Too Many Cooks and No Broth to be Had!

There were not surprisingly a number of Indian Army orderlies, servants and other camp followers present on Operation Longcloth. Amongst these were a group of Mess Cooks, some of whom have had mention in the books and other writings in relation to the first Wingate expedition. In no particular order, here is what I know of these gentlemen and their eventual fate in 1943 and beyond.

Mess Cook No. 111 Bale Rana of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and a member of 3 Column on Operation Longcloth.

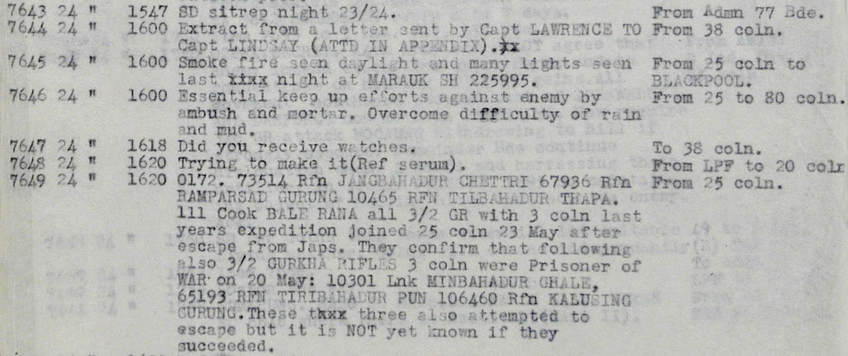

This man was lost to his unit on the 5th April 1943, shortly after the dispersal party he was with had begun their return journey to India. He was officially listed as missing in action on the 10th July, but miraculously turned up again on the 23rd May 1944, when he made contact with a Chindit column from Operation Thursday. He had been held a prisoner of war alongside; 73514 Rfm. Jangbahadur Chettri, 67936 Rfm. Ramparsad Gurung, 10465 Rfm. Tilbahadur Thapa, 10301 Lance Naik Minbahadur Ghale, 65193 Rfm. Tirbahadur Pun and 106460 Rfm. Kalusing Gurung.

As an unexpected twist to this story; back at the battalion Regimental Centre in Dehra Dun, Bale Rana’s wife had steadfastly refused to accept that her husband had been killed in 1943 and refused to journey back to her family home in Nepal. Her faith was rewarded even before Rana’s return in 1944, as she had continued to receive the full family allocation of 15 rupees per month, as opposed to the much reduced rate of just 6 rupees for a widow.

Mess Cook No. 111 Bale Rana of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and a member of 3 Column on Operation Longcloth.

This man was lost to his unit on the 5th April 1943, shortly after the dispersal party he was with had begun their return journey to India. He was officially listed as missing in action on the 10th July, but miraculously turned up again on the 23rd May 1944, when he made contact with a Chindit column from Operation Thursday. He had been held a prisoner of war alongside; 73514 Rfm. Jangbahadur Chettri, 67936 Rfm. Ramparsad Gurung, 10465 Rfm. Tilbahadur Thapa, 10301 Lance Naik Minbahadur Ghale, 65193 Rfm. Tirbahadur Pun and 106460 Rfm. Kalusing Gurung.

As an unexpected twist to this story; back at the battalion Regimental Centre in Dehra Dun, Bale Rana’s wife had steadfastly refused to accept that her husband had been killed in 1943 and refused to journey back to her family home in Nepal. Her faith was rewarded even before Rana’s return in 1944, as she had continued to receive the full family allocation of 15 rupees per month, as opposed to the much reduced rate of just 6 rupees for a widow.

Mess Cook F/88 Chandra Bahadur Chhetri took part in and survived the first Wingate expedition. He continued to serve with 3/2 Gurkha Rifles after returning from Burma in 1943, but was sadly killed the following year on the 30th April 1944, whilst the battalion were part of the 25th Indian Division fighting the Japanese in the Arakan region of the country.

Cook Uma Kant Thapa of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles. This man died on the 23rd December 1943 having survived his participation on Operation Longcloth. The circumstances of his death are unknown and he is remembered upon Face 58 of the Rangoon Memorial.

Cook Harka Bahadur Magar also of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles died on the 15th July 1943 and was almost certainly held as a prisoner of war for a period before his death. Harka is also remembered upon Face 58 of the Rangoon Memorial.

The Marie Brothers, were two Madrasi Cooks from the Indian Army Service Corps who served with Southern Group on Operation Longcloth. These two men were mentioned in the book Wingate’s Raiders, by Charles Rolo, as being with Major J.B. Jefferies during dispersal from Burma in March/April 1943.

From the pages of Wingate's Raiders:

Jefferies' men trekked back five miles to their last bivouac to collect the supplies they had hidden in the bushes. The Japs had passed through this area in force, but had not discovered the cache. After a brief halt the Chindits pushed on. The next stretch of marching was one of the most nerve-racking in the campaign. The jungle was criss-crossed with false trails and the footprints of Japanese patrols, and Jefferies had a hard time setting a course. The Japs were probing for them like sappers for a mine, and all talking was forbidden.

At this point one of the Maries —the Madrasi cooks—who at the last mail-drop had received bad news from home, cracked under the strain and started chanting hymns in Madrasi. He marched along in a trance and nothing could silence him. When the party bivouacked at midnight on March 23rd he vanished into the jungle. Jefferies was reluctant to leave him to the Japs for he had shown great bravery throughout the campaign and had been recommended for a decoration for his conduct at the Kyaikthin railway engagement.

At dawn they hunted around for about an hour and found him sitting beside a clump of bamboo, completely shell-shocked, dolefully mumbling prayers. They pulled him to his feet and led him back into line. In a few days he was normal again, and eventually got back to India alive. All that day, March 24th, they marched to the sound of heavy firing to the north, where Wingate was in action against the Japanese garrison at Baw. They reached the rendezvous five miles from Baw village just before dusk. There was no one there. All around were empty cartridge cases and other signs of battle. Jefferies had reason to believe that Wingate had probably moved north-east towards the Shweli River, and so decided to push on in that direction.

As they were marching along that night one of the mule-leaders came face to face with a red-capped Japanese officer, probably a Brigadier, sitting in a bamboo shelter by the side of the trail. They saw each other at the same time. The Englishman reached for his revolver, but the Jap spun round and leapt into the undergrowth, yelling, British, British! " Just after they had bivouacked in the small hours of the morning a sentry reported that the Japanese had crept up under cover of the noise made by the mules, and were about to attack. Jefferies led the men off thirty yards to the flank into a firing position.

They waited for a few minutes, but nothing happened. Jefferies finally grew bored with waiting and, together with another officer, decided to stalk the position where the sentry had spotted the enemy. When they had crawled to within fifteen yards Jefferies whispered, "Come on now, let's go in boldly." They fixed bayonets and charged, in the next minute they were stumbling over the sleeping bodies of the two Maries.

Both the Marie brothers had lived previously in Burma and could speak Burmese, Gurkhali, Tamil and Hindustani. After most supply drops they would whip up a delicious stew using all the ingredients received from the drop that day. They were very popular with all the troops on Operation Longcloth.

Mess Cook PF/31 Gyalbo Sing Tamang was reported killed in May 1943 and did not return from Burma. He is also remembered upon Face 58 of the Rangoon Memorial located at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

Cook 256 Parbulal Limbu from the 10th Regiment of the Gurkha Rifles, fought with 8 Column on Operation Longcloth and dispersed alongside Lt. Dominic Neill during April/May 1943. Lt. Neill remembered Parbulal in his memoir, entitled One More River:

You may wonder what happened to my other 8 Column Gurkhas from 1943? 67892 Rifleman Dalbir Rana, my Syce from the 6th Regiment, was one of only two of my men from other regiments who asked to remain with our 3rd Battalion. He fought in the Arakan with us and finally went on pension in 1955, when I was Adjutant at Lehra. The other soldier to stay with us was 256 Cook Parbulal Limbu of the 10th Regiment. He eventually became my company cook in B Company and eventually went on pension or discharge from Malaya in the late 1940's or early 1950's.

Mess Cook Parman Sing Thapa of 3 Column. This Gurkha was wounded in action during 3 Column's return journey across the Irrawaddy River in late March 1943. Coming under Japanese mortar fire, the Chindits were caught in an exposed position; Lt. Harold James and his platoon, acting in a defensive role, enabled the rest of the column plus its wounded to gain cover in the surrounding jungle. Later, Major Calvert was able to place the casualties from this action with the Headman of Ponpongyi village. He recalled:

After the column had proceeded another four miles, it became obvious that some of the wounded, who were being carried on litters and on horseback could not possibly continue with the column. The Medical Officer, Captain Ras, had the three worst cases, Cook Parman Sing Thapa, Water Carrier Motilal Thapa and a Burma Rifleman transferred into a bullock cart and took them to the village of Ponpongyi, where he left them in the care of the Headman, together with medical supplies and money.

Neither Parman Sing Thapa or Water Carrier Motilal Thapa appear in the online records of the CWGC and so it is unclear what happened to them after being left with the Headman of Ponpongyi.

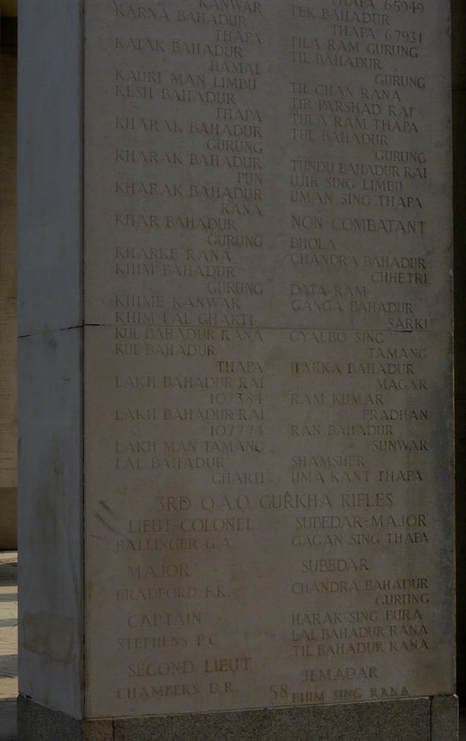

Seen below is a photograph of Face 58 of the Rangoon Memorial, showing the inscriptions for; Chandra Bahadur Chhetri, Gyalbo Sing Tamang, Harka Bahadur Magar and Uma Kant Thapa. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Cook Uma Kant Thapa of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles. This man died on the 23rd December 1943 having survived his participation on Operation Longcloth. The circumstances of his death are unknown and he is remembered upon Face 58 of the Rangoon Memorial.

Cook Harka Bahadur Magar also of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles died on the 15th July 1943 and was almost certainly held as a prisoner of war for a period before his death. Harka is also remembered upon Face 58 of the Rangoon Memorial.

The Marie Brothers, were two Madrasi Cooks from the Indian Army Service Corps who served with Southern Group on Operation Longcloth. These two men were mentioned in the book Wingate’s Raiders, by Charles Rolo, as being with Major J.B. Jefferies during dispersal from Burma in March/April 1943.

From the pages of Wingate's Raiders:

Jefferies' men trekked back five miles to their last bivouac to collect the supplies they had hidden in the bushes. The Japs had passed through this area in force, but had not discovered the cache. After a brief halt the Chindits pushed on. The next stretch of marching was one of the most nerve-racking in the campaign. The jungle was criss-crossed with false trails and the footprints of Japanese patrols, and Jefferies had a hard time setting a course. The Japs were probing for them like sappers for a mine, and all talking was forbidden.

At this point one of the Maries —the Madrasi cooks—who at the last mail-drop had received bad news from home, cracked under the strain and started chanting hymns in Madrasi. He marched along in a trance and nothing could silence him. When the party bivouacked at midnight on March 23rd he vanished into the jungle. Jefferies was reluctant to leave him to the Japs for he had shown great bravery throughout the campaign and had been recommended for a decoration for his conduct at the Kyaikthin railway engagement.

At dawn they hunted around for about an hour and found him sitting beside a clump of bamboo, completely shell-shocked, dolefully mumbling prayers. They pulled him to his feet and led him back into line. In a few days he was normal again, and eventually got back to India alive. All that day, March 24th, they marched to the sound of heavy firing to the north, where Wingate was in action against the Japanese garrison at Baw. They reached the rendezvous five miles from Baw village just before dusk. There was no one there. All around were empty cartridge cases and other signs of battle. Jefferies had reason to believe that Wingate had probably moved north-east towards the Shweli River, and so decided to push on in that direction.

As they were marching along that night one of the mule-leaders came face to face with a red-capped Japanese officer, probably a Brigadier, sitting in a bamboo shelter by the side of the trail. They saw each other at the same time. The Englishman reached for his revolver, but the Jap spun round and leapt into the undergrowth, yelling, British, British! " Just after they had bivouacked in the small hours of the morning a sentry reported that the Japanese had crept up under cover of the noise made by the mules, and were about to attack. Jefferies led the men off thirty yards to the flank into a firing position.

They waited for a few minutes, but nothing happened. Jefferies finally grew bored with waiting and, together with another officer, decided to stalk the position where the sentry had spotted the enemy. When they had crawled to within fifteen yards Jefferies whispered, "Come on now, let's go in boldly." They fixed bayonets and charged, in the next minute they were stumbling over the sleeping bodies of the two Maries.

Both the Marie brothers had lived previously in Burma and could speak Burmese, Gurkhali, Tamil and Hindustani. After most supply drops they would whip up a delicious stew using all the ingredients received from the drop that day. They were very popular with all the troops on Operation Longcloth.

Mess Cook PF/31 Gyalbo Sing Tamang was reported killed in May 1943 and did not return from Burma. He is also remembered upon Face 58 of the Rangoon Memorial located at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

Cook 256 Parbulal Limbu from the 10th Regiment of the Gurkha Rifles, fought with 8 Column on Operation Longcloth and dispersed alongside Lt. Dominic Neill during April/May 1943. Lt. Neill remembered Parbulal in his memoir, entitled One More River:

You may wonder what happened to my other 8 Column Gurkhas from 1943? 67892 Rifleman Dalbir Rana, my Syce from the 6th Regiment, was one of only two of my men from other regiments who asked to remain with our 3rd Battalion. He fought in the Arakan with us and finally went on pension in 1955, when I was Adjutant at Lehra. The other soldier to stay with us was 256 Cook Parbulal Limbu of the 10th Regiment. He eventually became my company cook in B Company and eventually went on pension or discharge from Malaya in the late 1940's or early 1950's.

Mess Cook Parman Sing Thapa of 3 Column. This Gurkha was wounded in action during 3 Column's return journey across the Irrawaddy River in late March 1943. Coming under Japanese mortar fire, the Chindits were caught in an exposed position; Lt. Harold James and his platoon, acting in a defensive role, enabled the rest of the column plus its wounded to gain cover in the surrounding jungle. Later, Major Calvert was able to place the casualties from this action with the Headman of Ponpongyi village. He recalled:

After the column had proceeded another four miles, it became obvious that some of the wounded, who were being carried on litters and on horseback could not possibly continue with the column. The Medical Officer, Captain Ras, had the three worst cases, Cook Parman Sing Thapa, Water Carrier Motilal Thapa and a Burma Rifleman transferred into a bullock cart and took them to the village of Ponpongyi, where he left them in the care of the Headman, together with medical supplies and money.

Neither Parman Sing Thapa or Water Carrier Motilal Thapa appear in the online records of the CWGC and so it is unclear what happened to them after being left with the Headman of Ponpongyi.

Seen below is a photograph of Face 58 of the Rangoon Memorial, showing the inscriptions for; Chandra Bahadur Chhetri, Gyalbo Sing Tamang, Harka Bahadur Magar and Uma Kant Thapa. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Cook Shway Sike or Forsyth to his comrades. On 5 Column's return journey from the Irrawaddy to the Chindwin in April 1943, Major Fergusson's dispersal party picked up along the way a Chinese resident from the Burmese village of Pakaw. From his book, Beyond the Chindwin, Fergusson recalled:

After Denny Sharp had moved off westward and just before our meal was served, John Fraser was buttonhold by a ragged-looking man and engaged in earnest conversation. This was a Chinaman, who was married to a Burmese in Pinlebu, where he had been a rice-merchant. Fleeing hither and thither before the Japs, he had fetched up in Pakaw, where he had been living for some months. He was anxious to work his passage to India and said he would do anything or everything for us if only we would take him with us. I had no objection and he rushed off to collect his scanty belongings.

A few days later, as the column entered the Lower Meza Valley, Major Fergusson updated his thoughts on Shway Sike:

Our newly acquired Chinaman was turning out a treasure. He was an excellent cook, but his chief virtue was as a maker of cigarettes. We had laid in a large stock of Burmese tobacco and our only shortage was paper to roll it in. I still had a few pages of John Fraser's notebook, but was soon to be reduced to smoking Ayala's Angel, a World's Classic from the Oxford University Press, printed on paper admirably suited to the purpose. I was a little distressed at the thought of what Sir Humphrey Milford and Mr. John Johnson, printer to the University, would have to say if they knew to what use it was being put.

I remember Peter Dorans had a good deal of trouble in getting Shway Sike's name right. In the end, he made up his mind that the name was really Forsyth, and Forsyth he became. After we got back to India, Forsyth received the important appointment of Wine Waiter in the Officers' Mess (Jhansi) of the Burma Rifles.

Mess Cook Sivalingum (Fu Manchu) was a Madrasi cook for Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth and is mentioned in several books about the expedition. As the Chindit Brigade made their first approach to the Chindwin River in February 1943, there number included a group of newspaper war correspondents. One of these, Alaric Jacob from the Daily Express remembered:

On the morning of the crossing the column bivouaced in the half-jungle. The men and officers sat all around, digging into their bully beef and biscuits. Wingate, sitting just to my left informed me that his Madrasi cook, whom everyone seemed to call Fu Manchu, would make me my tea and breakfast. He had been fortunate to survive last year's retreat, but had volunteered to go back in as Wingate's personal cook. Although we only stayed with the Chindits for another few days, I was pleased to discover later that Fu Manchu had managed to regain India for a second time in late April and alongside the Brigadier.

After Denny Sharp had moved off westward and just before our meal was served, John Fraser was buttonhold by a ragged-looking man and engaged in earnest conversation. This was a Chinaman, who was married to a Burmese in Pinlebu, where he had been a rice-merchant. Fleeing hither and thither before the Japs, he had fetched up in Pakaw, where he had been living for some months. He was anxious to work his passage to India and said he would do anything or everything for us if only we would take him with us. I had no objection and he rushed off to collect his scanty belongings.

A few days later, as the column entered the Lower Meza Valley, Major Fergusson updated his thoughts on Shway Sike:

Our newly acquired Chinaman was turning out a treasure. He was an excellent cook, but his chief virtue was as a maker of cigarettes. We had laid in a large stock of Burmese tobacco and our only shortage was paper to roll it in. I still had a few pages of John Fraser's notebook, but was soon to be reduced to smoking Ayala's Angel, a World's Classic from the Oxford University Press, printed on paper admirably suited to the purpose. I was a little distressed at the thought of what Sir Humphrey Milford and Mr. John Johnson, printer to the University, would have to say if they knew to what use it was being put.

I remember Peter Dorans had a good deal of trouble in getting Shway Sike's name right. In the end, he made up his mind that the name was really Forsyth, and Forsyth he became. After we got back to India, Forsyth received the important appointment of Wine Waiter in the Officers' Mess (Jhansi) of the Burma Rifles.

Mess Cook Sivalingum (Fu Manchu) was a Madrasi cook for Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth and is mentioned in several books about the expedition. As the Chindit Brigade made their first approach to the Chindwin River in February 1943, there number included a group of newspaper war correspondents. One of these, Alaric Jacob from the Daily Express remembered:

On the morning of the crossing the column bivouaced in the half-jungle. The men and officers sat all around, digging into their bully beef and biscuits. Wingate, sitting just to my left informed me that his Madrasi cook, whom everyone seemed to call Fu Manchu, would make me my tea and breakfast. He had been fortunate to survive last year's retreat, but had volunteered to go back in as Wingate's personal cook. Although we only stayed with the Chindits for another few days, I was pleased to discover later that Fu Manchu had managed to regain India for a second time in late April and alongside the Brigadier.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2017.