Tommy Roberts, from POW to Schoolmaster.

In April 1946 Captain Thomas C. Roberts wrote to his former Chindit column commander Bernard Fergusson. In this letter Roberts informed Fergusson of the detail involving the capture and partial demise of his (Roberts') platoon in 1943.

The letter told of how the men, who by this stage were both starving and exhausted had finally accepted their fate and surrendered to the Japanese in late April that year.

In the last paragraph Roberts, although admitting he himself felt a sense of failure for allowing this to happen to his men, was still very proud and unashamed of their efforts and behaviour.

Bernard Fergusson states this in reply:

"Proud and unashamed! I should think so. Roberts is now a schoolmaster in Lancashire; if he is half as good a teacher as he was an officer, then his pupils are very fortunate."

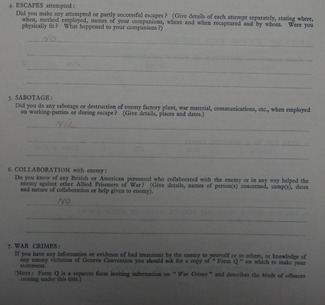

The photograph shown above and to the right, depicts the teaching staff from Ormskirk County Secondary School circa the mid-1960's. Tom is seen in the back row, second from the right. Please click on the image to enlarge.

The letter told of how the men, who by this stage were both starving and exhausted had finally accepted their fate and surrendered to the Japanese in late April that year.

In the last paragraph Roberts, although admitting he himself felt a sense of failure for allowing this to happen to his men, was still very proud and unashamed of their efforts and behaviour.

Bernard Fergusson states this in reply:

"Proud and unashamed! I should think so. Roberts is now a schoolmaster in Lancashire; if he is half as good a teacher as he was an officer, then his pupils are very fortunate."

The photograph shown above and to the right, depicts the teaching staff from Ormskirk County Secondary School circa the mid-1960's. Tom is seen in the back row, second from the right. Please click on the image to enlarge.

Wigan Road School, Ormskirk.

As a footnote to the above book quotation, I was happy to receive this January (2012) a website message from Mr. David Green recounting his memories of Tommy Roberts the teacher. Here is what David had to say:

TC Roberts was my Biology teacher and form master at Wigan Road Secondary Modern school in the late 1950's and early 1960's. I lived in Thompson Avenue at that time and he lived around the corner on Tower Hill. I can honestly say that he was the best teacher I ever met. Many a morning after registration he would tell a short tale about his life as a POW. All I can add is that I am proud to say he was a friend.

I should have mentioned that the old school was in the town of Ormskirk, but it no longer exists today. I remember about a week after I had left school, I was walking home and when I got to his house he was in the garden, I said "good evening Mr. Roberts," he looked up and replied, "you are not at school anymore so call me Tom." I visited him many times after that day and will never forget what a true gentleman he was.

After receiving David's message I decided to explore online for other sources in regard to Captain Roberts and his teaching career. I was fortunate enough to track down two more pupils and their memories of Wigan Road. Firstly, a quote found in a local newspaper from former pupil Phil Daniels, reported as part of the preparation for a 40th Year School Reunion in 2010:

"Obviously we will be discussing our time at Wigan Road and thinking about teachers like the legendary Dickie Thomas. Others like Percy Hender, Charlie Fogg and war hero Tom Roberts were a big influence on all our formative years."

Another reminiscence came from the Internet blog of Steve Hart, I was pleased to receive a contact email from Steve in August 2013:

Hi, you wrote about one of my former teachers, Tom Roberts and his exploits in Malaya, I had the honour to be taught by him from 1965 until 1970, you have also refered to my class mate Phil Daniels. If I can be of any more help please contact me.

Best wishes, Steve Hart.

From Steve's blog:

"Tom Roberts was the chemistry master and had a brand new classroom at the back of the school. If we got bored in his class it was easy to get him talking about the war, where he had been a prisoner in Malaya with the Japanese. He told us of the horrific times they had suffered and said that the film 'The Bridge over the River Kwai' was like a picnic compared to the real thing."

So, I think it is clear that Tommy Roberts had a positive influence on just about everyone he came to lead, whether that be on the battlefield or in the classroom. My heartfelt thanks go to David Green for his memories of his favourite teacher and for taking the trouble to share them with me. Thanks must also go to the two other gentlemen and their stories from Wigan Road School.

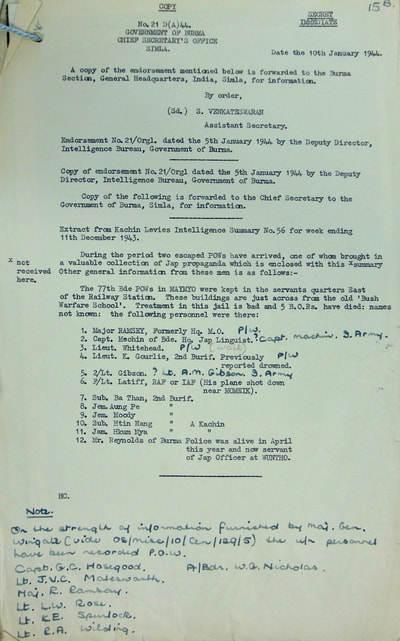

As all the former pupils make mention of his POW stories, I thought this would be a good place to show Tom's prisoner of war pathway, including some of the official documents as illustrations.

After attempting to escape the enemy and slip back across the Burma/India border, Roberts's platoon was finally run to ground at a place called Nanthalung on 29th April 1943. And so began his time as a POW to the Japanese. Chindit soldiers were being captured all over the area around the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. The Japanese collected these men and sent them on to larger holding camps in places such as Bhamo and Wuntho. Eventually, feeling that the majority of the Chindits were now caught, the Japanese set up a larger concentration camp for the soldiers at the hill station of Maymyo.

Tommy Roberts and the remnants of his Support platoon were almost certain to have spent sometime at Bhamo POW camp, before making the long trip up to Maymyo. It was here that the Chindits really began to experience the vile nature of their hosts and several beatings occurred as the men were forced to respond to orders and commands given only in Japanese.

TC Roberts was my Biology teacher and form master at Wigan Road Secondary Modern school in the late 1950's and early 1960's. I lived in Thompson Avenue at that time and he lived around the corner on Tower Hill. I can honestly say that he was the best teacher I ever met. Many a morning after registration he would tell a short tale about his life as a POW. All I can add is that I am proud to say he was a friend.

I should have mentioned that the old school was in the town of Ormskirk, but it no longer exists today. I remember about a week after I had left school, I was walking home and when I got to his house he was in the garden, I said "good evening Mr. Roberts," he looked up and replied, "you are not at school anymore so call me Tom." I visited him many times after that day and will never forget what a true gentleman he was.

After receiving David's message I decided to explore online for other sources in regard to Captain Roberts and his teaching career. I was fortunate enough to track down two more pupils and their memories of Wigan Road. Firstly, a quote found in a local newspaper from former pupil Phil Daniels, reported as part of the preparation for a 40th Year School Reunion in 2010:

"Obviously we will be discussing our time at Wigan Road and thinking about teachers like the legendary Dickie Thomas. Others like Percy Hender, Charlie Fogg and war hero Tom Roberts were a big influence on all our formative years."

Another reminiscence came from the Internet blog of Steve Hart, I was pleased to receive a contact email from Steve in August 2013:

Hi, you wrote about one of my former teachers, Tom Roberts and his exploits in Malaya, I had the honour to be taught by him from 1965 until 1970, you have also refered to my class mate Phil Daniels. If I can be of any more help please contact me.

Best wishes, Steve Hart.

From Steve's blog:

"Tom Roberts was the chemistry master and had a brand new classroom at the back of the school. If we got bored in his class it was easy to get him talking about the war, where he had been a prisoner in Malaya with the Japanese. He told us of the horrific times they had suffered and said that the film 'The Bridge over the River Kwai' was like a picnic compared to the real thing."

So, I think it is clear that Tommy Roberts had a positive influence on just about everyone he came to lead, whether that be on the battlefield or in the classroom. My heartfelt thanks go to David Green for his memories of his favourite teacher and for taking the trouble to share them with me. Thanks must also go to the two other gentlemen and their stories from Wigan Road School.

As all the former pupils make mention of his POW stories, I thought this would be a good place to show Tom's prisoner of war pathway, including some of the official documents as illustrations.

After attempting to escape the enemy and slip back across the Burma/India border, Roberts's platoon was finally run to ground at a place called Nanthalung on 29th April 1943. And so began his time as a POW to the Japanese. Chindit soldiers were being captured all over the area around the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. The Japanese collected these men and sent them on to larger holding camps in places such as Bhamo and Wuntho. Eventually, feeling that the majority of the Chindits were now caught, the Japanese set up a larger concentration camp for the soldiers at the hill station of Maymyo.

Tommy Roberts and the remnants of his Support platoon were almost certain to have spent sometime at Bhamo POW camp, before making the long trip up to Maymyo. It was here that the Chindits really began to experience the vile nature of their hosts and several beatings occurred as the men were forced to respond to orders and commands given only in Japanese.

The Changi POW Camp. Seralang Barracks, Singapore.

Several men died at Maymyo and were buried close to the camp perimeter, very near to the town rail station. Towards the end of May that year the prisoners were being prepared for the long journey south to Rangoon. By the time the last Chindit had left Maymyo on 31st May over 230 men had been collected, recorded and then dispatched to their final destination, Rangoon Central Jail.

For Tommy Roberts and a few of the other Chindit officers captured that year, Rangoon was not to be their final destination. For some reason the Japanese security police (Kempai-Tai) felt the need to remove some of the more important Chindit captives over to their main headquarters in Singapore. It is known that Roberts and the others were interrogated by the Kempai-Tai in a typically thorough manner, before sending them on to the Changi POW Camp. None of the men gave any useful information away to their enquiring hosts.

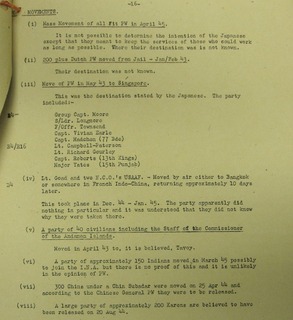

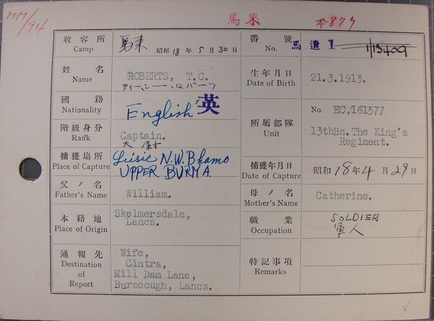

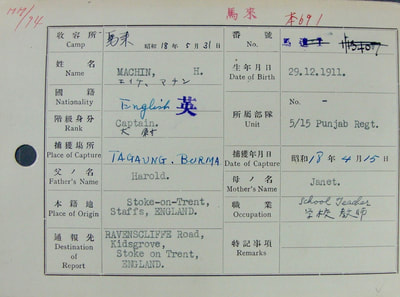

Below are all the official documents that mark Tommy Roberts POW journey starting with the notification for the transfer of the small party of Chindit officers and others from Rangoon to the Kempai-Tai headquarters. Next is the front of Captain Roberts Japanese index card. This shows the details of his Army unit, personal information and date and place of capture. The reverse of the card is scant in detail and is written in Japanese Kanji characters. I have not had this card translated as yet, but looking at the dates written in the script I feel it remarks mainly about the prisoners eventual release. Please click on the image to enlarge.

For Tommy Roberts and a few of the other Chindit officers captured that year, Rangoon was not to be their final destination. For some reason the Japanese security police (Kempai-Tai) felt the need to remove some of the more important Chindit captives over to their main headquarters in Singapore. It is known that Roberts and the others were interrogated by the Kempai-Tai in a typically thorough manner, before sending them on to the Changi POW Camp. None of the men gave any useful information away to their enquiring hosts.

Below are all the official documents that mark Tommy Roberts POW journey starting with the notification for the transfer of the small party of Chindit officers and others from Rangoon to the Kempai-Tai headquarters. Next is the front of Captain Roberts Japanese index card. This shows the details of his Army unit, personal information and date and place of capture. The reverse of the card is scant in detail and is written in Japanese Kanji characters. I have not had this card translated as yet, but looking at the dates written in the script I feel it remarks mainly about the prisoners eventual release. Please click on the image to enlarge.

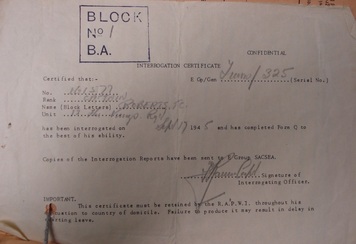

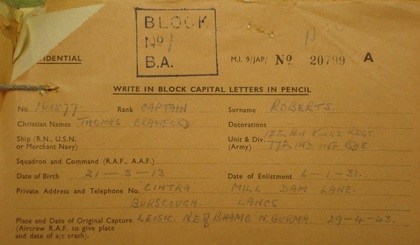

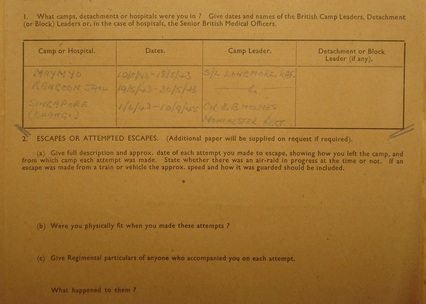

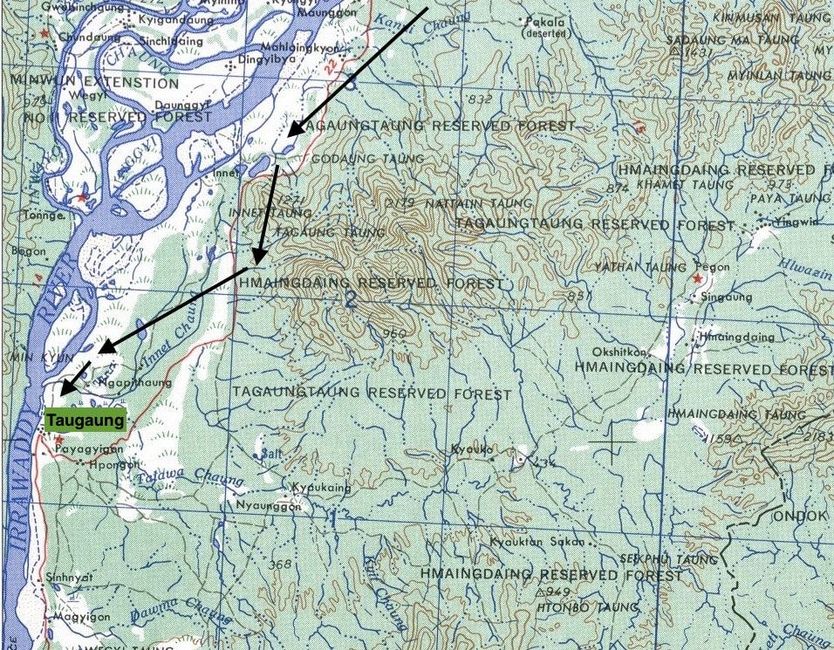

The next image is the Army notice certificate recording that Captain Roberts had partaken and completed a POW 'Liberation Questionnaire' for his time in Changi and was now ready for repatriation. These were debrief documents and collated the information concerning a POW's time in captivity. The first part of the questionnaire simply records his personal details and the place of initial capture. Please click on the images to enlarge.

These documents go on to record a multitude of information from the prisoner, including the camps at which he resided, as shown in the next image (below to the left). Not every surviving POW filled out such a document and hardly any of the Chindits from Rangoon Jail completed these forms. The full document consists of five pages of supplementary questions, asking the prisoner for details about attempted escapes, acts of sabotage against the Japanese war effort and nominations for acts of bravery amongst their peers.

Other information collated on the questionnaire (as shown below, right) includes details on food and medical availability, Japanese brutality and potential war crimes and any incidence of Allied collaboration with the enemy. So, as you might imagine these interviews may well have taken sometime and placed the recently liberated POW under some considerable stress. One surviving Chindit POW who spent the whole of his captivity in Rangoon told me that:

"If some pen pushing Army desk wallah had placed one of these documents under my nose in May 1945, I would have told him to put it where the sun does not shine!"

Other information collated on the questionnaire (as shown below, right) includes details on food and medical availability, Japanese brutality and potential war crimes and any incidence of Allied collaboration with the enemy. So, as you might imagine these interviews may well have taken sometime and placed the recently liberated POW under some considerable stress. One surviving Chindit POW who spent the whole of his captivity in Rangoon told me that:

"If some pen pushing Army desk wallah had placed one of these documents under my nose in May 1945, I would have told him to put it where the sun does not shine!"

That completes the story of Captain Tommy Roberts and his time as a prisoner of war. The paragraphs that follow are a brief description of Changi POW Camp and Changi Jail:

CHANGI POW CAMP was established after Singapore's fall on 15th February 1942, and was the main camp for the captured British forces. Located on Singapore Island near the village of Changi it was the former British Military station of Changi Barracks, built by the British and therefore had the characteristic appearance of a British outpost in the Far East, with barracks and warehouses. This camp became the largest multinational POW camp and a sort of a distribution centre for all the prisoners in southeast Asia. At first there were over 50,000 British and other Commonwealth troops held there, but very quickly work forces of several thousand men were recruited from Changi and sent to various projects in Sumatra, Burma, and Thailand (the Burma-Siam railway) and other Japanese occupied territories. Due to the huge amount of prisoners the Japanese gave responsibility for the administration and daily running of this camp to the prisoners; the guards were mostly Indians from the Indian National Army. The camp was in existence until May 31st 1944, when military prisoners were transferred to Changi prison, while the about 3500 civilians were moved to Sime Road Camp.

CHANGI PRISON was located four kilometers further south (along the coast towards Singapore). This prison was built for the British by American engineers in the 1930's, using Sing-Sing as a model. It had four floors, 440 yards long by 110 yards wide, with walls and the roof made of concrete. In normal times the prison would house 800 prisoners but at one point during the war it had nearer 8000.

If you are interested in learning more about Changi POW Camp, then please follow the link here:

www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/pow/changi

As a follow up to this story I attempted in February (2012) to trace any records or photographs of Tom Roberts from his time as a teacher in Ormskirk. I would like to thank Sarah Baker and Rose Halsall for their input and efforts in trying to track down information for me. Here is their response to my appeal for help;

Hi Steve,

Sorry for the late response but I have been really busy since I got back from my trip to Egypt. I have been speaking to an ex-colleague of Tom's and he is trying to find some old photographs for you. I will be seeing him tomorrow evening so I'll check with him again. I do know that Tom was very highly thought of at Cross Hall School, Wigan Road. That school has now gone and a new school has replaced it, so it is unlikely there will be anything available there. You might like to contact the Lancashire Archive, as they may have something from when Crosshall School ceased to exist in 2001.

Regards, Rose.

CHANGI POW CAMP was established after Singapore's fall on 15th February 1942, and was the main camp for the captured British forces. Located on Singapore Island near the village of Changi it was the former British Military station of Changi Barracks, built by the British and therefore had the characteristic appearance of a British outpost in the Far East, with barracks and warehouses. This camp became the largest multinational POW camp and a sort of a distribution centre for all the prisoners in southeast Asia. At first there were over 50,000 British and other Commonwealth troops held there, but very quickly work forces of several thousand men were recruited from Changi and sent to various projects in Sumatra, Burma, and Thailand (the Burma-Siam railway) and other Japanese occupied territories. Due to the huge amount of prisoners the Japanese gave responsibility for the administration and daily running of this camp to the prisoners; the guards were mostly Indians from the Indian National Army. The camp was in existence until May 31st 1944, when military prisoners were transferred to Changi prison, while the about 3500 civilians were moved to Sime Road Camp.

CHANGI PRISON was located four kilometers further south (along the coast towards Singapore). This prison was built for the British by American engineers in the 1930's, using Sing-Sing as a model. It had four floors, 440 yards long by 110 yards wide, with walls and the roof made of concrete. In normal times the prison would house 800 prisoners but at one point during the war it had nearer 8000.

If you are interested in learning more about Changi POW Camp, then please follow the link here:

www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/pow/changi

As a follow up to this story I attempted in February (2012) to trace any records or photographs of Tom Roberts from his time as a teacher in Ormskirk. I would like to thank Sarah Baker and Rose Halsall for their input and efforts in trying to track down information for me. Here is their response to my appeal for help;

Hi Steve,

Sorry for the late response but I have been really busy since I got back from my trip to Egypt. I have been speaking to an ex-colleague of Tom's and he is trying to find some old photographs for you. I will be seeing him tomorrow evening so I'll check with him again. I do know that Tom was very highly thought of at Cross Hall School, Wigan Road. That school has now gone and a new school has replaced it, so it is unlikely there will be anything available there. You might like to contact the Lancashire Archive, as they may have something from when Crosshall School ceased to exist in 2001.

Regards, Rose.

Colin Finch, former pupil of Tom Roberts.

In early May 2012 I stumbled across another online recollection from a former pupil of Wigan Road School. It came in the form of a family website recording the history of Colin Finch, where amongst other memories he has written about some of the teachers from his schooldays.

"Moving to Ormskirk meant changing schools. I started in Aughton Street, I’m not sure what it was called but it was there a long time, one entrance was in Moorgate, can't remember much more. I then moved to Greetby Hill Junior School and then at 11, to Wigan Road Secondary Modern as it then known. I used to get into enough trouble there, I was not very good at English or Maths, but Technical drawing and Algebra were my best subjects. On leaving Wigan Road school at 14, I then went to Bootle Tech. College for two years, learning Engineering."

"The teachers we had at Wigan Road included Charlie (Mansion Polish) Fogg, bless him, Richard (Dicky) Thomas, Mr. Fletcher for English, Mr. Hender for Science, Roberts for Biology (Captain Roberts was in the Chindits) and Mr. Ellison was the Headmaster until 1961."

I have made several attempts to make contact with Colin via his website address, but the email has bounced back as unattainable. I sincerely hope he will not mind me using part of his memoirs to illustrate this story about the teaching days of Tommy Roberts.

Update 02/05/2014.

I recently received another email contact from a former pupil of Tom Roberts. Mr. Don Webb told me:

"I attended Wigan Road from 1963 to 1967 and Tom Roberts was our biology teacher. He kept bees in one of the school quadrangles and also had a hive built into one of the lab windows where you could watch the bees working. He often had us working the centrifuge to separate the honey from the combs. He also had a cabinet in the lab with various items of carved ivory that he had brought back with him from Burma. He was a thoroughly decent man and a great teacher."

"Moving to Ormskirk meant changing schools. I started in Aughton Street, I’m not sure what it was called but it was there a long time, one entrance was in Moorgate, can't remember much more. I then moved to Greetby Hill Junior School and then at 11, to Wigan Road Secondary Modern as it then known. I used to get into enough trouble there, I was not very good at English or Maths, but Technical drawing and Algebra were my best subjects. On leaving Wigan Road school at 14, I then went to Bootle Tech. College for two years, learning Engineering."

"The teachers we had at Wigan Road included Charlie (Mansion Polish) Fogg, bless him, Richard (Dicky) Thomas, Mr. Fletcher for English, Mr. Hender for Science, Roberts for Biology (Captain Roberts was in the Chindits) and Mr. Ellison was the Headmaster until 1961."

I have made several attempts to make contact with Colin via his website address, but the email has bounced back as unattainable. I sincerely hope he will not mind me using part of his memoirs to illustrate this story about the teaching days of Tommy Roberts.

Update 02/05/2014.

I recently received another email contact from a former pupil of Tom Roberts. Mr. Don Webb told me:

"I attended Wigan Road from 1963 to 1967 and Tom Roberts was our biology teacher. He kept bees in one of the school quadrangles and also had a hive built into one of the lab windows where you could watch the bees working. He often had us working the centrifuge to separate the honey from the combs. He also had a cabinet in the lab with various items of carved ivory that he had brought back with him from Burma. He was a thoroughly decent man and a great teacher."

Tony's father, Albert Culshaw (REME) in 1942.

Tony's father, Albert Culshaw (REME) in 1942.

Update 15/02/2018.

I was very pleased to receive the following email contact from a former pupil of Ormskirk School. Tony Culshaw told me:

I was a pupil at Ormskirk Secondary Modern from the late 1950s to early the 1960s and taught by Tom Roberts. He certainly got respect from us, being a war hero. I remember one parents evening mum and dad met Tom, as my Biology master, and something strange (at least to me) happened. Tom simply said Burma to dad, who simply replied yes.

Both of them had a walnut hue to their skin, which never seemed to fade, but it did not mean anything to me at the time as dad never spoke about the war. Tom then said Wingate to dad who replied Admin Box, which once again meant nothing to me. They shook hands and called each other brother which confused me. I knew my father had been in Burma but that was about all. He always said he was in the R.E.M.E. and nothing much else.

I had to wait until his funeral a few years ago to hear the full story. He had been in quite a nasty battle with the Japanese, nicknamed the Admin Box and apparently was a Seargent and Mentioned in Dispatches sometime before the end of the war.

I was proud to know Tom Roberts and for a time was the biology monitor for him and so got to see more of his personality. He seemed to have a similar occasional trait to my father. He at school, or my father at home, would be talking and then suddenly stop and be looking at something in the far distance, then return and carry on talking without missing a word. Thinking about this now, I wonder if this was a kind of Thousand Yard Stare and would like to know what they were seeing.

When I was small I could hear my father call out late at night and mother would always tell us he was just dreaming! I have a very battered copy of the SEAC newspaper dad sent home to mother. It is heavily sanitised, filled with all good things and very little blood or guts as you can imagine. All good propaganda for the home front.

I once asked my dad what a war hero looked like, and he told me to look out of the window at the people and remarked: “Every man and woman who went through the war is a hero, and never forget that.” If only we had known the full story from men like Tom Roberts and my father and not just read it from books. Although, most of these men never really spoke about what they did during those years.

I was very pleased to receive the following email contact from a former pupil of Ormskirk School. Tony Culshaw told me:

I was a pupil at Ormskirk Secondary Modern from the late 1950s to early the 1960s and taught by Tom Roberts. He certainly got respect from us, being a war hero. I remember one parents evening mum and dad met Tom, as my Biology master, and something strange (at least to me) happened. Tom simply said Burma to dad, who simply replied yes.

Both of them had a walnut hue to their skin, which never seemed to fade, but it did not mean anything to me at the time as dad never spoke about the war. Tom then said Wingate to dad who replied Admin Box, which once again meant nothing to me. They shook hands and called each other brother which confused me. I knew my father had been in Burma but that was about all. He always said he was in the R.E.M.E. and nothing much else.

I had to wait until his funeral a few years ago to hear the full story. He had been in quite a nasty battle with the Japanese, nicknamed the Admin Box and apparently was a Seargent and Mentioned in Dispatches sometime before the end of the war.

I was proud to know Tom Roberts and for a time was the biology monitor for him and so got to see more of his personality. He seemed to have a similar occasional trait to my father. He at school, or my father at home, would be talking and then suddenly stop and be looking at something in the far distance, then return and carry on talking without missing a word. Thinking about this now, I wonder if this was a kind of Thousand Yard Stare and would like to know what they were seeing.

When I was small I could hear my father call out late at night and mother would always tell us he was just dreaming! I have a very battered copy of the SEAC newspaper dad sent home to mother. It is heavily sanitised, filled with all good things and very little blood or guts as you can imagine. All good propaganda for the home front.

I once asked my dad what a war hero looked like, and he told me to look out of the window at the people and remarked: “Every man and woman who went through the war is a hero, and never forget that.” If only we had known the full story from men like Tom Roberts and my father and not just read it from books. Although, most of these men never really spoke about what they did during those years.

Update 10/03/2018.

I am delighted to announce that a new book recording the wartime experiences of Captain Tommy Roberts has just been published by his family. From the pages of Amazon:

Daughter, Patricia Ireland faithfully presents her father's genuine and unique diary, secretly written when a prisoner of war of the Japanese at Changi in Singapore. The diary, written in tiny writing on exercise book paper was turned into an audio recording by Tommy Roberts in 1986. Helped by these recordings, Patricia has transcribed the diary and produced a valuable and historic record for all to read.

To learn more, please click on the following link:

www.amazon.co.uk/Roll-including-Chindits-Prisoner-Japanese/dp/1547029021/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1520709412&sr=1-1&keywords=roll+on

I am delighted to announce that a new book recording the wartime experiences of Captain Tommy Roberts has just been published by his family. From the pages of Amazon:

Daughter, Patricia Ireland faithfully presents her father's genuine and unique diary, secretly written when a prisoner of war of the Japanese at Changi in Singapore. The diary, written in tiny writing on exercise book paper was turned into an audio recording by Tommy Roberts in 1986. Helped by these recordings, Patricia has transcribed the diary and produced a valuable and historic record for all to read.

To learn more, please click on the following link:

www.amazon.co.uk/Roll-including-Chindits-Prisoner-Japanese/dp/1547029021/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1520709412&sr=1-1&keywords=roll+on

Update 12/02/2022:

I was delighted to receive an email contact via my website from Paul Ireland, who runs a Facebook page in memory of the Wigan Road School where Tommy Roberts taught during the 1950s and 1960s. Paul has now added a post in relation to Tom Roberts and some of the information from this page to his website. To view the Facebook page, please click on the following link: www.facebook.com/OrmskirkCrossHallHighSchool

Update 10/02/2024:

I received a second email contact from Paul Ireland in February 2024:

Hi Steve, I hope you are well, you may remember we spoke about Tommy Roberts a couple of years back about him being a teacher at my old school, well recently I have been donated a number of original school photographs, including one that features on your site. I have scanned this and have sent you a high quality version that you can use on your website if you wish.

Seen below is the wonderful image Paul sent over, which is the same photograph as the version seen at the top of this page, but also contains the names of the teachers featured. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

I was delighted to receive an email contact via my website from Paul Ireland, who runs a Facebook page in memory of the Wigan Road School where Tommy Roberts taught during the 1950s and 1960s. Paul has now added a post in relation to Tom Roberts and some of the information from this page to his website. To view the Facebook page, please click on the following link: www.facebook.com/OrmskirkCrossHallHighSchool

Update 10/02/2024:

I received a second email contact from Paul Ireland in February 2024:

Hi Steve, I hope you are well, you may remember we spoke about Tommy Roberts a couple of years back about him being a teacher at my old school, well recently I have been donated a number of original school photographs, including one that features on your site. I have scanned this and have sent you a high quality version that you can use on your website if you wish.

Seen below is the wonderful image Paul sent over, which is the same photograph as the version seen at the top of this page, but also contains the names of the teachers featured. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 10/04/2018.

Harold Machin.

A a result of reading through Roll On, Tom Roberts' WW2 memoir, some wonderful information about another Longcloth Chindit, Captain Harold Machin has emerged. Here is his story:

Harold Machin.

A a result of reading through Roll On, Tom Roberts' WW2 memoir, some wonderful information about another Longcloth Chindit, Captain Harold Machin has emerged. Here is his story:

A shoulder title for the 15th Punjab Regiment.

A shoulder title for the 15th Punjab Regiment.

Harold Machin was born on the 29th December 1911 and was the son of Harold and Janet Machin from Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire. Harold was a school teacher in civilian life before WW2. It is likely that he enlisted into the Army early in the war, however, his original Army Regiment at enlistment is not known at this time. What we do know, is that he joined the British Indian Army and was posted to the 5/15th Punjab Regiment with the Army No. EC/3203.

The fifth battalion of the 15th Punjab Regiment was raised in India during 1940 and remained at home during the years of WW2, before being disbanded in 1947 with the remnants of the unit being ceded to the Pakistan Army after partition. Harold Machin was posted to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, alongside another officer, Captain C.W. Brazier and joined Brigade Head Quarters at the Saugor training camp on the 27th October 1942. Both men were then placed under Brigade Intelligence Officer, Captain Graham Hosegood, with Harold employed as an interrupter due to his knowledge and expertise in the Japanese language.

In January 1943, the Chindit Brigade began the long journey from the rail station at Jhansi, to its assembly point at Imphal, just prior to crossing the Chindwin River and marching into Burma. One of the nine trains that transported the Chindit Brigade from Jhansi, No. SA1 was the joint responsibility of Brigade-Major George Bromhead and Captain Machin.

On Operation Longcloth, the Chindits troubled Japanese lines of communication during February and March 1943, demolishing various pieces of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. In late March, Wingate called an officers conference and with the added advice of India General Command, decided to close the operation and return to India. On the 29th March, Brigade HQ in the company of No. 7 and No. 8 Column attempted to re-cross the Irrawaddy at a place called Inywa; however, this crossing was abandoned due to enemy interference from the western banks. Wingate took his own dispersal group back into the jungle and waited for over a week before trying to cross again. The other men from Brigade Head Quarters, having now split up into smaller groups of 25-30 men, struggled to find boats to get them across the river and this led to some of the parties trying their luck further south.

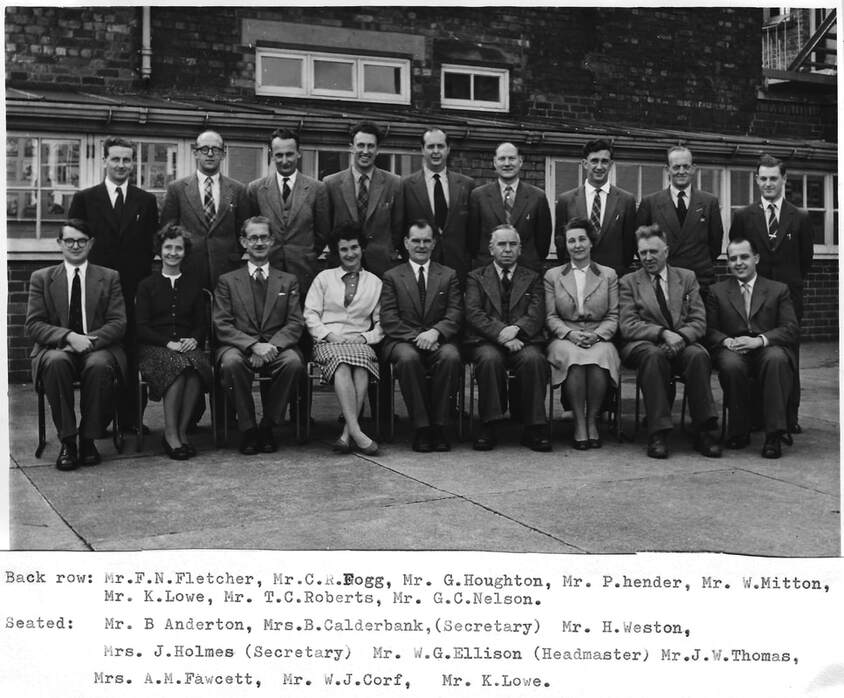

Harold's dispersal party cannot be confirmed, but it seems likely that he formed part of the group which included another officer from Brigade Head Quarters, Albert Vivian Earle. As you will read later, Harold would have an ongoing association with Captain Earle during their long period as prisoners of war in the hands of the Japanese. According to his POW index card, Harold Machin was captured close to the village of Taugaung, situated on the east bank of the Irrawaddy River on the 15th April 1943. Captain Earle was recorded as being captured at the same location just three days later, on the 18th April.

Shown below is a map of the area around Taugaung and the general direction taken by the dispersal groups from Brigade Head Quarters in April 1943.

The fifth battalion of the 15th Punjab Regiment was raised in India during 1940 and remained at home during the years of WW2, before being disbanded in 1947 with the remnants of the unit being ceded to the Pakistan Army after partition. Harold Machin was posted to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, alongside another officer, Captain C.W. Brazier and joined Brigade Head Quarters at the Saugor training camp on the 27th October 1942. Both men were then placed under Brigade Intelligence Officer, Captain Graham Hosegood, with Harold employed as an interrupter due to his knowledge and expertise in the Japanese language.

In January 1943, the Chindit Brigade began the long journey from the rail station at Jhansi, to its assembly point at Imphal, just prior to crossing the Chindwin River and marching into Burma. One of the nine trains that transported the Chindit Brigade from Jhansi, No. SA1 was the joint responsibility of Brigade-Major George Bromhead and Captain Machin.

On Operation Longcloth, the Chindits troubled Japanese lines of communication during February and March 1943, demolishing various pieces of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. In late March, Wingate called an officers conference and with the added advice of India General Command, decided to close the operation and return to India. On the 29th March, Brigade HQ in the company of No. 7 and No. 8 Column attempted to re-cross the Irrawaddy at a place called Inywa; however, this crossing was abandoned due to enemy interference from the western banks. Wingate took his own dispersal group back into the jungle and waited for over a week before trying to cross again. The other men from Brigade Head Quarters, having now split up into smaller groups of 25-30 men, struggled to find boats to get them across the river and this led to some of the parties trying their luck further south.

Harold's dispersal party cannot be confirmed, but it seems likely that he formed part of the group which included another officer from Brigade Head Quarters, Albert Vivian Earle. As you will read later, Harold would have an ongoing association with Captain Earle during their long period as prisoners of war in the hands of the Japanese. According to his POW index card, Harold Machin was captured close to the village of Taugaung, situated on the east bank of the Irrawaddy River on the 15th April 1943. Captain Earle was recorded as being captured at the same location just three days later, on the 18th April.

Shown below is a map of the area around Taugaung and the general direction taken by the dispersal groups from Brigade Head Quarters in April 1943.

Captain Machin was recorded as being held at the Maymyo POW camp at some point between late April and early May 1943. This was confirmed by an escapee also held at the camp, who then completed a debrief report (shown in the gallery at the end of this update) upon reaching Allied territory. It must be presumed from the information given that the escapee in question belonged to the 2nd Burma Rifles and had also served on Operation Longcloth. Most of the prisoners held at Maymyo were moved down to Rangoon Jail in mid-May. This uncomfortable journey was made by rail, with the unfortunate Chindits being placed in overcrowded cattle trucks for the two-day excursion to the capital city.

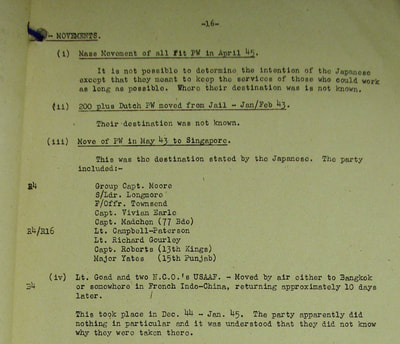

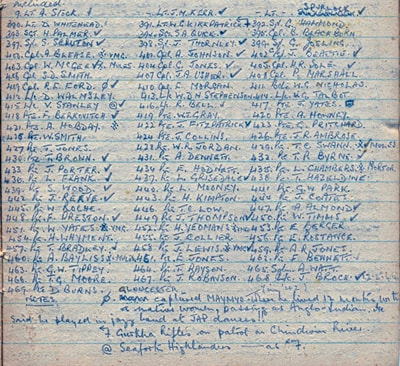

One of the more fascinating details gained from Tom Roberts' book, was that Harold Machin had compiled, or at least obtained a list of the Chindit soldiers held as prisoners or war. It is difficult to say where this listing originated, and whether it was compiled at Maymyo (unlikely), or more probably at Changi, where more information was recorded about prisoners generally and the collation of the POW index cards had begun in earnest by early 1944. Nevertheless, it is a remarkable document and has been an invaluable resource during my research. A copy of the list can be viewed in the gallery at the end of this narrative.

Not long after reaching Rangoon Jail, a group of prisoners including Tom Roberts and Harold Machin were selected by the Kempai-tai (Japanese secret police and akin to the Gestapo), to be transferred to Singapore for further and more intensive interrogation. The Chindits chosen were all officers and had all commanded larger sections of men during the first Wingate expedition, and were obviously thought to hold more knowledge of the operation in 1943. The move took place by aeroplane on the 30th May and the following personnel were sent to the Head Quarters of the Kempai-tai at Singapore:

Group Captain J.W.C. Moore (RAF)

Squadron Leader C. J. Longmore (RAF)

Flight Officer J. E. Townsend (RAF)

Captain Albert Vivian Earle

Captain H. Machin (77 Brigade)

Lieutenant A. Campbell-Paterson

Lieutenant K.R. Gourlie

Captain Roberts (13th King's)

Major R.P Yates (Punjab Regiment)

The above mentioned men were held in the first instance at the old Maternity Hospital on the Changi Road. After the interrogation period was over, they were moved to the much larger Changi POW Camp on the 31st July. Although they had not been in each others company very often during the training for Operation Longcloth in India, or travelled in the same column in Burma, Tom Roberts and Harold Machin would become very good friends at Changi, sharing the same cell-room for most of their incarceration at the camp.

After a fairly comfortable beginning at Changi, in mid-July 1943 Harold contracted dengue fever and suffered with this disease for several weeks before recovering. Both Tom Roberts and Harold decided to keep chickens in the jail as a way of obtaining fresh eggs to supplement the rather monotonous diet of polished white rice. They both worked for the Japanese on the construction of Changi Aerodrome, which would eventually become the site of the International Airport after the war. Harold continued his role of interrupter on the site, explaining the requirements of the Japanese to the Australian and British workforce, whilst Tom Roberts ran a labour gang.

Both men used to enjoy a swim in the ocean at the end of a days work. The Japanese would normally allow the POW's to govern themselves at Changi, being relaxed in the notion that escape for white prisoners was totally unrealistic, with the nearest Allied held territory over one thousand miles away. During their swims, Harold and Tom would discuss amongst other topics, their families back home, religion, military strategies and politics. Tom recalled in his diary on 6th May 1944, that:

Last night, Mache and I were feeling hungry, so we bought a coconut for 80 cents and sat on the veranda, chewing away for about two hours and talking pleasantly with each other. Queer I guess, but I find talking to Mache is good for me and I get enjoyment from his conversation, which is foreign to 99% of the other guy's talk.

On the 30th June 1944, Vivian Earle was given the opportunity to take part in a radio broadcast arranged as propaganda by the Japanese at Changi. He was allowed to send a message to his father and included mention of Tom, Harold and another prisoner from the first Wingate expedition, Lt. Kenneth Raymond Gourlie of the Burma Rifles. All four men sincerely hoped that the message would be heard by their families back home, who at that time had no idea whether their loved-ones were alive or dead. By early January 1945, food prices at Changi had risen sharply through inflation. Harold, going against his normal straight-laced disposition, became involved in black-marketeering inside the jail, selling eggs from his chickens and other contraband such as cigarettes.

On the 4th April 1945, Harold left Changi and was placed in charge of a work party of around 100 men at Bukit Timah. It was at this location, that the Japanese built The Syonan Jinja (Light of the South Shrine) in honour of those soldiers from Japan who had perished during the invasion of Singapore. Tom Roberts remembered the 4th April 1945 in his diary:

Before leaving, Mache told me that should anything befall him, I must contact his parents for him, while he spontaneously promised, that should I not for any reason see England again, he would see that my wife and son would never want. This promise was of great comfort to me.

Harold Machin was liberated on the 3rd September 1945, whilst being held at the Sime Road Camp in Singapore. Tom Roberts was freed from Changi a few days later alongside the other Chindits captured during Operation Longcloth. All men were allowed to write letters home to their families for the first time in two and a half years. Although it could be argued that conditions at Changi were less severe than at other POW camps run by the Japanese during the war, with better access to food stuffs and the opportunity to swim and wash in the sea after the working day was done; it seems ironic, that by being transported there in May 1943, men such as Harold Machin and Tom Roberts would spend four months longer as prisoners of war, than their comrades held at Rangoon Jail, who were liberated in early May 1945.

To conclude this update, shown below is a gallery of images in relation to Captain Harold Machin and his time as a Chindit and a prisoner of war. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. Sadly, Harold Machin passed away in January 1997 aged 85 years.

One of the more fascinating details gained from Tom Roberts' book, was that Harold Machin had compiled, or at least obtained a list of the Chindit soldiers held as prisoners or war. It is difficult to say where this listing originated, and whether it was compiled at Maymyo (unlikely), or more probably at Changi, where more information was recorded about prisoners generally and the collation of the POW index cards had begun in earnest by early 1944. Nevertheless, it is a remarkable document and has been an invaluable resource during my research. A copy of the list can be viewed in the gallery at the end of this narrative.

Not long after reaching Rangoon Jail, a group of prisoners including Tom Roberts and Harold Machin were selected by the Kempai-tai (Japanese secret police and akin to the Gestapo), to be transferred to Singapore for further and more intensive interrogation. The Chindits chosen were all officers and had all commanded larger sections of men during the first Wingate expedition, and were obviously thought to hold more knowledge of the operation in 1943. The move took place by aeroplane on the 30th May and the following personnel were sent to the Head Quarters of the Kempai-tai at Singapore:

Group Captain J.W.C. Moore (RAF)

Squadron Leader C. J. Longmore (RAF)

Flight Officer J. E. Townsend (RAF)

Captain Albert Vivian Earle

Captain H. Machin (77 Brigade)

Lieutenant A. Campbell-Paterson

Lieutenant K.R. Gourlie

Captain Roberts (13th King's)

Major R.P Yates (Punjab Regiment)

The above mentioned men were held in the first instance at the old Maternity Hospital on the Changi Road. After the interrogation period was over, they were moved to the much larger Changi POW Camp on the 31st July. Although they had not been in each others company very often during the training for Operation Longcloth in India, or travelled in the same column in Burma, Tom Roberts and Harold Machin would become very good friends at Changi, sharing the same cell-room for most of their incarceration at the camp.

After a fairly comfortable beginning at Changi, in mid-July 1943 Harold contracted dengue fever and suffered with this disease for several weeks before recovering. Both Tom Roberts and Harold decided to keep chickens in the jail as a way of obtaining fresh eggs to supplement the rather monotonous diet of polished white rice. They both worked for the Japanese on the construction of Changi Aerodrome, which would eventually become the site of the International Airport after the war. Harold continued his role of interrupter on the site, explaining the requirements of the Japanese to the Australian and British workforce, whilst Tom Roberts ran a labour gang.

Both men used to enjoy a swim in the ocean at the end of a days work. The Japanese would normally allow the POW's to govern themselves at Changi, being relaxed in the notion that escape for white prisoners was totally unrealistic, with the nearest Allied held territory over one thousand miles away. During their swims, Harold and Tom would discuss amongst other topics, their families back home, religion, military strategies and politics. Tom recalled in his diary on 6th May 1944, that:

Last night, Mache and I were feeling hungry, so we bought a coconut for 80 cents and sat on the veranda, chewing away for about two hours and talking pleasantly with each other. Queer I guess, but I find talking to Mache is good for me and I get enjoyment from his conversation, which is foreign to 99% of the other guy's talk.

On the 30th June 1944, Vivian Earle was given the opportunity to take part in a radio broadcast arranged as propaganda by the Japanese at Changi. He was allowed to send a message to his father and included mention of Tom, Harold and another prisoner from the first Wingate expedition, Lt. Kenneth Raymond Gourlie of the Burma Rifles. All four men sincerely hoped that the message would be heard by their families back home, who at that time had no idea whether their loved-ones were alive or dead. By early January 1945, food prices at Changi had risen sharply through inflation. Harold, going against his normal straight-laced disposition, became involved in black-marketeering inside the jail, selling eggs from his chickens and other contraband such as cigarettes.

On the 4th April 1945, Harold left Changi and was placed in charge of a work party of around 100 men at Bukit Timah. It was at this location, that the Japanese built The Syonan Jinja (Light of the South Shrine) in honour of those soldiers from Japan who had perished during the invasion of Singapore. Tom Roberts remembered the 4th April 1945 in his diary:

Before leaving, Mache told me that should anything befall him, I must contact his parents for him, while he spontaneously promised, that should I not for any reason see England again, he would see that my wife and son would never want. This promise was of great comfort to me.

Harold Machin was liberated on the 3rd September 1945, whilst being held at the Sime Road Camp in Singapore. Tom Roberts was freed from Changi a few days later alongside the other Chindits captured during Operation Longcloth. All men were allowed to write letters home to their families for the first time in two and a half years. Although it could be argued that conditions at Changi were less severe than at other POW camps run by the Japanese during the war, with better access to food stuffs and the opportunity to swim and wash in the sea after the working day was done; it seems ironic, that by being transported there in May 1943, men such as Harold Machin and Tom Roberts would spend four months longer as prisoners of war, than their comrades held at Rangoon Jail, who were liberated in early May 1945.

To conclude this update, shown below is a gallery of images in relation to Captain Harold Machin and his time as a Chindit and a prisoner of war. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. Sadly, Harold Machin passed away in January 1997 aged 85 years.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and all other contributors 2012.