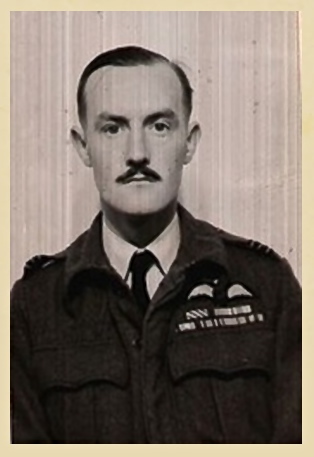

Flight-Lieutenant Albert Tooth

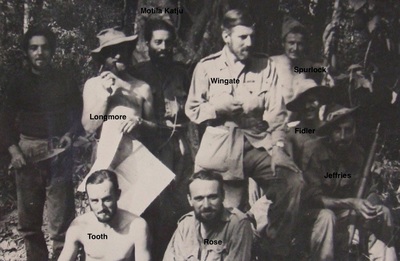

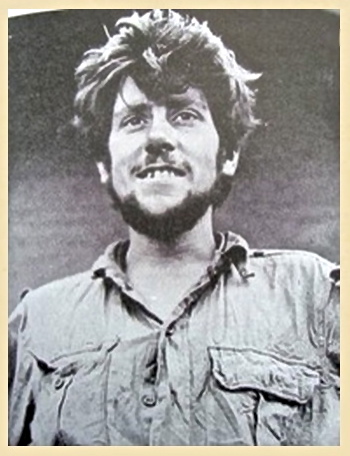

Albert Tooth in April 1943.

Albert Tooth in April 1943.

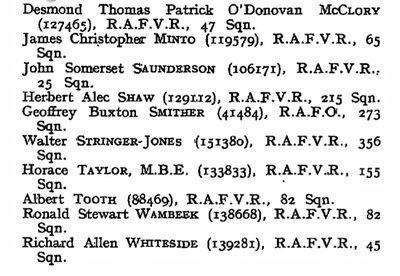

Albert Tooth was born on the 7th January 1918, in Chorlton, a suburban area of Manchester. He served during the years of WW2 in the RAF and in August 1942, whilst with 82 Squadron in India, volunteered for a secret and special mission which required Air Liaison and radio expertise.

88469 Flight-Lieutenant Albert Tooth joined his Chindit comrades in February 1943 and was posted to Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters, working directly under Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore, the senior RAF Officer in 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Another member of Brigade HQ, Cipher Officer Willie Wilding, remembered Flight-Lieutenant Tooth's rather gloomy demeanour after the Brigade's first day of marching in February 1943:

Albert Tooth was 2 i/c to Squadron Leader Longmore and was usually a cheerful soul, but on this first day's march he came upon me during the midday break, whilst I was working away with my ciphers. He said rather mournfully, 'Twenty-four hours ago I was drinking gin in New Delhi and now I find myself an infantryman and your Brigadier has put me in charge of these elephants. I'll bet they will all die and the Army will stop their value from my own pay.' He need not of worried, as we only took them as far as the Chindwin River and they all survived. In any case, he was no more in charge than I was, the elephants made it quite clear that they only took orders from their oozies, and the oozies were an independent lot.

Wingate and his Brigade HQ moved through the jungles of Burma during the first few weeks of Operation Longcloth, orchestrating the Chindit columns of Northern Group as they carried out their various pre-arranged assignments and demolitions. For the most part things went well and the Brigade suffered only minor casualties. Albert Tooth and Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore successfully delivered their side of the bargain and brought in the planes of 31 Squadron to feed and re-equip the marching Chindit columns.

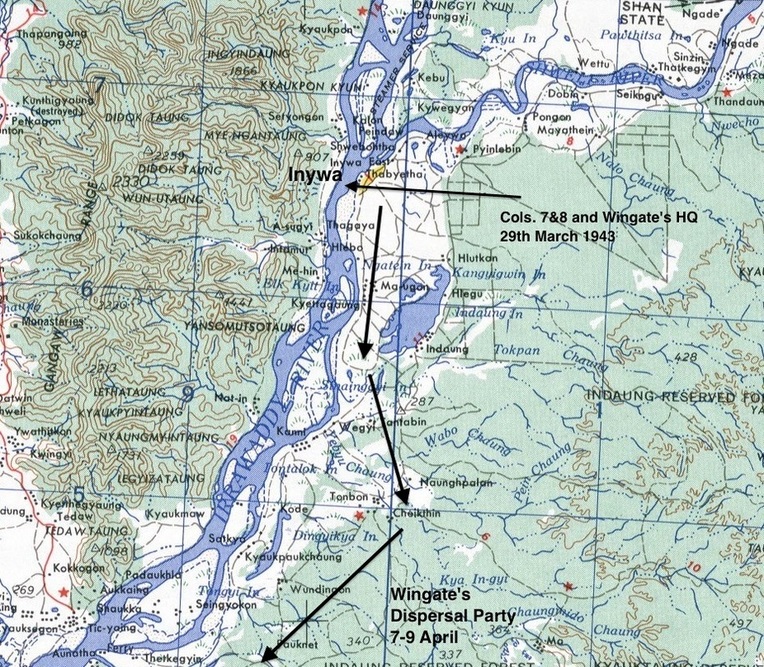

By early April 1943, Wingate and his Brigade were planning their exit from Burma after six weeks of raiding behind enemy lines. On the 29th March, three Chindit units (Columns 7 and 8, plus Brigade HQ) had massed on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River near the town of Inywa. The idea was to get across this wide expanse of water as quickly as possible and then, once over, move off westwards and return to India. Wingate had previously crossed the Irrawaddy at Inywa on the outward journey and thought the Japanese would not expect him to retrace his steps.

Unfortunately, the crossing was contested by a large patrol of Japanese soldiers positioned on the opposite bank of the river. The men in the leading boats soon came under severe machine gun and mortar fire, resulting in many casualties. Wingate, after a speedy consultation with his column commanders, decided to call off the crossing and the dispirited Chindits melted away into the jungle. Columns 7 and 8 soon moved away from the Irrawaddy, both heading roughly south-east. Wingate took his men deep in to the surrounding scrub-jungle close to Inywa, where they would wait patiently for several days until the heat had died down and the enemy had left the area.

During their time hiding out in the jungle, Wingate gave orders for the remaining mules to be killed and that the men should eat the mule flesh to bolster their depleted rations. He also split his Head Quarters up at this time into smaller dispersal groups of around 25-35 men per party. On 7th April, Wingate and his dispersal party (some 43 men) made a second attempt at crossing the Irrawaddy, this time 25 miles south of Inywa. For two days they searched the riverbank for boats, but Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles could only find one boat and this would take only seven people at a time. They began crossing late that afternoon, but when half of the party were over, automatic fire was heard from the north and the native boatman made off with his craft, leaving the rest of the men stranded on the east bank.

Those who successfully made it across the river included Wingate, Majors Anderson and Jefferies, Captains Aung Thin and Motilal Katju, and twenty-four Other Ranks. They were not, however, on the west bank of the river. They were in fact, on an island in the middle of the Irrawaddy and so they immediately moved on towards the only village (Nyaungbintha), where they found another large boat and made the final crossing at dusk. Once over, they moved on for a couple of miles and then lay up for the night. The mosquitoes in this area were intolerable and they got very little sleep.

Albert Tooth was in the last party waiting to cross the river, together with Squadron Leader Longmore, Flight Sergeant Fidler, Lieutenant Rose of the Gurkhas, Private Dermody and Private Weston of the King's and Signaller Eric Hutchins. Eric Hutchins recalled:

The first six boat parties made their way safely to the opposite bank. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the opposite bank we could find no trace of the others. Wingate's excuse when we met him later, was he 'thought' we had been captured by the Japanese, whereas he had abandoned us without maps or any means of finding our way back to our own lines.

So we set out west only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Our problems now really began, because we could not find a suitable boat. Eventually we found a boat that had seen better days and decided to take a chance crossing at night, using our rifles as oars. Of course the inevitable happened and the boat capsized.

I and others swam to the west shore, where we had to rescue two of our party who were clutching on to a floating plant because they could not swim. At light of day we found that Squadron Leader Longmore was missing. Later at the end of the war I found out that he had remained clutching the boat and floated down river and was eventually captured. We found we were on another island and right opposite a very large village and most of the inhabitants walked across the shallow water to the island, presumably out of curiosity.

We had lost everything when the boat capsized and had no arms to defend ourselves, except that I still had a hand grenade. We went with the villagers and enjoyed a meal of rice and obtained two sacks of rice, cooking pans, a flint stone to make a fire, salt and juggery, the latter unrefined sugar.

Suddenly there was a commotion in the village and the locals started to disperse, which was a signal to us that the Japs had arrived. We made a quick retreat and proceeded to climb the hills behind the village and make our way westwards. Our progress after that was mainly at night, avoiding paths and villages. I remember the beautiful clear moonlit nights with the stars to guide us. I often look for a constellation set at dead 270 degrees which we used as our direction arrow as we kept walking westwards.

Daytime was spent trying to sleep in the intense heat with no water, setting out at dusk to find water and cook a meal. I was suffering severely from dysentery, but somehow raised the strength to carry on. As we neared the Chindwin we found a small chaung in which were some pools of water containing fish. We caught one by swimming under water, but then became greedy and thought if we threw my grenade into the water we could have a real feast. This was not to be because the grenade failed to explode as I had forgotten to prime it.

On seeing the river valley of the Chindwin we now became over-confident and started to abandon our policy of avoiding footpaths. On rounding a bend we ran into a Japanese sentry guarding the path. We immediately plunged into the jungle to our left, but Weston was captured because he was too weak to react quickly. We were forced to stand in a marsh for thirty-six hours while the Japs set fire to it to try to draw us out. Meanwhile we could hear the screams of Weston as they slowly tortured him to death with their bayonets.

On the second night we came out of the marsh only to walk straight through the Jap occupied village. We walked on down the path leading to the Chindwin and then, practising the usual dispersal drill on leaving a path, hid in the jungle nearby. Within fifteen minutes a party of Japs came down the track, following our footprints by torch light. Fortunately for us they hesitated where our footprints finished and then carried on. This was our cue and we retreated deeper into the jungle.

Within half an hour they were back searching the spot we had left. We were now under real pressure and headed for the Chindwin, but could not find a boat to cross. We were walking along the path on the river bank and came to a small clearing with Lieutenant Rose leading. He suddenly turned round and yelled Japs' and in the sudden rush to retreat I fell over. I scrambled to my feet, leaving behind the rice sack I was carrying. The others had a good fifty yards' start on me and machine gun bullets were whizzing all around. I think I broke the world record for 200 yards and reached the jungle on the opposite side of the clearing before the others.

Here we lost Lieutenant Rose and I heard after the war he was later captured and also survived the prison camp. We decided to regain the hills and walk northwards hoping there would be fewer Japs to encounter in that direction. We came upon a hut in the middle of a paddy field and found a native sitting inside. He immediately beckoned us to lie down in the paddy and pointed to a road about fifty yards away where Jap lorries were moving. He indicated to follow him crawling on our bellies to a small copse, it was here that our miracle occurred.

He brought us food twice a day for three days while we got our strength back. He could not get us a boat but when we drew bamboo poles he understood and on each night visit he brought two bamboo poles. Finally we had enough to make a raft and took them down to the river at the dead of night and our saviour tied them together. We had no money and could not reward him, but gave him a note saying how he had helped us and that he should be rewarded by the British if he produced the document. This man, a complete stranger, possibly a Buddhist, displayed all the ethics of a Good Samaritan and has remained in my deepest thoughts all my life. That day in 1943 on the banks of the Chindwin I learned to believe in miracles.

Albert Tooth, Alan Fidler, Eric Hutchins and Pte. Dermody were the only survivors from that last boat over the Irrawaddy. These four men were picked up a patrol of the 3/5 Gurkha Rifles on the 30th April at the Chindwin River. Cecil Longmore and Lewis Rose would spend two years as prisoners of war inside Rangoon Jail before being liberated on the 29th April 1945. Pte. Robert Weston of 142 Commando was sadly killed by the Japanese on the eastern banks of the Chindwin, just a few short miles from Allied held territory.

88469 Flight-Lieutenant Albert Tooth joined his Chindit comrades in February 1943 and was posted to Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters, working directly under Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore, the senior RAF Officer in 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Another member of Brigade HQ, Cipher Officer Willie Wilding, remembered Flight-Lieutenant Tooth's rather gloomy demeanour after the Brigade's first day of marching in February 1943:

Albert Tooth was 2 i/c to Squadron Leader Longmore and was usually a cheerful soul, but on this first day's march he came upon me during the midday break, whilst I was working away with my ciphers. He said rather mournfully, 'Twenty-four hours ago I was drinking gin in New Delhi and now I find myself an infantryman and your Brigadier has put me in charge of these elephants. I'll bet they will all die and the Army will stop their value from my own pay.' He need not of worried, as we only took them as far as the Chindwin River and they all survived. In any case, he was no more in charge than I was, the elephants made it quite clear that they only took orders from their oozies, and the oozies were an independent lot.

Wingate and his Brigade HQ moved through the jungles of Burma during the first few weeks of Operation Longcloth, orchestrating the Chindit columns of Northern Group as they carried out their various pre-arranged assignments and demolitions. For the most part things went well and the Brigade suffered only minor casualties. Albert Tooth and Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore successfully delivered their side of the bargain and brought in the planes of 31 Squadron to feed and re-equip the marching Chindit columns.

By early April 1943, Wingate and his Brigade were planning their exit from Burma after six weeks of raiding behind enemy lines. On the 29th March, three Chindit units (Columns 7 and 8, plus Brigade HQ) had massed on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River near the town of Inywa. The idea was to get across this wide expanse of water as quickly as possible and then, once over, move off westwards and return to India. Wingate had previously crossed the Irrawaddy at Inywa on the outward journey and thought the Japanese would not expect him to retrace his steps.

Unfortunately, the crossing was contested by a large patrol of Japanese soldiers positioned on the opposite bank of the river. The men in the leading boats soon came under severe machine gun and mortar fire, resulting in many casualties. Wingate, after a speedy consultation with his column commanders, decided to call off the crossing and the dispirited Chindits melted away into the jungle. Columns 7 and 8 soon moved away from the Irrawaddy, both heading roughly south-east. Wingate took his men deep in to the surrounding scrub-jungle close to Inywa, where they would wait patiently for several days until the heat had died down and the enemy had left the area.

During their time hiding out in the jungle, Wingate gave orders for the remaining mules to be killed and that the men should eat the mule flesh to bolster their depleted rations. He also split his Head Quarters up at this time into smaller dispersal groups of around 25-35 men per party. On 7th April, Wingate and his dispersal party (some 43 men) made a second attempt at crossing the Irrawaddy, this time 25 miles south of Inywa. For two days they searched the riverbank for boats, but Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles could only find one boat and this would take only seven people at a time. They began crossing late that afternoon, but when half of the party were over, automatic fire was heard from the north and the native boatman made off with his craft, leaving the rest of the men stranded on the east bank.

Those who successfully made it across the river included Wingate, Majors Anderson and Jefferies, Captains Aung Thin and Motilal Katju, and twenty-four Other Ranks. They were not, however, on the west bank of the river. They were in fact, on an island in the middle of the Irrawaddy and so they immediately moved on towards the only village (Nyaungbintha), where they found another large boat and made the final crossing at dusk. Once over, they moved on for a couple of miles and then lay up for the night. The mosquitoes in this area were intolerable and they got very little sleep.

Albert Tooth was in the last party waiting to cross the river, together with Squadron Leader Longmore, Flight Sergeant Fidler, Lieutenant Rose of the Gurkhas, Private Dermody and Private Weston of the King's and Signaller Eric Hutchins. Eric Hutchins recalled:

The first six boat parties made their way safely to the opposite bank. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the opposite bank we could find no trace of the others. Wingate's excuse when we met him later, was he 'thought' we had been captured by the Japanese, whereas he had abandoned us without maps or any means of finding our way back to our own lines.

So we set out west only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Our problems now really began, because we could not find a suitable boat. Eventually we found a boat that had seen better days and decided to take a chance crossing at night, using our rifles as oars. Of course the inevitable happened and the boat capsized.

I and others swam to the west shore, where we had to rescue two of our party who were clutching on to a floating plant because they could not swim. At light of day we found that Squadron Leader Longmore was missing. Later at the end of the war I found out that he had remained clutching the boat and floated down river and was eventually captured. We found we were on another island and right opposite a very large village and most of the inhabitants walked across the shallow water to the island, presumably out of curiosity.

We had lost everything when the boat capsized and had no arms to defend ourselves, except that I still had a hand grenade. We went with the villagers and enjoyed a meal of rice and obtained two sacks of rice, cooking pans, a flint stone to make a fire, salt and juggery, the latter unrefined sugar.

Suddenly there was a commotion in the village and the locals started to disperse, which was a signal to us that the Japs had arrived. We made a quick retreat and proceeded to climb the hills behind the village and make our way westwards. Our progress after that was mainly at night, avoiding paths and villages. I remember the beautiful clear moonlit nights with the stars to guide us. I often look for a constellation set at dead 270 degrees which we used as our direction arrow as we kept walking westwards.

Daytime was spent trying to sleep in the intense heat with no water, setting out at dusk to find water and cook a meal. I was suffering severely from dysentery, but somehow raised the strength to carry on. As we neared the Chindwin we found a small chaung in which were some pools of water containing fish. We caught one by swimming under water, but then became greedy and thought if we threw my grenade into the water we could have a real feast. This was not to be because the grenade failed to explode as I had forgotten to prime it.

On seeing the river valley of the Chindwin we now became over-confident and started to abandon our policy of avoiding footpaths. On rounding a bend we ran into a Japanese sentry guarding the path. We immediately plunged into the jungle to our left, but Weston was captured because he was too weak to react quickly. We were forced to stand in a marsh for thirty-six hours while the Japs set fire to it to try to draw us out. Meanwhile we could hear the screams of Weston as they slowly tortured him to death with their bayonets.

On the second night we came out of the marsh only to walk straight through the Jap occupied village. We walked on down the path leading to the Chindwin and then, practising the usual dispersal drill on leaving a path, hid in the jungle nearby. Within fifteen minutes a party of Japs came down the track, following our footprints by torch light. Fortunately for us they hesitated where our footprints finished and then carried on. This was our cue and we retreated deeper into the jungle.

Within half an hour they were back searching the spot we had left. We were now under real pressure and headed for the Chindwin, but could not find a boat to cross. We were walking along the path on the river bank and came to a small clearing with Lieutenant Rose leading. He suddenly turned round and yelled Japs' and in the sudden rush to retreat I fell over. I scrambled to my feet, leaving behind the rice sack I was carrying. The others had a good fifty yards' start on me and machine gun bullets were whizzing all around. I think I broke the world record for 200 yards and reached the jungle on the opposite side of the clearing before the others.

Here we lost Lieutenant Rose and I heard after the war he was later captured and also survived the prison camp. We decided to regain the hills and walk northwards hoping there would be fewer Japs to encounter in that direction. We came upon a hut in the middle of a paddy field and found a native sitting inside. He immediately beckoned us to lie down in the paddy and pointed to a road about fifty yards away where Jap lorries were moving. He indicated to follow him crawling on our bellies to a small copse, it was here that our miracle occurred.

He brought us food twice a day for three days while we got our strength back. He could not get us a boat but when we drew bamboo poles he understood and on each night visit he brought two bamboo poles. Finally we had enough to make a raft and took them down to the river at the dead of night and our saviour tied them together. We had no money and could not reward him, but gave him a note saying how he had helped us and that he should be rewarded by the British if he produced the document. This man, a complete stranger, possibly a Buddhist, displayed all the ethics of a Good Samaritan and has remained in my deepest thoughts all my life. That day in 1943 on the banks of the Chindwin I learned to believe in miracles.

Albert Tooth, Alan Fidler, Eric Hutchins and Pte. Dermody were the only survivors from that last boat over the Irrawaddy. These four men were picked up a patrol of the 3/5 Gurkha Rifles on the 30th April at the Chindwin River. Cecil Longmore and Lewis Rose would spend two years as prisoners of war inside Rangoon Jail before being liberated on the 29th April 1945. Pte. Robert Weston of 142 Commando was sadly killed by the Japanese on the eastern banks of the Chindwin, just a few short miles from Allied held territory.

After recuperating in hospital for several weeks, F/Lt. Tooth wrote down a rough diary of events which covered his return journey across the Irrawaddy and the march back to the Chindwin River. Seen below is a general transcription of his narrative which describes his three week odyssey between the two rivers. To read more about Brigadier Wingate's return to India and how it compares to that of Albert Tooth, please click on the following link: Wingate's Journey Home

77th Brigade-Report by Flight-Lieutenant Tooth RAF

S.A.S.O. 10th June 1943.

Official preamble by the collating Intel Officer

Attached is a short report by F/L Tooth, starting from the date that his party was separated from Brigadier Wingate when crossing the Irrawaddy River on their return journey. The main point of interest is the extraordinary feat of travelling from the Irrawaddy to the Chindwin, with a party which consisted originally of only eleven men with no weapons, having lost their rifles and other equipment when the boat carrying them capsized in the Irrawaddy.

I do not think it is necessary to give this report the same circulation as F/L R. Thompson's, as it is of no particular interest as regards co-operation between Long Range Penetration Groups and the RAF. In the appendix F/L Tooth has given his reasons why he considers it is not necessary to attach operational aircrews to Infantry Brigades in the future.

Document Serial No. 1507

File reference-100/27/Q

A.I. Registry GHQ.

Report of F/Lt. 88469 Albert Tooth, covering the period 9th April to 30th April 1943, whilst in Burma with 77 Indian Infantry Brigade.

April 9th: The dispersal group of 43 men led by the Brigadier commenced to cross the Irrawaddy. After 32 men had crossed, gun fire was heard on the east bank and no boat returned for the remaining party which consisted of:

Squadron Leader Longmore

F/Lt. Tooth

Lt. Rose and 4 Gurkhas from the Brigade Defence Platoon.

F/Sgt. Fidler

L/Cpl. Hutchins

L/Cpl. Dermody

Pte. Weston

At 18.30 hours one boat returned and the party crossed to the west bank, where no trace was found of the Brigadier or his party. We stayed here for the night.

April 10th: In the afternoon we marched west and reached the other side of the island at 2200 hours. A boat was found and the party set off across the wide channel. When 50 yards from the opposite bank, a strong current was met and the boat, which leaked badly, sank when about 30 yards from the bank. S/Ldr. Longmore and three of the Gurkhas were last seen standing on the boat, which by then was three or four feet under the water and drifting downstream. Pte. Weston and the other Gurkha were clinging to a piece of driftwood 20 yards from the bank and were rescued several hours later, when the water level had dropped down. A search was made for Longmore and the other men that evening and again the following morning, but with no result. All our rifles and equipment had been lost when the boat capsized in the river.

April 11th: Villagers met us and led us across another channel to the village of Nyaungbintha. Here we bought food and other provisions and learned that the Japanese forces had moved north. We set off west towards the hills continuing by moonlight.

April 12th: Continued our march west towards the main ridge.

April 13th: Crossed over the range. Midday halt. Left again at 1700 hours, followed a river until we crossed a dry belt of bamboo scrub that night.

April 14th: Halted at 1400 hours. No water. Travelled through paddy fields. Began marching again at 1900 hours. Lt. Rose and myself entered a village looking for water. Villagers unfriendly and forced us to continue marching without fresh water supplies.

April 15th: Found water at 0600 hours. Halted for the day near some paddy fields. Resumed march at 1900 hours, crossed the railway 3 miles south of Kawlin.

April 16th: Slept until 0500 hours, then climbed over the next range. Travelled down a chaung, then crossed a new road at dusk. Jungle very difficult in this area, avoided villages. Halted at 2130 hours.

April 17th: Left at 0700 hours, climbed over hills and down a large stream. Met four native women who fled from us. Entered the village and bought food. According to these villages, Pinlebu was to the north-west. A new road used by Japanese vehicles was in the vicinity, so we moved two miles away from the village to bivouac.

April 18th: Set off across low hills with open forest and strips of paddy. Villagers here tended to ignore us. Covered more distance through thick bamboo.

April 19th: Crossed next range of hills at 0600 hours. Forded the Mu River at 2200 hours and reached fairly low bamboo covered hills running north to south.

April 20th: Halt on hilltop at 0230 hours. Continued along the ridge at 0730 hours. Followed small river changing direction from west to north-west.

April 21st: Continued west through thick jungle. Passed over another new motor-road.

April 22nd: Continued west, sighted a very high range which we believed to be the Chin Hills.

April 23/24th: Travelled along a stream, this was probably the Namuto Chaung. Camped close to a village. Villagers told us the stream would take us to Paungbyin.

April 25th: Stream turned away north so we left it and continued to march west over difficult bamboo covered hills. Followed a dry chaung south-west for about 3 miles. Turned back west over a high peak and down into a forest. Found good water and settled for the night.

April 26th: Moved across dry and open forest. Reached the village of Kongyi on the Mu River. Here the priest, who seemed quite friendly gave us some Double Ace cigarettes. The villagers told us that there were no Japs between Kongyi and the Chindwin. We continued along the track for another three miles and walked straight into a Japanese guard post. Fortunately, the officer in charge was as surprised to see us, as we were them and I was able to disperse off the track and into the jungle without much trouble.

At this point, Pte. Weston and the Gurkha were some fifty yards behind and did not follow us into the jungle. We continued on north-east, then turned in a semi-circle, re-crossing the track about 800 yards south of the Jap post. We then hid in a swamp for the remainder of the afternoon. At dusk we rejoined the track and marched on westward. Weston did not catch up with us.

After an hour or so we halted and dispersed once more off the track and into the jungle for a rest. Whilst here a party of Japs led by a tracker with a torch came along the track. Where we had dispersed off the track the Japs stopped for a while but eventually moved away. We decided to move further into the thick-set bamboo. They returned once more to the same place and then apparently gave up the search for us. It seemed to us that the Japanese knew we had no weapons and assumed that the priests at Kongyi had informed on us to the enemy. We continued into the hills to the north.

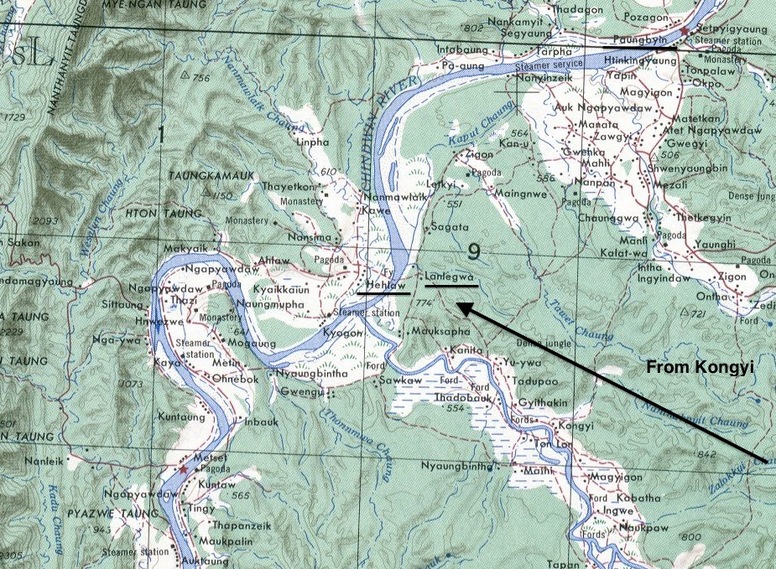

April 27th: Marched west down a river bed avoiding the village at the foot of the hills and reached the Chindwin at 1030 hours. At 1400 hours we moved along the bank towards the village Lanlegwa, but ran into another Jap post. There was great deal of wild firing from machine gun and by discharger cup. Lt. Rose ran across their line of fire and was not heard of again. Although there was heavy firing for sometime after, we were not followed. We were about half a mile further north along the river bank and in good cover. That night we found a raft but on testing it, it sank.

April 28th: I decided to try further north, but on finding no water in this area we returned to the river bank. Here we met a villager who brought us food. We slept in the paddy field near his hut as he seemed trustworthy and he promised us more food in the morning.

April 29th: The villager realised by our signs that we wanted to cross the river. That evening he brought us bamboo with which we built a small raft. We placed on the raft the member of our party who could not swim and the rest of us swam behind the raft, pushing it to the other side. The villager had told us that there were British troops in Hehlaw.

April 30th: During the morning we met a Company of the 3/5th Gurkha Rifles at Hehlaw. They guided us to their main camp and the following day we reached Tamu. The final party consisted of myself, F/Sgt. Fidler, L/Cpl. Hutchins and L/Cpl. Dermody.

77th Brigade-Report by Flight-Lieutenant Tooth RAF

S.A.S.O. 10th June 1943.

Official preamble by the collating Intel Officer

Attached is a short report by F/L Tooth, starting from the date that his party was separated from Brigadier Wingate when crossing the Irrawaddy River on their return journey. The main point of interest is the extraordinary feat of travelling from the Irrawaddy to the Chindwin, with a party which consisted originally of only eleven men with no weapons, having lost their rifles and other equipment when the boat carrying them capsized in the Irrawaddy.

I do not think it is necessary to give this report the same circulation as F/L R. Thompson's, as it is of no particular interest as regards co-operation between Long Range Penetration Groups and the RAF. In the appendix F/L Tooth has given his reasons why he considers it is not necessary to attach operational aircrews to Infantry Brigades in the future.

Document Serial No. 1507

File reference-100/27/Q

A.I. Registry GHQ.

Report of F/Lt. 88469 Albert Tooth, covering the period 9th April to 30th April 1943, whilst in Burma with 77 Indian Infantry Brigade.

April 9th: The dispersal group of 43 men led by the Brigadier commenced to cross the Irrawaddy. After 32 men had crossed, gun fire was heard on the east bank and no boat returned for the remaining party which consisted of:

Squadron Leader Longmore

F/Lt. Tooth

Lt. Rose and 4 Gurkhas from the Brigade Defence Platoon.

F/Sgt. Fidler

L/Cpl. Hutchins

L/Cpl. Dermody

Pte. Weston

At 18.30 hours one boat returned and the party crossed to the west bank, where no trace was found of the Brigadier or his party. We stayed here for the night.

April 10th: In the afternoon we marched west and reached the other side of the island at 2200 hours. A boat was found and the party set off across the wide channel. When 50 yards from the opposite bank, a strong current was met and the boat, which leaked badly, sank when about 30 yards from the bank. S/Ldr. Longmore and three of the Gurkhas were last seen standing on the boat, which by then was three or four feet under the water and drifting downstream. Pte. Weston and the other Gurkha were clinging to a piece of driftwood 20 yards from the bank and were rescued several hours later, when the water level had dropped down. A search was made for Longmore and the other men that evening and again the following morning, but with no result. All our rifles and equipment had been lost when the boat capsized in the river.

April 11th: Villagers met us and led us across another channel to the village of Nyaungbintha. Here we bought food and other provisions and learned that the Japanese forces had moved north. We set off west towards the hills continuing by moonlight.

April 12th: Continued our march west towards the main ridge.

April 13th: Crossed over the range. Midday halt. Left again at 1700 hours, followed a river until we crossed a dry belt of bamboo scrub that night.

April 14th: Halted at 1400 hours. No water. Travelled through paddy fields. Began marching again at 1900 hours. Lt. Rose and myself entered a village looking for water. Villagers unfriendly and forced us to continue marching without fresh water supplies.

April 15th: Found water at 0600 hours. Halted for the day near some paddy fields. Resumed march at 1900 hours, crossed the railway 3 miles south of Kawlin.

April 16th: Slept until 0500 hours, then climbed over the next range. Travelled down a chaung, then crossed a new road at dusk. Jungle very difficult in this area, avoided villages. Halted at 2130 hours.

April 17th: Left at 0700 hours, climbed over hills and down a large stream. Met four native women who fled from us. Entered the village and bought food. According to these villages, Pinlebu was to the north-west. A new road used by Japanese vehicles was in the vicinity, so we moved two miles away from the village to bivouac.

April 18th: Set off across low hills with open forest and strips of paddy. Villagers here tended to ignore us. Covered more distance through thick bamboo.

April 19th: Crossed next range of hills at 0600 hours. Forded the Mu River at 2200 hours and reached fairly low bamboo covered hills running north to south.

April 20th: Halt on hilltop at 0230 hours. Continued along the ridge at 0730 hours. Followed small river changing direction from west to north-west.

April 21st: Continued west through thick jungle. Passed over another new motor-road.

April 22nd: Continued west, sighted a very high range which we believed to be the Chin Hills.

April 23/24th: Travelled along a stream, this was probably the Namuto Chaung. Camped close to a village. Villagers told us the stream would take us to Paungbyin.

April 25th: Stream turned away north so we left it and continued to march west over difficult bamboo covered hills. Followed a dry chaung south-west for about 3 miles. Turned back west over a high peak and down into a forest. Found good water and settled for the night.

April 26th: Moved across dry and open forest. Reached the village of Kongyi on the Mu River. Here the priest, who seemed quite friendly gave us some Double Ace cigarettes. The villagers told us that there were no Japs between Kongyi and the Chindwin. We continued along the track for another three miles and walked straight into a Japanese guard post. Fortunately, the officer in charge was as surprised to see us, as we were them and I was able to disperse off the track and into the jungle without much trouble.

At this point, Pte. Weston and the Gurkha were some fifty yards behind and did not follow us into the jungle. We continued on north-east, then turned in a semi-circle, re-crossing the track about 800 yards south of the Jap post. We then hid in a swamp for the remainder of the afternoon. At dusk we rejoined the track and marched on westward. Weston did not catch up with us.

After an hour or so we halted and dispersed once more off the track and into the jungle for a rest. Whilst here a party of Japs led by a tracker with a torch came along the track. Where we had dispersed off the track the Japs stopped for a while but eventually moved away. We decided to move further into the thick-set bamboo. They returned once more to the same place and then apparently gave up the search for us. It seemed to us that the Japanese knew we had no weapons and assumed that the priests at Kongyi had informed on us to the enemy. We continued into the hills to the north.

April 27th: Marched west down a river bed avoiding the village at the foot of the hills and reached the Chindwin at 1030 hours. At 1400 hours we moved along the bank towards the village Lanlegwa, but ran into another Jap post. There was great deal of wild firing from machine gun and by discharger cup. Lt. Rose ran across their line of fire and was not heard of again. Although there was heavy firing for sometime after, we were not followed. We were about half a mile further north along the river bank and in good cover. That night we found a raft but on testing it, it sank.

April 28th: I decided to try further north, but on finding no water in this area we returned to the river bank. Here we met a villager who brought us food. We slept in the paddy field near his hut as he seemed trustworthy and he promised us more food in the morning.

April 29th: The villager realised by our signs that we wanted to cross the river. That evening he brought us bamboo with which we built a small raft. We placed on the raft the member of our party who could not swim and the rest of us swam behind the raft, pushing it to the other side. The villager had told us that there were British troops in Hehlaw.

April 30th: During the morning we met a Company of the 3/5th Gurkha Rifles at Hehlaw. They guided us to their main camp and the following day we reached Tamu. The final party consisted of myself, F/Sgt. Fidler, L/Cpl. Hutchins and L/Cpl. Dermody.

On debrief, F/Lt. Tooth submitted the following observations about the role of the RAF on Operation Longcloth. It is clear that he believed that the use of RAF personnel in Chindit columns was unnecessary and that with training, Army officers could carry out Air Liaison duties.

The objects of the RAF personnel, apart from Wireless communication with air base were:

1. The selection of suitable areas for taking supply drops and duties in connection with undertaking such drops on the day.

2. To give advice on bombing, including the suitability of targets and the type of bombs to be used.

3. To obtain information with regard to Japanese aircraft and aerodrome organisation and if possible to fly back to India any serviceable aircraft from any enemy airfield captured.

With regard to Point 1, a series of lectures would enable any Army Officer to be able to perform these duties. On several occasions during the operation, this was exactly what occurred, especially when columns were split and RAF personnel were not available. The actual percentage of supplies lost or damaged was less than 5%. In my view, Point 2 could also be covered by lectures.

It would not be possible to obtain information in regards to Point 3, unless an airfield was actually captured, in which case pilots could be flown in, or dropped by parachute. The possibility of personnel spying on an enemy airfield from close quarters, in my opinion is of little value and can be dismissed as impracticable. I submit therefore, that it should be unnecessary in future operations of this nature to attach operational aircrews to Infantry Brigades.

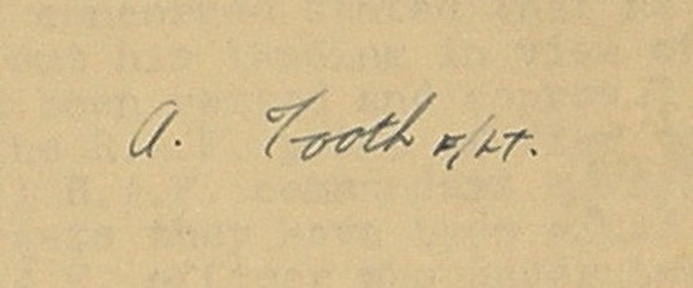

Signed A. Tooth.

The objects of the RAF personnel, apart from Wireless communication with air base were:

1. The selection of suitable areas for taking supply drops and duties in connection with undertaking such drops on the day.

2. To give advice on bombing, including the suitability of targets and the type of bombs to be used.

3. To obtain information with regard to Japanese aircraft and aerodrome organisation and if possible to fly back to India any serviceable aircraft from any enemy airfield captured.

With regard to Point 1, a series of lectures would enable any Army Officer to be able to perform these duties. On several occasions during the operation, this was exactly what occurred, especially when columns were split and RAF personnel were not available. The actual percentage of supplies lost or damaged was less than 5%. In my view, Point 2 could also be covered by lectures.

It would not be possible to obtain information in regards to Point 3, unless an airfield was actually captured, in which case pilots could be flown in, or dropped by parachute. The possibility of personnel spying on an enemy airfield from close quarters, in my opinion is of little value and can be dismissed as impracticable. I submit therefore, that it should be unnecessary in future operations of this nature to attach operational aircrews to Infantry Brigades.

Signed A. Tooth.

Of course, Wingate and India Command took no head of his advice and expanded the role of RAF Air Liaison within Chindit columns for the second Chindit expedition in 1944. However, Albert did not volunteer for a second time. Shown below are some photographs in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

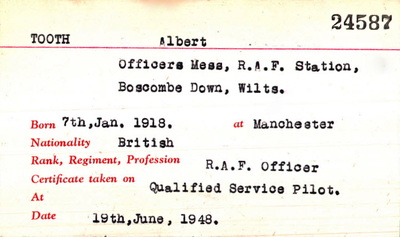

Albert Tooth remained in the RAF after the war and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in the summer of 1945, this was Gazetted in August that same year. He took membership of the Royal Aero Club of Great Britain in June 1948, whilst stationed as a test pilot at Boscombe Down in Wiltshire. Tragically, just a few days later on the 2nd July, Squadron Leader Albert Tooth was killed in an air accident when the Avro Lincoln Bomber he was flying crashed near the village of Wylye, located some nine miles north-west of Salisbury.

Squadron Leader Tooth and his crew; Flight Lieutenant A. G. Bradfield, Flight Officer G.W. Williams and Test Officer P.W. Howes, were engaged in high altitude handling trials of the aircraft, following the fitting of new radar equipment. Whilst testing behaviour at low speeds with the No. 1 propeller feathered, the aircraft entered a left hand spin and with insufficient height available to recover, the plane crashed into a nearby hill, killing all four men. I have been unable to locate a final resting place for Albert Tooth, although I have discovered that Flight Lieutenant Bradfield was buried at Durrington Cemetery, located a few miles north-east of Stonehenge.

To conclude this narrative, shown below is another Gallery of images in relation to Albert Tooth and his postwar experiences. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Squadron Leader Tooth and his crew; Flight Lieutenant A. G. Bradfield, Flight Officer G.W. Williams and Test Officer P.W. Howes, were engaged in high altitude handling trials of the aircraft, following the fitting of new radar equipment. Whilst testing behaviour at low speeds with the No. 1 propeller feathered, the aircraft entered a left hand spin and with insufficient height available to recover, the plane crashed into a nearby hill, killing all four men. I have been unable to locate a final resting place for Albert Tooth, although I have discovered that Flight Lieutenant Bradfield was buried at Durrington Cemetery, located a few miles north-east of Stonehenge.

To conclude this narrative, shown below is another Gallery of images in relation to Albert Tooth and his postwar experiences. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 15/10/2016.

Incredibly, less than one month after publishing the story of Squadron Leader Albert Tooth, I was contacted by his eldest daughter Pauline:

My father, Albert Tooth, sadly died a few days after my third birthday, my younger sister Patricia was not quite two. I have read your article with huge interest and indeed have some of the photos you have shown. My son directed me to view the website on-line, as of course he is interested in the life of his grandfather. My father was born on the 7th January 1918. I believe his family came from Market Drayton initially. They moved to Manchester where he attended Hulme Grammar School. He was interested in History and intended to go to University, but instead joined the RAF and became a pilot. I still have his school certificates.

He had two older sisters who loved him dearly and before she died, my Aunt gave me some photographs and newspaper excerpts she had kept over the years. His main hobby was mountaineering, but he was also a good swimmer and enjoyed tennis. My mother kept many of his wartime photographs, one of which is of him with his Spitfire, and of course flying was always his true vocation.

When he came out of the Burmese jungle he was quite ill, as I am sure they all were, those who survived. He was in hospital for some time and this is where he met my mother, Rebecca Jane Johnston who nursed him. They married in 1943 and I was born in 1945 in India. In December 1945 we came back to the United Kingdom by boat and my father flew home. We lived in Chorlton-cum-Hardy and this is where my sister was born. My Aunt told me that when he was demobbed he took up a job with the Insurance Company where she worked, but he soon applied to return to the RAF where life was more interesting. He became a test pilot and was based at Boscombe Down.

I have some of his letters to my mother, and one of them was written on 1st July 1948, the day before he died. In the letter he apologised for not writing sooner as he had been away for lunch at Vickers and when he got back at 2.30 pm, he had to go off in a Lincoln aircraft and did not come down until after seven. He mentioned a holiday they were intending to go on and asked my mother if she would buy two of those lilo balls for the children. He also mentioned a house they had viewed costing £3,000, but thought the price was rather high and that Andover would be a better place to live, as he had seen a large swimming pool and tennis club when he had flown over that afternoon.

I have his Chindit cloth badge and his medal ribbons. I think his medals were the DFC, 1939/45 Star, Air Crew Europe Star, Burma Star, Defence Medal and the 1939/45 War Medal. I have a book entitled, The Campaign in Burma, which you probably already have, and an Illustrated magazine dated July 10th 1943, containing eight pages entitled, Twenty Casualties to Fly Out. Please let me know if you would like me to send these. The latter is a picture story by William Vandivert, the Life magazine cameraman, who was aboard the plane which landed in Japanese occupied territory to pick up the wounded from one of the famous Wingate columns.

I have attached some of the photographs I mentioned before; sadly they are very old and small, but I hope will be sufficient for you to use on the website. One is of my father with his beloved Spitfire, which has the Skull & Crossbones on the fuselage.

Best wishes Pauline.

Seen in the Gallery below are some of Pauline's photographs. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Pauline for her invaluable contribution to the story of her father, Albert Tooth.

Incredibly, less than one month after publishing the story of Squadron Leader Albert Tooth, I was contacted by his eldest daughter Pauline:

My father, Albert Tooth, sadly died a few days after my third birthday, my younger sister Patricia was not quite two. I have read your article with huge interest and indeed have some of the photos you have shown. My son directed me to view the website on-line, as of course he is interested in the life of his grandfather. My father was born on the 7th January 1918. I believe his family came from Market Drayton initially. They moved to Manchester where he attended Hulme Grammar School. He was interested in History and intended to go to University, but instead joined the RAF and became a pilot. I still have his school certificates.

He had two older sisters who loved him dearly and before she died, my Aunt gave me some photographs and newspaper excerpts she had kept over the years. His main hobby was mountaineering, but he was also a good swimmer and enjoyed tennis. My mother kept many of his wartime photographs, one of which is of him with his Spitfire, and of course flying was always his true vocation.

When he came out of the Burmese jungle he was quite ill, as I am sure they all were, those who survived. He was in hospital for some time and this is where he met my mother, Rebecca Jane Johnston who nursed him. They married in 1943 and I was born in 1945 in India. In December 1945 we came back to the United Kingdom by boat and my father flew home. We lived in Chorlton-cum-Hardy and this is where my sister was born. My Aunt told me that when he was demobbed he took up a job with the Insurance Company where she worked, but he soon applied to return to the RAF where life was more interesting. He became a test pilot and was based at Boscombe Down.

I have some of his letters to my mother, and one of them was written on 1st July 1948, the day before he died. In the letter he apologised for not writing sooner as he had been away for lunch at Vickers and when he got back at 2.30 pm, he had to go off in a Lincoln aircraft and did not come down until after seven. He mentioned a holiday they were intending to go on and asked my mother if she would buy two of those lilo balls for the children. He also mentioned a house they had viewed costing £3,000, but thought the price was rather high and that Andover would be a better place to live, as he had seen a large swimming pool and tennis club when he had flown over that afternoon.

I have his Chindit cloth badge and his medal ribbons. I think his medals were the DFC, 1939/45 Star, Air Crew Europe Star, Burma Star, Defence Medal and the 1939/45 War Medal. I have a book entitled, The Campaign in Burma, which you probably already have, and an Illustrated magazine dated July 10th 1943, containing eight pages entitled, Twenty Casualties to Fly Out. Please let me know if you would like me to send these. The latter is a picture story by William Vandivert, the Life magazine cameraman, who was aboard the plane which landed in Japanese occupied territory to pick up the wounded from one of the famous Wingate columns.

I have attached some of the photographs I mentioned before; sadly they are very old and small, but I hope will be sufficient for you to use on the website. One is of my father with his beloved Spitfire, which has the Skull & Crossbones on the fuselage.

Best wishes Pauline.

Seen in the Gallery below are some of Pauline's photographs. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Pauline for her invaluable contribution to the story of her father, Albert Tooth.

Update 07/11/2016.

Recently, I was pleased to receive some more information from Albert Tooth's daughter, Pauline.

Hello Steve

I have been trying to read some of the diaries belonging to my father and mother. These diaries are very tiny, as they were in those days, and I found them difficult to read, but from them I have ascertained that my mother met my father in 1942 and in that year he was hospitalised suffering from dysentery and anaemia, the hospital being in Lebong. He notes on the 25th September 1942, that he was out of hospital and feeling better and went on leave to Darjeeling on the 26th. They got engaged on 1st December 1942 and on 27th he was discharged from hospital and deemed as fit for flying.

In my mother’s diary for 1943, there is an entry for the 11th February stating “Albert went away,” and on the 11th May another entry that simply read, “three months away." This was obviously the period he was in Burma. On the 27th June 1943, she writes, “Albert to Calcutta to work,” but the rest of the writing is not easily decipherable. Then there were a flurry of letters, including two in one day on the 14th July. In August 1943 my mother left Lebong and travelled first to Calcutta and then to Madras, where she met my father on the 13th November. They were married in Calcutta, at St Paul’s Cathedral on 14th December.

Reading these diaries has been very interesting; I had always understood that my mother nursed my father when he came out of Burma in 1943 and that was how they met, but this was obviously not the case and they must have met when he was hospitalised in 1942.

All the very best

Pauline.

Seen below is an image of St. Paul's Cathedral in Calcutta. This image is circa 1880 and I am not sure if by 1943 the building still retained the prominent spire seen in this photograph.

Recently, I was pleased to receive some more information from Albert Tooth's daughter, Pauline.

Hello Steve

I have been trying to read some of the diaries belonging to my father and mother. These diaries are very tiny, as they were in those days, and I found them difficult to read, but from them I have ascertained that my mother met my father in 1942 and in that year he was hospitalised suffering from dysentery and anaemia, the hospital being in Lebong. He notes on the 25th September 1942, that he was out of hospital and feeling better and went on leave to Darjeeling on the 26th. They got engaged on 1st December 1942 and on 27th he was discharged from hospital and deemed as fit for flying.

In my mother’s diary for 1943, there is an entry for the 11th February stating “Albert went away,” and on the 11th May another entry that simply read, “three months away." This was obviously the period he was in Burma. On the 27th June 1943, she writes, “Albert to Calcutta to work,” but the rest of the writing is not easily decipherable. Then there were a flurry of letters, including two in one day on the 14th July. In August 1943 my mother left Lebong and travelled first to Calcutta and then to Madras, where she met my father on the 13th November. They were married in Calcutta, at St Paul’s Cathedral on 14th December.

Reading these diaries has been very interesting; I had always understood that my mother nursed my father when he came out of Burma in 1943 and that was how they met, but this was obviously not the case and they must have met when he was hospitalised in 1942.

All the very best

Pauline.

Seen below is an image of St. Paul's Cathedral in Calcutta. This image is circa 1880 and I am not sure if by 1943 the building still retained the prominent spire seen in this photograph.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, August 2016.