Six Men of the Royal Ulster Rifles

Cap badge of the Royal Ulster Rifles.

Cap badge of the Royal Ulster Rifles.

Presented below is the information I have discovered in relation to six soldiers who were enlisted into the Royal Ulster Rifles Regiment for service during WW2. I am aware that one soldier, William James Livingstone, served with the Regiment overseas before the outbreak of the war, enlisting at Omagh in 1930.

The 13th Battalion of the King’s Regiment was raised at Glasgow in July 1940 and served with the 208th Infantry Brigade on the East Coast of England, engaged principally in Coastal defence duties. The unit was woefully short of experienced NCO’s and received small drafts of such men from many other British Regiments over the course of the following weeks and months. It can be no coincidence that five of the men originally from the Royal Ulster Rifles were of the rank of Corporal or above and had been transferred to the King’s to bolster the NCO strength.

In December 1941, the 13th King’s were posted overseas to India and stationed at Secunderabad for six months, before being selected to form part of the first Wingate Expedition into Burma.

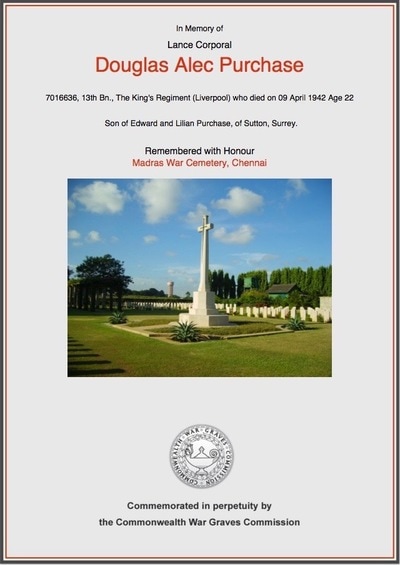

Lance Corporal 7016636 Douglas Alec Purchase

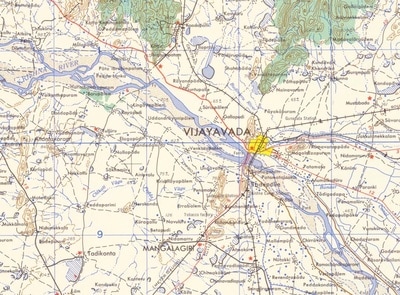

As already mentioned, the 13th Kings were originally stationed at Secunderabad in the Andhra Pradesh region of India, where they were involved in garrison and local policing duties. By April 1942 long-range Japanese bombers had been visiting targets of strategic value along the coastline of the Bay of Bengal. One such target was the Krishna Railway Bridge at Bezawada. The British Indian Command decided to place Anti-Aircraft installations to help protect these vulnerable locations and the 13th King's were nominated to protect the bridge at Bezawada.

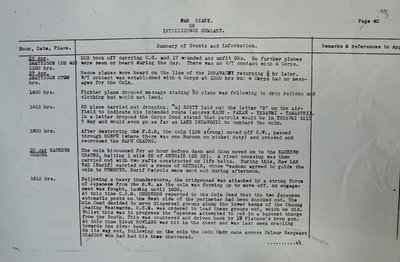

From the King's War Diary dated April 1942:

On the 6th April it was decided to send an Anti-Aircraft and Ground Defence unit over to Bezwada to protect the local town from enemy bomber attacks. Lieutenant Cottrell was given command of one of these units and early on the morning of the 7th April was sent over to Bezwada to set up the defence post. The A/A Platoon under Lt. Cottrell moved off at 0730 hours, the duration of their stay is indefinite, but it is more than likely that they will see some action.

By the next day news of a tragic accident had reached the battalion Adjutant, Captain David Hastings, and he reported in the diary that:

We heard today that one of the trucks carrying our men to Bezwada had overturned on the road and that one man was killed and four others injured. Details are yet unknown, but Major Stuart Lockhart and the Medical Officer left last night to attend to the men involved. It appears that the truck fell down an embankment during a landslide and was not anyone's fault as such. One man was killed having been struck on the head by an ammunition box. The driver was seriously injured and the other men were still in a state of shock.

Sadly, by the 10th April and having never regained consciousness the driver also died. Thankfully, it seems that Lieutenant Cottrell had not been one of the other men inside the unfortunate vehicle, but had been travelling in the truck just behind. It is not known exactly where the accident took place, other than it was on the road somewhere between Secunderabad and Bezawada.

By matching up the date of death with 13th King's casualties, I was confident that the driver of the truck was Lance Corporal Douglas Alec Purchase. This was confirmed by information found in the India Office Records for burials, where Douglas was recorded as having perished in a motor accident. He was buried in the Cochin Coonoor Cemetery in Bezwada; his funeral service was undertaken by Chaplain Walter R. Lane.

After the war Douglas Purchase, the son of Edward and Lilian Purchase from Sutton in Surrey was re-interred at Madras War Cemetery, Chennai.

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2173036/PURCHASE,%20DOUGLAS%20ALEC

Shown below are some images in relation to Lance Corporal Purchase and his unfortunate demise in India. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The 13th Battalion of the King’s Regiment was raised at Glasgow in July 1940 and served with the 208th Infantry Brigade on the East Coast of England, engaged principally in Coastal defence duties. The unit was woefully short of experienced NCO’s and received small drafts of such men from many other British Regiments over the course of the following weeks and months. It can be no coincidence that five of the men originally from the Royal Ulster Rifles were of the rank of Corporal or above and had been transferred to the King’s to bolster the NCO strength.

In December 1941, the 13th King’s were posted overseas to India and stationed at Secunderabad for six months, before being selected to form part of the first Wingate Expedition into Burma.

Lance Corporal 7016636 Douglas Alec Purchase

As already mentioned, the 13th Kings were originally stationed at Secunderabad in the Andhra Pradesh region of India, where they were involved in garrison and local policing duties. By April 1942 long-range Japanese bombers had been visiting targets of strategic value along the coastline of the Bay of Bengal. One such target was the Krishna Railway Bridge at Bezawada. The British Indian Command decided to place Anti-Aircraft installations to help protect these vulnerable locations and the 13th King's were nominated to protect the bridge at Bezawada.

From the King's War Diary dated April 1942:

On the 6th April it was decided to send an Anti-Aircraft and Ground Defence unit over to Bezwada to protect the local town from enemy bomber attacks. Lieutenant Cottrell was given command of one of these units and early on the morning of the 7th April was sent over to Bezwada to set up the defence post. The A/A Platoon under Lt. Cottrell moved off at 0730 hours, the duration of their stay is indefinite, but it is more than likely that they will see some action.

By the next day news of a tragic accident had reached the battalion Adjutant, Captain David Hastings, and he reported in the diary that:

We heard today that one of the trucks carrying our men to Bezwada had overturned on the road and that one man was killed and four others injured. Details are yet unknown, but Major Stuart Lockhart and the Medical Officer left last night to attend to the men involved. It appears that the truck fell down an embankment during a landslide and was not anyone's fault as such. One man was killed having been struck on the head by an ammunition box. The driver was seriously injured and the other men were still in a state of shock.

Sadly, by the 10th April and having never regained consciousness the driver also died. Thankfully, it seems that Lieutenant Cottrell had not been one of the other men inside the unfortunate vehicle, but had been travelling in the truck just behind. It is not known exactly where the accident took place, other than it was on the road somewhere between Secunderabad and Bezawada.

By matching up the date of death with 13th King's casualties, I was confident that the driver of the truck was Lance Corporal Douglas Alec Purchase. This was confirmed by information found in the India Office Records for burials, where Douglas was recorded as having perished in a motor accident. He was buried in the Cochin Coonoor Cemetery in Bezwada; his funeral service was undertaken by Chaplain Walter R. Lane.

After the war Douglas Purchase, the son of Edward and Lilian Purchase from Sutton in Surrey was re-interred at Madras War Cemetery, Chennai.

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2173036/PURCHASE,%20DOUGLAS%20ALEC

Shown below are some images in relation to Lance Corporal Purchase and his unfortunate demise in India. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Sergeant 7016701 Edward Whittaker

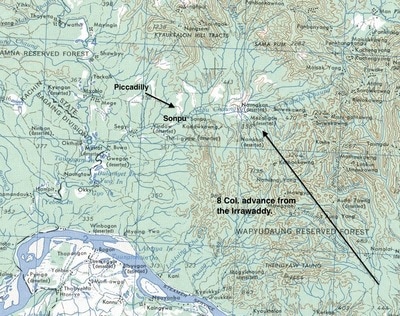

Edward Whittaker was from Ashton-under-Lyne in Greater Manchester and was a Section Leader within Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. After the first Wingate expedition had been ordered to return to India, Edward was marching with his own Group Head Quarters and 8 Column, commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King’s Regiment.

After almost ten weeks behind enemy lines in Burma, many of these men had become weakened by both hunger and disease. By late April, several men were no longer able to keep up with the main body as they marched and began to fall out along the track. Edward Whittaker was amongst this beleaguered group of soldiers and began to worry about his chances of exiting Burma alive. However, good fortune was to visit the large Chindit group as it halted for a short while close to a small river called the Patin Hka. From the pages of the 8 Column War diary, dated 25th April 1943:

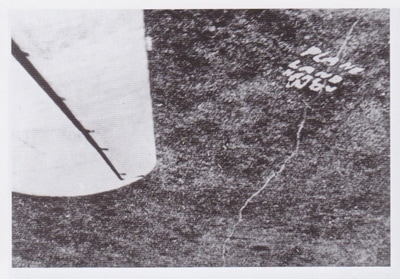

From talking with villagers, it was noted that most of the money in circulation was Japanese issue. After issuing the acquired ration of rice the column moved along the Sonpu track crossing the Patin Hka, a good running stream, intending to make as near as possible to the line of flight to be used by planes for the supply drop at 1500 hours. About 1 mile west of the Patin Hka we found a large open space running north so dispersed off the track on to the meadow and thence along the jungle on the eastern edge. At 1200 hours lit fires and cooked rice and made tea. At 1300 hours prepared supply drop ground and put out defences. A message "COULD PLANE LAND HERE" was put out in maps as it was thought possible a plane could land on this particular area.

Plane arrived at 1445 hours - earlier than expected - and dropped 5 days rations, Tommy Guns, waterproof capes, Bully, Cheese and Chocolate. Plane lowered undercarriage and tried to land but failed. It then made off to the west in a great hurry. Shortly afterwards a thunderstorm burst, hail stones the size of marbles fell and all the troops started collecting them to eat. Only half our demands had been dropped. It was through that the remaining supplies would be dropped later in the day but no planes arrived. Decided to go into bivouac for the night and wait to see if a plane would come the next day.

The next day more supplies were dropped and messages were exchanged between Major Scott and the RAF to see if another attempt could be made to land a plane on the meadow. The Chindits then went to work extending the landing area by clearing away light bush and the odd small tree. The War diary continues:

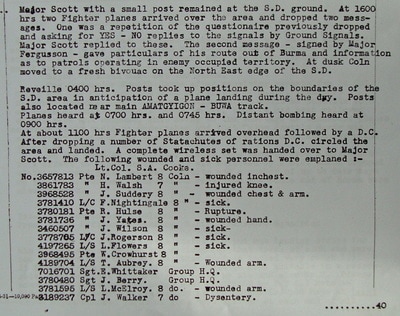

On the morning of the 28th April, planes were heard at 0700 hrs. and 0745 hrs. Distant bombing heard at 0900 hrs. At about 1100 hrs. fighter planes arrived overhead followed by a Dakota. After dropping a number of statachutes of rations, the Dakota circled the area and landed. A complete wireless set was handed over to Major Scott.

The following wounded and sick personnel were emplaned:

Lt.Col. S.A. Cooke.

3657813 Pte. N. Lambert 8 Column.

3861783 Pte. H. Walsh 7 Column.

3968528 Pte. J. Suddery 8 Column.

3781410 L/C. F. Nightingale 8 Column.

3780181 Pte. R. Hulse 8 Column.

3781736 Pte. J. Yates. 8 Column.

3460507 Pte. J. Wilson 8 Column.

3778705 L/C. J. Rogerson 8 Column.

4197265 L/S. L. Flowers 8 Column.

3968495 Pte. W. Crowhurst 8 Column.

4189704 L/S. T. Aubrey. 8 Column

7016701 Sgt. E. Whittaker Northern Group H.Q.

3780480 Sgt. J. Berry. Northern Group H.Q.

3781595 L/S. L. McElroy. 8 Column

3189237 Cpl. J. Walker 7 Column.

3823 Rfm.Tun Tin. 2nd Burma Rifles.

10468 Rfm. Kalabahadur 3/2 Gurkha Rifles.

The sick and wounded men including Edward Whittaker were flown to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal, where they were treated for their ailments by Matron Agnes McGearey (Q.A.I.M.N.S.) from Lanarkshire in Scotland. After recovering from his trials on Operation Longcloth, Edward Whittaker returned to the 13th King’s who were know based at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. Information about his continued service during WW2 is not known at this time.

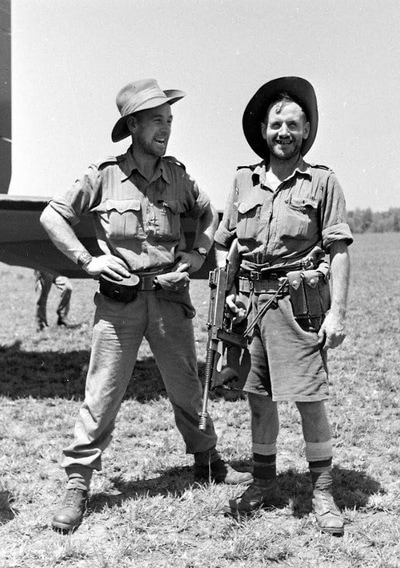

Seen below are some images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.To read more about the Dakota landings at Sonpu, please click on the following link: The Piccadilly Incident

Edward Whittaker was from Ashton-under-Lyne in Greater Manchester and was a Section Leader within Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. After the first Wingate expedition had been ordered to return to India, Edward was marching with his own Group Head Quarters and 8 Column, commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King’s Regiment.

After almost ten weeks behind enemy lines in Burma, many of these men had become weakened by both hunger and disease. By late April, several men were no longer able to keep up with the main body as they marched and began to fall out along the track. Edward Whittaker was amongst this beleaguered group of soldiers and began to worry about his chances of exiting Burma alive. However, good fortune was to visit the large Chindit group as it halted for a short while close to a small river called the Patin Hka. From the pages of the 8 Column War diary, dated 25th April 1943:

From talking with villagers, it was noted that most of the money in circulation was Japanese issue. After issuing the acquired ration of rice the column moved along the Sonpu track crossing the Patin Hka, a good running stream, intending to make as near as possible to the line of flight to be used by planes for the supply drop at 1500 hours. About 1 mile west of the Patin Hka we found a large open space running north so dispersed off the track on to the meadow and thence along the jungle on the eastern edge. At 1200 hours lit fires and cooked rice and made tea. At 1300 hours prepared supply drop ground and put out defences. A message "COULD PLANE LAND HERE" was put out in maps as it was thought possible a plane could land on this particular area.

Plane arrived at 1445 hours - earlier than expected - and dropped 5 days rations, Tommy Guns, waterproof capes, Bully, Cheese and Chocolate. Plane lowered undercarriage and tried to land but failed. It then made off to the west in a great hurry. Shortly afterwards a thunderstorm burst, hail stones the size of marbles fell and all the troops started collecting them to eat. Only half our demands had been dropped. It was through that the remaining supplies would be dropped later in the day but no planes arrived. Decided to go into bivouac for the night and wait to see if a plane would come the next day.

The next day more supplies were dropped and messages were exchanged between Major Scott and the RAF to see if another attempt could be made to land a plane on the meadow. The Chindits then went to work extending the landing area by clearing away light bush and the odd small tree. The War diary continues:

On the morning of the 28th April, planes were heard at 0700 hrs. and 0745 hrs. Distant bombing heard at 0900 hrs. At about 1100 hrs. fighter planes arrived overhead followed by a Dakota. After dropping a number of statachutes of rations, the Dakota circled the area and landed. A complete wireless set was handed over to Major Scott.

The following wounded and sick personnel were emplaned:

Lt.Col. S.A. Cooke.

3657813 Pte. N. Lambert 8 Column.

3861783 Pte. H. Walsh 7 Column.

3968528 Pte. J. Suddery 8 Column.

3781410 L/C. F. Nightingale 8 Column.

3780181 Pte. R. Hulse 8 Column.

3781736 Pte. J. Yates. 8 Column.

3460507 Pte. J. Wilson 8 Column.

3778705 L/C. J. Rogerson 8 Column.

4197265 L/S. L. Flowers 8 Column.

3968495 Pte. W. Crowhurst 8 Column.

4189704 L/S. T. Aubrey. 8 Column

7016701 Sgt. E. Whittaker Northern Group H.Q.

3780480 Sgt. J. Berry. Northern Group H.Q.

3781595 L/S. L. McElroy. 8 Column

3189237 Cpl. J. Walker 7 Column.

3823 Rfm.Tun Tin. 2nd Burma Rifles.

10468 Rfm. Kalabahadur 3/2 Gurkha Rifles.

The sick and wounded men including Edward Whittaker were flown to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal, where they were treated for their ailments by Matron Agnes McGearey (Q.A.I.M.N.S.) from Lanarkshire in Scotland. After recovering from his trials on Operation Longcloth, Edward Whittaker returned to the 13th King’s who were know based at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. Information about his continued service during WW2 is not known at this time.

Seen below are some images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.To read more about the Dakota landings at Sonpu, please click on the following link: The Piccadilly Incident

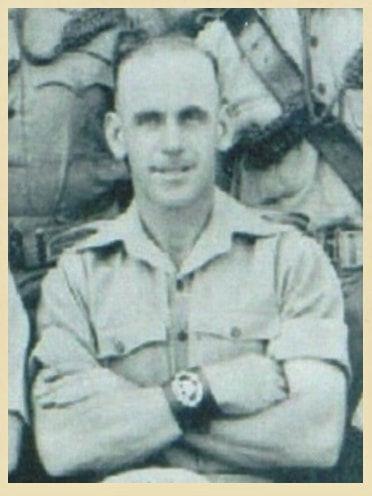

George McCool at Saugor in 1942.

George McCool at Saugor in 1942.

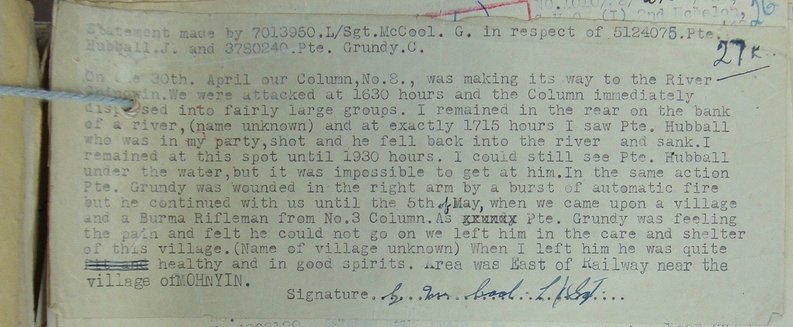

Lance Sergeant 7013950 G. McCool

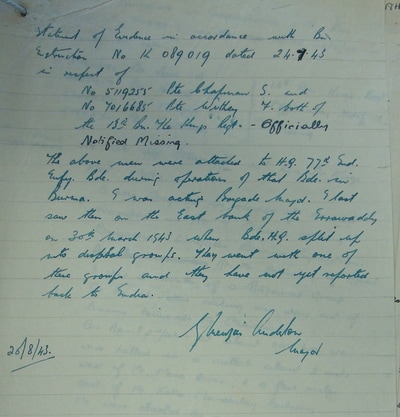

Not much is known about this soldier apart from his membership of Chindit Column No. 8 on Operation Longcloth. He would have been present at Sonpu when Sgt. Whittaker and the other men flew out of Burma aboard the Dakota on the 28th April 1943. McCool’s main contribution to the first Wingate expedition comes in the form of a witness statement he gave in relation to the fate of some of his Chindit comrades in 1943. Please see image below for details.

Two days after the Dakota plane had rescued the 18 men from the meadow at Sonpu; the rest of 8 Column had reached the outskirts of a village called Okthaik, a few miles directly to the west. On the morning of the 30th April, they camped out close to a fast flowing river named the Kaukkwe Chaung.

From the pages of the 8 Column War diary:

The column bivouacked for an hour before dawn and then moved on to the Kaukkwe Chaung, halting one mile south-east of Okhtaik. A river crossing was then carried out with two rafts constructed on our life belts. During this time, Havildar Lan Val of the Burma Rifles carried out a recce of Okthaik and spoke to the Headman of the village.

Following a heavy thunderstorm, our bridgehead at the river was attacked by a strong force of Japanese from the south-west. An engagement was fought lasting until 1630 hours. At this time CSM Cheevers reported to the column that two Japanese machine gun posts had been knocked out. Column commander decided to move dispersal groups along the lower banks of the river leading westwards. The RSM (William Livingstone) was ordered to lead these groups out, which he did.

During the battle at the Kaukkwe Chaung, many of the leading NCO’s from 8 Column, including Lance Sergeant McCool, CSM Cheevers and RSM Livingstone, assisted the numerous non-swimmers across the river. If it were not for their exemplary actions that day, many more Chindits would have been lost.

To read more about the incident at the Kaukkwe Chaung and Sgt. McCool’s involvement, please click on the following link:

Frank Lea, Ellis Grundy and the Kaukkwe Chaung

According to a one-line obituary in the Burma Star Association’s magazine, Dekho, Lance Sergeant McCool died in 2004 and had been living in Derby, England.

Not much is known about this soldier apart from his membership of Chindit Column No. 8 on Operation Longcloth. He would have been present at Sonpu when Sgt. Whittaker and the other men flew out of Burma aboard the Dakota on the 28th April 1943. McCool’s main contribution to the first Wingate expedition comes in the form of a witness statement he gave in relation to the fate of some of his Chindit comrades in 1943. Please see image below for details.

Two days after the Dakota plane had rescued the 18 men from the meadow at Sonpu; the rest of 8 Column had reached the outskirts of a village called Okthaik, a few miles directly to the west. On the morning of the 30th April, they camped out close to a fast flowing river named the Kaukkwe Chaung.

From the pages of the 8 Column War diary:

The column bivouacked for an hour before dawn and then moved on to the Kaukkwe Chaung, halting one mile south-east of Okhtaik. A river crossing was then carried out with two rafts constructed on our life belts. During this time, Havildar Lan Val of the Burma Rifles carried out a recce of Okthaik and spoke to the Headman of the village.

Following a heavy thunderstorm, our bridgehead at the river was attacked by a strong force of Japanese from the south-west. An engagement was fought lasting until 1630 hours. At this time CSM Cheevers reported to the column that two Japanese machine gun posts had been knocked out. Column commander decided to move dispersal groups along the lower banks of the river leading westwards. The RSM (William Livingstone) was ordered to lead these groups out, which he did.

During the battle at the Kaukkwe Chaung, many of the leading NCO’s from 8 Column, including Lance Sergeant McCool, CSM Cheevers and RSM Livingstone, assisted the numerous non-swimmers across the river. If it were not for their exemplary actions that day, many more Chindits would have been lost.

To read more about the incident at the Kaukkwe Chaung and Sgt. McCool’s involvement, please click on the following link:

Frank Lea, Ellis Grundy and the Kaukkwe Chaung

According to a one-line obituary in the Burma Star Association’s magazine, Dekho, Lance Sergeant McCool died in 2004 and had been living in Derby, England.

Update 12/03/2022.

I was delighted to receive the follow email in February 2022 from Marieanne Holbourne, one of George McCool's granddaughters:

Hi Steve, my grandad George McCool was one of the six men from the Ulster Rifles that you have mentioned on your website. He is the handsome chap pictured in the middle row of the photograph from Saugor (seen in the gallery below) showing men holding bunches of bananas. I would very much like to send you some more information about him and his time during the war. He was a wonderful man and had nine children and thirty grandchildren and was a successful chef who made such incredible curries. Granda died several years ago now, but his spirit is always with me. I can't thank you enough for giving me the chance to honour such a special man.

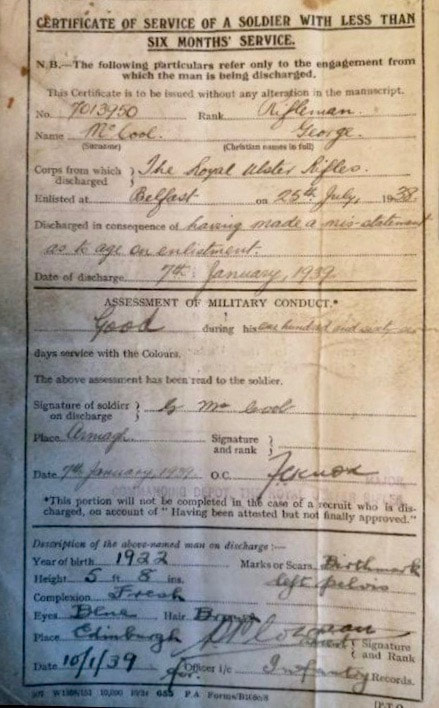

Marieanne told me that George was born in Londonderry on 30th April 1922, but had enlisted into the Army originally underage, at Belfast on the 25th July 1938. This was discovered the following year and he was forced to re-enlist in 1939. On his service records it states that George was 5’ 8’ tall with a fair complexion and blue eyes and that his overall conduct during his time in the Army was Good. In regards to his service in Burma with No. 8 Column under Major Scott, this has already been described in detail within the narrative above this update.

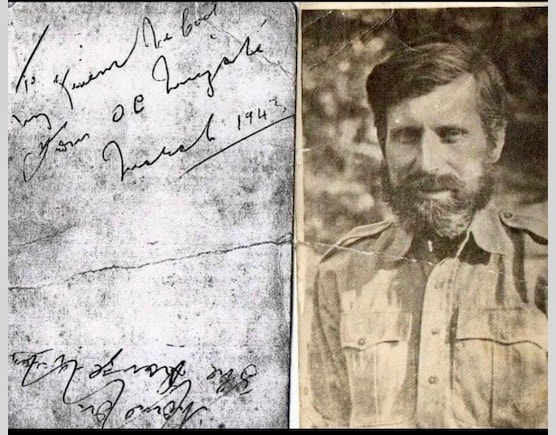

He was awarded the Operation Longcloth participation certificate by Lt-Colonel Cooke after the expedition and the family also possess a short note and photograph given to George by Brigadier Wingate in March 1943 (seen in the gallery of images below). Although the family did not know exactly what George was involved with in Burma at the time, they did find out that he had survived the first Wingate expedition in May 1943, when they heard his name mentioned on a radio message from India, delivered by the forces sweetheart, Vera Lynn.

George also kept a diary in relation to his time in India and Burma. Transcribed below is a short extract describing the lead up to the march into Burma in mid-February 1943:

Army Correspondence book 152/Staff Sergeant G. McCool-No. 16 Platoon

25th November 1943.

Adventures

Today, 2nd February 1943, as the sun shines over Impala (Imphal) the little town and the last one between Assam and Burma, we have arrived at a camp for a well earned rest. We have marched up from Dimapur, which is the rail head to here, a distance of 260 miles. It took us fifteen days to get here and everyone of us is looking forward to the rest.

Before this we had just completed six months hard training that was new to India and new to us. Our Brigade commander was Charles Orde Wingate, who was then just another commander, like many we had known in India. But his way with men and method of doing things was completely different. He was cruel at times; when he would give orders to officers and they were not carried out right he would be like a lion, then the next time you would see him, he was like a child. At that time nobody could have had any doubt about the special leader who commanded us. However, one doubt was where we were bound for in Burma, possibly some of the islands on which the Japanese had dug themselves in. But (at that time) nobody could be sure as to where we were going!

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this update, including some of the photographs mentioned above. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. I would like to thank Marieanne and her family for contacting me and adding so much to the story of Sergeant George McCool.

I was delighted to receive the follow email in February 2022 from Marieanne Holbourne, one of George McCool's granddaughters:

Hi Steve, my grandad George McCool was one of the six men from the Ulster Rifles that you have mentioned on your website. He is the handsome chap pictured in the middle row of the photograph from Saugor (seen in the gallery below) showing men holding bunches of bananas. I would very much like to send you some more information about him and his time during the war. He was a wonderful man and had nine children and thirty grandchildren and was a successful chef who made such incredible curries. Granda died several years ago now, but his spirit is always with me. I can't thank you enough for giving me the chance to honour such a special man.

Marieanne told me that George was born in Londonderry on 30th April 1922, but had enlisted into the Army originally underage, at Belfast on the 25th July 1938. This was discovered the following year and he was forced to re-enlist in 1939. On his service records it states that George was 5’ 8’ tall with a fair complexion and blue eyes and that his overall conduct during his time in the Army was Good. In regards to his service in Burma with No. 8 Column under Major Scott, this has already been described in detail within the narrative above this update.

He was awarded the Operation Longcloth participation certificate by Lt-Colonel Cooke after the expedition and the family also possess a short note and photograph given to George by Brigadier Wingate in March 1943 (seen in the gallery of images below). Although the family did not know exactly what George was involved with in Burma at the time, they did find out that he had survived the first Wingate expedition in May 1943, when they heard his name mentioned on a radio message from India, delivered by the forces sweetheart, Vera Lynn.

George also kept a diary in relation to his time in India and Burma. Transcribed below is a short extract describing the lead up to the march into Burma in mid-February 1943:

Army Correspondence book 152/Staff Sergeant G. McCool-No. 16 Platoon

25th November 1943.

Adventures

Today, 2nd February 1943, as the sun shines over Impala (Imphal) the little town and the last one between Assam and Burma, we have arrived at a camp for a well earned rest. We have marched up from Dimapur, which is the rail head to here, a distance of 260 miles. It took us fifteen days to get here and everyone of us is looking forward to the rest.

Before this we had just completed six months hard training that was new to India and new to us. Our Brigade commander was Charles Orde Wingate, who was then just another commander, like many we had known in India. But his way with men and method of doing things was completely different. He was cruel at times; when he would give orders to officers and they were not carried out right he would be like a lion, then the next time you would see him, he was like a child. At that time nobody could have had any doubt about the special leader who commanded us. However, one doubt was where we were bound for in Burma, possibly some of the islands on which the Japanese had dug themselves in. But (at that time) nobody could be sure as to where we were going!

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this update, including some of the photographs mentioned above. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. I would like to thank Marieanne and her family for contacting me and adding so much to the story of Sergeant George McCool.

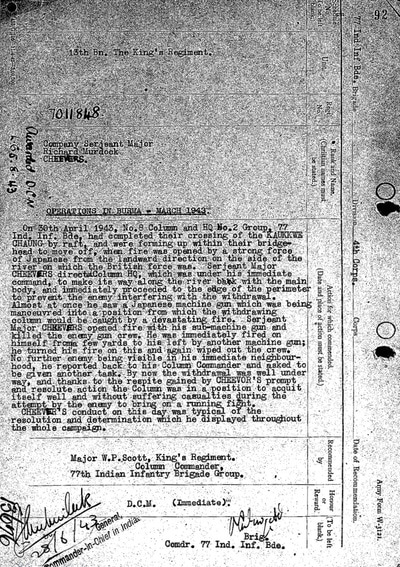

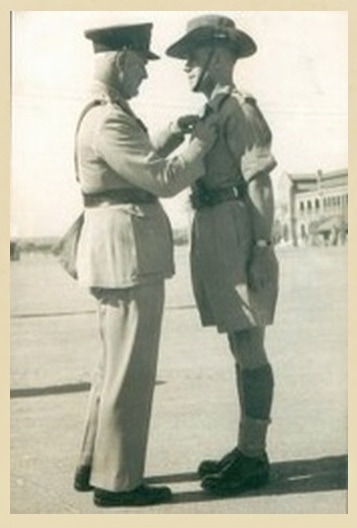

CSM 7011848 Richard Murdock Cheevers

“A rascal of a man.” This was how Georgina Livingstone, wife of RSM William James Livingstone, affectionately described one of her husband’s best pals from his days with the Chindits in 1943.

Cheevers was another member of 8 Column on Operation Longcloth and much like Lance Sergeant McCool, had witnessed the incredible air rescue of 18 of his comrades at Sonpu on the 28th April. Cheevers had also played a very strong and important role during the battle two days later at the Kaukkwe Chaung and for his efforts there he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

From the book, Wingate’s Phantom Army comes this description of the events at the Kaukkwe Chaung on the 30th April 1943:

Two Irish Sergeants, Cheevers and Delaney had sections amongst the bridgeheads established in the jungle, and they began fighting back desperately. A subaltern alongside Cheevers dropped dead, and a Jap poked his head through the undergrowth to make sure of his kill. Cheevers stitched him to a tree with his Tommy-gun, shouting "Take that, ye black-hearted bastard."

Seven Japs rushed to drag back the body, and Cheevers swearing profusely cut four of them down; the rest ran back. Major Scott ordered the men to try and break through to the left, but the Japs were strongly entrenched there with heavy machine-guns and there was no chance that way. The Japs formed up for a bayonet charge—as far as I know the only one during the whole of the Wingate expedition—to wipe out Delaney's section on the left flank. Delaney quickly shoved a Bren gun into position. The Japs rushed them, howling and screaming, but stopped after 5 yards as suddenly as if they had hit a brick wall when the Bren opened up. Those who survived yelled even louder as they turned tail and dashed for cover.

Scott tried edging round to the right flank, and found it was unguarded so word was passed back and the dispersal signal given. While Cheevers and Delaney held the Japs at bay, the rest at the water's edge hugged the bank and with their heads well down, worked around to the right. Scott found a company sergeant major wounded by the bank, and started to lift him on to his back, but the C.S.M. (Robert Glasgow) begged not to be moved.

After the engagement was over, Delaney took one party out to India, the regimental sergeant major (William James Livingstone) another, and Major Scott a third. Most of the men had lost their packs at the river. By the time they had divided up what was left, instead of 14 days' good rations, they only had 2 days' per man, and no possibility of further droppings.

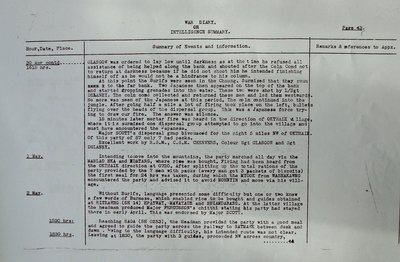

After the operation was over, Major Scott recommended CSM Cheevers be awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his brave deeds at the Kaukkwe Chaung. This recommendation was readily agreed by Brigadier Wingate and was announced in the London Gazette on the 5th August 1943. The citation read:

Regimental No. 7011848

Rank and Name: Company Sergeant-Major Richard Murdock Cheevers

Action for which recommended: -

OPERATIONS IN BURMA - MARCH 1943

On 30th April 1943, No.8 Column and HQ No.2 Group, 77 Indian Infantry Brigade had completed their crossing of the Kaukkwe Chaung by raft, and were forming up within their bridgehead to move off, when fire was opened by a strong force of Japanese from the landward direction on the side of the river on which the British force was.

Sergeant Major Cheevers directed Column HQ, which was under his immediate command, to make its way along the riverbank with the main body, and immediately proceeded to the edge of the perimeter to prevent the enemy interfering with the withdrawal. Almost at once he saw a Japanese machine gun which was being manoeuvred into a position from which the withdrawing column would be caught by a devastating fire.

Sergeant Major Cheevers opened fire with his sub-machine gun and killed the enemy gun crew. He was immediately fired on himself from a few yards to his left by another machine gun; he turned his fire on this and again wiped out the crew. No further enemy being visible in his immediate neighbourhood, he reported back to his Column Commander and asked to be given another task. By now the withdrawal was well under way, and thanks to the respite gained by Cheevers’ prompt and resolute action the Column was in a position to acquit itself well and without suffering casualties during the attempt by the enemy to bring on a running fight.

Cheevers’ conduct on this day was typical of the resolution and determination, which he had displayed throughout the whole campaign.

Back in India, Richard Cheevers, much like Lance Sergeant McCool before him, undertook to supply as much information as possible about the men who had not returned from the operation in 1943. On the 13th March 1944, Cheevers received his DCM from Viceroy Archibald Wavell at an investiture at the Napier Barracks in Karachi.

“A rascal of a man.” This was how Georgina Livingstone, wife of RSM William James Livingstone, affectionately described one of her husband’s best pals from his days with the Chindits in 1943.

Cheevers was another member of 8 Column on Operation Longcloth and much like Lance Sergeant McCool, had witnessed the incredible air rescue of 18 of his comrades at Sonpu on the 28th April. Cheevers had also played a very strong and important role during the battle two days later at the Kaukkwe Chaung and for his efforts there he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

From the book, Wingate’s Phantom Army comes this description of the events at the Kaukkwe Chaung on the 30th April 1943:

Two Irish Sergeants, Cheevers and Delaney had sections amongst the bridgeheads established in the jungle, and they began fighting back desperately. A subaltern alongside Cheevers dropped dead, and a Jap poked his head through the undergrowth to make sure of his kill. Cheevers stitched him to a tree with his Tommy-gun, shouting "Take that, ye black-hearted bastard."

Seven Japs rushed to drag back the body, and Cheevers swearing profusely cut four of them down; the rest ran back. Major Scott ordered the men to try and break through to the left, but the Japs were strongly entrenched there with heavy machine-guns and there was no chance that way. The Japs formed up for a bayonet charge—as far as I know the only one during the whole of the Wingate expedition—to wipe out Delaney's section on the left flank. Delaney quickly shoved a Bren gun into position. The Japs rushed them, howling and screaming, but stopped after 5 yards as suddenly as if they had hit a brick wall when the Bren opened up. Those who survived yelled even louder as they turned tail and dashed for cover.

Scott tried edging round to the right flank, and found it was unguarded so word was passed back and the dispersal signal given. While Cheevers and Delaney held the Japs at bay, the rest at the water's edge hugged the bank and with their heads well down, worked around to the right. Scott found a company sergeant major wounded by the bank, and started to lift him on to his back, but the C.S.M. (Robert Glasgow) begged not to be moved.

After the engagement was over, Delaney took one party out to India, the regimental sergeant major (William James Livingstone) another, and Major Scott a third. Most of the men had lost their packs at the river. By the time they had divided up what was left, instead of 14 days' good rations, they only had 2 days' per man, and no possibility of further droppings.

After the operation was over, Major Scott recommended CSM Cheevers be awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his brave deeds at the Kaukkwe Chaung. This recommendation was readily agreed by Brigadier Wingate and was announced in the London Gazette on the 5th August 1943. The citation read:

Regimental No. 7011848

Rank and Name: Company Sergeant-Major Richard Murdock Cheevers

Action for which recommended: -

OPERATIONS IN BURMA - MARCH 1943

On 30th April 1943, No.8 Column and HQ No.2 Group, 77 Indian Infantry Brigade had completed their crossing of the Kaukkwe Chaung by raft, and were forming up within their bridgehead to move off, when fire was opened by a strong force of Japanese from the landward direction on the side of the river on which the British force was.

Sergeant Major Cheevers directed Column HQ, which was under his immediate command, to make its way along the riverbank with the main body, and immediately proceeded to the edge of the perimeter to prevent the enemy interfering with the withdrawal. Almost at once he saw a Japanese machine gun which was being manoeuvred into a position from which the withdrawing column would be caught by a devastating fire.

Sergeant Major Cheevers opened fire with his sub-machine gun and killed the enemy gun crew. He was immediately fired on himself from a few yards to his left by another machine gun; he turned his fire on this and again wiped out the crew. No further enemy being visible in his immediate neighbourhood, he reported back to his Column Commander and asked to be given another task. By now the withdrawal was well under way, and thanks to the respite gained by Cheevers’ prompt and resolute action the Column was in a position to acquit itself well and without suffering casualties during the attempt by the enemy to bring on a running fight.

Cheevers’ conduct on this day was typical of the resolution and determination, which he had displayed throughout the whole campaign.

Back in India, Richard Cheevers, much like Lance Sergeant McCool before him, undertook to supply as much information as possible about the men who had not returned from the operation in 1943. On the 13th March 1944, Cheevers received his DCM from Viceroy Archibald Wavell at an investiture at the Napier Barracks in Karachi.

RSM 7011253 William James Livingstone

William Livingstone was posted to the 13th Battalion, the King’s Regiment in July 1940, just before the unit moved to Glasgow and took possession of their new barracks at Jordan Hill College. Previously to this, William had served with the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Ulster Rifles in the Far East, India and the Middle East, but more of this later.

In early 1942, whilst serving with the 13th King’s he was promoted to Regimental Quarter Master Sergeant at Secunderabad in India. During the second half of the year and with many men leaving the battalion for various reasons, William was made up to Regimental Sergeant Major at the Chindit training camp in Saugor. William served with 8 Column on Operation Longcloth under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott and was awarded the Military Cross by Scott, for his services on the first Wingate expedition.

In order for William to be eligible for the award of the MC, Major Scott had promoted him to the rank of Lieutenant Quarter Master on the 12th November 1943. RSM Livingstone had been heavily involved during the battle at the Kaukkwe Chaung and was then ordered by Major Scott to lead out a large dispersal group after the engagement with the enemy and get them safely back to India. This he achieved in late May 1943.

Below is transcription of William Livingstone's MC citation, as published in the London Gazette on the 16th December 1943:

On 30th April, 1943, a dispersal group under the command of Major W.P. Scott, which had spent the day crossing the Kaukkwe Chaung on rafts, was forming up to continue its march when it was suddenly attacked by a strong Japanese patrol. Regimental Sergeant Major Livingstone instantly organised the troops in his immediate neighbourhood in a most gallant and spirited defence, engaging the enemy wherever they showed themselves, regardless of their superior strength and of their great superiority in automatic weapons.

By so doing, and by opening a heavy fire on the enemy whenever and wherever they showed themselves, he succeeded in holding a ring where by he helped to prevent a large number of non-swimmers from being thrust into the river by the Japanese attack. But for his resolute action the great majority of these men would have inevitably been either killed or drowned.

When the enemy transferred their attention to another part of the area, R.S.M. Livingstone was with difficulty dissuaded from following them through the thick jungle in an effort to reach them with the bayonet. Finally, becoming separated from the main body, he collected, organised and led a large party of troops through the Japanese lines to a safe area where he joined an officer and with him marched his men 150 miles to the Chindwin River.

Throughout the campaign his courage, bearing and endurance have been of a high order and an inspiration to British, Burmese and Gurkha ranks alike.

William Livingstone spent the rest of the war with the 13th King’s at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. He received his Military Cross at the same investiture as his good friend Richard Cheevers, accepting his Gallantry Medal from His Excellency the Viceroy Archibald Wavell on the 13th March 1944. According to battalion records, Lt. William Livingstone was ordered for repatriation to the United Kingdom on the 10th July 1945.

In 2008, I was incredibly fortunate to receive a first contact from Georgina Livingstone, William’s wife. We have since exchanged many letters and spoken with each other on the telephone on several occasions. Georgina very kindly put together the following résumé of William’s Army career:

Steve, I have done as much as I can, but I’m afraid that most of the personal anecdotes about Bill have now slipped my mind. Its 34 years since he died, and although so many memories constantly come to mind, there were never any significant tales that I remember. He never, ever spoke of that last long march out of Burma, not in any detail anyway. I’ve learned most of what I know from books and none of those really speak of his actual group.

Bill enlisted into the Royal Ulster Rifles on the 24th March 1930. His early days and years took him to places such as Palestine, Egypt and Hong Kong, then finally to India from where he was repatriated in early 1939. We married in April 1941.

He was, in spite of his rank and Army career, a quiet, but strong-minded man, a very hard working family man too. When he left the Army, sadly he never tried to contact even his closest friends. Times were hard then, and people just did not get around as much or meet up with old friends. He did join the Burma Star Association for a short while, but shift work meant he could not attend the meetings very often, so he gave that up.

If he talked to me at all about the Army and his travels, it was always to say how much he loved it and the good opportunities it gave him. However, I think Burma plus the long separation was enough, as he now had a wife and young son to look after, he was glad to settle down and enjoy a peaceful life. He did so love the Army and was proud of what his men and all the other Chindits achieved. He was saddened by the losses of so many good men, but was also a true believer in all Brigadier Wingate wanted to do.

I have tried to list all Bill’s postings, but it is a very rough guide:

Enlisted into the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Ulster Rifles at the Omagh Barracks in 1930. Then on to Victoria Barracks in Belfast, for training. Posted to Palestine, which Bill enjoyed very much, then on to Alexandria in Egypt. Then Hong Kong, which Bill told me was a very good posting, except that often you had to go up to Shanghai, which was not so good. The Regiment was very happy at Hong Kong, but did lose some men on operations.

Next was a short stay in India, the battalion were probably awaiting their troopship home and sailed from Bombay back to the UK. In 1940 the 13th King’s were formed in Wales, but soon went to the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow. The battalion was asked to perform garrison and coastal duties over the next period in place like Felixstowe, Ipswich (where they were stationed at the airport), Colchester (Cherry Tree Barracks) and Burford in Oxfordshire.

In late 1941 the men went to Blackburn in Lancashire, some of the men were very near home and took the opportunity to visit their families. It was at Blackburn that the battalion prepared for overseas duty and sailed from Liverpool on 7th December 1941 for India. They were stationed at Secunderabad at the Gough Barracks and performed garrison duties until Wingate came along. Bill was made up to Regimental Quarter Master Sergeant at Secunderabad.

During the second half of 1942 the battalion saw many changes of personnel, as men unfit for jungle training were transferred out. Bill was then made up to RSM. In February 1943 they went into Burma and behind enemy lines. He was in column number 8 with Scotty (Major Scott). On dispersal he led a small group of 20 men out of the jungle and was awarded the Military Cross and commissioned to Lieutenant Quarter Master. On his return to India Bill was hospitalised, then after recuperation, sent on extended leave.

After Operation Longcloth, the battalion was stationed in Karachi until the end of the war. In July 1945 Bill was offered a promotion to the rank of Captain if he stayed on in the Army. But he declined the offer and arrived home via Southampton on VJ Day.

Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to the above story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To read more about William Livingstone, please click on the following link: Family 2

William Livingstone was posted to the 13th Battalion, the King’s Regiment in July 1940, just before the unit moved to Glasgow and took possession of their new barracks at Jordan Hill College. Previously to this, William had served with the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Ulster Rifles in the Far East, India and the Middle East, but more of this later.

In early 1942, whilst serving with the 13th King’s he was promoted to Regimental Quarter Master Sergeant at Secunderabad in India. During the second half of the year and with many men leaving the battalion for various reasons, William was made up to Regimental Sergeant Major at the Chindit training camp in Saugor. William served with 8 Column on Operation Longcloth under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott and was awarded the Military Cross by Scott, for his services on the first Wingate expedition.

In order for William to be eligible for the award of the MC, Major Scott had promoted him to the rank of Lieutenant Quarter Master on the 12th November 1943. RSM Livingstone had been heavily involved during the battle at the Kaukkwe Chaung and was then ordered by Major Scott to lead out a large dispersal group after the engagement with the enemy and get them safely back to India. This he achieved in late May 1943.

Below is transcription of William Livingstone's MC citation, as published in the London Gazette on the 16th December 1943:

On 30th April, 1943, a dispersal group under the command of Major W.P. Scott, which had spent the day crossing the Kaukkwe Chaung on rafts, was forming up to continue its march when it was suddenly attacked by a strong Japanese patrol. Regimental Sergeant Major Livingstone instantly organised the troops in his immediate neighbourhood in a most gallant and spirited defence, engaging the enemy wherever they showed themselves, regardless of their superior strength and of their great superiority in automatic weapons.

By so doing, and by opening a heavy fire on the enemy whenever and wherever they showed themselves, he succeeded in holding a ring where by he helped to prevent a large number of non-swimmers from being thrust into the river by the Japanese attack. But for his resolute action the great majority of these men would have inevitably been either killed or drowned.

When the enemy transferred their attention to another part of the area, R.S.M. Livingstone was with difficulty dissuaded from following them through the thick jungle in an effort to reach them with the bayonet. Finally, becoming separated from the main body, he collected, organised and led a large party of troops through the Japanese lines to a safe area where he joined an officer and with him marched his men 150 miles to the Chindwin River.

Throughout the campaign his courage, bearing and endurance have been of a high order and an inspiration to British, Burmese and Gurkha ranks alike.

William Livingstone spent the rest of the war with the 13th King’s at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. He received his Military Cross at the same investiture as his good friend Richard Cheevers, accepting his Gallantry Medal from His Excellency the Viceroy Archibald Wavell on the 13th March 1944. According to battalion records, Lt. William Livingstone was ordered for repatriation to the United Kingdom on the 10th July 1945.

In 2008, I was incredibly fortunate to receive a first contact from Georgina Livingstone, William’s wife. We have since exchanged many letters and spoken with each other on the telephone on several occasions. Georgina very kindly put together the following résumé of William’s Army career:

Steve, I have done as much as I can, but I’m afraid that most of the personal anecdotes about Bill have now slipped my mind. Its 34 years since he died, and although so many memories constantly come to mind, there were never any significant tales that I remember. He never, ever spoke of that last long march out of Burma, not in any detail anyway. I’ve learned most of what I know from books and none of those really speak of his actual group.

Bill enlisted into the Royal Ulster Rifles on the 24th March 1930. His early days and years took him to places such as Palestine, Egypt and Hong Kong, then finally to India from where he was repatriated in early 1939. We married in April 1941.

He was, in spite of his rank and Army career, a quiet, but strong-minded man, a very hard working family man too. When he left the Army, sadly he never tried to contact even his closest friends. Times were hard then, and people just did not get around as much or meet up with old friends. He did join the Burma Star Association for a short while, but shift work meant he could not attend the meetings very often, so he gave that up.

If he talked to me at all about the Army and his travels, it was always to say how much he loved it and the good opportunities it gave him. However, I think Burma plus the long separation was enough, as he now had a wife and young son to look after, he was glad to settle down and enjoy a peaceful life. He did so love the Army and was proud of what his men and all the other Chindits achieved. He was saddened by the losses of so many good men, but was also a true believer in all Brigadier Wingate wanted to do.

I have tried to list all Bill’s postings, but it is a very rough guide:

Enlisted into the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Ulster Rifles at the Omagh Barracks in 1930. Then on to Victoria Barracks in Belfast, for training. Posted to Palestine, which Bill enjoyed very much, then on to Alexandria in Egypt. Then Hong Kong, which Bill told me was a very good posting, except that often you had to go up to Shanghai, which was not so good. The Regiment was very happy at Hong Kong, but did lose some men on operations.

Next was a short stay in India, the battalion were probably awaiting their troopship home and sailed from Bombay back to the UK. In 1940 the 13th King’s were formed in Wales, but soon went to the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow. The battalion was asked to perform garrison and coastal duties over the next period in place like Felixstowe, Ipswich (where they were stationed at the airport), Colchester (Cherry Tree Barracks) and Burford in Oxfordshire.

In late 1941 the men went to Blackburn in Lancashire, some of the men were very near home and took the opportunity to visit their families. It was at Blackburn that the battalion prepared for overseas duty and sailed from Liverpool on 7th December 1941 for India. They were stationed at Secunderabad at the Gough Barracks and performed garrison duties until Wingate came along. Bill was made up to Regimental Quarter Master Sergeant at Secunderabad.

During the second half of 1942 the battalion saw many changes of personnel, as men unfit for jungle training were transferred out. Bill was then made up to RSM. In February 1943 they went into Burma and behind enemy lines. He was in column number 8 with Scotty (Major Scott). On dispersal he led a small group of 20 men out of the jungle and was awarded the Military Cross and commissioned to Lieutenant Quarter Master. On his return to India Bill was hospitalised, then after recuperation, sent on extended leave.

After Operation Longcloth, the battalion was stationed in Karachi until the end of the war. In July 1945 Bill was offered a promotion to the rank of Captain if he stayed on in the Army. But he declined the offer and arrived home via Southampton on VJ Day.

Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to the above story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To read more about William Livingstone, please click on the following link: Family 2

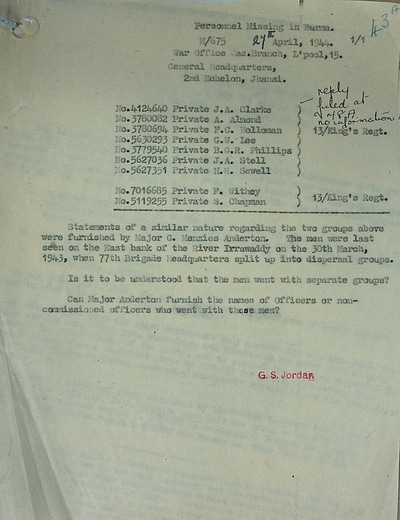

Pte. 7016685 Francis Withey

Pte. Francis 'Frankie' Withey was the son of John Henry and Caroline Louise Withey from Tufnell Park in London. According to his Army number Francis served originally with the Royal Ulster Rifles, before being transferred to the 13th King's Liverpool, probably sometime before the battalion left for overseas duty in India. He was a member of C' Company within the King's which duly comprised 7 Column once Chindit training began in mid-1942.

7 Column were led by Major Kenneth Gilkes during Operation Longcloth. Gilkes was a well-liked and respected leader, who would never ask a man to perform a duty that he would not be willing to carry out himself. Generally speaking the column shadowed Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters for much of their time in Burma, but, was often split up into smaller sub-units in order to perform various tasks required by Wingate as the operation unfolded in 1943.

By late March 1943, Columns 7 and 8 along with Wingate's Brigade HQ had reached the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River, close to the village of Inywa. The order to return to India had been given and Wingate proposed that the three units attempt to re-cross the river together at this point, judging that the Japanese would not expect them to return to the same place they had used previously on the outward journey. He was sadly mistaken.

The Japanese were waiting on the opposite bank and attacked the lead Chindit boats with machine gun and mortar fire. Many men were killed and the river crossing had to be abandoned. According to the missing in action reports for the 13th King's in 1943, this was the last time that Pte. Francis Withey was recorded as being with his unit.

There follows a transcription of a missing in action report in concern of Pte. Withey. It was written by Major G. Menzies-Anderson of the 13th King's Regiment. Anderson was the Brigade-Major in Wingate's HQ and he states in his report that Francis Withey along with another man, Pte. Stanley Chapman were both attached to the Brigade HQ from their original placements in 7 Column.

Statement of evidence in accordance with Battalion Instruction no. K 089019, dated 24/07/1943 in respect of:

No. 5119255 Pte. S. Chapman and No. 7016685 Pte. F. Withey.

The above men were attached to HQ 77th Indian Infantry Brigade during the operation in Burma. I was acting Brigade-Major. I last saw them on the east bank of the Irrawaddy on the 30th March 1943, when Brigade HQ split up into dispersal groups. They went with one of these groups and they have not yet reported back to India.

So, it would seem from Menzies-Anderson's account, that Withey and Chapman were not part of the group who attempted to cross the river at Inywa, but had been allocated into a dispersal group and headed off, probably in a south-easterly direction, away from the Irrawaddy in order to escape the enemy, who were by now closing in on the ailing Chindits.

From the official missing in action listings for the 13th King's, both Withey and Chapman are stated as last seen on the 31st March 1943. Nothing more is known about these men or which dispersal group they were allocated to on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. What we do know however is that both men were captured by the Japanese and became prisoners of war. By late May or early June they were being held with the rest of the Chindit POW's in Rangoon Central Jail.

Ptes. Withey and Chapman were held in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail and sadly this is where they both perished, Stanley Chapman on the 20th October 1943 and Francis Withey just over three months later on the 29th January 1944. There are no POW index cards for either man, but we do know from the recorded death lists for Block 6 that their POW numbers were 540 (Chapman) and 554 for Francis Withey.

Francis Withey was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery, just a few short miles from the jail and close to the Royal Lakes in the eastern sector of the city. This is where the majority of the Chindit casualties who died in Rangoon Jail were buried during the two years between May 1943 and April 1945. After the war was over the Imperial War Graves Commission moved all these graves over to the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery.

From further research I have discovered that Frank was a very accomplished amateur boxer in the years before WW2. In 1938 he reached the final of the Amateur Boxing Association National Championships held at the Royal Albert Hall. Fighting in the 'Featherweight' class, Frank defeated D.M. Cameron of England in the preliminary rounds, before beating fellow countrymen, J. Oberg and Albert Ives on points in the following two matches. All these first three bouts took place on April 6th. The next day, April 7th, Frank contested the final against Welshman, Cyril Gallie. Gallie proved too strong for Frank, who sadly lost the final on a TKO or technical knockout.

In August 2013 Elizabeth Withey, the great niece of Pte. Francis Withey made contact with me via email. This is what she told me:

Dear Steve

Thank you so much for all of this information. As you can imagine it is quite emotional to see the actual drawings and photographs and yet it is comforting too. I never knew Frank but grew up sensing the profound impact of his loss on the family, but because of the devastation of the war little was discussed back then, it was too upsetting and of course there was this sense that everyone around had experienced it as well and therefore everyone had to "just carry on.”

I am so impressed by your website and the extensive research you have done to honour your grandfather and grandmother. Your mission is exactly what I am interested in, the humanity behind the military procedures. Much like your own mission, I feel this sense of wanting to find out any personal anecdotes about Francis. I only wished I'd started sooner when there were more of the returning Chindits still alive.

Do you know of anyone who might have known Frankie (as his siblings called him) or might remember him? I realize this is a long shot. My reaction to the original hand written notes of when he went missing was quite something. To see something beyond official records was incredible, so thank you for that.

I will speak to my Dad and see what additional information he might have. I believe he has a photograph. For now, here is what I can tell you about Francis Withey:

He was from Kentish Town, in North London. The son of John and Caroline Withey. Frankie was one of 9 (4 boys and 5 girls). He was the youngest brother and I am pretty sure the youngest child. He was an amateur boxer at the Gainsford Boxing Club in Covent Garden. I have been told that he was a very good boxer and there was discussion of him going to the Olympics, however the war broke out and the Olympics were cancelled. My father has Frank's boxing trophies and medals; he also has his Burma Star medal that was awarded to him.

My Great Aunt Vi, Frankie's elder sister told me in the mid-1990's that for ages during the war years they didn't have word as to his whereabouts. When soldiers returned and there were parades in the streets of London, they would go out and ask for any information about him. On one occasion in one such parade they found someone from East London who had been with him and were told he had died of dysentery. They were also told that the Japanese would often challenge Frank and were quite rough with him because they knew about his boxing history.

She knew Frank had been in the Chindits, what I don't know is if she found that out after the war or during the war. I have also wondered if he really died of dysentery or if that is what the family was told to "soften the blow.” Three of Frankie's brothers were in the war and fortunately all three returned home, including my grandfather who had been in North Africa. He sadly died of a diabetic stroke at the age of 46 and this was always blamed on the poor war diet.

My father has a photo of the four brothers who all ran into each in North Africa and were together for a short while, this would be the last time they would ever see Uncle Frank. If I am able to get copies of the photos from my father I will certainly share them with you. Uncle Frank never married and never had children; he died before he had the chance.

Shown below is a Gallery of images in regards Pte. Frank Withey and his time with the Chindits, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Pte. Francis 'Frankie' Withey was the son of John Henry and Caroline Louise Withey from Tufnell Park in London. According to his Army number Francis served originally with the Royal Ulster Rifles, before being transferred to the 13th King's Liverpool, probably sometime before the battalion left for overseas duty in India. He was a member of C' Company within the King's which duly comprised 7 Column once Chindit training began in mid-1942.

7 Column were led by Major Kenneth Gilkes during Operation Longcloth. Gilkes was a well-liked and respected leader, who would never ask a man to perform a duty that he would not be willing to carry out himself. Generally speaking the column shadowed Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters for much of their time in Burma, but, was often split up into smaller sub-units in order to perform various tasks required by Wingate as the operation unfolded in 1943.

By late March 1943, Columns 7 and 8 along with Wingate's Brigade HQ had reached the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River, close to the village of Inywa. The order to return to India had been given and Wingate proposed that the three units attempt to re-cross the river together at this point, judging that the Japanese would not expect them to return to the same place they had used previously on the outward journey. He was sadly mistaken.

The Japanese were waiting on the opposite bank and attacked the lead Chindit boats with machine gun and mortar fire. Many men were killed and the river crossing had to be abandoned. According to the missing in action reports for the 13th King's in 1943, this was the last time that Pte. Francis Withey was recorded as being with his unit.

There follows a transcription of a missing in action report in concern of Pte. Withey. It was written by Major G. Menzies-Anderson of the 13th King's Regiment. Anderson was the Brigade-Major in Wingate's HQ and he states in his report that Francis Withey along with another man, Pte. Stanley Chapman were both attached to the Brigade HQ from their original placements in 7 Column.

Statement of evidence in accordance with Battalion Instruction no. K 089019, dated 24/07/1943 in respect of:

No. 5119255 Pte. S. Chapman and No. 7016685 Pte. F. Withey.

The above men were attached to HQ 77th Indian Infantry Brigade during the operation in Burma. I was acting Brigade-Major. I last saw them on the east bank of the Irrawaddy on the 30th March 1943, when Brigade HQ split up into dispersal groups. They went with one of these groups and they have not yet reported back to India.

So, it would seem from Menzies-Anderson's account, that Withey and Chapman were not part of the group who attempted to cross the river at Inywa, but had been allocated into a dispersal group and headed off, probably in a south-easterly direction, away from the Irrawaddy in order to escape the enemy, who were by now closing in on the ailing Chindits.

From the official missing in action listings for the 13th King's, both Withey and Chapman are stated as last seen on the 31st March 1943. Nothing more is known about these men or which dispersal group they were allocated to on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. What we do know however is that both men were captured by the Japanese and became prisoners of war. By late May or early June they were being held with the rest of the Chindit POW's in Rangoon Central Jail.

Ptes. Withey and Chapman were held in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail and sadly this is where they both perished, Stanley Chapman on the 20th October 1943 and Francis Withey just over three months later on the 29th January 1944. There are no POW index cards for either man, but we do know from the recorded death lists for Block 6 that their POW numbers were 540 (Chapman) and 554 for Francis Withey.

Francis Withey was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery, just a few short miles from the jail and close to the Royal Lakes in the eastern sector of the city. This is where the majority of the Chindit casualties who died in Rangoon Jail were buried during the two years between May 1943 and April 1945. After the war was over the Imperial War Graves Commission moved all these graves over to the newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery.

From further research I have discovered that Frank was a very accomplished amateur boxer in the years before WW2. In 1938 he reached the final of the Amateur Boxing Association National Championships held at the Royal Albert Hall. Fighting in the 'Featherweight' class, Frank defeated D.M. Cameron of England in the preliminary rounds, before beating fellow countrymen, J. Oberg and Albert Ives on points in the following two matches. All these first three bouts took place on April 6th. The next day, April 7th, Frank contested the final against Welshman, Cyril Gallie. Gallie proved too strong for Frank, who sadly lost the final on a TKO or technical knockout.

In August 2013 Elizabeth Withey, the great niece of Pte. Francis Withey made contact with me via email. This is what she told me:

Dear Steve

Thank you so much for all of this information. As you can imagine it is quite emotional to see the actual drawings and photographs and yet it is comforting too. I never knew Frank but grew up sensing the profound impact of his loss on the family, but because of the devastation of the war little was discussed back then, it was too upsetting and of course there was this sense that everyone around had experienced it as well and therefore everyone had to "just carry on.”

I am so impressed by your website and the extensive research you have done to honour your grandfather and grandmother. Your mission is exactly what I am interested in, the humanity behind the military procedures. Much like your own mission, I feel this sense of wanting to find out any personal anecdotes about Francis. I only wished I'd started sooner when there were more of the returning Chindits still alive.

Do you know of anyone who might have known Frankie (as his siblings called him) or might remember him? I realize this is a long shot. My reaction to the original hand written notes of when he went missing was quite something. To see something beyond official records was incredible, so thank you for that.

I will speak to my Dad and see what additional information he might have. I believe he has a photograph. For now, here is what I can tell you about Francis Withey:

He was from Kentish Town, in North London. The son of John and Caroline Withey. Frankie was one of 9 (4 boys and 5 girls). He was the youngest brother and I am pretty sure the youngest child. He was an amateur boxer at the Gainsford Boxing Club in Covent Garden. I have been told that he was a very good boxer and there was discussion of him going to the Olympics, however the war broke out and the Olympics were cancelled. My father has Frank's boxing trophies and medals; he also has his Burma Star medal that was awarded to him.

My Great Aunt Vi, Frankie's elder sister told me in the mid-1990's that for ages during the war years they didn't have word as to his whereabouts. When soldiers returned and there were parades in the streets of London, they would go out and ask for any information about him. On one occasion in one such parade they found someone from East London who had been with him and were told he had died of dysentery. They were also told that the Japanese would often challenge Frank and were quite rough with him because they knew about his boxing history.

She knew Frank had been in the Chindits, what I don't know is if she found that out after the war or during the war. I have also wondered if he really died of dysentery or if that is what the family was told to "soften the blow.” Three of Frankie's brothers were in the war and fortunately all three returned home, including my grandfather who had been in North Africa. He sadly died of a diabetic stroke at the age of 46 and this was always blamed on the poor war diet.

My father has a photo of the four brothers who all ran into each in North Africa and were together for a short while, this would be the last time they would ever see Uncle Frank. If I am able to get copies of the photos from my father I will certainly share them with you. Uncle Frank never married and never had children; he died before he had the chance.

Shown below is a Gallery of images in regards Pte. Frank Withey and his time with the Chindits, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 17/01/2023.

I was delighted recently (December 2022) to receive another email (via the Chindit Society) from Elizabeth Withey-Vandiver:

Hello Steve,

I hope this email finds you well. Several years ago I wrote to you about my great uncle Francis Withey who was a Chindit and part of Operation Longcloth. In the time since we last communicated have you possibly discovered any additional information? I noticed that a woman wrote to you about her grandfather and had a journal. Is Frankie possibly mentioned in it or another journal? I believe I shared with you that I took my husband and two young sons to Myanmar back in 2017, as it turned out days before the genocide began. We were the first and possibly will be the only relatives to ever visit his grave. It was thanks to you and your information we were able to find it. Thank you! If any information about Francis Withey surfaces will you please let me know? Your work is so important and deeply impactful.

I replied:

Hello Elizabeth,

It was wonderful to hear from you again and I hope you and the family are well. There has not been any more information about Frank I'm afraid. The journals you mention were of interest but did not refer to him or the other men originally from the Royal Ulster Rifles. I wondered if you might like to write a couple of paragraphs about your family's visit to Rangoon, which I could then add to Frank's story on my website as an update. Let me know your thoughts and thank you once again for your message.

Seasons Greetings, Steve.

I hope to hear from Elizabeth again soon.

I was delighted recently (December 2022) to receive another email (via the Chindit Society) from Elizabeth Withey-Vandiver:

Hello Steve,

I hope this email finds you well. Several years ago I wrote to you about my great uncle Francis Withey who was a Chindit and part of Operation Longcloth. In the time since we last communicated have you possibly discovered any additional information? I noticed that a woman wrote to you about her grandfather and had a journal. Is Frankie possibly mentioned in it or another journal? I believe I shared with you that I took my husband and two young sons to Myanmar back in 2017, as it turned out days before the genocide began. We were the first and possibly will be the only relatives to ever visit his grave. It was thanks to you and your information we were able to find it. Thank you! If any information about Francis Withey surfaces will you please let me know? Your work is so important and deeply impactful.

I replied:

Hello Elizabeth,

It was wonderful to hear from you again and I hope you and the family are well. There has not been any more information about Frank I'm afraid. The journals you mention were of interest but did not refer to him or the other men originally from the Royal Ulster Rifles. I wondered if you might like to write a couple of paragraphs about your family's visit to Rangoon, which I could then add to Frank's story on my website as an update. Let me know your thoughts and thank you once again for your message.

Seasons Greetings, Steve.

I hope to hear from Elizabeth again soon.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, May 2017.