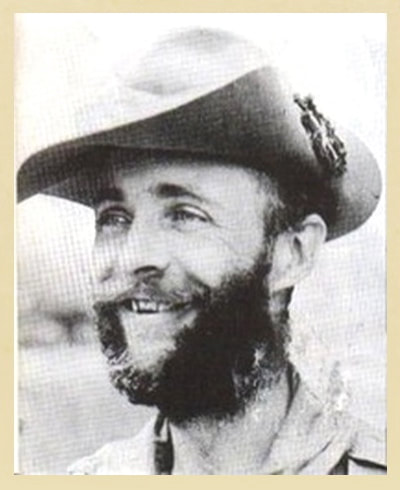

Lt. David William Whitehead

Cap badge of the Royal Engineers.

Cap badge of the Royal Engineers.

David William Whitehead was born on the 5th February 1915 and was the son of Emma Whitehead from Leeds in Yorkshire. Before the war he worked as a Civil Engineer and had served with the Commandos during raids in North West Europe, before being posted overseas to India. He was posted to 142 Commando, joining the unit at their Saugor training centre on the 30th November 1942.

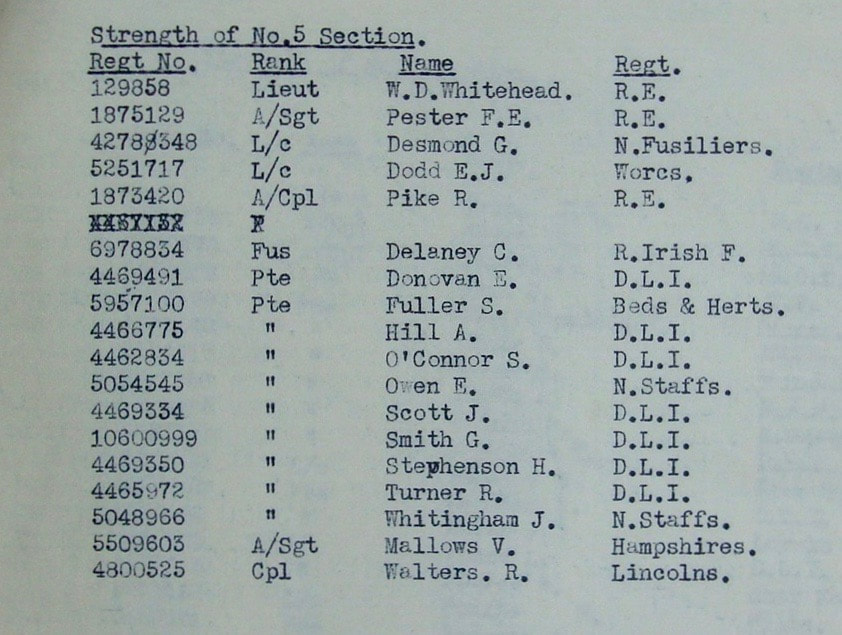

Lieutenant 129858 D.W. Whitehead, Royal Engineers was allocated to No. 5 Column, commanded by Major Bernard Fergusson after previously working with Indian Engineers at Lahore and assumed command of the column's Commando Platoon. Fergusson remembered meeting Whitehead for the first time in his book, Beyond the Chindwin:

We were short of officers in those early days and I had reason to sack my Sapper Officer. John Kerr took control of this platoon for me until the arrival of David Whitehead, a small and bespectacled Sapper from Yorkshire. He came over to me as Technical Sapper and had much excitement already in the war, having done something mysterious in Holland and the commando raids on Lofoten and Spitzbergen.

Lt. Whitehead was ably supported in his role by his Sapper Sergeant, Frank Pester and several other experienced commandos that comprised the Commando Platoon for No. 5 Column. In January 1943, 77th Brigade began their journey into Burma. The majority of Northern Group crossed the Chindwin River on the 15/16th February at a place called Tonhe. Several of the Chindit columns bumped up against each other at this time and traffic at the river became very congested. To alleviate the pressure at Tonhe, Bernard Fergusson and No. 5 Column decided to move slightly north and cross at a place called Hwematte. David Whitehead and his men were tasked with organising a power rope to be strung across the 400 yard river. Several of the column's most competent swimmers, including Sgt. Pester and Pte. Edgar Berger assisted in getting the power-rope across and both men had their work cut out during this time, when the rope became entangled in the reeds at the bottom of the river and a succession of long dives were needed to free it.

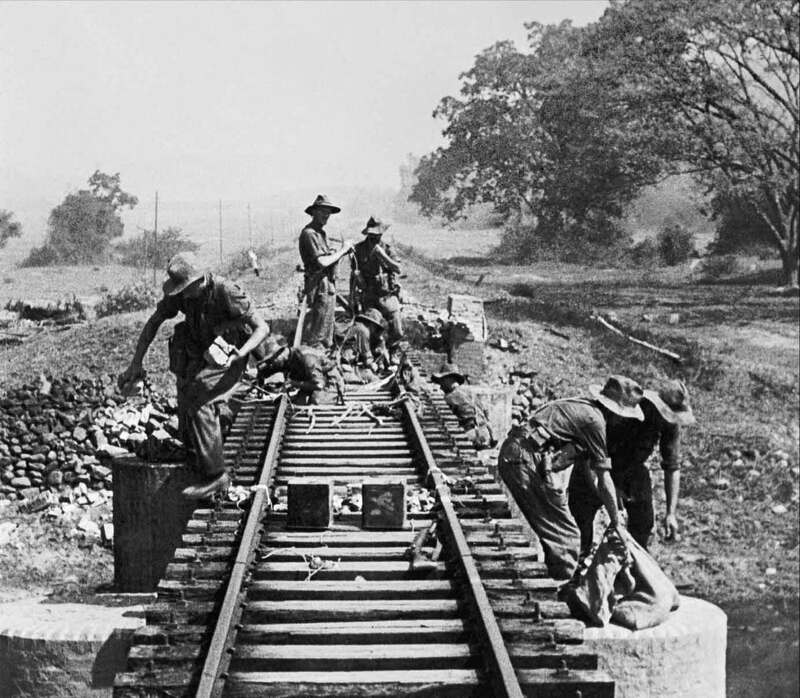

David Whitehead's main task on Operation Longcloth was to organise the demolition of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway line close to the village of Bonchaung. Once again from the book, Beyond the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson recalled:

As time went on, I became more and more anxious to hurry to Bonchaung, and so I told Gerry (Roberts) to come on with men and animals as fast as he could, while I pushed on ahead with Peter Dorans. We got there just after five o'clock on the 6th March, to find everybody in position. David Whitehead, Corporal Pike, and various other sappers were sitting on the bridge with their legs swinging, working away like civvies.

I found Duncan Menzies, who told me that Jim Harman (and Sgt. Pester) had had a bad time in the jungle, and had turned up at Bonchaung half an hour before, having got hopelessly bushed: he had now set off down the railway line towards the gorge. David hoped to have the bridge ready for blowing at half-past eight or nine; he had already laid a "hasty" demolition, which we could blow if interrupted. Until he was ready there was nothing whatever to be done, bar have a cup of tea and I had several. Duncan had everybody ready to move at nine, mules loaded and all. David gave us five minutes warning, and told us that the big bang would be preceded by a little bang. The little bang duly went off, and there was a short delay; then ……..

The flash illumined the whole hillside. It showed the men standing tense and waiting, the muleteers with a good grip of their mules; and the brown of the path and the green of the trees preternaturally vivid. Then came the bang. The mules plunged and kicked, the hills for miles around rolled the noise of it about their hollows and flung it to their neighbours. Mike Calvert and John Fraser heard it away in their distant bivouacs; and all of us hoped that John Kerr and his little group of abandoned men, whose sacrifice at Kyaik-in had helped to make it possible, heard it also, and knew that we had accomplished that which we had come so far to do. Four miles farther on we met Alec MacDonald's guides; and just as we were going into bivouac we heard another great explosion, and knew that Jim Harman had blown the gorge.

In the book, Wingate's Phantom Army, by Wilfred Burchett, there is another more personally attributed account of the bridge-blowing at Bonchaung:

As the various groups from 5 Column shook hands and separated, the demolition boys lovingly checked over their mysterious gadgets and equipment. 'By God she's a real beauty lads,' cried Lt. Whitehead. His eyes were shining with unholy terror as he contemplated the 250 feet steel structure. Within a few minutes his boys had their boxes down from their mules and were crawling about the girders. Hefty concrete buttresses lifted the bridge one hundred feet above the dried up stream bed and supported a one hundred foot span at each end and a one hundred and fifty footer in the middle. They worked hard, they hammered and drilled and laid the latest and most powerful plastic explosive about the bridge.

Then suddenly Whitehead walked slowly away from the scene and gave the order to let her rip. Denny Sharp produced a camera and took a shot just as the last sapper crawled out from amongst the ironworks. Major Fergusson took a firm hold of his monocle and the men placed their fingers into their ears. The first bang was rather dull and muffled, but then came a searing flash and an ear-splitting explosion which reverberated all around the surrounding valley. A large girder lifted off its buttress and forty feet of bridge leapt up into the air and came thumping down into the sandy bed below. For a few minutes Whitehead, trying manfully to conceal the joy in his eyes, crawled around the debris and checked on his handy work.

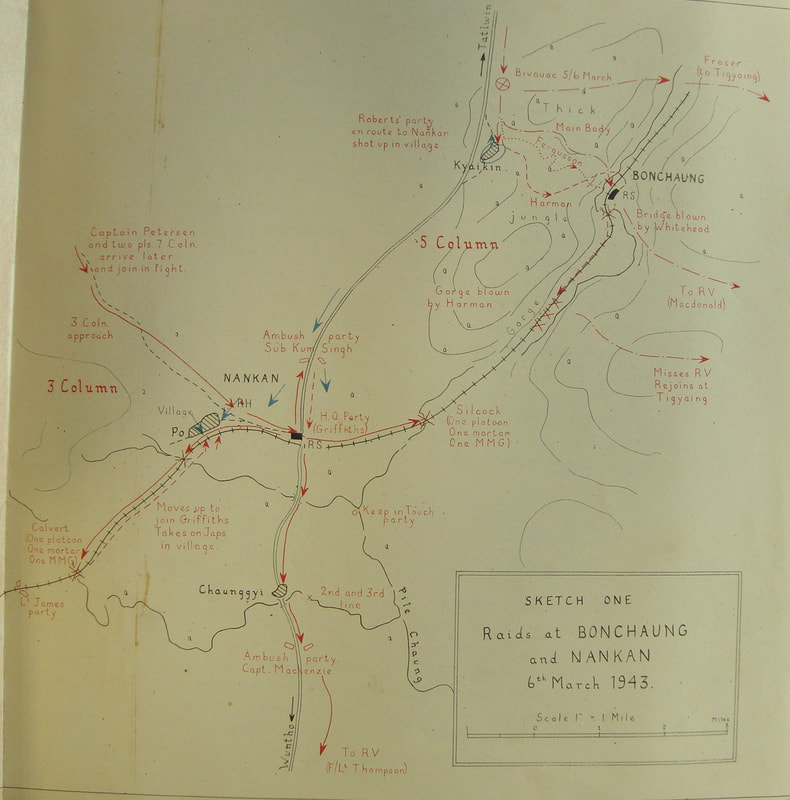

Seen below is a sketch map of the area around Bonchaung and Nankan villages, the scene of the major demolitions on Operation Longcloth. Also shown is a contemporary photograph of the bridge at Bonchaung before 5 Column's intervention in 1943 and an image of the same bridge in 2019. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Lieutenant 129858 D.W. Whitehead, Royal Engineers was allocated to No. 5 Column, commanded by Major Bernard Fergusson after previously working with Indian Engineers at Lahore and assumed command of the column's Commando Platoon. Fergusson remembered meeting Whitehead for the first time in his book, Beyond the Chindwin:

We were short of officers in those early days and I had reason to sack my Sapper Officer. John Kerr took control of this platoon for me until the arrival of David Whitehead, a small and bespectacled Sapper from Yorkshire. He came over to me as Technical Sapper and had much excitement already in the war, having done something mysterious in Holland and the commando raids on Lofoten and Spitzbergen.

Lt. Whitehead was ably supported in his role by his Sapper Sergeant, Frank Pester and several other experienced commandos that comprised the Commando Platoon for No. 5 Column. In January 1943, 77th Brigade began their journey into Burma. The majority of Northern Group crossed the Chindwin River on the 15/16th February at a place called Tonhe. Several of the Chindit columns bumped up against each other at this time and traffic at the river became very congested. To alleviate the pressure at Tonhe, Bernard Fergusson and No. 5 Column decided to move slightly north and cross at a place called Hwematte. David Whitehead and his men were tasked with organising a power rope to be strung across the 400 yard river. Several of the column's most competent swimmers, including Sgt. Pester and Pte. Edgar Berger assisted in getting the power-rope across and both men had their work cut out during this time, when the rope became entangled in the reeds at the bottom of the river and a succession of long dives were needed to free it.

David Whitehead's main task on Operation Longcloth was to organise the demolition of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway line close to the village of Bonchaung. Once again from the book, Beyond the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson recalled:

As time went on, I became more and more anxious to hurry to Bonchaung, and so I told Gerry (Roberts) to come on with men and animals as fast as he could, while I pushed on ahead with Peter Dorans. We got there just after five o'clock on the 6th March, to find everybody in position. David Whitehead, Corporal Pike, and various other sappers were sitting on the bridge with their legs swinging, working away like civvies.

I found Duncan Menzies, who told me that Jim Harman (and Sgt. Pester) had had a bad time in the jungle, and had turned up at Bonchaung half an hour before, having got hopelessly bushed: he had now set off down the railway line towards the gorge. David hoped to have the bridge ready for blowing at half-past eight or nine; he had already laid a "hasty" demolition, which we could blow if interrupted. Until he was ready there was nothing whatever to be done, bar have a cup of tea and I had several. Duncan had everybody ready to move at nine, mules loaded and all. David gave us five minutes warning, and told us that the big bang would be preceded by a little bang. The little bang duly went off, and there was a short delay; then ……..

The flash illumined the whole hillside. It showed the men standing tense and waiting, the muleteers with a good grip of their mules; and the brown of the path and the green of the trees preternaturally vivid. Then came the bang. The mules plunged and kicked, the hills for miles around rolled the noise of it about their hollows and flung it to their neighbours. Mike Calvert and John Fraser heard it away in their distant bivouacs; and all of us hoped that John Kerr and his little group of abandoned men, whose sacrifice at Kyaik-in had helped to make it possible, heard it also, and knew that we had accomplished that which we had come so far to do. Four miles farther on we met Alec MacDonald's guides; and just as we were going into bivouac we heard another great explosion, and knew that Jim Harman had blown the gorge.

In the book, Wingate's Phantom Army, by Wilfred Burchett, there is another more personally attributed account of the bridge-blowing at Bonchaung:

As the various groups from 5 Column shook hands and separated, the demolition boys lovingly checked over their mysterious gadgets and equipment. 'By God she's a real beauty lads,' cried Lt. Whitehead. His eyes were shining with unholy terror as he contemplated the 250 feet steel structure. Within a few minutes his boys had their boxes down from their mules and were crawling about the girders. Hefty concrete buttresses lifted the bridge one hundred feet above the dried up stream bed and supported a one hundred foot span at each end and a one hundred and fifty footer in the middle. They worked hard, they hammered and drilled and laid the latest and most powerful plastic explosive about the bridge.

Then suddenly Whitehead walked slowly away from the scene and gave the order to let her rip. Denny Sharp produced a camera and took a shot just as the last sapper crawled out from amongst the ironworks. Major Fergusson took a firm hold of his monocle and the men placed their fingers into their ears. The first bang was rather dull and muffled, but then came a searing flash and an ear-splitting explosion which reverberated all around the surrounding valley. A large girder lifted off its buttress and forty feet of bridge leapt up into the air and came thumping down into the sandy bed below. For a few minutes Whitehead, trying manfully to conceal the joy in his eyes, crawled around the debris and checked on his handy work.

Seen below is a sketch map of the area around Bonchaung and Nankan villages, the scene of the major demolitions on Operation Longcloth. Also shown is a contemporary photograph of the bridge at Bonchaung before 5 Column's intervention in 1943 and an image of the same bridge in 2019. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

No. 5 Column commander, Bernard Fergusson gave a summary of David Whitehead's work at Bonchaung in his book, Beyond the Chindwin:

David had done a good job on the bridge: of three spans, he had blown one clean off its piers onto the dry stream bed sixty feet below; another longer one, perhaps 100 feet, he had dislodged so that one end rested in the bed, while thanks to a skilful twisting charge, the other he had warped like a corkscrew. A good portion of the piers had also been blown away. We were hopeful that the damage would keep the railway line out of action for many months.

Sadly, this did not happen. From another of Fergusson's books, Return to Burma, written in 1961:

As for Bonchaung, we had always hoped that the Japanese would be unable to repair the bridge before the monsoon, but the RAF reported trains running back over this section by the beginning of May. Poor David Whitehead had the mortification of travelling over the bridge as a prisoner of war towards the end of April; he was lying on the floor of a steel cattle truck with seven bullet wounds in him; the only satisfaction he got was that the train was obliged to cross the bridge dead slow.

Fergusson's second quote of course gives the game away, informing the reader of Lt. Whitehead's eventual fate on Operation Longcloth. The column had moved on quickly from Bonchaung and crossed the Irrawaddy River to join the rest of the Chindit Brigade in the jungle condensed by the Irrawaddy to the west and north and the fast-flowing Shweli River to the east. The Brigade suffered badly during the two weeks spent in this area of Northern Burma. On the 30th March 1943, 5 Column had just withdrawn from a bruising action with the Japanese at a village called Hintha. Immediately after this engagement, the column was split by an enemy ambush on the track some two miles outside of Hintha. It was at this juncture that Lt. Whitehead was reported as missing in action and was never seen again by his commanding officer.

To read more about the engagement at Hintha, please click on the following link: Pte. John Henry Cobb

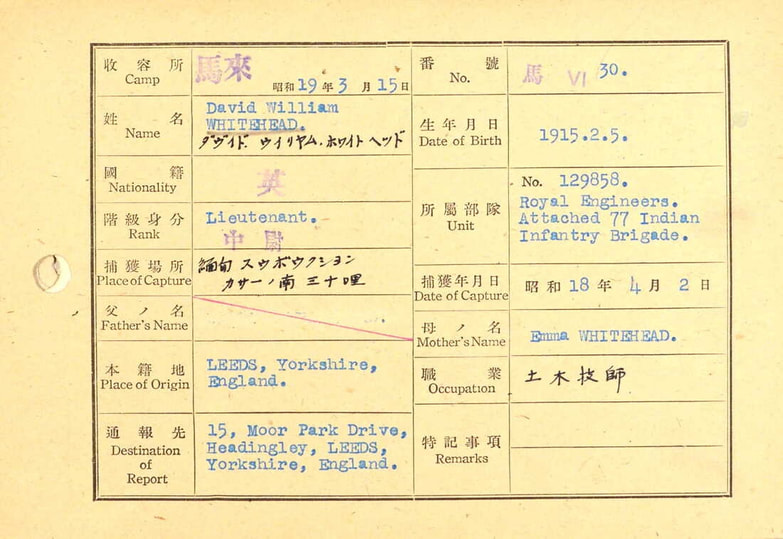

According to surviving POW records, David Whitehead was captured on the 2nd April 1943, close to the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. He was reported as having been wounded in several places on capture, but how he came to receive these injuries is unclear. In the first instance David was taken to the POW concentration camp at Maymyo where he met up with several of his comrades from No. 5 Column. After about two weeks at Maymyo, where the Japanese had collected together over 230 Chindits, plans were made to send the prisoners down to the capital city, Rangoon. To learn more about the POW Camp at Maymyo, please click on the following link: More Cemeteries and Memorials

David had done a good job on the bridge: of three spans, he had blown one clean off its piers onto the dry stream bed sixty feet below; another longer one, perhaps 100 feet, he had dislodged so that one end rested in the bed, while thanks to a skilful twisting charge, the other he had warped like a corkscrew. A good portion of the piers had also been blown away. We were hopeful that the damage would keep the railway line out of action for many months.

Sadly, this did not happen. From another of Fergusson's books, Return to Burma, written in 1961:

As for Bonchaung, we had always hoped that the Japanese would be unable to repair the bridge before the monsoon, but the RAF reported trains running back over this section by the beginning of May. Poor David Whitehead had the mortification of travelling over the bridge as a prisoner of war towards the end of April; he was lying on the floor of a steel cattle truck with seven bullet wounds in him; the only satisfaction he got was that the train was obliged to cross the bridge dead slow.

Fergusson's second quote of course gives the game away, informing the reader of Lt. Whitehead's eventual fate on Operation Longcloth. The column had moved on quickly from Bonchaung and crossed the Irrawaddy River to join the rest of the Chindit Brigade in the jungle condensed by the Irrawaddy to the west and north and the fast-flowing Shweli River to the east. The Brigade suffered badly during the two weeks spent in this area of Northern Burma. On the 30th March 1943, 5 Column had just withdrawn from a bruising action with the Japanese at a village called Hintha. Immediately after this engagement, the column was split by an enemy ambush on the track some two miles outside of Hintha. It was at this juncture that Lt. Whitehead was reported as missing in action and was never seen again by his commanding officer.

To read more about the engagement at Hintha, please click on the following link: Pte. John Henry Cobb

According to surviving POW records, David Whitehead was captured on the 2nd April 1943, close to the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. He was reported as having been wounded in several places on capture, but how he came to receive these injuries is unclear. In the first instance David was taken to the POW concentration camp at Maymyo where he met up with several of his comrades from No. 5 Column. After about two weeks at Maymyo, where the Japanese had collected together over 230 Chindits, plans were made to send the prisoners down to the capital city, Rangoon. To learn more about the POW Camp at Maymyo, please click on the following link: More Cemeteries and Memorials

Lt. Whitehead and the other Chindit officers captured during Operation Longcloth spent their first few weeks inside Rangoon Jail locked up in solitary confinement. After this they joined the rest of their men in Block 6 of the prison, sharing the upstairs cell rooms with around 30 men in each room. David was given the POW 30 at Rangoon and had to recite this number in Japanese at the twice daily tenkos, or roll calls. His wounds from the expedition were eventually tended by Major Raymond Ramsay, the senior medic in Block 6 and another officer captured during the first Wingate operation.

Lt. Philip Stibbe, was another officer from No. 5 Column to be taken prisoner. In his own book, Return via Rangoon, Stibbe recalled being reunited with some of his officer comrades when he finally arrived at Rangoon Jail in early June 1943:

We were herded into the jail at dusk and to my astonishment I found myself shaking hands with David Whitehead. He was looking extraordinarily well although he had collected an amazing number of bullets in odd parts of his body; apparently all his wounds had healed perfectly. David's survival was scarcely less remarkable than that of his spectacles. The frames of these were always getting broken; if the Japanese were going to beat you up, they did not wait while you removed your glasses. I can still see David's stocky figure, his head cocked to one side, his eyes twinkling through lenses held together with innumerable pieces of string, cotton and wire.

Rangoon Jail had been a civil prison before the war and should have been condemned long before it was used by the Japanese. A great circle of 40 ft walls, with prison blocks radiating out from the central courtyard like the spokes of a wheel. The blocks were occupied as follows:

Block 1 - Downstairs, Japanese Guards. Upstairs, Chinese prisoners.

Block 2 & 7 - Indian and Gurkha prisoners.

Block 3 & 6 - British, American, Australian, South African and New Zealand prisoners.

Block 5 - Solitary confinement cells.

Block 8 - American and British Air crew who had been kept in solitary confinement for weeks in revenge for the first Allied bombings of Tokyo.

Each Block had two storeys and all except Block 5 had four rooms on each storey of about 30 ft x 18 ft square. Downstairs had a concrete floor and some rather uncomfortable beds. Upstairs all floors were wooden with no beds unless you were very lucky. Each Block had a water trough for washing supplied by the mains, a lean-to cook house and a very primitive latrine, known as the one-holer.

To read more about the Chindit prisoners of war and their time inside Rangoon Jail, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

As the war began to turn against the Japanese in Rangoon, in April 1945 they decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 men were classified as fit to march and on the 24th April were marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and ill comrades. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, the marchers were north of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge when they ran into the 14th Army. The Japanese Commandant released them at a village called Waw telling them they were free men and then disappeared with the rest of his guards. The now liberated prisoners were situated in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. They chose to lie low and that night managed to contact some troops from the West Yorkshire Regiment and were taken to the safety of Allied held territory.

David Whitehead and the majority of those men liberated on the Pegu Road were flown back to India aboard American Dakota aircraft. After several weeks in hospital, where they were treated for their ailments and brought back to a decent level of health, the men were then sent to the hill stations of Northern India for rest and recuperation. By July 1945, all former prisoners of war were being processed for repatriation to the United Kingdom, it is not known whether Lt. Whitehead returned to the UK immediately after liberation, or rejoined his former unit in India, the Royal Engineers.

Lt. Philip Stibbe, was another officer from No. 5 Column to be taken prisoner. In his own book, Return via Rangoon, Stibbe recalled being reunited with some of his officer comrades when he finally arrived at Rangoon Jail in early June 1943:

We were herded into the jail at dusk and to my astonishment I found myself shaking hands with David Whitehead. He was looking extraordinarily well although he had collected an amazing number of bullets in odd parts of his body; apparently all his wounds had healed perfectly. David's survival was scarcely less remarkable than that of his spectacles. The frames of these were always getting broken; if the Japanese were going to beat you up, they did not wait while you removed your glasses. I can still see David's stocky figure, his head cocked to one side, his eyes twinkling through lenses held together with innumerable pieces of string, cotton and wire.

Rangoon Jail had been a civil prison before the war and should have been condemned long before it was used by the Japanese. A great circle of 40 ft walls, with prison blocks radiating out from the central courtyard like the spokes of a wheel. The blocks were occupied as follows:

Block 1 - Downstairs, Japanese Guards. Upstairs, Chinese prisoners.

Block 2 & 7 - Indian and Gurkha prisoners.

Block 3 & 6 - British, American, Australian, South African and New Zealand prisoners.

Block 5 - Solitary confinement cells.

Block 8 - American and British Air crew who had been kept in solitary confinement for weeks in revenge for the first Allied bombings of Tokyo.

Each Block had two storeys and all except Block 5 had four rooms on each storey of about 30 ft x 18 ft square. Downstairs had a concrete floor and some rather uncomfortable beds. Upstairs all floors were wooden with no beds unless you were very lucky. Each Block had a water trough for washing supplied by the mains, a lean-to cook house and a very primitive latrine, known as the one-holer.

To read more about the Chindit prisoners of war and their time inside Rangoon Jail, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

As the war began to turn against the Japanese in Rangoon, in April 1945 they decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 men were classified as fit to march and on the 24th April were marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and ill comrades. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, the marchers were north of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge when they ran into the 14th Army. The Japanese Commandant released them at a village called Waw telling them they were free men and then disappeared with the rest of his guards. The now liberated prisoners were situated in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. They chose to lie low and that night managed to contact some troops from the West Yorkshire Regiment and were taken to the safety of Allied held territory.

David Whitehead and the majority of those men liberated on the Pegu Road were flown back to India aboard American Dakota aircraft. After several weeks in hospital, where they were treated for their ailments and brought back to a decent level of health, the men were then sent to the hill stations of Northern India for rest and recuperation. By July 1945, all former prisoners of war were being processed for repatriation to the United Kingdom, it is not known whether Lt. Whitehead returned to the UK immediately after liberation, or rejoined his former unit in India, the Royal Engineers.

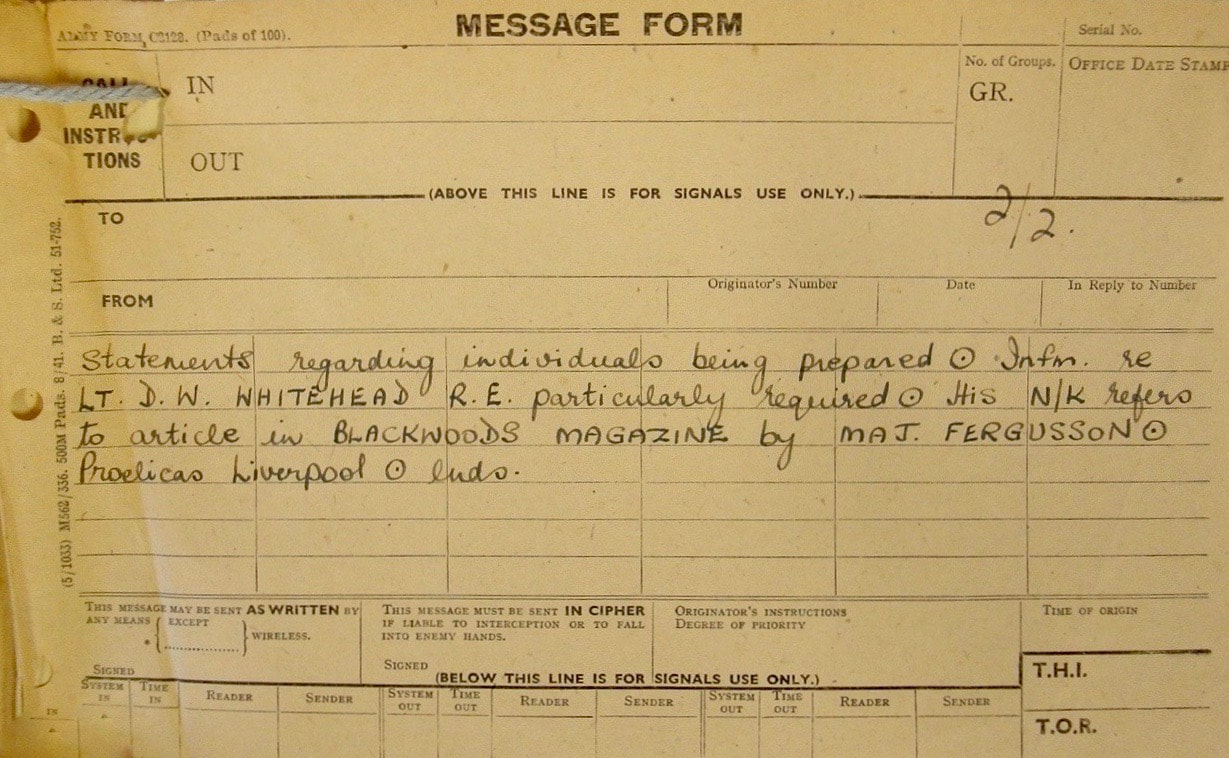

In August 2017, I was delighted to receive an email contact from the Imperial War Museum. They had acquired a one-page letter written by Bernard Fergusson in September 1943, to the family of a Chindit casualty from Operation Longcloth. From the information contained within Fergusson's letter, it became clear to me that the soldier in question was David Whitehead. With permission I can now offer up this transcription:

Dear Miss Whitehead, (15th September 1943).

I cannot tell you how sorry I am at this prolonged anxiety to which you and David's mother have been subjected. I have myself been trying to discover your address, but somehow there was no record of it in India nor that of another of the officers I lost (this year). You ask me to be frank, and indeed I feel obliged to tell you what I know, though it is very little.

On March 28th, I was trying to force my way through a small village called Hintha, located about 30 miles east of the Irrawaddy. The action is described in the article which you have seen, it was the occasion when I myself was wounded and forced to split the column. I did not see David at all during the show, but his immediate command, gave him some job to do at the tail of the column. From that day until just last week, I could find nobody who remembered seeing him. Last week, however, I saw Sergeant-Major Cairns, who with a few men had reached China two months after I myself had reached Assam.

He and his men tell me that David was with them for ten minutes after they left the village, and that he went back to help a wounded man lagging along behind. That was the last they saw of him. Now God forbid that I should raise false hopes, but he may be a prisoner and the Japanese so far as we know have not been treating our men too badly. My Adjutant, Duncan Menzies was only shot because he was being rescued, several men escaped and said that they we well treated. Duncan himself said he had been fed and kindly treated up until the rescue attempt came in.

Much of the success of the expedition was due to David. It was he who blew the Bonchaung Bridge, the one really spectacular and effective achievement of the expedition. It was he in his quiet and unassuming way, that jollied his men along in bad times as well as good. I have lost a very dear friend in him and I had got to know him well enough to know the magnitude of your loss. It was just like him to go back to succour the wounded. Before Bonchaung Bridge went up, he told me that he had made arrangements for it to go off even if we had been interrupted, only that this would mean his own death in doing so.

A more gallant selfless officer never existed and I don't know what comfort I can give your mother or yourself greater than this; that David, shy and unassuming as he was had contributed to the winning of the war to a far greater degree in all his hazardous expeditions than perhaps any other officer of his rank. If he is dead, then he died in a most glorious venture; but if you have the courage to hope, then I believe that this hope may not be misplaced. As you can imagine, I pray most consistently for all those fellows that we have not yet heard of and David is among the two or three most precious to me. So much of the credit we got (after the operation) is due to him, and I can hardly bear that he should not be here to share it. There is nothing more to say except to hope that your pride in him may be greater than your anxiety and sorrow, and to offer as much sympathy as I can.

Yours very sincerely, Bernard Fergusson.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. Sadly, according to information found on line, David Whitehead passed away in October 1990 with his death being registered at Hull in Humberside.

Dear Miss Whitehead, (15th September 1943).

I cannot tell you how sorry I am at this prolonged anxiety to which you and David's mother have been subjected. I have myself been trying to discover your address, but somehow there was no record of it in India nor that of another of the officers I lost (this year). You ask me to be frank, and indeed I feel obliged to tell you what I know, though it is very little.

On March 28th, I was trying to force my way through a small village called Hintha, located about 30 miles east of the Irrawaddy. The action is described in the article which you have seen, it was the occasion when I myself was wounded and forced to split the column. I did not see David at all during the show, but his immediate command, gave him some job to do at the tail of the column. From that day until just last week, I could find nobody who remembered seeing him. Last week, however, I saw Sergeant-Major Cairns, who with a few men had reached China two months after I myself had reached Assam.

He and his men tell me that David was with them for ten minutes after they left the village, and that he went back to help a wounded man lagging along behind. That was the last they saw of him. Now God forbid that I should raise false hopes, but he may be a prisoner and the Japanese so far as we know have not been treating our men too badly. My Adjutant, Duncan Menzies was only shot because he was being rescued, several men escaped and said that they we well treated. Duncan himself said he had been fed and kindly treated up until the rescue attempt came in.

Much of the success of the expedition was due to David. It was he who blew the Bonchaung Bridge, the one really spectacular and effective achievement of the expedition. It was he in his quiet and unassuming way, that jollied his men along in bad times as well as good. I have lost a very dear friend in him and I had got to know him well enough to know the magnitude of your loss. It was just like him to go back to succour the wounded. Before Bonchaung Bridge went up, he told me that he had made arrangements for it to go off even if we had been interrupted, only that this would mean his own death in doing so.

A more gallant selfless officer never existed and I don't know what comfort I can give your mother or yourself greater than this; that David, shy and unassuming as he was had contributed to the winning of the war to a far greater degree in all his hazardous expeditions than perhaps any other officer of his rank. If he is dead, then he died in a most glorious venture; but if you have the courage to hope, then I believe that this hope may not be misplaced. As you can imagine, I pray most consistently for all those fellows that we have not yet heard of and David is among the two or three most precious to me. So much of the credit we got (after the operation) is due to him, and I can hardly bear that he should not be here to share it. There is nothing more to say except to hope that your pride in him may be greater than your anxiety and sorrow, and to offer as much sympathy as I can.

Yours very sincerely, Bernard Fergusson.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. Sadly, according to information found on line, David Whitehead passed away in October 1990 with his death being registered at Hull in Humberside.

Update 20/10/2019.

I was extremely pleased to receive the following contact in regards to David Whitehead and his time after WW2:

Dear Steve, I loved reading your website page about David Whitehead. I knew him well as a child as he worked with my father in Saudi Arabia as an engineer, where both he and us shared a cabin at the beach. He spent most days tinkering with his boats, which ironically I never saw him sail. I remember him tapping a biscuit on the table top one time in order to get the weevils out and saying there was a time that he and his POW comrades would have been grateful for them. What a lovely understated man he was.

Regards, Claire Munro.

Shortly after receiving Claire's contact I replied:

Dear Claire,

Thank you for your welcome email contact via my website. I was extremely pleased to receive your memories of David Whitehead. From the information I have been able to find out about him, he clearly was a very kind and special man. I would very much like to hear any other memories you might have about him and wondered if you might have a photograph of David at all as it would be fabulous to add this to the website story.

Many thanks again and best wishes. Steve.

I was extremely pleased to receive the following contact in regards to David Whitehead and his time after WW2:

Dear Steve, I loved reading your website page about David Whitehead. I knew him well as a child as he worked with my father in Saudi Arabia as an engineer, where both he and us shared a cabin at the beach. He spent most days tinkering with his boats, which ironically I never saw him sail. I remember him tapping a biscuit on the table top one time in order to get the weevils out and saying there was a time that he and his POW comrades would have been grateful for them. What a lovely understated man he was.

Regards, Claire Munro.

Shortly after receiving Claire's contact I replied:

Dear Claire,

Thank you for your welcome email contact via my website. I was extremely pleased to receive your memories of David Whitehead. From the information I have been able to find out about him, he clearly was a very kind and special man. I would very much like to hear any other memories you might have about him and wondered if you might have a photograph of David at all as it would be fabulous to add this to the website story.

Many thanks again and best wishes. Steve.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, February 2019.