Lt. William Jocelyn Smyly

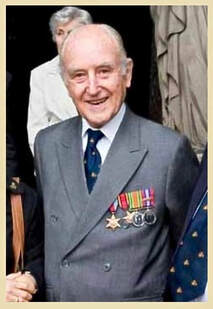

Bill Smyly in 2009.

Bill Smyly in 2009.

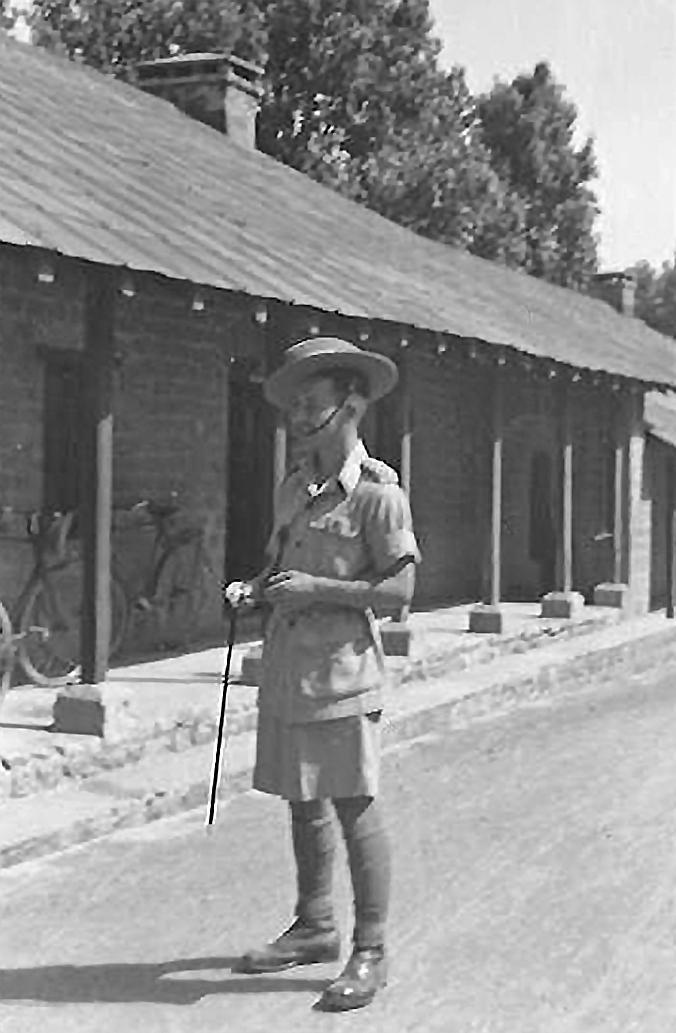

When the mules finally arrived, it was a beautiful sight seeing them splashing through the river, headed by a small and eager young officer on a fine looking mare. This was Bill Smyly, my new animal transport officer. Just nineteen years old, (and the youngest man in the column) he had come out from home a year before to join a Gurkha Regiment, and having an Irish passion for horses, had been selected for training as an ATO.

It was hard to say which he liked best, his animals or his Gurkhas; he would tenderly spare the former, but never the latter. Although easily the youngest officer in the column, he had no fear of anybody and would chastise any officer, however senior, who failed to take care of his mules. He certainly was in my mind, the Monarch of the Muleteers.

(Bernard Fergusson in 1946).

Bill Smyly was one of the first Chindit veterans I ever had the pleasure to talk to, and was the only Longcloth veteran who served with No. 5 Column in 1943 that I have ever met in person. From our initial meeting at the Chindit Old Comrades Reunion in June 2009, up until our last chat at 77 Brigade's Chindwin Dinner in January 2018, he has always been so accommodating and thoughtful in answering the multitude of questions I was always so keen to ask.

Talking with Bill was always interesting, illuminating and humorous; our chats were charged with unexpected anecdotes in relation to Operation Longcloth, but also thought provoking messages about the true emotions of war and quite often reflective consideration for the men he had fought against, namely the Japanese.

I have decided to bring Bill Smyly's story to these website pages, in a slightly different manner than my normal format in presenting a Chindit veterans wartime experiences in Burma. There is a wealth of information to be found in books, in film footage online and of course remarks and anecdotes from the friends and family members who knew and loved Bill so well. I hope that after reading, watching and listening to the following account of his life, you will also get to know this wonderful and inspiring man.

Before I go any further, I would like to thank Diana Smyly (Bill's wife) and her family, especially Chris Smyly, who has worked diligently in filming and recording Bill's memories and thoughts on the war and the consequences it brought to those who fought and lived through those terrible times. I would like to thank authors, Tony Redding (War in the Wilderness) and Philip Chinnery (Wingate's Lost Brigade), for allowing me to use some of the information they collected together through their own interviews with Bill Smyly and to anyone else who has contributed to this narrative through their own association or connection with the man in question.

To begin with, I thought it would be fitting to listen to the man himself and to learn his thoughts about being a soldier during WW2. These short video clips come courtesy of Chris Smyly and were filmed over the last few years:

It was hard to say which he liked best, his animals or his Gurkhas; he would tenderly spare the former, but never the latter. Although easily the youngest officer in the column, he had no fear of anybody and would chastise any officer, however senior, who failed to take care of his mules. He certainly was in my mind, the Monarch of the Muleteers.

(Bernard Fergusson in 1946).

Bill Smyly was one of the first Chindit veterans I ever had the pleasure to talk to, and was the only Longcloth veteran who served with No. 5 Column in 1943 that I have ever met in person. From our initial meeting at the Chindit Old Comrades Reunion in June 2009, up until our last chat at 77 Brigade's Chindwin Dinner in January 2018, he has always been so accommodating and thoughtful in answering the multitude of questions I was always so keen to ask.

Talking with Bill was always interesting, illuminating and humorous; our chats were charged with unexpected anecdotes in relation to Operation Longcloth, but also thought provoking messages about the true emotions of war and quite often reflective consideration for the men he had fought against, namely the Japanese.

I have decided to bring Bill Smyly's story to these website pages, in a slightly different manner than my normal format in presenting a Chindit veterans wartime experiences in Burma. There is a wealth of information to be found in books, in film footage online and of course remarks and anecdotes from the friends and family members who knew and loved Bill so well. I hope that after reading, watching and listening to the following account of his life, you will also get to know this wonderful and inspiring man.

Before I go any further, I would like to thank Diana Smyly (Bill's wife) and her family, especially Chris Smyly, who has worked diligently in filming and recording Bill's memories and thoughts on the war and the consequences it brought to those who fought and lived through those terrible times. I would like to thank authors, Tony Redding (War in the Wilderness) and Philip Chinnery (Wingate's Lost Brigade), for allowing me to use some of the information they collected together through their own interviews with Bill Smyly and to anyone else who has contributed to this narrative through their own association or connection with the man in question.

To begin with, I thought it would be fitting to listen to the man himself and to learn his thoughts about being a soldier during WW2. These short video clips come courtesy of Chris Smyly and were filmed over the last few years:

As mentioned earlier by Bernard Fergusson, Bill Smyly became the Animal Transport Officer for No. 5 Column on Operation Longcloth and was in charge, not only of his beloved mules, but also the Gurkha Riflemen that drove these animals. It is not commonly known, but Bill was rather fortunate to survive his time on the first Wingate expedition and owed his eventual salvation to the Kachin and Shan tribes people who cared for him during his long and arduous exit from Burma in 1943.

Bill recalled:

On both Wingate operations, the Kachins, Shans and Karens were our eyes and ears and showed great courage and loyalty to our cause. This was shown by the Burma Riflemen who fought with us, but also by the villagers we met along the way. It is not possible to exaggerate their importance to these operations.

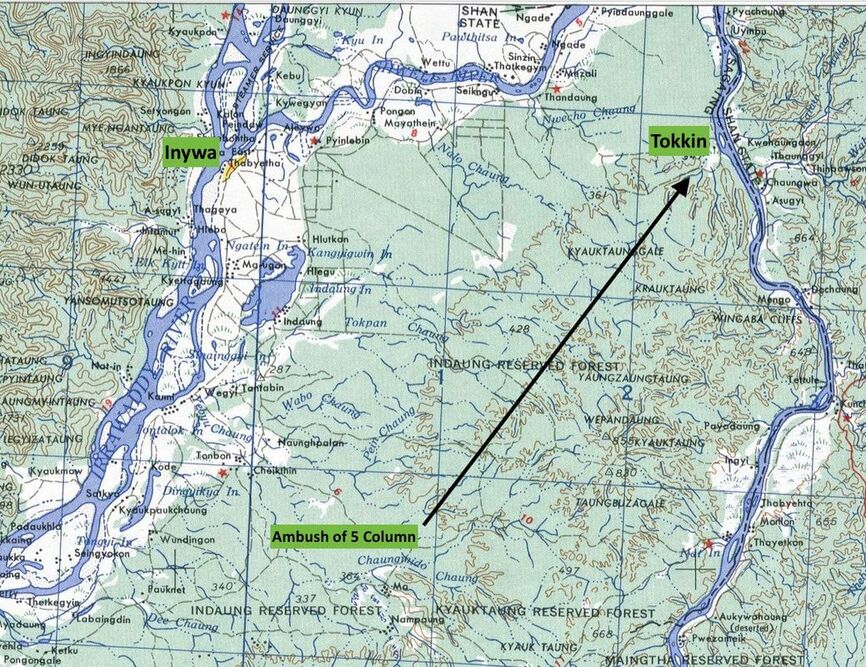

I was ATO in No. 5 Column led by Major Bernard Fergusson. For me, after our column broke up in the ambush in which Lt. Stibbe was wounded (Hintha), I crossed a fast running river called the Shweli with six of my men, having lost 28 others who were stuck on the other side when someone's hand slipped and the rubber dinghy we were using was swept away downstream with two men in it. We headed north without a map, but caught up with a group of about 60 led by Major Astell of the Burma Rifles. I think we spun out 8 days rations for 28 days. In the end I lost my central vision with beri beri and had swollen ankles that slowed me down going up hill. I refused to let my men hang back at my pace and drove them on, with myself climbing the hills side ways like a crab or backwards and running down the other side. This worked well for several days till one evening when I was running too fast, missed the path, and ran off into the forest.

Lost, and with night coming on, I sat down by a stream, boiled some water for tea, and then slept. In the morning I was covered with leeches. I undressed and shaved these off with my kukri. They fell off like grapes and swam away. The stream was the worst possible place I could have spent the night. In the morning, sight restored, I retraced my steps and found the track. To my surprise it was the greatest relief to be on my own and not have to keep up with the others, but I now went very slowly. Ahead was an enormous climb. Half way up there was one place where I looked out over the surrounding forest canopy, wave after wave of it, and felt that I had only to press the ground with my toes and I would rise into the air and soar over hill and dale all the way back to India. I felt a sense of elation and was probably experiencing some sort of high through exhaustion and hunger.

Later on up on the hill I found a hollow bamboo cane driven into a rivulet and clear water poured from this onto bright stones at the side of the path. Beside this was a mossy bank and I don't think any chair has ever been more comfortable or any water sweeter. I was sitting there half in heaven when an old mother and her pretty daughter climbed up the road. They found me totally exhausted and idiotically happy and they were there again in the village at the top of the hill with a brew of rice wine for me, before they brought me on to the house of the Headman of the village.

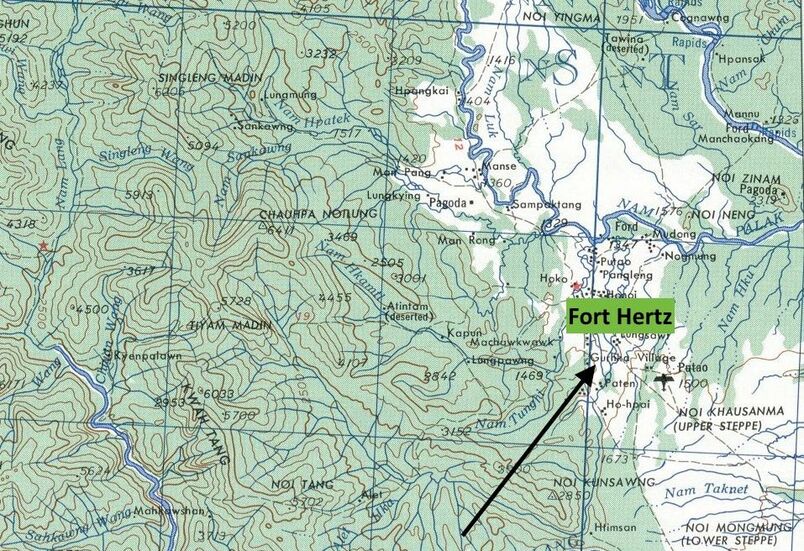

From then I was looked after in Kachin villages for nearly three months. When I reached a village and took off my boots and my ankles blew up like balloons and I would sit there till I could get my boots on again, maybe two days, sometimes three and then press on. Somewhere in the distant north there was a British outpost called Fort Hertz and this was where I was heading.

Bill recalled:

On both Wingate operations, the Kachins, Shans and Karens were our eyes and ears and showed great courage and loyalty to our cause. This was shown by the Burma Riflemen who fought with us, but also by the villagers we met along the way. It is not possible to exaggerate their importance to these operations.

I was ATO in No. 5 Column led by Major Bernard Fergusson. For me, after our column broke up in the ambush in which Lt. Stibbe was wounded (Hintha), I crossed a fast running river called the Shweli with six of my men, having lost 28 others who were stuck on the other side when someone's hand slipped and the rubber dinghy we were using was swept away downstream with two men in it. We headed north without a map, but caught up with a group of about 60 led by Major Astell of the Burma Rifles. I think we spun out 8 days rations for 28 days. In the end I lost my central vision with beri beri and had swollen ankles that slowed me down going up hill. I refused to let my men hang back at my pace and drove them on, with myself climbing the hills side ways like a crab or backwards and running down the other side. This worked well for several days till one evening when I was running too fast, missed the path, and ran off into the forest.

Lost, and with night coming on, I sat down by a stream, boiled some water for tea, and then slept. In the morning I was covered with leeches. I undressed and shaved these off with my kukri. They fell off like grapes and swam away. The stream was the worst possible place I could have spent the night. In the morning, sight restored, I retraced my steps and found the track. To my surprise it was the greatest relief to be on my own and not have to keep up with the others, but I now went very slowly. Ahead was an enormous climb. Half way up there was one place where I looked out over the surrounding forest canopy, wave after wave of it, and felt that I had only to press the ground with my toes and I would rise into the air and soar over hill and dale all the way back to India. I felt a sense of elation and was probably experiencing some sort of high through exhaustion and hunger.

Later on up on the hill I found a hollow bamboo cane driven into a rivulet and clear water poured from this onto bright stones at the side of the path. Beside this was a mossy bank and I don't think any chair has ever been more comfortable or any water sweeter. I was sitting there half in heaven when an old mother and her pretty daughter climbed up the road. They found me totally exhausted and idiotically happy and they were there again in the village at the top of the hill with a brew of rice wine for me, before they brought me on to the house of the Headman of the village.

From then I was looked after in Kachin villages for nearly three months. When I reached a village and took off my boots and my ankles blew up like balloons and I would sit there till I could get my boots on again, maybe two days, sometimes three and then press on. Somewhere in the distant north there was a British outpost called Fort Hertz and this was where I was heading.

Bill's story concludes:

The swelling in my feet must have been unpleasant for others. A girl wrapped my legs in a poultice of leaves which brought out a viscous liquid with a sickly odour. I didn't like this smell myself but my hosts never complained. They never even mentioned it. I had no way of paying them and they seemed to expect nothing in return. For three months they looked after me in one village after another, always the same welcome and what they ate they also gave to me. In all those weeks I never slept again out in the open and never did without an evening meal.

Back in Burma with the second Chindit expedition the following year, we saw the distress suffered by these loyal tribesmen when Wingate was killed. To them it was a personal loss. He was I suppose, the one they looked to with his Chindit badge, the Lord Protector of the Pagodas, as they had named him. But anyway, I owe them my life after my period of deep contentment and absolute trust in a gloriously beautiful country of mountains, valleys, forests of great trees, and clear rushing streams. I'm glad to say that my six Gurkha Riflemen reached the safety of Fort Hertz long before me and were flown out safely to India.

During my research into the men who served on Operation Longcloth, I came across another Gurkha officer's story, that of Lt. Jock Stewart-Jones. In recalling his own experiences after dispersal was called in 1943, he mentions meeting Bill during the march north towards Fort Hertz. It would seem that this chance meeting and the magnificent efforts of Burma Rifleman Ah Di, would prove vital to Bill's eventual salvation:

Lt. Stewart-Jones:

I took charge of the party and averaging around 12 miles per day we pushed on to the north. We made slow progress due to the nature of the country and jungle and the men grew weak with hunger, having eaten little else than rice, bamboo leaves and roots for several weeks. As well as this, most men were suffering in a greater or lesser degree with malaria, dysentery and sceptic sores. Our clothing was in rags and a few men were without any footwear. Our journey took us as high as 5000 feet and into very cold conditions, followed almost immediately by plunging down once more into the steaming hot jungle valley.

Having no maps of the area in which we were travelling and only one compass, I had to rely on the knowledge and skill of my Kachin Jemadar, Ah Di of the Burma Rifles. His fluency in the various dialects made him invaluable in obtaining information from villagers. In the hills opposite the east of Bhamo I lost one Kachin and two Karen riflemen, who decided to take their chances and head home. It was also at this time that we picked up Lieutenant Smyly of No. 5 Column, who was in a very weak state and barely able to walk. He was left in a friendly village, with Jemadar Ah Di instructing the villagers that they would be held responsible for his safety and well-being.

Everyone was now in a very weak state, and at this time the Gurkhas were on average sticking at it better than the British soldiers and even the Burma Rifles. Through the efforts of Ah Di, we hired a Kachin guide who had once been with the Burma Frontier Force. He led us north and entered all villages first to check for Japanese patrols and to acquire rice to supplement our meagre rations. The Kachins in this area were very poor indeed and fearful of the Japs, but on the whole extremely friendly towards us.

Lt. Stewart-Jones:

I took charge of the party and averaging around 12 miles per day we pushed on to the north. We made slow progress due to the nature of the country and jungle and the men grew weak with hunger, having eaten little else than rice, bamboo leaves and roots for several weeks. As well as this, most men were suffering in a greater or lesser degree with malaria, dysentery and sceptic sores. Our clothing was in rags and a few men were without any footwear. Our journey took us as high as 5000 feet and into very cold conditions, followed almost immediately by plunging down once more into the steaming hot jungle valley.

Having no maps of the area in which we were travelling and only one compass, I had to rely on the knowledge and skill of my Kachin Jemadar, Ah Di of the Burma Rifles. His fluency in the various dialects made him invaluable in obtaining information from villagers. In the hills opposite the east of Bhamo I lost one Kachin and two Karen riflemen, who decided to take their chances and head home. It was also at this time that we picked up Lieutenant Smyly of No. 5 Column, who was in a very weak state and barely able to walk. He was left in a friendly village, with Jemadar Ah Di instructing the villagers that they would be held responsible for his safety and well-being.

Everyone was now in a very weak state, and at this time the Gurkhas were on average sticking at it better than the British soldiers and even the Burma Rifles. Through the efforts of Ah Di, we hired a Kachin guide who had once been with the Burma Frontier Force. He led us north and entered all villages first to check for Japanese patrols and to acquire rice to supplement our meagre rations. The Kachins in this area were very poor indeed and fearful of the Japs, but on the whole extremely friendly towards us.

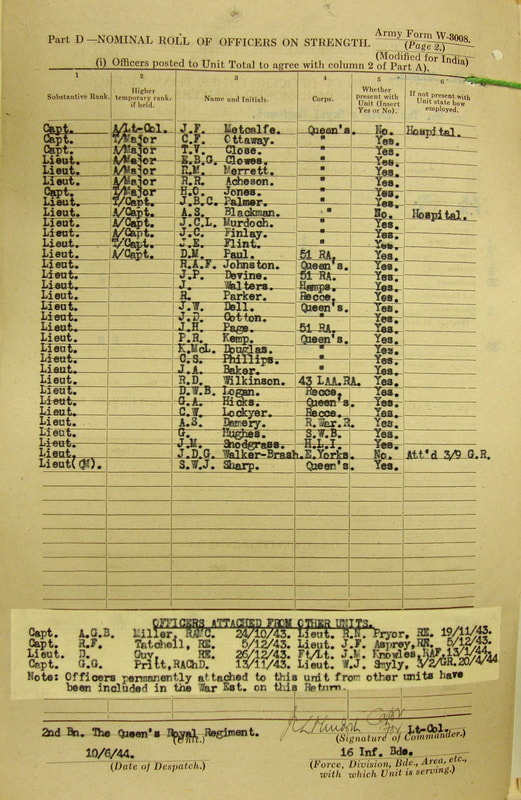

Bill Smyly was one of the few officers from Operation Longcloth to serve again on the second Wingate expedition in 1944, codenamed Operation Thursday. Once again as Animal Transport Officer, he re-joined Bernard Fergusson, this time commanding the 16th British Infantry Brigade, on their march into Burma from their starting point on the Ledo Road in February 1944. Bill was attached to the 2nd Battalion Queen's Regiment and served with them until they were flown out of Burma later, leaving behind their mules and Bill, who went on to fight with 111 Brigade under the command of Acting Brigadier Jack Masters. Bill was mentioned in despatches for his efforts during 111 Brigade's brutal engagement with the Japanese at the Chindit stronghold, codenamed Blackpool.

After the conclusion of Operation Thursday, Bill Smyly returned to the depot of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles at Dehra Dun and waited for his next posting. Two possibilities came up. One was joining V Force, of which he knew very little, and the other was a direct invitation from Brigadier Mike Calvert to join his newly formed Brigade Headquarters and take over the units Assault Company. Bill returned to the Saugor camp where the Chindits were once again in training, but nothing was to come of this venture and the Chindits were soon disbanded. Bill and his men were transferred to the 3/6th Gurkha Rifles and were sent to the Regimental Centre at Abbottabad to wait for their next assignment.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a lisitng from the pages of the 2nd Queen's War dairy showing Bill's attachment to the battalion on Operation Thursday. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After the conclusion of Operation Thursday, Bill Smyly returned to the depot of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles at Dehra Dun and waited for his next posting. Two possibilities came up. One was joining V Force, of which he knew very little, and the other was a direct invitation from Brigadier Mike Calvert to join his newly formed Brigade Headquarters and take over the units Assault Company. Bill returned to the Saugor camp where the Chindits were once again in training, but nothing was to come of this venture and the Chindits were soon disbanded. Bill and his men were transferred to the 3/6th Gurkha Rifles and were sent to the Regimental Centre at Abbottabad to wait for their next assignment.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a lisitng from the pages of the 2nd Queen's War dairy showing Bill's attachment to the battalion on Operation Thursday. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As mentioned previously, thankfully there are a number of video recordings of Bill Smyly, talking about his experiences in the Burmese jungle and his opinions on war itself. These were recorded by Chris Smyly either at Bill's home in Bedford, or at the various Chindit reunions and events:

vimeo.com/122133444

www.youtube.com/watch?v=9zTzIhgaZDM

In 2012 there was a series of documentaries on television called Narrow Escapes of World War Two. One program was dedicated to the Chindits and especially the first Wingate expedition. Bill Smyly took part in this program, recounting his own experiences in 1943:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=JP4yqSF4Oso

In November 2013, I was privileged to visit the Gurkha Rifles Museum at Winchester and allowed to view the archive material for the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles in relation to their exploits in Burma during WW2. Amongst the papers and documents I stumbled across a 14 page narrative written by Bill shortly after his return from Burma in 1943. With the permission of the museum curator (Gavin Edgerley-Harris), I was able to photograph the document with the view to transcribing it and showing it to Bill at my earliest convenience.

Having only a faint memory of actually writing the memoir some seventy-two years previously, Bill on re-reading his work, was somewhat perturbed at the boy's own high-spirited nature of the account. Nevertheless, I felt that he was interested to see it after all these years.

vimeo.com/122133444

www.youtube.com/watch?v=9zTzIhgaZDM

In 2012 there was a series of documentaries on television called Narrow Escapes of World War Two. One program was dedicated to the Chindits and especially the first Wingate expedition. Bill Smyly took part in this program, recounting his own experiences in 1943:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=JP4yqSF4Oso

In November 2013, I was privileged to visit the Gurkha Rifles Museum at Winchester and allowed to view the archive material for the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles in relation to their exploits in Burma during WW2. Amongst the papers and documents I stumbled across a 14 page narrative written by Bill shortly after his return from Burma in 1943. With the permission of the museum curator (Gavin Edgerley-Harris), I was able to photograph the document with the view to transcribing it and showing it to Bill at my earliest convenience.

Having only a faint memory of actually writing the memoir some seventy-two years previously, Bill on re-reading his work, was somewhat perturbed at the boy's own high-spirited nature of the account. Nevertheless, I felt that he was interested to see it after all these years.

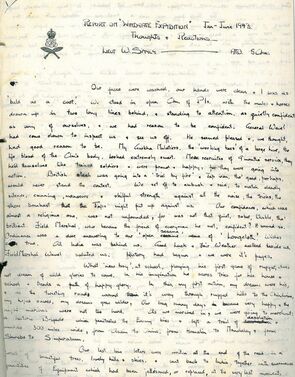

First page of Bill's actual narrative.

First page of Bill's actual narrative.

There now follows a transcription of Bill Smyly's Longcloth narrative, with the original written upon fourteen pages of Gurkha Rifles headed paper:

Introduction

Every man in an adventure must have some measure of success and some of failure. I have tried to give an account of my own adventures honestly. The things I was proud of and the things I was not. Also, without any comment, the thoughts that were running though my mind.

We started off with high spirits and enthusiasm. These gave place to grim determination to fight in spite, and not because, of our force and its organisation. With our vitality, even this flagged. Some men turned to cowards, a very few to heroes, but in the mind of every man the thought, “We must get out, we must get back,” had given place to the enthusiasm which cried, “Kill, fight and win."

Memories and photographs of sweethearts and wives kept dead men staggering on their feet. There was a lot of suffering and hundreds failed to comeback. After it all, what did we actually accomplish? Perhaps we were a very useful experiment. Perhaps the science of war learned more from our mistakes than any successes. I have written in an auto-biographical form as the subject must have been very clearly dealt with in other accounts and I set out to give my own thoughts, as they are probably as typical as any.

Report on the Wingate Expedition January-June 1943.

Thoughts and Reactions, Lieut. W. Smyly, ATO, 5 Column.

Our faces were washed, our hands were clean and I was as ‘bald as a coot.' We stood in open platoon formation with the mules and horses drawn up in two long lines behind, and standing to attention, as quietly confident as any of ourselves, and we had reason to be confident.

General Wavell had come down to inspect us and see us off. He seemed pleased and we thought he had good reason to be. My Gurkha Muleteers, the ‘working bees’ of a large hive, the lifeblood of the Column's body, looked extremely smart. New recruits of 9 months service, they held themselves like trained soldiers and were proud and happy, for they were going into action. British steel was going into a ‘trial by fire’ and Jap iron, though good, perhaps would never stand the contest.

We set off to ambush and raid, to match deadly silence, cunning, manoeuvre and skilful strength, against all the noise, the tricks, and the sheer bombast that the Japs might put up against us. Our confidence, which was almost a religious one, was not unfounded, for was not that quiet, sober, likeable, though brilliant Field Marshall, who became the friend of everyman he met, confident? It seemed so. Ordinance was a door answering to our ‘open sesame’ in the name of Longcloth. Wishes come true. All India was behind us. Good luck and fair weather walked beside us. Field Marshall Wavell saluted us. History had begun and we were its pages.

What new boy at school, playing his first game of rugger, does not dream of wild glories to come? In his imagination he scores tries for his house and school and treads a path of happy glory. In this, my first action, my dreams were his and as the twisting roads wound their way through the rugged hills to the Chindwin, my hopes soared, my dreams grew wilder, our long sunny days became very happy and the night marches were not too hard.

As we marched in; so we were going to march out: a historic Brigade which penetrated the enemy lines and left a trail of desolation and muddle 300 miles wide, from Assam to China, from Homalin to Mandalay and from Shwebo to Sumprabum. Our last love letters were written at the end of the road in a forest of beautiful trees, lovely hills and skies and sent back to India, together with enormous quantities of equipment which had to be jettisoned, or replaced at the very last moment. And which, because we were hurrying, had been left behind in huge disorderly heaps.

The track from now was a small one and littered with skulls, the bones and the clothing of some who had hoped to escape not a year before. Against one tree was a heap of bones and women’s clothing, with a tiny skull beside. They could sink contentedly into the earth now for their job was done; a whole Brigade had marched past them and had been shown that each man’s job was to revenge the horrors that this track had a year ago.

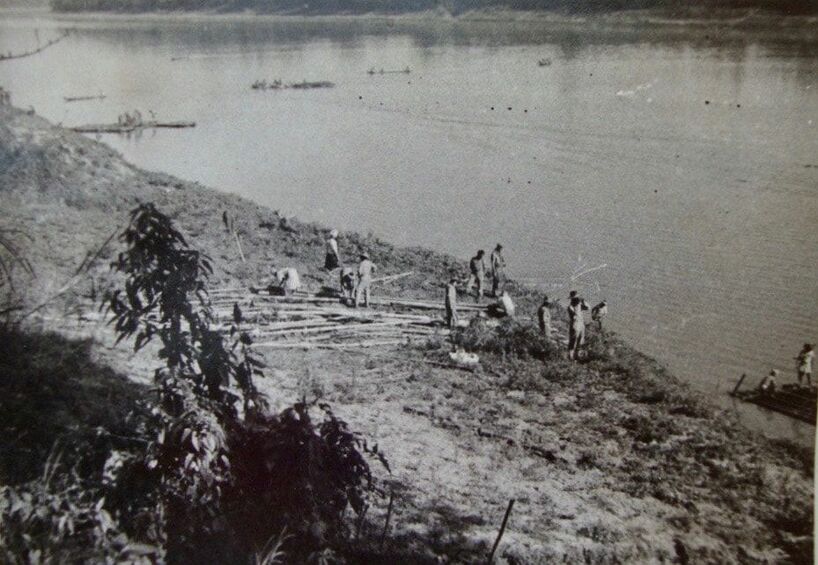

The Chindwin was crossed without much difficulty, for we took two ropes across at night and ferried over the river, hand over hand, in Royal Engineer boats, like huge inner tubes with a canvas floor, or rafts supported by the tiny RAF boats, which float but are not much use for anything else. The mules and horses which were fit, swam across in droves, the fearful ones going across tied to our RE boats and the willing ones going over in droves of 15 to 20 at a time. I was the last across, because the animals were my property, but, after a long and gloriously happy day, working in naked in the baking sun, I dispatched my saddle and clothes with the Groom, tied up my reins to a surcingle and rode across on Sambo’s back.

He was a beautiful prancing gelding of 16 hands and a half, and was one of the finest, strongest beasts I have ever seen. He swam with his head held high and the water surged round his flanks, swirled round my legs and his long tail trailed out in his wake. We caught up and passed an RE boat and seemed to be going twice as fast. It was dark by then and we planned a night march, but they are quite impossible in the jungle and, having struggled on for about a quarter of a mile in 2 hours we halted and slept in single file or ‘column snake’ as we called it. This was a formation with many disadvantages, as we were to find out later, the only possible one however for getting over this type of country we were in.

Next day we formed up in a Brigade RV and had a ration dropping, not a very successful one however, for our tins were dropped into soft paddy fields and many were lost. From here the jungle was flat open teak forest, the ground covered by tiny plants with huge dry papery leaves, and here and there young bendy saplings under the shady roof of giant teak.

Our only difficulty was long thin lanes of ooze and rushes. They might have been streams once, but were now just squashy mud over which paths had to be found or made. Sometimes thick carpets of rushes were enough but often timber had to be cut to reinforce it. Often alternative paths had to be made, loaded mules would fall and have to be unloaded in the middle of a quagmire into which they were sinking, whilst others would have to be unloaded in order to get them across at all. It was the quiet ones that did best, those that tried to rush went down. The only thing that got over everything was the quiet, plodding, pack bullock, which when saddled with a mule saddle was invaluable.

Introduction

Every man in an adventure must have some measure of success and some of failure. I have tried to give an account of my own adventures honestly. The things I was proud of and the things I was not. Also, without any comment, the thoughts that were running though my mind.

We started off with high spirits and enthusiasm. These gave place to grim determination to fight in spite, and not because, of our force and its organisation. With our vitality, even this flagged. Some men turned to cowards, a very few to heroes, but in the mind of every man the thought, “We must get out, we must get back,” had given place to the enthusiasm which cried, “Kill, fight and win."

Memories and photographs of sweethearts and wives kept dead men staggering on their feet. There was a lot of suffering and hundreds failed to comeback. After it all, what did we actually accomplish? Perhaps we were a very useful experiment. Perhaps the science of war learned more from our mistakes than any successes. I have written in an auto-biographical form as the subject must have been very clearly dealt with in other accounts and I set out to give my own thoughts, as they are probably as typical as any.

Report on the Wingate Expedition January-June 1943.

Thoughts and Reactions, Lieut. W. Smyly, ATO, 5 Column.

Our faces were washed, our hands were clean and I was as ‘bald as a coot.' We stood in open platoon formation with the mules and horses drawn up in two long lines behind, and standing to attention, as quietly confident as any of ourselves, and we had reason to be confident.

General Wavell had come down to inspect us and see us off. He seemed pleased and we thought he had good reason to be. My Gurkha Muleteers, the ‘working bees’ of a large hive, the lifeblood of the Column's body, looked extremely smart. New recruits of 9 months service, they held themselves like trained soldiers and were proud and happy, for they were going into action. British steel was going into a ‘trial by fire’ and Jap iron, though good, perhaps would never stand the contest.

We set off to ambush and raid, to match deadly silence, cunning, manoeuvre and skilful strength, against all the noise, the tricks, and the sheer bombast that the Japs might put up against us. Our confidence, which was almost a religious one, was not unfounded, for was not that quiet, sober, likeable, though brilliant Field Marshall, who became the friend of everyman he met, confident? It seemed so. Ordinance was a door answering to our ‘open sesame’ in the name of Longcloth. Wishes come true. All India was behind us. Good luck and fair weather walked beside us. Field Marshall Wavell saluted us. History had begun and we were its pages.

What new boy at school, playing his first game of rugger, does not dream of wild glories to come? In his imagination he scores tries for his house and school and treads a path of happy glory. In this, my first action, my dreams were his and as the twisting roads wound their way through the rugged hills to the Chindwin, my hopes soared, my dreams grew wilder, our long sunny days became very happy and the night marches were not too hard.

As we marched in; so we were going to march out: a historic Brigade which penetrated the enemy lines and left a trail of desolation and muddle 300 miles wide, from Assam to China, from Homalin to Mandalay and from Shwebo to Sumprabum. Our last love letters were written at the end of the road in a forest of beautiful trees, lovely hills and skies and sent back to India, together with enormous quantities of equipment which had to be jettisoned, or replaced at the very last moment. And which, because we were hurrying, had been left behind in huge disorderly heaps.

The track from now was a small one and littered with skulls, the bones and the clothing of some who had hoped to escape not a year before. Against one tree was a heap of bones and women’s clothing, with a tiny skull beside. They could sink contentedly into the earth now for their job was done; a whole Brigade had marched past them and had been shown that each man’s job was to revenge the horrors that this track had a year ago.

The Chindwin was crossed without much difficulty, for we took two ropes across at night and ferried over the river, hand over hand, in Royal Engineer boats, like huge inner tubes with a canvas floor, or rafts supported by the tiny RAF boats, which float but are not much use for anything else. The mules and horses which were fit, swam across in droves, the fearful ones going across tied to our RE boats and the willing ones going over in droves of 15 to 20 at a time. I was the last across, because the animals were my property, but, after a long and gloriously happy day, working in naked in the baking sun, I dispatched my saddle and clothes with the Groom, tied up my reins to a surcingle and rode across on Sambo’s back.

He was a beautiful prancing gelding of 16 hands and a half, and was one of the finest, strongest beasts I have ever seen. He swam with his head held high and the water surged round his flanks, swirled round my legs and his long tail trailed out in his wake. We caught up and passed an RE boat and seemed to be going twice as fast. It was dark by then and we planned a night march, but they are quite impossible in the jungle and, having struggled on for about a quarter of a mile in 2 hours we halted and slept in single file or ‘column snake’ as we called it. This was a formation with many disadvantages, as we were to find out later, the only possible one however for getting over this type of country we were in.

Next day we formed up in a Brigade RV and had a ration dropping, not a very successful one however, for our tins were dropped into soft paddy fields and many were lost. From here the jungle was flat open teak forest, the ground covered by tiny plants with huge dry papery leaves, and here and there young bendy saplings under the shady roof of giant teak.

Our only difficulty was long thin lanes of ooze and rushes. They might have been streams once, but were now just squashy mud over which paths had to be found or made. Sometimes thick carpets of rushes were enough but often timber had to be cut to reinforce it. Often alternative paths had to be made, loaded mules would fall and have to be unloaded in the middle of a quagmire into which they were sinking, whilst others would have to be unloaded in order to get them across at all. It was the quiet ones that did best, those that tried to rush went down. The only thing that got over everything was the quiet, plodding, pack bullock, which when saddled with a mule saddle was invaluable.

Bill's narrative continues:

We did long marches here, but went very slowly, learning from experiences what to do and not to do. Learning our jungle discipline. Contenting ourselves with present boredom by thoughts of coming adventure. Our next air dropping was six days after the first, for a time I acted as mounted runner, but did not enjoy it, as Sambo was used to good meals of grain and the grain was done. I used to give him a biscuit sometimes, but could not spare enough, there was a chunk of rock salt I kept in my pocket for him to lick, but felt that this had only increased his longing for it. He still looked magnificent and quite fit, but a short canter would tire him now. He still had his hard round muscles, but his ears were not as intelligently cocked and the brightness had gone from his eyes. Well, we were all going in to do a great job, we would all suffer together, but the prize was worth winning and “Sambo, when you get out you’ll live like a King, I’ll take you to Dehra Doon if they let me buy you." But Sambo never knew these wonderful things, he only knew he was tired and hungry and there was nothing to eat.

Because of my passive role and the fact that I wanted to do something, I was sent off to guard a crossroads leading into our valley. With ten men I set off and had three days of happy quiet pleasure. There was a place, not far away, where even the largest fire could never be seen, so we had tea boiling almost all night and in the day moved the post forward about a mile to bathe, wash clothes and make huge bamboo water bottles for our waterless post.

Then, on we went again and learned the disadvantages of Column snake, for in a land with the smallest of pathways we would stretch out to a mile or more in length and a slow steady pace in front, would turn to a galloping run behind and men, with two mules to lead, at the back of a long Column, had a very hard life.

When we went in, the first show had already been planned. It was an easy one and designed to give us confidence. Three Columns were to have attacked two small garrisoned towns, the smaller one being attacked, then the reinforcements sent out by the other larger town were to be ambushed; then the larger town attacked. Reinforcements, it was hoped, would be rushed up by train and my Column would either blow them up on a bridge or dislodge half a mountain on top of them as they ran through a cutting. Japanese dispositions changed however and nothing came of the show.

As a matter of fact we did blow up the bridge and also dislodge a minor landslide into our railway cutting. At every show I was allowed to send a body guard of Gurkhas forward, we did meet the Japs rather unexpectedly. My ten men killed eleven Japs and lost one man. Maula Bahadur, whose bravery inspired everyone, as, with a wound in the chest and gargling blood, he marched two miles and when he was being tended by the Doctor (Bill Aird), protested that he was coming on with us in the Column. From that day my small band of recruits, took, or seemed to me to take, a greater pride in everything they did.

Among the British troops there were a number of men killed and some wounded that needed to be left behind in a village (Kyaik-in) and some who came on. I saw the Doctor taking shrapnel from a man’s leg; it was a piece of British grenade. Our food was very low now and we had to rely entirely on supplies of rice, chickens, paddy and perhaps a few vegetables. When we slaughtered a cow there were enough of us to do it justice.

On the banks of the Irrawaddi there is a little steamer station called Tigyang, which we marched into one morning. In the town we bought and indeed we were given, enormous quantities of sugar, salt, fruit, rice and sweets. English cigarettes were going for 8 annas each, but they gave us as many Burmese cheroots as we could carry. Over 50 boats were employed to take us across and on the shore I had a hard job to load them fast enough, for, as ATO (Animal Transport Officer), river crossing was almost the only time that I had anything reasonable to do.

Later, I rode up on Sambo, who had just had a good feed of paddy, salt and milk to report to my O.C. (Bernard Fergusson). He was in the town and talking to an old man, a postmaster from the time of British rule. He told of the miseries and trouble that he and his daughter had been through. He gave us his card, which has subsequently been sent off to His Majesties Private Secretary and ended his speech by standing to attention and saying most fervently “God Save the King, Long Live the King." He stood at the doors of his own house and one of the most beautiful women I have ever seen stood smiling in an upstairs window. She leaned out and waved to us.

Having reported to my Major and waved back at the girl, he handed me a bit of paper. It was, of all things, a Jap leaflet written in several languages and telling us that our officers would desert us as they had done before. It told us to leave these self-seeking faithless tyrants, report to the nearest village and go off to a Jap prison where there was food and drink for us. I did not wait till the end this time and pushed off out of the town with my mules and wireless units, which were the vulnerable part of our column. We must have been just in time, for the Japs arrived as the last four people tumbled into a boat and crossed under an umbrella of fire from Japanese LMG’s (light machine guns) on one bank and the long defence bursts of our two Vickers on the other.

Reaching the bivouac area, officers were given the order, ‘500 feet on 60 degrees and close on the bugle’, which meant that every man walked off the track on bearing 60 degrees for about 500 feet, then a bugle started blowing the note G and we closed in on it. A very effective way, though I find great difficulty in working out where the bugle is, as the noise dances about to the left and the right, sometimes in front and sometimes behind. From now we had left the land of villages and had to rely on our rations. The supplies we picked up ‘ad lib’ in Tigyang proved invaluable, for we had to live on them for a week. During that week we did not march very hard and normally got enough water though the country was dry. In these days our jungle craft improved by leaps and bounds. We learned what roots, leaves and berries could be eaten, how to cook snakes, monkeys and the obscure parts of a cow, such as its intestines or bowels. We even made up rhymes such as this:

When elephant shite is hard and horny

It’s not been farting over ‘pawni’

When elephant shite is soft and moist

Then you’ll find water to quench your ‘toist’.

A Column which is not doing very much is rather like a family. It has its laughter, its jokes, its comradeship, but it also has its minor annoyances and troubles. A weak minded man may eat all his rations up and, because he can’t be left to starve, the others must give him food even though they are short themselves already. Everyman had a little money and British Other Rank’s may go around trying to buy food from Gurkhas at the price of 5 rupees for one biscuit. On the whole however, we were still fairly content and the next ration drop of five days rations plus our mail cheered us up immensely. I myself got a Christmas card and a letter from my parents, which, by exceptional postal brilliance was nearly two years old, a love letter which thought that I was on leave and complained bitterly that I had not gone to see her, a bill and a bank statement.

We also got food for our animals. I had 35 lbs. of mixed grain for my horse and made a very large boiled feed in a ration tin containing the grain and a good deal of paddy. The poor beast was very thin now. His ribs were showing and I had two blankets under the saddle and the girth had come up four holes. His quarters were hollow and sunken, his face gaunt, his eyes lifeless and his head hung low. I never rode him from that day, but he went on wasting away.

When our five days rations were nearly finished we told Brigade HQ, who had already had two more droppings than we had, that we wanted food, but received the message “It is necessary that one should die for the people." We were the forward Column and had hung about on the banks of the Shweli for several days, which, apart from the food situation was not unpleasant. We went hunting, washed and mended our clothes and bathed. I had a copy of the Spectator which was in tremendous demand.

Every evening we would move a few miles away from the river for safety, but the main part of the day was on our hands and would have been very contented and peaceful if we had been less hungry. Then came permission for another air dropping. Leaving our bivouac we headed south and every half mile or so one section of the Column swung north east and then north, so that, should anyone try to follow us, he would have been very lucky to have gone the right way. We were now, I felt, trained and ready for action, give us a few good meals and we’d be OK.

We did long marches here, but went very slowly, learning from experiences what to do and not to do. Learning our jungle discipline. Contenting ourselves with present boredom by thoughts of coming adventure. Our next air dropping was six days after the first, for a time I acted as mounted runner, but did not enjoy it, as Sambo was used to good meals of grain and the grain was done. I used to give him a biscuit sometimes, but could not spare enough, there was a chunk of rock salt I kept in my pocket for him to lick, but felt that this had only increased his longing for it. He still looked magnificent and quite fit, but a short canter would tire him now. He still had his hard round muscles, but his ears were not as intelligently cocked and the brightness had gone from his eyes. Well, we were all going in to do a great job, we would all suffer together, but the prize was worth winning and “Sambo, when you get out you’ll live like a King, I’ll take you to Dehra Doon if they let me buy you." But Sambo never knew these wonderful things, he only knew he was tired and hungry and there was nothing to eat.

Because of my passive role and the fact that I wanted to do something, I was sent off to guard a crossroads leading into our valley. With ten men I set off and had three days of happy quiet pleasure. There was a place, not far away, where even the largest fire could never be seen, so we had tea boiling almost all night and in the day moved the post forward about a mile to bathe, wash clothes and make huge bamboo water bottles for our waterless post.

Then, on we went again and learned the disadvantages of Column snake, for in a land with the smallest of pathways we would stretch out to a mile or more in length and a slow steady pace in front, would turn to a galloping run behind and men, with two mules to lead, at the back of a long Column, had a very hard life.

When we went in, the first show had already been planned. It was an easy one and designed to give us confidence. Three Columns were to have attacked two small garrisoned towns, the smaller one being attacked, then the reinforcements sent out by the other larger town were to be ambushed; then the larger town attacked. Reinforcements, it was hoped, would be rushed up by train and my Column would either blow them up on a bridge or dislodge half a mountain on top of them as they ran through a cutting. Japanese dispositions changed however and nothing came of the show.

As a matter of fact we did blow up the bridge and also dislodge a minor landslide into our railway cutting. At every show I was allowed to send a body guard of Gurkhas forward, we did meet the Japs rather unexpectedly. My ten men killed eleven Japs and lost one man. Maula Bahadur, whose bravery inspired everyone, as, with a wound in the chest and gargling blood, he marched two miles and when he was being tended by the Doctor (Bill Aird), protested that he was coming on with us in the Column. From that day my small band of recruits, took, or seemed to me to take, a greater pride in everything they did.

Among the British troops there were a number of men killed and some wounded that needed to be left behind in a village (Kyaik-in) and some who came on. I saw the Doctor taking shrapnel from a man’s leg; it was a piece of British grenade. Our food was very low now and we had to rely entirely on supplies of rice, chickens, paddy and perhaps a few vegetables. When we slaughtered a cow there were enough of us to do it justice.

On the banks of the Irrawaddi there is a little steamer station called Tigyang, which we marched into one morning. In the town we bought and indeed we were given, enormous quantities of sugar, salt, fruit, rice and sweets. English cigarettes were going for 8 annas each, but they gave us as many Burmese cheroots as we could carry. Over 50 boats were employed to take us across and on the shore I had a hard job to load them fast enough, for, as ATO (Animal Transport Officer), river crossing was almost the only time that I had anything reasonable to do.

Later, I rode up on Sambo, who had just had a good feed of paddy, salt and milk to report to my O.C. (Bernard Fergusson). He was in the town and talking to an old man, a postmaster from the time of British rule. He told of the miseries and trouble that he and his daughter had been through. He gave us his card, which has subsequently been sent off to His Majesties Private Secretary and ended his speech by standing to attention and saying most fervently “God Save the King, Long Live the King." He stood at the doors of his own house and one of the most beautiful women I have ever seen stood smiling in an upstairs window. She leaned out and waved to us.

Having reported to my Major and waved back at the girl, he handed me a bit of paper. It was, of all things, a Jap leaflet written in several languages and telling us that our officers would desert us as they had done before. It told us to leave these self-seeking faithless tyrants, report to the nearest village and go off to a Jap prison where there was food and drink for us. I did not wait till the end this time and pushed off out of the town with my mules and wireless units, which were the vulnerable part of our column. We must have been just in time, for the Japs arrived as the last four people tumbled into a boat and crossed under an umbrella of fire from Japanese LMG’s (light machine guns) on one bank and the long defence bursts of our two Vickers on the other.

Reaching the bivouac area, officers were given the order, ‘500 feet on 60 degrees and close on the bugle’, which meant that every man walked off the track on bearing 60 degrees for about 500 feet, then a bugle started blowing the note G and we closed in on it. A very effective way, though I find great difficulty in working out where the bugle is, as the noise dances about to the left and the right, sometimes in front and sometimes behind. From now we had left the land of villages and had to rely on our rations. The supplies we picked up ‘ad lib’ in Tigyang proved invaluable, for we had to live on them for a week. During that week we did not march very hard and normally got enough water though the country was dry. In these days our jungle craft improved by leaps and bounds. We learned what roots, leaves and berries could be eaten, how to cook snakes, monkeys and the obscure parts of a cow, such as its intestines or bowels. We even made up rhymes such as this:

When elephant shite is hard and horny

It’s not been farting over ‘pawni’

When elephant shite is soft and moist

Then you’ll find water to quench your ‘toist’.

A Column which is not doing very much is rather like a family. It has its laughter, its jokes, its comradeship, but it also has its minor annoyances and troubles. A weak minded man may eat all his rations up and, because he can’t be left to starve, the others must give him food even though they are short themselves already. Everyman had a little money and British Other Rank’s may go around trying to buy food from Gurkhas at the price of 5 rupees for one biscuit. On the whole however, we were still fairly content and the next ration drop of five days rations plus our mail cheered us up immensely. I myself got a Christmas card and a letter from my parents, which, by exceptional postal brilliance was nearly two years old, a love letter which thought that I was on leave and complained bitterly that I had not gone to see her, a bill and a bank statement.

We also got food for our animals. I had 35 lbs. of mixed grain for my horse and made a very large boiled feed in a ration tin containing the grain and a good deal of paddy. The poor beast was very thin now. His ribs were showing and I had two blankets under the saddle and the girth had come up four holes. His quarters were hollow and sunken, his face gaunt, his eyes lifeless and his head hung low. I never rode him from that day, but he went on wasting away.

When our five days rations were nearly finished we told Brigade HQ, who had already had two more droppings than we had, that we wanted food, but received the message “It is necessary that one should die for the people." We were the forward Column and had hung about on the banks of the Shweli for several days, which, apart from the food situation was not unpleasant. We went hunting, washed and mended our clothes and bathed. I had a copy of the Spectator which was in tremendous demand.

Every evening we would move a few miles away from the river for safety, but the main part of the day was on our hands and would have been very contented and peaceful if we had been less hungry. Then came permission for another air dropping. Leaving our bivouac we headed south and every half mile or so one section of the Column swung north east and then north, so that, should anyone try to follow us, he would have been very lucky to have gone the right way. We were now, I felt, trained and ready for action, give us a few good meals and we’d be OK.

Bill continues his story:

All the expectancy and enthusiasm had gone, but there was a grim will to go on and we had the same faith in ourselves that we had had when General Wavell saw us off. The air dropping came, bringing equipment, rum and Bully, but very little of the actual rations which we needed more than anything. We had two days rations, but were happy even to have that, for we had been living on one fifth of the normal half scale rations for the past week and we were able to add nothing to it except a cow and a mule.

For the Gurkhas there were large tins of tinned mutton and some of them kept the meat through the heat of a long day and got badly poisoned. Three of them fell out together, said it was the Devil’s revenge for their eating cow and one Lance Naik refused to move until he found the Doctor’s pistol pointing at him. More men (all of them Gurkhas) fell out, it seemed like an epidemic, the Jemadar thought that it was a very infectious disease that breaks out in dirty villages in Nepal and wanted the men isolated; the Doctor said that he couldn’t cure people in the jungle if they wouldn’t even try.

Four men were sick at night, three more next morning and more during the course of the day. I put them on horses, on mules and one had to go on a stretcher. That night I told them the news of the other Columns and also what the British Other Ranks were saying about them, ‘What sort of men are these Gurkhas?’ In action there are no braver anywhere, look at Maula Bahadur when he was dying of wounds, yet when some little thing goes wrong, when they are sick, they are cowards.’

I tried to tell them about the Englishman’s implicit faith in his Doctor, of our infallible Medical Officer and what he could do to people who would help him and behave like soldiers. The Jemadar went over the whole thing after me, reading from my notes. The next day I saw our M.O. and said ‘You’re God.’ He replied, ‘Oh! Is that what it is? I thought your lads were trying a bit harder.’

Shortly after this we formed up at a Brigade R.V. and were told that we had done our job and had to go home, what we had done nobody knew. It is never much fun to be a failure and we had been a long way from success. In addition the Japanese was misbehaving and we were worried. Amazing orders (rumours) started floating about. One was that animals should have their mouths tied up with rope at night so that they couldn’t cry. It only succeeded in making them so they could not eat, they could still cry as loud as ever. A ‘no chopping’ order forbade men to feed their animals as the chopping of bamboo made too much noise, though this struck me as peculiar after the difficulty I had found in following a bugle and the fact that, as I knew to my cost, the jungle will even deaden the blast of a whistle remarkably suddenly.

Then the great blow came, we were going back to India. All equipment was to be dropped, mules killed and we were to get back as quick as we could. It sounded to me like an order of ‘Everyman for himself’, and indeed there are those who took it as such. Setting off as a Brigade Column, we marched very slowly for about six hours. At first I took out my badly galled mules and shot them with a rifle, a difficult and in some cases, most sickening thing to have to do. In a ten-minute halt I shot thirty mules, but fired thirty-seven rounds. Other mules I turned loose, as a mule with any gall may easily learn to live in the jungle, whereas one with a fly blown sore would be eaten away and die.

Then orders came ‘no more shooting.’ I asked my Jemadar if the Gurkhas could kill them with kukris, but he said it was impossible and could not be done, later I heard an Officer, more sure of himself than I, order a mule to be killed that way and it was done very well and quickly. I ordered the use of bayonets, sticking one 4 inches into an animal’s forehead and another from temple to temple. The first did not even notice it, the second looked stunned and drunk. A mule has such a friendly face, one gets to know him so well that this foul act of butchery is far more frightful than it sounds.

Later that day the whole Brigade was attacked in the bed of a tiny river and although no one was killed, I had the pleasure of knowing that my firing had been the cause of it. To avoid pursuit my Column led the enemy off one way, while the Brigade escaped by another. Our plan was to make a fake bivouac with lots of fires and one or two mules tied up to cry out and add realism. This we did; leaving the area covered by a thousand booby-traps and retreated down a dry nula or chong. Everything would have been fine had the maps been true, but they were not. Our chong was quite impassable and we were trapped in a cul-de-sac, walled in on all sides by dense jungle. After two hours rest we found a small track, it was the only way out and we took it, took our chances and were ambushed.

NB. I believe Bill is talking about the action around the village of Hintha on the 28/29th March 1943. In effect this engagement with the Japanese, which was a series of short battles at close quarters, was the beginning of the disintegration of No. 5 Column. At the second ambush in the dry river bed, one hundred men became separated from the main body of the column, leaving just 120 Chindits still under Major Fergusson's command.

All the expectancy and enthusiasm had gone, but there was a grim will to go on and we had the same faith in ourselves that we had had when General Wavell saw us off. The air dropping came, bringing equipment, rum and Bully, but very little of the actual rations which we needed more than anything. We had two days rations, but were happy even to have that, for we had been living on one fifth of the normal half scale rations for the past week and we were able to add nothing to it except a cow and a mule.

For the Gurkhas there were large tins of tinned mutton and some of them kept the meat through the heat of a long day and got badly poisoned. Three of them fell out together, said it was the Devil’s revenge for their eating cow and one Lance Naik refused to move until he found the Doctor’s pistol pointing at him. More men (all of them Gurkhas) fell out, it seemed like an epidemic, the Jemadar thought that it was a very infectious disease that breaks out in dirty villages in Nepal and wanted the men isolated; the Doctor said that he couldn’t cure people in the jungle if they wouldn’t even try.

Four men were sick at night, three more next morning and more during the course of the day. I put them on horses, on mules and one had to go on a stretcher. That night I told them the news of the other Columns and also what the British Other Ranks were saying about them, ‘What sort of men are these Gurkhas?’ In action there are no braver anywhere, look at Maula Bahadur when he was dying of wounds, yet when some little thing goes wrong, when they are sick, they are cowards.’

I tried to tell them about the Englishman’s implicit faith in his Doctor, of our infallible Medical Officer and what he could do to people who would help him and behave like soldiers. The Jemadar went over the whole thing after me, reading from my notes. The next day I saw our M.O. and said ‘You’re God.’ He replied, ‘Oh! Is that what it is? I thought your lads were trying a bit harder.’

Shortly after this we formed up at a Brigade R.V. and were told that we had done our job and had to go home, what we had done nobody knew. It is never much fun to be a failure and we had been a long way from success. In addition the Japanese was misbehaving and we were worried. Amazing orders (rumours) started floating about. One was that animals should have their mouths tied up with rope at night so that they couldn’t cry. It only succeeded in making them so they could not eat, they could still cry as loud as ever. A ‘no chopping’ order forbade men to feed their animals as the chopping of bamboo made too much noise, though this struck me as peculiar after the difficulty I had found in following a bugle and the fact that, as I knew to my cost, the jungle will even deaden the blast of a whistle remarkably suddenly.

Then the great blow came, we were going back to India. All equipment was to be dropped, mules killed and we were to get back as quick as we could. It sounded to me like an order of ‘Everyman for himself’, and indeed there are those who took it as such. Setting off as a Brigade Column, we marched very slowly for about six hours. At first I took out my badly galled mules and shot them with a rifle, a difficult and in some cases, most sickening thing to have to do. In a ten-minute halt I shot thirty mules, but fired thirty-seven rounds. Other mules I turned loose, as a mule with any gall may easily learn to live in the jungle, whereas one with a fly blown sore would be eaten away and die.

Then orders came ‘no more shooting.’ I asked my Jemadar if the Gurkhas could kill them with kukris, but he said it was impossible and could not be done, later I heard an Officer, more sure of himself than I, order a mule to be killed that way and it was done very well and quickly. I ordered the use of bayonets, sticking one 4 inches into an animal’s forehead and another from temple to temple. The first did not even notice it, the second looked stunned and drunk. A mule has such a friendly face, one gets to know him so well that this foul act of butchery is far more frightful than it sounds.

Later that day the whole Brigade was attacked in the bed of a tiny river and although no one was killed, I had the pleasure of knowing that my firing had been the cause of it. To avoid pursuit my Column led the enemy off one way, while the Brigade escaped by another. Our plan was to make a fake bivouac with lots of fires and one or two mules tied up to cry out and add realism. This we did; leaving the area covered by a thousand booby-traps and retreated down a dry nula or chong. Everything would have been fine had the maps been true, but they were not. Our chong was quite impassable and we were trapped in a cul-de-sac, walled in on all sides by dense jungle. After two hours rest we found a small track, it was the only way out and we took it, took our chances and were ambushed.

NB. I believe Bill is talking about the action around the village of Hintha on the 28/29th March 1943. In effect this engagement with the Japanese, which was a series of short battles at close quarters, was the beginning of the disintegration of No. 5 Column. At the second ambush in the dry river bed, one hundred men became separated from the main body of the column, leaving just 120 Chindits still under Major Fergusson's command.

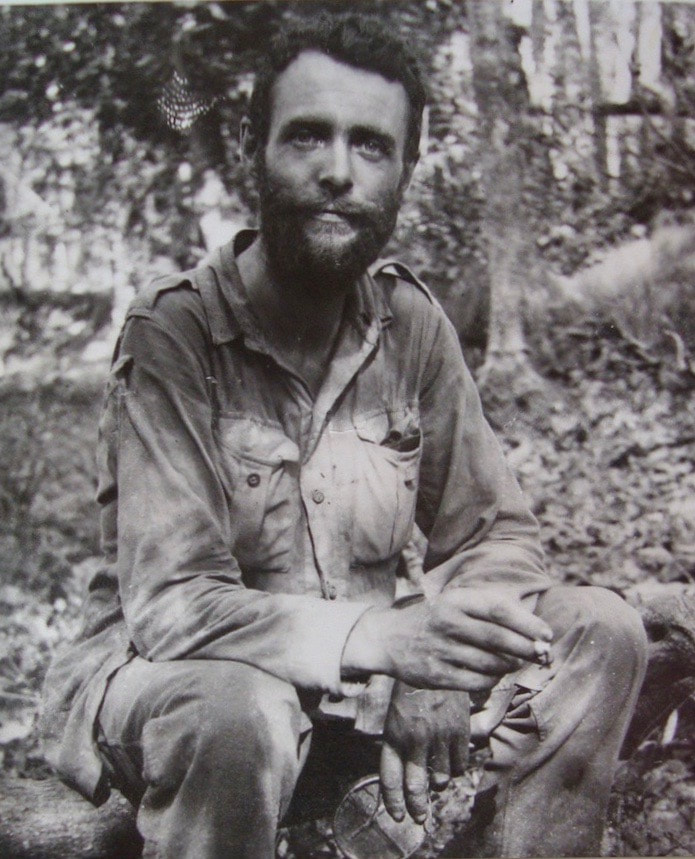

A young Bill Smyly in Army uniform.

A young Bill Smyly in Army uniform.

Returning to Bill's narrative:

Much must have been written about Japanese methods of war by people far better qualified to speak. I saw nothing, but heard a very great deal. The Jap is a great lover of noise, and adds to the noise of hundreds of un-aimed rounds and bursts, by using Chinese crackers, they sounded like very heavy mortar fire, but I comforted myself and as convincingly as I could, my men, that they were not mortars.

We sent in a couple of platoons with bayonets to attack people who then vanished, while others set up a demon-like screaming. They seemed to be trained to scream and no mass torturing by the Spanish Inquisition, nor the wildest demon souls in hell could have beaten their cries. Naturally diverting our attentions to the screamers, most of whom were either silenced or gave a good reason to continue; we did not notice the men with LMG’s (light machine guns) who walked up boldly under the shade of the trees. The time was 0200hrs. and there was a moon; they opened up on us from a very close range. They were charged at once, but melted away as easily as they had come up.

I had taken my mule back slightly and had grouped them all together; got my Order group round me and sent one British soldier off to report to the Major and act as runner. He did not get there and I doubt if he tried. I then went to sleep, not because I wanted to, but because I was sitting down and just slipped off. I was asleep for about an hour and woke up to hear the noise of elephants trumpeting and their bells ringing wildly as if they were stampeding. The firing was spasmodic but very intense in these spasms. Several wounded men were coming back and it was stated that several men had been shot. A Gurkha LMG was wanted, so I sent up a gun with its crew and an intelligent Naik to command the crew. Our second dispersal signal on the bugle was a long and very beautiful call; from the spasm of fire that it caused, I should not have enjoyed standing in, or indeed anywhere near the bugler’s boots. It was sounded just as the first pink of dawn was beginning to show. The dispersal means that we split up into small groups; vanish and re-appear again at some place at some pre-arranged time.

I told my Jemadar to lead all the Gurkhas down the track while I stood at the end of it and collected them as they filed past me in the jostling stream of people. It may have been due to my poor Kasqura (?), even poorer when I am excited, or it may have been just the excitement and panic of those who did not know what was happening and were guessing, but my Jemadar asked a British Other Rank what was going on; learned that we were all clearing off into the jungle because we could not go on and then cleared off himself.

Only twenty-seven men passed me, but I went off with them. Brigade HQ, without informing anyone, changed its RV with the result that most of the Column got lost and went back to India in small groups. I, however, by a brilliant stroke of bad map reading walked slap into the new RV just as Brigade were marching out. We marched all that night but covered very little ground as most of the night we moved little faster than a cinema queue, though when we were moving we were at the double. By morning we found that the carefully planned Brigade crossing of the Irrawaddi had been foiled and we were to break up into small groups and get back as best we could. It was here that people’s nerves got frayed; we were stuck in the ‘Shweli pocket’ with rivers on three sides and the Japs closing in from the south. I did not think of this however, for my platoon had marched for 50 hours without sleep, and had had just 10 hours sleep in the last 100.

I was in the ‘Shweli pocket’ for about a week after the foiled crossing of the Irrawaddi. We had one small ration drop, but though I dashed everywhere and saw 3 Column Command, their 2/IC’s, their ration officers and heaven knows how many others; it was only by telling my men that if they did not hurry up, we should get nothing at all of the rations and then forcibly taking our share and a little extra as well. If you look as though you own the place, people may think you really do and several officers came to me with their worries, which I set right at once. This was to the annoyance of ‘Authority’ who saw its system crumbling beneath its eyes. My men, strangers from another Column, who were there to be given fatigues and cheated out of their food were not the only things neglected for, forgetting all that we owed to our faithful, plucky little mules, we would not endanger ourselves for five minutes to shoot all the mules in one fusillade, but tied them up to trees so that they could not follow us and would incidentally die of thirst.

Much must have been written about Japanese methods of war by people far better qualified to speak. I saw nothing, but heard a very great deal. The Jap is a great lover of noise, and adds to the noise of hundreds of un-aimed rounds and bursts, by using Chinese crackers, they sounded like very heavy mortar fire, but I comforted myself and as convincingly as I could, my men, that they were not mortars.

We sent in a couple of platoons with bayonets to attack people who then vanished, while others set up a demon-like screaming. They seemed to be trained to scream and no mass torturing by the Spanish Inquisition, nor the wildest demon souls in hell could have beaten their cries. Naturally diverting our attentions to the screamers, most of whom were either silenced or gave a good reason to continue; we did not notice the men with LMG’s (light machine guns) who walked up boldly under the shade of the trees. The time was 0200hrs. and there was a moon; they opened up on us from a very close range. They were charged at once, but melted away as easily as they had come up.

I had taken my mule back slightly and had grouped them all together; got my Order group round me and sent one British soldier off to report to the Major and act as runner. He did not get there and I doubt if he tried. I then went to sleep, not because I wanted to, but because I was sitting down and just slipped off. I was asleep for about an hour and woke up to hear the noise of elephants trumpeting and their bells ringing wildly as if they were stampeding. The firing was spasmodic but very intense in these spasms. Several wounded men were coming back and it was stated that several men had been shot. A Gurkha LMG was wanted, so I sent up a gun with its crew and an intelligent Naik to command the crew. Our second dispersal signal on the bugle was a long and very beautiful call; from the spasm of fire that it caused, I should not have enjoyed standing in, or indeed anywhere near the bugler’s boots. It was sounded just as the first pink of dawn was beginning to show. The dispersal means that we split up into small groups; vanish and re-appear again at some place at some pre-arranged time.

I told my Jemadar to lead all the Gurkhas down the track while I stood at the end of it and collected them as they filed past me in the jostling stream of people. It may have been due to my poor Kasqura (?), even poorer when I am excited, or it may have been just the excitement and panic of those who did not know what was happening and were guessing, but my Jemadar asked a British Other Rank what was going on; learned that we were all clearing off into the jungle because we could not go on and then cleared off himself.

Only twenty-seven men passed me, but I went off with them. Brigade HQ, without informing anyone, changed its RV with the result that most of the Column got lost and went back to India in small groups. I, however, by a brilliant stroke of bad map reading walked slap into the new RV just as Brigade were marching out. We marched all that night but covered very little ground as most of the night we moved little faster than a cinema queue, though when we were moving we were at the double. By morning we found that the carefully planned Brigade crossing of the Irrawaddi had been foiled and we were to break up into small groups and get back as best we could. It was here that people’s nerves got frayed; we were stuck in the ‘Shweli pocket’ with rivers on three sides and the Japs closing in from the south. I did not think of this however, for my platoon had marched for 50 hours without sleep, and had had just 10 hours sleep in the last 100.

I was in the ‘Shweli pocket’ for about a week after the foiled crossing of the Irrawaddi. We had one small ration drop, but though I dashed everywhere and saw 3 Column Command, their 2/IC’s, their ration officers and heaven knows how many others; it was only by telling my men that if they did not hurry up, we should get nothing at all of the rations and then forcibly taking our share and a little extra as well. If you look as though you own the place, people may think you really do and several officers came to me with their worries, which I set right at once. This was to the annoyance of ‘Authority’ who saw its system crumbling beneath its eyes. My men, strangers from another Column, who were there to be given fatigues and cheated out of their food were not the only things neglected for, forgetting all that we owed to our faithful, plucky little mules, we would not endanger ourselves for five minutes to shoot all the mules in one fusillade, but tied them up to trees so that they could not follow us and would incidentally die of thirst.

Bill's story concludes:

In more cases than not the mules were left saddled and sometimes still loaded. Man, when he is afraid for his own skin, is one of the vilest things alive. Were it not for the, perhaps merciful fact that we were all too tired to think, and were mortally afraid, there was little excuse for our cruelty. After an unsuccessful attempt to reach the Shweli, we managed to get a rope across a very narrow and consequently very fast bit of that vicious little river. Fifty men had got across and the dawn was breaking, so the fifty decided to push on while the main Column went back into the jungle. I was left on the bank with my own men, an RE boat and a rope tied to a tree on the far bank and moored by a squad of ‘anchormen’ on our side. I detailed three sections of men: the first for the boat, the second to wait, the third to anchor.

We needed one last man to bring back the boat and he was detailed. The first party got over and I went with them, dashing after the party of British Other Ranks to find out where they were going as they were to have a ration drop and unless we were in on it, things would become very difficult. The only information I got was bearing 60 degrees and a vague circle on my map enclosing twenty-five square miles of jungle. Then they pushed off.

Getting down to the river bank again, I waited for the boat to bring over the second party, before tackling the difficult, but not impossible job of getting the third party over without any anchor group. I waited sometime, but the boat did not come, then suddenly I realised what had happened, one boatman could not possibly hold the boat against the current. He had tried to go back and had been swept down stream. I was on one side of the river and most of my men on the other. I yelled ‘get back to the column’ and off they went. The men I had brought over had gone off with the BOR’s and I was alone. There was nothing for it but to go into the jungle a few yards and wait for the daylight in which to track the group.

Without my section, I was no longer in a fighting unit. Our one objective was to get out. In spite of that fearful night when I had left my men, I got back to them alright. I soon found out they were very necessary to me, while I was just a burden to them. At least there was now a wonderful sense of relief at being out of the Shweli pocket. It was not good to think of the men I had left at the Shweli, for the easiest mistake in the world becomes inexcusable when men’s lives are risked by it. The Japanese were closing in on them everyday.

Out of my platoon, I now had only one section. Company Commander to Section Commander in one week was a pretty rapid demotion, but in spite of all the nasty thoughts and memories, the next week was a grand one. We got a fine air dropping and walked off with as much as we could fit into our packs.

How I gradually became sick, I am not sure, but it became harder and harder to keep up. Perhaps it was a touch of malaria that I got, I don’t know, but instead of walking at the front of my men, I walked at the back and went step for step with a man who took about my stride length and was very steady, perhaps the concentration of stepping in his foot prints helped me on. We are all mercifully made, and the more that goes wrong, the more there seems to be thankful for. I began fainting, and was miserable when I woke up one day to find myself alone. I took to repeating the 23rd Psalm, over and over again to myself; I became very happy and remained so, for I was in a land of friendly villages. Once I stopped marching it was very hard to start again, this because we are made so that if we set our mind to do something, our health and strength will hold right on until the end if there is courage and the will to keep going. Once I stopped, thing after thing went wrong, my legs, head, feet, eyes and perhaps for all I know my brain, but that is another story!