The Courageous Sergeant Hayes

The cap badge of the RAF.

The cap badge of the RAF.

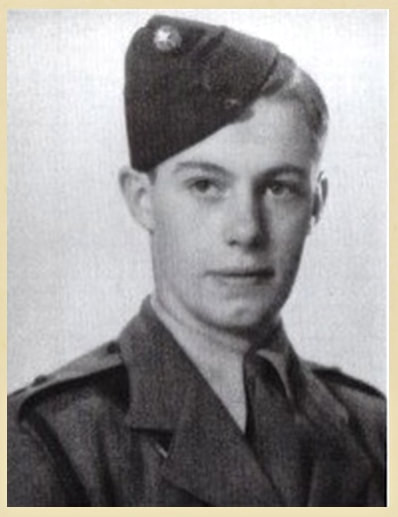

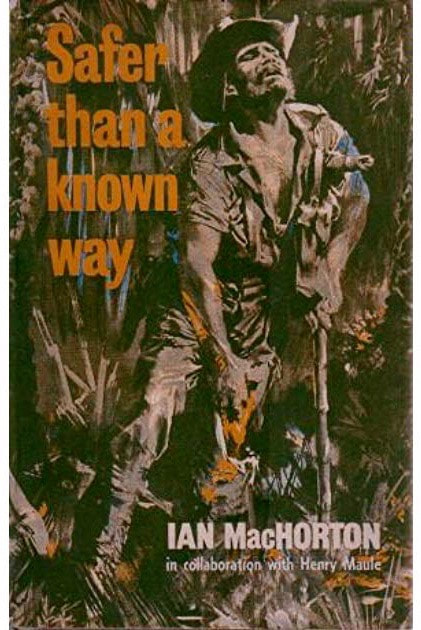

In the book, Safer Than a Known Way, by Gurkha officer, Lieutenant Ian MacHorton, there is mention of a Corporal from No. 2 Column, who meets up with Lt. MacHorton on the dispersal journey back to India in April 1943. The Corporal remains unnamed in the book, but is portrayed as a colourful character, full of charm and good humour:

The Corporal was a likeable character who seemed to know everyone in the column. The skin on his face and neck and arms, and of every part of his body that could be seen through the many rents in his tattered uniform, was burned so black by the sun, that he was darker even than a native Burmese. His battered felt hat had all, and more, of the quality of batteredness so much courted by the British soldier wearing the coveted bush-hat of the Burma Campaign. But although the bush-hat was designed specifically for keeping the sun out of the eyes, he insisted on wearing his so far back on his head, that it was difficult to see how it remained there at all. He was made for sunshine was that Corporal.

Sadly, the Corporal did not make back to India and was killed around the end of April, beginning of May 1943, whilst crossing the Mu River with Lt. MacHorton:

As we crossed the river the Corporal was shouting abuse at the Japs with almost gay abandon. The water now was only knee deep and less and less it retarded our frantic movement forward. The zip and whine of bullets from behind spurred us on. From ahead came the screech and crack of Jap machine-guns and rifles. The body of a British soldier swirled past me on the swift current, the water around him pink with his blood. A Gurkha in front of me slipped quietly into the water without a sound, but on we lurched in spite of the bullets.

Suddenly we were clear of the water and belting hell-for-leather up the sandy bank. The Corporal, less than six feet ahead of me, suddenly screamed in agony and somersaulted forward to lie kicking on the sand. Even had I the will to do so, I had no time to stop. I took a flying leap over his body, where a burst of light automatic fire had torn into him leaving blood gushing from his chest and throat.

By matching the place, circumstances and date of death, I believe the soldier in question could well have been Corporal James Boyce from Johnstone in Scotland, although of course this can never be confirmed at this late stage. To read more about this soldier, please click on the following link: Lance Corporal James Boyce

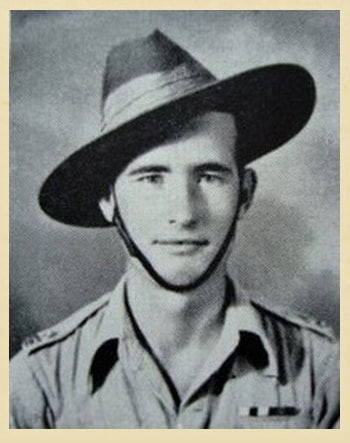

Another man to feature heavily in MacHorton's book was Sergeant Hayes of the RAF. This Chindit had served with No. 2 Column from the outset and had formed part of the column's Air Liaison Section. MacHorton meets up with the Sergeant on the western banks of the Irrawaddy River in late April 1943, after MacHorton had managed to rejoin the dispersing Chindits following his own enforced separation a few weeks earlier.

To read more about the incredible adventures of Lt. MacHorton during Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link:

Lt. MacHorton and the battle of Kyaikthin

Now, to set the scene. The majority of No. 1 Column, led by Major George Dunlop and Colonel Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander had crossed the Irrawaddy in two small country boats. Lt. MacHorton and some Gurkha Other Ranks were in the second from last boat to cross when the Japanese ambushed the Chindits causing them to abandon the vessel and swim ashore. Many men were killed and wounded during this engagement with the enemy and by the time MacHorton had escaped into the jungle adjacent to the west bank, only the above mentioned Corporal was alongside.

After finding a temporary hiding place in the thick-set bamboo, MacHorton and the corporal settle down to rest for a few hours to allow things to quieten down. When they decide to set off again they stumble across a group of quarrelling Chindits led by an RAF Sergeant.

From the pages of Safer Than a Known Way:

I walked straight up to the sergeant. As much as possible I strove to hide my limp and make my entry an authoritative one. I could not remember ever having seen the sergeant before, but apparently he recognized me. He straightened up, almost as if he were going to salute me, which would have been contrary to Chindits' battle regulation. He checked his instinctive move in time and said: "Hullo, sir!"

"The corporal and I have been sent back for you," I lied. "I am your Commanding Officer now. We are going back to India and should catch the rest of the column up soon." I could sense at once that my ready lie had had the desired effect on the men, even though the wary look in the sergeant's eyes told me he had not been taken in by my subterfuge. But his momentary suspicion gave place to a ready gratitude, which twinkled in his eyes although he said nothing. The rebellion had been quelled and the pathetic little band of wounded, almost at the end of their endurance, were once again a body of Wingate's Chindits, determined to carry out to the last letter his instructions. Heaven knows, they had already been through enough to weaken their morale. They could readily be forgiven losing their will to go on at this point. I looked around the little group of battle-stained and weary men. Above the stench of their sweat-sodden clothing, by now little more than rags, the air was rancid with the sweet-sour smell of dried blood and suppurating sores. Every one of them was wounded, or had fearful sores, that had eaten almost down to the very bone. Yes, they could be forgiven.

"What is your name, Sergeant!" I asked. "Hayes, sir. Of the R.A.F. section," he replied briskly. "How many men have you got with you?" I enquired. "Fourteen, sir. That includes the four Johnny Gurkhas." "Right then!" I ordered: "Let's get them sorted out so that we can get on our way." Quite apart from my personal eagerness to get moving westwards, I could see that these men had to be got going quickly.

The burly R.A.F. sergeant then took me on a brief conducted tour of his little party. We found that two of the Gurkhas, and one British soldier lying on the ground in the moonlight, had died even as they rested there. The British soldier, his sightless eyes glistening in the moonlight, was grinning horribly at us. It was as though in his very last conscious moment he had seen in my terse assertion that we would march to India some quite ridiculous and impossible joke. I had never before experienced dumb insolence from a dead man.

Of the rest, two were very badly wounded in the chest and could not walk in any circumstances. The remaining nine men, although all hit by Jap bullets, could at least hobble along. Sergeant Hayes was probably the worst wounded of all the walking cases, although he had neither said anything about his wounds nor had anything but scorn for suggestions of giving in. The arm which was supported in the sling had been almost smashed by a burst of Jap machine-gun fire. A long bloody gash which had split his face cruelly told of the savage close-combat fighting in which he had been embroiled. He never flinched nor murmured, although he must have been in continuous pain.

"How did you all get here, Sergeant?" I asked him. "Well, sir," he replied: "I just got them together at the river crossing after we were fired on, and I brought 'em here."

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The Corporal was a likeable character who seemed to know everyone in the column. The skin on his face and neck and arms, and of every part of his body that could be seen through the many rents in his tattered uniform, was burned so black by the sun, that he was darker even than a native Burmese. His battered felt hat had all, and more, of the quality of batteredness so much courted by the British soldier wearing the coveted bush-hat of the Burma Campaign. But although the bush-hat was designed specifically for keeping the sun out of the eyes, he insisted on wearing his so far back on his head, that it was difficult to see how it remained there at all. He was made for sunshine was that Corporal.

Sadly, the Corporal did not make back to India and was killed around the end of April, beginning of May 1943, whilst crossing the Mu River with Lt. MacHorton:

As we crossed the river the Corporal was shouting abuse at the Japs with almost gay abandon. The water now was only knee deep and less and less it retarded our frantic movement forward. The zip and whine of bullets from behind spurred us on. From ahead came the screech and crack of Jap machine-guns and rifles. The body of a British soldier swirled past me on the swift current, the water around him pink with his blood. A Gurkha in front of me slipped quietly into the water without a sound, but on we lurched in spite of the bullets.

Suddenly we were clear of the water and belting hell-for-leather up the sandy bank. The Corporal, less than six feet ahead of me, suddenly screamed in agony and somersaulted forward to lie kicking on the sand. Even had I the will to do so, I had no time to stop. I took a flying leap over his body, where a burst of light automatic fire had torn into him leaving blood gushing from his chest and throat.

By matching the place, circumstances and date of death, I believe the soldier in question could well have been Corporal James Boyce from Johnstone in Scotland, although of course this can never be confirmed at this late stage. To read more about this soldier, please click on the following link: Lance Corporal James Boyce

Another man to feature heavily in MacHorton's book was Sergeant Hayes of the RAF. This Chindit had served with No. 2 Column from the outset and had formed part of the column's Air Liaison Section. MacHorton meets up with the Sergeant on the western banks of the Irrawaddy River in late April 1943, after MacHorton had managed to rejoin the dispersing Chindits following his own enforced separation a few weeks earlier.

To read more about the incredible adventures of Lt. MacHorton during Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link:

Lt. MacHorton and the battle of Kyaikthin

Now, to set the scene. The majority of No. 1 Column, led by Major George Dunlop and Colonel Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander had crossed the Irrawaddy in two small country boats. Lt. MacHorton and some Gurkha Other Ranks were in the second from last boat to cross when the Japanese ambushed the Chindits causing them to abandon the vessel and swim ashore. Many men were killed and wounded during this engagement with the enemy and by the time MacHorton had escaped into the jungle adjacent to the west bank, only the above mentioned Corporal was alongside.

After finding a temporary hiding place in the thick-set bamboo, MacHorton and the corporal settle down to rest for a few hours to allow things to quieten down. When they decide to set off again they stumble across a group of quarrelling Chindits led by an RAF Sergeant.

From the pages of Safer Than a Known Way:

I walked straight up to the sergeant. As much as possible I strove to hide my limp and make my entry an authoritative one. I could not remember ever having seen the sergeant before, but apparently he recognized me. He straightened up, almost as if he were going to salute me, which would have been contrary to Chindits' battle regulation. He checked his instinctive move in time and said: "Hullo, sir!"

"The corporal and I have been sent back for you," I lied. "I am your Commanding Officer now. We are going back to India and should catch the rest of the column up soon." I could sense at once that my ready lie had had the desired effect on the men, even though the wary look in the sergeant's eyes told me he had not been taken in by my subterfuge. But his momentary suspicion gave place to a ready gratitude, which twinkled in his eyes although he said nothing. The rebellion had been quelled and the pathetic little band of wounded, almost at the end of their endurance, were once again a body of Wingate's Chindits, determined to carry out to the last letter his instructions. Heaven knows, they had already been through enough to weaken their morale. They could readily be forgiven losing their will to go on at this point. I looked around the little group of battle-stained and weary men. Above the stench of their sweat-sodden clothing, by now little more than rags, the air was rancid with the sweet-sour smell of dried blood and suppurating sores. Every one of them was wounded, or had fearful sores, that had eaten almost down to the very bone. Yes, they could be forgiven.

"What is your name, Sergeant!" I asked. "Hayes, sir. Of the R.A.F. section," he replied briskly. "How many men have you got with you?" I enquired. "Fourteen, sir. That includes the four Johnny Gurkhas." "Right then!" I ordered: "Let's get them sorted out so that we can get on our way." Quite apart from my personal eagerness to get moving westwards, I could see that these men had to be got going quickly.

The burly R.A.F. sergeant then took me on a brief conducted tour of his little party. We found that two of the Gurkhas, and one British soldier lying on the ground in the moonlight, had died even as they rested there. The British soldier, his sightless eyes glistening in the moonlight, was grinning horribly at us. It was as though in his very last conscious moment he had seen in my terse assertion that we would march to India some quite ridiculous and impossible joke. I had never before experienced dumb insolence from a dead man.

Of the rest, two were very badly wounded in the chest and could not walk in any circumstances. The remaining nine men, although all hit by Jap bullets, could at least hobble along. Sergeant Hayes was probably the worst wounded of all the walking cases, although he had neither said anything about his wounds nor had anything but scorn for suggestions of giving in. The arm which was supported in the sling had been almost smashed by a burst of Jap machine-gun fire. A long bloody gash which had split his face cruelly told of the savage close-combat fighting in which he had been embroiled. He never flinched nor murmured, although he must have been in continuous pain.

"How did you all get here, Sergeant?" I asked him. "Well, sir," he replied: "I just got them together at the river crossing after we were fired on, and I brought 'em here."

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

MacHorton's book continues:

The full story of Sergeant Hayes' "just getting them together" I learned later. Instead of heading westwards, during the first lull in the battle, he had quite deliberately wandered all around the whole battle area, seeking out wounded British and Gurkha soldiers. One by one he had dragged them to the safety of the clearing in which I had found them. With great dash and bravery he had personally charged into a number of running fights going on in the jungle, and had pulled out wounded to save them from almost certain bayoneting, or capture and torture, by the Japs. It was while he was thus heroically engaged that he had been hit in the arm, but he had carried on.

I told Sergeant Hayes about the wounded man we had left on the hillock. "The poor devil!" said the sergeant with feeling. "He just went mad with the pain of his wounds and screamed out that he was going to go home. Then he rushed away into the jungle and that was the last I saw of him. I guessed the poor devil hadn't long to live so I let him go. I felt sure he would drop dead trying to fight his way through the jungle. It would be the kindest way out for him."

Then, in an undertone although we were out of earshot of the others, he added: "Thanks, sir, for stepping in then. I know you were only kidding about being sent back, but the others didn't tumble. It did the trick all right. Thanks a million."

With speed, remarkable considering its condition, the battered little band now organised itself for the march to India that I had promised them. Some of the men set to work to make two stretchers from bamboo poles and creepers. Sergeant Hayes and I set about sorting out the arms and ammunition and allocating them, so that each one of us could be as effective a fighting man as wounds and physical weakness permitted. Excepting for the two stretcher cases, there was a rifle for everyone. The ammunition worked out at 30 rounds per man. I swapped my revolver with Sergeant Hayes' rifle because it was obviously better that a man with two hands should have a rifle.

Then we set about rationing out the food. Our total provisions amounted to something like four pounds of rice, sufficient for one cupped handful to each man. We shared out the silver rupees with which we had been provided for buying provisions from friendly villagers. This gave each one of us 8 rupees. To point us the way ahead there was still my compass, while the corporal had his handkerchief map. The two together were quite ample for our purpose.

As soon as we were ready I told Sergeant Hayes to get his squad to their feet. Then I led off my new command—one R.A.F. sergeant, one corporal, and nine other ranks, including two Gurkhas, all who could walk. We stepped from the moonlit glade with its little sparkling stream out into the deepening darkness of the jungle. Once again we were on our way to the Chindwin River, and the safety of India beyond.

The group moved steadily west, but were obviously hampered by having to carry the wounded men upon the makeshift stretchers. In the end MacHorton and Hayes had no choice but to leave the stretcher cases with a friendly looking village situated along the route to the Chindwin River. The Sergeant carried his share of responsibility and was of great value to MacHorton; he would cover the Lieutenant when he entered Burmese villages in search of food and gave MacHorton sound advice and assistance with his map and compass work.

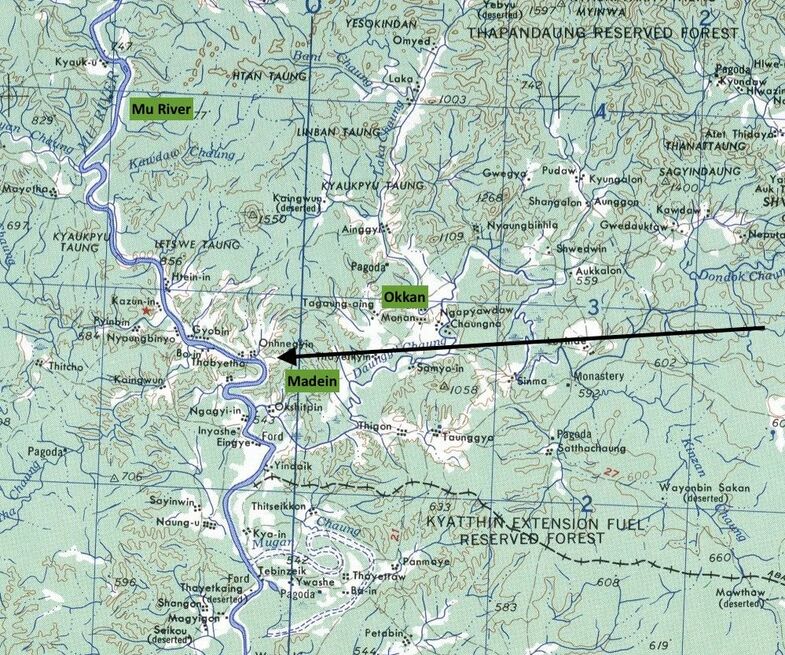

The small band of Chindits crossed over the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway in early May and then incredibly bumped the tail-end of No. 1 Column as it was preparing to cross the Mu River. Sadly, their luck ran out once again when the column was ambushed for a second time by the Japanese. The Chindits had no choice but to continue to cross the knee-deep stream with enemy machine gun and mortar raining in on them. It was at this juncture that the aforementioned Corporal was killed.

MacHorton remembered:

Once over the Mu there was no deep cover immediately around us. We were in open teak forest with low bushes dotting the sandy soil. We raced on. Through the trees I caught a glimpse of Eddie Edmonds dashing across a clearing with the inert figure of Colonel Alexander hanging limply over his shoulder. The Colonel was mottled red with his own blood and flopped about lifelessly over the powerful frame of Edmonds. Another figure—who it was I never made out clearly--running desperately behind him, suddenly slumped down in his tracks and rolled over and over. Eddie stopped for a moment, turning to look round, then carried on galloping through the trees with his load.

"This way," Eddie shouted, and I went lurching after him. Sergeant Hayes passed me, lumbering through the teak trees like a young bull elephant. All of us were going flat out. I gulped for breath. For no reason that I could discover I suddenly hit the ground with a thud. I sprawled out there, gasping. From where I lay, all the wind knocked out of me, I saw the backs of Sergeant Hayes and another soldier disappear into a thicker clump of bushes into which Eddie Edmonds had forced his way, still carrying Colonel Alexander. I started to crawl after them. I tried to shout "Wait!"—but couldn't. I gave up trying to fathom why I could only crawl. Suddenly an excruciating pain shot through my right knee and I felt my body twitch. Then a piercing pain came as a sheet of blinding light through body and mind and soul. Then there was only the most utter blackness, peaceful, timeless, and painless.

The full story of Sergeant Hayes' "just getting them together" I learned later. Instead of heading westwards, during the first lull in the battle, he had quite deliberately wandered all around the whole battle area, seeking out wounded British and Gurkha soldiers. One by one he had dragged them to the safety of the clearing in which I had found them. With great dash and bravery he had personally charged into a number of running fights going on in the jungle, and had pulled out wounded to save them from almost certain bayoneting, or capture and torture, by the Japs. It was while he was thus heroically engaged that he had been hit in the arm, but he had carried on.

I told Sergeant Hayes about the wounded man we had left on the hillock. "The poor devil!" said the sergeant with feeling. "He just went mad with the pain of his wounds and screamed out that he was going to go home. Then he rushed away into the jungle and that was the last I saw of him. I guessed the poor devil hadn't long to live so I let him go. I felt sure he would drop dead trying to fight his way through the jungle. It would be the kindest way out for him."

Then, in an undertone although we were out of earshot of the others, he added: "Thanks, sir, for stepping in then. I know you were only kidding about being sent back, but the others didn't tumble. It did the trick all right. Thanks a million."

With speed, remarkable considering its condition, the battered little band now organised itself for the march to India that I had promised them. Some of the men set to work to make two stretchers from bamboo poles and creepers. Sergeant Hayes and I set about sorting out the arms and ammunition and allocating them, so that each one of us could be as effective a fighting man as wounds and physical weakness permitted. Excepting for the two stretcher cases, there was a rifle for everyone. The ammunition worked out at 30 rounds per man. I swapped my revolver with Sergeant Hayes' rifle because it was obviously better that a man with two hands should have a rifle.

Then we set about rationing out the food. Our total provisions amounted to something like four pounds of rice, sufficient for one cupped handful to each man. We shared out the silver rupees with which we had been provided for buying provisions from friendly villagers. This gave each one of us 8 rupees. To point us the way ahead there was still my compass, while the corporal had his handkerchief map. The two together were quite ample for our purpose.

As soon as we were ready I told Sergeant Hayes to get his squad to their feet. Then I led off my new command—one R.A.F. sergeant, one corporal, and nine other ranks, including two Gurkhas, all who could walk. We stepped from the moonlit glade with its little sparkling stream out into the deepening darkness of the jungle. Once again we were on our way to the Chindwin River, and the safety of India beyond.

The group moved steadily west, but were obviously hampered by having to carry the wounded men upon the makeshift stretchers. In the end MacHorton and Hayes had no choice but to leave the stretcher cases with a friendly looking village situated along the route to the Chindwin River. The Sergeant carried his share of responsibility and was of great value to MacHorton; he would cover the Lieutenant when he entered Burmese villages in search of food and gave MacHorton sound advice and assistance with his map and compass work.

The small band of Chindits crossed over the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway in early May and then incredibly bumped the tail-end of No. 1 Column as it was preparing to cross the Mu River. Sadly, their luck ran out once again when the column was ambushed for a second time by the Japanese. The Chindits had no choice but to continue to cross the knee-deep stream with enemy machine gun and mortar raining in on them. It was at this juncture that the aforementioned Corporal was killed.

MacHorton remembered:

Once over the Mu there was no deep cover immediately around us. We were in open teak forest with low bushes dotting the sandy soil. We raced on. Through the trees I caught a glimpse of Eddie Edmonds dashing across a clearing with the inert figure of Colonel Alexander hanging limply over his shoulder. The Colonel was mottled red with his own blood and flopped about lifelessly over the powerful frame of Edmonds. Another figure—who it was I never made out clearly--running desperately behind him, suddenly slumped down in his tracks and rolled over and over. Eddie stopped for a moment, turning to look round, then carried on galloping through the trees with his load.

"This way," Eddie shouted, and I went lurching after him. Sergeant Hayes passed me, lumbering through the teak trees like a young bull elephant. All of us were going flat out. I gulped for breath. For no reason that I could discover I suddenly hit the ground with a thud. I sprawled out there, gasping. From where I lay, all the wind knocked out of me, I saw the backs of Sergeant Hayes and another soldier disappear into a thicker clump of bushes into which Eddie Edmonds had forced his way, still carrying Colonel Alexander. I started to crawl after them. I tried to shout "Wait!"—but couldn't. I gave up trying to fathom why I could only crawl. Suddenly an excruciating pain shot through my right knee and I felt my body twitch. Then a piercing pain came as a sheet of blinding light through body and mind and soul. Then there was only the most utter blackness, peaceful, timeless, and painless.

Only five of MacHorton's party survived the forced crossing of the Mu River and as explained above, Lt. MacHorton had been severely wounded and was unable to march any further; he would fall in to Japanese hands within a matter of hours. Major Dunlop, Sergeant Hayes and the now reduced number of Chindits from No. 1 Column continued their journey to the Chindwin.

Remarkably and with great fortune, Lt. MacHorton was taken by motor transport in a westward direction by his captors, towards the Chindwin and the Japanese garrison town of Kalewa. Before reaching the town he managed to effect an escape and moved off north keeping the river on his left hand side in the hope of reaching Allied held territory. A few days passed by and MacHorton now suffering from starvation, exhaustion and the agonies of his wounds was close to collapse. He stopped his journey by a small stream and took a long drink from the crystal clear water.

Then, amazingly, he noticed some 50 yards away, a group of ragged scarecrow looking men. It was the remnants of No. 1 Column still led by Major Dunlop. From the book, Safer Than a Known Way:

As I approached the depleted party I met John Griffiths: "Hullo, Ian. You again," he said. John was sitting beside a large man whose prostrate body seemed still well covered with flesh. The man was panting and the sweat stood out on his brow in great beads. One arm was swollen terribly and was supported in a sling. I now saw that his apparent bulk was nothing to do with the flesh on his bones. His whole body was bloated with the loathsome dropsy of beri-beri. With a shock I realised that it was Sergeant Hayes and it was quite obvious that he was dying. Then the sergeant opened his eyes and as he saw me they lit up bravely and he grinned. Even so near the end, I would not have expected anything but a grin from this RAF Sergeant.

"They can't kill you, can they, sir?" he said in a broken voice. Then, as if the effort had been too much, he closed his eyes. Soon I could see that Sergeant Hayes had dozed off. Out there on the sandbank in the middle of the little river we decided we would all rest for the night. John Griffiths and I lay down one on each side of the sergeant, this brave man who had done so many magnificent deeds all through this expedition.

Almost at the end of the night Sergeant Hayes woke. Both John and I sensed it immediately. He was struggling to do something. I saw that he was pulling his small pack up towards him and I helped him to get it. "Will you take this for me?" he asked, his voice now soft and low. "You will see that my wife gets it, won't you, sir?" I saw that what he was struggling to get out of his pack was a photograph album. John took the book from him and said : "Of course we will, Sergeant, of course we will."

As the sun rose the life of the gallant Sergeant Hayes came to an end. Sadly, I picked up his belt with my pistol attached, still in its holster and buckled it on myself. John Griffiths was flicking through the pages of the battered photograph album. "Photographs—all photographs of his wife," he said with a sob in his voice.

Footnote

Since my first reading of Ian MacHorton's book (probably way back in 2008), the exploits of Sergeant Hayes and his gallant leadership of the small splinter group of Chindits at the Irrawaddy has always stood out as one of the most heroic performances of any soldier during the first Wingate expedition. I have tried on several occasions to find the Sergeant on the Commonwealth Graves website and through other research means at my disposal, but sadly to no avail. I now wonder if MacHorton, writing his book in 1958, felt it still too close to the war to actually name those men who lost their lives on that weary and arduous return journey to India. Perhaps in some kind way, he decided to change the name of the real Sergeant Hayes in order to protect the family involved.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story, including a gravestone in honour of an unknown RAF Sergeant from WW2. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Remarkably and with great fortune, Lt. MacHorton was taken by motor transport in a westward direction by his captors, towards the Chindwin and the Japanese garrison town of Kalewa. Before reaching the town he managed to effect an escape and moved off north keeping the river on his left hand side in the hope of reaching Allied held territory. A few days passed by and MacHorton now suffering from starvation, exhaustion and the agonies of his wounds was close to collapse. He stopped his journey by a small stream and took a long drink from the crystal clear water.

Then, amazingly, he noticed some 50 yards away, a group of ragged scarecrow looking men. It was the remnants of No. 1 Column still led by Major Dunlop. From the book, Safer Than a Known Way:

As I approached the depleted party I met John Griffiths: "Hullo, Ian. You again," he said. John was sitting beside a large man whose prostrate body seemed still well covered with flesh. The man was panting and the sweat stood out on his brow in great beads. One arm was swollen terribly and was supported in a sling. I now saw that his apparent bulk was nothing to do with the flesh on his bones. His whole body was bloated with the loathsome dropsy of beri-beri. With a shock I realised that it was Sergeant Hayes and it was quite obvious that he was dying. Then the sergeant opened his eyes and as he saw me they lit up bravely and he grinned. Even so near the end, I would not have expected anything but a grin from this RAF Sergeant.

"They can't kill you, can they, sir?" he said in a broken voice. Then, as if the effort had been too much, he closed his eyes. Soon I could see that Sergeant Hayes had dozed off. Out there on the sandbank in the middle of the little river we decided we would all rest for the night. John Griffiths and I lay down one on each side of the sergeant, this brave man who had done so many magnificent deeds all through this expedition.

Almost at the end of the night Sergeant Hayes woke. Both John and I sensed it immediately. He was struggling to do something. I saw that he was pulling his small pack up towards him and I helped him to get it. "Will you take this for me?" he asked, his voice now soft and low. "You will see that my wife gets it, won't you, sir?" I saw that what he was struggling to get out of his pack was a photograph album. John took the book from him and said : "Of course we will, Sergeant, of course we will."

As the sun rose the life of the gallant Sergeant Hayes came to an end. Sadly, I picked up his belt with my pistol attached, still in its holster and buckled it on myself. John Griffiths was flicking through the pages of the battered photograph album. "Photographs—all photographs of his wife," he said with a sob in his voice.

Footnote

Since my first reading of Ian MacHorton's book (probably way back in 2008), the exploits of Sergeant Hayes and his gallant leadership of the small splinter group of Chindits at the Irrawaddy has always stood out as one of the most heroic performances of any soldier during the first Wingate expedition. I have tried on several occasions to find the Sergeant on the Commonwealth Graves website and through other research means at my disposal, but sadly to no avail. I now wonder if MacHorton, writing his book in 1958, felt it still too close to the war to actually name those men who lost their lives on that weary and arduous return journey to India. Perhaps in some kind way, he decided to change the name of the real Sergeant Hayes in order to protect the family involved.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story, including a gravestone in honour of an unknown RAF Sergeant from WW2. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, February 2019.