The Diary of Sergeant Harold Palmer

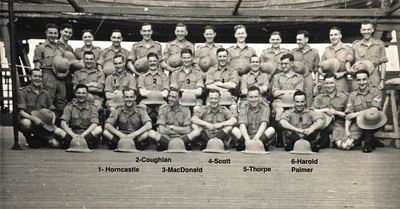

Harold Palmer in India, 1942.

Harold Palmer in India, 1942.

Sergeant 3781603 Harold Palmer was born on the 7th January 1912 and was the son of Charles and Jane Palmer from Droylesden in Manchester. He had been one of the original members of the 13th Battalion that voyaged to India aboard the troopship 'Oronsay', on the 8th December 1941. Harold was placed into Chindit Column 8 in July 1942 as the 13th King's began their training for the first Wingate expedition at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India.

In late February 2016, I received an email contact via my website from Harold's granddaughter, Claire McHenry.

I was looking though your website and I saw that my Grandad, Harold Palmer was mentioned in relation to the story Pte. John Bromley and the members of Captain Raymond Williams' platoon. I can see that there is a contribution by John Bromley's son and granddaughter, and I wondered if they would be interested in seeing a copy of my Grandad's diary, which I suspect gives the details of the occasion when John was killed.

I found your website really interesting and it has given me a bit more information. Grandad's diary is a fascinating read and very moving at times. I am happy to be able to share this with you and I hope you enjoy reading it. There are some words that we have not been able to decipher, so those are the words or gaps shown in brackets. My Grandad mentions No. 1 Section, so we have always presumed that he was part of Column 1, but everything I've seen on your website suggests Column 8. Do you know what No.1 section might refer to?

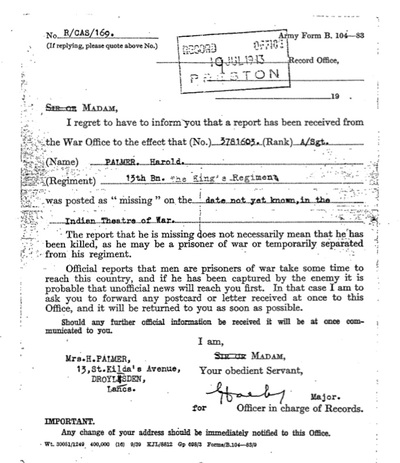

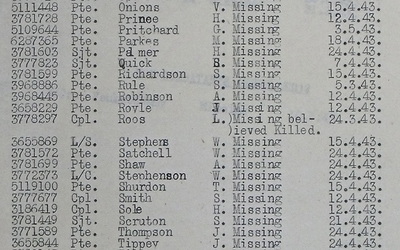

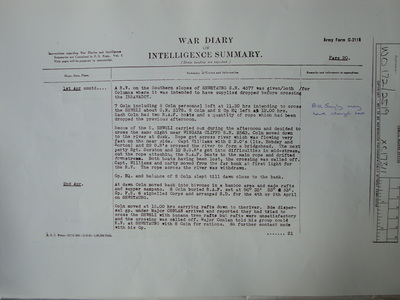

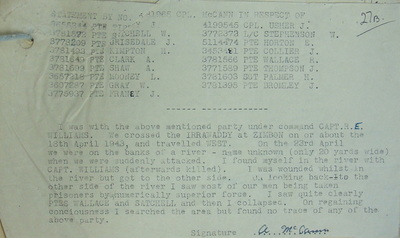

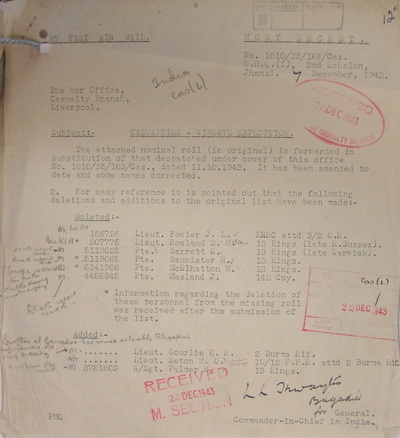

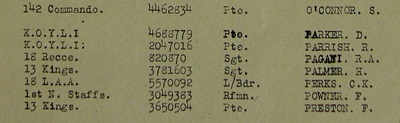

I explained that in each Chindit column there were 3 Rifle platoons. The rifle the Chindits used was the Lee Enfield. Each platoon was commanded by a Lieutenant, with a Sergeant as second in command. A platoon was made up of 2 or 3 sections of ten men each, with a Corporal in charge of a section. So I would say that Harold was the Sergeant for one of the platoons in 8 Column and was possibly referring to number one section of his platoon. Harold Palmer features in the nominal roll of the missing men from 8 Column, which was commanded in 1943 by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment.

Sergeant Palmer is listed as being missing in action as of 24th April 1943 and was last seen with Captain Williams' platoon after they crossed the Shweli River on the 1st April. Some of the witness statements given by surviving Chindits from Operation Longcloth place Harold with a party of men ambushed by the Japanese on the banks of the Irrawaddy, near a village called Zinbon. To read more about these incidents and the fate of Captain Williams' Platoon, please click on the following link: Captain Raymond Williams' Platoon

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In late February 2016, I received an email contact via my website from Harold's granddaughter, Claire McHenry.

I was looking though your website and I saw that my Grandad, Harold Palmer was mentioned in relation to the story Pte. John Bromley and the members of Captain Raymond Williams' platoon. I can see that there is a contribution by John Bromley's son and granddaughter, and I wondered if they would be interested in seeing a copy of my Grandad's diary, which I suspect gives the details of the occasion when John was killed.

I found your website really interesting and it has given me a bit more information. Grandad's diary is a fascinating read and very moving at times. I am happy to be able to share this with you and I hope you enjoy reading it. There are some words that we have not been able to decipher, so those are the words or gaps shown in brackets. My Grandad mentions No. 1 Section, so we have always presumed that he was part of Column 1, but everything I've seen on your website suggests Column 8. Do you know what No.1 section might refer to?

I explained that in each Chindit column there were 3 Rifle platoons. The rifle the Chindits used was the Lee Enfield. Each platoon was commanded by a Lieutenant, with a Sergeant as second in command. A platoon was made up of 2 or 3 sections of ten men each, with a Corporal in charge of a section. So I would say that Harold was the Sergeant for one of the platoons in 8 Column and was possibly referring to number one section of his platoon. Harold Palmer features in the nominal roll of the missing men from 8 Column, which was commanded in 1943 by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment.

Sergeant Palmer is listed as being missing in action as of 24th April 1943 and was last seen with Captain Williams' platoon after they crossed the Shweli River on the 1st April. Some of the witness statements given by surviving Chindits from Operation Longcloth place Harold with a party of men ambushed by the Japanese on the banks of the Irrawaddy, near a village called Zinbon. To read more about these incidents and the fate of Captain Williams' Platoon, please click on the following link: Captain Raymond Williams' Platoon

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

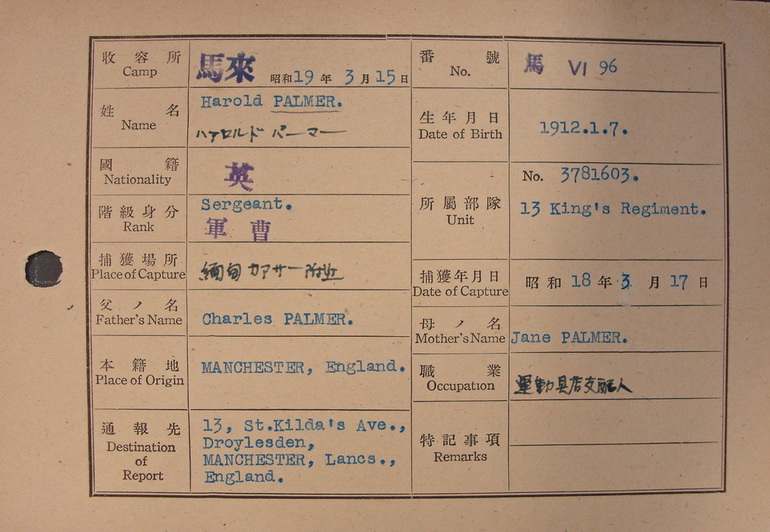

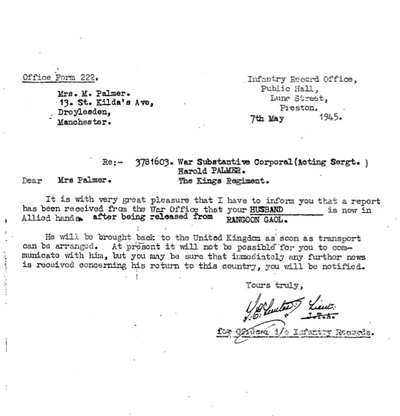

Harold Palmer was captured by the Japanese on the 17th April 1943. He was given the POW number 96 (Kyuu juu roku) whilst in Rangoon Jail, where he spent just over two years as a prisoner of war before being liberated in late April 1945. According to his POW index card he was captured close to the town of Katha near the Irrawaddy River on the 17th March 1943. Although the location very much matches the eye witness statements for the ambush at Zinbon, the capture date is incorrect by one month. I believe this is a simple clerical error by the person who filled out Harold's card. Adding further weight to this viewpoint, if you zoom in on the date shown on the card (seen below) you can see that underneath the 3, there was once a 4 which would then depict the correct month of April.

From reading through Harold's diary, I noticed that he was heavily involved in assisting with the medical needs of the wounded and ill inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail during his time as a POW. A group of conscientious NCO's, which included Harold, took over all basic hospital duties whilst the Medical Officers were being held in solitary confinement; these men have always been regarded as unsung heroes by the other survivors from the jail, especially as they put themselves at risk of catching all sorts of diseases whilst carrying out this work, none more so than during the cholera outbreak of June 1944. The Japanese, for no valid reason, kept Major Ramsay, the Senior Medical Officer for the Chindits in solitary confinement for many weeks after his capture; there can be no doubt that this action cost the lives of many Chindit soldiers including my own grandfather.

Sgt. Harold Palmer was liberated on the 29th April 1945 at a place called Waw, located close to the Burmese town of Pegu. Former Chindit officer, Lieutenant Alec Gibson explains how the prisoners found themselves in this predicament at that particular time:

Eventually in April 1945, the Japs decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 of us were classified as fit to march and on the 24th of April we marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and crippled. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, we were north of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge, when we ran into the 14th Army. The Jap Commandant left us in a village, told us we were free and disappeared with the rest of the guards. We were in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. That night we managed to contact our own troops, the West Yorkshire's, and were released.

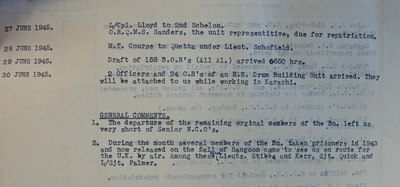

Most Chindits were flown back to hospital in Calcutta and from there were released to re-join their former units. Harold visited the 13th King's in late June 1945 at their barracks in Karachi, before being repatriated to the United Kingdom later in the year.

From reading through Harold's diary, I noticed that he was heavily involved in assisting with the medical needs of the wounded and ill inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail during his time as a POW. A group of conscientious NCO's, which included Harold, took over all basic hospital duties whilst the Medical Officers were being held in solitary confinement; these men have always been regarded as unsung heroes by the other survivors from the jail, especially as they put themselves at risk of catching all sorts of diseases whilst carrying out this work, none more so than during the cholera outbreak of June 1944. The Japanese, for no valid reason, kept Major Ramsay, the Senior Medical Officer for the Chindits in solitary confinement for many weeks after his capture; there can be no doubt that this action cost the lives of many Chindit soldiers including my own grandfather.

Sgt. Harold Palmer was liberated on the 29th April 1945 at a place called Waw, located close to the Burmese town of Pegu. Former Chindit officer, Lieutenant Alec Gibson explains how the prisoners found themselves in this predicament at that particular time:

Eventually in April 1945, the Japs decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 of us were classified as fit to march and on the 24th of April we marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and crippled. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, we were north of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge, when we ran into the 14th Army. The Jap Commandant left us in a village, told us we were free and disappeared with the rest of the guards. We were in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. That night we managed to contact our own troops, the West Yorkshire's, and were released.

Most Chindits were flown back to hospital in Calcutta and from there were released to re-join their former units. Harold visited the 13th King's in late June 1945 at their barracks in Karachi, before being repatriated to the United Kingdom later in the year.

There now follows a transcription of Harold Palmer's diary, written from notes he kept whilst a prisoner in Rangoon Jail. Keeping such notes in the jail was a punishable offence and could well of resulted in a severe beating or possibly worse. The diary was transcribed by Harold's son-in-law, Bernard Gee, who has attempted to remain true to the original text wherever possible. Some words and phrases had become too faint to decipher and in these cases have been replaced by postulations contained in brackets. I have also added annotated notes to further illustrate incidents mentioned in the text.

The Diary of Harold Palmer

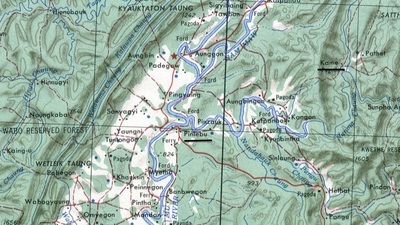

Tarzan has nothing on me and he didn’t carry a pack. If anyone asks me to go for a walk when I get back, they’ll be in danger of assault. We’d crossed the Chindwin River[1] (I swam it just for fun), then trotted about the country, sometimes facing the Japs, sometimes running away from them. Two ambushes[2] we ran into and out of, very lucky. The Japs are about the world’s worst shot (thank goodness). Then we crossed the Irrawaddi by boat a few miles below Katha. Then long after, decided to get out and we made our way back to the Waddi[3], but the Japs were waiting for us and had taken all boats so we had to split up and get back best way we could.

Our Colonel struck north to cross the Shweli River. The idea was to get a rope across and use RAF rubber boats making a ferry over. Four volunteers were detailed, two Privates, a Captain and myself. We pumped up the boat, put in the rope and one man sat in the boat paying out the rope attached to the tree, the others of us in the water swimming the boat across. The time was between 9 and 10 at night, no moon, dark as a pit; the current strong and dark as ink, the river being narrow and yet we were swept 500 yards downstream before we reached the opposite bank. Thick jungle on the other side, but what was waiting there? I guess we didn’t think of that, we were too busy getting the boat in.

I volunteered to take the boat back. The arrangement had been for the boat to be pulled back from the first bank, however, the length of the rope and the strength of the current was too much for the lads on the bank and so the boat was swung out into the middle of the current and the water was slopping angrily on the base of the boat. I felt the tug on the rope as the lads pulled, but no progress was made. Twice I got out of the boat to try swimming against the current with the aid of the rope, but although the rope was as taut as a bow string, the current kept pushing me under, so back I went in to the boat. I then untied the boat from the rope and commenced pulling myself in hand over hand. Well, I’d only the current, the weight of the boat and myself to pull along, so I did it in 1½ hours; finishing up with a knot in my shoulders like Popeye’s and no skin on my fingers.

By the time I’d landed, the other party had levelled up the rope to the point opposite and the crossing began, merry but ever so quietly. The Captain and I were still doing water traffic cops at 2am when I said to him “Do you see what I see”, and against the pitch black of the river, two blurs went sailing down the river. It was the two rubber boats, loaded with men and equipment, going the wrong way. How and what he said, I can’t repeat, but I agreed with him whole heartedly. With a current like that, we expected them to be swept in to the main Waddi stream in a couple of hours.

"No more boats, get down (and get plenty of sleep y’know). If there’s no sign of the boats, wait 48 hours for the rest of the column. If we get an air drop, we’ll try to direct the plane to you (orders from CO Major Scott) and Good Luck”. I don’t think I realised then, when I saw those boats sailing down the river at two o’clock in the morning, how it would affect events over the next few years.

As far as I know, out of 30 in our party over the river, three got out, four are with me, the remainder killed in the jungle (two were poisoned by Burmese) or died in the jail. Such is the (way) of war.

We crossed the Waddi on April 7th (leading) No. 1 Section. I took five volunteers into a village to get food and we got boats as well. But do you know, I don’t think I was at all scared going into that village that night. I had a hunch we’d be ok, with a grenade in my belt and one up the spout of my rifle. It was dark and quiet the remainder of the night. Leuty[4] had gone to the right to be ready to make a getaway should we meet trouble, but God was good; whereas I have learned since that our patrols had been to the village before and after us. They had been fired at by the Japs, I guess the Japs must have been out searching for us, No. 1 Section, that night, and God was with us.

When we got across the Waddi (at Zinbon), we thought our troubles were over, a mere 120 miles to go, but the day after, something hit me right between the eyes and I became weak as a kitten, heat stroke I suppose. The lads carried my pack and rifle and let me make the pace or else I might have been an also ran. Five days after, 90 miles from safety, we met our Waterloo. Burmese led a patrol of Japs in to us and three were killed, five taken prisoner (myself included), the rest skinned out, five being captured three days later. The four captured with me had attempted a defence while the officers and the others made for the other side of a small river, but after a few shots their rifles jammed (no oil) and bobs your uncle. The other officer[5] had one in the back and I was dressing it as best I could (he was in pain I guess). Two bony looking Japs were standing over me, bayonets fixed, grunting like pigs. I suppose having no rifle is why I’m alive today. Otherwise – who knows?

Two were wounded; one had a couple of shots in the leg. They brought him to the HQ on a stretcher. I wouldn’t have taken out a life policy just about that time. We’d heard of the Japs before, but life and hope go together. We were taken for the third degree (interrogation), 2 or 3 hours at a time, very pleasant! If you don’t tell them the truth, no food, thanks a lot! Well, I was on my chin strap and didn’t care much what happened, but when they started ill-treating the wounded, I guess I just had to stand up and sing. Afterwards we were treated quite reasonably.

The fast was broken by the Jap Captain giving me three bananas, which we duly shared. He questioned the men of course, even asked them what kind of NCO I was. There was this plug ugly Jap who took quite a fancy to me. He used to come down first thing in the morning and take me down for a wash and swim in the river. We were given time for PT and they brought us (jaggery[6]) made from palm trees, soap, coconuts and our money they took from us. Of course by that time we were fairly lousy (big ones unlimited). Trotting around the jungle with no change of clothing and no chance of a wash, our things make for just the feather beds for lice. I could have cried the first time I found out I was lousy. However after seven days, we were taken to Maymyo,[7] where we found other POW’s including the unlucky boat party (everyone of that party died in jail in Rangoon). Just before the monsoons in May, 100 of us were sent to Rangoon prison, where 300 men from the 1942 campaign had already done 18 months. My God, I thought, I’ll never do that long.

At Maymyo, the Japs amputated a leg from Corporal Usher[8] of Wrexham, and an arm from Pte. Roche[9] of Liverpool. They took them from the cells one morning to the general hospital and brought them back again on stretchers, and were putting them into a cell again – already eight of us in a 10ft x 10ft cell, when I suggested that another cell could be used. Our own interpreter asked the Japs and they saw the light, but all the cells were full, but they opened a disused block and put the two boys in a dirty cell and gave them six bananas. I got to sleep with ‘em (sometimes the Japs were quite reasonable). Because I had been doing the dirty medical work for the Japs when they dressed the wounded on the way to Maymyo, I volunteered. Those wounds have a lousy stink, and the Japs, even with their proverbial gauze masks, had me take off the old bandages before they treated the wounds. They were very short of medical kit. Those boys suffered terrible nerve pains and for a few nights there wasn’t much peace for them.

Every alternate day, the wounded were taken to the hospital for treatment, and I was always dragged in to take off the used bandages. Thank God I wasn’t squeamish, and I hope I didn’t bungle too much. When I first saw the amputations I was amazed; just like a piece of meat ready for roasting, the doctor had just cut across the limb as if it was a piece of bacon. No skin had been rolled back, as I imagined it should have been, however both operations proved successful. As I was doing nursemaid duties for the two injured lads, I was left alone by the sentries who, in most cases, treated the injured quite well, even giving them cigs, except that they all laughed when they knew that the injuries had been caused by their bullets (sadists to a man!).

The remainder of the POW’s had PT morning and night, and work parties during the day, usually digging air raid trenches. We were getting regular visits by B25’s (USAAF Mitchell Bombers) and boy did those Japs run when they heard a plane. They may be fanatics and die glorious deaths on the battlefield, but they were always off the mark when it comes to our planes. We didn’t let them see how pleased we were of course.

Still at Maymyo, they began our education to teach us discipline etc. How to Kimkie (stand to attention,) Gasume (stand at ease), Kuki (rest), Mia suisme (quick march), Mare origui (about turn), Misque (right turn), Hidari hedam (left turn), Tamarri (halt), Clota mathi (stop there), Kasara (salute), Naea (to the front), Keri (bow), Chotoria (goose step). Did we have them? The Japs think that if you cannot understand their language, if they knock one about sufficiently, one will soon learn. I had to number in Japanese too. Of course, one way of overcoming that difficulty is to make sure each man fell in in the same place in your squad each time so he’d only one number to remember, this saved a lot of slapping’s.

We had to join the Japs in their prayer meeting to the rising sun and bow at the end. The Jap in charge of our section saw that I didn’t bow, so he made sure I’d bow in future. But to save my soul I’d hum as I bowed! May the Lord look sideways on you! Of course some didn’t pick up the lingo very well and caused themselves to be slapped. But when a certain prisoner was put in charge of our Section and having a memory microscopical, he’d give the wrong word of command, then the Jap would come round the squad and slap us up, either by hand or with a stick, bamboo or rifle, whichever was handiest. You can guess how popular this dopey Section leader was with the boys. Many words of praise were hurled at him. Even when we wrote them down for him, he’d still forget as soon as he put the paper away (no names – no pack drill).

My additional notes:

[1] 8 Column crossed the Chindwin River close to the Burmese village of Tonhe (Tun-hey).

[2] One of these skirmishes with the Japanese was on the Pinlebu-Kame motor road on the 6th March 1943.

[3] Wingate and his HQ with 7&8 Columns attempted to re-cross the Irrawaddy River at a place called Inywa on the 29th March.

[4] I think this might be slang for Lieutenant?

[5] This was possibly Lieutenant Edward Hobday (see photograph below). The other Lieutenant, Edwin Horton was not reported as having been wounded.

[6] This is unclear, however, ‘jagri’ was a form of unrefined sugar and eaten as a sweet.

[7] Maymyo was a hill station town close to Mandalay. Government officials and the military used to travel to Maymyo in the hot season due to its fresher air and climate.

[8] John Albert Usher (see photograph below).

[9] William Roche a 142 Commando from 5 Column, who died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail.

Shown below is another gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The Diary of Harold Palmer

Tarzan has nothing on me and he didn’t carry a pack. If anyone asks me to go for a walk when I get back, they’ll be in danger of assault. We’d crossed the Chindwin River[1] (I swam it just for fun), then trotted about the country, sometimes facing the Japs, sometimes running away from them. Two ambushes[2] we ran into and out of, very lucky. The Japs are about the world’s worst shot (thank goodness). Then we crossed the Irrawaddi by boat a few miles below Katha. Then long after, decided to get out and we made our way back to the Waddi[3], but the Japs were waiting for us and had taken all boats so we had to split up and get back best way we could.

Our Colonel struck north to cross the Shweli River. The idea was to get a rope across and use RAF rubber boats making a ferry over. Four volunteers were detailed, two Privates, a Captain and myself. We pumped up the boat, put in the rope and one man sat in the boat paying out the rope attached to the tree, the others of us in the water swimming the boat across. The time was between 9 and 10 at night, no moon, dark as a pit; the current strong and dark as ink, the river being narrow and yet we were swept 500 yards downstream before we reached the opposite bank. Thick jungle on the other side, but what was waiting there? I guess we didn’t think of that, we were too busy getting the boat in.

I volunteered to take the boat back. The arrangement had been for the boat to be pulled back from the first bank, however, the length of the rope and the strength of the current was too much for the lads on the bank and so the boat was swung out into the middle of the current and the water was slopping angrily on the base of the boat. I felt the tug on the rope as the lads pulled, but no progress was made. Twice I got out of the boat to try swimming against the current with the aid of the rope, but although the rope was as taut as a bow string, the current kept pushing me under, so back I went in to the boat. I then untied the boat from the rope and commenced pulling myself in hand over hand. Well, I’d only the current, the weight of the boat and myself to pull along, so I did it in 1½ hours; finishing up with a knot in my shoulders like Popeye’s and no skin on my fingers.

By the time I’d landed, the other party had levelled up the rope to the point opposite and the crossing began, merry but ever so quietly. The Captain and I were still doing water traffic cops at 2am when I said to him “Do you see what I see”, and against the pitch black of the river, two blurs went sailing down the river. It was the two rubber boats, loaded with men and equipment, going the wrong way. How and what he said, I can’t repeat, but I agreed with him whole heartedly. With a current like that, we expected them to be swept in to the main Waddi stream in a couple of hours.

"No more boats, get down (and get plenty of sleep y’know). If there’s no sign of the boats, wait 48 hours for the rest of the column. If we get an air drop, we’ll try to direct the plane to you (orders from CO Major Scott) and Good Luck”. I don’t think I realised then, when I saw those boats sailing down the river at two o’clock in the morning, how it would affect events over the next few years.

As far as I know, out of 30 in our party over the river, three got out, four are with me, the remainder killed in the jungle (two were poisoned by Burmese) or died in the jail. Such is the (way) of war.

We crossed the Waddi on April 7th (leading) No. 1 Section. I took five volunteers into a village to get food and we got boats as well. But do you know, I don’t think I was at all scared going into that village that night. I had a hunch we’d be ok, with a grenade in my belt and one up the spout of my rifle. It was dark and quiet the remainder of the night. Leuty[4] had gone to the right to be ready to make a getaway should we meet trouble, but God was good; whereas I have learned since that our patrols had been to the village before and after us. They had been fired at by the Japs, I guess the Japs must have been out searching for us, No. 1 Section, that night, and God was with us.

When we got across the Waddi (at Zinbon), we thought our troubles were over, a mere 120 miles to go, but the day after, something hit me right between the eyes and I became weak as a kitten, heat stroke I suppose. The lads carried my pack and rifle and let me make the pace or else I might have been an also ran. Five days after, 90 miles from safety, we met our Waterloo. Burmese led a patrol of Japs in to us and three were killed, five taken prisoner (myself included), the rest skinned out, five being captured three days later. The four captured with me had attempted a defence while the officers and the others made for the other side of a small river, but after a few shots their rifles jammed (no oil) and bobs your uncle. The other officer[5] had one in the back and I was dressing it as best I could (he was in pain I guess). Two bony looking Japs were standing over me, bayonets fixed, grunting like pigs. I suppose having no rifle is why I’m alive today. Otherwise – who knows?

Two were wounded; one had a couple of shots in the leg. They brought him to the HQ on a stretcher. I wouldn’t have taken out a life policy just about that time. We’d heard of the Japs before, but life and hope go together. We were taken for the third degree (interrogation), 2 or 3 hours at a time, very pleasant! If you don’t tell them the truth, no food, thanks a lot! Well, I was on my chin strap and didn’t care much what happened, but when they started ill-treating the wounded, I guess I just had to stand up and sing. Afterwards we were treated quite reasonably.

The fast was broken by the Jap Captain giving me three bananas, which we duly shared. He questioned the men of course, even asked them what kind of NCO I was. There was this plug ugly Jap who took quite a fancy to me. He used to come down first thing in the morning and take me down for a wash and swim in the river. We were given time for PT and they brought us (jaggery[6]) made from palm trees, soap, coconuts and our money they took from us. Of course by that time we were fairly lousy (big ones unlimited). Trotting around the jungle with no change of clothing and no chance of a wash, our things make for just the feather beds for lice. I could have cried the first time I found out I was lousy. However after seven days, we were taken to Maymyo,[7] where we found other POW’s including the unlucky boat party (everyone of that party died in jail in Rangoon). Just before the monsoons in May, 100 of us were sent to Rangoon prison, where 300 men from the 1942 campaign had already done 18 months. My God, I thought, I’ll never do that long.

At Maymyo, the Japs amputated a leg from Corporal Usher[8] of Wrexham, and an arm from Pte. Roche[9] of Liverpool. They took them from the cells one morning to the general hospital and brought them back again on stretchers, and were putting them into a cell again – already eight of us in a 10ft x 10ft cell, when I suggested that another cell could be used. Our own interpreter asked the Japs and they saw the light, but all the cells were full, but they opened a disused block and put the two boys in a dirty cell and gave them six bananas. I got to sleep with ‘em (sometimes the Japs were quite reasonable). Because I had been doing the dirty medical work for the Japs when they dressed the wounded on the way to Maymyo, I volunteered. Those wounds have a lousy stink, and the Japs, even with their proverbial gauze masks, had me take off the old bandages before they treated the wounds. They were very short of medical kit. Those boys suffered terrible nerve pains and for a few nights there wasn’t much peace for them.

Every alternate day, the wounded were taken to the hospital for treatment, and I was always dragged in to take off the used bandages. Thank God I wasn’t squeamish, and I hope I didn’t bungle too much. When I first saw the amputations I was amazed; just like a piece of meat ready for roasting, the doctor had just cut across the limb as if it was a piece of bacon. No skin had been rolled back, as I imagined it should have been, however both operations proved successful. As I was doing nursemaid duties for the two injured lads, I was left alone by the sentries who, in most cases, treated the injured quite well, even giving them cigs, except that they all laughed when they knew that the injuries had been caused by their bullets (sadists to a man!).

The remainder of the POW’s had PT morning and night, and work parties during the day, usually digging air raid trenches. We were getting regular visits by B25’s (USAAF Mitchell Bombers) and boy did those Japs run when they heard a plane. They may be fanatics and die glorious deaths on the battlefield, but they were always off the mark when it comes to our planes. We didn’t let them see how pleased we were of course.

Still at Maymyo, they began our education to teach us discipline etc. How to Kimkie (stand to attention,) Gasume (stand at ease), Kuki (rest), Mia suisme (quick march), Mare origui (about turn), Misque (right turn), Hidari hedam (left turn), Tamarri (halt), Clota mathi (stop there), Kasara (salute), Naea (to the front), Keri (bow), Chotoria (goose step). Did we have them? The Japs think that if you cannot understand their language, if they knock one about sufficiently, one will soon learn. I had to number in Japanese too. Of course, one way of overcoming that difficulty is to make sure each man fell in in the same place in your squad each time so he’d only one number to remember, this saved a lot of slapping’s.

We had to join the Japs in their prayer meeting to the rising sun and bow at the end. The Jap in charge of our section saw that I didn’t bow, so he made sure I’d bow in future. But to save my soul I’d hum as I bowed! May the Lord look sideways on you! Of course some didn’t pick up the lingo very well and caused themselves to be slapped. But when a certain prisoner was put in charge of our Section and having a memory microscopical, he’d give the wrong word of command, then the Jap would come round the squad and slap us up, either by hand or with a stick, bamboo or rifle, whichever was handiest. You can guess how popular this dopey Section leader was with the boys. Many words of praise were hurled at him. Even when we wrote them down for him, he’d still forget as soon as he put the paper away (no names – no pack drill).

My additional notes:

[1] 8 Column crossed the Chindwin River close to the Burmese village of Tonhe (Tun-hey).

[2] One of these skirmishes with the Japanese was on the Pinlebu-Kame motor road on the 6th March 1943.

[3] Wingate and his HQ with 7&8 Columns attempted to re-cross the Irrawaddy River at a place called Inywa on the 29th March.

[4] I think this might be slang for Lieutenant?

[5] This was possibly Lieutenant Edward Hobday (see photograph below). The other Lieutenant, Edwin Horton was not reported as having been wounded.

[6] This is unclear, however, ‘jagri’ was a form of unrefined sugar and eaten as a sweet.

[7] Maymyo was a hill station town close to Mandalay. Government officials and the military used to travel to Maymyo in the hot season due to its fresher air and climate.

[8] John Albert Usher (see photograph below).

[9] William Roche a 142 Commando from 5 Column, who died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail.

Shown below is another gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Harold's diary concludes:

A young officer was brought in badly wounded. He had a wound through the fleshy part of his thigh one inch in diameter. It hadn’t been dressed for four days. When he came with us to the hospital the Jap cleared out the theatre while I took the wrapping off. When the wound had been cleaned it was possible to look from one side of his leg through the hole to the other. We tried to get a mattress for him in his cell, but the Ghurkha who went across to the other block for it, forgot to bow to the Sentry as he passed. The Sentry hit him, then one or two more joined in, sticks and all, and I’ll say he took it like a man, even though his knees buckled once or twice, he was still on his feet when the bastards had finished. The game ended and the Lieutenant was put in his cell apart from some ugly weal’s on his body, he was okay in a few days.

The Japs seemed to think I was RAMC[10] or something for nearly all the wants of the wounded were attended to by me. I enjoyed being of use and my days were busy and full. First aid training of my youthful days and common sense, proved useful. We only had one pair of crutches and leg patients took it in turn for exercise. Most of the wounded showed an amazing fortitude and high spirits which made me proud to be an Englishman.

The young wounded office had guts. The Japs took him for interrogation one day and brought me to help him to the office. Three hours later I was told to collect him. He had burns to the bone on one hand, a nasty gash on his forehead and they’d tried the water torture on him. This was on top of that terrible thigh wound; he was all in. I got a crack on my head for expressing my thoughts and told not to speak. He whispered to me “the bastards are trying to kill me” as I left him in a solitary cell. He never recovered. He was only a boy, 19 years and 6 months old. He died in Rangoon Jail a few weeks later, but he showed the Japs something they’ll never understand, that heroes are born, not made by racial fanaticism. Lt. Kirkpatrick[11], an officer from a Ghurkha battalion. My hats off to him! God rest him!

One prisoner was brought in to Maymyo, three days later he was dead; malnutrition, a walking skeleton, and he was the first to die. When we left for Rangoon, we left another boy dying; too bad to travel. The Japs had no high-powered drugs to give him and my knowledge was very limited. The journey by rail to Rangoon; 20 men to a goods van with the Jap officer having an iron bedstead for his comfort, it took up a lot of room. This stretcher case requested some more space, and the conduct of some of the officers and gentlemen we had with us was a disgrace to the name of England; perhaps they’ll blush if they ever read these words. They forced the stretcher case, the leg amputation scarcely 14 days since operation to lie on the floor cos they said his stretcher took up too much room. His wound received a knock that night which gave him agony all the next day, but the next night he slept in his stretcher in the van. Yes one of two of the NCO’s hadn’t lost their decency. I think even the Japs were disgusted.

One or two men were suffering from dysentery and on reaching Rangoon, they succumbed. Three died in the first three days. I went on the funeral party: four men, one NCO and one officer; the body stitched in a blanket, bound in a stretcher, carried in a tanga[12] while the remainder of the party got in another. Those that couldn’t get in that tanga went in with the corpse, two Jap guards, and away through the streets of Rangoon to the cemetery. Rangoon, a dead city, damaged and an air of desolation; weeds everywhere. No happy faces, only sullen looks. Here an Indian salutes, but you can see it’s not the Japs he salutes. The cemetery[13] itself was typical of the Jap neglect, overrun with weeds and decay. We laid the body under the shade of a tree and then set to dig the bone hard clay. “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust”, the guards salute the body and the officers recite the funeral service. We cover the remains of our comrade with hearts full of grim thoughts. Another spot of earth which is forever England. We set his rough cross on the grave and return with heavy hearts. This routine became a daily occurrence.

Every day death took another, sometimes two, then four one day, and nothing we could do to prevent it. Medicine scarce, disinfectant almost nil with flies everywhere, sanitation hopeless. The dark despair of those days is hard to put down on paper. Beri Beri was responsible for most deaths in those early days. The diet of rice and little vegetables did nothing to help. The Japs began to get concerned over the death rate and tried to cooperate, but they expected wonders to be done with the little medicines they gave us. A RAMC Colonel[14] in the other prison block was allowed to visit our compound about once a fortnight, but he was terrifically handicapped by lack of equipment, but he gave us advice of the treatment of the various diseases, but still the death rate mounted.

Jungle sores of terrible sizes were seen everywhere. We had 68 cases out of the 160 Chindits at one time. A small cut developed rapidly to a deadly one; painful and the stench was terrible. The lads who volunteered for the job of orderlies were real heroes. The sights they saw, the filth that surrounded them, the lack of gauze, bandages and proper equipment would have broken the hearts of experienced orderlies. So is it strange how many of these voluntary orderlies died in jail. (Greater care hath no man, consciously or unconsciously).

We got to know our Medical Officer, Major Ramsey RAMC had been taken prisoner and we began to pray for the time he came out of solitary confinement where he was. The day he came out, he assumed a load of responsibility which would have crushed most men, but many men owe their lives to Major Ramsey’s skills and work. Often he must have felt like throwing in the sponge, so little help was given by the Japs. But he stuck grimly to the task that would sicken most medicine men, and by the beginning of 1945, he in conjunction with Colonel McKenzie had disease to a minimum. They even fought a cholera outbreak[15] when everyone feared the worst; 14 deaths in two days, and yet they stamped it out with the most primitive weapon with which to fight the dreaded plague.

They performed an amputation of an arm off an airman[16], with a penknife and cotton and needle (satisfactorily). The difficulties under which they worked are known only to themselves, used as they were to the best equipment and the world reduced to surgery and medicine of hundreds of years ago.

These men proved their worth. And now the other side…

The brief sketch above was the grim side of prison life, but you can’t keep good men down, and things became better organised when Major Ramsay took over and we had the benefit of the 1942 prisoners knowledge at our disposal. Cooking improved, and the spirit of the men rose. Other prisoners came in and the news varied from good to excellent. Deaths still occurred but not with the former frequency. Of course, the weakest had dropped out and the people left were reasonably fit and very lively.

Working Parties

The Japs have a very low opinion of the average Englishman’s practical ability, believing he is carried about by servants in civil life and hardly lifting a hand for himself. When they gave us jobs, we just acted stupidly and they’d do it for us, but of course they got wise to that. My first job under the Japs was straightening nails. It wasn’t because they were thrifty times because they hadn’t any new ones. We dug air raid trenches by the dozens, the job depending on who was in charge. Bull Frog[17] was slap-happy, he hated the English and took every opportunity to slap prisoners. He (Bull Frog) was a strong Jap and typical sadist. Often we’d find a dog strung up by its neck; its feet just touching the floor when we arrived to work next morning.

Work parties went off on hunts to get news, and if we had reasonable Japs, work wasn’t too hard. But towards the end of August 1944, coolie labour began to be hard to find and Japs started working us harder. The job was first of all to dig a pit about 20 yards square, with 10 yard wings and 25 feet deep. The method of work was a few men with tools loosening the earth, others shovelling into baskets, the remainder in pairs with a bamboo pole on their shoulders with a basket in which to carry earth. We trotted up and down the sloping planks and as the rains were still on, we had a merry time keeping our balance. The Japs stood on the edge of the pit nattering all the time, occasionally coming down to slap someone who they thought was slacking or they would just throw lumps of clay or stones at ‘em.

Then another morning we’d be bailing out water instead of digging; they had no pumps. Then huge logs of teak were hauled into place by hand and block tackle, and an underground headquarters was built, and then commenced the job of filling in. And now we were taking earth back by the same method as we took it out. The Japs decided to give us a task of covering so much of the shelter per day. Of course we did it easily ‘cos we could go back (and reduce the area), when we finished and although they measured it, we fooled them. Then they decided the task should be so many cubic meters of earth removed and they’d measure a plot of ground and tell us to dig to a certain depth and when we’d finished, they’d measure it to make sure we hadn’t bugged them. The tasks became harder and harder, but we managed to pull the pegs in now and again.

At this time we were having to eat breakfast before dawn and start work as dawn broke. We had a break (Gasume) during the morning and our cooks made the vegetable soup on the job, and we had this for the meal. Another Gasume[18] in the afternoon and we finished sometimes getting back home and suppering in the dark.

My additional notes:

[10] Royal Army Medical Corps.

[11] Lieutenant William George Kirkpatrick of 3/5 Gurkha Rifles.

[12] A type of horse-drawn carriage. In this case of course there was no horse.

[13] The English Cantonment Cemetery in the eastern sector of the city, close to the Royal Lakes.

[14] Colonel Kenneth Pirie MacKenzie RAMC.

[15] This outbreak occurred in late June 1944.

[16] American Flight Sergeant Richard A. Montgomery of Riverside California.

[17] Nickname of a Japanese Guard at Rangoon Jail.

[18] Different spelling of the word Yasumis, meaning rest period or rest day.

Here is where Harold Palmer's short, but nevertheless most interesting diary ends. Seen below are some more images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

A young officer was brought in badly wounded. He had a wound through the fleshy part of his thigh one inch in diameter. It hadn’t been dressed for four days. When he came with us to the hospital the Jap cleared out the theatre while I took the wrapping off. When the wound had been cleaned it was possible to look from one side of his leg through the hole to the other. We tried to get a mattress for him in his cell, but the Ghurkha who went across to the other block for it, forgot to bow to the Sentry as he passed. The Sentry hit him, then one or two more joined in, sticks and all, and I’ll say he took it like a man, even though his knees buckled once or twice, he was still on his feet when the bastards had finished. The game ended and the Lieutenant was put in his cell apart from some ugly weal’s on his body, he was okay in a few days.

The Japs seemed to think I was RAMC[10] or something for nearly all the wants of the wounded were attended to by me. I enjoyed being of use and my days were busy and full. First aid training of my youthful days and common sense, proved useful. We only had one pair of crutches and leg patients took it in turn for exercise. Most of the wounded showed an amazing fortitude and high spirits which made me proud to be an Englishman.

The young wounded office had guts. The Japs took him for interrogation one day and brought me to help him to the office. Three hours later I was told to collect him. He had burns to the bone on one hand, a nasty gash on his forehead and they’d tried the water torture on him. This was on top of that terrible thigh wound; he was all in. I got a crack on my head for expressing my thoughts and told not to speak. He whispered to me “the bastards are trying to kill me” as I left him in a solitary cell. He never recovered. He was only a boy, 19 years and 6 months old. He died in Rangoon Jail a few weeks later, but he showed the Japs something they’ll never understand, that heroes are born, not made by racial fanaticism. Lt. Kirkpatrick[11], an officer from a Ghurkha battalion. My hats off to him! God rest him!

One prisoner was brought in to Maymyo, three days later he was dead; malnutrition, a walking skeleton, and he was the first to die. When we left for Rangoon, we left another boy dying; too bad to travel. The Japs had no high-powered drugs to give him and my knowledge was very limited. The journey by rail to Rangoon; 20 men to a goods van with the Jap officer having an iron bedstead for his comfort, it took up a lot of room. This stretcher case requested some more space, and the conduct of some of the officers and gentlemen we had with us was a disgrace to the name of England; perhaps they’ll blush if they ever read these words. They forced the stretcher case, the leg amputation scarcely 14 days since operation to lie on the floor cos they said his stretcher took up too much room. His wound received a knock that night which gave him agony all the next day, but the next night he slept in his stretcher in the van. Yes one of two of the NCO’s hadn’t lost their decency. I think even the Japs were disgusted.

One or two men were suffering from dysentery and on reaching Rangoon, they succumbed. Three died in the first three days. I went on the funeral party: four men, one NCO and one officer; the body stitched in a blanket, bound in a stretcher, carried in a tanga[12] while the remainder of the party got in another. Those that couldn’t get in that tanga went in with the corpse, two Jap guards, and away through the streets of Rangoon to the cemetery. Rangoon, a dead city, damaged and an air of desolation; weeds everywhere. No happy faces, only sullen looks. Here an Indian salutes, but you can see it’s not the Japs he salutes. The cemetery[13] itself was typical of the Jap neglect, overrun with weeds and decay. We laid the body under the shade of a tree and then set to dig the bone hard clay. “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust”, the guards salute the body and the officers recite the funeral service. We cover the remains of our comrade with hearts full of grim thoughts. Another spot of earth which is forever England. We set his rough cross on the grave and return with heavy hearts. This routine became a daily occurrence.

Every day death took another, sometimes two, then four one day, and nothing we could do to prevent it. Medicine scarce, disinfectant almost nil with flies everywhere, sanitation hopeless. The dark despair of those days is hard to put down on paper. Beri Beri was responsible for most deaths in those early days. The diet of rice and little vegetables did nothing to help. The Japs began to get concerned over the death rate and tried to cooperate, but they expected wonders to be done with the little medicines they gave us. A RAMC Colonel[14] in the other prison block was allowed to visit our compound about once a fortnight, but he was terrifically handicapped by lack of equipment, but he gave us advice of the treatment of the various diseases, but still the death rate mounted.

Jungle sores of terrible sizes were seen everywhere. We had 68 cases out of the 160 Chindits at one time. A small cut developed rapidly to a deadly one; painful and the stench was terrible. The lads who volunteered for the job of orderlies were real heroes. The sights they saw, the filth that surrounded them, the lack of gauze, bandages and proper equipment would have broken the hearts of experienced orderlies. So is it strange how many of these voluntary orderlies died in jail. (Greater care hath no man, consciously or unconsciously).

We got to know our Medical Officer, Major Ramsey RAMC had been taken prisoner and we began to pray for the time he came out of solitary confinement where he was. The day he came out, he assumed a load of responsibility which would have crushed most men, but many men owe their lives to Major Ramsey’s skills and work. Often he must have felt like throwing in the sponge, so little help was given by the Japs. But he stuck grimly to the task that would sicken most medicine men, and by the beginning of 1945, he in conjunction with Colonel McKenzie had disease to a minimum. They even fought a cholera outbreak[15] when everyone feared the worst; 14 deaths in two days, and yet they stamped it out with the most primitive weapon with which to fight the dreaded plague.

They performed an amputation of an arm off an airman[16], with a penknife and cotton and needle (satisfactorily). The difficulties under which they worked are known only to themselves, used as they were to the best equipment and the world reduced to surgery and medicine of hundreds of years ago.

These men proved their worth. And now the other side…

The brief sketch above was the grim side of prison life, but you can’t keep good men down, and things became better organised when Major Ramsay took over and we had the benefit of the 1942 prisoners knowledge at our disposal. Cooking improved, and the spirit of the men rose. Other prisoners came in and the news varied from good to excellent. Deaths still occurred but not with the former frequency. Of course, the weakest had dropped out and the people left were reasonably fit and very lively.

Working Parties

The Japs have a very low opinion of the average Englishman’s practical ability, believing he is carried about by servants in civil life and hardly lifting a hand for himself. When they gave us jobs, we just acted stupidly and they’d do it for us, but of course they got wise to that. My first job under the Japs was straightening nails. It wasn’t because they were thrifty times because they hadn’t any new ones. We dug air raid trenches by the dozens, the job depending on who was in charge. Bull Frog[17] was slap-happy, he hated the English and took every opportunity to slap prisoners. He (Bull Frog) was a strong Jap and typical sadist. Often we’d find a dog strung up by its neck; its feet just touching the floor when we arrived to work next morning.

Work parties went off on hunts to get news, and if we had reasonable Japs, work wasn’t too hard. But towards the end of August 1944, coolie labour began to be hard to find and Japs started working us harder. The job was first of all to dig a pit about 20 yards square, with 10 yard wings and 25 feet deep. The method of work was a few men with tools loosening the earth, others shovelling into baskets, the remainder in pairs with a bamboo pole on their shoulders with a basket in which to carry earth. We trotted up and down the sloping planks and as the rains were still on, we had a merry time keeping our balance. The Japs stood on the edge of the pit nattering all the time, occasionally coming down to slap someone who they thought was slacking or they would just throw lumps of clay or stones at ‘em.

Then another morning we’d be bailing out water instead of digging; they had no pumps. Then huge logs of teak were hauled into place by hand and block tackle, and an underground headquarters was built, and then commenced the job of filling in. And now we were taking earth back by the same method as we took it out. The Japs decided to give us a task of covering so much of the shelter per day. Of course we did it easily ‘cos we could go back (and reduce the area), when we finished and although they measured it, we fooled them. Then they decided the task should be so many cubic meters of earth removed and they’d measure a plot of ground and tell us to dig to a certain depth and when we’d finished, they’d measure it to make sure we hadn’t bugged them. The tasks became harder and harder, but we managed to pull the pegs in now and again.

At this time we were having to eat breakfast before dawn and start work as dawn broke. We had a break (Gasume) during the morning and our cooks made the vegetable soup on the job, and we had this for the meal. Another Gasume[18] in the afternoon and we finished sometimes getting back home and suppering in the dark.

My additional notes:

[10] Royal Army Medical Corps.

[11] Lieutenant William George Kirkpatrick of 3/5 Gurkha Rifles.

[12] A type of horse-drawn carriage. In this case of course there was no horse.

[13] The English Cantonment Cemetery in the eastern sector of the city, close to the Royal Lakes.

[14] Colonel Kenneth Pirie MacKenzie RAMC.

[15] This outbreak occurred in late June 1944.

[16] American Flight Sergeant Richard A. Montgomery of Riverside California.

[17] Nickname of a Japanese Guard at Rangoon Jail.

[18] Different spelling of the word Yasumis, meaning rest period or rest day.

Here is where Harold Palmer's short, but nevertheless most interesting diary ends. Seen below are some more images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As mentioned by Claire in her original email contact with me, one of her main reasons for getting in touch, was to explore the possibility of sharing her grandfather's diary with the family of Pte. John Bromley. I was able to assist and the two families have spoken to each other and exchanged information and stories. In April (2016), Claire sent me the following update:

Hi Steve,

I wanted to give you an update on my conversation with Elaine, Pte. John Bromley's granddaughter. We've been chatting by email and my dad has spoken to both Elaine and her dad. I've also sent Elaine a copy of my grandad's diary.

Elaine's sister has been sorting through all the letters that John Bromley sent to his wife and we have had an interesting result, please see Elaine's email below. It seems quite amazing to me, that after I contacted you because I thought they might be interested to see Harold's diary and to learn what happened to them when the Japanese came upon them, that we have now found that there is a further link between our two Grandfathers. I think it has meant a lot to all of us.

Many thanks

Claire

In an email reply to Claire, Elaine Livesey, granddaughter of John Bromley wrote:

Dear Claire,

Hope you are all well? I've just tried ringing your Dad but no-one was in, so I left a brief message saying that my sister has just phoned me saying she has come to the end of Grandad's letters and had just come across an offical letter to my Nan from the British POW Relatives Association, dated 20th October 1945. Within the letter it says that they believe she visited Sergeant Palmer and gives an address of 13 St. Kilda's Avenue, Droylesden, and that Sergeant Palmer would be happy to give her any information she asked for, if he could do so.

So after going through all those letters it does appear that our Grandad's were together and knew each other and that my Nan may well have met up with Harold after the war. I will try and send a copy of the letter to you soon.

Take care and best wishes

Elaine

As you might imagine, I was thrilled to hear that the two families had made contact with each other and discovered their common bond in relation to their grandfather's wartime experiences; this type of outcome was what I had hoped for when I first began my research and then decided to set up my website.

Seen below is a photograph, very similar to the one shown at the head of this story, of John Bromley and some of the other members of what would become Chindit Column 8 in 1943. It is taken aboard the troopship Oronsay in early 1942, just before the battalion reached India and fate placed them into Wingate's arms.

Hi Steve,

I wanted to give you an update on my conversation with Elaine, Pte. John Bromley's granddaughter. We've been chatting by email and my dad has spoken to both Elaine and her dad. I've also sent Elaine a copy of my grandad's diary.

Elaine's sister has been sorting through all the letters that John Bromley sent to his wife and we have had an interesting result, please see Elaine's email below. It seems quite amazing to me, that after I contacted you because I thought they might be interested to see Harold's diary and to learn what happened to them when the Japanese came upon them, that we have now found that there is a further link between our two Grandfathers. I think it has meant a lot to all of us.

Many thanks

Claire

In an email reply to Claire, Elaine Livesey, granddaughter of John Bromley wrote:

Dear Claire,

Hope you are all well? I've just tried ringing your Dad but no-one was in, so I left a brief message saying that my sister has just phoned me saying she has come to the end of Grandad's letters and had just come across an offical letter to my Nan from the British POW Relatives Association, dated 20th October 1945. Within the letter it says that they believe she visited Sergeant Palmer and gives an address of 13 St. Kilda's Avenue, Droylesden, and that Sergeant Palmer would be happy to give her any information she asked for, if he could do so.

So after going through all those letters it does appear that our Grandad's were together and knew each other and that my Nan may well have met up with Harold after the war. I will try and send a copy of the letter to you soon.

Take care and best wishes

Elaine

As you might imagine, I was thrilled to hear that the two families had made contact with each other and discovered their common bond in relation to their grandfather's wartime experiences; this type of outcome was what I had hoped for when I first began my research and then decided to set up my website.

Seen below is a photograph, very similar to the one shown at the head of this story, of John Bromley and some of the other members of what would become Chindit Column 8 in 1943. It is taken aboard the troopship Oronsay in early 1942, just before the battalion reached India and fate placed them into Wingate's arms.

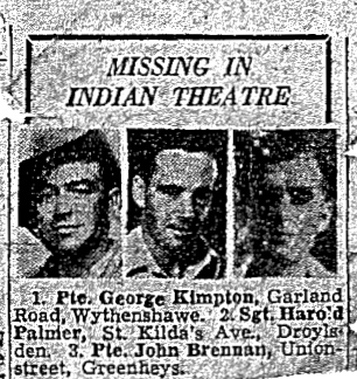

Amongst the documents and photographs sent to me by the family of Sgt. Palmer, I was intrigued to find a newspaper cutting describing the experiences and safe return of Harold, as written in the Manchester Evening Paper at some point in July 1945. There was also another smaller cutting (shown below) of Harold and two other Chindits, George Kimpton and John Brennan, who had all been reported as missing in action from the Indian theatre in 1943.

Pte. George Kimpton from Wythenshawe in Manchester, was originally enlisted into the South Lancashire Regiment, before joining the 13th King's in India and taking up a place in 7 Column on Operation Longcloth. George was captured by the Japanese at a place called Sadon (Kachin State) in early July 1943 whilst attempting to exit Burma via the Yunnan Provinces of China. Although he survived his time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail and made the journey home to Lancashire, he sadly died on the 20th May 1946, barely one year after his liberation at the village of Waw on the Pegu Road.

At the same time as George was being liberated in Burma, his wife May Kimpton placed this notice in the Manchester Evening News, dated Saturday 28th April 1945 and under the headline, Still Missing:

Pte. 3662003 George Kimpton (King's Regiment), reported missing in Burma April 29th 1943. Any news would be greatly appreciated by his wife. 55 Garland Road, Crossacres, Wythenshawe.

Pte. John Brennan from Greenheys in Manchester, was a member of Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. He was one of the original draft of soldiers that made up the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment and left British shores for India on 8th December 1941. All that is known about John and his fate as a Chindit, is that he became lost from his unit on 8th May 1943, close to a village called Haungpa on the banks of the Uyu River. He was never seen again.

Pte. George Kimpton from Wythenshawe in Manchester, was originally enlisted into the South Lancashire Regiment, before joining the 13th King's in India and taking up a place in 7 Column on Operation Longcloth. George was captured by the Japanese at a place called Sadon (Kachin State) in early July 1943 whilst attempting to exit Burma via the Yunnan Provinces of China. Although he survived his time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail and made the journey home to Lancashire, he sadly died on the 20th May 1946, barely one year after his liberation at the village of Waw on the Pegu Road.

At the same time as George was being liberated in Burma, his wife May Kimpton placed this notice in the Manchester Evening News, dated Saturday 28th April 1945 and under the headline, Still Missing:

Pte. 3662003 George Kimpton (King's Regiment), reported missing in Burma April 29th 1943. Any news would be greatly appreciated by his wife. 55 Garland Road, Crossacres, Wythenshawe.

Pte. John Brennan from Greenheys in Manchester, was a member of Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. He was one of the original draft of soldiers that made up the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment and left British shores for India on 8th December 1941. All that is known about John and his fate as a Chindit, is that he became lost from his unit on 8th May 1943, close to a village called Haungpa on the banks of the Uyu River. He was never seen again.

I would like to thank Claire McHenry and her family for their invaluable help in bringing the story of Sgt. Harold Palmer to these website pages and for allowing me to reproduce Harold's diary as part of the narrative. I can think of no better way of completing the story, than by transcribing the short article from the Manchester Evening Paper, in which Harold recounts his time in Burma and gives his opinions on the Japanese as soldiers and as men.

Home From a Japanese Prison Camp

Captured on Wingate's First Expedition

For two years and twelve days, Sgt. Harold Palmer, of 13 St. Kildas Avenue, Droylsden, was held prisoner by the Japanese. He was released by our advancing troops last April, at a point about sixty miles north of Rangoon. The memory of those two years of life in a prison camp will remain for ever.

Sgt. Palmer told the reporter that he was captured while on Wingate's first expedition into Burma in 1943. He had been training for some time in India before the expedition, and indeed says that the training period was tougher than the actual thing. After a weeks leave in Bombay, he set off in the January, crossing the Chindwin River in early February. "Our job was to act as decoy while the other troops destroyed railway communications. Although I walked 1200 miles, some of the boys did 2000 miles. On the way back the Japs took the boats from the River Irrawaddy and we had to split up and get back as best we could."

The main hardship in the prison camp was disease. Medical equipment was very scanty and only for the fine efforts of the R.A.M.C. many more men would have died. Food was of the poorest quality, but again, the Army cooks did wonders, serving better food to our boys, than the Japs themselves were having. "One day" said Sgt. Palmer, "We swotted about 14,000 flies. There was no other way of killing them. The fit men worked like coolies in loin clothes and this gave them an appetite and kept them fairly healthy."

Sgt. Palmer gives some interesting details about the Japanese themselves. "They are like little children in many ways, and are easily offended. I've seen a Jap knocking one of our lads about one day and then giving him cigarettes the next.

The Jap is a suspicious person, even about his own countrymen and kept our mail back from us for months in case there were any secret messages amongst them. It is not true as many people believe, that the Jap is superior to us in night fighting and jungle warfare. Our lads can more than hold their own with them, and indeed the Jap is not only one of the clumsiest of creatures in the jungle, but is also the world's worst shot. There was a Jap not ten yards from me when he fired and yet he missed.

It is also untrue that the Japanese are all experts in Ju-Jitsu. They had wrestling matches while I was in the camp and a third-rate wrestler in England could have licked them all. It is correct to say that the Japanese are fanatical fighters, but they experience the same fears as we do and when our planes came over, you should have seen them run for shelter."

Sgt. Palmer, who is now 33 years of age, got home last Saturday. His daughter, Jane, aged six, had rather expected her father to bring an elephant home with him, and when he arrived without it was disappointed. But she is really proud of her Daddy, and told everyone she met, that he had come home from Burma. Sgt. Palmer was employed by Lewis's in Manchester, before joining up five years ago.

Article from the Manchester Evening Paper, July 1945.

Home From a Japanese Prison Camp

Captured on Wingate's First Expedition

For two years and twelve days, Sgt. Harold Palmer, of 13 St. Kildas Avenue, Droylsden, was held prisoner by the Japanese. He was released by our advancing troops last April, at a point about sixty miles north of Rangoon. The memory of those two years of life in a prison camp will remain for ever.

Sgt. Palmer told the reporter that he was captured while on Wingate's first expedition into Burma in 1943. He had been training for some time in India before the expedition, and indeed says that the training period was tougher than the actual thing. After a weeks leave in Bombay, he set off in the January, crossing the Chindwin River in early February. "Our job was to act as decoy while the other troops destroyed railway communications. Although I walked 1200 miles, some of the boys did 2000 miles. On the way back the Japs took the boats from the River Irrawaddy and we had to split up and get back as best we could."

The main hardship in the prison camp was disease. Medical equipment was very scanty and only for the fine efforts of the R.A.M.C. many more men would have died. Food was of the poorest quality, but again, the Army cooks did wonders, serving better food to our boys, than the Japs themselves were having. "One day" said Sgt. Palmer, "We swotted about 14,000 flies. There was no other way of killing them. The fit men worked like coolies in loin clothes and this gave them an appetite and kept them fairly healthy."

Sgt. Palmer gives some interesting details about the Japanese themselves. "They are like little children in many ways, and are easily offended. I've seen a Jap knocking one of our lads about one day and then giving him cigarettes the next.

The Jap is a suspicious person, even about his own countrymen and kept our mail back from us for months in case there were any secret messages amongst them. It is not true as many people believe, that the Jap is superior to us in night fighting and jungle warfare. Our lads can more than hold their own with them, and indeed the Jap is not only one of the clumsiest of creatures in the jungle, but is also the world's worst shot. There was a Jap not ten yards from me when he fired and yet he missed.

It is also untrue that the Japanese are all experts in Ju-Jitsu. They had wrestling matches while I was in the camp and a third-rate wrestler in England could have licked them all. It is correct to say that the Japanese are fanatical fighters, but they experience the same fears as we do and when our planes came over, you should have seen them run for shelter."

Sgt. Palmer, who is now 33 years of age, got home last Saturday. His daughter, Jane, aged six, had rather expected her father to bring an elephant home with him, and when he arrived without it was disappointed. But she is really proud of her Daddy, and told everyone she met, that he had come home from Burma. Sgt. Palmer was employed by Lewis's in Manchester, before joining up five years ago.

Article from the Manchester Evening Paper, July 1945.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, May 2016.