Lieutenant Lewis William Rose

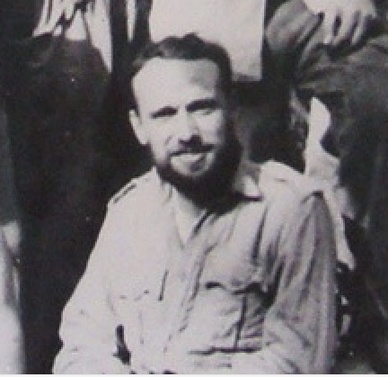

Lewis Rose in Burma, April 1943.

Lewis Rose in Burma, April 1943.

Lewis William Rose was a member of Brigadier Wingate's own Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. He commanded the Gurkha Defence Platoon tasked with protecting the Brigadier should any enemy soldiers come near.

Born on the 18th August 1910, the son of Edward and Sophie Rose, Lewis, sometimes known as Lionel in records and books mentioning his Chindit exploits had experienced the horror of the Dunkirk evacuation in 1940 whilst serving with the Sherwood Foresters. He had then been posted to India, where he commanded first within the ranks of 3/10 Gurkha Rifles, before being posted to the 3/2 Gurkhas in 1942 and joining Chindit training at Patharia.

NB. From more recent information discovered about the Army service of Lewis Rose, it is now known that he never trained with the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at Saugor, but was seconded by Wingate into the Brigade at the Chindwin River crossing. For more details, please read the update 'Unsung Hero' featured towards the foot of this page.

There seems to be a strong Jewish connection surrounding Lewis, firstly the reference to him often being called Lionel, secondly his home address in Golders Green in London and finally his presence in Martin Sugarman's book about the Jewish military contribution in WW2, 'Fighting Back'.

Lewis Rose married Rebecca Isaacs in the summer of 1935 and the couple had a daughter named Hilary. This is all I really know about his life before he served with the first Chindit expedition in 1943.

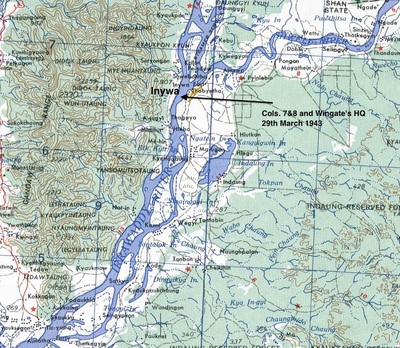

By early April 1943, Wingate and his own HQ were planning their exit from Burma after six weeks of raiding behind enemy lines. Lieutenant Rose was with his commander, close to the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River near the Burmese town of Inywa. The Chindit columns had attempted to cross the river at this point, but had been confronted by a Japanese patrol on the western banks and the crossing was abandoned. Columns 7 and 8 moved away from the Irrawaddy, separately, but both heading roughly south-east. Wingate took his men deep in to the surrounding scrub-jungle, where they would wait patiently for several days until the heat had died down and the enemy had left the area.

The story is now taken up by Signalman Eric Hutchins from the pages of the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', by Phil Chinnery.

On 7 April, Wingate made a second attempt at crossing the Irrawaddy, 25 miles south of Inywa. For two days they searched the bank for boats, but Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles could only find one boat and it would take but seven people at a time. They began crossing late in the afternoon, but when half of the party was over automatic fire was heard from the north and the native boatman made off with the boat, leaving the other half of the party stranded on the east bank.

Those who successfully made it across the river included the Brigadier, Majors Anderson and Jefferies, Captains Aung Thin and Katju, and twenty-four Other Ranks. They were not, however, on the west bank of the river yet. They were, in fact, on an island and they immediately moved on towards Nyaungbintha where they found a large boat and crossed over at dusk. They moved on for a couple of miles and lay up for the night. The mosquitoes were intolerable and they got little sleep.

Signaller Eric Hutchins was in the last party waiting to cross the river, together with Squadron Leader Longmore, Flight Lieutenant Tooth, Flight Sergeant Fidler, Lieutenant Rose of the Gurkhas, Private Dermody and Private Weston of the King's. Eric remembered:

The first six boat parties made their way safely to the opposite bank. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the opposite bank we could find no trace of the others. Wingate's excuse when we met him later, was he 'thought' we had been captured by the Japanese, whereas he had abandoned us without maps or any means of finding our way back to our own lines. Such is my regard for a commander who later became world famous.

So we set out west only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Our problems now really began, because we could not find a suitable boat. Eventually we found a boat that had seen better days and decided to take a chance crossing at night, using our rifles as oars. Of course the inevitable happened and the boat capsized.

I and others swam to the west shore, where we had to rescue two of our party who were clutching on to a floating plant because they could not swim. At light of day we found that Squadron Leader Longmore was missing. Later at the end of the war I found out that he had remained clutching the boat and floated down river and was eventually captured. We found we were on another island and right opposite a very large village and most of the inhabitants walked across the shallow water to the island, presumably out of curiosity.

We had lost everything when the boat capsized and had no arms to defend ourselves, except that I still had a hand grenade. We went with the villagers and enjoyed a meal of rice and obtained two sacks of rice, cooking pans, a flint stone to make a fire, salt and juggery, the latter unrefined sugar.

Suddenly there was a commotion in the village and the locals started to disperse, which was a signal to us that the Japs had arrived. We made a quick retreat and proceeded to climb the hills behind the village and make our way westwards. Our progress after that was mainly at night, avoiding paths and villages. I remember the beautiful clear moonlit nights with the stars to guide us. I often look for a constellation set at dead 270 degrees which we used as our direction arrow as we kept walking westwards.

Daytime was spent trying to sleep in the intense heat with no water, setting out at dusk to find water and cook a meal. I was suffering severely from dysentery, but somehow raised the strength to carry on. As we neared the Chindwin we found a small chaung in which were some pools of water containing fish. We caught one by swimming under water, but then became greedy and thought if we threw my grenade into the water we could have a real feast. This was not to be because the grenade failed to explode as I had forgotten to prime it.

On seeing the river valley of the Chindwin we now became over-confident and started to abandon our policy of avoiding footpaths. On rounding a bend we ran into a Japanese sentry guarding the path. We immediately plunged into the jungle to our left, but Weston was captured because he was too weak to react quickly. We were forced to stand in a marsh for thirty-six hours while the Japs set fire to it to try to draw us out. Meanwhile we could hear the screams of Weston as they slowly tortured him to death with their bayonets.

On the second night we came out of the marsh only to walk straight through the Jap occupied village. We walked on down the path leading to the Chindwin and then, practising the usual dispersal drill on leaving a path, hid in the jungle nearby. Within fifteen minutes a party of Japs came down the track, following our footprints by torch light. Fortunately for us they hesitated where our footprints finished and then carried on. This was our cue and we retreated deeper into the jungle.

Within half an hour they were back searching the spot we had left. We were now under real pressure and headed for the Chindwin, but could not find a boat to cross. We were walking along the path on the river bank and came to a small clearing with Lieutenant Rose leading. He suddenly turned round and yelled Japs' and in the sudden rush to retreat I fell over. I scrambled to my feet, leaving behind the rice sack I was carrying. The others had a good fifty yards' start on me and machine gun bullets were whizzing all around. I think I broke the world record for 200 yards and reached the jungle on the opposite side of the clearing before the others.

Here we lost Lieutenant Rose and I heard after the war he was later captured and also survived the prison camp. We decided to regain the hills and walk northwards hoping there would be fewer Japs to encounter in that direction. We came upon a hut in the middle of a paddy field and found a native sitting inside. He immediately beckoned us to lie down in the paddy and pointed to a road about fifty yards away where Jap lorries were moving. He indicated to follow him crawling on our bellies to a small copse, it was here that our miracle occurred.

He brought us food twice a day for three days while we got our strength back. He could not get us a boat but when we drew bamboo poles he understood and on each night visit he brought two bamboo poles. Finally we had enough to make a raft and took them down to the river at the dead of night and our saviour tied them together. We had no money and could not reward him, but gave him a note saying how he had helped us and that he should be rewarded by the British if he produced the document.

This man, a complete stranger, possibly a Buddhist, displayed all the ethics of a Good Samaritan and has remained in my deepest thoughts all my life. That day in 1943 on the banks of the Chindwin I learned to believe in miracles.

I was the only strong swimmer and pushed the raft from the rear. Some of the other survivors were too weak to swim and had to be hauled back on the raft. Eventually we reached the other side and rested for the night. In the morning we walked into the nearest village which was occupied by Gurkhas.

Wingate was my hero before the campaign, but after his deliberate abandonment on the east bank of the Irrawaddy I know he only considered his own safety and not others. He would deliberately abandon anyone whom he considered to be a handicap. This was proved later when our signals officer, Ken Spurlock, who was in Wingate's boat party, was abandoned in a village not far from the Chindwin because he was weak with dysentery. I was weak with dysentery but my companions never abandoned me.

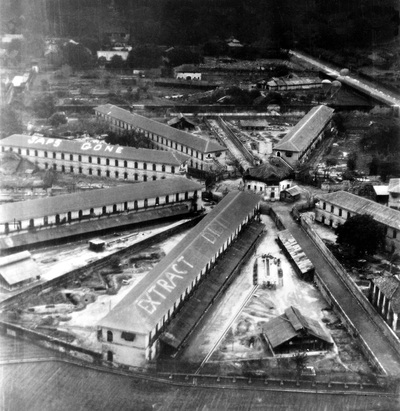

Seen below are two photographs taken during the first week in April 1943, when Wingate's group were hold up in the scrub-jungle close to the Irrawaddy River. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Born on the 18th August 1910, the son of Edward and Sophie Rose, Lewis, sometimes known as Lionel in records and books mentioning his Chindit exploits had experienced the horror of the Dunkirk evacuation in 1940 whilst serving with the Sherwood Foresters. He had then been posted to India, where he commanded first within the ranks of 3/10 Gurkha Rifles, before being posted to the 3/2 Gurkhas in 1942 and joining Chindit training at Patharia.

NB. From more recent information discovered about the Army service of Lewis Rose, it is now known that he never trained with the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at Saugor, but was seconded by Wingate into the Brigade at the Chindwin River crossing. For more details, please read the update 'Unsung Hero' featured towards the foot of this page.

There seems to be a strong Jewish connection surrounding Lewis, firstly the reference to him often being called Lionel, secondly his home address in Golders Green in London and finally his presence in Martin Sugarman's book about the Jewish military contribution in WW2, 'Fighting Back'.

Lewis Rose married Rebecca Isaacs in the summer of 1935 and the couple had a daughter named Hilary. This is all I really know about his life before he served with the first Chindit expedition in 1943.

By early April 1943, Wingate and his own HQ were planning their exit from Burma after six weeks of raiding behind enemy lines. Lieutenant Rose was with his commander, close to the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River near the Burmese town of Inywa. The Chindit columns had attempted to cross the river at this point, but had been confronted by a Japanese patrol on the western banks and the crossing was abandoned. Columns 7 and 8 moved away from the Irrawaddy, separately, but both heading roughly south-east. Wingate took his men deep in to the surrounding scrub-jungle, where they would wait patiently for several days until the heat had died down and the enemy had left the area.

The story is now taken up by Signalman Eric Hutchins from the pages of the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', by Phil Chinnery.

On 7 April, Wingate made a second attempt at crossing the Irrawaddy, 25 miles south of Inywa. For two days they searched the bank for boats, but Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles could only find one boat and it would take but seven people at a time. They began crossing late in the afternoon, but when half of the party was over automatic fire was heard from the north and the native boatman made off with the boat, leaving the other half of the party stranded on the east bank.

Those who successfully made it across the river included the Brigadier, Majors Anderson and Jefferies, Captains Aung Thin and Katju, and twenty-four Other Ranks. They were not, however, on the west bank of the river yet. They were, in fact, on an island and they immediately moved on towards Nyaungbintha where they found a large boat and crossed over at dusk. They moved on for a couple of miles and lay up for the night. The mosquitoes were intolerable and they got little sleep.

Signaller Eric Hutchins was in the last party waiting to cross the river, together with Squadron Leader Longmore, Flight Lieutenant Tooth, Flight Sergeant Fidler, Lieutenant Rose of the Gurkhas, Private Dermody and Private Weston of the King's. Eric remembered:

The first six boat parties made their way safely to the opposite bank. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the opposite bank we could find no trace of the others. Wingate's excuse when we met him later, was he 'thought' we had been captured by the Japanese, whereas he had abandoned us without maps or any means of finding our way back to our own lines. Such is my regard for a commander who later became world famous.

So we set out west only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Our problems now really began, because we could not find a suitable boat. Eventually we found a boat that had seen better days and decided to take a chance crossing at night, using our rifles as oars. Of course the inevitable happened and the boat capsized.

I and others swam to the west shore, where we had to rescue two of our party who were clutching on to a floating plant because they could not swim. At light of day we found that Squadron Leader Longmore was missing. Later at the end of the war I found out that he had remained clutching the boat and floated down river and was eventually captured. We found we were on another island and right opposite a very large village and most of the inhabitants walked across the shallow water to the island, presumably out of curiosity.

We had lost everything when the boat capsized and had no arms to defend ourselves, except that I still had a hand grenade. We went with the villagers and enjoyed a meal of rice and obtained two sacks of rice, cooking pans, a flint stone to make a fire, salt and juggery, the latter unrefined sugar.

Suddenly there was a commotion in the village and the locals started to disperse, which was a signal to us that the Japs had arrived. We made a quick retreat and proceeded to climb the hills behind the village and make our way westwards. Our progress after that was mainly at night, avoiding paths and villages. I remember the beautiful clear moonlit nights with the stars to guide us. I often look for a constellation set at dead 270 degrees which we used as our direction arrow as we kept walking westwards.

Daytime was spent trying to sleep in the intense heat with no water, setting out at dusk to find water and cook a meal. I was suffering severely from dysentery, but somehow raised the strength to carry on. As we neared the Chindwin we found a small chaung in which were some pools of water containing fish. We caught one by swimming under water, but then became greedy and thought if we threw my grenade into the water we could have a real feast. This was not to be because the grenade failed to explode as I had forgotten to prime it.

On seeing the river valley of the Chindwin we now became over-confident and started to abandon our policy of avoiding footpaths. On rounding a bend we ran into a Japanese sentry guarding the path. We immediately plunged into the jungle to our left, but Weston was captured because he was too weak to react quickly. We were forced to stand in a marsh for thirty-six hours while the Japs set fire to it to try to draw us out. Meanwhile we could hear the screams of Weston as they slowly tortured him to death with their bayonets.

On the second night we came out of the marsh only to walk straight through the Jap occupied village. We walked on down the path leading to the Chindwin and then, practising the usual dispersal drill on leaving a path, hid in the jungle nearby. Within fifteen minutes a party of Japs came down the track, following our footprints by torch light. Fortunately for us they hesitated where our footprints finished and then carried on. This was our cue and we retreated deeper into the jungle.

Within half an hour they were back searching the spot we had left. We were now under real pressure and headed for the Chindwin, but could not find a boat to cross. We were walking along the path on the river bank and came to a small clearing with Lieutenant Rose leading. He suddenly turned round and yelled Japs' and in the sudden rush to retreat I fell over. I scrambled to my feet, leaving behind the rice sack I was carrying. The others had a good fifty yards' start on me and machine gun bullets were whizzing all around. I think I broke the world record for 200 yards and reached the jungle on the opposite side of the clearing before the others.

Here we lost Lieutenant Rose and I heard after the war he was later captured and also survived the prison camp. We decided to regain the hills and walk northwards hoping there would be fewer Japs to encounter in that direction. We came upon a hut in the middle of a paddy field and found a native sitting inside. He immediately beckoned us to lie down in the paddy and pointed to a road about fifty yards away where Jap lorries were moving. He indicated to follow him crawling on our bellies to a small copse, it was here that our miracle occurred.

He brought us food twice a day for three days while we got our strength back. He could not get us a boat but when we drew bamboo poles he understood and on each night visit he brought two bamboo poles. Finally we had enough to make a raft and took them down to the river at the dead of night and our saviour tied them together. We had no money and could not reward him, but gave him a note saying how he had helped us and that he should be rewarded by the British if he produced the document.

This man, a complete stranger, possibly a Buddhist, displayed all the ethics of a Good Samaritan and has remained in my deepest thoughts all my life. That day in 1943 on the banks of the Chindwin I learned to believe in miracles.

I was the only strong swimmer and pushed the raft from the rear. Some of the other survivors were too weak to swim and had to be hauled back on the raft. Eventually we reached the other side and rested for the night. In the morning we walked into the nearest village which was occupied by Gurkhas.

Wingate was my hero before the campaign, but after his deliberate abandonment on the east bank of the Irrawaddy I know he only considered his own safety and not others. He would deliberately abandon anyone whom he considered to be a handicap. This was proved later when our signals officer, Ken Spurlock, who was in Wingate's boat party, was abandoned in a village not far from the Chindwin because he was weak with dysentery. I was weak with dysentery but my companions never abandoned me.

Seen below are two photographs taken during the first week in April 1943, when Wingate's group were hold up in the scrub-jungle close to the Irrawaddy River. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Although given the circumstances, Eric Hutchin's view of Wingate is totally understandable, it is perhaps not totally true to say that the then Brigadier did not care or consider the well-being of his fellow Chindits. From the book 'Fire in the Night' by John Bierman and Colin Smith comes this short passage describing the commander's regret about the fate of Lieutenant Rose:

Wingate was always concerned about the welfare of the men under his command, past and present, as one small incident may illustrate. Lorna (Wingate's wife) had written to say that she had received an enquiry from the wife of one of Wingate's officers who had not returned from the first Chindit expedition.

This was Lieutenant Lionel Rose of the Sherwood Foresters, the Defence Platoon commander of Wingate's Brigade HQ, who had got as far as the Chindwin on the return journey, only to fall into Japanese hands.

"Would you ask someone to get what details there are for this poor woman?" asked Lorna. Wingate wrote back describing Rose as "a splendid boy" who was "instrumental in saving my own life on one occasion."

"I felt very badly about his loss, which was perhaps partly my fault. He was missing from the time he was last seen, about May 1st, on the Chindwin. I fear the worst, though don't say so to Mrs. Rose. If she is in any want now or in the future we must help her. I feel I am responsible to Rose for that. . . . Rose behaved with the greatest courage and unselfishness. He was devoted to his Ghurkas and owes his present absence to that devotion, otherwise he would have come in my boat, as I asked him to do.

Six weeks later, Wingate received "the glad news that certain of my old Brigade Officers are prisoners of war in Burma" and immediately wrote to tell Lorna that "Rose is said to be one of them." He added: "I do not think they are badly treated by all accounts. They get the Japanese rations which are poor for Englishmen, but there does not seem to be any deliberate ill-treatment there at present."

The Japanese rations that Wingate described were those given out at Rangoon Jail, which is where the men captured in 1943 were eventually taken.

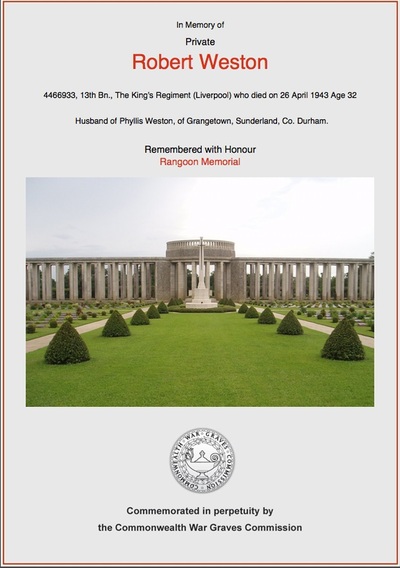

Shown below are some of the men from the dispersal group mentioned by Signalman Eric Hutchins, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To read more about Wingate's continued journey back to India, please follow the link below:

Wingate's Journey Home

Wingate was always concerned about the welfare of the men under his command, past and present, as one small incident may illustrate. Lorna (Wingate's wife) had written to say that she had received an enquiry from the wife of one of Wingate's officers who had not returned from the first Chindit expedition.

This was Lieutenant Lionel Rose of the Sherwood Foresters, the Defence Platoon commander of Wingate's Brigade HQ, who had got as far as the Chindwin on the return journey, only to fall into Japanese hands.

"Would you ask someone to get what details there are for this poor woman?" asked Lorna. Wingate wrote back describing Rose as "a splendid boy" who was "instrumental in saving my own life on one occasion."

"I felt very badly about his loss, which was perhaps partly my fault. He was missing from the time he was last seen, about May 1st, on the Chindwin. I fear the worst, though don't say so to Mrs. Rose. If she is in any want now or in the future we must help her. I feel I am responsible to Rose for that. . . . Rose behaved with the greatest courage and unselfishness. He was devoted to his Ghurkas and owes his present absence to that devotion, otherwise he would have come in my boat, as I asked him to do.

Six weeks later, Wingate received "the glad news that certain of my old Brigade Officers are prisoners of war in Burma" and immediately wrote to tell Lorna that "Rose is said to be one of them." He added: "I do not think they are badly treated by all accounts. They get the Japanese rations which are poor for Englishmen, but there does not seem to be any deliberate ill-treatment there at present."

The Japanese rations that Wingate described were those given out at Rangoon Jail, which is where the men captured in 1943 were eventually taken.

Shown below are some of the men from the dispersal group mentioned by Signalman Eric Hutchins, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To read more about Wingate's continued journey back to India, please follow the link below:

Wingate's Journey Home

As eluded to earlier in this story, Lewis Rose was captured on the 29th April 1943 close to the eastern banks of the Chindwin River. Signalman Eric Hutchins recalled:

He had hid for a time in the jungle, as we had. Then later, made his way down to the Chindwin, found a log on which he hoped he could cross the river. He placed the log in the river, but he couldn't swim you see; he got on the log hoping to float down river. Unfortunately, although he got to the other side, the current close to the west bank was too fast for him and he got swept back to the east side of the river and was picked up by a Japanese sentry.

Lt. Rose was eventually taken to the large concentration camp at Maymyo, where most of the captured Chindits were gathered up prior to being sent down to their final destination as prisoners of war at Rangoon Central Jail.

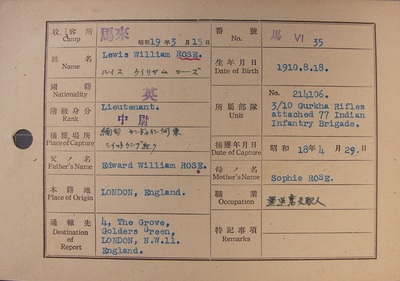

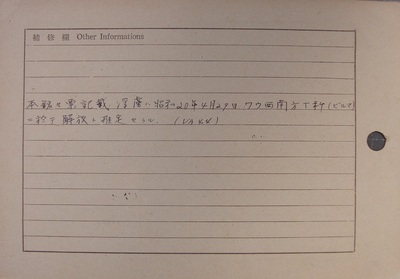

Most of the information about Lewis's time as a POW comes from the document known as a Japanese prisoner index card, these were collated at the time and are written in a mix of English and Kanji style Japanese characters. The cards are held at the National Archives in London under the document file reference WO345. Lieutenant Rose's card (see final image gallery below) shows his date of capture, his next of kin details, his Army service number and unit and his POW number (35) given to him whilst in Rangoon.

Lewis, as an officer would have been held initially in Block 6 of the jail, alongside the other Chindit captives. He would have shared a large single cell with around 20-30 other officers, some of which would have been from other Army regiments captured in actions well before the Chindit expedition of 1943. As time went on some of the Chindit officers were moved across to Block 3, I cannot confirm if Lewis Rose was amongst these men.

Lewis is not mentioned in any of the books written about Rangoon Jail by his fellow Chindit cellmates. However, he does feature in the personal memoir of Captain Richard Allen 'Willie' Wilding, who was also a member of Wingate's Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. Wilding was HQ Cipher Officer in 1943 and was captured close to the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River slightly before Lieutenant Rose lost his own liberty at the Chindwin.

Here is a short extract from Wilding's memoir, which includes a humorous anecdote about an egg:

After Maymyo we had a perfectly foul journey to Rangoon in very hot, metal, closed railway trucks and then were marched from the station to Rangoon Central Jail in Commissioner Road.

I do not intend to try to describe it, just the ordinary oriental clink I suppose, nor to set out the conditions which were foul, or the food which was pretty awful, or the sanitary arrangements which were primitive. We were all, unless very sick, doing about 8 hours coolie work each day with one "yasumi" (rest day) a week. I have avoided telling the horrors here, as there is no point now.

Eggs, we could sometimes buy these. They were usually duck eggs and generally a bit bad. But we thought them life savers.

A young British Officer had died. His estate was one egg and one toothbrush. Another officer had been very good to him. It was decided he should be his legatee. The officer's name was Rose. The egg was duly boiled.

Rose to me: "Willie, have this egg."

Me: "I couldn't possibly."

Rose: "Go on, I want you to have it."

Me: "No, really I can't take it."

Rose: "Please, Willie."

So I ate it and he has never forgiven me! A bit hard, I think.

Either way and eggs or no eggs, both Willie Wilding and Lewis Rose managed to survive all but two years inside Rangoon Jail, until their liberation during what is known as the 'March Out' of the jail in April 1945. As the advancing 14th Army closed in on Rangoon, an order was given for the occupying Japanese garrison to evacuate the city and the decision was made to take the fittest of the prisoners inside the jail with them. Lewis Rose was amongst the 400 men chosen by the jail guards and the march commenced on the 25th April.

For more information about the 'March Out' and other details about life in Rangoon Jail, please click on the following link:

Chindit POW's

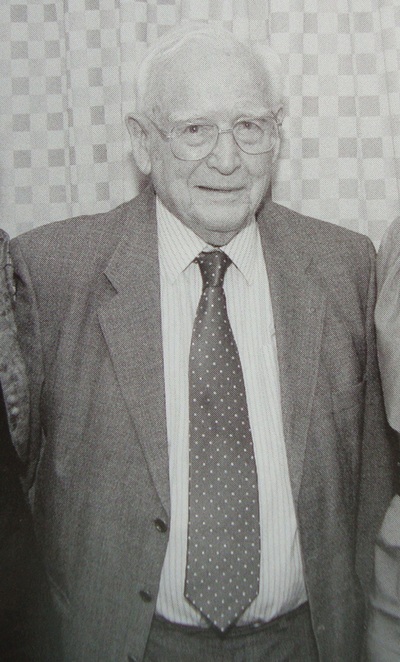

After four arduous days marching, the Japanese finally gave up the idea of trying to take the Allied POW's with them, as they attempted to exit Burma and cross the border into Siam. The 400 men were given their freedom on the 29th April at a village called Waw, near the town of Pegu. After an uncomfortable night spent in the scrub-jungle and some near misses with what we now call 'friendly-fire', the men were liberated by a company of the West Yorkshire Regiment. Eventually Dakota planes were organised and the POW's were flown out to India and received hospital treatment for their various ailments and diseases. A period of rest and recuperation followed before the men were returned to their various Regimental units. Lieutenant Rose presumably went to Dehra Dun where the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles were based. Lewis William Rose died in the first quarter of 2002 in the county of Berkshire, he was 91 years old.

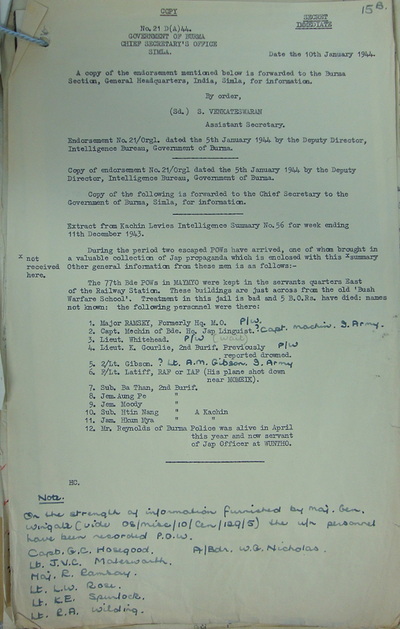

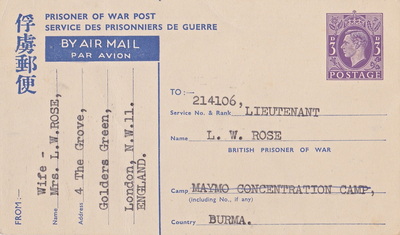

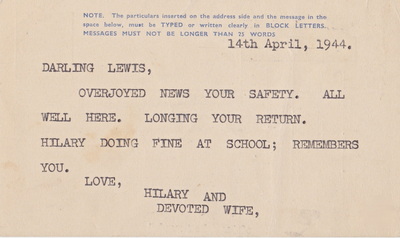

Seen below are some more images in relation to Lewis Rose and his time as a prisoner of war. These include his Japanese index card, both front and reverse sides, a report about the Chindits present at the Maymyo Camp and a postcard sent to Lewis in April 1944 from his wife Rebecca. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

He had hid for a time in the jungle, as we had. Then later, made his way down to the Chindwin, found a log on which he hoped he could cross the river. He placed the log in the river, but he couldn't swim you see; he got on the log hoping to float down river. Unfortunately, although he got to the other side, the current close to the west bank was too fast for him and he got swept back to the east side of the river and was picked up by a Japanese sentry.

Lt. Rose was eventually taken to the large concentration camp at Maymyo, where most of the captured Chindits were gathered up prior to being sent down to their final destination as prisoners of war at Rangoon Central Jail.

Most of the information about Lewis's time as a POW comes from the document known as a Japanese prisoner index card, these were collated at the time and are written in a mix of English and Kanji style Japanese characters. The cards are held at the National Archives in London under the document file reference WO345. Lieutenant Rose's card (see final image gallery below) shows his date of capture, his next of kin details, his Army service number and unit and his POW number (35) given to him whilst in Rangoon.

Lewis, as an officer would have been held initially in Block 6 of the jail, alongside the other Chindit captives. He would have shared a large single cell with around 20-30 other officers, some of which would have been from other Army regiments captured in actions well before the Chindit expedition of 1943. As time went on some of the Chindit officers were moved across to Block 3, I cannot confirm if Lewis Rose was amongst these men.

Lewis is not mentioned in any of the books written about Rangoon Jail by his fellow Chindit cellmates. However, he does feature in the personal memoir of Captain Richard Allen 'Willie' Wilding, who was also a member of Wingate's Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. Wilding was HQ Cipher Officer in 1943 and was captured close to the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River slightly before Lieutenant Rose lost his own liberty at the Chindwin.

Here is a short extract from Wilding's memoir, which includes a humorous anecdote about an egg:

After Maymyo we had a perfectly foul journey to Rangoon in very hot, metal, closed railway trucks and then were marched from the station to Rangoon Central Jail in Commissioner Road.

I do not intend to try to describe it, just the ordinary oriental clink I suppose, nor to set out the conditions which were foul, or the food which was pretty awful, or the sanitary arrangements which were primitive. We were all, unless very sick, doing about 8 hours coolie work each day with one "yasumi" (rest day) a week. I have avoided telling the horrors here, as there is no point now.

Eggs, we could sometimes buy these. They were usually duck eggs and generally a bit bad. But we thought them life savers.

A young British Officer had died. His estate was one egg and one toothbrush. Another officer had been very good to him. It was decided he should be his legatee. The officer's name was Rose. The egg was duly boiled.

Rose to me: "Willie, have this egg."

Me: "I couldn't possibly."

Rose: "Go on, I want you to have it."

Me: "No, really I can't take it."

Rose: "Please, Willie."

So I ate it and he has never forgiven me! A bit hard, I think.

Either way and eggs or no eggs, both Willie Wilding and Lewis Rose managed to survive all but two years inside Rangoon Jail, until their liberation during what is known as the 'March Out' of the jail in April 1945. As the advancing 14th Army closed in on Rangoon, an order was given for the occupying Japanese garrison to evacuate the city and the decision was made to take the fittest of the prisoners inside the jail with them. Lewis Rose was amongst the 400 men chosen by the jail guards and the march commenced on the 25th April.

For more information about the 'March Out' and other details about life in Rangoon Jail, please click on the following link:

Chindit POW's

After four arduous days marching, the Japanese finally gave up the idea of trying to take the Allied POW's with them, as they attempted to exit Burma and cross the border into Siam. The 400 men were given their freedom on the 29th April at a village called Waw, near the town of Pegu. After an uncomfortable night spent in the scrub-jungle and some near misses with what we now call 'friendly-fire', the men were liberated by a company of the West Yorkshire Regiment. Eventually Dakota planes were organised and the POW's were flown out to India and received hospital treatment for their various ailments and diseases. A period of rest and recuperation followed before the men were returned to their various Regimental units. Lieutenant Rose presumably went to Dehra Dun where the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles were based. Lewis William Rose died in the first quarter of 2002 in the county of Berkshire, he was 91 years old.

Seen below are some more images in relation to Lewis Rose and his time as a prisoner of war. These include his Japanese index card, both front and reverse sides, a report about the Chindits present at the Maymyo Camp and a postcard sent to Lewis in April 1944 from his wife Rebecca. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 09/05/2015.

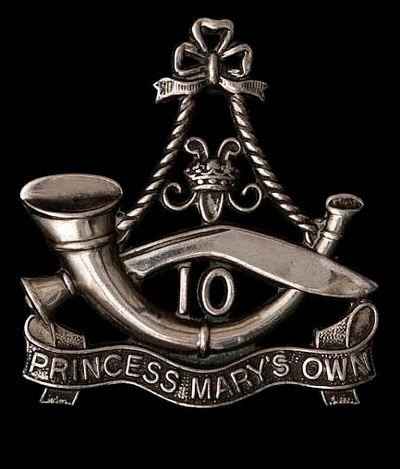

I recently stumbled across some excellent information in regards to Lewis Rose, found in the journal of the 10th Princess Mary's Own Gurkha Rifles. From within the pages of the year 2000 edition of 'the Bugle and Kukri', was an article written by Major-General R.W.L. McAlister. Reproduced here is some of the detail from the article, including invaluable first-hand anecdotes from Rose himself.

Unsung Hero

Written by Major-General R.W.L. McAlister.

Lewis Rose was born in Slough, Berkshire on 18th August 1910 and was part of the Officer Cadet scheme at his school. He enlisted into the Royal Engineers on the 5th September 1939 and became part of the BEF in France involved in pontoon bridge construction. Lewis’ troop was soon in action against the invading German forces, meeting the enemy head-on at the Albert Canal. During the retreat to Dunkirk the truck convoy he was with was constantly dive-bombed by the Luftwaffe. Once inside the protective perimeter around the port, Rose was given the task of manning a Bren gun and ordered to fire upon incoming enemy aircraft. Eventually, his RE unit was lifted off the crowded beaches by a Danish fishing vessel, but not before Rose had been wounded by a shell splinter.

Back in England, he was posted to Ripon in Yorkshire, where he performed the role of motorcycle instructor. He was then commissioned into the Sherwood Foresters on the 25th October 1941, but before long was told that he had been chosen from amongst the latest recruits to join the Indian Army. Lewis complained that being of Jewish stock, he desperately wanted to fight against the Germans in Europe. The Commanding Officer apologised but told him that nothing could be done to change this posting.

Lewis Rose arrived in India like so many soldiers before him at the gateway port of Bombay; he then proceeded to Bangalore where he spent the next few weeks acclimatising to life on the sub-continent. When asked about his preference for regiment placement, he simply stated ‘Gurkhas’. He got his wish and was posted to the 3rd Battalion of the 10th Princess Mary’s Own Gurkha Rifles and then moved out to Assam in June 1942, assisting with the return of the remnants of the British Army from Burma.

Later on, Rose commanded the rudimentarily built, Fort Chassud, situated some miles back from the unofficial border with Burma on the line of the Chindwin River. Here he kept watch for enemy activity and on occasions probed forward on aggressive patrols in order to ascertain intelligence about Japanese numbers and positions. On one such patrol he captured four Japanese soldiers and brought them back for interrogation.

Lieutenant Rose was promoted to Liaison Officer for the Headquarters of the 23rd Indian Division, at that time commanded by Major-General Savory. This promotion carried with it a guaranteed majority, but before this elevation in the ranks could be confirmed, fate was to intervene with the arrival of Brigadier Wingate and his fledgling Chindit force. Rose was detailed to accompany the Chindits as a guide and lead them to the western banks of the Chindwin River.

General Savory had made it quite clear to his Liaison Officer that he was to return immediately after the Chindits had reached the river and was under no circumstances to cross with them in to enemy held territory. Once again fate intervened. Wingate’s Defence Platoon commander fell unexpectedly ill and had to be sent back to India, Wingate turned to Rose and ordered him to take over this unit.

Lieutenant Rose argued his position and informed Wingate of General Savory’s strict instruction that he was not to travel with the Chindit Brigade any further than the Chindwin. Wingate waved these protests aside, promising that he would communicate with Savory and explain the situation, and that Rose would only have to accompany his HQ for a few more days, after which he could return to India. As it turned out Rose never did return and remained in command of the Defence Platoon throughout the rest of the expedition. The Defence Platoon was made up of 45 Gurkha Riflemen and was effectively a bodyguard for the Brigadier during the long and arduous marches inside Burma that year. Lewis Rose, being used to these conditions and also extremely fit, was able to keep up with the Brigade with little difficulty.

Seen below is a map of the area around Fort Chassud, Lieutenant Rose's first area of command in 1942. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

I recently stumbled across some excellent information in regards to Lewis Rose, found in the journal of the 10th Princess Mary's Own Gurkha Rifles. From within the pages of the year 2000 edition of 'the Bugle and Kukri', was an article written by Major-General R.W.L. McAlister. Reproduced here is some of the detail from the article, including invaluable first-hand anecdotes from Rose himself.

Unsung Hero

Written by Major-General R.W.L. McAlister.

Lewis Rose was born in Slough, Berkshire on 18th August 1910 and was part of the Officer Cadet scheme at his school. He enlisted into the Royal Engineers on the 5th September 1939 and became part of the BEF in France involved in pontoon bridge construction. Lewis’ troop was soon in action against the invading German forces, meeting the enemy head-on at the Albert Canal. During the retreat to Dunkirk the truck convoy he was with was constantly dive-bombed by the Luftwaffe. Once inside the protective perimeter around the port, Rose was given the task of manning a Bren gun and ordered to fire upon incoming enemy aircraft. Eventually, his RE unit was lifted off the crowded beaches by a Danish fishing vessel, but not before Rose had been wounded by a shell splinter.

Back in England, he was posted to Ripon in Yorkshire, where he performed the role of motorcycle instructor. He was then commissioned into the Sherwood Foresters on the 25th October 1941, but before long was told that he had been chosen from amongst the latest recruits to join the Indian Army. Lewis complained that being of Jewish stock, he desperately wanted to fight against the Germans in Europe. The Commanding Officer apologised but told him that nothing could be done to change this posting.

Lewis Rose arrived in India like so many soldiers before him at the gateway port of Bombay; he then proceeded to Bangalore where he spent the next few weeks acclimatising to life on the sub-continent. When asked about his preference for regiment placement, he simply stated ‘Gurkhas’. He got his wish and was posted to the 3rd Battalion of the 10th Princess Mary’s Own Gurkha Rifles and then moved out to Assam in June 1942, assisting with the return of the remnants of the British Army from Burma.

Later on, Rose commanded the rudimentarily built, Fort Chassud, situated some miles back from the unofficial border with Burma on the line of the Chindwin River. Here he kept watch for enemy activity and on occasions probed forward on aggressive patrols in order to ascertain intelligence about Japanese numbers and positions. On one such patrol he captured four Japanese soldiers and brought them back for interrogation.

Lieutenant Rose was promoted to Liaison Officer for the Headquarters of the 23rd Indian Division, at that time commanded by Major-General Savory. This promotion carried with it a guaranteed majority, but before this elevation in the ranks could be confirmed, fate was to intervene with the arrival of Brigadier Wingate and his fledgling Chindit force. Rose was detailed to accompany the Chindits as a guide and lead them to the western banks of the Chindwin River.

General Savory had made it quite clear to his Liaison Officer that he was to return immediately after the Chindits had reached the river and was under no circumstances to cross with them in to enemy held territory. Once again fate intervened. Wingate’s Defence Platoon commander fell unexpectedly ill and had to be sent back to India, Wingate turned to Rose and ordered him to take over this unit.

Lieutenant Rose argued his position and informed Wingate of General Savory’s strict instruction that he was not to travel with the Chindit Brigade any further than the Chindwin. Wingate waved these protests aside, promising that he would communicate with Savory and explain the situation, and that Rose would only have to accompany his HQ for a few more days, after which he could return to India. As it turned out Rose never did return and remained in command of the Defence Platoon throughout the rest of the expedition. The Defence Platoon was made up of 45 Gurkha Riflemen and was effectively a bodyguard for the Brigadier during the long and arduous marches inside Burma that year. Lewis Rose, being used to these conditions and also extremely fit, was able to keep up with the Brigade with little difficulty.

Seen below is a map of the area around Fort Chassud, Lieutenant Rose's first area of command in 1942. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Brigadier Wingate proved a very hard taskmaster during the weeks and months of Operation Longcloth and on occasions he and Rose took part in some heated verbal exchanges. Lieutenant Rose takes up the story:

He got up everyone's nose. You never knew how you stood with him, pleased with you one moment and shouting at you another. He had no idea of sensible infantry tactics. On one occasion, he said to me 'Rose, I want you to gallop down into that village at full tilt, see if there are any Japs there and gallop back'. I told him that this was tactically unwise and I would take a foot patrol instead.

On another occasion, I was ordered to block one of the several tracks leading to an airdrop zone from the village of Baw, just west of the Shweli River, where there was a small enemy garrison. The Japanese tried to interfere and Wingate congratulated me for helping to hold them off in a stiff little fight. We called this the battle of Baw. But then, a few days later when he and I were crossing a stream by a small footbridge, one of my Gurkha muleteers happily splashed his way over through the water. Wingate, apparently incensed at being, as he thought, upstaged, started to bawl me out about my Gurkhas ‘arrogance'. I lost my cool and said 'Don't dare to speak to me like that in front of my men ever again'. This silenced him for the moment.

On another occasion in bivouac, I noticed the Signals and HQ elements disappearing into the jungle at haste and I asked Wingate what was going on, he said, 'I'm having a test exercise in dispersal.' I said 'this is crazy, you can't do this. The men are exhausted and the Japs aren't far away.’

‘I've done it’ he said, and fired his rifle in the air over my head. Once more I lost my cool and drew my pistol and fired it into the ground at his feet. Of course, he was furious. We soon came to a village where the Headman welcomed us and presented Wingate with a huge bunch of bananas. With all the officers standing round, Wingate started to give each officer a banana. When he came to me, he passed on without giving me one. Later in bivouac, the officers laughed and said 'Poor old Rosie, no banana', but I was not amused. Wingate had behaved like a small child.

He got up everyone's nose. You never knew how you stood with him, pleased with you one moment and shouting at you another. He had no idea of sensible infantry tactics. On one occasion, he said to me 'Rose, I want you to gallop down into that village at full tilt, see if there are any Japs there and gallop back'. I told him that this was tactically unwise and I would take a foot patrol instead.

On another occasion, I was ordered to block one of the several tracks leading to an airdrop zone from the village of Baw, just west of the Shweli River, where there was a small enemy garrison. The Japanese tried to interfere and Wingate congratulated me for helping to hold them off in a stiff little fight. We called this the battle of Baw. But then, a few days later when he and I were crossing a stream by a small footbridge, one of my Gurkha muleteers happily splashed his way over through the water. Wingate, apparently incensed at being, as he thought, upstaged, started to bawl me out about my Gurkhas ‘arrogance'. I lost my cool and said 'Don't dare to speak to me like that in front of my men ever again'. This silenced him for the moment.

On another occasion in bivouac, I noticed the Signals and HQ elements disappearing into the jungle at haste and I asked Wingate what was going on, he said, 'I'm having a test exercise in dispersal.' I said 'this is crazy, you can't do this. The men are exhausted and the Japs aren't far away.’

‘I've done it’ he said, and fired his rifle in the air over my head. Once more I lost my cool and drew my pistol and fired it into the ground at his feet. Of course, he was furious. We soon came to a village where the Headman welcomed us and presented Wingate with a huge bunch of bananas. With all the officers standing round, Wingate started to give each officer a banana. When he came to me, he passed on without giving me one. Later in bivouac, the officers laughed and said 'Poor old Rosie, no banana', but I was not amused. Wingate had behaved like a small child.

Lewis Rose continues:

When the time came for the HQ group to disperse and make its way back to India, I commanded the rear-guard on the east bank of the Irrawaddy with a small party of eleven men, while Wingate's own party of thirty crossed to the west bank. The plan was for a boat to be sent back for me and my men. Wingate's last words to me before he crossed the Irrawaddy had been 'Rose, if you find you can't get across, make for China, I will see General Savory and will also write to your wife'. But a Nip patrol engaged us on the east bank and in the firefight I lost five of my men.

Wingate pushed on leaving me to my own devices. No boat was sent back. One of Wingate's group, Signals Officer Kenneth Spurlock, was later captured and I met him in Rangoon jail. He told me that Wingate, safely across, had said at the time 'Rose will never make it. We must get on'.

Wingate did not keep the first of these promises. He did later signal my wife when an escaped Gurkha Other Rank from the force, brought the news nearly a year later, that I was alive in a Maymyo jail. In the interim, the 3rd/10th Gurkha Rifles, making some assumptions and collecting information from Burmese villagers in the Chindwin area, became convinced that I was dead and wrote accordingly to my wife.

How this all came about needs to be told. My small party east of the Irrawaddy now consisted of a Gurkha Havildar, two Gurkha Other Ranks, Flight Lieutenant Tooth and two BORs. The hardships of our withdrawal may be imagined. They were typical for all such parties involved and have been well described and need not be repeated. My party made it intact as far as the Zibu Taungdan escarpment. There, the two BORs finally gave up and, in their debilitated state, refused to climb this very difficult obstacle. My four companions and I struggled on to reach a point some two miles short of the Chindwin.

With the river so close, we were ambushed by a Japanese patrol. In our exhausted state, we fired back. I blew my whistle and shouted orders, trying to indicate that we were a strong party. I was wounded in the legs by a grenade and couldn't move but my ruse worked and, amazingly the Japs withdrew. But my group had scattered and I found myself entirely on my own.

For three days, I avoided Jap patrols, hoping to find the strength to get to the river and across it. Then I was discovered by a Burmese Traitor Army patrol while being fed by friendly villagers. I shouldn't have chanced going near the village but I was hungry with a capital H. As I lay on the ground, I was bayoneted in the buttock and eventually, my wounds untended, tied upright to a tree. The marks are on my wrists to this day.

A Jap officer appeared. He spoke impeccable English and said that he had been educated at Winchester. He said that he was going to free my hands and give me back my pistol so I could kill myself, since I had fought honourably until disabled and that it was dishonourable to be a prisoner. I said I refused to kill myself, since I was a married man and owed it to my wife to survive this war. The officer then said that, in that case, he would either shoot me with his pistol or despatch me with his sword: which was it to be? In pain and in a desperate state, I said 'If you intend to murder me, you must choose which weapon to use'. He was so taken aback by my use of the word 'murder' that he spared me.

I was carried off to Maymyo where I spent some weeks and was later taken by train to Rangoon and the jail. My earliest memory of the Maymyo POW cage, while still unable to stand without pain, was of a Jap NCO shouting at me in Japanese. I didn't know what it all meant but in the background I saw another prisoner bowing repeatedly to indicate to me that that was what the Nip wanted me to do.

It was in Maymyo that I learned yet again the true depths of Japanese brutality. A fellow prisoner there was Lieutenant Kirkpatrick, an officer of a Gurkha battalion, but not from the Wingate Force. He had been badly wounded on a patrol over the Chindwin. He told me that I was in trouble for disobeying General Savory's orders, and I had to live with that thought for two long years. Kirkpatrick's wounds seemed to affect his judgement. Unwisely, he was truculent and abusive to his captors, shouting 'You're all bastards and I won't tell you anything'. In fact, he knew very little of value, but the Nips gained the impression that he did. They beat him severely, gave him the water treatment and burned the flesh from his hands, nose and face. He went completely insane and I buried him in Maymyo on 3rd July 1943.

NB. This was Lieutenant William George Kirkpatrick of 3/5 Gurkha Rifles, who had been sent out in April 1943 to assist the men of Operation Longcloth to regain the safety of the Chindwin River. To read more about the Maymyo concentration camp, please click on the following link: Maymo POW Camp

For more information about William Kirkpatrick, please click on the following link to his own story on these website pages:

Lieut. William George Kirkpatrick

Lewis Rose concludes:

In Rangoon, my wounds took over a year to heal for there were little or no medicines available. The muscles and tendons in my leg were badly damaged. In the jail, I recall on one occasion having to hold a man down on a makeshift operating table whilst his leg was amputated without anaesthetic. We lived there on a diet of rice and vegetable water. On release from Rangoon in 1945, I was in and out of hospital for more than a year. I fought hard for recognition of my right to a majority in accordance with my appointment as Liaison Officer at 23rd Division HQ. With the help of General Savory, to whom I apologised for unwittingly disobeying his orders, this was approved and back dated to 15th December 1942. In 1946, I received my Military Cross through the post, without any explanation. I still do not know who recommended me for it. I was one of a number of officers and men included in an edition of the London Gazette for services prior to or actually in captivity.

When the time came for the HQ group to disperse and make its way back to India, I commanded the rear-guard on the east bank of the Irrawaddy with a small party of eleven men, while Wingate's own party of thirty crossed to the west bank. The plan was for a boat to be sent back for me and my men. Wingate's last words to me before he crossed the Irrawaddy had been 'Rose, if you find you can't get across, make for China, I will see General Savory and will also write to your wife'. But a Nip patrol engaged us on the east bank and in the firefight I lost five of my men.

Wingate pushed on leaving me to my own devices. No boat was sent back. One of Wingate's group, Signals Officer Kenneth Spurlock, was later captured and I met him in Rangoon jail. He told me that Wingate, safely across, had said at the time 'Rose will never make it. We must get on'.

Wingate did not keep the first of these promises. He did later signal my wife when an escaped Gurkha Other Rank from the force, brought the news nearly a year later, that I was alive in a Maymyo jail. In the interim, the 3rd/10th Gurkha Rifles, making some assumptions and collecting information from Burmese villagers in the Chindwin area, became convinced that I was dead and wrote accordingly to my wife.

How this all came about needs to be told. My small party east of the Irrawaddy now consisted of a Gurkha Havildar, two Gurkha Other Ranks, Flight Lieutenant Tooth and two BORs. The hardships of our withdrawal may be imagined. They were typical for all such parties involved and have been well described and need not be repeated. My party made it intact as far as the Zibu Taungdan escarpment. There, the two BORs finally gave up and, in their debilitated state, refused to climb this very difficult obstacle. My four companions and I struggled on to reach a point some two miles short of the Chindwin.

With the river so close, we were ambushed by a Japanese patrol. In our exhausted state, we fired back. I blew my whistle and shouted orders, trying to indicate that we were a strong party. I was wounded in the legs by a grenade and couldn't move but my ruse worked and, amazingly the Japs withdrew. But my group had scattered and I found myself entirely on my own.

For three days, I avoided Jap patrols, hoping to find the strength to get to the river and across it. Then I was discovered by a Burmese Traitor Army patrol while being fed by friendly villagers. I shouldn't have chanced going near the village but I was hungry with a capital H. As I lay on the ground, I was bayoneted in the buttock and eventually, my wounds untended, tied upright to a tree. The marks are on my wrists to this day.

A Jap officer appeared. He spoke impeccable English and said that he had been educated at Winchester. He said that he was going to free my hands and give me back my pistol so I could kill myself, since I had fought honourably until disabled and that it was dishonourable to be a prisoner. I said I refused to kill myself, since I was a married man and owed it to my wife to survive this war. The officer then said that, in that case, he would either shoot me with his pistol or despatch me with his sword: which was it to be? In pain and in a desperate state, I said 'If you intend to murder me, you must choose which weapon to use'. He was so taken aback by my use of the word 'murder' that he spared me.

I was carried off to Maymyo where I spent some weeks and was later taken by train to Rangoon and the jail. My earliest memory of the Maymyo POW cage, while still unable to stand without pain, was of a Jap NCO shouting at me in Japanese. I didn't know what it all meant but in the background I saw another prisoner bowing repeatedly to indicate to me that that was what the Nip wanted me to do.

It was in Maymyo that I learned yet again the true depths of Japanese brutality. A fellow prisoner there was Lieutenant Kirkpatrick, an officer of a Gurkha battalion, but not from the Wingate Force. He had been badly wounded on a patrol over the Chindwin. He told me that I was in trouble for disobeying General Savory's orders, and I had to live with that thought for two long years. Kirkpatrick's wounds seemed to affect his judgement. Unwisely, he was truculent and abusive to his captors, shouting 'You're all bastards and I won't tell you anything'. In fact, he knew very little of value, but the Nips gained the impression that he did. They beat him severely, gave him the water treatment and burned the flesh from his hands, nose and face. He went completely insane and I buried him in Maymyo on 3rd July 1943.

NB. This was Lieutenant William George Kirkpatrick of 3/5 Gurkha Rifles, who had been sent out in April 1943 to assist the men of Operation Longcloth to regain the safety of the Chindwin River. To read more about the Maymyo concentration camp, please click on the following link: Maymo POW Camp

For more information about William Kirkpatrick, please click on the following link to his own story on these website pages:

Lieut. William George Kirkpatrick

Lewis Rose concludes:

In Rangoon, my wounds took over a year to heal for there were little or no medicines available. The muscles and tendons in my leg were badly damaged. In the jail, I recall on one occasion having to hold a man down on a makeshift operating table whilst his leg was amputated without anaesthetic. We lived there on a diet of rice and vegetable water. On release from Rangoon in 1945, I was in and out of hospital for more than a year. I fought hard for recognition of my right to a majority in accordance with my appointment as Liaison Officer at 23rd Division HQ. With the help of General Savory, to whom I apologised for unwittingly disobeying his orders, this was approved and back dated to 15th December 1942. In 1946, I received my Military Cross through the post, without any explanation. I still do not know who recommended me for it. I was one of a number of officers and men included in an edition of the London Gazette for services prior to or actually in captivity.

Major-General McAlister’s postscript to his article is of very great interest as it concerns the experiences of Lieutenant Rose's wife, Rebecca and her long wait for news of her husband’s fate.

Rebecca, like so many of the other wives and relatives of Longcloth casualties, had received only the barest information that her husband had been with the first expedition, but was now listed as ‘missing in action’. After some other official communiqués from the War Office, she, just like my own grandmother had her war pension and other monies reduced due to Lewis’ ‘missing’ status.

In July 1943, Rebecca received two terrible blows to her hopes that Lewis was still alive. Firstly, letters from the 3/10th Gurkha Rifles HQ and then from Major Bromhead who had commanded Chindit Column 4 on Operation Longcloth, both correspondence casting great doubt on the prospects of his survival. Another savage blow was the arrival of Lewis' Army trunk and other personal belongings, sent back to England from India.

However, Rebecca was made of sterner stuff and she never gave up the hope that she would see her husband once more. She sent an array of letters to organisations such as the International Red Cross and the India Office, asking for more information about the circumstances of her husband’s disappearance in Burma. She also wrote letters to Lorna Wingate, to Wingate himself and to Major Mike Calvert, pleading with them for more details about her husband's last known whereabouts.

Then on the 4th March 1944, almost one year since his disappearance (Lewis had been captured by the Japanese on the 29th April 1943), she received a letter from Lorna Wingate informing her that Lewis was alive. Lorna Wingate wrote: “What a very tough and clever person he must be to have maintained himself all this time, one supposes in Jap held territory”.

Rebecca wrongly assumed that Lewis was hiding out in the Burmese jungle. Within a few days she received another communiqué from the Wingate’s and then a letter from the Red Cross explaining that Lewis was in fact a prisoner of war and being held at Maymyo. In actual fact Lieutenant Rose was now being held in Rangoon Central Jail and had been at this location since August 1943. The confirmation of his presence at the Maymyo Camp was given by an escaped Gurkha Other Rank, who had recently returned to India and on debrief had passed on all he knew about missing Chindit personnel.

Whilst a prisoner of war Lewis received only one of Rebecca’s postcards, dated the 29th April 1944, even then this card only reached him at Rangoon on the 16th February 1945! He was permitted to write his first and only card home on the 1st March; within 8 weeks he would be a free man once more after liberation near the Burmese town of Pegu.

NB. As we already know from the first section of this story, Rebecca had sent Lewis at least one other postcard, dated 14th April 1944 and addressed to the Maymyo Concentration Camp. (Please see images of this card in the third gallery shown above).

It is impossible to imagine the stress that Rebecca Rose and the other relatives of Operation Longcloth casualties must have gone through during the years 1943-1945. I know that my Nan could not bring herself to believe that her own dear husband had perished and would not be coming home from Burma after the war. Rebecca and her daughter Hilary, had experienced their own personal trauma in October 1940, when their home in London was damaged beyond repair during the Blitz. Rebecca and her daughter moved back to her parents’ home in Golders Green and then out of London altogether to escape the threat from Hitler’s V-Bombs.

Lewis Rose died in early 2002 in the county of Berkshire, he was 91 years old. He and Rebecca had deservedly enjoyed a long and happy life together after experiencing such a harrowing time through the years of WW2.

Rebecca, like so many of the other wives and relatives of Longcloth casualties, had received only the barest information that her husband had been with the first expedition, but was now listed as ‘missing in action’. After some other official communiqués from the War Office, she, just like my own grandmother had her war pension and other monies reduced due to Lewis’ ‘missing’ status.

In July 1943, Rebecca received two terrible blows to her hopes that Lewis was still alive. Firstly, letters from the 3/10th Gurkha Rifles HQ and then from Major Bromhead who had commanded Chindit Column 4 on Operation Longcloth, both correspondence casting great doubt on the prospects of his survival. Another savage blow was the arrival of Lewis' Army trunk and other personal belongings, sent back to England from India.

However, Rebecca was made of sterner stuff and she never gave up the hope that she would see her husband once more. She sent an array of letters to organisations such as the International Red Cross and the India Office, asking for more information about the circumstances of her husband’s disappearance in Burma. She also wrote letters to Lorna Wingate, to Wingate himself and to Major Mike Calvert, pleading with them for more details about her husband's last known whereabouts.

Then on the 4th March 1944, almost one year since his disappearance (Lewis had been captured by the Japanese on the 29th April 1943), she received a letter from Lorna Wingate informing her that Lewis was alive. Lorna Wingate wrote: “What a very tough and clever person he must be to have maintained himself all this time, one supposes in Jap held territory”.

Rebecca wrongly assumed that Lewis was hiding out in the Burmese jungle. Within a few days she received another communiqué from the Wingate’s and then a letter from the Red Cross explaining that Lewis was in fact a prisoner of war and being held at Maymyo. In actual fact Lieutenant Rose was now being held in Rangoon Central Jail and had been at this location since August 1943. The confirmation of his presence at the Maymyo Camp was given by an escaped Gurkha Other Rank, who had recently returned to India and on debrief had passed on all he knew about missing Chindit personnel.

Whilst a prisoner of war Lewis received only one of Rebecca’s postcards, dated the 29th April 1944, even then this card only reached him at Rangoon on the 16th February 1945! He was permitted to write his first and only card home on the 1st March; within 8 weeks he would be a free man once more after liberation near the Burmese town of Pegu.

NB. As we already know from the first section of this story, Rebecca had sent Lewis at least one other postcard, dated 14th April 1944 and addressed to the Maymyo Concentration Camp. (Please see images of this card in the third gallery shown above).

It is impossible to imagine the stress that Rebecca Rose and the other relatives of Operation Longcloth casualties must have gone through during the years 1943-1945. I know that my Nan could not bring herself to believe that her own dear husband had perished and would not be coming home from Burma after the war. Rebecca and her daughter Hilary, had experienced their own personal trauma in October 1940, when their home in London was damaged beyond repair during the Blitz. Rebecca and her daughter moved back to her parents’ home in Golders Green and then out of London altogether to escape the threat from Hitler’s V-Bombs.

Lewis Rose died in early 2002 in the county of Berkshire, he was 91 years old. He and Rebecca had deservedly enjoyed a long and happy life together after experiencing such a harrowing time through the years of WW2.

Copyright © Steve Fogden July 2014-15 and Major-General R.W.L. McAlister (2000).