Captain John Coleridge Fraser

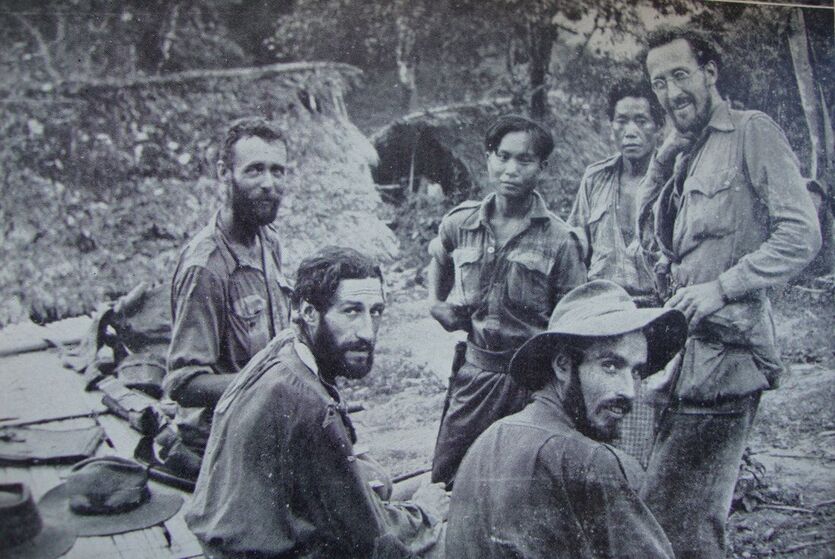

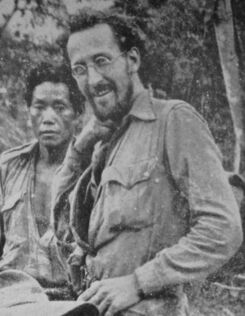

John Fraser in Burma, April 1943.

John Fraser in Burma, April 1943.

Major Bernard Fergusson was always one of the first to recognise the work done by the men of the Burma Rifles on Operation Longcloth, placing a great deal of faith in their skills as guides and interpreters. There is no doubt that these men were responsible for saving the lives of many during the expedition in 1943, either by securing food from local villages when the men were starving, or by leading lost British soldiers home once dispersal had been called.

In his book Beyond the Chindwin, Fergusson describes his first meeting with the two Burma Rifle Officers allocated to No. 5 Column:

In a hut skilfully built by some of the Burma Riflemen I first met my officers. John Fraser, who commanded my Burma Rifle platoon, dark and spectacled and showing no sign of the shocking ordeal from which he had emerged only six weeks before (a reference to his escape from being a prisoner of the Japanese earlier in 1942). Like all of these officers he was employed in one of the big civilian firms in Burma, John's being in the rice department of Steel Brothers; and also like most of them he was from Scotland. His second officer was 'PAM' Heald, broad-shouldered, fair and young; he had been a housemaster at a Borstal before becoming a Labour Welfare Officer under the Burmah Oil company at Chauk. Fraser and I enjoyed recounting our memories from back home and in particular the wonderful countryside views from around the city of Edinburgh.

John Fraser Coleridge was born on the 12th December 1914 in the city of Kurseong, West Bengal. After his educational years, he took up a job with Steel Brothers, working as a Mercantile manager at their general staff offices in Rangoon from 1939 until 1941. He had been commissioned into the Burma Frontier Force as 2nd Lieutenant (ABRO no. 74) in March 1940 and promoted to full Lieutenant on the 8th September 1941. As Captain he performed the role of Quartermaster with the 3rd Battalion, the Burma Rifles in January 1942. During the retreat from Burma that same year, Fraser was captured by the Japanese and held for a short time at a house in Myitkhina with another soldier, Sergeant Pratt of the 7th Hussars. Pratt and Fraser managed to effect an escape and made their way out towards the Burma-Assam borders, eventually meeting up with some other refugees fleeing the Japanese including some other officers formerly with the Burma Frontier Forces.

From the book, Flight by Elephant, by Andrew Martin:

On 30th May (1942) two newcomers stumbled into the camp. They looked haggard even by the standards of the Chaukan Pass; they were Captain John Fraser of the Burma Frontier Force and Sergeant Pratt of the Seventh Hussars. They had been delayed for some reason in Myitkyina, and had then run into some Japs. They had been paraded before some Japanese officers; things had then happened as they do in films. Fraser and Pratt were tied hand and foot and put into the walled garden to the rear of a house. Their guards took Pratt's boots and Fraser's glasses.

Furthermore, one of the guards, seeing that Fraser and Pratt's wrists and ankles were becoming swollen, considerately loosened the bonds before going back into the house. While wriggling about the garden that night, Fraser and Pratt found a cigarette tin with a sharp lid. They managed to scrape it against the ropes at their wrist and so freed themselves. They then escaped, although Fraser had lost his spectacles, and was practically blind without them, and Pratt had to walk in his stocking feet. They found the track to Sumprabum and then amazingly stumbled across a wrecked car belonging to Fraser on the side of the road. Most of its contents had been purloined, but inside the glove box he found his prescription sunglasses, and so John Fraser would go through the mist, rain and jungle-gloom of the Chaukan Pass, wearing a pair of round wire-rimmed sunglasses. As for Sergeant Pratt, he did somehow manage to find some boots that fit him.

Travelling at first with some Indian soldiers, on the 31st May, Fraser met up with four commandos named Gardiner, McCrindle, Boyt and Howe. The six soldiers eventually joined up with a large party of civilian refugees and proceeded to march out of Burma via the arduous and often treacherous Chaukan Pass.

By the 12th June, the party were suffering from exhaustion and some were showing the first signs of disease, especially dysentery and malaria. That afternoon they arrived at the banks of the fast flowing Tilung Hka River and searched up and down the length of the river for a suitable crossing place. Eventually, Bill Howe found two fallen trees, one still rooted on the near bank with the other intertwined with the first, but pushing out into the river. Howe walked out along the trunks and with great fortune managed to make the far bank. One after the other, the men slowly crossed over the make-shift bridge. As the level of the river began to rise, Captain Boyt crossed next and had no trouble.

Boyt was followed by Sgt. Pratt. At the end of the first log there was a gap of about ten feet to the second. Whilst attempting this gap, Pratt went under, but fortunately came up again holding the second log tightly by his left arm. Then it was John Fraser's turn. He had been the slowest of the marchers due to a swollen ankle caused by the Japanese ropes when he was imprisoned. As he inched along the first tree trunk he kept stopping to push up his glasses. In the end he took these off and put them into his shirt pocket. At that moment he lost his footing and cartwheeled into the water, when he surfaced he grabbed hold of a small passing log and crashed hard into a boulder in the middle of the river.

From the far bank, Ritchie Gardiner immediately removed his own pack and dropped into the freezing water, allowing himself to be swept out to where Fraser was trapped against the boulder. On the near bank, Corporal Sawyer a radio operator from the Oriental Mission also moved to help Fraser, but slipped half-way across the log bridge and was swept away. Gardiner freed Fraser by cutting the straps of his pack with his kukri knife, the pack rolled away and the two men moved half swimming, half wading back to the first bank. Both men were back to square one and completely exhausted. They slowly trudged back to the previous camp and warmed themselves by the fire and dried out their wet clothes. The next morning the two men returned to the river and this time made it across with no alarms and continued their journey out to India.

In his book Beyond the Chindwin, Fergusson describes his first meeting with the two Burma Rifle Officers allocated to No. 5 Column:

In a hut skilfully built by some of the Burma Riflemen I first met my officers. John Fraser, who commanded my Burma Rifle platoon, dark and spectacled and showing no sign of the shocking ordeal from which he had emerged only six weeks before (a reference to his escape from being a prisoner of the Japanese earlier in 1942). Like all of these officers he was employed in one of the big civilian firms in Burma, John's being in the rice department of Steel Brothers; and also like most of them he was from Scotland. His second officer was 'PAM' Heald, broad-shouldered, fair and young; he had been a housemaster at a Borstal before becoming a Labour Welfare Officer under the Burmah Oil company at Chauk. Fraser and I enjoyed recounting our memories from back home and in particular the wonderful countryside views from around the city of Edinburgh.

John Fraser Coleridge was born on the 12th December 1914 in the city of Kurseong, West Bengal. After his educational years, he took up a job with Steel Brothers, working as a Mercantile manager at their general staff offices in Rangoon from 1939 until 1941. He had been commissioned into the Burma Frontier Force as 2nd Lieutenant (ABRO no. 74) in March 1940 and promoted to full Lieutenant on the 8th September 1941. As Captain he performed the role of Quartermaster with the 3rd Battalion, the Burma Rifles in January 1942. During the retreat from Burma that same year, Fraser was captured by the Japanese and held for a short time at a house in Myitkhina with another soldier, Sergeant Pratt of the 7th Hussars. Pratt and Fraser managed to effect an escape and made their way out towards the Burma-Assam borders, eventually meeting up with some other refugees fleeing the Japanese including some other officers formerly with the Burma Frontier Forces.

From the book, Flight by Elephant, by Andrew Martin:

On 30th May (1942) two newcomers stumbled into the camp. They looked haggard even by the standards of the Chaukan Pass; they were Captain John Fraser of the Burma Frontier Force and Sergeant Pratt of the Seventh Hussars. They had been delayed for some reason in Myitkyina, and had then run into some Japs. They had been paraded before some Japanese officers; things had then happened as they do in films. Fraser and Pratt were tied hand and foot and put into the walled garden to the rear of a house. Their guards took Pratt's boots and Fraser's glasses.

Furthermore, one of the guards, seeing that Fraser and Pratt's wrists and ankles were becoming swollen, considerately loosened the bonds before going back into the house. While wriggling about the garden that night, Fraser and Pratt found a cigarette tin with a sharp lid. They managed to scrape it against the ropes at their wrist and so freed themselves. They then escaped, although Fraser had lost his spectacles, and was practically blind without them, and Pratt had to walk in his stocking feet. They found the track to Sumprabum and then amazingly stumbled across a wrecked car belonging to Fraser on the side of the road. Most of its contents had been purloined, but inside the glove box he found his prescription sunglasses, and so John Fraser would go through the mist, rain and jungle-gloom of the Chaukan Pass, wearing a pair of round wire-rimmed sunglasses. As for Sergeant Pratt, he did somehow manage to find some boots that fit him.

Travelling at first with some Indian soldiers, on the 31st May, Fraser met up with four commandos named Gardiner, McCrindle, Boyt and Howe. The six soldiers eventually joined up with a large party of civilian refugees and proceeded to march out of Burma via the arduous and often treacherous Chaukan Pass.

By the 12th June, the party were suffering from exhaustion and some were showing the first signs of disease, especially dysentery and malaria. That afternoon they arrived at the banks of the fast flowing Tilung Hka River and searched up and down the length of the river for a suitable crossing place. Eventually, Bill Howe found two fallen trees, one still rooted on the near bank with the other intertwined with the first, but pushing out into the river. Howe walked out along the trunks and with great fortune managed to make the far bank. One after the other, the men slowly crossed over the make-shift bridge. As the level of the river began to rise, Captain Boyt crossed next and had no trouble.

Boyt was followed by Sgt. Pratt. At the end of the first log there was a gap of about ten feet to the second. Whilst attempting this gap, Pratt went under, but fortunately came up again holding the second log tightly by his left arm. Then it was John Fraser's turn. He had been the slowest of the marchers due to a swollen ankle caused by the Japanese ropes when he was imprisoned. As he inched along the first tree trunk he kept stopping to push up his glasses. In the end he took these off and put them into his shirt pocket. At that moment he lost his footing and cartwheeled into the water, when he surfaced he grabbed hold of a small passing log and crashed hard into a boulder in the middle of the river.

From the far bank, Ritchie Gardiner immediately removed his own pack and dropped into the freezing water, allowing himself to be swept out to where Fraser was trapped against the boulder. On the near bank, Corporal Sawyer a radio operator from the Oriental Mission also moved to help Fraser, but slipped half-way across the log bridge and was swept away. Gardiner freed Fraser by cutting the straps of his pack with his kukri knife, the pack rolled away and the two men moved half swimming, half wading back to the first bank. Both men were back to square one and completely exhausted. They slowly trudged back to the previous camp and warmed themselves by the fire and dried out their wet clothes. The next morning the two men returned to the river and this time made it across with no alarms and continued their journey out to India.

For his efforts at the Tilung Hka River, Ritchie Gardiner was later awarded the George Medal. John Fraser was also recognised for his endeavours during the retreat and was awarded a Mention in Despatches which was Gazetted on the 28th October 1942. Fraser then spent some time on the Assam border as a Station Staff Officer, assisting with the administration for the continuous stream of refugees coming out of Burma.

Captain John Ritchie Gardiner.

Captain John Ritchie Gardiner.

Award of the George Medal:

Captain John Ritchie Gardiner, Corps of Royal Engineers.

Captain Gardiner, as a member of a timber firm in Rangoon, was one of the final demolition party to leave Rangoon by sea. His services at that time were conspicuous. He was later commissioned and posted to the Burma Levies and remained in the Kachin Hills north of Myitkyina until the decision was made to attempt to reach India by the Chaukkan Pass after the monsoon had broken; a journey which was extremely hazardous and caused the greatest privations to any persons undertaking it.

On the 12th June 1942, Captain Gardiner rescued an officer from almost certain death by drowning at great risk to his own life. While the party were crossing a mountain torrent in spate by means of two fallen trees, the officer and a corporal slipped off the tree. The corporal* was washed away and drowned, while the officer managed to clutch a branch of a tree and hung on. The current was extremely fast. The remainder of the party which had already got across were too exhausted to render help, but Captain Gardiner, who was behind the officer, managed, although he was up to his waist in water with a very precarious foothold on the tree, to get a grasp of the officer.

After several minutes struggle he released the pack from the officer's back and eventually dragged him out on to the bank. At this time, members of the party were subsisting on one and a half cigarette tins of mouldy rice for ten mans' daily rations. They were in an extremely exhausted condition, and the physical effort required to drag the officer out of the stream could not be undertaken without serious risk of failure, with the inevitable result that both men would have been swept away and drowned. Captain Gardiner disregarded his own personal safety in his single-handed effort to rescue a brother officer.

*This was Corporal Frederick Sawyer, Royal Army Service Corps and formerly of the Oriental Mission.

Captain John Ritchie Gardiner, Corps of Royal Engineers.

Captain Gardiner, as a member of a timber firm in Rangoon, was one of the final demolition party to leave Rangoon by sea. His services at that time were conspicuous. He was later commissioned and posted to the Burma Levies and remained in the Kachin Hills north of Myitkyina until the decision was made to attempt to reach India by the Chaukkan Pass after the monsoon had broken; a journey which was extremely hazardous and caused the greatest privations to any persons undertaking it.

On the 12th June 1942, Captain Gardiner rescued an officer from almost certain death by drowning at great risk to his own life. While the party were crossing a mountain torrent in spate by means of two fallen trees, the officer and a corporal slipped off the tree. The corporal* was washed away and drowned, while the officer managed to clutch a branch of a tree and hung on. The current was extremely fast. The remainder of the party which had already got across were too exhausted to render help, but Captain Gardiner, who was behind the officer, managed, although he was up to his waist in water with a very precarious foothold on the tree, to get a grasp of the officer.

After several minutes struggle he released the pack from the officer's back and eventually dragged him out on to the bank. At this time, members of the party were subsisting on one and a half cigarette tins of mouldy rice for ten mans' daily rations. They were in an extremely exhausted condition, and the physical effort required to drag the officer out of the stream could not be undertaken without serious risk of failure, with the inevitable result that both men would have been swept away and drowned. Captain Gardiner disregarded his own personal safety in his single-handed effort to rescue a brother officer.

*This was Corporal Frederick Sawyer, Royal Army Service Corps and formerly of the Oriental Mission.

Before the year was up, Fraser had been seconded to the recently formed 77th Indian Infantry Brigade (Chindits) and given the command of the 2nd Burma Rifles Platoon in Bernard Fergusson's No. 5 Column. In his book, Beyond the Chindwin, Fergusson recalled Fraser's activities during training, especially his equestrian struggles:

Fraser was for the first time in his life, trying to master the way of a man and his horse, aided by his Karen groom, Nelson, who had himself never even seen one. John's daily hack was a sporting event. He had little say in where his horse would take him and when it was fresh it would go all over the shop. A visiting officer wrongly assumed that Fraser's Horse was a full cavalry regiment, rather than a single intractable animal. Fortunately, Nelson took to it like a duck to water and quickly became and excellent groom.

Fraser was for the first time in his life, trying to master the way of a man and his horse, aided by his Karen groom, Nelson, who had himself never even seen one. John's daily hack was a sporting event. He had little say in where his horse would take him and when it was fresh it would go all over the shop. A visiting officer wrongly assumed that Fraser's Horse was a full cavalry regiment, rather than a single intractable animal. Fortunately, Nelson took to it like a duck to water and quickly became and excellent groom.

Lt. Pam Heald.

Lt. Pam Heald.

The Burma Rifleman's role on Operation Longcloth was to liaise with the Burmese villages encountered along the way, arranging guides, extra rations and most importantly gaining information about Japanese movements and positions. This often meant that Captain Fraser and his mostly Karen Riflemen would be as far as 20 miles ahead of the main body of the column and had to work very much independently from their column commander.

The Burma Rifle Platoon for No. 5 Column was made up of around 30 personnel and was led by its two British officers, John Fraser holding the rank of Captain and Lt. Philip Anthony Mair Heald, known as Pam, as his second.

To read more about Lt. Heald and his time as a Chindit, please click on the following link: Lieutenant P.A.M. Heald

After this, there were Burmese officers holding the ranks of Subedar (senior native officer) and Jemadar, which was the equivalent of a 2nd Lieutenant in the British Army. Not many men with the rank of Subedar took part in the first Chindit expedition, leaving in most cases, the young Jemadars to perform the role of section commander. The rest of the platoon was made up of two Havildars (Sergeants), four Naiks (Corporals), Lance-Naiks and Riflemen.

Here is the composition, as far as I have been able to collate from books, war diaries and nominal rolls, of the Burma Rifle Platoon for No. 5 Column:

The Burma Rifle Platoon for No. 5 Column was made up of around 30 personnel and was led by its two British officers, John Fraser holding the rank of Captain and Lt. Philip Anthony Mair Heald, known as Pam, as his second.

To read more about Lt. Heald and his time as a Chindit, please click on the following link: Lieutenant P.A.M. Heald

After this, there were Burmese officers holding the ranks of Subedar (senior native officer) and Jemadar, which was the equivalent of a 2nd Lieutenant in the British Army. Not many men with the rank of Subedar took part in the first Chindit expedition, leaving in most cases, the young Jemadars to perform the role of section commander. The rest of the platoon was made up of two Havildars (Sergeants), four Naiks (Corporals), Lance-Naiks and Riflemen.

Here is the composition, as far as I have been able to collate from books, war diaries and nominal rolls, of the Burma Rifle Platoon for No. 5 Column:

|

Captain John Coleridge Fraser MC

Lieutenant Philip Anthony Mair Heald Subedar Ba Than Jemadar Sao Man Hpa Jemadar Aung Pe Havildar Billy Havildar Po Po Tu Havidar Saw Lader Naik Jameson Naik Nay Dun Naik Tun So Ne Lance/Naik Ba U Lance/Naik Kang Tawng |

Rifleman Kyaw Thein

Rifleman San Khai Rifleman Robert Rifleman Washington Rifleman Saw Sein U Rifleman Saw Ohm Maung Rifleman Anthony Rifleman Ba Tun Rifleman Maung Kyan Rifleman Maung Tun Rifleman Nelson Rifleman Pa Haw |

No. 5 Column's main task on Operation Longcloth was to blow the railway line and bridge at a place called Bonchaung. These demolitions took place on the 6th March 1943 and were in essence successful, although the column did suffer several casualties that morning in attempting to secure the perimeter of the village. To read more about the events at Bonchaung, please click on the following link: Lt. David Whitehead

While the column's Royal Engineers were busy at Bonchaung, Captain Fraser and his men were moving swiftly to the east and heading for the Irrawaddy River in search of a suitable crossing place. Fraser decided upon the town of Tigyaing and settled down to wait for Major Fergusson and the rest of the column. Nearly three days later the rest of No. 5 Column finally arrived, having had several problems to solve on their journey from Bonchaung, including locating a missing party of men led by Lt. Jim Harman.

Fergusson and Fraser discussed their options and devised a plan: Three platoons were told to enter the town, take control of the boats and form a perimeter around Tigyaing. The main body would then enter the town. Within minutes of their arrival, a Japanese aircraft flew over the town and dropped leaflets, urging the Chindits to surrender. Fraser felt that the Japanese wouldn’t have bothered with leaflets if they were positioned to intercept them before a crossing could take place. Nevertheless, there was a Japanese garrison at Tawma, just eight miles south west, so they would need to crack on.

The Chindits marched smartly in threes in order to make an impression on the locals. The town soon developed a festive atmosphere and the shops opened. Jim Harman’s platoon was soon across the river to form a bridgehead and the boats were readied for the next group. Bernard Fergusson got his first look at the Irrawaddy: “My first reaction was to thank my stars I had come to a ferry town; getting across without the help of proper boats was obviously out of the question. It was fully a mile wide; although much of the space was filled up with sandbanks, the actual channel was not less than half a mile.”

Around 20 boats were soon busy. The men had to splash across the shallows from the waterfront to the main sandbank, from where they boarded the boats and embarked. Two rifle platoons were told they were next and began their journey. Immediately opposite the crossing point was Myadaung village and beyond were the hills around Pegon, the location of No. 5 Column's much-needed and pre-arranged supply drop. They bought up supplies in Tigyaing – eggs, potatoes, rice, vegetables and fruit. Men and animals continued to cross over to the big sandbank, with others coming forward as boats became available.

The afternoon was now running thin, but it looked as though they could be over before dark. About 45 minutes before dark, only one platoon remained at Tigyaing and it was brought in close to hold a smaller perimeter around the waterfront. Suddenly, the atmosphere cooled, the waterfront crowd melted away and the boatmen – instead of bringing their boats back – disappeared downriver. Fergusson had just one boat still under his command when this happened. Fortunately, another boat, just finishing its run to the other side of the river was commandeered before it could shove off and join the others in retreat.

Major Fergusson later heard that 200 Japanese were marching towards them, following the bank from the south of Tigyaing. The Longcloth force still had around 60 men and 10 animals waiting to cross. It was a slow business and all but completed, when they were fired upon from the main river bank, just south of the town. Fergusson and the few still on the wrong side stayed stock still. All they could do was wait for the boat. Fergusson described the last minutes: “Out of the blackness came the creaking of a boat. We filled it with the remaining Bren gunners, with Cairns, Peter Dorans and a few more odd men. As they were getting in, the other boat came … and grounded safely … The rest of us got in …”

The heavily-laden Column Commander struggled to board the boat and was hauled in by the seat of his trousers. Fergusson crossed the river, under fire, in unflattering fashion, that being on his knees, with his behind in the air. He couldn’t move for fear of capsizing the small boat, which rolled at any excuse. In the pitch dark, it proved difficult to form up on the other side of the river but, eventually, the column marched out of Myadaung and away from the Irrawaddy. Major Fergusson wrote: “… it was not long before we were bedded down in the adjacent jungle, after the most exciting day of my young life.”

While the column's Royal Engineers were busy at Bonchaung, Captain Fraser and his men were moving swiftly to the east and heading for the Irrawaddy River in search of a suitable crossing place. Fraser decided upon the town of Tigyaing and settled down to wait for Major Fergusson and the rest of the column. Nearly three days later the rest of No. 5 Column finally arrived, having had several problems to solve on their journey from Bonchaung, including locating a missing party of men led by Lt. Jim Harman.

Fergusson and Fraser discussed their options and devised a plan: Three platoons were told to enter the town, take control of the boats and form a perimeter around Tigyaing. The main body would then enter the town. Within minutes of their arrival, a Japanese aircraft flew over the town and dropped leaflets, urging the Chindits to surrender. Fraser felt that the Japanese wouldn’t have bothered with leaflets if they were positioned to intercept them before a crossing could take place. Nevertheless, there was a Japanese garrison at Tawma, just eight miles south west, so they would need to crack on.

The Chindits marched smartly in threes in order to make an impression on the locals. The town soon developed a festive atmosphere and the shops opened. Jim Harman’s platoon was soon across the river to form a bridgehead and the boats were readied for the next group. Bernard Fergusson got his first look at the Irrawaddy: “My first reaction was to thank my stars I had come to a ferry town; getting across without the help of proper boats was obviously out of the question. It was fully a mile wide; although much of the space was filled up with sandbanks, the actual channel was not less than half a mile.”

Around 20 boats were soon busy. The men had to splash across the shallows from the waterfront to the main sandbank, from where they boarded the boats and embarked. Two rifle platoons were told they were next and began their journey. Immediately opposite the crossing point was Myadaung village and beyond were the hills around Pegon, the location of No. 5 Column's much-needed and pre-arranged supply drop. They bought up supplies in Tigyaing – eggs, potatoes, rice, vegetables and fruit. Men and animals continued to cross over to the big sandbank, with others coming forward as boats became available.

The afternoon was now running thin, but it looked as though they could be over before dark. About 45 minutes before dark, only one platoon remained at Tigyaing and it was brought in close to hold a smaller perimeter around the waterfront. Suddenly, the atmosphere cooled, the waterfront crowd melted away and the boatmen – instead of bringing their boats back – disappeared downriver. Fergusson had just one boat still under his command when this happened. Fortunately, another boat, just finishing its run to the other side of the river was commandeered before it could shove off and join the others in retreat.

Major Fergusson later heard that 200 Japanese were marching towards them, following the bank from the south of Tigyaing. The Longcloth force still had around 60 men and 10 animals waiting to cross. It was a slow business and all but completed, when they were fired upon from the main river bank, just south of the town. Fergusson and the few still on the wrong side stayed stock still. All they could do was wait for the boat. Fergusson described the last minutes: “Out of the blackness came the creaking of a boat. We filled it with the remaining Bren gunners, with Cairns, Peter Dorans and a few more odd men. As they were getting in, the other boat came … and grounded safely … The rest of us got in …”

The heavily-laden Column Commander struggled to board the boat and was hauled in by the seat of his trousers. Fergusson crossed the river, under fire, in unflattering fashion, that being on his knees, with his behind in the air. He couldn’t move for fear of capsizing the small boat, which rolled at any excuse. In the pitch dark, it proved difficult to form up on the other side of the river but, eventually, the column marched out of Myadaung and away from the Irrawaddy. Major Fergusson wrote: “… it was not long before we were bedded down in the adjacent jungle, after the most exciting day of my young life.”

For his efforts on Operation Longcloth and in particular during the crossing of Tigyaing on the 10th March 1943, John Fraser was awarded the Military Cross:

Action for which recommended:

Captain Fraser served as 2nd-in-command to No. 5 Column, and as Officer Commanding the detachment of Burma Rifles with that Column. These troops excelled in all the branches of their duties, in gaining of intelligence, in foraging and in propaganda. Their success in these was due to Captain Fraser's careful and patient training, and their invariable courage in circumstances which were often trying to his personal example. The successful crossing at Tigyaing at the Irrawaddy River on 10th March 1943, was almost entirely the work of Captain Fraser, whose bold reconnaissance, efficiency and exemplary handling of the local inhabitants resulted in a flawless operation.

During the later withdrawal from Burma, Fraser's experience and advice was instrumental in ensuring success on that hazardous journey. As the only Burmese speaker with the party, his work was never ceasing. His intimate knowledge of the Burmese, and the judicious mixture of tact and firmness with which he handled them, were invaluable. From them in the course of the campaign he collected much intelligence of strategic as well as immediate value. His personal courage was of a rare standard, leading him cheerfully into situations of great danger; and his resolution, particularly in adversity, were an inspiration to all, and not least to his Column Commander.

Recommended by: Major B.E. Fergusson, DSO, The Black Watch, Column Commander.

Signed By: Brigadier O.C. Wingate, Commander, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

London Gazette: 16th December 1943.

Action for which recommended:

Captain Fraser served as 2nd-in-command to No. 5 Column, and as Officer Commanding the detachment of Burma Rifles with that Column. These troops excelled in all the branches of their duties, in gaining of intelligence, in foraging and in propaganda. Their success in these was due to Captain Fraser's careful and patient training, and their invariable courage in circumstances which were often trying to his personal example. The successful crossing at Tigyaing at the Irrawaddy River on 10th March 1943, was almost entirely the work of Captain Fraser, whose bold reconnaissance, efficiency and exemplary handling of the local inhabitants resulted in a flawless operation.

During the later withdrawal from Burma, Fraser's experience and advice was instrumental in ensuring success on that hazardous journey. As the only Burmese speaker with the party, his work was never ceasing. His intimate knowledge of the Burmese, and the judicious mixture of tact and firmness with which he handled them, were invaluable. From them in the course of the campaign he collected much intelligence of strategic as well as immediate value. His personal courage was of a rare standard, leading him cheerfully into situations of great danger; and his resolution, particularly in adversity, were an inspiration to all, and not least to his Column Commander.

Recommended by: Major B.E. Fergusson, DSO, The Black Watch, Column Commander.

Signed By: Brigadier O.C. Wingate, Commander, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

London Gazette: 16th December 1943.

As mentioned in the above recommendation, John Fraser's contribution on Operation Longcloth was vital in the good performance of No. 5 Column's duties. His skills came to the fore once again after dispersal was called and the Chindits turned for home in late March. On the return trip he remained with Major Fergusson's group and organised their route back to the Chindwin. He also arranged local guides for the now ailing party, as well as obtaining food from Burmese villages to feed the ravenously hungry men.

Bernard Fergusson recalled:

On the way back, John took control of our path. His patience would often be strained if anybody, including myself interrupted him when conversing or interrogating a local villager. He would allow me to listen in, but would keep all others out of earshot. He would often shout: "Will all those senior to me kindly give me air and all those junior to me, PUSH OFF!"

In the end, the remnants of No. 5 Column, which in essence comprised the dispersal parties of Major Fergusson and Flight Lieutenant Denis Sharp, re-crossed the Chindwin River on the 24th April 1943. The men who had survived the expedition were in a terribly fatigued condition and were in the first instance taken to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station on the outskirts of Imphal. After having their ailments treated at the makeshift hospital, they were sent on a longer period of rest and recuperation, before re-joining their regiment at its new base in Karachi.

To read about the journey of No. 5 Column in more depth, please click on the following link: Following 5 Column

Bernard Fergusson recalled:

On the way back, John took control of our path. His patience would often be strained if anybody, including myself interrupted him when conversing or interrogating a local villager. He would allow me to listen in, but would keep all others out of earshot. He would often shout: "Will all those senior to me kindly give me air and all those junior to me, PUSH OFF!"

In the end, the remnants of No. 5 Column, which in essence comprised the dispersal parties of Major Fergusson and Flight Lieutenant Denis Sharp, re-crossed the Chindwin River on the 24th April 1943. The men who had survived the expedition were in a terribly fatigued condition and were in the first instance taken to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station on the outskirts of Imphal. After having their ailments treated at the makeshift hospital, they were sent on a longer period of rest and recuperation, before re-joining their regiment at its new base in Karachi.

To read about the journey of No. 5 Column in more depth, please click on the following link: Following 5 Column

Captain Fraser also served with Brigadier Bernard Fergusson on the second Wingate expedition in 1944. He was a member of 16th Brigade's Head Quarters on Operation Thursday, where his old commander's unit were the only Chindit Brigade to be made to march into Burma, whilst most other Chindits flew in aboard WACO Gliders of USAAF Dakotas. Fraser was once again responsible for the route chosen and during the early weeks of the expedition he commanded a satellite company named Fraser Force, which would protect the Brigade's westward facing flank against attack. He was also instrumental in the setting up of the Chindit stronghold at Manhton, codenamed Aberdeen by Fergusson and where Fraser took charge of liaising with the local villagers, setting defences and organising all the Chindit related supply drops. Unfortunately for Fraser, towards the end of the campaign he fell ill suffering with severe bouts of malaria. He was tended by the Headman of Manhton and his family before being flown out by Dakota in May 1944.

John went home to the United Kingdom immediately after the war, but voyaged back to Burma aboard the Bibby Line passenger ship, Highland Princess in August 1946. John was returning to Burma to resume working for Steel Brothers & Co. and alongside him on the voyage were his new wife, Eileen and his baby son, Simon. On the 19th September 1946, he was awarded a Mention in Despatches (MID) in recognition of his gallant and distinguished service during the Burma Campaign.

After returning to the UK once more, John Fraser took up chicken farming at Wooplaw, near Galashiels in the Scottish Borders. Sadly, on the 18th June 1965, he was killed in a road traffic accident, when his son lost control of the family car after being dazzled by the lights of an on-coming vehicle. John Fraser was cremated a few days later at Edinburgh, the city he and Bernard Fergusson had lovingly discussed so many times during their service together in Burma.

To end this story, seen below is a gallery of photographs taken by No. 5 Column on the 10th March 1943 at the Burmese riverside town of Tigyaing, the scene of John Fraser's greatest achievements during Operation Longcloth. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. By far the best place to read and learn more about this remarkable soldier is within the pages of Beyond the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson's book about the adventures of No. 5 Column in 1943. I wish you happy reading.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, March 2020.