The Diary of Dennis Brown

A Private's Private Diary

Dennis Brown, India 1945.

Dennis Brown, India 1945.

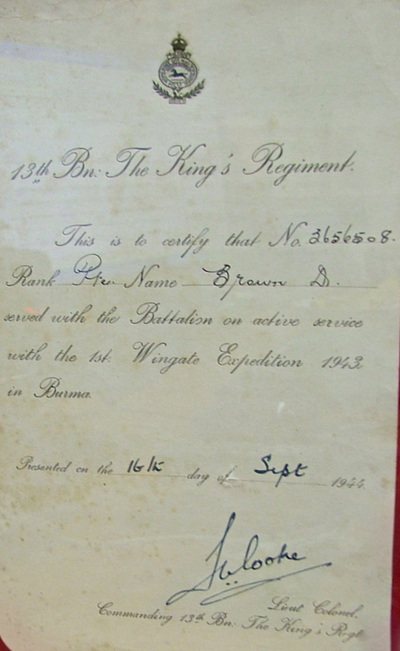

In June 2011, I was extremely fortunate to receive an email contact from Peter Brydon, who amongst other interests, collects insignia relating to the Liverpool Regiment in all their various guises from their time as the 8th (The King's) Regiment of Foot until their amalgamation with the Manchester Regiment post WW2. One item in Peter's possession was the war time diary of Dennis 'Topper' Brown of the King's Regiment and a survivor of Operation Longcloth.

Pte. Dennis Brown began his time in the British Army serving with the Prince of Wales Volunteers (South Lancashire Regiment). He then voyaged to India in early 1942 and after disembarking at Bombay, spent a short time at the famous reinforcement camp at Deolali. According to the battalion's records, Dennis was posted to the 13th King's on 31st July 1942. Here is a quote from the 13th King's War diary for this period:

31st July 1942:

“A draft of 144 men arrived here (Patharia) today. They had come from the 5th, 8th and 9th King's Liverpool battalions, with a few men from the South Lancashire’s. On the whole they seem like a very good lot."

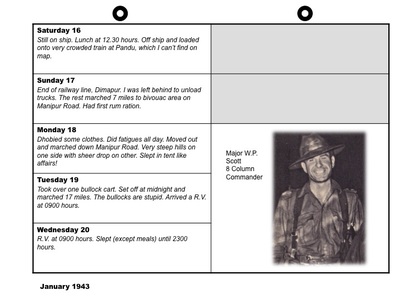

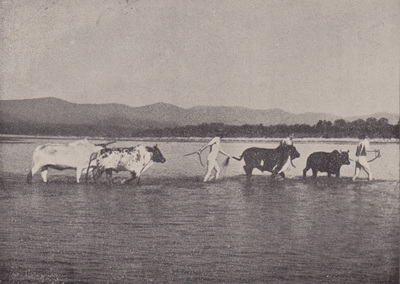

Dennis entered into Chindit training at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India; here he joined the ranks of No. 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott. As you will read from the extracts in his diary, Dennis was given the responsibility for looking after part of the bullock transport for the column, although he was actually a member of No. 17 Rifle Platoon in the first instance. These cumbersome animals were used in the early weeks of the expedition to transport the heavier items of equipment required for the operation, and usually pulled large carts along the trails and pathways leading up to the border with Burma and the ultimately the Chindwin River.

Generally speaking, the bullock transport sections brought up the rear of each Chindit column during their journey to the Chindwin. Often, these animals and the unfortunate men who drove them, would not reach the designated rendezvous location for their unit until several hours after the leading elements of the column had already settled down for the night. Eventually, many of these animals were consumed by the Chindits, as a supplement to their meagre and monotonous hard scale rations and the rice acquired from local villages en route.

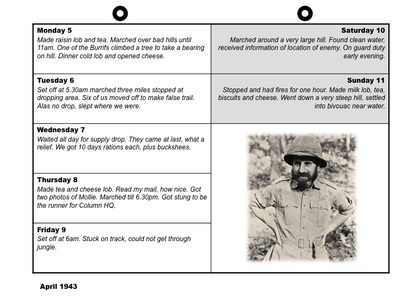

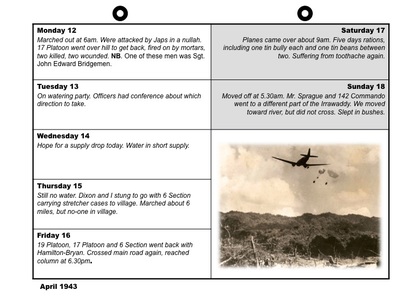

Pte. Brown worked in close conjunction with Northern Group Head Quarters in the first few weeks of Operation Longcloth, and this often placed him close to Brigadier Wingate. In his diary, he remarks with some humour that whilst led by Wingate, the Chindit columns tended to almost run along the tracks of Burma instead of marching at a more normal pace. The original diary was handwritten in pencil and was then transcribed into print after the war. For the purposes of this story, I have typed out the majority of the entries back into diary form and will present them in the galleries below in chronological order. I have also attempted to illustrate the narrative by adding the odd image, photograph or map to the diary pages.

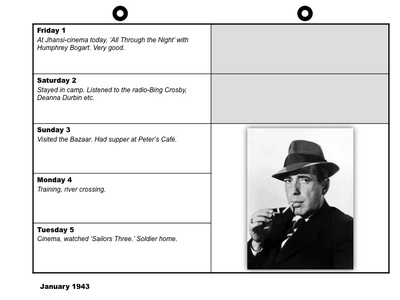

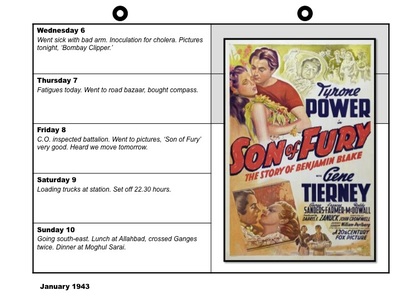

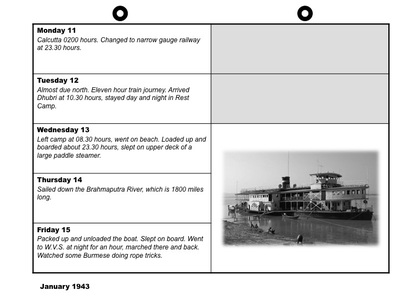

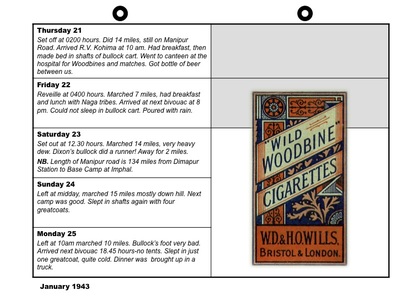

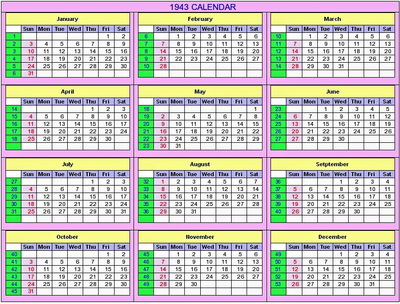

We begin with the entries for January 1943 and the Brigade's preparations for the expedition and journey to their starting point at Imphal in Assam. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Pte. Dennis Brown began his time in the British Army serving with the Prince of Wales Volunteers (South Lancashire Regiment). He then voyaged to India in early 1942 and after disembarking at Bombay, spent a short time at the famous reinforcement camp at Deolali. According to the battalion's records, Dennis was posted to the 13th King's on 31st July 1942. Here is a quote from the 13th King's War diary for this period:

31st July 1942:

“A draft of 144 men arrived here (Patharia) today. They had come from the 5th, 8th and 9th King's Liverpool battalions, with a few men from the South Lancashire’s. On the whole they seem like a very good lot."

Dennis entered into Chindit training at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India; here he joined the ranks of No. 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott. As you will read from the extracts in his diary, Dennis was given the responsibility for looking after part of the bullock transport for the column, although he was actually a member of No. 17 Rifle Platoon in the first instance. These cumbersome animals were used in the early weeks of the expedition to transport the heavier items of equipment required for the operation, and usually pulled large carts along the trails and pathways leading up to the border with Burma and the ultimately the Chindwin River.

Generally speaking, the bullock transport sections brought up the rear of each Chindit column during their journey to the Chindwin. Often, these animals and the unfortunate men who drove them, would not reach the designated rendezvous location for their unit until several hours after the leading elements of the column had already settled down for the night. Eventually, many of these animals were consumed by the Chindits, as a supplement to their meagre and monotonous hard scale rations and the rice acquired from local villages en route.

Pte. Brown worked in close conjunction with Northern Group Head Quarters in the first few weeks of Operation Longcloth, and this often placed him close to Brigadier Wingate. In his diary, he remarks with some humour that whilst led by Wingate, the Chindit columns tended to almost run along the tracks of Burma instead of marching at a more normal pace. The original diary was handwritten in pencil and was then transcribed into print after the war. For the purposes of this story, I have typed out the majority of the entries back into diary form and will present them in the galleries below in chronological order. I have also attempted to illustrate the narrative by adding the odd image, photograph or map to the diary pages.

We begin with the entries for January 1943 and the Brigade's preparations for the expedition and journey to their starting point at Imphal in Assam. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

For the majority of their journey in January and February 1943, the Chindit Brigade (77 Indian Infantry Brigade) travelled along the Manipur Road in Assam. This was the main artery used by Allied Forces in reaching the border with Burma during 1943 and was an especially busy highway; always full of troops, motor transport and often teams of construction workers rebuilding and widening the road. The Chindits marched at night when using the road, this was to keep the highway clear for important motorised traffic during the day, but also in an attempt to ensure their own movements were as secretive as possible.

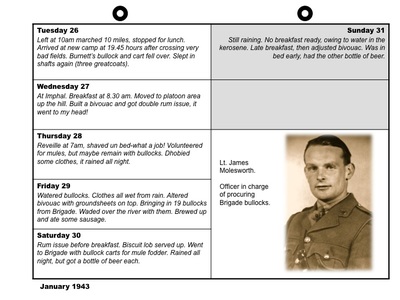

Dennis was not overly enamoured with his task of driving the column bullocks along the Manipur Road and complained often about the awkward nature of these beasts, which were only sometimes under his control. He also remarked on many occasions, just how cold the nights were in the hills of Assam, where British soldiers still found use for their winter issue greatcoats. As mentioned in the diary entries, Dennis Brown did attempt to opt out of his bullock related responsibilities, volunteering at one point to switch to Mule Transport instead. In the end his role with the beasts of burden did not last overly long, as once over the Chindwin River, the animals were slaughtered and used as meat rations for the already hungry British troops.

There are many references to the term 'lob' in the diary. This simply describes the British Chindits creative culinary skill in mixing up the monotony of the hard scale rations, dropped into the columns during air supply. Many of the men used to combine the various elements of the mainly dry and tasteless foodstuffs, to create more palatable cuisine. And so the chocolate, raisin and even cheese lob was conceived. Pte. Leonard Grist, another soldier from the first Wingate expedition, also remembered creating these strange edible concoctions in 1943:

"Right lads, brew up, then douse those fires and we'll get out of here!" the Sergeant informed us at the end of a halt. Hastily we produced from our packs the powdered milk, teabags, slabs of chocolate and shackapura biscuits for our meal. Lighting small fires we cooked what was affectionately called chocolate lob, mixing the chocolate and biscuits together with water, it made quite a good dish.

Pte. Brown's diary sometimes mentions other soldiers who were his personal friends on Operation Longcloth, or colleagues from within 8 Column. They are referred to either by their full name and rank, or simply by their Christian name or nickname. It has been my great fortune to have received many family contacts over the past six years, the period during which my website has been on line. Included amongst these contacts have been relatives of some of men mentioned by Dennis Brown in his narrative, this has enabled me to illustrate his story, not just with notes and extra information, but with photographs of his contemporaries too.

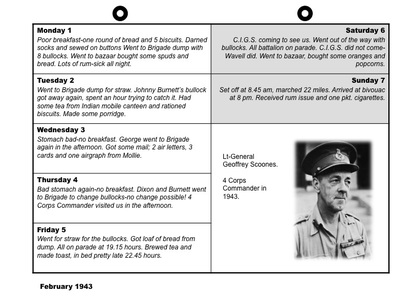

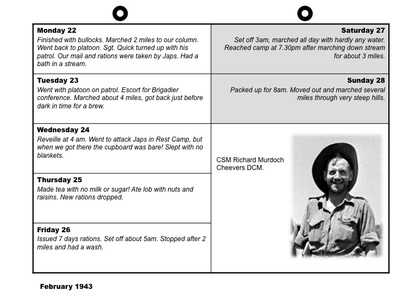

Seen below are the diary pages for the month of February. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Dennis was not overly enamoured with his task of driving the column bullocks along the Manipur Road and complained often about the awkward nature of these beasts, which were only sometimes under his control. He also remarked on many occasions, just how cold the nights were in the hills of Assam, where British soldiers still found use for their winter issue greatcoats. As mentioned in the diary entries, Dennis Brown did attempt to opt out of his bullock related responsibilities, volunteering at one point to switch to Mule Transport instead. In the end his role with the beasts of burden did not last overly long, as once over the Chindwin River, the animals were slaughtered and used as meat rations for the already hungry British troops.

There are many references to the term 'lob' in the diary. This simply describes the British Chindits creative culinary skill in mixing up the monotony of the hard scale rations, dropped into the columns during air supply. Many of the men used to combine the various elements of the mainly dry and tasteless foodstuffs, to create more palatable cuisine. And so the chocolate, raisin and even cheese lob was conceived. Pte. Leonard Grist, another soldier from the first Wingate expedition, also remembered creating these strange edible concoctions in 1943:

"Right lads, brew up, then douse those fires and we'll get out of here!" the Sergeant informed us at the end of a halt. Hastily we produced from our packs the powdered milk, teabags, slabs of chocolate and shackapura biscuits for our meal. Lighting small fires we cooked what was affectionately called chocolate lob, mixing the chocolate and biscuits together with water, it made quite a good dish.

Pte. Brown's diary sometimes mentions other soldiers who were his personal friends on Operation Longcloth, or colleagues from within 8 Column. They are referred to either by their full name and rank, or simply by their Christian name or nickname. It has been my great fortune to have received many family contacts over the past six years, the period during which my website has been on line. Included amongst these contacts have been relatives of some of men mentioned by Dennis Brown in his narrative, this has enabled me to illustrate his story, not just with notes and extra information, but with photographs of his contemporaries too.

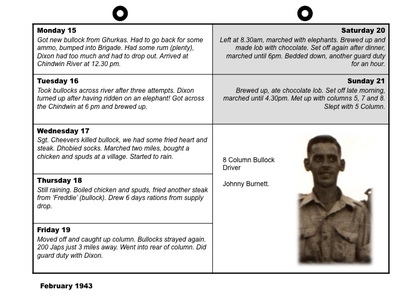

Seen below are the diary pages for the month of February. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Sgt. John Edward Bridgeman, a former stonemason from Old Trafford in Manchester, is mentioned in the diary as being the NCO in charge of the Bullock Transport Section as it prepared to cross the official border between India and Burma, close to the town of Tamu. John was sadly killed in action on the 12th April 1943, after his platoon were ambushed by a Japanese patrol just south of the Irrawaddy River. To read more about this soldier, please click on the following link: Sergeant John Edward Bridgeman

It is clear from reading Dennis' diary, how important the Army rum ration was to the men on Operation Longcloth. Apart from the medicinal properties of the rum, it must have provided much needed solace on the long and arduous marches through the Burmese jungles. The apparent scarcity of both sugar and salt in the men's diet also proved significant, when later in the expedition health issues became a major concern for the column Medical Officers.

Dennis also recalls the visit by General Wavell and his inspection of the Chindit Brigade at Imphal. It was at this moment that Wavell and Wingate debated whether Operation Longcloth should even go ahead, after the other components of the original plan; a Chinese Army push against the Japanese from the east and assistance from Vinegar Joe Stilwell in the north of Burma had been withdrawn. In the end Wingate won out and the first Chindit operation prevailed. Another soldier with 8 Column in 1943 was Pte. Eric Allen, he too remembered Wavell's visit at Imphal:

We knew our epitaph had been written by Delhi before we started. Even Lord Wavell had saluted us at Imphal: the traditional eyes right or left salute of the British Army had been dispensed with and Wavell stood smartly to attention, his hand raised in salute until every man and animal had gone by. This was extremely unusual and a message in his eyes seemed to say “Goodbye, God bless you, but please don’t blame me."

The majority of Northern Group crossed the Chindwin River on the 15/16th February at a place called Tonhe. Several of the Chindit columns bumped up against each other at this time and traffic at the river became very congested. To alleviate the pressure at Tonhe, 5 Column decided to move slightly north and cross at Hwematte.

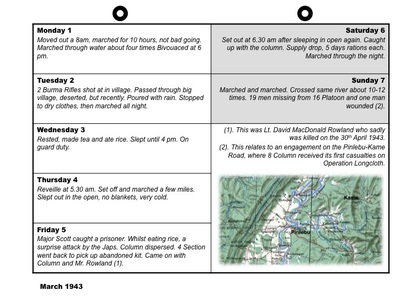

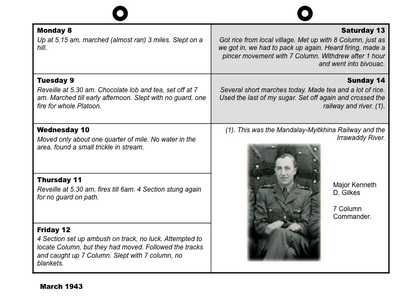

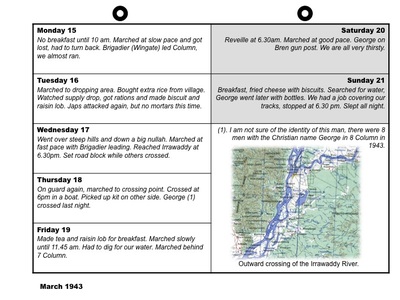

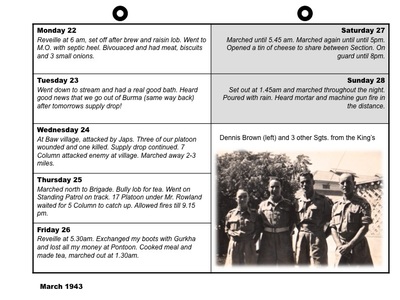

Here are the diary pages for March 1943 and the Brigade's first few weeks behind enemy lines. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

It is clear from reading Dennis' diary, how important the Army rum ration was to the men on Operation Longcloth. Apart from the medicinal properties of the rum, it must have provided much needed solace on the long and arduous marches through the Burmese jungles. The apparent scarcity of both sugar and salt in the men's diet also proved significant, when later in the expedition health issues became a major concern for the column Medical Officers.

Dennis also recalls the visit by General Wavell and his inspection of the Chindit Brigade at Imphal. It was at this moment that Wavell and Wingate debated whether Operation Longcloth should even go ahead, after the other components of the original plan; a Chinese Army push against the Japanese from the east and assistance from Vinegar Joe Stilwell in the north of Burma had been withdrawn. In the end Wingate won out and the first Chindit operation prevailed. Another soldier with 8 Column in 1943 was Pte. Eric Allen, he too remembered Wavell's visit at Imphal:

We knew our epitaph had been written by Delhi before we started. Even Lord Wavell had saluted us at Imphal: the traditional eyes right or left salute of the British Army had been dispensed with and Wavell stood smartly to attention, his hand raised in salute until every man and animal had gone by. This was extremely unusual and a message in his eyes seemed to say “Goodbye, God bless you, but please don’t blame me."

The majority of Northern Group crossed the Chindwin River on the 15/16th February at a place called Tonhe. Several of the Chindit columns bumped up against each other at this time and traffic at the river became very congested. To alleviate the pressure at Tonhe, 5 Column decided to move slightly north and cross at Hwematte.

Here are the diary pages for March 1943 and the Brigade's first few weeks behind enemy lines. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

At the beginning of the pages for the month of March, Dennis mentions a surprise engagement with the Japanese. This was the battle fought on the Pinlebu-Kame Road. Here is an extract taken from the Column 8 War Diary for that period of time:

“4th and 5th March: column moved into the area around Pinlebu, there were said to be 600-1000 enemy troops in this locality. The Burma Rifle Officers had spoken to a native of the area, he turned out to be a Japanese spy and was shot. Water parties were sent out to replenish supplies, these units were engaged by enemy patrols but most managed to disengage and return to the main body."

More minor clashes with the Japanese were incurred late on 5th March, the column moved to the agreed rendezvous on the Pinlebu-Kame Road (see map in above gallery). The party halted one mile north of Kame and settled down for the night. Their position was chosen by Major Scott and units were deployed to prevent any Japanese movement toward Pinlebu from this direction.

“At first light on the 6th March, the Sabotage Squad led by Lieutenant Sprague and 16 Platoon set out toward Kame to secure the road block. At about 1100 hours Sprague’s men were attacked by the Japanese from all sides, he called dispersal in an attempt to extract his men, it was here that Lieutenant Callaghan was shot and killed."

Dennis also mentions an officer named Rowland around this time. This is reference to Lt. David MacDonald Rowland formerly of the Royal Sussex Regiment. David was the son of Frank and Flora Rowland from Horsham in Sussex. David was posted to Chindit Column 8 and served with this unit throughout Operation Longcloth. The young Lieutenant always seemed to be at the forefront of Column activities, volunteering for difficult and often dangerous duties. In early March 1943, he became the go-between officer for Column 8, taking messages and fresh orders to other Chindit columns in the area around Pinlebu.

After the fiercely contested supply drop at the village of Baw on the 24th March, David Rowland was asked by Major Scott to remain in the locality and await the arrival of Column 5. The drop zone had been compromised by a Japanese patrol and a long and drawn out action had been fought on the east side of the village. Column 5 were several miles away at that time and would have lost their chance of much needed food rations and supplies, were it not for the bravery of Lieutenant Rowland and his platoon.

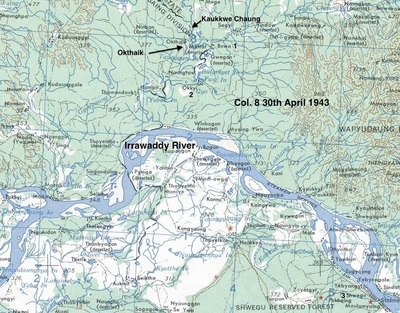

By the end of April 1943, Column 8 had moved across the Irrawaddy River and were heading roughly northwest towards the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. They reached the village of Okthaik on the 30th April and avoiding local trails, began to cross the narrow, but fast flowing Kaukkwe Chaung. Major Scott sent a section across to form the usual protective bridgehead, then began to ferry over the non-swimmers and equipment.

Suddenly from amongst the teak trees, a Japanese patrol opened fire upon the Chindits on the nearside bank. Many of the officers and NCO's of the column had remained on this bank as rearguard, they returned fire against the Japanese with all that they had. Sadly, David Rowland was shot and killed at this engagement.

The reader might notice mention of the interchanging of personnel between Chindit Columns 7 and 8. Throughout Operation Longcloth, these two columns along with Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters, were never more than a few miles from each other. It was common for platoons from all units to join up with their comrades in other columns, especially when seeking out enemy targets for attack, or defending their own positions. This was definitely the case, as Northern Group prepared to cross the Irrawaddy River for the first time on the 18th March.

It was after crossing the Irrawaddy and moving into the arid belt of land beyond, that finding decent drinking water became an issue for Wingate's Brigade. Often the men were forced to dig down into dry chaungs and take up the slow trickle of foul smelling liquid into their water bottles. Thankfully, there was still a plentiful supply of chlorine tablets to purify the polluted water and the men got by.

On the 22nd March, Dennis mentions that his meal that day included three small onions. Wingate had always championed this vegetable and during Chindit training the men had been encouraged by their leader to consume as many raw onions as possible. Dennis then recalls that on the 23rd March, the Brigade were informed that they would be returning to India after one final supply drop, due to take place near a village called Baw.

The supply drop at Baw was planned for the next day and was be an extremely large affair, re-supplying around 1300 men from Northern Group. Wingate and his column commanders surveyed maps of the area and chose the drop zone, which was a succession of dry paddy fields on the outskirts of the village. Orders were given for two units from 8 Column to secure the main road leading in and out of the village, one of the road blocks was to be manned by 17 Platoon. Unfortunately for the Chindits the supply drop was compromised, when a large group of enemy troops attacked the tracks leading to the village.

Tony Aubrey, a Sergeant with 17 Platoon recalled the moment the Japanese opened fire:

"We took up a defensive position on the crest of a small rise on the edge of the woodland. Visibility was barely 10 yards forwards as the enemy opened fire on us. Our unit soon suffered casualties, Pte. Birch was killed, with no fewer than 17 bullets finding him out. Lambert was shot in the chest, Yates in the hand and shoulder and Suddery received a bullet which went through his right bicep, punctured his ribs and exited through his stomach. In spite of his wounds Suddery continued to fire his Bren from the hip as we attempted to retreat into the woods."

Regardless of this enemy interference, the Chindits continued on with the supply drop at Baw. When they had succeeded in re-stocking, they disengaged from the Japanese and marched away to the north-west, heading once again towards the Irrawaddy River.

Dennis Brown's diary continues:

“4th and 5th March: column moved into the area around Pinlebu, there were said to be 600-1000 enemy troops in this locality. The Burma Rifle Officers had spoken to a native of the area, he turned out to be a Japanese spy and was shot. Water parties were sent out to replenish supplies, these units were engaged by enemy patrols but most managed to disengage and return to the main body."

More minor clashes with the Japanese were incurred late on 5th March, the column moved to the agreed rendezvous on the Pinlebu-Kame Road (see map in above gallery). The party halted one mile north of Kame and settled down for the night. Their position was chosen by Major Scott and units were deployed to prevent any Japanese movement toward Pinlebu from this direction.

“At first light on the 6th March, the Sabotage Squad led by Lieutenant Sprague and 16 Platoon set out toward Kame to secure the road block. At about 1100 hours Sprague’s men were attacked by the Japanese from all sides, he called dispersal in an attempt to extract his men, it was here that Lieutenant Callaghan was shot and killed."

Dennis also mentions an officer named Rowland around this time. This is reference to Lt. David MacDonald Rowland formerly of the Royal Sussex Regiment. David was the son of Frank and Flora Rowland from Horsham in Sussex. David was posted to Chindit Column 8 and served with this unit throughout Operation Longcloth. The young Lieutenant always seemed to be at the forefront of Column activities, volunteering for difficult and often dangerous duties. In early March 1943, he became the go-between officer for Column 8, taking messages and fresh orders to other Chindit columns in the area around Pinlebu.

After the fiercely contested supply drop at the village of Baw on the 24th March, David Rowland was asked by Major Scott to remain in the locality and await the arrival of Column 5. The drop zone had been compromised by a Japanese patrol and a long and drawn out action had been fought on the east side of the village. Column 5 were several miles away at that time and would have lost their chance of much needed food rations and supplies, were it not for the bravery of Lieutenant Rowland and his platoon.

By the end of April 1943, Column 8 had moved across the Irrawaddy River and were heading roughly northwest towards the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. They reached the village of Okthaik on the 30th April and avoiding local trails, began to cross the narrow, but fast flowing Kaukkwe Chaung. Major Scott sent a section across to form the usual protective bridgehead, then began to ferry over the non-swimmers and equipment.

Suddenly from amongst the teak trees, a Japanese patrol opened fire upon the Chindits on the nearside bank. Many of the officers and NCO's of the column had remained on this bank as rearguard, they returned fire against the Japanese with all that they had. Sadly, David Rowland was shot and killed at this engagement.

The reader might notice mention of the interchanging of personnel between Chindit Columns 7 and 8. Throughout Operation Longcloth, these two columns along with Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters, were never more than a few miles from each other. It was common for platoons from all units to join up with their comrades in other columns, especially when seeking out enemy targets for attack, or defending their own positions. This was definitely the case, as Northern Group prepared to cross the Irrawaddy River for the first time on the 18th March.

It was after crossing the Irrawaddy and moving into the arid belt of land beyond, that finding decent drinking water became an issue for Wingate's Brigade. Often the men were forced to dig down into dry chaungs and take up the slow trickle of foul smelling liquid into their water bottles. Thankfully, there was still a plentiful supply of chlorine tablets to purify the polluted water and the men got by.

On the 22nd March, Dennis mentions that his meal that day included three small onions. Wingate had always championed this vegetable and during Chindit training the men had been encouraged by their leader to consume as many raw onions as possible. Dennis then recalls that on the 23rd March, the Brigade were informed that they would be returning to India after one final supply drop, due to take place near a village called Baw.

The supply drop at Baw was planned for the next day and was be an extremely large affair, re-supplying around 1300 men from Northern Group. Wingate and his column commanders surveyed maps of the area and chose the drop zone, which was a succession of dry paddy fields on the outskirts of the village. Orders were given for two units from 8 Column to secure the main road leading in and out of the village, one of the road blocks was to be manned by 17 Platoon. Unfortunately for the Chindits the supply drop was compromised, when a large group of enemy troops attacked the tracks leading to the village.

Tony Aubrey, a Sergeant with 17 Platoon recalled the moment the Japanese opened fire:

"We took up a defensive position on the crest of a small rise on the edge of the woodland. Visibility was barely 10 yards forwards as the enemy opened fire on us. Our unit soon suffered casualties, Pte. Birch was killed, with no fewer than 17 bullets finding him out. Lambert was shot in the chest, Yates in the hand and shoulder and Suddery received a bullet which went through his right bicep, punctured his ribs and exited through his stomach. In spite of his wounds Suddery continued to fire his Bren from the hip as we attempted to retreat into the woods."

Regardless of this enemy interference, the Chindits continued on with the supply drop at Baw. When they had succeeded in re-stocking, they disengaged from the Japanese and marched away to the north-west, heading once again towards the Irrawaddy River.

Dennis Brown's diary continues:

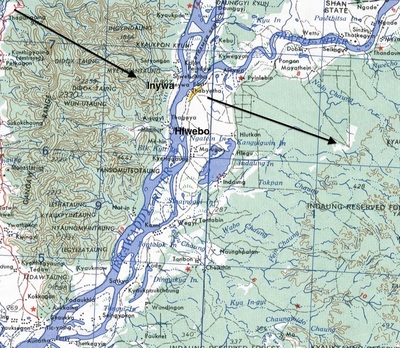

On the 29th March, Columns 7 and 8 along with Wingate's HQ had massed on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River near the town of Inywa. The idea was to get across this wide expanse of water as quickly as possible and then, once over, move off westwards and return to India. Wingate had previously crossed the Irrawaddy close to Inywa on the outward journey and thought the Japanese would not expect him to retrace his steps.

Unfortunately, the crossing was contested by a large patrol of Japanese soldiers positioned on the opposite bank of the river. The men in the leading boats soon came under severe machine gun and mortar fire, resulting in many casualties. Wingate, after a speedy consultation with his column commanders, decided to call off the crossing and the dispirited Chindits melted away into the jungle. Columns 7 and 8 soon moved away from the Irrawaddy, both heading roughly south-east. Wingate took his men deep in to the surrounding scrub-jungle close to Inywa, where they would wait patiently for several days until the heat had died down and the enemy had left the area.

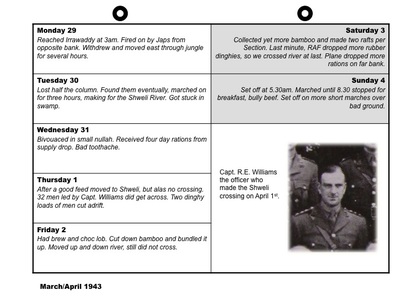

Major Scott and 8 Column decided to attempt a crossing of the less formidable Shweli River and then proceed once again towards the more expansive Irrawaddy. Disaster struck the column on the 1st April during their first attempt at the Shweli. To read more about the exploits of Captain Raymond Williams and the men lost in the boats swept downstream on the 1st April, please click on the following links:

Captain Williams and Platoon 18

Eric Allen and the Lost Boat on the Shweli

Dennis mentions during this period, that he and his comrades were continually ordered to collect together bamboo canes. There is no doubt that this was in preparation for raft building in an attempt to gain a crossing of the fast flowing Shweli River. In the end, this was not necessary after the RAF delivered several rubber dinghies during a subsequent supply drop. He also mentions that the men received their much-loved 'bully' beef during this supply drop and what a welcome supplement to their rations this turned out to be. In his entry for the 5th April, Dennis uses the acronym 'Burrif'; this simply refers to a member of the Burma Rifles contingent of 8 Column and was the nickname given to these soldiers on Operation Longcloth.

Once over the Shweli River, 8 Column then headed north towards the Irrawaddy, aiming for where the river meandered in a westerly direction close to the town of Bhamo. On the 12th April, Dennis records the column's skirmish with the Japanese just south of this position and remarks upon the sad death of two men, one of which was Sgt. John Bridgeman who is mentioned earlier in this story. The other man killed was Pte. Albert John Beard. Dennis also recounts his involvement in assisting Lt. Hamilton-Bryan and the column Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote, in their attempt to find a friendly village in which to leave the sick and wounded from the column. Dennis then returns to the main body of 8 Column on the 16th April.

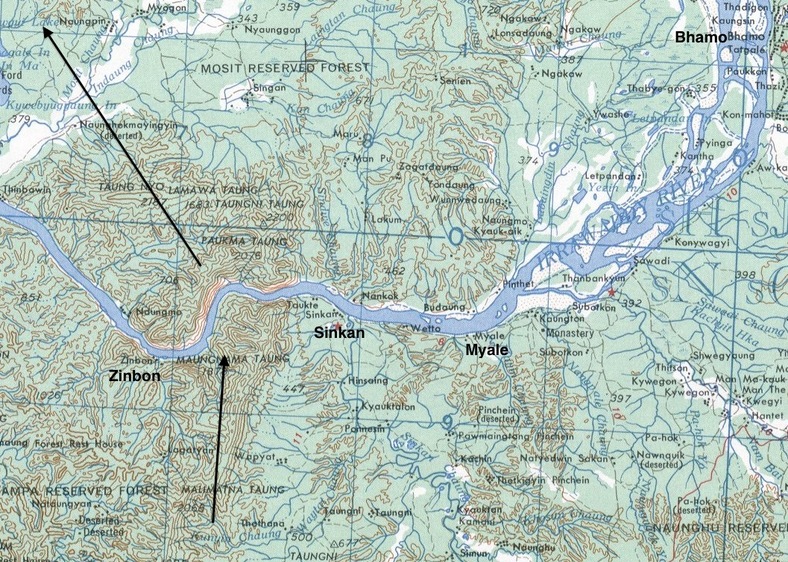

Over the next few days the Chindits examined many possible crossing points along the southern banks of the Irrawaddy, but were always foiled in some way or another in acquiring the means to traverse the mile wide watery obstacle. The Japanese, now completely aware of the Chindits intentions had removed all boats from the banks of the river and now patrolled the waters in motor launches between the villages of Zinbon and Myale. Tony Aubrey, in his book 'With Wingate in Burma', summed up those desperate days:

"We saw and heard nothing of the enemy. But, always on our left, lurking like some inescapable monster, lay the implacable Irrawaddy. It had begun to be almost an obsession with us now, this river. There it lay, flowing calmly and serenely southwards. But, however much water flowed down, there was always enough left to act as a seemingly impassible barrier between ourselves and home. It had assumed a personality. I was surprised that I didn't dream about it at night."

Then suddenly, on the 20th April, Major Scott noticed a Burmese junk making its way down river close to where the Chindits were lying up. He seized his chance and with the assistance of Lieutenant George Borrow and Havildar Lanval of the Burma Rifles, hijacked the boat. Paying the junks owner handsomely in silver rupees, the column were over the river in just less than ninety minutes. Hurriedly, the Chindits melted away into the scrub jungle on the far bank and headed north-west.

Unfortunately, the crossing was contested by a large patrol of Japanese soldiers positioned on the opposite bank of the river. The men in the leading boats soon came under severe machine gun and mortar fire, resulting in many casualties. Wingate, after a speedy consultation with his column commanders, decided to call off the crossing and the dispirited Chindits melted away into the jungle. Columns 7 and 8 soon moved away from the Irrawaddy, both heading roughly south-east. Wingate took his men deep in to the surrounding scrub-jungle close to Inywa, where they would wait patiently for several days until the heat had died down and the enemy had left the area.

Major Scott and 8 Column decided to attempt a crossing of the less formidable Shweli River and then proceed once again towards the more expansive Irrawaddy. Disaster struck the column on the 1st April during their first attempt at the Shweli. To read more about the exploits of Captain Raymond Williams and the men lost in the boats swept downstream on the 1st April, please click on the following links:

Captain Williams and Platoon 18

Eric Allen and the Lost Boat on the Shweli

Dennis mentions during this period, that he and his comrades were continually ordered to collect together bamboo canes. There is no doubt that this was in preparation for raft building in an attempt to gain a crossing of the fast flowing Shweli River. In the end, this was not necessary after the RAF delivered several rubber dinghies during a subsequent supply drop. He also mentions that the men received their much-loved 'bully' beef during this supply drop and what a welcome supplement to their rations this turned out to be. In his entry for the 5th April, Dennis uses the acronym 'Burrif'; this simply refers to a member of the Burma Rifles contingent of 8 Column and was the nickname given to these soldiers on Operation Longcloth.

Once over the Shweli River, 8 Column then headed north towards the Irrawaddy, aiming for where the river meandered in a westerly direction close to the town of Bhamo. On the 12th April, Dennis records the column's skirmish with the Japanese just south of this position and remarks upon the sad death of two men, one of which was Sgt. John Bridgeman who is mentioned earlier in this story. The other man killed was Pte. Albert John Beard. Dennis also recounts his involvement in assisting Lt. Hamilton-Bryan and the column Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote, in their attempt to find a friendly village in which to leave the sick and wounded from the column. Dennis then returns to the main body of 8 Column on the 16th April.

Over the next few days the Chindits examined many possible crossing points along the southern banks of the Irrawaddy, but were always foiled in some way or another in acquiring the means to traverse the mile wide watery obstacle. The Japanese, now completely aware of the Chindits intentions had removed all boats from the banks of the river and now patrolled the waters in motor launches between the villages of Zinbon and Myale. Tony Aubrey, in his book 'With Wingate in Burma', summed up those desperate days:

"We saw and heard nothing of the enemy. But, always on our left, lurking like some inescapable monster, lay the implacable Irrawaddy. It had begun to be almost an obsession with us now, this river. There it lay, flowing calmly and serenely southwards. But, however much water flowed down, there was always enough left to act as a seemingly impassible barrier between ourselves and home. It had assumed a personality. I was surprised that I didn't dream about it at night."

Then suddenly, on the 20th April, Major Scott noticed a Burmese junk making its way down river close to where the Chindits were lying up. He seized his chance and with the assistance of Lieutenant George Borrow and Havildar Lanval of the Burma Rifles, hijacked the boat. Paying the junks owner handsomely in silver rupees, the column were over the river in just less than ninety minutes. Hurriedly, the Chindits melted away into the scrub jungle on the far bank and headed north-west.

NB. This was Dennis' miracle, although he seems to recall a much speedier crossing in his own diary, than that recorded by Column Commander, Major Scott. He also recalls that one of his great mates from his Chindit days, Pte. 3650365 James Upton (photographed left) was also involved in the hijacking of the Burmese boat on the Irrawaddy. In his other writings, Dennis describes Jim Upton:

He (Upton) was one of the finest soldiers you could ever wish to meet and I consider it a privilege to have known him and to have served with him. He was a Regular soldier, having joined the South Lancashire Regiment in 1928. He served on the North West Frontier of India, was rescued from the beaches of Dunkirk and then later on served with us in Burma. As you can see, he did his bit for his country. If you ever wanted a reliable man for a special job, Jim was your man.

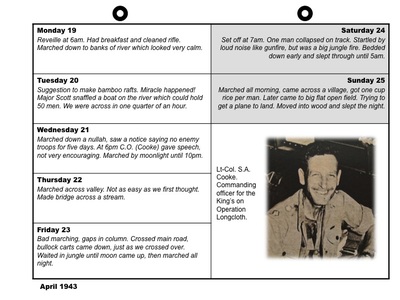

Jim Upton lived in Newport, South Wales after the war and was a keen member of both the Burma Star and Chindit Old Comrades Associations. Sadly, he passed away in 2006. Seen below is a map of the Irrawaddy around the area of Zinbon, the crossing point for 8 Column and Northern Group HQ on the 20th April 1943. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

He (Upton) was one of the finest soldiers you could ever wish to meet and I consider it a privilege to have known him and to have served with him. He was a Regular soldier, having joined the South Lancashire Regiment in 1928. He served on the North West Frontier of India, was rescued from the beaches of Dunkirk and then later on served with us in Burma. As you can see, he did his bit for his country. If you ever wanted a reliable man for a special job, Jim was your man.

Jim Upton lived in Newport, South Wales after the war and was a keen member of both the Burma Star and Chindit Old Comrades Associations. Sadly, he passed away in 2006. Seen below is a map of the Irrawaddy around the area of Zinbon, the crossing point for 8 Column and Northern Group HQ on the 20th April 1943. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Around this time, Dennis mentions a speech given by Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke, the senior officer from the King's Regiment on Operation Longcloth. Pte. Brown recalled:

The speech was not very encouraging for us. The gist of it was that he had orders from General HQ to make the return journey to India, but that if he had his way, we would fight on to the last man and the last bullet. You can imagine how that went down with the rank and file. I did hear that at one time he suggested that the RAF should drop soap, towels and razors, so we could all shave; until it was pointed out that you can't eat these items.

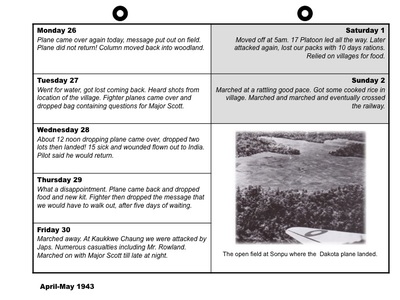

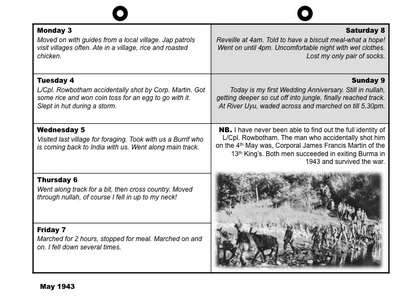

It is very clear from the diary, that by around the fourth week in April the men of 8 Column were totally exhausted and beginning to suffer from disease as well as malnutrition. The soldier mentioned as having collapsed by the trackside on the 23rd April, was almost certainly Pte. Edward Worsley of the 13th King's. The large open field referred to by Dennis Brown in his diary on the 25th April would lead to the unexpected salvation of eighteen men from 8 Column.

The diary concludes:

The speech was not very encouraging for us. The gist of it was that he had orders from General HQ to make the return journey to India, but that if he had his way, we would fight on to the last man and the last bullet. You can imagine how that went down with the rank and file. I did hear that at one time he suggested that the RAF should drop soap, towels and razors, so we could all shave; until it was pointed out that you can't eat these items.

It is very clear from the diary, that by around the fourth week in April the men of 8 Column were totally exhausted and beginning to suffer from disease as well as malnutrition. The soldier mentioned as having collapsed by the trackside on the 23rd April, was almost certainly Pte. Edward Worsley of the 13th King's. The large open field referred to by Dennis Brown in his diary on the 25th April would lead to the unexpected salvation of eighteen men from 8 Column.

The diary concludes:

To read more about the Dakota landing at the jungle clearing near the village of Sonpu, please click on the following link: The Piccadilly Incident

The death of Lieutenant Rowland at the Kaukkwe Chaung is recorded in the book, Wingate's Lost Brigade by author Phil Chinnery:

The next day, 30th April, was a fateful day for 8 Column. They reached the Kaukkwe Chaung, halting a mile south-east of the village of Okthaik. The men began crossing on two rafts that had been constructed out of lifebelts. The Burma Riflemen were across first and Havildar Lanval went into Okthaik and arranged for the Headman to guide them on to Pumhpyu. The bridgehead expanded as more men crossed the river and a heavy thunderstorm began as the column started to form up.

Unknown to the drenched Chindits, a strong enemy force had crept up under cover of the storm and heavy firing suddenly broke out around them. CQMS Duncan Bett was one of the men who retired to the cover of the river bank:

"On reaching the river bank, which was very high and steep, I sank over my knees in the mud with the weight of my pack, which weighed about seventy pounds. I was forced to slip it off and it rolled down the bank and disappeared in the muddy water with all my newly acquired food and gear. I was left with what I stood up in, a rifle and a bandolier of .303 ammunition."

Company Sergeant Major Cheevers reported to Major Scott that he had knocked out two Japanese machine-gun positions on the west side of the perimeter and the RSM was ordered to lead the dispersal groups off in that direction, keeping to the lower banks of the chaung. While this was taking place the Japanese put in a bayonet charge from the south, but they were driven back by 17 Platoon's Bren gun.

Lieutenant Rowland was hit in the chest and was last seen crawling towards the river bank. As Major Scott collected up the stragglers in the area he came across Colour Sergeant Robert Glasgow who had had his knee shattered. He refused all offers of help and asked Scott and others in the area to shoot him as he knew the Japanese would not bother to take him prisoner if he was unable to walk.

Scott told him to lie low until darkness, but Glasgow told the Column Commander not to bother coming back for him as he intended finishing himself off. He was never seen again. At this point the Burma Rifles were seen in the chaung, trying to swim back to the far bank. Two Japanese then appeared on the top of the bank and began dropping grenades into the water. These two were shot by Sergeant Delaney before he too joined the Major and the rest of the column and they melted away into the jungle.

The firing died away but flared up again fifteen minutes later from the direction of Okthaik village where some of the scattered Chindits had made contact with the Japs again. In the meantime Major Scott and his party put five miles of jungle between themselves and the chaung and then bivouacked for the night. They discovered that out of the fifty-seven men in the party, only seven had kept their packs. The bulk of the supplies dropped to the column a day or two earlier at Sonpu had been lost during the fighting.

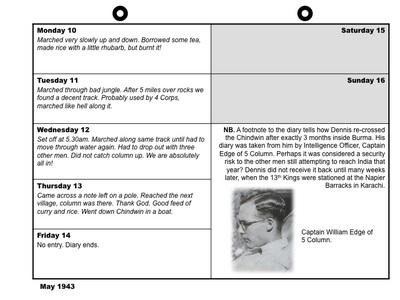

It is quite clear from the latter pages of the diary, that Dennis and many of his comrades were at the end of their tether, suffering from total exhaustion, starvation and of course disease. After reaching the safety of the Chindwin River, the men were taken to Imphal where they were immediately hospitalised at Casualty Clearing Station No. 19. Dennis was troubled by severe dysentery and malnutrition and was confined to his bed for several days. He was then diagnosed as suffering from typhus fever and was transported by stretcher to another hospital at a place called Lampi. After a period of recuperation, he was sent, along with the other survivors from the King's to Napier Barracks in Karachi. This was where the 13th King's were brought back up to strength as a battalion and from where they continued their wartime service. During his time at Karachi, Dennis Brown was promoted to the rank of Sergeant.

When thinking back about his time in Burma Dennis, who was aged 78 at the time recalled:

I suppose in the end the 1943 campaign was a comparatively small affair and us survivors are becoming a bit thin on the ground these days. We had several encounters with the enemy that year, but personally I only ever saw three Japanese soldiers! During the ambushes and other engagements the enemy could be as near as 10-20 yards but could never be seen, although often heard clearly enough. I lost some very good friends in Burma, but I have never forgotten them, not for a single moment.

Seen below is a final gallery in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Peter Brydon for sending me the diary of Pte. Dennis Brown and for sharing many of the photographs and images shown on this page. Dennis Topper Brown sadly passed away on the 19th October 1996, when he was 79 years old.

The death of Lieutenant Rowland at the Kaukkwe Chaung is recorded in the book, Wingate's Lost Brigade by author Phil Chinnery:

The next day, 30th April, was a fateful day for 8 Column. They reached the Kaukkwe Chaung, halting a mile south-east of the village of Okthaik. The men began crossing on two rafts that had been constructed out of lifebelts. The Burma Riflemen were across first and Havildar Lanval went into Okthaik and arranged for the Headman to guide them on to Pumhpyu. The bridgehead expanded as more men crossed the river and a heavy thunderstorm began as the column started to form up.

Unknown to the drenched Chindits, a strong enemy force had crept up under cover of the storm and heavy firing suddenly broke out around them. CQMS Duncan Bett was one of the men who retired to the cover of the river bank:

"On reaching the river bank, which was very high and steep, I sank over my knees in the mud with the weight of my pack, which weighed about seventy pounds. I was forced to slip it off and it rolled down the bank and disappeared in the muddy water with all my newly acquired food and gear. I was left with what I stood up in, a rifle and a bandolier of .303 ammunition."

Company Sergeant Major Cheevers reported to Major Scott that he had knocked out two Japanese machine-gun positions on the west side of the perimeter and the RSM was ordered to lead the dispersal groups off in that direction, keeping to the lower banks of the chaung. While this was taking place the Japanese put in a bayonet charge from the south, but they were driven back by 17 Platoon's Bren gun.

Lieutenant Rowland was hit in the chest and was last seen crawling towards the river bank. As Major Scott collected up the stragglers in the area he came across Colour Sergeant Robert Glasgow who had had his knee shattered. He refused all offers of help and asked Scott and others in the area to shoot him as he knew the Japanese would not bother to take him prisoner if he was unable to walk.

Scott told him to lie low until darkness, but Glasgow told the Column Commander not to bother coming back for him as he intended finishing himself off. He was never seen again. At this point the Burma Rifles were seen in the chaung, trying to swim back to the far bank. Two Japanese then appeared on the top of the bank and began dropping grenades into the water. These two were shot by Sergeant Delaney before he too joined the Major and the rest of the column and they melted away into the jungle.

The firing died away but flared up again fifteen minutes later from the direction of Okthaik village where some of the scattered Chindits had made contact with the Japs again. In the meantime Major Scott and his party put five miles of jungle between themselves and the chaung and then bivouacked for the night. They discovered that out of the fifty-seven men in the party, only seven had kept their packs. The bulk of the supplies dropped to the column a day or two earlier at Sonpu had been lost during the fighting.

It is quite clear from the latter pages of the diary, that Dennis and many of his comrades were at the end of their tether, suffering from total exhaustion, starvation and of course disease. After reaching the safety of the Chindwin River, the men were taken to Imphal where they were immediately hospitalised at Casualty Clearing Station No. 19. Dennis was troubled by severe dysentery and malnutrition and was confined to his bed for several days. He was then diagnosed as suffering from typhus fever and was transported by stretcher to another hospital at a place called Lampi. After a period of recuperation, he was sent, along with the other survivors from the King's to Napier Barracks in Karachi. This was where the 13th King's were brought back up to strength as a battalion and from where they continued their wartime service. During his time at Karachi, Dennis Brown was promoted to the rank of Sergeant.

When thinking back about his time in Burma Dennis, who was aged 78 at the time recalled:

I suppose in the end the 1943 campaign was a comparatively small affair and us survivors are becoming a bit thin on the ground these days. We had several encounters with the enemy that year, but personally I only ever saw three Japanese soldiers! During the ambushes and other engagements the enemy could be as near as 10-20 yards but could never be seen, although often heard clearly enough. I lost some very good friends in Burma, but I have never forgotten them, not for a single moment.

Seen below is a final gallery in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Peter Brydon for sending me the diary of Pte. Dennis Brown and for sharing many of the photographs and images shown on this page. Dennis Topper Brown sadly passed away on the 19th October 1996, when he was 79 years old.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, July 2016.