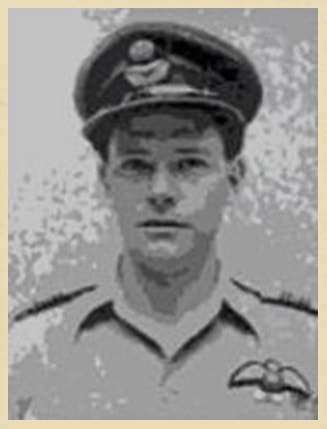

Sir Robert Grainger Ker Thompson

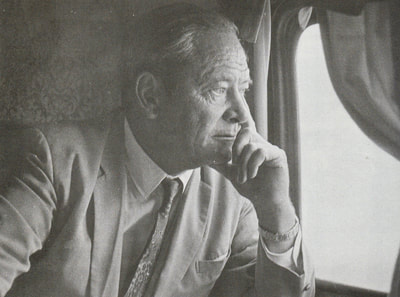

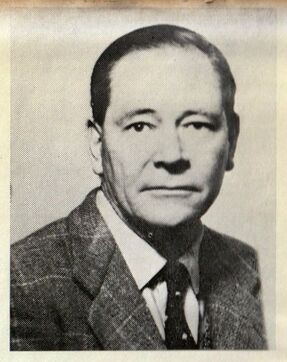

Sir Robert Thompson.

Sir Robert Thompson.

Born in 1916 and educated at Marlborough School and Cambridge, Robert Thompson entered the Malayan Civil Service in 1938. During WW2, as an RAF officer he escaped the Japanese from his base in Hong Kong by walking out through China. He served on both Chindit operations in Burma, being awarded a Military Cross for his efforts under Mike Calvert and 3 Column in 1943 and the Distinguished Service Order the following year.

After the war he returned to Malaya, where he was almost continuously involved with internal security during the Communist Emergency. From 1957 until 1961, he was successively Deputy Secretary and then full Secretary for Defence of the Federation of Malaya; and from 1961 to 1965 he headed the British Advisory Mission to South Vietnam. His experiences in Burma during the war and subsequent work in Malaya in relation to the attempted communist insurgency, led to his appointment as a consultant to the United States Government during the Vietnam war.

A fair-minded supporter of President Nixon and his policies through to the ceasefire in 1974, Thompson became increasingly concerned at America's eventual unwillingness to support countries such as South Vietnam against the spread of communism, both in terms of funding and economic aid, but perhaps more starkly, as the black body-bags containing American soldiers started to arrive home.

Robert Thompson has been a prolific writer on the subject of counter terrorism and insurgency across SE Asia. His efforts during the two Wingate expeditions involved his skills as an RAF liaison officer, tasked to bring in the vital air supply drops that would keep the Chindits fed and watered as they marched through the Burmese jungle. Thompson was teamed on both occasions with Mike Calvert and the Chindit columns of 77 Brigade, he was often given the responsibility in leading large sections of men, not just in his role as Air Liaison, but also in aggressive actions against the enemy.

From his book, Make for the Hills, published in 1989:

My first job in 1942, detailed by Wingate as a result of my being able to ride, was to train and fit out thirty mountain artillery mules, all reportedly from Missouri in the United States, to carry our wireless sets, charging engines and fuel. These mules were far bigger than the Indian-bred mules which carried all the other Army equipment.

All the mule-leaders for these animals were British and we had a lot of fun working up and I certainly became a great admirer of my mules. My mule-leaders were Privates Hall, Wilkinson and Pratt of the 13th King's. The mules were called Yankee, Daisy and the third's name for some reason I cannot remember, perhaps because we eventually ate it. As every farmer knows, it is much better that meals remain anonymous.

In 1943 at the conclusion of Operation Longcloth, Thompson was given the job of leading one of the small dispersal groups of around 30-35 men. His previous experience in evading the Japanese when he walked out of Hong Kong via China in 1941, ensured that he and his group were the first party from No. 3 Column to return safely to India. Alongside him when re-crossing the Chindwin River, were his RAF Sergeant, George Morris, Ptes. Hall, Wilkinson and Pratt and Yankee the mule.

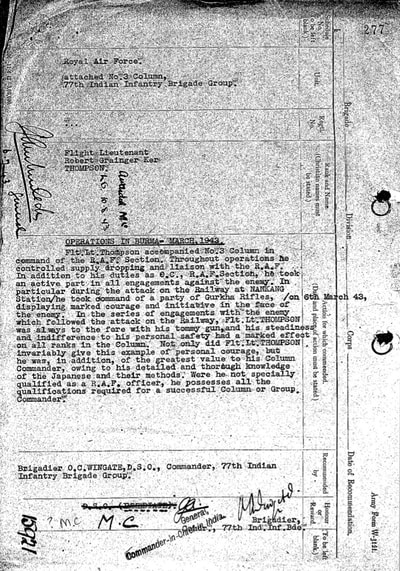

As mentioned previously, Robert Thompson was awarded the Military Cross for his efforts on Operation Longcloth:

Operations in Burma-March 1943

Flight Lieutenant Thompson accompained No. 3 Column in command of the RAF section. Throughout operations he controlled the supply dropping and liaison with the RAF. In addition to his duties as Officer Commanding the RAF Section, he took an active part in all engagements against the enemy. In particular during the attack on the railway at Nankang Station on the 6th March, he took command of a party of Gurkha Rifles, displaying marked courage and initiative in the face of the enemy.

In the series of engagements with the enemy which followed this attack on the railway, F/Lt. Thompson was always to the fore with his Tommy gun and his steadiness and indifference to his personal safety had a marked effect on all ranks from within the Column. Not only did F/Lt. Thompson invariably give this example of personal courage, but he was, in addition, of the greatest value to his column Commander (Calvert), owing to his detailed and thorough knowledge of the Japanese and their methods. Were he not specially qualified as a RAF officer, he possesses all the qualifications required for a successful Column or Group Commander.

Signed: Brigadier O.C. Wingate DSO, Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

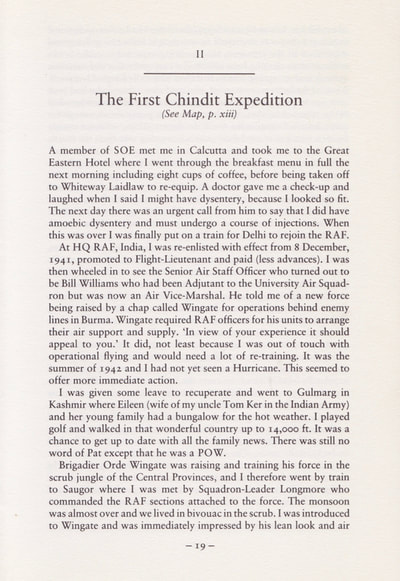

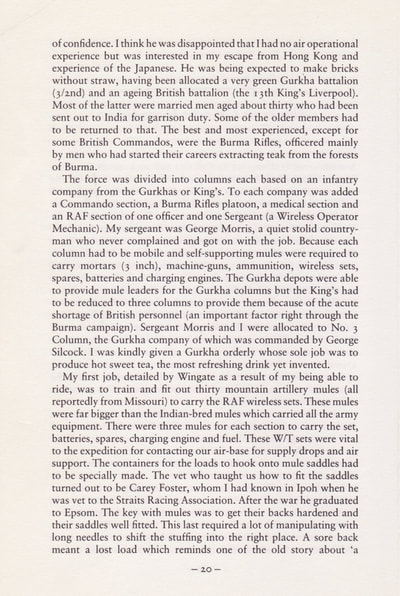

So much has been written by Sir Robert about his time with the Chindits, I have decided not to attempt to condense this down for the purposes of these pages, but to allow the man himself to tell his own story. From the book, Make for the Hills, published by Leo Cooper in 1989, here is the full chapter relating his experiences during Operation Longcloth, the first Chindit expedition. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After the war he returned to Malaya, where he was almost continuously involved with internal security during the Communist Emergency. From 1957 until 1961, he was successively Deputy Secretary and then full Secretary for Defence of the Federation of Malaya; and from 1961 to 1965 he headed the British Advisory Mission to South Vietnam. His experiences in Burma during the war and subsequent work in Malaya in relation to the attempted communist insurgency, led to his appointment as a consultant to the United States Government during the Vietnam war.

A fair-minded supporter of President Nixon and his policies through to the ceasefire in 1974, Thompson became increasingly concerned at America's eventual unwillingness to support countries such as South Vietnam against the spread of communism, both in terms of funding and economic aid, but perhaps more starkly, as the black body-bags containing American soldiers started to arrive home.

Robert Thompson has been a prolific writer on the subject of counter terrorism and insurgency across SE Asia. His efforts during the two Wingate expeditions involved his skills as an RAF liaison officer, tasked to bring in the vital air supply drops that would keep the Chindits fed and watered as they marched through the Burmese jungle. Thompson was teamed on both occasions with Mike Calvert and the Chindit columns of 77 Brigade, he was often given the responsibility in leading large sections of men, not just in his role as Air Liaison, but also in aggressive actions against the enemy.

From his book, Make for the Hills, published in 1989:

My first job in 1942, detailed by Wingate as a result of my being able to ride, was to train and fit out thirty mountain artillery mules, all reportedly from Missouri in the United States, to carry our wireless sets, charging engines and fuel. These mules were far bigger than the Indian-bred mules which carried all the other Army equipment.

All the mule-leaders for these animals were British and we had a lot of fun working up and I certainly became a great admirer of my mules. My mule-leaders were Privates Hall, Wilkinson and Pratt of the 13th King's. The mules were called Yankee, Daisy and the third's name for some reason I cannot remember, perhaps because we eventually ate it. As every farmer knows, it is much better that meals remain anonymous.

In 1943 at the conclusion of Operation Longcloth, Thompson was given the job of leading one of the small dispersal groups of around 30-35 men. His previous experience in evading the Japanese when he walked out of Hong Kong via China in 1941, ensured that he and his group were the first party from No. 3 Column to return safely to India. Alongside him when re-crossing the Chindwin River, were his RAF Sergeant, George Morris, Ptes. Hall, Wilkinson and Pratt and Yankee the mule.

As mentioned previously, Robert Thompson was awarded the Military Cross for his efforts on Operation Longcloth:

Operations in Burma-March 1943

Flight Lieutenant Thompson accompained No. 3 Column in command of the RAF section. Throughout operations he controlled the supply dropping and liaison with the RAF. In addition to his duties as Officer Commanding the RAF Section, he took an active part in all engagements against the enemy. In particular during the attack on the railway at Nankang Station on the 6th March, he took command of a party of Gurkha Rifles, displaying marked courage and initiative in the face of the enemy.

In the series of engagements with the enemy which followed this attack on the railway, F/Lt. Thompson was always to the fore with his Tommy gun and his steadiness and indifference to his personal safety had a marked effect on all ranks from within the Column. Not only did F/Lt. Thompson invariably give this example of personal courage, but he was, in addition, of the greatest value to his column Commander (Calvert), owing to his detailed and thorough knowledge of the Japanese and their methods. Were he not specially qualified as a RAF officer, he possesses all the qualifications required for a successful Column or Group Commander.

Signed: Brigadier O.C. Wingate DSO, Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

So much has been written by Sir Robert about his time with the Chindits, I have decided not to attempt to condense this down for the purposes of these pages, but to allow the man himself to tell his own story. From the book, Make for the Hills, published by Leo Cooper in 1989, here is the full chapter relating his experiences during Operation Longcloth, the first Chindit expedition. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

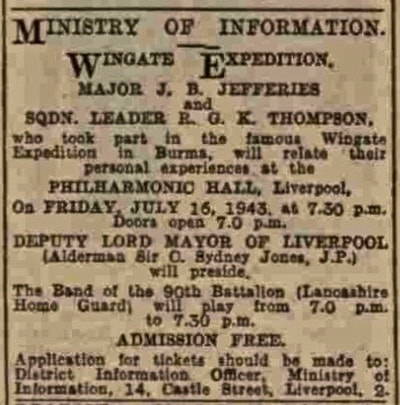

Immediately after Operation Longcloth, Wingate was asked by Winston Churchill to provide two candidates from his staff to travel to the United States and Britain to debrief the powers that be on the achievements gained from the first Chindit expedition. He chose, Robert Thompson and Major John B. Jefferies. Apart from debriefing the military and politicians from both countries, the two officers made a tour of both nations, giving lectures on Long Range Penetration in theatres and town halls. Robert Thompson was also ordered by Wingate to provide a debrief paper on the successes and failures of air supply during the operation which formed part of the final 120 page report on Operation Longcloth.

After his tour with Major Jefferies, Thompson returned to India and after a period of rest and recuperation, re-joined Mike Calvert and began preparation for the second Chindit campaign. In his book, Make for the Hills, Thompson recalled his time on tour in the United States explaining the key elements of Long Range Penetration. The following gallery includes these pages from his book, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After his tour with Major Jefferies, Thompson returned to India and after a period of rest and recuperation, re-joined Mike Calvert and began preparation for the second Chindit campaign. In his book, Make for the Hills, Thompson recalled his time on tour in the United States explaining the key elements of Long Range Penetration. The following gallery includes these pages from his book, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

For his exceptional work during the second Wingate expedition, Robert Thompson was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, a rare award to a RAF officer:

Squadron Leader Thompson was the senior RAF officer of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and RAF Adviser to the Brigade Commander on all matters of Air Support. In the performance of these duties he has always shown the utmost ingenuity and resourcefulness. During the battles round Henu Block his work played a decisive part in the fighting. On one occasion he joined in a charge and himself killed two Japanese. In the planning of the Airborne Landing and in its execution Squadron Leader Thompson's sound judgment was of the greatest assistance. In the battle of Mogaung, between 31st May and 27th July 1944, he organised the construction of forward airbases, including the laying of light aircraft landing strips, by the ingenious use of local material. The evacuation of a large number of casualties was greatly facilitated by the use of these landing strips and the effect on the morale of the fighting troops was important.

To ensure the success of direct air support in the Mogaung area Squadron Leader Thompson organised a system of communication with bomber pilots, thus enabling our troops to take immediate advantage of close bomber support. Although he was sick during the operations which were conducted to reduce a series of strong points at Natyegon and other places by direct air support, his energy, resource and knowledge contributed largely to the success of the operations. By his example and leadership throughout he has set a fine example to the other officers within his formation.

London Gazette: 13th February 1945.

Squadron Leader Thompson was the senior RAF officer of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and RAF Adviser to the Brigade Commander on all matters of Air Support. In the performance of these duties he has always shown the utmost ingenuity and resourcefulness. During the battles round Henu Block his work played a decisive part in the fighting. On one occasion he joined in a charge and himself killed two Japanese. In the planning of the Airborne Landing and in its execution Squadron Leader Thompson's sound judgment was of the greatest assistance. In the battle of Mogaung, between 31st May and 27th July 1944, he organised the construction of forward airbases, including the laying of light aircraft landing strips, by the ingenious use of local material. The evacuation of a large number of casualties was greatly facilitated by the use of these landing strips and the effect on the morale of the fighting troops was important.

To ensure the success of direct air support in the Mogaung area Squadron Leader Thompson organised a system of communication with bomber pilots, thus enabling our troops to take immediate advantage of close bomber support. Although he was sick during the operations which were conducted to reduce a series of strong points at Natyegon and other places by direct air support, his energy, resource and knowledge contributed largely to the success of the operations. By his example and leadership throughout he has set a fine example to the other officers within his formation.

London Gazette: 13th February 1945.

Sadly, Robert Thompson died on the 16th May 1992. To conclude this story, here is a transcription of his obituary as published in The Times of London that same month:

Sir Robert Thompson

Sir Robert Thompson, KBE, CMG, DSO, MC, permanent secretary for defence, Federation of Malaya, 1959-61; head of the British advisory mission to Vietnam, 1961-65; and one of the world's foremost experts on combating rural guerrilla warfare techniques, died on May 16th aged 76. He was born on April 12th 1916.

Robert Thompson led the kind of life which is given to few; a life of tremendous adventure and variety, crowned by the satisfaction, not only of battles won, but of seeing his views have a significant effect on world affairs.He was widely regarded on both sides of the Atlantic as the world's leading expert on countering the Mao Tse-tung technique of rural guerrilla insurgency.

He certainly devoted more of his life to this than almost any other man, being involved for 12 years throughout the emergency in Malaya, and then for four critical years in South Vietnam, after which he was in continuous demand as a consultant and adviser on the subject all over the world. He thoroughly absorbed the lessons he had learned in Malaya from the generals who fought and won that conflict and he realized profoundly that weight of fire power, preponderance of manpower and sophistication of equipment counted for nothing compared with the willingness to meet and defeat the enemy on his own terms, as the British did again so successfully in Brunei and Borneo in the mid-1960s. When Vietnam was over he remarked perceptively: ''The Americans never could see Vietnam in the time frame of Malaya they did not have patience for this sort of war.''

Robert Grainger Ker Thompson was the son of Canon W. G. Thompson. He went to Marlborough and took an MA at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. In 1938 he joined the Malayan Civil Service as a cadet, and was to serve in East and South East Asia almost without a break for the next 27 years.

While at Cambridge he had learned to fly with the University Air Squadron, so in the second world war he joind the RAF, and when the Japanese struck in 1941 he was serving in Macao, learning Cantonese. Thence came the first major adventure of his life. He escaped with a suitcase stuffed with notes, and gambled his way across mainland China to Burma. Here, he became RAF liaison officer on both of Wingate's Chindit expeditions, flying his own Hurricane and reaching the rank of wing commander. For his war services he was awarded the DSO and rare for an RAF officer the MC. The citation gave, as part explanation for the award to an RAF man of an Army medal, the fact that Wing Commander Thompson was ''always to the fore with his tommy-gun''.

After the war he returned in 1946 to the Malayan civil service and became assistant commissioner of labour in the state of Perak in 1946. After a course at the Joint Services Staff College at Latimer, he joined the staff of the newly appointed director of operations, Lieutenant-General Sir Harold Briggs, in 1950 and continued in that appointment throughout the tour of Lieutenant-General Sir Gerald Templer.

These were the crucial years of the Malayan emergency, and, when Thompson became a public figure ten years later, he was constantly embarrassed by being credited with a major share in winning it. He was always at pains to point out that he was at the time a very junior member of the staff of the men who did win it Briggs and Templer and under whom, he said, he learned the arts of counter-insurgency.

Later, when Malaya became independent, Thompson became permanent secretary for defence that is, the head civil servant in the defence ministry of Tun Abdul Razak, who subsequently became prime minister.

In 1960, as the Malaya emergency drew to a close, President Ngo Din Diem of South Vietnam asked Tunku Abdul Rahman, the Malayan prime minister, to send a team of experts to review the situation and advise him. Thompson led this team, and his report so impressed Diem that he asked the British government if he could have him back on a more permanent basis. Thompson, whose post was being Malayanised, was sent back to Saigon at the head of a small British advisory mission to President Diem, and he remained there (also serving Diem's successors) from 1961 until 1965.

While in Vietnam he was asked to organise the strategic hamlet programme on the lines of the successful programme in Malaya. Conditions, however, were very different and, whereas Briggs in Malaya had established 410 new villages in 18 months, President Diem's brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, insisted on establishing more than 8,000 strategic hamlets in the first year. Moreover, whereas no Malayan new village had been occupied until there was a viable police post to defend it, the strategic hamlets were virtually undefended except by armed villagers, so of course many were over-run and the programme was discredited. Soon afterwards both Dimand Nhu were assassinated.

Thompson, however, tried to introduce many other principles into Vietnam. He contended that the underground cadres in the villages were more important than the Vietcong guerrillas in the jungle, and that these must have priority for attack; that an effective police force and intelligence organisation were decisive (and lacking); that soldiers, policemen and government officials must themselves act within the law; and that aid for development was effective only if it produced a growing rural economy with local people trained to run it, instead of being dissipated on eye-catching projects which would collapse as soon as the money to maintain them no longer came from outside.

Thompson left Vietnam somewhat disillusioned, and pulished the lessons he had learned both in Malaya and in Vietnam in his first book, Defeating Communist Insurgency, in 1966. This is probably still the best book on counter-insurgency ever written. Thereafter, he went into semi-retirement in Somerset, where he was able to follow the life he had always longed to lead as a countryman, fishing, shooting and breeding his own birds; also playing golf to a single-figure handicap.

But he was not to be left in peace nor indeed would he have wished to be. He was engaged by the RAND Corporation as a consultant, and paid annual visits to Vietnam. After one of these, in 1968, he wrote a new book, No Exit from Vietnam, which was highly critical of American policy and techniques. The nub of his critical stance had already been expressed in his Alanbrooke memorial lecture in London in 1966: ''It is all very well having B-52 bombers, masses of helicopters and tremendous firepower, but none of these will eliminate a communist cell in a high school which is producing 50 recruits a year for the insurgent movement.'' The belief of the south Vietnamese generals that they held the military initiative was equally illusory, and found no similar conviction in the hearts of peasants in the countryside who daily withstood the assaults of the enemy.

No Exit from Vietnam greatly impressed President Nixon who, after he had put many of Thompson's ideas into practice, asked him to return and report to him direct. This he did, and his report, much more encouraging, was publicly quoted by the president. He continued such visits annually, each one followed by a personal interview with the president, and was also called upon to advise on similar problems in other countries.

Meanwhile he kept his other interests alive. He was particularly happy to be asked to write The Royal Flying Corps (1968) to mark the RAF's 50th anniversary, and in 1970 he published his Revolutionary War in World Strategy, 1945-1969. Peace is not at Hand (1975) further amplified his concern with Vietnam. In spite of his criticisms of American methods he remained convinced for some time, nevertheless, that an American victory in Vietnam was not only possible, but would be the best outcome for that country. He was later to take a more pessimistic view of events. Even after the fall of South Vietnam Thompson retained a degree of influence with the White House, and undertook one mission to Vietnam for President Ford. In 1981 he edited War in Peace: an analysis of warfare since 1945.

At home he found ample time for his country pursuits. He was a regular churchgoer all his life and played a full part in the life of the Somersetshire village which was his home. He married, in 1950, Merryn Newboult, daughter of Sir Alec Newboult, a former chief secretary in Malaya. They had a son and a daughter.

Sir Robert Thompson

Sir Robert Thompson, KBE, CMG, DSO, MC, permanent secretary for defence, Federation of Malaya, 1959-61; head of the British advisory mission to Vietnam, 1961-65; and one of the world's foremost experts on combating rural guerrilla warfare techniques, died on May 16th aged 76. He was born on April 12th 1916.

Robert Thompson led the kind of life which is given to few; a life of tremendous adventure and variety, crowned by the satisfaction, not only of battles won, but of seeing his views have a significant effect on world affairs.He was widely regarded on both sides of the Atlantic as the world's leading expert on countering the Mao Tse-tung technique of rural guerrilla insurgency.

He certainly devoted more of his life to this than almost any other man, being involved for 12 years throughout the emergency in Malaya, and then for four critical years in South Vietnam, after which he was in continuous demand as a consultant and adviser on the subject all over the world. He thoroughly absorbed the lessons he had learned in Malaya from the generals who fought and won that conflict and he realized profoundly that weight of fire power, preponderance of manpower and sophistication of equipment counted for nothing compared with the willingness to meet and defeat the enemy on his own terms, as the British did again so successfully in Brunei and Borneo in the mid-1960s. When Vietnam was over he remarked perceptively: ''The Americans never could see Vietnam in the time frame of Malaya they did not have patience for this sort of war.''

Robert Grainger Ker Thompson was the son of Canon W. G. Thompson. He went to Marlborough and took an MA at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. In 1938 he joined the Malayan Civil Service as a cadet, and was to serve in East and South East Asia almost without a break for the next 27 years.

While at Cambridge he had learned to fly with the University Air Squadron, so in the second world war he joind the RAF, and when the Japanese struck in 1941 he was serving in Macao, learning Cantonese. Thence came the first major adventure of his life. He escaped with a suitcase stuffed with notes, and gambled his way across mainland China to Burma. Here, he became RAF liaison officer on both of Wingate's Chindit expeditions, flying his own Hurricane and reaching the rank of wing commander. For his war services he was awarded the DSO and rare for an RAF officer the MC. The citation gave, as part explanation for the award to an RAF man of an Army medal, the fact that Wing Commander Thompson was ''always to the fore with his tommy-gun''.

After the war he returned in 1946 to the Malayan civil service and became assistant commissioner of labour in the state of Perak in 1946. After a course at the Joint Services Staff College at Latimer, he joined the staff of the newly appointed director of operations, Lieutenant-General Sir Harold Briggs, in 1950 and continued in that appointment throughout the tour of Lieutenant-General Sir Gerald Templer.

These were the crucial years of the Malayan emergency, and, when Thompson became a public figure ten years later, he was constantly embarrassed by being credited with a major share in winning it. He was always at pains to point out that he was at the time a very junior member of the staff of the men who did win it Briggs and Templer and under whom, he said, he learned the arts of counter-insurgency.

Later, when Malaya became independent, Thompson became permanent secretary for defence that is, the head civil servant in the defence ministry of Tun Abdul Razak, who subsequently became prime minister.

In 1960, as the Malaya emergency drew to a close, President Ngo Din Diem of South Vietnam asked Tunku Abdul Rahman, the Malayan prime minister, to send a team of experts to review the situation and advise him. Thompson led this team, and his report so impressed Diem that he asked the British government if he could have him back on a more permanent basis. Thompson, whose post was being Malayanised, was sent back to Saigon at the head of a small British advisory mission to President Diem, and he remained there (also serving Diem's successors) from 1961 until 1965.

While in Vietnam he was asked to organise the strategic hamlet programme on the lines of the successful programme in Malaya. Conditions, however, were very different and, whereas Briggs in Malaya had established 410 new villages in 18 months, President Diem's brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, insisted on establishing more than 8,000 strategic hamlets in the first year. Moreover, whereas no Malayan new village had been occupied until there was a viable police post to defend it, the strategic hamlets were virtually undefended except by armed villagers, so of course many were over-run and the programme was discredited. Soon afterwards both Dimand Nhu were assassinated.

Thompson, however, tried to introduce many other principles into Vietnam. He contended that the underground cadres in the villages were more important than the Vietcong guerrillas in the jungle, and that these must have priority for attack; that an effective police force and intelligence organisation were decisive (and lacking); that soldiers, policemen and government officials must themselves act within the law; and that aid for development was effective only if it produced a growing rural economy with local people trained to run it, instead of being dissipated on eye-catching projects which would collapse as soon as the money to maintain them no longer came from outside.

Thompson left Vietnam somewhat disillusioned, and pulished the lessons he had learned both in Malaya and in Vietnam in his first book, Defeating Communist Insurgency, in 1966. This is probably still the best book on counter-insurgency ever written. Thereafter, he went into semi-retirement in Somerset, where he was able to follow the life he had always longed to lead as a countryman, fishing, shooting and breeding his own birds; also playing golf to a single-figure handicap.

But he was not to be left in peace nor indeed would he have wished to be. He was engaged by the RAND Corporation as a consultant, and paid annual visits to Vietnam. After one of these, in 1968, he wrote a new book, No Exit from Vietnam, which was highly critical of American policy and techniques. The nub of his critical stance had already been expressed in his Alanbrooke memorial lecture in London in 1966: ''It is all very well having B-52 bombers, masses of helicopters and tremendous firepower, but none of these will eliminate a communist cell in a high school which is producing 50 recruits a year for the insurgent movement.'' The belief of the south Vietnamese generals that they held the military initiative was equally illusory, and found no similar conviction in the hearts of peasants in the countryside who daily withstood the assaults of the enemy.

No Exit from Vietnam greatly impressed President Nixon who, after he had put many of Thompson's ideas into practice, asked him to return and report to him direct. This he did, and his report, much more encouraging, was publicly quoted by the president. He continued such visits annually, each one followed by a personal interview with the president, and was also called upon to advise on similar problems in other countries.

Meanwhile he kept his other interests alive. He was particularly happy to be asked to write The Royal Flying Corps (1968) to mark the RAF's 50th anniversary, and in 1970 he published his Revolutionary War in World Strategy, 1945-1969. Peace is not at Hand (1975) further amplified his concern with Vietnam. In spite of his criticisms of American methods he remained convinced for some time, nevertheless, that an American victory in Vietnam was not only possible, but would be the best outcome for that country. He was later to take a more pessimistic view of events. Even after the fall of South Vietnam Thompson retained a degree of influence with the White House, and undertook one mission to Vietnam for President Ford. In 1981 he edited War in Peace: an analysis of warfare since 1945.

At home he found ample time for his country pursuits. He was a regular churchgoer all his life and played a full part in the life of the Somersetshire village which was his home. He married, in 1950, Merryn Newboult, daughter of Sir Alec Newboult, a former chief secretary in Malaya. They had a son and a daughter.

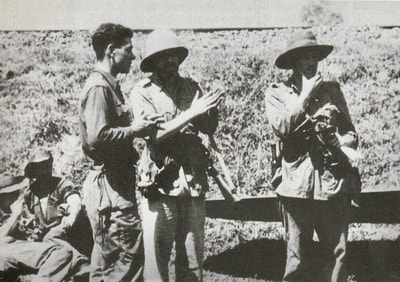

Seen below are some photographs of Robert Thompson during his time as an official advisor to the United States Government in relation to the war in Vietnam. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To read more about Robert Thompson's contribution during the Malayan Emergency, I would recommend the book, The War of the Running Dogs, by Noel Barber.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, August 2018.