Pte. Frank Berkovitch

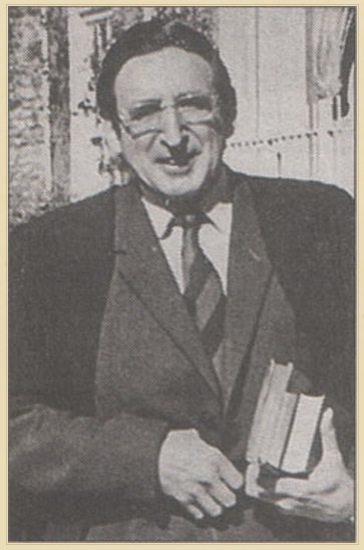

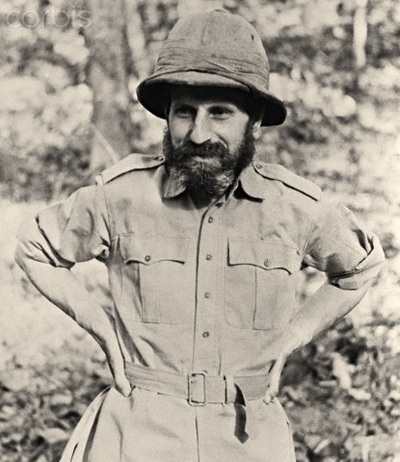

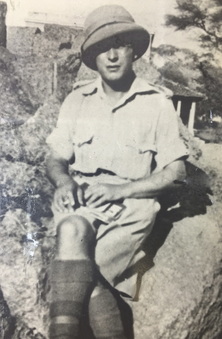

Frank Berkovitch, India 1942.

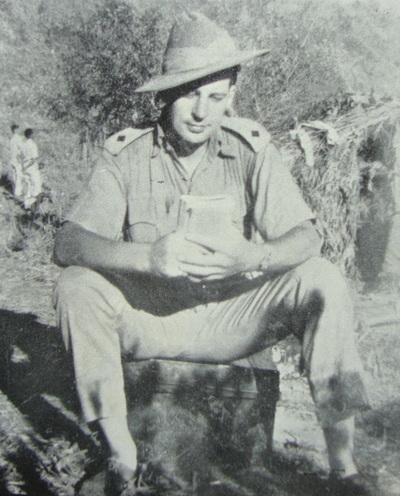

Frank Berkovitch, India 1942.

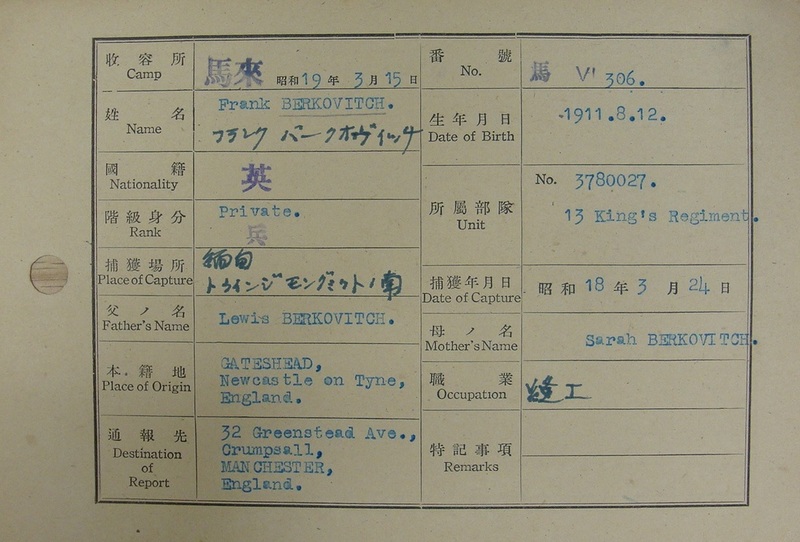

Pte. 3780027 Frank Berkovitch was born on the 12th August 1911 and was the son of Lewis and Sarah Berkovitch from Crumpsall in Manchester. In August 2015, I received an email contact from Daniel Berke, one of Frank's grandsons.

Daniel told me:

My Grandfather, Frank Berkovitch fought with the Chindits. He was captured and was interned at Rangoon. He never spoke of his experiences. He is mentioned in Philip Stibbe's book, 'Return Via Rangoon' describing his time as a POW and he left a brief note of some memories about Wingate and the expedition.

A MOD researcher suggested to us that he was captured at the village of Baw with 8 Column, though his own memoir suggests that he left that area and went south to Pinson and across the Irrawaddy before capture at another village.

I am trying to trace the route, as it is my hope to travel to the area where he would have been operational and ultimately captured. I have found your site to be tremendously helpful, but would be grateful for the opportunity to email some queries to you and see if you can assist in shedding any further light on his time in Burma.

According to Frank's POW index card, he was captured on the 24th March 1943. This date does match up with the engagement at the village of Baw, where Northern Group were hoping to take one last supply drop, before reducing down into small dispersal parties and returning to India. It is therefore understandable why the researcher mentioned by Dan, thought it most likely that Frank had been part of 8 Column on Operation Longcloth. However, if I have learned just one thing when researching the men of the first Wingate expedition, it is never to take anything for granted and always expect the unexpected.

Frank Berkovitch and his time as a prisoner of war was well known to me, through both my reading of Chindit related books and, perhaps more fruitfully, my meetings and conversations with Chindit veterans. As already mentioned, Pte. Berkovitch features in Philip Stibbe's book, 'Return via Rangoon', where the Chindit officer recalls how Berkovitch, a tailor in civil life, assisted in the repairs to the tattered clothing worn by the men inside the jail. He was also the manufacturer of the 'Jap-happy', a single piece loincloth adopted by the prisoners during the long hot Burmese summers.

During my research, I have been extremely fortunate to meet two Chindit veterans, who were both captured by the Japanese during Operation Longcloth and spent just over two years inside Rangoon Jail. Lieutenant Denis Gudgeon and Lieutenant Alec Gibson, both members of 3 Column in 1943, remembered Frank Berkovitch as a devout Jewish soldier, who helped out as a medical orderly in the jail 'hospital' and was also given the unenviable task of sewing the bodies of dead POW's into two rice sacks before they were taken to the English Cantonment Cemetery for burial.

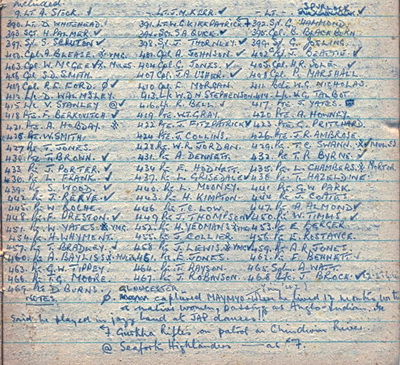

There is also a mention of Frank in the personal diary of Lieutenant John Kerr from 5 Column, who eventually became the Adjutant inside Rangoon Jail. It is a hand-written document and quite difficult to read, but on one page, Kerr suggests that Frank and another man called Chambers (Pte. Leslie John Chambers of 5 Column) were 'verandah orderlies' in the Block 6 hospital. To help the reader visualise the building; the so-called hospital was just the front open verandah section of the block and in effect just a raised platform before you dropped down into the prison yard. The duties of an orderly would have been quite unpleasant, not just in tending to the sick and wounded men, but having to clear away all types of unspeakable mess from the floor of the verandah platform and thus putting oneself at risk of infection or contamination from all kinds of disease.

Another Jewish soldier present in the jail was Pte. Leon Frank from 7 Column. Leon also remembered Frank Berkovitch, recounting an amusing anecdote as part of his audio memoir, which he recorded at the Imperial War Museum in 1995:

There was another fella called Berkovitch and he was a Jewish fellow and he was very very religious. He used to pray every night, he was really sincere, like many of the lads with their own faiths. He used to sleep on his hat at night because we didn't have any pillows or anything like that, so he used to sleep on his hat on top of a block of wood. So when he put his hat on his head in the morning, he looked like Napoleon. He was the funniest thing out.

On my trip out to Burma in March 2008, I spent many an hour in the company of Denis Gudgeon and on some of these occasions was able to record our conversations. Denis was a young Gurkha officer with 3 Column in 1943 and was captured in April that year, very close to the Chindwin River. The following audio excerpt recalls Pte. Berkovitch and his involvement in the burials of Chindit casualties in Rangoon Jail.

Daniel told me:

My Grandfather, Frank Berkovitch fought with the Chindits. He was captured and was interned at Rangoon. He never spoke of his experiences. He is mentioned in Philip Stibbe's book, 'Return Via Rangoon' describing his time as a POW and he left a brief note of some memories about Wingate and the expedition.

A MOD researcher suggested to us that he was captured at the village of Baw with 8 Column, though his own memoir suggests that he left that area and went south to Pinson and across the Irrawaddy before capture at another village.

I am trying to trace the route, as it is my hope to travel to the area where he would have been operational and ultimately captured. I have found your site to be tremendously helpful, but would be grateful for the opportunity to email some queries to you and see if you can assist in shedding any further light on his time in Burma.

According to Frank's POW index card, he was captured on the 24th March 1943. This date does match up with the engagement at the village of Baw, where Northern Group were hoping to take one last supply drop, before reducing down into small dispersal parties and returning to India. It is therefore understandable why the researcher mentioned by Dan, thought it most likely that Frank had been part of 8 Column on Operation Longcloth. However, if I have learned just one thing when researching the men of the first Wingate expedition, it is never to take anything for granted and always expect the unexpected.

Frank Berkovitch and his time as a prisoner of war was well known to me, through both my reading of Chindit related books and, perhaps more fruitfully, my meetings and conversations with Chindit veterans. As already mentioned, Pte. Berkovitch features in Philip Stibbe's book, 'Return via Rangoon', where the Chindit officer recalls how Berkovitch, a tailor in civil life, assisted in the repairs to the tattered clothing worn by the men inside the jail. He was also the manufacturer of the 'Jap-happy', a single piece loincloth adopted by the prisoners during the long hot Burmese summers.

During my research, I have been extremely fortunate to meet two Chindit veterans, who were both captured by the Japanese during Operation Longcloth and spent just over two years inside Rangoon Jail. Lieutenant Denis Gudgeon and Lieutenant Alec Gibson, both members of 3 Column in 1943, remembered Frank Berkovitch as a devout Jewish soldier, who helped out as a medical orderly in the jail 'hospital' and was also given the unenviable task of sewing the bodies of dead POW's into two rice sacks before they were taken to the English Cantonment Cemetery for burial.

There is also a mention of Frank in the personal diary of Lieutenant John Kerr from 5 Column, who eventually became the Adjutant inside Rangoon Jail. It is a hand-written document and quite difficult to read, but on one page, Kerr suggests that Frank and another man called Chambers (Pte. Leslie John Chambers of 5 Column) were 'verandah orderlies' in the Block 6 hospital. To help the reader visualise the building; the so-called hospital was just the front open verandah section of the block and in effect just a raised platform before you dropped down into the prison yard. The duties of an orderly would have been quite unpleasant, not just in tending to the sick and wounded men, but having to clear away all types of unspeakable mess from the floor of the verandah platform and thus putting oneself at risk of infection or contamination from all kinds of disease.

Another Jewish soldier present in the jail was Pte. Leon Frank from 7 Column. Leon also remembered Frank Berkovitch, recounting an amusing anecdote as part of his audio memoir, which he recorded at the Imperial War Museum in 1995:

There was another fella called Berkovitch and he was a Jewish fellow and he was very very religious. He used to pray every night, he was really sincere, like many of the lads with their own faiths. He used to sleep on his hat at night because we didn't have any pillows or anything like that, so he used to sleep on his hat on top of a block of wood. So when he put his hat on his head in the morning, he looked like Napoleon. He was the funniest thing out.

On my trip out to Burma in March 2008, I spent many an hour in the company of Denis Gudgeon and on some of these occasions was able to record our conversations. Denis was a young Gurkha officer with 3 Column in 1943 and was captured in April that year, very close to the Chindwin River. The following audio excerpt recalls Pte. Berkovitch and his involvement in the burials of Chindit casualties in Rangoon Jail.

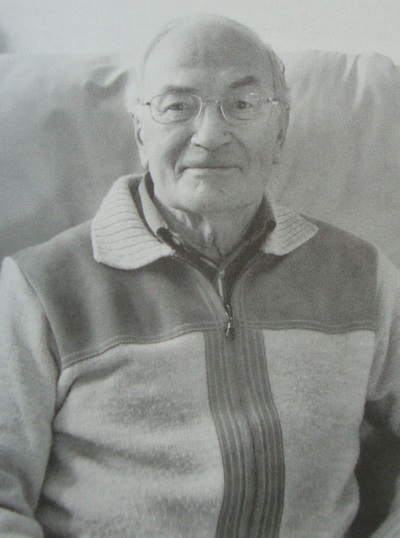

Seen below is a gallery of photographs, showing the men who remembered Frank Berkovitch during his time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

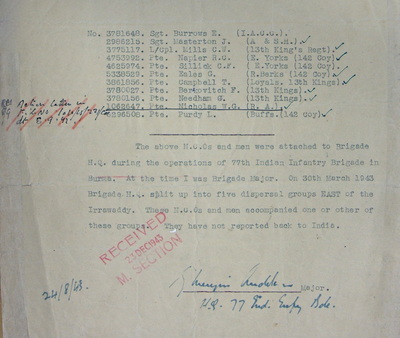

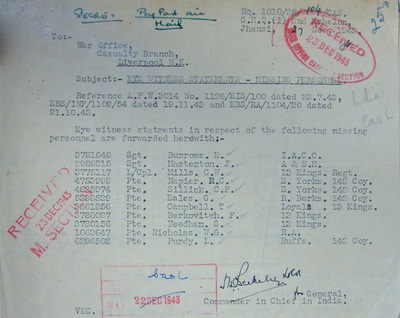

Although up until Dan's communication, I had not focussed too much on Pte. Berkovitch's Chindit pathway, I had reason to place him within Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. He is not mentioned in any of the more detailed and individual missing personnel documents from the WO361 files at the National Archives. However, he is listed on two occasions alongside other men that were known to have served in Brigade HQ in 1943.

One of the documents, is a list of men missing from Brigade HQ as reported by Major Menzies-Anderson (Wingate's Brigde Major) after he had returned to India on the 24th August 1943. It is not clear whether these men were all together when they were reported as missing, or simply individual members of the Brigade HQ as recalled by Menzies-Anderson. It also suggests that they were still at liberty on the 30th March 1943, which calls into question the validity of Frank's date of capture as shown on his POW index card.

Although we can never be 100% certain that Frank Berkovitch was a member of Wingate's Brigade HQ, the evidence presented does point to this being the case, especially in view of the witness statement (seen below) given by Major Menzies-Anderson after his safe return to India. If you then add Frank's well observed opinions of the Brigadier Wingate, which will be revealed in the transcription of his own memoir shown later in this story, the likelihood he served alongside the Chindit leader in 1943 increases still further.

Seen below are the two witness reports, including the one given by Major Menzies-Anderson on the 24th August 1943, that include mention of Pte. Frank Berkovitch. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

One of the documents, is a list of men missing from Brigade HQ as reported by Major Menzies-Anderson (Wingate's Brigde Major) after he had returned to India on the 24th August 1943. It is not clear whether these men were all together when they were reported as missing, or simply individual members of the Brigade HQ as recalled by Menzies-Anderson. It also suggests that they were still at liberty on the 30th March 1943, which calls into question the validity of Frank's date of capture as shown on his POW index card.

Although we can never be 100% certain that Frank Berkovitch was a member of Wingate's Brigade HQ, the evidence presented does point to this being the case, especially in view of the witness statement (seen below) given by Major Menzies-Anderson after his safe return to India. If you then add Frank's well observed opinions of the Brigadier Wingate, which will be revealed in the transcription of his own memoir shown later in this story, the likelihood he served alongside the Chindit leader in 1943 increases still further.

Seen below are the two witness reports, including the one given by Major Menzies-Anderson on the 24th August 1943, that include mention of Pte. Frank Berkovitch. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

After our initial email conversations and some exchange of paperwork and documentation, Daniel came back with this viewpoint:

Hi Steve,

This is fascinating. It seems from the Menzies-Anderson list that Frank was in Brigade HQ and not as the researcher thought, with 8th Column. It seems that the researcher based his theory on the date of capture most likely involving the battle at Baw and therefore, as most of those captured on the 24th were from 8 Column, that Frank must have been with that unit.

I am not satisfied the date of capture is correct as it doesn’t seem to tie in with my Grandfather’s note, which states that they had dispersed following an order from General Command to get back to India. This order was given on the 30th March, already one week after the date of capture stated on his index card. His memoir also clearly states that he was captured attempting to cross the Irrawaddy.

I am also of the opinion that Frank's date of capture is an error. If for instance he was captured on the 24th April instead of March, his pathway would fit in fairly accurately with the Brigade HQ dispersal and the subsequent groups of men being picked up by the Japanese along the east banks of the Irrawaddy in villages south of Inywa, which was the location of Wingate's first attempt at crossing the river on 29th March. To fully understand the predicament suffered by Brigade HQ at this time, please read the story of Leonard Coffin, who was also with this group and whose narrative includes information about some of the men listed on Menzies-Anderson's MIA report. Men such as: Tim Campbell, George Needham, Cecil Mills, Clifford Sillick, George Eales and Leslie Purdy.

The POW index cards were compiled at the Changi POW Camp in Singapore. Senior Officers captured at the surrender of Singapore in February 1942, eventually decided that if possible all Allied POW's were to be recorded and their movements traced from Singapore to places such as Java, the Japanese mainland by ship and of course the infamous Burma-Thailand Railway.

There are 58 box files containing these POW cards, which are held at the National Archives in London. I have searched through them all over a period of five years, picking out the cards for the men of Rangoon Jail. Because most of the men held at Rangoon were captured fighting in the field so to speak and not part of the general surrender at Singapore, their existence was not known to the clerical collators at Changi until early March 1944. So Frank's card was not completed until 15th March 1944, which is the date in the top left hand corner of the front of his card (shown below) next to box named camp.

It is possible that he could not remember his date of capture or someone simply made a clerical error. Of the men mentioned on the Menzies-Anderson list, only Frank, Jock Masterton and Tim Campbell survived their time in Rangoon Jail. It is unfortunate that Frank Berkovitch does not have an individual missing in action report to his name, as this would have given us something more concrete to go on. However, to further strengthen the case for his membership of Wingate's HQ, I have in my possession the missing in action lists for Chindit Columns 5, 7 and 8 and he does not appear on any of these.

Frank Berkovitch would spend just over two years as a prisoner of war in Japanese hands, most of this period was served inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail, but like many of his Chindit comrades, Frank had began his life as a POW in transitory camps at places such as Bhamo and Maymyo. We have already heard about his time in Rangoon Jail from the first-hand accounts given by some of his fellow inmates. Whilst inside the prison, Frank was issued with the POW number 306. He would have had to recite this number in Japanese at each roll call, known as 'tenkos', which took place every morning and evening in the jail.

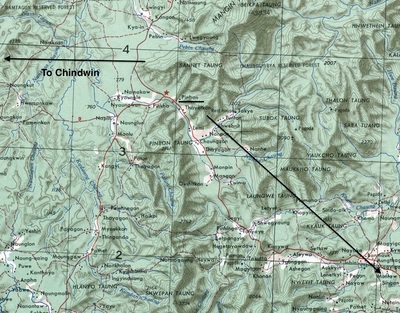

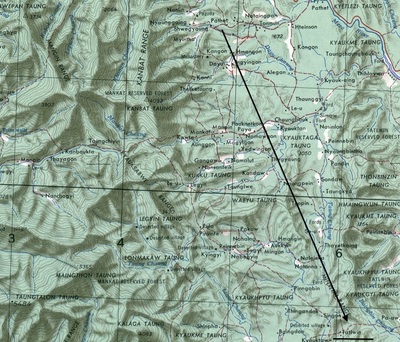

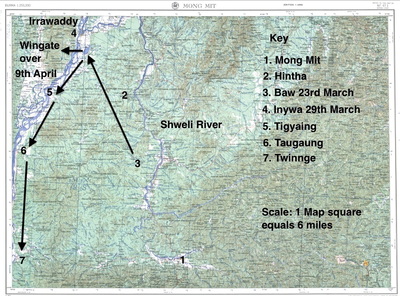

Other information found on his POW index card includes: his name, date of birth, Army service number and regiment, next of kin details and written in Japanese Kanji characters, his place of capture. It was not possible to have this information translated until quite recently (March 2016), but the result proved to be significant. The translation for the place of capture comes out as: Burma, (village) Twinge or Twinnge, (area or zone) Mongmit South. After a brief search on the appropriate map, Twinnge was found to be a small village on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy, a few miles south of Taugaung and some 35 miles west of Mong Mit. Once again, this new information gave more credence to the belief that Frank Berkovitch had belonged to Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth and aligned very well with his own memoir and its description of his capture.

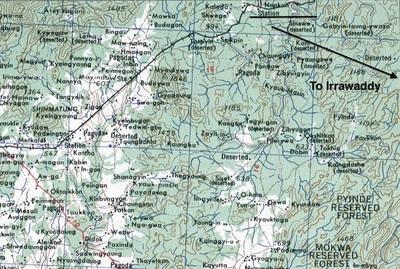

On the reverse of the POW index card, there stood just one single sentence, which was again written in Japanese Kanji characters. This is a recurring sentence and appears on the reverse of many of the cards belonging to soldiers held at Rangoon. It refers to their liberation at the village of Waw, very close to the town of Pegu on the 29th April 1945. As the Japanese prepared to abandon Rangoon, Frank was one of the 400 or so men chosen by his captors to be marched out of the jail on the 24th April. These men became known as the Pegu Marchers and had been selected by the Japanese to be taken to Thailand to work on the infamous 'Death Railway'. In actual fact the men never reached their destination and were freed by their Japanese guards in the small village of Waw on the Pegu Road. Very soon afterwards they were picked up by the advancing 14th Army and their long period of incarceration came to an end.

To read more about the experiences of Chindit prisoners of war, please click on the following link: Chindit POWs

Hi Steve,

This is fascinating. It seems from the Menzies-Anderson list that Frank was in Brigade HQ and not as the researcher thought, with 8th Column. It seems that the researcher based his theory on the date of capture most likely involving the battle at Baw and therefore, as most of those captured on the 24th were from 8 Column, that Frank must have been with that unit.

I am not satisfied the date of capture is correct as it doesn’t seem to tie in with my Grandfather’s note, which states that they had dispersed following an order from General Command to get back to India. This order was given on the 30th March, already one week after the date of capture stated on his index card. His memoir also clearly states that he was captured attempting to cross the Irrawaddy.

I am also of the opinion that Frank's date of capture is an error. If for instance he was captured on the 24th April instead of March, his pathway would fit in fairly accurately with the Brigade HQ dispersal and the subsequent groups of men being picked up by the Japanese along the east banks of the Irrawaddy in villages south of Inywa, which was the location of Wingate's first attempt at crossing the river on 29th March. To fully understand the predicament suffered by Brigade HQ at this time, please read the story of Leonard Coffin, who was also with this group and whose narrative includes information about some of the men listed on Menzies-Anderson's MIA report. Men such as: Tim Campbell, George Needham, Cecil Mills, Clifford Sillick, George Eales and Leslie Purdy.

The POW index cards were compiled at the Changi POW Camp in Singapore. Senior Officers captured at the surrender of Singapore in February 1942, eventually decided that if possible all Allied POW's were to be recorded and their movements traced from Singapore to places such as Java, the Japanese mainland by ship and of course the infamous Burma-Thailand Railway.

There are 58 box files containing these POW cards, which are held at the National Archives in London. I have searched through them all over a period of five years, picking out the cards for the men of Rangoon Jail. Because most of the men held at Rangoon were captured fighting in the field so to speak and not part of the general surrender at Singapore, their existence was not known to the clerical collators at Changi until early March 1944. So Frank's card was not completed until 15th March 1944, which is the date in the top left hand corner of the front of his card (shown below) next to box named camp.

It is possible that he could not remember his date of capture or someone simply made a clerical error. Of the men mentioned on the Menzies-Anderson list, only Frank, Jock Masterton and Tim Campbell survived their time in Rangoon Jail. It is unfortunate that Frank Berkovitch does not have an individual missing in action report to his name, as this would have given us something more concrete to go on. However, to further strengthen the case for his membership of Wingate's HQ, I have in my possession the missing in action lists for Chindit Columns 5, 7 and 8 and he does not appear on any of these.

Frank Berkovitch would spend just over two years as a prisoner of war in Japanese hands, most of this period was served inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail, but like many of his Chindit comrades, Frank had began his life as a POW in transitory camps at places such as Bhamo and Maymyo. We have already heard about his time in Rangoon Jail from the first-hand accounts given by some of his fellow inmates. Whilst inside the prison, Frank was issued with the POW number 306. He would have had to recite this number in Japanese at each roll call, known as 'tenkos', which took place every morning and evening in the jail.

Other information found on his POW index card includes: his name, date of birth, Army service number and regiment, next of kin details and written in Japanese Kanji characters, his place of capture. It was not possible to have this information translated until quite recently (March 2016), but the result proved to be significant. The translation for the place of capture comes out as: Burma, (village) Twinge or Twinnge, (area or zone) Mongmit South. After a brief search on the appropriate map, Twinnge was found to be a small village on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy, a few miles south of Taugaung and some 35 miles west of Mong Mit. Once again, this new information gave more credence to the belief that Frank Berkovitch had belonged to Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth and aligned very well with his own memoir and its description of his capture.

On the reverse of the POW index card, there stood just one single sentence, which was again written in Japanese Kanji characters. This is a recurring sentence and appears on the reverse of many of the cards belonging to soldiers held at Rangoon. It refers to their liberation at the village of Waw, very close to the town of Pegu on the 29th April 1945. As the Japanese prepared to abandon Rangoon, Frank was one of the 400 or so men chosen by his captors to be marched out of the jail on the 24th April. These men became known as the Pegu Marchers and had been selected by the Japanese to be taken to Thailand to work on the infamous 'Death Railway'. In actual fact the men never reached their destination and were freed by their Japanese guards in the small village of Waw on the Pegu Road. Very soon afterwards they were picked up by the advancing 14th Army and their long period of incarceration came to an end.

To read more about the experiences of Chindit prisoners of war, please click on the following link: Chindit POWs

Frank Berkovitch wrote down his experiences as a POW after the war. His short memoir was written out on simple note paper and comprised just thirteen pages. There now follows a transcription of that memoir. I have left the narrative almost untouched, only adding to it where necessary and showing any insertions in brackets, or as annotated notes.

Daniel also had this to say about his grandfather's memoir:

I am afraid my Grandfather’s marks in spelling and handwriting were probably fairly low, so some of the names are a little tricky to decipher, still this is the only account we have. His impressions of Orde Wingate are most interesting. He very rarely discussed his time either in the Chindits or as a POW, although I do recall him saying he was a Bren gunner and could strip and re-assemble the gun blindfolded. After the war, he married my Grandmother Millie and had two sons; Robert and Tony.

The Memoir of Frank Berkovitch.

Chindit, the name given to Orde Wingate's troops in the Burma Operations. The Chinthe is a mythical animal, half-lion and half a flying Griffin, it sits at the entrance to Burmese Pagodas to ward-off evil spirits.

This authentic and moving recollection is of the high tension of the Wingate Expedition into Burma and behind Japanese lines in 1943. I remember and recall from my own knowledge, the magic of his influence and impact, which seemed to inspire the men. He was a very striking and highly unorthodox character for the way he persuaded the War Office and the High Command to try what was called, Long Range Penetration into enemy territory and harass the enemy and cut their communications.

The moment Wingate got up to speak he did not have to search for words. He knew exactly what to say about the great possibilities of this type of warfare, of Long Range columns of men behind enemy lines. If ever a man had risen to an accession, it was Wingate; there is no doubt that Wingate was a man of powerful intellect, courage and determination. I was convinced he was a man of destiny, his missions into Palestine and Abyssinia and the successful infiltration of Burma had certainly shown this.

The Japs and the jungle were no obstacle for his organised infantry, his forces achieved great tangible results, showing that British troops could operate in the Burma jungle as effectively as the Japanese. Of the other men under his command, the nearest to Wingate in his views on the war in Burma was Major Mike Calvert. He had the talent for irregular warfare, for training guerrillas and commandos and the job of attacking the Japanese behind their own lines. Calvert was a natural rebel, but was full of ideas on irregular warfare; he had a great sense of humour and the wonderful zest for (combat).

Memories of my first night in the jungle were not good ones. No sleep was possible, with the noise of the shrieking birds and rustling in the undergrowth, all sounds alien to a city boy. Next morning we had a lecture from Wingate and every point was driven home in his own convincing way, about our commitments to take part in the recapture of Burma. Our job was to penetrate behind the enemy lines, to create havoc and to distract the Japs and cut all lines of communication.

We would be supplied by air drops at designated sites (SD's). We achieved great results in Burma and the operation made and enormous impact, showing that the British troops could operate in the Burma jungle as effectively as the Japanese. There would be many strange tales of hunger and a feeling of exhaustion from the men in Burma and none of the wounded would return. But we had the courage to see things through and we learnt to respect Wingate and admire him for his interest he had for all his men.

Wingate was supremely self-confident, with ruthless and unorthodox ways and a very domineering element in his character and methods. But he could be very gentle in giving orders to his men as they harassed the enemy with their guerrilla attacks and penetration well behind the Jap lines.

The Chindits infiltrated deep into Burma, laden down with a seventy pound pack and Bren gun and fighting many actions along the way. After we collected a successful air drop[1] we then marched hard and moved forward to attack a Jap Garrison at Pinbon. We blew bridges behind us, then through the village of Tatlwin and on to Nankan where we blew up the railway and then we crossed the Irrawaddy.

We then got the orders to pull out (26th March) in small parties so we would be sure that many of the men would reach India and get the information back where it mattered. My party moved south to the Irrawaddy and tried to cross. There was just one boat, which took half the men over while we waited for the boat to return. The current was too strong for two men to bring the boat back, so the rest of us marched on for about seven miles to another village, but found the Japs there. We moved back into the jungle and then moved on through with little hope of getting out of Burma.

With all our food gone and very little water left we were exhausted from moving through the thick jungle and found our progress was very slow. After a short rest we moved on again and came upon tracks of an elephant, which we followed to a pool of filthy water. We put some in our mess tins and boiled the water before we drank it. We then moved on and came to another village, but we did not approach the village right away in case there were any Japanese there.

After a while we started to move forward very slowly, our Sergeant[2] was leading us in front, then from out of nowhere the Japs seemed to spring out from everywhere. Many of the men were wounded and the Sergeant got killed, with the rest of us captured. They tied our hands behind our backs and took all our possessions. They then marched us to a camp called Hintha, then started to interrogate us, but there was little that we could tell them. The Japs then marched us, still with our hands tied behind our backs to a place called Nampaung; they placed us in cages and made fun of us.

Additional notes:

[1] The first Northern Group air drop was at a place called Tonmakeng.

[2] This was possibly Sgt. Edward Burrows, one of the men mentioned on the missing list drawn up by Major Menzies-Anderson.

Seen below are some maps showing the areas through which Frank Berkovitch and Wingate's HQ marched during the early weeks of Operation Longcloth. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Daniel also had this to say about his grandfather's memoir:

I am afraid my Grandfather’s marks in spelling and handwriting were probably fairly low, so some of the names are a little tricky to decipher, still this is the only account we have. His impressions of Orde Wingate are most interesting. He very rarely discussed his time either in the Chindits or as a POW, although I do recall him saying he was a Bren gunner and could strip and re-assemble the gun blindfolded. After the war, he married my Grandmother Millie and had two sons; Robert and Tony.

The Memoir of Frank Berkovitch.

Chindit, the name given to Orde Wingate's troops in the Burma Operations. The Chinthe is a mythical animal, half-lion and half a flying Griffin, it sits at the entrance to Burmese Pagodas to ward-off evil spirits.

This authentic and moving recollection is of the high tension of the Wingate Expedition into Burma and behind Japanese lines in 1943. I remember and recall from my own knowledge, the magic of his influence and impact, which seemed to inspire the men. He was a very striking and highly unorthodox character for the way he persuaded the War Office and the High Command to try what was called, Long Range Penetration into enemy territory and harass the enemy and cut their communications.

The moment Wingate got up to speak he did not have to search for words. He knew exactly what to say about the great possibilities of this type of warfare, of Long Range columns of men behind enemy lines. If ever a man had risen to an accession, it was Wingate; there is no doubt that Wingate was a man of powerful intellect, courage and determination. I was convinced he was a man of destiny, his missions into Palestine and Abyssinia and the successful infiltration of Burma had certainly shown this.

The Japs and the jungle were no obstacle for his organised infantry, his forces achieved great tangible results, showing that British troops could operate in the Burma jungle as effectively as the Japanese. Of the other men under his command, the nearest to Wingate in his views on the war in Burma was Major Mike Calvert. He had the talent for irregular warfare, for training guerrillas and commandos and the job of attacking the Japanese behind their own lines. Calvert was a natural rebel, but was full of ideas on irregular warfare; he had a great sense of humour and the wonderful zest for (combat).

Memories of my first night in the jungle were not good ones. No sleep was possible, with the noise of the shrieking birds and rustling in the undergrowth, all sounds alien to a city boy. Next morning we had a lecture from Wingate and every point was driven home in his own convincing way, about our commitments to take part in the recapture of Burma. Our job was to penetrate behind the enemy lines, to create havoc and to distract the Japs and cut all lines of communication.

We would be supplied by air drops at designated sites (SD's). We achieved great results in Burma and the operation made and enormous impact, showing that the British troops could operate in the Burma jungle as effectively as the Japanese. There would be many strange tales of hunger and a feeling of exhaustion from the men in Burma and none of the wounded would return. But we had the courage to see things through and we learnt to respect Wingate and admire him for his interest he had for all his men.

Wingate was supremely self-confident, with ruthless and unorthodox ways and a very domineering element in his character and methods. But he could be very gentle in giving orders to his men as they harassed the enemy with their guerrilla attacks and penetration well behind the Jap lines.

The Chindits infiltrated deep into Burma, laden down with a seventy pound pack and Bren gun and fighting many actions along the way. After we collected a successful air drop[1] we then marched hard and moved forward to attack a Jap Garrison at Pinbon. We blew bridges behind us, then through the village of Tatlwin and on to Nankan where we blew up the railway and then we crossed the Irrawaddy.

We then got the orders to pull out (26th March) in small parties so we would be sure that many of the men would reach India and get the information back where it mattered. My party moved south to the Irrawaddy and tried to cross. There was just one boat, which took half the men over while we waited for the boat to return. The current was too strong for two men to bring the boat back, so the rest of us marched on for about seven miles to another village, but found the Japs there. We moved back into the jungle and then moved on through with little hope of getting out of Burma.

With all our food gone and very little water left we were exhausted from moving through the thick jungle and found our progress was very slow. After a short rest we moved on again and came upon tracks of an elephant, which we followed to a pool of filthy water. We put some in our mess tins and boiled the water before we drank it. We then moved on and came to another village, but we did not approach the village right away in case there were any Japanese there.

After a while we started to move forward very slowly, our Sergeant[2] was leading us in front, then from out of nowhere the Japs seemed to spring out from everywhere. Many of the men were wounded and the Sergeant got killed, with the rest of us captured. They tied our hands behind our backs and took all our possessions. They then marched us to a camp called Hintha, then started to interrogate us, but there was little that we could tell them. The Japs then marched us, still with our hands tied behind our backs to a place called Nampaung; they placed us in cages and made fun of us.

Additional notes:

[1] The first Northern Group air drop was at a place called Tonmakeng.

[2] This was possibly Sgt. Edward Burrows, one of the men mentioned on the missing list drawn up by Major Menzies-Anderson.

Seen below are some maps showing the areas through which Frank Berkovitch and Wingate's HQ marched during the early weeks of Operation Longcloth. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Frank continues:

Later, we were driven by lorry to a jail in Bhamo. In the jail we saw many more prisoners including Gurkhas. The sanitary conditions were awful with no medical facilities at all for the wounded. At night we lay on bare floorboards, the days seemed to drag on, but we rested at night.

In his book 'Return via Rangoon', Philip Stibbe described Bhamo Jail:

"Bhamo jail consisted of a series of solidly constructed wooden buildings surrounded by a high stone wall. Under the British it had probably been a quite a good jail, as jails go. On our arrival we were searched once again and then put in a large room on the first floor. In this room we found about 60 of our men, most of them were from Column 5 and had failed to cross the Shweli River."

"Conditions in this room were appalling; to begin with we were terribly overcrowded and sanitary arrangements were revoltingly conspicuous by their absence. The Japs would not allow us out of the room for any reason whatsoever and in consequence we had to relieve nature in buckets in a corner of the room."

Frank's narrative resumes:

We were then told to march once more. It was very hard for we were very weak from lack of food. The little rice and vegetables was not enough to give us the energy to carry on. We were in a shocking condition, but the threat of being shot if we fell out (kept us moving), where we got the energy from to carry on, only God knows. We prayed while we marched because without God's help we would not have survived.

We were in a state of exhaustion, but we still carried on, the Japs put some of the worse cases on the ration lorries and the rest of us marched on into the Shweli Valley. By the time we arrived at Lashio we were in a very bad state. We were herded into cattle trucks and sent on our way to Maymyo. We hoped that when we arrived there the Japs would treat us a little better, but it was not to be. The guards carried clubs, which they were very fond of using on the prisoners for the slightest reason.

I saw a pal (of mine) hit by the Japs and then kicked in the shins till' he couldn't walk; it was like being on the edge of a volcano. The treatment in the camp was really rough and very painful at times. They would beat us when we did not bow to the sentry in the camp. Then more prisoners were brought into the camp and dysentery broke out, but the Japs did not help us and conditions deteriorated and lots of our boys died.

After many months there (Maymyo Camp) they started to move us to the railway, then placed us in cattle trucks with sentries to guard us. It was impossible to sit down with so many men in one truck, but at last we arrived at Rangoon Jail where they opened the gates and marched us into the compound.

We found lots of our men from the Brigade in the camp; also, many officers, life in the jail was very bad. Roll call took place morning and night; we had to fall in on parade and with the words of command in Japanese were called to attention, then gave our (POW) number in Japanese. Numbers like Ichi-nee-san-go, then eyes right and then bow. You got beat up if you did not bow to them we worked like slaves.

We lost a lot of wonderful men in the camp for the lack of good food. When we went out on work parties we would try to bring food from outside, but we got caught by the Japs and they beat us across our legs and face. We were losing a lot of men from the bad food, many died every day and you did not know if you were next. Those that had dysentery became so weak; I would not like to describe the filth and stench from the dysentery. When out on working parties the men got scratched or grazed on their legs and arms, which then developed into septic ulcers which slowly rotted the flesh away. Things got so bad they sent a Dr. Ramsay[3] to our part of the camp (Block 6).

He (Ramsay) got some medicines to help him, the men on working parties found some bluestones and brought them back into the camp and gave them to Dr. Ramsay. He grounded the bluestones and made them into a paste to put on the jungle ulcers. My word he saved a lot of men, even though he was deprived of any drugs to work with, still he reduced the death rate in the camp.

The disease that claimed a lot of men was beri beri. This disease attacked the men in the form of chronic diarrhoea, the man got thinner, whilst others swelled-up from the feet upwards, working its way through the body, this caused fluid under the skin and they became inflated with water. About 70% of the Wingate Brigade (that became POW's) died in the camp.

There was a cholera out-break in the camp (mid-June 1944) and Dr. Ramsay risked his life looking after the sick. This was a terrible time for us, for you never knew who was going to be the next victim of this disease. The Japanese were very worried for themselves and so Dr. Ramsay was given medical supplies and drugs to help with the cholera disease and thank God the epidemic was checked, but not before many men died.

Finally, about midday on the 25th April (1945), we were told that all fit men; both British and American prisoners would be leaving for an unknown destination. At this hour the Japs produced large amounts of food for us on the long march. We all felt that all our hopes for an early release were shattered and we would possibly be shot before our troops arrived in Rangoon. The wounded and sick stayed in the camp with a few guards and we hoped they would be ok.

I can only describe the pathetic sight, some of us had homemade sandals, but most of us in bare feet, we marched all day, we were exhausted and footsore. We rested for a short time in an area subjected to bombing as we were near Prome Airfields. It was not safe to move by day, at nightfall we marched to a junction near the Prome Road and then marched through paddy fields and by a village near Pegu. One officer[4] took ill and we never saw him again, probably the Japs shot him.

Additional notes:

[3] Major Raymond Ramsay was the senior Medical Officer in 77th Brigade on Operation Longcloth. He was held in solitary confinement longer than most officers at Rangoon Jail. The decision by the Japanese to keep him in solitary probably caused the unnecessary deaths of many Chindits inside Rangoon Jail in 1943.

[4] This was most likely Lt. Arthur Sidney Best a Gurkha Rifles officer from 2 Column.

Seen below are images of both Major Raymond Ramsay and Lt. Arthur Best. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Later, we were driven by lorry to a jail in Bhamo. In the jail we saw many more prisoners including Gurkhas. The sanitary conditions were awful with no medical facilities at all for the wounded. At night we lay on bare floorboards, the days seemed to drag on, but we rested at night.

In his book 'Return via Rangoon', Philip Stibbe described Bhamo Jail:

"Bhamo jail consisted of a series of solidly constructed wooden buildings surrounded by a high stone wall. Under the British it had probably been a quite a good jail, as jails go. On our arrival we were searched once again and then put in a large room on the first floor. In this room we found about 60 of our men, most of them were from Column 5 and had failed to cross the Shweli River."

"Conditions in this room were appalling; to begin with we were terribly overcrowded and sanitary arrangements were revoltingly conspicuous by their absence. The Japs would not allow us out of the room for any reason whatsoever and in consequence we had to relieve nature in buckets in a corner of the room."

Frank's narrative resumes:

We were then told to march once more. It was very hard for we were very weak from lack of food. The little rice and vegetables was not enough to give us the energy to carry on. We were in a shocking condition, but the threat of being shot if we fell out (kept us moving), where we got the energy from to carry on, only God knows. We prayed while we marched because without God's help we would not have survived.

We were in a state of exhaustion, but we still carried on, the Japs put some of the worse cases on the ration lorries and the rest of us marched on into the Shweli Valley. By the time we arrived at Lashio we were in a very bad state. We were herded into cattle trucks and sent on our way to Maymyo. We hoped that when we arrived there the Japs would treat us a little better, but it was not to be. The guards carried clubs, which they were very fond of using on the prisoners for the slightest reason.

I saw a pal (of mine) hit by the Japs and then kicked in the shins till' he couldn't walk; it was like being on the edge of a volcano. The treatment in the camp was really rough and very painful at times. They would beat us when we did not bow to the sentry in the camp. Then more prisoners were brought into the camp and dysentery broke out, but the Japs did not help us and conditions deteriorated and lots of our boys died.

After many months there (Maymyo Camp) they started to move us to the railway, then placed us in cattle trucks with sentries to guard us. It was impossible to sit down with so many men in one truck, but at last we arrived at Rangoon Jail where they opened the gates and marched us into the compound.

We found lots of our men from the Brigade in the camp; also, many officers, life in the jail was very bad. Roll call took place morning and night; we had to fall in on parade and with the words of command in Japanese were called to attention, then gave our (POW) number in Japanese. Numbers like Ichi-nee-san-go, then eyes right and then bow. You got beat up if you did not bow to them we worked like slaves.

We lost a lot of wonderful men in the camp for the lack of good food. When we went out on work parties we would try to bring food from outside, but we got caught by the Japs and they beat us across our legs and face. We were losing a lot of men from the bad food, many died every day and you did not know if you were next. Those that had dysentery became so weak; I would not like to describe the filth and stench from the dysentery. When out on working parties the men got scratched or grazed on their legs and arms, which then developed into septic ulcers which slowly rotted the flesh away. Things got so bad they sent a Dr. Ramsay[3] to our part of the camp (Block 6).

He (Ramsay) got some medicines to help him, the men on working parties found some bluestones and brought them back into the camp and gave them to Dr. Ramsay. He grounded the bluestones and made them into a paste to put on the jungle ulcers. My word he saved a lot of men, even though he was deprived of any drugs to work with, still he reduced the death rate in the camp.

The disease that claimed a lot of men was beri beri. This disease attacked the men in the form of chronic diarrhoea, the man got thinner, whilst others swelled-up from the feet upwards, working its way through the body, this caused fluid under the skin and they became inflated with water. About 70% of the Wingate Brigade (that became POW's) died in the camp.

There was a cholera out-break in the camp (mid-June 1944) and Dr. Ramsay risked his life looking after the sick. This was a terrible time for us, for you never knew who was going to be the next victim of this disease. The Japanese were very worried for themselves and so Dr. Ramsay was given medical supplies and drugs to help with the cholera disease and thank God the epidemic was checked, but not before many men died.

Finally, about midday on the 25th April (1945), we were told that all fit men; both British and American prisoners would be leaving for an unknown destination. At this hour the Japs produced large amounts of food for us on the long march. We all felt that all our hopes for an early release were shattered and we would possibly be shot before our troops arrived in Rangoon. The wounded and sick stayed in the camp with a few guards and we hoped they would be ok.

I can only describe the pathetic sight, some of us had homemade sandals, but most of us in bare feet, we marched all day, we were exhausted and footsore. We rested for a short time in an area subjected to bombing as we were near Prome Airfields. It was not safe to move by day, at nightfall we marched to a junction near the Prome Road and then marched through paddy fields and by a village near Pegu. One officer[4] took ill and we never saw him again, probably the Japs shot him.

Additional notes:

[3] Major Raymond Ramsay was the senior Medical Officer in 77th Brigade on Operation Longcloth. He was held in solitary confinement longer than most officers at Rangoon Jail. The decision by the Japanese to keep him in solitary probably caused the unnecessary deaths of many Chindits inside Rangoon Jail in 1943.

[4] This was most likely Lt. Arthur Sidney Best a Gurkha Rifles officer from 2 Column.

Seen below are images of both Major Raymond Ramsay and Lt. Arthur Best. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Frank Berkovitch's memoir concludes:

We marched again at night; many more fell out of the march and were never seen again. We were resting at the side of the road when we heard aircraft overhead, then we heard heavy explosions from the area of Rangoon and were worried about our lads back in the camp. We then pressed on towards Pegu; we could see the glow in the sky not far from Rangoon. Our feet were very sore and it was agony to march. Words cannot convey the mental torture we were going through, the rest was a prolonged torture we were going through in aching bodies.

The Japs were in a very awkward predicament, with our troops moving in (14th Army) and the Japs trying to get out with the prisoners to a safe place. We did not know where they were taking us; suddenly our planes came overhead during the day and fired their guns as they swooped down on us, being very suspicious of our movements. Words cannot convey the nervous strain put on us, for to be machine-gunned from our planes would be the last straw.

They must have thought we were Japs and we were lucky very few were wounded and killed from the machine gun bullets and cannon fire. We spent the rest of the day hiding in a nearby wood and thinking about the possibilities of escaping, but wondered what chance we would have with the attitude of the Burmese towards us, for they were all for the Japs.

We marched on, everything seemed like a crazy dream. We were weary and footsore and some of the men could not carry on any further, the Colonel[5] told the Japs that the men could not march anymore and persuaded the guards to let us rest in the woods. The cooks were busy getting some food and hot drinks for the men and the Japs let us rest up for the rest of the day. Suddenly, someone shouted out for us to pay attention while Colonel Power made an announcement.

We all turned towards our Colonel, we did not dream what was coming next. Then we heard in a clear voice that everybody could hear that we were all free men. There was an audible gasp from the men, and then some were weeping and laughing, we went crazy with joy, shaking and hugging each other. The Japs had left us; we were advised to stay where we were as our own troops were advancing from the north. However, we were caught up with the Japs trying to get out of Burma and our troops coming in fast; we found ourselves in a very bad spot, we were free, but in great fear.

When some semblance of order was restored we decided we would try and make contact with our own troops. Using all available white clothing and some help from the Burmese, who had now turned on the Japs, I made a Union Jack in record time and laid it out in the paddy field. We hoped that this would show that we were British prisoners of war, just released by the Japanese and they would send us food, a wireless transmitter and medical supplies.

We then heard shelling bombardments in the distance, it must be our troops advancing, then several planes came over very low and must have seen our message and reported back to Head Quarters. From what we were told later on, they thought it impossible that we were prisoners of war and thought it was a Japanese trick they were pulling. So the planes came back and bombed and machine-gunned us as we hid behind some large trees.

Several men clung together in deep holes trying to (protect) ourselves as the planes came back again and again. At last the planes returned to base, a lot of men were killed, but we could not blame our Airmen for they thought we were Japs. How could they know that 400 British and Americans had suddenly appeared out of the blue in no-man's land? They assumed we were Japs, it was very cruel that anyone should have been killed during his first hour of freedom and the tragedy hung over us all.

Our one objective was to get away before the accursed planes returned, we moved back over the paddy fields into a village. The Headman of the village said that there were still Japs around, but the Burmese were hunting them down. This was soon confirmed when rifle fire was heard not far from us. It was very important we try and contact our troops so a Burmese guide and Major Lutz[6] went to try and make contact. They started out up a gentle slope, when suddenly out of the darkness a tense command rang out, our American Major replied and we then knew we were safe.

Figures appeared from the darkness and grasped us by the hands; we moved in a kind of dream, the officer in charge of the patrol told us not to worry as his men would take good care of us. We were told to keep our heads down as there was still firing going on, they then told us that the war was over back home and that the war would not last long in Burma for our lads were moving fast through the country.

We were thrilled to be free again after all the horrors we had been through and in a kind of dream. We moved on and came to some lorries waiting for us out and away from the Japs and toward our lines. One hour later we were shaking hands with an officer from the West Yorkshire Regiment and what a welcome we received.

Then they led us for a wonderful meal and real tea and a drink of rum. We finally sat down around the fire to tell our story and to hear the news from home; that night we went to sleep knowing we were safe again for the first time in years. Saturday was May 1st (1945), three years to the day since we left home. We shall never forget the kindness and hospitality shown to us everywhere we went, but the final seal for all of us was when we heard the good news of our parents at home. It was good to hear that those who were left behind in the camp at Rangoon Jail all got back safely home.

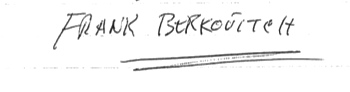

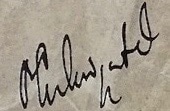

Signed:

We marched again at night; many more fell out of the march and were never seen again. We were resting at the side of the road when we heard aircraft overhead, then we heard heavy explosions from the area of Rangoon and were worried about our lads back in the camp. We then pressed on towards Pegu; we could see the glow in the sky not far from Rangoon. Our feet were very sore and it was agony to march. Words cannot convey the mental torture we were going through, the rest was a prolonged torture we were going through in aching bodies.

The Japs were in a very awkward predicament, with our troops moving in (14th Army) and the Japs trying to get out with the prisoners to a safe place. We did not know where they were taking us; suddenly our planes came overhead during the day and fired their guns as they swooped down on us, being very suspicious of our movements. Words cannot convey the nervous strain put on us, for to be machine-gunned from our planes would be the last straw.

They must have thought we were Japs and we were lucky very few were wounded and killed from the machine gun bullets and cannon fire. We spent the rest of the day hiding in a nearby wood and thinking about the possibilities of escaping, but wondered what chance we would have with the attitude of the Burmese towards us, for they were all for the Japs.

We marched on, everything seemed like a crazy dream. We were weary and footsore and some of the men could not carry on any further, the Colonel[5] told the Japs that the men could not march anymore and persuaded the guards to let us rest in the woods. The cooks were busy getting some food and hot drinks for the men and the Japs let us rest up for the rest of the day. Suddenly, someone shouted out for us to pay attention while Colonel Power made an announcement.

We all turned towards our Colonel, we did not dream what was coming next. Then we heard in a clear voice that everybody could hear that we were all free men. There was an audible gasp from the men, and then some were weeping and laughing, we went crazy with joy, shaking and hugging each other. The Japs had left us; we were advised to stay where we were as our own troops were advancing from the north. However, we were caught up with the Japs trying to get out of Burma and our troops coming in fast; we found ourselves in a very bad spot, we were free, but in great fear.

When some semblance of order was restored we decided we would try and make contact with our own troops. Using all available white clothing and some help from the Burmese, who had now turned on the Japs, I made a Union Jack in record time and laid it out in the paddy field. We hoped that this would show that we were British prisoners of war, just released by the Japanese and they would send us food, a wireless transmitter and medical supplies.

We then heard shelling bombardments in the distance, it must be our troops advancing, then several planes came over very low and must have seen our message and reported back to Head Quarters. From what we were told later on, they thought it impossible that we were prisoners of war and thought it was a Japanese trick they were pulling. So the planes came back and bombed and machine-gunned us as we hid behind some large trees.

Several men clung together in deep holes trying to (protect) ourselves as the planes came back again and again. At last the planes returned to base, a lot of men were killed, but we could not blame our Airmen for they thought we were Japs. How could they know that 400 British and Americans had suddenly appeared out of the blue in no-man's land? They assumed we were Japs, it was very cruel that anyone should have been killed during his first hour of freedom and the tragedy hung over us all.

Our one objective was to get away before the accursed planes returned, we moved back over the paddy fields into a village. The Headman of the village said that there were still Japs around, but the Burmese were hunting them down. This was soon confirmed when rifle fire was heard not far from us. It was very important we try and contact our troops so a Burmese guide and Major Lutz[6] went to try and make contact. They started out up a gentle slope, when suddenly out of the darkness a tense command rang out, our American Major replied and we then knew we were safe.

Figures appeared from the darkness and grasped us by the hands; we moved in a kind of dream, the officer in charge of the patrol told us not to worry as his men would take good care of us. We were told to keep our heads down as there was still firing going on, they then told us that the war was over back home and that the war would not last long in Burma for our lads were moving fast through the country.

We were thrilled to be free again after all the horrors we had been through and in a kind of dream. We moved on and came to some lorries waiting for us out and away from the Japs and toward our lines. One hour later we were shaking hands with an officer from the West Yorkshire Regiment and what a welcome we received.

Then they led us for a wonderful meal and real tea and a drink of rum. We finally sat down around the fire to tell our story and to hear the news from home; that night we went to sleep knowing we were safe again for the first time in years. Saturday was May 1st (1945), three years to the day since we left home. We shall never forget the kindness and hospitality shown to us everywhere we went, but the final seal for all of us was when we heard the good news of our parents at home. It was good to hear that those who were left behind in the camp at Rangoon Jail all got back safely home.

Signed:

Additional notes:

[5] Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Ross Power of the Dogra Regiment. Colonel Power has assumed command of the Pegu group after Brigadier Hobson had been tragically killed by 'friendly fire' from the RAF Hurricane attacks.

[6] Major Charles Lutz of the USAAF.

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this story, including a map showing the various places of interest in regards to Frank Berkovitch and his Chindit journey. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

[5] Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Ross Power of the Dogra Regiment. Colonel Power has assumed command of the Pegu group after Brigadier Hobson had been tragically killed by 'friendly fire' from the RAF Hurricane attacks.

[6] Major Charles Lutz of the USAAF.

Seen below is another gallery of images in relation to this story, including a map showing the various places of interest in regards to Frank Berkovitch and his Chindit journey. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In November 2015, Frank's grandson Daniel Berke and I had a brief telephone conversation, where we discussed his grandfather's time in Burma and as a prisoner of war. Towards the end of our discussion, I asked Dan if he would be willing to write down some of his own personal memories about his grandfather. I am pleased to say that he agreed and here are Dan's recollections:

As a young boy, I recall visits to, or by my Grandfather as not being particularly good fun. High amongst our favoured playtime activities, my brother and I enjoyed shooting, stabbing and bashing each other with a variety of homemade or donated weapons whilst dressed as Roman soldiers, Cowboys and Indians, etc.

When he came to see us, he would tell us to stop. What a spoilsport. At some point I became aware he had been a soldier, had fought in the jungle and had been a POW. I remember him saying that to shoot someone was a terrible thing, although I do not recall when he said this. It didn't seem a very good reason at the time to stop Richard and I having a shoot out and, when Steven came along, tying him up and taking him prisoner.

Then I suppose, we grew up and I began to realise something was wrong. Today, it would be properly diagnosed as PTSD and he would be encouraged to talk and open up. I suppose things were different then. He didn't speak really of his time in the Chindits and somehow I knew it would not be a welcome subject. He did make the odd comment and I must have asked the occasional question, but any information was piecemeal, though looking back, much of what he said and much of what his character was, has been reflected in the little information we have found out about him through our research.

After he died, I read his note about the time in the Chindits; I was simply amazed. He wasn't educated and the note isn't very detailed, but it is an insight into what he and the Chindits faced. He told me he was a Bren gunner and that he was with Wingate who he held in tremendous regard. When he spoke of the camp, he told me that 'we' looked after the sick; he always said 'we'. I have the impression of a group of men who truly helped each other, through whatever difficulties they faced. He didn't speak to me of the capture, the beatings, or the death of his friends.

I can imagine him looking after the sick. He devotedly looked after his wife Millie (whom my daughter is named after) when she was suffering from cancer, from which she died in 1990.

He was a deeply religious Jewish man and in the latter part of his life would attend the synagogue daily. I have been interested to hear recollections of men that he prayed every day. He has been described as serious, which sounds about right. He was certainly not blessed with a sense of humour.

Perhaps what we found most touching was to read from various sources that, as a tailor, he took on the heartbreaking task of sewing the bodies of the dead prisoners into rice sacks, so they would have some sort of improvised coffin. I have no doubt he would have performed this grisly duty with all due dignity. Looking back, and bearing in mind that this must have been an almost daily occurrence, I cannot begin to imagine what horror he must have faced on a daily basis, yet he did not lose his humanity towards the sick and the dead.

I remember that after he was brought home, my Grandfather told me, he was given a 'demob' bag containing various items and two rabbits. He had not eaten kosher food since joining the Chindits as this would not have been possible in the jungle or the camp; simply he had forgotten. When he got home to his mum, after years away, and after she had received a letter saying he was missing presumed killed, she opened the bag, saw the non-kosher rabbits and chased him out the house!

After the War, he married my Grandmother and worked as a tailor until he retired. I understand he briefly had a small factory, but his passion for slow horses put an end to this. He was delightfully old fashioned, always sporting a bow-tie and would always tip his hat when passing a lady in the street. He had two sons and three grandsons and though he didn't live to meet them, six great grandchildren. He died in his late eighties in the year 2000. My son is named after him.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Dan and all of his family, for allowing me to reproduce the memoir of Frank Berkovitch on these website pages. It is very much my privilege to do so. Often, when we are growing up, we do not take the time to consider what our grandparents went through during the years of WW2 and how it shaped their lives from that point onward. When their considerable deeds are finally uncovered, it only reinforces our view, of what an incredibly resilient and resourceful generation they truly were.

As a young boy, I recall visits to, or by my Grandfather as not being particularly good fun. High amongst our favoured playtime activities, my brother and I enjoyed shooting, stabbing and bashing each other with a variety of homemade or donated weapons whilst dressed as Roman soldiers, Cowboys and Indians, etc.

When he came to see us, he would tell us to stop. What a spoilsport. At some point I became aware he had been a soldier, had fought in the jungle and had been a POW. I remember him saying that to shoot someone was a terrible thing, although I do not recall when he said this. It didn't seem a very good reason at the time to stop Richard and I having a shoot out and, when Steven came along, tying him up and taking him prisoner.

Then I suppose, we grew up and I began to realise something was wrong. Today, it would be properly diagnosed as PTSD and he would be encouraged to talk and open up. I suppose things were different then. He didn't speak really of his time in the Chindits and somehow I knew it would not be a welcome subject. He did make the odd comment and I must have asked the occasional question, but any information was piecemeal, though looking back, much of what he said and much of what his character was, has been reflected in the little information we have found out about him through our research.

After he died, I read his note about the time in the Chindits; I was simply amazed. He wasn't educated and the note isn't very detailed, but it is an insight into what he and the Chindits faced. He told me he was a Bren gunner and that he was with Wingate who he held in tremendous regard. When he spoke of the camp, he told me that 'we' looked after the sick; he always said 'we'. I have the impression of a group of men who truly helped each other, through whatever difficulties they faced. He didn't speak to me of the capture, the beatings, or the death of his friends.

I can imagine him looking after the sick. He devotedly looked after his wife Millie (whom my daughter is named after) when she was suffering from cancer, from which she died in 1990.

He was a deeply religious Jewish man and in the latter part of his life would attend the synagogue daily. I have been interested to hear recollections of men that he prayed every day. He has been described as serious, which sounds about right. He was certainly not blessed with a sense of humour.

Perhaps what we found most touching was to read from various sources that, as a tailor, he took on the heartbreaking task of sewing the bodies of the dead prisoners into rice sacks, so they would have some sort of improvised coffin. I have no doubt he would have performed this grisly duty with all due dignity. Looking back, and bearing in mind that this must have been an almost daily occurrence, I cannot begin to imagine what horror he must have faced on a daily basis, yet he did not lose his humanity towards the sick and the dead.

I remember that after he was brought home, my Grandfather told me, he was given a 'demob' bag containing various items and two rabbits. He had not eaten kosher food since joining the Chindits as this would not have been possible in the jungle or the camp; simply he had forgotten. When he got home to his mum, after years away, and after she had received a letter saying he was missing presumed killed, she opened the bag, saw the non-kosher rabbits and chased him out the house!

After the War, he married my Grandmother and worked as a tailor until he retired. I understand he briefly had a small factory, but his passion for slow horses put an end to this. He was delightfully old fashioned, always sporting a bow-tie and would always tip his hat when passing a lady in the street. He had two sons and three grandsons and though he didn't live to meet them, six great grandchildren. He died in his late eighties in the year 2000. My son is named after him.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Dan and all of his family, for allowing me to reproduce the memoir of Frank Berkovitch on these website pages. It is very much my privilege to do so. Often, when we are growing up, we do not take the time to consider what our grandparents went through during the years of WW2 and how it shaped their lives from that point onward. When their considerable deeds are finally uncovered, it only reinforces our view, of what an incredibly resilient and resourceful generation they truly were.

I will leave the final word from this narrative to Pte. Leon Frank. We have already read the anecdote about his Chindit comrade, Pte. Berkovitch and his slouch hat, but simply reading the transcript does not evoke the tenderness and humour felt by Leon at that time. For reasons of copyright, I cannot reproduce the original recording here and so, have spoken the words on his behalf. I sincerely hope I have captured at least some of his sentiment.

Update 15/01/2017.

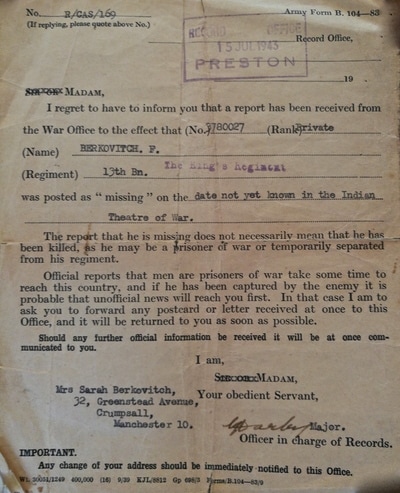

Recently, I was pleased to receive another email from the grandson of Frank Berkovitch. Dan had been searching through some old papers and letters, kept by his great grandmother Sarah Berkovitch, in relation to his grandfather's status as a prison of war in 1943. One document was the standard 'missing in action' notice, sent to Sarah on the 15th July 1943 from the Army Records Office at Preston. This notice simply informed the family that Frank was missing in the Indian theatre of war, and then went on to say that although they knew very little in terms of his whereabouts, it could be that he had fallen into enemy hands and was currently a prisoner of war. The date of the 15th July is of interest, as it is just five days after the official closure date for Operation Longcloth (10th July 1943), whereafter, all personnel still unaccounted for were automatically listed as missing in action.

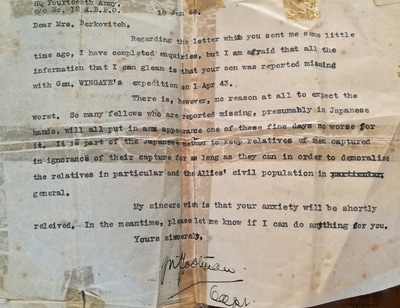

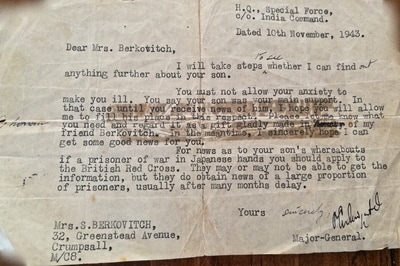

A second document, in the form of a typed letter was sent to the family by a Staff Captain from the offices of the 14th Army in June 1944. This was in response to Sarah's previous enquiry about her son and his current whereabouts. One can only imagine the stress and worry that the family must have been going through by this time, some 12 months after receiving any form of official correspondence about Frank and whether he might still be alive. However, it seems that Sarah Berkovitch was not a woman to give up so easily in pursuit of news about her son. On the 10th November 1943, she received the following letter from a Major-General at the Head Quarters of what was nominated on the letter as Special Force, India Command.

Dear Mrs. Berkovitch,

I will take steps to see whether I can find out anything further about your son. You must not allow your anxiety to make you ill. You say your son was your main support. In that case, until you receive news of him, I hope you will allow me to fill his place in this respect. Please let me know what you need and regard it as a gift gladly made in honour of my friend Berkovitch. In the meantime, I sincerely hope I can get some good news for you.

For news as to your son's whereabouts, if a prisoner of war in Japanese hands, you should apply to the British Red Cross. They may or may not be able to get the information, but they do obtain news of a large proportion of prisoners, usually after many months delay.

Yours sincerely, Major-General

Recently, I was pleased to receive another email from the grandson of Frank Berkovitch. Dan had been searching through some old papers and letters, kept by his great grandmother Sarah Berkovitch, in relation to his grandfather's status as a prison of war in 1943. One document was the standard 'missing in action' notice, sent to Sarah on the 15th July 1943 from the Army Records Office at Preston. This notice simply informed the family that Frank was missing in the Indian theatre of war, and then went on to say that although they knew very little in terms of his whereabouts, it could be that he had fallen into enemy hands and was currently a prisoner of war. The date of the 15th July is of interest, as it is just five days after the official closure date for Operation Longcloth (10th July 1943), whereafter, all personnel still unaccounted for were automatically listed as missing in action.

A second document, in the form of a typed letter was sent to the family by a Staff Captain from the offices of the 14th Army in June 1944. This was in response to Sarah's previous enquiry about her son and his current whereabouts. One can only imagine the stress and worry that the family must have been going through by this time, some 12 months after receiving any form of official correspondence about Frank and whether he might still be alive. However, it seems that Sarah Berkovitch was not a woman to give up so easily in pursuit of news about her son. On the 10th November 1943, she received the following letter from a Major-General at the Head Quarters of what was nominated on the letter as Special Force, India Command.

Dear Mrs. Berkovitch,

I will take steps to see whether I can find out anything further about your son. You must not allow your anxiety to make you ill. You say your son was your main support. In that case, until you receive news of him, I hope you will allow me to fill his place in this respect. Please let me know what you need and regard it as a gift gladly made in honour of my friend Berkovitch. In the meantime, I sincerely hope I can get some good news for you.

For news as to your son's whereabouts, if a prisoner of war in Japanese hands, you should apply to the British Red Cross. They may or may not be able to get the information, but they do obtain news of a large proportion of prisoners, usually after many months delay.

Yours sincerely, Major-General

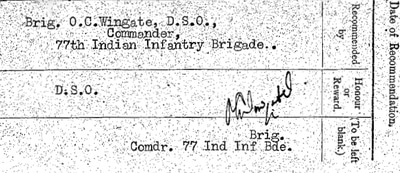

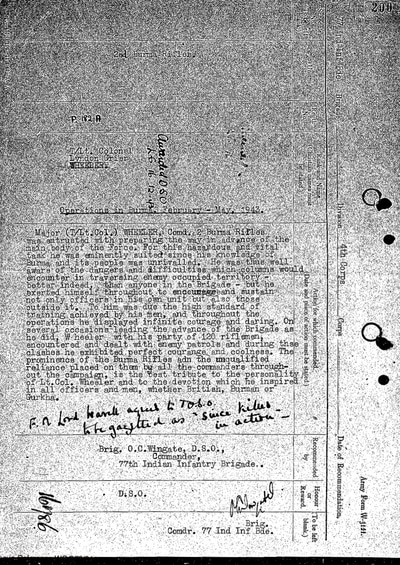

This extremely touching and rather special letter immediately caught my attention and the rather distinctive, but somewhat illegible signature also raised my curiosity. As soon as I saw the signature, I felt certain that it belonged to none-other than Major-General, as he was by that time, Orde Wingate. It is fantastic to think, that during a time when he was busy collating the means to extend his Chindit force to six-times the size of the original, and was attending conferences and meetings all over the sub-continent and farther afield, that the Chindit leader was willing to sit down and write such as warm and supportive note to a mother of one of his former soldiers. It is to his absolute credit that he took the time to do so.

The letter of course, goes a long way in supporting my initial belief that Frank Berkovitch was a member of Wingate's Brigade HQ in 1943 and not part of any of the full Chindit Columns. Why else would Wingate offer up such support to Frank's family?

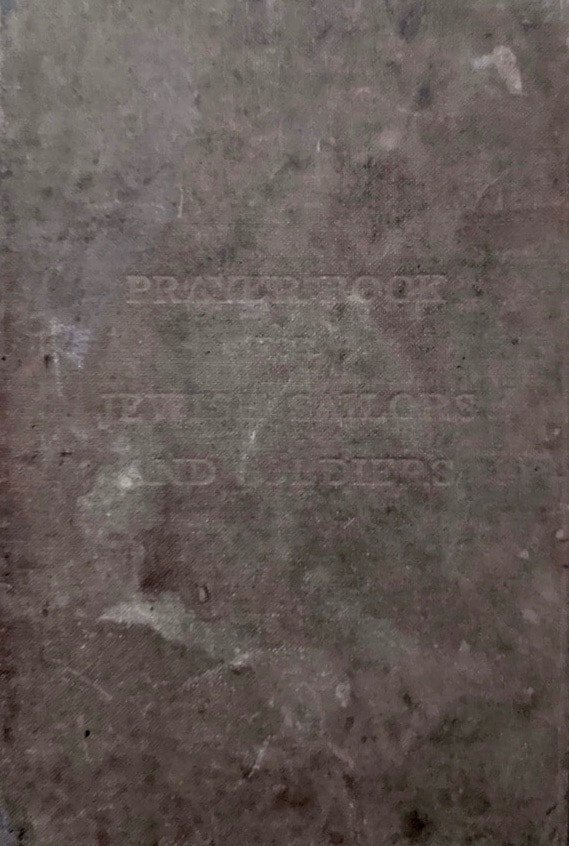

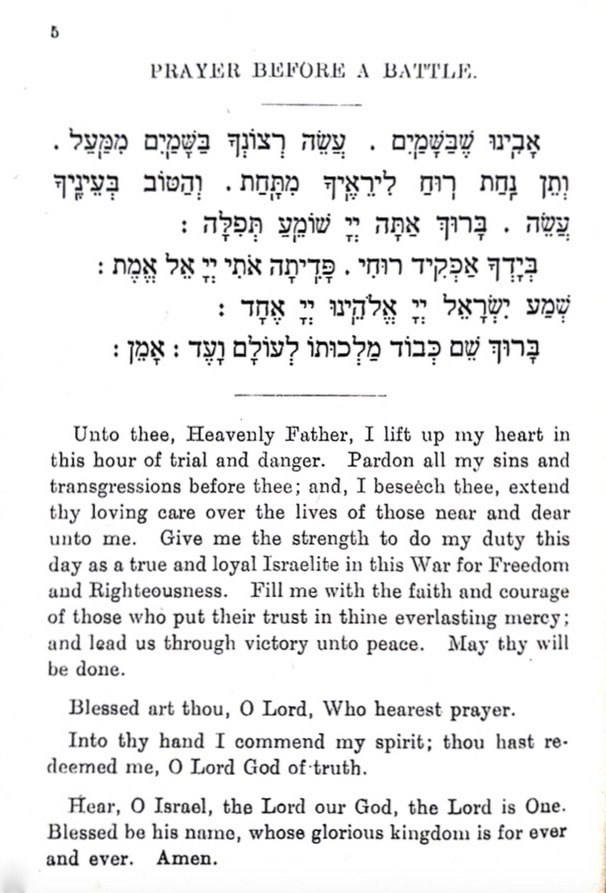

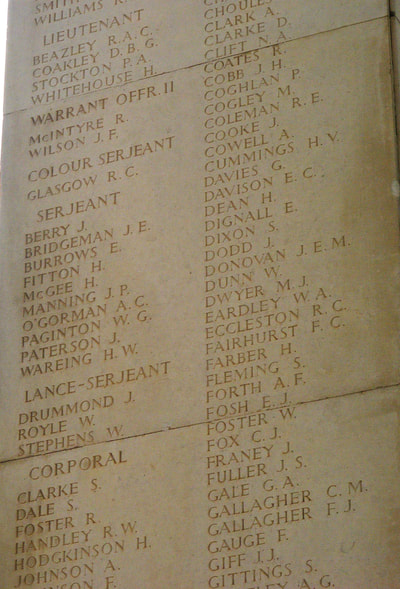

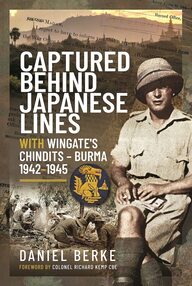

Seen below is a Gallery of images, showing all of the documents mentioned above and also another example of Orde Wingate's signature, from the medal citation of Lt-Colonel Lyndon Grier Wheeler of the Burma Rifles, who received the posthumous award of the Distinguished Service Order for his efforts on Operation Longcloth. Also shown below is the front cover of Frank's Army Prayer Book (Jewish version) and an example of a prayer from the pages within. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The letter of course, goes a long way in supporting my initial belief that Frank Berkovitch was a member of Wingate's Brigade HQ in 1943 and not part of any of the full Chindit Columns. Why else would Wingate offer up such support to Frank's family?

Seen below is a Gallery of images, showing all of the documents mentioned above and also another example of Orde Wingate's signature, from the medal citation of Lt-Colonel Lyndon Grier Wheeler of the Burma Rifles, who received the posthumous award of the Distinguished Service Order for his efforts on Operation Longcloth. Also shown below is the front cover of Frank's Army Prayer Book (Jewish version) and an example of a prayer from the pages within. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Frank Berkovitch.

Frank Berkovitch.

Update 02/05/2017.