Subedar-Major Siblal Thapa

Subedar-Major is the senior rank of all junior commissioned officers in the Indian and Pakistani Armies, and formerly a Viceroy's commissioned officer in the British Indian Army. Although commissioned, they would be considered as senior enlisted personnel and fulfil a role similar to that of the most senior non-commissioned officers in other armies. To this end, Subedar-Major Siblal Thapa of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles, was a role model for his riflemen and was looked up to by all he commanded.

After returning from Burma in May 1943, Siblal wrote down his experiences, which were eventually published in the Regimental Journal of the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles.

That Long Long Trail

From May to December 1942 the 3/2nd carried out very intensive jungle warfare training at the Ramna, Jhansi and Saugor camps. Out of many interesting experiences in this new form of training, one will always be remembered by all ranks of the battalion. Whilst at Ramna we sited our camp near the river bed, which at the time was quite dry. From July 21st heavy rain fell for over three days and although we moved the camp to higher ground, by the night of 26th July we were surrounded by water, with no way of getting out in the darkness.

Morning came with no sign of the water subsiding, movable stores, ammunition, arms etc were tied to trees and the men ordered to climb up and remain in the branches. The whole episode was treated as a joke at first, but when the levels had risen to over twelve feet and everyone had been without food for three days, during which they could not move from their perches up in the trees, it became quite an ordeal. On the morning of July 28th, to everyone's relief the water started to subside and the episode was closed.

The battalion left Jhansi for Imphal on 9th January 1943, passing through, Bramaputra and Dimapur. We travelled by rail, steamboat and long night time marches. The battalion was organised into four independent columns of approximately 350 Gurkha Other Ranks in each. Transport consisted of about one hundred mules and fifteen horses per column and supplies were to be delivered from the air. The men were very fit and in good spirits; each man carried never less than 50 lbs at a time.

On February 7th, the full Brigade left Palel for Tamu, passing through thick jungle country. We (Southern Group) arrived at the Chindwin River on February 15th, the river was at that time about 200-300 yards wide and very deep. We crossed in fifteen small native boats without incident. The next day, on the 16th we had a minor skirmish with the enemy; five Japanese were killed, with no loss to ourselves. After this incident our columns dispersed and I continued on with No. 2 Column, commanded by Major Emmett.

No. 2 Column, moving through very thick jungle arrived at Ywatha. The villagers informed us that there were about forty Japanese nearby at Maingnyaung and our Burmese guides (Burma Riflemen) decided to take us southeast towards Kyaikthin. This march took us nearly one week, afterwards we rested for two days and received more replenishment from the skies. On this occasion we lit small fires among the bushes and the supplies were dropped in a clearing about the size of two football pitches.

We kept away from the Japs and continued on southeast through yet more difficult country. We then stopped in the jungle and Major Emmett decided to send a recce party to the railhead at Yindaik. This patrol reported everything was clear and we advanced to the rail station at Kyaikthin with the objective to destroy it. Whilst advancing we were ambushed at 2100 hours on the 1st March. We fought in spasms for about an hour, after which the dispersal bugle was sounded. Our standing orders were to break into small groups and head for an agreed rendezvous at Taunghan.

I remained in the battle area all night, although it was pretty hopeless trying to gather up the stragglers in the dark, as we could not tell who was friend and who was foe. I spent the whole of the next day (March 2nd) rounding up the stragglers and checking over the battle area. We had lost seven men killed and two wounded. Rifleman Kulbir Pun had sustained multiple wounds from enemy mortar fire and was left close to a nearby village. I never saw any of my wounded men again. I led away my group, consisting of the RAF Liaison Officer, three British Officers, seventy Gurkha Other Ranks and some sixty mules.

After returning from Burma in May 1943, Siblal wrote down his experiences, which were eventually published in the Regimental Journal of the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles.

That Long Long Trail

From May to December 1942 the 3/2nd carried out very intensive jungle warfare training at the Ramna, Jhansi and Saugor camps. Out of many interesting experiences in this new form of training, one will always be remembered by all ranks of the battalion. Whilst at Ramna we sited our camp near the river bed, which at the time was quite dry. From July 21st heavy rain fell for over three days and although we moved the camp to higher ground, by the night of 26th July we were surrounded by water, with no way of getting out in the darkness.

Morning came with no sign of the water subsiding, movable stores, ammunition, arms etc were tied to trees and the men ordered to climb up and remain in the branches. The whole episode was treated as a joke at first, but when the levels had risen to over twelve feet and everyone had been without food for three days, during which they could not move from their perches up in the trees, it became quite an ordeal. On the morning of July 28th, to everyone's relief the water started to subside and the episode was closed.

The battalion left Jhansi for Imphal on 9th January 1943, passing through, Bramaputra and Dimapur. We travelled by rail, steamboat and long night time marches. The battalion was organised into four independent columns of approximately 350 Gurkha Other Ranks in each. Transport consisted of about one hundred mules and fifteen horses per column and supplies were to be delivered from the air. The men were very fit and in good spirits; each man carried never less than 50 lbs at a time.

On February 7th, the full Brigade left Palel for Tamu, passing through thick jungle country. We (Southern Group) arrived at the Chindwin River on February 15th, the river was at that time about 200-300 yards wide and very deep. We crossed in fifteen small native boats without incident. The next day, on the 16th we had a minor skirmish with the enemy; five Japanese were killed, with no loss to ourselves. After this incident our columns dispersed and I continued on with No. 2 Column, commanded by Major Emmett.

No. 2 Column, moving through very thick jungle arrived at Ywatha. The villagers informed us that there were about forty Japanese nearby at Maingnyaung and our Burmese guides (Burma Riflemen) decided to take us southeast towards Kyaikthin. This march took us nearly one week, afterwards we rested for two days and received more replenishment from the skies. On this occasion we lit small fires among the bushes and the supplies were dropped in a clearing about the size of two football pitches.

We kept away from the Japs and continued on southeast through yet more difficult country. We then stopped in the jungle and Major Emmett decided to send a recce party to the railhead at Yindaik. This patrol reported everything was clear and we advanced to the rail station at Kyaikthin with the objective to destroy it. Whilst advancing we were ambushed at 2100 hours on the 1st March. We fought in spasms for about an hour, after which the dispersal bugle was sounded. Our standing orders were to break into small groups and head for an agreed rendezvous at Taunghan.

I remained in the battle area all night, although it was pretty hopeless trying to gather up the stragglers in the dark, as we could not tell who was friend and who was foe. I spent the whole of the next day (March 2nd) rounding up the stragglers and checking over the battle area. We had lost seven men killed and two wounded. Rifleman Kulbir Pun had sustained multiple wounds from enemy mortar fire and was left close to a nearby village. I never saw any of my wounded men again. I led away my group, consisting of the RAF Liaison Officer, three British Officers, seventy Gurkha Other Ranks and some sixty mules.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this part of Siblal Thapa's story, including a map of the area around Kyaikthin Rail Station. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To read more about the battle at Kyaikthin, please click on the following link:

Lt. MacHorton and the battle of Kyaikthin

Lt. MacHorton and the battle of Kyaikthin

Siblal Thapa continues:

Not one of the Sahibs (British Officers) could speak Urdu or Gurkhali and trying to make myself understood was hopeless. We decided to make for the rendezvous location passing by the rail station where there were some dead Japanese bodies. Our route took us north of the railway and through several small villages and into a forest. We arrived at Taunghan on 5th March, where we met two other parties, one led by Colonel Alexander and the other by Jemadar Meher Sing Gurung.

The next day, No. 1 Column met us and we joined up with them and marched to the Irrawaddy. Here we stopped for three days, a rest period badly needed by everyone. The river was 1500 yards wide and very deep, but there was no enemy in the vicinity. On the 11th March we crossed the river by steamer, for which we paid the owner 250 rupees. On the eastern banks we received our third replenishment from the air. No. 1 Column still had their radio, but this supply drop was not successful, with over half the supplies falling into the river. We proceeded to procure extra supplies from the local villagers: eggs, chickens, fruit and rice.

We moved downstream passing through Magiyon village on March 13th. From here the column turned northeast, taking another supply drop near Kyaukaing. This was much more successful and included some supplies of rum, tinned fish and new boots and uniform for the men. On the 17th we unexpectedly met up with No. 3 Column near Pegon. The next day both columns marched southeast and reached the small Nam Pan river stream, where we rested for three days. Locals told us that there was a Japanese battalion (700 men) at Myitson and that they had built new bridges over the Shweli River and constructed new roads in the area. A patrol which was sent to Myitson was fired upon by Japanese mortars but suffered no casualties.

That night we moved from the area around the Nam Pan through difficult country towards another small river, the Nam Mit. At the same time, No. 3 Column were engaged with the enemy at Pago. On March 25th we met the Officer Commanding No. 5 Column (Fergusson), and he explained that his column were a few miles due north resting in the jungle. On March 26th we crossed the Nam Mit somewhere between Pago and a village named Sitton. We continued on southeast and crossed the motor road at about the 12th milestone. Our progress was very slow and the men were extremely tired.

Not one of the Sahibs (British Officers) could speak Urdu or Gurkhali and trying to make myself understood was hopeless. We decided to make for the rendezvous location passing by the rail station where there were some dead Japanese bodies. Our route took us north of the railway and through several small villages and into a forest. We arrived at Taunghan on 5th March, where we met two other parties, one led by Colonel Alexander and the other by Jemadar Meher Sing Gurung.

The next day, No. 1 Column met us and we joined up with them and marched to the Irrawaddy. Here we stopped for three days, a rest period badly needed by everyone. The river was 1500 yards wide and very deep, but there was no enemy in the vicinity. On the 11th March we crossed the river by steamer, for which we paid the owner 250 rupees. On the eastern banks we received our third replenishment from the air. No. 1 Column still had their radio, but this supply drop was not successful, with over half the supplies falling into the river. We proceeded to procure extra supplies from the local villagers: eggs, chickens, fruit and rice.

We moved downstream passing through Magiyon village on March 13th. From here the column turned northeast, taking another supply drop near Kyaukaing. This was much more successful and included some supplies of rum, tinned fish and new boots and uniform for the men. On the 17th we unexpectedly met up with No. 3 Column near Pegon. The next day both columns marched southeast and reached the small Nam Pan river stream, where we rested for three days. Locals told us that there was a Japanese battalion (700 men) at Myitson and that they had built new bridges over the Shweli River and constructed new roads in the area. A patrol which was sent to Myitson was fired upon by Japanese mortars but suffered no casualties.

That night we moved from the area around the Nam Pan through difficult country towards another small river, the Nam Mit. At the same time, No. 3 Column were engaged with the enemy at Pago. On March 25th we met the Officer Commanding No. 5 Column (Fergusson), and he explained that his column were a few miles due north resting in the jungle. On March 26th we crossed the Nam Mit somewhere between Pago and a village named Sitton. We continued on southeast and crossed the motor road at about the 12th milestone. Our progress was very slow and the men were extremely tired.

On the evening of the 29th March, we reached the southern outskirts of Padan village. Here we received the message from Brigade Headquarters that we were surrounded by the enemy and we were to discard our heavy equipment and return to India. It was heartbreaking to see the equipment thrown away and most of the mules had to be chased away. Sadly, some books showing the names of those killed, missing and left in villages were also discarded at this point. Here we had an encounter with the Japanese, who charged at us in the area where we had chased away our mules. Their fire was wild and inaccurate and they incorrectly followed our discarded mules instead of the main column.

We moved away, led by Colonel Alexander, Major Dunlop, Captain Weatherall, Lt. De La Rue, the RAF Officer and Jemadars Dilbahadur Thapa, Kule Gurung, Amar Sing Rana, Meher Sing Gurung, Chandrabir Thapa, Kalbahadur and Khale Gurung. On March 30th, we were on top of Nam Pan Hill, due west of the village Man Sat. The Japanese attacked us, but it was the worst shooting I have ever seen, with fifteen shells falling far from our positions. However, it was clear that whenever we stopped on high ground, the enemy could see us and could fire their mortars in our direction.

On the morning of the 2nd April, we could see the enemy moving about in the thin jungle directly below us and we settled down to take what was coming. The enemy made no effort to conceal themselves, and those we could not see, we could very well hear. They formed up in three lines and started to advance. We remained quiet and concealed and awaited our orders to open fire. The wait was terrific, with the men cool, grim and determined as they squinted along the sights of their rifles. The enemy came on and at two hundred yards began their usual screaming and shouting. We let them come on and then at one hundred yards we let them have it.

Twenty or thirty Japanese fell stone dead and after an hour those left alive retired back into the jungle. They never seemed too determined to winkle us out of our positions and destroy us. If they had been really determined, they could have held us there on the hill until we had starved to death. We had eaten nothing but a few leaves and shoots of bamboo for nearly a week. Our casualties were Jemadar Dilbahadur Thapa, who had mortar fragments in his face, Naik Tekbahadur Thapa, bullet wound to his thigh and Sahib MacHorton, bullet through the cheek of his behind.

After this skirmish we left our last few mules, destroyed our wireless set and dumped our last remaining 3" mortar. We moved away towards Mogok, avoiding Mong Mit and its Japanese garrison. The next day we captured an enemy spy. We could get nothing out of him, so he was taken for a walk. The Rifleman who accompanied him returned shortly afterwards still cleaning his kukri. We rested close to the village of Kunka on the 4th April. Here we were sold various meats, pigs and chickens, with rice, chillies and some tobacco. For us Gurkhas it was a case of eat the meat or starve. Seeing everyone so tired, dirty and worn out tackling that meal is something I shall never forget.

On the 6th April, we were relieved to find ourselves back within the restrictions of our maps. At this point we constituted, 10 British Officers, 8 Gurkha Officers and 350 Gurkha Other Ranks. We were in Kachin territory and generally the villagers treated us well. Around this time we captured three more Japanese spies near Mangla village. The Colonel asked them many questions in English, but got very little from them. Once again they were taken for a walk and if their bodies were ever found, I doubt they found their heads as well. Heading for the Shweli River, we passed through Nampaw village and removed water melons and pumpkins from their fields.

We reached the Shweli on the 13th April, the river at this point was one hundred yards wide and twenty feet deep. The Colonel ordered us to make rafts from bundles of bamboo and using our rifle slings tied together as a pulley rope. The first party got halfway across when the rope parted and they had to be rescued by our strong swimmers. The next day we tried again, but this time only a few men got over before the Japanese attacked us. We held them off until all the men got back to our side, except five men who were left on the far bank. One of these men was Lance Naik Jitbahadur Rana, who was awarded the Indian Distinguished Service Medal on his return to India. Captain Weatherall was very worried about the men we left behind and decided to go back for them. His Orderly came back alone and reported that the Sahib had been killed by a Japanese machine gun burst.

NB. Siblal Thapa's dates tend to be slightly off compared to other testimonies written by other men in his party. This is not really surprising when you think of the physical and mental condition these men must have been in by this time. Captain Weatherall's death is officially recorded as the 11th April 1943, and not the 13th as Siblal Thapa suggests.

To read more about Lance Naik Jitbahadur Rana and his life after the war, please click on the following link and scroll down to the third story on the page: Jitbahadur Rana

To read more about Lance Naik Jitbahadur Rana and his life after the war, please click on the following link and scroll down to the third story on the page: Jitbahadur Rana

Siblal Thapa continues:

Once we were clear of the enemy the C.O. held a conference with all the British and Gurkha Officers. He said that it was useless to attempt to get through the enemy positions and suggested we keep going due east. That night we marched off our maps for the second time and into the hill tracts. On the 16th April we were back at Mangla village, the villagers were once again very helpful, giving us rice, chickens, salt and chillies. They warned us that the enemy had passed through the village most frequently. On the 17th we met up with an ex-Havildar of the Burma Rifles who gave us tremendous help in every way. He produced food from villages, guides for our onward journey and told us that another British unit was crossing the Shweli a few miles to the north of our position.

The Havildar warned us about the Japanese garrison at Mong Mit and told us to get out of the area quickly. Before we left Namni village he gave us two trusted villagers to act as guides; every soul in the village did what they could to help us out. We were in dry country and water became difficult to find. By the 20th April we were forced to drink from a place where we had seen elephants urinating. We still had some rice and buffalo meat given to us by the Havildar and found water by sinking holes in dry rivers beds. Around this time we had trouble from wild elephants and were attacked three or four times by these animals.

On April 25th we finally reached the banks of the Irrawaddy at Sinhnyat. The locals told us that there was a party of Japanese about five miles to the north and another party seven miles to the south. They had no boats for us and it was at Sinhnyat that we had to eat elephant meat. Colonel Alexander and Major Dunlop decided to attempt a crossing, ordering Lt. Clarke to remain in command of the column. The best forty swimmers were selected to go with Colonel Alexander and Major Dunlop. Shortly afterwards, Lt. Chet-kin (Burma Rifles) reported that he had secured two fishing boats from a nearby village at a cost of 500 rupees. One boat could carry about twenty men and the other about twelve.

The Colonel decided to carry out his plan regardless and at 1830 hours handed the column over to Lt. Clarke. About half an hour later, Subedar Padanbahadur Rai and 59 Other Ranks came in. They were originally with Brigade HQ, acting as Brigadier Wingate's body guard. We began to cross the river at 2200 hours and by 0645 hours the following morning only one platoon remained on the east bank. This comprised of Padanbahadur's group and our last platoon under Naik Devsur Ale.

This platoon was attacked when it was just fifty yards from our side of the river. Japanese machine guns and mortars killed everyone except Devsur and one other Rifleman. The men remaining on the east bank with Padanbahadur did not cross the river that day. Under enemy fire we withdrew into the jungle in small parties and due to the thickness of the jungle it became impossible for everyone to reassemble as one group. I pushed on with my party and reached Paganda village located about four miles south of Taugaung, we rested here and I checked the numbers in my party. It consisted of one Havildar from the 10th Gurkha Rifles, Lance Naik Lalbahadur Sahi, Rifleman Tule Ram and 76 Other Ranks.

By the 27th April we had become hopelessly lost from our maps. But, after a night march on the 29th we finally crossed the railway near Tamagon village. We had been without food since the Irrawaddy and our stomachs were grumbling, kept happy only by jungle fruit and berries. Little did I know that it would be many more miles and days before we would taste proper food again.

Once we were clear of the enemy the C.O. held a conference with all the British and Gurkha Officers. He said that it was useless to attempt to get through the enemy positions and suggested we keep going due east. That night we marched off our maps for the second time and into the hill tracts. On the 16th April we were back at Mangla village, the villagers were once again very helpful, giving us rice, chickens, salt and chillies. They warned us that the enemy had passed through the village most frequently. On the 17th we met up with an ex-Havildar of the Burma Rifles who gave us tremendous help in every way. He produced food from villages, guides for our onward journey and told us that another British unit was crossing the Shweli a few miles to the north of our position.

The Havildar warned us about the Japanese garrison at Mong Mit and told us to get out of the area quickly. Before we left Namni village he gave us two trusted villagers to act as guides; every soul in the village did what they could to help us out. We were in dry country and water became difficult to find. By the 20th April we were forced to drink from a place where we had seen elephants urinating. We still had some rice and buffalo meat given to us by the Havildar and found water by sinking holes in dry rivers beds. Around this time we had trouble from wild elephants and were attacked three or four times by these animals.

On April 25th we finally reached the banks of the Irrawaddy at Sinhnyat. The locals told us that there was a party of Japanese about five miles to the north and another party seven miles to the south. They had no boats for us and it was at Sinhnyat that we had to eat elephant meat. Colonel Alexander and Major Dunlop decided to attempt a crossing, ordering Lt. Clarke to remain in command of the column. The best forty swimmers were selected to go with Colonel Alexander and Major Dunlop. Shortly afterwards, Lt. Chet-kin (Burma Rifles) reported that he had secured two fishing boats from a nearby village at a cost of 500 rupees. One boat could carry about twenty men and the other about twelve.

The Colonel decided to carry out his plan regardless and at 1830 hours handed the column over to Lt. Clarke. About half an hour later, Subedar Padanbahadur Rai and 59 Other Ranks came in. They were originally with Brigade HQ, acting as Brigadier Wingate's body guard. We began to cross the river at 2200 hours and by 0645 hours the following morning only one platoon remained on the east bank. This comprised of Padanbahadur's group and our last platoon under Naik Devsur Ale.

This platoon was attacked when it was just fifty yards from our side of the river. Japanese machine guns and mortars killed everyone except Devsur and one other Rifleman. The men remaining on the east bank with Padanbahadur did not cross the river that day. Under enemy fire we withdrew into the jungle in small parties and due to the thickness of the jungle it became impossible for everyone to reassemble as one group. I pushed on with my party and reached Paganda village located about four miles south of Taugaung, we rested here and I checked the numbers in my party. It consisted of one Havildar from the 10th Gurkha Rifles, Lance Naik Lalbahadur Sahi, Rifleman Tule Ram and 76 Other Ranks.

By the 27th April we had become hopelessly lost from our maps. But, after a night march on the 29th we finally crossed the railway near Tamagon village. We had been without food since the Irrawaddy and our stomachs were grumbling, kept happy only by jungle fruit and berries. Little did I know that it would be many more miles and days before we would taste proper food again.

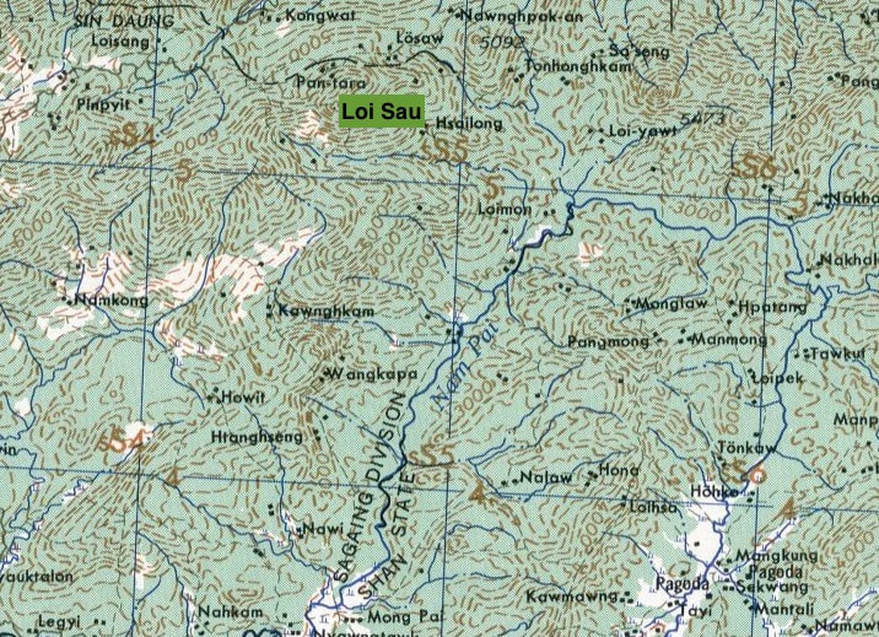

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this section of Siblal's story, including a map of the area around Sinhnyat. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Siblal's testimony concludes:

We were all in a bad way, but we kept plodding on. We averaged just four miles per day during this period as men continually collapsed through exhaustion and we had to wait for them to catch up. We looked terrible, with drawn features and ragged uniforms, the men talked very little as even this took up too much energy. We pushed on northwest in the direction of Yindaik, close to where we had passed on the outward journey. We were still without food and the area was sparsely populated and lacking in villages. Finally, on the 1st May, we entered Panway village and procured a little food and some fruit, but this was not sufficient for all the party.

On the 2nd May we crossed the Mu River about two miles south of Yindaik. The going in this wilderness was hard and painful and we survived on leaves and wild berries. Staggering on we reached the outskirts of Thaiktan on the 5th May, here we were told that the Japanese were all around us. Visions of gaining food here vanished with this news and pushed on due west, choosing to rest the whole of the next day. On the 7th May we just avoided a clash with a Japanese patrol, the next day we crossed the Pegan Chaung and entered the beginning of the Chindwin Valley.

Heading for Maingnyaung we realised that our last proper meal had been on the 25th April, the day we crossed the Irrawaddy. Finally, on the 10th May we reached the Chindwin River, we were still marching, but only just. We struck the river opposite Auktaung village, the same place we had crossed over in February. There were no boats here and I marched my party northwards, suddenly a whistle came from the far bank. It was a Jemadar from the 3/5th Gurkha Rifles. They brought us boats and we all went over safely, later the Jemadar told me that, had I travelled any further north I would have walked straight into the Japanese garrison at Kuntaw.

Arriving at the 3/5th HQ we were given rice followed by tea and biscuits. I met with the C/O of the 3/5th and with Subedar-Major Karak Sing Thapa of the 3/3rd Gurkha Rifles. On the 11th May, we moved up by jeep to Tamu and rested here for three days. After receiving new uniforms, on the 13th we moved to Palel and the next day travelled on to Imphal where we rejoined our own Battalion. With the guidance of Ram and Lord Krishna, the Long, Long Trail had come to an end.

From the Irrawaddy to the Chindwin on the return journey, I had only one Havildar and one Lance Naik to command all the other ranks. My party went through terrible hardships, but always kept their chins up and won through in the end. I still possess the maps I used on the expedition showing that we marched approximately 2000 miles, including wandering off the map on two occasions. When I look back, the trek seems to be nothing but a bad dream. We all marched so far to do so very little, I hope that our younger generations will not have to go through the same ordeal.

We were all in a bad way, but we kept plodding on. We averaged just four miles per day during this period as men continually collapsed through exhaustion and we had to wait for them to catch up. We looked terrible, with drawn features and ragged uniforms, the men talked very little as even this took up too much energy. We pushed on northwest in the direction of Yindaik, close to where we had passed on the outward journey. We were still without food and the area was sparsely populated and lacking in villages. Finally, on the 1st May, we entered Panway village and procured a little food and some fruit, but this was not sufficient for all the party.

On the 2nd May we crossed the Mu River about two miles south of Yindaik. The going in this wilderness was hard and painful and we survived on leaves and wild berries. Staggering on we reached the outskirts of Thaiktan on the 5th May, here we were told that the Japanese were all around us. Visions of gaining food here vanished with this news and pushed on due west, choosing to rest the whole of the next day. On the 7th May we just avoided a clash with a Japanese patrol, the next day we crossed the Pegan Chaung and entered the beginning of the Chindwin Valley.

Heading for Maingnyaung we realised that our last proper meal had been on the 25th April, the day we crossed the Irrawaddy. Finally, on the 10th May we reached the Chindwin River, we were still marching, but only just. We struck the river opposite Auktaung village, the same place we had crossed over in February. There were no boats here and I marched my party northwards, suddenly a whistle came from the far bank. It was a Jemadar from the 3/5th Gurkha Rifles. They brought us boats and we all went over safely, later the Jemadar told me that, had I travelled any further north I would have walked straight into the Japanese garrison at Kuntaw.

Arriving at the 3/5th HQ we were given rice followed by tea and biscuits. I met with the C/O of the 3/5th and with Subedar-Major Karak Sing Thapa of the 3/3rd Gurkha Rifles. On the 11th May, we moved up by jeep to Tamu and rested here for three days. After receiving new uniforms, on the 13th we moved to Palel and the next day travelled on to Imphal where we rejoined our own Battalion. With the guidance of Ram and Lord Krishna, the Long, Long Trail had come to an end.

From the Irrawaddy to the Chindwin on the return journey, I had only one Havildar and one Lance Naik to command all the other ranks. My party went through terrible hardships, but always kept their chins up and won through in the end. I still possess the maps I used on the expedition showing that we marched approximately 2000 miles, including wandering off the map on two occasions. When I look back, the trek seems to be nothing but a bad dream. We all marched so far to do so very little, I hope that our younger generations will not have to go through the same ordeal.

Update 18/12/2020.

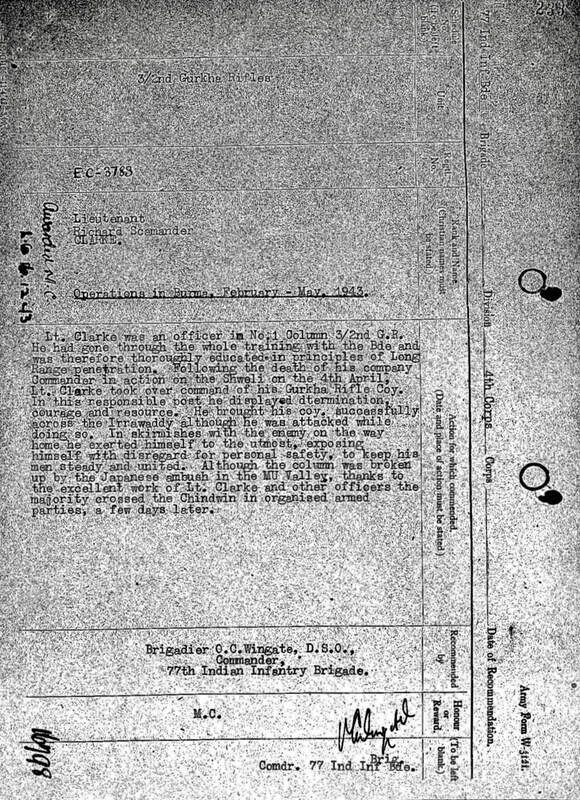

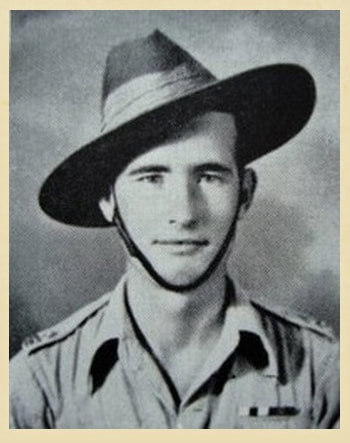

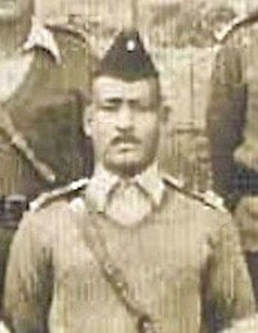

Lt. Richard Scamander Clarke

I fortunate recently to be sent a number of documents and papers in relation to some of the men that served on Operation Longcloth. This included a short memoir written by Lt. Dicky Clarke MC, who was part of No. 1 Column on the first Wingate expedition and who played a significant role during the column's return journey to India in April/May that year. I believe the narrative set out below was first published in one of the Regiment of Gurkhas annual journals, but there is no means to identify which one or when from the papers I have.

Richard Scamander Clarke was born on the 15th July 1921 and was the son of Major Percy Scamander Clarke MC and Violet Ethel Gresham Nicholson from Bexhill-on-Sea in Sussex. From the pages of the London Gazette it seems that Richard had begun his wartime service with the Royal Artillery as a Gunner, but took up an opportunity to join the Indian Army as an Officer Cadet in 1941.

He was commissioned with the Army number, EC-3783 in September 1941 from the Officer Training School in Bangalore and posted to the 2nd Gurkha Rifles based at the time in Baluchistan. He served on Operation Longcloth in No. 1 Column under the command of Major George Dickson Dunlop MC and worked in particular with fellow Gurkha officer, Major Vivian Weatherall. The following year he remained with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and served as a company commander with the battalion in the Arakan region of Burma. Subsequently he served with the Gurkhas and the King's Shropshire Light Infantry in Malaya where he was also wounded, Mentioned in Despatches and awarded a bar to his MC. He joined the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry in 1950 and also served with the Durham Light Infantry in Korea, before retiring in 1976.

What I Remember, by Dicky Clarke

The last message we got from Wingate before we abandoned our mules was seek freedom in the hills. We were by then in the foothills east of the Irrawaddy.

About an hour after we left the mules we heard the Japs mortaring the position thinking we were still there. We took Wingate's advice as there was no alternative and we climbed up higher and higher in an easterly direction. We rested on the top of a wooded ridge and while we were there the Japs caught up with us but we had them pinned down on the forward slope of the hill leading to the ridge we were on. I remember Vivian Weatherell who commanded our Gurkha Company, A Company of No. 1 Column, move forward so that he could overlook the slope the Japs were on and empty his tommy gun into them, swearing appropriately in Gurkhali as he did so.

We knew it would not be long before enemy reinforcements arrived and decided we had better not dawdle but try and cross the main road before we were cut off. So we mounted our 3 inch mortar and fired off all our bombs on the slope the Japs were on and then continued our march eastwards having radioed for fighter air support before abandoning the wireless set, the mortars and the mules that had carried them.

We crossed the road safely which was a major artery between two towns occupied by the Japs and continued through mountainous country making for the Shweli River, which it was intended we would cross and make for China as we knew the Japs would be waiting for us at every turn if we tried to return the way we had come into Burma, with both the Irrawaddy and Chindwin rivers to recross before reaching home.

We had had our last supply drop a week or so ago and from now on we had to live off the country and this we did by obtaining what we could from the villages we passed through and of course, the Burmese platoon was invaluable for this end. We finally reached the Shweli River without encountering the Japs and we found that the river was only about thirty yards wide but very fast flowing and impossible to cross without help. So one or two good swimmers swam across with a line with the intention of making a rope of rifle slings. At !east this was the idea but no sooner had they crossed than the Japs arrived along the far bank and we had to abandon the idea. It was at this time Vivian Weatherell was killed by a Japanese machine gun from across the river.

There was no alternative but to give up the idea of making for China and we started on our return journey westwards instead. We reached the Irrawaddy almost intact but discovered the Japs had removed all the boats to the west bank of the river. A conference was held and it was decided to form an escape party of a few selected officers and men so that at least someone could get back to tell the tale. In the meantime two boats had been found which the villagers had sunk in order to hide them from the Japanese and that night most of the Column and Group Headquarters were paddled across the river, nearly a mile wide, in those two narrow boats which held about fifteen men each sitting jammed up behind each other. Luckily for us the Japs slept soundly that night but with the dawn they we were spotted and they shot up the last two boats leaving only a few men behind on the east bank.

So the column was not too depleted, but not long after we had set off westwards that morning we were well and truly ambushed, resulting in the death of Lt. Colonel Alexander, our Group Commander, Lieutenant George de !a Rue and others. Mortar bombs exploded all amongst us and we just made our way westwards through it all as best we could, visibility being very limited in that type of jungle country. The walking wounded had to keep up as best they could.

We seemed to wade for days down chaungs with steep vertical sides and on finally coming out into flatter country we would be ambushed and each time we got split into smaller and smaller parties. It was a fight against time as lack of food was in the end going to be the deciding factor. At one ambush site the Japanese had posted a notice describing how one could surrender and the remnants of the Commando Platoon almost to a man did exactly that. Of course, the Gurkhas survived much better on no or little rations than the British ranks.

On nearing the Chindwin River a few water buffaloes were seen grazing in paddy fields not far from a village on the river. It was decided to send a couple of Gurkhas to kill one with a kukri as to shoot would have given us away. But to our horror a shot rang out and one of the buffaloes hit the dust. It was now a question of out with the kukris and cut as much of it up and away before being spotted. Hardly had we started than a few Burmese, some armed with British .303 rifles came out of the jungle into the clearing. We parleyed with them to gain time and as we withdrew into the jungle again with some Gurkhas still on the buffalo the Japs arrived and opened up on the position with automatic weapons and mortars.

We made a detour through the jungle making for the river and lay up a few hundred yards from it. We distributed the buffalo meat as best we could amongst us, eating it raw and with relish. Our party then comprised George Dunlop who was the Column Commander, John Fowler and two other officers and about a dozen other ranks. Japs were seen patrolling the river along a track running parallel to it probably from the village that the buffaloes had belonged to. There seemed nothing for it but to try and cross the river that night, but how? It was decided that those who could swim should try and cross and those who couldn't would have to be left. John Fowler couldn't swim but he was given one of our issue water wings to make the attempt.

George Dunlop advised us not to wear our footwear but tie it round our necks which I didn't do. John Fowler got into difficulties a few yards out and one gallant officer helped him back to the bank before swimming over himself. The river was about 500 yards wide and I was surprised how easily I floated. I reached the west bank and found I was near George Dunlop whose boots had floated away with the current and for the next three days the two of us walked westwards, George bare footed. We ate raw paddy which we found in deserted huts in the fields. On the third day we to came to a river running westwards. We knew the Indian traitor army (INA) was about in those parts so we had to be careful and I was not in favour of walking along the track beside the river in case of ambush, but in the end weariness prevailed and we decided to do so come what may.

Suddenly, we heard a shout from across the river, come over this way, Sir. Oh well, I said to George at least we will get something to eat even if they are Japs. George waded across that river as if he had a new lease of life and I followed to be received not by Japs but our own side, an Indian Army unit, the Mahrattas, I think. We were safe once more!

Lt. Richard Scamander Clarke

I fortunate recently to be sent a number of documents and papers in relation to some of the men that served on Operation Longcloth. This included a short memoir written by Lt. Dicky Clarke MC, who was part of No. 1 Column on the first Wingate expedition and who played a significant role during the column's return journey to India in April/May that year. I believe the narrative set out below was first published in one of the Regiment of Gurkhas annual journals, but there is no means to identify which one or when from the papers I have.

Richard Scamander Clarke was born on the 15th July 1921 and was the son of Major Percy Scamander Clarke MC and Violet Ethel Gresham Nicholson from Bexhill-on-Sea in Sussex. From the pages of the London Gazette it seems that Richard had begun his wartime service with the Royal Artillery as a Gunner, but took up an opportunity to join the Indian Army as an Officer Cadet in 1941.

He was commissioned with the Army number, EC-3783 in September 1941 from the Officer Training School in Bangalore and posted to the 2nd Gurkha Rifles based at the time in Baluchistan. He served on Operation Longcloth in No. 1 Column under the command of Major George Dickson Dunlop MC and worked in particular with fellow Gurkha officer, Major Vivian Weatherall. The following year he remained with the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and served as a company commander with the battalion in the Arakan region of Burma. Subsequently he served with the Gurkhas and the King's Shropshire Light Infantry in Malaya where he was also wounded, Mentioned in Despatches and awarded a bar to his MC. He joined the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry in 1950 and also served with the Durham Light Infantry in Korea, before retiring in 1976.

What I Remember, by Dicky Clarke

The last message we got from Wingate before we abandoned our mules was seek freedom in the hills. We were by then in the foothills east of the Irrawaddy.

About an hour after we left the mules we heard the Japs mortaring the position thinking we were still there. We took Wingate's advice as there was no alternative and we climbed up higher and higher in an easterly direction. We rested on the top of a wooded ridge and while we were there the Japs caught up with us but we had them pinned down on the forward slope of the hill leading to the ridge we were on. I remember Vivian Weatherell who commanded our Gurkha Company, A Company of No. 1 Column, move forward so that he could overlook the slope the Japs were on and empty his tommy gun into them, swearing appropriately in Gurkhali as he did so.

We knew it would not be long before enemy reinforcements arrived and decided we had better not dawdle but try and cross the main road before we were cut off. So we mounted our 3 inch mortar and fired off all our bombs on the slope the Japs were on and then continued our march eastwards having radioed for fighter air support before abandoning the wireless set, the mortars and the mules that had carried them.

We crossed the road safely which was a major artery between two towns occupied by the Japs and continued through mountainous country making for the Shweli River, which it was intended we would cross and make for China as we knew the Japs would be waiting for us at every turn if we tried to return the way we had come into Burma, with both the Irrawaddy and Chindwin rivers to recross before reaching home.

We had had our last supply drop a week or so ago and from now on we had to live off the country and this we did by obtaining what we could from the villages we passed through and of course, the Burmese platoon was invaluable for this end. We finally reached the Shweli River without encountering the Japs and we found that the river was only about thirty yards wide but very fast flowing and impossible to cross without help. So one or two good swimmers swam across with a line with the intention of making a rope of rifle slings. At !east this was the idea but no sooner had they crossed than the Japs arrived along the far bank and we had to abandon the idea. It was at this time Vivian Weatherell was killed by a Japanese machine gun from across the river.

There was no alternative but to give up the idea of making for China and we started on our return journey westwards instead. We reached the Irrawaddy almost intact but discovered the Japs had removed all the boats to the west bank of the river. A conference was held and it was decided to form an escape party of a few selected officers and men so that at least someone could get back to tell the tale. In the meantime two boats had been found which the villagers had sunk in order to hide them from the Japanese and that night most of the Column and Group Headquarters were paddled across the river, nearly a mile wide, in those two narrow boats which held about fifteen men each sitting jammed up behind each other. Luckily for us the Japs slept soundly that night but with the dawn they we were spotted and they shot up the last two boats leaving only a few men behind on the east bank.

So the column was not too depleted, but not long after we had set off westwards that morning we were well and truly ambushed, resulting in the death of Lt. Colonel Alexander, our Group Commander, Lieutenant George de !a Rue and others. Mortar bombs exploded all amongst us and we just made our way westwards through it all as best we could, visibility being very limited in that type of jungle country. The walking wounded had to keep up as best they could.

We seemed to wade for days down chaungs with steep vertical sides and on finally coming out into flatter country we would be ambushed and each time we got split into smaller and smaller parties. It was a fight against time as lack of food was in the end going to be the deciding factor. At one ambush site the Japanese had posted a notice describing how one could surrender and the remnants of the Commando Platoon almost to a man did exactly that. Of course, the Gurkhas survived much better on no or little rations than the British ranks.

On nearing the Chindwin River a few water buffaloes were seen grazing in paddy fields not far from a village on the river. It was decided to send a couple of Gurkhas to kill one with a kukri as to shoot would have given us away. But to our horror a shot rang out and one of the buffaloes hit the dust. It was now a question of out with the kukris and cut as much of it up and away before being spotted. Hardly had we started than a few Burmese, some armed with British .303 rifles came out of the jungle into the clearing. We parleyed with them to gain time and as we withdrew into the jungle again with some Gurkhas still on the buffalo the Japs arrived and opened up on the position with automatic weapons and mortars.

We made a detour through the jungle making for the river and lay up a few hundred yards from it. We distributed the buffalo meat as best we could amongst us, eating it raw and with relish. Our party then comprised George Dunlop who was the Column Commander, John Fowler and two other officers and about a dozen other ranks. Japs were seen patrolling the river along a track running parallel to it probably from the village that the buffaloes had belonged to. There seemed nothing for it but to try and cross the river that night, but how? It was decided that those who could swim should try and cross and those who couldn't would have to be left. John Fowler couldn't swim but he was given one of our issue water wings to make the attempt.

George Dunlop advised us not to wear our footwear but tie it round our necks which I didn't do. John Fowler got into difficulties a few yards out and one gallant officer helped him back to the bank before swimming over himself. The river was about 500 yards wide and I was surprised how easily I floated. I reached the west bank and found I was near George Dunlop whose boots had floated away with the current and for the next three days the two of us walked westwards, George bare footed. We ate raw paddy which we found in deserted huts in the fields. On the third day we to came to a river running westwards. We knew the Indian traitor army (INA) was about in those parts so we had to be careful and I was not in favour of walking along the track beside the river in case of ambush, but in the end weariness prevailed and we decided to do so come what may.

Suddenly, we heard a shout from across the river, come over this way, Sir. Oh well, I said to George at least we will get something to eat even if they are Japs. George waded across that river as if he had a new lease of life and I followed to be received not by Japs but our own side, an Indian Army unit, the Mahrattas, I think. We were safe once more!

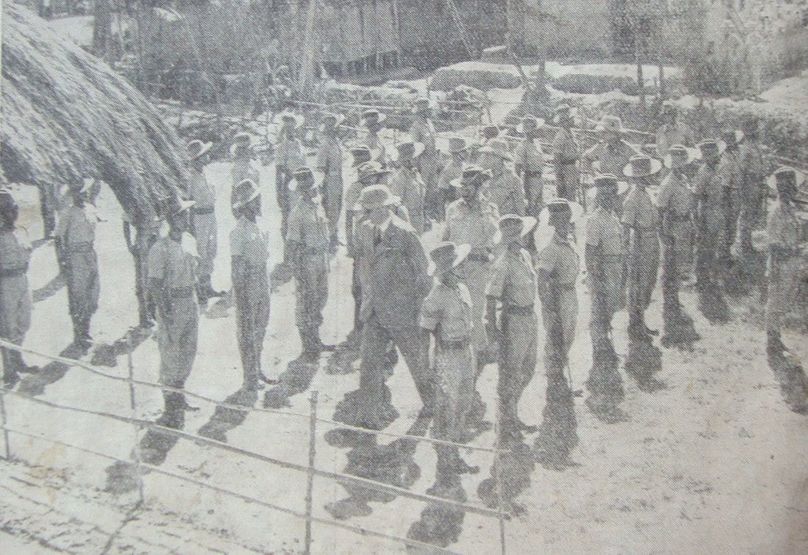

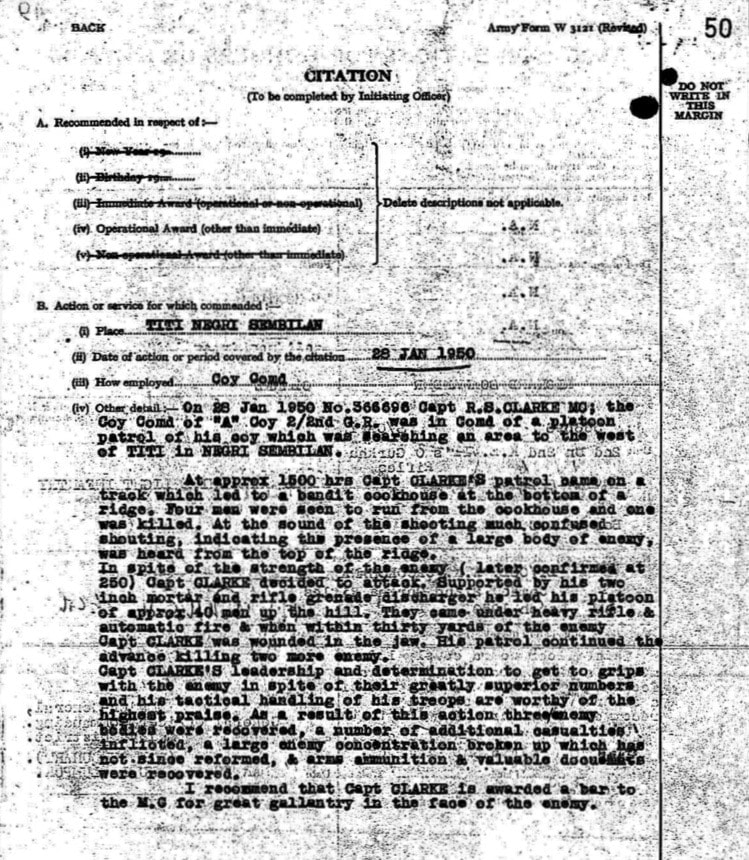

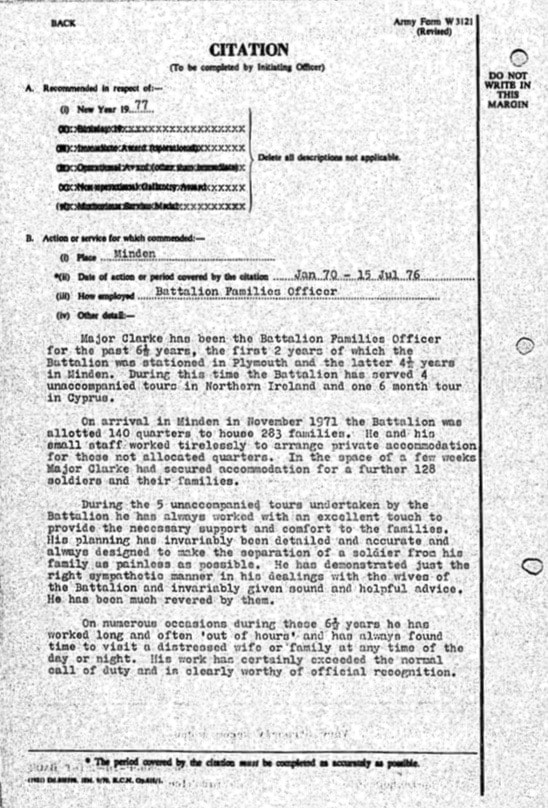

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to Lt. Dicky Clarke, including a photograph of him and some of his colleagues from the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles in the Arakan and the official recommendations for his MC, MC and Bar and the award of the MBE in June 1976. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. Richard Scamander Clarke sadly passed away on the 30th November 2005.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, November 2018. Article first published in the 2nd Gurkha Rifle Newsletter, March 1945.