and allow us to make contact and exchange details about the life of his Uncle Roy.

Whether this happens or not is down to my old friend serendipity, but in any event the story of Roy McKenzie is more than worthy and should take it's place amongst these website pages.

Roy McKenzie was originally from Ontario, Canada, but had made his own way over to England at the beginning of the war and joined the British Army. He was to become to my knowledge, one of three Canadians to take part in the Chindit operation of 1943. The others being Kenneth Wheatley who acted as Air liaison for 8 Column on Longcloth and George Faulkner who was chief medic in 2 Column and who later wrote the medical debrief contained within Wingate's own official report for 1943.

Here is what Jack Oullette wrote about his Uncle, as seen on the Burma Star website pages:

Canadian born

Captain Roy McKenzie

Seaforth Highlanders

3rd Btn 2nd Gurkha Rifles (see Regimental cap badge depicted above)

Muleteer Transportation Officer

3 Column 77th Brigade in 1943

My uncle, Roy McKenzie, returned briefly to visit my parents after the war, in the uniform of Captain in the British Army. He was accompanied for a short time by another uncle, both brothers of my mother, who was a Private in the U.S. Army, 82nd Airborne Division. I just about remember this, being about 8 years old at the time, and it seemed to me that they flitted in and out of my life like a lost post-card. They were my heroes then, for an instant in time, and still are in spite of time and circumstances.

Roy left a small steamer trunk with my mother and it wasn't long before I gained access to discover an assortment of keepsakes with, as I recall, some weapons, including two "kukri" knives, and photos, letters, etc. My little adventure was soon discovered, and this treasure chest was removed from my sight as quickly as it's owner had vanished. When I asked my mother where my uncles had disappeared to the answer was always sketchy and remained so over the years. I was told something to the effect that they had been "different" when they returned, albeit that they had, after all, been pretty rough around the edges before they had enlisted, the sons of a widowed mother during the depression. But they knew how to party in a serious way when the War was over, like many returned men, and they must have made quite a mess in my little home town and turned their sister into "the enemy", since she vowed that she would not have them back.

And so it was; I never saw them again and they were hardly ever spoken of again. "These things happen" has never been quite adequate for me and I've tried to put their stories together, starting with Captain Roy McKenzie, British Army, possibly Military Cross, Muleteer transportation officer, 3 Column, 1st Chindit Expedition in 1943.

Roy obviously made his way to the U.K. early in the war and his trail has been picked up in 1943 as a Captain in the Chindits, attached to the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Ghurkha Rifles, part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. According to Harold James, (Lt. in the same unit at the time, and author of "Across the Threshold of Battle") he was a transportation officer, which was not an official title but a job to be done in the "3 Column" section of the brigade under Major Michael "Mad Mike" Calvert. Details are sketchy, but he apparently led his muleteers, with the column, across the river into Burma and participated in the demolition of the railway facilities as well as other operations. He is said to have been responsible for at least one ambush of Japanese troops, helping to make possible the railway attack.

Following these operations behind the Japanese lines, Wingate split up his brigade and sent them back to India in their various ways and Captain McKenzie was apparently charged with leading a group back. We find him, according to James, back in India with the rest of the survivors of this very difficult raid, taking leave and "r and r" (rest and recuperation) in Kashmir. Beyond that I have not been able to trace Uncle Roy's whereabouts or activities until he returned to visit my parents briefly after the War. I have not been able to verify anything in relation to his possible decorations or what became of him after the War, beyond a couple of reports that he was seen in Windsor, Ontario.

Although it is late, I would certainly value any information about Roy that might turn up. I regret not knowing him as I grew up and not knowing sooner how this brave soldier served his King and Country.

As a postscript to Jack's story, Gavin Edgerley-Harris - Assistant Curator and Archivist of the Canadian Military Museum added:

Roy McKenzie was commissioned into the Seaforth Highlanders on 2nd November 1942 and was seconded to 3rd Battalion, 2nd Gurkhas. He served in No. 3 Column 77th Brigade as Mule officer. He was engaged in the successful operation around Nankan Village on 6th March 1943. On return to India continued with the Battalion and accompanied it to Burma once more, seeing further service in the Arakan. Captain McKenzie was demobilised 1945.

His medals were: 1939-45 Star, Burma Star, Defence Medal and War Medal.

Whether this happens or not is down to my old friend serendipity, but in any event the story of Roy McKenzie is more than worthy and should take it's place amongst these website pages.

Roy McKenzie was originally from Ontario, Canada, but had made his own way over to England at the beginning of the war and joined the British Army. He was to become to my knowledge, one of three Canadians to take part in the Chindit operation of 1943. The others being Kenneth Wheatley who acted as Air liaison for 8 Column on Longcloth and George Faulkner who was chief medic in 2 Column and who later wrote the medical debrief contained within Wingate's own official report for 1943.

Here is what Jack Oullette wrote about his Uncle, as seen on the Burma Star website pages:

Canadian born

Captain Roy McKenzie

Seaforth Highlanders

3rd Btn 2nd Gurkha Rifles (see Regimental cap badge depicted above)

Muleteer Transportation Officer

3 Column 77th Brigade in 1943

My uncle, Roy McKenzie, returned briefly to visit my parents after the war, in the uniform of Captain in the British Army. He was accompanied for a short time by another uncle, both brothers of my mother, who was a Private in the U.S. Army, 82nd Airborne Division. I just about remember this, being about 8 years old at the time, and it seemed to me that they flitted in and out of my life like a lost post-card. They were my heroes then, for an instant in time, and still are in spite of time and circumstances.

Roy left a small steamer trunk with my mother and it wasn't long before I gained access to discover an assortment of keepsakes with, as I recall, some weapons, including two "kukri" knives, and photos, letters, etc. My little adventure was soon discovered, and this treasure chest was removed from my sight as quickly as it's owner had vanished. When I asked my mother where my uncles had disappeared to the answer was always sketchy and remained so over the years. I was told something to the effect that they had been "different" when they returned, albeit that they had, after all, been pretty rough around the edges before they had enlisted, the sons of a widowed mother during the depression. But they knew how to party in a serious way when the War was over, like many returned men, and they must have made quite a mess in my little home town and turned their sister into "the enemy", since she vowed that she would not have them back.

And so it was; I never saw them again and they were hardly ever spoken of again. "These things happen" has never been quite adequate for me and I've tried to put their stories together, starting with Captain Roy McKenzie, British Army, possibly Military Cross, Muleteer transportation officer, 3 Column, 1st Chindit Expedition in 1943.

Roy obviously made his way to the U.K. early in the war and his trail has been picked up in 1943 as a Captain in the Chindits, attached to the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Ghurkha Rifles, part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. According to Harold James, (Lt. in the same unit at the time, and author of "Across the Threshold of Battle") he was a transportation officer, which was not an official title but a job to be done in the "3 Column" section of the brigade under Major Michael "Mad Mike" Calvert. Details are sketchy, but he apparently led his muleteers, with the column, across the river into Burma and participated in the demolition of the railway facilities as well as other operations. He is said to have been responsible for at least one ambush of Japanese troops, helping to make possible the railway attack.

Following these operations behind the Japanese lines, Wingate split up his brigade and sent them back to India in their various ways and Captain McKenzie was apparently charged with leading a group back. We find him, according to James, back in India with the rest of the survivors of this very difficult raid, taking leave and "r and r" (rest and recuperation) in Kashmir. Beyond that I have not been able to trace Uncle Roy's whereabouts or activities until he returned to visit my parents briefly after the War. I have not been able to verify anything in relation to his possible decorations or what became of him after the War, beyond a couple of reports that he was seen in Windsor, Ontario.

Although it is late, I would certainly value any information about Roy that might turn up. I regret not knowing him as I grew up and not knowing sooner how this brave soldier served his King and Country.

As a postscript to Jack's story, Gavin Edgerley-Harris - Assistant Curator and Archivist of the Canadian Military Museum added:

Roy McKenzie was commissioned into the Seaforth Highlanders on 2nd November 1942 and was seconded to 3rd Battalion, 2nd Gurkhas. He served in No. 3 Column 77th Brigade as Mule officer. He was engaged in the successful operation around Nankan Village on 6th March 1943. On return to India continued with the Battalion and accompanied it to Burma once more, seeing further service in the Arakan. Captain McKenzie was demobilised 1945.

His medals were: 1939-45 Star, Burma Star, Defence Medal and War Medal.

So that is what the family know about Roy and his time in WW2. In 2008 I visited Burma with my family and on that trip was a Burma campaign veteran named Denis Gudgeon. He had known Roy from their time together in Column 3, where Denis had spent many of the long and arduous marches that year in the company of Captain McKenzie, or 'Mac' as he was known to his fellow officers. Denis remembered Captain McKenzie fondly and recalled that:

Mac was a lovely genuine man who always considered the junior officers viewpoint and ideas, even if he rarely acted upon them.

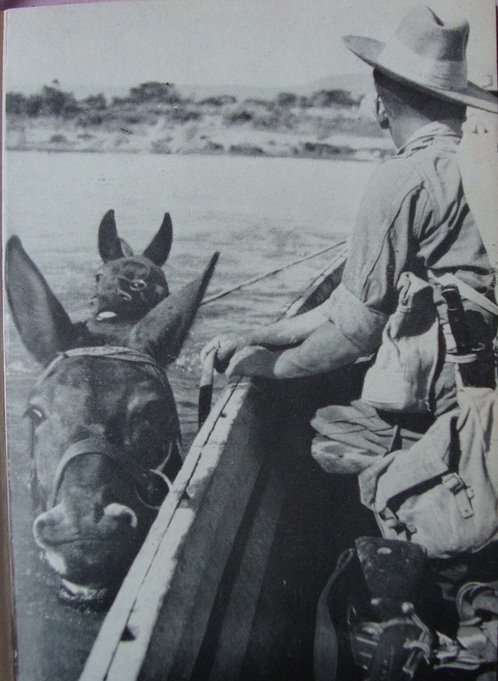

As Jack has already told us Captain McKenzie was made ATO (Animal Transport Officer) for the column in 1943 and soon became attached to his beloved mules. Pictured right, is a group of muleteers from 1943 congregating on the banks of one of the rivers that year, either re-grouping after a crossing or preparing to get their mules across.

Here is a quote from the book Canadians and the Burma Campaign, 1941-45, by Robert Farquharson which recounts the early moments of McKenzie's time behind enemy lines in Burma:

His first task was to get the mules over the River Chindwin. Mules are good swimmers once persuaded to enter the water. 'Mac' got his mules into the river, but on reaching midstream, they all suddenly turned and headed back to the shore they knew. Eventually, with patience, persistence and some little profanity, he got the mules across. Once all his charges, 80 mules and 20 horses were over, 'Mac' himself crossed elegantly astride his own charger.

Captain McKenzie adored his animals and became extremely attached to them during those few months in Burma. Although he could not bear to see the mules suffering as the privations of the expedition began to hit home, he was unable to put the creatures out of their misery himself and often passed this sad duty on to his fellow officers. Denis Gudgeon told me during our discussions that:

He (McKenzie) simply loved his mules and could never shoot a sick animal, even when he knew it was the right thing to do, it was heartbreaking to see 'Mac' march away, head bowed, after he had lost one of his mules.

Roy McKenzie's love for animals was not restricted to the column's mules and horses. From the pages of Mike Calvert's book, Prisoners of Hope, comes this short excerpt describing an incident with an elephant during the outward crossing of the Chindwin River in February 1943:

I remember one column had an interesting experience with an elephant when they were trying to cross the Chindwin River. Eventually they chose as as their crossing place a point where a sandy spit stretched out three-quarters of the way across the river. For the rest of the journey the elephant and its mahout, carrying the column wireless and battery charger, swam casually across to the other side. This gave the column commander and idea. He was having great difficulty in getting his men and stores across, owing to the swift current and the inadequacies of the boats at his disposal.

So he recalled the elephant, loaded it up and it swam over again. This occurred two or three times more with ever increasing loads, until eventually, as the elephant stepped off into the deep water, he missed his footing and capsized. He floated downstream, the load acting as a keel, with his four legs and trunk waving idly in the air. Thankfully he could still breathe as long as he kept his mouth shut.

A Canadian officer, with great presence of mind, ran downstream, plunged into the water, sat on the creatures belly and with the elephant behaving correctly the whole time, cut the girth strap. The elephant then righted himself, spurted one long jet of water through his trunk and made quietly for the shore, where he awaited his mahout. As McKenzie, the Canadian officer passed by, the elephant gave him a wink and that was his only apparent sign of emotion.

Mac was a lovely genuine man who always considered the junior officers viewpoint and ideas, even if he rarely acted upon them.

As Jack has already told us Captain McKenzie was made ATO (Animal Transport Officer) for the column in 1943 and soon became attached to his beloved mules. Pictured right, is a group of muleteers from 1943 congregating on the banks of one of the rivers that year, either re-grouping after a crossing or preparing to get their mules across.

Here is a quote from the book Canadians and the Burma Campaign, 1941-45, by Robert Farquharson which recounts the early moments of McKenzie's time behind enemy lines in Burma:

His first task was to get the mules over the River Chindwin. Mules are good swimmers once persuaded to enter the water. 'Mac' got his mules into the river, but on reaching midstream, they all suddenly turned and headed back to the shore they knew. Eventually, with patience, persistence and some little profanity, he got the mules across. Once all his charges, 80 mules and 20 horses were over, 'Mac' himself crossed elegantly astride his own charger.

Captain McKenzie adored his animals and became extremely attached to them during those few months in Burma. Although he could not bear to see the mules suffering as the privations of the expedition began to hit home, he was unable to put the creatures out of their misery himself and often passed this sad duty on to his fellow officers. Denis Gudgeon told me during our discussions that:

He (McKenzie) simply loved his mules and could never shoot a sick animal, even when he knew it was the right thing to do, it was heartbreaking to see 'Mac' march away, head bowed, after he had lost one of his mules.

Roy McKenzie's love for animals was not restricted to the column's mules and horses. From the pages of Mike Calvert's book, Prisoners of Hope, comes this short excerpt describing an incident with an elephant during the outward crossing of the Chindwin River in February 1943:

I remember one column had an interesting experience with an elephant when they were trying to cross the Chindwin River. Eventually they chose as as their crossing place a point where a sandy spit stretched out three-quarters of the way across the river. For the rest of the journey the elephant and its mahout, carrying the column wireless and battery charger, swam casually across to the other side. This gave the column commander and idea. He was having great difficulty in getting his men and stores across, owing to the swift current and the inadequacies of the boats at his disposal.

So he recalled the elephant, loaded it up and it swam over again. This occurred two or three times more with ever increasing loads, until eventually, as the elephant stepped off into the deep water, he missed his footing and capsized. He floated downstream, the load acting as a keel, with his four legs and trunk waving idly in the air. Thankfully he could still breathe as long as he kept his mouth shut.

A Canadian officer, with great presence of mind, ran downstream, plunged into the water, sat on the creatures belly and with the elephant behaving correctly the whole time, cut the girth strap. The elephant then righted himself, spurted one long jet of water through his trunk and made quietly for the shore, where he awaited his mahout. As McKenzie, the Canadian officer passed by, the elephant gave him a wink and that was his only apparent sign of emotion.

The photograph seen above shows one of the techniques employed by Chindit ATO's during the operations of 1943 and 1944. In this case tethering lead mules to small country boats and towing them across the rivers, often in the hope that other non-tethered mules would then follow them over. One ATO ordered the column bugler over the river and then to sound the 'feeding' bugle call from the opposite bank, this resulted in a stampede, as the mules raced in to the water hoping for a good meal once they reached the other side.

The main objective for Column 3 in 1943 was to demolish the railway at a place called Nankan. As Calvert and the column closed in one their target, it was decided that all roads and tracks into the village should be guarded in order to prevent any enemy interference during the demolitions. McKenzie was given the task to secure the western end of these tracks and lay an ambush for any Japanese which appeared on the scene. Captain McKenzie instructed Lieutenant D. Gudgeon to take his precious mules away from the area of the ambush and to stay with them until the days business was over.

Out of the blue two lorry loads of Japanese soldiers arrived and a firefight took place, between McKenzie at one end of the road and Subedar Kum Sing Gurung at the other, the enemy troops were soon dealt with. You can read the IDSM citation for Subedar Kum Sing as awarded for his efforts at Nankan, here: Second citation on the page.

As the columns work at Nankan was now completed the order was given to proceed to the next rendezvous point, as the main sections of Calvert's party marched away, Roy McKenzie was given the job of rearguard. He remained in the location for the remainder of the evening and did not catch up with the main group again until the next day. It is possible that the family's recollection of him receiving the Military Cross, could be from his actions during this period of Operation Longcloth?

Denis Gudgeon also told me that:

After the demolitions at Nankan, we marched off in an easterly direction and it was rumoured that we might be heading for the Gokthiek viaduct. This would have taken us many miles deeper into occupied territory and food was becoming an issue. 'Mac' often shared his rations with other men, especially if they had begun to look rough, which some of us had by then.

On March 29th the order was given for the Chindits to return home to India. Major Calvert sat all his officers down around the camp fire and explained how he proposed to achieve this. In his heart of hearts he dearly wanted to march his entire column of men back across the Chindwin River as one unit, but he realised the logistical difficulties of this plan and broke the column up into nine dispersal groups. Once again he called upon Captain McKenzie to lead one of these parties, giving 'Mac' and another officer, Lieutenant George Worte the responsibility of guiding the Gurkha muleteers back to India and safety. Calvert issued each group with maps and compasses, as much food as the men still possessed and an amount of silver rupees in case they needed to employ the help of local Burmese villagers on their journey out.

Once again Denis Gudgeon told me that:

When I eventually got home from my time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon, I was told that 'Mac' had got back safely across the Chindwin, taking about twenty days to complete the journey. He then went off to Srinagar in Kashmir to recuperate from his time in Burma and duly spent all the rupees he still had left from the bag given to him by Mike Calvert at dispersal. Nobody seemed to mind his cheek or his love of a good drink.

I would suggest a good drink was the very least those returning Chindits deserved after their time in Burma during the early months of 1943.

Captain McKenzie did succeed in getting the majority of his men back to India, however, they did suffer casualties whilst re-crossing the Irrawaddy River when the rafts they had made were fired upon by Japanese mortars and light machine guns. In fact this enemy fire resulted in MacKenzie having to abandon the raft he occupied and swim the rest of the way across.

As you can clearly see, Operation Longcloth for many of the participants will always be about those wide and dangerous Burmese rivers. For some men they would prove insurmountable obstacles, for others much like Roy McKenzie simply another giant hurdle on the long journey home.

Roy was present at one failed attempt to cross the River Shweli in early April 1943. From the witness report given by Rfm. Tek Bahadur Rai, also of Column 3, comes this information:

After breaking up into our new dispersal groups I remained with Major Calvert. We went to collect some supplies that we had hidden in the jungle some weeks earlier. We then moved off toward the Shweli. Here we bumped into Major Conron who was attempting to find suitable boats to get across. He had been in the vicinity for a few days.

In fact Major Conron had led his own group of Gurkha soldiers away from Wingate's Head Quarters Brigade when the dispersal order had been given in late March.

Tek Bahadur remembers:

A gathering of officers from Column 3 were on the river bank, including Subedar Kumbasing Gurung, Lts. Gourlie and Gibson and Capt. McKenzie. Major Conron finally obtained seven boats for the men and he, along with some of his Gurkha Riflemen set out in the first boat. Half way across I saw the Burmese boatman purposely overturn the boat and then swim away, some of our men swam to the other side of the river, but Major Conron and Rifleman Gyalbosing Tamang were lost. After seeing this treachery on the part of the boatman, we decided to quickly move away into the nearby jungle.

From the large group mentioned above, many failed to return to India and simply disappeared, while others had to endure over two years in Japanese hands.

Pictured below is a photograph of the lead mule and his handler from a Chindit column in 1943, as has been mentioned before, the bond between man and beast became very strong during those tough and testing weeks behind enemy lines.

The main objective for Column 3 in 1943 was to demolish the railway at a place called Nankan. As Calvert and the column closed in one their target, it was decided that all roads and tracks into the village should be guarded in order to prevent any enemy interference during the demolitions. McKenzie was given the task to secure the western end of these tracks and lay an ambush for any Japanese which appeared on the scene. Captain McKenzie instructed Lieutenant D. Gudgeon to take his precious mules away from the area of the ambush and to stay with them until the days business was over.

Out of the blue two lorry loads of Japanese soldiers arrived and a firefight took place, between McKenzie at one end of the road and Subedar Kum Sing Gurung at the other, the enemy troops were soon dealt with. You can read the IDSM citation for Subedar Kum Sing as awarded for his efforts at Nankan, here: Second citation on the page.

As the columns work at Nankan was now completed the order was given to proceed to the next rendezvous point, as the main sections of Calvert's party marched away, Roy McKenzie was given the job of rearguard. He remained in the location for the remainder of the evening and did not catch up with the main group again until the next day. It is possible that the family's recollection of him receiving the Military Cross, could be from his actions during this period of Operation Longcloth?

Denis Gudgeon also told me that:

After the demolitions at Nankan, we marched off in an easterly direction and it was rumoured that we might be heading for the Gokthiek viaduct. This would have taken us many miles deeper into occupied territory and food was becoming an issue. 'Mac' often shared his rations with other men, especially if they had begun to look rough, which some of us had by then.

On March 29th the order was given for the Chindits to return home to India. Major Calvert sat all his officers down around the camp fire and explained how he proposed to achieve this. In his heart of hearts he dearly wanted to march his entire column of men back across the Chindwin River as one unit, but he realised the logistical difficulties of this plan and broke the column up into nine dispersal groups. Once again he called upon Captain McKenzie to lead one of these parties, giving 'Mac' and another officer, Lieutenant George Worte the responsibility of guiding the Gurkha muleteers back to India and safety. Calvert issued each group with maps and compasses, as much food as the men still possessed and an amount of silver rupees in case they needed to employ the help of local Burmese villagers on their journey out.

Once again Denis Gudgeon told me that:

When I eventually got home from my time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon, I was told that 'Mac' had got back safely across the Chindwin, taking about twenty days to complete the journey. He then went off to Srinagar in Kashmir to recuperate from his time in Burma and duly spent all the rupees he still had left from the bag given to him by Mike Calvert at dispersal. Nobody seemed to mind his cheek or his love of a good drink.

I would suggest a good drink was the very least those returning Chindits deserved after their time in Burma during the early months of 1943.

Captain McKenzie did succeed in getting the majority of his men back to India, however, they did suffer casualties whilst re-crossing the Irrawaddy River when the rafts they had made were fired upon by Japanese mortars and light machine guns. In fact this enemy fire resulted in MacKenzie having to abandon the raft he occupied and swim the rest of the way across.

As you can clearly see, Operation Longcloth for many of the participants will always be about those wide and dangerous Burmese rivers. For some men they would prove insurmountable obstacles, for others much like Roy McKenzie simply another giant hurdle on the long journey home.

Roy was present at one failed attempt to cross the River Shweli in early April 1943. From the witness report given by Rfm. Tek Bahadur Rai, also of Column 3, comes this information:

After breaking up into our new dispersal groups I remained with Major Calvert. We went to collect some supplies that we had hidden in the jungle some weeks earlier. We then moved off toward the Shweli. Here we bumped into Major Conron who was attempting to find suitable boats to get across. He had been in the vicinity for a few days.

In fact Major Conron had led his own group of Gurkha soldiers away from Wingate's Head Quarters Brigade when the dispersal order had been given in late March.

Tek Bahadur remembers:

A gathering of officers from Column 3 were on the river bank, including Subedar Kumbasing Gurung, Lts. Gourlie and Gibson and Capt. McKenzie. Major Conron finally obtained seven boats for the men and he, along with some of his Gurkha Riflemen set out in the first boat. Half way across I saw the Burmese boatman purposely overturn the boat and then swim away, some of our men swam to the other side of the river, but Major Conron and Rifleman Gyalbosing Tamang were lost. After seeing this treachery on the part of the boatman, we decided to quickly move away into the nearby jungle.

From the large group mentioned above, many failed to return to India and simply disappeared, while others had to endure over two years in Japanese hands.

Pictured below is a photograph of the lead mule and his handler from a Chindit column in 1943, as has been mentioned before, the bond between man and beast became very strong during those tough and testing weeks behind enemy lines.

The last section of this story is a paraphrased transcript of a newspaper article from May 1943, taken from the pages of a local periodical from Roy McKenzie's home city of Ontario. It was one of many articles written about the first Chindit operation, which was used heavily in terms of propaganda and boosting morale, for the success starved British and colonial public of the day.

'Ontario Captain Among Mule Eating Warriors, in 90 day Jungle Saga'

New Delhi, May 21st 1943. Eight columns of British and Native troops, with a few Canadian and Australian volunteers and a supply column of 1000 mules, moved into Burma three months ago to smash at Japanese communications. This week the survivors fought their way back out of the jungle, with stories of chaos created among the Japs. They travelled as much as 1000 miles, wrecked railways and bridges, and tied up many more than their own number of Japanese.

Rivalling the exploits of Lawrence of Arabia, the force was led by Brigadier Charles Orde Wingate (39), kin to the legendary T. E. Lawrence. Burmese, Gurkhas and Indian troops were included, along with a regiment of city-bred Britons. The nucleus consisted of veterans from the commando raid in the Lofoten Islands off Norway. Included in this force according to Reuters news agency were several Australian and Canadian volunteers, one being identified as Captain Roy McKenzie, of Windsor, Ontario. The Captain said that he had helped blow up a railway line and had once been swept nearly 2 miles down the Irrawaddy River.

Certain columns penetrated almost 200 miles into Burma and put out of action the railway line that ran from Mandalay, through Katha to Myitkhina. Demolition charges destroyed the railway in over 75 places, and rendered further operation of this vital line of communication impossible for many months. A Bombay dispatch said that the three month operation had revealed the future pattern of Allied operations within Burma, including the use of wireless to guide in bombers and supplying forces by plane. It is believed that the operation is a precursor to larger incursions into Burma in an attempt to re-open the Burma Road.

Preston Grover (Associated Press) witnessed the first of these hardened veterans to return home to India after their march from the far shores of the Irrawaddy River. The operation itself had been kept top secret from the outside world for nearly 12 weeks. Grover said that before Wingate's fighters returned to India they had eaten their mules and learned to live off tender bamboo shoots and banana leaves. Men had also tasted snake meat and caught fish with their mosquito nets. Their only communication was by radio, calling in supplies from the RAF, who then dropped in food, spectacles, letters and even some tins of snuff for the kilted Lieutenant Jeffrey Lockett, whose Gurkha troops mistook this to be curry powder and used it in their cooking pots of rice.

The success of the raid had been seven-fold:

Blowing up 100 miles of vital railway line and several bridges.

Delaying the Japanese move toward the Chindwin border with Assam.

Relieved Japanese pressure on the beleaguered Chinese forces to the north.

They helped save an encircled force of pro-British Burmese natives.

They undermined the enemies hitherto sense of security inside Burma.

Gave British troops invaluable experience in jungle warfare.

Proved that a well prepared British soldier is the equal of his Japanese counterpart, and proved Wingate's theories of Long Range Penetration and supply from the air.

Although conditions were extremely harsh for the men, there had been some moments of humour on the expedition. Lieutenant G. C. Bruce from Glasgow told how he took control of Tagaung with only four men. He recounted:

We walked into town and met around 30 Burmese who were fighting on the Japanese side. I told them they were foolish to fight for the Japanese and pointed to the sky and said I would call in bombers to destroy them if they continued to resist. Just then 12 of our bombers came roaring overhead, they did not know I was below them and I didn't know they were coming, but it was enough for the Burmese to throw down their weapons and plead for mercy.

Lt. Bruce and his platoon then blocked river traffic on the Irrawaddy for over five days which caused great embarrassment for the bemused and by now panicking Japanese. As the enemy hunted for the Chindits, they began to wonder if the British presence in the area might be the beginning of the Allied re-invasion of Burma. As a result, the Japanese Generals strengthened their numbers in that region, which curtailed any offensive plans they had developed for themselves.

Update 23/08/2012.

Well I'm happy to say serendipity did play her part with this story afterall and Captain McKenzie's nephew Jack contacted me this August. Here is what he had to say:

Dear Steve,

I just discovered this webpage and am absolutely delighted to do so. You will understand why of course. I am now a 74 year old (this very day) ex-member of the Royal Canadian Navy, having been a helicopter pilot and having left in 1964 after 8 years of service, as a Lieutenant. My mother has of course passed, as I expect my uncles have, although I have had no information about them in recent years. I am very glad to hear more about Uncle Roy. What a birthday present!

'Ontario Captain Among Mule Eating Warriors, in 90 day Jungle Saga'

New Delhi, May 21st 1943. Eight columns of British and Native troops, with a few Canadian and Australian volunteers and a supply column of 1000 mules, moved into Burma three months ago to smash at Japanese communications. This week the survivors fought their way back out of the jungle, with stories of chaos created among the Japs. They travelled as much as 1000 miles, wrecked railways and bridges, and tied up many more than their own number of Japanese.

Rivalling the exploits of Lawrence of Arabia, the force was led by Brigadier Charles Orde Wingate (39), kin to the legendary T. E. Lawrence. Burmese, Gurkhas and Indian troops were included, along with a regiment of city-bred Britons. The nucleus consisted of veterans from the commando raid in the Lofoten Islands off Norway. Included in this force according to Reuters news agency were several Australian and Canadian volunteers, one being identified as Captain Roy McKenzie, of Windsor, Ontario. The Captain said that he had helped blow up a railway line and had once been swept nearly 2 miles down the Irrawaddy River.

Certain columns penetrated almost 200 miles into Burma and put out of action the railway line that ran from Mandalay, through Katha to Myitkhina. Demolition charges destroyed the railway in over 75 places, and rendered further operation of this vital line of communication impossible for many months. A Bombay dispatch said that the three month operation had revealed the future pattern of Allied operations within Burma, including the use of wireless to guide in bombers and supplying forces by plane. It is believed that the operation is a precursor to larger incursions into Burma in an attempt to re-open the Burma Road.

Preston Grover (Associated Press) witnessed the first of these hardened veterans to return home to India after their march from the far shores of the Irrawaddy River. The operation itself had been kept top secret from the outside world for nearly 12 weeks. Grover said that before Wingate's fighters returned to India they had eaten their mules and learned to live off tender bamboo shoots and banana leaves. Men had also tasted snake meat and caught fish with their mosquito nets. Their only communication was by radio, calling in supplies from the RAF, who then dropped in food, spectacles, letters and even some tins of snuff for the kilted Lieutenant Jeffrey Lockett, whose Gurkha troops mistook this to be curry powder and used it in their cooking pots of rice.

The success of the raid had been seven-fold:

Blowing up 100 miles of vital railway line and several bridges.

Delaying the Japanese move toward the Chindwin border with Assam.

Relieved Japanese pressure on the beleaguered Chinese forces to the north.

They helped save an encircled force of pro-British Burmese natives.

They undermined the enemies hitherto sense of security inside Burma.

Gave British troops invaluable experience in jungle warfare.

Proved that a well prepared British soldier is the equal of his Japanese counterpart, and proved Wingate's theories of Long Range Penetration and supply from the air.

Although conditions were extremely harsh for the men, there had been some moments of humour on the expedition. Lieutenant G. C. Bruce from Glasgow told how he took control of Tagaung with only four men. He recounted:

We walked into town and met around 30 Burmese who were fighting on the Japanese side. I told them they were foolish to fight for the Japanese and pointed to the sky and said I would call in bombers to destroy them if they continued to resist. Just then 12 of our bombers came roaring overhead, they did not know I was below them and I didn't know they were coming, but it was enough for the Burmese to throw down their weapons and plead for mercy.

Lt. Bruce and his platoon then blocked river traffic on the Irrawaddy for over five days which caused great embarrassment for the bemused and by now panicking Japanese. As the enemy hunted for the Chindits, they began to wonder if the British presence in the area might be the beginning of the Allied re-invasion of Burma. As a result, the Japanese Generals strengthened their numbers in that region, which curtailed any offensive plans they had developed for themselves.

Update 23/08/2012.

Well I'm happy to say serendipity did play her part with this story afterall and Captain McKenzie's nephew Jack contacted me this August. Here is what he had to say:

Dear Steve,

I just discovered this webpage and am absolutely delighted to do so. You will understand why of course. I am now a 74 year old (this very day) ex-member of the Royal Canadian Navy, having been a helicopter pilot and having left in 1964 after 8 years of service, as a Lieutenant. My mother has of course passed, as I expect my uncles have, although I have had no information about them in recent years. I am very glad to hear more about Uncle Roy. What a birthday present!

James Charles Bruce MC. Photographed after the 2nd Chindit expedition in 1944.

James Charles Bruce MC. Photographed after the 2nd Chindit expedition in 1944.

Update 12/11/2013.

Recently I received an email contact from the son of a Burma Rifles Officer who had served on Operation Longcloth. Robert Bruce told me that:

In the Roy McKenzie section of your website the chap referred to as GC Bruce is actually my father, J C (Charlie) Bruce. And the story mentioned above is told at much greater length in a footnote at the back of Bernard Fergusson's book Beyond the Chindwin.

Here is a transcription of that footnote from Fergusson's book:

The adventures of Captain George Carne and Lieutenant Charles Bruce, both of the Burma Rifles attached to No. I Group, are worth recording. Charlie Bruce had been sent on ahead, before No. 2 Column got into trouble, to seize a village on the Irrawaddy, and capture all its boats. He occupied the village with six Burma Riflemen, and held it for some days before he heard from local gossip what had happened to No. 2 Column.

NB: Column 2 had been ambushed at the railway town of Kyaikthin on 2nd March and had suffered heavy casualties. The commanding officer, Major Arthur Emmett then called dispersal and took most of his remaining men back to India. A group of approximately 100 soldiers from Column 2 did not receive this order and continued eastward toward the Irrawaddy. This group eventually joined up with Column 1 under the command of Major George Dunlop.

Fergusson continues:

During his stay in the village, he (Lieut. Bruce) disarmed the local police, who had been armed by the Japs; sank with tommy-gun fire a boatload of Japs, whom he dispatched; and made a remarkable propaganda speech. He had just said, "I can call great Air Forces from India at will," and thrown his arm in the air with an extravagant gesture, when he suddenly heard, far away behind him in the west, the droning of air-craft. He remained with his arm in the air, like Moses when he was dealing with the Amalekites; and six British bombers flew slowly over his head, in the direction of Mandalay. "What did I tell you", said Charlie, recovering himself.

From then on he was a made man. Hearing at last that his column had been ambushed he joined up with Captain Carne. They crossed the Irrawaddy; it was they who occupied the Rest House at Yingwin when 5 Column was at Pegon. After many exciting adventures, they arrived, in India, early in April. Both received the Military Cross.

NB: Captain George Power Carne served with the 2nd Burma Rifles during Operation Longcloth. Attached to Column 2 in 1943 he led the Guerrilla Platoon up until the disaster at Kyaikthin. After the war he settled in West Cornwall. George Carne passed away in 1988. To read more about Lt. Bruce, please click on the following link: Lt. James Charles Bruce

Recently I received an email contact from the son of a Burma Rifles Officer who had served on Operation Longcloth. Robert Bruce told me that:

In the Roy McKenzie section of your website the chap referred to as GC Bruce is actually my father, J C (Charlie) Bruce. And the story mentioned above is told at much greater length in a footnote at the back of Bernard Fergusson's book Beyond the Chindwin.

Here is a transcription of that footnote from Fergusson's book:

The adventures of Captain George Carne and Lieutenant Charles Bruce, both of the Burma Rifles attached to No. I Group, are worth recording. Charlie Bruce had been sent on ahead, before No. 2 Column got into trouble, to seize a village on the Irrawaddy, and capture all its boats. He occupied the village with six Burma Riflemen, and held it for some days before he heard from local gossip what had happened to No. 2 Column.

NB: Column 2 had been ambushed at the railway town of Kyaikthin on 2nd March and had suffered heavy casualties. The commanding officer, Major Arthur Emmett then called dispersal and took most of his remaining men back to India. A group of approximately 100 soldiers from Column 2 did not receive this order and continued eastward toward the Irrawaddy. This group eventually joined up with Column 1 under the command of Major George Dunlop.

Fergusson continues:

During his stay in the village, he (Lieut. Bruce) disarmed the local police, who had been armed by the Japs; sank with tommy-gun fire a boatload of Japs, whom he dispatched; and made a remarkable propaganda speech. He had just said, "I can call great Air Forces from India at will," and thrown his arm in the air with an extravagant gesture, when he suddenly heard, far away behind him in the west, the droning of air-craft. He remained with his arm in the air, like Moses when he was dealing with the Amalekites; and six British bombers flew slowly over his head, in the direction of Mandalay. "What did I tell you", said Charlie, recovering himself.

From then on he was a made man. Hearing at last that his column had been ambushed he joined up with Captain Carne. They crossed the Irrawaddy; it was they who occupied the Rest House at Yingwin when 5 Column was at Pegon. After many exciting adventures, they arrived, in India, early in April. Both received the Military Cross.

NB: Captain George Power Carne served with the 2nd Burma Rifles during Operation Longcloth. Attached to Column 2 in 1943 he led the Guerrilla Platoon up until the disaster at Kyaikthin. After the war he settled in West Cornwall. George Carne passed away in 1988. To read more about Lt. Bruce, please click on the following link: Lt. James Charles Bruce

Major Dominic Neill in 1956.

Major Dominic Neill in 1956.

Update 12/01/2017.

From the memoirs of Colonel Dominic Fitzgerald Neill of the 2nd Gurkha Regiment:

After Operation Longcloth, when I got back to the Regimental Centre at Dehra Dun, I found that Mac McKenzie was the only member of the Third Battalion still at the station; everyone else had gone on leave. There was no information available about any of my men who had been separated from me during the ambush at Thayetta on the 14th April. I was told that they might well have arrived already and could now be on on leave in Nepal. I found out that I had been posted missing, but, fortunately, my mother had not yet been so advised.

One evening in the mess, Mac suggested to me that I should accompany him on leave to Srinagar in Kashmir, where he had already booked a houseboat through an agent. I gladly accepted his offer. That same evening, whilst we were exchanging stories of our experiences on the expedition, I said to Mac that, in my opinion, never had so many marched so far for so little. He laughed and said that he agreed with me.

Once my men had left Dehra Dun to return to their villages for 6 weeks recuperation leave, Mac and I set off for Srinagar, I still possessed those remaining silver rupees which I'd carried in the basic pouch on my belt all the way from the far side of the Irrawaddy and which, together with my tommy-gun magazines, had caused those deep, suppurating sores on my hips. I didn't think that the King would mind my doing so and, on the assumption that I had his blessing, Mac and I drank his health every day and night in Kashmir until the very last silver coin had been spent! I started the first of over twenty bouts of malaria whilst we were in Srinagar. These were to last for the next few months until just before the Third Battalion left Dehra for the jungles of southern India to join 25 Indian Division, prior to taking part in the final Arakan Campaign of 1944 and 1945. But that is another story.

Mac McKenzie did not come with us to the Arakan, he left us in early 1944 to join the I.E.M.E., taking a senior roll within their Animal Transport Company. I heard later, that after the war he returned home to his native Canada, however, he then decided to enlist into the United States Army and fought during the Korean War as a Sergeant.

To read more about Dominic Neill and his experiences on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link:

Lt. Dominic Neill and his Gurkha Muleteers

From the memoirs of Colonel Dominic Fitzgerald Neill of the 2nd Gurkha Regiment:

After Operation Longcloth, when I got back to the Regimental Centre at Dehra Dun, I found that Mac McKenzie was the only member of the Third Battalion still at the station; everyone else had gone on leave. There was no information available about any of my men who had been separated from me during the ambush at Thayetta on the 14th April. I was told that they might well have arrived already and could now be on on leave in Nepal. I found out that I had been posted missing, but, fortunately, my mother had not yet been so advised.

One evening in the mess, Mac suggested to me that I should accompany him on leave to Srinagar in Kashmir, where he had already booked a houseboat through an agent. I gladly accepted his offer. That same evening, whilst we were exchanging stories of our experiences on the expedition, I said to Mac that, in my opinion, never had so many marched so far for so little. He laughed and said that he agreed with me.

Once my men had left Dehra Dun to return to their villages for 6 weeks recuperation leave, Mac and I set off for Srinagar, I still possessed those remaining silver rupees which I'd carried in the basic pouch on my belt all the way from the far side of the Irrawaddy and which, together with my tommy-gun magazines, had caused those deep, suppurating sores on my hips. I didn't think that the King would mind my doing so and, on the assumption that I had his blessing, Mac and I drank his health every day and night in Kashmir until the very last silver coin had been spent! I started the first of over twenty bouts of malaria whilst we were in Srinagar. These were to last for the next few months until just before the Third Battalion left Dehra for the jungles of southern India to join 25 Indian Division, prior to taking part in the final Arakan Campaign of 1944 and 1945. But that is another story.

Mac McKenzie did not come with us to the Arakan, he left us in early 1944 to join the I.E.M.E., taking a senior roll within their Animal Transport Company. I heard later, that after the war he returned home to his native Canada, however, he then decided to enlist into the United States Army and fought during the Korean War as a Sergeant.

To read more about Dominic Neill and his experiences on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link:

Lt. Dominic Neill and his Gurkha Muleteers

Update 21/02/2021.

Lt. George K. Worte

George was the assistant Animal Transport Officer in No. 3 Column. He and I had been given the job of taking care of the Bombay-Burma Teak Company’s elephants which Brigadier Wingate had managed to purloin for our use in Burma. George was in his early twenties, tall and thin with a thick dark stubble on his face. He wore a khaki bush-shirt and slacks, boots with gaiters and over his closely cropped head a fawn-coloured balaclava. (from the book, Across the Threshold of Battle, by Lt. Harold James).

Lt. 174241 George Keniston Worte was commissioned from Sandhurst into the Regular Army on the 22nd February 1941. Later, he volunteered for a commission into the Indian Army and was posted to the third battalion of the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles, just in time for the first Wingate expedition.

He became the assistant Animal Transport Officer in No. 3 Column serving under Captain Roy McKenzie on Operation Longcloth. He remained with McKenzie and the mules during the entire expedition and dispersed with his Captain on the 28th March 1943, alongside their Gurkha muleteers and some other Indian members of the column. After taking three weeks to make the trip back to the Chindwin River, George Worte and the other successful returnees from No. 3 Column spent a period of recuperation at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station located on the outskirts of Imphal, and under the watchful eye of Matron Agnes McGearey.

After Operation Longcloth, George Worte remained with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and served with the battalion as part of the 25th Indian Infantry Division in the Arakan region of Burma. He later left the Army with the rank of Major.

Lt. George K. Worte

George was the assistant Animal Transport Officer in No. 3 Column. He and I had been given the job of taking care of the Bombay-Burma Teak Company’s elephants which Brigadier Wingate had managed to purloin for our use in Burma. George was in his early twenties, tall and thin with a thick dark stubble on his face. He wore a khaki bush-shirt and slacks, boots with gaiters and over his closely cropped head a fawn-coloured balaclava. (from the book, Across the Threshold of Battle, by Lt. Harold James).

Lt. 174241 George Keniston Worte was commissioned from Sandhurst into the Regular Army on the 22nd February 1941. Later, he volunteered for a commission into the Indian Army and was posted to the third battalion of the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles, just in time for the first Wingate expedition.

He became the assistant Animal Transport Officer in No. 3 Column serving under Captain Roy McKenzie on Operation Longcloth. He remained with McKenzie and the mules during the entire expedition and dispersed with his Captain on the 28th March 1943, alongside their Gurkha muleteers and some other Indian members of the column. After taking three weeks to make the trip back to the Chindwin River, George Worte and the other successful returnees from No. 3 Column spent a period of recuperation at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station located on the outskirts of Imphal, and under the watchful eye of Matron Agnes McGearey.

After Operation Longcloth, George Worte remained with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and served with the battalion as part of the 25th Indian Infantry Division in the Arakan region of Burma. He later left the Army with the rank of Major.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, Jack Oullette and stated contributors, April 2012.