Captain Denis Clive Herring

Cap badge of the Royal Armoured Corps.

Cap badge of the Royal Armoured Corps.

Denis Clive Herring was born on the 6th December 1916 and was the son of Ernest Leonard and Irene Margaret Herring from Parkstone in Dorset. Denis was educated at Queens College, Taunton and then attended the RAF College at Cranwell in Lincolnshire.

He was commissioned into the Regular Army Reserve of Officers (Royal Armoured Corps) on the 24th October 1936 and was appointed 2nd Lieutenant with the Royal Tank Corps on the 13th October 1937. Later, after he had travelled to Burma to begin his career with the Forestry Department of the Bombay-Burmah Trading Company, he was appointed full Lieutenant (ABRO 32) on the 10th November 1939.

Lt. Herring served with the 1st Battalion, the Burma Rifles during the infamous retreat from Burma in 1942. On his return to India, and with the acting rank of Captain, he became part of the Composite Burma Rifles Battalion in June 1942. It was not long after this, that he transferred to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade alongside many other men from the 2nd Battalion the Burma Rifles and began his involvement with the Chindits.

Denis Herring, unsurprisingly known to all as Fish, was allocated to No. 7 Column during initial training with the Chindits, which took place at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India. However, Brigadier Wingate was aware of his expertise in both the Burmese and Kachin languages and his previous experience in working in northern Burma as a Forestry Manager. With this in mind, Wingate chose to give Herring a special task on Operation Longcloth and sent him ahead of the main body of the Brigade, to make contact with the tribes of the Kachin Hill Tracts and Shan States in order to raise up local assistance against the Japanese.

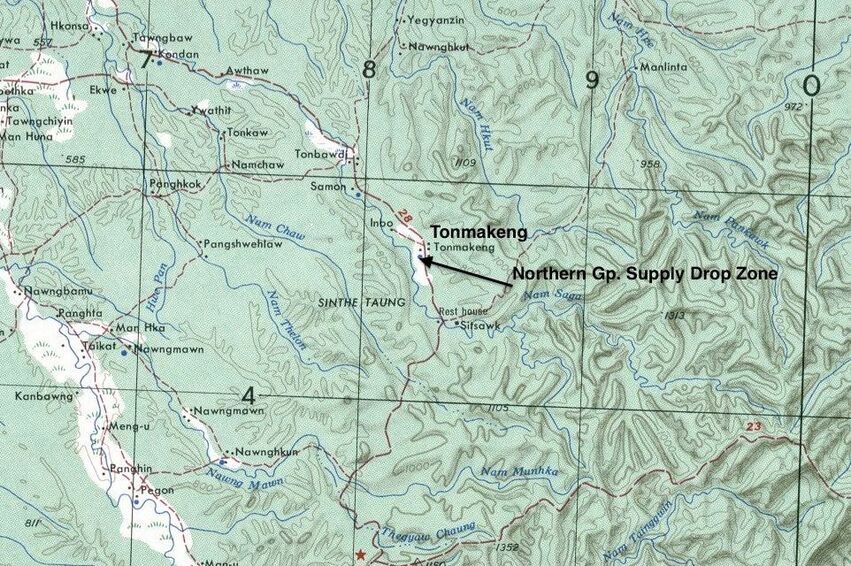

Even before the main expedition set out for the Chindwin, in December 1942 Captain Herring had led a small reconnaissance party across the river to inspect the lay of the land on the east banks, check on enemy patrol strength and ultimately decide on a location for the first full supply drop for the Brigade, planned for mid-February 1943. He returned with vital intelligence, meeting the Brigade at their new holding camp at Imphal and recommended the village of Tonmakeng to Wingate, having already made friends with the local Headman and secured his support. To read more about this mission, please click on the following link: Pre-Operational Reconnaissance

He was commissioned into the Regular Army Reserve of Officers (Royal Armoured Corps) on the 24th October 1936 and was appointed 2nd Lieutenant with the Royal Tank Corps on the 13th October 1937. Later, after he had travelled to Burma to begin his career with the Forestry Department of the Bombay-Burmah Trading Company, he was appointed full Lieutenant (ABRO 32) on the 10th November 1939.

Lt. Herring served with the 1st Battalion, the Burma Rifles during the infamous retreat from Burma in 1942. On his return to India, and with the acting rank of Captain, he became part of the Composite Burma Rifles Battalion in June 1942. It was not long after this, that he transferred to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade alongside many other men from the 2nd Battalion the Burma Rifles and began his involvement with the Chindits.

Denis Herring, unsurprisingly known to all as Fish, was allocated to No. 7 Column during initial training with the Chindits, which took place at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India. However, Brigadier Wingate was aware of his expertise in both the Burmese and Kachin languages and his previous experience in working in northern Burma as a Forestry Manager. With this in mind, Wingate chose to give Herring a special task on Operation Longcloth and sent him ahead of the main body of the Brigade, to make contact with the tribes of the Kachin Hill Tracts and Shan States in order to raise up local assistance against the Japanese.

Even before the main expedition set out for the Chindwin, in December 1942 Captain Herring had led a small reconnaissance party across the river to inspect the lay of the land on the east banks, check on enemy patrol strength and ultimately decide on a location for the first full supply drop for the Brigade, planned for mid-February 1943. He returned with vital intelligence, meeting the Brigade at their new holding camp at Imphal and recommended the village of Tonmakeng to Wingate, having already made friends with the local Headman and secured his support. To read more about this mission, please click on the following link: Pre-Operational Reconnaissance

As arranged previously, after crossing the Chindwin River for a second time in mid-February 1943, Captain Herring parted company with No. 7 Column around March 1st and headed northeast for the Kachin Hills. After returning from Operation Longcloth later in the year, Herring described his activities in the form of an official report:

Report by Capt. D.C. Herring on his activities in the Kachin Hills during the first Wingate expedition in 1943

I entered Burma on 13th February with 77 Indian Infantry Brigade but having a Guerilla platoon of Kachins under my commamd whom I considered unsuitable for Guerilla operations amongst Shans and Burmans, I asked for permission to proceed ahead of the Brigade into the Kachin Hills to raise the Kachins in arms against the Japanese and to prepare the way for the arrival of part of 77 Brigade into the Hills.

Prior to my departure from my Column on 28th February, I arranged to meet a Brigade representative by the road bridge over the Nam Hpaung River a south bank tributary of the Shweli River on 25th March. My request for a powerful wireless set was refused as it was considered unnecessary.

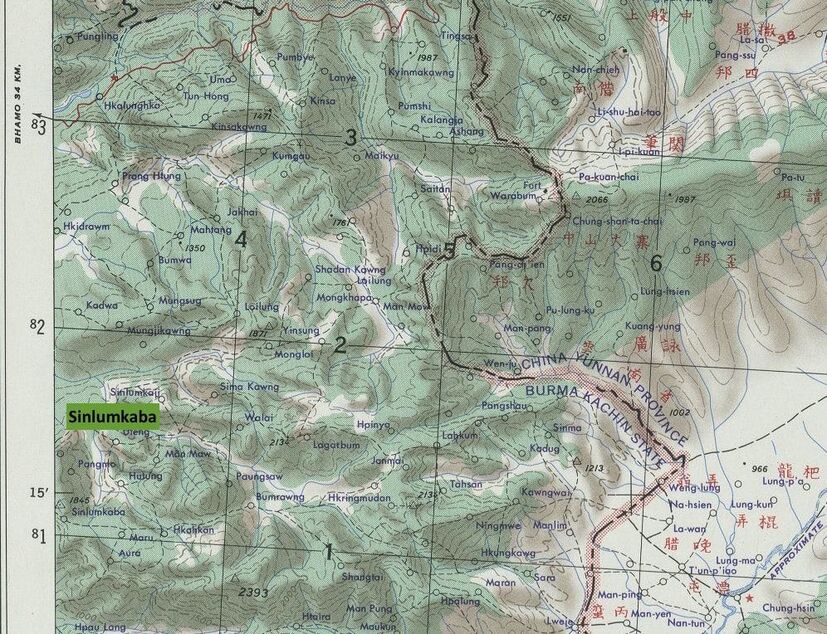

I arrived in the Sinlumkaba Hill Tracts on 15th March and stayed until 18th March at Munghkapa. Here I met Jemadar Munga Tu and other Kachin elders to whom I explained my mission. My story was that I had come up into the hills to raise the Kachins in rebellion against the Japanese. Our tactics were to be guerrilla tactics consisting of the destruction of the several small Japanese garrisons and their lines of communication in the Bhamo area, the ambushing of parties of enemy using the main hill tracks and the disruption of the Japanese lines of communication between Namhkan, Bhamo and Myitkhina.

I explained to them how we could be supplied with arms and ammunition from the air as we, the British and Americans, now had air superiority over Burma. The scheme was well received and the news that a small British Force had arrived in the hills spread very quickly. Even during the four days I spent at Munghkapa prior to my departure on 19th March to meet the Brigade representative at the agreed rendezvous, it became apparent that any Kachin rising could be on a much larger scale than I had originally thought possible.

The areas from where I was hoping to raise men were, the Sinlumkaba Hill Tracts, the Kodaung Hill Tracts and the Lashio and the Kutkai Districts. I believe that I make no exaggeration when I say that as many as 2,500 men could be called up from these districts. The areas are rich in retired and serving Burma Rifle and B.F.F. personnel, the vast majority of whom saw active service during the operations in Burma 1941/42.

In addition to these, almost every village can produce a minimum of half-a-dozen able bodied men keen to fight. Even the women asked how they could help; my 2nd-in-Command, Lt. Lazum Tang, had told them about the various women's organisations in Britain. Between the 16th and the 18th of March approximately 100 men from the villages in the vicinity of Munghkapa reported for duty, although I had not as yet sent out any 'Cailing-up" notice.

On the 19th March I left half of my Platoon under Lt. Lazum Tang in the Gaurikrung area and departed on my journey to the Kodaung Hill Tracts to meet the Brigade representative. The news of my journey had leaked out. When approaching Sinlumkaba I arrested the Sinlum Police Station Dak runner who told me that the Burman Inspector of Police, one U Nyi, had the previous evening sent a letter to the Nippon Commander of Bhamo, asking him to send troops to Sinlumkaba and also to the Bhamo-Namhkan motor road to stop my passage across it.

400 Japanese arrived at Sinlum two days later and the M.T. road was closely watched. I only managed to cross it because the Kachins made it their business to see me safely over. Throughout the six weeks I spent in the Hills the enemy were continually trying to run my party to earth. On contacting Brigade I was hoping to arrange for immediate dropping of arms and ammunition and for the calling up of the Kachins from the Bhamo area. Prior to may departure I had sent Subedar Hting Nang with a small party to the Lashio District to feel the pulse of that area. He was to spread the same story and to warn the Kachins to be prepared to report for duty about the middle of April.

The journey to the R.V. took me six days. All along the route I was enthusiastically received by the Kachins to whom I explained my mission. The Headmen of the villages I entered professed their loyalty to the British and spoke of the difficulties the Kachins were experiencing under the Japanese administration. I make further mention of this below. I reached the R.V. on the 25th March and remained there until 29th March, but in spite of patrolling along the track towards Mong Mit I made no contact with 77 Brigade.

NB. Herring was due to meet up with the columns of Southern Group, led by Major Dunlop, commander of No. 1 Column. However, due to their own difficulties earlier in the expedition, this rendezvous was missed by several days, although the group remained in the general area around the Shweli River for just over a week.

Herring continues:

I was now in a difficult position, being able to raise the Kachins in the Sinlum and Kodaung Hill tracts when required, but not having the weapons with which to arm them. It was to meet such an emergency as this, that I particularly wanted a powerful W/T set. I rejoined my platoon on 3rd April and decided to attempt to reach the Chinese on the east side of the Salween River, with a view to getting W/T communication with India to enable me to report the position in the Kachin area and the intelligence I had collected in the hills. I had to explain to the Kachin people that our plan had miscarried, but that I was attempting to get them arms etc. by round-about means. I entered Yunnan Province on 5th April and very soon ran into trouble; I had no maps but was hoping that the Atki Kachins and the Chinese would guide me along the hill tracks to the Salween.

The assistance I received in Yunnan was conspicuous by the reluctance with which it was given. The Japanese were reported to be on all the main tracks and this fact together with the lack of maps, local assistance and our inability to speak Yunnanese, caused me to turn back to British territory on 9th April. I re-entered the Bhamo District on the 13th. The Japanese learnt of our presence in Yunnan almost as soon as we entered the Province and we had two very narrow escapes from strong patrols which were following us; a ten minute escape the first time and a thirty minute escape the second.

On arriving back in the Ganrikrung area I decided to make northwards to Sumpra Bum, where I hoped to join up with the Kachin Levies. However, I delayed my second departure as I was receiving reports of British and Indian troops having been seen or heard of in various areas. I made efforts to locate and contact these parties as it seemed obvious that they were members of the Brigade and I hoped that they would have wireless sets.

Subedar Hting Nang returned to Munghkapa an the 16th and gave me a full report of his activities in the Lashio District. Here, as in the Bhamo District, the Kachins were fervently loyal and ready to fight when called upon and given the means to do so. In the face of this good news it was difficult indeed to have to tell him of my failure to gain any contact with Brigade. The Subedar has now returned to Namhpakka, until his services are further required here. He has been told that a full report of the possibilities of a Kachin rising will be made to a higher authority. In the event of any action being decided upon soon, I told him that an effort would be made to drop propaganda pamphlets containing a code over the Hsenwi, Kutkai and Namhpakka areas warning him to prepare the local Kachins for action. The code is explained in an annexure to this report.

NB. The code mentioned by Captain Herring was in fact the phrase: An Elephant Never Forgets.

I entered Burma on 13th February with 77 Indian Infantry Brigade but having a Guerilla platoon of Kachins under my commamd whom I considered unsuitable for Guerilla operations amongst Shans and Burmans, I asked for permission to proceed ahead of the Brigade into the Kachin Hills to raise the Kachins in arms against the Japanese and to prepare the way for the arrival of part of 77 Brigade into the Hills.

Prior to my departure from my Column on 28th February, I arranged to meet a Brigade representative by the road bridge over the Nam Hpaung River a south bank tributary of the Shweli River on 25th March. My request for a powerful wireless set was refused as it was considered unnecessary.

I arrived in the Sinlumkaba Hill Tracts on 15th March and stayed until 18th March at Munghkapa. Here I met Jemadar Munga Tu and other Kachin elders to whom I explained my mission. My story was that I had come up into the hills to raise the Kachins in rebellion against the Japanese. Our tactics were to be guerrilla tactics consisting of the destruction of the several small Japanese garrisons and their lines of communication in the Bhamo area, the ambushing of parties of enemy using the main hill tracks and the disruption of the Japanese lines of communication between Namhkan, Bhamo and Myitkhina.

I explained to them how we could be supplied with arms and ammunition from the air as we, the British and Americans, now had air superiority over Burma. The scheme was well received and the news that a small British Force had arrived in the hills spread very quickly. Even during the four days I spent at Munghkapa prior to my departure on 19th March to meet the Brigade representative at the agreed rendezvous, it became apparent that any Kachin rising could be on a much larger scale than I had originally thought possible.

The areas from where I was hoping to raise men were, the Sinlumkaba Hill Tracts, the Kodaung Hill Tracts and the Lashio and the Kutkai Districts. I believe that I make no exaggeration when I say that as many as 2,500 men could be called up from these districts. The areas are rich in retired and serving Burma Rifle and B.F.F. personnel, the vast majority of whom saw active service during the operations in Burma 1941/42.

In addition to these, almost every village can produce a minimum of half-a-dozen able bodied men keen to fight. Even the women asked how they could help; my 2nd-in-Command, Lt. Lazum Tang, had told them about the various women's organisations in Britain. Between the 16th and the 18th of March approximately 100 men from the villages in the vicinity of Munghkapa reported for duty, although I had not as yet sent out any 'Cailing-up" notice.

On the 19th March I left half of my Platoon under Lt. Lazum Tang in the Gaurikrung area and departed on my journey to the Kodaung Hill Tracts to meet the Brigade representative. The news of my journey had leaked out. When approaching Sinlumkaba I arrested the Sinlum Police Station Dak runner who told me that the Burman Inspector of Police, one U Nyi, had the previous evening sent a letter to the Nippon Commander of Bhamo, asking him to send troops to Sinlumkaba and also to the Bhamo-Namhkan motor road to stop my passage across it.

400 Japanese arrived at Sinlum two days later and the M.T. road was closely watched. I only managed to cross it because the Kachins made it their business to see me safely over. Throughout the six weeks I spent in the Hills the enemy were continually trying to run my party to earth. On contacting Brigade I was hoping to arrange for immediate dropping of arms and ammunition and for the calling up of the Kachins from the Bhamo area. Prior to may departure I had sent Subedar Hting Nang with a small party to the Lashio District to feel the pulse of that area. He was to spread the same story and to warn the Kachins to be prepared to report for duty about the middle of April.

The journey to the R.V. took me six days. All along the route I was enthusiastically received by the Kachins to whom I explained my mission. The Headmen of the villages I entered professed their loyalty to the British and spoke of the difficulties the Kachins were experiencing under the Japanese administration. I make further mention of this below. I reached the R.V. on the 25th March and remained there until 29th March, but in spite of patrolling along the track towards Mong Mit I made no contact with 77 Brigade.

NB. Herring was due to meet up with the columns of Southern Group, led by Major Dunlop, commander of No. 1 Column. However, due to their own difficulties earlier in the expedition, this rendezvous was missed by several days, although the group remained in the general area around the Shweli River for just over a week.

Herring continues:

I was now in a difficult position, being able to raise the Kachins in the Sinlum and Kodaung Hill tracts when required, but not having the weapons with which to arm them. It was to meet such an emergency as this, that I particularly wanted a powerful W/T set. I rejoined my platoon on 3rd April and decided to attempt to reach the Chinese on the east side of the Salween River, with a view to getting W/T communication with India to enable me to report the position in the Kachin area and the intelligence I had collected in the hills. I had to explain to the Kachin people that our plan had miscarried, but that I was attempting to get them arms etc. by round-about means. I entered Yunnan Province on 5th April and very soon ran into trouble; I had no maps but was hoping that the Atki Kachins and the Chinese would guide me along the hill tracks to the Salween.

The assistance I received in Yunnan was conspicuous by the reluctance with which it was given. The Japanese were reported to be on all the main tracks and this fact together with the lack of maps, local assistance and our inability to speak Yunnanese, caused me to turn back to British territory on 9th April. I re-entered the Bhamo District on the 13th. The Japanese learnt of our presence in Yunnan almost as soon as we entered the Province and we had two very narrow escapes from strong patrols which were following us; a ten minute escape the first time and a thirty minute escape the second.

On arriving back in the Ganrikrung area I decided to make northwards to Sumpra Bum, where I hoped to join up with the Kachin Levies. However, I delayed my second departure as I was receiving reports of British and Indian troops having been seen or heard of in various areas. I made efforts to locate and contact these parties as it seemed obvious that they were members of the Brigade and I hoped that they would have wireless sets.

Subedar Hting Nang returned to Munghkapa an the 16th and gave me a full report of his activities in the Lashio District. Here, as in the Bhamo District, the Kachins were fervently loyal and ready to fight when called upon and given the means to do so. In the face of this good news it was difficult indeed to have to tell him of my failure to gain any contact with Brigade. The Subedar has now returned to Namhpakka, until his services are further required here. He has been told that a full report of the possibilities of a Kachin rising will be made to a higher authority. In the event of any action being decided upon soon, I told him that an effort would be made to drop propaganda pamphlets containing a code over the Hsenwi, Kutkai and Namhpakka areas warning him to prepare the local Kachins for action. The code is explained in an annexure to this report.

NB. The code mentioned by Captain Herring was in fact the phrase: An Elephant Never Forgets.

Captain Herring's report concludes:

On the 17th April, I sent all my men from the Bhamo and Lashio Districts and the civilians who had joined my small force back to their homes as the journey to Sumprabum was reported to be a difficult, one made even more so by the paucity of rice and vegetables further north. Prior to their departure to their homes the situation was fully explained to them and they were warned that they would be required to report for duty if called upon by any British Officer who might subsequently arrive in the hills.

On the 18th April, I made contact with H.Q. 2nd Burma Rifles and learnt of the fate of the Brigade, that being their break-up into small parties in an endeavour to reach India. Had I had a powerful W/T set I could have reported on the favourable situation in the Kachin Hills where many would have found asylum.

On the 19th April the remainder of my platoon, that being, the men from the Myitkhina District, and H.Q. 2nd Burma Rifles left Gaurikrung for Sumprabum and Putao (Fort Hertz). The news received en route was not heartening; we heard that Putao and Sumprabum were now in enemy hands. However, as these reports originated from the Japs themselves, we hoped that it was only propaganda and so decided to push on. The news that only Sumprabum and not Putao were in Jap hands was not finally confirmed until we contacted the Chinese at Kaji Tu in the Triangle. We eventually reached the Kachin Levy Head Quarters at La Awng Ga on 11th May.

The only result then of my activities in the Kachin Hills during March and April, is that I am able to confirm that the Kachins throughout the Bhamo and Lashio Districts still remain as loyal to the British. To use their own words, 'they pray for the return of their British parents and are willing to fight to further this end.'

Their present policy of non-co-operation with the Japanese is not helping to ease the difficulties under which they are living. Salt and cloth are desperately needed in every village. Could not the loyalty of these splendid people be rewarded by dropping cloth and salt and a message of appreciation and encouragement from the Government over parts of the Kachin Hills? It would mean a lot to the Kachins to see real evidence that they have not been forgotten.

I attach three letters received from Kachins. They are marked Nos. 2, 3 and 4. The letter from Zau Seng (Letter 3) asks for arms and ammunition to be given to the villages as soon as possible. It was his idea that small parties should annoy the Japs where and whenever possible. I have pointed out to him that such tactics will only result in the communal punishment of villages by the enemy and will not seriously inconvenience him.

The fact that a rising, to be a success, must be properly organised and the men properly officered, does not appear to be appreciated by the Kachins. I have explained to them at length the value of an organised rising in the hills at a time when the main Japanese attention is directed elsewhere and I have also tried to make them understand that a series of small un-coordinated actions at a time when the Jap is able to send a considerable number of troops against the Kachins, will not be of great value and will spoil any chance of eventually surprising the enemy with a well timed large scale rising.

Letter No. 4, is from the Police Station Officer at Sinlumkaba and speaks of the will of the area police to join any British rising en bloc, as soon as all preparations are completed and the order to open fire is given. Letter No. 2 needs no explanation.

Letter No. 1, is a list of arms, ammunition, paddy, etc. purchased by one, Sara Maru Gam of Yitsand Village, with his own money. It is being hidden in the jungle until such time as it is required to further a British rising.

Some mention should be made of the loathing the Kachins feel for the Shans and the Burmans. They are acting as spies and rationing parties for the Japs and have brought trouble to the Hills. The Kachins will kill them if they get an opportunity. Here I should make mention of a report that came from the Lashio District. It was in reference to the damage done and the misery caused by the Chinese during their withdrawal through the hills last year; the Kachins will fight them too, if they appear again in these particular hill tracts.

Finally, before closing this report, a reference is required to the large sums of money still owing to the Kachin soldiers in this region. Nearly every soldier who has made his way back to the hills after the first Burma campaign is owed a minimum of Rs.100 and although it does not appear to be affecting his loyalty or satisfaction, they all mention the fact and express an opinion that every effort should be made to settle the debt as soon as possible. My commanding Officer, late Colonel L.G. Wheeler, told me that I should tell all old soldiers that I met in the Hills, that they need have no fear, but that their arrears of pay would be settled to date, provided they all reported for duty when called upon. They have been told that in spite of their absence from the Regiment they are all still considered as soldiers of the King.

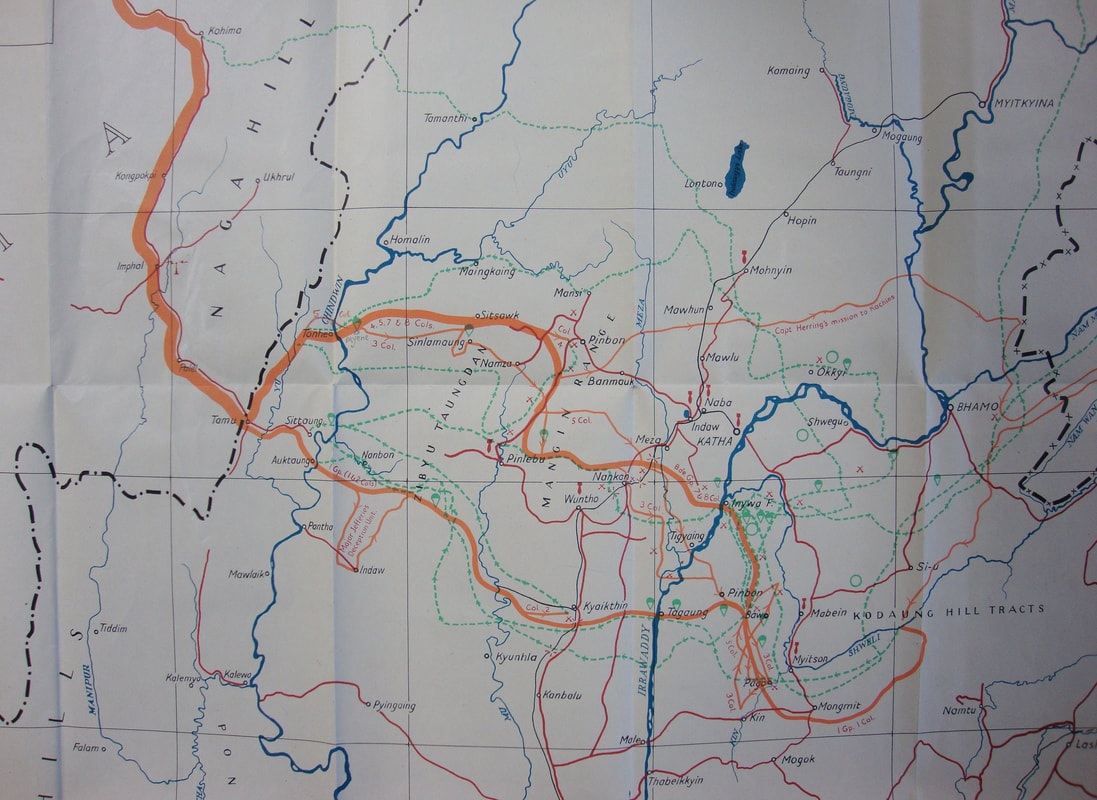

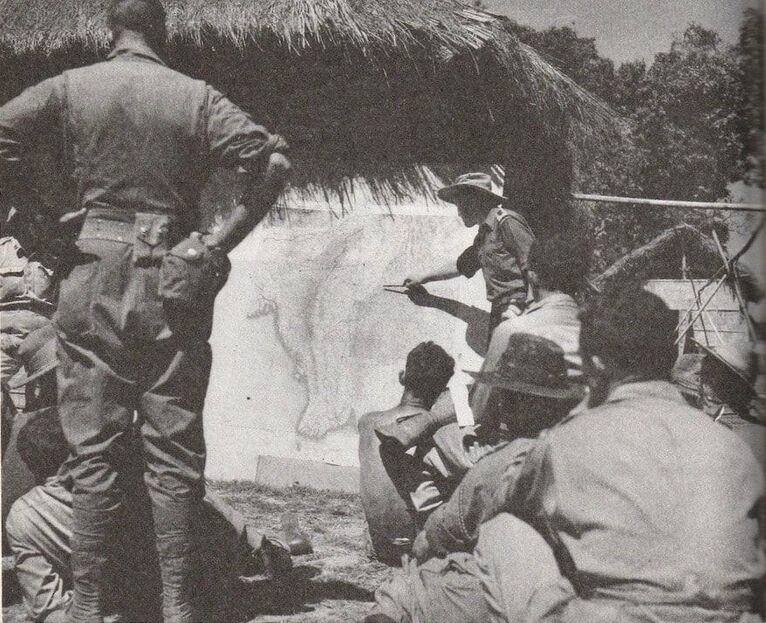

Seen below is a map of the various column movements during Operation Longcloth. The thin orange line which turns off eastward around the village of Banmauk, denotes Captain Herring and his mission into the Kachin Hill Tracts of northern Burma during March and April 1943. Please click on the map to bring it forward on the page.

The Military Cross medal.

The Military Cross medal.

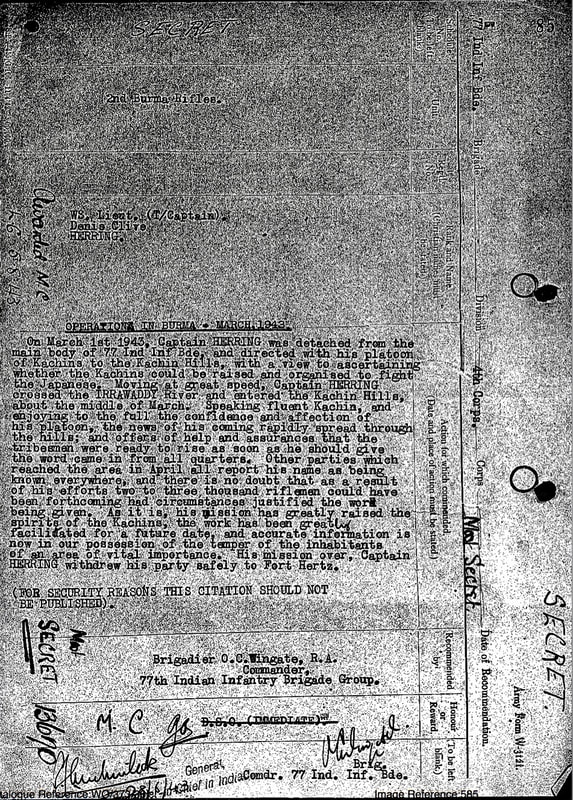

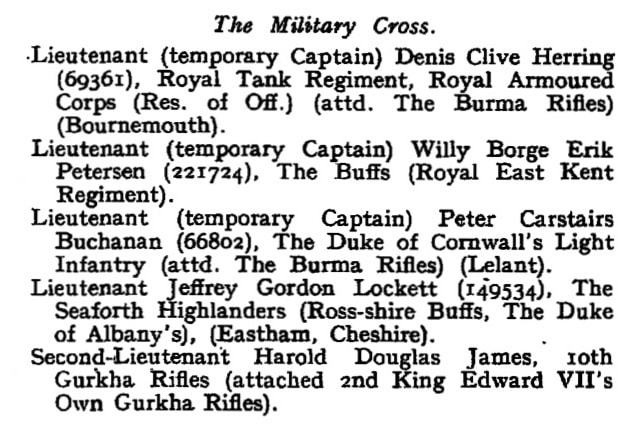

For his efforts on Operation Longcloth, Denis Herring was awarded the Military Cross:

Brigade: 77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Corps: 4th Corps

Unit: Royal Tank Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps, attached 2nd Burma Rifles

Regimental No. 69361 (ABRO 32)

Rank and Name: Temporary Captain Denis Clive Herring

Action for which recommended:

OPERATIONS IN BURMA - MARCH 1943

On March 1st 1943, Captain Herring was detached from the main body of 77 Indian Infantry Brigade and directed with his platoon of Kachins to the Kachin Hills, with a view to ascertaining whether the local Kachins could be raised and organised to fight the Japanese. Moving at great speed, Captain Herring crossed the Irrawaddy River and entered the Kachin Hills about the middle of March. Speaking fluent Kachin, and enjoying to the full the confidence and affection of his platoon, the news of his coming rapidly spread through the hills and offers of help and assurances that the tribesmen were ready to rise as soon as he should give the word came in from all quarters.

Other parties which reached the area in April all report his name as being known everywhere, and there is no doubt that as a result of his efforts two to three thousand riflemen could have been forthcoming had circumstances justified the word being given. As it is, his mission has greatly raised the spirits of the Kachins, the work has been greatly facilitated for a future date, and accurate information is in our possession of the temper of the inhabitants of an area of vital importance. His mission over, Captain Herring withdrew his party safely to Fort Hertz.

Recommended By: Brigadier O.C. Wingate, DSO, Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade Group.

Honour or Reward: Military Cross (London Gazette 5th August 1943).

Signed By: Brigadier O.C. Wingate, Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and General Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief, India.

Brigade: 77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Corps: 4th Corps

Unit: Royal Tank Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps, attached 2nd Burma Rifles

Regimental No. 69361 (ABRO 32)

Rank and Name: Temporary Captain Denis Clive Herring

Action for which recommended:

OPERATIONS IN BURMA - MARCH 1943

On March 1st 1943, Captain Herring was detached from the main body of 77 Indian Infantry Brigade and directed with his platoon of Kachins to the Kachin Hills, with a view to ascertaining whether the local Kachins could be raised and organised to fight the Japanese. Moving at great speed, Captain Herring crossed the Irrawaddy River and entered the Kachin Hills about the middle of March. Speaking fluent Kachin, and enjoying to the full the confidence and affection of his platoon, the news of his coming rapidly spread through the hills and offers of help and assurances that the tribesmen were ready to rise as soon as he should give the word came in from all quarters.

Other parties which reached the area in April all report his name as being known everywhere, and there is no doubt that as a result of his efforts two to three thousand riflemen could have been forthcoming had circumstances justified the word being given. As it is, his mission has greatly raised the spirits of the Kachins, the work has been greatly facilitated for a future date, and accurate information is in our possession of the temper of the inhabitants of an area of vital importance. His mission over, Captain Herring withdrew his party safely to Fort Hertz.

Recommended By: Brigadier O.C. Wingate, DSO, Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade Group.

Honour or Reward: Military Cross (London Gazette 5th August 1943).

Signed By: Brigadier O.C. Wingate, Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and General Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief, India.

As a footnote to Captain Herring's mission during the first Wingate expedition; it was generally felt that his liaison with the Kachin tribes had achieved very little in regards the development and training of active Levies or any positive military action taken by the Kachins against the Japanese. The Kachins themselves were more than disappointed in the British failure to come up with the goods, in relation to supplying weapons and money to the militias and former soldiers who had previously served under the British in 1942. For this in the end, they blamed Captain Herring and he left the area in April 1943, somewhat under a cloud. Wingate was also far from impressed, most especially in regards the failure of Captain Herring in meeting up with Southern Group in late March 1943, something that Herring had little control over, after Southern Group's slow progress in reaching the area around Mong Mit.

In reality, some good had come of the mission. Excellent relationships had been built up between Herring and many Kachin Headmen and leaders in March/April 1943. In his debrief document, Captain Herring lists some of the Kachin leaders who had been of most value to him during the weeks of Operation Longcloth, these included:

Namna Gawng of Namna Ga village, who acted on several occasions as a guide for the mission. Herring adds that the village was severely punished by the Japanese for assisting the British later that year.

Munga Tu, a former soldier with the Burma Signals in 1942. He was an elder of Munghkpa village in the Bhamo District of Burma and had been a great help to the Chindit mission. He was subsequently arrested by the Japanese and remained under open arrest for well over a year.

Mayam Du, Headman of Bumgahtawng village near Sinlumkaba. This man was so trustworthy that he was given the responsibility of looking after some of the Chindit equipment, including a wireless set, that had to be left behind when they left the area in April 1943.

Zau Htang of Lahtaw Hpakum village, who fed and housed Herring's party and provided useful intelligence concerning Japanese positions and numbers in the area.

Zau Seng, the Duwa of Shangtai village, a keen supporter of the proposed raising of Kachin Levies.

Latsi Gam, the Duwa of Kauri Laiza in the Nalong District of Burma. This man provided both food and shelter to the Chindits and acted as their guide for three days on their journey further north.

Kahtaw La of Chamja village located west of Sima. This man was a former soldier with the Burma Army in 1942 and also acted as a guide, leading a party of Gurkhas who had been left behind through to Allied held territory.

La Gawk La, Duwa of Pasang Gawng village. Offered great assistance to Herring's party in getting them over the Umai Hka River.

In reality, some good had come of the mission. Excellent relationships had been built up between Herring and many Kachin Headmen and leaders in March/April 1943. In his debrief document, Captain Herring lists some of the Kachin leaders who had been of most value to him during the weeks of Operation Longcloth, these included:

Namna Gawng of Namna Ga village, who acted on several occasions as a guide for the mission. Herring adds that the village was severely punished by the Japanese for assisting the British later that year.

Munga Tu, a former soldier with the Burma Signals in 1942. He was an elder of Munghkpa village in the Bhamo District of Burma and had been a great help to the Chindit mission. He was subsequently arrested by the Japanese and remained under open arrest for well over a year.

Mayam Du, Headman of Bumgahtawng village near Sinlumkaba. This man was so trustworthy that he was given the responsibility of looking after some of the Chindit equipment, including a wireless set, that had to be left behind when they left the area in April 1943.

Zau Htang of Lahtaw Hpakum village, who fed and housed Herring's party and provided useful intelligence concerning Japanese positions and numbers in the area.

Zau Seng, the Duwa of Shangtai village, a keen supporter of the proposed raising of Kachin Levies.

Latsi Gam, the Duwa of Kauri Laiza in the Nalong District of Burma. This man provided both food and shelter to the Chindits and acted as their guide for three days on their journey further north.

Kahtaw La of Chamja village located west of Sima. This man was a former soldier with the Burma Army in 1942 and also acted as a guide, leading a party of Gurkhas who had been left behind through to Allied held territory.

La Gawk La, Duwa of Pasang Gawng village. Offered great assistance to Herring's party in getting them over the Umai Hka River.

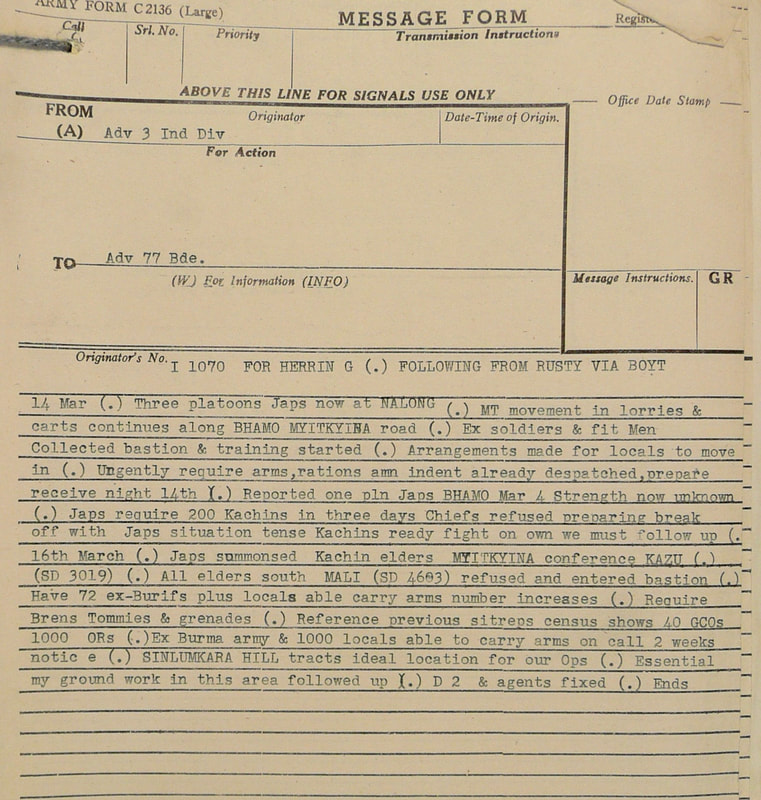

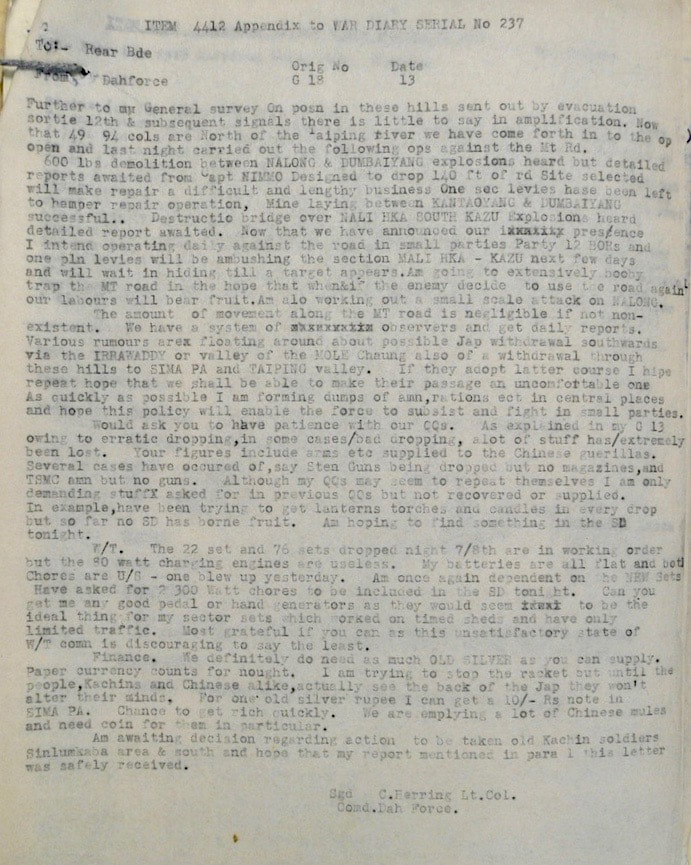

In 1944, Denis Herring was asked once again to lead a mission into the Kachin Hills as part of the second Chindit expedition, codenamed, Operation Thursday. His directive was almost exactly the same as the year before, but this time he was to actively encourage the Kachins to strike out at the enemy in guerrilla type actions. With the rank of Acting Lt-Colonel, Herring took his men, codenamed Dah Force into the hills around Sinlumkaba. Here he set up his Head Quarters, known as a stronghold and quickly built up an intelligence framework, which joined together all the local tribes people in a co-ordinated attacks on the Japanese. This included ambushing and harassing the enemy on the Myitkhina-Bhamo Road and taking control of the Irrawaddy River in that area. He also set up a recruitment centre where the Kachins were trained in the art of guerrilla warfare.

Although acting alone in this endeavour, Herring came under the overall command of 77 Brigade, with his immediate superior nominated as Colonel J.R. Morris of the 4/9 Gurkha Rifles (Morris Force), who was also in the area, but in a more overt capacity. Herring also made contact with SOE and OSS (American) representatives in the Kachin Hills, liaising with these groups to ensure proper co-ordination in regards planning and carrying out operations against the Japanese. There was no time limit set for the mission, which began from the Broadway stronghold on the 14th March, although the plan was to create the infrastructure necessary for a successful guerrilla campaign by the monsoon period.

Herring did not wish to use British troops in his unit, as he believed, probably rightly, that their dietary requirements and lack of acclimatisation to the humid tropical jungle rendered them unsuitable for the campaign. Dah Force consisted of 74 men: Lt-Colonel Herring, Captain Lazum Tang and ten other Kachins of the Burma Rifles, Major John Kennedy, Captain William Nimmo of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, a communication detachment of 19 men from the Royal Corps of Signals led by Captain Treckman, nine Chinese of the Hong Kong Volunteers who were to liaise with the Nationalist Chinese, a platoon of 27 South Staffords under Captain Railton; a demolitions expert Sergeant Cockling of the Grenadier Guards; US liaison officer Sherman P. Joost (a member of OSS) and Private Williams of the RAMC to whom it fell to care for all the sick and wounded. As predicted the British regulars disliked the conditions intensely and took some time to get acclimatised, though in the end they performed admirably.

By mid-April 1944, Dah Force in conjunction with the other special forces groups in the area had caused great damage to the Japanese war machine and morale in Northern Burma. Eventually, the physical condition of the men in Herring's group began to be affected by the strain of operations, poor diet and disease. Dah Force exited the Kachin Hills with the assistance of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services), whom Captain Lazum Tang decided to join in order to continue taking the fight to the enemy. Sadly, his involvement with Dah Force and OSS would take a terrible toll on his own family, with his wife being murdered by the Japanese in reprisal for his actions against them and one of his sons perishing through disease.

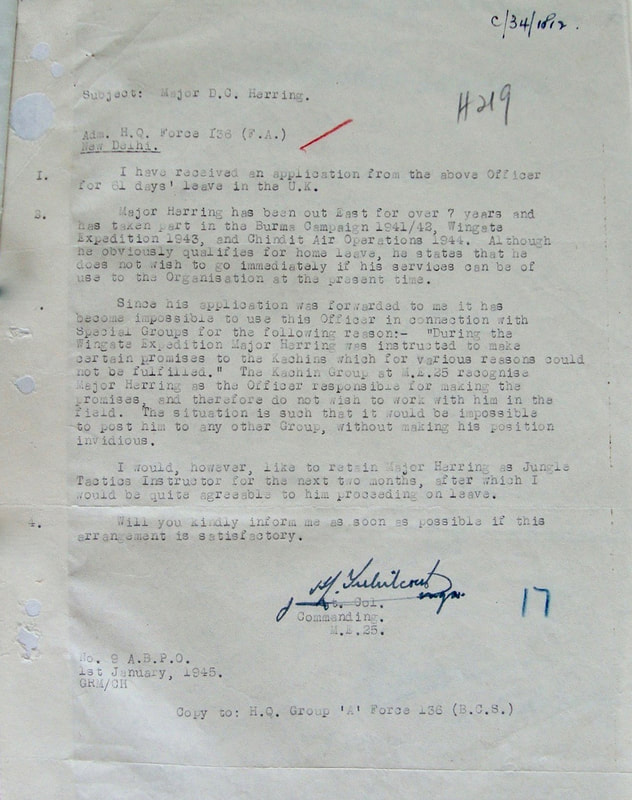

In October 1944, Herring, now holding the rank of Major, transferred to SOE (Force 136) and headed the Kachin Special Group in operations, including an expedition codenamed, HEAVY/WOLF in February 1945 for which he was Mentioned in Despatches. This expedition, formerly codenamed Hainton, took place in Kentung State and included raids on both Thai and Japanese forces, creating disturbances along the Salween River and northern Siam lines of communication. In late August 1945, Major Herring was awarded two months special leave, during which time he travelled back to the United Kingdom and married his fiancee Diana Sharp at Poole in Dorset.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including Denis Herring's original Military Cross citation. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Apart from the above narrative, you can find more information about the wartime experiences of Denis Herring here:

For details of his papers held at the Imperial War Museum, please click on the following link:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1030004887

For details about his SOE file, held at the National Archives in London (Kew), please click on the following link:

discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C12046065

To read more about Denis Herring and his time with the Chindits and SOE, please follow the link to Richard Duckett's excellent website on the same subject: soeinburma.wordpress.com/2019/05/06/soe-the-chindits-stormy-relations/

Amongst other positions, on his return to England after the war, Denis worked as a Chartered Surveyor with the firm Rumsey & Rumsey. Sadly, Denis Clive Herring passed away on the 7th January 2006, following a short illness at his home in Poole (Dorset), he was 89 years old. At his funeral flowers were discouraged in favour of donations to the Chindits Old Comrades Association.

For details of his papers held at the Imperial War Museum, please click on the following link:

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1030004887

For details about his SOE file, held at the National Archives in London (Kew), please click on the following link:

discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C12046065

To read more about Denis Herring and his time with the Chindits and SOE, please follow the link to Richard Duckett's excellent website on the same subject: soeinburma.wordpress.com/2019/05/06/soe-the-chindits-stormy-relations/

Amongst other positions, on his return to England after the war, Denis worked as a Chartered Surveyor with the firm Rumsey & Rumsey. Sadly, Denis Clive Herring passed away on the 7th January 2006, following a short illness at his home in Poole (Dorset), he was 89 years old. At his funeral flowers were discouraged in favour of donations to the Chindits Old Comrades Association.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, June 2019.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, June 2019.