The Longcloth Roll Call

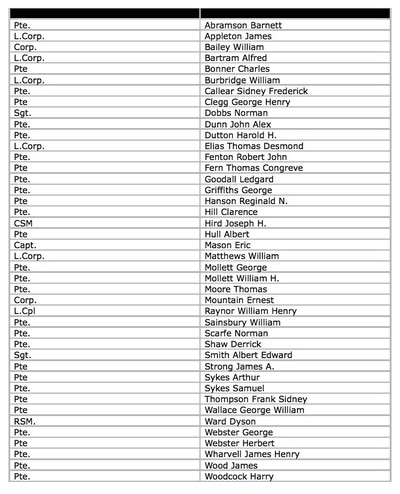

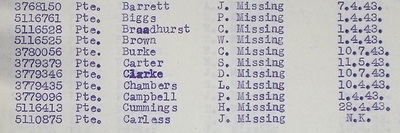

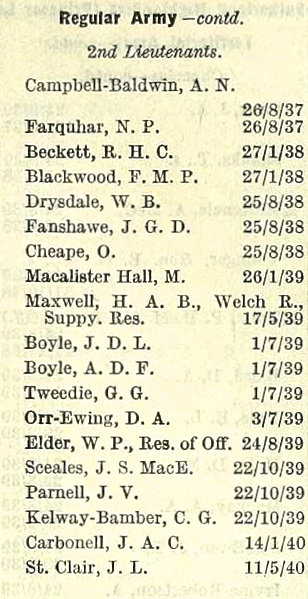

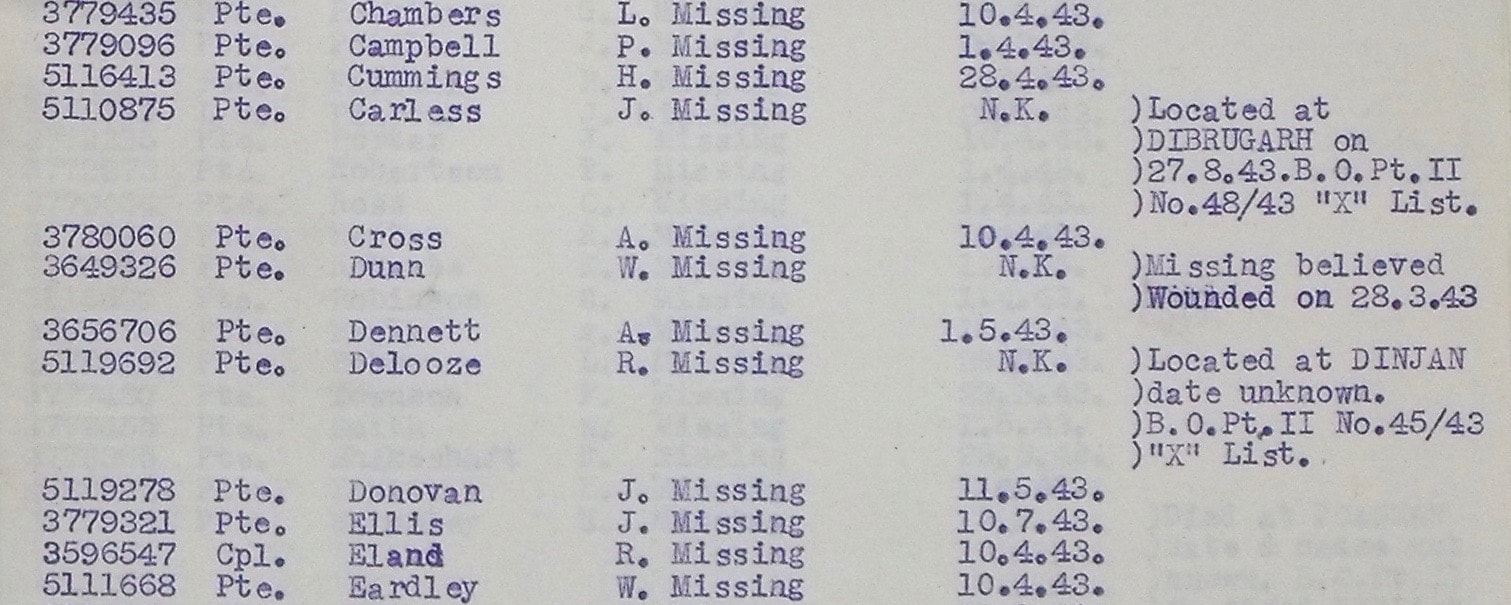

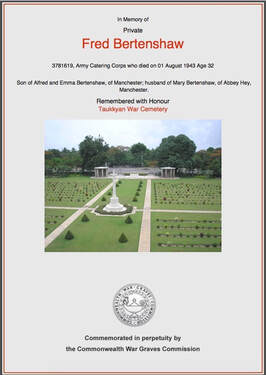

Surname A-E

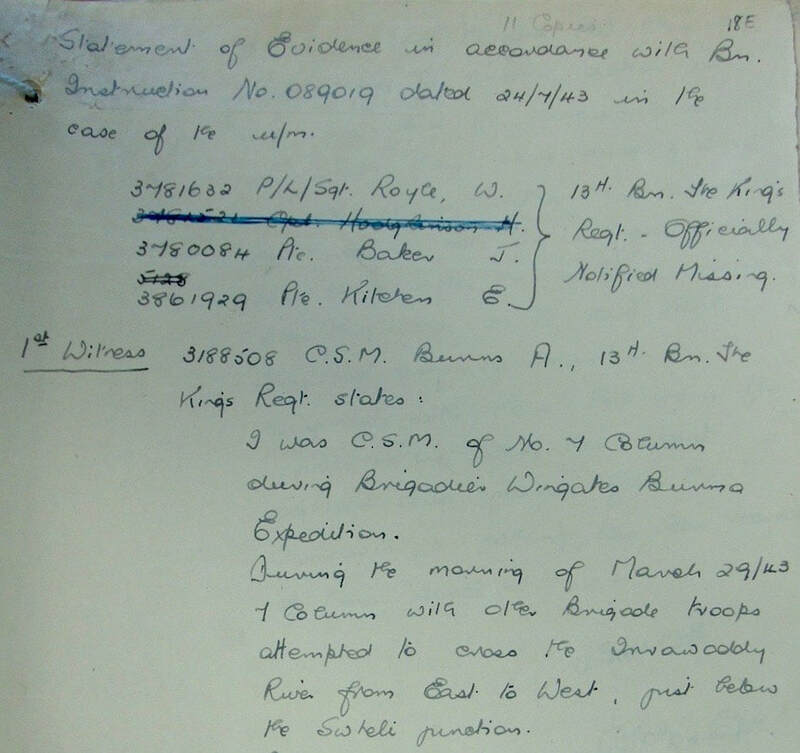

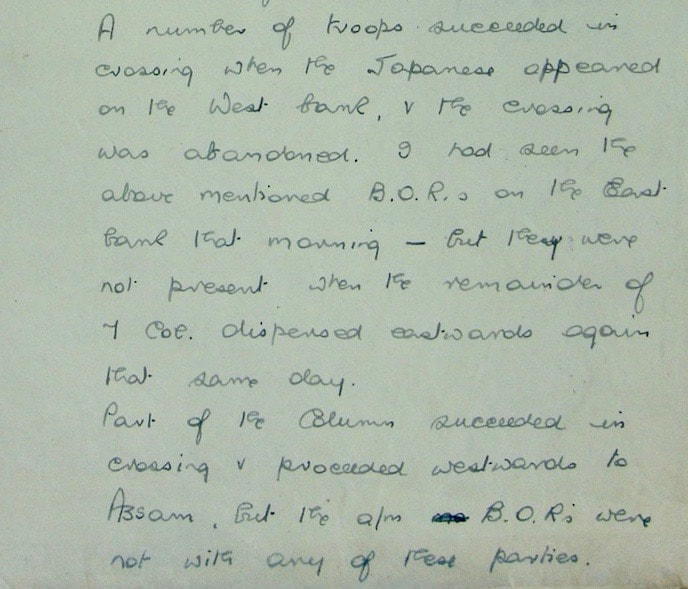

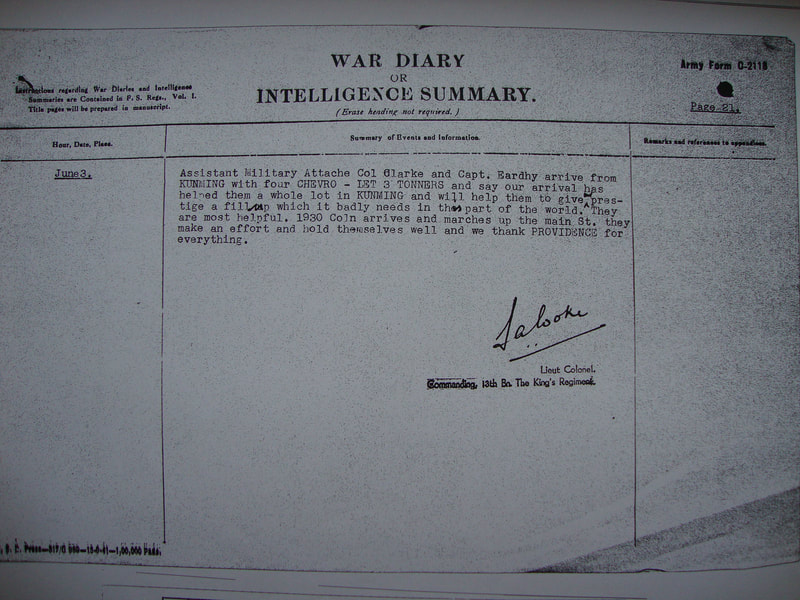

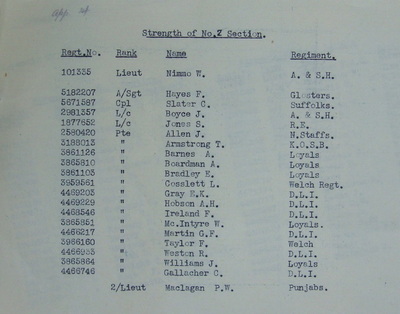

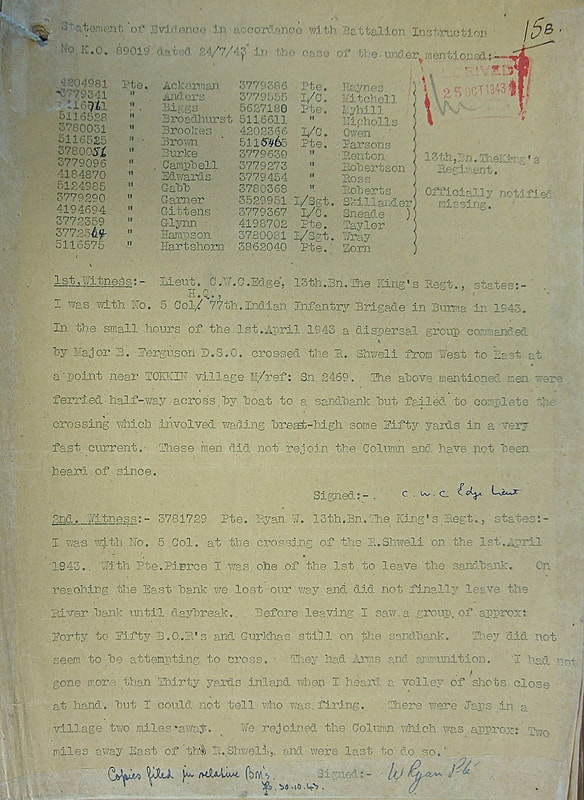

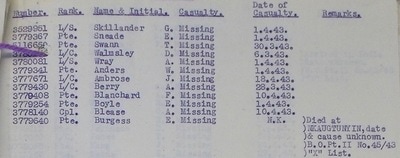

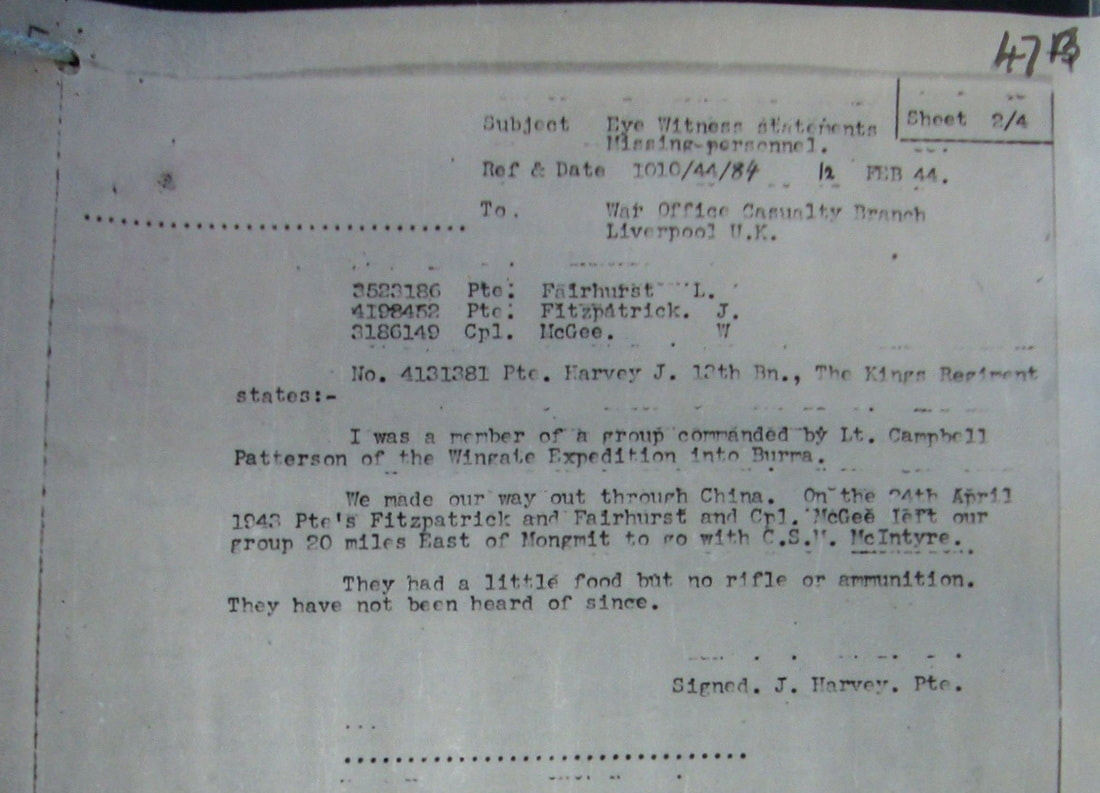

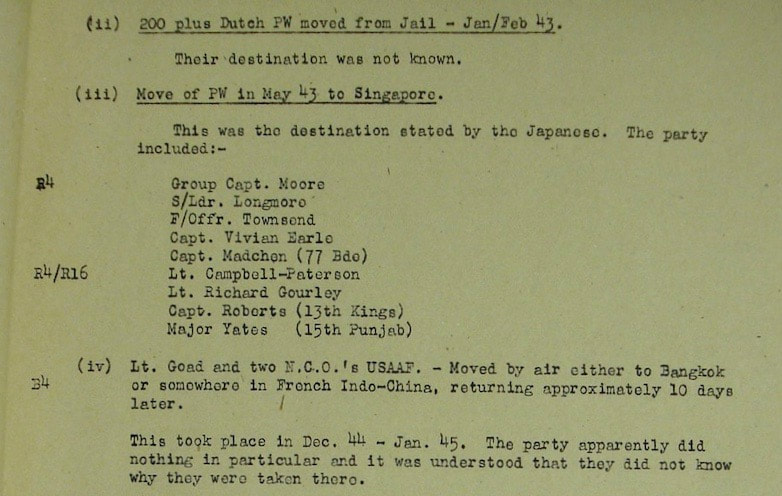

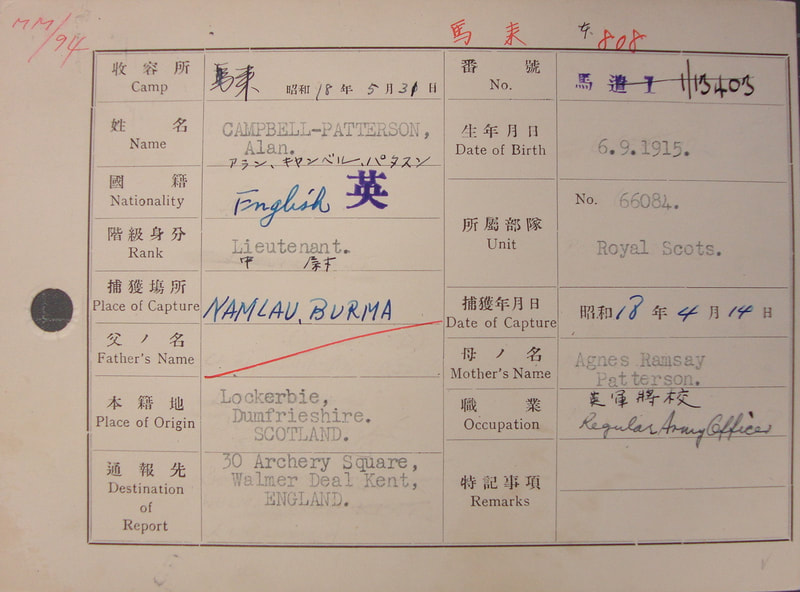

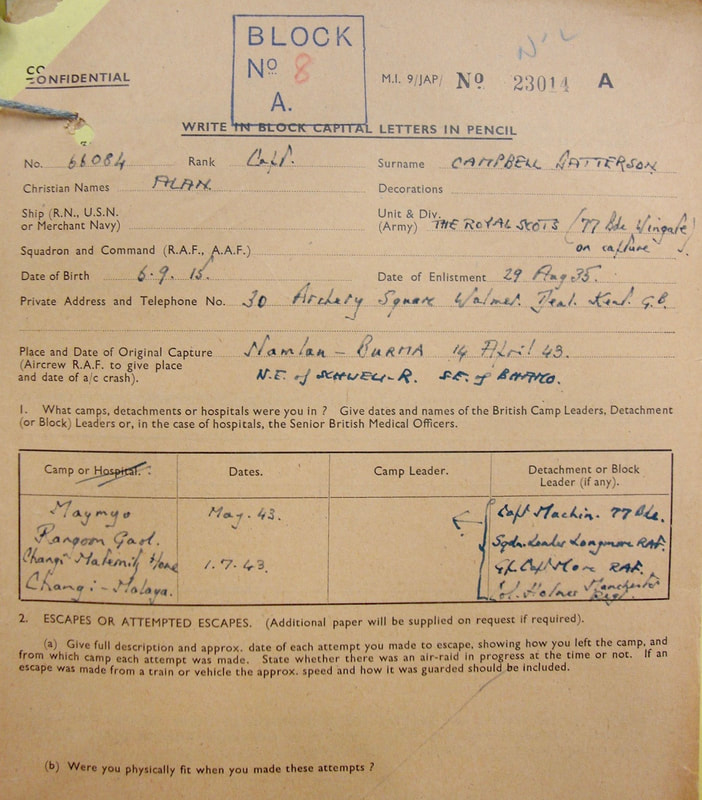

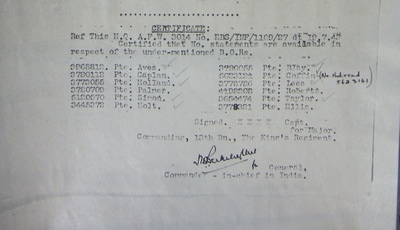

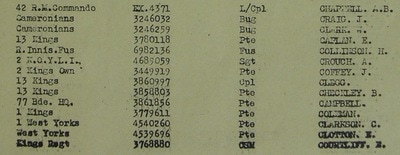

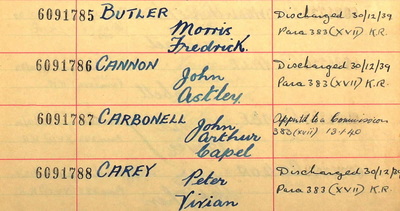

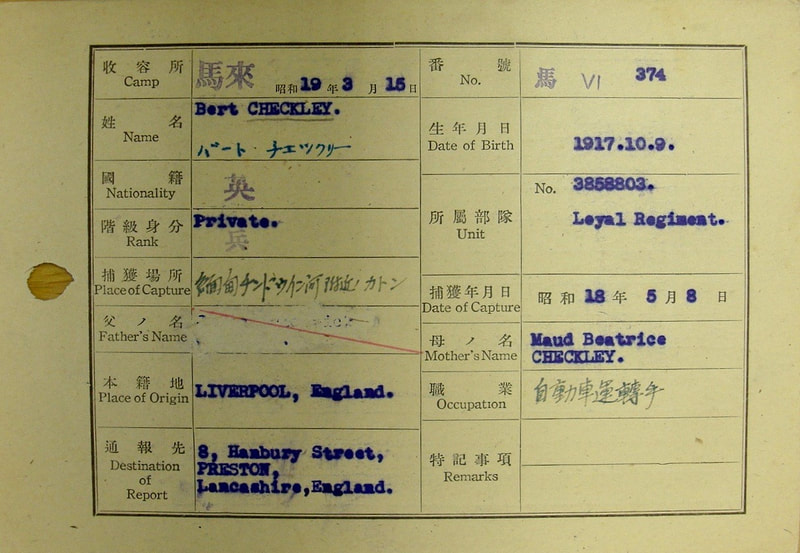

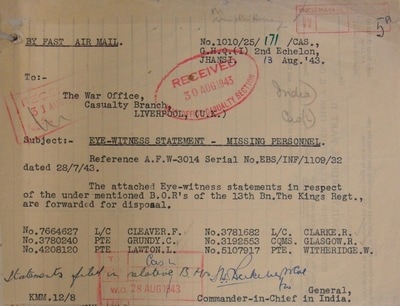

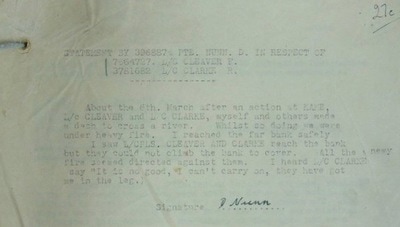

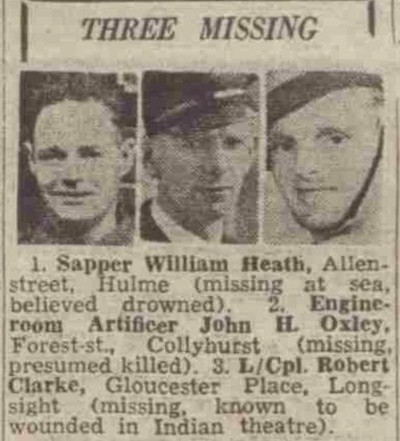

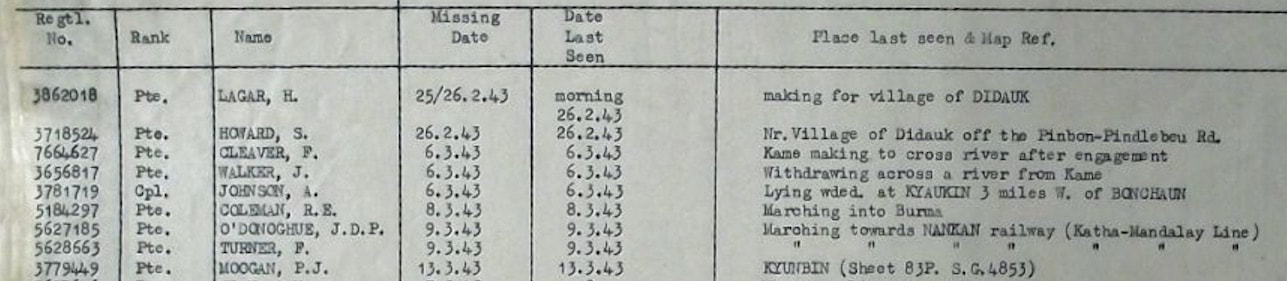

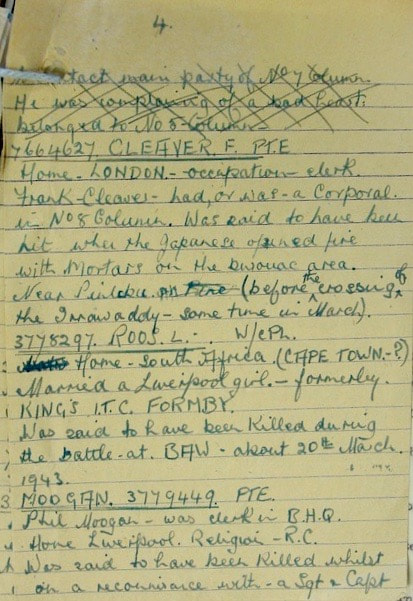

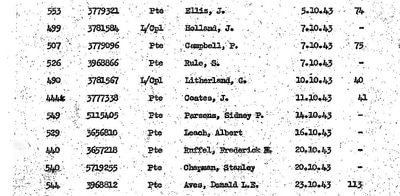

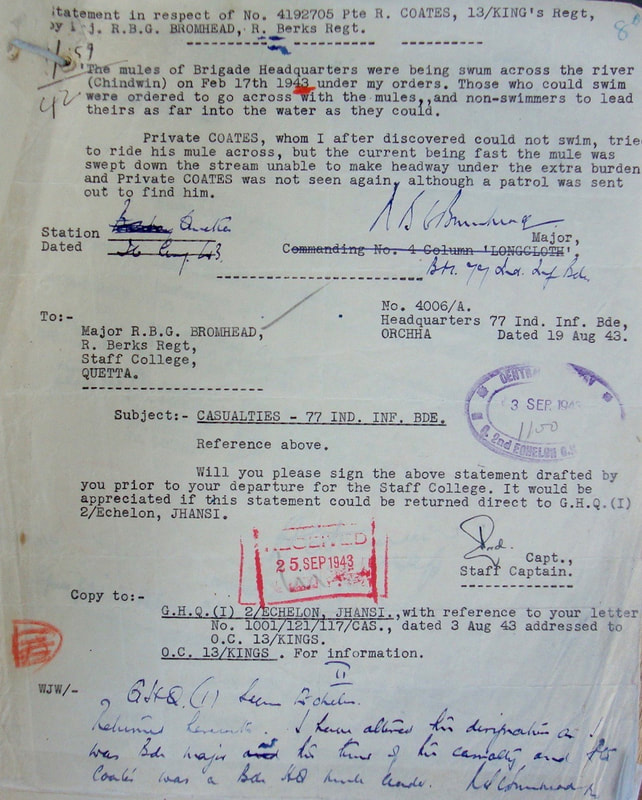

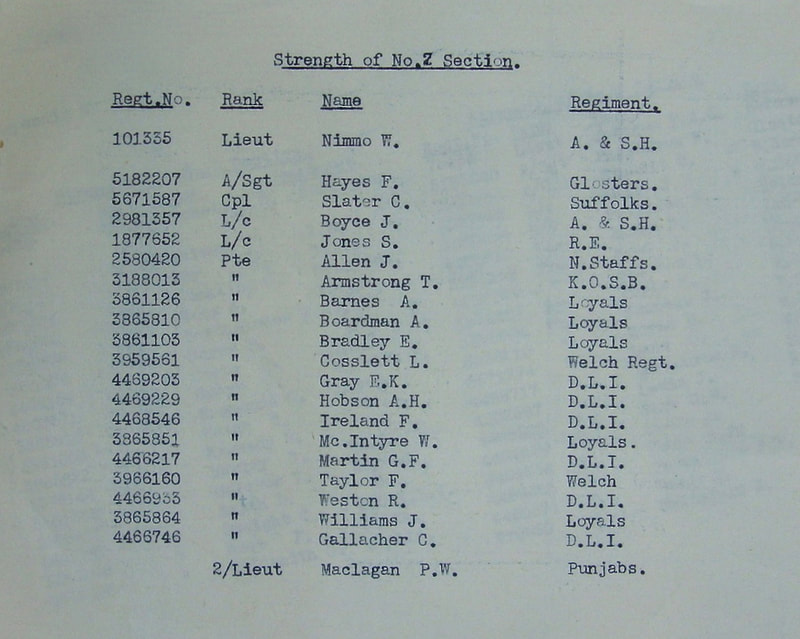

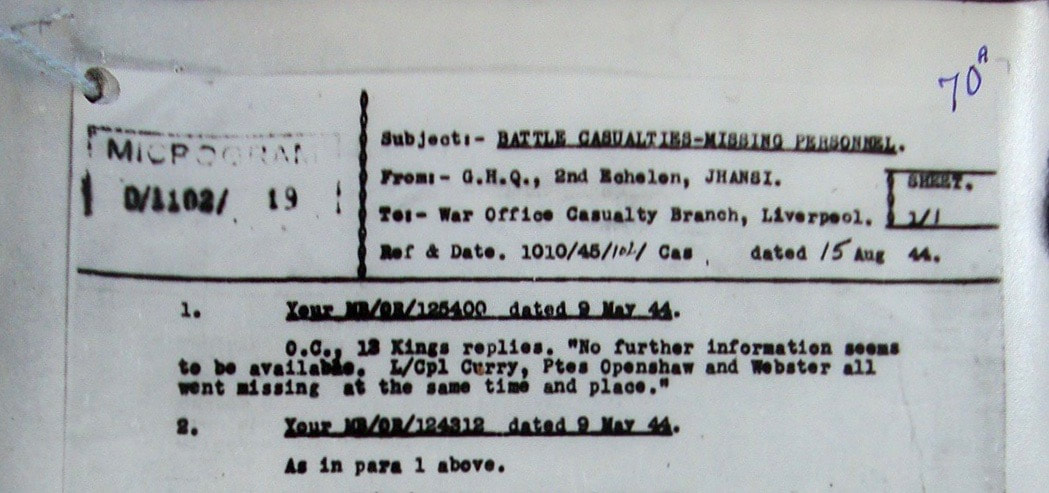

This section is an alphabetical roll of the men from Operation Longcloth. It takes its inspiration from other such formats available on the Internet, websites such as Special Forces Roll of Honour and of course the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). The information shown comes from various different documents related to the first Chindit Operation in 1943. Apart from more obvious data, such as the serviceman's rank, number and regimental unit, other detail has been taken from associated war diaries, missing in action files and casualty witness statements. The vast majority of this type of information has been located at the National Archives and the relevant file references can be found in the section Sources and Knowledge on this website.

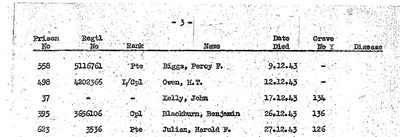

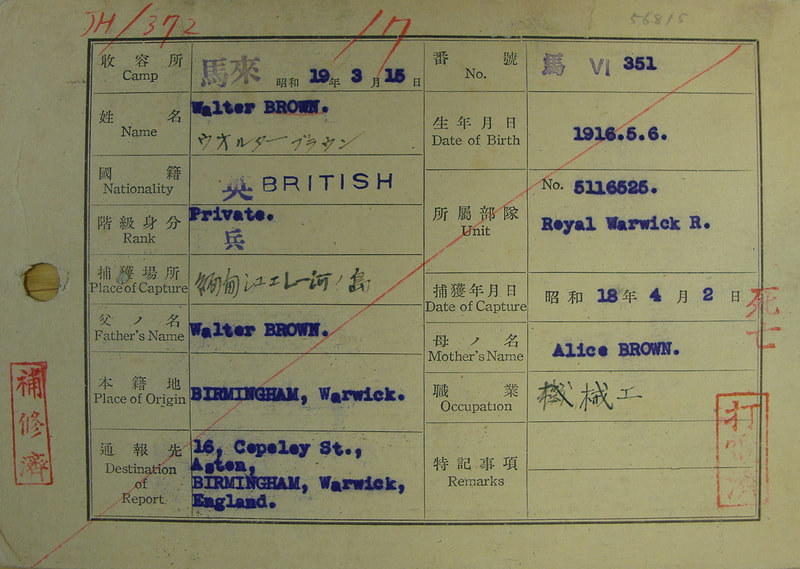

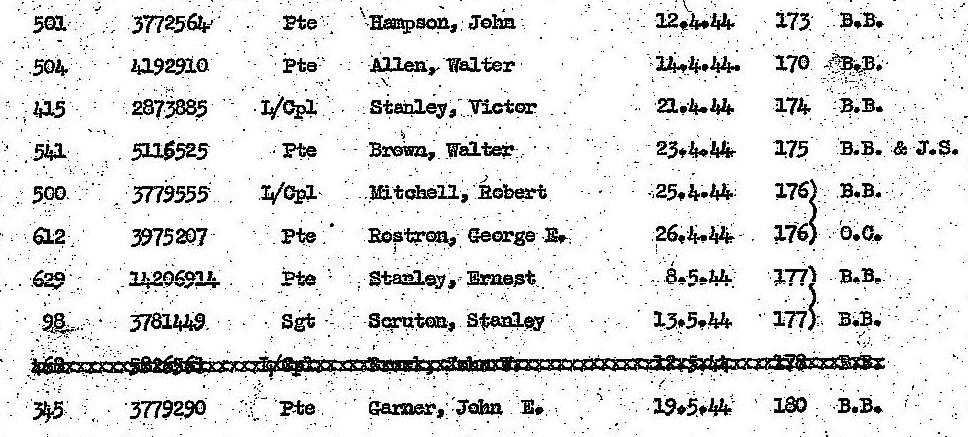

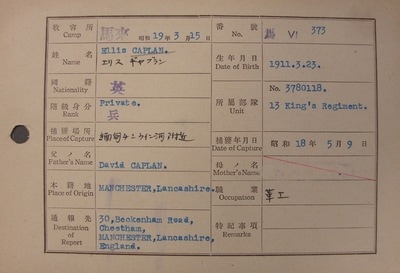

Sometimes, if the man in question became a prisoner of war more detail can be displayed showing his time whilst in Japanese hands. Other avenues for additional information are: books, personal diaries, veteran audio accounts and subsequent family input via letter, email and phone call.

The idea behind this page, is to include as many Longcloth participants as possible, even if there is only a small amount of information about their contribution to hand. Please click on any of the images to hopefully bring them forward on the page.

All information contained on this page is Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.

Sometimes, if the man in question became a prisoner of war more detail can be displayed showing his time whilst in Japanese hands. Other avenues for additional information are: books, personal diaries, veteran audio accounts and subsequent family input via letter, email and phone call.

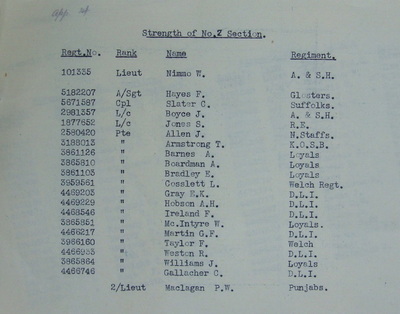

The idea behind this page, is to include as many Longcloth participants as possible, even if there is only a small amount of information about their contribution to hand. Please click on any of the images to hopefully bring them forward on the page.

All information contained on this page is Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.

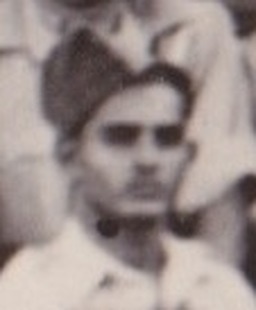

Abdul Khaliq, RIAOC.

Abdul Khaliq, RIAOC.

Abdul Khaliq

Rank: Armourer

Service No: Not known

Regiment/Service: Royal Indian Army Ordinance Corps att. The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

From the book 'Beyond the Chindwin', by Bernard Fergusson:

"We had collected at Jhansi a young Indian Armourer called Abdul Khaliq, a handsome, cheerful but helpless youth who was dubbed Abdul the Armourer, Abdul the Bulbul (by Tommy Roberts), or Abdul the Damned (by Duncan Menzies) as the fancy of the moment suggested.

Abdul was always one big grin, he spoke no English; but the men with whom he marched, not far behind me, taught him to call out whenever they were feeling tired, "Blow the bugle, Mr. Brookes," a refrain which Duncan and I incorporated into some frivolous verse"

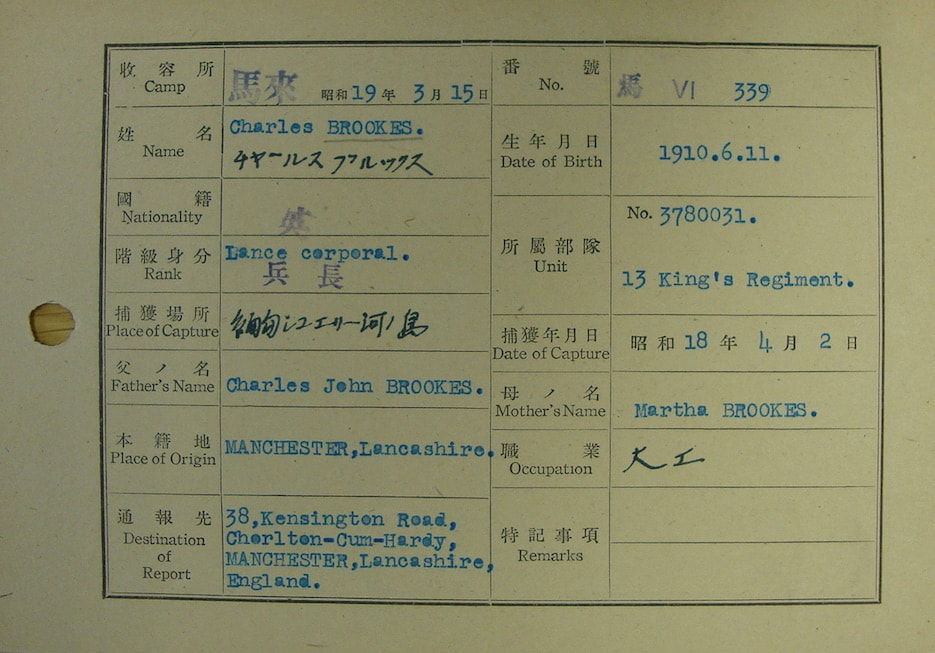

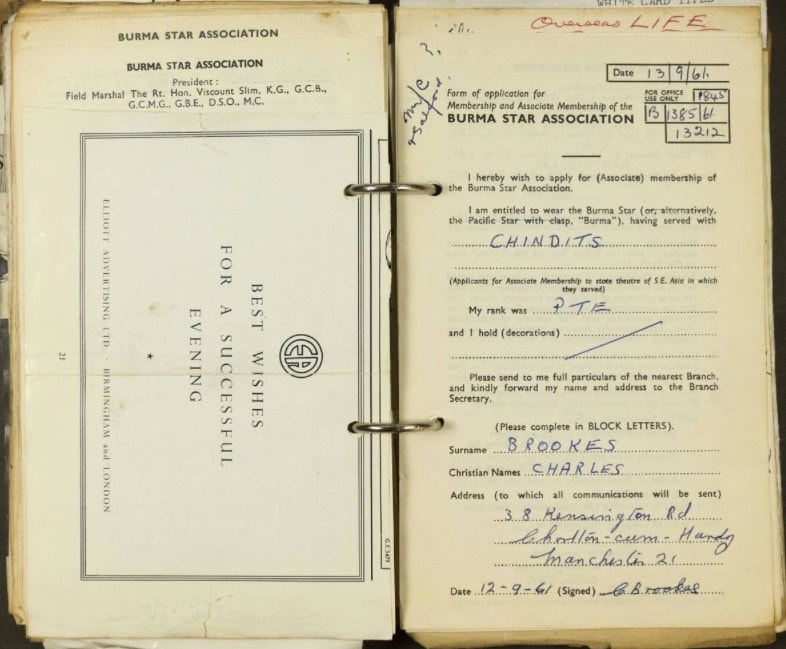

NB. Mr. Brookes was in fact Lance Corporal Charles Brookes, the Column bugler in 1943. Brookes was captured at the Shweli River in April, but survived his time as a POW and returned home to Manchester.

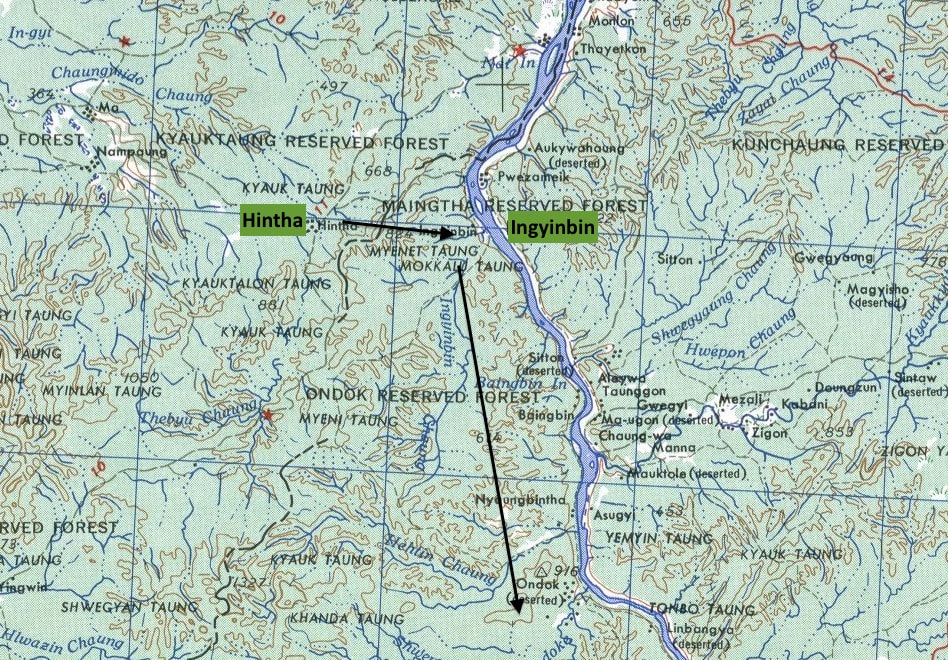

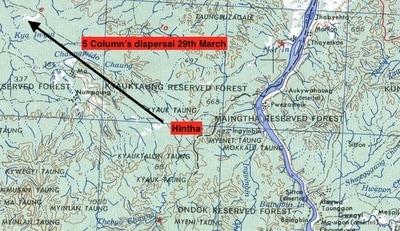

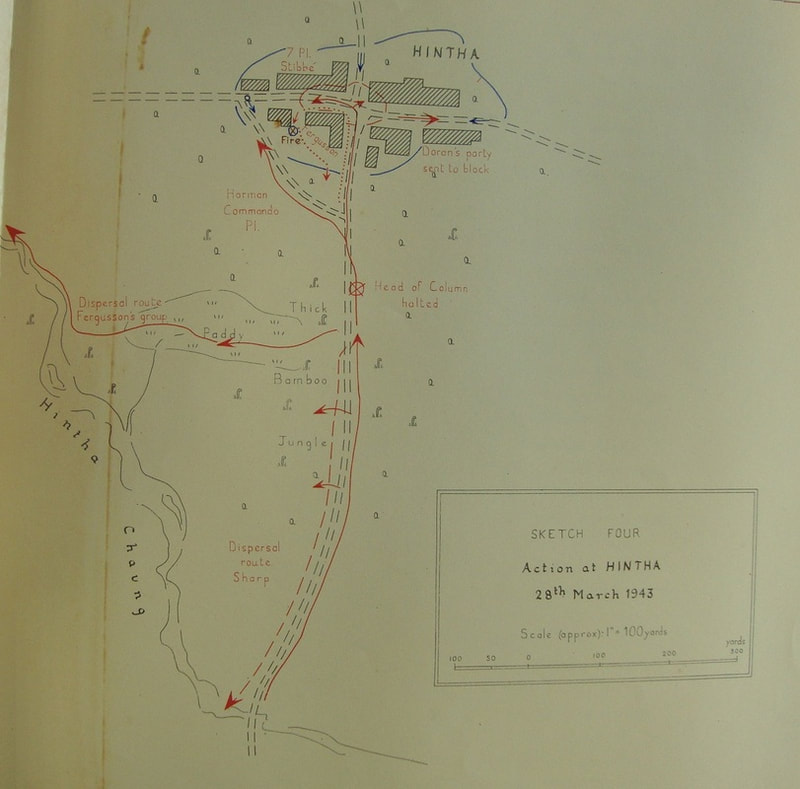

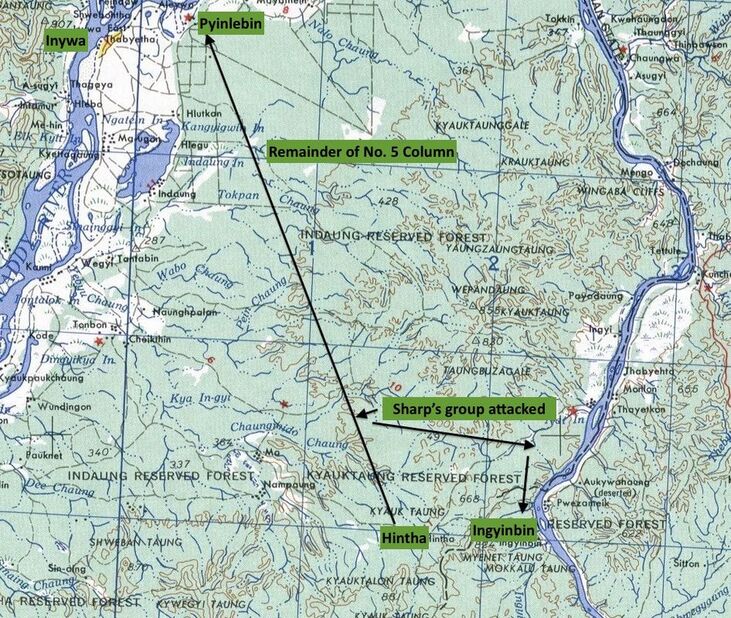

Abdul was wounded in the shoulder from Japanese mortar fire at the engagement in the village of Hintha. He had been looking after Lieutenant Campbell Menzies horse, but had been caught up in some cross fire, the horse had also been hit and had to be destroyed.

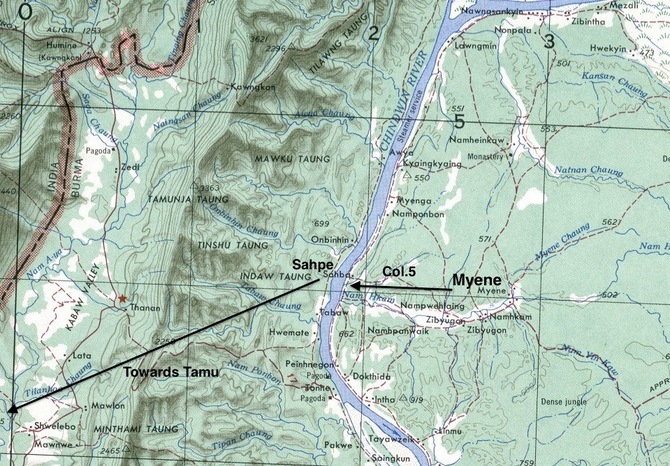

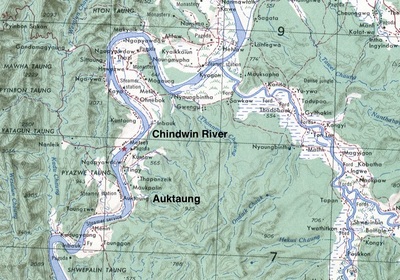

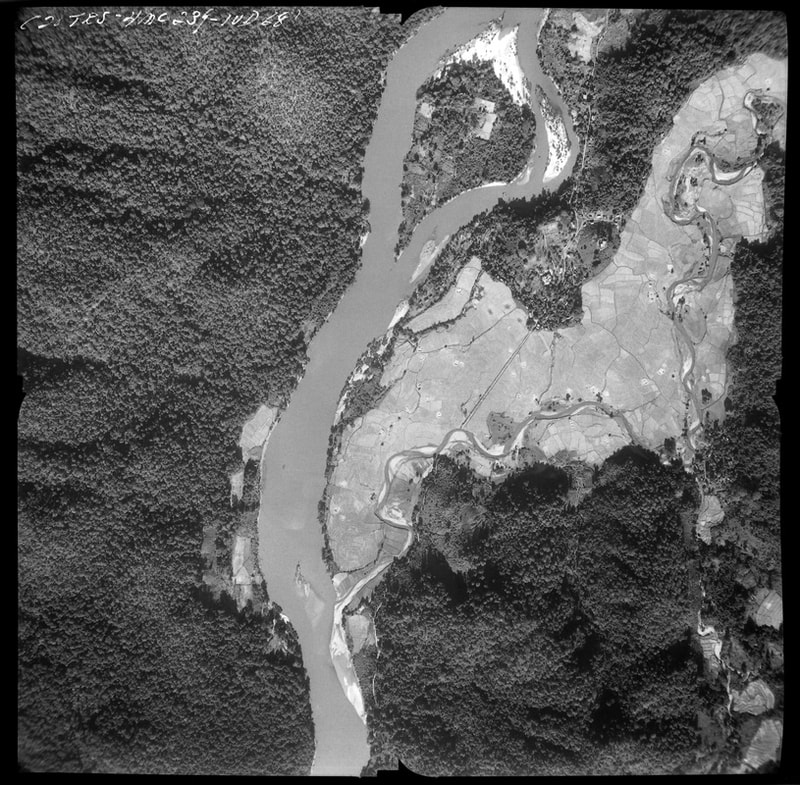

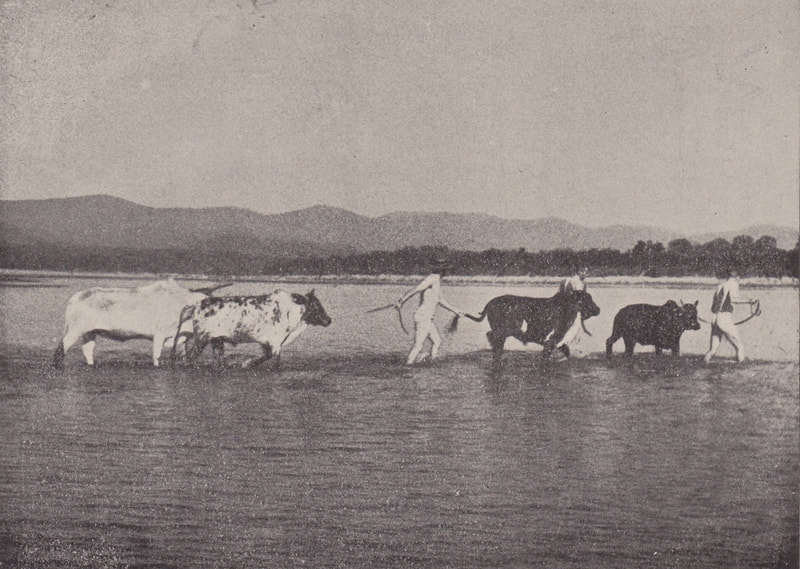

From here on, until the dispersal groups from Column 5 re-crossed the Chindwin River in late April, Abdul struggled both physically and emotionally with the exertions of the operation. He was pained by his injured shoulder and found most of the last one hundred miles very hard going indeed and almost gave up with some of the other men at the Shweli River crossing on April 1st. However, on the afternoon of the 24th April, between the villages of Myene and Sahpe, Abdul finally reached the west bank of the Chindwin and the safety of Allied held territory.

After some rest and their first hot meal in over a month the dispersal parties from Column 5 were moved back to the town of Tamu on the Assam/Burma border. Here at Tamu they were given more hot food, a bath, shave and a welcome change of clothes.

Rank: Armourer

Service No: Not known

Regiment/Service: Royal Indian Army Ordinance Corps att. The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

From the book 'Beyond the Chindwin', by Bernard Fergusson:

"We had collected at Jhansi a young Indian Armourer called Abdul Khaliq, a handsome, cheerful but helpless youth who was dubbed Abdul the Armourer, Abdul the Bulbul (by Tommy Roberts), or Abdul the Damned (by Duncan Menzies) as the fancy of the moment suggested.

Abdul was always one big grin, he spoke no English; but the men with whom he marched, not far behind me, taught him to call out whenever they were feeling tired, "Blow the bugle, Mr. Brookes," a refrain which Duncan and I incorporated into some frivolous verse"

NB. Mr. Brookes was in fact Lance Corporal Charles Brookes, the Column bugler in 1943. Brookes was captured at the Shweli River in April, but survived his time as a POW and returned home to Manchester.

Abdul was wounded in the shoulder from Japanese mortar fire at the engagement in the village of Hintha. He had been looking after Lieutenant Campbell Menzies horse, but had been caught up in some cross fire, the horse had also been hit and had to be destroyed.

From here on, until the dispersal groups from Column 5 re-crossed the Chindwin River in late April, Abdul struggled both physically and emotionally with the exertions of the operation. He was pained by his injured shoulder and found most of the last one hundred miles very hard going indeed and almost gave up with some of the other men at the Shweli River crossing on April 1st. However, on the afternoon of the 24th April, between the villages of Myene and Sahpe, Abdul finally reached the west bank of the Chindwin and the safety of Allied held territory.

After some rest and their first hot meal in over a month the dispersal parties from Column 5 were moved back to the town of Tamu on the Assam/Burma border. Here at Tamu they were given more hot food, a bath, shave and a welcome change of clothes.

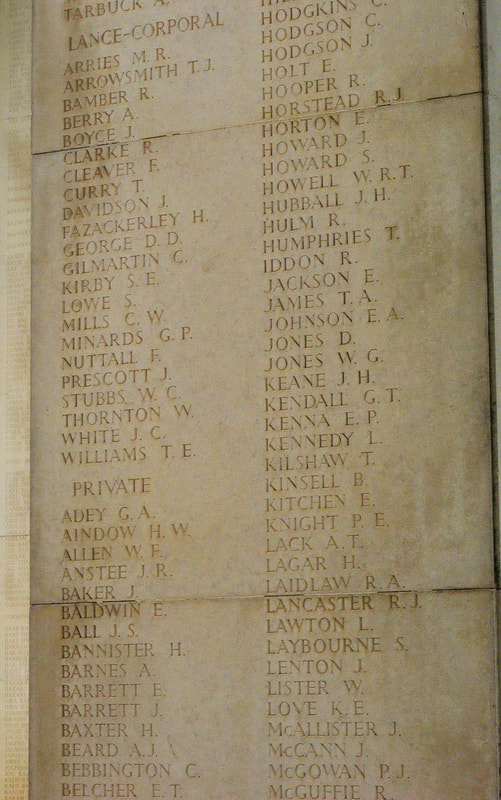

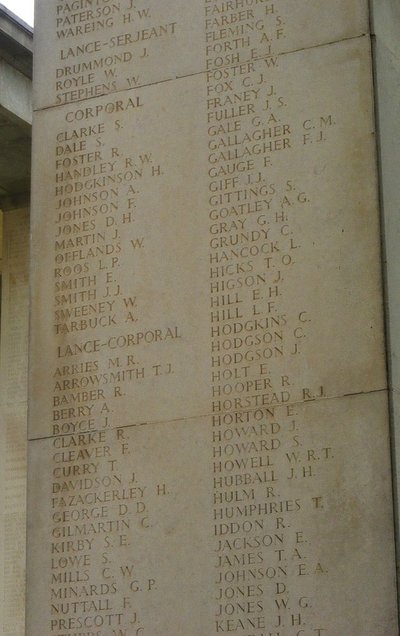

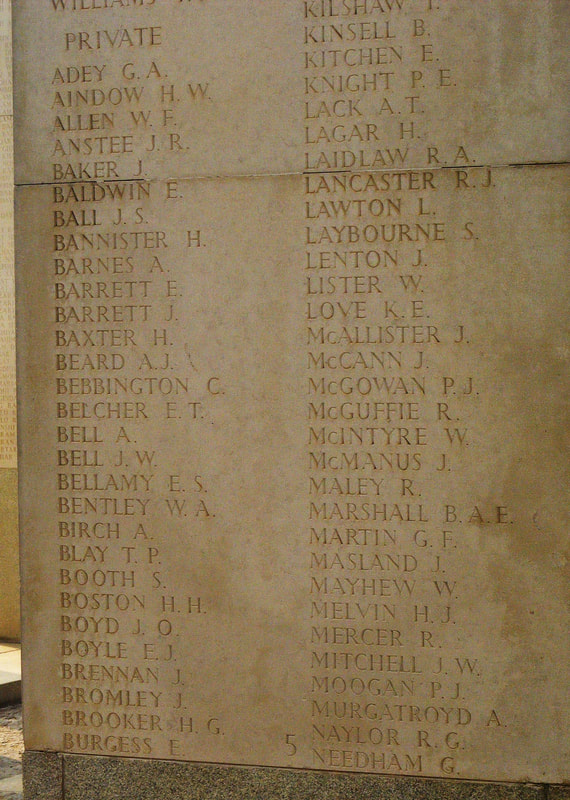

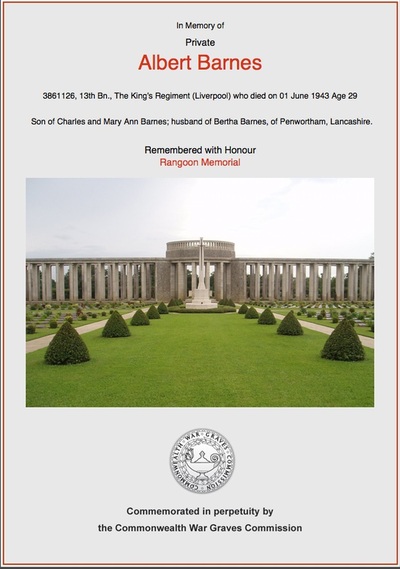

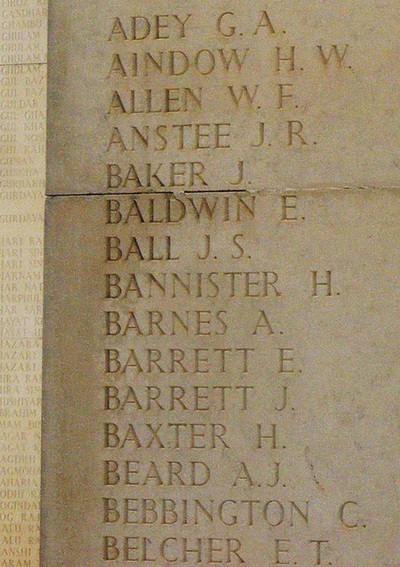

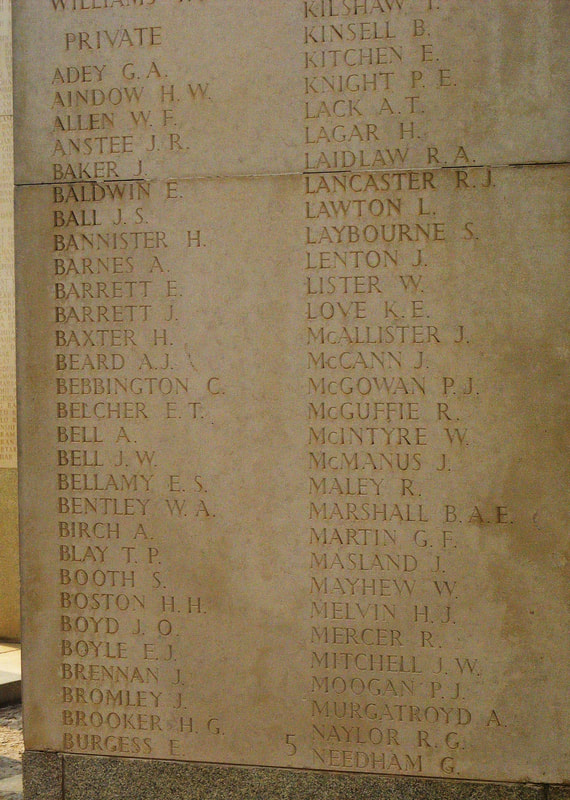

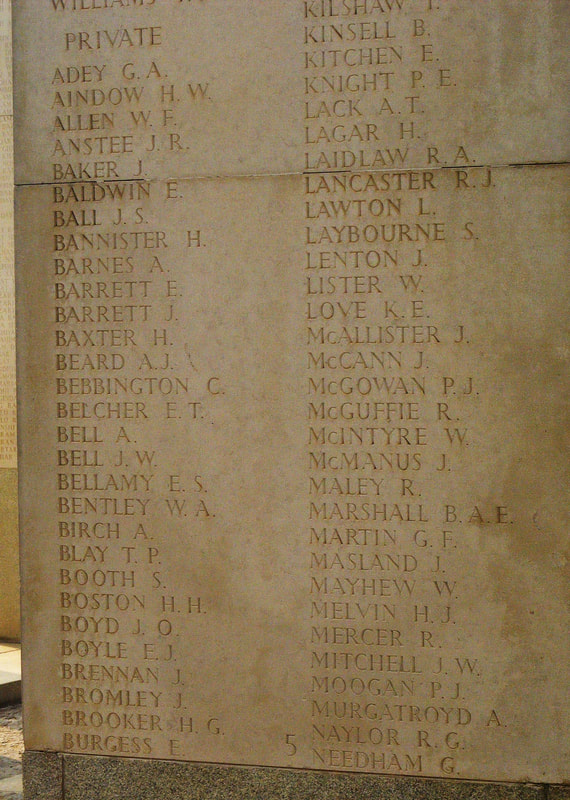

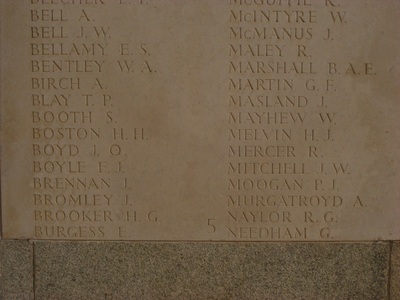

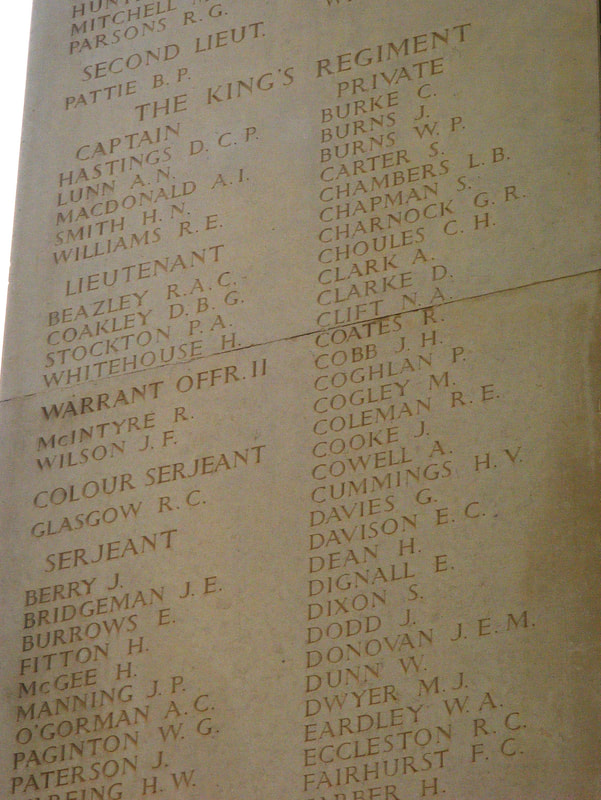

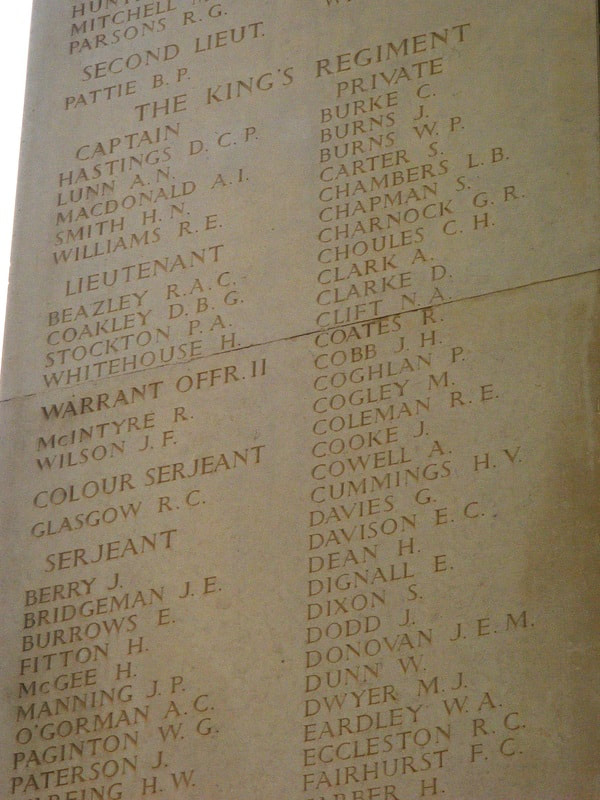

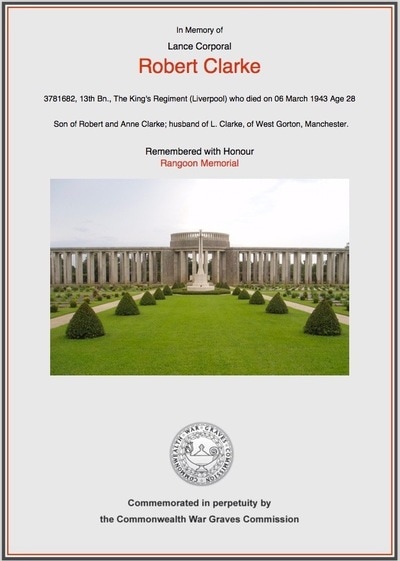

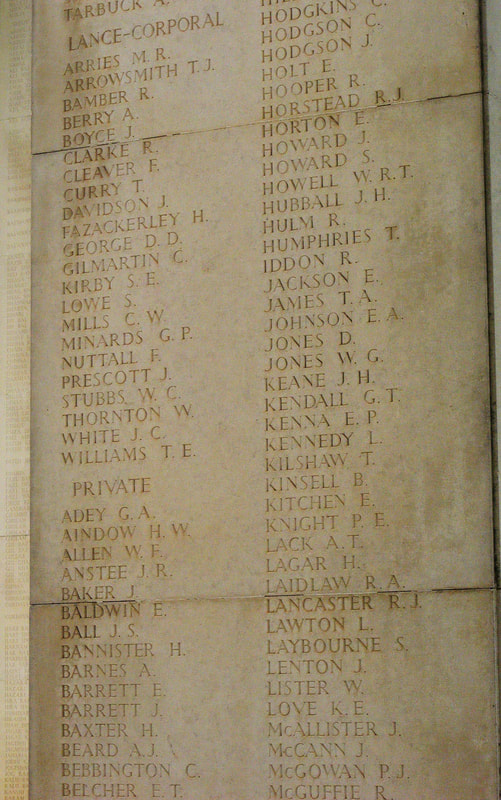

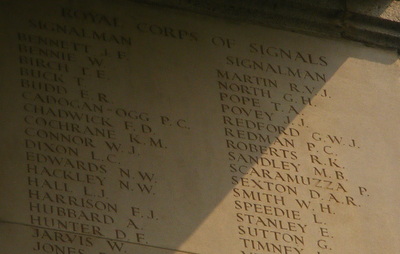

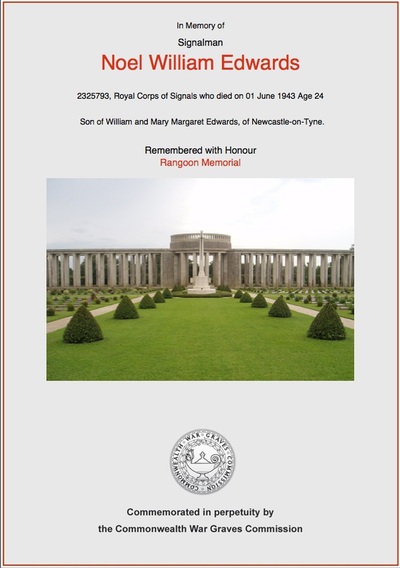

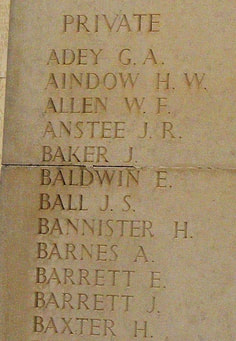

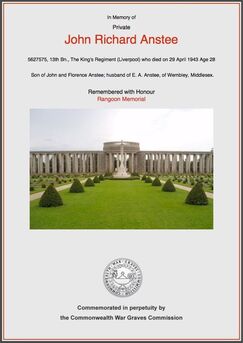

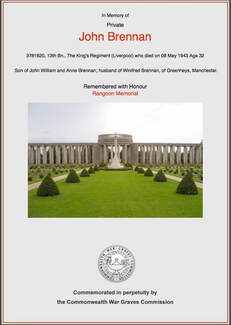

Rangoon Memorial Face 5.

Rangoon Memorial Face 5.

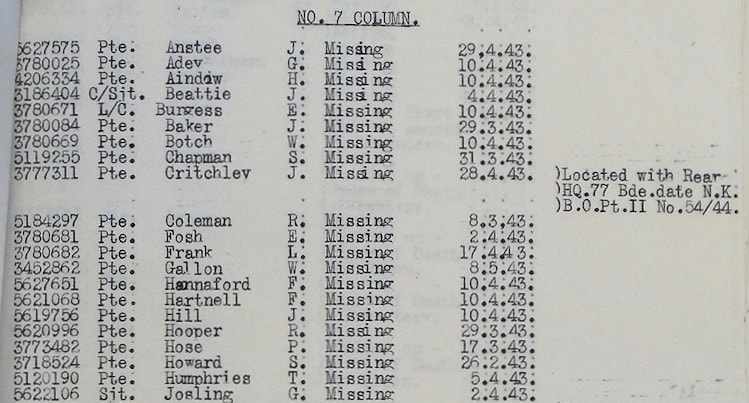

ADEY, GEORGE

Rank: Private

Service No: 3780025

Date of Death: 10/04/1943

Age: 31

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery, Face 5.

CWGC link: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2130500/ADEY,%20GEORGE

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

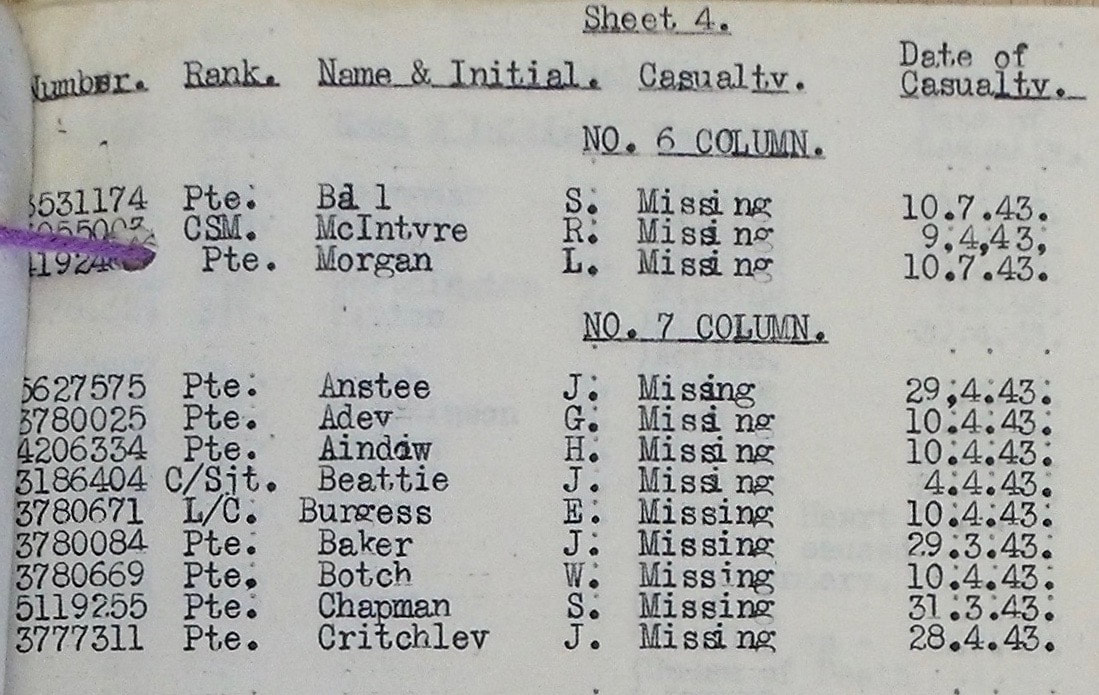

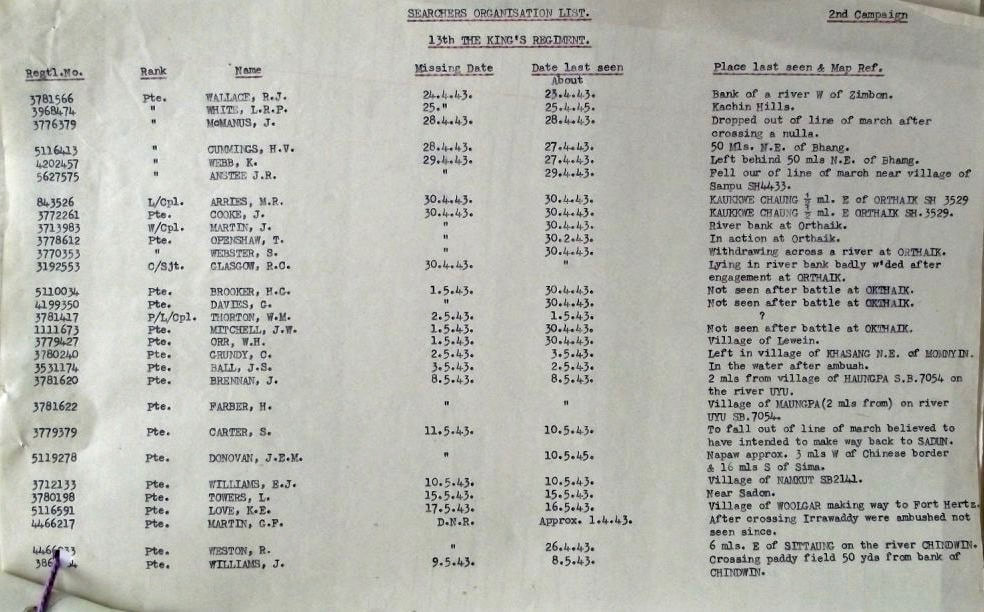

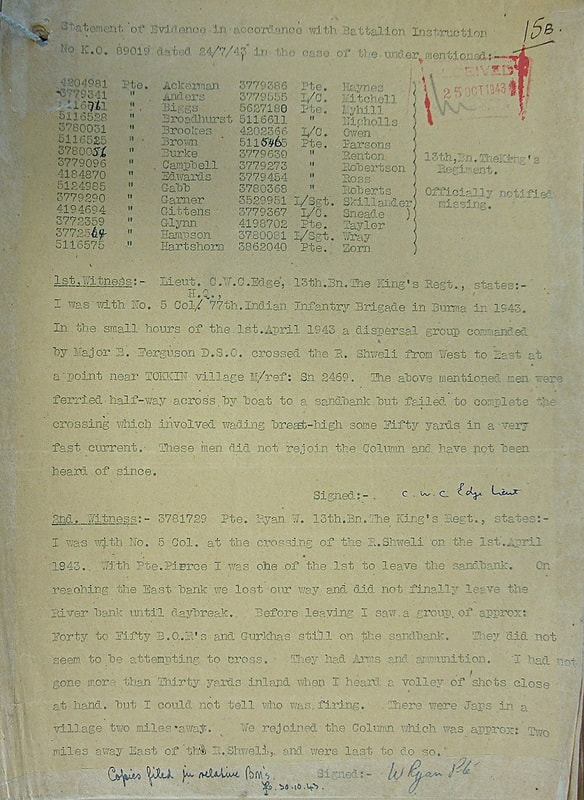

Witness Reports from surviving members of Column 7:

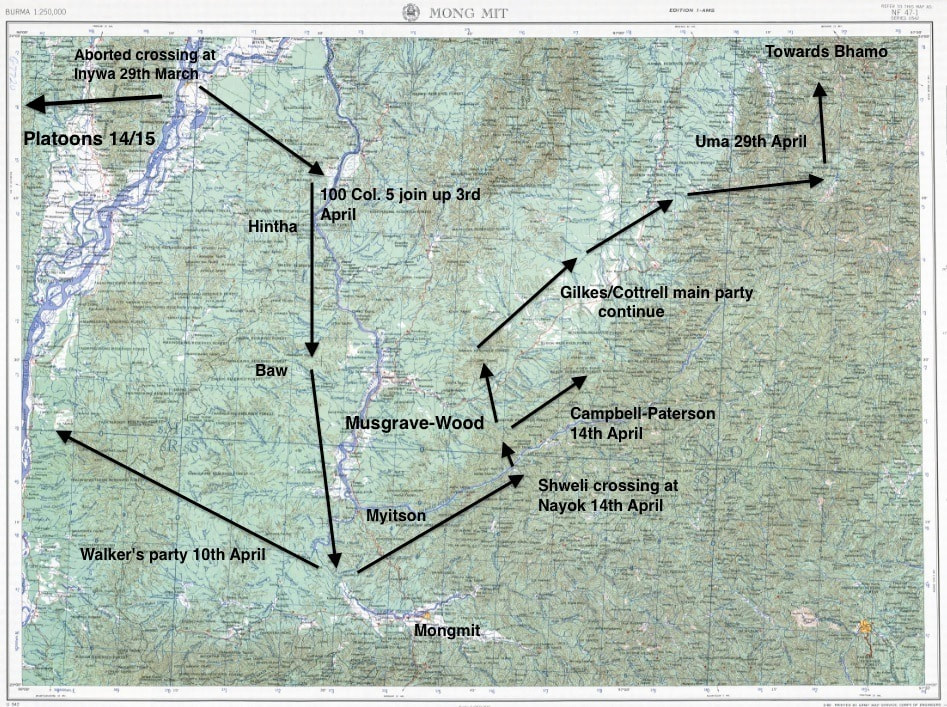

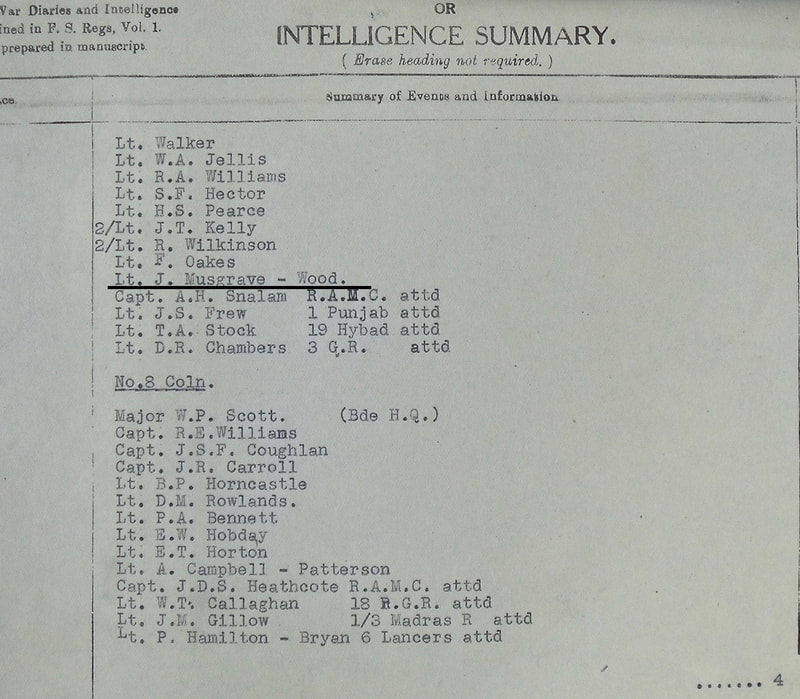

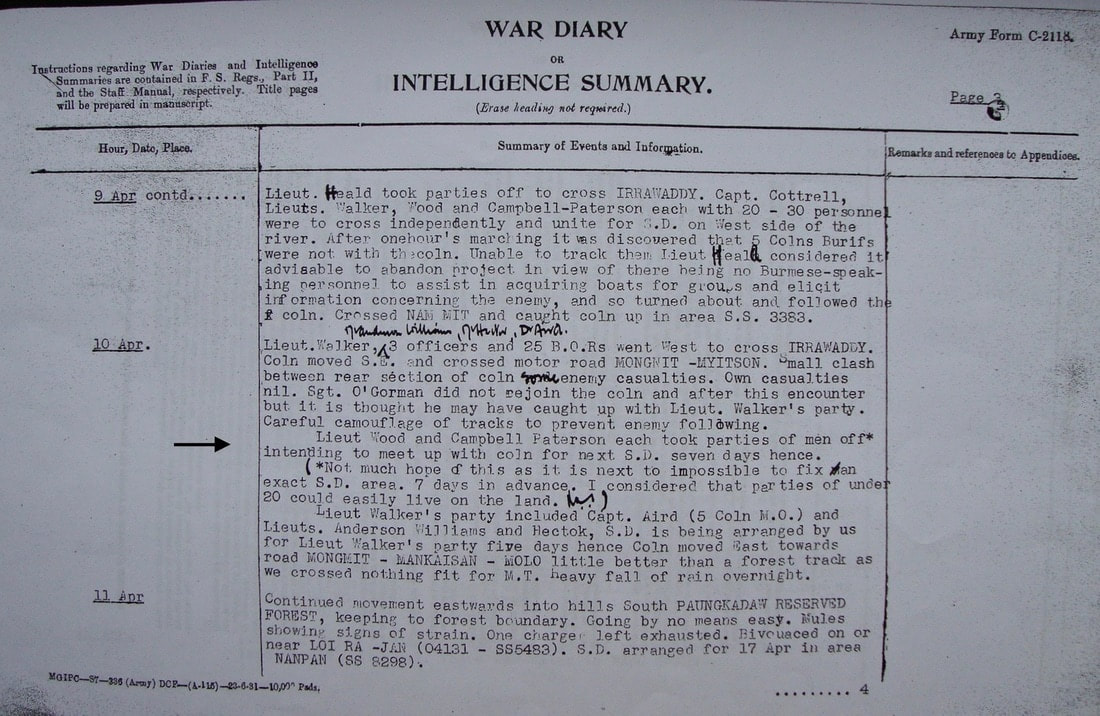

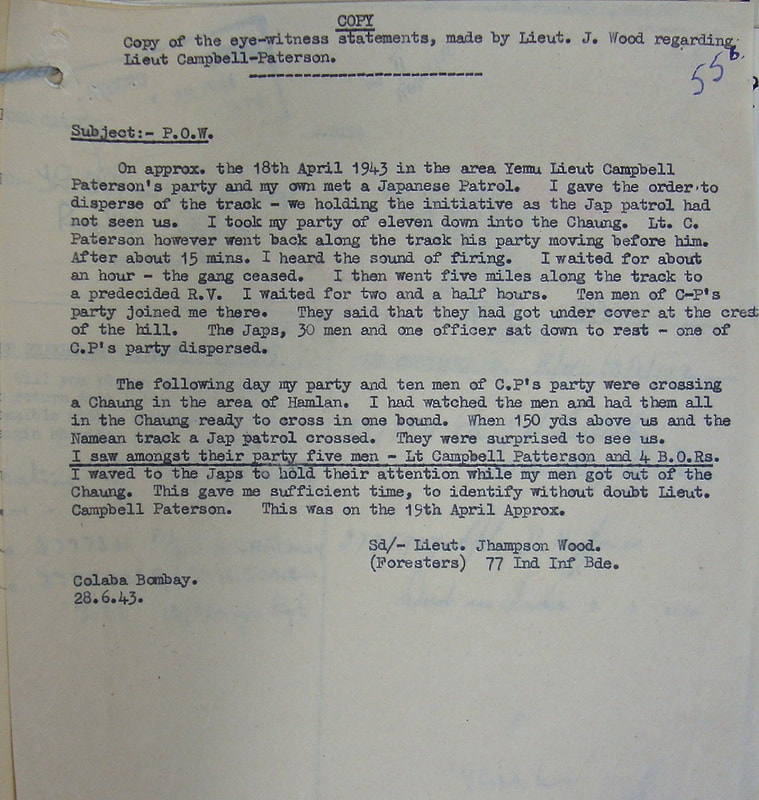

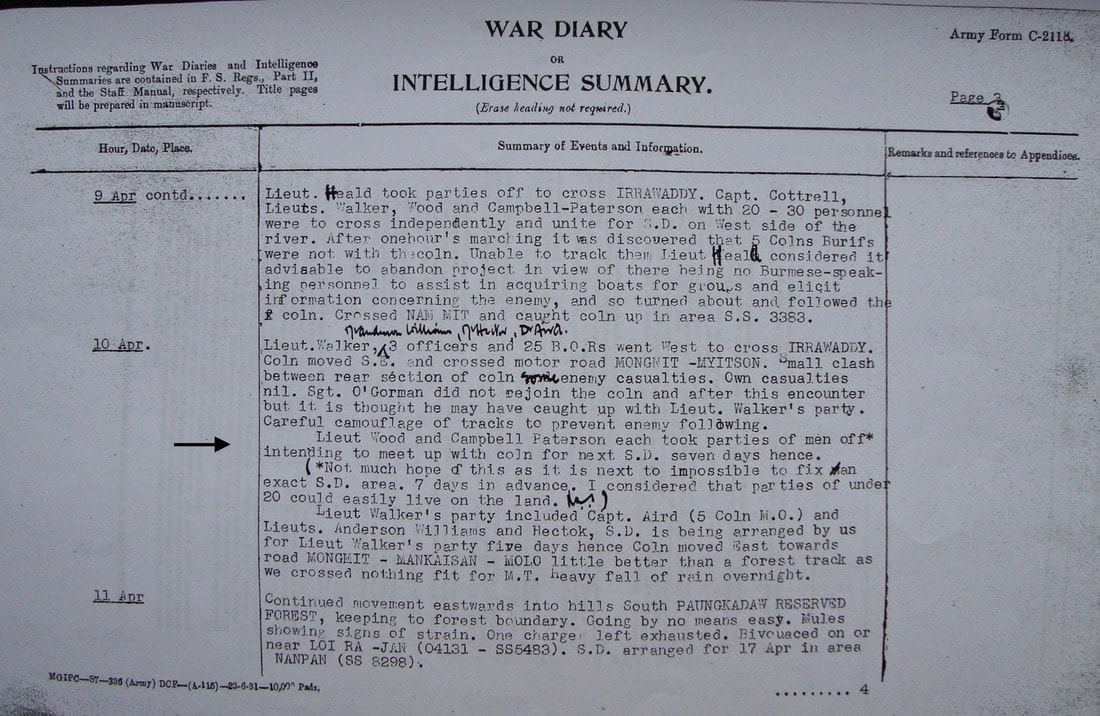

Statement extract of Captain Leslie Cottrell: "On April 10th the Column commander (Major K. Gilkes) decided for various tactical and administrative reasons to split the Column. This was mid-way between the towns of Mongmit and Myitson, just east of the Nammit and Mongmit/Myitson Road. Lieutenant R. Walker was ordered to take charge of a party of three officers and twenty-one other ranks."

For more information about the fate of this dispersal party led by Lieutenant Rex Walker, please follow the link below: Dispersal Group 4

This dispersal group did not fare well and none of the men made it back to India in 1943. The few survivors from the party who did eventually make it home would have to endure nearly two years as prisoners in Japanese hands. George Adey was not one of these fortunate few. From a very short statement provided by Corporal J. Kennedy, we now know that Pte. Adey fell out of the line of march ten days after the dispersal group was formed. Kennedy does not say why this happened, simply informing the investigatory authorities that it occurred on or about the 20th April 1943. It is quite possible that George may have become a prisoner of war and was held captive by the Japanese at some point during those ten unaccounted for days.

You may notice that George Adey is given the 10th April as his date of death by the CWGC. This is because the Commission would have used the last date that his whereabouts were officially known to a superior officer, in this case, the day the dispersal groups were allocated by Major Gilkes.

Rank: Private

Service No: 3780025

Date of Death: 10/04/1943

Age: 31

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery, Face 5.

CWGC link: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2130500/ADEY,%20GEORGE

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

Witness Reports from surviving members of Column 7:

Statement extract of Captain Leslie Cottrell: "On April 10th the Column commander (Major K. Gilkes) decided for various tactical and administrative reasons to split the Column. This was mid-way between the towns of Mongmit and Myitson, just east of the Nammit and Mongmit/Myitson Road. Lieutenant R. Walker was ordered to take charge of a party of three officers and twenty-one other ranks."

For more information about the fate of this dispersal party led by Lieutenant Rex Walker, please follow the link below: Dispersal Group 4

This dispersal group did not fare well and none of the men made it back to India in 1943. The few survivors from the party who did eventually make it home would have to endure nearly two years as prisoners in Japanese hands. George Adey was not one of these fortunate few. From a very short statement provided by Corporal J. Kennedy, we now know that Pte. Adey fell out of the line of march ten days after the dispersal group was formed. Kennedy does not say why this happened, simply informing the investigatory authorities that it occurred on or about the 20th April 1943. It is quite possible that George may have become a prisoner of war and was held captive by the Japanese at some point during those ten unaccounted for days.

You may notice that George Adey is given the 10th April as his date of death by the CWGC. This is because the Commission would have used the last date that his whereabouts were officially known to a superior officer, in this case, the day the dispersal groups were allocated by Major Gilkes.

Rangoon Memorial, Face 5.

Rangoon Memorial, Face 5.

AINDOW, HENRY WILLIAM

Rank: Private

Service No: 4206334

Date of Death: 01/06/1943

Age:21

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery, Face 5.

CWGC link: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2130644/AINDOW,%20HENRY%20WILLIAM

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

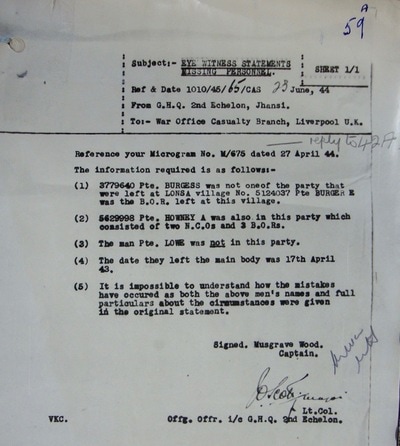

Henry Aindow just like George Adey (see entry above), was also part of the Column 7 dispersal group led by Rex Walker. This former Royal Welch Fusilier had joined Chindit training in late September 1942 along with a small draft of other men from this unit. Not much is known about Henry's movements after the 10th of April and there seems to be conflicting evidence from two separate witness statements concerning his fate in 1943. For a more detailed account in regard to Lieutenant Walker's dispersal group, please click on the link below: Dispersal Group 4

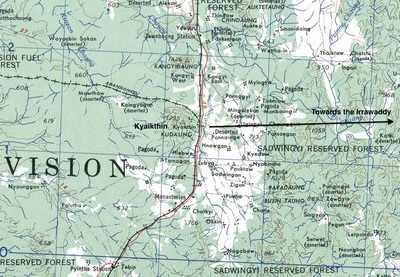

From the evidence given in the witness statements it seems fairly certain that Pte. Aindow had fallen in to Japanese hands in April 1943, but that he had not survived for long as a POW and certainly did not make the journey down to Rangoon Jail with the other Chindit prisoners. The official information given for his last known whereabouts states: "Pte. Aindow was last seen marching westward towards the Irrawaddy, but failed to make the planned rendezvous with other dispersal groups."

The first witness statement was given by Pte. Thomas Worthington, a Liverpudlian by birth and another member of Column 7. Thomas was also captured by the Japanese during Operation Longcloth and had survived his two years as a POW in Rangoon. On his return home Thomas had taken the trouble to write down everything he could remember about his lost and fallen comrades from the expedition in 1943. His five page letter included this short sentence concerning Henry Aindow:

"Pte. Aindow, formerly with the R.W.F. was from Crosby near Liverpool. I last saw him in a hospital in either Calore or Kalawa, he was suffering from dysentery. The fittest of his party were sent on to Rangoon via Maymyo. Major Ramsay-R.A.M.C. our Medical Officer was in charge."

NB. Thomas Worthington obviously could not be sure which was the correct spelling for the transit camp at Kalawa where many captured Chindits were held for a short time before being sent on to the main concentration camp at Maymyo. Once collected together at Maymyo, the 200 or so Chindit men were put through a vicious and brutal POW acclimatisation regime, before finally being sent down to Rangoon Jail. Major Raymond Ramsay was the senior Medical Officer on Operation Longcloth in 1943.

The inference from Thomas Worthington's statement is that Henry Aindow never left the camp at Kalawa. The second witness statement also comes in the form of a letter written back in England after the war was over. Corporal John Kennedy survived his time in Rangoon Jail and returned home to his family, in his letter dated 17th November 1945 he recalls what another Chindit POW had told him about the fate of Henry Aindow.

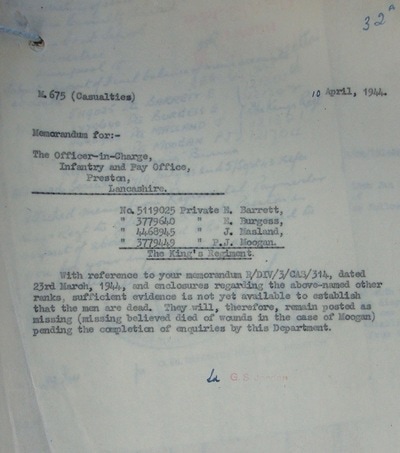

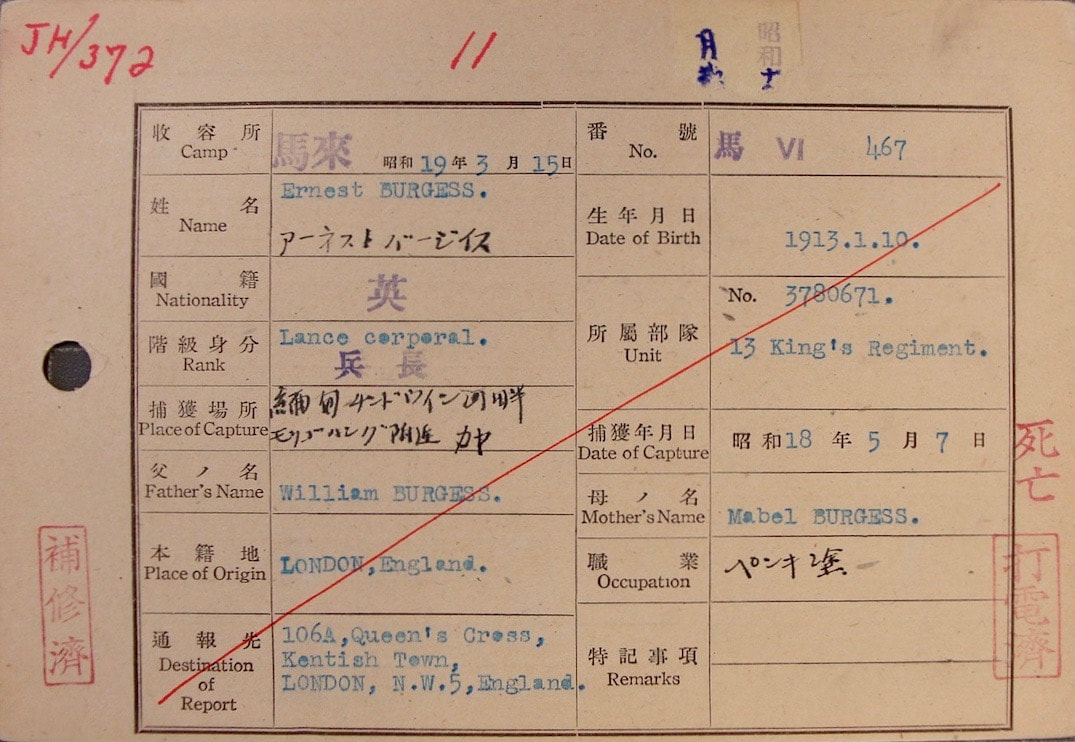

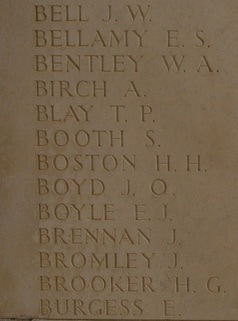

Lance Corporal Ernest Burgess was another member of Column 7 in 1943 and was, like Kennedy and Aindow, a member of Dispersal Group 4 that year. Ernest Burgess had told Kennedy what had happened to Pte. Aindow shortly before his own sad death in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail in March 1944. The disturbing information given by Burgess, stated that Henry had been killed by Burmese villagers who had been helping the Japanese at that time. He added that this murder took place on the 6th May 1943. It is difficult to speculate what actually happened to Pte. Aindow, but it seems likely that he may have become so ill or exhausted that the Japanese ordered the treacherous Burmese to dispose of him on their behalf.

NB. You may notice that the CWGC information gives Henry Aindow's date of death as 01/06/1943. This date I have found during my research, seems to be universally applied to all men known to have been prisoners of war at some stage in 1943, but of whom, none make it to the main Chindit POW Camps, either at Maymyo or Rangoon Jail.

Rank: Private

Service No: 4206334

Date of Death: 01/06/1943

Age:21

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery, Face 5.

CWGC link: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2130644/AINDOW,%20HENRY%20WILLIAM

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

Henry Aindow just like George Adey (see entry above), was also part of the Column 7 dispersal group led by Rex Walker. This former Royal Welch Fusilier had joined Chindit training in late September 1942 along with a small draft of other men from this unit. Not much is known about Henry's movements after the 10th of April and there seems to be conflicting evidence from two separate witness statements concerning his fate in 1943. For a more detailed account in regard to Lieutenant Walker's dispersal group, please click on the link below: Dispersal Group 4

From the evidence given in the witness statements it seems fairly certain that Pte. Aindow had fallen in to Japanese hands in April 1943, but that he had not survived for long as a POW and certainly did not make the journey down to Rangoon Jail with the other Chindit prisoners. The official information given for his last known whereabouts states: "Pte. Aindow was last seen marching westward towards the Irrawaddy, but failed to make the planned rendezvous with other dispersal groups."

The first witness statement was given by Pte. Thomas Worthington, a Liverpudlian by birth and another member of Column 7. Thomas was also captured by the Japanese during Operation Longcloth and had survived his two years as a POW in Rangoon. On his return home Thomas had taken the trouble to write down everything he could remember about his lost and fallen comrades from the expedition in 1943. His five page letter included this short sentence concerning Henry Aindow:

"Pte. Aindow, formerly with the R.W.F. was from Crosby near Liverpool. I last saw him in a hospital in either Calore or Kalawa, he was suffering from dysentery. The fittest of his party were sent on to Rangoon via Maymyo. Major Ramsay-R.A.M.C. our Medical Officer was in charge."

NB. Thomas Worthington obviously could not be sure which was the correct spelling for the transit camp at Kalawa where many captured Chindits were held for a short time before being sent on to the main concentration camp at Maymyo. Once collected together at Maymyo, the 200 or so Chindit men were put through a vicious and brutal POW acclimatisation regime, before finally being sent down to Rangoon Jail. Major Raymond Ramsay was the senior Medical Officer on Operation Longcloth in 1943.

The inference from Thomas Worthington's statement is that Henry Aindow never left the camp at Kalawa. The second witness statement also comes in the form of a letter written back in England after the war was over. Corporal John Kennedy survived his time in Rangoon Jail and returned home to his family, in his letter dated 17th November 1945 he recalls what another Chindit POW had told him about the fate of Henry Aindow.

Lance Corporal Ernest Burgess was another member of Column 7 in 1943 and was, like Kennedy and Aindow, a member of Dispersal Group 4 that year. Ernest Burgess had told Kennedy what had happened to Pte. Aindow shortly before his own sad death in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail in March 1944. The disturbing information given by Burgess, stated that Henry had been killed by Burmese villagers who had been helping the Japanese at that time. He added that this murder took place on the 6th May 1943. It is difficult to speculate what actually happened to Pte. Aindow, but it seems likely that he may have become so ill or exhausted that the Japanese ordered the treacherous Burmese to dispose of him on their behalf.

NB. You may notice that the CWGC information gives Henry Aindow's date of death as 01/06/1943. This date I have found during my research, seems to be universally applied to all men known to have been prisoners of war at some stage in 1943, but of whom, none make it to the main Chindit POW Camps, either at Maymyo or Rangoon Jail.

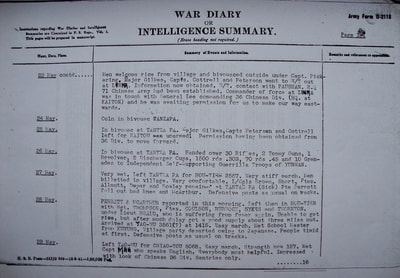

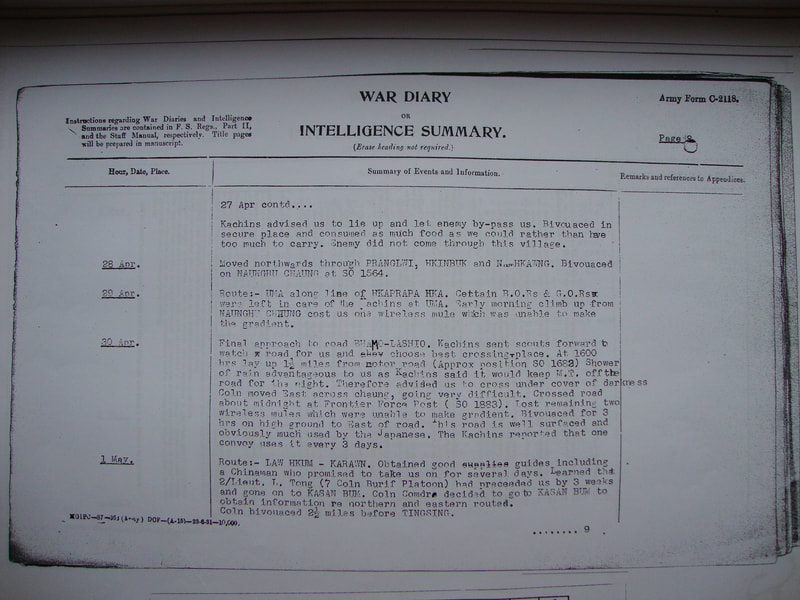

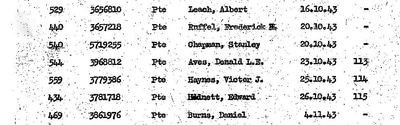

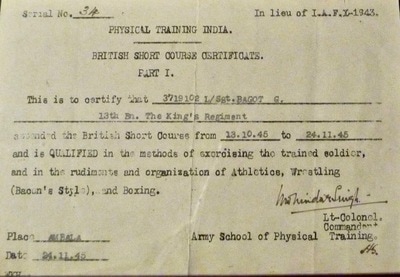

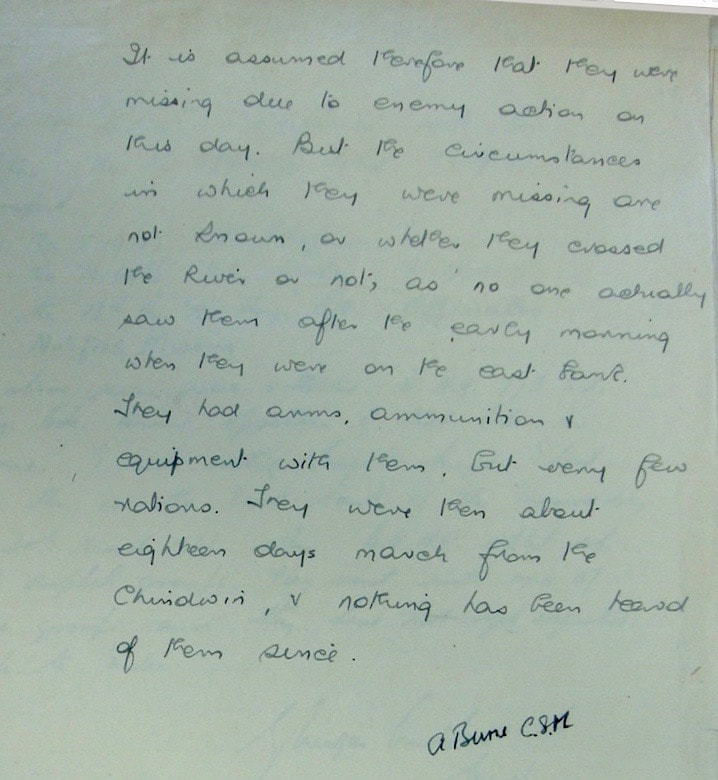

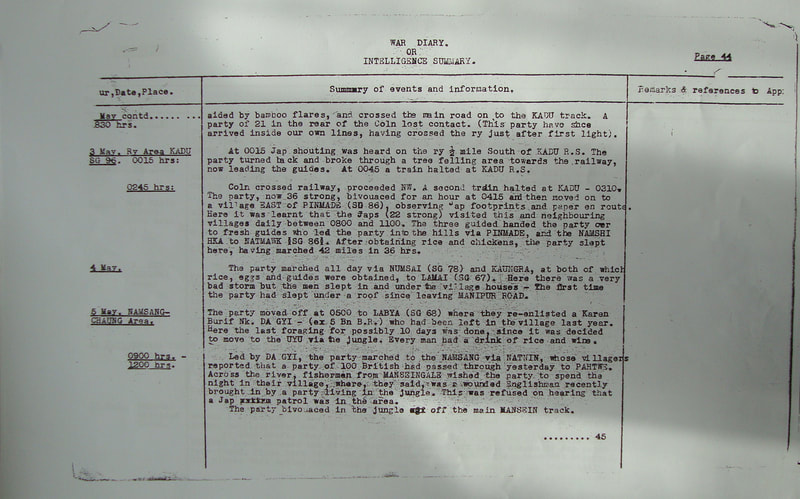

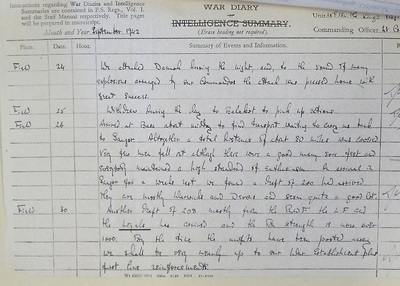

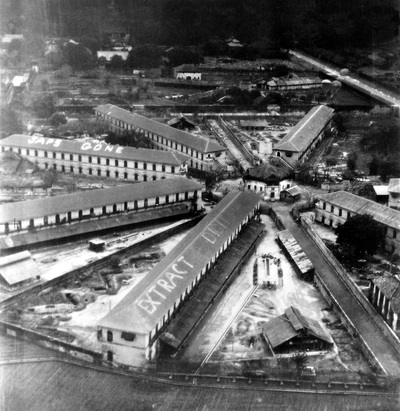

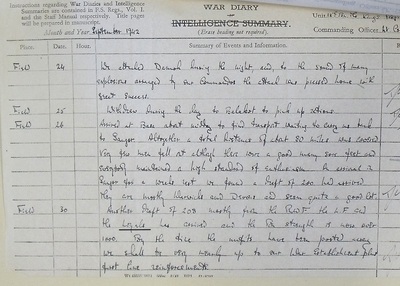

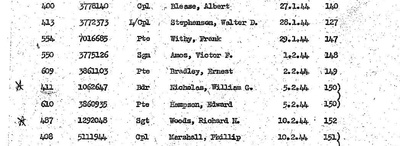

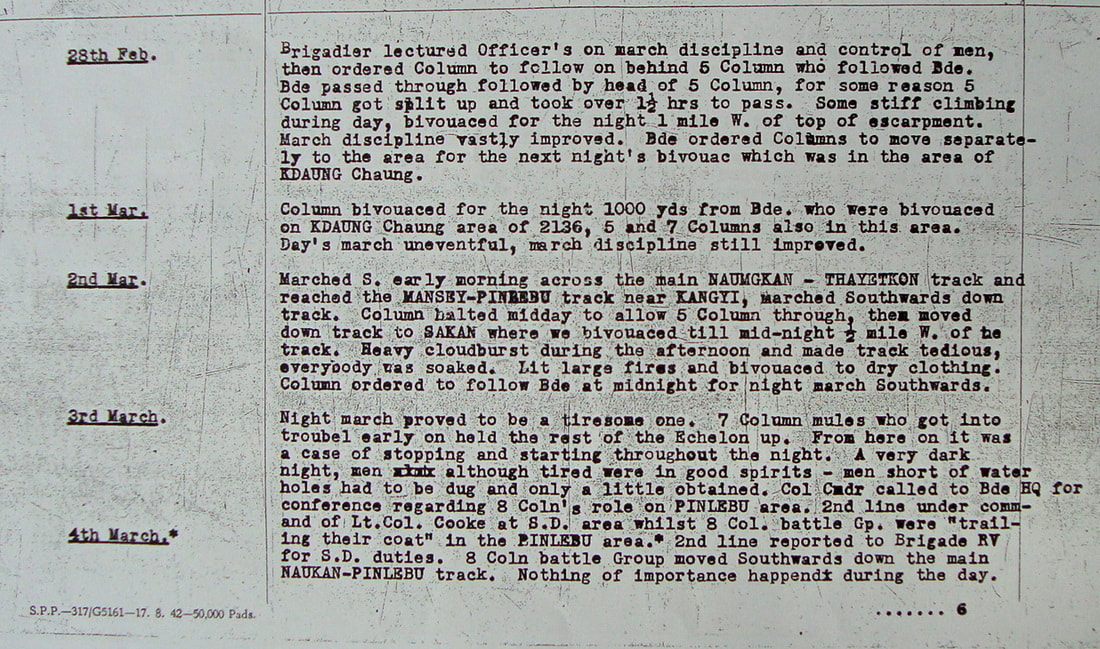

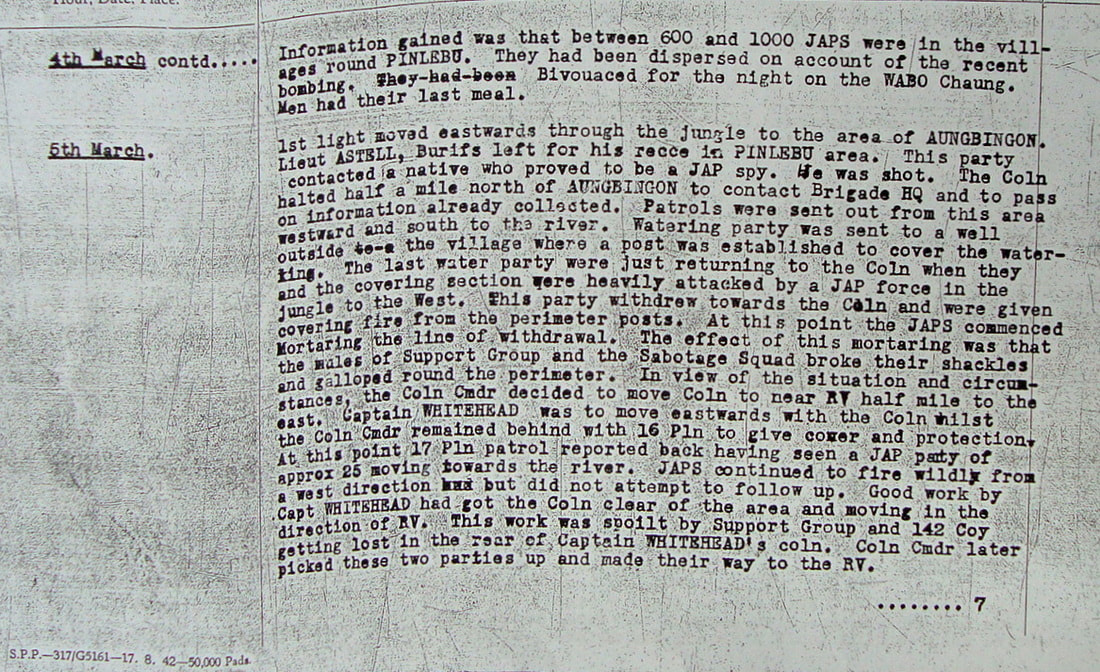

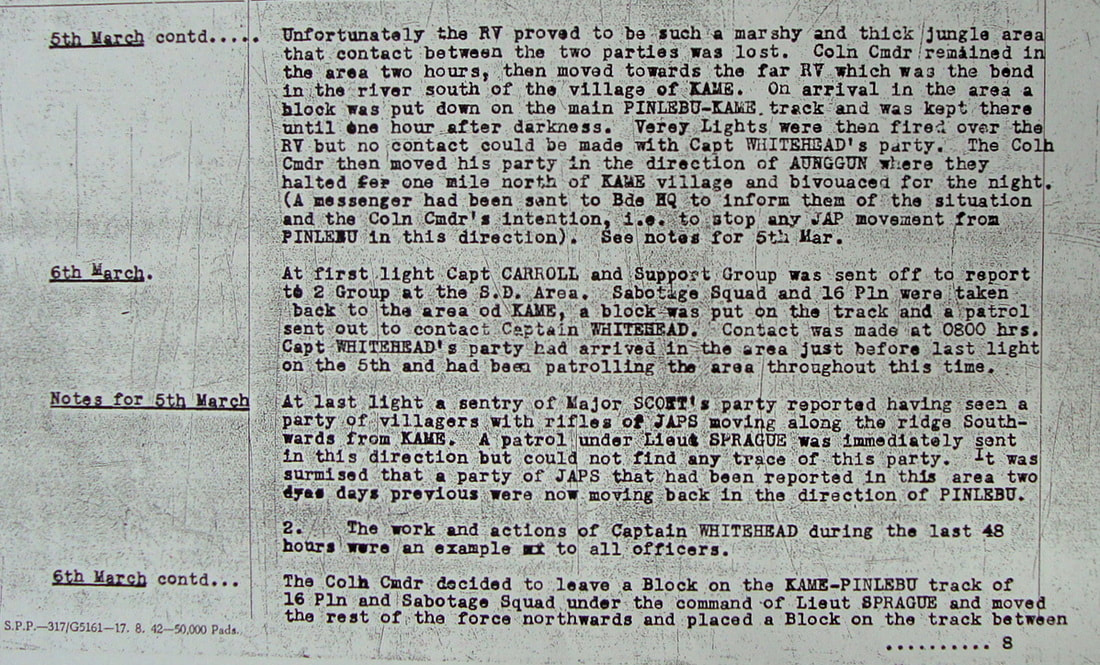

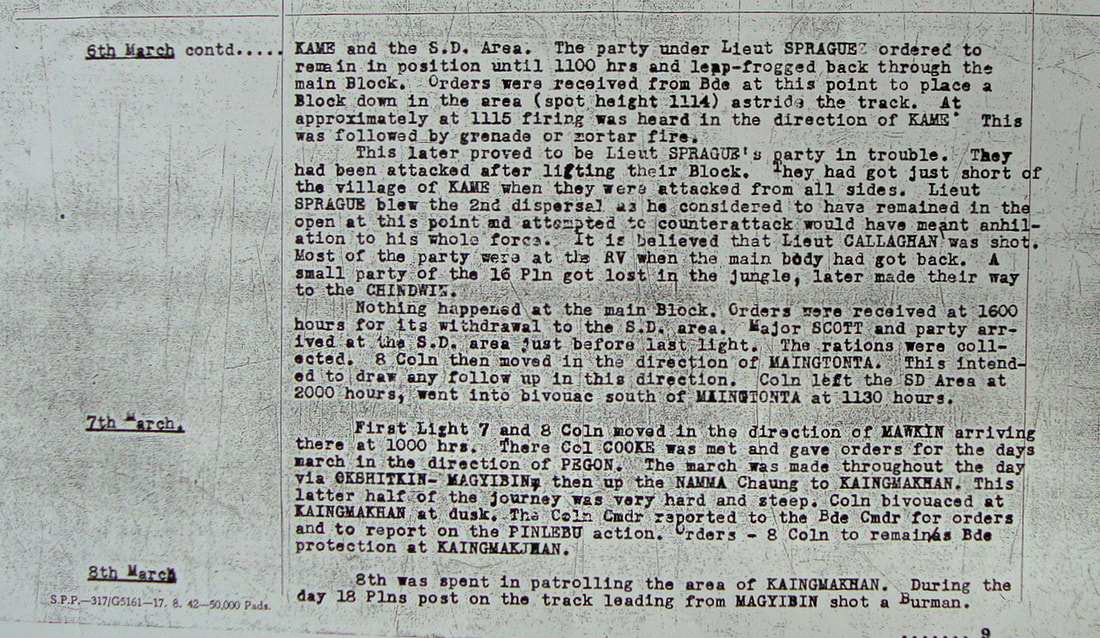

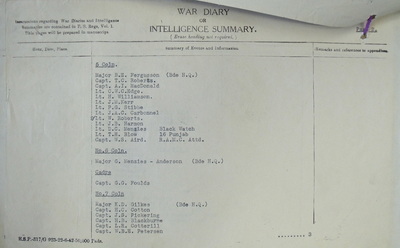

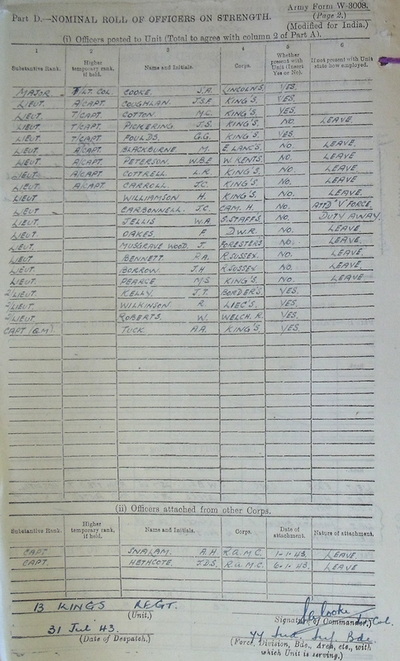

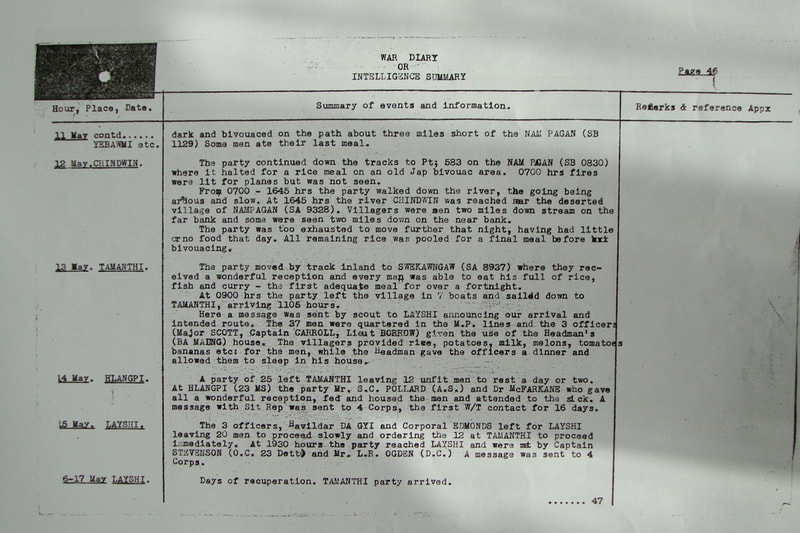

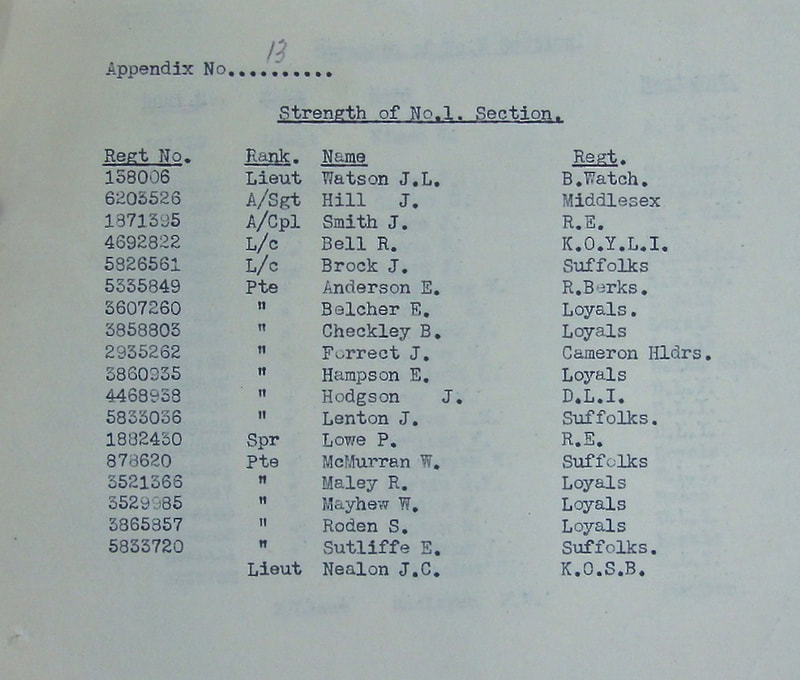

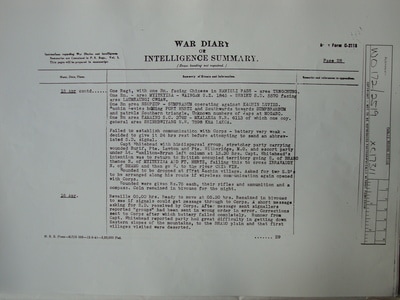

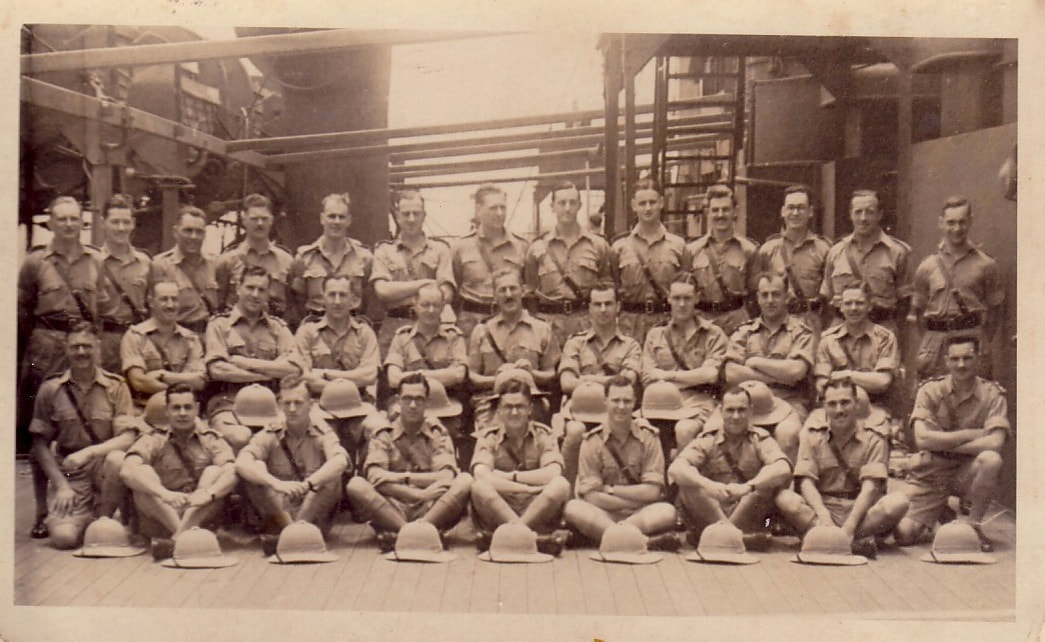

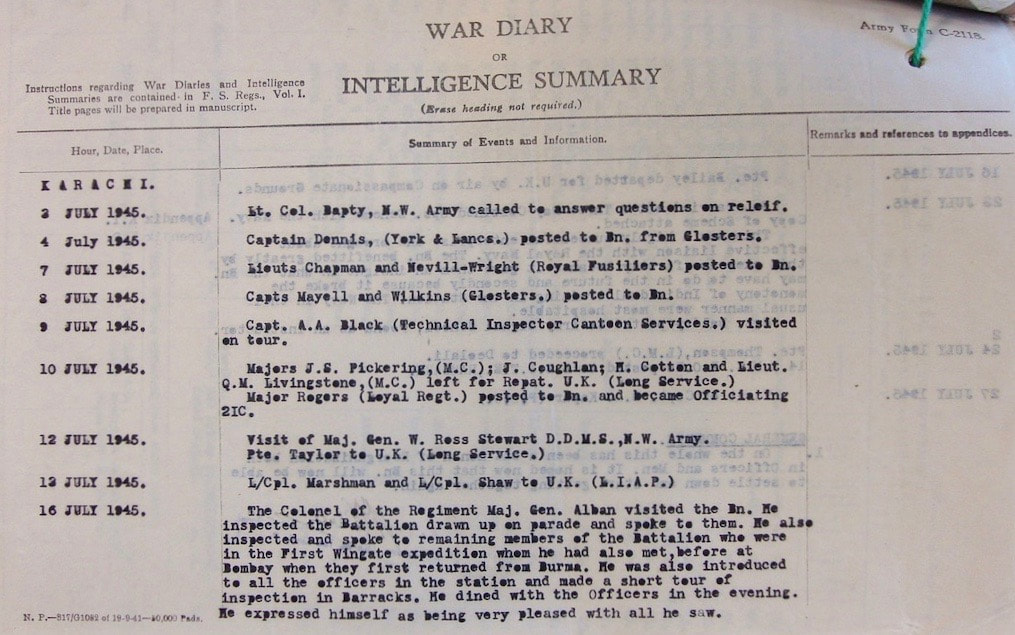

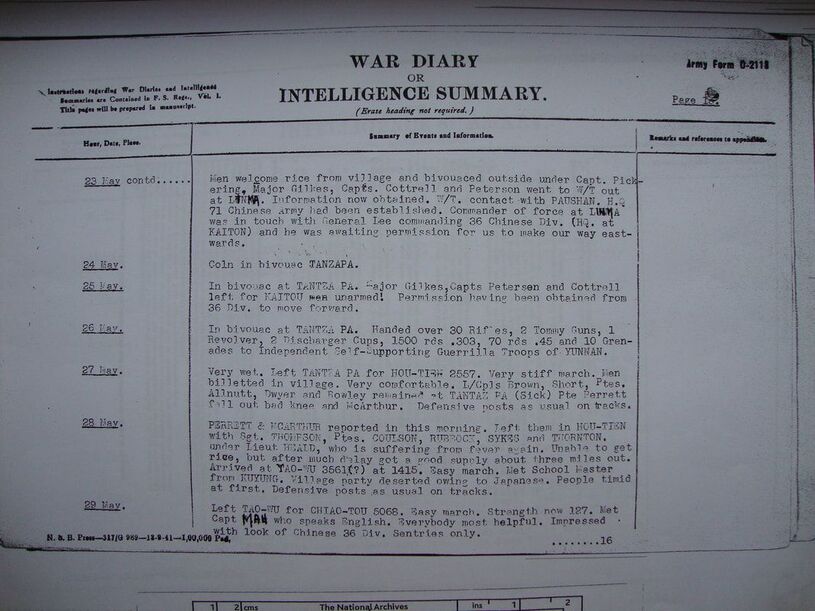

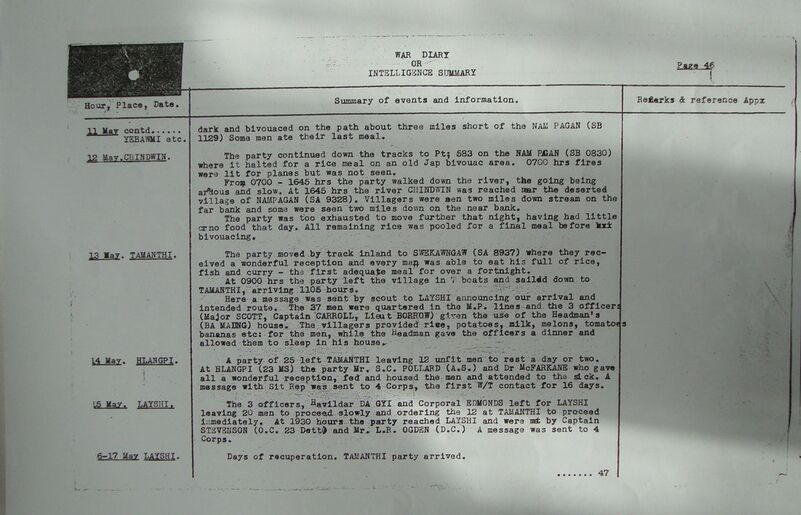

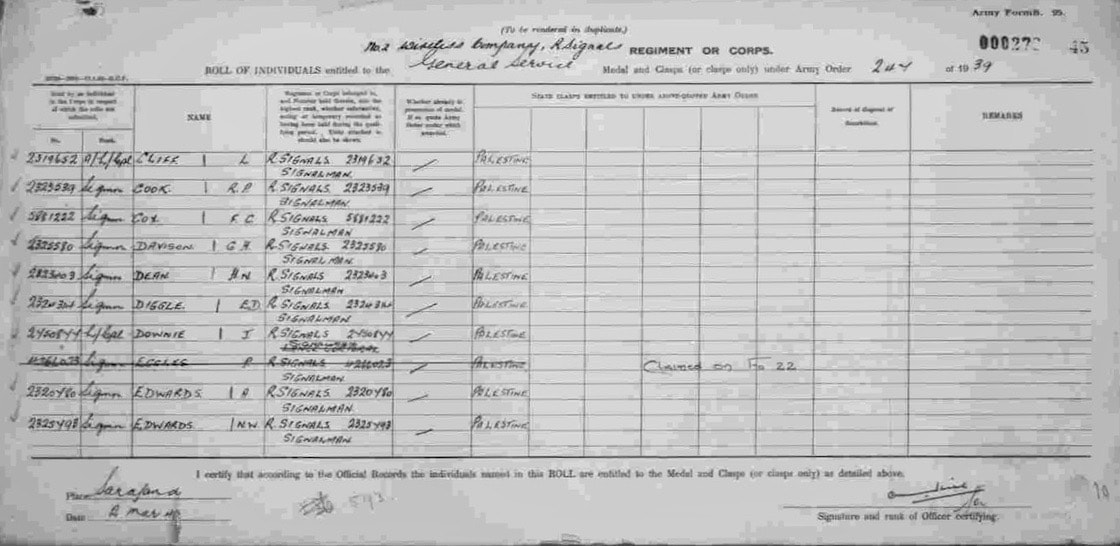

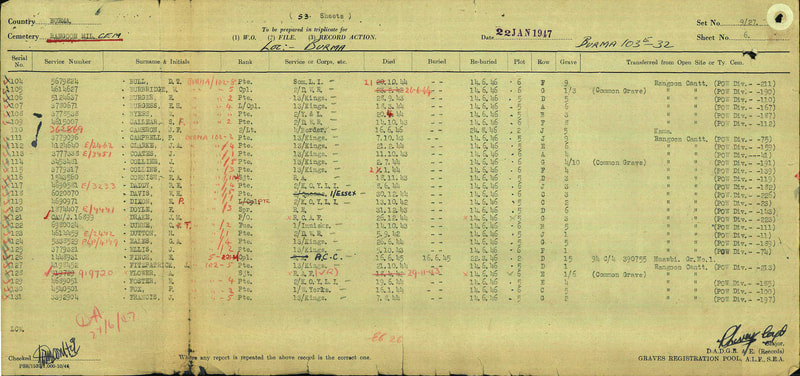

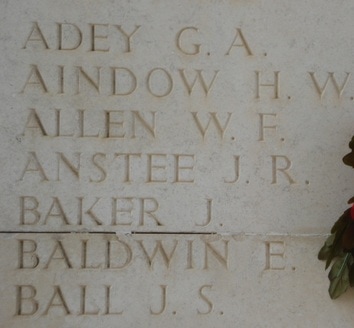

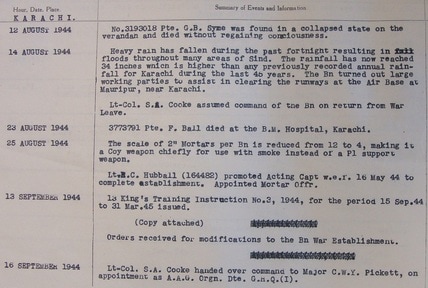

13th King's War diary November 1944.

13th King's War diary November 1944.

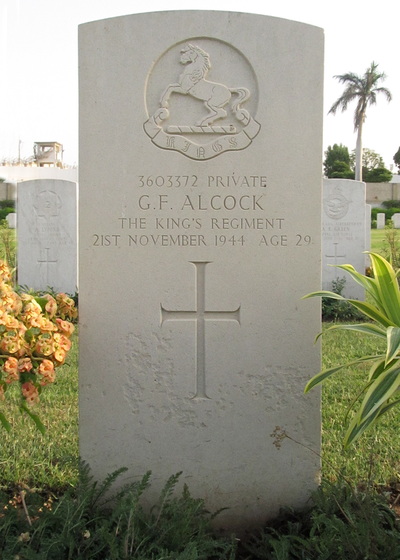

ALCOCK, GEORGE FRANCIS

Rank: Private

Service No: 3603372

Date of Death: 21/11/1944

Age:29

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Karachi War Cemetery, Grave Reference1.B.12.

CWGC link: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2178005/ALCOCK,%20GEORGE%20FRANCIS

Chindit Column: Not known.

Other details:

George Alcock is another of the soldiers of whom I can find no confirmation or details in relation to service on Operation Longcloth. It may well be that he was a reinforcement for the beleagued battalion and only joined them after they returned to India in mid-1943. I do know that Pte. Alcock served with the 13th King's whilst they were stationed at Napier Barracks in Karachi.

In November 1944, Pte. Alcock contracted malaria and was admitted to the British General Hospital at Karachi. Sadly, his was a very virulent strain of the disease which had developed in to the cerebral condition and affected his brain. George Alcock died in hospital on 21st November and was buried at Karachi Military Cemetery.

Diseases such as malaria affected almost all of the returning Chindits in 1943, indeed, most men who served in Burma suffered for many years with the after effects of the various diseases they had picked up, with symptoms often baffling their hometown GP's.

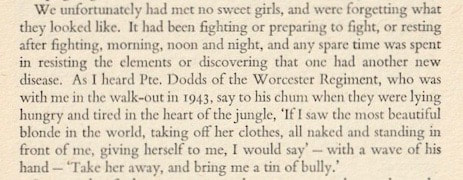

Returning to the 13th King's and their time at the Napier Barracks in Karachi, there follows a short extract from the memoirs of another Kingsman, Pte. Frank Holland who served with Column 8 on Operation Longcloth. Frank remembers suffering with malaria around the same period of time as George Alcock.

"After a month we set off for Karachi. During the journey I developed malaria and by the time we arrived I was an ambulance case and went to hospital. Your first dose of malaria really puts you down, temperatures you’ve never heard of, deliriums and the quinine playing havoc with everything. The hospital in Karachi was a nice place and they did some important operations in the main building. Malaria, jaundice, typhoid and dysentery cases were kept in detached huts, but not isolated from one another.

If you could walk with malaria you had to fetch your bedding and mattress from the store and make the bed. There was one bright thing to it, malaria cases were given one bottle of beer each day for free. Back in barracks you were allowed one bottle per month on a coupon which you paid for. Napier Barracks were old regular Army barracks. They were two storey brick buildings with verandahs upstairs and down to draw the air in, because we had no fans or punkhas. Life was pretty good there, as we so called convalescents had been built up to full fitness."

Some time later Frank Holland recalls:

"Malaria was still pestering me, in and out of hospital quite regular. We buried a few of our lads as a result of it. We agreed to have photos taken of their graves and sent back to relatives, small comfort, but we always got letters of thanks back."

NB: By matching up the date of death and with location of burial noted as Karachi War Cemetery, I believe the following men from the 13th King's all died from malaria as described in Frank Holland's memoir:

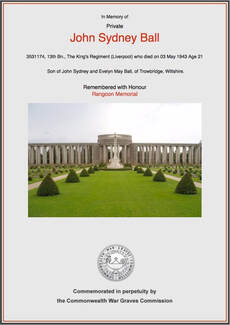

Francis Ball

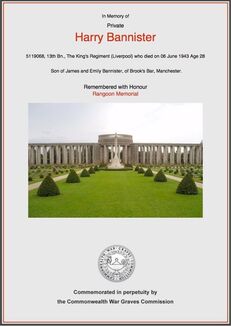

Thomas Charles Grigg

William George Jones

George Thomas Puckett

John Francis Wright

Update 12/09/2014. From information found in the India Office records for burials, I now know that George did indeed die from the effects cerebral malaria, he was buried at Karachi and his funeral service was conducted by Chaplain G. Huntley who served at the General Hospital in the city.

Update 24/03/2015. Thanks to the kind permission of the TWGPP, seen below is a photograph of George Alcock's gravestone at Karachi War Cemetery. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: 3603372

Date of Death: 21/11/1944

Age:29

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Karachi War Cemetery, Grave Reference1.B.12.

CWGC link: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2178005/ALCOCK,%20GEORGE%20FRANCIS

Chindit Column: Not known.

Other details:

George Alcock is another of the soldiers of whom I can find no confirmation or details in relation to service on Operation Longcloth. It may well be that he was a reinforcement for the beleagued battalion and only joined them after they returned to India in mid-1943. I do know that Pte. Alcock served with the 13th King's whilst they were stationed at Napier Barracks in Karachi.

In November 1944, Pte. Alcock contracted malaria and was admitted to the British General Hospital at Karachi. Sadly, his was a very virulent strain of the disease which had developed in to the cerebral condition and affected his brain. George Alcock died in hospital on 21st November and was buried at Karachi Military Cemetery.

Diseases such as malaria affected almost all of the returning Chindits in 1943, indeed, most men who served in Burma suffered for many years with the after effects of the various diseases they had picked up, with symptoms often baffling their hometown GP's.

Returning to the 13th King's and their time at the Napier Barracks in Karachi, there follows a short extract from the memoirs of another Kingsman, Pte. Frank Holland who served with Column 8 on Operation Longcloth. Frank remembers suffering with malaria around the same period of time as George Alcock.

"After a month we set off for Karachi. During the journey I developed malaria and by the time we arrived I was an ambulance case and went to hospital. Your first dose of malaria really puts you down, temperatures you’ve never heard of, deliriums and the quinine playing havoc with everything. The hospital in Karachi was a nice place and they did some important operations in the main building. Malaria, jaundice, typhoid and dysentery cases were kept in detached huts, but not isolated from one another.

If you could walk with malaria you had to fetch your bedding and mattress from the store and make the bed. There was one bright thing to it, malaria cases were given one bottle of beer each day for free. Back in barracks you were allowed one bottle per month on a coupon which you paid for. Napier Barracks were old regular Army barracks. They were two storey brick buildings with verandahs upstairs and down to draw the air in, because we had no fans or punkhas. Life was pretty good there, as we so called convalescents had been built up to full fitness."

Some time later Frank Holland recalls:

"Malaria was still pestering me, in and out of hospital quite regular. We buried a few of our lads as a result of it. We agreed to have photos taken of their graves and sent back to relatives, small comfort, but we always got letters of thanks back."

NB: By matching up the date of death and with location of burial noted as Karachi War Cemetery, I believe the following men from the 13th King's all died from malaria as described in Frank Holland's memoir:

Francis Ball

Thomas Charles Grigg

William George Jones

George Thomas Puckett

John Francis Wright

Update 12/09/2014. From information found in the India Office records for burials, I now know that George did indeed die from the effects cerebral malaria, he was buried at Karachi and his funeral service was conducted by Chaplain G. Huntley who served at the General Hospital in the city.

Update 24/03/2015. Thanks to the kind permission of the TWGPP, seen below is a photograph of George Alcock's gravestone at Karachi War Cemetery. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

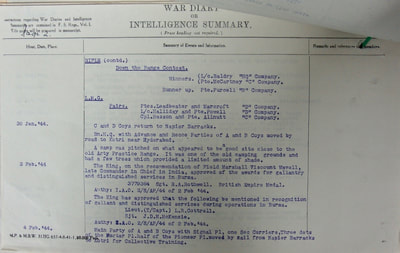

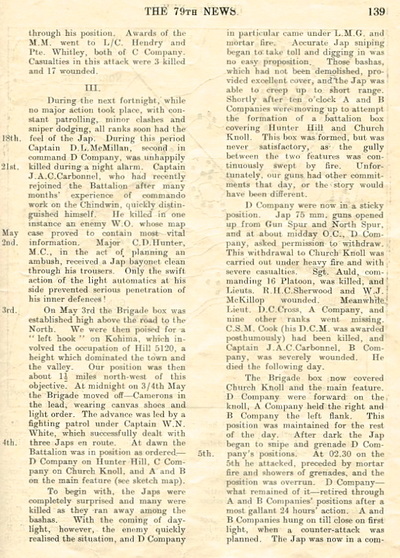

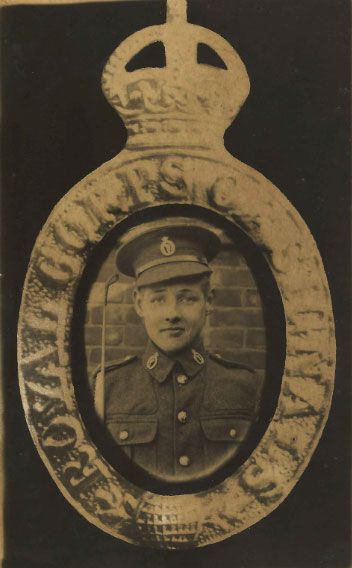

King's Regiment Cap Badge.

King's Regiment Cap Badge.

ALLNUTT, STANLEY

Rank: Private

Service No: not known

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

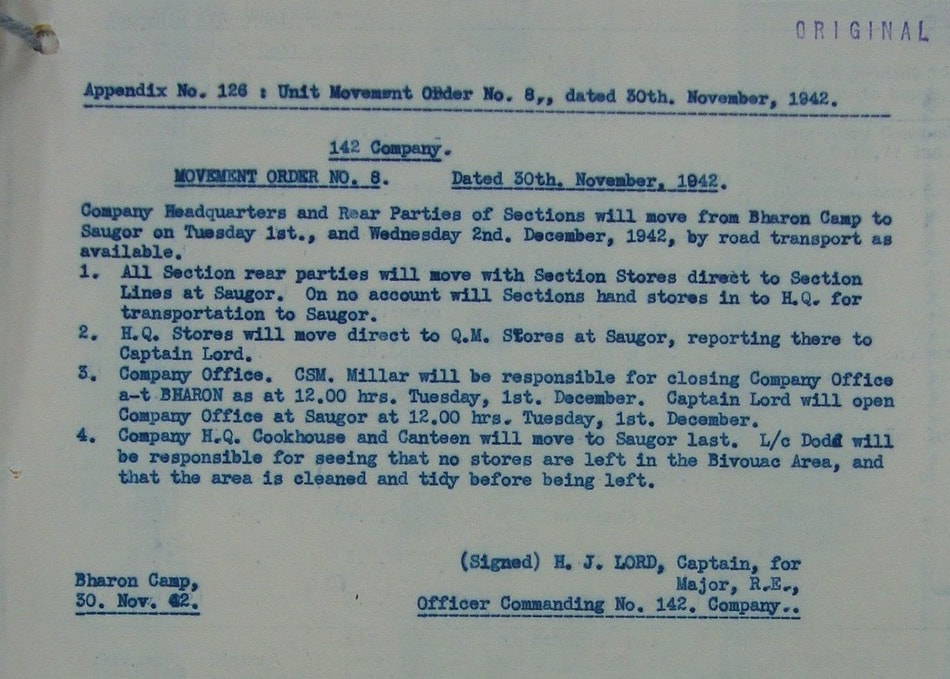

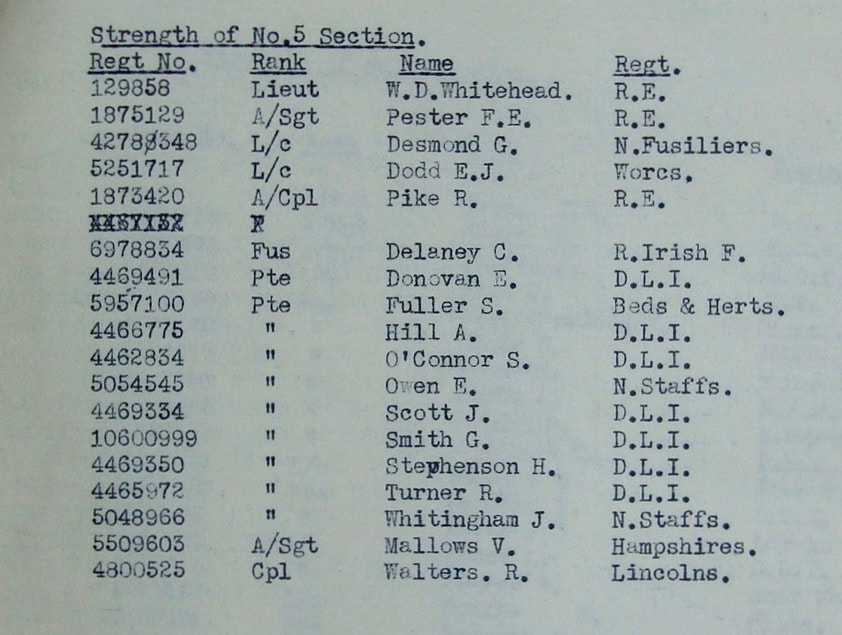

Pte. Stanley Allnutt travelled to India with the original 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment aboard the troopship Oronsay in December 1941. According to several sources, Stanley served with C' Company within the battalion and was allocated to Chindit column No. 7 during training in the Central Provinces of India. He must have settled quickly into the training regime, as by December 1942, he was selected to take part in a pre-operational reconnaissance mission across the Burmese border, in order to ascertain the numbers of Japanese present in the Chindwin area and the disposition of the local Burmese towards the British.

One of the main reasons for his selection on this mission was Stanley's ability to speak some Burmese phrases, which he had learned during his time training with the Burma Rifles section of 7 Column. His recce party led by Captain Herring, alongside Sgt. Tony Aubrey and Sgt. Tommy Vann, spent some time behind enemy lines in early January 1943, before returning to the main Chindit Brigade to report on their findings from across the Chindwin River. To read more about this mission and the other men involved, please click on the following link:

Pre-Operational Reconnaissance

Pte. Allnutt's best friend from his time with the 13th King's was Pte. Charles Aves. Both men had served with the battalion since the second half of 1940 and both were part of Rifle Platoon No. 13 within 7 Column on Operation Longcloth. Charles Aves remembered Stan Allnutt as 77th Brigade finally made their way to the Chindwin River in February 1943:

First we left Saugor by train to Comilla, then on to Dimapur. After this we marched at night to Kohima through the most beautiful scenery I have ever seen. We then camped at Imphal and awaited our final orders before marching down to the Chindwin River. My best pal, Stan Allnutt was one of the men sent on pre-operational reconnaissance into Burma in January. Stan had taken the time to learn some useful Burmese phrases and this was probably why he was chosen for this short trip over the Chindwin. After he came back he taught me many of these words and phrases. No one was afraid when we first went into Burma, it was all an adventure and we were confident we could deal with the jungle at least.

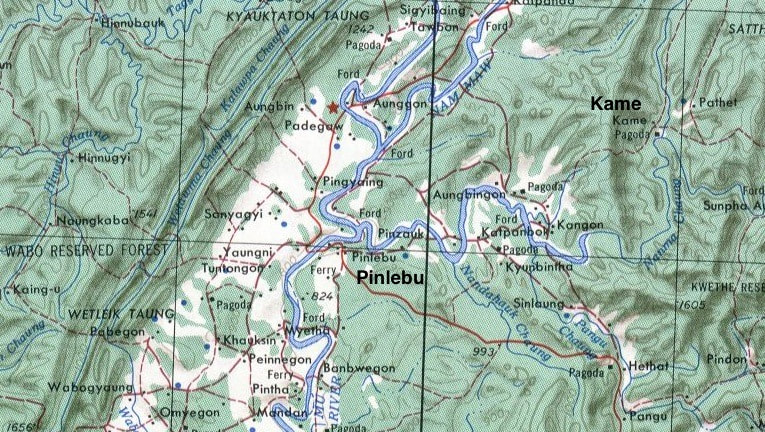

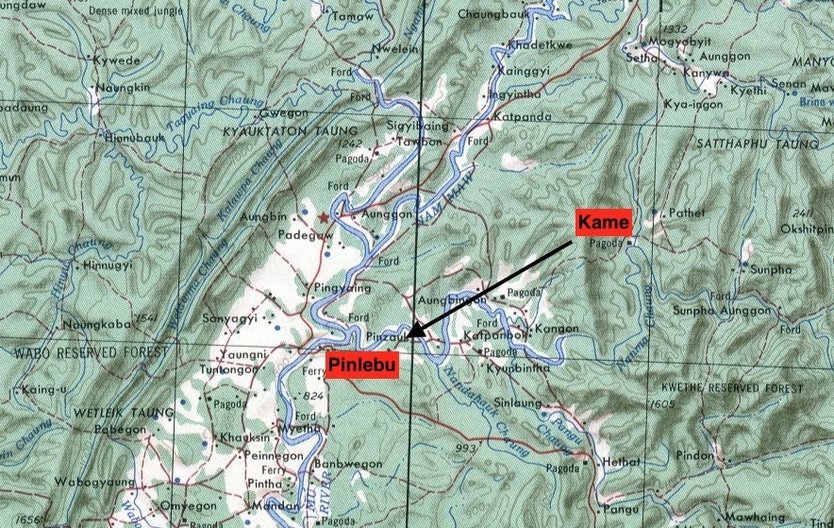

After a week or so Wingate made plans to attack a Japanese garrison at a place called Pinlebu, but this was called off. A while later, I remember Major Gilkes was chastised by Wingate for setting camp at the foot of a small hill instead of on top of it; Wingate explained that we would be vulnerable to enemy mortar fire if we camped in the lower ground. Not much more happened during the next few weeks. When I look back on those days now, I realise I was very fortunate to be one of the lucky men who avoided direct contact with the Japanese during the outward journey across Burma.

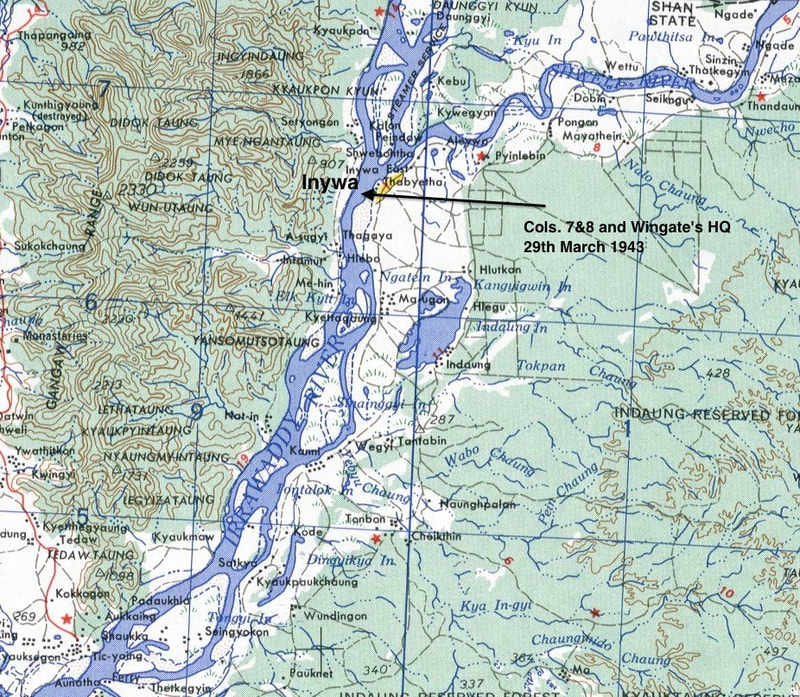

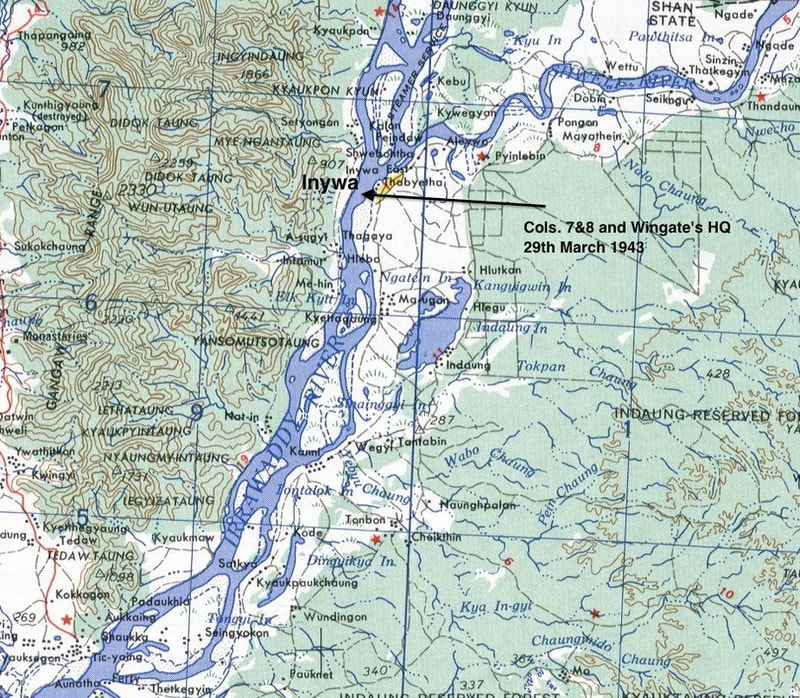

We finally arrived at the Irrawaddy and my own personal view was, if we crossed over now, we might as well be in Japan proper. But cross we did, just north of a town called Inywa. By this time fatigue had set in with some of our men, many were beginning to fall ill, including my friend Stan Allnutt. Fortunately, after a few days on the east side of the river, Brigadier Wingate decided it was time to return to India.

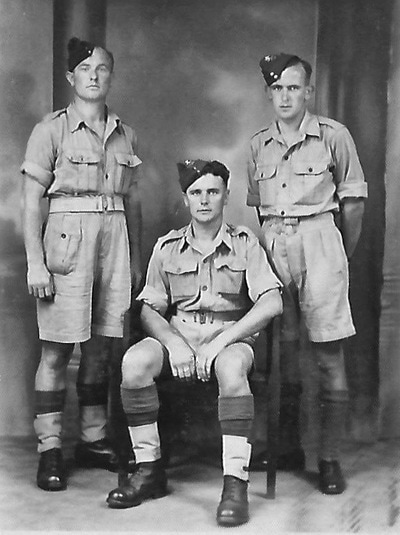

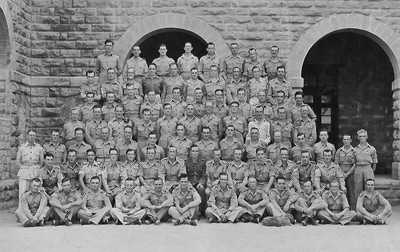

Seen in the gallery below are some of the men mentioned in the first section of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: not known

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

Pte. Stanley Allnutt travelled to India with the original 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment aboard the troopship Oronsay in December 1941. According to several sources, Stanley served with C' Company within the battalion and was allocated to Chindit column No. 7 during training in the Central Provinces of India. He must have settled quickly into the training regime, as by December 1942, he was selected to take part in a pre-operational reconnaissance mission across the Burmese border, in order to ascertain the numbers of Japanese present in the Chindwin area and the disposition of the local Burmese towards the British.

One of the main reasons for his selection on this mission was Stanley's ability to speak some Burmese phrases, which he had learned during his time training with the Burma Rifles section of 7 Column. His recce party led by Captain Herring, alongside Sgt. Tony Aubrey and Sgt. Tommy Vann, spent some time behind enemy lines in early January 1943, before returning to the main Chindit Brigade to report on their findings from across the Chindwin River. To read more about this mission and the other men involved, please click on the following link:

Pre-Operational Reconnaissance

Pte. Allnutt's best friend from his time with the 13th King's was Pte. Charles Aves. Both men had served with the battalion since the second half of 1940 and both were part of Rifle Platoon No. 13 within 7 Column on Operation Longcloth. Charles Aves remembered Stan Allnutt as 77th Brigade finally made their way to the Chindwin River in February 1943:

First we left Saugor by train to Comilla, then on to Dimapur. After this we marched at night to Kohima through the most beautiful scenery I have ever seen. We then camped at Imphal and awaited our final orders before marching down to the Chindwin River. My best pal, Stan Allnutt was one of the men sent on pre-operational reconnaissance into Burma in January. Stan had taken the time to learn some useful Burmese phrases and this was probably why he was chosen for this short trip over the Chindwin. After he came back he taught me many of these words and phrases. No one was afraid when we first went into Burma, it was all an adventure and we were confident we could deal with the jungle at least.

After a week or so Wingate made plans to attack a Japanese garrison at a place called Pinlebu, but this was called off. A while later, I remember Major Gilkes was chastised by Wingate for setting camp at the foot of a small hill instead of on top of it; Wingate explained that we would be vulnerable to enemy mortar fire if we camped in the lower ground. Not much more happened during the next few weeks. When I look back on those days now, I realise I was very fortunate to be one of the lucky men who avoided direct contact with the Japanese during the outward journey across Burma.

We finally arrived at the Irrawaddy and my own personal view was, if we crossed over now, we might as well be in Japan proper. But cross we did, just north of a town called Inywa. By this time fatigue had set in with some of our men, many were beginning to fall ill, including my friend Stan Allnutt. Fortunately, after a few days on the east side of the river, Brigadier Wingate decided it was time to return to India.

Seen in the gallery below are some of the men mentioned in the first section of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

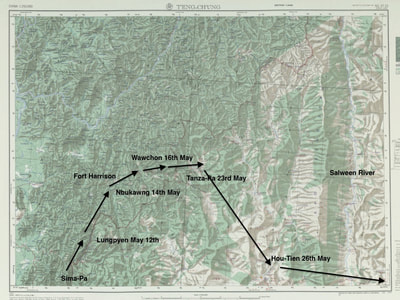

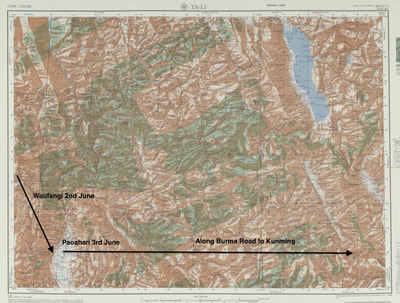

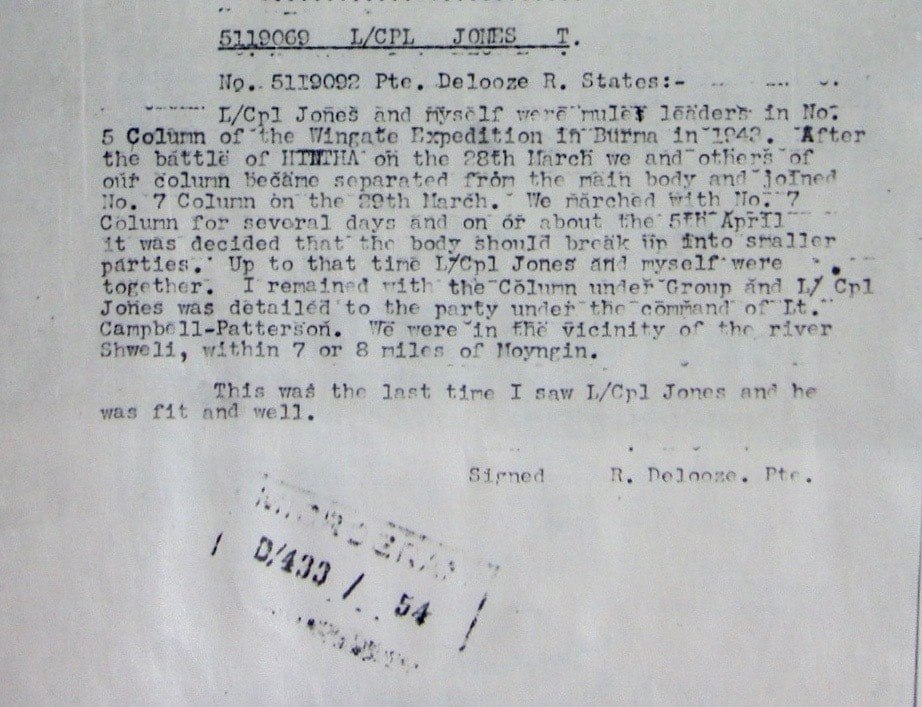

Later on after dispersal was called, Charles Aves and Stan Allnutt became separated and their journeys back to Allied held territory took different paths. Aves managed to re-cross the Irrawaddy on the 29th March 1943 and he with most of his group succeeded in reaching India a few weeks later. Pte. Allnutt, along with the majority of 7 Column exited Burma via the Yunnan Province of China in late May and were eventually flown back to India aboard USAAF Dakotas in early June.

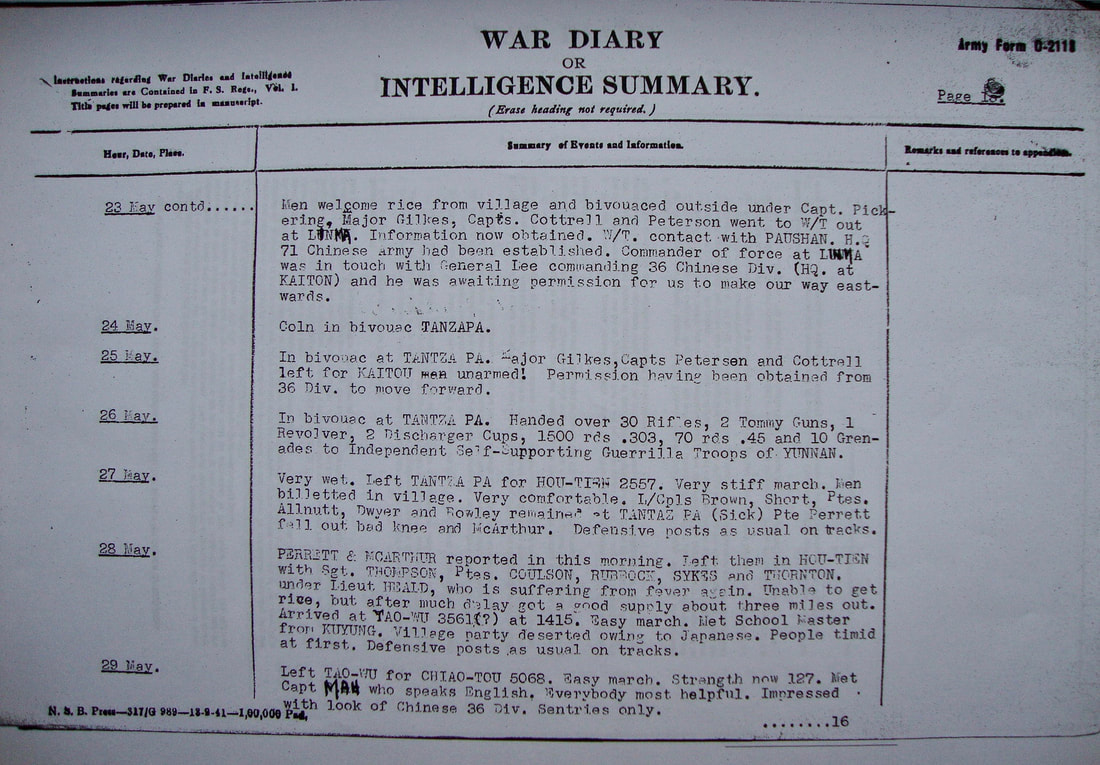

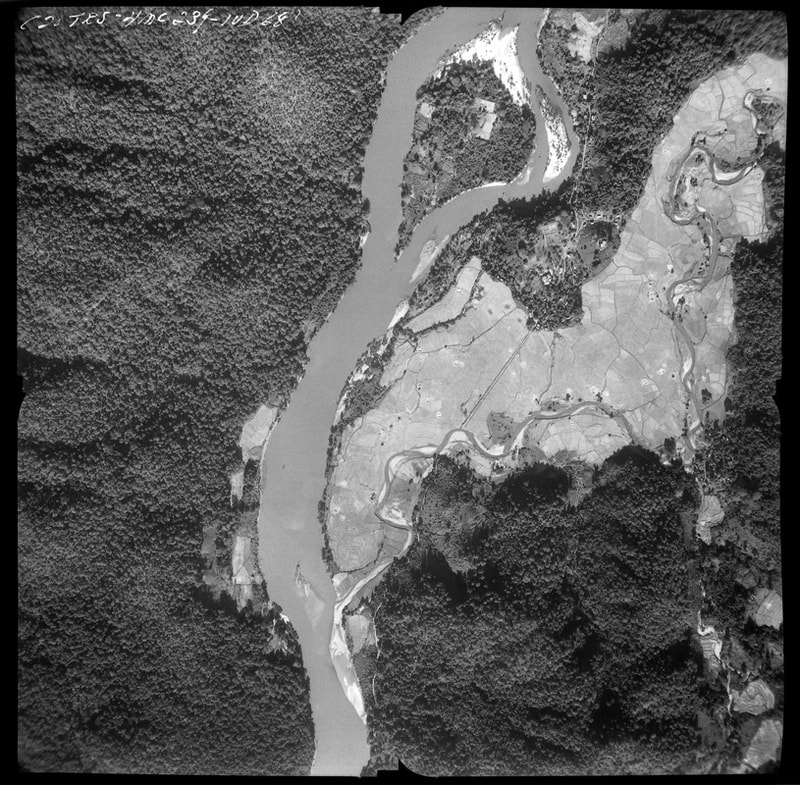

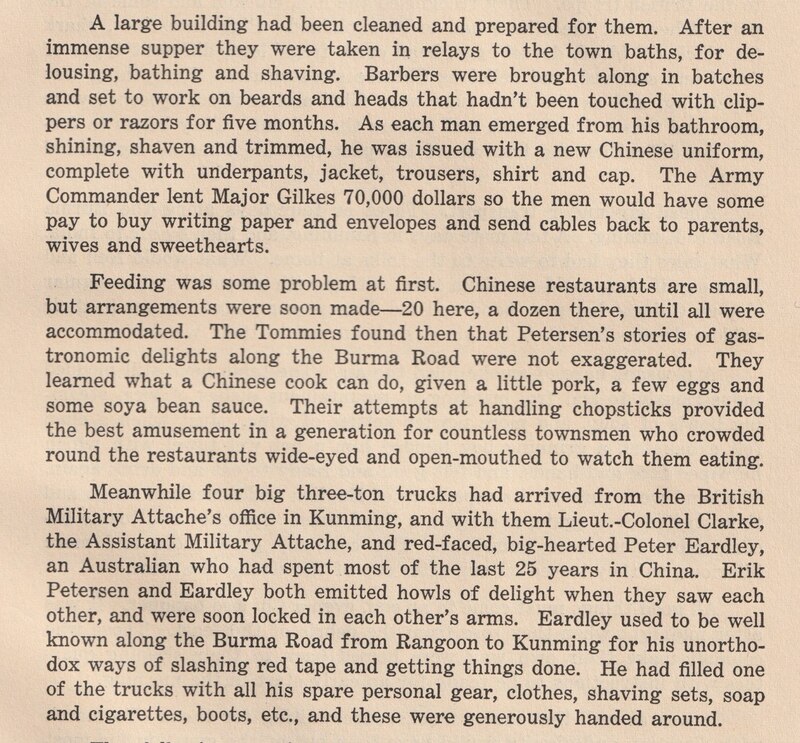

From the book, Wingate's Lost Brigade and based on the Column 7 War diary for the period:

By 23rd May, the column was reunited with its commander at Tantzu-Pa. A message had been sent to the nearest Chinese Divisional Headquarters and a couple of days later the reply came back that three officers should proceed to the headquarters and make arrangements for the movement of the rest of the column. Gilkes decided to take Petersen and Cottrell with him and before he left he gave Commander Wong, the guerrilla commander, a present of 30 rifles, two tommy guns, a revolver, 1,500 rounds of ammunition and ten grenades. The old veteran was very pleased as his men only had one rifle between every six men. As his men were now under Chinese protection, Gilkes considered it only reasonable to help their new Allies in view of the food and assistance given to them. Before they departed the commander told them, 'We are glad to meet Allied Officers who neither have creases in their trousers, nor ask for beds on which to sleep.'

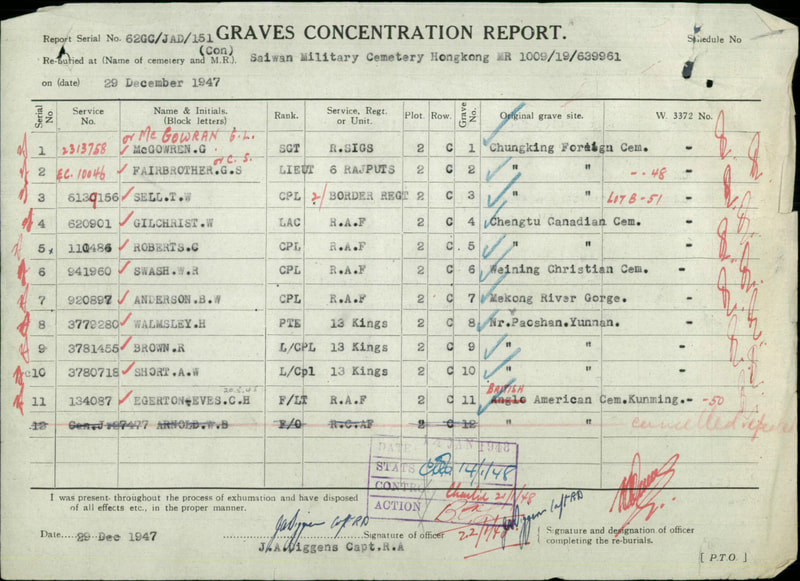

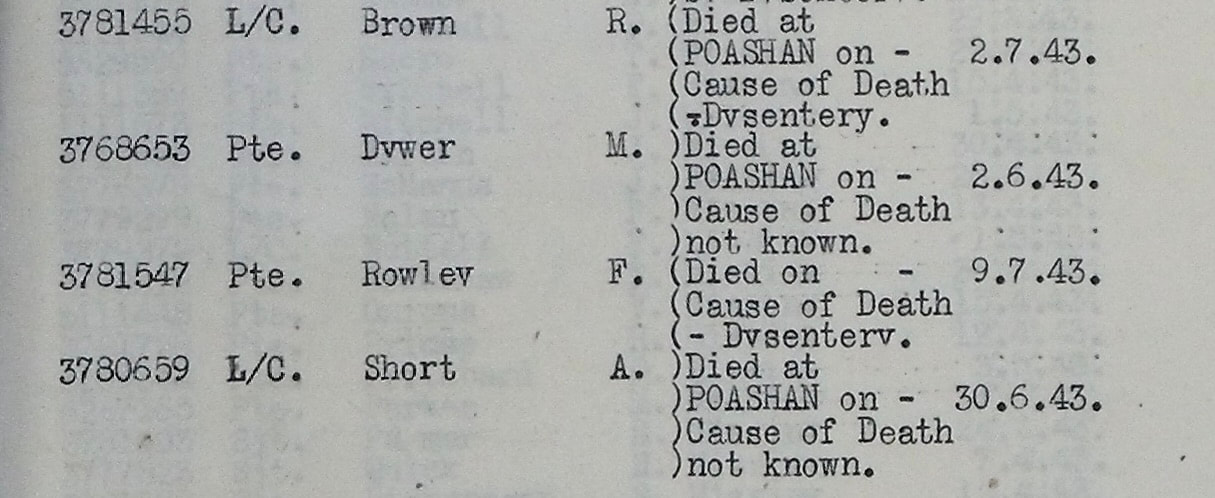

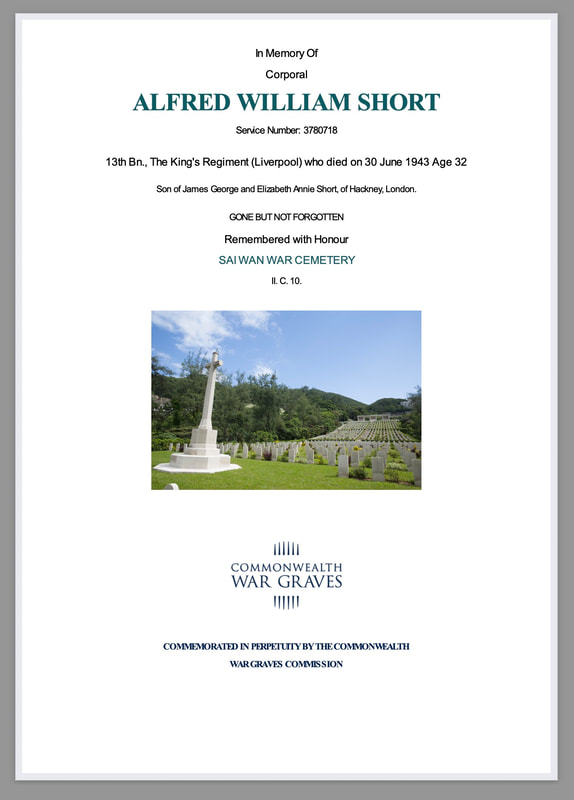

The journey was beginning to take its toll on some of the men and Lance Corporals Brown and Short, and Privates Allnutt, Dwyer, Rowley, Perrett and McArthur were left at Tantzu-Pa to recover. The next day Sergeant Thompson, Privates Coulson, Rubbock, Sykes and Thornton were left at Hou-Tien under Lieutenant Heald who himself was suffering recurrent bouts of fever.

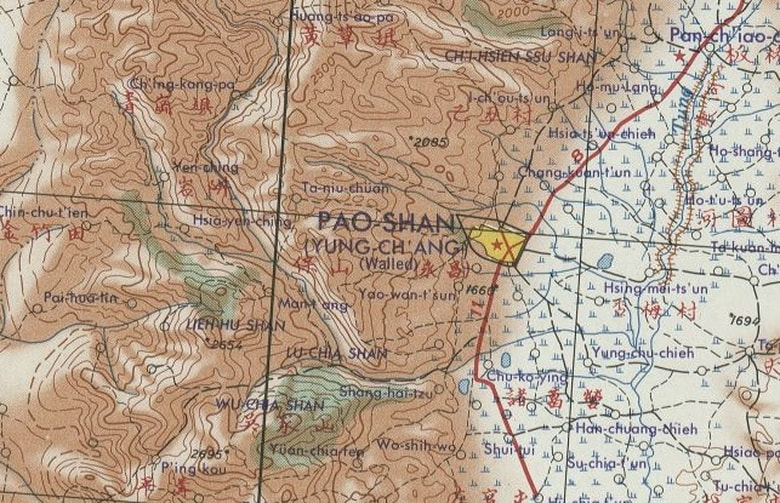

Later, on 3rd June, and after a strenuous march of 32 miles they finally reached Paoshan at 1945 hours. They were greeted with flags flying and a band playing military music, and were lodged in the best building in town. They were given baths, new clothes and haircuts, and the Chinese General even advanced Gilkes enough money to pay his men. Then followed a grand feast, given by the General commanding Seventy-First Chinese Army.

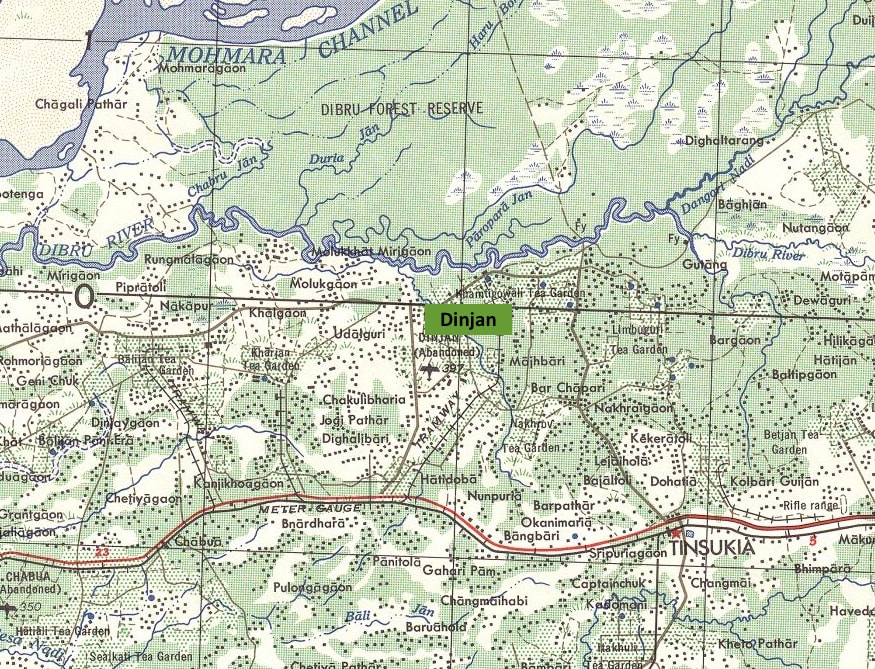

The men began the last leg of their journey home on 5th June when they boarded lorries for a drive along the Burma Road to Kunming and thence to Yunani where the American Air Force offered to fly them to Assam at once. On 9th June, Major Gilkes stepped off the train at Manipur Road, heading for Brigade Headquarters, while the rest of his men carried on to Shillong for a well-deserved rest and hospitalisation.

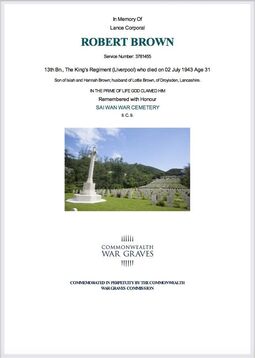

Sadly, not all of the men mentioned in the column War diary were able to make the journey back to India; with Frank Rowley, Robert Brown, Alfred Short and Maurice Dwyer all perishing in the Chinese hospital at Paoshan. Stan Allnutt eventually re-joined the 13th King's at their new base, located within the Napier Barracks in Karachi.

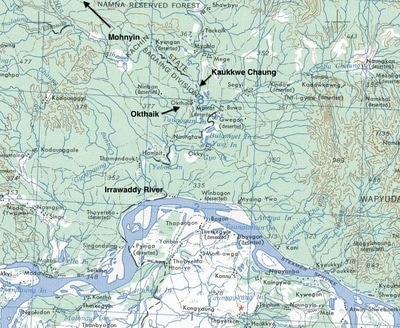

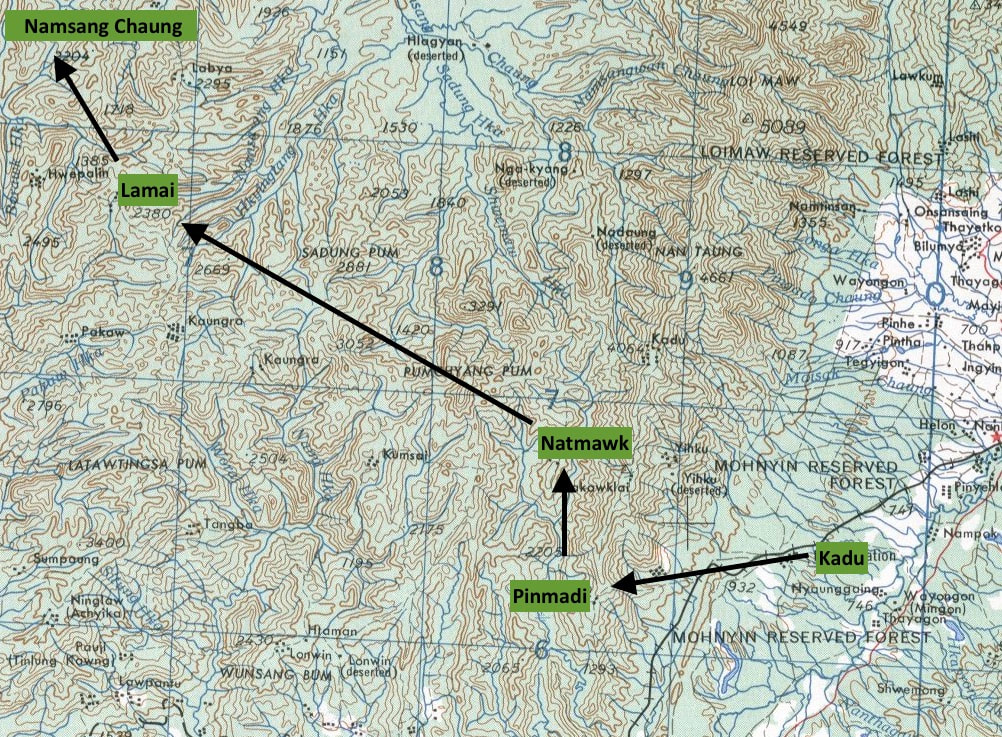

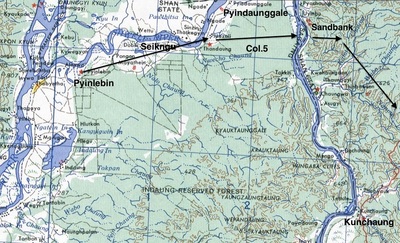

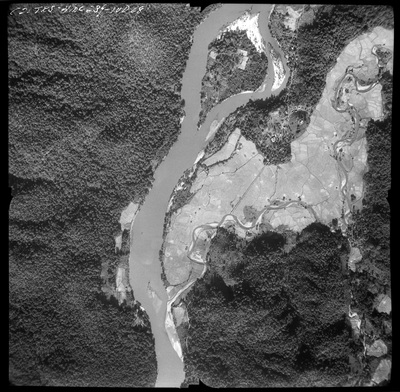

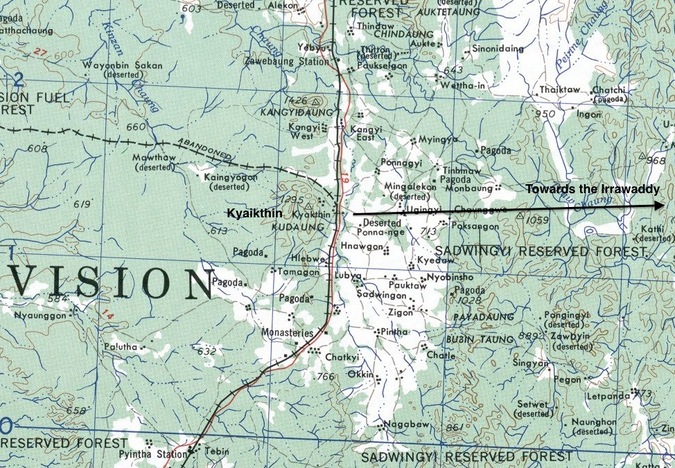

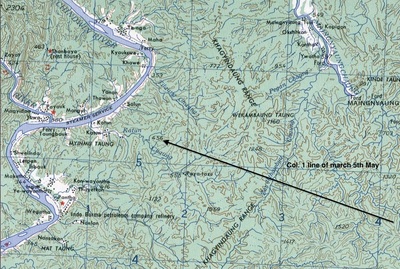

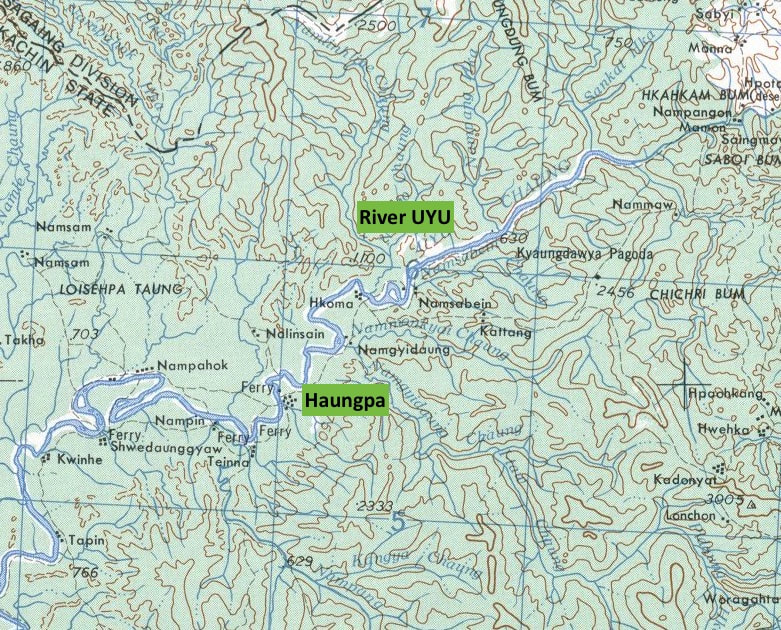

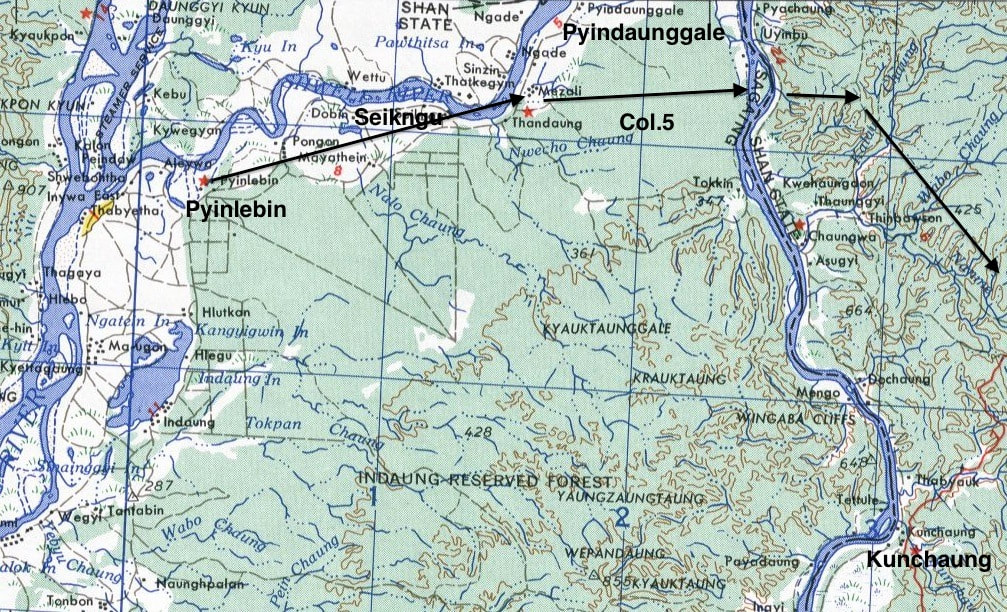

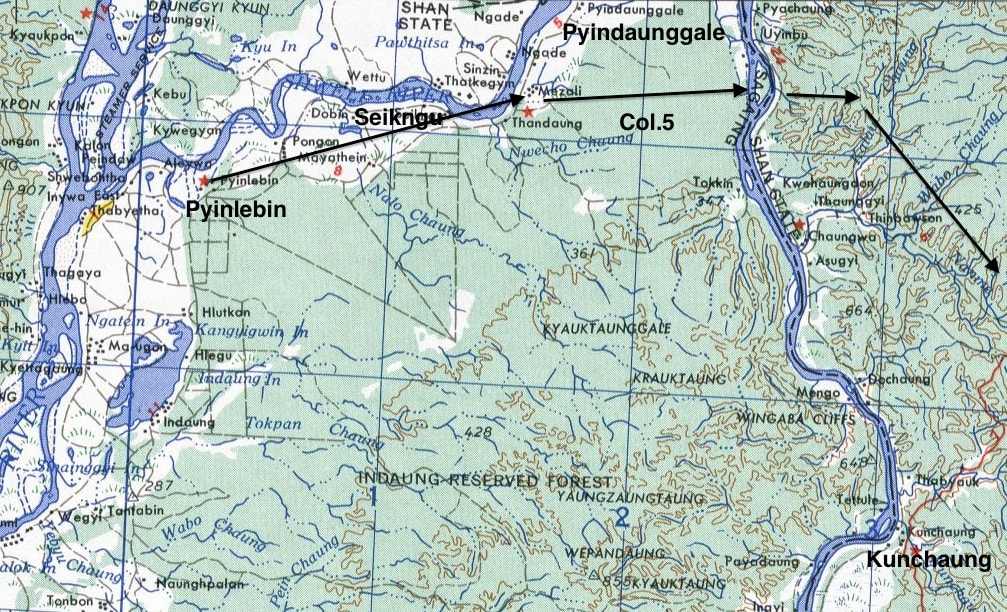

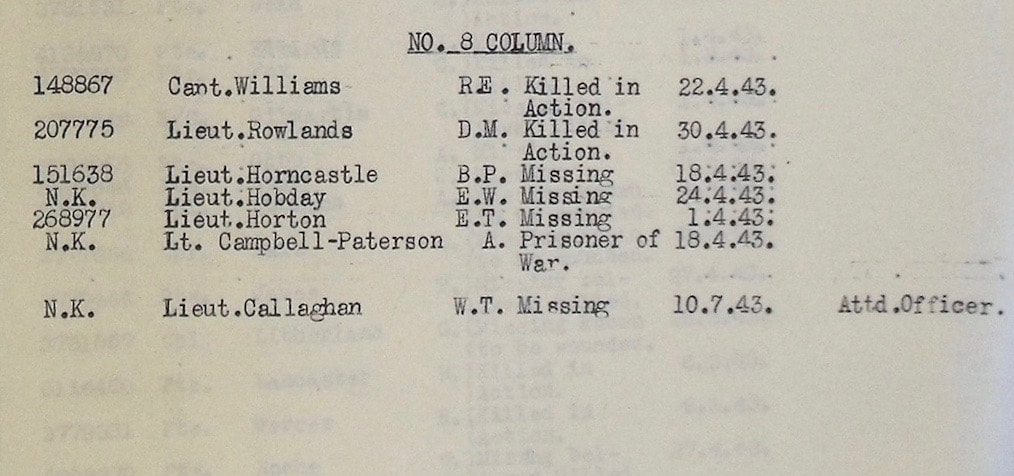

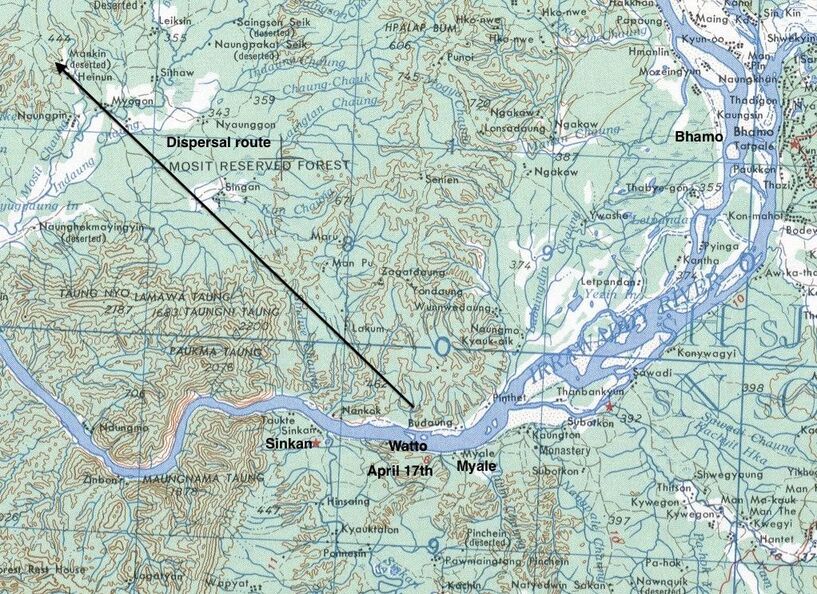

Seen below are two maps showing 7 Column's journey through northern Burma and into the Yunnan Province of China. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

From the book, Wingate's Lost Brigade and based on the Column 7 War diary for the period:

By 23rd May, the column was reunited with its commander at Tantzu-Pa. A message had been sent to the nearest Chinese Divisional Headquarters and a couple of days later the reply came back that three officers should proceed to the headquarters and make arrangements for the movement of the rest of the column. Gilkes decided to take Petersen and Cottrell with him and before he left he gave Commander Wong, the guerrilla commander, a present of 30 rifles, two tommy guns, a revolver, 1,500 rounds of ammunition and ten grenades. The old veteran was very pleased as his men only had one rifle between every six men. As his men were now under Chinese protection, Gilkes considered it only reasonable to help their new Allies in view of the food and assistance given to them. Before they departed the commander told them, 'We are glad to meet Allied Officers who neither have creases in their trousers, nor ask for beds on which to sleep.'

The journey was beginning to take its toll on some of the men and Lance Corporals Brown and Short, and Privates Allnutt, Dwyer, Rowley, Perrett and McArthur were left at Tantzu-Pa to recover. The next day Sergeant Thompson, Privates Coulson, Rubbock, Sykes and Thornton were left at Hou-Tien under Lieutenant Heald who himself was suffering recurrent bouts of fever.

Later, on 3rd June, and after a strenuous march of 32 miles they finally reached Paoshan at 1945 hours. They were greeted with flags flying and a band playing military music, and were lodged in the best building in town. They were given baths, new clothes and haircuts, and the Chinese General even advanced Gilkes enough money to pay his men. Then followed a grand feast, given by the General commanding Seventy-First Chinese Army.

The men began the last leg of their journey home on 5th June when they boarded lorries for a drive along the Burma Road to Kunming and thence to Yunani where the American Air Force offered to fly them to Assam at once. On 9th June, Major Gilkes stepped off the train at Manipur Road, heading for Brigade Headquarters, while the rest of his men carried on to Shillong for a well-deserved rest and hospitalisation.

Sadly, not all of the men mentioned in the column War diary were able to make the journey back to India; with Frank Rowley, Robert Brown, Alfred Short and Maurice Dwyer all perishing in the Chinese hospital at Paoshan. Stan Allnutt eventually re-joined the 13th King's at their new base, located within the Napier Barracks in Karachi.

Seen below are two maps showing 7 Column's journey through northern Burma and into the Yunnan Province of China. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Stan Allnutt remained with the battalion at Karachi for the rest of his war service. On the 30th January 1944, he was mentioned in the 13th King's War diary as having competed in the battalion's Down the Range shooting competition and had finished in third place alongside his partner, Corporal Basson in the Light Machine Gun category. Many of the original soldiers from the 13th King's, those who had made the voyage to India aboard the troopship Oronsay in late 1941, were repatriated to the United Kingdom in August 1945. It would seem likely that Stanley was amongst these men.

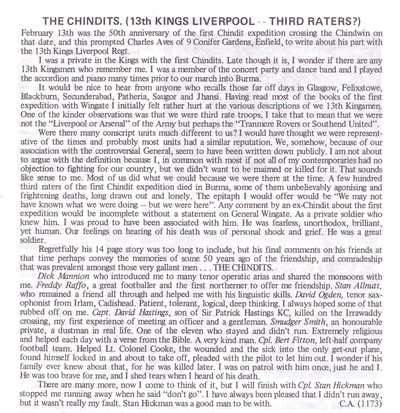

To conclude this story, I would like to transcribe the testimony of Pte. Charles Aves, as he remembered the friends and companions from his time with the 13th King's during the years of WW2. His words, taken from the pages of the Burma Star Association magazine, Dekho! in 1993, truly show the strong bond of comradeship built up between these men during those difficult and sometimes tragic times:

I would like to dedicate these memoirs; they are not complete, but I think there is sufficient there to state my own position. I would like to dedicate them to my friends from that time.

Dick Manion, who introduced me to many of the great tenor operatic arias and shared the monsoons with me. Freddy Raffo, a great footballer, and the first northerner to offer me friendship. Stan Allnutt, who remained a friend all through and helped me with his (Burmese) linguistic skills. David Ogden, tenor saxophonist from Irlam and Cadishead, patient, tolerant, logical and deep thinking, I always hoped some of that rubbed off on me. David Hastings, Captain, killed in the Irrawaddy crossing, my first experience in meeting an officer and a gentleman.

Smudger Smith, an honourable private, a dustman in real life. One of the eleven who stayed and didn't run. Extremely religious and helped us each day with a verse from the bible. A very kind man. Corporal Bert Fitton, left-half company football team, helped Lt.-Colonel Cooke and the sick and the wounded into the only get out plane. Found himself locked in and about to take off, pleaded with the pilot to let him out. I wonder if his family ever knew about that? I was on patrol with him once, just he and I. He was too brave for me and I had tears when I heard of his death.

There are many more now I come to think of it. But we will finish with Corporal Stan Hickman, who stopped me running away when he said don't go. I've always been pleased that I did not run away, but it really wasn't my fault. Stan Hickman was good man to be with.

To conclude this story, I would like to transcribe the testimony of Pte. Charles Aves, as he remembered the friends and companions from his time with the 13th King's during the years of WW2. His words, taken from the pages of the Burma Star Association magazine, Dekho! in 1993, truly show the strong bond of comradeship built up between these men during those difficult and sometimes tragic times:

I would like to dedicate these memoirs; they are not complete, but I think there is sufficient there to state my own position. I would like to dedicate them to my friends from that time.

Dick Manion, who introduced me to many of the great tenor operatic arias and shared the monsoons with me. Freddy Raffo, a great footballer, and the first northerner to offer me friendship. Stan Allnutt, who remained a friend all through and helped me with his (Burmese) linguistic skills. David Ogden, tenor saxophonist from Irlam and Cadishead, patient, tolerant, logical and deep thinking, I always hoped some of that rubbed off on me. David Hastings, Captain, killed in the Irrawaddy crossing, my first experience in meeting an officer and a gentleman.

Smudger Smith, an honourable private, a dustman in real life. One of the eleven who stayed and didn't run. Extremely religious and helped us each day with a verse from the bible. A very kind man. Corporal Bert Fitton, left-half company football team, helped Lt.-Colonel Cooke and the sick and the wounded into the only get out plane. Found himself locked in and about to take off, pleaded with the pilot to let him out. I wonder if his family ever knew about that? I was on patrol with him once, just he and I. He was too brave for me and I had tears when I heard of his death.

There are many more now I come to think of it. But we will finish with Corporal Stan Hickman, who stopped me running away when he said don't go. I've always been pleased that I did not run away, but it really wasn't my fault. Stan Hickman was good man to be with.

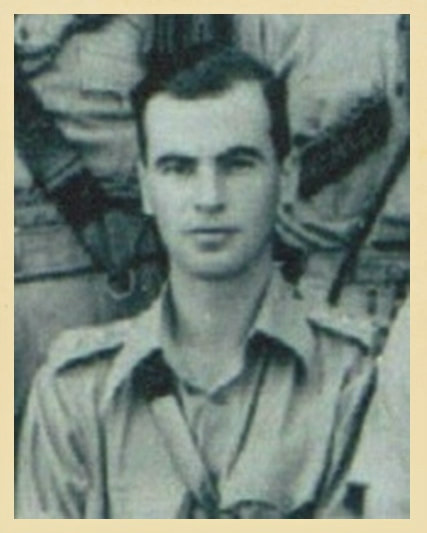

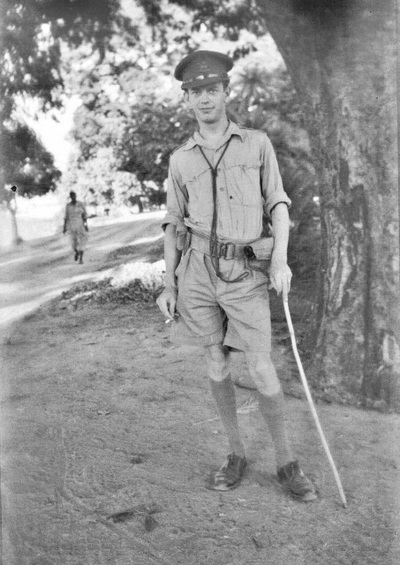

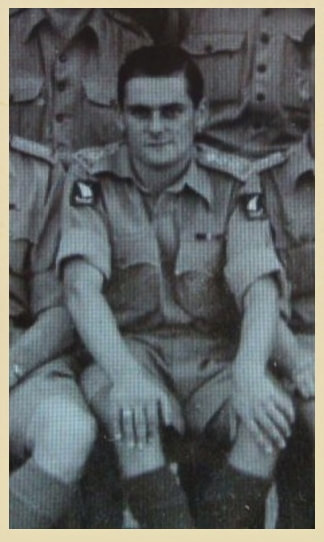

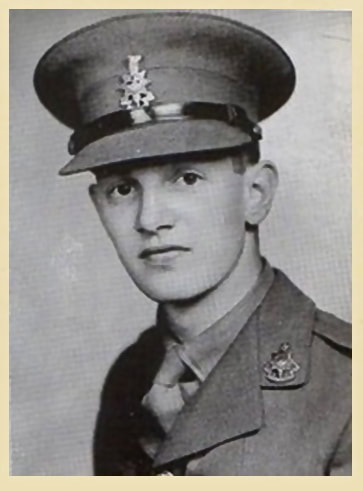

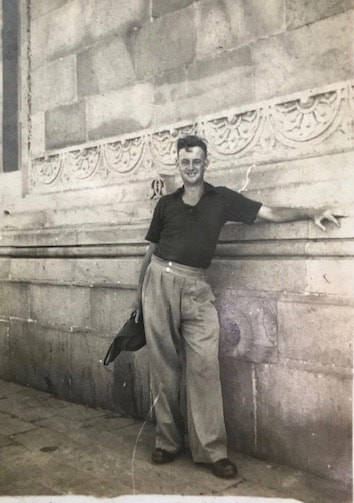

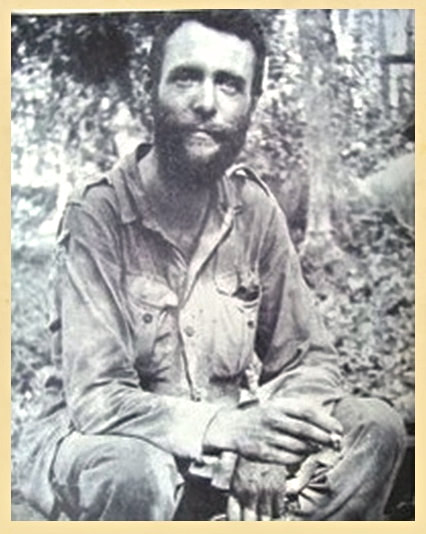

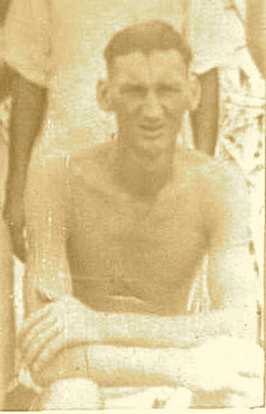

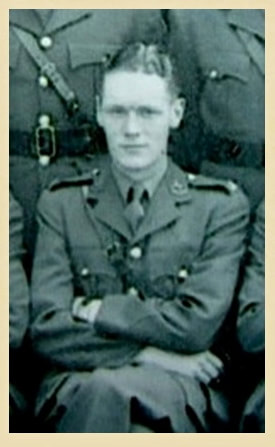

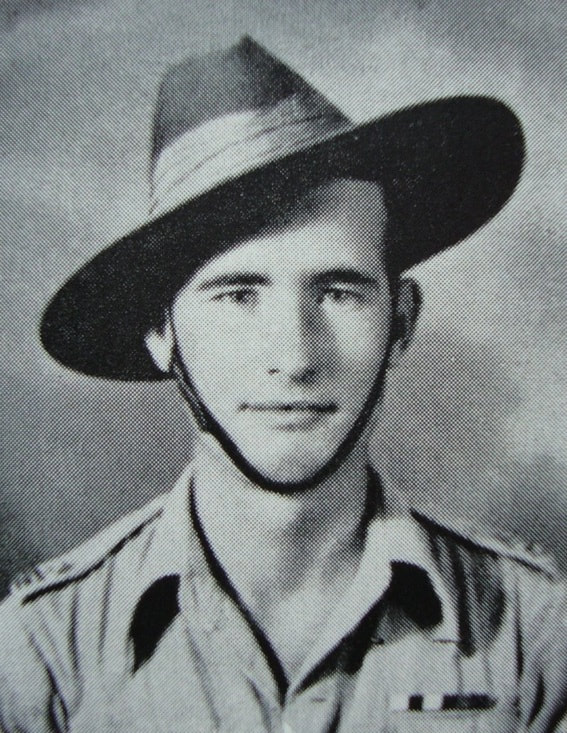

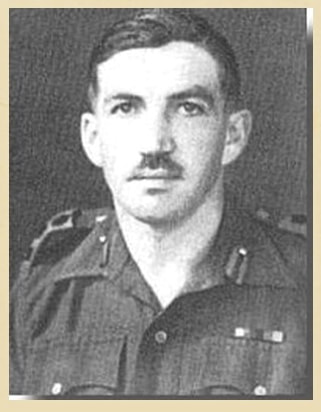

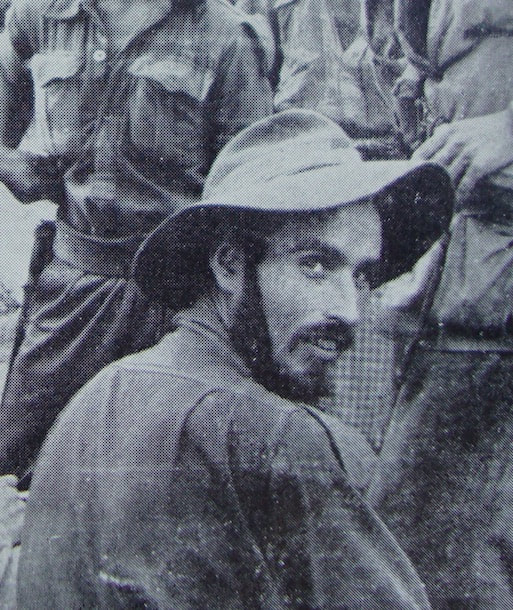

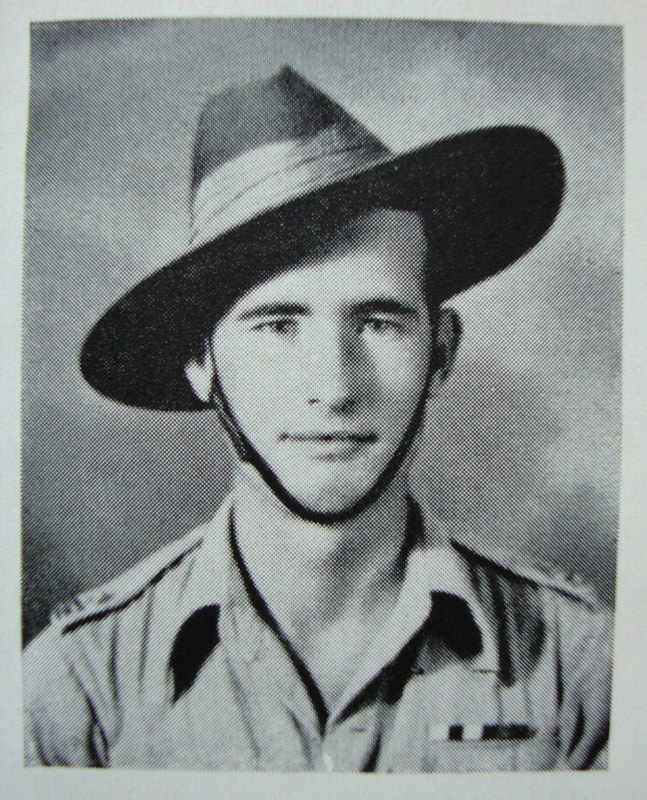

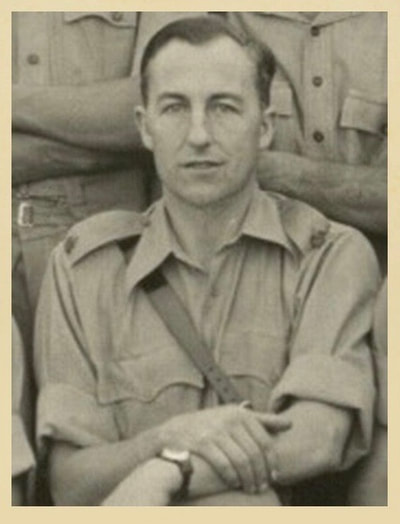

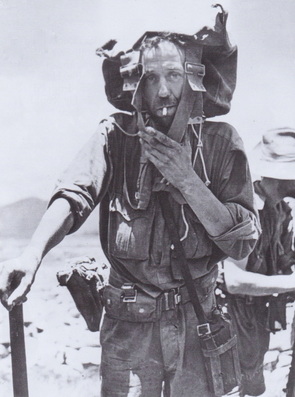

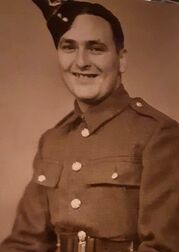

Pte. Arthur Almond.

Pte. Arthur Almond.

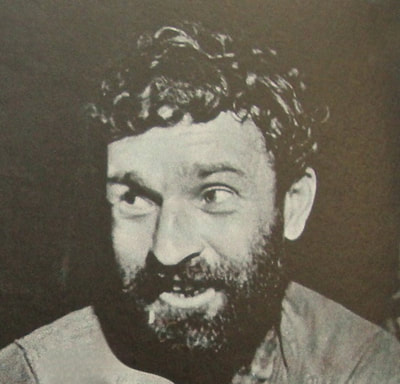

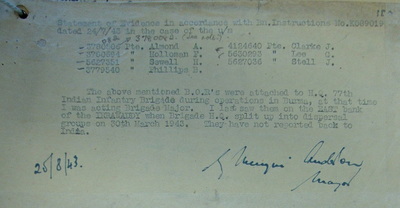

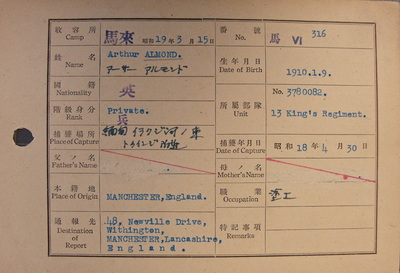

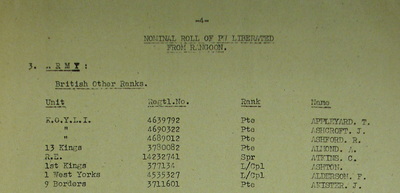

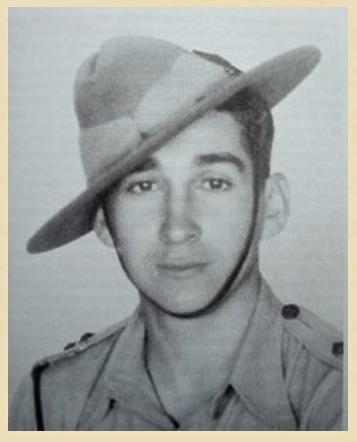

ALMOND, ARTHUR

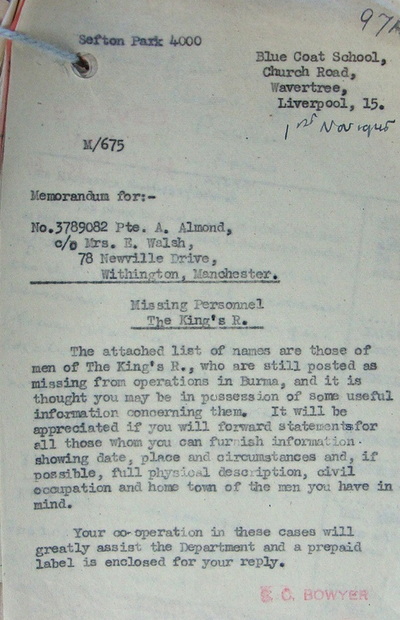

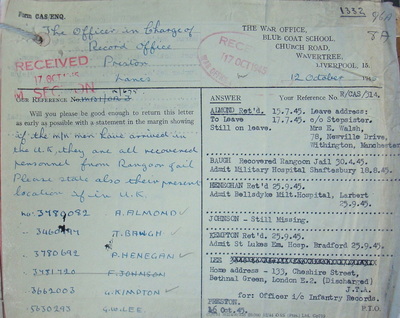

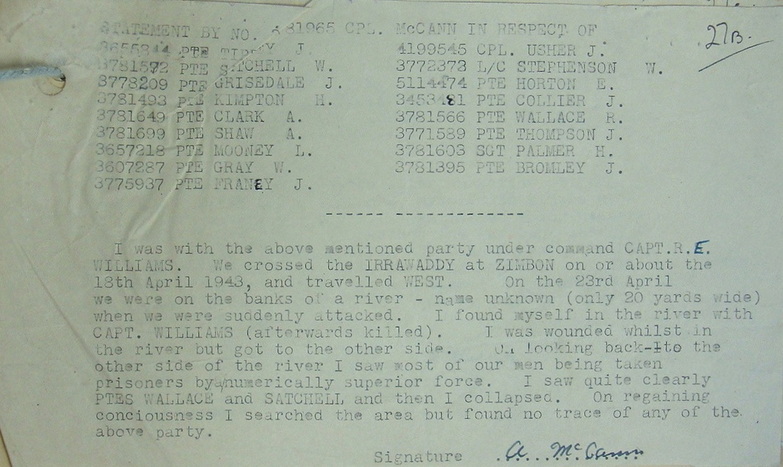

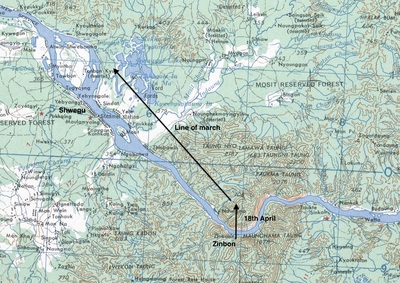

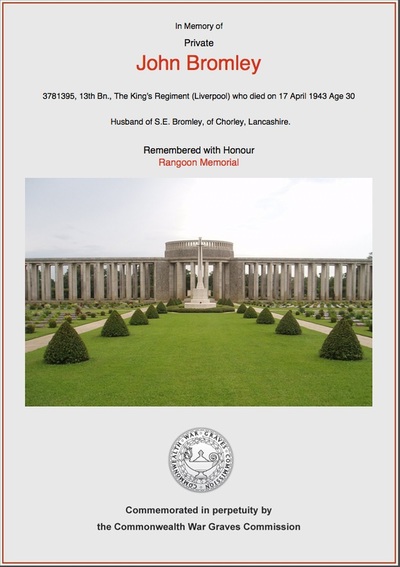

Pte. 3780082 Arthur Almond travelled to India with the original 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' in December 1941. He was posted to Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth and was last seen on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy on the 30th March 1943. Arthur was captured by the Japanese on the 30th April, close to the small Burmese village of Twinnge and was eventually transported to Rangoon Jail where he was given the POW number 316. Pte. Almond was liberated with some of his Chindit colleagues near the Burmese town of Pegu on the 29th April 1945.

On his return to the United Kingdom he assisted the Army Investigation Bureau based at the Blue Coat School, Wavertree in Liverpool, by giving information about many of the men missing and lost on the first Chindit expedition. From the various documents detailing Arthur's time in Burma, his Army service number is sometimes recorded as 3789082 as opposed to 3780082.

To read more about his time with Wingate's Brigade HQ and his possible membership of Captain Graham Hosegood's dispersal party, please click on the following link and scroll down towards the foot of the page.

In March 2016, I was fortunate to receive an email contact from Jo Walsh, the great niece of Pte. Arthur Almond:

Dear Steve,

Thank you so much for your wonderful website which has settled a family argument that has been running now for over 40 years, maybe even longer. I am the great niece of Private Arthur Almond, whom I see from your website was captured with Graham Hosegood. Uncle Arthur died in 1973 or 1974 at about the age of 65. Sadly, he had only just retired and died of bowel cancer which may have been in part due to what happened to him in Rangoon Jail.

I was about 14 when he died. I saw him all the time because after the war he came to live with my own Gran, who was his sister. My Gran was a widow and lived with her two children one of whom was my father, in a council house in Burnage an area to the south of Manchester city centre. We stayed there a lot at weekends, but Uncle Arthur rarely spoke to us other than when he came downstairs to go out in the morning, when he would say "morning" and exactly the same when he came back in the evening. Otherwise he used to remain in his room only venturing downstairs to eat in the kitchen or use the toilet.

My cousins and I were told he had been a Japanese POW and that his fingernails had been pulled out because he was a Signaller and Radio Operator. I am afraid to say that we spent all our time trying to catch a glimpse of these and indeed they were jagged stumps of nails. However, he did become a "parky" after the war and this would have been hard on his hands too.

At Christmas, when he came to our house , he would speak a little and we remember him saying after a few drinks, that the mules were the heroes in Burma. My Aunt recalls him saying that he survived being a prisoner of war because he came from a very poor family and hadn't been used to eating much food anyway, and it was those who thought of pork chops and were used to lots of food who found it hard and sometimes perished.

We were all aware that he had been captured and that he had said he was a Chindit. He also said he was attached to Ord Wingate's group too. That was pretty much all we ever knew. My mother always believed that he couldn't have been a Chindit, because he was too small and not tough enough. Well your website has proved that he clearly was extremely tough and that he was indeed a Chindit.

Sadly, his experience as a POW resonated throughout the rest of his life. He was a very solitary figure and tended to hoard everything he found during his workdays at the park, storing everything in his very small room at home. When he died my father found his demob suit and some old bully beef in his wardrobe, along with many other odd items. He was clearly suffering from what we now know as PTSD, but of course there was no help on offer back then.

The only other thing I remember is reading a beautifully written letter to my Gran which Arthur had sent home from India. He was a short man, with a slim wiry build and very quick when he walked. We now know he was a very tough man, I feel so proud him. Learning more about Uncle Arthur, has made me realise what a saint my Gran was too. How typical of her to take in and look after her step-brother after his terrible experiences in WW2. Thank you so much for what you have done in ensuring these men are remembered.

Jo's memories of her uncle resonated strongly with my own thoughts in relation to those Chindits who returned home to their families and everyday lives, and how their experiences in Burma and as prisoners of war affected them as men from that moment on. Like many other soldiers, Arthur, seemingly fortunate to survive his time in Rangoon Jail, would carry the experience with him for the rest of his life and suffer the emotions associated with his ordeal, conditions such as 'survivors syndrome.'

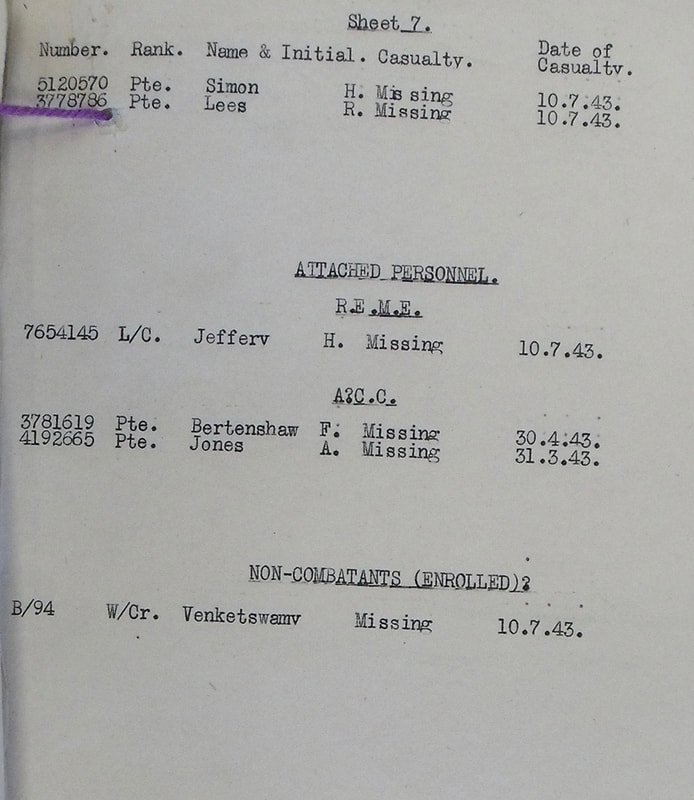

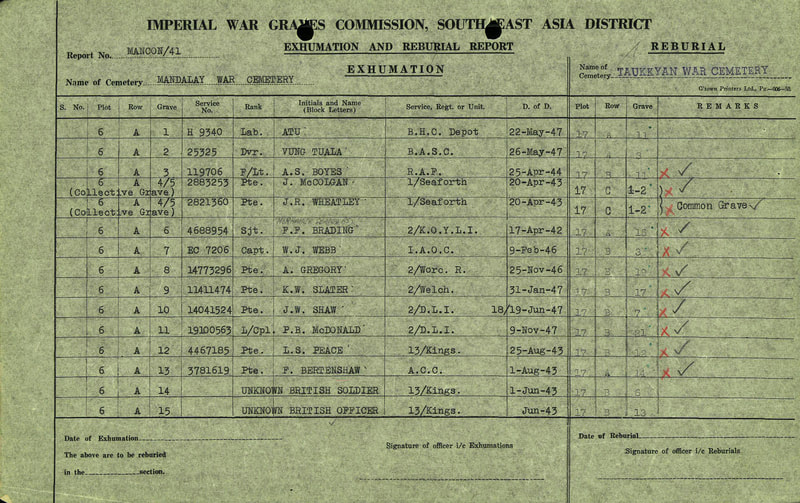

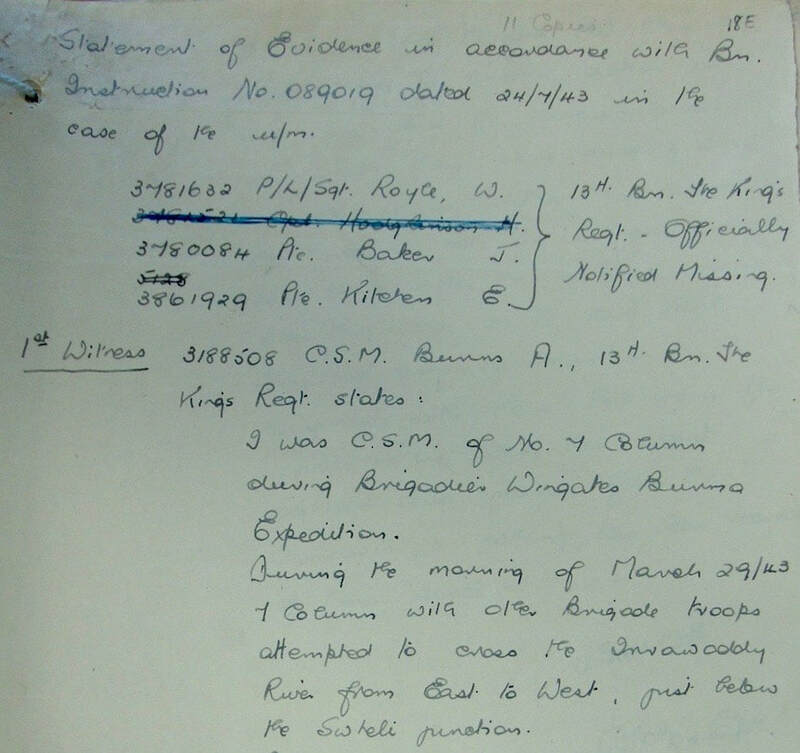

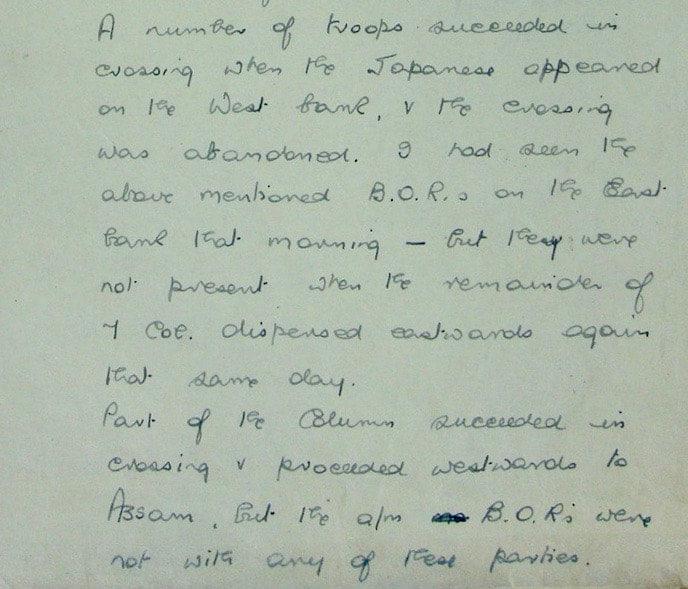

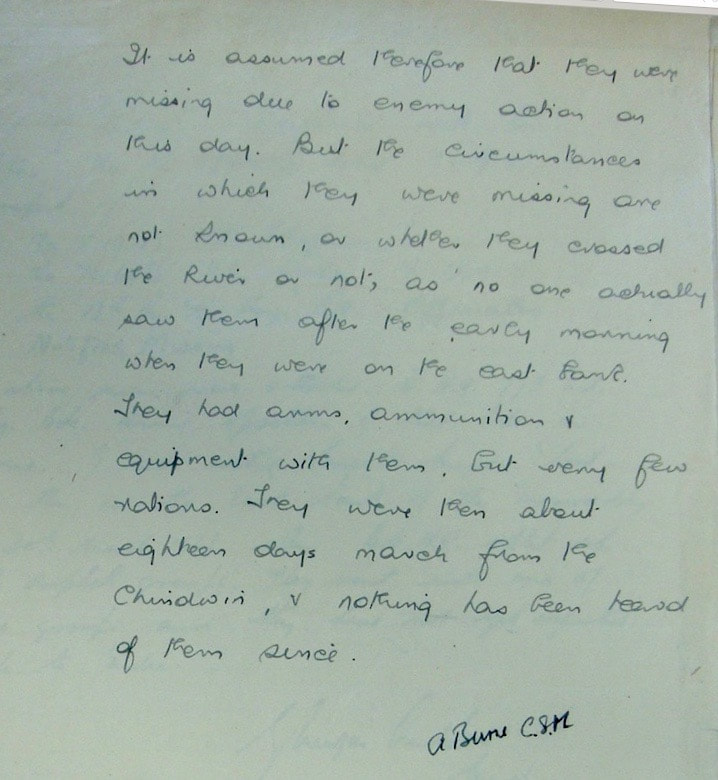

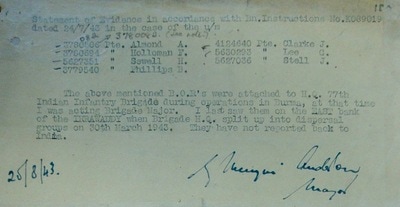

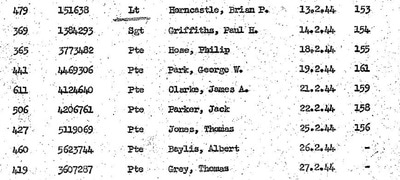

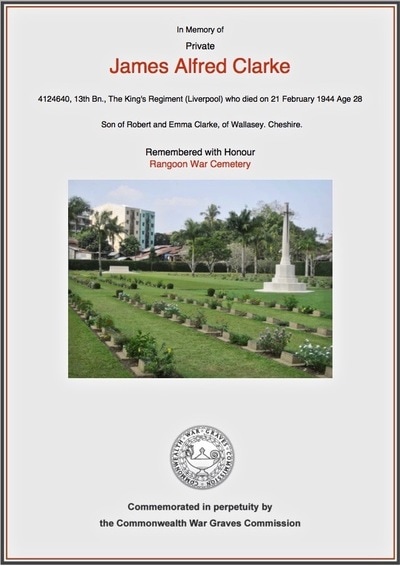

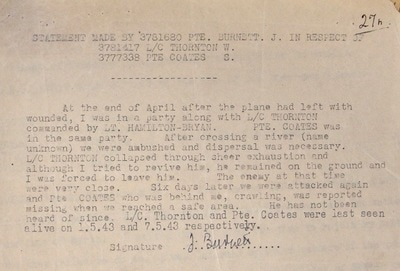

After the war, Arthur Almond assisted the Army Investigation Bureau in their attempt to discover what had happened to other casualties from the first Wingate expedition. This included a witness statement, where he listed the other men with whom he had shared his time as a prisoner of war. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to Pte. Almond, including these witness statement documents. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Jo Walsh for all her help in bringing the story of her Uncle Arthur to these website pages.

Pte. 3780082 Arthur Almond travelled to India with the original 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' in December 1941. He was posted to Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth and was last seen on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy on the 30th March 1943. Arthur was captured by the Japanese on the 30th April, close to the small Burmese village of Twinnge and was eventually transported to Rangoon Jail where he was given the POW number 316. Pte. Almond was liberated with some of his Chindit colleagues near the Burmese town of Pegu on the 29th April 1945.

On his return to the United Kingdom he assisted the Army Investigation Bureau based at the Blue Coat School, Wavertree in Liverpool, by giving information about many of the men missing and lost on the first Chindit expedition. From the various documents detailing Arthur's time in Burma, his Army service number is sometimes recorded as 3789082 as opposed to 3780082.

To read more about his time with Wingate's Brigade HQ and his possible membership of Captain Graham Hosegood's dispersal party, please click on the following link and scroll down towards the foot of the page.

In March 2016, I was fortunate to receive an email contact from Jo Walsh, the great niece of Pte. Arthur Almond:

Dear Steve,

Thank you so much for your wonderful website which has settled a family argument that has been running now for over 40 years, maybe even longer. I am the great niece of Private Arthur Almond, whom I see from your website was captured with Graham Hosegood. Uncle Arthur died in 1973 or 1974 at about the age of 65. Sadly, he had only just retired and died of bowel cancer which may have been in part due to what happened to him in Rangoon Jail.

I was about 14 when he died. I saw him all the time because after the war he came to live with my own Gran, who was his sister. My Gran was a widow and lived with her two children one of whom was my father, in a council house in Burnage an area to the south of Manchester city centre. We stayed there a lot at weekends, but Uncle Arthur rarely spoke to us other than when he came downstairs to go out in the morning, when he would say "morning" and exactly the same when he came back in the evening. Otherwise he used to remain in his room only venturing downstairs to eat in the kitchen or use the toilet.

My cousins and I were told he had been a Japanese POW and that his fingernails had been pulled out because he was a Signaller and Radio Operator. I am afraid to say that we spent all our time trying to catch a glimpse of these and indeed they were jagged stumps of nails. However, he did become a "parky" after the war and this would have been hard on his hands too.

At Christmas, when he came to our house , he would speak a little and we remember him saying after a few drinks, that the mules were the heroes in Burma. My Aunt recalls him saying that he survived being a prisoner of war because he came from a very poor family and hadn't been used to eating much food anyway, and it was those who thought of pork chops and were used to lots of food who found it hard and sometimes perished.

We were all aware that he had been captured and that he had said he was a Chindit. He also said he was attached to Ord Wingate's group too. That was pretty much all we ever knew. My mother always believed that he couldn't have been a Chindit, because he was too small and not tough enough. Well your website has proved that he clearly was extremely tough and that he was indeed a Chindit.

Sadly, his experience as a POW resonated throughout the rest of his life. He was a very solitary figure and tended to hoard everything he found during his workdays at the park, storing everything in his very small room at home. When he died my father found his demob suit and some old bully beef in his wardrobe, along with many other odd items. He was clearly suffering from what we now know as PTSD, but of course there was no help on offer back then.

The only other thing I remember is reading a beautifully written letter to my Gran which Arthur had sent home from India. He was a short man, with a slim wiry build and very quick when he walked. We now know he was a very tough man, I feel so proud him. Learning more about Uncle Arthur, has made me realise what a saint my Gran was too. How typical of her to take in and look after her step-brother after his terrible experiences in WW2. Thank you so much for what you have done in ensuring these men are remembered.

Jo's memories of her uncle resonated strongly with my own thoughts in relation to those Chindits who returned home to their families and everyday lives, and how their experiences in Burma and as prisoners of war affected them as men from that moment on. Like many other soldiers, Arthur, seemingly fortunate to survive his time in Rangoon Jail, would carry the experience with him for the rest of his life and suffer the emotions associated with his ordeal, conditions such as 'survivors syndrome.'

After the war, Arthur Almond assisted the Army Investigation Bureau in their attempt to discover what had happened to other casualties from the first Wingate expedition. This included a witness statement, where he listed the other men with whom he had shared his time as a prisoner of war. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to Pte. Almond, including these witness statement documents. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Jo Walsh for all her help in bringing the story of her Uncle Arthur to these website pages.

Cap badge of 2 Gurkha Rifles.

Cap badge of 2 Gurkha Rifles.

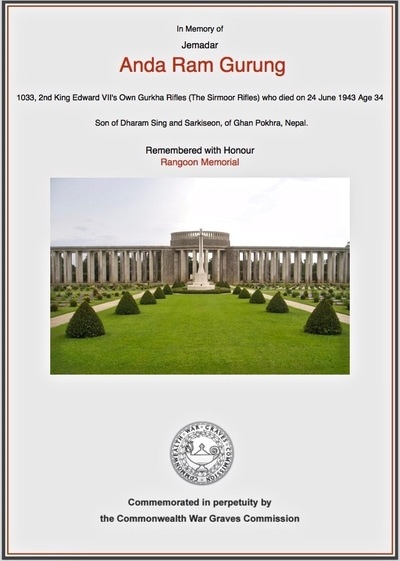

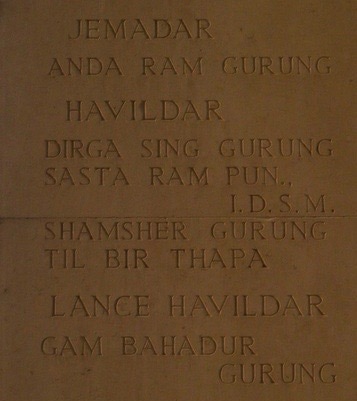

ANDA RAM GURUNG

Rank: Jemadar

Service No: 1033

Date of Death: 24/06/1943

Age: 34

Regiment/Service: 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles).

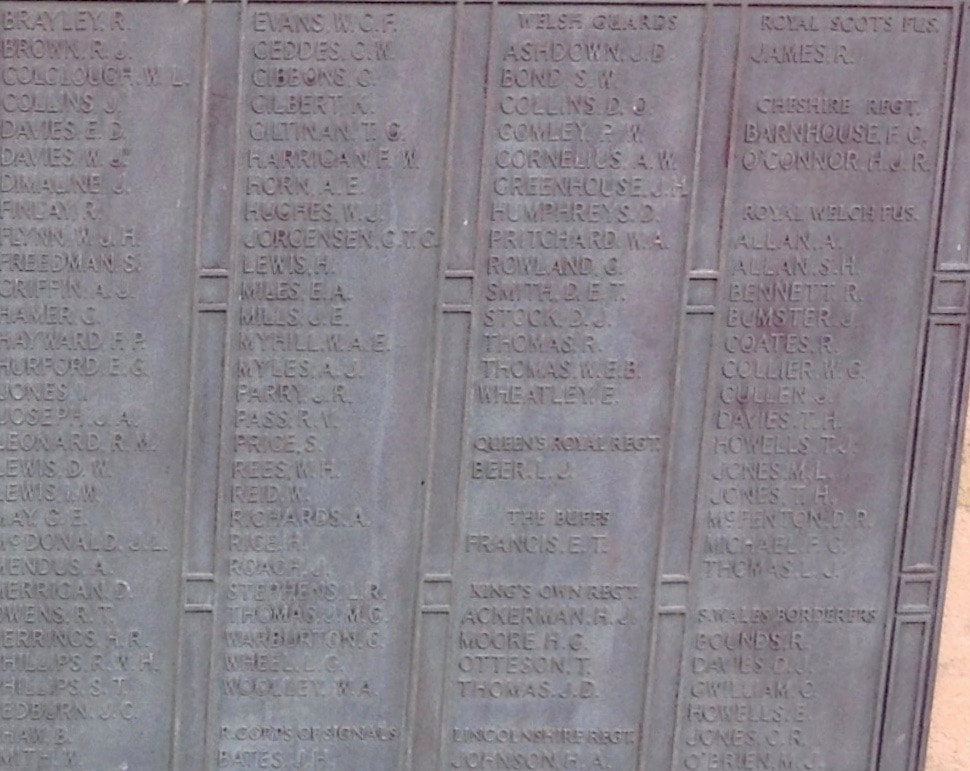

Memorial: Face 57 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2503458/ANDA%20RAM%20GURUNG

Chindit Column: 3

Other details:

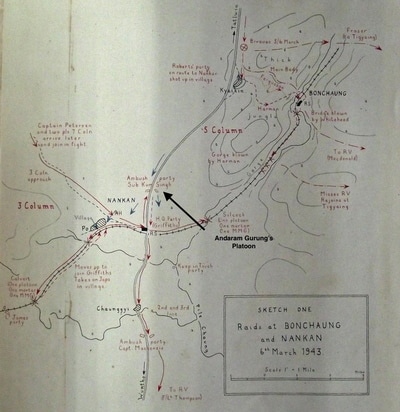

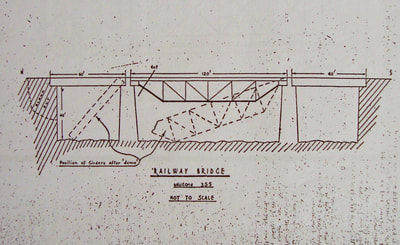

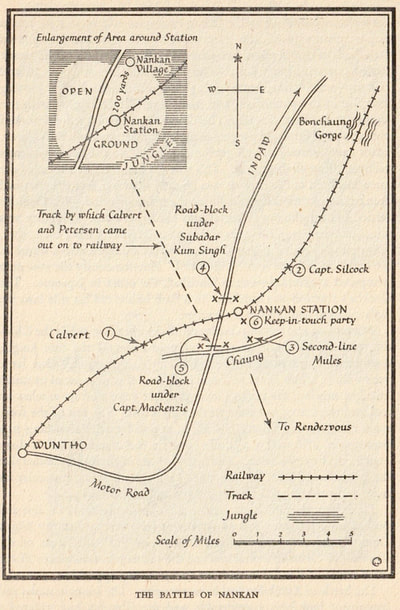

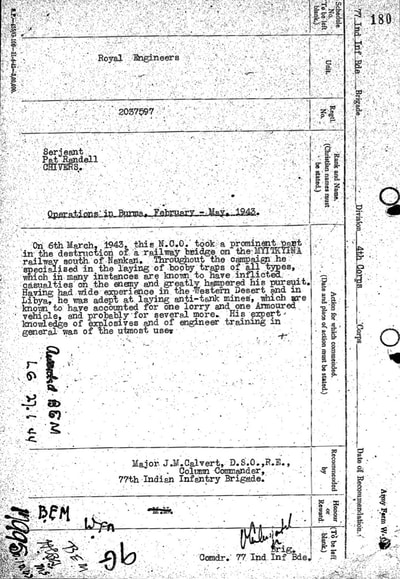

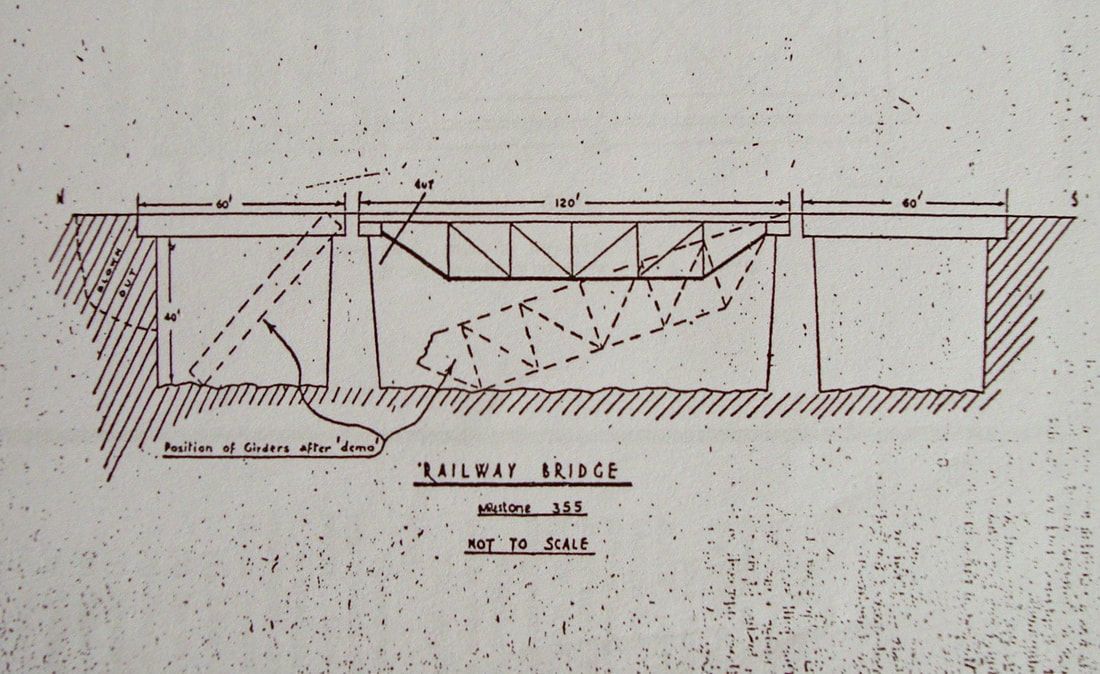

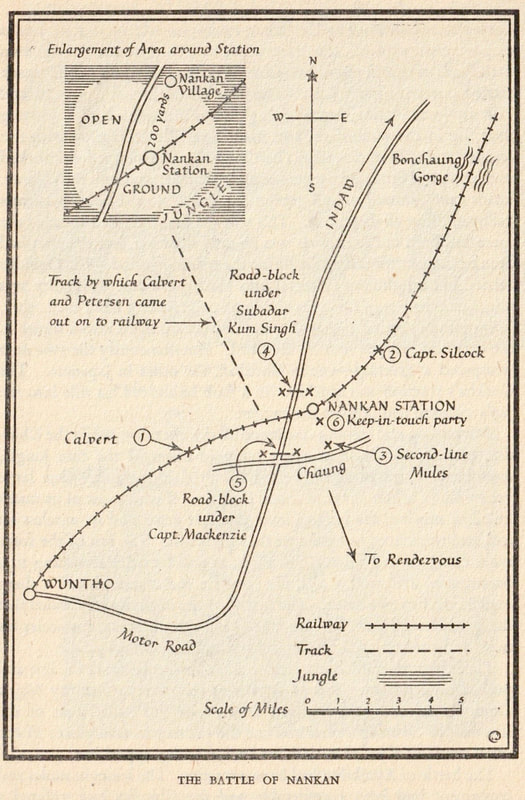

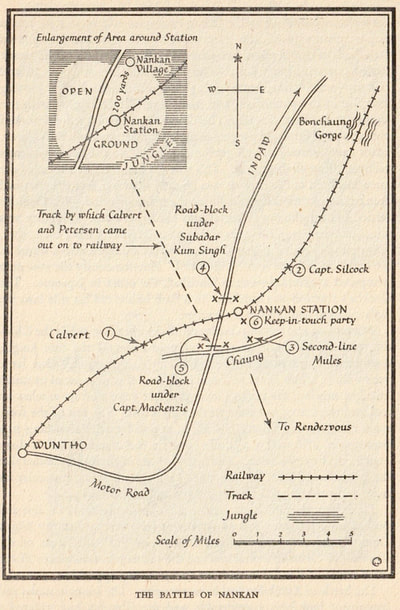

Anda Ram Gurung was the son of Dharam Sing and Sarkiseon, of Ghan Pokhra in Nepal. He was a junior platoon commander within the Gurkha Section of 3 Column led by Captain George Silcock. This unsung hero of Mike Calvert's unit led his men with great commitment and passion, gaining the well-meaning nickname of Under Arm from the British Gurkha officers in the column. Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung took control of a section of men at the Nankan rail station engagement with the Japanese on the 6th March 1943. He led his men in support of another Gurkha soldier, Subedar Kumba Sing, as he attempted to deal with an enemy ambush on the northern outskirts of the town.

Lieutenant Harold James, also a member of 3 Column on Operation Longcloth, remembered the young and trustworthy Jemadar in his book, Across the Threshold of Battle:

I was glad to be given a decent job and also that 13 Platoon was to be in my charge. The platoon's Gurkha Officer was Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung. He was universally liked and affectionately called 'Under Arm'. Slim, plucky, ugly but with a transforming smile when he laughed, which was very often, he was a man I came to know well and could really trust.

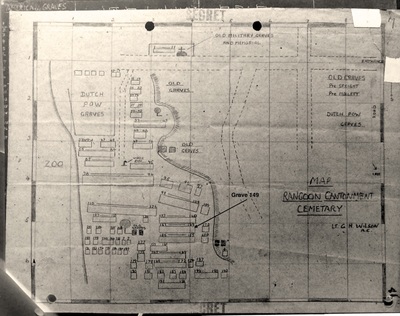

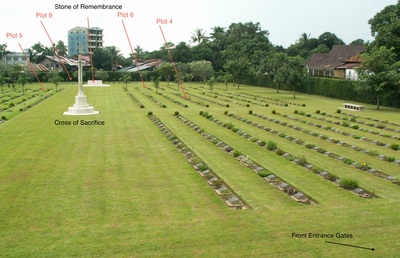

Sadly, having successfully reached the safety of India with 3 Column in April, Anda Ram Gurung later succumbed to a severe bout of malignant malaria whilst at home in Nepal and died on 24th June 1943. He is remembered upon Face 57 of the Rangoon Memorial, located as the centre piece of Taukkyan War Cemetery on the outskirts of Rangoon.

Seen below are a selection of images in relation to this short story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Jemadar

Service No: 1033

Date of Death: 24/06/1943

Age: 34

Regiment/Service: 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles).

Memorial: Face 57 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2503458/ANDA%20RAM%20GURUNG

Chindit Column: 3

Other details:

Anda Ram Gurung was the son of Dharam Sing and Sarkiseon, of Ghan Pokhra in Nepal. He was a junior platoon commander within the Gurkha Section of 3 Column led by Captain George Silcock. This unsung hero of Mike Calvert's unit led his men with great commitment and passion, gaining the well-meaning nickname of Under Arm from the British Gurkha officers in the column. Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung took control of a section of men at the Nankan rail station engagement with the Japanese on the 6th March 1943. He led his men in support of another Gurkha soldier, Subedar Kumba Sing, as he attempted to deal with an enemy ambush on the northern outskirts of the town.

Lieutenant Harold James, also a member of 3 Column on Operation Longcloth, remembered the young and trustworthy Jemadar in his book, Across the Threshold of Battle:

I was glad to be given a decent job and also that 13 Platoon was to be in my charge. The platoon's Gurkha Officer was Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung. He was universally liked and affectionately called 'Under Arm'. Slim, plucky, ugly but with a transforming smile when he laughed, which was very often, he was a man I came to know well and could really trust.

Sadly, having successfully reached the safety of India with 3 Column in April, Anda Ram Gurung later succumbed to a severe bout of malignant malaria whilst at home in Nepal and died on 24th June 1943. He is remembered upon Face 57 of the Rangoon Memorial, located as the centre piece of Taukkyan War Cemetery on the outskirts of Rangoon.

Seen below are a selection of images in relation to this short story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

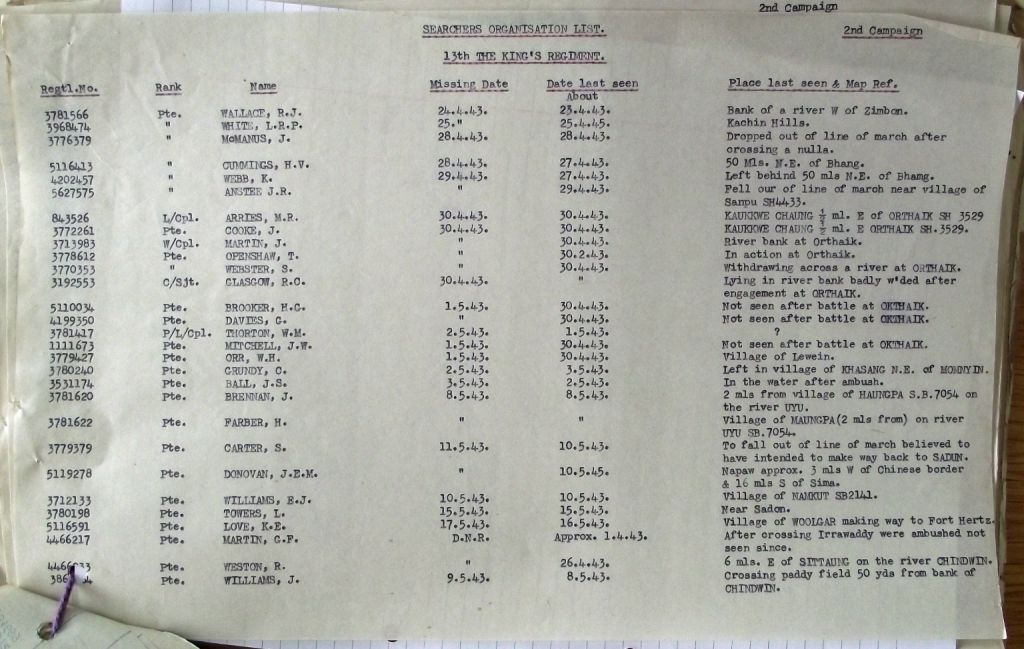

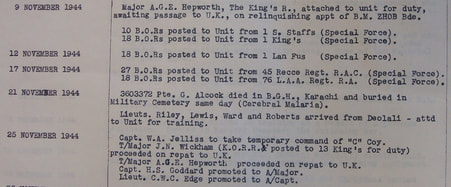

ANSTEE, JOHN RICHARD

Rank: Private

Service No: 5627575

Date of Death: 29/04/1943

Age:28

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

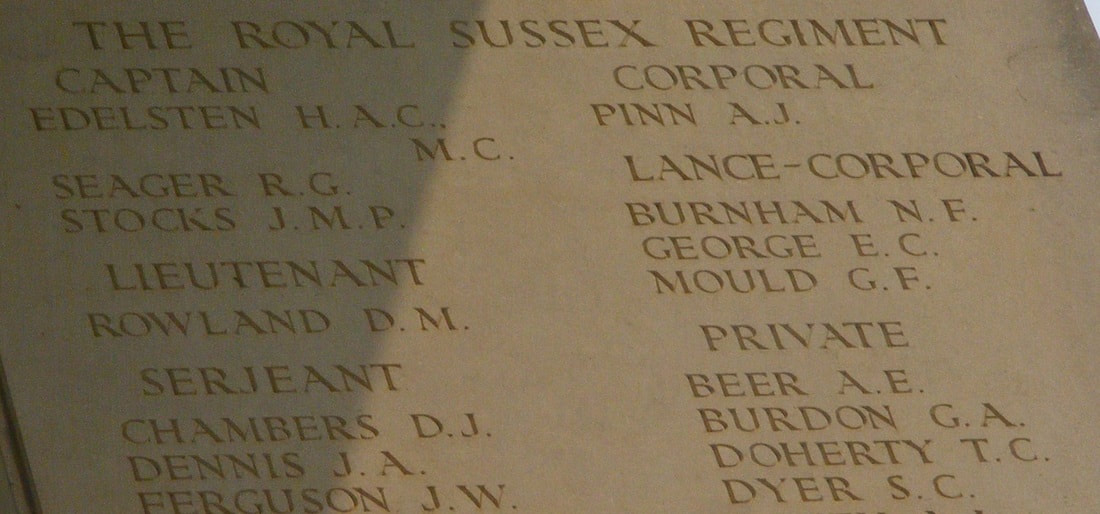

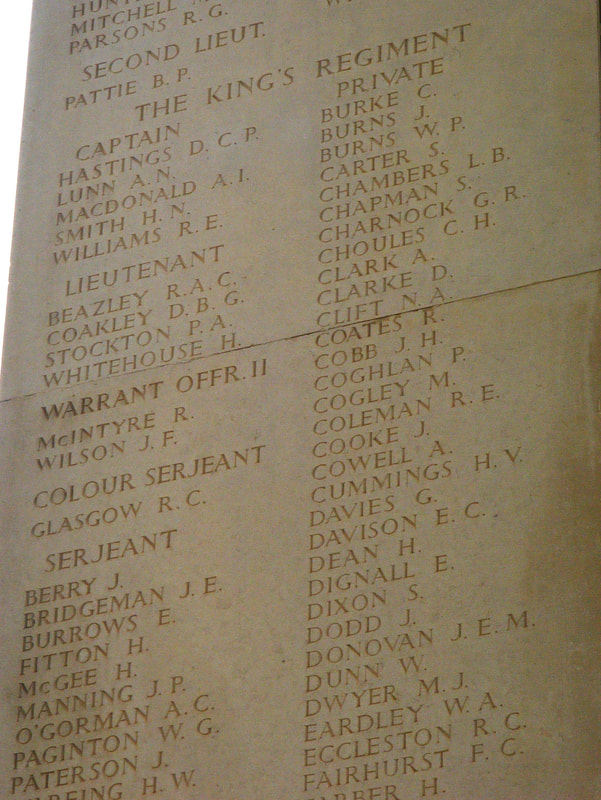

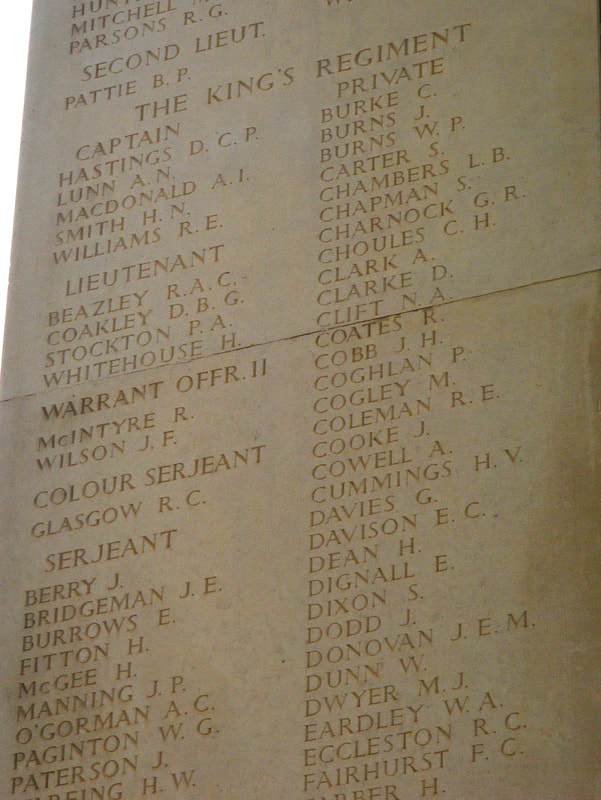

Memorial: Face 6 Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2503523/anstee,-john-richard/#&gid=null&pid=1

Chindit column: 7

Other details:

John Richard Anstee was born on the 18th May 1914 and was the son of John and Florence Anstee from Wembley in North London. John was a Gas Company employee in civilian life and married Ellen A. Evans from Stoke Newington in 1939. John Anstee was originally posted to the Devonshire Regiment early in WW2 and served with the 12th Battalion up until July 1942 before being sent overseas to India. After a short period at the British Base Reinforcement Centre in Deolali, he and a small draft of soldiers from the Devonshire Regiment were transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment and joined 77th Brigade at their Chindit training camp in Saugor on the 26th September 1942.

To read more about the men from the Devonshire Regiment who became Chindits in September 1942, please click on the following link:

The Devonshire's Journey

John was allocated to No. 7 Column at Saugor and fell under the command of Major Kenneth Gilkes, formerly of the North Staffordshire Regiment. Gilkes was a well-liked and respected leader and during the weeks of Operation Longcloth his column generally shadowed Brigadier Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters. Once the order to disperse was called in late March 1943, Gilkes decided to make for the Chinese borders in order to exit Burma. No. 7 Column were fully re-fitted with new uniforms and equipment in early April and enjoyed a supply drop of food and ammunition shortly after crossing the Shweli River. Gilkes was confident that his men should have the means to make the longer, but hopefully safer route out of Burma that year. The trip out into China and then hugging the borders until the grain of the country led them to Fort Hertz would take on average 4-6 weeks longer than marching directly west towards the Chindwin River.

Along the way the dispersal groups from 7 Column would endure great hardship as they combatted the wild and exposed terrain of the Chinese borders. Eventually many of Gilkes' men reached areas occupied by Chinese troops and were well treated and more importantly well fed by their Allies. On reaching their final safe haven at Yunnani the column enjoyed the very great luxury of a lift home in the USAAF Dakotas that were present in the area, arriving back in India in some cases as late as mid-June.

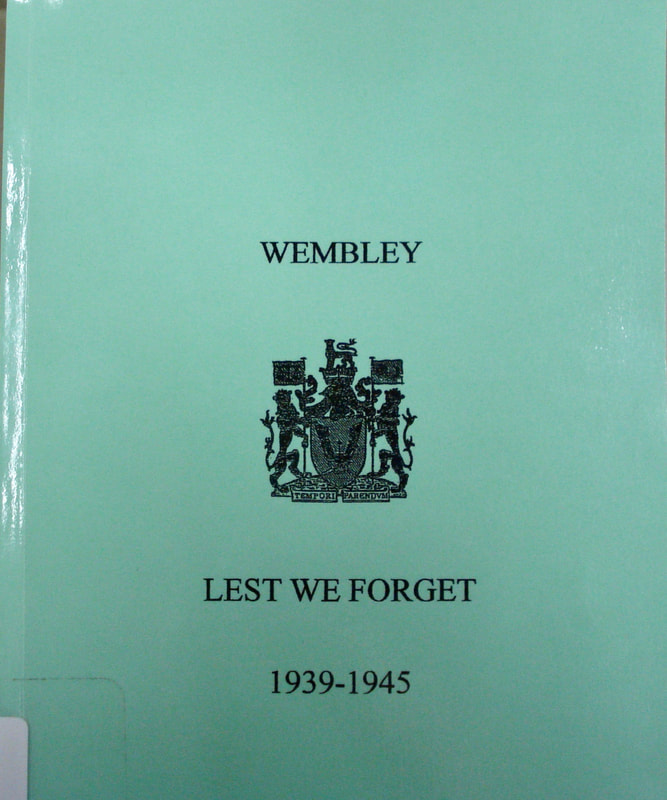

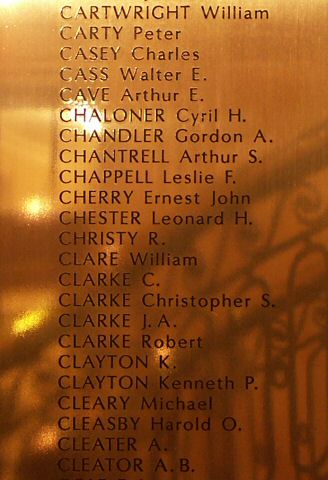

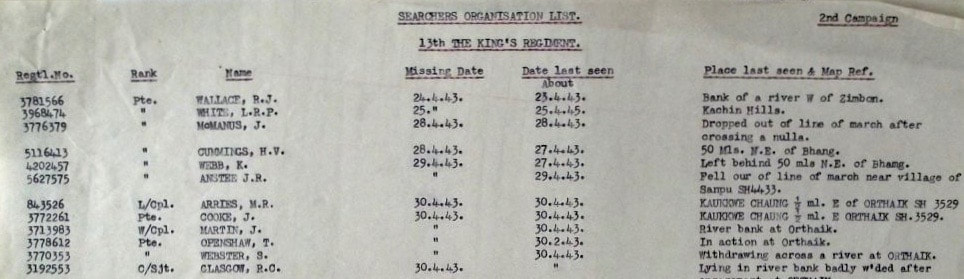

Sadly, John Anstee did not succeed in reaching the Chinese Yunnan Province in 1943, falling out of the line of march on the 29th April 1943 near a Kachin village named Sanpu (Map reference SH4433). Frustratingly, this is all we know of his last known movements and for this reason he was listed as missing in action as of the 29th April. When no further information came forward after the war and no grave for John Anstee could be identified, his name was added to the Rangoon War Memorial located at Taukkyan War Cemetery. This memorial contains the names of over 26,000 casualties from the Burma Campaign who have no known grave. John Anstee is also remembered within the pages of the Wembley Town Book of Remembrance, compiling the names of WW2 casualties from the local area and details of their service.

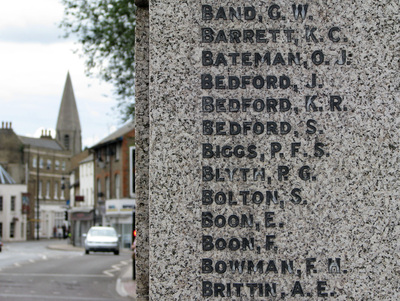

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a photograph of John's inscription upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: 5627575

Date of Death: 29/04/1943

Age:28

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 6 Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2503523/anstee,-john-richard/#&gid=null&pid=1

Chindit column: 7

Other details:

John Richard Anstee was born on the 18th May 1914 and was the son of John and Florence Anstee from Wembley in North London. John was a Gas Company employee in civilian life and married Ellen A. Evans from Stoke Newington in 1939. John Anstee was originally posted to the Devonshire Regiment early in WW2 and served with the 12th Battalion up until July 1942 before being sent overseas to India. After a short period at the British Base Reinforcement Centre in Deolali, he and a small draft of soldiers from the Devonshire Regiment were transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment and joined 77th Brigade at their Chindit training camp in Saugor on the 26th September 1942.

To read more about the men from the Devonshire Regiment who became Chindits in September 1942, please click on the following link:

The Devonshire's Journey

John was allocated to No. 7 Column at Saugor and fell under the command of Major Kenneth Gilkes, formerly of the North Staffordshire Regiment. Gilkes was a well-liked and respected leader and during the weeks of Operation Longcloth his column generally shadowed Brigadier Wingate and his Brigade Head Quarters. Once the order to disperse was called in late March 1943, Gilkes decided to make for the Chinese borders in order to exit Burma. No. 7 Column were fully re-fitted with new uniforms and equipment in early April and enjoyed a supply drop of food and ammunition shortly after crossing the Shweli River. Gilkes was confident that his men should have the means to make the longer, but hopefully safer route out of Burma that year. The trip out into China and then hugging the borders until the grain of the country led them to Fort Hertz would take on average 4-6 weeks longer than marching directly west towards the Chindwin River.

Along the way the dispersal groups from 7 Column would endure great hardship as they combatted the wild and exposed terrain of the Chinese borders. Eventually many of Gilkes' men reached areas occupied by Chinese troops and were well treated and more importantly well fed by their Allies. On reaching their final safe haven at Yunnani the column enjoyed the very great luxury of a lift home in the USAAF Dakotas that were present in the area, arriving back in India in some cases as late as mid-June.

Sadly, John Anstee did not succeed in reaching the Chinese Yunnan Province in 1943, falling out of the line of march on the 29th April 1943 near a Kachin village named Sanpu (Map reference SH4433). Frustratingly, this is all we know of his last known movements and for this reason he was listed as missing in action as of the 29th April. When no further information came forward after the war and no grave for John Anstee could be identified, his name was added to the Rangoon War Memorial located at Taukkyan War Cemetery. This memorial contains the names of over 26,000 casualties from the Burma Campaign who have no known grave. John Anstee is also remembered within the pages of the Wembley Town Book of Remembrance, compiling the names of WW2 casualties from the local area and details of their service.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a photograph of John's inscription upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

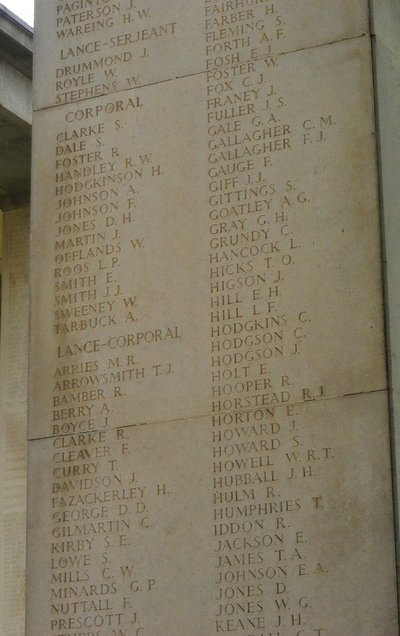

ARRIES, MANSFIELD ROBERT

Rank: Lance Corporal

Service No: 843526

Date of Death: 30/04/1943

Age:26

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 5 Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2503698/ARRIES,%20MANSFIELD%20ROBERT

Chindit column: Northern Group Head Quarters.

Other details:

Lance Corporal Mansfield Arries was born in Morpeth, Northumberland during the first quarter of 1917. He married Annie Eastley in the first quarter of 1936 and was originally a soldier with the Royal Artillery, holding a post at the Royal Citadel in Plymouth from before the years of WW2. It would seem by all accounts that Gunner Mansfield was a bit of a scallywag; from the pages of the Western Morning News dated 2nd April 1938:

Charged with having stolen two cheques to the value of 4d. Mansfield Robert Arries aged 21, a Gunner stationed at the Royal Citadel, Plymouth, was remanded in the charge of the Military authorities for one week by Plymouth Magistrates yesterday. Detective Sergeant Cheffers gave evidence of the arrest and in reply to Superintendent W.T. Hutchings said additional charges would be preferred.

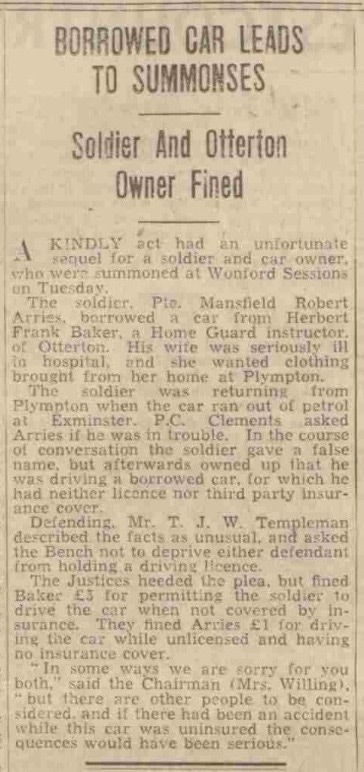

Three years later, Mansfield was in trouble again. From the Western Times dated 26th September 1941and under the headline,

Borrowed Car Leads to Summonses:

A kindly act had an unfortunate sequel for a soldier and car owner, who were summoned at Wonford Sessions (Exeter) on Tuesday. The soldier, Pte. Mansfield Robert Arries, borrowed a car from Herbert Frank Baker, a Home guard instructor from Otterton. Arries wife was seriously ill in hospital, and she wanted clothing brought from her home in Plympton. The soldier was returning from Plympton when the car ran out of petrol at Exminister. Police Constable Clements asked Arries if he was in trouble. In the course of the conversation the soldier gave a false name, but afterwards owned up that he was driving a borrowed car, for which he had neither licence nor third party insurance cover.

Defending, Mr. TJW. Templeman described the facts as unusual, and asked the Bench not to deprive either defendant from holding a driving licence. The Justices heeded the plea, but fined Baker £3 for permitting the soldier to drive the car when not covered by insurance. They then fined Arries £1 for driving the car while unlicensed and having no insurance. "In some ways we are sorry for you both," said the Chairman (Mrs. Willing), "but there are other people to be considered, and if there had been an accident while this car was uninsured the consequences would have been serious."

From the pages of the Western Morning News dated 14th October 1941 and under the headline,

Radio Set Theft, Soldier Sent to Prison at Exmouth:

For stealing a wireless set value £7 7s. the property of Pte. H. Harvey on March 25th last. Pte. Mansfield Robert Arries was sentenced to one month's hard labour at Exmouth yesterday, with a case of stealing a wristlet watch value £2 to be taken into consideration. Inspector Abrahams said that Pte. Harvey was formerly billeted at Exmouth and was transferred to the Plymouth District. He owned a wireless set and asked a Sgt. Hancock to send it on to him. On March 25th, hearing that the accused was going to Plymouth on leave the Sergeant asked him to deliver the set to Harvey. Harvey did not receive the wireless set and inquiries showed that Arries had sold it to a wireless dealer from Exeter for £1. The theft of the watch by Arries from a comrade was a mean trick. He took the watch to Exeter, and had it put into a new case.

Not long after his release from Exmouth Jail, Mansfield was posted overseas to India and eventually transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment at Secunderabad. He became part of Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth under the command of Lt-Colonel S.A. Cooke formerly of the Lincolnshire Regiment. It is believed that before his transfer to the King's, that Pte. Arries had served on the North West Frontier in some capacity.

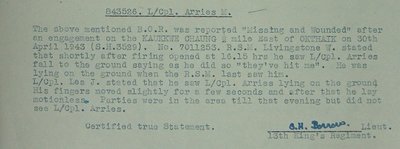

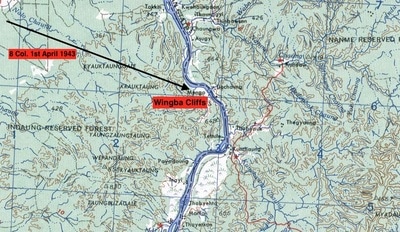

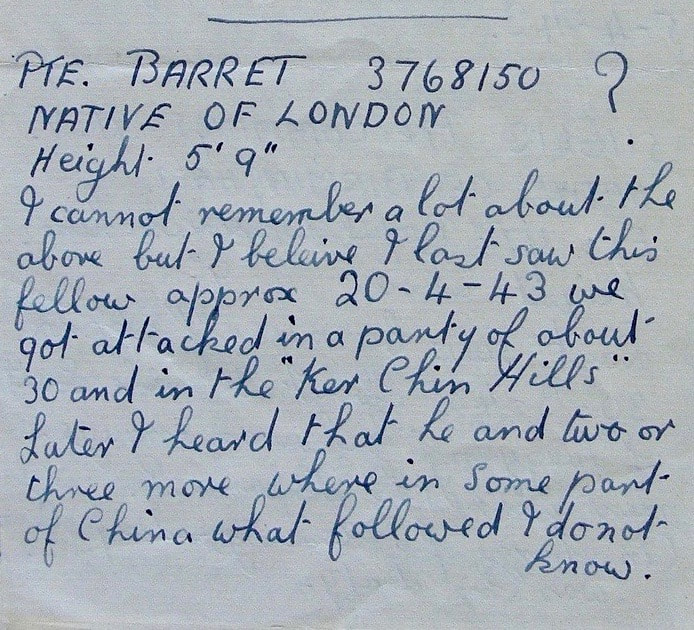

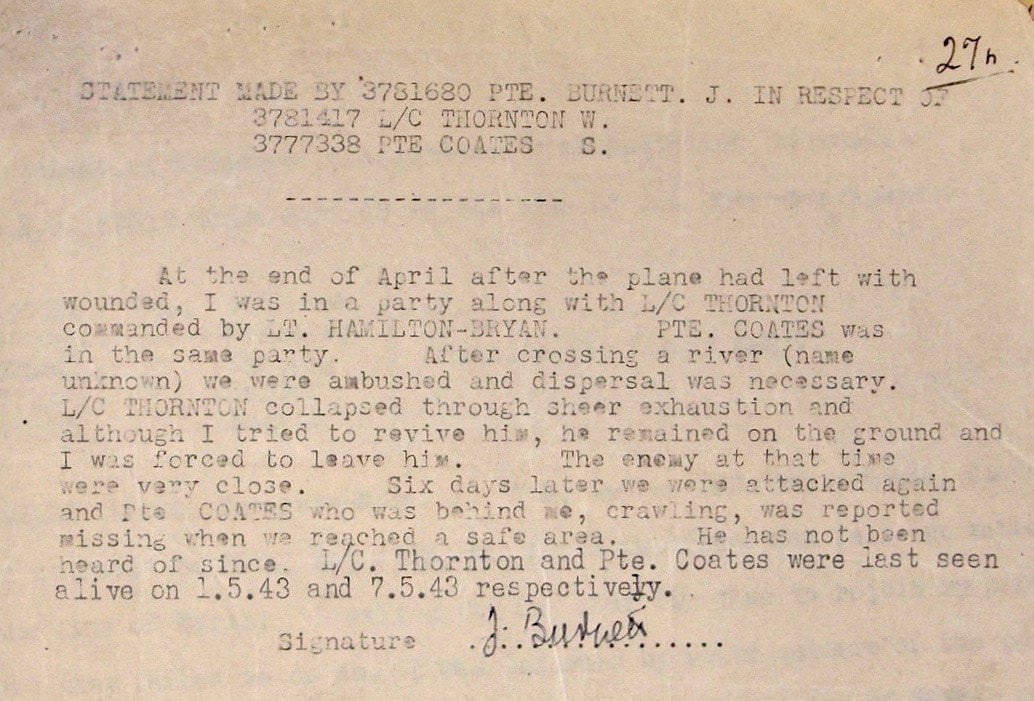

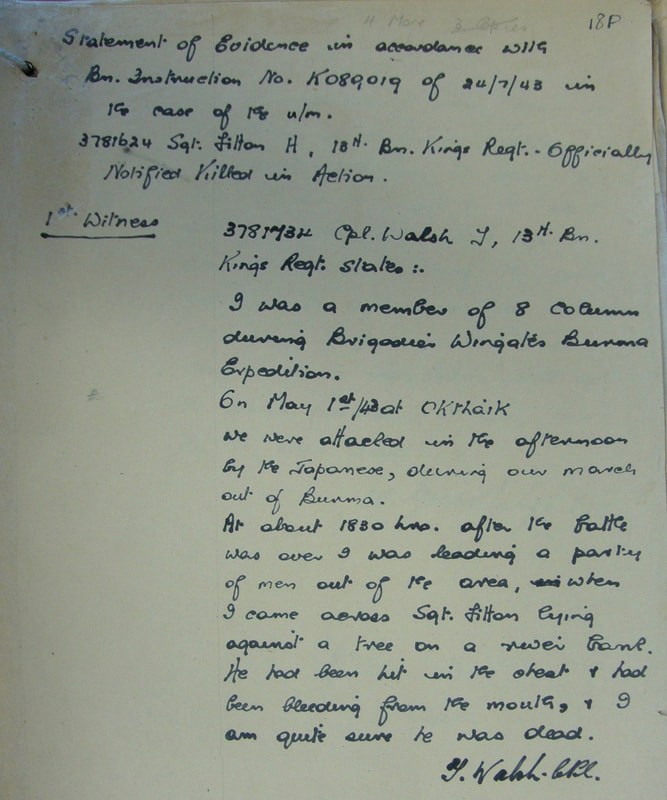

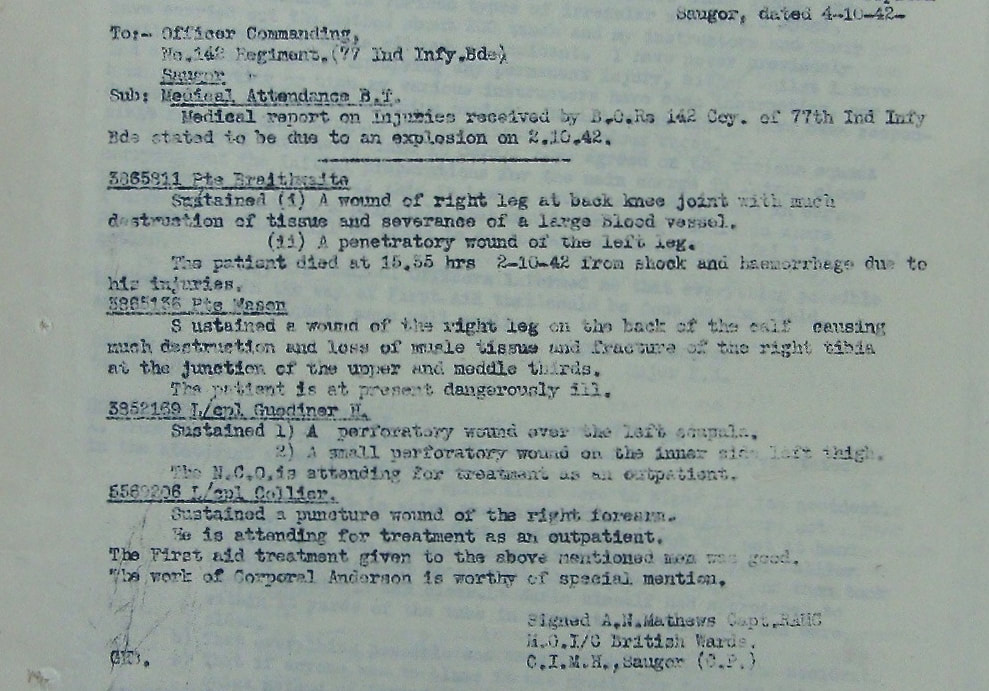

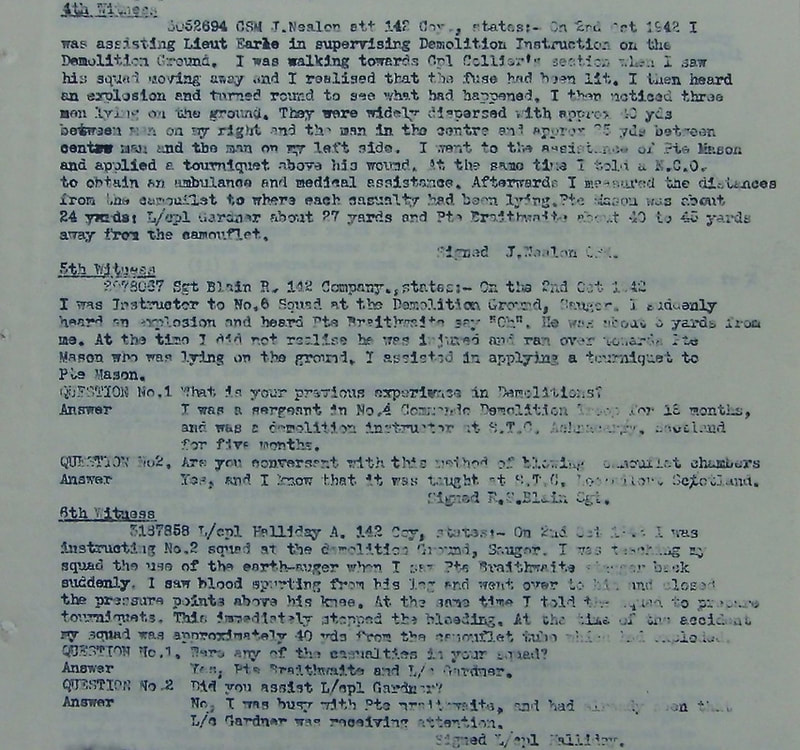

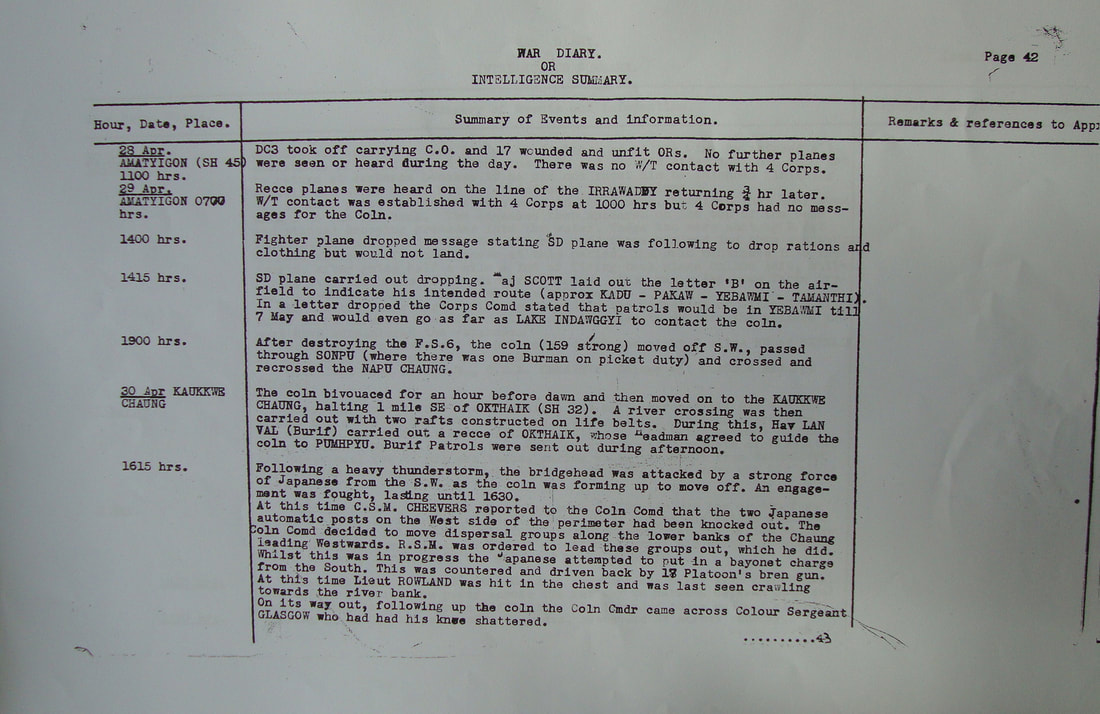

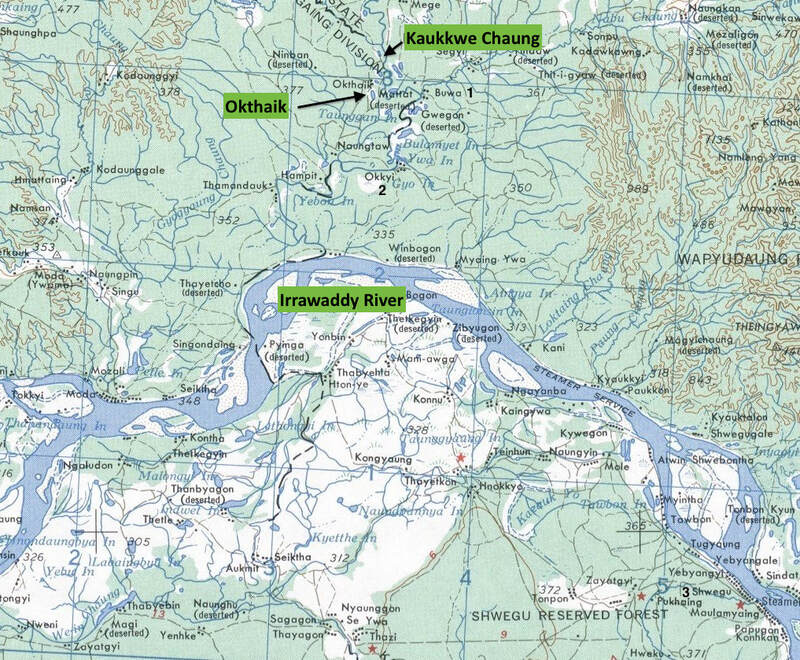

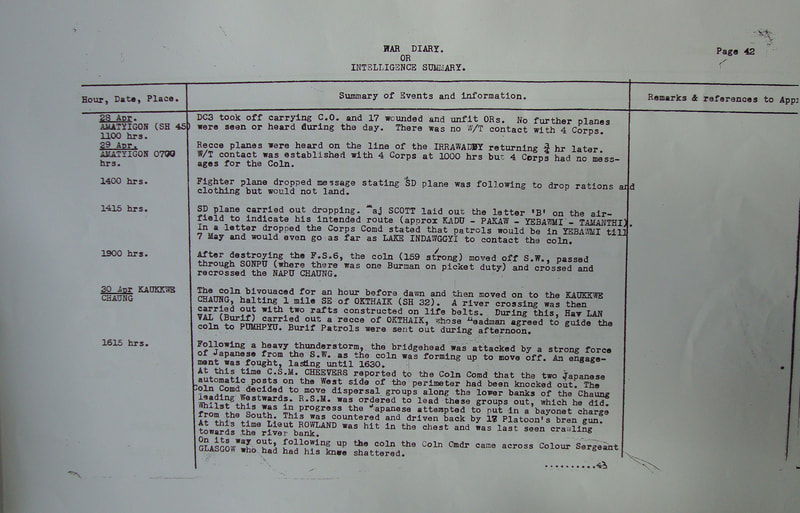

Mansfield Arries became a casualty on Operation Longcloth during 8 Column's engagement with the Japanese at the Kaukkwe Chaung, a fast flowing river close to the village of Okthaik. From a witness statement given by several Chindit comrades after retuning to India in 1943:

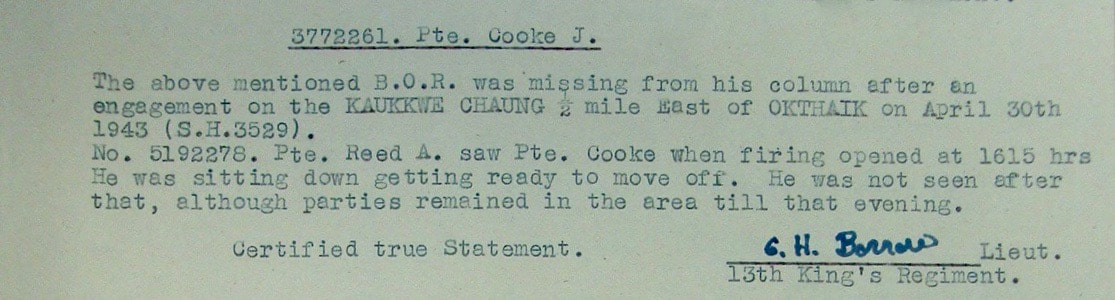

The above mentioned British Other Rank (Arries) was reported as missing and wounded after an engagement on the Kaukkwe Chaung, half a mile east of Okthaik on the 30th April 1943. No. 7011253 RSM W. Livingstone stated that shortly after firing had opened at 16.15hrs., he saw L/Cpl. Arries lying on the ground saying as he did so, "they've hit me." He was still lying on the ground when the RSM last saw him. L/Cpl. F. Lea stated that he saw Arries lying on the ground; his fingers moved slightly for a few seconds and after that he lay motionless. Parties were in the area till that evening, but did not see L/Cpl. Arries. Statement certified as true by Lt. G.H. Borrow, 13th King's Regiment.

To read more about the battle at the Kaukkwe Chaung, please click on the following link: Frank Lea, Ellis Grundy and the Kaukkwe Chaung

From another statement, this time from returning POW, Corporal Fred Morgan of 7 Column:

The last time I saw Arries (who was six foot tall with a ruddy complexion) was on the east side of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March 1943. He was in Company HQ with the C.O. from the 13th King's. I believe he served in India before the war on the Frontier.

Pte. Mansfield Arries was never heard of again after the engagement with the Japanese at the Kaukkwe Chaung and his body was never recovered after the war. For this reason he is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, located within the grounds of Taukkyan War Cemetery in Burma. The memorial contains the names of over 26,000 casualties from the Burma Campaign who have no known grave. Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring forward on the page.

Rank: Lance Corporal

Service No: 843526

Date of Death: 30/04/1943

Age:26

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 5 Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2503698/ARRIES,%20MANSFIELD%20ROBERT

Chindit column: Northern Group Head Quarters.

Other details:

Lance Corporal Mansfield Arries was born in Morpeth, Northumberland during the first quarter of 1917. He married Annie Eastley in the first quarter of 1936 and was originally a soldier with the Royal Artillery, holding a post at the Royal Citadel in Plymouth from before the years of WW2. It would seem by all accounts that Gunner Mansfield was a bit of a scallywag; from the pages of the Western Morning News dated 2nd April 1938:

Charged with having stolen two cheques to the value of 4d. Mansfield Robert Arries aged 21, a Gunner stationed at the Royal Citadel, Plymouth, was remanded in the charge of the Military authorities for one week by Plymouth Magistrates yesterday. Detective Sergeant Cheffers gave evidence of the arrest and in reply to Superintendent W.T. Hutchings said additional charges would be preferred.

Three years later, Mansfield was in trouble again. From the Western Times dated 26th September 1941and under the headline,

Borrowed Car Leads to Summonses:

A kindly act had an unfortunate sequel for a soldier and car owner, who were summoned at Wonford Sessions (Exeter) on Tuesday. The soldier, Pte. Mansfield Robert Arries, borrowed a car from Herbert Frank Baker, a Home guard instructor from Otterton. Arries wife was seriously ill in hospital, and she wanted clothing brought from her home in Plympton. The soldier was returning from Plympton when the car ran out of petrol at Exminister. Police Constable Clements asked Arries if he was in trouble. In the course of the conversation the soldier gave a false name, but afterwards owned up that he was driving a borrowed car, for which he had neither licence nor third party insurance cover.

Defending, Mr. TJW. Templeman described the facts as unusual, and asked the Bench not to deprive either defendant from holding a driving licence. The Justices heeded the plea, but fined Baker £3 for permitting the soldier to drive the car when not covered by insurance. They then fined Arries £1 for driving the car while unlicensed and having no insurance. "In some ways we are sorry for you both," said the Chairman (Mrs. Willing), "but there are other people to be considered, and if there had been an accident while this car was uninsured the consequences would have been serious."

From the pages of the Western Morning News dated 14th October 1941 and under the headline,

Radio Set Theft, Soldier Sent to Prison at Exmouth:

For stealing a wireless set value £7 7s. the property of Pte. H. Harvey on March 25th last. Pte. Mansfield Robert Arries was sentenced to one month's hard labour at Exmouth yesterday, with a case of stealing a wristlet watch value £2 to be taken into consideration. Inspector Abrahams said that Pte. Harvey was formerly billeted at Exmouth and was transferred to the Plymouth District. He owned a wireless set and asked a Sgt. Hancock to send it on to him. On March 25th, hearing that the accused was going to Plymouth on leave the Sergeant asked him to deliver the set to Harvey. Harvey did not receive the wireless set and inquiries showed that Arries had sold it to a wireless dealer from Exeter for £1. The theft of the watch by Arries from a comrade was a mean trick. He took the watch to Exeter, and had it put into a new case.

Not long after his release from Exmouth Jail, Mansfield was posted overseas to India and eventually transferred to the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment at Secunderabad. He became part of Northern Group Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth under the command of Lt-Colonel S.A. Cooke formerly of the Lincolnshire Regiment. It is believed that before his transfer to the King's, that Pte. Arries had served on the North West Frontier in some capacity.

Mansfield Arries became a casualty on Operation Longcloth during 8 Column's engagement with the Japanese at the Kaukkwe Chaung, a fast flowing river close to the village of Okthaik. From a witness statement given by several Chindit comrades after retuning to India in 1943:

The above mentioned British Other Rank (Arries) was reported as missing and wounded after an engagement on the Kaukkwe Chaung, half a mile east of Okthaik on the 30th April 1943. No. 7011253 RSM W. Livingstone stated that shortly after firing had opened at 16.15hrs., he saw L/Cpl. Arries lying on the ground saying as he did so, "they've hit me." He was still lying on the ground when the RSM last saw him. L/Cpl. F. Lea stated that he saw Arries lying on the ground; his fingers moved slightly for a few seconds and after that he lay motionless. Parties were in the area till that evening, but did not see L/Cpl. Arries. Statement certified as true by Lt. G.H. Borrow, 13th King's Regiment.

To read more about the battle at the Kaukkwe Chaung, please click on the following link: Frank Lea, Ellis Grundy and the Kaukkwe Chaung

From another statement, this time from returning POW, Corporal Fred Morgan of 7 Column:

The last time I saw Arries (who was six foot tall with a ruddy complexion) was on the east side of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March 1943. He was in Company HQ with the C.O. from the 13th King's. I believe he served in India before the war on the Frontier.

Pte. Mansfield Arries was never heard of again after the engagement with the Japanese at the Kaukkwe Chaung and his body was never recovered after the war. For this reason he is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, located within the grounds of Taukkyan War Cemetery in Burma. The memorial contains the names of over 26,000 casualties from the Burma Campaign who have no known grave. Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring forward on the page.

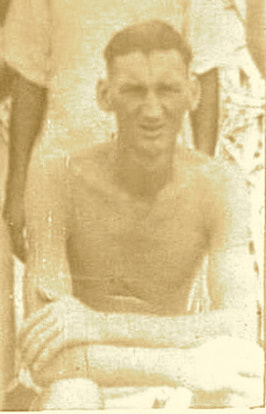

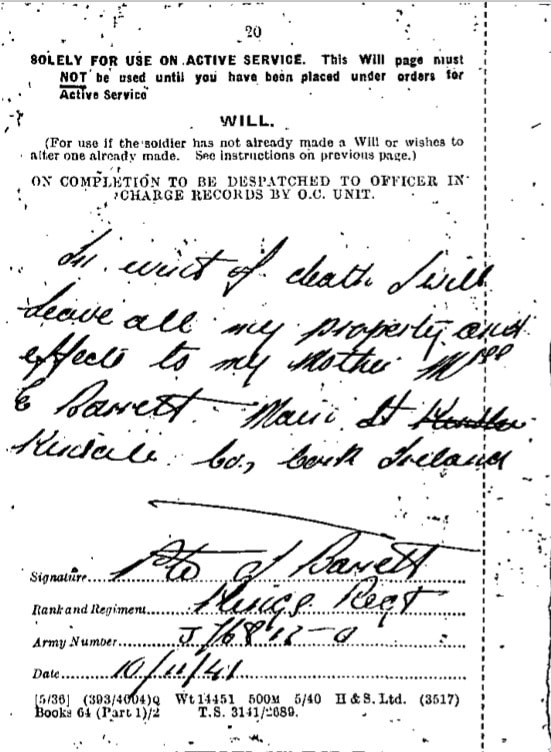

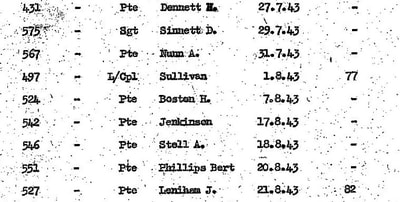

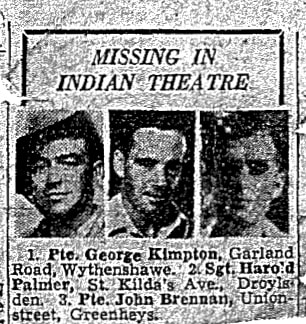

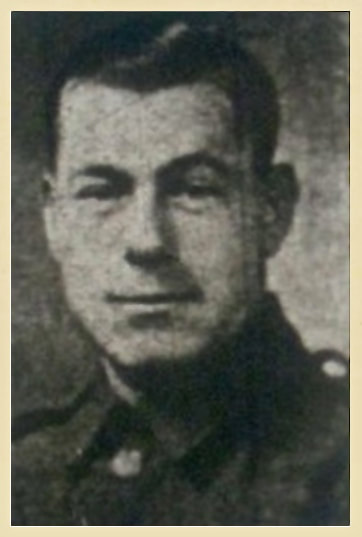

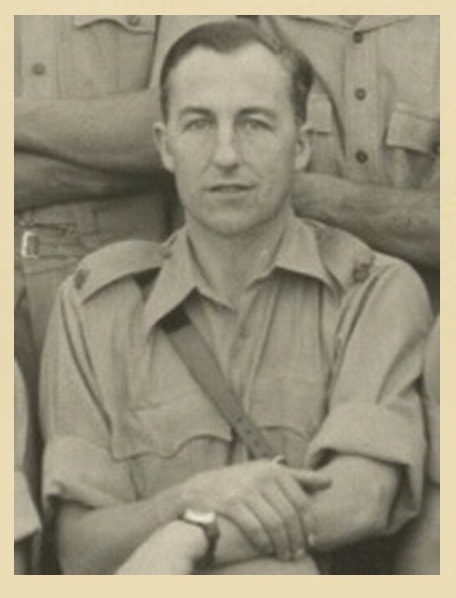

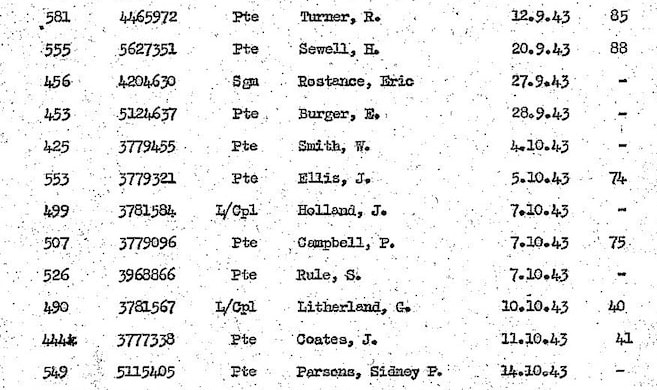

George Atkinson.