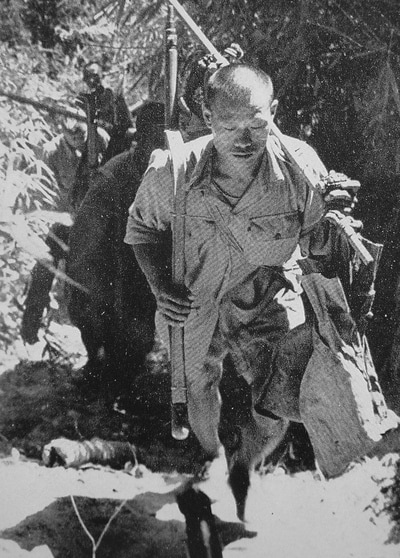

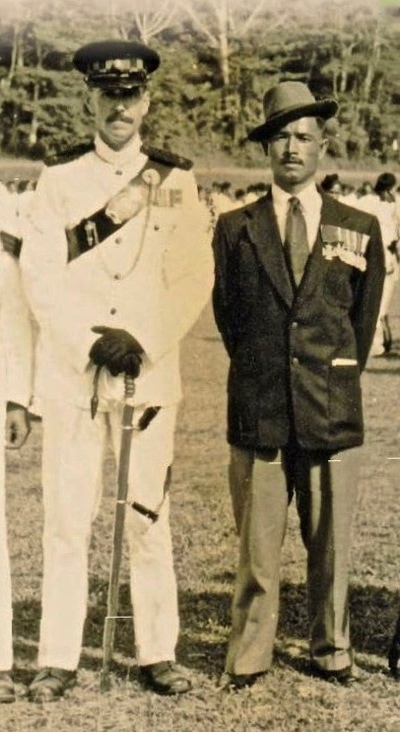

Lieutenant Dominic Neill and his Gurkha Muleteers.

Cap badge of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

Cap badge of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

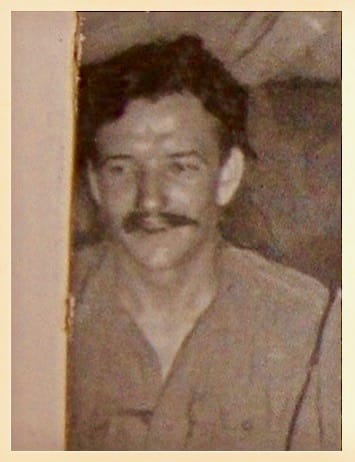

Nick Neill had commanded a company of 2nd Gurkhas in the vicious fighting against the Japanese in Burma during WW2 and again throughout the long Malayan Emergency. Fanatical Japanese and elusive Communist bandits had been his trainers in the very specialised skill of jungle warfare and he had remembered all their hard taught lessons. A man of few words and those spoken with great consideration and devastating directness, he was an imposing leader of men, a fine trainer and most importantly an ideal and inspiring commander.

(Brigadier Christopher Bullock, former commander, The Brigade of Gurkhas).

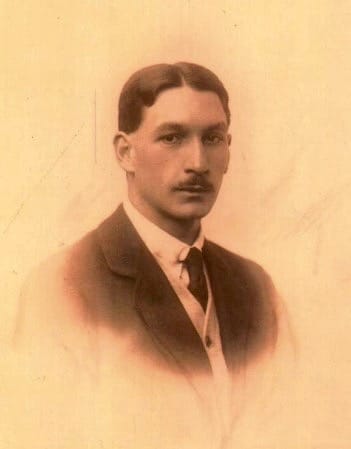

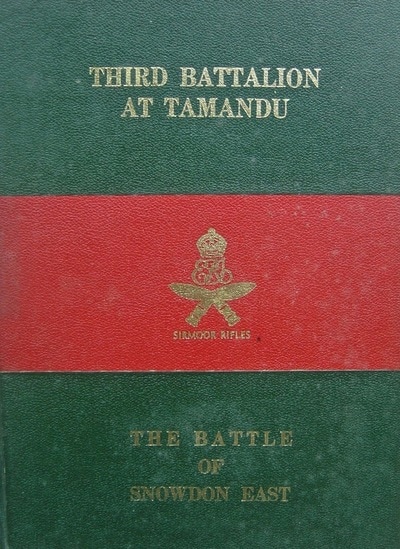

In December 1965, Lt-Colonel Dominic Fitzgerald Neill relinquished his command of the 2nd Battalion of the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles after some 25 years with the Regiment. During his time with the regiment, he had seen service on the first Wingate expedition in 1943, fought across the arduous terrain of the Arakan, then almost before taking breathe, was thrust into the complications of the Malayan Emergency. By the time of the Borneo Confrontation and his retirement, it is probably true to say, that he had become a legend in his own regimental lifetime.

However, 'Nick' Neill had not always felt so secure in his role with the Gurkhas. In early months of 1943, as the newly formed Chindit Brigade was moving through Assam on its way down to the Chindwin River, he recalled:

I was a 21 year old subaltern on the first Chindit expedition, inexperienced, inadequately trained and in command of 52 equally young and inexperienced Gurkha Riflemen.

Long after his military service had ended, Dominic Neill wrote down his experiences from the first Wingate expedition in a memoir entitled 'One More River.' This narrative can be accessed and read at the Gurkha Museum, located at the Peninsula Barracks, Romsey Road, Winchester. To listen to the oral histories left by Dominic at the Imperial War Museum in 1993, please access the following links:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80013020

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80013851

For the purposes of this story, and I am positive that Nick Neill would have approved, I am going to concentrate on the Gurkha soldiers he led as a young officer in 1943, rather than fully recounting his own military career. However, to begin with, let us learn more about the youthful, soon to be Chindit officer and how he became a member of the first Wingate operation in 1943.

Dominic Fitzgerald Neill was born on the 9th December 1921. He lived with his family in the North London suburb of Highgate and attended the City of London School up until 1939, when he first attempted to enlist into the British Army. His initial attempt, aged just seventeen, at the Army Recruitment office in Parliament Street, Westminster ended in failure, when he was turned away for being too young. He tried again shortly after reaching his eighteenth birthday, this time at the office on the Holloway Road and was accepted. On the 3rd June 1940, Dominic was posted to the 7th Battalion of the 60th Rifles, where he began his service as a Rifleman, quickly followed by a promotion to junior NCO. Several months later, he was offered the chance of a commission into the British Indian Army and was soon on a troopship heading for the sub-continent. After his Officer Training, which took place at the O.T.C. at Bangalore, Nick Neill was commissioned into the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles on the 20th November 1941.

In 1942, the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles were led by Lt-Colonel L.A. Alexander and on their journey from their original base at Dehra Dun to the newly formed Chindit training camp at Saugor, Nick Neill travelled with three companions; 2nd Lieutenants Bill Smyly, Alex Irving and John Fowler. All four soldiers were eventually chosen to become Animal Transport Officers within 77th Brigade and trained with their men and mules at Guna in the Central Provinces of India. Nick Neill remembered the training camp in his memoir:

Our mule lines were at a place called Guna; a beautiful little spot. In the centre of the camp was a small jheel or lake and surrounding this was a perimeter of hills covered in thin scrub jungle. The senior officer at Guna was Captain Roy MacKenzie, a Canadian with whom I would strike up a close friendship.

After completing their initial Animal Transport training, the four young officers received news of their column placements for the forthcoming operation behind enemy lines in Burma. Lt. Neill was heart-broken to learn that he would command the mule transport section in 8 Column, which was made up almost entirely from men of the 13th King's. He was deeply saddened by the news, having wanted so dearly to be part of one of the Gurkha columns that made up 77th Brigade. Towards the end of the training period in November 1942, the final Gurkha recruits arrived at Guna and were amalgamated into the various Mule Transport Sections. Lt. Neill recalled:

We received some further reinforcements from the 10th Gurkha Regiment who were trained as second-line recruits for the three King's columns; so I was to command Gurkhas after all. Some days later, many other Gurkhas arrived at Guna from most of the other Regiments from the Gurkha Brigade. I was concerned that this mixture would not work well as a unit within 8 Column and was surprised that Brigadier Wingate could accept such an arrangement. In the end I had command of 53 Gurkha soldiers from the 4th, 5th, 6th and 10th Regiments.

My Jemadar was not a good officer and we soon parted company. There were three pre-war NCO's; 15484 Havildar Purkadhoj Limbu, 15715 Naik Budhiman Limbu and a young, very fierce looking Lance Naik who had enlisted just before the war, 2175 Harkabahadur Limbu. All my Riflemen were babies, who had only just completed their recruit training at their Regimental Centres. Soon our mules and chargers arrived and we went off to collect them from Lalitpur Railway Station. Most of us had never handled a mule before and some mistakes were made in those early weeks, but in the end we grew to love them dearly.

Two other Gurkha Riflemen that formed part of Lt. Neill's Transport section, were his Orderly Shamsherbahadur Thapa, a rather solemn young man, who seldom smiled and who had obviously been reluctant to leave his original Gurkha unit in order to join 77th Brigade. The other soldier was 107394 Rifleman Prembahadur Rai of the 10th Gurkha Regiment, who was able to soothe his mules during the long marches through the Burmese jungles by playing to them on his bamboo flute. Sadly, although Prembahadur Rai did survive his time on Operation Longcloth, he was killed in action at the battle of Meiktila on the 13th March 1945, as the 14th Army began to expel the Japanese from Burma.

Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this first section of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

(Brigadier Christopher Bullock, former commander, The Brigade of Gurkhas).

In December 1965, Lt-Colonel Dominic Fitzgerald Neill relinquished his command of the 2nd Battalion of the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles after some 25 years with the Regiment. During his time with the regiment, he had seen service on the first Wingate expedition in 1943, fought across the arduous terrain of the Arakan, then almost before taking breathe, was thrust into the complications of the Malayan Emergency. By the time of the Borneo Confrontation and his retirement, it is probably true to say, that he had become a legend in his own regimental lifetime.

However, 'Nick' Neill had not always felt so secure in his role with the Gurkhas. In early months of 1943, as the newly formed Chindit Brigade was moving through Assam on its way down to the Chindwin River, he recalled:

I was a 21 year old subaltern on the first Chindit expedition, inexperienced, inadequately trained and in command of 52 equally young and inexperienced Gurkha Riflemen.

Long after his military service had ended, Dominic Neill wrote down his experiences from the first Wingate expedition in a memoir entitled 'One More River.' This narrative can be accessed and read at the Gurkha Museum, located at the Peninsula Barracks, Romsey Road, Winchester. To listen to the oral histories left by Dominic at the Imperial War Museum in 1993, please access the following links:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80013020

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80013851

For the purposes of this story, and I am positive that Nick Neill would have approved, I am going to concentrate on the Gurkha soldiers he led as a young officer in 1943, rather than fully recounting his own military career. However, to begin with, let us learn more about the youthful, soon to be Chindit officer and how he became a member of the first Wingate operation in 1943.

Dominic Fitzgerald Neill was born on the 9th December 1921. He lived with his family in the North London suburb of Highgate and attended the City of London School up until 1939, when he first attempted to enlist into the British Army. His initial attempt, aged just seventeen, at the Army Recruitment office in Parliament Street, Westminster ended in failure, when he was turned away for being too young. He tried again shortly after reaching his eighteenth birthday, this time at the office on the Holloway Road and was accepted. On the 3rd June 1940, Dominic was posted to the 7th Battalion of the 60th Rifles, where he began his service as a Rifleman, quickly followed by a promotion to junior NCO. Several months later, he was offered the chance of a commission into the British Indian Army and was soon on a troopship heading for the sub-continent. After his Officer Training, which took place at the O.T.C. at Bangalore, Nick Neill was commissioned into the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles on the 20th November 1941.

In 1942, the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles were led by Lt-Colonel L.A. Alexander and on their journey from their original base at Dehra Dun to the newly formed Chindit training camp at Saugor, Nick Neill travelled with three companions; 2nd Lieutenants Bill Smyly, Alex Irving and John Fowler. All four soldiers were eventually chosen to become Animal Transport Officers within 77th Brigade and trained with their men and mules at Guna in the Central Provinces of India. Nick Neill remembered the training camp in his memoir:

Our mule lines were at a place called Guna; a beautiful little spot. In the centre of the camp was a small jheel or lake and surrounding this was a perimeter of hills covered in thin scrub jungle. The senior officer at Guna was Captain Roy MacKenzie, a Canadian with whom I would strike up a close friendship.

After completing their initial Animal Transport training, the four young officers received news of their column placements for the forthcoming operation behind enemy lines in Burma. Lt. Neill was heart-broken to learn that he would command the mule transport section in 8 Column, which was made up almost entirely from men of the 13th King's. He was deeply saddened by the news, having wanted so dearly to be part of one of the Gurkha columns that made up 77th Brigade. Towards the end of the training period in November 1942, the final Gurkha recruits arrived at Guna and were amalgamated into the various Mule Transport Sections. Lt. Neill recalled:

We received some further reinforcements from the 10th Gurkha Regiment who were trained as second-line recruits for the three King's columns; so I was to command Gurkhas after all. Some days later, many other Gurkhas arrived at Guna from most of the other Regiments from the Gurkha Brigade. I was concerned that this mixture would not work well as a unit within 8 Column and was surprised that Brigadier Wingate could accept such an arrangement. In the end I had command of 53 Gurkha soldiers from the 4th, 5th, 6th and 10th Regiments.

My Jemadar was not a good officer and we soon parted company. There were three pre-war NCO's; 15484 Havildar Purkadhoj Limbu, 15715 Naik Budhiman Limbu and a young, very fierce looking Lance Naik who had enlisted just before the war, 2175 Harkabahadur Limbu. All my Riflemen were babies, who had only just completed their recruit training at their Regimental Centres. Soon our mules and chargers arrived and we went off to collect them from Lalitpur Railway Station. Most of us had never handled a mule before and some mistakes were made in those early weeks, but in the end we grew to love them dearly.

Two other Gurkha Riflemen that formed part of Lt. Neill's Transport section, were his Orderly Shamsherbahadur Thapa, a rather solemn young man, who seldom smiled and who had obviously been reluctant to leave his original Gurkha unit in order to join 77th Brigade. The other soldier was 107394 Rifleman Prembahadur Rai of the 10th Gurkha Regiment, who was able to soothe his mules during the long marches through the Burmese jungles by playing to them on his bamboo flute. Sadly, although Prembahadur Rai did survive his time on Operation Longcloth, he was killed in action at the battle of Meiktila on the 13th March 1945, as the 14th Army began to expel the Japanese from Burma.

Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this first section of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Almost at the last minute, just a few weeks before the Brigade entered Burma, Lt. Neill was handed 20 more men from the King's Regiment to lead the mortar and machine-gun mules. With them came Sgt. William Ormandy formerly of the 17/21st Lancers, himself an accomplished horseman whose equestrian related knowledge would prove to be an invaluable addition to the Animal Transport section. Nick Neill remembered:

Ormandy's knowledge of horses if not mules was complete. In the coming months he was to be of the greatest assistance to me, as he taught me so much about caring for both horses and mules, I was much in his debt during those days. He helped me with my own charger 'Red Wagon', a beautiful dark chestnut stallion with a white blaze across his forehead. Our commander, Major Scott of the King's Regiment had ordered Ormandy and I to ride up and down the column lines during these early marches, in order to check on the progress and behaviour of the mules, it was during these moments that I learned much about my horse. My Syce (Groom), 67892 Dalbir Thapa, who had come to us from the 6th Gurkhas, had become devoted to his charge and had re-christened him 'Rate', as he said his coat was the colour of a Nepalese Barking Deer. And so he became Rate to us both from that moment on.

As the early weeks of Operation Longcloth unfolded, the mules began to suffer from galls and sores and their health deteriorated quite dramatically. The smell of rotting flesh was an ever-present on the long and arduous marches and section veterinarian orderly, Naik Ramphal was in constant attendance. Lt. Neill:

Soon we were moving across the Zinbon Taungdan Escarpment, through a narrow and little known track. This proved to be a hellish impediment for our poor and heavily-burdened mules, with their loads continuously being wegded tight or snagging on the jungle scrub. This route over the escarpment proved to be the beginning of the end for many of our brave mules, for it was here that well over half developed their first bad galls, mainly on their withers, but also on their flanks and stomachs from the slipping saddles and girth-straps. Despite daily ministrations by the kind and loving Naik Ramphal, my IAVC assistant, these dreadful injuries got worse and worse.

8 Column had a fairly quiet time during this period of the operation, involved in the odd skirmish with the enemy at places such as Sitsawk, Pinlebu and Kame. Most of the time they shadowed Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters, missing contact with the Japanese by small margins of time on several occasions. Lt. Neill and his men were kept busy with their work, especially around the time of column supply drops, when the mules were used in transporting the new supplies from the drop zone area, back into column harbour. One mule in particular had become very much a column favourite, as Nick Neill recalled:

Our mules had become personalities and friends to my muleteers and we all suffered with them, as only a master can for his animal. One should not have favourites I suppose, but I did have one such mule; she was No. 850. She was a beautiful pale dun coloured, country-bred animal and larger than most of the Indian mules. I called her 'Blondie' and she carried the bedding for Column HQ and was led by 107535 Harkabahadur Rai. She faired better than most during the operation, but in the end, just as we were about to re-cross the Irrawaddy we were ordered to let our mules and chargers go and drive them away from our ranks. This moment broke all of our hearts.

NB. From the latter pages of Nick Neill's memoir, it is stated that Blondie was actually acquired by 7 Column at the outward crossing of the Irrawaddy River in early March 1943. The two columns had been travelling in close proximity up until this juncture and during the crossing of the river their mules had become mixed together. After the expedition, Lt. Neill jokingly accused his counterpart and friend from 7 Column, Alex Irving of stealing his favourite and most beloved mule.

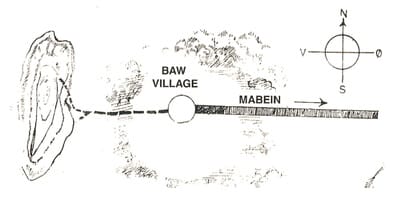

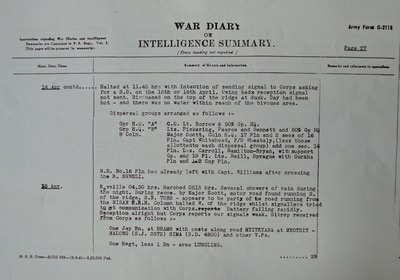

By the third week in March, 8 Column alongside 7 Column and Brigade Head Quarters, were positioned close to the Shweli River, near a Burmese village called Baw. Wingate decided to hold an officers conference at this point and to take a full Brigade supply drop to re-stock not just food rations, but also clothing, boots and of course much needed ammunition. The supply drop at Baw was planned for the 23/24 of March and was be an extremely large affair, re-supplying around 1300 men. The drop zone, which was a succession of dry paddy fields on the outskirts of the village would have to be secured well before the planes arrived and orders were given for two units of the Brigade to secure the main roads leading in and out of the village, one of the road blocks was to be manned by Platoon 17 of 8 Column, led by Captain Joseph Coughlan of the King's Regiment.

The platoon set off to secure the tracks to the east of the village and were supposed to be in place before first light the following morning. The men encountered some dense jungle during their journey to the agreed location and in the end Captain Coughlan called a halt to proceedings and told the men to bed down for a few hours until there was enough light to complete the march in comfort. This was to prove his units undoing and would cost the Captain his rank and his place in Column 8. At first light the platoon pushed on, but immediately ran into Japanese sentries, a Burma Rifleman shot one of the enemy, disastrously this brought out the entire Japanese garrison from the village and all element of surprise was lost.

Seen below are some images in relation to the supply drop held close to the village of Baw on the 24th March 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Ormandy's knowledge of horses if not mules was complete. In the coming months he was to be of the greatest assistance to me, as he taught me so much about caring for both horses and mules, I was much in his debt during those days. He helped me with my own charger 'Red Wagon', a beautiful dark chestnut stallion with a white blaze across his forehead. Our commander, Major Scott of the King's Regiment had ordered Ormandy and I to ride up and down the column lines during these early marches, in order to check on the progress and behaviour of the mules, it was during these moments that I learned much about my horse. My Syce (Groom), 67892 Dalbir Thapa, who had come to us from the 6th Gurkhas, had become devoted to his charge and had re-christened him 'Rate', as he said his coat was the colour of a Nepalese Barking Deer. And so he became Rate to us both from that moment on.

As the early weeks of Operation Longcloth unfolded, the mules began to suffer from galls and sores and their health deteriorated quite dramatically. The smell of rotting flesh was an ever-present on the long and arduous marches and section veterinarian orderly, Naik Ramphal was in constant attendance. Lt. Neill:

Soon we were moving across the Zinbon Taungdan Escarpment, through a narrow and little known track. This proved to be a hellish impediment for our poor and heavily-burdened mules, with their loads continuously being wegded tight or snagging on the jungle scrub. This route over the escarpment proved to be the beginning of the end for many of our brave mules, for it was here that well over half developed their first bad galls, mainly on their withers, but also on their flanks and stomachs from the slipping saddles and girth-straps. Despite daily ministrations by the kind and loving Naik Ramphal, my IAVC assistant, these dreadful injuries got worse and worse.

8 Column had a fairly quiet time during this period of the operation, involved in the odd skirmish with the enemy at places such as Sitsawk, Pinlebu and Kame. Most of the time they shadowed Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters, missing contact with the Japanese by small margins of time on several occasions. Lt. Neill and his men were kept busy with their work, especially around the time of column supply drops, when the mules were used in transporting the new supplies from the drop zone area, back into column harbour. One mule in particular had become very much a column favourite, as Nick Neill recalled:

Our mules had become personalities and friends to my muleteers and we all suffered with them, as only a master can for his animal. One should not have favourites I suppose, but I did have one such mule; she was No. 850. She was a beautiful pale dun coloured, country-bred animal and larger than most of the Indian mules. I called her 'Blondie' and she carried the bedding for Column HQ and was led by 107535 Harkabahadur Rai. She faired better than most during the operation, but in the end, just as we were about to re-cross the Irrawaddy we were ordered to let our mules and chargers go and drive them away from our ranks. This moment broke all of our hearts.

NB. From the latter pages of Nick Neill's memoir, it is stated that Blondie was actually acquired by 7 Column at the outward crossing of the Irrawaddy River in early March 1943. The two columns had been travelling in close proximity up until this juncture and during the crossing of the river their mules had become mixed together. After the expedition, Lt. Neill jokingly accused his counterpart and friend from 7 Column, Alex Irving of stealing his favourite and most beloved mule.

By the third week in March, 8 Column alongside 7 Column and Brigade Head Quarters, were positioned close to the Shweli River, near a Burmese village called Baw. Wingate decided to hold an officers conference at this point and to take a full Brigade supply drop to re-stock not just food rations, but also clothing, boots and of course much needed ammunition. The supply drop at Baw was planned for the 23/24 of March and was be an extremely large affair, re-supplying around 1300 men. The drop zone, which was a succession of dry paddy fields on the outskirts of the village would have to be secured well before the planes arrived and orders were given for two units of the Brigade to secure the main roads leading in and out of the village, one of the road blocks was to be manned by Platoon 17 of 8 Column, led by Captain Joseph Coughlan of the King's Regiment.

The platoon set off to secure the tracks to the east of the village and were supposed to be in place before first light the following morning. The men encountered some dense jungle during their journey to the agreed location and in the end Captain Coughlan called a halt to proceedings and told the men to bed down for a few hours until there was enough light to complete the march in comfort. This was to prove his units undoing and would cost the Captain his rank and his place in Column 8. At first light the platoon pushed on, but immediately ran into Japanese sentries, a Burma Rifleman shot one of the enemy, disastrously this brought out the entire Japanese garrison from the village and all element of surprise was lost.

Seen below are some images in relation to the supply drop held close to the village of Baw on the 24th March 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After some good work from the men of 7 & 8 Columns, the Japanese were eventually driven away from the village and the supply drop was able to continue. However, the engagement at Baw was to prove significant in persuading Brigadier Wingate that it was time to close the operation and order his men to return to India. Lt. Neill and his Gurkhas were heavily invovled in the collection and re-distribution of the supplies dropped at Baw. It was also at this time that it became necessary to promote Rifleman 107538 Pasang Lama to the rank of Naik. Nick Neill remembered:

Pasang Lama was one of the most intelligent young soldiers I have known. He was India-domiciled and came from the village of Dhanketi near Shillong. If he had survived the subsequent campaigns of the war, I am sure he would have risen to a much higher rank. None of my men in those days spoke any English, but Pasang was teaching himself as best he could. He would ask me questions and never forgot my answers. He was as bright as a button and became a great favourite with CSM Cheevers and all of the British muleteers, by whom he was always known as 'Johnson.'

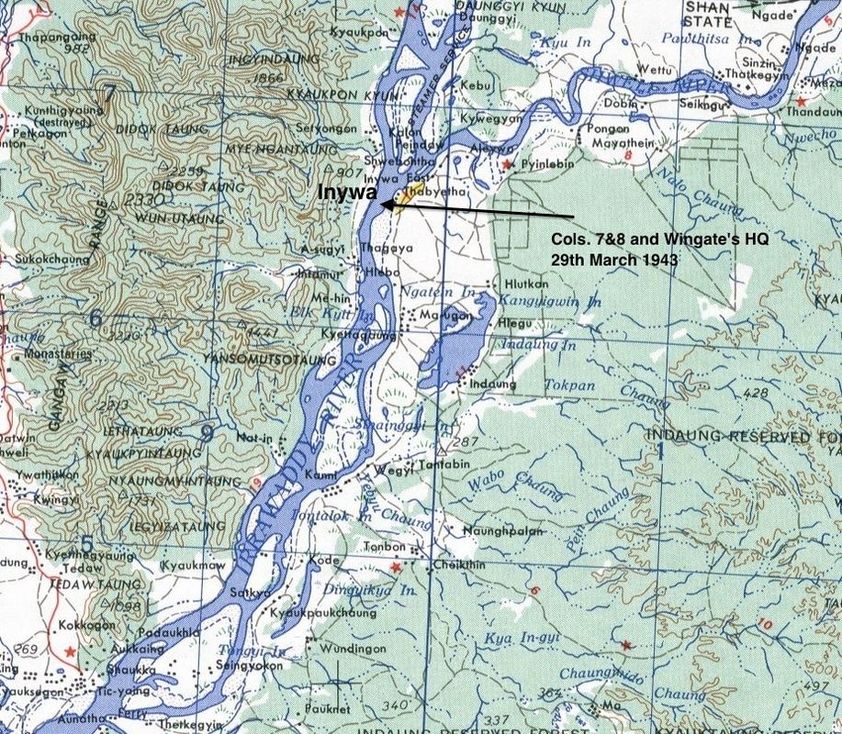

After the battle at Baw, 8 Column's commander, Major Scott confided with Lt. Neill in regards to the plan to call the operation off and return to India. Scott ordered the destruction of one of the mules, in order to distribute some much needed meat amongst the men and in particular the British soldiers who were struggling on their recent diet of mostly rice. The Brigade then headed north west towards the Irrawaddy, hoping to re-cross the river close to the village of Inywa. On the 29th March, Wingate and his Brigade HQ, along with Columns 7 and 8 reached the banks of the river about five miles north of Inywa. Several platoons from 7 Column were sent across to form a protective bridgehead on the western banks. Disaster struck when a large patrol of Japanese arrived on that side of the river and opened fire on the lead boats with their 4" mortars and machine guns. Many men were lost or killed and Wingate abandoned the now opposed crossing and the remaining Chindit groups on the east bank melted away into the nearby jungle.

Lt. Nick Neill recalled this moment in his memoir, One More River:

The opposed crossing at Inywa was the first time I had heard the sound of Japanese medium machine-guns. They had a much slower rate of fire than our Vickers MMGs and their distinctive tok-tok-tok-tok noise was imprinted in my memory from that moment on. British troops eventually christened them 'Woodpeckers.' The area we were in on the eastern bank of the Irrawaddy was a vast stretch of open paddy fields and I had a clear view of the far bank of the river, some two miles away. I could not see any sign of our men, but I could see the bursting Jap mortar bombs from time to time.

A group of men were approaching me across the paddy and when they came closer I realised that they were a group from Brigade HQ, led by Wingate himself. He was still wearing his sola topee, but now had a beard like the rest of us. I remember thinking that he looked just like a figure straight out of the Bible. As he passed by he was almost trotting, and his speed was causing his pack to bump up and down on his back. His eyes were wide and very staring; he called out to me and the others of my column standing nearby, "Disperse, disperse, get back to India." I recall thinking to myself, "My God, the man's gone mad. Here we are, a force of some 700 men, we have a platoon already across the Irrawaddy and he's not prepared to carry on with the crossing. This is too improbable to be true. There must be some other explanation to his behaviour."

The following day we received our air drop and then, for the first time, I was invited to join Scotty's '0' (orders) Group. It was indeed true that all columns of the Brigade were to be split up into much smaller groups and were to find their own way back to India, or China, the latter country being the nearest to us now. Our one radio in the column would go with Scotty's group after we had dispersed — lucky for some!

Wingate had now played us his final ace card. He had taken us deep into enemy held territory and now we were required to return to safety in penny-packets, on our own and without any communications, thus condemning us to receive no further administrative or tactical air support. In my judgement, we should have forced a crossing at the Irrawaddy when we had the chance and when we were in considerable strength. We would of course have taken casualties during the crossing, but these, I believe, would have been far fewer than those ultimately suffered by the Brigade as a whole.

NB. It was at this point that Nick Neill was ordered to release all his mules and his beloved charger Rate; many tears were shed. Lt. Neill continued:

I asked Lieutenant Tag Sprague, who commanded the column's commando/demolition section from 142 Company, if he and his small band of commandos might like to join my Gurkhas and I for the return journey. Much to my pleasure and relief he agreed readily to my suggestion. He was four years older than me and had fought in Norway with 1 Commando and we have remained friends to this day.

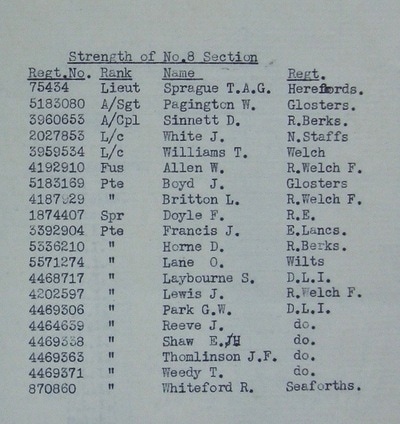

NB: Lieutenant 75434 Thomas Anthony Grafton Sprague formerly of the Herefordshire Regiment, was known as Tag to his friends and comrades. He was a bright and enthusiastic young officer, who commanded his section with honesty and fairness and was well liked by his men.

Pasang Lama was one of the most intelligent young soldiers I have known. He was India-domiciled and came from the village of Dhanketi near Shillong. If he had survived the subsequent campaigns of the war, I am sure he would have risen to a much higher rank. None of my men in those days spoke any English, but Pasang was teaching himself as best he could. He would ask me questions and never forgot my answers. He was as bright as a button and became a great favourite with CSM Cheevers and all of the British muleteers, by whom he was always known as 'Johnson.'

After the battle at Baw, 8 Column's commander, Major Scott confided with Lt. Neill in regards to the plan to call the operation off and return to India. Scott ordered the destruction of one of the mules, in order to distribute some much needed meat amongst the men and in particular the British soldiers who were struggling on their recent diet of mostly rice. The Brigade then headed north west towards the Irrawaddy, hoping to re-cross the river close to the village of Inywa. On the 29th March, Wingate and his Brigade HQ, along with Columns 7 and 8 reached the banks of the river about five miles north of Inywa. Several platoons from 7 Column were sent across to form a protective bridgehead on the western banks. Disaster struck when a large patrol of Japanese arrived on that side of the river and opened fire on the lead boats with their 4" mortars and machine guns. Many men were lost or killed and Wingate abandoned the now opposed crossing and the remaining Chindit groups on the east bank melted away into the nearby jungle.

Lt. Nick Neill recalled this moment in his memoir, One More River:

The opposed crossing at Inywa was the first time I had heard the sound of Japanese medium machine-guns. They had a much slower rate of fire than our Vickers MMGs and their distinctive tok-tok-tok-tok noise was imprinted in my memory from that moment on. British troops eventually christened them 'Woodpeckers.' The area we were in on the eastern bank of the Irrawaddy was a vast stretch of open paddy fields and I had a clear view of the far bank of the river, some two miles away. I could not see any sign of our men, but I could see the bursting Jap mortar bombs from time to time.

A group of men were approaching me across the paddy and when they came closer I realised that they were a group from Brigade HQ, led by Wingate himself. He was still wearing his sola topee, but now had a beard like the rest of us. I remember thinking that he looked just like a figure straight out of the Bible. As he passed by he was almost trotting, and his speed was causing his pack to bump up and down on his back. His eyes were wide and very staring; he called out to me and the others of my column standing nearby, "Disperse, disperse, get back to India." I recall thinking to myself, "My God, the man's gone mad. Here we are, a force of some 700 men, we have a platoon already across the Irrawaddy and he's not prepared to carry on with the crossing. This is too improbable to be true. There must be some other explanation to his behaviour."

The following day we received our air drop and then, for the first time, I was invited to join Scotty's '0' (orders) Group. It was indeed true that all columns of the Brigade were to be split up into much smaller groups and were to find their own way back to India, or China, the latter country being the nearest to us now. Our one radio in the column would go with Scotty's group after we had dispersed — lucky for some!

Wingate had now played us his final ace card. He had taken us deep into enemy held territory and now we were required to return to safety in penny-packets, on our own and without any communications, thus condemning us to receive no further administrative or tactical air support. In my judgement, we should have forced a crossing at the Irrawaddy when we had the chance and when we were in considerable strength. We would of course have taken casualties during the crossing, but these, I believe, would have been far fewer than those ultimately suffered by the Brigade as a whole.

NB. It was at this point that Nick Neill was ordered to release all his mules and his beloved charger Rate; many tears were shed. Lt. Neill continued:

I asked Lieutenant Tag Sprague, who commanded the column's commando/demolition section from 142 Company, if he and his small band of commandos might like to join my Gurkhas and I for the return journey. Much to my pleasure and relief he agreed readily to my suggestion. He was four years older than me and had fought in Norway with 1 Commando and we have remained friends to this day.

NB: Lieutenant 75434 Thomas Anthony Grafton Sprague formerly of the Herefordshire Regiment, was known as Tag to his friends and comrades. He was a bright and enthusiastic young officer, who commanded his section with honesty and fairness and was well liked by his men.

Dominic Neill coninues his story:

Scotty gave us the map co-ordinates of a number of pre-planned supply drop zones to the north where the RAF would be dropping supplies and to which we could go if we required further supplies during our withdrawal. He then issued us with maps and compasses, the first time I had been given such navigational aids. Now in the middle of a wilderness, with the same poor knowledge of map reading as before, I was being required to take my small group of ill-trained young Gurkhas over hundreds of miles of inhospitable terrain and through the whole of the Japanese 33rd Division, who were already searching for us with the intention of preventing our escape.

It is perhaps not surprising that I should have been so critical of Wingate's training methods and battle tactics. So, in the early part of April, Tag and I, with my fifty-two Gurkhas and his dozen or so commandos, split from 8 Column to begin our long march back to the Chindwin. We crammed ten days' bulky rations into our packs, the only supplies we would have unless we could buy some from villages on the way. I was given 400 silver rupees for this purpose and I put them into one of the two basic pouches on my web belt. They weighed a ton, as did my pack, and I nearly fell over as I put it on. The only way I could stand up straight was to place my rifle butt on the ground behind me and poke the muzzle underneath the pack to take the weight. But carry it I did, a man's pack from that day on carried very literally his lifeblood and it was never, ever to be discarded.

NB. Also included in the dispersal group led by Lieuts. Neill and Sprague, were the aforementioned Sgt. Ormandy and his own groom, Pte. Hand of the King's Regiment.

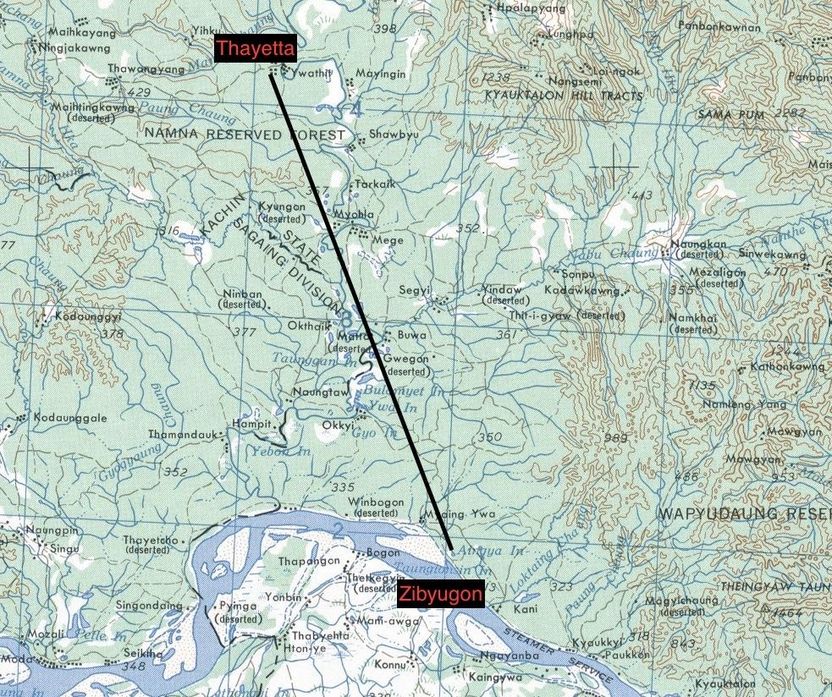

Tag and I decided to march in a northerly direction to try to recross the vast Irrawaddy somewhere along its stretch where it flows east-west between the big villages of Bhamo and Katha. We would have to avoid Shwegu though, as that village contained a Japanese garrison. Every escape group had been given a few soldiers from Nigel Whitehead's Platoon of 2nd Burma Rifles and we were delighted to find that we had Naik Tun Tin and four other Riflemen attached to us.

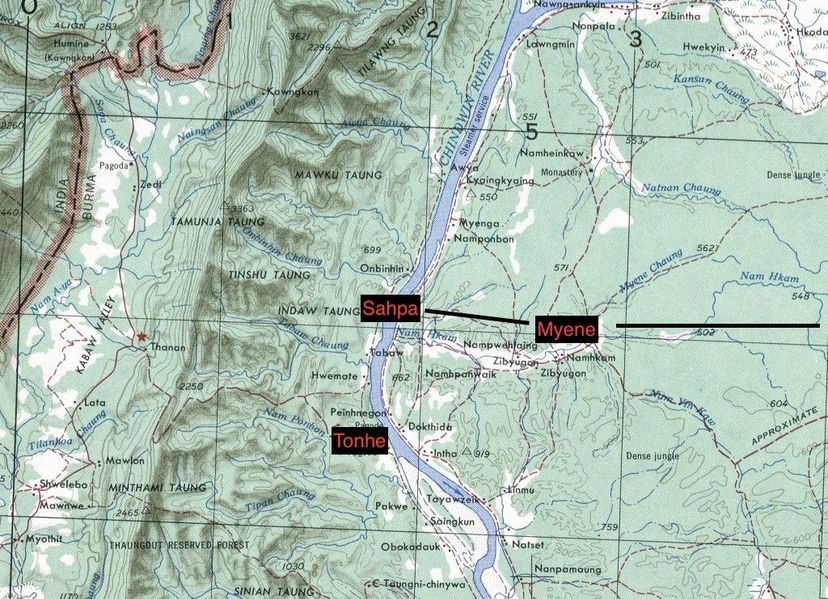

An outstanding NCO, Tun Tin and his men were from the Karen tribe and he had been educated at a mission school. He was very intelligent and spoke excellent English and was to prove to be of tremendous assistance to us. Sadly, however, we were soon parted from him. It took us four days to reach the Irrawaddy, near to the village of Zibyugon. The sal trees were in blossom; they smelt like a wet flannel and whenever I scent such a smell my mind goes back to that day at Zibyugon, and our brief stay there while we searched for boats to take us across the river. Tun Tin and two of his men changed into civilian clothes and went into Zibyugon to try to find boats to carry us across. He was successful and on the night of 11/12th April four or five boats appeared and ferried all of us across the river.

Scotty gave us the map co-ordinates of a number of pre-planned supply drop zones to the north where the RAF would be dropping supplies and to which we could go if we required further supplies during our withdrawal. He then issued us with maps and compasses, the first time I had been given such navigational aids. Now in the middle of a wilderness, with the same poor knowledge of map reading as before, I was being required to take my small group of ill-trained young Gurkhas over hundreds of miles of inhospitable terrain and through the whole of the Japanese 33rd Division, who were already searching for us with the intention of preventing our escape.

It is perhaps not surprising that I should have been so critical of Wingate's training methods and battle tactics. So, in the early part of April, Tag and I, with my fifty-two Gurkhas and his dozen or so commandos, split from 8 Column to begin our long march back to the Chindwin. We crammed ten days' bulky rations into our packs, the only supplies we would have unless we could buy some from villages on the way. I was given 400 silver rupees for this purpose and I put them into one of the two basic pouches on my web belt. They weighed a ton, as did my pack, and I nearly fell over as I put it on. The only way I could stand up straight was to place my rifle butt on the ground behind me and poke the muzzle underneath the pack to take the weight. But carry it I did, a man's pack from that day on carried very literally his lifeblood and it was never, ever to be discarded.

NB. Also included in the dispersal group led by Lieuts. Neill and Sprague, were the aforementioned Sgt. Ormandy and his own groom, Pte. Hand of the King's Regiment.

Tag and I decided to march in a northerly direction to try to recross the vast Irrawaddy somewhere along its stretch where it flows east-west between the big villages of Bhamo and Katha. We would have to avoid Shwegu though, as that village contained a Japanese garrison. Every escape group had been given a few soldiers from Nigel Whitehead's Platoon of 2nd Burma Rifles and we were delighted to find that we had Naik Tun Tin and four other Riflemen attached to us.

An outstanding NCO, Tun Tin and his men were from the Karen tribe and he had been educated at a mission school. He was very intelligent and spoke excellent English and was to prove to be of tremendous assistance to us. Sadly, however, we were soon parted from him. It took us four days to reach the Irrawaddy, near to the village of Zibyugon. The sal trees were in blossom; they smelt like a wet flannel and whenever I scent such a smell my mind goes back to that day at Zibyugon, and our brief stay there while we searched for boats to take us across the river. Tun Tin and two of his men changed into civilian clothes and went into Zibyugon to try to find boats to carry us across. He was successful and on the night of 11/12th April four or five boats appeared and ferried all of us across the river.

Nick Neill's memoir continues:

We made camp four miles from the Irrawaddy. We had crossed the major river obstacle between us and safety. We still had to cross the Chindwin and other smaller rivers, but they should present us with little difficulty, providing we crossed them before the monsoon rains broke in late May or early June. We had over 200 miles to cover before reaching the Chindwin. By the morning of 14th April we had crossed the Kaukkwe Chaung, a north-south flowing river which joined the Irrawaddy and entered the village of Thayetta.

Tun Tin was arranging the purchase of rice, chicken and vegetables while I sat down to remove my boots and examine my sore feet. I noticed briefly a villager leaving the village on a bicycle and heading north. I thought nothing of this at the time and did not realise the significance until later in the morning. We had not gone far from the village when, totally out of the blue, an ambush exploded abruptly to my immediate left. I can remember roaring out to my men 'Dahine tira sut' or in English, 'Take cover, right,' before diving for cover myself into the bushes to the right of the track. I remember I wasn't actually frightened, which surprised me, but I was totally and utterly shocked.

Never, ever, during any of my previous training had I been taught any of the approved contact drills; certainly the counter-ambush drill was unknown to me. I was utterly appalled to realise that I simply did not know what to do to extract myself and my men from our predicament. A Japanese gunner was firing his light machine gun immediately opposite me from the jungle on the far side of the track and another was firing at the men who were behind me. I could see the smoke rising from his gun muzzle and his bursts of fire were hitting the trees and bushes above my head. When the Jap gunner stopped firing to change magazines I roared above the noise of the continuing rifle fire, 'Sabai jana ut! Mero pachhi aija,' (Everybody up and follow me).

I leapt to my feet, turned away from the track and crashed through the jungle, calling to my men to follow. I looked around and saw some of my Gurkhas and Tag's men running parallel to me. When we finally halted and took stock of our situation and counted our strength: it was, two British Officers (Neill and Sprague), eleven Gurkha Other Ranks, including Havildar Budhiman, Naik Harkabahadur, former Havildar, now Rifleman Purkadhoj, my orderly, 107117 Bhagtabahadur Rai, my first orderly, Shamsherbahadur, Rifleman Pusta Lal Rai and five other Riflemen. Also present were six of Tag's commandos, including Sergeant Sinnett and Corporal White and one of Tun Tin's Riflemen, whose name I think was Maung San. The grand total was just 20 men. All the others, including Ormandy, Hand, Tun Tin and my Syce, Dalbir, were missing. I did not believe that many of the others had been killed, but those missing were without maps and compasses. My guilt at not being able to do better for them in the ambush, and being unable to maintain contact with them afterwards, hung very heavy on my conscience and still does to this day.

It would be untrue to say that I slept that night, other than closing my eyes and tossing about under my dirty blanket. My mind was in turmoil, as I went over in my thoughts, time and time again, the confused sequence of events of our ambush. I felt such utter guilt and shame that I'd not known what to do to protect my Gurkhas by mounting an immediate counter-attack on the Japanese; I had similar feelings as well over my failure to rally and collect my men after I'd given the order to withdraw from the killing ground. I vowed, that night, that if I succeeded in surviving this expedition, I would, by hook or by crook, teach myself and my soldiers proper contact drills and counter-ambush drills, so that, never again, would I suffer such an ignominious defeat as the one inflicted on us on that track outside the village of Thayetta. In later years during the war and in two sub-sequent campaigns afterwards, my Gurkhas and I were able to kill a very great number of enemy as a direct result of lessons learnt the hard way on 14th April, 1943.

NB. Lance Naik 107513 Kambasher Rai was known to have been wounded at Thayetta, after being shot in the leg. Sadly, he was never heard of again, although his name would never appear on any casualty lisitng for the battalion after the war, so hopefully he did survive. Also lost to the group on the 14th April, were Riflemen Gambhir Pun and Kale Rai, nothing more was ever discovered as to the fate of these men. There is no further information available in reference to Naik Tun Tin of the Burma Rifles and what happened to him after the ambush at Thayetta. However, another Naik with the same name is recorded as being one of the men from 8 Column that was flown out of the jungle in late April 1943, when a Dakota plane managed to put down on a jungle clearing and pick up 18 sick and wounded Chindits. To read more about this man and the incident in question, please click on the following link: The Piccadilly Incident

Lts. Sprague and Neill, along with the other survivors of the ambush put as much distance between themselves and the village of Thayetta as possible, before making camp for the night. The next day they set a course due west for the Chindwin and did not see a track again for three weeks. After a couple of days, Sergeant Sinnett and the other Commandos asked Lt. Sprague if they could turn about and head east for China. They planned to make for one of the pre-arranged drop zones, collect some much needed British rations and then make for the Chinese Yunnan Border. Sprague told them that they were mad to go to the drop-zone area, as the enemy would probably be waiting there by this time and by going towards China they would be heading into the unknown. The men remained adamant and with reluctance Sprague gave them a map and compass and allowed them to go. Most of these men were never seen or heard of again.

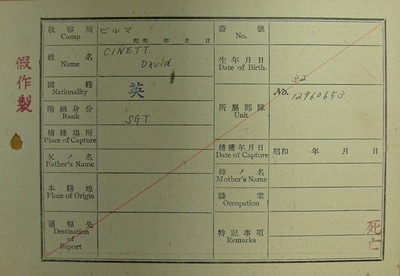

NB. Sergeant 3960653 David William Sinnett formerly of the Royal Berkshire Regiment, died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 29th July 1943, having been a prisoner of war for several weeks previously. He was given the POW number 575 whilst in the jail and was buried in the first instance, at the English Cantonment Cemetery, located close to the Royal Lakes in the eastern sector of Rangoon. To read more about the soldiers that made up the Commando Platoon in 8 Column, please click on the following link: Jim Tomlinson Column 8 Commando

Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

We made camp four miles from the Irrawaddy. We had crossed the major river obstacle between us and safety. We still had to cross the Chindwin and other smaller rivers, but they should present us with little difficulty, providing we crossed them before the monsoon rains broke in late May or early June. We had over 200 miles to cover before reaching the Chindwin. By the morning of 14th April we had crossed the Kaukkwe Chaung, a north-south flowing river which joined the Irrawaddy and entered the village of Thayetta.

Tun Tin was arranging the purchase of rice, chicken and vegetables while I sat down to remove my boots and examine my sore feet. I noticed briefly a villager leaving the village on a bicycle and heading north. I thought nothing of this at the time and did not realise the significance until later in the morning. We had not gone far from the village when, totally out of the blue, an ambush exploded abruptly to my immediate left. I can remember roaring out to my men 'Dahine tira sut' or in English, 'Take cover, right,' before diving for cover myself into the bushes to the right of the track. I remember I wasn't actually frightened, which surprised me, but I was totally and utterly shocked.

Never, ever, during any of my previous training had I been taught any of the approved contact drills; certainly the counter-ambush drill was unknown to me. I was utterly appalled to realise that I simply did not know what to do to extract myself and my men from our predicament. A Japanese gunner was firing his light machine gun immediately opposite me from the jungle on the far side of the track and another was firing at the men who were behind me. I could see the smoke rising from his gun muzzle and his bursts of fire were hitting the trees and bushes above my head. When the Jap gunner stopped firing to change magazines I roared above the noise of the continuing rifle fire, 'Sabai jana ut! Mero pachhi aija,' (Everybody up and follow me).

I leapt to my feet, turned away from the track and crashed through the jungle, calling to my men to follow. I looked around and saw some of my Gurkhas and Tag's men running parallel to me. When we finally halted and took stock of our situation and counted our strength: it was, two British Officers (Neill and Sprague), eleven Gurkha Other Ranks, including Havildar Budhiman, Naik Harkabahadur, former Havildar, now Rifleman Purkadhoj, my orderly, 107117 Bhagtabahadur Rai, my first orderly, Shamsherbahadur, Rifleman Pusta Lal Rai and five other Riflemen. Also present were six of Tag's commandos, including Sergeant Sinnett and Corporal White and one of Tun Tin's Riflemen, whose name I think was Maung San. The grand total was just 20 men. All the others, including Ormandy, Hand, Tun Tin and my Syce, Dalbir, were missing. I did not believe that many of the others had been killed, but those missing were without maps and compasses. My guilt at not being able to do better for them in the ambush, and being unable to maintain contact with them afterwards, hung very heavy on my conscience and still does to this day.

It would be untrue to say that I slept that night, other than closing my eyes and tossing about under my dirty blanket. My mind was in turmoil, as I went over in my thoughts, time and time again, the confused sequence of events of our ambush. I felt such utter guilt and shame that I'd not known what to do to protect my Gurkhas by mounting an immediate counter-attack on the Japanese; I had similar feelings as well over my failure to rally and collect my men after I'd given the order to withdraw from the killing ground. I vowed, that night, that if I succeeded in surviving this expedition, I would, by hook or by crook, teach myself and my soldiers proper contact drills and counter-ambush drills, so that, never again, would I suffer such an ignominious defeat as the one inflicted on us on that track outside the village of Thayetta. In later years during the war and in two sub-sequent campaigns afterwards, my Gurkhas and I were able to kill a very great number of enemy as a direct result of lessons learnt the hard way on 14th April, 1943.

NB. Lance Naik 107513 Kambasher Rai was known to have been wounded at Thayetta, after being shot in the leg. Sadly, he was never heard of again, although his name would never appear on any casualty lisitng for the battalion after the war, so hopefully he did survive. Also lost to the group on the 14th April, were Riflemen Gambhir Pun and Kale Rai, nothing more was ever discovered as to the fate of these men. There is no further information available in reference to Naik Tun Tin of the Burma Rifles and what happened to him after the ambush at Thayetta. However, another Naik with the same name is recorded as being one of the men from 8 Column that was flown out of the jungle in late April 1943, when a Dakota plane managed to put down on a jungle clearing and pick up 18 sick and wounded Chindits. To read more about this man and the incident in question, please click on the following link: The Piccadilly Incident

Lts. Sprague and Neill, along with the other survivors of the ambush put as much distance between themselves and the village of Thayetta as possible, before making camp for the night. The next day they set a course due west for the Chindwin and did not see a track again for three weeks. After a couple of days, Sergeant Sinnett and the other Commandos asked Lt. Sprague if they could turn about and head east for China. They planned to make for one of the pre-arranged drop zones, collect some much needed British rations and then make for the Chinese Yunnan Border. Sprague told them that they were mad to go to the drop-zone area, as the enemy would probably be waiting there by this time and by going towards China they would be heading into the unknown. The men remained adamant and with reluctance Sprague gave them a map and compass and allowed them to go. Most of these men were never seen or heard of again.

NB. Sergeant 3960653 David William Sinnett formerly of the Royal Berkshire Regiment, died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 29th July 1943, having been a prisoner of war for several weeks previously. He was given the POW number 575 whilst in the jail and was buried in the first instance, at the English Cantonment Cemetery, located close to the Royal Lakes in the eastern sector of Rangoon. To read more about the soldiers that made up the Commando Platoon in 8 Column, please click on the following link: Jim Tomlinson Column 8 Commando

Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Nick Neill takes up the story once more:

As the days and then the weeks went by, I came to rely on Tag more and more; he rapidly became my reservoir of inner strength. We never had a cross word and we never disagreed with one another, which was really quite remarkable, bearing in mind the stress under which we were existing. In my darkest hours, he was always there to give advice or to share a joke. I know very well that my chances of getting back over the Chindwin would have been very slim without him.

I also became dependent on my Gurkhas for many things. Their cheerfulness in adversity was so comforting. They always had a smile in their eyes. They never complained about the cards that fate had dealt them. They never, ever queried Tag's and my decision to go west to the Chindwin. Without them, Tag and I would probably have starved. We had to make the rice we had bought at Thayetta and it wasn't very much, last for a very long time. Tag and I recollect that we went to three villages only in all, to seek food, between Thayetta and the Chindwin. My men's knowledge of what wild plants and fungi we could eat soon became all-important to our survival.

Such wild food helped eke out our meagre ration of rice and helped give us some extra strength with which to fight the ever-present bogeyman that is fear. For my own part and I cannot really speak for the others, it was not so much the fear of death that was so corrosive, but the fear of capture. And it was the fear of capture that became, for me, worse and worse as the Chindwin came, so very slowly, nearer and nearer; as that safety-line approached this tension became greater and greater within me.

It must have been round about this time that I relieved my orderly, Bhagtabahadur Rai, of his tiresome duties and asked Havildar Budhiman to detail a fresh relief. 107289 Pustalal Rai now became my orderly. I have often wondered why, during our long march back to the Chindwin, I ever bothered to have an orderly, as there was absolutely nothing that had to be done for me; no uniforms to look after, no bed to make up, no leather-work to polish and no lean-to shelter or bamboo bed to build for me.

Our hard, long marches on hardly any food were beginning to sap the strength of all of us, so, in fairness to the soldier detailed to act as my orderly, I packed and unpacked my kit myself each day. I slept on the ground and did whatever cooking might be necessary myself sharing the fire that my orderly had made for himself. Pustalal was a rather stolid young man, but he had the engaging, cheerful and resolute nature of all his fellow countrymen. I quickly became very attached and devoted to him. I found, to my surprise, that my men from the 10th Regiment in my party always used English when referring to a man whose regimental number ended in either 89 or 99. Since I had known him, Pustalal had, therefore, always been known as 'Eighty-Nine', rather than 'Unanabbe', as would have been the custom in the 2nd Regiment.

As the beleaguerd party wearily marched on, they discovered that they were now infested with lice which lived in their shirt seams and socks. The lice did not bother them so much during the day, but made them itch and scratch so much at night that they slept without clothes; this resulted in many of the subsequent scratches turning quickly into infected jungle sores. Eventually they reached the Mawhun/Mawlu Road, which ran parallel to the railway just a couple of hundred yards away. They crossed both obstacles without delay and entered the Mawhun Reserved Forest. They then had eighteen miles to the Meza River and when they arrived they found the river was only fifty yards wide, with only little water in its bed.

Lt. Neill recalled:

My tired mind, with its sights set forever on the Chindwin, recalled a time from the past when my mother used to sit me on her knee and, bouncing me up and down, she would sing the old American negro spiritual hymn "One More River", the words from which so aptly fitted both my frame of mind and our ultimate aim: One more river, that's the River of Jordan, One more river, that's the river to cross, One more river, that's the River of Jordan, One more river, that's the river for me.

The Jordan of the hymn became the Chindwin of my thoughts and prayers. It helped me push my tired legs ever westwards. Sleep at night did not come easily at this time. We were only using game trails, but at night we would move as far away from the trail as possible and, like hunted animals, seek the thickest cover available. My blanket was used during the day as a pad between my pack and my back and by nightfall it would be soaked through by my sweat. It was a pretty chilly thing to wrap around me, particularly if we were on very high ground.

Then one night it rained very hard. It was on this night, with the rain water soaking through my already damp blanket and running down the slope either side of where I lay, that I really started to pray to God for deliverance. I suspect that many a soldier, in times of grave danger and misfortune, has prayed to his Maker for help, just as I did in those dark days. It was after this that we came across the buffaloes in the Namma Reserve Forest and I began to think that some of my prayers were being heard. Each day two of my Riflemen, 107871 Bandilal Limbu and 107524 Dhanbahadur Rai, would volunteer to scout ahead of our small party. Tag or I would follow behind them and concentrate on reading our compasses. Suddenly on the morning after the heavy rainfall, Bandilal turned to me and whispered, "Bhainsi, saheb. Hanum, ki?" (Buffalo, Sir. Shall I shoot?) Sure enough, there were four village buffaloes wallowing in the water of a fairly deep-sided chaung just ahead of us. Manna from heaven!

Tag and I looked at each other. Should we take the risk, or would the firing of a shot alert a hostile villager? We were nearly starving and had to take the risk. Tag took Bandilal's rifle, aimed carefully at the nearest buffalo and killed the unfortunate beast cleanly with one shot. The other buffaloes scattered in panic at the sound of the shot, which I hoped was muffled by the steepness of the chaung banks. The men dragged the buffalo out of the chaung and proceeded to butcher it on the spot. Soon a large fire was built from the driest wood, to minimise smoke, and the meat was smoked and roasted in the fire in no time at all. We were so hungry that many of us ate quite a number of pieces of meat before they were properly cooked through, with the blood running down our chins. Soon the buffalo had disappeared. Our stomachs were full to bursting and we had some left over to carry with us on our journey.

It was now the middle of May and the stricken party still had a long way to go before reaching the Chindwin. They crossed the Zibyu Taungdan escarpment by struggling along a very prominent river called the Chaunggyi, shaped, in its course, like a dog's leg. It cut through the escarpment via a pass, then continued its journey west to flow into the Uyu River, which in turn flowed west to join the Chindwin about two miles south of the important village of Homalin where there was a large Japanese garrison. This ten mile stretch took them over three days to achieve. Not long after, another Gurka Rifleman was lost to the group after it accidentily bumped into a truck load of Japanese on the bend of a narrow track and a firefight had ensued. Lt. Neill ordered his men to disperse as quickly as their ailing bodies would allow. After halting some little time later to catch his breath, he was informed by Havildar Budhiman that Rifleman Pustalal Rai was missing:

A cold, cold chill seemed to hit me then, when I heard that Pustalal was missing. In the few weeks he'd been my Orderly, I'd become so attached to him. To think of him now lying dead, or worse, having been captured, only a few hundred yards behind us was heart-breaking. I couldn't believe what I'd been told. I looked at Budhiman again: "Ho ra?" (Is that so) I asked, in disbelief. He looked back at me with pain in his eyes and, moving his head slowly from side to side, replied softly, "Hajur. (Yes Sir)." I told Tag what Budhiman and I had been saying to one another and that Eighty-Nine was missing. He was as sad as I was. We shared everything in those days, did Tag and I, and sorrow was no exception. But we couldn't remain here at this spot forever. We had to press on, otherwise a Jap follow-up party would catch up with us all.

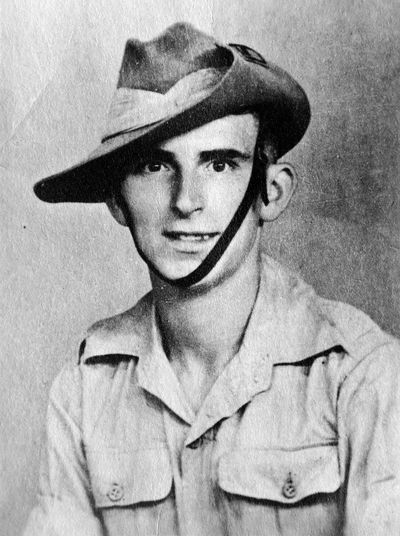

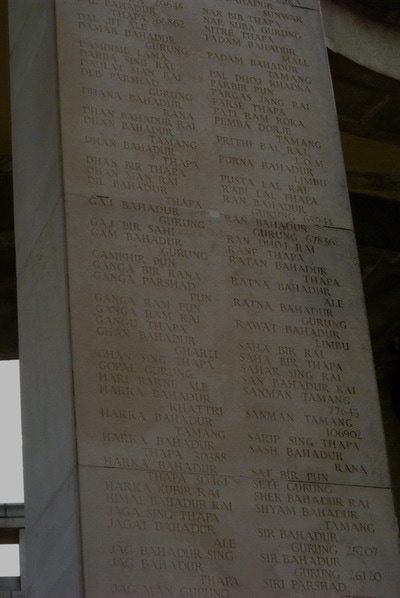

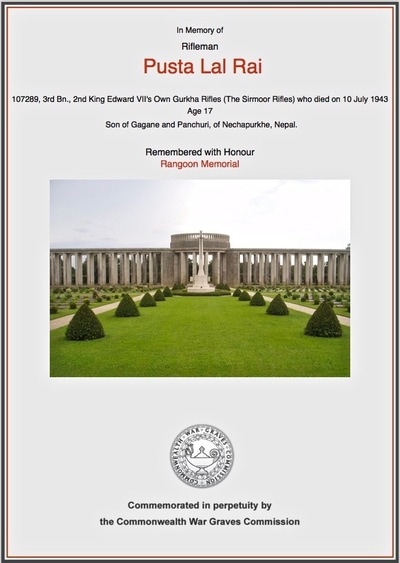

Seen below is a Gallery of images in honour of Rifleman Pusta Lal Rai, the seventeen year old son of Gagane and Panchuri Rai from the village of Nechapurkhe in Nepal. His recorded date of death on the CWGC website, the 10th July 1943, was the official closing date for any soldiers still reported as missing in action from the first Wingate expedition and of whom no further information was known. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As the days and then the weeks went by, I came to rely on Tag more and more; he rapidly became my reservoir of inner strength. We never had a cross word and we never disagreed with one another, which was really quite remarkable, bearing in mind the stress under which we were existing. In my darkest hours, he was always there to give advice or to share a joke. I know very well that my chances of getting back over the Chindwin would have been very slim without him.

I also became dependent on my Gurkhas for many things. Their cheerfulness in adversity was so comforting. They always had a smile in their eyes. They never complained about the cards that fate had dealt them. They never, ever queried Tag's and my decision to go west to the Chindwin. Without them, Tag and I would probably have starved. We had to make the rice we had bought at Thayetta and it wasn't very much, last for a very long time. Tag and I recollect that we went to three villages only in all, to seek food, between Thayetta and the Chindwin. My men's knowledge of what wild plants and fungi we could eat soon became all-important to our survival.

Such wild food helped eke out our meagre ration of rice and helped give us some extra strength with which to fight the ever-present bogeyman that is fear. For my own part and I cannot really speak for the others, it was not so much the fear of death that was so corrosive, but the fear of capture. And it was the fear of capture that became, for me, worse and worse as the Chindwin came, so very slowly, nearer and nearer; as that safety-line approached this tension became greater and greater within me.

It must have been round about this time that I relieved my orderly, Bhagtabahadur Rai, of his tiresome duties and asked Havildar Budhiman to detail a fresh relief. 107289 Pustalal Rai now became my orderly. I have often wondered why, during our long march back to the Chindwin, I ever bothered to have an orderly, as there was absolutely nothing that had to be done for me; no uniforms to look after, no bed to make up, no leather-work to polish and no lean-to shelter or bamboo bed to build for me.

Our hard, long marches on hardly any food were beginning to sap the strength of all of us, so, in fairness to the soldier detailed to act as my orderly, I packed and unpacked my kit myself each day. I slept on the ground and did whatever cooking might be necessary myself sharing the fire that my orderly had made for himself. Pustalal was a rather stolid young man, but he had the engaging, cheerful and resolute nature of all his fellow countrymen. I quickly became very attached and devoted to him. I found, to my surprise, that my men from the 10th Regiment in my party always used English when referring to a man whose regimental number ended in either 89 or 99. Since I had known him, Pustalal had, therefore, always been known as 'Eighty-Nine', rather than 'Unanabbe', as would have been the custom in the 2nd Regiment.

As the beleaguerd party wearily marched on, they discovered that they were now infested with lice which lived in their shirt seams and socks. The lice did not bother them so much during the day, but made them itch and scratch so much at night that they slept without clothes; this resulted in many of the subsequent scratches turning quickly into infected jungle sores. Eventually they reached the Mawhun/Mawlu Road, which ran parallel to the railway just a couple of hundred yards away. They crossed both obstacles without delay and entered the Mawhun Reserved Forest. They then had eighteen miles to the Meza River and when they arrived they found the river was only fifty yards wide, with only little water in its bed.

Lt. Neill recalled:

My tired mind, with its sights set forever on the Chindwin, recalled a time from the past when my mother used to sit me on her knee and, bouncing me up and down, she would sing the old American negro spiritual hymn "One More River", the words from which so aptly fitted both my frame of mind and our ultimate aim: One more river, that's the River of Jordan, One more river, that's the river to cross, One more river, that's the River of Jordan, One more river, that's the river for me.

The Jordan of the hymn became the Chindwin of my thoughts and prayers. It helped me push my tired legs ever westwards. Sleep at night did not come easily at this time. We were only using game trails, but at night we would move as far away from the trail as possible and, like hunted animals, seek the thickest cover available. My blanket was used during the day as a pad between my pack and my back and by nightfall it would be soaked through by my sweat. It was a pretty chilly thing to wrap around me, particularly if we were on very high ground.

Then one night it rained very hard. It was on this night, with the rain water soaking through my already damp blanket and running down the slope either side of where I lay, that I really started to pray to God for deliverance. I suspect that many a soldier, in times of grave danger and misfortune, has prayed to his Maker for help, just as I did in those dark days. It was after this that we came across the buffaloes in the Namma Reserve Forest and I began to think that some of my prayers were being heard. Each day two of my Riflemen, 107871 Bandilal Limbu and 107524 Dhanbahadur Rai, would volunteer to scout ahead of our small party. Tag or I would follow behind them and concentrate on reading our compasses. Suddenly on the morning after the heavy rainfall, Bandilal turned to me and whispered, "Bhainsi, saheb. Hanum, ki?" (Buffalo, Sir. Shall I shoot?) Sure enough, there were four village buffaloes wallowing in the water of a fairly deep-sided chaung just ahead of us. Manna from heaven!

Tag and I looked at each other. Should we take the risk, or would the firing of a shot alert a hostile villager? We were nearly starving and had to take the risk. Tag took Bandilal's rifle, aimed carefully at the nearest buffalo and killed the unfortunate beast cleanly with one shot. The other buffaloes scattered in panic at the sound of the shot, which I hoped was muffled by the steepness of the chaung banks. The men dragged the buffalo out of the chaung and proceeded to butcher it on the spot. Soon a large fire was built from the driest wood, to minimise smoke, and the meat was smoked and roasted in the fire in no time at all. We were so hungry that many of us ate quite a number of pieces of meat before they were properly cooked through, with the blood running down our chins. Soon the buffalo had disappeared. Our stomachs were full to bursting and we had some left over to carry with us on our journey.

It was now the middle of May and the stricken party still had a long way to go before reaching the Chindwin. They crossed the Zibyu Taungdan escarpment by struggling along a very prominent river called the Chaunggyi, shaped, in its course, like a dog's leg. It cut through the escarpment via a pass, then continued its journey west to flow into the Uyu River, which in turn flowed west to join the Chindwin about two miles south of the important village of Homalin where there was a large Japanese garrison. This ten mile stretch took them over three days to achieve. Not long after, another Gurka Rifleman was lost to the group after it accidentily bumped into a truck load of Japanese on the bend of a narrow track and a firefight had ensued. Lt. Neill ordered his men to disperse as quickly as their ailing bodies would allow. After halting some little time later to catch his breath, he was informed by Havildar Budhiman that Rifleman Pustalal Rai was missing:

A cold, cold chill seemed to hit me then, when I heard that Pustalal was missing. In the few weeks he'd been my Orderly, I'd become so attached to him. To think of him now lying dead, or worse, having been captured, only a few hundred yards behind us was heart-breaking. I couldn't believe what I'd been told. I looked at Budhiman again: "Ho ra?" (Is that so) I asked, in disbelief. He looked back at me with pain in his eyes and, moving his head slowly from side to side, replied softly, "Hajur. (Yes Sir)." I told Tag what Budhiman and I had been saying to one another and that Eighty-Nine was missing. He was as sad as I was. We shared everything in those days, did Tag and I, and sorrow was no exception. But we couldn't remain here at this spot forever. We had to press on, otherwise a Jap follow-up party would catch up with us all.

Seen below is a Gallery of images in honour of Rifleman Pusta Lal Rai, the seventeen year old son of Gagane and Panchuri Rai from the village of Nechapurkhe in Nepal. His recorded date of death on the CWGC website, the 10th July 1943, was the official closing date for any soldiers still reported as missing in action from the first Wingate expedition and of whom no further information was known. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Both Nick Neill and Tag Sprague deeply regretted their decision to travel along that narrow track which had ultimately led to Rifleman Pusta Lal Rai's disappearance. The party now comprised just thirteen men, all very weak and suffering from exhaustion and malnutrition.

Naik Harkabahadur had also gone down with a severe bout of malaria at this point, with the others taking up and carrying his equipment and pack without word of complaint. Lt. Neill remembered:

Harkabahadur was very ill, his face had shrunken and his skin was a pale yellow colour. Within a day his head looked like a skull and his body like a skeleton.

The group were now just a few miles from the Chindwin River and close to a village called Myene. Incredibly, it took the men a further ten days to cover the sixteen miles from Myene to the village of Sahpa on the east bank of the Chindwin. They had passed through much of the area frequented by 8 Column on the outward journey in February 1943 and had hoped to find a friendly villager to help them back across the river. Upon reaching the village of Sahpa they discovered that the Japanese had recently collected every single boat from all of the villages on the east bank of the river and taken them north to the garrison at Homalin.

Nick Neill recalled:

Suddenly we saw again the Chindwin, the River Jordan of my hymn. At this point it was some 250 yards across and fast flowing. Tag and I could probably have swum it without arms and equipment, but none of my men could swim and we would not leave them. I went to stand on a little open rise on the bank of the river and gazed longingly across to the safety of the other side. Suddenly I heard a shout from the far side, "Ko ho?" I could not believe it, I was being hailed in Nepalese. I shouted back at once, "Hami Thard Sikin Gorkha haun. Tyahan dunga chha, ki? Yatapatti rahenachha," (We are the Third Second Gurkhas. Is there a boat over there? We find there is none on this side). Immediately the reply came: "Euta chha, ma pathaidinchhu. Parkhanu hos, hail" (There is one, I will send it. Please wait).

I stood the men to, and we took up defensive positions with our backs to the river. Most of our rifles were rusty due to the lack of oil, although my tommy gun was still in working order. I prayed to God that the Japs would not jump us at this eleventh hour. It was about 1400 hours on the 6th June. Eventually a small dug-out type boat appeared, being paddled upstream against the strong current by a single boatman. It could only take four men at a time, so I sent Havildar Budhiman, the sick Harkabahadur and two Riflemen in the first boat. It took twenty minutes for the return journey and three more trips before Tag and I clambered down the steep track to the river's edge, placed our packs in the centre of the dug-out and carefully climbed aboard.

We rounded the bend in the river and saw a tiny encampment on the west bank. It was the V-Force post at Hwemate and we could see the smiling faces of the others waiting to greet us, together with the British Officer commanding the post. We had made it! We would live to fight another day!

The group did not know how fortunate they had actually been. Another V-Force reconnaissance patrol crossed the river the very next day and visited Sahpa, here they learnt that a Japanese fighting patrol of platoon strength had been tracking Neill's party for over a week. They had been very close on their heels and had arrived at their crossing point on the bank of the Chindwin a mere half hour after they had crossed. The thirteen men were eventually taken to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station near Imphal, where they were tended by Matron Agnes MacGearey and her staff. It was whilst recovering at the hospital, that Nick Neill discovered that Sgt. Ormandy and Pte. Hand had managed to join up with the dispersal group led by Captain John Carroll, just a few days after the ambush at Thayetta and had exited Burma during the third week of April.

Naik Harkabahadur had also gone down with a severe bout of malaria at this point, with the others taking up and carrying his equipment and pack without word of complaint. Lt. Neill remembered:

Harkabahadur was very ill, his face had shrunken and his skin was a pale yellow colour. Within a day his head looked like a skull and his body like a skeleton.

The group were now just a few miles from the Chindwin River and close to a village called Myene. Incredibly, it took the men a further ten days to cover the sixteen miles from Myene to the village of Sahpa on the east bank of the Chindwin. They had passed through much of the area frequented by 8 Column on the outward journey in February 1943 and had hoped to find a friendly villager to help them back across the river. Upon reaching the village of Sahpa they discovered that the Japanese had recently collected every single boat from all of the villages on the east bank of the river and taken them north to the garrison at Homalin.

Nick Neill recalled:

Suddenly we saw again the Chindwin, the River Jordan of my hymn. At this point it was some 250 yards across and fast flowing. Tag and I could probably have swum it without arms and equipment, but none of my men could swim and we would not leave them. I went to stand on a little open rise on the bank of the river and gazed longingly across to the safety of the other side. Suddenly I heard a shout from the far side, "Ko ho?" I could not believe it, I was being hailed in Nepalese. I shouted back at once, "Hami Thard Sikin Gorkha haun. Tyahan dunga chha, ki? Yatapatti rahenachha," (We are the Third Second Gurkhas. Is there a boat over there? We find there is none on this side). Immediately the reply came: "Euta chha, ma pathaidinchhu. Parkhanu hos, hail" (There is one, I will send it. Please wait).

I stood the men to, and we took up defensive positions with our backs to the river. Most of our rifles were rusty due to the lack of oil, although my tommy gun was still in working order. I prayed to God that the Japs would not jump us at this eleventh hour. It was about 1400 hours on the 6th June. Eventually a small dug-out type boat appeared, being paddled upstream against the strong current by a single boatman. It could only take four men at a time, so I sent Havildar Budhiman, the sick Harkabahadur and two Riflemen in the first boat. It took twenty minutes for the return journey and three more trips before Tag and I clambered down the steep track to the river's edge, placed our packs in the centre of the dug-out and carefully climbed aboard.

We rounded the bend in the river and saw a tiny encampment on the west bank. It was the V-Force post at Hwemate and we could see the smiling faces of the others waiting to greet us, together with the British Officer commanding the post. We had made it! We would live to fight another day!