Lt. Kenneth Ernest Spurlock

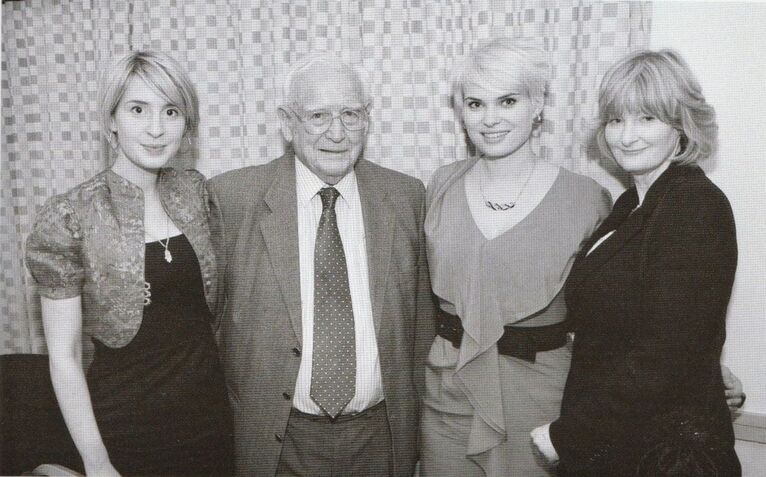

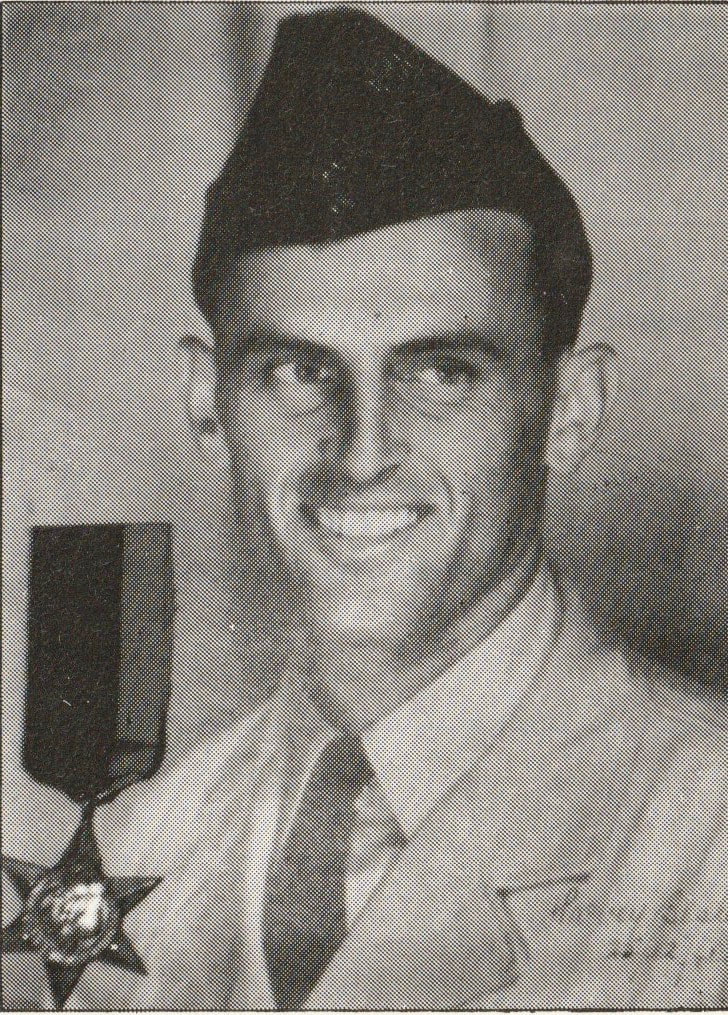

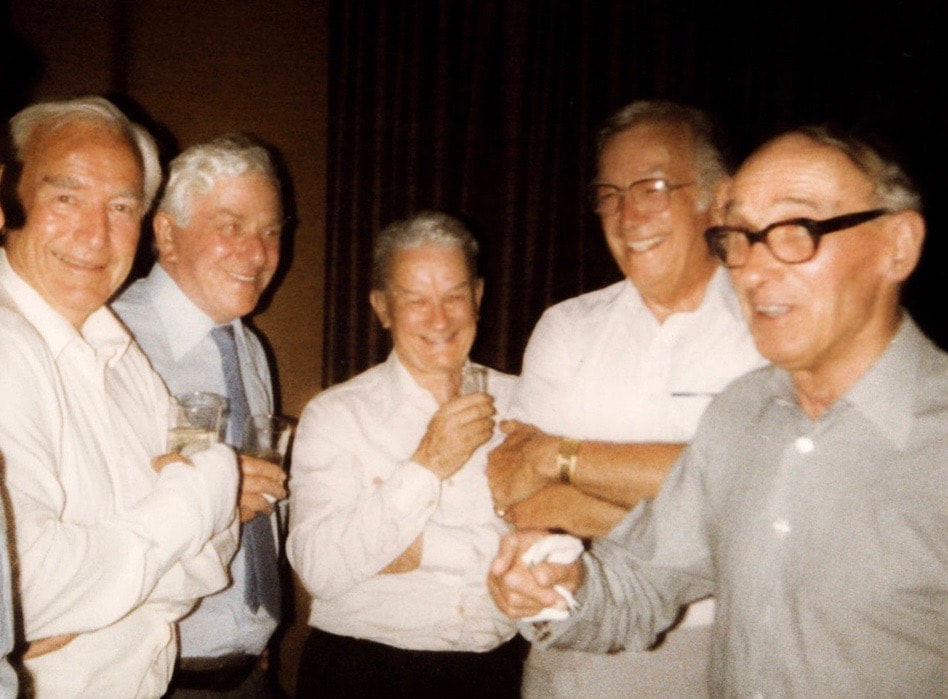

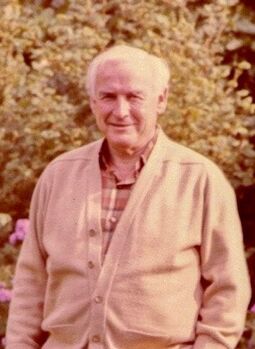

Ken Spurlock in the 1980's.

Ken Spurlock in the 1980's.

Signals and Ciphers are vital elements of any Long Range Penetration force. I was fortunate in having Lt. Spurlock (Signals) and Captain Wilding (Ciphers) in my HQ during Operation Longcloth. The Signals section of a L.R.P.G. carries out an incomparably more important role, than is the case within a normal Brigade. The whole operation depends on good signals and it is the height of folly to pinchback on their provision.

In 1943, Lt. Spurlock did a remarkable job from his rank of Subaltern, especially considering he had no deputy and was at all times vulnerable to enemy fire. His Signals personnel were generally good on the whole but were too few in number. On occasion the Signals section would need to work for 6 hours after the days march when other men could rest up. I would consider an increase of 50% for any following expedition and if these men do not exist in India presently, then they should be sent for from the U.K.

In regards to Lt. Spurlock, he was sadly lost in Burma in April 1943 and with him went many invaluable points and experiences. I am of the hope that he has become a prisoner to the Japanese and may yet survive this war.

Quote from Brigadier O.C. Wingate, June 1943

In 1943, Lt. Spurlock did a remarkable job from his rank of Subaltern, especially considering he had no deputy and was at all times vulnerable to enemy fire. His Signals personnel were generally good on the whole but were too few in number. On occasion the Signals section would need to work for 6 hours after the days march when other men could rest up. I would consider an increase of 50% for any following expedition and if these men do not exist in India presently, then they should be sent for from the U.K.

In regards to Lt. Spurlock, he was sadly lost in Burma in April 1943 and with him went many invaluable points and experiences. I am of the hope that he has become a prisoner to the Japanese and may yet survive this war.

Quote from Brigadier O.C. Wingate, June 1943

I was extremely fortunate to meet Kenneth Spurlock during the Chindit Old Comrades Reunion in June 2009. I only had the chance to speak with him for a few short minutes, but he told me that he had not regretted taking part on Operation Longcloth and had in fact enjoyed the early weeks of the expedition. He did not seem to blame Brigadier Wingate in any way for him being left behind in April 1943 when he fell ill with dysentery. In fact if anything, Ken showed a real warmth towards his former commander.

When remembering his time as a prisoner of was inside Rangoon Jail, he was saddened to recall the loss of so many of his Chindit comrades and the terrible ways in which they had perished. However, even here he could always find a positive angle on which to focus and told me that he had made many life-long friendships during his time in Rangoon and had since travelled to places, including the United States, that perhaps he would never have visited if he had not wanted to meet up once again with these special friends.

NB. As a rather wonderful postscript to the Chindit reunion in 2009, Ken met for the first time Wingate's two granddaughters, Alice and Emily and their mother Holly.

Back in late 2012, I made a second contact with Ken, this time by email. In our conversations we discussed at further length his experiences as a prisoner of war in Rangoon and I explained my interest in the first Wingate expedition and the involvement of my own grandfather. Ken was very generous with his time and told me various stories about the jail, the Japanese guards and the Chindits and other prisoners that had been held there during the war. In return I sent over some of the many documents and papers I had found during my many trips to the National Archives at Kew. It had also been my intention to visit Ken at his home in Monmouthshire, but sadly Ken became ill around this time and our plans fell through.

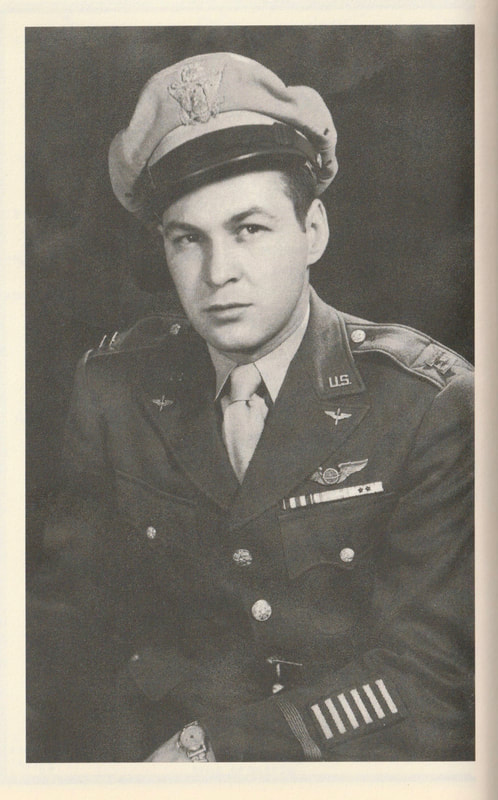

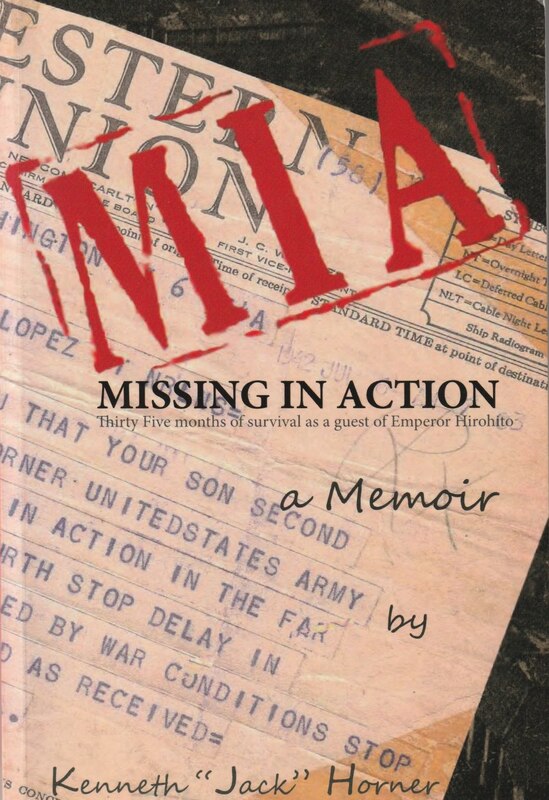

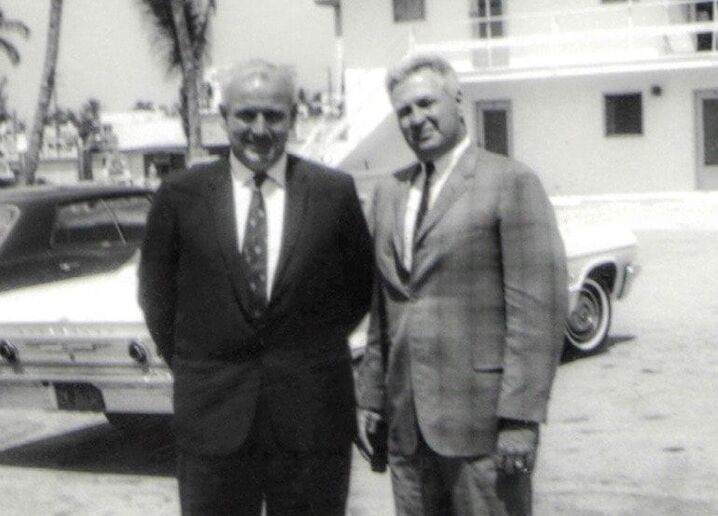

Also around this time, I had been in contact with another former POW from Rangoon Jail, 2nd Lieutenant Kenneth Horner (known to his pals as Jack) of the 7th Bomb Group, United States Army Air Force. He and his daughter Connie, had been working hard in publishing Jack's memoirs of WW2 in the form of the book Missing in Action. Jack and Ken were great friends and had kept in touch after the war and visited each others homes in the UK and the USA. It was through my contact with Jack and Connie Horner, that I learned of Ken Spurlock's sad passing in December 2013 and it was thanks to Connie's kind assistance that I was able to send my condolences to Ken's family:

Dear Gillian (Ken Spurlock's daughter),

I sincerely hope you do not mind me contacting you at this sad time for your family. I have only just heard the terribly sad news about your father's passing, from Kenneth Horner's daughter, Connie. Please accept my heartfelt condolences.

I had met your father at the Chindit Old Comrades Dinner at Walsall in 2009 and only recently been in email contact with him again late last summer. My grandfather was also a Chindit soldier in 1943, but he never returned home that year, dying as a POW in Rangoon Jail. Ken and I were hoping to meet up and swap information when the weather got a little warmer.

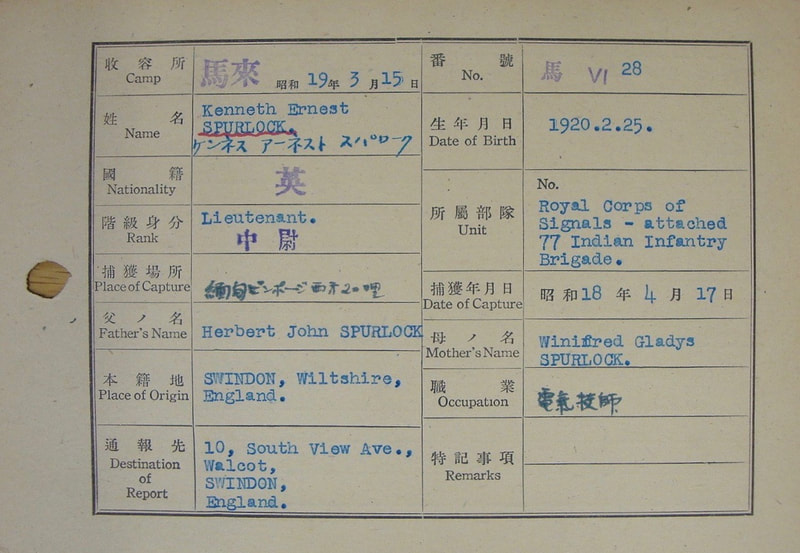

I thought I would send you some photos I have of him, one from 2009 and the other from April 1943 with his dispersal group in the Burmese jungle, including Brigadier Wingate as you will notice. The other document is Ken's Japanese index card which is kept at the National Archives and records all his personal details for his time as a prisoner of war.

I hope these images will be of some comfort and interest. Your father was a very loyal and brave man and it seems to me, always tried his best to help people whenever he could. He was a wonderful gentleman.

Kindest regards to all your family. Steve Fogden.

I was pleased to receive the following reply:

Dear Steve

Please accept my apologies for this late reply. I was delighted to receive your kind message and interesting attachments. I had seen some of them before but certainly not the Japanese index card. I had chanced upon your website just last year and had printed out a big chunk of information for Dad and others to read.

As a family we loved talking to Dad about his wartime adventures and my sister and I always said one day we must write all of it down, but of course we never did. His tales of India and Burma always fascinated me and since 1989 my husband and I have spent our yearly holidays in India travelling to many parts including places mentioned by Dad. We once went to Mhow where Dad did his Signal’s training, it was a lovely place.

I also enjoyed meeting his POW friends such as Jack Horner, his American friend. Also in later years I used to go with my parents on a yearly visit to London and we usually met up with Willie Wilding and I enjoyed their reminiscing and banter. Thank you again for getting in touch and I will keep visiting your brilliant website for any further updates. I am so sorry you did not get to meet Dad again, I know he would have loved to chat to you and tried to remember any snippets of information.

With best wishes to you and your family. Gillian

When remembering his time as a prisoner of was inside Rangoon Jail, he was saddened to recall the loss of so many of his Chindit comrades and the terrible ways in which they had perished. However, even here he could always find a positive angle on which to focus and told me that he had made many life-long friendships during his time in Rangoon and had since travelled to places, including the United States, that perhaps he would never have visited if he had not wanted to meet up once again with these special friends.

NB. As a rather wonderful postscript to the Chindit reunion in 2009, Ken met for the first time Wingate's two granddaughters, Alice and Emily and their mother Holly.

Back in late 2012, I made a second contact with Ken, this time by email. In our conversations we discussed at further length his experiences as a prisoner of war in Rangoon and I explained my interest in the first Wingate expedition and the involvement of my own grandfather. Ken was very generous with his time and told me various stories about the jail, the Japanese guards and the Chindits and other prisoners that had been held there during the war. In return I sent over some of the many documents and papers I had found during my many trips to the National Archives at Kew. It had also been my intention to visit Ken at his home in Monmouthshire, but sadly Ken became ill around this time and our plans fell through.

Also around this time, I had been in contact with another former POW from Rangoon Jail, 2nd Lieutenant Kenneth Horner (known to his pals as Jack) of the 7th Bomb Group, United States Army Air Force. He and his daughter Connie, had been working hard in publishing Jack's memoirs of WW2 in the form of the book Missing in Action. Jack and Ken were great friends and had kept in touch after the war and visited each others homes in the UK and the USA. It was through my contact with Jack and Connie Horner, that I learned of Ken Spurlock's sad passing in December 2013 and it was thanks to Connie's kind assistance that I was able to send my condolences to Ken's family:

Dear Gillian (Ken Spurlock's daughter),

I sincerely hope you do not mind me contacting you at this sad time for your family. I have only just heard the terribly sad news about your father's passing, from Kenneth Horner's daughter, Connie. Please accept my heartfelt condolences.

I had met your father at the Chindit Old Comrades Dinner at Walsall in 2009 and only recently been in email contact with him again late last summer. My grandfather was also a Chindit soldier in 1943, but he never returned home that year, dying as a POW in Rangoon Jail. Ken and I were hoping to meet up and swap information when the weather got a little warmer.

I thought I would send you some photos I have of him, one from 2009 and the other from April 1943 with his dispersal group in the Burmese jungle, including Brigadier Wingate as you will notice. The other document is Ken's Japanese index card which is kept at the National Archives and records all his personal details for his time as a prisoner of war.

I hope these images will be of some comfort and interest. Your father was a very loyal and brave man and it seems to me, always tried his best to help people whenever he could. He was a wonderful gentleman.

Kindest regards to all your family. Steve Fogden.

I was pleased to receive the following reply:

Dear Steve

Please accept my apologies for this late reply. I was delighted to receive your kind message and interesting attachments. I had seen some of them before but certainly not the Japanese index card. I had chanced upon your website just last year and had printed out a big chunk of information for Dad and others to read.

As a family we loved talking to Dad about his wartime adventures and my sister and I always said one day we must write all of it down, but of course we never did. His tales of India and Burma always fascinated me and since 1989 my husband and I have spent our yearly holidays in India travelling to many parts including places mentioned by Dad. We once went to Mhow where Dad did his Signal’s training, it was a lovely place.

I also enjoyed meeting his POW friends such as Jack Horner, his American friend. Also in later years I used to go with my parents on a yearly visit to London and we usually met up with Willie Wilding and I enjoyed their reminiscing and banter. Thank you again for getting in touch and I will keep visiting your brilliant website for any further updates. I am so sorry you did not get to meet Dad again, I know he would have loved to chat to you and tried to remember any snippets of information.

With best wishes to you and your family. Gillian

Ken was born on the 25th February 1920 in Swindon, Wiltshire and was the son of Herbert John and Winifred Gladys Spurlock. His future Army career as a Signals Officer was as a direct result of his working with the British Post Office as an Inspector in the Engineering Department from 1938. Ken enlisted into the Royal Corps of Signals on the 20th July 1940 and was commissioned from Officer Cadet to 2nd Lieutenant on the 14th October 1941. His Army number was recorded as 212065.

Ken had been sent overseas to India, where he was based at Mhow, a town in Madhya Pradesh State. During his conversations with author, Phil Chinnery, Ken recalled how he had come to join up with 77th Brigade in the late summer of 1942. From the pages of Wingate's Lost Brigade:

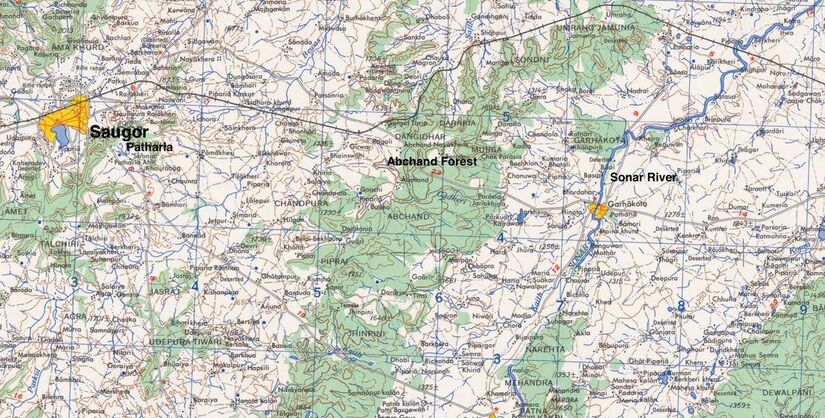

Lieutenant Ken Spurlock, Wingate's new Signals Officer arrived straight from a commando course held at Ambala, where signallers were being trained to work for 'V' Force amongst the Shan tribesmen of Burma. He had never heard of 77 Indian Infantry Brigade and was most surprised when he stepped off the train at Abchand near Saugor to find that instead of a proper railway station there was just a dusty shack.

A soldier was working nearby, stripped to the waist and wearing some sort of Australian hat. He asked Spurlock, 'Where the bloody hell are you going?' Ignoring the lack of respect due to an officer, Spurlock informed him that he was looking for 77 Brigade. `You've got a bloody long walk then, boy!' replied the soldier, pointing to a muddy track leading into the jungle. When Spurlock found Brigade Headquarters there was just a handful of tents, and four or five officers and a score of other ranks scurrying around.

Spurlock was directed to Wingate's tent by the Brigade Major. He straightened his uniform, coughed and pushed his way through the tent flap. Behind a trestle table sat Brigadier Orde Wingate, stark naked with the exception of his boots, wearing a Wolsey helmet, with a fly swat in his hand. `Are you Spurlock?' the Brigadier enquired. When the perspiring officer replied in the affirmative, Wingate shuffled the papers and maps on his desk and handed over a sheaf of papers. 'The success of this operation depends on you. Take these plans away and look at them. If you think that the signals will not work we may just as well pack up and go home.'

Spurlock was taken to a tent containing a table and a chair where he sat down and began to read. The plans detailed Wingate's ideas on long-range penetration and described the composition of the columns, the equipment and the tactics to be used. From the signals point of view the Brigadier would need to communicate with each of the units in the field, as well as headquarters and the RAF in India. Three types of wireless transmitters would be required, together with trained operators who could also repair the sets as well as work them; all the problems involved in sending signals from valleys as well as mountains had to be surmounted.

Finally, Spurlock walked back to Wingate's tent and handed the plans back to him. `Given the right equipment, sir, I think we can do it'. `Good man,' smiled Wingate as he rose from his desk. Now follow me.' Wingate strode off to show Spurlock where the battalions were going to be camped when they arrived. After walking for a mile or so they came to a fast-flowing river, about 40 yards across. Wingate kicked off his boots and plunged into the water, still wearing his helmet. Without hesitation Spurlock did the same and swam steadily to the other side. They climbed out of the water and inspected the clearing where some of the infantry would set up camp.

Then Wingate turned around and started to swim back to the far side. By the time the pair had got across again they were quite a way from their boots and walked back to reclaim them. It dawned on Spurlock that this had been a test and he had apparently passed with flying colours. If he had refused to follow the Brigadier into the river he would probably have been returned to his unit. After that he could not put a foot wrong and eventually became quite close to Wingate, learning first hand about his adventures in other campaigns.

Seen below is a map of the area around the Chindit training camps of Saugor and Abchand located in the Central Provinces of India. The map shows the railway line and the Sonar River, which was most likely the river mentioned by Ken Spurlock in the above narrative. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Ken was posted to Brigade Head Quarters during Operation Longcloth and was almost always in the company of his commander, Brigadier Wingate. Brigade HQ, alongside Chindit Columns Nos. 7 and 8 crossed the Chindwin River and ventured in to enemy held territory close to the village of Tonhe on the 15th February 1943.

The Brigade then moved on to a pre-arranged supply drop at a place called Tonmakeng. Then passed over the sparsely inhabited area of the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment, before dropping down into the valleys around Banmauk. Ken Spurlock and his signallers were successful in most of their radio and communications work during this initial period. However, after crossing the Irrawaddy in mid-March and pushing on further east, it became more and more difficult to contact Rear Base and supply drops became more precarious to organise and carry out. Added to this, the Brigade were now too far east for the RAF Dakota aircraft sent to drop their supplies to enjoy the security of fighter escorts which also put pressure on re-supply. On the 24th March, having succeeded in their aims to disrupt and confuse the Japanese in the area, Wingate was instructed by General Head Quarters to return his troops to India.

To read more about the men who worked for Ken Spurlock on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link:

Signalman Arthur Nicholls and the RCOS Draft from China

The story recounting Brigadier Wingate's dispersal back to India in April 1943 has been featured several times on these website pages. To read more about this journey please click on the following links:

Wingate's Journey Home

Signalman Eric Hutchins

Flight-Lieutenant Albert Tooth

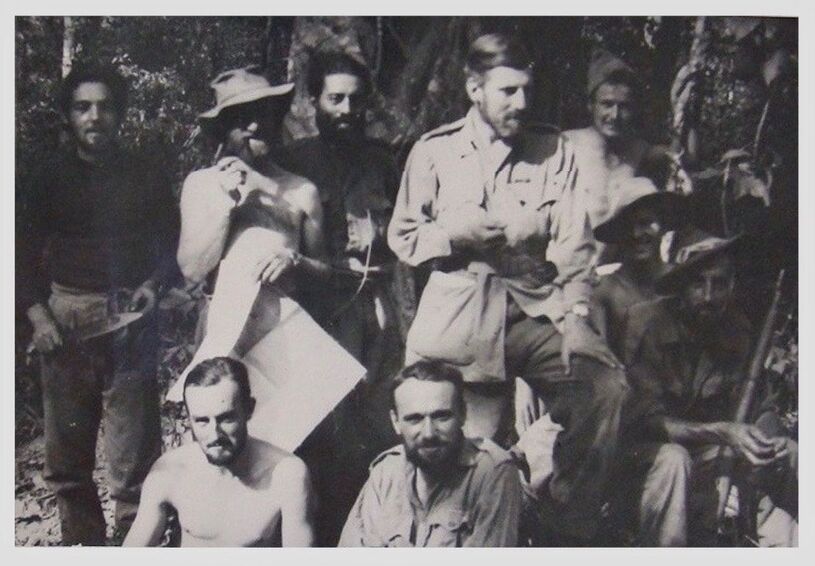

Seen below is a rather special photograph of Brigadier Wingate and part of his dispersal party, which was taken in early April 1943, as the group were about to make a second attempt to cross the Irrawaddy River on their journey back to India. The others shown are, from left to right: Back Row- RAF Sergeant Arthur Willshaw, Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore, Captain Motilal Katju, Brigadier Wingate, Ken Spurlock. Front Row- RAF Flight Lieutenant Albert Tooth, Lt. Lewis Rose, RAF Sergeant Alan Fidler and Major J. B. Jeffries, 142 Commando. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

The Brigade then moved on to a pre-arranged supply drop at a place called Tonmakeng. Then passed over the sparsely inhabited area of the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment, before dropping down into the valleys around Banmauk. Ken Spurlock and his signallers were successful in most of their radio and communications work during this initial period. However, after crossing the Irrawaddy in mid-March and pushing on further east, it became more and more difficult to contact Rear Base and supply drops became more precarious to organise and carry out. Added to this, the Brigade were now too far east for the RAF Dakota aircraft sent to drop their supplies to enjoy the security of fighter escorts which also put pressure on re-supply. On the 24th March, having succeeded in their aims to disrupt and confuse the Japanese in the area, Wingate was instructed by General Head Quarters to return his troops to India.

To read more about the men who worked for Ken Spurlock on Operation Longcloth, please click on the following link:

Signalman Arthur Nicholls and the RCOS Draft from China

The story recounting Brigadier Wingate's dispersal back to India in April 1943 has been featured several times on these website pages. To read more about this journey please click on the following links:

Wingate's Journey Home

Signalman Eric Hutchins

Flight-Lieutenant Albert Tooth

Seen below is a rather special photograph of Brigadier Wingate and part of his dispersal party, which was taken in early April 1943, as the group were about to make a second attempt to cross the Irrawaddy River on their journey back to India. The others shown are, from left to right: Back Row- RAF Sergeant Arthur Willshaw, Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore, Captain Motilal Katju, Brigadier Wingate, Ken Spurlock. Front Row- RAF Flight Lieutenant Albert Tooth, Lt. Lewis Rose, RAF Sergeant Alan Fidler and Major J. B. Jeffries, 142 Commando. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

From the book, Wingate's Raiders, by Charles J. Rolo:

One British Lieutenant, a Signals officer and a key man, worn out with dysentery, just couldn't march another step and dropped to the side of the track muttering, " Well, I've had it." Wingate halted and talked to him gently for four or five minutes. When he turned to go the Lieutenant rose shakily to his feet and saluted with a cheery smile. He might have been saying good-bye to his girl friend at the Savoy on the eve of a big do. Then he lay down at the foot of a tall teak-tree, and the dust settled over him as the column marched on.

After successfully re-crossing the Irrawaddy, Wingate's group made steady westward progress over the next ten days. The men purposely avoided local villages and rarely used well-known tracks and paths. The down side to this practice was that the group were almost always without food and water and many of the party began to struggle physically with their ordeal.

Once more, from the pages of Phil Chinnery's book, Wingate's Lost Brigade:

For the next several days they marched through the Mangin Mountains between the railway and the escarpment. Their boots began to fall apart and diarrhoea, dysentery and jungle sores began to take a heavy toll. Men began to fall by the side of the track and there was nothing that could be done for them. On 16th April, Lieutenant Ken Spurlock, who had been suffering from dysentery since eating mule meat that was 'off' and had been getting weaker as the days passed, finally had to fall out near Kyingi. Amazingly Wingate took the decision to wait and see if Spurlock would recover enough to carry on. Forty-eight hours later, with Spurlock still unable to continue, Wingate reluctantly ordered his party to move on. He later wrote to Spurlock's father:

I was one of the last people to see your son in Burma. He had been throughout the Campaign absolutely invaluable to me as my principal Signals Officer. As you may well imagine the success of the campaign was largely due to the excellent signals work of your son and his subordinates. It was for this reason I decided to keep him with me in my own party when we broke up into small groups in order to regain India.

To start with all went well, we re-crossed the Irrawaddy and were almost in sight of home when to my great unhappiness your son announced his inability to continue. He had always been so strong I had not realised that the greatly reduced diet had told more heavily on his big body than on the smaller ones. We waited two days in the hope he would regain strength, and then were compelled in the interest of the whole party to set out again. He was suffering from aggravated diarrhoea and the wait did nothing to improve matters.

We had provided him with food, money and a compass in case this should happen. I had a long talk with him that morning about the advisability of surrendering to the Japanese. He was against this but I pointed out to him that he could escape when he had regained his strength. As he was quite incapable of self-defence, there was no question of dishonour. I cannot say, however, that he appeared convinced by my arguments. For the rest I told him to wait a day after we had passed, then to enter the nearest village where he could have a bed and be looked after. I expect he did this, and hope that he was either taken care of by kindly Burmans or that he is a prisoner in the hands of the Japanese.

Chinnery's book continues:

Wingate was unaware of it at the time, but Spurlock did exactly as he was advised — he waited for a day and then set off in search of a friendly village. He did not know it but the Japanese were offering a reward to the villagers for bringing in Wingate's men, dead or alive. Suddenly a group of natives appeared on the track and, seeing Spurlock in front of them, brought up their crossbows and let fly at the startled officer. Spurlock took to his heels and dived behind cover, drawing his revolver as he did so. He aimed at one of the attackers and pulled the trigger, looking quickly around him as the native clutched at his stomach and fell to the ground. As the other attackers sought cover, Spurlock ran back into the jungle and finally lost his pursuers.

Eventually Spurlock found his way to a village and saw what he thought was a group of friendly natives sitting around a fire, dressed in loincloths. Smiling he walked closer only to discover that they were Japanese soldiers. One of them jumped to his feet and ran into a hut, returning with his rifle and bayonet fixed. He thrust the weapon at Spurlock and ran the bayonet through his chest, under his left armpit and then struck him on the head with the rifle butt. He collapsed in a heap on the ground.

When Spurlock came to he opened his eyes very slowly and discovered that he was peering down the barrel of a machine gun. He was in fact being used as the top row of sandbags on a machine gun emplacement. The Japanese must have thought that more men were coming along behind Spurlock and took cover ready to repel an attack. Half an hour later they must have decided that he was alone, dragged him upright and bound his arms behind his back. The other end of the rope was tied around his neck, so that if he struggled he would slowly throttle himself. Finally subdued, the officer was sat on the ground and his captors fed him. Spurlock decided that the front line troops were not so bad after all. His troubles would really start once he reached the prisoner of war camp in Rangoon.

Wingate was unaware of it at the time, but Spurlock did exactly as he was advised — he waited for a day and then set off in search of a friendly village. He did not know it but the Japanese were offering a reward to the villagers for bringing in Wingate's men, dead or alive. Suddenly a group of natives appeared on the track and, seeing Spurlock in front of them, brought up their crossbows and let fly at the startled officer. Spurlock took to his heels and dived behind cover, drawing his revolver as he did so. He aimed at one of the attackers and pulled the trigger, looking quickly around him as the native clutched at his stomach and fell to the ground. As the other attackers sought cover, Spurlock ran back into the jungle and finally lost his pursuers.

Eventually Spurlock found his way to a village and saw what he thought was a group of friendly natives sitting around a fire, dressed in loincloths. Smiling he walked closer only to discover that they were Japanese soldiers. One of them jumped to his feet and ran into a hut, returning with his rifle and bayonet fixed. He thrust the weapon at Spurlock and ran the bayonet through his chest, under his left armpit and then struck him on the head with the rifle butt. He collapsed in a heap on the ground.

When Spurlock came to he opened his eyes very slowly and discovered that he was peering down the barrel of a machine gun. He was in fact being used as the top row of sandbags on a machine gun emplacement. The Japanese must have thought that more men were coming along behind Spurlock and took cover ready to repel an attack. Half an hour later they must have decided that he was alone, dragged him upright and bound his arms behind his back. The other end of the rope was tied around his neck, so that if he struggled he would slowly throttle himself. Finally subdued, the officer was sat on the ground and his captors fed him. Spurlock decided that the front line troops were not so bad after all. His troubles would really start once he reached the prisoner of war camp in Rangoon.

So near and yet so very far!

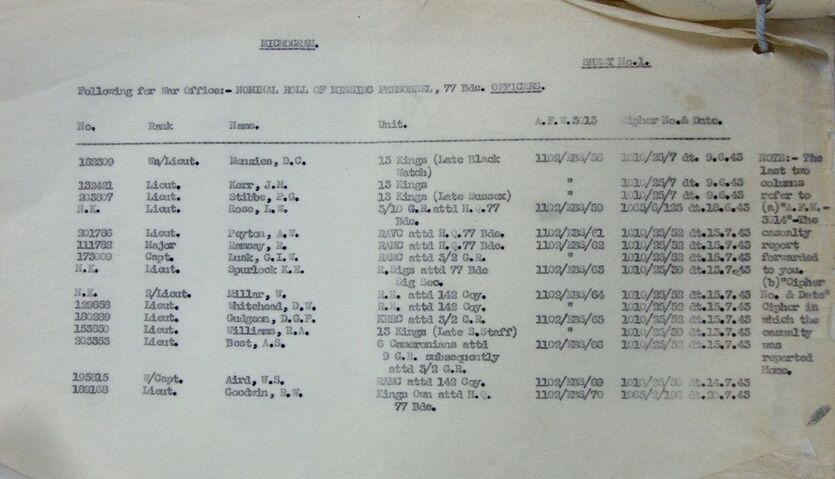

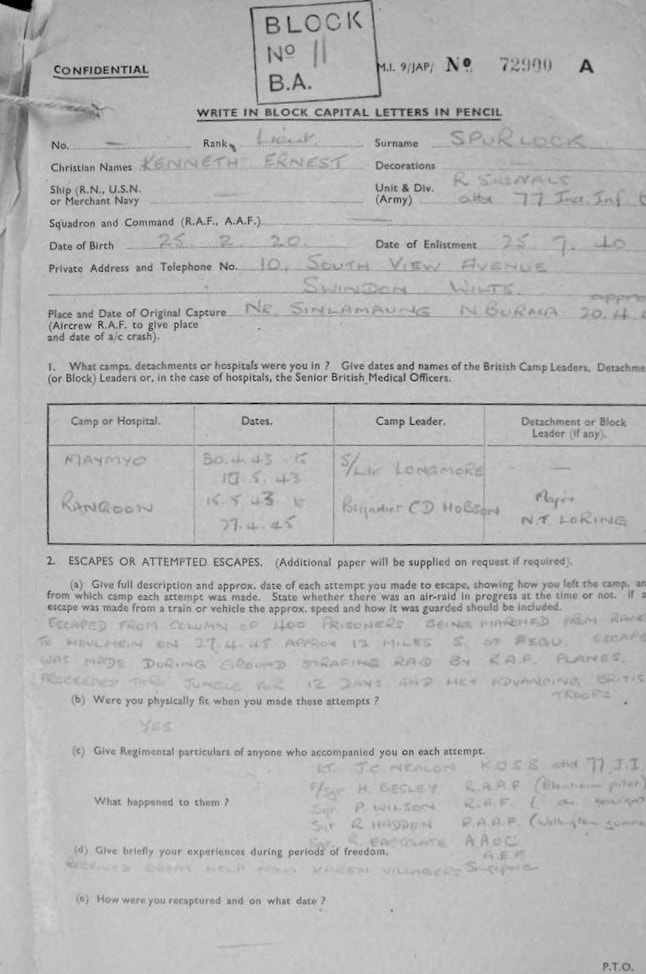

According to Ken Spurlock's POW index card, he was captured between the 17th and 20th April 1943, near the Burmese town of Sinlamaung, which was located just 30 miles from the Chindwin River and the potential safety of Allied held territory. There is a document, in the form of a missing listing for officers from Operation Longcloth, that suggests he may have been held by the Japanese in the first instance at the large concentration camp located at Maymyo. This was the camp where captured Chindits first learned the harsh nature of Japanese martial discipline and where they first tasted the more ugly nature of their captors.

To read more about the Maymyo Camp, please click on the following link: Maymyo Concentration Camp

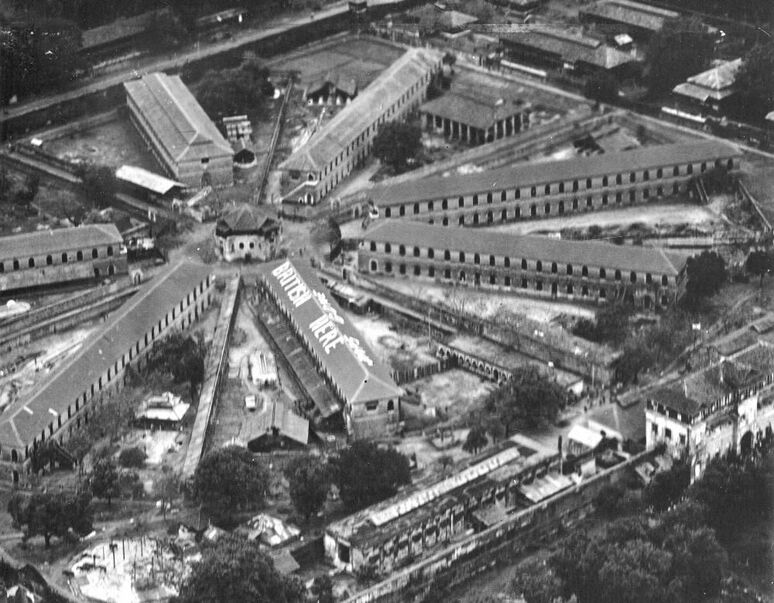

In time, all Chindit POWs were transported south to Rangoon where they were deposited into Block 6 of the city jail. Around 250 Chindits were present at the jail by June 1943, but many were in such poor physical condition that they began to perish at an alarming rate. As one of the more senior Chindit officers in Rangoon Jail, Ken Spurlock was responsible for the well-being and behaviour of the junior ranked soldiers. One document shows him as officer in charge of around 50 men in Block 6 and also as the Treasurer elect for holding and administering the monies given to the prisoners by the Japanese guards in lieu of wages.

As already mentioned, it was at Rangoon that Ken first met 2nd Lieutenant Kenneth (Jack) Horner of the United States Army Air Force. The two men were brought together by the senior Medical Officer in the prison, Major Raymond Ramsay, who required their various skills in the manufacturing of medical equipment from the scant materials available within the jail. It was whilst working together for Major Ramsay, that Ken and Jack forged a friendship that would last for almost 70 years.

Here is an extract from Jack Horner's book, entitled 'MIA' (Missing in Action), telling the story of how he and Ken Spurlock helped manufacture a medical instrument for Raymond Ramsay:

"Major Ramsey asked us to make a troche cannula. First of all, we didn't know what a troche cannula was and besides that, we couldn't really make one with the tools available.

Major Ramsey explained to us that it was a medical device used to pierce body cavities. It consists of a small channel with a plunger through it. The plunger and the channel together have a three cornered point. If he had one he could help all the beri beri patients by draining the excess water from their testicles. "It doesn't have to be perfect" he said, "however it has to be small and extremely sharp so I can pierce the skin."

Ken Spurlock and I agreed to try. A tin can was the only metal we could think of that would be thin enough to make the channel and I hadn't seen one in over two years. We told the prison work parties to look out for one and in two days we had several cans to work with.

Fabricating the channel, as we designed it, required a blank with dimensions far beyond our ability to calculate. We envisioned a small diameter wire with the metal wrapped around it. The metal would meet in a butt joint so the finished channel would have a crack the length of the tube which was 2 inches long.

We cut several half inch wide pieces of metal and practised several ways to end up with a minimum space at the butt joint. After several attempts we succeeded in getting a tube through which a wire could slide rather tightly. Major Ramsey monitored our progress daily and insisted we hurry. His impatience convinced us that he believed the device would help alleviate the pain and discomfort of some of his patients.

Finally, the only thing that remained to complete the device was to make a handle on one end and a very sharp point on the other. To create the point we tried all sorts of abrasives: the concrete work floor, the brick wall between the compounds and the wall of the main building. Of course, it was slow and painstaking work, yet we succeeded in making a long sharp point that could easily puncture human skin and enter a body cavity. Dr Ramsey used it and said it was as effective as any he had used in his own private practice."

To read more about the Maymyo Camp, please click on the following link: Maymyo Concentration Camp

In time, all Chindit POWs were transported south to Rangoon where they were deposited into Block 6 of the city jail. Around 250 Chindits were present at the jail by June 1943, but many were in such poor physical condition that they began to perish at an alarming rate. As one of the more senior Chindit officers in Rangoon Jail, Ken Spurlock was responsible for the well-being and behaviour of the junior ranked soldiers. One document shows him as officer in charge of around 50 men in Block 6 and also as the Treasurer elect for holding and administering the monies given to the prisoners by the Japanese guards in lieu of wages.

As already mentioned, it was at Rangoon that Ken first met 2nd Lieutenant Kenneth (Jack) Horner of the United States Army Air Force. The two men were brought together by the senior Medical Officer in the prison, Major Raymond Ramsay, who required their various skills in the manufacturing of medical equipment from the scant materials available within the jail. It was whilst working together for Major Ramsay, that Ken and Jack forged a friendship that would last for almost 70 years.

Here is an extract from Jack Horner's book, entitled 'MIA' (Missing in Action), telling the story of how he and Ken Spurlock helped manufacture a medical instrument for Raymond Ramsay:

"Major Ramsey asked us to make a troche cannula. First of all, we didn't know what a troche cannula was and besides that, we couldn't really make one with the tools available.

Major Ramsey explained to us that it was a medical device used to pierce body cavities. It consists of a small channel with a plunger through it. The plunger and the channel together have a three cornered point. If he had one he could help all the beri beri patients by draining the excess water from their testicles. "It doesn't have to be perfect" he said, "however it has to be small and extremely sharp so I can pierce the skin."

Ken Spurlock and I agreed to try. A tin can was the only metal we could think of that would be thin enough to make the channel and I hadn't seen one in over two years. We told the prison work parties to look out for one and in two days we had several cans to work with.

Fabricating the channel, as we designed it, required a blank with dimensions far beyond our ability to calculate. We envisioned a small diameter wire with the metal wrapped around it. The metal would meet in a butt joint so the finished channel would have a crack the length of the tube which was 2 inches long.

We cut several half inch wide pieces of metal and practised several ways to end up with a minimum space at the butt joint. After several attempts we succeeded in getting a tube through which a wire could slide rather tightly. Major Ramsey monitored our progress daily and insisted we hurry. His impatience convinced us that he believed the device would help alleviate the pain and discomfort of some of his patients.

Finally, the only thing that remained to complete the device was to make a handle on one end and a very sharp point on the other. To create the point we tried all sorts of abrasives: the concrete work floor, the brick wall between the compounds and the wall of the main building. Of course, it was slow and painstaking work, yet we succeeded in making a long sharp point that could easily puncture human skin and enter a body cavity. Dr Ramsey used it and said it was as effective as any he had used in his own private practice."

Seen below is a partial listing of those officers from Operation Longcloth known to be missing in action, including Lt. Kenneth Spurlock of the Royal Corps of Signals. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page. To read more about the Chindits held at Rangoon Jail and their prisoner of war experiences, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

After two arduous years inside Rangoon Jail and having lost many Chindits to the ravages of disease, starvation and the brutality of their captors, on the 23rd April 1945 an order was given for the fittest men still present in the jail to prepare themselves to leave Rangoon. The Japanese decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 men, including Lt. Spurlock were classified as fit to march and on the 24th April were marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and ill comrades.

Ken Spurlock's former comrade from Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters in 1943, Lt. Willie Wilding was also amongst the marchers that day:

We set out from Rangoon Jail on the 25th April. My belongings consisted of a small bundle wrapped in my half blanket. I slung this on a pole with a similar bundle belonging to John Wild of the Lancashire Fusiliers. We had proposed to carry it on our shoulders but, as John is 6' (at least) and I am not, the bundles kept slipping down to my end, so we carried the pole in our hands instead.

We had left the seriously ill behind. We felt that there was little hope for them and they might be killed, but in the event they all survived, at least until Rangoon was relieved. That first day we marched fourteen odd miles to the outskirts of Mingaladon. This was quite a severe march for us especially with bare feet. I think I weighed about seven stone at the time. We spent the rest of the night and the whole of the next day there. Our own cooks produced the usual meal of boring old rice.

Two nights later we marched to a point just south of Pegu. I don't know how far but would suppose about fifteen miles. We were much troubled by Allied aircraft, which strafed everything that moved. Finally, just before dawn, we went into cover. I fitted nicely into deep ruts gouged out by the wheels of bullock carts and it was exciting but scary to see Spitfires flying overhead.

Towards the end of the afternoon, Ken Spurlock, another former Chindit officer and about thirty other men pushed off. I am not sure if he really should have done. We were still going north, i.e., towards our own troops - the Japs might well have slain us all because of this escape. Ken must some day, tell the story of his group's adventures. The stories I have been told were most amusing and thankfully all this group survived. It is all very well for me to moralise about the rights and wrongs of escaping - the fact is that I was asked to join a similar party being organised by Major Loring. I accepted, but thought we should have taken some quinine from the Medical Officer's stores, because we were taking Joe Edmunds, and he was subject to bouts of malaria. I went off to pinch some but on my return found that we were all ready to move off. Surprisingly, the Japs seemed neither surprised nor upset by Ken Spurlock's departure.

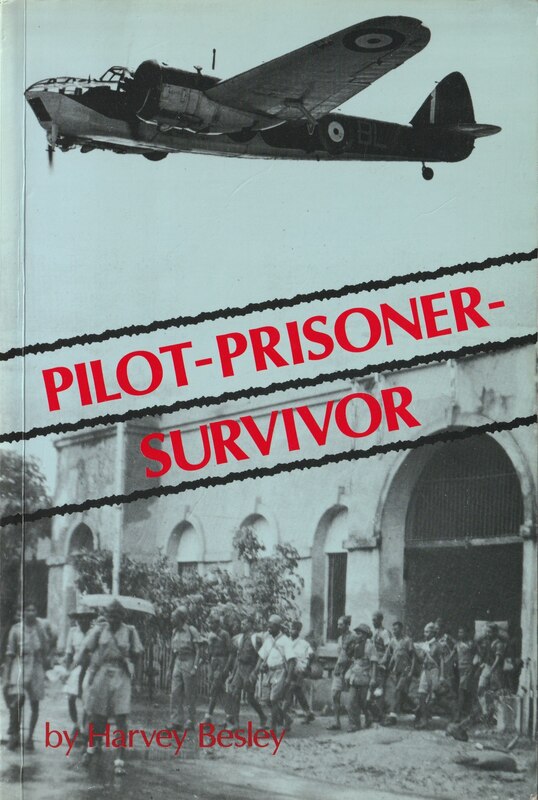

As mentioned by Willie Wilding, by the third day of marching, many prisoner's thoughts were turning to escape. Australian Pilot, Harvey Besley and three other Australians, Douglas Eastgate, Peter Wilson and Ronald Haddon, had worked out how they were going to leave the main party at the next meal time halt. They had watched the Japanese guards closely over the past few days and noticed a weakness in their patrols during rest periods. Another soldier, Chindit John Nealon, who had been a member of No. 1 Column on Operation Longcloth was asked to join them, as he was known to possess many of the skills needed for the break-away party to succeed in their quest for freedom. It was Lt. Nealon who insisted that Ken Spurlock join the group, making six in all. Ken's best friend, American Jack Horner was also asked to join the group, but by this time he was suffering badly with sore and blistered feet and knew he would seriously curtail the group's chances of success. Jack remained behind, but promised the escapees that he would cover for their absence in the meantime.

Taking their opportunity as planned, the six men quietly disappeared into the jungle scrub close to where the main group were eating their accustomed meal of boiled rice. With Lt. Nealon in charge, they moved as quickly as possible in a westward direction, putting as much distance as they could between themselves and their former captors. As dusk fell, the party settled down for the night in a small bamboo copse and attempted to get some sleep.

After three days march and having exhausted the small amount of food they had managed to collect together before their escape, the group decided to visit a Burmese village for new rations and water. Fortunately the villagers were friendly towards the party and agreed to feed them and provide a guide to take them on to the next village which was known to be extremely pro-British in its outlook. After receiving assistance from several friendly villages along the way and having been on the run for just over a week, Ken Spurlock and his fellow escapees bumped into a RAF outpost camp, having unknowingly drifted into Allied held territory and were liberated. It would amuse the six escapees later, to discover that if they had remained with the main party of POW's on the Pegu Road, liberation would have come six days earlier. You win some and you lose some I suppose.

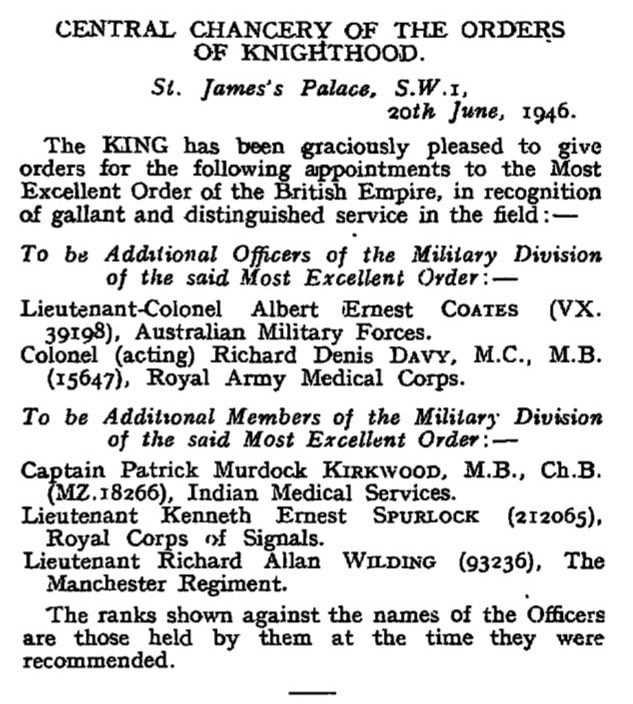

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including Ken Spurlock's POW index card and the London Gazette entry recording his award of an MBE, for his gallant service during his time on Operation Longcloth and as a prisoner of war. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The men liberated from the Pegu March as it was to become known, were generally flown out of Burma aboard United States Dakotas and sent straight to hospital in India. Those POW's still remaining in Rangoon Jail were liberated in early May 1945 and were shipped out of Rangoon aboard HMHS Karapara and taken to hospital at Calcutta. After a lengthy period of hospitalisation, followed by several weeks rest and recuperation in the hill-stations of northern India, most of the men returned to their former units and awaited repatriation to the United Kingdom or the USA.

It is not known exactly when Ken Spurlock returned home to Swindon, but we do know that he married his sweetheart, Kathleen Loveday in early 1946. After the war, Ken returned to his work with the Post Office Telecommunications Department and would continue to work in the industry for many years. He would also have witnessed the administrative changes that eventually took telecommunications away from the GPO and the ultimate formation of BT in 1981 and the privatisation of the same company in 1984.

Jack Horner had also returned home after the war and had started a young family of his own, ultimately settling down in the Floridian city of Tampa. He recalled his ongoing relationship with Ken Spurlock in his book, Missing in Action:

Ken Spurlock was missing when we had roll call at dusk on the 28th of April 1945 along with ten other men. I later learned that Ken and five or six British Other Ranks were in the jungle for seven days before being led back to the Pegu Road by friendly villagers. After the war, Ken went back to school and graduated as an electrical engineer and joined the British Telephone and Postal Department. In 1960 he was given a sabbatical so that he could serve as Managing Director of the Jamaican Telephone Company. With my wife and two youngest children, I visited him and his family in Kingston. He returned to Britain and became Chairman of the Wales Telephone Company. Over the years we have met at least a dozen times in Europe and in the United States. On several occasions Don Humphrey (another USAAF POW at Rangoon Jail) joined us. Amazingly, Ken and I have seen and talked to each other recently using a fantastic electronic software program called Skype.

It is not known exactly when Ken Spurlock returned home to Swindon, but we do know that he married his sweetheart, Kathleen Loveday in early 1946. After the war, Ken returned to his work with the Post Office Telecommunications Department and would continue to work in the industry for many years. He would also have witnessed the administrative changes that eventually took telecommunications away from the GPO and the ultimate formation of BT in 1981 and the privatisation of the same company in 1984.

Jack Horner had also returned home after the war and had started a young family of his own, ultimately settling down in the Floridian city of Tampa. He recalled his ongoing relationship with Ken Spurlock in his book, Missing in Action:

Ken Spurlock was missing when we had roll call at dusk on the 28th of April 1945 along with ten other men. I later learned that Ken and five or six British Other Ranks were in the jungle for seven days before being led back to the Pegu Road by friendly villagers. After the war, Ken went back to school and graduated as an electrical engineer and joined the British Telephone and Postal Department. In 1960 he was given a sabbatical so that he could serve as Managing Director of the Jamaican Telephone Company. With my wife and two youngest children, I visited him and his family in Kingston. He returned to Britain and became Chairman of the Wales Telephone Company. Over the years we have met at least a dozen times in Europe and in the United States. On several occasions Don Humphrey (another USAAF POW at Rangoon Jail) joined us. Amazingly, Ken and I have seen and talked to each other recently using a fantastic electronic software program called Skype.

Ken Spurlock joined the Glamorgan Branch of the Burma Star Association in 1971 and was a keen attendee of both the Chindit Old Comrades and Rangoon Jail POW reunions in the years after the war, keeping in regular touch with friends such as Willie Wilding. He was a member of the local Rotary Club and worked with various charities in the Cardiff area, including those involved in the re-housing of the long-term homeless.

As mentioned at the very beginning of this narrative, Ken Spurlock sadly passed away at his home on the 14th December 2013, leaving behind his beloved wife Kathleen, daughters, Tina and Gillian and his grandchildren and great grandchildren. His funeral took place in the Wenallt Chapel at Thornhill Crematorium, located in the northern suburbs of Cardiff. His great friend, Jack Horner died a few short years later on the 30th September 2017. I would like to dedicate this Chindit story to the families of Ken Spurlock and Jack Horner, brought together by adversity to form a life-long and wonderful friendship.

As mentioned at the very beginning of this narrative, Ken Spurlock sadly passed away at his home on the 14th December 2013, leaving behind his beloved wife Kathleen, daughters, Tina and Gillian and his grandchildren and great grandchildren. His funeral took place in the Wenallt Chapel at Thornhill Crematorium, located in the northern suburbs of Cardiff. His great friend, Jack Horner died a few short years later on the 30th September 2017. I would like to dedicate this Chindit story to the families of Ken Spurlock and Jack Horner, brought together by adversity to form a life-long and wonderful friendship.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, October 2019.