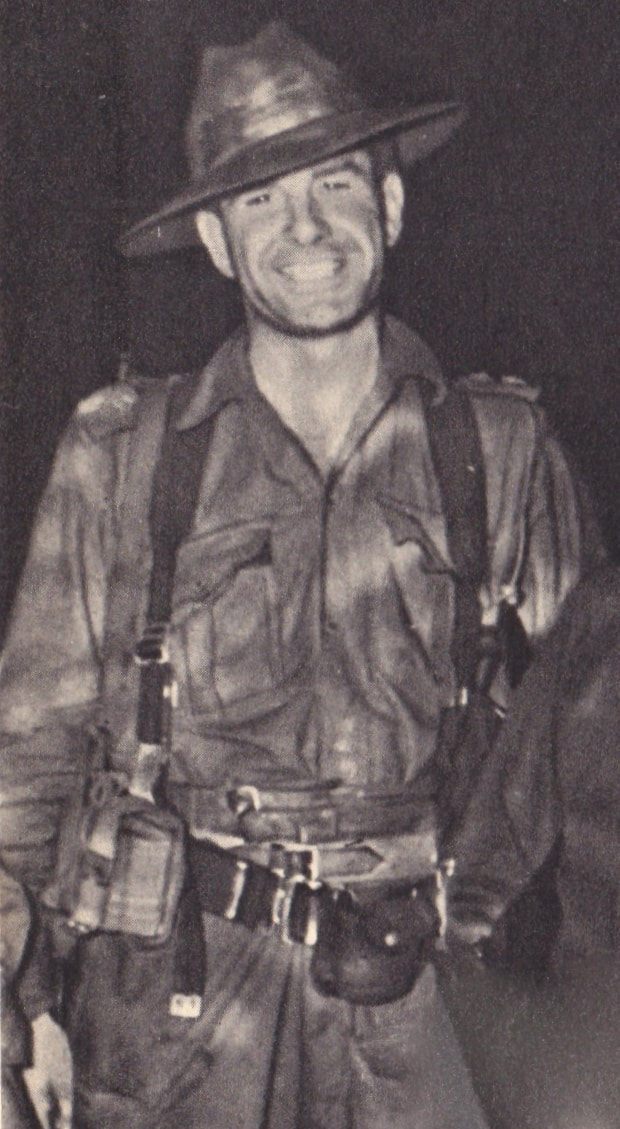

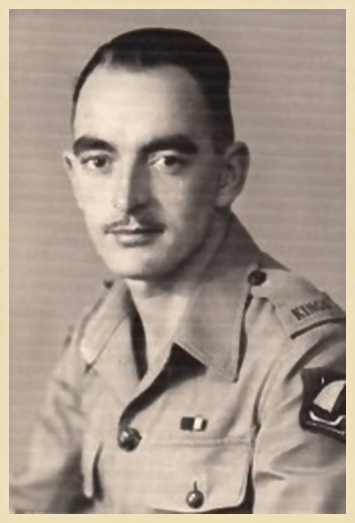

Captain Nigel Whitehead

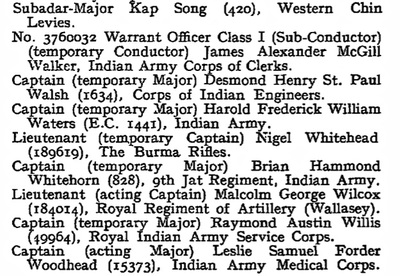

Cap badge of the Burma Rifles.

Cap badge of the Burma Rifles.

Born on the 22nd October 1915 in Reading, Berkshire, 189619 Captain Nigel Whitehead was drafted into the Burma Rifles Regiment as an emergency commissioned officer (ECO) on the 28th April 1941and served with the 1st Battalion of the Burma Rifles that year, acting for a time as Intelligence Officer in the Southern Shan States. He had previously worked within the Justice System in Northern Burma as a Resident Magistrate and also for Steel Brothers, and so very much knew the ways and customs of the local area and its inhabitants.

Nigel arrived at the Chindit training camp at Abchand in the Central Provinces of India on the 3rd September 1942 and was posted to 8 Column, under the command of Major Walter Scott of the King's Regiment. Captain Whitehead and Major Scott forged a friendship that would last throughout the next two years and both Chindit campaigns.

Captain Whitehead took command of the Burma Rifles Platoon in 8 Column. There was a platoon of Burma Rifles in each of the seven Chindit Columns on Operation Longcloth. This was usually made up of 30-40 personnel and led by two British officers, one holding the rank of Captain, the other a Lieutenant. Subsequent to this, there were Burmese officers holding the ranks of Subedar (senior native officer) and Jemadar, which was the equivalent of a 2nd Lieutenant in the British Army. Not many men with the rank of Subedar took part in the first Chindit expedition, leaving in most cases, young and inexperienced Jemadars to perform the role of section commander. The rest of the platoon was made up of two Havildars (Sergeants), four Naiks (Corporals), Lance-Naiks and Riflemen.

Nigel Whitehead's experience and knowledge of the terrain covered by the Chindits in 1943 proved invaluable. On the 23rd February and not long after the Brigade had crossed the Chindwin River, Whitehead informed a conference of senior officers that: "We are going the wrong way." His protest was ignored by the lead scouts of 7 Column, who had been ordered to search out a suitable route towards the village of Sinlamaung where a Japanese garrison was thought to exist. After marching for some considerable time and often through almost impenetrable bamboo scrub, Whitehead was finally brought forward and took control of proceedings from that moment on.

In those early weeks behind enemy lines in 1943, Whitehead was often used as liaison officer between 8 Column and the other Chindit units (mostly Wingate's HQ and 7 Column) in the vicinity. He was in charge of 8 Column as the unit moved along the secret track, used by Northern Group to bypass the Japanese garrisons stationed in the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment. On the 5th March, the Commando Platoon from 8 Column found itself cut-off from the main column by an ambush from a Japanese patrol. After a long and hard-fought battle across the Pinlebu-Kame motor road, the commandos were struggling to disengage from the enemy. Captain Whitehead and a section of his Burrifs went forward and with covering fire, opened up an escape pathway for the beleaguered men.

After the engagement at Pinlebu on the 5/6th March 1943, Major Scott issued this statement: The work and actions of Captain Whitehead during the last 48 hours are an example to all other officers. One week later, on the 13th March, Whitehead's Burrif platoon were in action again, this time at a village called Kyunbin. They had been sent ahead to seek out a suitable location for the next supply drop and had chosen the paddy fields on the outskirts of the village. After the drop zone had been secured, a Japanese patrol stumbled upon the area and a short firefight ensued. The enemy were well beaten by Whitehead's men and those Japanese who were not dispatched at Kyunbin, quickly withdrew from the area.

On the 3rd April, 8 Column were waiting to cross the treacherously fast flowing Shweli River. Two days previously, on their first attempt to cross the river, Captain Williams and his platoon had succeeded in getting over. This group had then become separated after the next section of men accidentally lost control of the boats used and were washed away downstream. After coming to terms with this latest disaster, Major Scott called up the RAF to drop more dinghies to the column and these duly arrived the next day. It was decided to split the column into three groups after crossing the Shweli, this was to ensure that if the Chindits met with any enemy interference on the opposite bank, they would not all be in one place and easily engaged or captured. It will come as no surprise, that Captain Whitehead was chosen to lead one of these groups.

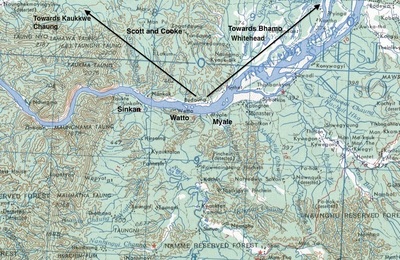

A few days later, the three groups re-formed at a pre-arranged rendezvous and began their approach towards the Irrawaddy, close to where the river meanders near the village of Myale. On 12th April, the front of the column was approaching a newly built bamboo bridge over a chaung when they bumped into a couple of Japanese who turned and bolted back into the jungle. Intense firing broke out and Sergeant Bridgeman and Private Beard were killed, while Privates Lawton and Witheridge were both seriously wounded. Most of the column turned around and disappeared along the track they had come down, leaving Major Scott and a small party of men isolated for a short time. It was not until the evening that the column reassembled and it was discovered that Lieutenant Horncastle and 14 others were missing. It was thought that they might have subsequently moved off as a separate party.

The column was up and moving at 0430 hours the next morning. The going was quite good but they now had three wounded on stretchers to carry with them. Major Scott and Lieutenant Colonel Cooke held an officers' conference and it was decided that they would request one last supply drop before breaking up into dispersal groups to cross the Irrawaddy. The dispersal groups were arranged as follows:

Lieutenant Colonel Cooke, Lieutenant Borrow and half of Group Headquarters;

Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and the other half of Group Headquarters;

Major Scott with Column Headquarters, 17 Platoon and two sections of 16 Platoon;

Captain Whitehead and his Burma Rifles less those already allocated to assist the other dispersal groups, plus Flying Officer Wheatley and a section of 16 Platoon;

Lieutenants Carroll, Hamilton-Bryan with Support Group and 19 Platoon;

Lieutenants Neill and Sprague with the Gurkha Platoon and 142 Commando Platoon.

On 15th April, Captain Whitehead and his dispersal group, together with the stretcher party under Sergeant Parsons and the Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote, left the column. They planned to move to the east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkyina to Fort Hertz. If this plan failed they would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then go west towards the Chindwin.

Captain Whitehead's group was considerably larger than most, being made up of around 60-70 men. The reason for this was that he had agreed to take with him a number of sick and wounded men from Platoon 16, many of these soldiers needed to be carried on stretchers and had been battle casualties at the village of Baw on the 23rd March. Whitehead's intention was to find a friendly Kachin village in which to leave these men and then take the rest of his party back to India. After several days of searching no suitable village was found, in fact many of the villages listed on the Captain's map no longer seemed to exist.

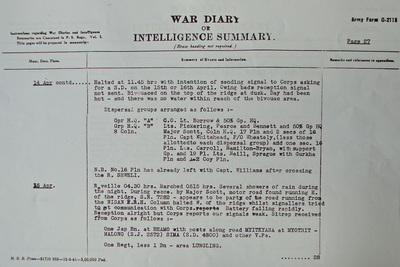

Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke's entry for the 15th April 1943 in 8 Column's War diary, describes the intentions of Captain Whitehead and his aspirations for the sick and wounded men under his command:

Column failed to make contact with Corps, battery very weak, decided to give it a rest for 24 hours and then send an abbreviated signal tomorrow.

Captain Whitehead with his dispersal group, the stretcher party carrying a wounded Burrif, Pte. Lawton and Pte. Witherridge, the Medical Officer and an escort party under Captain Hamilton-Bryan left the column at 1530 hours. Captain Whitehead's intention was to return to British held territory, going east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkhina and Fort Hertz. Failing this he would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then head west to the Chindwin.

The wounded are to be dropped off at a friendly Kachin village, where they would be given 75 rupees in silver, their rifle and ammunition, plus a compass. Whitehead asked for two supply drops to be arranged along his proposed route; that is if wireless communication can be re-opened with Corps. At 0500 hours on the 16th April, a short message was sent to Corps. A runner then came back from Whitehead's party reporting their difficulty in moving down the eastern slopes of the mountains and that the first villages visited were deserted.

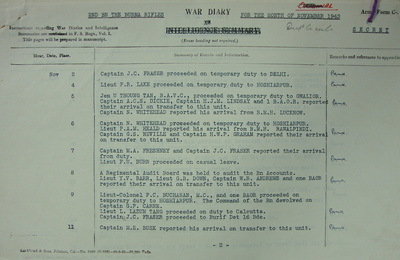

Seen below, a page from the 8 Column War diary, describing the allocation of the dispersal parties and a map of the Irrawaddy and the dispersal routes taken by each group. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Nigel arrived at the Chindit training camp at Abchand in the Central Provinces of India on the 3rd September 1942 and was posted to 8 Column, under the command of Major Walter Scott of the King's Regiment. Captain Whitehead and Major Scott forged a friendship that would last throughout the next two years and both Chindit campaigns.

Captain Whitehead took command of the Burma Rifles Platoon in 8 Column. There was a platoon of Burma Rifles in each of the seven Chindit Columns on Operation Longcloth. This was usually made up of 30-40 personnel and led by two British officers, one holding the rank of Captain, the other a Lieutenant. Subsequent to this, there were Burmese officers holding the ranks of Subedar (senior native officer) and Jemadar, which was the equivalent of a 2nd Lieutenant in the British Army. Not many men with the rank of Subedar took part in the first Chindit expedition, leaving in most cases, young and inexperienced Jemadars to perform the role of section commander. The rest of the platoon was made up of two Havildars (Sergeants), four Naiks (Corporals), Lance-Naiks and Riflemen.

Nigel Whitehead's experience and knowledge of the terrain covered by the Chindits in 1943 proved invaluable. On the 23rd February and not long after the Brigade had crossed the Chindwin River, Whitehead informed a conference of senior officers that: "We are going the wrong way." His protest was ignored by the lead scouts of 7 Column, who had been ordered to search out a suitable route towards the village of Sinlamaung where a Japanese garrison was thought to exist. After marching for some considerable time and often through almost impenetrable bamboo scrub, Whitehead was finally brought forward and took control of proceedings from that moment on.

In those early weeks behind enemy lines in 1943, Whitehead was often used as liaison officer between 8 Column and the other Chindit units (mostly Wingate's HQ and 7 Column) in the vicinity. He was in charge of 8 Column as the unit moved along the secret track, used by Northern Group to bypass the Japanese garrisons stationed in the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment. On the 5th March, the Commando Platoon from 8 Column found itself cut-off from the main column by an ambush from a Japanese patrol. After a long and hard-fought battle across the Pinlebu-Kame motor road, the commandos were struggling to disengage from the enemy. Captain Whitehead and a section of his Burrifs went forward and with covering fire, opened up an escape pathway for the beleaguered men.

After the engagement at Pinlebu on the 5/6th March 1943, Major Scott issued this statement: The work and actions of Captain Whitehead during the last 48 hours are an example to all other officers. One week later, on the 13th March, Whitehead's Burrif platoon were in action again, this time at a village called Kyunbin. They had been sent ahead to seek out a suitable location for the next supply drop and had chosen the paddy fields on the outskirts of the village. After the drop zone had been secured, a Japanese patrol stumbled upon the area and a short firefight ensued. The enemy were well beaten by Whitehead's men and those Japanese who were not dispatched at Kyunbin, quickly withdrew from the area.

On the 3rd April, 8 Column were waiting to cross the treacherously fast flowing Shweli River. Two days previously, on their first attempt to cross the river, Captain Williams and his platoon had succeeded in getting over. This group had then become separated after the next section of men accidentally lost control of the boats used and were washed away downstream. After coming to terms with this latest disaster, Major Scott called up the RAF to drop more dinghies to the column and these duly arrived the next day. It was decided to split the column into three groups after crossing the Shweli, this was to ensure that if the Chindits met with any enemy interference on the opposite bank, they would not all be in one place and easily engaged or captured. It will come as no surprise, that Captain Whitehead was chosen to lead one of these groups.

A few days later, the three groups re-formed at a pre-arranged rendezvous and began their approach towards the Irrawaddy, close to where the river meanders near the village of Myale. On 12th April, the front of the column was approaching a newly built bamboo bridge over a chaung when they bumped into a couple of Japanese who turned and bolted back into the jungle. Intense firing broke out and Sergeant Bridgeman and Private Beard were killed, while Privates Lawton and Witheridge were both seriously wounded. Most of the column turned around and disappeared along the track they had come down, leaving Major Scott and a small party of men isolated for a short time. It was not until the evening that the column reassembled and it was discovered that Lieutenant Horncastle and 14 others were missing. It was thought that they might have subsequently moved off as a separate party.

The column was up and moving at 0430 hours the next morning. The going was quite good but they now had three wounded on stretchers to carry with them. Major Scott and Lieutenant Colonel Cooke held an officers' conference and it was decided that they would request one last supply drop before breaking up into dispersal groups to cross the Irrawaddy. The dispersal groups were arranged as follows:

Lieutenant Colonel Cooke, Lieutenant Borrow and half of Group Headquarters;

Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and the other half of Group Headquarters;

Major Scott with Column Headquarters, 17 Platoon and two sections of 16 Platoon;

Captain Whitehead and his Burma Rifles less those already allocated to assist the other dispersal groups, plus Flying Officer Wheatley and a section of 16 Platoon;

Lieutenants Carroll, Hamilton-Bryan with Support Group and 19 Platoon;

Lieutenants Neill and Sprague with the Gurkha Platoon and 142 Commando Platoon.

On 15th April, Captain Whitehead and his dispersal group, together with the stretcher party under Sergeant Parsons and the Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote, left the column. They planned to move to the east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkyina to Fort Hertz. If this plan failed they would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then go west towards the Chindwin.

Captain Whitehead's group was considerably larger than most, being made up of around 60-70 men. The reason for this was that he had agreed to take with him a number of sick and wounded men from Platoon 16, many of these soldiers needed to be carried on stretchers and had been battle casualties at the village of Baw on the 23rd March. Whitehead's intention was to find a friendly Kachin village in which to leave these men and then take the rest of his party back to India. After several days of searching no suitable village was found, in fact many of the villages listed on the Captain's map no longer seemed to exist.

Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke's entry for the 15th April 1943 in 8 Column's War diary, describes the intentions of Captain Whitehead and his aspirations for the sick and wounded men under his command:

Column failed to make contact with Corps, battery very weak, decided to give it a rest for 24 hours and then send an abbreviated signal tomorrow.

Captain Whitehead with his dispersal group, the stretcher party carrying a wounded Burrif, Pte. Lawton and Pte. Witherridge, the Medical Officer and an escort party under Captain Hamilton-Bryan left the column at 1530 hours. Captain Whitehead's intention was to return to British held territory, going east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkhina and Fort Hertz. Failing this he would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then head west to the Chindwin.

The wounded are to be dropped off at a friendly Kachin village, where they would be given 75 rupees in silver, their rifle and ammunition, plus a compass. Whitehead asked for two supply drops to be arranged along his proposed route; that is if wireless communication can be re-opened with Corps. At 0500 hours on the 16th April, a short message was sent to Corps. A runner then came back from Whitehead's party reporting their difficulty in moving down the eastern slopes of the mountains and that the first villages visited were deserted.

Seen below, a page from the 8 Column War diary, describing the allocation of the dispersal parties and a map of the Irrawaddy and the dispersal routes taken by each group. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

From reading about and researching the men of Operation Longcloth, I can confirm that Sergeant Tony Aubrey, Pte. Dennis Brown and a Burma Rifles officer, Jemadar Ah Di were all part of the dispersal group led by Captain Whitehead. Aubrey and Brown were seconded to the group by Lt. Hamilton-Bryan and acted as stretcher-bearers for the wounded. Both these men returned to the main body of 8 Column around 24 hours after leaving the wounded Chindits with the Headman of a local Kachin village.

Sgt. Aubrey remembered those difficult few days after dispersal in his book, With Wingate in Burma, written with the assistance of co-author David Halley:

The hardness of the road, and the scarcity of villages on the way, made it seem likely that small bodies would have a better chance than large ones of winning through. So it was decided that we should split up into the dispersal groups previously decided upon. The officer commanding each group would choose his own route and employ his own methods. Another decision was also arrived at now, and this the hardest that anyone could be called upon to make.

We had carried with us since the action of the previous day three wounded men whose hurts were so serious that they could not walk. Two of these were British and one Burmese. We had no proper stretchers to carry them on, and had improvised litters for them out of bamboo. The jungle which now lay before us was to all intents and purposes virgin. To make our way through it unburdened would be a task of the utmost difficulty. To carry litters through it would be a virtual impossibility.

The discomfort to which the wounded men themselves would be put on such a journey would be horrible, and would in all probability aggravate their injuries to a fatal extent. Both they themselves and the remainder of the column would stand a better chance of survival if they were left behind. The situation was put to them, and they at once agreed, like the men they were. There was a village twelve miles away, and here we decided to leave them, in the hands of the Burmese, who had always shown themselves friendly towards us, and who would look after them to the best of their ability.

Some of the Group Commanders decided that their best course would be to stay where they were, on top of the hill, till nightfall, and march under cover of darkness. But Captain Whitehead of the Burma Rifles, made up his mind to start at once. So the wounded would be sent, under the protection of his group, to the village.

Volunteers were called for to make a carrying party. Thirty men were chosen, under Mr. Hamilton Bryan, with myself as his sergeant. Major Scott said that he would wait for our return until dark before leaving; all the cigarettes available were collected and given to the wounded, farewells were said, and we started. That march was a nightmare.

Captain Whitehead was in a hurry, and so were we. We had no intention of failing to return to Major Scott, and what seemed comparative safety, before the time laid down by him. Yet every step in this jungle, the thickest I have ever seen, had to be won, and our dhas were in constant use. The pain the wounded must have suffered beggars description, but not one of them uttered a sound of complaint.

It had been still early morning when we started, and it is a tribute to our strength, and our anxiety, that we reached the village which was our destination shortly after twelve midday. But reaching it did us no good. It had been a village once, but now it was only a collection of burnt patches on the ground. There was no sign of life, not a Burmese, not a domestic animal, not even a Jap was to be seen. It was complete desolation.

Captain Whitehead, who knew these parts pretty well, having been, I think, a Resident Magistrate, said that there should be another village six miles farther on. Probably, it too, would be in this same condition, but it was worth investigating. While the remainder of us rested and cooked a meal, two Burma Riflemen were sent on to reconnoitre. They were back in an incredibly short space of time, with the news that this village had not been molested in any way, that the villagers were carrying on as usual, and that there was no trace of Japs in the neighbourhood.

If the carrying party went on as far as this second village, it meant that they would have to cover another twelve miles, six carrying the litters, and six unburdened. That, in its turn, meant that they would almost certainly fail to contact Major Scott back at the rendezvous. So Captain Whitehead's party took on the carrying duties, and we were allowed to make our way back. I prefer not to think of saying goodbye to the wounded. Two of them I knew very well, and one had even travelled out from England in the same ship with me. This was war with a vengeance. The weak, as always, must suffer. If we had travelled fast coming, we tried to travel at twice the speed going back.

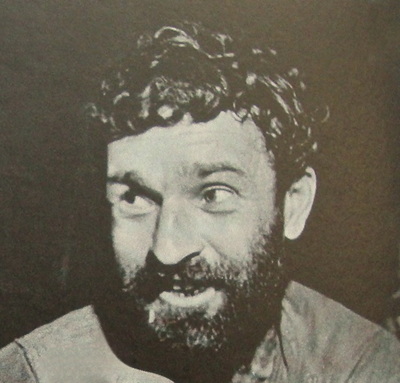

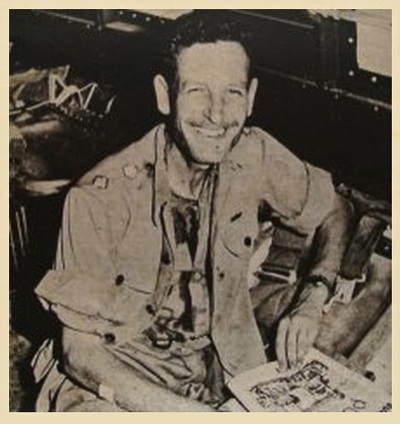

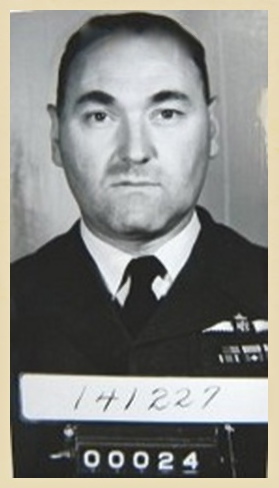

Seen in the gallery below, are photographs of some of the men mentioned in this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Sgt. Aubrey remembered those difficult few days after dispersal in his book, With Wingate in Burma, written with the assistance of co-author David Halley:

The hardness of the road, and the scarcity of villages on the way, made it seem likely that small bodies would have a better chance than large ones of winning through. So it was decided that we should split up into the dispersal groups previously decided upon. The officer commanding each group would choose his own route and employ his own methods. Another decision was also arrived at now, and this the hardest that anyone could be called upon to make.

We had carried with us since the action of the previous day three wounded men whose hurts were so serious that they could not walk. Two of these were British and one Burmese. We had no proper stretchers to carry them on, and had improvised litters for them out of bamboo. The jungle which now lay before us was to all intents and purposes virgin. To make our way through it unburdened would be a task of the utmost difficulty. To carry litters through it would be a virtual impossibility.

The discomfort to which the wounded men themselves would be put on such a journey would be horrible, and would in all probability aggravate their injuries to a fatal extent. Both they themselves and the remainder of the column would stand a better chance of survival if they were left behind. The situation was put to them, and they at once agreed, like the men they were. There was a village twelve miles away, and here we decided to leave them, in the hands of the Burmese, who had always shown themselves friendly towards us, and who would look after them to the best of their ability.

Some of the Group Commanders decided that their best course would be to stay where they were, on top of the hill, till nightfall, and march under cover of darkness. But Captain Whitehead of the Burma Rifles, made up his mind to start at once. So the wounded would be sent, under the protection of his group, to the village.

Volunteers were called for to make a carrying party. Thirty men were chosen, under Mr. Hamilton Bryan, with myself as his sergeant. Major Scott said that he would wait for our return until dark before leaving; all the cigarettes available were collected and given to the wounded, farewells were said, and we started. That march was a nightmare.

Captain Whitehead was in a hurry, and so were we. We had no intention of failing to return to Major Scott, and what seemed comparative safety, before the time laid down by him. Yet every step in this jungle, the thickest I have ever seen, had to be won, and our dhas were in constant use. The pain the wounded must have suffered beggars description, but not one of them uttered a sound of complaint.

It had been still early morning when we started, and it is a tribute to our strength, and our anxiety, that we reached the village which was our destination shortly after twelve midday. But reaching it did us no good. It had been a village once, but now it was only a collection of burnt patches on the ground. There was no sign of life, not a Burmese, not a domestic animal, not even a Jap was to be seen. It was complete desolation.

Captain Whitehead, who knew these parts pretty well, having been, I think, a Resident Magistrate, said that there should be another village six miles farther on. Probably, it too, would be in this same condition, but it was worth investigating. While the remainder of us rested and cooked a meal, two Burma Riflemen were sent on to reconnoitre. They were back in an incredibly short space of time, with the news that this village had not been molested in any way, that the villagers were carrying on as usual, and that there was no trace of Japs in the neighbourhood.

If the carrying party went on as far as this second village, it meant that they would have to cover another twelve miles, six carrying the litters, and six unburdened. That, in its turn, meant that they would almost certainly fail to contact Major Scott back at the rendezvous. So Captain Whitehead's party took on the carrying duties, and we were allowed to make our way back. I prefer not to think of saying goodbye to the wounded. Two of them I knew very well, and one had even travelled out from England in the same ship with me. This was war with a vengeance. The weak, as always, must suffer. If we had travelled fast coming, we tried to travel at twice the speed going back.

Seen in the gallery below, are photographs of some of the men mentioned in this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The only clue we have, as to what happened to Captain Whitehead, Flight Lieutenant Wheatley, Medical Officer J.D.S. Heathcote, Captain Hamilton-Bryan and the rest of the original dispersal group, comes from a testimony by Lt. J. H. Stuart-Jones of the Gurkha Rifles. In a letter written shortly after the war, Lt. Stuart-Jones, known to his colleagues as 'Jock' described the following:

About eight days after we crossed the Shweli River, it was decided we should split up into dispersal groups of about 60 men under 1 or 2 officers and choosing our own route, make our way back to India. My party formed part of the group under Captain Whitehead of the Burma Rifles.

I had inherited six British Other Ranks after the incident at Baw village. These were added to my original four B.O.R.'s and the 12 Gurkha muleteers already under my command. Our group then volunteered to take with them the wounded men from the Column and to put these into a friendly village near or in Kachin country. With these wounded were a number of stretcher bearers and all of these were from 16 Platoon.

The dispersal group moved away from the Irrawaddy and two days later we managed to place the wounded in a native Kachin/Shan village; whether they were looked after properly, I don't to know.

The following day our group was ambushed by a mixed force of Burmese and Japanese. Our rendezvous in case of attack, was a half-mile due North of our position. I made the R.V. in the company of two Burma Riflemen and a V.C.O. (Jemadar Ah Di) and waited there all night. We often heard firing from the direction of a village about a mile away.

We marched on for three days, passing between enemy held villages along the Sinlumkaba Tract. We had no food, but dare not enter any of these villages as we crossed over the Bhamo-Mandalay motor road. One evening we came across a village and entered cautiously to enquire about some food. We found the remainder of our dispersal party already there, less Captain Whitehead and Flight-Lieutenant Wheatley who had been lost at the ambush and the Medical Orderly who had been handed over to the Japanese by the Shans.

I took command of the party and we pushed on north, averaging approximately 12 miles a day. Progress was slow due to nature of the country and terrain. The men began to tire, for weeks of surviving on a diet of rice, bamboo leaves, roots and dried monkey meat when we could get it. Besides this, everyone was suffering to a greater or lesser degree, from fever, dysentery and septic jungle sores. Our uniforms were just rags and many men had no protective footwear. Our route was leading us into the hills of up to 5,500 feet and the men were becoming lethargic. I remember that sentry duty whilst guarding the camp at night became extremely arduous at this time.

Lt. Stuart-Jones had begun Operation Longcloth within the ranks of 4 Column, but had been separated from his unit when it was ambushed by a large Japanese patrol on the 4th March. He had the good fortunate to bump into Major Scott and 8 Column some time later and had journeyed with them for the rest of the operation up until dispersal was called. Lt. Stuart-Jones and his men finally reached Allied held territory in early July 1943 and in his letter written after the war, he recognised the invaluable contribution made by Jemadar Ah Di of the Burma Rifles in achieving this goal:

Having no maps of the area in which we were travelling and only one compass, I had to rely on the knowledge and skill of my Kachin Jemadar, Ah Di of the Burma Rifles. His fluency in the various dialects made him invaluable in obtaining information from villagers. In the hills opposite the east of Bhamo I lost one Kachin and two Karen riflemen, who decided to take their chances and head home. It was also at this time that we picked up Lieutenant Smyly of 5 Column, who was in a very weak state and barely able to walk. He was left in a friendly village, with Jemadar Ah Di instructing the villagers that they would be held responsible for the officers safety.

Everyone was now in a very weak state and at this time the Gurkhas were on average, sticking at it better than the British soldiers and the Burma Rifles. Through the efforts of Ah Di, we hired a Kachin guide who had once been with the Burma Frontier Force. He led us north and entered all villages first to check for Japanese patrols and to acquire rice to supplement our meagre rations. The Kachins in this area were very poor indeed and fearful of the Japs, but on the whole extremely friendly towards us.

There is no further information available, as to the fate of Captain Whitehead and the other officers lost during the ambush on or around the 18th April 1943. We know that Nigel Whitehead made it safely back to India after Operation Longcloth, by the fact of his continued service during the Burma Campaign. Medical Officer, Captain J.D.S. Heathcote and Lt. Hamilton-Bryan do not appear on any listing for soldiers killed in action in Burma, or indeed being held as prisoners of war. So it must be assumed that both men returned safely to Allied held territory in 1943. Flight-Lieutenant Kenneth Wheatley of the Royal Canadian Air Force, did have the misfortune of falling into Japanese hands after being captured on the 27th April near the Burmese railway town of Mohnyin. Kenneth spent just over two years as a POW inside Rangoon Jail, before being liberated by British troops at the village of Waw near Pegu, on the 29th April 1945.

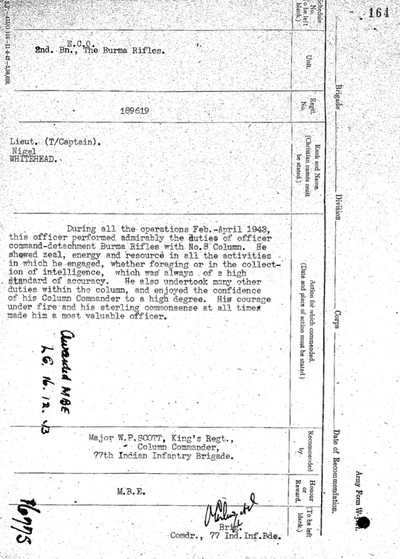

Major Scott recognised the valuable contribution made by Nigel Whitehead on Operation Longcloth and recommended that he receive the award of a MBE:

OPERATIONS IN BURMA - February-April 1943

189619 Lieutenant (temporary Captain) Nigel Whitehead

Action for which recommended :

During all the operations from February through April 1943, this officer performed admirably the duties of officer commanding the Burma Rifles detachment with No. 8 Column. He showed real energy and resource in all the activities in which he engaged, whether foraging for food or in the collection of intelligence, which was always of a high standard of accuracy. He also undertook many other duties within the column, and enjoyed the confidence of his Column Commander to a high degree. His courage under fire and his sterling commonsense at all times made him a most valuable officer.

Award Recommended By: Major W.P.Scott, King's Regt.

Column Commander, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Honour or Reward-M.B.E. (Military).

Signed By-

Brigadier O.C. Wingate

Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Gazetted 16.12.1943.

Seen below are some images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

About eight days after we crossed the Shweli River, it was decided we should split up into dispersal groups of about 60 men under 1 or 2 officers and choosing our own route, make our way back to India. My party formed part of the group under Captain Whitehead of the Burma Rifles.

I had inherited six British Other Ranks after the incident at Baw village. These were added to my original four B.O.R.'s and the 12 Gurkha muleteers already under my command. Our group then volunteered to take with them the wounded men from the Column and to put these into a friendly village near or in Kachin country. With these wounded were a number of stretcher bearers and all of these were from 16 Platoon.

The dispersal group moved away from the Irrawaddy and two days later we managed to place the wounded in a native Kachin/Shan village; whether they were looked after properly, I don't to know.

The following day our group was ambushed by a mixed force of Burmese and Japanese. Our rendezvous in case of attack, was a half-mile due North of our position. I made the R.V. in the company of two Burma Riflemen and a V.C.O. (Jemadar Ah Di) and waited there all night. We often heard firing from the direction of a village about a mile away.

We marched on for three days, passing between enemy held villages along the Sinlumkaba Tract. We had no food, but dare not enter any of these villages as we crossed over the Bhamo-Mandalay motor road. One evening we came across a village and entered cautiously to enquire about some food. We found the remainder of our dispersal party already there, less Captain Whitehead and Flight-Lieutenant Wheatley who had been lost at the ambush and the Medical Orderly who had been handed over to the Japanese by the Shans.

I took command of the party and we pushed on north, averaging approximately 12 miles a day. Progress was slow due to nature of the country and terrain. The men began to tire, for weeks of surviving on a diet of rice, bamboo leaves, roots and dried monkey meat when we could get it. Besides this, everyone was suffering to a greater or lesser degree, from fever, dysentery and septic jungle sores. Our uniforms were just rags and many men had no protective footwear. Our route was leading us into the hills of up to 5,500 feet and the men were becoming lethargic. I remember that sentry duty whilst guarding the camp at night became extremely arduous at this time.

Lt. Stuart-Jones had begun Operation Longcloth within the ranks of 4 Column, but had been separated from his unit when it was ambushed by a large Japanese patrol on the 4th March. He had the good fortunate to bump into Major Scott and 8 Column some time later and had journeyed with them for the rest of the operation up until dispersal was called. Lt. Stuart-Jones and his men finally reached Allied held territory in early July 1943 and in his letter written after the war, he recognised the invaluable contribution made by Jemadar Ah Di of the Burma Rifles in achieving this goal:

Having no maps of the area in which we were travelling and only one compass, I had to rely on the knowledge and skill of my Kachin Jemadar, Ah Di of the Burma Rifles. His fluency in the various dialects made him invaluable in obtaining information from villagers. In the hills opposite the east of Bhamo I lost one Kachin and two Karen riflemen, who decided to take their chances and head home. It was also at this time that we picked up Lieutenant Smyly of 5 Column, who was in a very weak state and barely able to walk. He was left in a friendly village, with Jemadar Ah Di instructing the villagers that they would be held responsible for the officers safety.

Everyone was now in a very weak state and at this time the Gurkhas were on average, sticking at it better than the British soldiers and the Burma Rifles. Through the efforts of Ah Di, we hired a Kachin guide who had once been with the Burma Frontier Force. He led us north and entered all villages first to check for Japanese patrols and to acquire rice to supplement our meagre rations. The Kachins in this area were very poor indeed and fearful of the Japs, but on the whole extremely friendly towards us.

There is no further information available, as to the fate of Captain Whitehead and the other officers lost during the ambush on or around the 18th April 1943. We know that Nigel Whitehead made it safely back to India after Operation Longcloth, by the fact of his continued service during the Burma Campaign. Medical Officer, Captain J.D.S. Heathcote and Lt. Hamilton-Bryan do not appear on any listing for soldiers killed in action in Burma, or indeed being held as prisoners of war. So it must be assumed that both men returned safely to Allied held territory in 1943. Flight-Lieutenant Kenneth Wheatley of the Royal Canadian Air Force, did have the misfortune of falling into Japanese hands after being captured on the 27th April near the Burmese railway town of Mohnyin. Kenneth spent just over two years as a POW inside Rangoon Jail, before being liberated by British troops at the village of Waw near Pegu, on the 29th April 1945.

Major Scott recognised the valuable contribution made by Nigel Whitehead on Operation Longcloth and recommended that he receive the award of a MBE:

OPERATIONS IN BURMA - February-April 1943

189619 Lieutenant (temporary Captain) Nigel Whitehead

Action for which recommended :

During all the operations from February through April 1943, this officer performed admirably the duties of officer commanding the Burma Rifles detachment with No. 8 Column. He showed real energy and resource in all the activities in which he engaged, whether foraging for food or in the collection of intelligence, which was always of a high standard of accuracy. He also undertook many other duties within the column, and enjoyed the confidence of his Column Commander to a high degree. His courage under fire and his sterling commonsense at all times made him a most valuable officer.

Award Recommended By: Major W.P.Scott, King's Regt.

Column Commander, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Honour or Reward-M.B.E. (Military).

Signed By-

Brigadier O.C. Wingate

Commander 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Gazetted 16.12.1943.

Seen below are some images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After Operation Longcloth, Captain Nigel Whitehead returned to the ranks of the 2nd Burma Rifles, who were now stationed at Jhansi in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. He had spent sometime recuperating from the rigours of the first Wingate expedition, including a spell in the British Military Hospital at Lucknow. In November 1943, he was posted once more to the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, this time under the overall command of Brigadier Mike Calvert and began training for the second Chindit expedition, Operation Thursday.

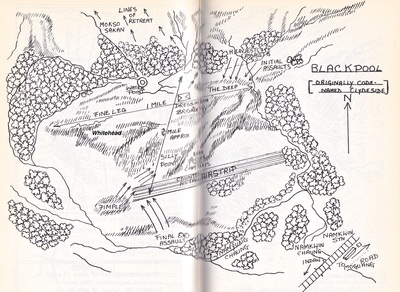

Whitehead teamed up again with Walter Purcell Scott, now promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and in charge of the King's Regiment's contingent in the Brigade, numbered as 81 and 82 Column. The King's were the first Chindits to enter Burma on the 5th March 1944, landing in gliders as the spearhead of the invasion and securing the perimeter of the original stronghold, codenamed Broadway. Later, in early May, Columns 81 and 82 moved north to assist with the construction and defence of another Chindit block called Blackpool.

Blackpool did not prove successful as a Chindit stronghold and was soon under intensive enemy mortar, machine gun and artillery fire. On the 23rd May, the Japanese broke through the outer-perimeter of the block and attacked the area where the King's were positioned. This was a hillock given the codename of Whitehead, in honour of the officer charged with its defence. This was of course, none other than Captain Nigel Whitehead of the 2nd Burma Rifles. Over the course of the next 24 hours the two sides battled ferociously over this territory, which was now turned to liquid mud by the torrential monsoon rains.

From the book, War in the Wilderness:

All around the perimeter the enemy came at us again and again remorselessly and relentlessly, taking all the devastating fire we poured into them and still coming back for more. We were taking heavy casualties, but their casualties must have been horrendous. Some of the fighting was quite desperate. Captain Whitehead's patrol had been relieved on the feature carrying his name during the evening of 23rd May, but then found they could not withdraw. They fought on until 17.00 hours the following day, completely surrounded, until their ammunition ran out.

By a stoke of incredible good fortune, at that very moment a parachute container of ammunition, from the very last supply drop, drifted down and landed at their feet. The men continued to resist until dark. The twelve survivors of the once 35 man patrol then slipped through the Japanese lines and made for what was known as Basha Ridge.

Unfortunately, Blackpool Block was not in operation for very much longer and in spite of desperate and tenacious defence by the men of 111 Brigade, the position was overwhelmed on the 25th May and had to be abandoned. The surviving Chindits marched wearily away to the north, making very slow headway across the flooded terrain and often knee-deep in mud. It must be presumed that Captain Whitehead was marching with them.

Later in the war, Whitehead, now with the rank of Major served as Liaison Officer (Burma Section) at the India Command General Head Quarters in Delhi. He also held the position of Deputy Assistant Adjutant for the Burma Section at G.H.Q. (Delhi) during October 1945. In 1970, Major Whitehead became a Director on the staff of Steel Brothers in Rangoon. On returning to the United Kingdom after his retirement, Nigel Whitehead sadly passed away in October 1982, with his death being recorded at Ilkeston in Derbyshire.

To conclude this story, seen below are two images of the Blackpool Stronghold. Firstly, a contemporary sketch map showing the various strategic positions within the Block and secondly, a panoramic photograph taken of the Block location in March 2008. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page. Many thanks go to Steve Rothwell for the information in relation to Nigel Whitehead's military and civilian career in Burma.

Whitehead teamed up again with Walter Purcell Scott, now promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and in charge of the King's Regiment's contingent in the Brigade, numbered as 81 and 82 Column. The King's were the first Chindits to enter Burma on the 5th March 1944, landing in gliders as the spearhead of the invasion and securing the perimeter of the original stronghold, codenamed Broadway. Later, in early May, Columns 81 and 82 moved north to assist with the construction and defence of another Chindit block called Blackpool.

Blackpool did not prove successful as a Chindit stronghold and was soon under intensive enemy mortar, machine gun and artillery fire. On the 23rd May, the Japanese broke through the outer-perimeter of the block and attacked the area where the King's were positioned. This was a hillock given the codename of Whitehead, in honour of the officer charged with its defence. This was of course, none other than Captain Nigel Whitehead of the 2nd Burma Rifles. Over the course of the next 24 hours the two sides battled ferociously over this territory, which was now turned to liquid mud by the torrential monsoon rains.

From the book, War in the Wilderness:

All around the perimeter the enemy came at us again and again remorselessly and relentlessly, taking all the devastating fire we poured into them and still coming back for more. We were taking heavy casualties, but their casualties must have been horrendous. Some of the fighting was quite desperate. Captain Whitehead's patrol had been relieved on the feature carrying his name during the evening of 23rd May, but then found they could not withdraw. They fought on until 17.00 hours the following day, completely surrounded, until their ammunition ran out.

By a stoke of incredible good fortune, at that very moment a parachute container of ammunition, from the very last supply drop, drifted down and landed at their feet. The men continued to resist until dark. The twelve survivors of the once 35 man patrol then slipped through the Japanese lines and made for what was known as Basha Ridge.

Unfortunately, Blackpool Block was not in operation for very much longer and in spite of desperate and tenacious defence by the men of 111 Brigade, the position was overwhelmed on the 25th May and had to be abandoned. The surviving Chindits marched wearily away to the north, making very slow headway across the flooded terrain and often knee-deep in mud. It must be presumed that Captain Whitehead was marching with them.

Later in the war, Whitehead, now with the rank of Major served as Liaison Officer (Burma Section) at the India Command General Head Quarters in Delhi. He also held the position of Deputy Assistant Adjutant for the Burma Section at G.H.Q. (Delhi) during October 1945. In 1970, Major Whitehead became a Director on the staff of Steel Brothers in Rangoon. On returning to the United Kingdom after his retirement, Nigel Whitehead sadly passed away in October 1982, with his death being recorded at Ilkeston in Derbyshire.

To conclude this story, seen below are two images of the Blackpool Stronghold. Firstly, a contemporary sketch map showing the various strategic positions within the Block and secondly, a panoramic photograph taken of the Block location in March 2008. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page. Many thanks go to Steve Rothwell for the information in relation to Nigel Whitehead's military and civilian career in Burma.

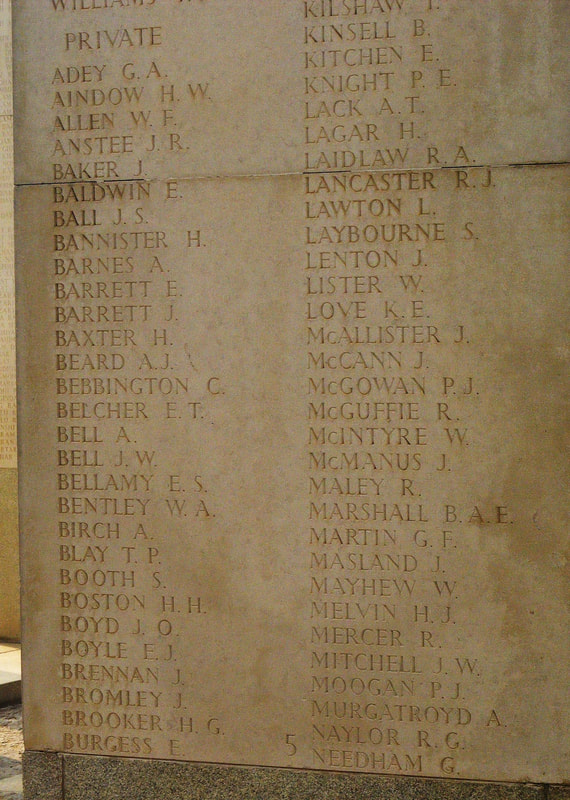

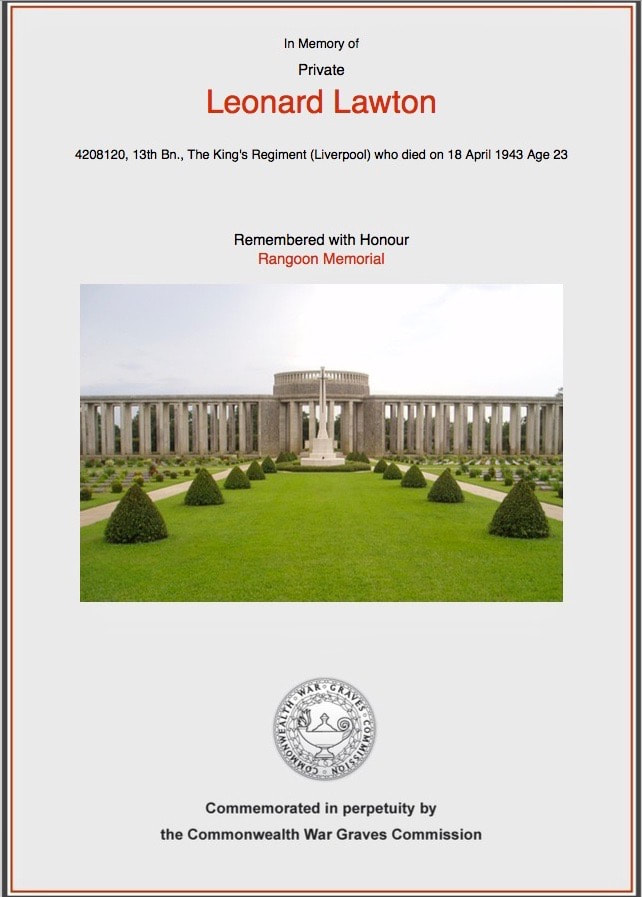

Pte. Leonard Lawton.

Pte. Leonard Lawton.

Update 20/07/2019.

I was delighted to receive an email enquiry from Veronica Scully in relation to the Chindit, Pte. Leonard Lawton, who is mentioned in the above narrative as being one of the wounded men taken by Captain Whitehead and left in a friendly Kachin village around the 18th April 1943. Veronica had made contact in the first instance with author Tony Redding:

Dear Tony,

My Uncle 4208120 Leonard Lawton, 13th Battalion, The Kings Regiment (Liverpool) fought and died during 1943 in Burma and was also with the Chindits. Could you let me know if there are any remembrance services in November that may include the Burma campaign. I would like if possible to represent my Uncle if there are any groups set up for the march through Whitehall. My father never knew what had happened to his older brother, so I am hoping I will be able to find out more through the Chindit Society.

Many thanks, Mrs. Veronica Scully.

I was pleased to be able to give Veronica quite a bit of detail about her uncle Leonard:

Dear Veronica,

I was delighted to receive your information via Tony today. I have been studying the men of the 13th King's, one of whom was my own maternal grandfather, for around 10 years now. I have some information about Leonard in my files, including what actually happened to him in April 1943. I will begin with a brief run down of the events leading to him being listed as missing.

Leonard had originally enlisted in to the Army before being posted to the 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment and had begun his Army service with the Royal Welch Fusiliers. He arrived in India with the Fusiliers and was sent to join the 13th King's at a place called Saugor on the 30th September 1942 and began his Chindit training.

He was allocated to No. 8 Column on Operation Longcloth, which was the first Wingate expedition into Burma in February 1943. Around the 12th April, his platoon was involved in a fight with the Japanese near the Irrawaddy River and Leonard was wounded in the leg from a gunshot. After the engagement was over, he was carried away on a stretcher to be treated by the Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote.

From the 8 Column War diary dated 12th April 1943:

On 12th April, the front of the column was approaching a newly built bamboo bridge over a chaung (small river) when they bumped into a couple of Japs who turned and bolted back into the jungle. Intense firing broke out and Sergeant Bridgeman and Private Beard were killed, while Privates Lawton and Witheridge were both seriously wounded.

Most of the column turned around and disappeared along the track they had come down, leaving Major Scott and a small party isolated. It was not until the evening that the column reassembled and it was discovered that Lieutenant Horncastle and 14 others were missing. It was thought that they might have moved off as a separate party.

The column was up and moving at 0430 hours the next morning. The going was quite good but they now had three wounded on stretchers to carry with them. Major Scott and Lieutenant Colonel Cooke held an officers' conference and it was decided that they would request one last supply drop before breaking up into dispersal groups to cross the Irrawaddy.

After a few days, it was decided to split the column up into small parties of around 30-40 in each. Captain Heathcote and another officer, Captain Whitehead took care of all the sick and wounded men, with the intention of taking them to a friendly Burmese village and leaving them there to hopefully recover. Unfortunately, the men already knew, that if they became ill or could not march, they would be left in this way in order to allow the fitter men to continue with the expedition.

On the 16th April, Leonard and the other sick and wounded men were left in a village close to the Irrawaddy River in the general area around Bhamo. The name of the actual village was not recorded. Sadly, Leonard and the other men were never seen again and the date 18th April, was given as the day he was last seen alive and was eventually used by the Army authorities as his recorded date of death. I'm afraid to say, that most wounded or sick Chindits left in this way were often turned over to the Japanese by the villagers involved, who feared violent reprisals from the invaders if they were found to be harbouring British soldiers.

Leonard is remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery, located on the northern outskirts of Rangoon. This is a memorial for soldiers from the Burma campaign that have no known grave. I have a photograph of the panel on which Leonard is mentioned, I will send this over with some other documents and papers. This is all I can really tell you I'm afraid.

Veronica then came back in reply:

Dear Stephen,

Thank you so much, I am extremely grateful for all your research on my Uncle. This is rather amazing to learn after all these years, as my father never really knew anything. I would very much appreciate you including a photograph of Leonard on your web site if that’s ok. I will send this over in my next email. Sadly I can’t stretch to going to the memorial in Burma just yet, but I hope to go one day as a promise to my late father, who was Leonard’s younger brother and also fought during WW2 at Arnhem.

I'm sorry to say that I don't know much about Uncle Leonard as my Dad (Hubert Lawton) did not speak a great deal about the war or his older brother. I know they were born and bred in Kidsgrove, Staffordshire and that they were the sons of William and Rachel Lawton and that their father was a face coal miner.

Kind regards, Veronica.

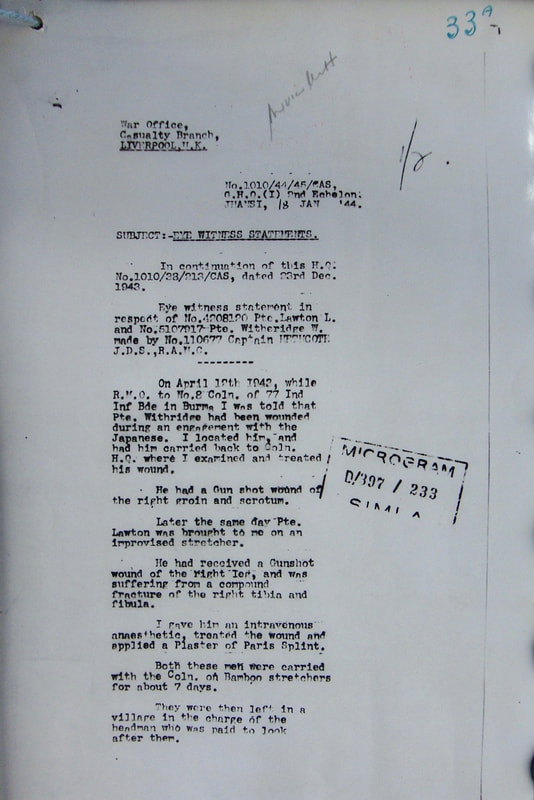

Seen below is a transcription of an eye witness statement, dated 18th January 1944 and written by Captain J.D.S. Heathcote, the Medical Officer from No. 8 Column who tended to Leonard Lawton's wounds in April 1943. Captain Heathcote states that:

On April 12th 1943, whilst the Medical Officer to No. 8 Column, 77 Indian Infantry Brigade in Burma, I was told that Pte. Witheridge had been wounded during an engagement with the Japanese. I located him and had him carried back to the Column Head Quarters, where I examined and treated his wound. He had a gun shot wound of the right groin and scrotum.

Later the same day, Pte. Lawton was brought to me on an improvised stretcher. He had received a gun shot wound of the right leg and was suffering from a compound fracture of the right tibia and fibula. I gave him an intravenous anaesthetic, treated the wound and applied a plaster of Paris splint.

Both these men were carried with the Column on bamboo stretchers for about seven days. They were then left in a village in the charge of the Headman, who was paid to look after them.

I was delighted to receive an email enquiry from Veronica Scully in relation to the Chindit, Pte. Leonard Lawton, who is mentioned in the above narrative as being one of the wounded men taken by Captain Whitehead and left in a friendly Kachin village around the 18th April 1943. Veronica had made contact in the first instance with author Tony Redding:

Dear Tony,

My Uncle 4208120 Leonard Lawton, 13th Battalion, The Kings Regiment (Liverpool) fought and died during 1943 in Burma and was also with the Chindits. Could you let me know if there are any remembrance services in November that may include the Burma campaign. I would like if possible to represent my Uncle if there are any groups set up for the march through Whitehall. My father never knew what had happened to his older brother, so I am hoping I will be able to find out more through the Chindit Society.

Many thanks, Mrs. Veronica Scully.

I was pleased to be able to give Veronica quite a bit of detail about her uncle Leonard:

Dear Veronica,

I was delighted to receive your information via Tony today. I have been studying the men of the 13th King's, one of whom was my own maternal grandfather, for around 10 years now. I have some information about Leonard in my files, including what actually happened to him in April 1943. I will begin with a brief run down of the events leading to him being listed as missing.

Leonard had originally enlisted in to the Army before being posted to the 13th Battalion, the King's Regiment and had begun his Army service with the Royal Welch Fusiliers. He arrived in India with the Fusiliers and was sent to join the 13th King's at a place called Saugor on the 30th September 1942 and began his Chindit training.

He was allocated to No. 8 Column on Operation Longcloth, which was the first Wingate expedition into Burma in February 1943. Around the 12th April, his platoon was involved in a fight with the Japanese near the Irrawaddy River and Leonard was wounded in the leg from a gunshot. After the engagement was over, he was carried away on a stretcher to be treated by the Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote.

From the 8 Column War diary dated 12th April 1943:

On 12th April, the front of the column was approaching a newly built bamboo bridge over a chaung (small river) when they bumped into a couple of Japs who turned and bolted back into the jungle. Intense firing broke out and Sergeant Bridgeman and Private Beard were killed, while Privates Lawton and Witheridge were both seriously wounded.

Most of the column turned around and disappeared along the track they had come down, leaving Major Scott and a small party isolated. It was not until the evening that the column reassembled and it was discovered that Lieutenant Horncastle and 14 others were missing. It was thought that they might have moved off as a separate party.

The column was up and moving at 0430 hours the next morning. The going was quite good but they now had three wounded on stretchers to carry with them. Major Scott and Lieutenant Colonel Cooke held an officers' conference and it was decided that they would request one last supply drop before breaking up into dispersal groups to cross the Irrawaddy.

After a few days, it was decided to split the column up into small parties of around 30-40 in each. Captain Heathcote and another officer, Captain Whitehead took care of all the sick and wounded men, with the intention of taking them to a friendly Burmese village and leaving them there to hopefully recover. Unfortunately, the men already knew, that if they became ill or could not march, they would be left in this way in order to allow the fitter men to continue with the expedition.

On the 16th April, Leonard and the other sick and wounded men were left in a village close to the Irrawaddy River in the general area around Bhamo. The name of the actual village was not recorded. Sadly, Leonard and the other men were never seen again and the date 18th April, was given as the day he was last seen alive and was eventually used by the Army authorities as his recorded date of death. I'm afraid to say, that most wounded or sick Chindits left in this way were often turned over to the Japanese by the villagers involved, who feared violent reprisals from the invaders if they were found to be harbouring British soldiers.

Leonard is remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery, located on the northern outskirts of Rangoon. This is a memorial for soldiers from the Burma campaign that have no known grave. I have a photograph of the panel on which Leonard is mentioned, I will send this over with some other documents and papers. This is all I can really tell you I'm afraid.

Veronica then came back in reply:

Dear Stephen,

Thank you so much, I am extremely grateful for all your research on my Uncle. This is rather amazing to learn after all these years, as my father never really knew anything. I would very much appreciate you including a photograph of Leonard on your web site if that’s ok. I will send this over in my next email. Sadly I can’t stretch to going to the memorial in Burma just yet, but I hope to go one day as a promise to my late father, who was Leonard’s younger brother and also fought during WW2 at Arnhem.

I'm sorry to say that I don't know much about Uncle Leonard as my Dad (Hubert Lawton) did not speak a great deal about the war or his older brother. I know they were born and bred in Kidsgrove, Staffordshire and that they were the sons of William and Rachel Lawton and that their father was a face coal miner.

Kind regards, Veronica.

Seen below is a transcription of an eye witness statement, dated 18th January 1944 and written by Captain J.D.S. Heathcote, the Medical Officer from No. 8 Column who tended to Leonard Lawton's wounds in April 1943. Captain Heathcote states that:

On April 12th 1943, whilst the Medical Officer to No. 8 Column, 77 Indian Infantry Brigade in Burma, I was told that Pte. Witheridge had been wounded during an engagement with the Japanese. I located him and had him carried back to the Column Head Quarters, where I examined and treated his wound. He had a gun shot wound of the right groin and scrotum.

Later the same day, Pte. Lawton was brought to me on an improvised stretcher. He had received a gun shot wound of the right leg and was suffering from a compound fracture of the right tibia and fibula. I gave him an intravenous anaesthetic, treated the wound and applied a plaster of Paris splint.

Both these men were carried with the Column on bamboo stretchers for about seven days. They were then left in a village in the charge of the Headman, who was paid to look after them.

Shown below is a gallery of images in relation to this update, including Captain Heathcote's actual witness report. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To view the CWGC details for Pte. Leonard Lawton, please click on the following link:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2515790/lawton,-leonard/

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2515790/lawton,-leonard/

Copyright © Steve Fogden, September 2016.