Lieutenant Richard Allen Wilding

Captain R.A. Wilding.

Captain R.A. Wilding.

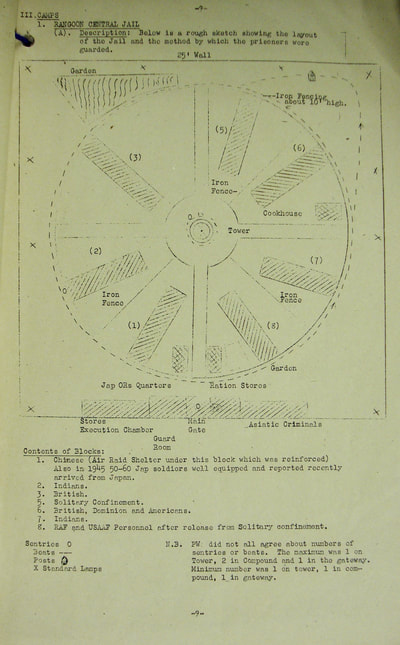

Richard Allen Wilding was the son of Richard and Theresa Mary Wilding and was born on the 9th of December 1910 at Blackburn in Lancashire. He was educated at St. Edmunds College in Ware, Hertfordshire. In February 1934 he was admitted to the Roll of Solicitors and worked in this field for a number of years leading up to the start of WW2. In March 1939, he joined the 7th Manchester Regiment (Territorial Army) and in August that same year received his commission as a 2nd Lieutenant.

In November 1939, he was attached to 199th Brigade HQ (based at home in the UK) and was appointed Brigade Transport Officer, before being promoted to Temporary Captain in June 1940. He left 199th Brigade in March 1942 and two months later was sent overseas in an officers draft for Indian Army service. In September 1942, he was attached to the 3rd Queen Alexandra's Own Gurkha Rifles, but only remained with this unit for 8 weeks, before being posted across to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade (Chindits) as Brigade Cipher Officer in November.

According Wilding's own memoir, he was rather disappointed to be given the position of Cipher Officer on Operation Longcloth, hoping instead for a more offensive role within the Brigade. He nevertheless impressed in the performance of his duties. In Wingate's debrief notes written after the first expedition, he describes Lt. Wilding thus:

One time pads were a very satisfactory cipher on operations in 1943. Captain Wilding, my cipher officer was very well chosen. He was of the combatant type, as officers for Long Range Penetration must be, but possessed at the same time an indispensable assiduity and thoroughness in his work.

Lt. Wilding, from this point on nicknamed 'Willy' by his Chindit comrades, arrived at the Atta training camp in the Central Provinces after a long and tiresome train journey. Here he was met by the Brigade-Major and shown to his quarters. He remembered:

I found a camp fire in the middle of some jungle with some rather scruffy officers sitting around it. Everyone was most welcoming and I was handed a soft drink. At bedtime I enquired where it was I was to sleep, one of the officers pointed to a large bush and said, "Under that if you like." I took on the role of Cipher Officer, which initially I found rather laborious. On our worst day my Sergeant and I ciphered or deciphered over 2,000 groups. A fair day's work sitting in an office, but a bit much when you are working with your back against a fallen tree tormented by ants, lice, ticks, and other assorted insects.

Wilding soon struck up friendships with a number of officers from Brigade Head Quarters, including Squadron-Leader Longmore of the RAF, Animal Transport Officer, Lt. Molesworth, Intelligence Officer, Graham Hosegood and Signals Officer, Kenneth Spurlock. On the 9th December, the Brigade moved to Jhansi where it remained for the Christmas period. Lt. Wilding recalled in his memoir that the officer's mess enjoyed peacock for Christmas dinner instead of the more traditional turkey and that he and Captain Blackburn from the King's Regiment attended Midnight Mass in the local Catholic Church.

More recruits to Brigade HQ appeared at Jhansi, including Senior Medical Officer, Raymond Ramsay and Lt. L.W. Rose of the Gurkha Rifles. After travelling by train, paddle-steamer and motor transport, the Brigade arrived at Imphal for its finally stop-over before crossing the Chindwin River and penetrating behind Japanese lines. Brigade Head Quarters crossed the Chindwin on the 15th February 1943. Lt. Wilding remembered that amongst his party were some newspaper journalists, who remained with the Chindits for two more days once over the river. He rather amusingly described the river crossing itself as resembling a boat race between Colney Hatch and Bedlam (both well known lunatic asylums from that time), but had got away with it without interference from the enemy and only losing one man drowned.

In November 1939, he was attached to 199th Brigade HQ (based at home in the UK) and was appointed Brigade Transport Officer, before being promoted to Temporary Captain in June 1940. He left 199th Brigade in March 1942 and two months later was sent overseas in an officers draft for Indian Army service. In September 1942, he was attached to the 3rd Queen Alexandra's Own Gurkha Rifles, but only remained with this unit for 8 weeks, before being posted across to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade (Chindits) as Brigade Cipher Officer in November.

According Wilding's own memoir, he was rather disappointed to be given the position of Cipher Officer on Operation Longcloth, hoping instead for a more offensive role within the Brigade. He nevertheless impressed in the performance of his duties. In Wingate's debrief notes written after the first expedition, he describes Lt. Wilding thus:

One time pads were a very satisfactory cipher on operations in 1943. Captain Wilding, my cipher officer was very well chosen. He was of the combatant type, as officers for Long Range Penetration must be, but possessed at the same time an indispensable assiduity and thoroughness in his work.

Lt. Wilding, from this point on nicknamed 'Willy' by his Chindit comrades, arrived at the Atta training camp in the Central Provinces after a long and tiresome train journey. Here he was met by the Brigade-Major and shown to his quarters. He remembered:

I found a camp fire in the middle of some jungle with some rather scruffy officers sitting around it. Everyone was most welcoming and I was handed a soft drink. At bedtime I enquired where it was I was to sleep, one of the officers pointed to a large bush and said, "Under that if you like." I took on the role of Cipher Officer, which initially I found rather laborious. On our worst day my Sergeant and I ciphered or deciphered over 2,000 groups. A fair day's work sitting in an office, but a bit much when you are working with your back against a fallen tree tormented by ants, lice, ticks, and other assorted insects.

Wilding soon struck up friendships with a number of officers from Brigade Head Quarters, including Squadron-Leader Longmore of the RAF, Animal Transport Officer, Lt. Molesworth, Intelligence Officer, Graham Hosegood and Signals Officer, Kenneth Spurlock. On the 9th December, the Brigade moved to Jhansi where it remained for the Christmas period. Lt. Wilding recalled in his memoir that the officer's mess enjoyed peacock for Christmas dinner instead of the more traditional turkey and that he and Captain Blackburn from the King's Regiment attended Midnight Mass in the local Catholic Church.

More recruits to Brigade HQ appeared at Jhansi, including Senior Medical Officer, Raymond Ramsay and Lt. L.W. Rose of the Gurkha Rifles. After travelling by train, paddle-steamer and motor transport, the Brigade arrived at Imphal for its finally stop-over before crossing the Chindwin River and penetrating behind Japanese lines. Brigade Head Quarters crossed the Chindwin on the 15th February 1943. Lt. Wilding remembered that amongst his party were some newspaper journalists, who remained with the Chindits for two more days once over the river. He rather amusingly described the river crossing itself as resembling a boat race between Colney Hatch and Bedlam (both well known lunatic asylums from that time), but had got away with it without interference from the enemy and only losing one man drowned.

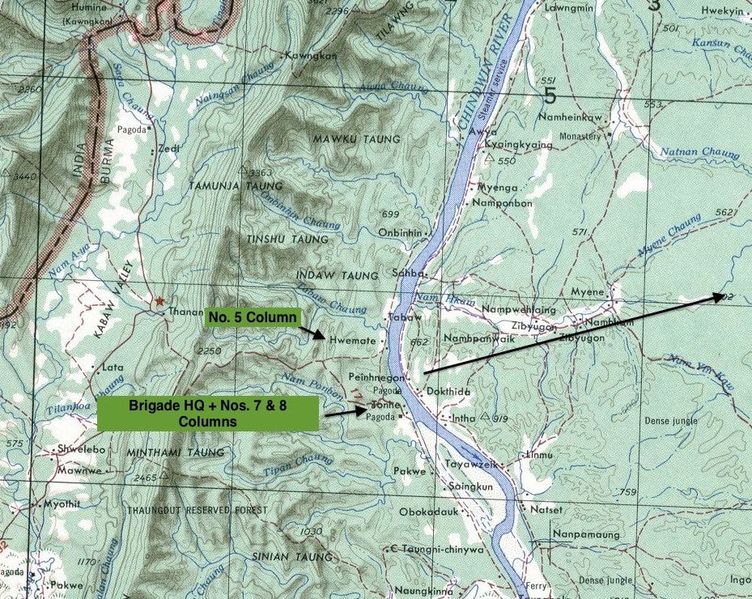

Much to Lt. Wilding's disappointment, Brigade HQ did not see action during operations in 1943. Wingate and his Head Quarters moved through the Burmese jungle shadowed on their flanks by columns 7 & 8 placed as their protectors. He remembered:

During the early weeks behind enemy lines, all we seemed to do was march and march. I had the uncanny knack of falling asleep whilst marching and as my normal gait was quicker than that of the column, I often found myself alongside the Brigadier at the head of column. At first he used to ask me if there was anything wrong, but in the end he simply shouted, "Wake up Wilding." Sleeping on the march is a useful knack, but should not be used too much in enemy country.

After six weeks in the jungle the RAF broke it to us that they could no longer supply us if we went any further east. I gather that while the DC-3s could make it that far, the fighter escorts could not. We were ordered to return to India and we headed back to the Irrawaddy. When we got back to the area around Inywa (29th March 1943) we were fired at from the west bank and it was decided not to force a crossing at this point. With respect and with hindsight this was very much the wrong decision.

Immediately afterwards, columns 7 & 8 were sent away and Brigade HQ was split up into five parties. The map showed that we were east of the Irrawaddy and south of the Shweli River. A boxer would say we were cornered and on the ropes. My party, which I commanded alongside Graham Hosegood, was ordered to go north, cross the Shweli and get back to India that way. At a guess, a journey of about 200 miles.

At first the feeling was marvellous, all on our own with no senior officer breathing down our neck. It took us about a couple of days to reach the bank of the Shweli, but there were no boats to be found. The river here was only about 200 yards wide and I was confident that I and any reasonably competent swimmer could get across. To my horror I found that only eight of my twenty-eight chaps could swim. Problem; do I take the swimmers across and try to get to India or do we stick together as one unit. It was decided that we should stick together. I think it was the right decision, but of those who could have swum the Shweli, only three (including myself) survived captivity. Not a very nice thought on a sleepless night even 47 years later.

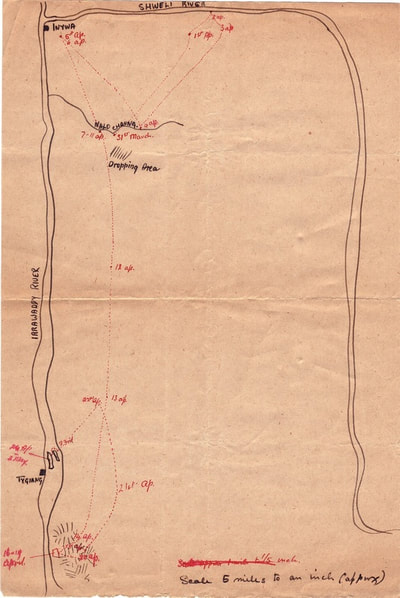

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story, including a sketch map drawn by Willy Wilding showing the area in which his dispersal group meandered in April 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

During the early weeks behind enemy lines, all we seemed to do was march and march. I had the uncanny knack of falling asleep whilst marching and as my normal gait was quicker than that of the column, I often found myself alongside the Brigadier at the head of column. At first he used to ask me if there was anything wrong, but in the end he simply shouted, "Wake up Wilding." Sleeping on the march is a useful knack, but should not be used too much in enemy country.

After six weeks in the jungle the RAF broke it to us that they could no longer supply us if we went any further east. I gather that while the DC-3s could make it that far, the fighter escorts could not. We were ordered to return to India and we headed back to the Irrawaddy. When we got back to the area around Inywa (29th March 1943) we were fired at from the west bank and it was decided not to force a crossing at this point. With respect and with hindsight this was very much the wrong decision.

Immediately afterwards, columns 7 & 8 were sent away and Brigade HQ was split up into five parties. The map showed that we were east of the Irrawaddy and south of the Shweli River. A boxer would say we were cornered and on the ropes. My party, which I commanded alongside Graham Hosegood, was ordered to go north, cross the Shweli and get back to India that way. At a guess, a journey of about 200 miles.

At first the feeling was marvellous, all on our own with no senior officer breathing down our neck. It took us about a couple of days to reach the bank of the Shweli, but there were no boats to be found. The river here was only about 200 yards wide and I was confident that I and any reasonably competent swimmer could get across. To my horror I found that only eight of my twenty-eight chaps could swim. Problem; do I take the swimmers across and try to get to India or do we stick together as one unit. It was decided that we should stick together. I think it was the right decision, but of those who could have swum the Shweli, only three (including myself) survived captivity. Not a very nice thought on a sleepless night even 47 years later.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story, including a sketch map drawn by Willy Wilding showing the area in which his dispersal group meandered in April 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

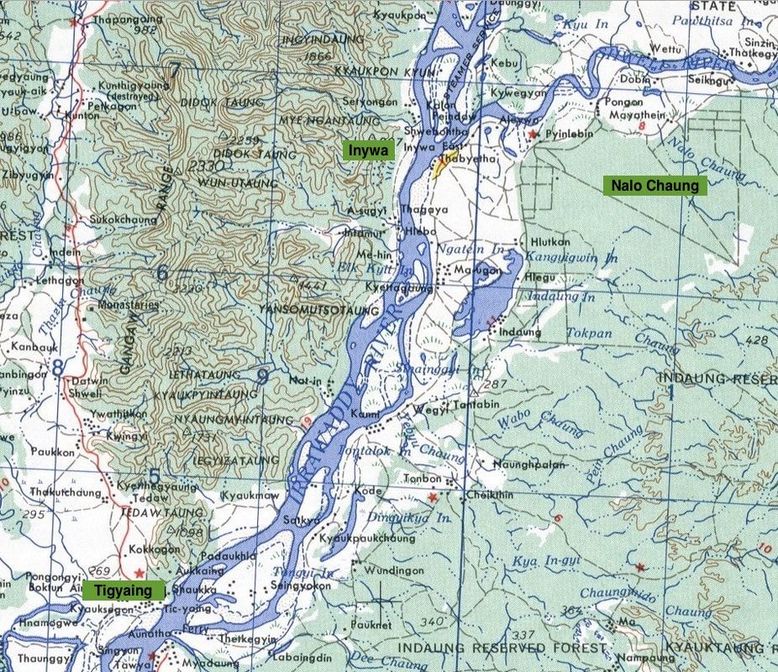

Around the beginning of April 1943, several hundred exhausted and desperate Chindits were searching for a way to cross either the Irrawaddy or Shweli Rivers. Four out of the five dispersal groups from Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters were drifting back and forth along the Irrawaddy's eastern shoreline, in the hope of finding a native boat and a safe crossing point. Very few succeeded in this quest.

Returning to Lt. Wilding's memoir, he recalled this time in the form of a day to day diary:

2nd April: Marched back towards Inywa village, needed water that we knew we could get from a dried up riverbed called the Nalo Chaung. A very nasty march of 10-12 miles.

3rd April: Hoped that the Japs had abandoned Inywa, so decided to try there again today; got within a couple of miles and sent the Burma Riflemen off to make a recce. Waited all day and the next, with insufficient water.

4th April: The Burmese returned late in the day, without one soldier who had been injured and captured. Needed water, so set off again on the 5th for Nalo Chaung, only just making it.

6th April: Rations low and we still have a long way to go. 2/Lt Pat Gordon took a party to the last ration drop in the hope of finding something, came back with 15 days rations per man. This gave us 17 days rations each, but some of the men couldn’t even carry the load. Stayed here for the 7th and 8th, intending to set out on the 9th. Planned to move southeast and make individual rafts, strong enough to carry a rifle, boots and pack and cross the Irrawaddy supported by these.

9th April: A party of men set out to get water. Returned with one man short (Simons), assumed he had got lost and would be taken captive and made to talk. Decided we could afford to wait three days, then put our plan into action. 9th, 10th and 11th April stayed put, eating slightly more than a days rations each day to reduce the load to 10 days.

12th April: Set off and covered 10 miles, found a stream, superior to the muddy pools of the Nalo Chaung. Bivouacked near here and then found we had bivouacked within 50 yards of a track much used by the Japs.

13th April: Early start to get over the road before traffic started moving, marched well clear of the road, lay up to continue our journey by night. Laid an ambush as heard bells that we thought were on the necks of elephants used by the Japs, turned out to be two buffalo out to graze.

14th April: Night marching has not proved very sensible, so marched by day.

15th April: Left thick jungle behind us and headed due west towards Tigyiang where we intended to launch the rafts. Found a good sight on a hill top with a spring and plenty of bamboo to make the rafts.

16th and 17th April: Most made rafts while a small party went to recce a route to the river. Three days rations left, enough to reach the Meza Valley, where we expected to find friendly villagers who would sell us food.

18th April: Recce party returned and said it was practicable to get to river, so raft making continued.

19th and 20th April: Struggled out of the swamp, tried to find a bit of dry land to dry our clothes. Irrawaddy idea abandoned, thought we could go east, cross the Shweli, where it was only a stream, swing north and go into Kachin country, and there sweat out the monsoon. Riflemen Tunnion and Orlando thought that their home villages would put us up for the duration. It was only 80 miles and we thought we could make it.

21st April: There was hardly any food left so first decided to raid a village, where we in fact bought food. In a change of plan, the Headman promised to put us over the Irrawaddy for a considerable price in silver rupees. He and his brother took us to the river at a racing speed; we had no idea where we were. It was night before we finally embarked, paddled around one island and then disembarked, handed over nearly all our money and set out for the hills, only to find a wide stretch of water between us and the hills. It was the main river! We had been betrayed.

22nd - 28th April: The next six days are very confused in my mind, searched the island which was about a mile long and ½ mile wide. Finished the last of the rations on the 23rd, some villagers gave us one meal for a payment. Tried launching one decrepit boat but it sank.

29th April: Found another boat, which floated, so decided a small group would take the first trip and see what could be done, most of them were killed on reaching the other side. Decided to break into small parties and hide in the elephant grass for three days and to rendezvous at the old bivouac at sunset on the 3rd day.

NB. To read more about the men from the ill-fated first boat, please click on the following link: Lieutenant Robin Patrick Gordon

30th April - 2nd May: Very tired and hungry no food since the 23rd, had nothing to eat for six days. Thought up dozens of plans each as impracticable as the next, left with two choices, to fight or surrender. I am confident the men would fight if ordered to, but only had one working rifle between us all. The only rifle that was working was because L/Cpl. Willis had used mosquito cream as lubricant. We didn’t even have bayonets, so we had no choice, went into a village and gave ourselves up. The Japanese were away from the village searching for us. The Burmese tied us up rather cruelly with bark string and held us for many hours. It is a frightful thing to become a POW. You have failed, you have lost you liberty and you have a nagging feeling that you should have done better.

When the Japs returned they were really quite decent, they released the tight bonds around our hands and let us sleep for 24 hours. We then were taken to Tigyaing where we stayed in the schoolhouse and were given three meals of curried chicken and rice each day. This would be the only time we were adequately fed during our captivity.

Shortly afterwards we set out for Wuntho on the railway, a village Brigade had proposed attacking only six weeks previously. Shortly afterwards we set out for Maymyo. An uncomfortable rail journey saw us pass through Sagaing and from there to the Dufferin Fort via the Ava Bridge which spanned the Irrawaddy. The bridge was still in disrepair after it had been blown to blazes by the RAF. We crossed the river in a sort of barge followed by a dreadful march to Mandalay and finally another train to Maymyo. Maymyo was the hill station for Mandalay, probably a lovely place in peacetime, but it was a hell camp for us prisoners, where we were expected to learn Japanese drill. We were put into open fronted sheds, which used to be the servants quarters for the well to do. We remained at Maymyo for about two weeks, but it seemed like an eternity.

Returning to Lt. Wilding's memoir, he recalled this time in the form of a day to day diary:

2nd April: Marched back towards Inywa village, needed water that we knew we could get from a dried up riverbed called the Nalo Chaung. A very nasty march of 10-12 miles.

3rd April: Hoped that the Japs had abandoned Inywa, so decided to try there again today; got within a couple of miles and sent the Burma Riflemen off to make a recce. Waited all day and the next, with insufficient water.

4th April: The Burmese returned late in the day, without one soldier who had been injured and captured. Needed water, so set off again on the 5th for Nalo Chaung, only just making it.

6th April: Rations low and we still have a long way to go. 2/Lt Pat Gordon took a party to the last ration drop in the hope of finding something, came back with 15 days rations per man. This gave us 17 days rations each, but some of the men couldn’t even carry the load. Stayed here for the 7th and 8th, intending to set out on the 9th. Planned to move southeast and make individual rafts, strong enough to carry a rifle, boots and pack and cross the Irrawaddy supported by these.

9th April: A party of men set out to get water. Returned with one man short (Simons), assumed he had got lost and would be taken captive and made to talk. Decided we could afford to wait three days, then put our plan into action. 9th, 10th and 11th April stayed put, eating slightly more than a days rations each day to reduce the load to 10 days.

12th April: Set off and covered 10 miles, found a stream, superior to the muddy pools of the Nalo Chaung. Bivouacked near here and then found we had bivouacked within 50 yards of a track much used by the Japs.

13th April: Early start to get over the road before traffic started moving, marched well clear of the road, lay up to continue our journey by night. Laid an ambush as heard bells that we thought were on the necks of elephants used by the Japs, turned out to be two buffalo out to graze.

14th April: Night marching has not proved very sensible, so marched by day.

15th April: Left thick jungle behind us and headed due west towards Tigyiang where we intended to launch the rafts. Found a good sight on a hill top with a spring and plenty of bamboo to make the rafts.

16th and 17th April: Most made rafts while a small party went to recce a route to the river. Three days rations left, enough to reach the Meza Valley, where we expected to find friendly villagers who would sell us food.

18th April: Recce party returned and said it was practicable to get to river, so raft making continued.

19th and 20th April: Struggled out of the swamp, tried to find a bit of dry land to dry our clothes. Irrawaddy idea abandoned, thought we could go east, cross the Shweli, where it was only a stream, swing north and go into Kachin country, and there sweat out the monsoon. Riflemen Tunnion and Orlando thought that their home villages would put us up for the duration. It was only 80 miles and we thought we could make it.

21st April: There was hardly any food left so first decided to raid a village, where we in fact bought food. In a change of plan, the Headman promised to put us over the Irrawaddy for a considerable price in silver rupees. He and his brother took us to the river at a racing speed; we had no idea where we were. It was night before we finally embarked, paddled around one island and then disembarked, handed over nearly all our money and set out for the hills, only to find a wide stretch of water between us and the hills. It was the main river! We had been betrayed.

22nd - 28th April: The next six days are very confused in my mind, searched the island which was about a mile long and ½ mile wide. Finished the last of the rations on the 23rd, some villagers gave us one meal for a payment. Tried launching one decrepit boat but it sank.

29th April: Found another boat, which floated, so decided a small group would take the first trip and see what could be done, most of them were killed on reaching the other side. Decided to break into small parties and hide in the elephant grass for three days and to rendezvous at the old bivouac at sunset on the 3rd day.

NB. To read more about the men from the ill-fated first boat, please click on the following link: Lieutenant Robin Patrick Gordon

30th April - 2nd May: Very tired and hungry no food since the 23rd, had nothing to eat for six days. Thought up dozens of plans each as impracticable as the next, left with two choices, to fight or surrender. I am confident the men would fight if ordered to, but only had one working rifle between us all. The only rifle that was working was because L/Cpl. Willis had used mosquito cream as lubricant. We didn’t even have bayonets, so we had no choice, went into a village and gave ourselves up. The Japanese were away from the village searching for us. The Burmese tied us up rather cruelly with bark string and held us for many hours. It is a frightful thing to become a POW. You have failed, you have lost you liberty and you have a nagging feeling that you should have done better.

When the Japs returned they were really quite decent, they released the tight bonds around our hands and let us sleep for 24 hours. We then were taken to Tigyaing where we stayed in the schoolhouse and were given three meals of curried chicken and rice each day. This would be the only time we were adequately fed during our captivity.

Shortly afterwards we set out for Wuntho on the railway, a village Brigade had proposed attacking only six weeks previously. Shortly afterwards we set out for Maymyo. An uncomfortable rail journey saw us pass through Sagaing and from there to the Dufferin Fort via the Ava Bridge which spanned the Irrawaddy. The bridge was still in disrepair after it had been blown to blazes by the RAF. We crossed the river in a sort of barge followed by a dreadful march to Mandalay and finally another train to Maymyo. Maymyo was the hill station for Mandalay, probably a lovely place in peacetime, but it was a hell camp for us prisoners, where we were expected to learn Japanese drill. We were put into open fronted sheds, which used to be the servants quarters for the well to do. We remained at Maymyo for about two weeks, but it seemed like an eternity.

To read more about the Maymyo Concentration Camp and the experiences of the captured Chindits during their time there, please click on the following link: Maymyo Camp

Back home in England, Lt. Wilding's family had received the terrible news that he was now reported as missing in action. On Monday 26th July 1943, some twelve weeks after he had fallen into Japanese hands, the Manchester Evening News published this short article about him:

Manchester Solicitor With Wingate Missing

Lieutenant R. A. Wilding of Billinge Avenue, Blackburn, a partner in the Manchester firm of solicitors: Wilding, Earley and Pegge, is reported missing while serving under the Indian Army Command. He is believed to have been a member of the Wingate's Follies expedition into the Burma interior.

Wilding, who is 32 and a bachelor, is the fourth generation of a family of solicitors. His brother-in-law, Lt.-Colonel Garnett Eccles, of Balderstone, Blackburn, is also serving in India and one of his sisters holds a commission in the ATS. Wilding is an old boy of St. Edmund's College in Hertfordshire.

All the Chindits held at the Maymyo Camp were eventually sent down to Rangoon. This journey was undertaken by rail and lasted just under three days. The men were herded into old cattle trucks along with a Japanese guard for company, many were already suffering from acute dysentery and had to be held from an open doorway to relieve themselves as the train moved steadily southwards. Twenty-four men from Wilding's dispersal group arrived at Rangoon, but only seven survived their time as prisoners of war. Of the 235 Chindits that eventually arrived at Rangoon, 168 died inside the jail or were deliberately killed elsewhere. For the rest, two years of imprisonment lay ahead.

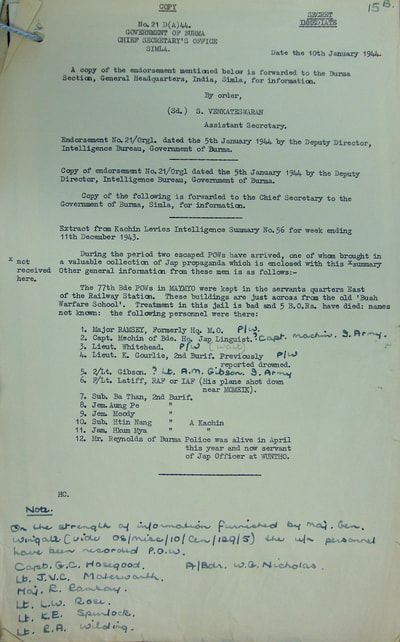

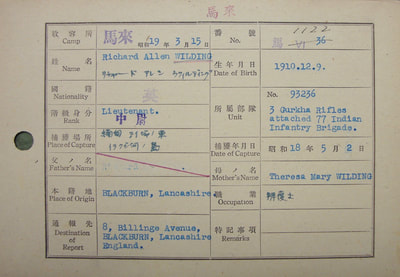

Rangoon Jail had been a civil prison before the war and should have been condemned long before it was used by the Japanese. A great circle of 40 ft walls, with prison blocks radiating out from the central courtyard like the spokes of a wheel. The blocks were occupied as follows:

Block 1 - Downstairs, Japanese Guards. Upstairs, Chinese prisoners.

Block 2 & 7 - Indian and Gurkha prisoners.

Block 3 & 6 - British, American, Australian, South African and New Zealand prisoners.

Block 5 - Solitary confinement cells.

Block 8 - American and British Air crew who had been kept in solitary confinement for weeks in revenge for the first Allied bombings of Tokyo.

Each Block had two storeys and all except Block 5 had four rooms on each storey of about 30 ft x 18 ft square. Downstairs had a concrete floor and some rather uncomfortable beds. Upstairs all floors were wooden with no beds unless you were very very lucky. Each Block had a water trough for washing supplied by the mains, a lean-to cook house and a very primitive latrine, known as the one-holer.

Most of the Chindits were held in Block 6, initially under the command of a New Zealander by the name of Flight-Lieutenant MacDonald. The Chindits were quite unruly during their early days of incarceration and had little intention of making life easy for their captors.

Willy Wilding remembered:

Block 6 was chaotic. Most were Chindits and rebellious with no intention of co-operating with the Nips. Macdonald was young and went along with them. As a result they had a pretty rotten time, to an extent their own fault, but they did it for the best. I felt sorry for Company Quartermaster Sergeant Partington, for some time he had the thankless task of being the senior NCO in the turbulent and ramshackle Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. He did his best, and it was a very good best. Poor chap died quite early on from dysentery.

There was a troublesome soldier called, I think, Tomlinson. As I was Adjutant, I had to try to discipline him. Nothing I could do or say would make him behave, and without discipline there could be no survival. In despair, I looked round for the most revolting job I could think of and decided that it was washing swabs for the hospital. He had septic scabies all over his hands, but I understood the Medical Officer to say that one more infection wouldn't matter.

So I set him to do this job for a week. It did not reform him. Anyway, poor old Tomlinson carried out his sentence and, as he had his hands in warm or warmish water all day, his scabies cleared up. It was reported to me that he said, "Mr. ******* Ramsay couldn't ******* cure my ******* hands, but ******* Wilding did.

After about a month a number of prisoners were released from solitary, including Major Ramsey the senior Medical Officer from Operation Longcloth. But the men's reputation for bloody mindedness was well established by then and morale got very low. Despite Major Ramsey’s valiant efforts we started losing one, often two men a day.

Eventually the Japanese became concerned about the Chindits behaviour and sent over some experienced British officers from Block 3 to deal with the problem. Discipline improved steadily and although the practice of non-cooperation had seemed the right thing to do at the time, the price had been too high and the gains far too small.

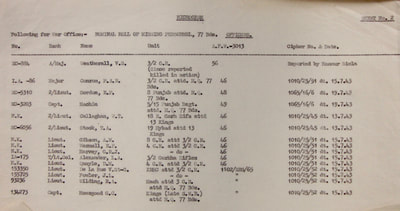

Seen below is a gallery of images depicting Willy Wilding's time as a prisoner of war, including his POW index card. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Manchester Solicitor With Wingate Missing

Lieutenant R. A. Wilding of Billinge Avenue, Blackburn, a partner in the Manchester firm of solicitors: Wilding, Earley and Pegge, is reported missing while serving under the Indian Army Command. He is believed to have been a member of the Wingate's Follies expedition into the Burma interior.

Wilding, who is 32 and a bachelor, is the fourth generation of a family of solicitors. His brother-in-law, Lt.-Colonel Garnett Eccles, of Balderstone, Blackburn, is also serving in India and one of his sisters holds a commission in the ATS. Wilding is an old boy of St. Edmund's College in Hertfordshire.

All the Chindits held at the Maymyo Camp were eventually sent down to Rangoon. This journey was undertaken by rail and lasted just under three days. The men were herded into old cattle trucks along with a Japanese guard for company, many were already suffering from acute dysentery and had to be held from an open doorway to relieve themselves as the train moved steadily southwards. Twenty-four men from Wilding's dispersal group arrived at Rangoon, but only seven survived their time as prisoners of war. Of the 235 Chindits that eventually arrived at Rangoon, 168 died inside the jail or were deliberately killed elsewhere. For the rest, two years of imprisonment lay ahead.

Rangoon Jail had been a civil prison before the war and should have been condemned long before it was used by the Japanese. A great circle of 40 ft walls, with prison blocks radiating out from the central courtyard like the spokes of a wheel. The blocks were occupied as follows:

Block 1 - Downstairs, Japanese Guards. Upstairs, Chinese prisoners.

Block 2 & 7 - Indian and Gurkha prisoners.

Block 3 & 6 - British, American, Australian, South African and New Zealand prisoners.

Block 5 - Solitary confinement cells.

Block 8 - American and British Air crew who had been kept in solitary confinement for weeks in revenge for the first Allied bombings of Tokyo.

Each Block had two storeys and all except Block 5 had four rooms on each storey of about 30 ft x 18 ft square. Downstairs had a concrete floor and some rather uncomfortable beds. Upstairs all floors were wooden with no beds unless you were very very lucky. Each Block had a water trough for washing supplied by the mains, a lean-to cook house and a very primitive latrine, known as the one-holer.

Most of the Chindits were held in Block 6, initially under the command of a New Zealander by the name of Flight-Lieutenant MacDonald. The Chindits were quite unruly during their early days of incarceration and had little intention of making life easy for their captors.

Willy Wilding remembered:

Block 6 was chaotic. Most were Chindits and rebellious with no intention of co-operating with the Nips. Macdonald was young and went along with them. As a result they had a pretty rotten time, to an extent their own fault, but they did it for the best. I felt sorry for Company Quartermaster Sergeant Partington, for some time he had the thankless task of being the senior NCO in the turbulent and ramshackle Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. He did his best, and it was a very good best. Poor chap died quite early on from dysentery.

There was a troublesome soldier called, I think, Tomlinson. As I was Adjutant, I had to try to discipline him. Nothing I could do or say would make him behave, and without discipline there could be no survival. In despair, I looked round for the most revolting job I could think of and decided that it was washing swabs for the hospital. He had septic scabies all over his hands, but I understood the Medical Officer to say that one more infection wouldn't matter.

So I set him to do this job for a week. It did not reform him. Anyway, poor old Tomlinson carried out his sentence and, as he had his hands in warm or warmish water all day, his scabies cleared up. It was reported to me that he said, "Mr. ******* Ramsay couldn't ******* cure my ******* hands, but ******* Wilding did.

After about a month a number of prisoners were released from solitary, including Major Ramsey the senior Medical Officer from Operation Longcloth. But the men's reputation for bloody mindedness was well established by then and morale got very low. Despite Major Ramsey’s valiant efforts we started losing one, often two men a day.

Eventually the Japanese became concerned about the Chindits behaviour and sent over some experienced British officers from Block 3 to deal with the problem. Discipline improved steadily and although the practice of non-cooperation had seemed the right thing to do at the time, the price had been too high and the gains far too small.

Seen below is a gallery of images depicting Willy Wilding's time as a prisoner of war, including his POW index card. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Early in 1944 there was a reshuffling of the prison cell blocks and Block 6 became the hospital for the British, American and Commonwealth POWs. Willy Wilding recalled:

The so-called hospital was a bug-ridden building with a sort of greenhouse type staging on which the sick lay and all too often died. It possessed no beds or sick room equipment of any kind. The drugs available to our doctors were: creosote pills for the treatment of dysentery (useless), copper sulphate for jungle sores (excruciatingly painful), a small amount of quinine for malaria and some aspirin.

With these our excellent Medical Officer coped with: dysentery, beri-beri, malaria, gunshot wounds, jungle sores, the aftermath of amputations, cholera, smallpox, pellagra, broken bones, toothache, two cases of leprosy, and probably a lot more I didn't know about. If you required an operation you were expected to provide a razor blade - there was, of course, no sort of anaesthetic of any kind. If you had to have a tooth out, you bit with the sore tooth on a knife handle until the tooth felt numb, then the M.O. whipped it out as fast as he could.

Beri-beri was the main killer. It is I believe, the retention of fluids owing to the lack of Vitamin B2. In fact, one drowns in one's own body fluid. It seemed a peaceful way to die; but far too many were dying of it. We thought that we could cure it with yeast, but when we asked for some, our request was refused by the Japanese.

I was only a simple solicitor and I have no knowledge of chemistry, but it seemed logical to me that if yeast produced fermentation, then fermentation should produce yeast. So with rice flour, water, and a sort of rough sugar known as jaggeri, I set out to make a sort of foul beer. It certainly fermented and, though it tasted a bit odd, certainly smelt a bit like beer. With Dr. Ramsay's permission, I carried a couple of pints of this stuff to an acute beri-beri patient. I said if he would drink a pint, I would do so, too. So we drank. Next day, he complained that he had been up all night peeing. I was delighted thinking the fluid retention had been defeated. Alas, he died that very night and it had not worked. I could have wept.

For Lt. Wilding, a personal tragedy struck on the 9th April 1945, with the death of long-time friend and comrade, Captain Graham Hosegood. He had suffered with acute jungle sores for many months, but had also contracted beri beri during the latter months of 1944 and often complained of a shortness of breath. On the 6th April, he went down with a strong fever and regardless of the attention of Dr. Ramsay, never recovered.

Willy Wilding remembered:

Graham was buried on the 9th April in the Rangoon Cantonement Cemetery. The funeral party consisted of Flight Lieutenant Edmonds, Lieuts. Horton, Gudgeon, Gibson, Quale and myself. We were as well turned out as borrowing could make us. His coffin was carried out on our shoulders through two ranks of his comrades to the salute. Then through the guardroom with the Japanese Guard at the present. Then carried by hand cart through the streets of Rangoon to the cemetery; a grave was dug - we said what prayers we could - saluted - took back the Union Jack we had used for nearly three hundred friends previously and returned to the jail in sadness. We had lost a great friend.

The so-called hospital was a bug-ridden building with a sort of greenhouse type staging on which the sick lay and all too often died. It possessed no beds or sick room equipment of any kind. The drugs available to our doctors were: creosote pills for the treatment of dysentery (useless), copper sulphate for jungle sores (excruciatingly painful), a small amount of quinine for malaria and some aspirin.

With these our excellent Medical Officer coped with: dysentery, beri-beri, malaria, gunshot wounds, jungle sores, the aftermath of amputations, cholera, smallpox, pellagra, broken bones, toothache, two cases of leprosy, and probably a lot more I didn't know about. If you required an operation you were expected to provide a razor blade - there was, of course, no sort of anaesthetic of any kind. If you had to have a tooth out, you bit with the sore tooth on a knife handle until the tooth felt numb, then the M.O. whipped it out as fast as he could.

Beri-beri was the main killer. It is I believe, the retention of fluids owing to the lack of Vitamin B2. In fact, one drowns in one's own body fluid. It seemed a peaceful way to die; but far too many were dying of it. We thought that we could cure it with yeast, but when we asked for some, our request was refused by the Japanese.

I was only a simple solicitor and I have no knowledge of chemistry, but it seemed logical to me that if yeast produced fermentation, then fermentation should produce yeast. So with rice flour, water, and a sort of rough sugar known as jaggeri, I set out to make a sort of foul beer. It certainly fermented and, though it tasted a bit odd, certainly smelt a bit like beer. With Dr. Ramsay's permission, I carried a couple of pints of this stuff to an acute beri-beri patient. I said if he would drink a pint, I would do so, too. So we drank. Next day, he complained that he had been up all night peeing. I was delighted thinking the fluid retention had been defeated. Alas, he died that very night and it had not worked. I could have wept.

For Lt. Wilding, a personal tragedy struck on the 9th April 1945, with the death of long-time friend and comrade, Captain Graham Hosegood. He had suffered with acute jungle sores for many months, but had also contracted beri beri during the latter months of 1944 and often complained of a shortness of breath. On the 6th April, he went down with a strong fever and regardless of the attention of Dr. Ramsay, never recovered.

Willy Wilding remembered:

Graham was buried on the 9th April in the Rangoon Cantonement Cemetery. The funeral party consisted of Flight Lieutenant Edmonds, Lieuts. Horton, Gudgeon, Gibson, Quale and myself. We were as well turned out as borrowing could make us. His coffin was carried out on our shoulders through two ranks of his comrades to the salute. Then through the guardroom with the Japanese Guard at the present. Then carried by hand cart through the streets of Rangoon to the cemetery; a grave was dug - we said what prayers we could - saluted - took back the Union Jack we had used for nearly three hundred friends previously and returned to the jail in sadness. We had lost a great friend.

Eventually in April 1945, the Japanese decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 men were classified as fit to march and on the 24th April were marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and ill comrades. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, the marchers were north of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge when they ran into the 14th Army. The Japanese Commandant released them in a village called Waw telling them they were free men and then disappeared with the rest of his guards. The now liberated prisoners were situated in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. That night they managed to contact some troops from the West Yorkshire Regiment and were taken to the safety of Allied held territory.

Willy Wilding's recalls his own experience on the Pegu Road:

We set out from Rangoon Jail on the 25th April. My belongings consisted of a small bundle wrapped in my half blanket. I slung this on a pole with a similar bundle belonging to John Wild of the Lancashire Fusiliers. We had proposed to carry it on our shoulders but, as John is 6' (at least) and I am not, the bundles kept slipping down to my end, so we carried the pole in our hands instead.

We had left the seriously ill behind. We felt that there was little hope for them and they might be killed, but in the event they all survived, at least until Rangoon was relieved. That first day we marched fourteen odd miles to the outskirts of Mingaladon. This was quite a severe march for us especially with bare feet. I think I weighed about seven stone at the time. We spent the rest of the night and the whole of the next day there. Our own cooks produced the usual meal of boring old rice.

We had one minor adventure on the way. We heard some planes overhead and everyone took cover in a ditch. Well, not quite everyone. John said in his matter of fact way (he was the most imperturbable chap I have ever met), that we should look daft if the planes turned out to be only Japanese. For my part I saw no harm in looking daft, but, oddly, I found myself unable to let go of my end of the bamboo pole. In the end, they were Japs.

Next night we marched an interminable twenty miles. One British Officer fell out and we are pretty sure was bayoneted to death by a Jap Guard we called "The Jockey", probably because of style of his cap. This was a tragedy because I am fairly sure that if the people with him had kept their heads he could have been saved. At the cost of a minor beating I think they could have delayed matters until the next party arrived and the poor chap could have been put on one of the cooks' handcarts. The march at this point was particularly foul because the RAF & USAAF had strafed transport on the roads, which meant that the surface was badly cut up, which was a bit rough for our bare feet.

NB. It is highly likely that the officer mentioned was former Chindit, Lt. Arthur Sidney Best of the 9th Gurkha Rifles.

The next night we marched to a point just south of Pegu. I don't know how far but would suppose about fifteen miles. We were much troubled by Allied aircraft, which strafed everything that moved. Finally, just before dawn, we went into cover. I fitted nicely into deep ruts gouged out by the wheels of bullock carts and it was exciting but scary to see Spitfires flying overhead.

Towards the end of the afternoon, Ken Spurlock, another former Chindit officer and about thirty other men pushed off. I am not sure if he really should have done. We were still going north, i.e., towards our own troops - the Japs might well have slain us all because of this escape. Ken must some day, tell the story of his group's adventures. The stories I have been told were most amusing and thankfully all this group survived. It is all very well for me to moralise about the rights and wrongs of escaping - the fact is that I was asked to join a similar party being organised by Major Loring. I accepted, but thought we should have taken some quinine from the Medical Officer's stores, because we were taking Joe Edmunds, and he was subject to bouts of malaria. I went off to pinch some but on my return found that we were all ready to move off. Surprisingly, the Japs seemed neither surprised nor upset by Ken Spurlock's departure.

That night was a dreadful one. We had to cross a river, the Sittang perhaps, by bridge which was an obvious target. We got away with that. We left the road and proceeded along a railway line. The sleepers were not far enough apart to accommodate a stride and the ballast was very sharp on our poor feet. One of the Airmen who had recently been in solitary could not go on and we are fairly sure that he was murdered by our friend, The Jockey. Another man who struggled, was our Senior Medical Officer (the late Colonel K.P. Mackenzie), who was much older than the rest of us, he had to be helped along by our two cooks and later on by Captain Brown and Squadron Leader Duckenfield.

NB. It is highly likely that the officer mentioned was Desmond Hugh Fenton, formerly of 22 Squadron, RAF.

That march must have been between ten and fifteen miles and we finished up in a deserted village. I was exhausted and went straight to sleep, only to be awakened by a considerable and joyous noise. The Japs had departed and left us free men. Under orders, we put out a far too chatty message on the ground (as usual, our seniors would not listen to those of us who had some experience working with air supply) and some enterprising chap manufactured a Union Jack from old rags and cloth. The RAF chaps tried to attract the attention of aircraft by flashing mirrors. They were all too successful and we were strafed by a flight of RIAF (Royal Indian Air Force) Hurribombers. Although the wood in which the village was located was only about 200 yards square, there was only one casualty our most Senior Officer, Brigadier Hobson.

Some chaps lost their nerve and bolted to a neighbouring inhabited village. I could see no future in that. We re-arranged the message to read S.O.S. P.O.W. with a big arrow pointing to the wood and arranged for sentries to ensure that the cloth-hungry locals didn't pinch it. Shortly after this an American Major called Lutz and a Sergeant called Lukas somehow made contact with Allied forces and we were ordered to form up in parties of 50 and, after moonrise, cross the paddy to the next village where we would be met and transported to our own lines.

Paddy Eccles of the Royal Engineers and I were detailed to bring up the rear. A compliment I suppose, but one I could have done without. Some men lost their nerve at this point and it took all Paddy's blarney (and he was an expert) to get them to carry on. Finally, we passed through three lines of Pathan soldiers and were driven back to our own lines. Our hosts were the West Yorks, and they were wonderfully generous. I am a Catholic, and next morning their Chaplain, Father Blundel said Mass for us and we received Holy Communion - some of us for the first time for years. This was very emotional and was a fitting end to a long, frightening, but never dull adventure.

Seen below is a photograph of a group of Chindit POW's, taken shortly after their liberation near Pegu. The uniform they are wearing was handed out to them, along with some much needed food and cigarettes by the advancing soldiers of the 14th Army.

Willy Wilding's recalls his own experience on the Pegu Road:

We set out from Rangoon Jail on the 25th April. My belongings consisted of a small bundle wrapped in my half blanket. I slung this on a pole with a similar bundle belonging to John Wild of the Lancashire Fusiliers. We had proposed to carry it on our shoulders but, as John is 6' (at least) and I am not, the bundles kept slipping down to my end, so we carried the pole in our hands instead.

We had left the seriously ill behind. We felt that there was little hope for them and they might be killed, but in the event they all survived, at least until Rangoon was relieved. That first day we marched fourteen odd miles to the outskirts of Mingaladon. This was quite a severe march for us especially with bare feet. I think I weighed about seven stone at the time. We spent the rest of the night and the whole of the next day there. Our own cooks produced the usual meal of boring old rice.

We had one minor adventure on the way. We heard some planes overhead and everyone took cover in a ditch. Well, not quite everyone. John said in his matter of fact way (he was the most imperturbable chap I have ever met), that we should look daft if the planes turned out to be only Japanese. For my part I saw no harm in looking daft, but, oddly, I found myself unable to let go of my end of the bamboo pole. In the end, they were Japs.

Next night we marched an interminable twenty miles. One British Officer fell out and we are pretty sure was bayoneted to death by a Jap Guard we called "The Jockey", probably because of style of his cap. This was a tragedy because I am fairly sure that if the people with him had kept their heads he could have been saved. At the cost of a minor beating I think they could have delayed matters until the next party arrived and the poor chap could have been put on one of the cooks' handcarts. The march at this point was particularly foul because the RAF & USAAF had strafed transport on the roads, which meant that the surface was badly cut up, which was a bit rough for our bare feet.

NB. It is highly likely that the officer mentioned was former Chindit, Lt. Arthur Sidney Best of the 9th Gurkha Rifles.

The next night we marched to a point just south of Pegu. I don't know how far but would suppose about fifteen miles. We were much troubled by Allied aircraft, which strafed everything that moved. Finally, just before dawn, we went into cover. I fitted nicely into deep ruts gouged out by the wheels of bullock carts and it was exciting but scary to see Spitfires flying overhead.

Towards the end of the afternoon, Ken Spurlock, another former Chindit officer and about thirty other men pushed off. I am not sure if he really should have done. We were still going north, i.e., towards our own troops - the Japs might well have slain us all because of this escape. Ken must some day, tell the story of his group's adventures. The stories I have been told were most amusing and thankfully all this group survived. It is all very well for me to moralise about the rights and wrongs of escaping - the fact is that I was asked to join a similar party being organised by Major Loring. I accepted, but thought we should have taken some quinine from the Medical Officer's stores, because we were taking Joe Edmunds, and he was subject to bouts of malaria. I went off to pinch some but on my return found that we were all ready to move off. Surprisingly, the Japs seemed neither surprised nor upset by Ken Spurlock's departure.

That night was a dreadful one. We had to cross a river, the Sittang perhaps, by bridge which was an obvious target. We got away with that. We left the road and proceeded along a railway line. The sleepers were not far enough apart to accommodate a stride and the ballast was very sharp on our poor feet. One of the Airmen who had recently been in solitary could not go on and we are fairly sure that he was murdered by our friend, The Jockey. Another man who struggled, was our Senior Medical Officer (the late Colonel K.P. Mackenzie), who was much older than the rest of us, he had to be helped along by our two cooks and later on by Captain Brown and Squadron Leader Duckenfield.

NB. It is highly likely that the officer mentioned was Desmond Hugh Fenton, formerly of 22 Squadron, RAF.

That march must have been between ten and fifteen miles and we finished up in a deserted village. I was exhausted and went straight to sleep, only to be awakened by a considerable and joyous noise. The Japs had departed and left us free men. Under orders, we put out a far too chatty message on the ground (as usual, our seniors would not listen to those of us who had some experience working with air supply) and some enterprising chap manufactured a Union Jack from old rags and cloth. The RAF chaps tried to attract the attention of aircraft by flashing mirrors. They were all too successful and we were strafed by a flight of RIAF (Royal Indian Air Force) Hurribombers. Although the wood in which the village was located was only about 200 yards square, there was only one casualty our most Senior Officer, Brigadier Hobson.

Some chaps lost their nerve and bolted to a neighbouring inhabited village. I could see no future in that. We re-arranged the message to read S.O.S. P.O.W. with a big arrow pointing to the wood and arranged for sentries to ensure that the cloth-hungry locals didn't pinch it. Shortly after this an American Major called Lutz and a Sergeant called Lukas somehow made contact with Allied forces and we were ordered to form up in parties of 50 and, after moonrise, cross the paddy to the next village where we would be met and transported to our own lines.

Paddy Eccles of the Royal Engineers and I were detailed to bring up the rear. A compliment I suppose, but one I could have done without. Some men lost their nerve at this point and it took all Paddy's blarney (and he was an expert) to get them to carry on. Finally, we passed through three lines of Pathan soldiers and were driven back to our own lines. Our hosts were the West Yorks, and they were wonderfully generous. I am a Catholic, and next morning their Chaplain, Father Blundel said Mass for us and we received Holy Communion - some of us for the first time for years. This was very emotional and was a fitting end to a long, frightening, but never dull adventure.

Seen below is a photograph of a group of Chindit POW's, taken shortly after their liberation near Pegu. The uniform they are wearing was handed out to them, along with some much needed food and cigarettes by the advancing soldiers of the 14th Army.

Willy Wilding's memoir concludes:

We were flown out to Comilla in Assam, where our American friends were whisked away before we could bid them farewell and shortly afterwards, the RAF personnel went the same way. We were immediately hospitalised and then later sent to Madras by hospitalship.

As we stepped ashore some charming elderly ladies pressed small bags of boiled sweets into our hands.

We were now under India Command. Old sweats will not be surprised to hear that nobody troubled to meet the ship officially. South East Asia Command would have put on a better show. After some more wanderings, we finally finished up at Secunderabad, still in hospital and still N.Y.D. (not yet diagnosed).

Signed: R.A. Wilding

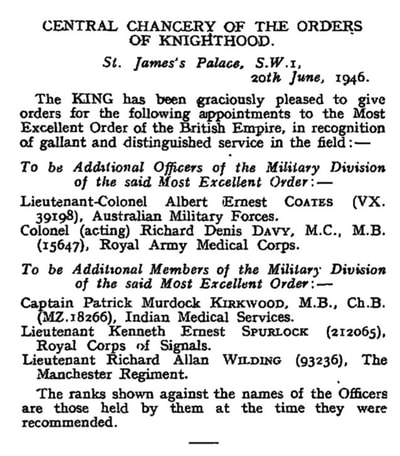

Lt. Wilding spent several more weeks in hospital, before taking a long and much deserved leave period in northern India, close to the Himalayan Mountains. After repatriation to the United Kingdom, he spent a further period in the Army before being demobbed in June 1946. On the 20th June 1946, Wilding was awarded the Military version of the M.B.E. for his services during the Burma campaign and more especially whilst a prisoner of war. In May 1947, he joined the Solicitor's Department of the Board of Trade. In November 1951 he rejoined the Territorial Army, serving with the Princess Louisa's Kensington Regiment and was promoted to Captain in August 1952. Willy Wilding retired from the Territorial Army in 1959 and retired from his role with the Board of Trade in June 1972.

After the war, the American Airmen held in Rangoon Jail formed an old comrades association and often visited the United Kingdom for reunions with their British counterparts. One of the leading activists from the USAAF side was, Karnig Thomasian from New Jersey, who was captured when his B-29 bomber got into difficulties over Rangoon in December 1944. During the 1970's and 1980's, Willy Wilding was a regular patron of these reunions along with other British soldiers, such as Denis Gudgeon, Leon Frank and Alf Nicholls. Sadly, Captain R. A. Wilding passed away in October 1996, with his death being registered at Croydon in South London.

As a footnote to his written memoir, Lt. Wilding assessed whether his time as a prisoner of war had been two years of his life wasted. After some thought he remarked:

I don't think so. Rangoon Central Jail was a horrible place but I do not think it would be daft to think of it as the University I did not attend. I met some remarkable people there and made some very good friends. I learnt a lot about people as a whole and a lot more about myself. I became more self-confident and a little more patient. I wonder if, in the cloistered colleges of Oxford or Cambridge I would have learnt so much. Perhaps, perhaps not; but I would have been a lot more comfortable there!

Seen below is a final gallery of images, including two photographs of the Rangoon Jail POW reunions and the London Gazette announcement of Captain Wilding's appointment to the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE). Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After the war, the American Airmen held in Rangoon Jail formed an old comrades association and often visited the United Kingdom for reunions with their British counterparts. One of the leading activists from the USAAF side was, Karnig Thomasian from New Jersey, who was captured when his B-29 bomber got into difficulties over Rangoon in December 1944. During the 1970's and 1980's, Willy Wilding was a regular patron of these reunions along with other British soldiers, such as Denis Gudgeon, Leon Frank and Alf Nicholls. Sadly, Captain R. A. Wilding passed away in October 1996, with his death being registered at Croydon in South London.

As a footnote to his written memoir, Lt. Wilding assessed whether his time as a prisoner of war had been two years of his life wasted. After some thought he remarked:

I don't think so. Rangoon Central Jail was a horrible place but I do not think it would be daft to think of it as the University I did not attend. I met some remarkable people there and made some very good friends. I learnt a lot about people as a whole and a lot more about myself. I became more self-confident and a little more patient. I wonder if, in the cloistered colleges of Oxford or Cambridge I would have learnt so much. Perhaps, perhaps not; but I would have been a lot more comfortable there!

Seen below is a final gallery of images, including two photographs of the Rangoon Jail POW reunions and the London Gazette announcement of Captain Wilding's appointment to the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE). Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, October 2018.