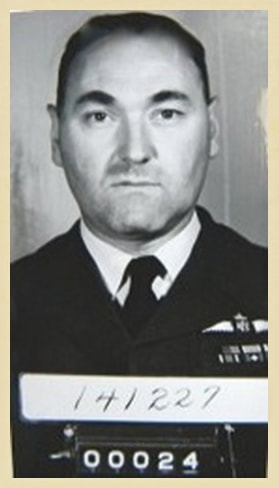

Lt. John H. Stewart-Jones

Cap badge of the Royal Scots.

Cap badge of the Royal Scots.

Lieutenant J.H. Stewart-Jones, formerly of the Royal Scots and known to his Army colleagues as Jock, joined up with the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at the very end of their training regime in December 1942. Throughout Chindit writings, in books and war diaries, this officer is often referred to as Stuart-Jones and can be found as such on some pages of this website.

After leaving the Indian railway town of Jhansi in January 1943, the Chindit Brigade moved by rail, paddle-steamer and then on foot, to their pre-operational base at Imphal. Lt. Stewart-Jones was placed into No. 4 Column and given charge of a Gurkha Rifle Platoon. Each officer was allocated a horse to ride during the expedition and on the march from Imphal to the Chindwin River in early February an unfortunate accident befell Stewart-Jones that may have prevented him from even taking part on Operation Longcloth.

From the War diary of No. 4 Column:

While on the subject of horses I may as well mention another story which is not quite so amusing. One night Lt. Stewart-Jones mounted his horse which was so well trained that instead of going forward it went backwards, only it went so fast that it toppled over. Incidentally, Stewart-Jones is an excellent horseman, but once in those saddles, jammed tight as you are, it is impossible to remove yourself without terrific preparation, so the horse came down on a tar-mac road with its full weight on Stewart-Jones.

I think that it was only the Everest Pack, with its iron frame that prevented a broken back. Stewart-Jones was very badly hurt and was removed to Imphal Hospital. An x-ray showed that there were no broken bones and Jones was fortunately able to join us just before we crossed the border. The horse was unhurt, but I do not think it was ever ridden again. By the way, the Everest Carrier frames were discarded at Imphal as impracticable and the ordinary Army webb equipment carried instead. So it would seem that Stewart-Jones had been doubly fortunate.

No. 4 Column was in the first instance commanded by Major Philip Alfred Ronayne Conron of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles and formed part of Northern Group on Operation Longcloth. However, not long into the expedition, Conron was relieved of his command and Brigade-Major George Bromhead took over. To read more about this incident and the wider story of No. 4 Column's time in Burma, please click on the following link: Major Bromhead and 4 Column

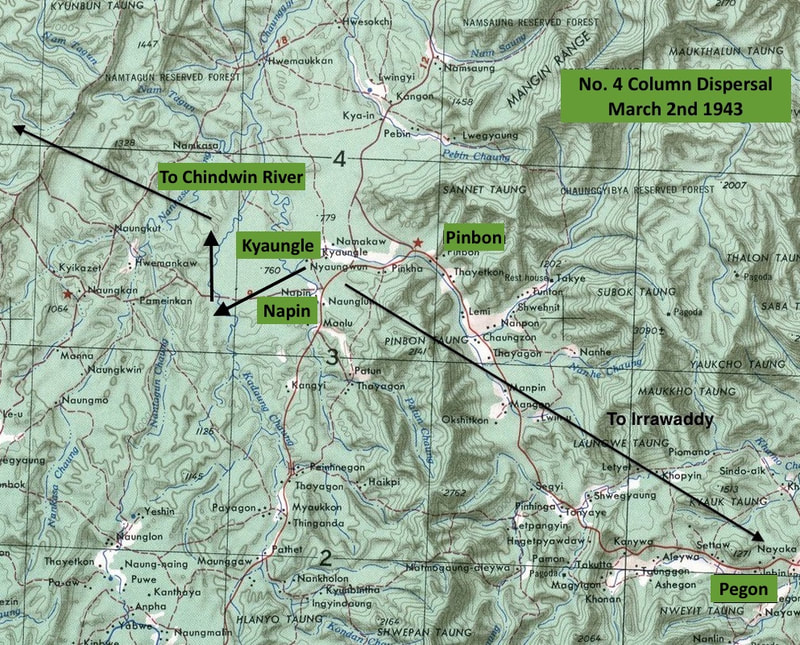

No. 4 Column were ambushed by the Japanese on the 2nd March 1943, close to the village of Pinbon. The column was caught out whilst crossing the small river on the outskirts of the village and although putting up a good fight, were broken down into separate groups by the enemy. The column radio was destroyed at the ambush, leaving Bromhead and his Head Quarters without the means to communicate with the rest of the Chindit Brigade or rear base back in India. He wisely decided to take his section of the column back to the Chindwin and the safety of Allied held territory.

Lt. Stewart-Jones and his Gurkha platoon were not with the commanders section of the column and in the company of Lt. Green and Captain Findlay of the Royal Engineers, led a party of 140 men eastwards towards the previously agreed rendezvous location. After several days away from the main body of the column, Captain Findlay, now concerned with how the party would acquire rations and supplies, sent out Stewart-Jones and a small scouting group to find the rest of the Brigade. Stewart-Jones eventually bumped No. 8 Column a few days later and reported his own column's predicament to Major Scott and eventually to Brigadier Wingate.

Scott ordered Stewart-Jones and his group to join No. 8 Column, placing them with the commando section. In the meantime, Captain Findlay and Lt. Green had decided to turn their group around and march directly back to the safety of India. Stewart-Jones and his Gurkhas remained with 8 Column until dispersal was called in late March 1943. He was then allocated to the party led by Captain Nigel Whitehead of the Burma Rifles, who had been given the onerous task of delivering the already sick and wounded Chindits into the hands of a friendly and trustworthy Kachin village.

To read more about Captain Whitehead and his contribution on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link: Captain Nigel Whitehead

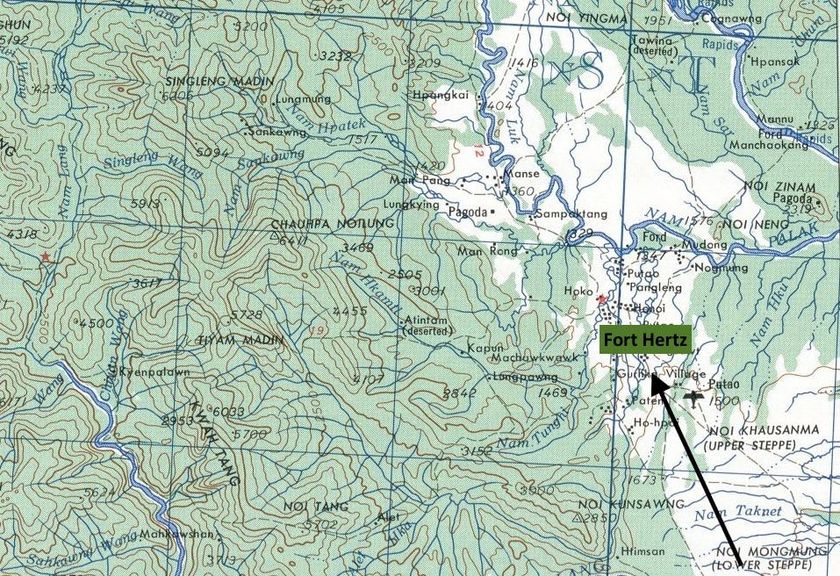

Having successfully dropped off the sick Chindits, Whitehead's group began the long march north towards Fort Hertz, an area in northeast Burma still known to be in Allied hands. Soon afterwards the party were ambushed by an enemy patrol and lost touch with both the Captain and his second in command, Flight Lieutenant Kenneth Wheatley of the RAF. Lt. Stewart-Jones, now leading his Gurkhas and the rest of the dispersal party, eventually got out of Burma, reaching the area around Fort Hertz several weeks later. After many weeks convalescing in hospital, he was able to re-join 3/2 Gurkha Rifles at their regimental depot in Dehra Dun.

After leaving the Indian railway town of Jhansi in January 1943, the Chindit Brigade moved by rail, paddle-steamer and then on foot, to their pre-operational base at Imphal. Lt. Stewart-Jones was placed into No. 4 Column and given charge of a Gurkha Rifle Platoon. Each officer was allocated a horse to ride during the expedition and on the march from Imphal to the Chindwin River in early February an unfortunate accident befell Stewart-Jones that may have prevented him from even taking part on Operation Longcloth.

From the War diary of No. 4 Column:

While on the subject of horses I may as well mention another story which is not quite so amusing. One night Lt. Stewart-Jones mounted his horse which was so well trained that instead of going forward it went backwards, only it went so fast that it toppled over. Incidentally, Stewart-Jones is an excellent horseman, but once in those saddles, jammed tight as you are, it is impossible to remove yourself without terrific preparation, so the horse came down on a tar-mac road with its full weight on Stewart-Jones.

I think that it was only the Everest Pack, with its iron frame that prevented a broken back. Stewart-Jones was very badly hurt and was removed to Imphal Hospital. An x-ray showed that there were no broken bones and Jones was fortunately able to join us just before we crossed the border. The horse was unhurt, but I do not think it was ever ridden again. By the way, the Everest Carrier frames were discarded at Imphal as impracticable and the ordinary Army webb equipment carried instead. So it would seem that Stewart-Jones had been doubly fortunate.

No. 4 Column was in the first instance commanded by Major Philip Alfred Ronayne Conron of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles and formed part of Northern Group on Operation Longcloth. However, not long into the expedition, Conron was relieved of his command and Brigade-Major George Bromhead took over. To read more about this incident and the wider story of No. 4 Column's time in Burma, please click on the following link: Major Bromhead and 4 Column

No. 4 Column were ambushed by the Japanese on the 2nd March 1943, close to the village of Pinbon. The column was caught out whilst crossing the small river on the outskirts of the village and although putting up a good fight, were broken down into separate groups by the enemy. The column radio was destroyed at the ambush, leaving Bromhead and his Head Quarters without the means to communicate with the rest of the Chindit Brigade or rear base back in India. He wisely decided to take his section of the column back to the Chindwin and the safety of Allied held territory.

Lt. Stewart-Jones and his Gurkha platoon were not with the commanders section of the column and in the company of Lt. Green and Captain Findlay of the Royal Engineers, led a party of 140 men eastwards towards the previously agreed rendezvous location. After several days away from the main body of the column, Captain Findlay, now concerned with how the party would acquire rations and supplies, sent out Stewart-Jones and a small scouting group to find the rest of the Brigade. Stewart-Jones eventually bumped No. 8 Column a few days later and reported his own column's predicament to Major Scott and eventually to Brigadier Wingate.

Scott ordered Stewart-Jones and his group to join No. 8 Column, placing them with the commando section. In the meantime, Captain Findlay and Lt. Green had decided to turn their group around and march directly back to the safety of India. Stewart-Jones and his Gurkhas remained with 8 Column until dispersal was called in late March 1943. He was then allocated to the party led by Captain Nigel Whitehead of the Burma Rifles, who had been given the onerous task of delivering the already sick and wounded Chindits into the hands of a friendly and trustworthy Kachin village.

To read more about Captain Whitehead and his contribution on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link: Captain Nigel Whitehead

Having successfully dropped off the sick Chindits, Whitehead's group began the long march north towards Fort Hertz, an area in northeast Burma still known to be in Allied hands. Soon afterwards the party were ambushed by an enemy patrol and lost touch with both the Captain and his second in command, Flight Lieutenant Kenneth Wheatley of the RAF. Lt. Stewart-Jones, now leading his Gurkhas and the rest of the dispersal party, eventually got out of Burma, reaching the area around Fort Hertz several weeks later. After many weeks convalescing in hospital, he was able to re-join 3/2 Gurkha Rifles at their regimental depot in Dehra Dun.

By September 1943, the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles had been re-formed and returned to War Establishment strength. In October the battalion, now under the command of Reggie Hutton and Philip Panton, moved to Conjeeveram, a town just outside of Madras. It was here that they began their jungle warfare training in preparation for the new campaign season due to begin in early 1944. By late February they had congregated in Calcutta, ready for their move down to Chittagong. On the 21st March 1944 the battalion became a component of the 74th Indian Infantry Brigade, part of the 25th Indian Division and tasked to eject the Japanese from the Arakan region of Burma.

The battalion fought well in the Arakan and were successful in helping defeat the Japanese in the area around Maungdaw, Razabil and Tamandu. During this time Captain Stewart-Jones led the battalion's B' Company which played a vital role in the fighting around Razabil. At some point during 1944, Stewart-Jones left the battalion and joined the RAF Regiment in order to continue his fight against the Japanese. One of his Gurkha contemporaries at that time, Lt. Dominic Neill recalled:

We were sorry to see Jock leave. He had been a good leader of men, especially of his small Gurkha platoon in 1943. He assisted my platoon greatly at Razabil, clearing away a large number of the enemy in difficult terrain. I always remember his wonderful singing voice in camp, belting out such songs as, Bonnie Strathyre.

There's meadows in Lanark and mountains in Skye.

And pastures in Hielands and Lowlands forbye:

But there's nae greater luck that the heart could desire

Than to herd the fine cattle in Bonnie Strathyre.

O, it's up in the morn and awa' to the hill,

When the lang simmer days are sae warm and sae still

Till the peak o' Ben Voirlich is girdled wi' fire,

And the evenin' fa's gently on bonnie Strathyre.

Then there's mirth in the sheiling and love in my breast,

When the sun is gane doun and the kye are at rest:

For there's mony a prince wad be proud to aspire

To my winsome wee Maggie, the pride o Strathyre.

Her lips are like rowans in ripe simmer seen.

And mild as the starlight the glint o' her e'en:

Far sweeter her breath than the scent o' the briar,

And her voice is sweet music in bonnie Strathyre.

Set Flora by Colin, and Maggie by me,

And we'll dance to the pipes swellin' loudly and free,

Till the moon in the heavens climbing higher and higher

Bids us sleep on fresh brackens in bonnie Strathyre.

Though some in the touns o' the Lawlands seek fame

And some will gang sodgerin' far from their hame;

Yet I'll aye herd my cattle, and bigg my ain byre.

And love my ain Maggie in bonnie Strathyre.

And pastures in Hielands and Lowlands forbye:

But there's nae greater luck that the heart could desire

Than to herd the fine cattle in Bonnie Strathyre.

O, it's up in the morn and awa' to the hill,

When the lang simmer days are sae warm and sae still

Till the peak o' Ben Voirlich is girdled wi' fire,

And the evenin' fa's gently on bonnie Strathyre.

Then there's mirth in the sheiling and love in my breast,

When the sun is gane doun and the kye are at rest:

For there's mony a prince wad be proud to aspire

To my winsome wee Maggie, the pride o Strathyre.

Her lips are like rowans in ripe simmer seen.

And mild as the starlight the glint o' her e'en:

Far sweeter her breath than the scent o' the briar,

And her voice is sweet music in bonnie Strathyre.

Set Flora by Colin, and Maggie by me,

And we'll dance to the pipes swellin' loudly and free,

Till the moon in the heavens climbing higher and higher

Bids us sleep on fresh brackens in bonnie Strathyre.

Though some in the touns o' the Lawlands seek fame

And some will gang sodgerin' far from their hame;

Yet I'll aye herd my cattle, and bigg my ain byre.

And love my ain Maggie in bonnie Strathyre.

In early 1944, John Stewart-Jones wrote a short debrief of his experiences on Operation Longcloth, mostly as a response to the unwarranted (in his view) criticism of the Gurkhas performance in 1943 and in defence in particular of his own Gurkha Rifle Platoon:

31/01/1944

184992 Lt. J.H. Stewart Jones attached 3/2 Gurkha Rifles.

To the Commandant 2nd KEO Gurkha Rifles Regimental Centre.

Sir,

I have read with interest the account in the recent issue of the Regimental News; of the part played by the 3rd Battalion during the operations of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in Burma. Erroneous impressions are liable to be formed by people unconnected with the battalion who may have or read the official report on operations of the above mentioned Brigade.

I therefore feel it incumbent upon me to ask that this account of the conduct of four Rifleman be placed on the Regimental record.

These four were members of No. 4 Column, commanded until March 1st 1943 by Major Conron, 2nd KEO Gurkha Rifles. On March 1st, Major Bromhead, (Royal Berks) took over command and the column ordered to provide the diversion, by road blocks and other means necessary to allow the other elements of the Brigade (cols. 3, 5, 7 and 8) to proceed to their objectives.

The Burma Rifles section commanded by Lt. FW. Burn was ordered to recce the village of Pinbon and surrounding areas. This party was ambushed and Lt. Burn wounded and the reconnaissance abandoned. Myself and the four Riflemen volunteered to locate the patrol and wounded officer and bring them back into column. During this time we encountered the enemy, which we defeated at no cost to ourselves. All advantage had been with the enemy, but the intelligence and obedience of these Gurkhas to all commands, wrestled this away and we forced a successful conclusion. The discipline of these men under fire was of the highest order and in keeping with Gurkha traditions.

The following day No. 4 Column proceeded south under Major Bromhead and halted in column snake, half a mile of Pinbon. The last two groups of our men and animals were still in the process of crossing a small river which bounded Pinbon, when the first Japanese grenades and mortars fell upon the column. The enemy attempted to cut the line in four places, attacking our flanks.

No orders for any definite plan of action came from HQ, and with visibility down to just 30 yards, I ordered Subedar Tikajit Pun to withdraw our section of the column north over the river. After the action had lasted around twenty minutes and withdrawing through various engagements with the enemy, we collected 150 men and 30 animals. I ordered Lt. Green (2nd KEO Gurkha Rifles) to lead the column one mile to the north while we held the river with a platoon.

That same evening we caught Lt. Green up and headed south through primary jungle. Two days later we were down to 137 all ranks. I handed command of the column to the most senior officer present, Captain Findlay of the Royal Engineers and we decided to bivouac in the jungle and send out a patrol to contact Brigade HQ (Wingate). Our wireless was useless, food non-existent apart from our bullocks, which of course the Gurkhas could not very well eat and the men were in all opinion too weak to continue.

My Riflemen accompanied me alongside two British Other Ranks and two Burmese scouts in search of Brigade HQ. We did not know the location of Brigade, but on the second day we followed the direction of supply planes who were dropping to some of our groups a few miles away. After six days hard marching and with only two hours halt/sleep on each of these days, we bumped No. 8 Column and made our report. Major Scott gave us our first decent meal for over ten days.

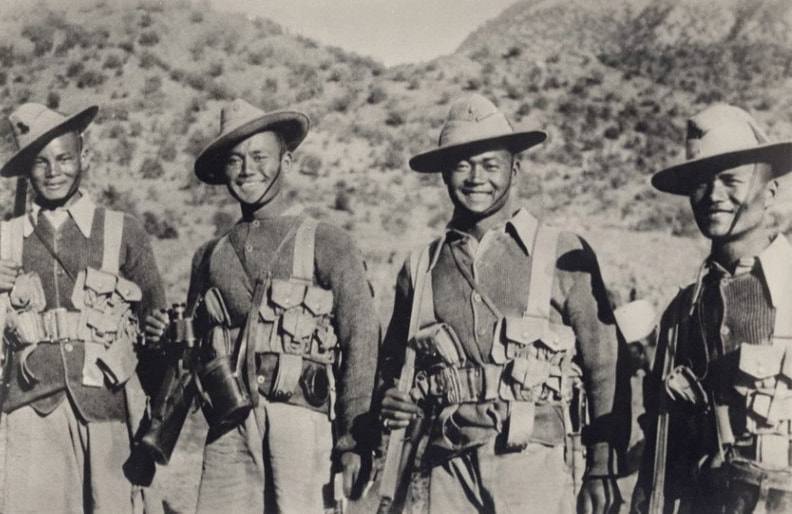

My four Gurkhas had in addition to carrying their own personal weapons, also carried a LMG (light machine gun) and ammunition through some of the toughest country in Burma, in pursuit of a force which disdained the use of known tracks and pathways and had hidden their progress from anyone following by crossing and re-crossing many waterways.

On March 10th we were ordered to go back one day’s march along the track and lead in the remainder of 4 Column. We waited in position overlooking the track, but saw no sign of any men. We returned to re-join Brigade HQ; about three weeks later I was informed that Major Bromhead and 4 Column had arrived back in India. After confirmation of this news, myself and my four Gurkhas were permanently attached No. 8 Column. Eventually, I took command of No. 16 Platoon, who were mostly British Other Ranks and some other men previously muleteers. My four Gurkhas stayed with me and in this way we felt that No. 4 Column were still represented on the expedition.

My Gurkhas became very well respected within the column and performed to a high standard, much better in my opinion than any of the British soldiers. Major Scott then gave me permission to promote on the four to Naik and I chose Rfm. Amar Singh Gurung. His untiring cheerful attitude in the face of the difficulties which beset the column and his intelligent appreciation of every situation made him one of the most respected soldiers in the whole column. From my own personal point of view, no words can express my gratitude in being permitted to serve with such men. Wherever I went, slept or ate, the four Gurkhas were never more than a few yards away.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of Lt. Stewart-Jones' story, including a map of the area around Pinbon. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Lt. Stewart-Jones memoir continues:

About the end of March we took a large supply drop near the village of Baw. The enemy interfered with the drop and the first combat group led by a King’s officer was repulsed, with a platoon from No. 7 Column then ordered to attack in support. Colonel Cooke then ordered me to take my men and move through the village to contact No. 7 Column. We moved slowly through thick and thorny jungle and then entered the village which we found to be deserted. All of a sudden machine gun fire opened up on us from under a house and all hell broke loose. All my British sections abandoned the action and made for the river.

Thankfully, the Japanese fire was inaccurate and we suffered no casualties. My Gurkhas and I collected together the ammunition the King’s had discarded and I ordered them back into action. Soon after, when the leading section commander was killed, the King’s ran again. I ordered the men to go in again, this time via the river, this was in the rear of enemy machine gun position. With my Gurkhas I attacked with no. 68 grenades. Things got a little sticky when the Japanese opened up on us with rifle fire from three sides. Amar Singh then got a Bren gun into action and we silenced the enemy guns. The troops present in the village at that time were: Major Scott and his group, Pte. Kemple of the King’s and my four Gurkhas. We withdrew from our positions without further loss and Major Scott subjected the village to heavy mortar fire from the Support Platoon.

My platoon were now between the river and the rest of the column. I held each position from the river allowing the rest of the men to withdraw. With assistance from Lt. Rowlands and Captain Coughlan we succeeded in getting everyone out and our mortars brought fire down on the enemy. My Gurkhas were congratulated by Major Scott for the vital role they played during the action at Baw. Unfortunately, in the Official Report for the expedition, there is no mention of my Gurkhas being involved and yet at least eight Japanese lay dead at the scene in testimony of their presence.

After four days forced march we arrived at the east bank of the Irrawaddy, where it was decided we would cross that night. Unexpected enemy opposition on the far banks was considered too strong for us to continue and general dispersal was called. No. 8 Column decided to turn east and cross the Shweli River and then attempt another crossing of the Irrawaddy to the north near Bhamo. On the 1st April, 80 men got across the Shweli using RAF dinghies, but then the boats were lost due to an error with the ropes. A second attempt was made this time using constructed bamboo rafts, but these proved too flimsy and were swept away in the strong current.

In light of the many non-swimmers in our group, no more attempts were made that day. More rubber dinghies were dropped to us during the night and everyone was across by 0800 hours the next morning.

Just prior to our move over the river, a Gurkha recognition whistle was heard by our group and on investigation, we discovered Major Conron with two British Officers and sixty mixed Gurkha and British other ranks, all previously from Brigade Head Quarters. Conron had no equipment for crossing the river, but did not accept the invitation to remain with us in bivouac and cross the following day. Later during the evening we heard firing from further down the river but saw no more of Major Conron, who told me his intention was to make for the Northern Shan States east of the Shweli.

Two days later we had another supply drop and obtained ten days rations. It was decided to move further east to avoid the areas where other columns had stirred up Japanese patrols. After another six days marching we broke up into dispersal units of around sixty men in each and headed under our own means for India. I was included in the party led by Captain Whitehead of the Burma Rifles and took with me my four Gurkhas, plus the six best Kingsmen from No. 16 Platoon. We were given the task of taking several wounded men on stretchers to the nearest friendly Kachin or Shan village.

Two days march from the previous column bivouac, we managed to place the wounded men with the Headman of a Kachin village. Whether they were looked after or not I do not know. The next day we were ambushed by a mixed force of Burmese and Japanese. We had pre-arranged a rendezvous point in case of attack, about half a mile to the north. I made the RV alongside two Burma Riflemen and one Burmese officer, we waited there all night.

Leaving the rendezvous point we then made three days march to the next agreed meeting place, on the Sinlumkaba Tract in the Kachin Hills. On entering a village in search of food, we were reunited with the remainder of our original group, sadly less Captain Whitehead and Flight Lieutenant Wheatley, who had been lost and a medical orderly who had been handed over to the Japanese by the Shans.

About the end of March we took a large supply drop near the village of Baw. The enemy interfered with the drop and the first combat group led by a King’s officer was repulsed, with a platoon from No. 7 Column then ordered to attack in support. Colonel Cooke then ordered me to take my men and move through the village to contact No. 7 Column. We moved slowly through thick and thorny jungle and then entered the village which we found to be deserted. All of a sudden machine gun fire opened up on us from under a house and all hell broke loose. All my British sections abandoned the action and made for the river.

Thankfully, the Japanese fire was inaccurate and we suffered no casualties. My Gurkhas and I collected together the ammunition the King’s had discarded and I ordered them back into action. Soon after, when the leading section commander was killed, the King’s ran again. I ordered the men to go in again, this time via the river, this was in the rear of enemy machine gun position. With my Gurkhas I attacked with no. 68 grenades. Things got a little sticky when the Japanese opened up on us with rifle fire from three sides. Amar Singh then got a Bren gun into action and we silenced the enemy guns. The troops present in the village at that time were: Major Scott and his group, Pte. Kemple of the King’s and my four Gurkhas. We withdrew from our positions without further loss and Major Scott subjected the village to heavy mortar fire from the Support Platoon.

My platoon were now between the river and the rest of the column. I held each position from the river allowing the rest of the men to withdraw. With assistance from Lt. Rowlands and Captain Coughlan we succeeded in getting everyone out and our mortars brought fire down on the enemy. My Gurkhas were congratulated by Major Scott for the vital role they played during the action at Baw. Unfortunately, in the Official Report for the expedition, there is no mention of my Gurkhas being involved and yet at least eight Japanese lay dead at the scene in testimony of their presence.

After four days forced march we arrived at the east bank of the Irrawaddy, where it was decided we would cross that night. Unexpected enemy opposition on the far banks was considered too strong for us to continue and general dispersal was called. No. 8 Column decided to turn east and cross the Shweli River and then attempt another crossing of the Irrawaddy to the north near Bhamo. On the 1st April, 80 men got across the Shweli using RAF dinghies, but then the boats were lost due to an error with the ropes. A second attempt was made this time using constructed bamboo rafts, but these proved too flimsy and were swept away in the strong current.

In light of the many non-swimmers in our group, no more attempts were made that day. More rubber dinghies were dropped to us during the night and everyone was across by 0800 hours the next morning.

Just prior to our move over the river, a Gurkha recognition whistle was heard by our group and on investigation, we discovered Major Conron with two British Officers and sixty mixed Gurkha and British other ranks, all previously from Brigade Head Quarters. Conron had no equipment for crossing the river, but did not accept the invitation to remain with us in bivouac and cross the following day. Later during the evening we heard firing from further down the river but saw no more of Major Conron, who told me his intention was to make for the Northern Shan States east of the Shweli.

Two days later we had another supply drop and obtained ten days rations. It was decided to move further east to avoid the areas where other columns had stirred up Japanese patrols. After another six days marching we broke up into dispersal units of around sixty men in each and headed under our own means for India. I was included in the party led by Captain Whitehead of the Burma Rifles and took with me my four Gurkhas, plus the six best Kingsmen from No. 16 Platoon. We were given the task of taking several wounded men on stretchers to the nearest friendly Kachin or Shan village.

Two days march from the previous column bivouac, we managed to place the wounded men with the Headman of a Kachin village. Whether they were looked after or not I do not know. The next day we were ambushed by a mixed force of Burmese and Japanese. We had pre-arranged a rendezvous point in case of attack, about half a mile to the north. I made the RV alongside two Burma Riflemen and one Burmese officer, we waited there all night.

Leaving the rendezvous point we then made three days march to the next agreed meeting place, on the Sinlumkaba Tract in the Kachin Hills. On entering a village in search of food, we were reunited with the remainder of our original group, sadly less Captain Whitehead and Flight Lieutenant Wheatley, who had been lost and a medical orderly who had been handed over to the Japanese by the Shans.

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Lt. Stewart-Jones continues:

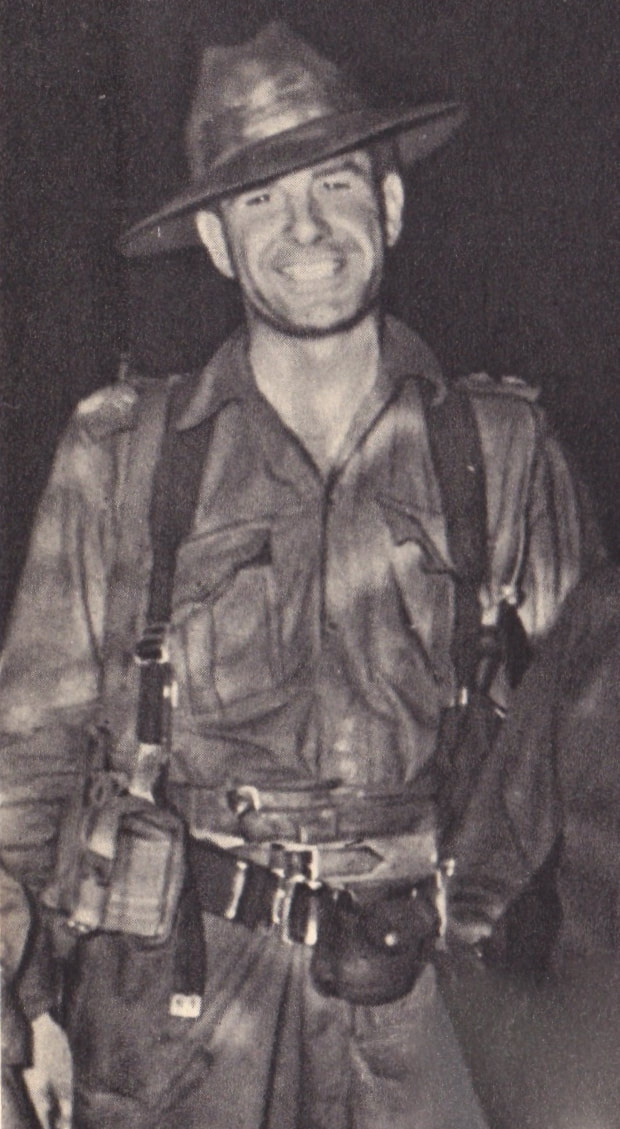

I took charge of the party and averaging around 12 miles per day we pushed on to the north. We made slow progress due to the nature of the country and jungle and the men grew weak with hunger, having eaten little else than rice, bamboo leaves and roots for several weeks. As well as this, most men were suffering in a greater or lesser degree with malaria, dysentery and sceptic sores. Our clothing was in rags and a few men were without any footwear. Our journey took us as high as 5000 feet and into very cold conditions, followed almost immediately by plunging down once more into the steaming hot jungle valley.

Having no maps of the area in which we were travelling and only one compass, I had to rely on the knowledge and skill of my Kachin Jemadar, Ah Di of the Burma Rifles. His fluency in the various dialects made him invaluable in obtaining information from villagers. In the hills opposite the east of Bhamo I lost one Kachin and two Karen riflemen, who decided to take their chances and head home. It was also at this time that we picked up Lieutenant Smyly of No. 5 Column, who was in a very weak state and barely able to walk. He was left in a friendly village, with Jemadar Ah Di instructing the villagers that they would be held responsible for his safety and well-being.

Everyone was now in a very weak state, and at this time the Gurkhas were on average sticking at it better than the British soldiers and even the Burma Rifles. Through the efforts of Ah Di, we hired a Kachin guide who had once been with the Burma Frontier Force. He led us north and entered all villages first to check for Japanese patrols and to acquire rice to supplement our meagre rations. The Kachins in this area were very poor indeed and fearful of the Japs, but on the whole extremely friendly towards us.

Continuing north we met a Kachin from one of the earlier dispersal parties returning to his home to the south. He told us that Sumprabum had fallen to the Japanese and that Fort Hertz was currently surrounded by the enemy and was likely to soon be taken. This seemed to be the death knell of my plans to reach Fort Hertz and I turned northeast for the Chinese border. On the track I found an unconscious British Other Rank who had been left by a preceding group. We gave him some quinine and took him to the nearest village.

Some days later we reached another village, where the Headman gave us rice and potatoes. He refused any payment and told us it was his duty to help any soldiers who were trying to defeat the Japanese. He also gave me two one-inch maps of the area through which we would have to travel. These became invaluable to me, as they showed in detail the country which lay ahead of us. We had 350 miles still to travel and the monsoon rains were not too far from beginning.

We marched on and were about to attempt the crossing of a river, when a local Kachin stopped us saying that the Japanese were a little way ahead and waiting to ambush any British stragglers at the ferry point. I realised we were in no condition to fight our way around these enemy troops and so gratefully accepted the Kachin’s offer of a guide to lead us over the Chinese Border. Over the next few days I lost six men from my party who dropped out through exhaustion. I decided to spend the following day at rest by a small river. We had not washed for many weeks and were infested with the biggest lice I have ever seen.

Jemadar Ah Di went out on a recce that day and came into contact with a Chinese Army patrol. They fed us rice and much needed salt and housed us in bashas. Here I had a rough hair cut, beard trim and wash with soap and hot water. The Chinese officer refused payment but I gave him my wristwatch as a thank you. He then informed me that Fort Hertz was still in Allied hands and was only four days march from where we stood.

We reached Tingumn and were met by Captain Torrie of the North Kachin Levies. He had been told that we were coming and had food waiting as well as dressings for our wounds and sores. His commander, Colonel Gamble had radioed through a message telling us that two other parties from our Brigade had passed through his position a week beforehand. We were all given new uniforms and PT shoes to replace our tattered Army boots.

That night I collapsed and went down with typhoid, having felt ill for the previous eight days but not telling anyone. The rest of my group left over the next few days, being escorted by the Levies to Fort Hertz. My four Gurkhas refused to leave my side even though I was barely conscious or indeed rational at the time. In the end they went on to Fort Hertz and then were flown back to India. I did not get out until the 8th July and then spent some weeks at Chabna Hospital in Assam and Shillong British Military Hospital, eventually reaching Dehra Dun at the end of October.

My account of the return march to India is brief and uninformative, especially when regarding the conduct of these four individuals. I wish it to be known that their conduct was exemplary and did not deteriorate in any way, not even as disease, weakness and hunger sapped their energy and efficiency. These four men were a constant source of encouragement and support and were vital in no small way to the safety of my group on the final part of the march to Fort Hertz.

On my arrival at Dehra Dun I searched for the men and was greatly annoyed to find that Naik Amar Singh Gurung had been put back to the rank of Rifleman, without even being paid for his period as Naik for his time in Burma. I sent in a recommendation for these soldiers to be recognised in some way for their sterling services in Burma. Nothing has come of this since and I should like, if no medal can be awarded, that a mention of these men be placed into the Regimental Record at the very least.

Signed: Lt. J.H. Stewart Jones

I took charge of the party and averaging around 12 miles per day we pushed on to the north. We made slow progress due to the nature of the country and jungle and the men grew weak with hunger, having eaten little else than rice, bamboo leaves and roots for several weeks. As well as this, most men were suffering in a greater or lesser degree with malaria, dysentery and sceptic sores. Our clothing was in rags and a few men were without any footwear. Our journey took us as high as 5000 feet and into very cold conditions, followed almost immediately by plunging down once more into the steaming hot jungle valley.

Having no maps of the area in which we were travelling and only one compass, I had to rely on the knowledge and skill of my Kachin Jemadar, Ah Di of the Burma Rifles. His fluency in the various dialects made him invaluable in obtaining information from villagers. In the hills opposite the east of Bhamo I lost one Kachin and two Karen riflemen, who decided to take their chances and head home. It was also at this time that we picked up Lieutenant Smyly of No. 5 Column, who was in a very weak state and barely able to walk. He was left in a friendly village, with Jemadar Ah Di instructing the villagers that they would be held responsible for his safety and well-being.

Everyone was now in a very weak state, and at this time the Gurkhas were on average sticking at it better than the British soldiers and even the Burma Rifles. Through the efforts of Ah Di, we hired a Kachin guide who had once been with the Burma Frontier Force. He led us north and entered all villages first to check for Japanese patrols and to acquire rice to supplement our meagre rations. The Kachins in this area were very poor indeed and fearful of the Japs, but on the whole extremely friendly towards us.

Continuing north we met a Kachin from one of the earlier dispersal parties returning to his home to the south. He told us that Sumprabum had fallen to the Japanese and that Fort Hertz was currently surrounded by the enemy and was likely to soon be taken. This seemed to be the death knell of my plans to reach Fort Hertz and I turned northeast for the Chinese border. On the track I found an unconscious British Other Rank who had been left by a preceding group. We gave him some quinine and took him to the nearest village.

Some days later we reached another village, where the Headman gave us rice and potatoes. He refused any payment and told us it was his duty to help any soldiers who were trying to defeat the Japanese. He also gave me two one-inch maps of the area through which we would have to travel. These became invaluable to me, as they showed in detail the country which lay ahead of us. We had 350 miles still to travel and the monsoon rains were not too far from beginning.

We marched on and were about to attempt the crossing of a river, when a local Kachin stopped us saying that the Japanese were a little way ahead and waiting to ambush any British stragglers at the ferry point. I realised we were in no condition to fight our way around these enemy troops and so gratefully accepted the Kachin’s offer of a guide to lead us over the Chinese Border. Over the next few days I lost six men from my party who dropped out through exhaustion. I decided to spend the following day at rest by a small river. We had not washed for many weeks and were infested with the biggest lice I have ever seen.

Jemadar Ah Di went out on a recce that day and came into contact with a Chinese Army patrol. They fed us rice and much needed salt and housed us in bashas. Here I had a rough hair cut, beard trim and wash with soap and hot water. The Chinese officer refused payment but I gave him my wristwatch as a thank you. He then informed me that Fort Hertz was still in Allied hands and was only four days march from where we stood.

We reached Tingumn and were met by Captain Torrie of the North Kachin Levies. He had been told that we were coming and had food waiting as well as dressings for our wounds and sores. His commander, Colonel Gamble had radioed through a message telling us that two other parties from our Brigade had passed through his position a week beforehand. We were all given new uniforms and PT shoes to replace our tattered Army boots.

That night I collapsed and went down with typhoid, having felt ill for the previous eight days but not telling anyone. The rest of my group left over the next few days, being escorted by the Levies to Fort Hertz. My four Gurkhas refused to leave my side even though I was barely conscious or indeed rational at the time. In the end they went on to Fort Hertz and then were flown back to India. I did not get out until the 8th July and then spent some weeks at Chabna Hospital in Assam and Shillong British Military Hospital, eventually reaching Dehra Dun at the end of October.

My account of the return march to India is brief and uninformative, especially when regarding the conduct of these four individuals. I wish it to be known that their conduct was exemplary and did not deteriorate in any way, not even as disease, weakness and hunger sapped their energy and efficiency. These four men were a constant source of encouragement and support and were vital in no small way to the safety of my group on the final part of the march to Fort Hertz.

On my arrival at Dehra Dun I searched for the men and was greatly annoyed to find that Naik Amar Singh Gurung had been put back to the rank of Rifleman, without even being paid for his period as Naik for his time in Burma. I sent in a recommendation for these soldiers to be recognised in some way for their sterling services in Burma. Nothing has come of this since and I should like, if no medal can be awarded, that a mention of these men be placed into the Regimental Record at the very least.

Signed: Lt. J.H. Stewart Jones

Copyright © Steve Fogden, January 2019.