Flight Lieutenant Kenneth Wheatley

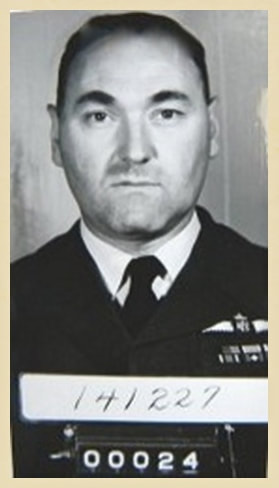

Flight Lieutenant Kenneth M. Wheatley.

Flight Lieutenant Kenneth M. Wheatley.

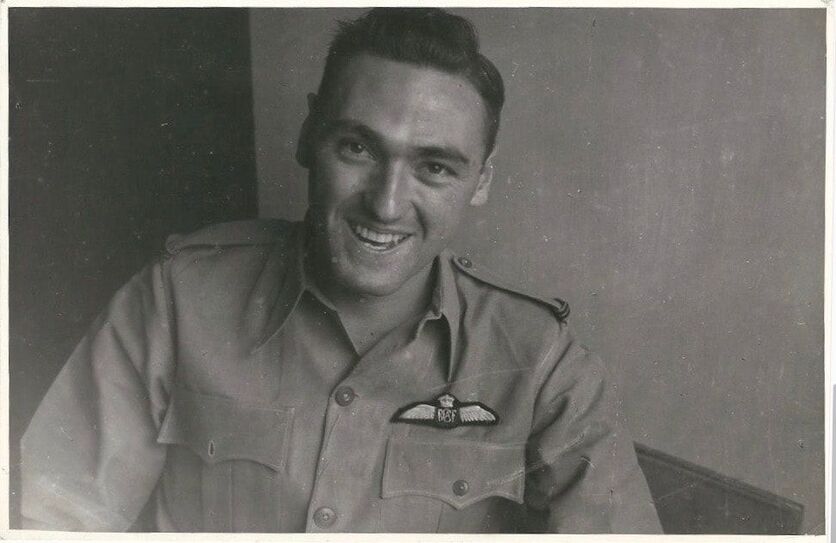

Kenneth Maertell Wheatley, born on the 21st September 1920, was the son of Frank and Alice Wheatley from Banff in the province of Alberta in Canada. In his early working career, Kenneth spent three years as a Life Guard before following in his father's footsteps and working as a coal miner in 1939. He enlisted into the Royal Canadian Air force at Calgary on the 26th October 1940 and was posted to the RCAF No. 2 Manning Depot at Brandon, Manitoba.

Kenneth was promoted to the rank of Leading Aircraftman on the 28th January 1941, just before being posted to the No. 11 Service Flying Training School at Yorkton in Saskatchewan. He graduated and was promoted to Sergeant on the 4th July and then sent to No. 58 Operational Training Unit on the 27th August. On the 30th October, Ken was posted to No. 17 Squadron RAF, with whom he left the United Kingdom in December 1941 bound for North Africa. The squadron only remained in Egypt for one month, before being posted to the Far East.

Sergeant (J15781) Ken Wheatley was promoted to Flight Lieutenant on the 1st January 1943 and flew Hurricanes out of Calcutta with No. 17 Squadron from early 1942 until January 1943. This amounted to 110 operational flying hours spread over 55 sorties and crossing the border into Burma many times.

Fellow 17 Squadron officer, Wing Commander Cedric 'Bunny' Stone DFC, remembered one incident when flying alongside Ken on the 25th February 1942:

On the morning of the 25th February, I took off with six Hurricanes to carry out an offensive patrol on the Moulmein-Martaban coastline. As usual, Sergeant Wheatley was my number two. We had come to know the Martaban estuary very well over the past weeks and hoped to find some shipping we could beat up.

We cruised at around 5000 feet and in formation stepped up into the sun, undulating slightly in a loose line abreast. The sun sparkled on the dark blue cobalt waters as we left the coast and headed for the estuary. I kept a wary eye around the clock and I knew that five other pairs of eyes were doing the same thing. As we approached Martaban, then occupied by the Japanese, situated on the north bank where the estuary broadens into the Gulf, we spotted a large river boat steaming on a course for the Sittang River. We were in the perfect position for strafing. I closed my hood and turned on the gun button and the reflector sight. I went into a swallow dive, increasing speed; I told the others on the radio to follow astern and I went on the attack.

As I descended, a cannon mounted on the deck of the boat winked at me. I opened up on the cannon, whose crew promptly collapsed, with one man falling over the side. I kept my finger on the button and raked the boat from stem to stern. The boat was full of Japanese troops in full war-gear. I watched Sergeant Wheatley going in as I circled up and around. Then the boat appeared to burst into a white sheet of flame from the funnel to the stern. The others went in and smoke started to billow up, casting a long shadow over the glassy waters beneath. As I went in for a second time, figures appeared like fleas, disturbed by powder and jumping from a dog's fur. Some disappeared beneath the water, others popped up to be extinguished by the spray kicked up by eight guns delivering 160 bullets per second from each Hurricane.

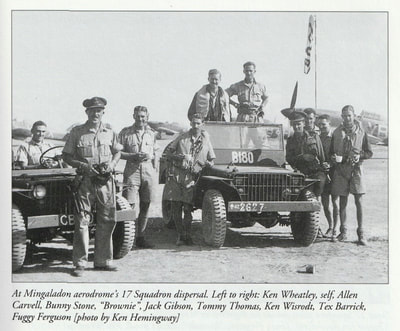

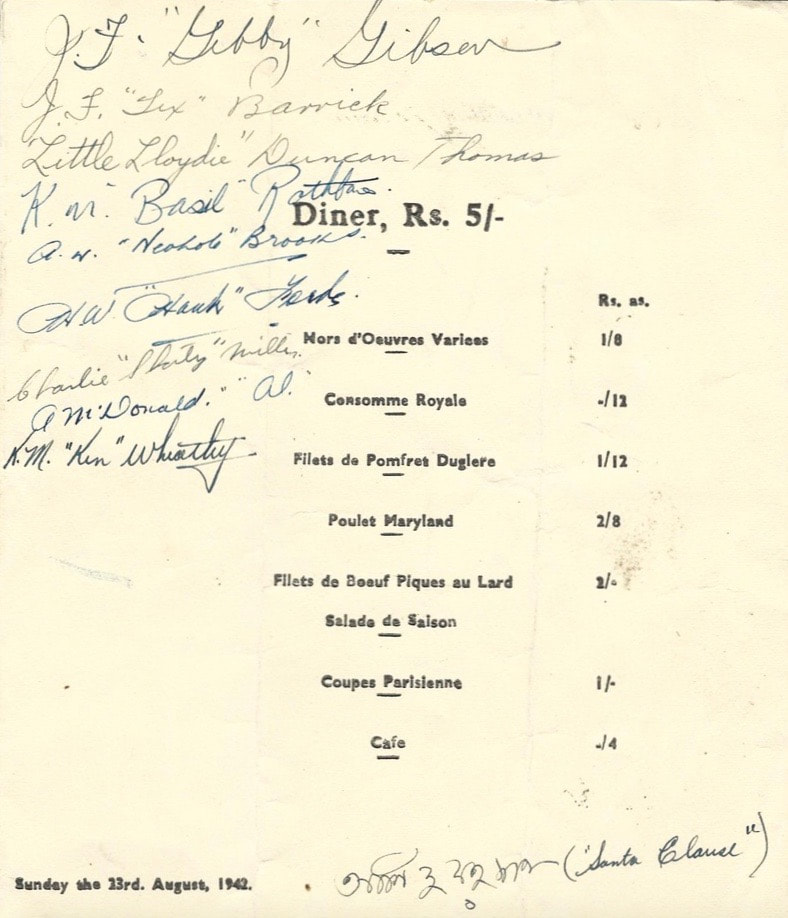

Seen below are two photographs taken from the book, Hurricanes Over Burma, by Wing Commander Bunny Stone. These show pilots from No. 17 Squadron including Ken Wheatley at Mingaladon Aerodrome in late February 1942 and just before the Japanese took control of the area around Rangoon. Featured in the first photograph is Flight Lieutenant Jack Gibson from South Carolina in the United States of America. Jack Gibson had travelled north to Canada early in the war in order to enlist into the RCAF and serve with the RAF against the German Luftwaffe. He then volunteered for the first Wingate expedition, serving on Operation Longcloth as Air Liaison Officer for No. 4 Column in 1943. It now seems highly likely that Jack Gibson and Ken Wheatley left No. 17 Squadron together in order to volunteer for the Chindits.

Ken Wheatley was one of three Canadians to take part on the first Chindit expedition, the others were: Captain Roy McKenzie of the Gurkha Rifles and Major George Vermilyea Faulkner a Medical Officer from Foxboro in the province of Ontario. Ken was was posted as Air Liaison to No. 8 Column on Operation Longcloth, serving under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment. Air Liaison duties included: radio communications with Air Supply at Rear Base, ground to air signalling during supply drops in the Burmese jungle and the selection and preparation of all supply drop locations, known as DZ's. Their role on Operation Longcloth proved to be vital and on the whole their performance was excellent. This is what Brigadier Orde Wingate thought about their efforts in 1943:

The most important thing to note is that SD (Supply Drop) was a brilliant and unexpected success in 1943. All kinds of gloomy prophesies had been made by the the experts. None was fulfilled. The RAF officers and men provided were of the highest quality. The course of this particular operation did not afford them nearly enough scope to learn as was first hoped, nevertheless they were of great value to the Columns. It is essential to have RAF personnel with Long Range Penetration columns, as they afford the unit: continual air co-operation with rear base, vital air intelligence and the exploitation for calling in strategic bombing raids etc. on previously unknown enemy positions.

Please click on either image to bring forward on the page.

Kenneth was promoted to the rank of Leading Aircraftman on the 28th January 1941, just before being posted to the No. 11 Service Flying Training School at Yorkton in Saskatchewan. He graduated and was promoted to Sergeant on the 4th July and then sent to No. 58 Operational Training Unit on the 27th August. On the 30th October, Ken was posted to No. 17 Squadron RAF, with whom he left the United Kingdom in December 1941 bound for North Africa. The squadron only remained in Egypt for one month, before being posted to the Far East.

Sergeant (J15781) Ken Wheatley was promoted to Flight Lieutenant on the 1st January 1943 and flew Hurricanes out of Calcutta with No. 17 Squadron from early 1942 until January 1943. This amounted to 110 operational flying hours spread over 55 sorties and crossing the border into Burma many times.

Fellow 17 Squadron officer, Wing Commander Cedric 'Bunny' Stone DFC, remembered one incident when flying alongside Ken on the 25th February 1942:

On the morning of the 25th February, I took off with six Hurricanes to carry out an offensive patrol on the Moulmein-Martaban coastline. As usual, Sergeant Wheatley was my number two. We had come to know the Martaban estuary very well over the past weeks and hoped to find some shipping we could beat up.

We cruised at around 5000 feet and in formation stepped up into the sun, undulating slightly in a loose line abreast. The sun sparkled on the dark blue cobalt waters as we left the coast and headed for the estuary. I kept a wary eye around the clock and I knew that five other pairs of eyes were doing the same thing. As we approached Martaban, then occupied by the Japanese, situated on the north bank where the estuary broadens into the Gulf, we spotted a large river boat steaming on a course for the Sittang River. We were in the perfect position for strafing. I closed my hood and turned on the gun button and the reflector sight. I went into a swallow dive, increasing speed; I told the others on the radio to follow astern and I went on the attack.

As I descended, a cannon mounted on the deck of the boat winked at me. I opened up on the cannon, whose crew promptly collapsed, with one man falling over the side. I kept my finger on the button and raked the boat from stem to stern. The boat was full of Japanese troops in full war-gear. I watched Sergeant Wheatley going in as I circled up and around. Then the boat appeared to burst into a white sheet of flame from the funnel to the stern. The others went in and smoke started to billow up, casting a long shadow over the glassy waters beneath. As I went in for a second time, figures appeared like fleas, disturbed by powder and jumping from a dog's fur. Some disappeared beneath the water, others popped up to be extinguished by the spray kicked up by eight guns delivering 160 bullets per second from each Hurricane.

Seen below are two photographs taken from the book, Hurricanes Over Burma, by Wing Commander Bunny Stone. These show pilots from No. 17 Squadron including Ken Wheatley at Mingaladon Aerodrome in late February 1942 and just before the Japanese took control of the area around Rangoon. Featured in the first photograph is Flight Lieutenant Jack Gibson from South Carolina in the United States of America. Jack Gibson had travelled north to Canada early in the war in order to enlist into the RCAF and serve with the RAF against the German Luftwaffe. He then volunteered for the first Wingate expedition, serving on Operation Longcloth as Air Liaison Officer for No. 4 Column in 1943. It now seems highly likely that Jack Gibson and Ken Wheatley left No. 17 Squadron together in order to volunteer for the Chindits.

Ken Wheatley was one of three Canadians to take part on the first Chindit expedition, the others were: Captain Roy McKenzie of the Gurkha Rifles and Major George Vermilyea Faulkner a Medical Officer from Foxboro in the province of Ontario. Ken was was posted as Air Liaison to No. 8 Column on Operation Longcloth, serving under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment. Air Liaison duties included: radio communications with Air Supply at Rear Base, ground to air signalling during supply drops in the Burmese jungle and the selection and preparation of all supply drop locations, known as DZ's. Their role on Operation Longcloth proved to be vital and on the whole their performance was excellent. This is what Brigadier Orde Wingate thought about their efforts in 1943:

The most important thing to note is that SD (Supply Drop) was a brilliant and unexpected success in 1943. All kinds of gloomy prophesies had been made by the the experts. None was fulfilled. The RAF officers and men provided were of the highest quality. The course of this particular operation did not afford them nearly enough scope to learn as was first hoped, nevertheless they were of great value to the Columns. It is essential to have RAF personnel with Long Range Penetration columns, as they afford the unit: continual air co-operation with rear base, vital air intelligence and the exploitation for calling in strategic bombing raids etc. on previously unknown enemy positions.

Please click on either image to bring forward on the page.

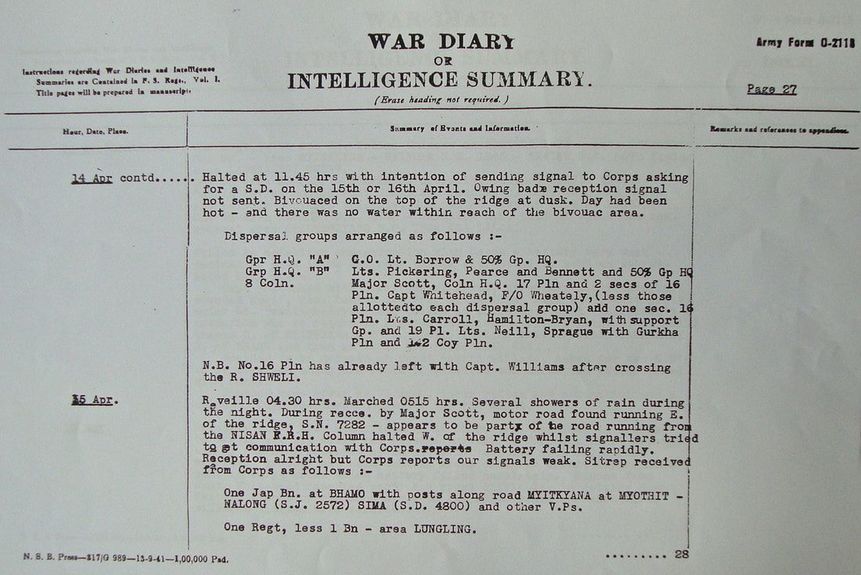

Flight Lieutenant Wheatley is mentioned on two occasions within the pages of 8 Column's war diary:

On the 3rd April, 8 Column were waiting to cross the treacherously fast flowing Shweli River. Two days previously, on their first attempt to cross the river, Captain Williams and his platoon had succeeded in getting over. This group had then become separated after the next section of men accidentally lost control of the boats used and were washed away downstream. After coming to terms with this latest disaster, Major Scott called up the RAF to drop more dinghies to the column and these duly arrived the next day. The diary recorded:

Signal sent to Corps (2nd April) asking for two RAF dinghies and two Recce boats to be dropped to us. The building of rafts continued and orders were issued for a crossing to be carried out at all costs if no supply drop of boats could be made. At 18.00 hours the boats and 200 lifebelts and two days rations per man were delivered. At dusk the crossing began and continued on until 09.00 hours the following day. All ranks and our two mules went over. Excellent work had been done by F/Lt. Wheatley and Lt. Gillow in swimming the river and preparing the far bank.

It was decided to split the column into three dispersal groups after crossing the Shweli, this was to ensure that if the Chindits met with any enemy interference on the opposite bank, or on their return journey to India, they would not all be in one place and easily engaged or captured.

A few days later, the three groups re-formed at a pre-arranged rendezvous and began their approach towards the Irrawaddy, close to where the river meanders near the village of Myale.

On 12th April, the front of the column was approaching a newly built bamboo bridge over a chaung when they bumped into a couple of Japanese who turned and bolted back into the jungle. Intense firing broke out and Sergeant Bridgeman and Private Beard were killed, while Privates Lawton and Witheridge were both seriously wounded. Most of the column turned around and disappeared along the track they had come down, leaving Major Scott and a small party of men isolated for a short time. It was not until the evening that the column reassembled and it was discovered that Lieutenant Horncastle and 14 others were missing. It was thought that they might have subsequently moved off as a separate party.

The column was up and moving at 0430 hours the next morning. The going was quite good but they now had three wounded on stretchers to carry with them. Major Scott and Lieutenant Colonel Cooke held an officers' conference and it was decided that they would request one last supply drop (presumably organised by Flight Lieutenant Wheatley) before breaking up into dispersal groups to cross the Irrawaddy. The dispersal groups were arranged as follows:

Lieutenant Colonel Cooke, Lieutenant Borrow and half of Group Headquarters;

Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and the other half of Group Headquarters;

Major Scott with Column Headquarters, 17 Platoon and two sections of 16 Platoon;

Captain Whitehead and his Burma Rifles less those already allocated to assist the other dispersal groups, plus Flying Officer Wheatley and a section of 16 Platoon;

Lieutenants Carroll, Hamilton-Bryan with Support Group and 19 Platoon;

Lieutenants Neill and Sprague with the Gurkha Platoon and 142 Commando Platoon.

On 15th April, Captain Whitehead and his dispersal group, together with the stretcher party under Sergeant Parsons and the Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote, left the column. They planned to move to the east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkyina to Fort Hertz. If this plan failed they would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then go west towards the Chindwin.

Captain Whitehead's group, including Ken Wheatley, was considerably larger than most, being made up of around 60-70 men. The reason for this was that he had agreed to take with him a number of sick and wounded men from No. 16 Platoon, many of these soldiers needed to be carried on stretchers and had been battle casualties at the village of Baw on the 23rd March. Whitehead's intention was to find a friendly Kachin village in which to leave these men and then take the rest of his party back to India. After several days of searching no suitable village was found, in fact many of the villages listed on the Captain's map no longer seemed to exist.

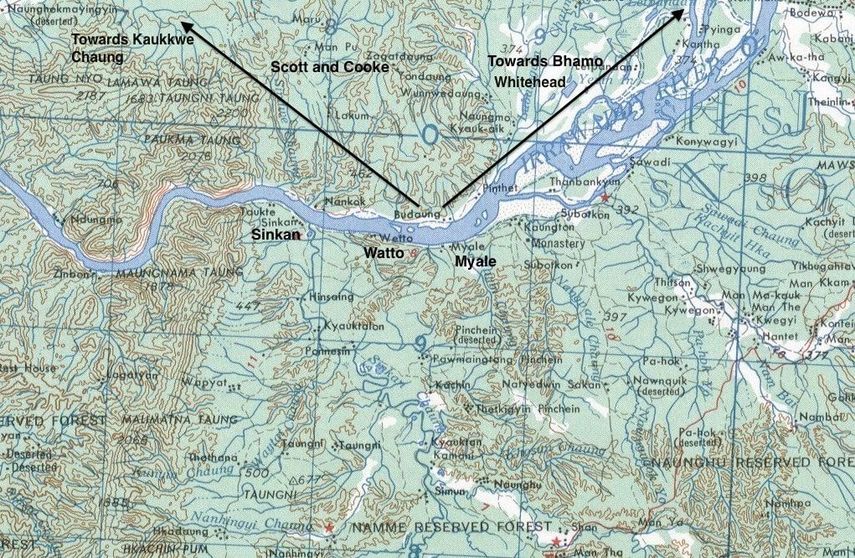

Shown below is a map of 8 Column's dispersal at the Irrawaddy in April 1943.

On the 3rd April, 8 Column were waiting to cross the treacherously fast flowing Shweli River. Two days previously, on their first attempt to cross the river, Captain Williams and his platoon had succeeded in getting over. This group had then become separated after the next section of men accidentally lost control of the boats used and were washed away downstream. After coming to terms with this latest disaster, Major Scott called up the RAF to drop more dinghies to the column and these duly arrived the next day. The diary recorded:

Signal sent to Corps (2nd April) asking for two RAF dinghies and two Recce boats to be dropped to us. The building of rafts continued and orders were issued for a crossing to be carried out at all costs if no supply drop of boats could be made. At 18.00 hours the boats and 200 lifebelts and two days rations per man were delivered. At dusk the crossing began and continued on until 09.00 hours the following day. All ranks and our two mules went over. Excellent work had been done by F/Lt. Wheatley and Lt. Gillow in swimming the river and preparing the far bank.

It was decided to split the column into three dispersal groups after crossing the Shweli, this was to ensure that if the Chindits met with any enemy interference on the opposite bank, or on their return journey to India, they would not all be in one place and easily engaged or captured.

A few days later, the three groups re-formed at a pre-arranged rendezvous and began their approach towards the Irrawaddy, close to where the river meanders near the village of Myale.

On 12th April, the front of the column was approaching a newly built bamboo bridge over a chaung when they bumped into a couple of Japanese who turned and bolted back into the jungle. Intense firing broke out and Sergeant Bridgeman and Private Beard were killed, while Privates Lawton and Witheridge were both seriously wounded. Most of the column turned around and disappeared along the track they had come down, leaving Major Scott and a small party of men isolated for a short time. It was not until the evening that the column reassembled and it was discovered that Lieutenant Horncastle and 14 others were missing. It was thought that they might have subsequently moved off as a separate party.

The column was up and moving at 0430 hours the next morning. The going was quite good but they now had three wounded on stretchers to carry with them. Major Scott and Lieutenant Colonel Cooke held an officers' conference and it was decided that they would request one last supply drop (presumably organised by Flight Lieutenant Wheatley) before breaking up into dispersal groups to cross the Irrawaddy. The dispersal groups were arranged as follows:

Lieutenant Colonel Cooke, Lieutenant Borrow and half of Group Headquarters;

Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and the other half of Group Headquarters;

Major Scott with Column Headquarters, 17 Platoon and two sections of 16 Platoon;

Captain Whitehead and his Burma Rifles less those already allocated to assist the other dispersal groups, plus Flying Officer Wheatley and a section of 16 Platoon;

Lieutenants Carroll, Hamilton-Bryan with Support Group and 19 Platoon;

Lieutenants Neill and Sprague with the Gurkha Platoon and 142 Commando Platoon.

On 15th April, Captain Whitehead and his dispersal group, together with the stretcher party under Sergeant Parsons and the Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote, left the column. They planned to move to the east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkyina to Fort Hertz. If this plan failed they would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then go west towards the Chindwin.

Captain Whitehead's group, including Ken Wheatley, was considerably larger than most, being made up of around 60-70 men. The reason for this was that he had agreed to take with him a number of sick and wounded men from No. 16 Platoon, many of these soldiers needed to be carried on stretchers and had been battle casualties at the village of Baw on the 23rd March. Whitehead's intention was to find a friendly Kachin village in which to leave these men and then take the rest of his party back to India. After several days of searching no suitable village was found, in fact many of the villages listed on the Captain's map no longer seemed to exist.

Shown below is a map of 8 Column's dispersal at the Irrawaddy in April 1943.

Senior officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke's entry for the 15th April 1943 in 8 Column's War diary, describes the intentions of Captain Whitehead and his aspirations for the sick and wounded men under his command:

Column failed to make contact with Corps, battery very weak, decided to give it a rest for 24 hours and then send an abbreviated signal tomorrow.

Captain Whitehead with his dispersal group, the stretcher party carrying a wounded Burrif, Pte. Lawton and Pte. Witherridge, the Medical Officer and an escort party under Captain Hamilton-Bryan left the column at 1530 hours. Captain Whitehead's intention was to return to British held territory, going east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkhina and Fort Hertz. Failing this he would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then head west to the Chindwin.

The wounded are to be dropped off at a friendly Kachin village, where they would be given 75 rupees in silver, their rifle and ammunition, plus a compass. Whitehead asked for two supply drops to be arranged along his proposed route; that is if wireless communication can be re-opened with Corps. At 0500 hours on the 16th April, a short message was sent to Corps. A runner then came back from Whitehead's party reporting their difficulty in moving down the eastern slopes of the mountains and that the first villages visited were deserted.

From reading about and researching the men of Operation Longcloth, I can confirm that Sergeant Tony Aubrey, Pte. Dennis Brown and a Burma Rifles officer, Jemadar Ah Di were all part of the dispersal group led by Captain Whitehead. Aubrey and Brown were seconded to the group by Lt. Hamilton-Bryan and acted as stretcher-bearers for the wounded. Both these men returned to the main body of 8 Column around 24 hours after leaving the wounded Chindits with the Headman of a local Kachin village.

Sgt. Aubrey remembered those difficult few days after dispersal in his book, With Wingate in Burma, written with the assistance of co-author David Halley:

The hardness of the road, and the scarcity of villages on the way, made it seem likely that small bodies would have a better chance than large ones of winning through. So it was decided that we should split up into the dispersal groups previously decided upon. The officer commanding each group would choose his own route and employ his own methods. Another decision was also arrived at now, and this the hardest that anyone could be called upon to make.

We had carried with us since the action of the previous day three wounded men whose hurts were so serious that they could not walk. Two of these were British and one Burmese. We had no proper stretchers to carry them on, and had improvised litters for them out of bamboo. The jungle which now lay before us was to all intents and purposes virgin. To make our way through it unburdened would be a task of the utmost difficulty. To carry litters through it would be a virtual impossibility.

The discomfort to which the wounded men themselves would be put on such a journey would be horrible, and would in all probability aggravate their injuries to a fatal extent. Both they themselves and the remainder of the column would stand a better chance of survival if they were left behind. The situation was put to them, and they at once agreed, like the men they were. There was a village twelve miles away, and here we decided to leave them, in the hands of the Burmese, who had always shown themselves friendly towards us, and who would look after them to the best of their ability.

Some of the Group Commanders decided that their best course would be to stay where they were, on top of the hill, till nightfall, and march under cover of darkness. But Captain Whitehead of the Burma Rifles, made up his mind to start at once. So the wounded would be sent, under the protection of his group, to the village.

Volunteers were called for to make a carrying party. Thirty men were chosen, under Mr. Hamilton Bryan, with myself as his sergeant. Major Scott said that he would wait for our return until dark before leaving; all the cigarettes available were collected and given to the wounded, farewells were said, and we started. That march was a nightmare.

Captain Whitehead was in a hurry, and so were we. We had no intention of failing to return to Major Scott, and what seemed comparative safety, before the time laid down by him. Yet every step in this jungle, the thickest I have ever seen, had to be won, and our dhas were in constant use. The pain the wounded must have suffered beggars description, but not one of them uttered a sound of complaint.

It had been still early morning when we started, and it is a tribute to our strength, and our anxiety, that we reached the village which was our destination shortly after twelve midday. But reaching it did us no good. It had been a village once, but now it was only a collection of burnt patches on the ground. There was no sign of life, not a Burmese, not a domestic animal, not even a Jap was to be seen. It was complete desolation.

Captain Whitehead, who knew these parts pretty well, having been, I think, a Resident Magistrate, said that there should be another village six miles farther on. Probably, it too, would be in this same condition, but it was worth investigating. While the remainder of us rested and cooked a meal, two Burma Riflemen were sent on to reconnoitre. They were back in an incredibly short space of time, with the news that this village had not been molested in any way, that the villagers were carrying on as usual, and that there was no trace of Japs in the neighbourhood.

If the carrying party went on as far as this second village, it meant that they would have to cover another twelve miles, six carrying the litters, and six unburdened. That, in its turn, meant that they would almost certainly fail to contact Major Scott back at the rendezvous. So Captain Whitehead's party took on the carrying duties, and we were allowed to make our way back. I prefer not to think of saying goodbye to the wounded. Two of them I knew very well, and one had even travelled out from England in the same ship with me. This was war with a vengeance. The weak, as always, must suffer. If we had travelled fast coming, we tried to travel at twice the speed going back.

Column failed to make contact with Corps, battery very weak, decided to give it a rest for 24 hours and then send an abbreviated signal tomorrow.

Captain Whitehead with his dispersal group, the stretcher party carrying a wounded Burrif, Pte. Lawton and Pte. Witherridge, the Medical Officer and an escort party under Captain Hamilton-Bryan left the column at 1530 hours. Captain Whitehead's intention was to return to British held territory, going east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkhina and Fort Hertz. Failing this he would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then head west to the Chindwin.

The wounded are to be dropped off at a friendly Kachin village, where they would be given 75 rupees in silver, their rifle and ammunition, plus a compass. Whitehead asked for two supply drops to be arranged along his proposed route; that is if wireless communication can be re-opened with Corps. At 0500 hours on the 16th April, a short message was sent to Corps. A runner then came back from Whitehead's party reporting their difficulty in moving down the eastern slopes of the mountains and that the first villages visited were deserted.

From reading about and researching the men of Operation Longcloth, I can confirm that Sergeant Tony Aubrey, Pte. Dennis Brown and a Burma Rifles officer, Jemadar Ah Di were all part of the dispersal group led by Captain Whitehead. Aubrey and Brown were seconded to the group by Lt. Hamilton-Bryan and acted as stretcher-bearers for the wounded. Both these men returned to the main body of 8 Column around 24 hours after leaving the wounded Chindits with the Headman of a local Kachin village.

Sgt. Aubrey remembered those difficult few days after dispersal in his book, With Wingate in Burma, written with the assistance of co-author David Halley:

The hardness of the road, and the scarcity of villages on the way, made it seem likely that small bodies would have a better chance than large ones of winning through. So it was decided that we should split up into the dispersal groups previously decided upon. The officer commanding each group would choose his own route and employ his own methods. Another decision was also arrived at now, and this the hardest that anyone could be called upon to make.

We had carried with us since the action of the previous day three wounded men whose hurts were so serious that they could not walk. Two of these were British and one Burmese. We had no proper stretchers to carry them on, and had improvised litters for them out of bamboo. The jungle which now lay before us was to all intents and purposes virgin. To make our way through it unburdened would be a task of the utmost difficulty. To carry litters through it would be a virtual impossibility.

The discomfort to which the wounded men themselves would be put on such a journey would be horrible, and would in all probability aggravate their injuries to a fatal extent. Both they themselves and the remainder of the column would stand a better chance of survival if they were left behind. The situation was put to them, and they at once agreed, like the men they were. There was a village twelve miles away, and here we decided to leave them, in the hands of the Burmese, who had always shown themselves friendly towards us, and who would look after them to the best of their ability.

Some of the Group Commanders decided that their best course would be to stay where they were, on top of the hill, till nightfall, and march under cover of darkness. But Captain Whitehead of the Burma Rifles, made up his mind to start at once. So the wounded would be sent, under the protection of his group, to the village.

Volunteers were called for to make a carrying party. Thirty men were chosen, under Mr. Hamilton Bryan, with myself as his sergeant. Major Scott said that he would wait for our return until dark before leaving; all the cigarettes available were collected and given to the wounded, farewells were said, and we started. That march was a nightmare.

Captain Whitehead was in a hurry, and so were we. We had no intention of failing to return to Major Scott, and what seemed comparative safety, before the time laid down by him. Yet every step in this jungle, the thickest I have ever seen, had to be won, and our dhas were in constant use. The pain the wounded must have suffered beggars description, but not one of them uttered a sound of complaint.

It had been still early morning when we started, and it is a tribute to our strength, and our anxiety, that we reached the village which was our destination shortly after twelve midday. But reaching it did us no good. It had been a village once, but now it was only a collection of burnt patches on the ground. There was no sign of life, not a Burmese, not a domestic animal, not even a Jap was to be seen. It was complete desolation.

Captain Whitehead, who knew these parts pretty well, having been, I think, a Resident Magistrate, said that there should be another village six miles farther on. Probably, it too, would be in this same condition, but it was worth investigating. While the remainder of us rested and cooked a meal, two Burma Riflemen were sent on to reconnoitre. They were back in an incredibly short space of time, with the news that this village had not been molested in any way, that the villagers were carrying on as usual, and that there was no trace of Japs in the neighbourhood.

If the carrying party went on as far as this second village, it meant that they would have to cover another twelve miles, six carrying the litters, and six unburdened. That, in its turn, meant that they would almost certainly fail to contact Major Scott back at the rendezvous. So Captain Whitehead's party took on the carrying duties, and we were allowed to make our way back. I prefer not to think of saying goodbye to the wounded. Two of them I knew very well, and one had even travelled out from England in the same ship with me. This was war with a vengeance. The weak, as always, must suffer. If we had travelled fast coming, we tried to travel at twice the speed going back.

The only clue we have, as to what happened to Captain Whitehead, Flight Lieutenant Wheatley, Medical Officer J.D.S. Heathcote, Captain Hamilton-Bryan and the rest of the original dispersal group, comes from a testimony by Lt. J. H. Stuart-Jones of the Gurkha Rifles. In a letter written shortly after the war, Lt. Stuart-Jones, known to his colleagues as 'Jock' described the following:

About eight days after we crossed the Shweli River, it was decided we should split up into dispersal groups of about 60 men under 1 or 2 officers and choosing our own route, make our way back to India. My party formed part of the group under Captain Whitehead of the Burma Rifles.

I had inherited six British Other Ranks after the incident at Baw village. These were added to my original four B.O.R.'s and the 12 Gurkha muleteers already under my command. Our group then volunteered to take with them the wounded men from the Column and to put these into a friendly village near or in Kachin country. With these wounded were a number of stretcher bearers and all of these were from 16 Platoon.

The dispersal group moved away from the Irrawaddy and two days later we managed to place the wounded in a native Kachin/Shan village; whether they were looked after properly, I don't to know.

The following day our group was ambushed by a mixed force of Burmese and Japanese. Our rendezvous in case of attack, was a half-mile due North of our position. I made the R.V. in the company of two Burma Riflemen and a V.C.O. (Jemadar Ah Di) and waited there all night. We often heard firing from the direction of a village about a mile away.

We marched on for three days, passing between enemy held villages along the Sinlumkaba Tract. We had no food, but dare not enter any of these villages as we crossed over the Bhamo-Mandalay motor road. One evening we came across a village and entered cautiously to enquire about some food. We found the remainder of our dispersal party already there, less Captain Whitehead and Flight-Lieutenant Wheatley who had been lost at the ambush and the Medical Orderly who had been handed over to the Japanese by the Shans.

From an undated report by 8 Column Commander, Major W.P. Scott:

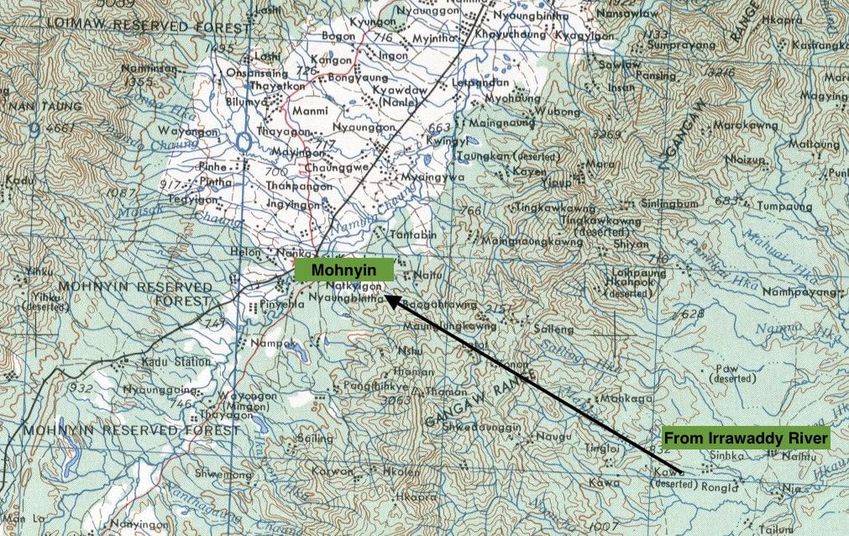

It has been reported to me that F/L Wheatley was taken prisoner soon after the 15th April 1943, but subsequently escaped. He was later recaptured on or around the 27th April in the mountains west of Mohnyin close to the railway. He was later taken into Mohnyin village with his hands bound.

In mid-May, Ken was confirmed as being held, alongside some 200 other Chindits at the Maymyo concentration camp. Eventually, all the surviving Chindit POWs travelled down to Rangoon Jail by rail aboard over-crowded cattle trucks.

About eight days after we crossed the Shweli River, it was decided we should split up into dispersal groups of about 60 men under 1 or 2 officers and choosing our own route, make our way back to India. My party formed part of the group under Captain Whitehead of the Burma Rifles.

I had inherited six British Other Ranks after the incident at Baw village. These were added to my original four B.O.R.'s and the 12 Gurkha muleteers already under my command. Our group then volunteered to take with them the wounded men from the Column and to put these into a friendly village near or in Kachin country. With these wounded were a number of stretcher bearers and all of these were from 16 Platoon.

The dispersal group moved away from the Irrawaddy and two days later we managed to place the wounded in a native Kachin/Shan village; whether they were looked after properly, I don't to know.

The following day our group was ambushed by a mixed force of Burmese and Japanese. Our rendezvous in case of attack, was a half-mile due North of our position. I made the R.V. in the company of two Burma Riflemen and a V.C.O. (Jemadar Ah Di) and waited there all night. We often heard firing from the direction of a village about a mile away.

We marched on for three days, passing between enemy held villages along the Sinlumkaba Tract. We had no food, but dare not enter any of these villages as we crossed over the Bhamo-Mandalay motor road. One evening we came across a village and entered cautiously to enquire about some food. We found the remainder of our dispersal party already there, less Captain Whitehead and Flight-Lieutenant Wheatley who had been lost at the ambush and the Medical Orderly who had been handed over to the Japanese by the Shans.

From an undated report by 8 Column Commander, Major W.P. Scott:

It has been reported to me that F/L Wheatley was taken prisoner soon after the 15th April 1943, but subsequently escaped. He was later recaptured on or around the 27th April in the mountains west of Mohnyin close to the railway. He was later taken into Mohnyin village with his hands bound.

In mid-May, Ken was confirmed as being held, alongside some 200 other Chindits at the Maymyo concentration camp. Eventually, all the surviving Chindit POWs travelled down to Rangoon Jail by rail aboard over-crowded cattle trucks.

Ken and the rest of the Chindits were held inside Block 6 at Rangoon Jail. Many men were suffering badly from the effects of operating behind enemy lines over the past 12 weeks and their short time as prisoners of war. The Japanese did nothing to improve matters, either by feeding the malnourished Chindits, or providing the medicines they so badly required. As a result, men began to perish inside Block 6 at an alarming rate during June/July 1943. It is recorded that Ken Wheatley did his very best to assist in the care of these dying men and in particular one seriously ill Chindit officer.

From the personal memoir of Lt. R.A. Wilding, the Cipher Officer from Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters in 1943 and a fellow inmate of Rangoon Jail:

One of the Chindit officers had a jungle sore which became gangrenous. The smell was so bad that, at his own request, he was moved out of the 'hospital' for the sake of the other sick. I liked him very much but found that a half hour visit was all I could manage. A friend of his, a Canadian Flight Lieutenant named Wheatley, used to sit with him for hours, although on at least one occasion he was physically sick when he finally left. When the patient died, Ken was there to hold his hand. What more can you do for a friend.

Without being in a position to be certain, I believe that the officer in question was Lt. Brian Pape Horncastle, who served with 8 Column on Operation Longcloth and who I know died from infected jungle sores.

Ken was himself seriously ill on several occasions during his time in Japanese hands. Whilst in Rangoon Jail he suffered from, dysentery, jaundice, gastroenteritis and general malnutrition. After the war he received treatment at a hospital in Calgary for hookworm. Ken spent exactly two years as a prisoner of war, before being liberated on the 29th April 1945 at a village called Waw on the Pegu Road.

Fellow Chindit POW, Lt. Alec Gibson describes the lead up to that time:

Eventually in April 1945 the Japs decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 of us were classified as fit to march and on the 24th of April we marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and crippled. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, we were north of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge when we ran into the 14th Army. The Jap Commandant left us in a village told us we were free and disappeared with the rest of his guards. We were in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. Thankfully, that night we managed to contact our own troops, the West Yorkshire's, and were liberated.

News of Flight Lieutenant Wheatley's liberation was soon announced back home in Canada. From a newspaper article, source unknown, comes the following report:

Calcutta, May 16th 1945. Seven Canadian Airmen and one Canadian Army officer are now in India after their release from a Rangoon prison following the capture of Burma's capital. The liberated men told stories of face-slapping by their Japanese guards, beatings during questioning and the ruthless clubbing of one man's injured legs. Two of the men, Kenneth Wheatley and Flight Lieutenant Malfred Haakenson, were flown back to India to a rest centre after a hospital examination.

The other liberated men arrived at Calcutta via hospital ship. They were: Flight Lieutenant Herbert Ivens, Flight Officer Keith Cuddy, Pilot Officer John Yanota, Pilot Officer Richard Corbett and Warrant Officer Ralph Stephens. The name of one other prisoner was withheld pending notification of the next-of-kin. Not strong enough to march with the prisoners removed by the Japanese from the jail, the last five men were left at Rangoon to await the arrival of Allied troops. It was they who painted a whitewash sign on the jail roof telling Allied Airmen that the enemy had gone.

Flight Lieutenant Ivens was shot down last December (1944) and his legs were injured. They were bandaged by his captors at first, but when he reached the prison the bandages were removed and from then on he received no medical attention and could not walk for two months. He was interrogated frequently during this period and when he refused to answer his questioners, they struck his swollen legs with clubs. They did not get anything out of Ivens, because every time they hit him he passed out.

Similar stories of beatings were told by Flight Lieutenant Haakenson, who said: They were not at all gentle. According to the rules the only information a prisoner is required to give is his name, rank and number, but this was not enough for them. They had a man standing behind me with a club and when the answers didn't suit them I'd get a beating. Ever since the American raid on Tokyo in December 1943, the Japanese have been tough on any fliers they captured. We are treated as ordinary criminals. The guards liked to act tough, always glaring and threatening. When a sentry passed the door of the cell I had to jump up and bow. That went against the grain I can tell you, but I soon learned that if I didn't make a bow I got a beating for it.

Ralph Stephens said life in prison was to a great extent determined by the individual guards. He was not beaten when he refused to answer questions, but the Japanese instead tried starvation tactics on him during his first three days of imprisonment. Pilot Officer Richard Corbett said that the disease beri beri was prevalent in the prison, since rice was virtually all the men had to eat and only occasionally were vegetables provided.

From the personal memoir of Lt. R.A. Wilding, the Cipher Officer from Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters in 1943 and a fellow inmate of Rangoon Jail:

One of the Chindit officers had a jungle sore which became gangrenous. The smell was so bad that, at his own request, he was moved out of the 'hospital' for the sake of the other sick. I liked him very much but found that a half hour visit was all I could manage. A friend of his, a Canadian Flight Lieutenant named Wheatley, used to sit with him for hours, although on at least one occasion he was physically sick when he finally left. When the patient died, Ken was there to hold his hand. What more can you do for a friend.

Without being in a position to be certain, I believe that the officer in question was Lt. Brian Pape Horncastle, who served with 8 Column on Operation Longcloth and who I know died from infected jungle sores.

Ken was himself seriously ill on several occasions during his time in Japanese hands. Whilst in Rangoon Jail he suffered from, dysentery, jaundice, gastroenteritis and general malnutrition. After the war he received treatment at a hospital in Calgary for hookworm. Ken spent exactly two years as a prisoner of war, before being liberated on the 29th April 1945 at a village called Waw on the Pegu Road.

Fellow Chindit POW, Lt. Alec Gibson describes the lead up to that time:

Eventually in April 1945 the Japs decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 of us were classified as fit to march and on the 24th of April we marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and crippled. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, we were north of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge when we ran into the 14th Army. The Jap Commandant left us in a village told us we were free and disappeared with the rest of his guards. We were in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. Thankfully, that night we managed to contact our own troops, the West Yorkshire's, and were liberated.

News of Flight Lieutenant Wheatley's liberation was soon announced back home in Canada. From a newspaper article, source unknown, comes the following report:

Calcutta, May 16th 1945. Seven Canadian Airmen and one Canadian Army officer are now in India after their release from a Rangoon prison following the capture of Burma's capital. The liberated men told stories of face-slapping by their Japanese guards, beatings during questioning and the ruthless clubbing of one man's injured legs. Two of the men, Kenneth Wheatley and Flight Lieutenant Malfred Haakenson, were flown back to India to a rest centre after a hospital examination.

The other liberated men arrived at Calcutta via hospital ship. They were: Flight Lieutenant Herbert Ivens, Flight Officer Keith Cuddy, Pilot Officer John Yanota, Pilot Officer Richard Corbett and Warrant Officer Ralph Stephens. The name of one other prisoner was withheld pending notification of the next-of-kin. Not strong enough to march with the prisoners removed by the Japanese from the jail, the last five men were left at Rangoon to await the arrival of Allied troops. It was they who painted a whitewash sign on the jail roof telling Allied Airmen that the enemy had gone.

Flight Lieutenant Ivens was shot down last December (1944) and his legs were injured. They were bandaged by his captors at first, but when he reached the prison the bandages were removed and from then on he received no medical attention and could not walk for two months. He was interrogated frequently during this period and when he refused to answer his questioners, they struck his swollen legs with clubs. They did not get anything out of Ivens, because every time they hit him he passed out.

Similar stories of beatings were told by Flight Lieutenant Haakenson, who said: They were not at all gentle. According to the rules the only information a prisoner is required to give is his name, rank and number, but this was not enough for them. They had a man standing behind me with a club and when the answers didn't suit them I'd get a beating. Ever since the American raid on Tokyo in December 1943, the Japanese have been tough on any fliers they captured. We are treated as ordinary criminals. The guards liked to act tough, always glaring and threatening. When a sentry passed the door of the cell I had to jump up and bow. That went against the grain I can tell you, but I soon learned that if I didn't make a bow I got a beating for it.

Ralph Stephens said life in prison was to a great extent determined by the individual guards. He was not beaten when he refused to answer questions, but the Japanese instead tried starvation tactics on him during his first three days of imprisonment. Pilot Officer Richard Corbett said that the disease beri beri was prevalent in the prison, since rice was virtually all the men had to eat and only occasionally were vegetables provided.

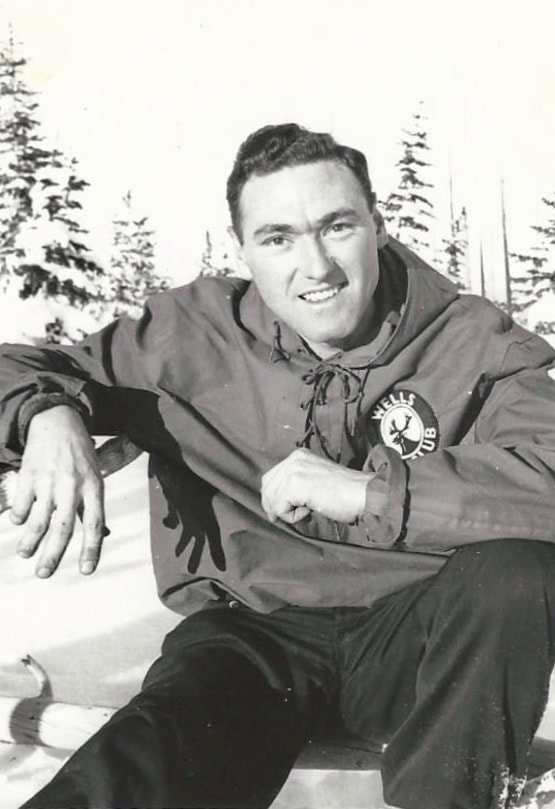

After his period of rest and recuperation in India, Ken Wheatley was repatriated by air to the United Kingdom on the 14th June 1945, returning to Canada three weeks later on the 8th July. He retired from the RCAF on the 12th December 1945, but returned to service with the RCAF Auxiliary (Fighter Control No. 2403 Squadron, Calgary) from October 1958 to May 1961. The photograph below, shows Ken Wheatley (left) talking to fellow POW, Flying Officer Joseph Callaghan after their liberation in April 1945 on the Pegu Road. Callaghan was a Beaufighter pilot from Camelon in Stirlingshire and had been kept in solitary confinement at Rangoon Jail for over three months.

Photograph from the on line collection of the Australian War Memorial website: reference code PO2491.068.

Photograph from the on line collection of the Australian War Memorial website: reference code PO2491.068.

In November 2011, I was pleased to receive the following email from Eveline Goodall, a relative of Ken Wheatley:

Dear Steve,

It is thrilling to have made this connection and to view your website. I am in the process of trying to ferret out Ken's war story and get it down on paper. Other than a few anecdotes, he did not to my knowledge speak of his war experiences. It very interesting to me how much has come to light in the last ten years on the internet. I have just ordered, through inter-library loans, a transcript from the Canadian Aviation Museum which should give me a lot of information on his pre-Chindit flying years. Somewhere in my research, I learned that he was the only Canadian on Operation Longcloth. Can you verify that for me please. I will be in touch with you further once I have assembled all of my data. Thank you for what you have done. It has been invaluable to me and a wonderful tribute to the memory of these men.

Sadly, I have been unable to make contact with Eveline since our initial communications during 2011. I sincerely hope that she will discover this narrative at some point in the near future. From information available on line, I understand that Ken Wheatley passed away on the 18th February 1989 in the Canadian province of British Columbia.

Update 20/07/2020.

I was delighted recently to receive the following email contact via the Chindit Society:

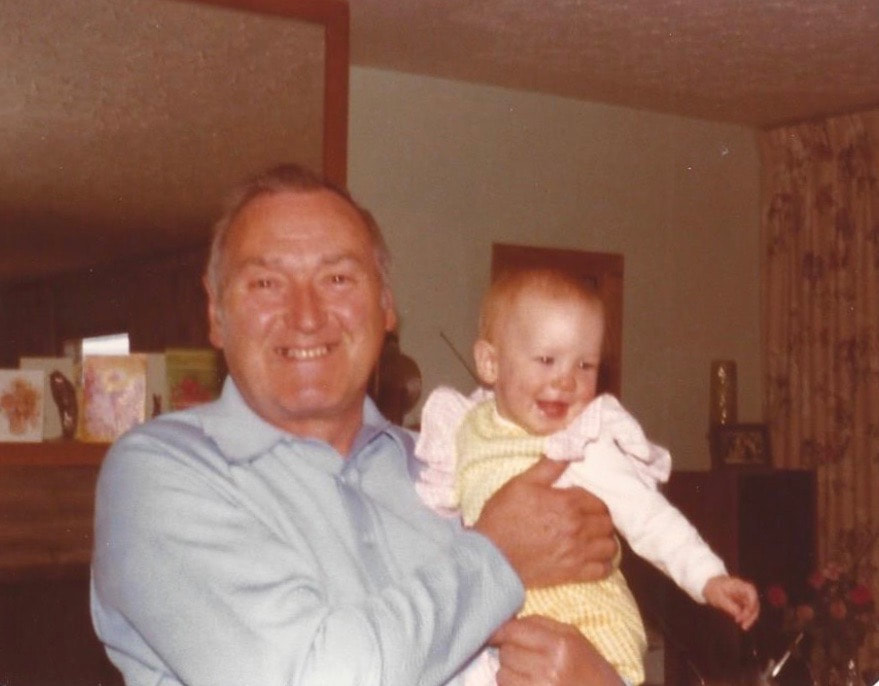

Stephen, I wanted to pass along my thanks to you for creating the webpage for my grandpa, Ken Wheatley. I found it by accident while searching online—my brother Derek and I were thrilled to read it and show our own children, Ken's great grandchildren the photos and information. I was surprised to see that my dad’s cousin Eveline, had made contact with you in 2011. My dad, Dennis Wheatley, has more photos, stories, and information that he would be happy to share. Thank you once again for researching my grandpa.

Best regards, Nicole Nielsen.

It was wonderful to hear from Nicole and her family and I hope to add the photographs and information mentioned by her to this webpage in the near future.

Dear Steve,

It is thrilling to have made this connection and to view your website. I am in the process of trying to ferret out Ken's war story and get it down on paper. Other than a few anecdotes, he did not to my knowledge speak of his war experiences. It very interesting to me how much has come to light in the last ten years on the internet. I have just ordered, through inter-library loans, a transcript from the Canadian Aviation Museum which should give me a lot of information on his pre-Chindit flying years. Somewhere in my research, I learned that he was the only Canadian on Operation Longcloth. Can you verify that for me please. I will be in touch with you further once I have assembled all of my data. Thank you for what you have done. It has been invaluable to me and a wonderful tribute to the memory of these men.

Sadly, I have been unable to make contact with Eveline since our initial communications during 2011. I sincerely hope that she will discover this narrative at some point in the near future. From information available on line, I understand that Ken Wheatley passed away on the 18th February 1989 in the Canadian province of British Columbia.

Update 20/07/2020.

I was delighted recently to receive the following email contact via the Chindit Society:

Stephen, I wanted to pass along my thanks to you for creating the webpage for my grandpa, Ken Wheatley. I found it by accident while searching online—my brother Derek and I were thrilled to read it and show our own children, Ken's great grandchildren the photos and information. I was surprised to see that my dad’s cousin Eveline, had made contact with you in 2011. My dad, Dennis Wheatley, has more photos, stories, and information that he would be happy to share. Thank you once again for researching my grandpa.

Best regards, Nicole Nielsen.

It was wonderful to hear from Nicole and her family and I hope to add the photographs and information mentioned by her to this webpage in the near future.

Kenneth Wheatley in RAF uniform.

Kenneth Wheatley in RAF uniform.

Update 20/09/2020.

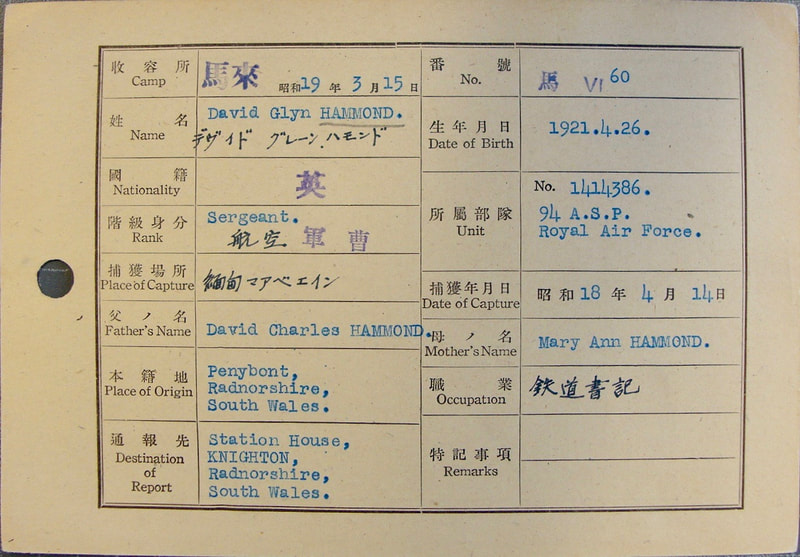

Kenneth Wheatley's son, Dennis did make contact with me and has provided me with some fantastic information and photographs in relation to his father and his war service and beyond. From my email conversations with Dennis, I now know that Kenneth Wheatley kept a form of diary whilst a prisoner in Rangoon Jail which began in August 1943. These pages contain important information about some of the other Chindit personnel held at the jail and what ultimately happened to them. Kenneth also kept in touch with one or two of his fellow inmates from Rangoon, including RAF Sergeant David Glyn Hammond from Penybont in South Wales, who was part of Wheatley's RAF Liaison team in No. 8 Column and was captured on the 14th April 1943.

Dennis also told me:

Steve, it is really great to communicate with you over the last few weeks. Dad was born in Bankhead, Alberta on the 21st September 1920. His father was in the coal mining business in Bankhead from 1908 until 1922 when the coal colliery closed. He then worked in Blairmore until 1929, when he moved to Banff and ran a family business in mining and delivering coal to local residents. Ken was baptised at Blairmore in April 1925 and confirmed at the Anglican Church at Banff in November 1934. Dad was very athletic and very much an outdoor person and excelled in all sports. He was a very good tennis player, a lifeguard and skier. He climbed, he canoed, he fished and hunted. He also seemed to have an aptitude for languages and I believe he received his Grade 12 (Educational) Diploma in 1939.

When he returned to Canada from the war he was quite infirm. He was diagnosed as having a tapeworm which caused him a lot of distress until it was removed. He moved to Wells, British Colombia to work for Island Mountain Mines, a gold mining company, where he managed their books. It was here he met his wife Gwendoline Einboden, who was a Registered Nurse. She was trained in surgery at the Toronto General Hospital and had worked as an operating room nurse at the Christie Street Military Hospital in Toronto.

I was born in December 1949, and after my grandfather's health declined we moved to Banff. Later on, Dad began working with the California (Chevron) Standard Oil Company in Calgary and in 1954 purchased 4 acres of land just outside of Calgary and began to build our family home.

During the Cold War period he was active in the RCAF reserve and on occasion travelled to the Cold Lake Radar installation to assist in radar monitoring exercises. He continued working with Chevron until he retired in 1980, when he sold up and moved to Westbank, which is located just outside of Kelowna in British Colombia. He continued to enjoy all of his outdoor pursuits right up until his sad passing in February 1989.

I am going to send you some more details about Dad's life and some photographs, which I hope will be of value to your research. You have done an amazing job in assembling all of this information about the Chindits. Well done. Regards Dennis.

War Service of Kenneth Wheatley

Kenneth joined the 2nd Brigade, Calgary Highlanders (a non-permanent Militia) on 15th August 1940. He then joined the RAF on 26th October 1940 and was sent to the Edmonton Flying School in January 1941 for his initial pilot training. He then undertook further service training at Yorkton, Saskatchewan from April until June 1941, flying Havards.

Ken left Canada on 4th August 1941, arriving in Belfast, Northern Ireland and then moving on to Stranraer in Scotland. He completed his training at Grangemouth in Stirlingshire as part of 124 Squadron, before being posted to 17 Squadron based at Catterick in Yorkshire. He left the United Kingdom by troopship on 8th December, arriving at Takoradi in West Africa on the 28th. From here he flew to Accra and then on to Lagos and Kano in Nigeria. After several other stops along the way, including Bahrain, Ken finally arrived at Karachi in India on the 26th January 1942.

He flew Hurricanes over India and Burma, often escorting Blenheim Bombers or intercepting Japanese fighters. In March 1942, after the Japanese invasion of Burma, he was based for a time at Chittagong, before moving to Loi-wing in China and flying long range Hurricanes against the enemy during the month of April. On 13th July 1942, Ken was promoted from Sergeant to Flight-Lieutenant, flying at this time out of Calcutta. In early 1943, Ken volunteered for the first Wingate expedition codenamed, Operation Longcloth. He was allocated as the RAF Air Liaison Officer for No. 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott.

Kenneth was captured by the Japanese in late April 1943, having spent some ten arduous weeks behind enemy lines. He would spend the next two years as a prisoner of war and was incarcerated for most of that time in Rangoon Central Jail. He was liberated in late April 1945, alongside 400 other POWs who had been marched out of the jail by their Japanese guards just a few days previously. After the war Ken returned to Canada and was discharged (with honour) from the RCAF on the 12th December 1945. For his service during WW2, he received the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal, the 1939-45 Star and the Burma Star medals and his cherished Pilot’s Flying Badge.

Kenneth Wheatley's son, Dennis did make contact with me and has provided me with some fantastic information and photographs in relation to his father and his war service and beyond. From my email conversations with Dennis, I now know that Kenneth Wheatley kept a form of diary whilst a prisoner in Rangoon Jail which began in August 1943. These pages contain important information about some of the other Chindit personnel held at the jail and what ultimately happened to them. Kenneth also kept in touch with one or two of his fellow inmates from Rangoon, including RAF Sergeant David Glyn Hammond from Penybont in South Wales, who was part of Wheatley's RAF Liaison team in No. 8 Column and was captured on the 14th April 1943.

Dennis also told me:

Steve, it is really great to communicate with you over the last few weeks. Dad was born in Bankhead, Alberta on the 21st September 1920. His father was in the coal mining business in Bankhead from 1908 until 1922 when the coal colliery closed. He then worked in Blairmore until 1929, when he moved to Banff and ran a family business in mining and delivering coal to local residents. Ken was baptised at Blairmore in April 1925 and confirmed at the Anglican Church at Banff in November 1934. Dad was very athletic and very much an outdoor person and excelled in all sports. He was a very good tennis player, a lifeguard and skier. He climbed, he canoed, he fished and hunted. He also seemed to have an aptitude for languages and I believe he received his Grade 12 (Educational) Diploma in 1939.

When he returned to Canada from the war he was quite infirm. He was diagnosed as having a tapeworm which caused him a lot of distress until it was removed. He moved to Wells, British Colombia to work for Island Mountain Mines, a gold mining company, where he managed their books. It was here he met his wife Gwendoline Einboden, who was a Registered Nurse. She was trained in surgery at the Toronto General Hospital and had worked as an operating room nurse at the Christie Street Military Hospital in Toronto.

I was born in December 1949, and after my grandfather's health declined we moved to Banff. Later on, Dad began working with the California (Chevron) Standard Oil Company in Calgary and in 1954 purchased 4 acres of land just outside of Calgary and began to build our family home.

During the Cold War period he was active in the RCAF reserve and on occasion travelled to the Cold Lake Radar installation to assist in radar monitoring exercises. He continued working with Chevron until he retired in 1980, when he sold up and moved to Westbank, which is located just outside of Kelowna in British Colombia. He continued to enjoy all of his outdoor pursuits right up until his sad passing in February 1989.

I am going to send you some more details about Dad's life and some photographs, which I hope will be of value to your research. You have done an amazing job in assembling all of this information about the Chindits. Well done. Regards Dennis.

War Service of Kenneth Wheatley

Kenneth joined the 2nd Brigade, Calgary Highlanders (a non-permanent Militia) on 15th August 1940. He then joined the RAF on 26th October 1940 and was sent to the Edmonton Flying School in January 1941 for his initial pilot training. He then undertook further service training at Yorkton, Saskatchewan from April until June 1941, flying Havards.

Ken left Canada on 4th August 1941, arriving in Belfast, Northern Ireland and then moving on to Stranraer in Scotland. He completed his training at Grangemouth in Stirlingshire as part of 124 Squadron, before being posted to 17 Squadron based at Catterick in Yorkshire. He left the United Kingdom by troopship on 8th December, arriving at Takoradi in West Africa on the 28th. From here he flew to Accra and then on to Lagos and Kano in Nigeria. After several other stops along the way, including Bahrain, Ken finally arrived at Karachi in India on the 26th January 1942.

He flew Hurricanes over India and Burma, often escorting Blenheim Bombers or intercepting Japanese fighters. In March 1942, after the Japanese invasion of Burma, he was based for a time at Chittagong, before moving to Loi-wing in China and flying long range Hurricanes against the enemy during the month of April. On 13th July 1942, Ken was promoted from Sergeant to Flight-Lieutenant, flying at this time out of Calcutta. In early 1943, Ken volunteered for the first Wingate expedition codenamed, Operation Longcloth. He was allocated as the RAF Air Liaison Officer for No. 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott.

Kenneth was captured by the Japanese in late April 1943, having spent some ten arduous weeks behind enemy lines. He would spend the next two years as a prisoner of war and was incarcerated for most of that time in Rangoon Central Jail. He was liberated in late April 1945, alongside 400 other POWs who had been marched out of the jail by their Japanese guards just a few days previously. After the war Ken returned to Canada and was discharged (with honour) from the RCAF on the 12th December 1945. For his service during WW2, he received the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal, the 1939-45 Star and the Burma Star medals and his cherished Pilot’s Flying Badge.

A Eulogy for Kenneth Wheatley

as written by his good friend and work colleague, Al Kane.

Ken was born in Banff on the 21st September 1920 and grew up among the mountains and streams, where he skied and fished long before the large number of tourists ever arrived. He knew the backwoods of Banff as we know our own back yards. He knew all the wardens and Rangers and was allowed into areas that were out of bounds to others. He was given these privileges because even as a young man people recognised his trustworthiness. I had the privilege in later years to be guided by Ken to fish in some of the streams he loved so much from his youth. I also had the privilege of knowing Ken’s parents, and can understand where Ken acquired his love of roast beef and Yorkshire pudding.

Ken graduated from High School in Banff and shortly afterwards joined the RCAF. He passed out as a Pilot then went overseas to Britain where he flew Hurricanes. His tour of duty took in places such as Africa, China, India and many other parts of the world. His reliability and trustworthiness became obvious to his military superiors and he would often fly wingman to his commanding officer on missions. He was always very modest about his escapades during his service, but as some of us know, they were what books are written about.

Where General Chenault of the Flying Tigers in China is a legendary individual to most of us, Ken would casually talk about having lunch with him in China. His experiences fighting the Japanese behind the lines is something even today, many of us have difficulty in visualising. How many times have I asked Ken: “Why did you volunteer for that kind of service and leave comfortable lodgings and good food?”

His answer was always the same: “You know AL, I thought I could help win the war.” A simple straightforward answer and so typical of Ken. You have to think back to Ken’s boyhood days growing up in Banff, to understand one particular episode while he was with Wingate’s Brigade in Burma. An elephant carrying ammunition across a river in Burma had its pack slip which turned the elephant over. It began to float downriver to where the Japanese were camped. Ken, realising that his column could be exposed if the Japanese saw the inverted elephant, stripped off his clothes, dived into the water and cut the strap holding the ammunition pack. He said to me: “I wonder if that elephant knows that I did him a favour?”

Ken was captured by the Japanese after throwing a grenade at a passing patrol when he ran into a bamboo thicket. He never did understand why he was not killed as soon as he was captured. While in the Japanese Camp (Rangoon Jail) he and his fellow prisoners suffered unbelievable hardships. It was only due to Ken’s strength of mind and body that he manged to survive. He would say a final farewell to those who died in the camp and removed their I.D. tags, so that he could correspond with their families after the war. He was held in the camp for two years before being released. A measure of the man was that he never showed any animosity towards the Japanese subsequent to his release. But, this is not to say that he did not have some strong opinions about our own government and their recent treatment of some Japanese citizens.

After a period of recuperation back home, Ken went to work for a mining company in Wells, BC. It was here that Ken met a pretty young nurse named Gwen. Ken was not the only handsome young man in pursuit of Gwen’s hand, although from what I can gather, Gwen had already made up her mind. Once again in typical fashion Ken confronted the other suitors and informed them of the real situation and invited them, if they did not agree, to settle the matter out behind the barn.

Ken and Gwen were married in Wells and had one son called Dennis. They would have been married 40 years on March 7th this year (1989). Ken came to work for the then California Standard Oil Company in 1956 and this was when I first met him. We became good friends from that time and have remained so ever since.

I would like to relate one more story, just to further demonstrate the kind of guy he was. During our working days in Calgary, Ken and I went on many hunting trips together and I treasure the memories of those beautiful Fall days out in the country, walking along munching an apple and spinning a yarn or two. On this particular occasion he was unable to join me on the Saturday, so a mutual friend and I went in our trailer to hunt that day and Ken was to meet us on the Sunday evening and hunt on Monday. When Ken arrived that evening, we were just about to heat up our pork and beans. He had a large bag in one hand and his gun in the other. “Don’t open that can of beans.” He said, and opened the bag from which extracted three steaks. Just as we were about to devour the steaks he reached into his bag again and withdrew three crystal glasses and a bottle of expensive wine. He had a lot of class.

Ken and Gwen retired to Okanagan Valley in 1981. Eileen and I had already purchased a lot and attempted to talk them into buying a place on 6th Avenue in Peachland. In the end they opted for Westbank in West Kelowna and that was Peachland’s loss. However, a great deal of their social life centred around Peachland and in fact, it was almost as if they lived there in any case. Ken enjoyed golf and especially with all of us in the Snip Group. How we used to kid him about that little changed purse that we accused him of growing moths in.

God Bless Ken.

as written by his good friend and work colleague, Al Kane.

Ken was born in Banff on the 21st September 1920 and grew up among the mountains and streams, where he skied and fished long before the large number of tourists ever arrived. He knew the backwoods of Banff as we know our own back yards. He knew all the wardens and Rangers and was allowed into areas that were out of bounds to others. He was given these privileges because even as a young man people recognised his trustworthiness. I had the privilege in later years to be guided by Ken to fish in some of the streams he loved so much from his youth. I also had the privilege of knowing Ken’s parents, and can understand where Ken acquired his love of roast beef and Yorkshire pudding.

Ken graduated from High School in Banff and shortly afterwards joined the RCAF. He passed out as a Pilot then went overseas to Britain where he flew Hurricanes. His tour of duty took in places such as Africa, China, India and many other parts of the world. His reliability and trustworthiness became obvious to his military superiors and he would often fly wingman to his commanding officer on missions. He was always very modest about his escapades during his service, but as some of us know, they were what books are written about.

Where General Chenault of the Flying Tigers in China is a legendary individual to most of us, Ken would casually talk about having lunch with him in China. His experiences fighting the Japanese behind the lines is something even today, many of us have difficulty in visualising. How many times have I asked Ken: “Why did you volunteer for that kind of service and leave comfortable lodgings and good food?”

His answer was always the same: “You know AL, I thought I could help win the war.” A simple straightforward answer and so typical of Ken. You have to think back to Ken’s boyhood days growing up in Banff, to understand one particular episode while he was with Wingate’s Brigade in Burma. An elephant carrying ammunition across a river in Burma had its pack slip which turned the elephant over. It began to float downriver to where the Japanese were camped. Ken, realising that his column could be exposed if the Japanese saw the inverted elephant, stripped off his clothes, dived into the water and cut the strap holding the ammunition pack. He said to me: “I wonder if that elephant knows that I did him a favour?”

Ken was captured by the Japanese after throwing a grenade at a passing patrol when he ran into a bamboo thicket. He never did understand why he was not killed as soon as he was captured. While in the Japanese Camp (Rangoon Jail) he and his fellow prisoners suffered unbelievable hardships. It was only due to Ken’s strength of mind and body that he manged to survive. He would say a final farewell to those who died in the camp and removed their I.D. tags, so that he could correspond with their families after the war. He was held in the camp for two years before being released. A measure of the man was that he never showed any animosity towards the Japanese subsequent to his release. But, this is not to say that he did not have some strong opinions about our own government and their recent treatment of some Japanese citizens.

After a period of recuperation back home, Ken went to work for a mining company in Wells, BC. It was here that Ken met a pretty young nurse named Gwen. Ken was not the only handsome young man in pursuit of Gwen’s hand, although from what I can gather, Gwen had already made up her mind. Once again in typical fashion Ken confronted the other suitors and informed them of the real situation and invited them, if they did not agree, to settle the matter out behind the barn.

Ken and Gwen were married in Wells and had one son called Dennis. They would have been married 40 years on March 7th this year (1989). Ken came to work for the then California Standard Oil Company in 1956 and this was when I first met him. We became good friends from that time and have remained so ever since.

I would like to relate one more story, just to further demonstrate the kind of guy he was. During our working days in Calgary, Ken and I went on many hunting trips together and I treasure the memories of those beautiful Fall days out in the country, walking along munching an apple and spinning a yarn or two. On this particular occasion he was unable to join me on the Saturday, so a mutual friend and I went in our trailer to hunt that day and Ken was to meet us on the Sunday evening and hunt on Monday. When Ken arrived that evening, we were just about to heat up our pork and beans. He had a large bag in one hand and his gun in the other. “Don’t open that can of beans.” He said, and opened the bag from which extracted three steaks. Just as we were about to devour the steaks he reached into his bag again and withdrew three crystal glasses and a bottle of expensive wine. He had a lot of class.

Ken and Gwen retired to Okanagan Valley in 1981. Eileen and I had already purchased a lot and attempted to talk them into buying a place on 6th Avenue in Peachland. In the end they opted for Westbank in West Kelowna and that was Peachland’s loss. However, a great deal of their social life centred around Peachland and in fact, it was almost as if they lived there in any case. Ken enjoyed golf and especially with all of us in the Snip Group. How we used to kid him about that little changed purse that we accused him of growing moths in.

God Bless Ken.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this family update, including many photographs from Ken Wheatley's war service. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. I would like to thank Dennis Wheatley for all the wonderful information about his father and for allowing me to include this and the many photographs on these website pages. By coincidence my own family and I took a holiday last August (2019) in Canada and spent several days in Banff, Jasper and the beautiful countryside that Kenneth Wheatley so adored. After experiencing this wonderful country and its kind and courteous people first hand, I can honestly say I have a total understanding of why he loved his home so much.

Update 05/11/2021.

I was delighted to receive the following email contact from my very good friend and fellow WW2 researcher, Matt Poole:

Steve, I've been meaning to send you this stuff for a while. Then, today, the photo of Ken Wheatley and J.D. Callaghan after liberation near Pegu in Burma was posted on the RAF in Burma SEAC & India Facebook site run by Jagan Pillarisetti. I remembered that back in the late summer of 2018, I'd found Wheatley mentioned in the Banff (Alberta in Canada) newspaper, the Crag & Canyon, when I was searching for information on J.S. Bird, another Banff pilot who went missing in North Africa in 1942. So here you go, please use if you wish. Cheers now, Matt.

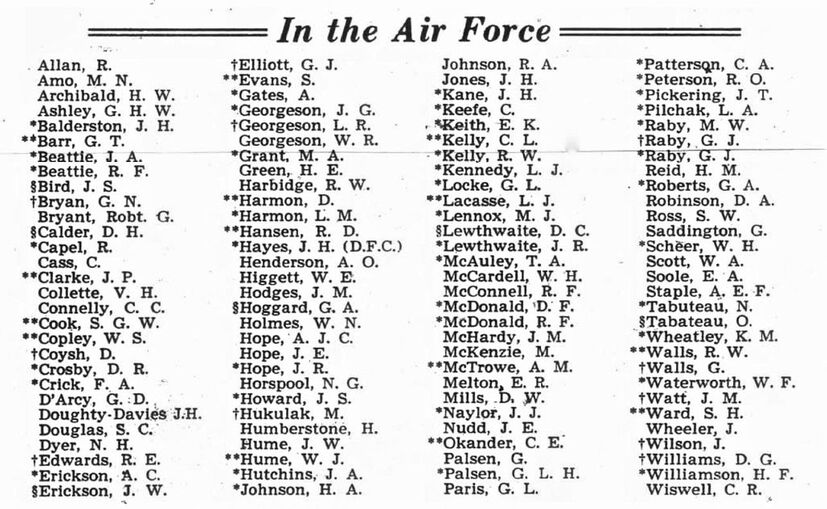

Matt sent over two articles from the Crag & Canyon newspaper and an image (shown below) of the Banff & District men who had fought in the Air Services during WW2.

The Crag and Canyon newspaper dated 13th March 1942:

Ski Runners of the Canadian Rockies Go To Sunshine.

A special Sunday trip to Sunshine has been planned for the Ski Runners of the Canadian Rockies on March 15th. Reservations should be made early with Mr. Sven Hansen or Miss Ethel Knight, so as to ensure accommodation. The bus will leave Banff at 8am, returning about 6pm.

In other news:

Two ex-Queens of the Banff Winter Carnivals and Dominion Ski Meet are trying very hard to earn their two-hundred-mile silver mileage button. Kay Betts of Spokane and Pinkie Marshall of Edmonton, after spending another ten days in the ski country around Banff, are now busy calculating the miles of ski touring and skiing in the Canadian Rockies.

Ski Runners of the Canadian Rockies will be found the world over. Pilot Officer John Bird is now winging his way over Egypt; Pilot Officer Norman Knight is the captain of a bomber aircraft in England, and Pilot Officer Ken Wheatley was reported looking at the sands around Cairo, thinking of trying out sand skiing.

The Crag and Canyon newspaper dated 14th September 1945:

Flight Lieutenant Ken Wheatley at the Rotary Club

On Monday September 10th, the Rotary Club was honoured in having as its guest speaker, Flight Lieutenant Ken Wheatley, a well known local man, who gave a resume of his experiences in the Middle and Far East during the war. Everybody knows Ken as a quiet unobtrusive chap, but when telling of his work with the RAF and of the conditions in the Japanese prison camp in Burma, he conveyed information in a clear and simple manner.

His address showed a fine discrimination of values whether talking about the pitifully inadequate supplies in the Far East in 1942, or the trying conditions in the prison camp in Rangoon; and most certainly he touched the peak of his sincerity when he paid a glowing tribute to the men who were with him, but did not manage to return.

As President Jim McLeod voiced the appreciation of the Club for this excellent address, the men displayed their feelings by a ringing round of applause. Thanks Ken!

I was delighted to receive the following email contact from my very good friend and fellow WW2 researcher, Matt Poole:

Steve, I've been meaning to send you this stuff for a while. Then, today, the photo of Ken Wheatley and J.D. Callaghan after liberation near Pegu in Burma was posted on the RAF in Burma SEAC & India Facebook site run by Jagan Pillarisetti. I remembered that back in the late summer of 2018, I'd found Wheatley mentioned in the Banff (Alberta in Canada) newspaper, the Crag & Canyon, when I was searching for information on J.S. Bird, another Banff pilot who went missing in North Africa in 1942. So here you go, please use if you wish. Cheers now, Matt.

Matt sent over two articles from the Crag & Canyon newspaper and an image (shown below) of the Banff & District men who had fought in the Air Services during WW2.

The Crag and Canyon newspaper dated 13th March 1942: