Sergeant John Thornley

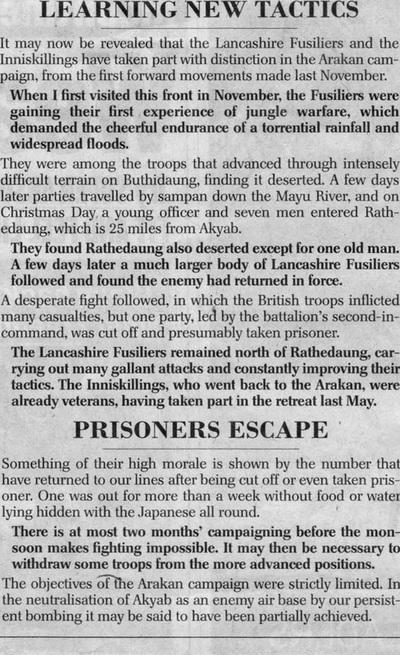

Wireless traffic during the Chindwin Crossing, February 1943.

Wireless traffic during the Chindwin Crossing, February 1943.

The image to the left can be seen in many books about the first Chindit operation in 1943 and I have often wondered which column it depicted during the crossing of the Chindwin River in February that year.

In March 2013 I received this enquiry from a Chindit Great Grandson named Jack Lewin:

Hello. I have just stumbled across your website, my great grandfather was a Chindit and we never really knew the full story of what happened to him between him getting separated from his column and him dying in Rangoon prison camp in 1944.

Reading through your site, on one of the pages, there is a story about a man from Widnes who went missing, it appears that my great grandfather, Sgt. John Thornley, was with him on the firewood collecting party. I was wondering if you had received any contact from the family of Sergeant David Glynn Hammond as it would be aweosme if we got some more information to fill in the blank spaces.

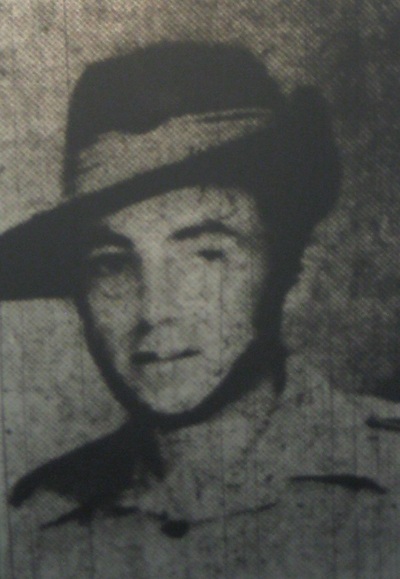

There is quite a famous photograph of my Great Grandfather sending a wireless message on the banks of the Chindwin River, it features in many books on the subject and is taken from a Ministry of War newsreel from that period.

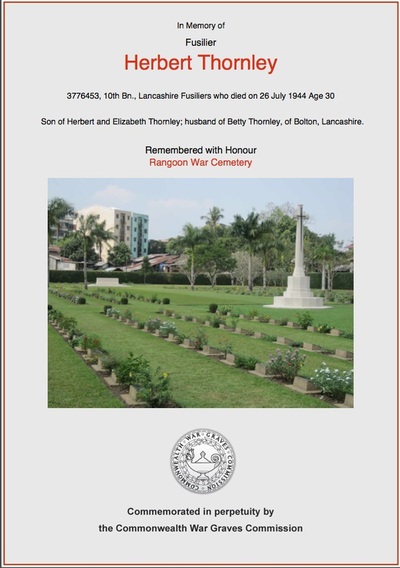

With Jack's new information came the answer to my question, as Sgt. Thornley was a member of Chindit Column 8 in 1943 and had become a prisoner of war in mid-April that year. There was also another poignancy to this story as I soon recalled from my POW records that John Thornley had met up with his own brother once inside Rangoon Jail. Herbert Thornley had been captured some months previously whilst serving in the Arakan region of Burma, I had never been totally sure that the two men were actually related, but now I had my proof.

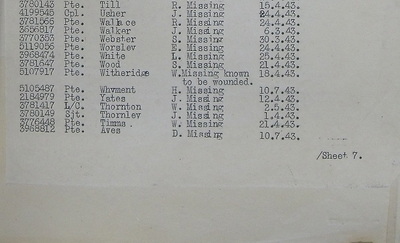

From the official Missing in Action lists for the 13th King's, held at the National Archives and found within the pages of the battalion War diary, I knew that John had been recorded as missing on the 1st April 1943. But what had actually happened to him?

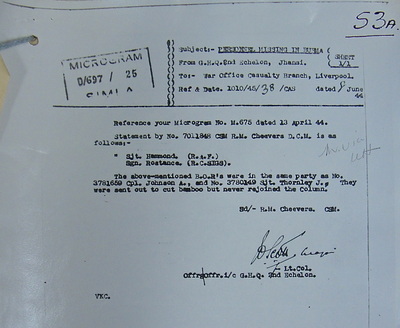

The last known whereabouts of Sgt. Thornley were recorded by CSM Richard Cheevers in a witness statement which he completed on his return to India that year, here is a transcription of that report:

In the case of Corporal A. Johnson and Sgt. J.Thornley. The following is an extract from a statement by 7011848 CSM R.M. Cheevers of Column 8. The statement covers the period 1st April 1943:

"On the 1st April, I was ordered by my Column Commander to send out a party to cut bamboo. The two missing men were so detailed. They were also accompanied by Sergeant Hammond of the RAF and Signalman Rostance. None of these men ever re-joined the Column."

A little more detail was given in another witness statement presumably also given by Richard Cheevers, held by the RAF and obtained from the Army Authorities in September 1943:

"In the case of 1414386 LAC A/SGT. D.G. Hammond. A party of four men left the Column on 1st April 1943, they were last seen on the west bank of the Shweli River opposite the village of Dochaung, where they were ordered to cut bamboo. The Column remained in this area for two days but the party failed to return. They were presumed lost and that they would attempt to return to India on their own."

It would seem that the four men had wandered away from the main unit in search of some suitable bamboo and had become lost and could not find their way back to the Column. In the dense and impenetrable Burmese jungle this was very easily done. Seen below is a photograph of Richard Cheevers taken in June 1944 during the presentation of his Distinguished Conduct Medal for services in Burma in 1943.

In March 2013 I received this enquiry from a Chindit Great Grandson named Jack Lewin:

Hello. I have just stumbled across your website, my great grandfather was a Chindit and we never really knew the full story of what happened to him between him getting separated from his column and him dying in Rangoon prison camp in 1944.

Reading through your site, on one of the pages, there is a story about a man from Widnes who went missing, it appears that my great grandfather, Sgt. John Thornley, was with him on the firewood collecting party. I was wondering if you had received any contact from the family of Sergeant David Glynn Hammond as it would be aweosme if we got some more information to fill in the blank spaces.

There is quite a famous photograph of my Great Grandfather sending a wireless message on the banks of the Chindwin River, it features in many books on the subject and is taken from a Ministry of War newsreel from that period.

With Jack's new information came the answer to my question, as Sgt. Thornley was a member of Chindit Column 8 in 1943 and had become a prisoner of war in mid-April that year. There was also another poignancy to this story as I soon recalled from my POW records that John Thornley had met up with his own brother once inside Rangoon Jail. Herbert Thornley had been captured some months previously whilst serving in the Arakan region of Burma, I had never been totally sure that the two men were actually related, but now I had my proof.

From the official Missing in Action lists for the 13th King's, held at the National Archives and found within the pages of the battalion War diary, I knew that John had been recorded as missing on the 1st April 1943. But what had actually happened to him?

The last known whereabouts of Sgt. Thornley were recorded by CSM Richard Cheevers in a witness statement which he completed on his return to India that year, here is a transcription of that report:

In the case of Corporal A. Johnson and Sgt. J.Thornley. The following is an extract from a statement by 7011848 CSM R.M. Cheevers of Column 8. The statement covers the period 1st April 1943:

"On the 1st April, I was ordered by my Column Commander to send out a party to cut bamboo. The two missing men were so detailed. They were also accompanied by Sergeant Hammond of the RAF and Signalman Rostance. None of these men ever re-joined the Column."

A little more detail was given in another witness statement presumably also given by Richard Cheevers, held by the RAF and obtained from the Army Authorities in September 1943:

"In the case of 1414386 LAC A/SGT. D.G. Hammond. A party of four men left the Column on 1st April 1943, they were last seen on the west bank of the Shweli River opposite the village of Dochaung, where they were ordered to cut bamboo. The Column remained in this area for two days but the party failed to return. They were presumed lost and that they would attempt to return to India on their own."

It would seem that the four men had wandered away from the main unit in search of some suitable bamboo and had become lost and could not find their way back to the Column. In the dense and impenetrable Burmese jungle this was very easily done. Seen below is a photograph of Richard Cheevers taken in June 1944 during the presentation of his Distinguished Conduct Medal for services in Burma in 1943.

So, what had Column 8 been up to prior to the disappearance of Sgt. Thornley and the rest of his party?

Column 8 were under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott, or 'Scottie' as he was known by his men. Scott was a very popular leader in 1943. Column 8 had stayed close to Wingate's own Brigade HQ during the operation and had the Japanese not been closing in on the Brigade by late March 1943, would have probably stayed with Wingate on his dispersal back to India. The column had been involved in several skirmishes with the Japanese at places such as Pinlebu, but in general had faired well on the operation thus far suffering few casualties.

Columns 7 and 8 along with Wingate's Head Quarters attempted to re-cross the Irrawaddy River on 29th March at a place called Inywa, but the enemy had gathered in strength on the opposite bank and the crossing was compromised with only a few boats reaching the other side. Reluctantly, Scott turned his men away from the river and moved off to the north-east.

By the 1st April the Column had reached the banks of another fast flowing Burmese river, the Shweli. Some of the Column got a power-rope across and managed to get over, but a disastrous mistake by another Sergeant led to the line being cut by mistake and the boats being swept away downstream. For more about this incident, please click on the link below:

Eric Allen and the Lost boat on the Shweli

The rest of the Column 8 had to wait in the jungle close to the river to see if the RAF could drop more dinghies, and hoped to make another attempt at crossing the following day. This is when I believe John was given the order to go out and find firewood with the other men.

John was captured on the 14th April, so he must have got lost whilst out collecting the firewood and been at large in the jungle for nearly two weeks. With no food or supplies available, other than what they could find as they marched, these four men must have been in a very poor state of health when they were eventually found by the Japanese.

The four men were sent to the main POW concentration camp at Maymyo. After this they were sent down to Rangoon Jail where John would be given the POW number 398. His brother Herbert was given the number 273, which signified his earlier capture back in December 1942.

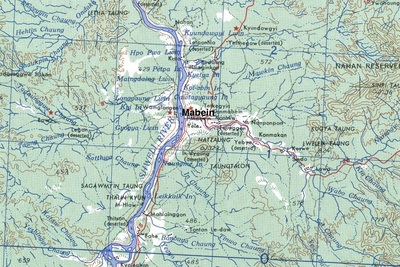

Seen below is a contemporary map from that time, showing the town of Inywa on the banks of the Irrawaddy River and diagonally opposite, the village of Dochaung on the east banks of the Shweli, where John went missing. Please click on the image to enlarge.

Column 8 were under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott, or 'Scottie' as he was known by his men. Scott was a very popular leader in 1943. Column 8 had stayed close to Wingate's own Brigade HQ during the operation and had the Japanese not been closing in on the Brigade by late March 1943, would have probably stayed with Wingate on his dispersal back to India. The column had been involved in several skirmishes with the Japanese at places such as Pinlebu, but in general had faired well on the operation thus far suffering few casualties.

Columns 7 and 8 along with Wingate's Head Quarters attempted to re-cross the Irrawaddy River on 29th March at a place called Inywa, but the enemy had gathered in strength on the opposite bank and the crossing was compromised with only a few boats reaching the other side. Reluctantly, Scott turned his men away from the river and moved off to the north-east.

By the 1st April the Column had reached the banks of another fast flowing Burmese river, the Shweli. Some of the Column got a power-rope across and managed to get over, but a disastrous mistake by another Sergeant led to the line being cut by mistake and the boats being swept away downstream. For more about this incident, please click on the link below:

Eric Allen and the Lost boat on the Shweli

The rest of the Column 8 had to wait in the jungle close to the river to see if the RAF could drop more dinghies, and hoped to make another attempt at crossing the following day. This is when I believe John was given the order to go out and find firewood with the other men.

John was captured on the 14th April, so he must have got lost whilst out collecting the firewood and been at large in the jungle for nearly two weeks. With no food or supplies available, other than what they could find as they marched, these four men must have been in a very poor state of health when they were eventually found by the Japanese.

The four men were sent to the main POW concentration camp at Maymyo. After this they were sent down to Rangoon Jail where John would be given the POW number 398. His brother Herbert was given the number 273, which signified his earlier capture back in December 1942.

Seen below is a contemporary map from that time, showing the town of Inywa on the banks of the Irrawaddy River and diagonally opposite, the village of Dochaung on the east banks of the Shweli, where John went missing. Please click on the image to enlarge.

The Thornley family provided me with some background detail about John's early life before the war, his Army training and what they knew about his time in Burma in 1943. The following information was provided by John Thornley's son, Stuart.

Jack Thornley was born at the Waterloo Hotel Blackpool, where his father was the manager, on the 28th January 1912. He was christened “John” but always known as “Jack”. He was the eldest in what was to become a family of four brothers and a sister.

In 1926 he was awarded a certificate by the “Daily Dispatch” for proficiency in a national scholarship competition. He gained his Matriculation Certificate in 1928 and got a job with the District Bank. By 1939 he had become the youngest assistant manager in the Bank's history. He married Dorothy Gray, sister of his best friend's wife Elsie, in June 1939.

He was 27 when the war broke out. As the war progressed and more troops were required, the age of conscription was steadily raised. He became eligible for call-up in 1942.

A week after his best friend (and now brother-in-law), of the same age had been conscripted, Jack went to the recruitment office to complain that he had been missed out. It was explained to him that conscripts were taken in alphabetical order and his brother-in-law's name began with a D, while his was T. Eventually he was called for a medical where he hid a recently broken collar bone in case it delayed his entry into the Army.

During training he was offered a chance to apply for a commission, which he turned down because, in his words,"the war might end before he finished the course". He trained as a Wireless Operator with the 13th King's based in Liverpool. At the end of his training he was made up to Sergeant.

The 13th King's consisted of 'old men' in their late twenties/early thirties and was originally intended for coastal defence duties in the UK. Eventually the decision was made to send the 13th King's to India to release the younger men who were there on policing duties for active service. It was while the King's Regiment were en route to India by sea that Churchill added them to a list of miscellaneous troops offered to Orde Wingate to use for his first expedition into Burma.

A good proportion of the King's men opted out during training once they realised the nature of the enterprise. Jack's letters home at that time were enthusiastic about Army life and expressed his intention to make it his career after the war ended.

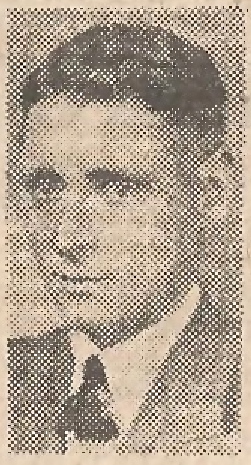

On a visit to the cinema in early 1943 Jack's wife was surprised to see him sitting by his radio in a newsreel about the Chindits. She persuaded the cinema to give her three frames of the 35mm film. The same War Office picture has been used to illustrate countless books and articles about the Chindits.

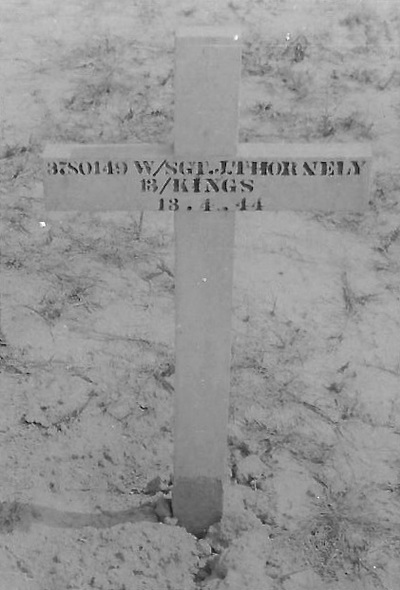

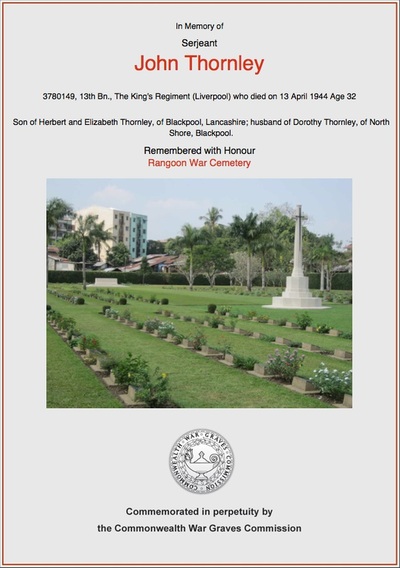

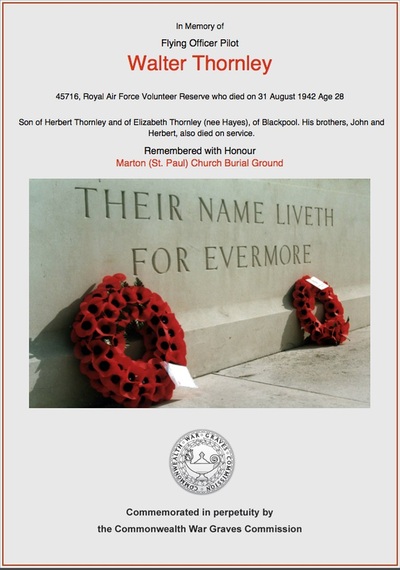

Jack was captured on 14th April 1943 and died on 13th April 1944 in Rangoon Prison. His wife was informed that he was missing on 1st April 1943 but not of his death until 6th June 1945 – his youngest brother's wedding day. The news came at the same time as that of the death of his brother Herbert, also in Rangoon Prison, and was kept from the bride and groom until they returned from honeymoon. The other brother Walter, an RAF regular, died on his first day as a test pilot in August 1942 having just returned from serving in Iraq.

Great Grandson Jack Lewin has published a very interesting website about his international cycling tour and his attempt to reach Burma on two wheels and visit amongst other places, the grave of his Great Grandfather. Please click on the link below to read more:

http://jblewi.wordpress.com

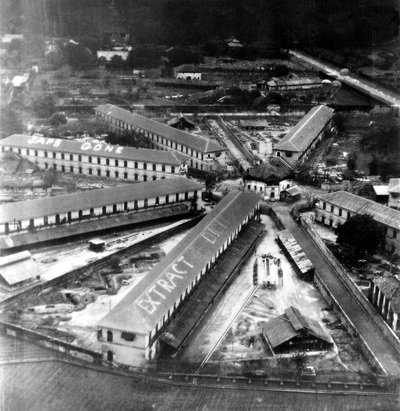

As mentioned earlier the Chindit soldiers captured by the Japanese in 1943 were first of all rounded up and sent to a concentration camp at a place called Maymyo. Once the Japanese considered that all the new prisoners had been gathered, they sent them down to Rangoon by train, loading the ailing and exhausted men into cattle trucks for the long and uncomfortable journey.

John was given the POW number 398 when he first entered Rangoon Central Jail and was placed in to Block 6 of the prison. Eventually there would be over 200 Chindits present in Rangoon Jail, most if not all spent the first few months in Block 6. For more details on the Chindits time in captivity please read the pages, Chindit POW's and the Maymyo Concentration Camp by following the links below:

Chindit POW's

Maymyo Concentration Camp

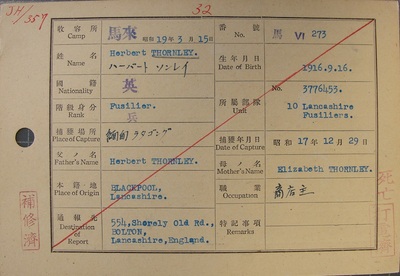

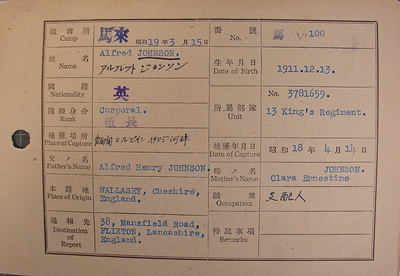

The Chindits had been told to disguise their rank if at all possible when captured by the Japanese. This was to protect the Officers and NCO's (Non-commsiioned Officers) from further and more brutal interrogation by the Japanese secret police. John's true rank must have been discovered because his original POW number was changed from 398 to 99, the lower number depicting his status as a NCO and Sergeant. You can see his POW number in the top right hand corner of his index card in the Gallery below.

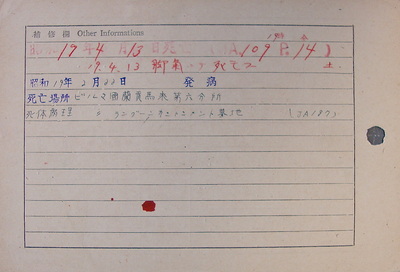

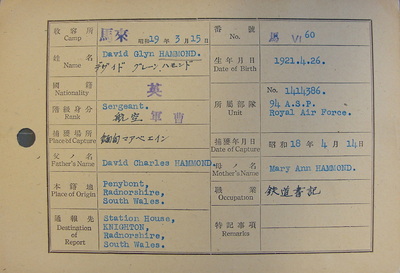

Many of the prisoners held by the Japanese in SE Asia during the war had these index cards which recorded their POW history. They showed the POW's service particulars such as name, rank, service number, but also detailed the date of capture, next of kin details and on the reverse of the card any other pertinent information. John's card shows that he was captured on 14th April 1943, the diagonal red line drawn across the card sadly signifies that he had died whilst a prisoner.

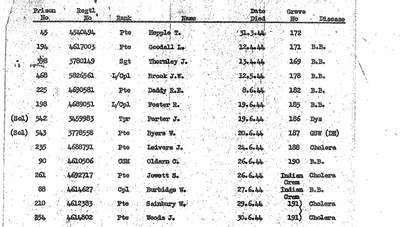

Sgt. Thornley died on the 13th April 1944 suffering from the effects of the disease called beri beri. These details were written in Japanese Kanji characters on the reverse of his card, where it also stated that he had been taken ill with the disease in late February that year. Beri Beri was the most common cause of death for prisoners in Rangoon Jail, along with dysentery, malaria and infected skin sores. The disease beri beri is caused by a diet lacking in Vitamin B, in Rangoon Jail the prisoners were fed on low-grade polished rice and little else, it did not take long for this poor diet to take its toll on the men.

One of the main reasons why the men from the first Chindit operation died in such large numbers whilst in enemy hands, was the fact that they were already in an exhausted and malnourished state when they arrived at the jail. It is probably true to say that the vast majority perished from their exertions whilst operating in the jungle, rather than anything their Japanese hosts meted out during their time as a POW.

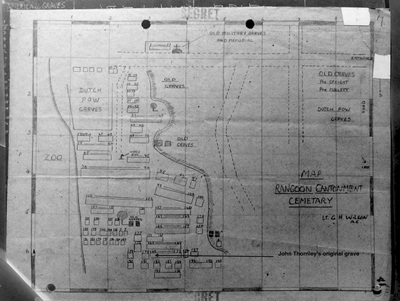

John Thornley was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery and his grave plot was recorded by the officer in charge of the service as 169. You can see this plot marked out on the cemetery plan shown in the photo gallery below. Herbert attended his brother's funeral alongside John's long standing Chindit comrade Corporal Alfred Johnson. Most of the POW's who perished inside Rangoon Jail were buried in this cemetery. After the war the Imperial War Graves Commission built a new cemetery in Rangoon and all the graves were moved over to this new location. For more information about these burials and cemeteries, please click on the link below:

Memorials and Cemeteries

Seen below is a collection of images illustrating the story of John Thornley and his time as a Chindit in 1943 and ultimately a prisoner of war. Also included are some images relating to his brother's Herbert and Walter. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the screen.

Jack Thornley was born at the Waterloo Hotel Blackpool, where his father was the manager, on the 28th January 1912. He was christened “John” but always known as “Jack”. He was the eldest in what was to become a family of four brothers and a sister.

In 1926 he was awarded a certificate by the “Daily Dispatch” for proficiency in a national scholarship competition. He gained his Matriculation Certificate in 1928 and got a job with the District Bank. By 1939 he had become the youngest assistant manager in the Bank's history. He married Dorothy Gray, sister of his best friend's wife Elsie, in June 1939.

He was 27 when the war broke out. As the war progressed and more troops were required, the age of conscription was steadily raised. He became eligible for call-up in 1942.

A week after his best friend (and now brother-in-law), of the same age had been conscripted, Jack went to the recruitment office to complain that he had been missed out. It was explained to him that conscripts were taken in alphabetical order and his brother-in-law's name began with a D, while his was T. Eventually he was called for a medical where he hid a recently broken collar bone in case it delayed his entry into the Army.

During training he was offered a chance to apply for a commission, which he turned down because, in his words,"the war might end before he finished the course". He trained as a Wireless Operator with the 13th King's based in Liverpool. At the end of his training he was made up to Sergeant.

The 13th King's consisted of 'old men' in their late twenties/early thirties and was originally intended for coastal defence duties in the UK. Eventually the decision was made to send the 13th King's to India to release the younger men who were there on policing duties for active service. It was while the King's Regiment were en route to India by sea that Churchill added them to a list of miscellaneous troops offered to Orde Wingate to use for his first expedition into Burma.

A good proportion of the King's men opted out during training once they realised the nature of the enterprise. Jack's letters home at that time were enthusiastic about Army life and expressed his intention to make it his career after the war ended.

On a visit to the cinema in early 1943 Jack's wife was surprised to see him sitting by his radio in a newsreel about the Chindits. She persuaded the cinema to give her three frames of the 35mm film. The same War Office picture has been used to illustrate countless books and articles about the Chindits.

Jack was captured on 14th April 1943 and died on 13th April 1944 in Rangoon Prison. His wife was informed that he was missing on 1st April 1943 but not of his death until 6th June 1945 – his youngest brother's wedding day. The news came at the same time as that of the death of his brother Herbert, also in Rangoon Prison, and was kept from the bride and groom until they returned from honeymoon. The other brother Walter, an RAF regular, died on his first day as a test pilot in August 1942 having just returned from serving in Iraq.

Great Grandson Jack Lewin has published a very interesting website about his international cycling tour and his attempt to reach Burma on two wheels and visit amongst other places, the grave of his Great Grandfather. Please click on the link below to read more:

http://jblewi.wordpress.com

As mentioned earlier the Chindit soldiers captured by the Japanese in 1943 were first of all rounded up and sent to a concentration camp at a place called Maymyo. Once the Japanese considered that all the new prisoners had been gathered, they sent them down to Rangoon by train, loading the ailing and exhausted men into cattle trucks for the long and uncomfortable journey.

John was given the POW number 398 when he first entered Rangoon Central Jail and was placed in to Block 6 of the prison. Eventually there would be over 200 Chindits present in Rangoon Jail, most if not all spent the first few months in Block 6. For more details on the Chindits time in captivity please read the pages, Chindit POW's and the Maymyo Concentration Camp by following the links below:

Chindit POW's

Maymyo Concentration Camp

The Chindits had been told to disguise their rank if at all possible when captured by the Japanese. This was to protect the Officers and NCO's (Non-commsiioned Officers) from further and more brutal interrogation by the Japanese secret police. John's true rank must have been discovered because his original POW number was changed from 398 to 99, the lower number depicting his status as a NCO and Sergeant. You can see his POW number in the top right hand corner of his index card in the Gallery below.

Many of the prisoners held by the Japanese in SE Asia during the war had these index cards which recorded their POW history. They showed the POW's service particulars such as name, rank, service number, but also detailed the date of capture, next of kin details and on the reverse of the card any other pertinent information. John's card shows that he was captured on 14th April 1943, the diagonal red line drawn across the card sadly signifies that he had died whilst a prisoner.

Sgt. Thornley died on the 13th April 1944 suffering from the effects of the disease called beri beri. These details were written in Japanese Kanji characters on the reverse of his card, where it also stated that he had been taken ill with the disease in late February that year. Beri Beri was the most common cause of death for prisoners in Rangoon Jail, along with dysentery, malaria and infected skin sores. The disease beri beri is caused by a diet lacking in Vitamin B, in Rangoon Jail the prisoners were fed on low-grade polished rice and little else, it did not take long for this poor diet to take its toll on the men.

One of the main reasons why the men from the first Chindit operation died in such large numbers whilst in enemy hands, was the fact that they were already in an exhausted and malnourished state when they arrived at the jail. It is probably true to say that the vast majority perished from their exertions whilst operating in the jungle, rather than anything their Japanese hosts meted out during their time as a POW.

John Thornley was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery and his grave plot was recorded by the officer in charge of the service as 169. You can see this plot marked out on the cemetery plan shown in the photo gallery below. Herbert attended his brother's funeral alongside John's long standing Chindit comrade Corporal Alfred Johnson. Most of the POW's who perished inside Rangoon Jail were buried in this cemetery. After the war the Imperial War Graves Commission built a new cemetery in Rangoon and all the graves were moved over to this new location. For more information about these burials and cemeteries, please click on the link below:

Memorials and Cemeteries

Seen below is a collection of images illustrating the story of John Thornley and his time as a Chindit in 1943 and ultimately a prisoner of war. Also included are some images relating to his brother's Herbert and Walter. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the screen.

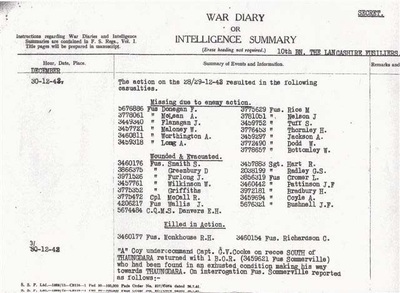

3776453 Fusilier Herbert Thornley served with the 10th Lancashire Fusiliers in the Arakan region of Burma in 1942. Late on that year he was involved in some extremely arduous fighting at a place called Rathedaung, where his battalion fought the Japanese at close quarters over difficult terrain. According to the battalion War diary (seen in the gallery above) and his Japanese index card, Herbert was captured on the 29th December 1942. He was eventually transported across to Rangoon with several other men from his battalion and was imprisoned in Block 3 of the jail.

For more information about the 10th Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers and their time in Burma, please click on the links below:

http://www.lancs-fusiliers.co.uk/gallerynew/10Bngallery/wardiarys/NEW%2010th%20BN%20War%20Diary%20List%20of%20names1.htm

http://www.lancs-fusiliers.co.uk/gallerynew/10Bngallery/10lf1944-45.htm

From the Daily Telegraph published on Tuesday 16th March 1943 comes this report about the fighting around Rathedaung and the performance of the British regimental battalions present.

LEARNING NEW TACTICS

It may now be revealed that the Lancashire Fusiliers and the Inniskillings have taken part with distinction in the Arakan campaign, from the first forward movements made last November.

When I first visited this front in November, the Fusiliers were gaining their first experience of jungle warfare, which demanded the cheerful endurance of a torrential rainfall and widespread floods.

They were among the troops that advanced through intensely difficult terrain on Buthidaung, finding it deserted. A few days later parties travelled by sampan down the Mayu River, and on Christmas Day a young officer and seven men entered Rathedaung, which is 25 miles from Akyab.

They found Rathedaung also deserted except for one old man. A few days later a much larger body of Lancashire Fusiliers followed and found the enemy had returned in force.

A desperate fight followed, in which the British troops inflicted many casualties, but one party, led by the battalion's second-in-command, was cut off and presumably taken prisoner.

The Lancashire Fusiliers remained north of Rathedaung, carrying out many gallant attacks and constantly improving their tactics. The Inniskillings, who went back to the Arakan, were already veterans, having taken part in the retreat last May.

PRISONERS ESCAPE

Something of their high morale is shown by the number that have returned to our lines after being cut off or even taken prisoner. One was out for more than a week without food or water lying hidden with the Japanese all round.

For more information about the 10th Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers and their time in Burma, please click on the links below:

http://www.lancs-fusiliers.co.uk/gallerynew/10Bngallery/wardiarys/NEW%2010th%20BN%20War%20Diary%20List%20of%20names1.htm

http://www.lancs-fusiliers.co.uk/gallerynew/10Bngallery/10lf1944-45.htm

From the Daily Telegraph published on Tuesday 16th March 1943 comes this report about the fighting around Rathedaung and the performance of the British regimental battalions present.

LEARNING NEW TACTICS

It may now be revealed that the Lancashire Fusiliers and the Inniskillings have taken part with distinction in the Arakan campaign, from the first forward movements made last November.

When I first visited this front in November, the Fusiliers were gaining their first experience of jungle warfare, which demanded the cheerful endurance of a torrential rainfall and widespread floods.

They were among the troops that advanced through intensely difficult terrain on Buthidaung, finding it deserted. A few days later parties travelled by sampan down the Mayu River, and on Christmas Day a young officer and seven men entered Rathedaung, which is 25 miles from Akyab.

They found Rathedaung also deserted except for one old man. A few days later a much larger body of Lancashire Fusiliers followed and found the enemy had returned in force.

A desperate fight followed, in which the British troops inflicted many casualties, but one party, led by the battalion's second-in-command, was cut off and presumably taken prisoner.

The Lancashire Fusiliers remained north of Rathedaung, carrying out many gallant attacks and constantly improving their tactics. The Inniskillings, who went back to the Arakan, were already veterans, having taken part in the retreat last May.

PRISONERS ESCAPE

Something of their high morale is shown by the number that have returned to our lines after being cut off or even taken prisoner. One was out for more than a week without food or water lying hidden with the Japanese all round.

We know that Herbert was held in Block 3 of Rangoon Jail and that he probably did not realise immediately that his brother had also arrived there in early May 1943. All the various block buildings were separated by long and high walls, but sometimes you could look across into the other blocks when standing in the courtyard at the centre of the jail. One way or another word soon got out that John was in Block 6. We can only assume that they attempted to make contact with each other using the prison grapevine and that it must have brought some small comfort to each of them, knowing that the other was still alive.

It is difficult to imagine the devastation that Herbert must have felt when he learned of his brother's death in April 1944. I wonder how much, if any contact they had achieved in the months since John first entered Rangoon Jail one year before. I sincerely hope that there had been some form of contact before Herbert attended his brother's funeral in the English Cantonment Cemetery. I wonder also, how much seeing his older brother pass away, contributed to Herbert's own death just a few weeks later.

Herbert Thornley died at 12.30 pm on the 26th July 1944 in Block 3 of Rangoon Jail, he would have been buried, like his brother before him, in the English Cantonment Cemetery. The details written on the reverse of his Japanese index card and on the list of deaths for Block 3, tell us that he too died from the effects of the disease beri beri, with the added complication of chronic colitis.

It is difficult to imagine the devastation that Herbert must have felt when he learned of his brother's death in April 1944. I wonder how much, if any contact they had achieved in the months since John first entered Rangoon Jail one year before. I sincerely hope that there had been some form of contact before Herbert attended his brother's funeral in the English Cantonment Cemetery. I wonder also, how much seeing his older brother pass away, contributed to Herbert's own death just a few weeks later.

Herbert Thornley died at 12.30 pm on the 26th July 1944 in Block 3 of Rangoon Jail, he would have been buried, like his brother before him, in the English Cantonment Cemetery. The details written on the reverse of his Japanese index card and on the list of deaths for Block 3, tell us that he too died from the effects of the disease beri beri, with the added complication of chronic colitis.

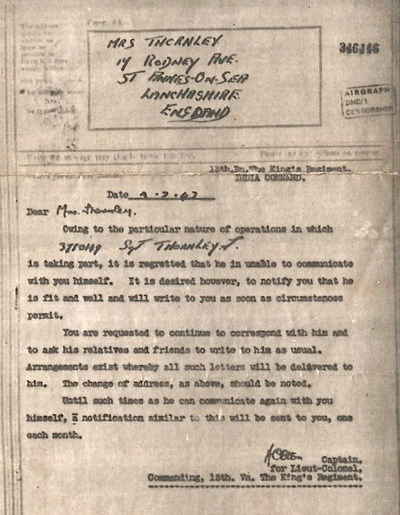

On the 4th August 1943, Dorothy, the wife of John Thornley received a notification from the War Office that all wives and families must have dreaded. John was reported as missing in action and no further information was available at that time. The letter stated:

It is with the deepest regret that I write to inform you that your husband is missing. It is quite possible that he may be a prisoner of war, but we have no evidence that this is the case.

Our Commanding Officer and all ranks of the Battalion wish me to convey our most sincere sympathy in your great anxiety and to assure you that should we get any further news of your husband, we will at once let you know.

Yours sincerely P.A. Bennett (Lieutenant Peter A. Bennett) on behalf of Officer commanding 8 Column.

For all the unfortunate families that received similar notices in 1943, my Nan included, the anxious wait for more news would last a further two excruciatingly long years. Then in the middle months of 1945 the heartbreaking news was sent out to the Thornley family that both John and Herbert had died whilst prisoners of war in Rangoon Jail. For their mother Elizabeth Thornley, this announcement must have been totally devastating, especially when you consider that she had already lost another of her sons, Walter, in August 1942.

Here is how the local newspaper reported the sad news:

Brothers Die in Jap Camps

Within two days messages have been received of the death of two brothers who were prisoners of war in Japan. They were Sergeant John Thornley, aged 32, and Pte. Herbert Thornley aged 27, sons of Mrs. Thornley of Woodstock Gardens, South Shore, and the late Mr. Herbert Thornley, for 25 years the licensee of the Waterloo Hotel.

A third son, Flight Officer Walter Thornley, aged 29, was killed on active service with the RAF in August 1942. Sergeant J. Thornley, who was one of Wingate's Chindits was reported missing in Burma in April 1942 (a printing error, should read 1943) and died two years later. His wife, Mrs. Dorothy Thornley and four year old son live in Rodney Avenue, St. Annes.

Pte. H. Thornley, who was reported missing in December 1942, died on July 24th 1944. His wife and two children live in Bolton, where for eight years Pte. Thornley was a supervisor for Messrs. Magee, Marshall and Co. Like Sergeant Thornley, he was an Old Boy of Palatine School, Blackpool.

A fourth brother Tom Thornley, who was married at Holy Trinity Church, South Shore last week, was on his honeymoon when news of the death of his two brothers became known to the family.

The family did receive some more information about John and Herbert in late June 1945. This came in the form of a letter written by Corporal Alfred Johnson, one of the men captured with John back in April 1943 when the group were sent out to collect bamboo near the Shweli River. This is what Alfred had to say:

Dear Mrs. Thornley,

I find it very difficult to start this letter knowing that it will cause you a great amount of grief, but I am sure you will want to learn a full account of the circumstances and conditions of both Jack and Berts deaths.

Jack and I had known each other since the Signals Section of the 13th. Kings were first formed and had been close friends right through to the end. We were fortunate enough to be posted to the same column when we entered Burma and here our friendship was further strengthened by the trials and tribulations we shared throughout the campaign.

The comfort and well being of each other was our mutual concern and no one could have had a better partner than I had in Jack. He enjoyed good health during the march through Burma and his continued good humour and fortitude often saved us when we were literally on 'our knees'. It was while we were trying to get back to India that Jack and I, together with two other friends were separated from the column and were unable to contact them again, we decided therefore to make our way back to India together and it was during this enterprise that we were unfortunate enough to be betrayed into the hands of the Japanese.

This happened on the 14th April,1943 at a village called Mabein, situated on the River Shwele in Northern Burma. From there we were taken though to Maymyo and thence to Rangoon where we were detained in Rangoon Central Jail with many more of our friends who shared the same fate as ourselves.

We had not been in the jail very long before Jack saw his brother who had been captured about twelve months previous and who was in another block of buildings in the same jail. The British P.O.W's were housed in two blocks, Bert was in No.3 Block and Jack and I in No.6.

Jack continued in good health until March 1944 when after illness in which he had an acute attack of dysentery he passed away on March 14th at about 5.p.m. He was buried in Rangoon Cemetery and Bert and I attended the funeral. I felt his going very deeply and know that I had lost a friend who would be hard to replace.

It was at Jack's funeral that I first met Bert in person although I had heard Jack talk of him often and had also seen him in the distance. I am afraid I do not know much about his capture and subsequent happenings up to this time, nor did I meet him again until he was transferred to No.6. Block in May 1944 when he was suffering from a mild attack of dysentery. (This disease was very prevalent in the jail throughout our stay there). He was beginning to pick up a little when a further attack of dysentery came upon him and in his already weakened state was unable to throw it off and he died in the last week of July.

The enclosed photographs are the only personal effects Jack had, and before Bert died he asked me to see that they, together with the press cutting and letter from Bert to his wife, were sent home if I was lucky enough to reach India again.

I have addressed this letter to you as I feel it will be the most direct means of getting the necessary information etc. to Jack's wife, whom I have met on several occasions, and also Mrs. Bert Thornley, also I should very much like to offer my condolences in a time which for you must be very heartbreaking.

Yours very sincerely, Alfred Johnson.

Although difficult to write, I am sure that Elizabeth Thornley would have drawn great comfort from Alfred's letter, I know that my own Nan would have been grateful to have received a similar correspondence.

Of the four men who found themselves separated from the main body of Column 8 on the 1st April 1943, only two would survive their time in Rangoon Jail and return home. After recuperating for a time in Calcutta Military Hospital, Alfred Johnson travelled home to Wallasey in Cheshire and David Glyn Hammond to his home in Radnorshire, South Wales. The third member of the 'firewood' party, Signalman Eric Rostance sadly perished in Rangoon Jail on the 27th of September 1943.

Seen below are the Japanese index cards for Johnson and Hammond and a newspaper photograph of Eric Rostance. Also seen is a contemporary map of the area where the four men were captured, near the village of Mabien. Please click on any image to enlarge it. Eric Rostance also has a short biography on this website, please click on the link below to view his story:

Eric Rostance. Please see the first story on this page.

It is with the deepest regret that I write to inform you that your husband is missing. It is quite possible that he may be a prisoner of war, but we have no evidence that this is the case.

Our Commanding Officer and all ranks of the Battalion wish me to convey our most sincere sympathy in your great anxiety and to assure you that should we get any further news of your husband, we will at once let you know.

Yours sincerely P.A. Bennett (Lieutenant Peter A. Bennett) on behalf of Officer commanding 8 Column.

For all the unfortunate families that received similar notices in 1943, my Nan included, the anxious wait for more news would last a further two excruciatingly long years. Then in the middle months of 1945 the heartbreaking news was sent out to the Thornley family that both John and Herbert had died whilst prisoners of war in Rangoon Jail. For their mother Elizabeth Thornley, this announcement must have been totally devastating, especially when you consider that she had already lost another of her sons, Walter, in August 1942.

Here is how the local newspaper reported the sad news:

Brothers Die in Jap Camps

Within two days messages have been received of the death of two brothers who were prisoners of war in Japan. They were Sergeant John Thornley, aged 32, and Pte. Herbert Thornley aged 27, sons of Mrs. Thornley of Woodstock Gardens, South Shore, and the late Mr. Herbert Thornley, for 25 years the licensee of the Waterloo Hotel.

A third son, Flight Officer Walter Thornley, aged 29, was killed on active service with the RAF in August 1942. Sergeant J. Thornley, who was one of Wingate's Chindits was reported missing in Burma in April 1942 (a printing error, should read 1943) and died two years later. His wife, Mrs. Dorothy Thornley and four year old son live in Rodney Avenue, St. Annes.

Pte. H. Thornley, who was reported missing in December 1942, died on July 24th 1944. His wife and two children live in Bolton, where for eight years Pte. Thornley was a supervisor for Messrs. Magee, Marshall and Co. Like Sergeant Thornley, he was an Old Boy of Palatine School, Blackpool.

A fourth brother Tom Thornley, who was married at Holy Trinity Church, South Shore last week, was on his honeymoon when news of the death of his two brothers became known to the family.

The family did receive some more information about John and Herbert in late June 1945. This came in the form of a letter written by Corporal Alfred Johnson, one of the men captured with John back in April 1943 when the group were sent out to collect bamboo near the Shweli River. This is what Alfred had to say:

Dear Mrs. Thornley,

I find it very difficult to start this letter knowing that it will cause you a great amount of grief, but I am sure you will want to learn a full account of the circumstances and conditions of both Jack and Berts deaths.

Jack and I had known each other since the Signals Section of the 13th. Kings were first formed and had been close friends right through to the end. We were fortunate enough to be posted to the same column when we entered Burma and here our friendship was further strengthened by the trials and tribulations we shared throughout the campaign.

The comfort and well being of each other was our mutual concern and no one could have had a better partner than I had in Jack. He enjoyed good health during the march through Burma and his continued good humour and fortitude often saved us when we were literally on 'our knees'. It was while we were trying to get back to India that Jack and I, together with two other friends were separated from the column and were unable to contact them again, we decided therefore to make our way back to India together and it was during this enterprise that we were unfortunate enough to be betrayed into the hands of the Japanese.

This happened on the 14th April,1943 at a village called Mabein, situated on the River Shwele in Northern Burma. From there we were taken though to Maymyo and thence to Rangoon where we were detained in Rangoon Central Jail with many more of our friends who shared the same fate as ourselves.

We had not been in the jail very long before Jack saw his brother who had been captured about twelve months previous and who was in another block of buildings in the same jail. The British P.O.W's were housed in two blocks, Bert was in No.3 Block and Jack and I in No.6.

Jack continued in good health until March 1944 when after illness in which he had an acute attack of dysentery he passed away on March 14th at about 5.p.m. He was buried in Rangoon Cemetery and Bert and I attended the funeral. I felt his going very deeply and know that I had lost a friend who would be hard to replace.

It was at Jack's funeral that I first met Bert in person although I had heard Jack talk of him often and had also seen him in the distance. I am afraid I do not know much about his capture and subsequent happenings up to this time, nor did I meet him again until he was transferred to No.6. Block in May 1944 when he was suffering from a mild attack of dysentery. (This disease was very prevalent in the jail throughout our stay there). He was beginning to pick up a little when a further attack of dysentery came upon him and in his already weakened state was unable to throw it off and he died in the last week of July.

The enclosed photographs are the only personal effects Jack had, and before Bert died he asked me to see that they, together with the press cutting and letter from Bert to his wife, were sent home if I was lucky enough to reach India again.

I have addressed this letter to you as I feel it will be the most direct means of getting the necessary information etc. to Jack's wife, whom I have met on several occasions, and also Mrs. Bert Thornley, also I should very much like to offer my condolences in a time which for you must be very heartbreaking.

Yours very sincerely, Alfred Johnson.

Although difficult to write, I am sure that Elizabeth Thornley would have drawn great comfort from Alfred's letter, I know that my own Nan would have been grateful to have received a similar correspondence.

Of the four men who found themselves separated from the main body of Column 8 on the 1st April 1943, only two would survive their time in Rangoon Jail and return home. After recuperating for a time in Calcutta Military Hospital, Alfred Johnson travelled home to Wallasey in Cheshire and David Glyn Hammond to his home in Radnorshire, South Wales. The third member of the 'firewood' party, Signalman Eric Rostance sadly perished in Rangoon Jail on the 27th of September 1943.

Seen below are the Japanese index cards for Johnson and Hammond and a newspaper photograph of Eric Rostance. Also seen is a contemporary map of the area where the four men were captured, near the village of Mabien. Please click on any image to enlarge it. Eric Rostance also has a short biography on this website, please click on the link below to view his story:

Eric Rostance. Please see the first story on this page.

I would like to thank Jack Lewin and Stuart Thornley for all their help bringing this very sad story to these website pages. Also for providing me with all the photographs, letters and other family information used in this narrative. I wish to dedicate this story to all the Thornley family, but especially to Elizabeth, mother of John, Herbert and Walter, the three sons she lost during the terrible years of World War Two.

Update 08/03/2015.

In late February 2015 I received an email contact from Anne Smith (nee Thornley) the daughter of Tom Thornley, the younger brother of Jack, Herbert and Walter. Anne was able to add more details about the Thornley family and has supplied me with some wonderful family photographs, including portraits of all four of the Thornley brothers.

From Anne's email contacts:

Hi Steve

As promised I attach the best photos I have of the four Thornley brothers. I am not sure whether Jack and Herbert’s are any better than the images you already have as they have deteriorated through age, but I have sent them anyway.

Flying Officer Walter Thornley was in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. He was commissioned on 8th April 1941as a Pilot Officer. I have no knowledge of his activities at this stage although I note you already have information that he was in Iraq. He was made a Flying Officer a year later and stationed at RAF Brize Norton. He was killed on 31st August 1942 in his role as a test pilot. He was 28 at the time (born in late 1913) and was not married. He is buried at St Paul’s Church Cemetery, Marton, Blackpool, along with his father who died 1941of natural causes and his maternal grandparents.

You will see from this information that his mother, Elizabeth Thornley, lost her husband, and three sons all within a space of just three years.

My father, Tom Thornley, was the youngest son by a number of years. He was 16 years old when the war started. He left school and started work in 1940 as a Junior Clerk for the local Gas Corporation. He joined the Home Guard and his duties included night guard at the Gas Works. He then studied full-time for two years to complete the Engineering Cadetship Diploma, based on the curriculum for Engineering Cadets for the Services.

He completed this in January 1945 and joined the Royal Signals as a Signalman, based at the Catterick Camp. He continued training there but peace was declared before he was called up to go overseas. He continued with the Royal Signals until 1946 when he transferred to Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (R.E.M.E) until 1948 when he was released with the rank of Lieutenant. He then went on to complete a B.Sc (Bachelor of Science) at Leeds University.

As a child I remember visiting my grandmother regularly on Sundays, and the photos of the three lost sons took pride of place on her wall above the dining table. My father had been close to Jack and there are entries in his diary about frequent visits to Jack and his new wife Dorothy. Neither he nor grandma talked much about the war and how it had affected the family.

In my reply I remarked that it was almost impossible to imagine how poor Elizabeth must have felt after WW2 had ended, having lost her husband and three sons and that she must have clung to young Tom even more tightly. I also asked Anne about the family grave at St. Paul's Cemetery at Marton.

Anne replied:

Hello again Steve,

I thought the story was finished when I sent the photos, but your reply about the grave has intrigued me yet again. When I was looking for the photos of Walter, I found a very old photo of the grave which has a cross with Walter’s name added to the plot. I also remember visiting the grave years ago when I went back to visit my father in Blackpool. I got this photograph out and realised that Walter was not on it.

However, I had also noticed an account from a Stone Masons in my fathers papers. In 1966, his mother Elizabeth died aged 85, and was buried in the same plot as her husband, parents and son. Dad had two new inscriptions added to the original marble memorial, Elizabeth Thornley and Walter Thornley, and an extensive repair of the stone and grave. The photo I have shows the memorial stone damaged and fallen over, with the details about Elizabeth missing and also those for Walter who would be underneath her. This piece has either broken off and become lost, or is buried under the soil.

With respect to the personal side of the story and Elizabeth’s great loss; here are a few more details if you wish to use them. As you know Elizabeth and Herbert were the managers of the Waterloo Hotel. They were very busy and empoyed a housemaid to help look after their family. Her name was Miss Rose Perry and she helped to bring up the children, particularly my father Tom who was much younger than the others. Dad said she was almost like a mother to him. Rose shared the grief with Elizabeth, and they became life-long companions, living together until Elizabeth’s health deteriorated and she needed residential care. The photograph I have enclosed show the pair in 1961, Elizabeth in the coat and Rose on her left.

You are right that Elizabeth was close to Dad and he eventually took responsibility for her care. His sister, also named Elizabeth (Betty), remained very close as well. This has been a most interesting journey for me in putting all this together. Many thanks for all your good work in keeping their memory alive.

Anne

My grateful thanks go to Anne for her help in truly bringing this story to life. Seen below are the photographs she has kindly sent over. They include portraits of all four of the Thornley brothers and the family grave at St. Paul's Cemetery. I have been very fortunate over the last few years to receive many photographs of the men who took part on Operation Longcloth. As you can imagine, at times this can be a fairly emotional moment, but I can honestly say that seeing the images of the four brothers has been the most poignant yet.

Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In late February 2015 I received an email contact from Anne Smith (nee Thornley) the daughter of Tom Thornley, the younger brother of Jack, Herbert and Walter. Anne was able to add more details about the Thornley family and has supplied me with some wonderful family photographs, including portraits of all four of the Thornley brothers.

From Anne's email contacts:

Hi Steve

As promised I attach the best photos I have of the four Thornley brothers. I am not sure whether Jack and Herbert’s are any better than the images you already have as they have deteriorated through age, but I have sent them anyway.

Flying Officer Walter Thornley was in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. He was commissioned on 8th April 1941as a Pilot Officer. I have no knowledge of his activities at this stage although I note you already have information that he was in Iraq. He was made a Flying Officer a year later and stationed at RAF Brize Norton. He was killed on 31st August 1942 in his role as a test pilot. He was 28 at the time (born in late 1913) and was not married. He is buried at St Paul’s Church Cemetery, Marton, Blackpool, along with his father who died 1941of natural causes and his maternal grandparents.

You will see from this information that his mother, Elizabeth Thornley, lost her husband, and three sons all within a space of just three years.

My father, Tom Thornley, was the youngest son by a number of years. He was 16 years old when the war started. He left school and started work in 1940 as a Junior Clerk for the local Gas Corporation. He joined the Home Guard and his duties included night guard at the Gas Works. He then studied full-time for two years to complete the Engineering Cadetship Diploma, based on the curriculum for Engineering Cadets for the Services.

He completed this in January 1945 and joined the Royal Signals as a Signalman, based at the Catterick Camp. He continued training there but peace was declared before he was called up to go overseas. He continued with the Royal Signals until 1946 when he transferred to Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (R.E.M.E) until 1948 when he was released with the rank of Lieutenant. He then went on to complete a B.Sc (Bachelor of Science) at Leeds University.

As a child I remember visiting my grandmother regularly on Sundays, and the photos of the three lost sons took pride of place on her wall above the dining table. My father had been close to Jack and there are entries in his diary about frequent visits to Jack and his new wife Dorothy. Neither he nor grandma talked much about the war and how it had affected the family.

In my reply I remarked that it was almost impossible to imagine how poor Elizabeth must have felt after WW2 had ended, having lost her husband and three sons and that she must have clung to young Tom even more tightly. I also asked Anne about the family grave at St. Paul's Cemetery at Marton.

Anne replied:

Hello again Steve,

I thought the story was finished when I sent the photos, but your reply about the grave has intrigued me yet again. When I was looking for the photos of Walter, I found a very old photo of the grave which has a cross with Walter’s name added to the plot. I also remember visiting the grave years ago when I went back to visit my father in Blackpool. I got this photograph out and realised that Walter was not on it.

However, I had also noticed an account from a Stone Masons in my fathers papers. In 1966, his mother Elizabeth died aged 85, and was buried in the same plot as her husband, parents and son. Dad had two new inscriptions added to the original marble memorial, Elizabeth Thornley and Walter Thornley, and an extensive repair of the stone and grave. The photo I have shows the memorial stone damaged and fallen over, with the details about Elizabeth missing and also those for Walter who would be underneath her. This piece has either broken off and become lost, or is buried under the soil.

With respect to the personal side of the story and Elizabeth’s great loss; here are a few more details if you wish to use them. As you know Elizabeth and Herbert were the managers of the Waterloo Hotel. They were very busy and empoyed a housemaid to help look after their family. Her name was Miss Rose Perry and she helped to bring up the children, particularly my father Tom who was much younger than the others. Dad said she was almost like a mother to him. Rose shared the grief with Elizabeth, and they became life-long companions, living together until Elizabeth’s health deteriorated and she needed residential care. The photograph I have enclosed show the pair in 1961, Elizabeth in the coat and Rose on her left.

You are right that Elizabeth was close to Dad and he eventually took responsibility for her care. His sister, also named Elizabeth (Betty), remained very close as well. This has been a most interesting journey for me in putting all this together. Many thanks for all your good work in keeping their memory alive.

Anne

My grateful thanks go to Anne for her help in truly bringing this story to life. Seen below are the photographs she has kindly sent over. They include portraits of all four of the Thornley brothers and the family grave at St. Paul's Cemetery. I have been very fortunate over the last few years to receive many photographs of the men who took part on Operation Longcloth. As you can imagine, at times this can be a fairly emotional moment, but I can honestly say that seeing the images of the four brothers has been the most poignant yet.

Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 10/05/2020.

I was delighted to receive the following email from Mike Thornley, who is the grandson of Fusilier Herbert Thornley and the fourth member of the wider Thornley family to get in touch via my website:

Dear Steve,

My name is Mike Thornley and inspired by VE Day I have attempted some basic research into members of my family who died in WW2. After some stumbling around I came across your excellent article which is like gold dust. I am the grandson of Fusilier Herbert Thornley who died in Burma. I think my father was only four years old when Herbert passed away and I am saddened that I never got to meet him. The story is of course made more poignant by the fact that his two brothers also died, although I wasn't aware of the 4th surviving brother until I read your excellent article. By coincidence I have just completed 30 years service in the Royal Engineers and so the military connection is of particular interest to me.

Unfortunately, my mother and father (Walter Trevor - Herbert's son) have both passed away now and to my deep regret I didn't ask them more about the history of my family while they were alive. Thank you for writing such a detailed and descriptive article which has both cheered and saddened me at the time of this very significant anniversary. I will have another look through the old photographs and papers that my mother kept and if I find anything of interest I will let you know. Kind regards, Mike.

I was delighted to receive the following email from Mike Thornley, who is the grandson of Fusilier Herbert Thornley and the fourth member of the wider Thornley family to get in touch via my website:

Dear Steve,

My name is Mike Thornley and inspired by VE Day I have attempted some basic research into members of my family who died in WW2. After some stumbling around I came across your excellent article which is like gold dust. I am the grandson of Fusilier Herbert Thornley who died in Burma. I think my father was only four years old when Herbert passed away and I am saddened that I never got to meet him. The story is of course made more poignant by the fact that his two brothers also died, although I wasn't aware of the 4th surviving brother until I read your excellent article. By coincidence I have just completed 30 years service in the Royal Engineers and so the military connection is of particular interest to me.

Unfortunately, my mother and father (Walter Trevor - Herbert's son) have both passed away now and to my deep regret I didn't ask them more about the history of my family while they were alive. Thank you for writing such a detailed and descriptive article which has both cheered and saddened me at the time of this very significant anniversary. I will have another look through the old photographs and papers that my mother kept and if I find anything of interest I will let you know. Kind regards, Mike.

Update 16/10/2022.

I was delighted to receive a new email contact from Jack Perrotta-Lewin, the great grandson of Sgt. John Thornley. Jack has asked me to add the following footnote to his great grandfather's story and I am honoured to do so:

During my above mentioned cycle tour, a trip I left on to find my great grandfathers grave in Myanmar/Burma, I met my Canadian now wife Meaghan in Turkey while I was passing through the town she was working in at the time. We are now living in Northern Ontario and have a two-month old daughter Violet Dottie Marie Perrotta-Lewin, Dottie comes from Dorothy, Sgt. John Thornley's wife. Had John not joined up to fight and made his journey to Myanmar/Burma this final chapter would not have been the same, I wouldn't have had the reason to travel there and would not have met Meaghan. Quite peculiar how history continues to change lives!

Jack Perrotta-Lewin.

I was delighted to receive a new email contact from Jack Perrotta-Lewin, the great grandson of Sgt. John Thornley. Jack has asked me to add the following footnote to his great grandfather's story and I am honoured to do so:

During my above mentioned cycle tour, a trip I left on to find my great grandfathers grave in Myanmar/Burma, I met my Canadian now wife Meaghan in Turkey while I was passing through the town she was working in at the time. We are now living in Northern Ontario and have a two-month old daughter Violet Dottie Marie Perrotta-Lewin, Dottie comes from Dorothy, Sgt. John Thornley's wife. Had John not joined up to fight and made his journey to Myanmar/Burma this final chapter would not have been the same, I wouldn't have had the reason to travel there and would not have met Meaghan. Quite peculiar how history continues to change lives!

Jack Perrotta-Lewin.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, Stuart Thornley and Jack Perrotta-Lewin, February 2014. Additional photographs and details from Anne Smith, March 2015.