The Longcloth Roll Call

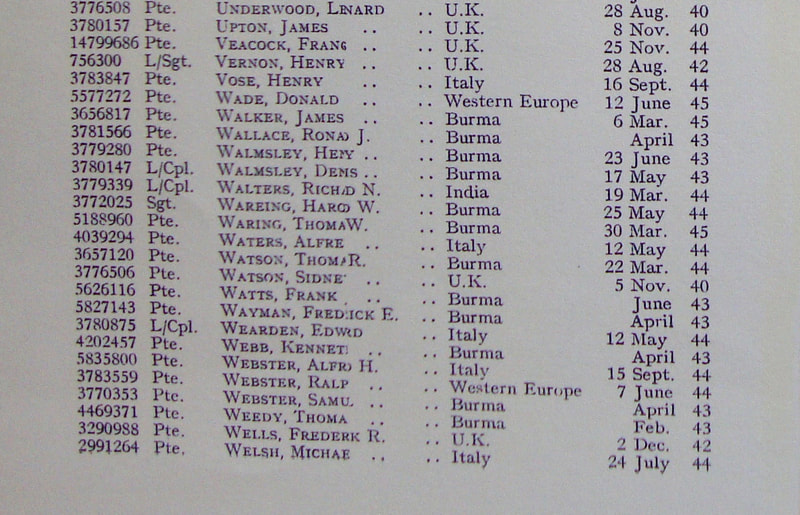

Surname U-Z

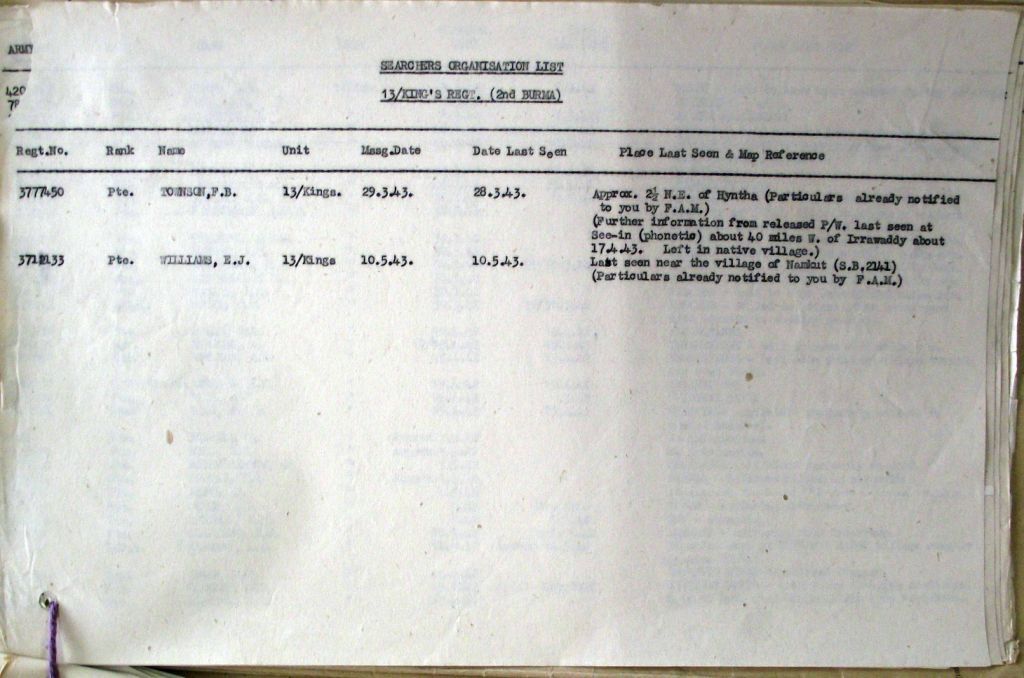

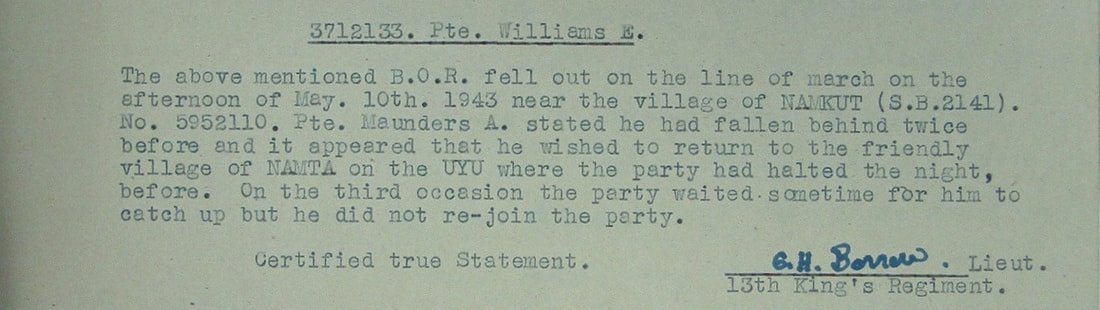

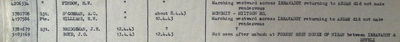

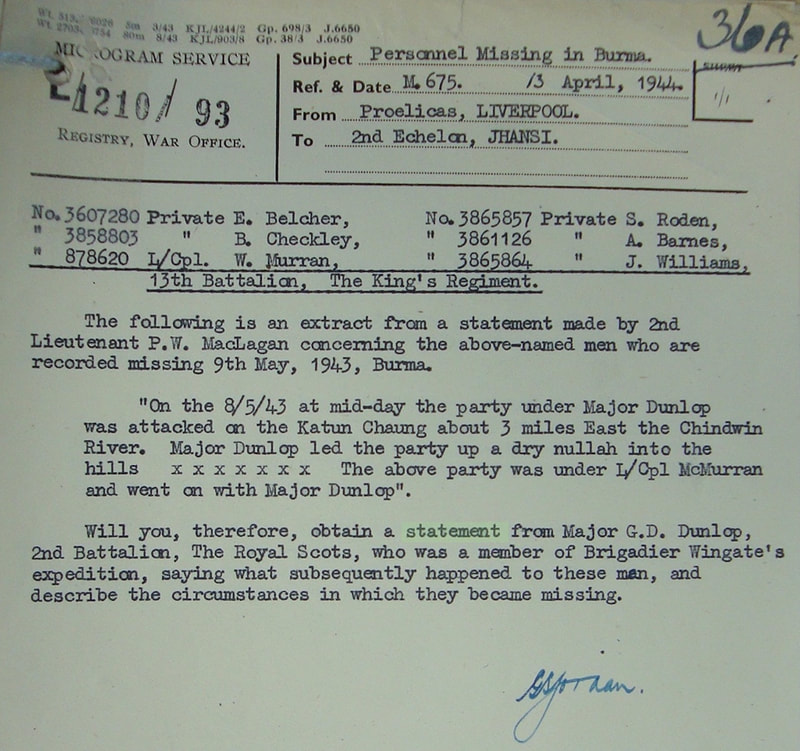

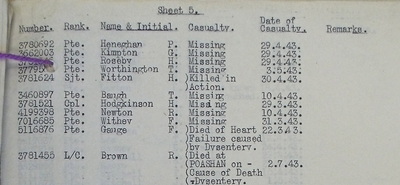

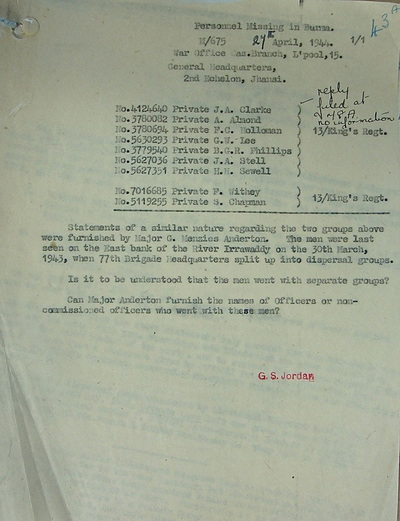

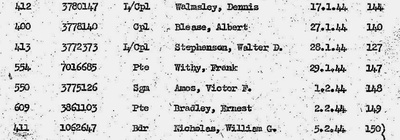

This section is an alphabetical roll of the men from Operation Longcloth. It takes its inspiration from other such formats available on the Internet, websites such as Special Forces Roll of Honour and of course the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). The information shown comes from various different documents related to the first Chindit Operation in 1943. Apart from more obvious data, such as the serviceman's rank, number and regimental unit, other detail has been taken from associated war diaries, missing in action files and casualty witness statements. The vast majority of this type of information has been located at the National Archives and the relevant file references can be found in the section Sources and Knowledge on this website.

Sometimes, if the man in question became a prisoner of war more detail can be displayed showing his time whilst in Japanese hands. Other avenues for additional information are: books, personal diaries, veteran audio accounts and subsequent family input via letter, email and phone call.

The idea behind this page, is to include as many Longcloth participants as possible, even if there is only a small amount of information about their contribution to hand. Please click on any of the images to hopefully bring them forward on the page.

All information contained on this page is Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.

This section is an alphabetical roll of the men from Operation Longcloth. It takes its inspiration from other such formats available on the Internet, websites such as Special Forces Roll of Honour and of course the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). The information shown comes from various different documents related to the first Chindit Operation in 1943. Apart from more obvious data, such as the serviceman's rank, number and regimental unit, other detail has been taken from associated war diaries, missing in action files and casualty witness statements. The vast majority of this type of information has been located at the National Archives and the relevant file references can be found in the section Sources and Knowledge on this website.

Sometimes, if the man in question became a prisoner of war more detail can be displayed showing his time whilst in Japanese hands. Other avenues for additional information are: books, personal diaries, veteran audio accounts and subsequent family input via letter, email and phone call.

The idea behind this page, is to include as many Longcloth participants as possible, even if there is only a small amount of information about their contribution to hand. Please click on any of the images to hopefully bring them forward on the page.

All information contained on this page is Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.

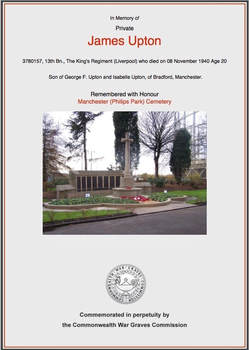

CWGC certificate for James Upton.

CWGC certificate for James Upton.

UPTON, JAMES

Rank: Private

Service No: 3780157

Date of Death: 08/11/1940

Age: 20

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Section O Grave 787 Manchester Philips Park Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2403167/upton,-james/#&gid=null&pid=2

Other details:

James Upton was the son of George and Isabelle Upton from Bradford in Manchester. Pte. Upton became the first recorded casualty of the 13th King's on the 8th November 1940, when he was accidentally shot with a revolver whilst the battalion were based at the Felixstowe Army Camp in Suffolk. After an investigation into the incident was concluded, James' body was released to the family and he was buried on the 13th November at the Philips Park Cemetery in Manchester alongside his mother and father. His grave inscription at Philips Park simply reads:

Rank: Private

Service No: 3780157

Date of Death: 08/11/1940

Age: 20

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Section O Grave 787 Manchester Philips Park Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2403167/upton,-james/#&gid=null&pid=2

Other details:

James Upton was the son of George and Isabelle Upton from Bradford in Manchester. Pte. Upton became the first recorded casualty of the 13th King's on the 8th November 1940, when he was accidentally shot with a revolver whilst the battalion were based at the Felixstowe Army Camp in Suffolk. After an investigation into the incident was concluded, James' body was released to the family and he was buried on the 13th November at the Philips Park Cemetery in Manchester alongside his mother and father. His grave inscription at Philips Park simply reads:

He Lies At Rest With Those He Loved Best,

His Mother and Father.

His Mother and Father.

Seen below are two images in relation to this short story. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page. NB: The above soldier should not be confused with Pte. 3650365 James Upton, who was a member of No. 8 Column on Operation Longcloth and was involved in the hijacking of a Burmese boat on the Irrawaddy in late April 1943.

Cap badge for the Royal Welch Fusiliers.

Cap badge for the Royal Welch Fusiliers.

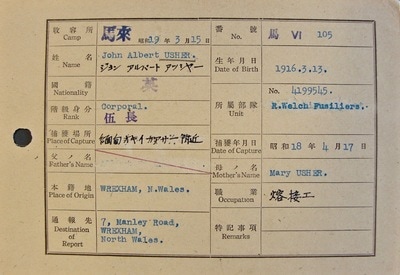

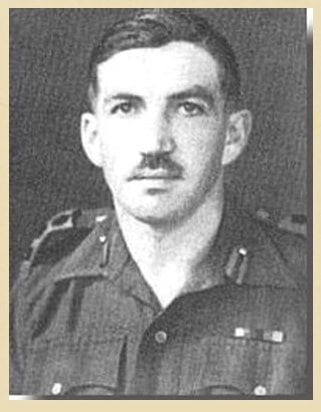

USHER, JOHN ALBERT

Rank: Corporal

Service No: 4199545

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

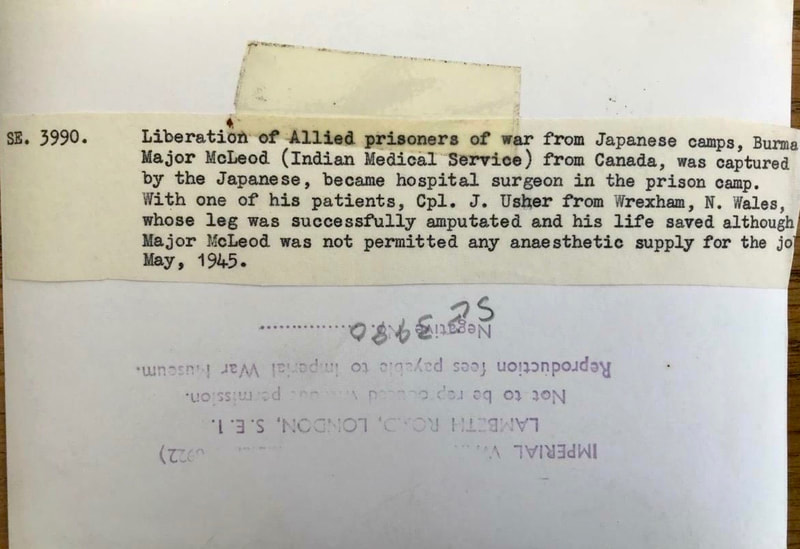

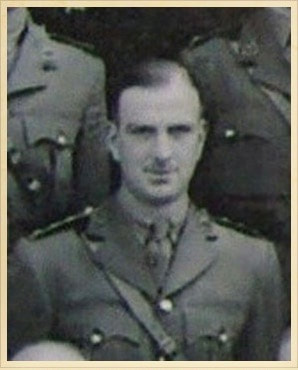

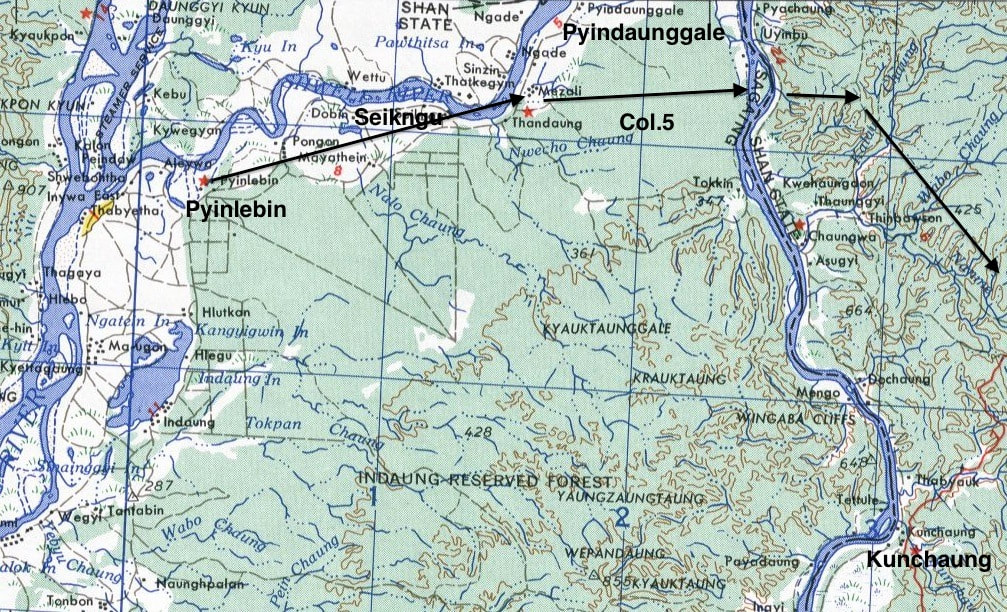

John Albert Usher was born on the 13th March 1916 and was the son of Mary Usher, from Wrexham in North Wales. Originally a soldier with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, Corporal Usher was transferred to the 13th King's on the 30th September 1942, commencing his Chindit training at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India. He was posted to No. 18 Platoon within 8 Column, under the command of Captain Raymond Edward Williams.

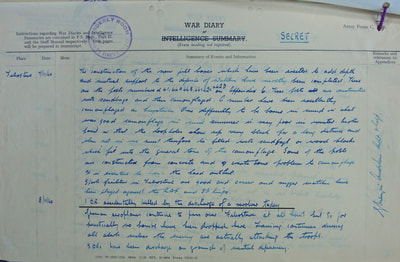

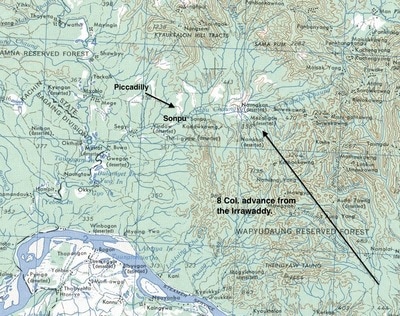

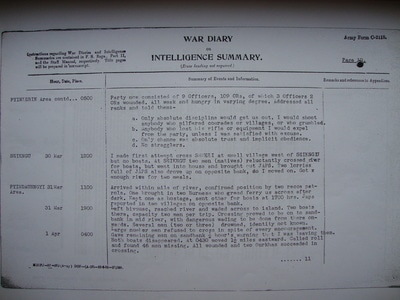

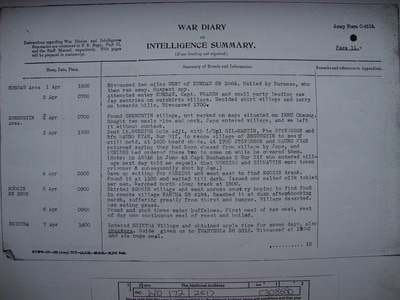

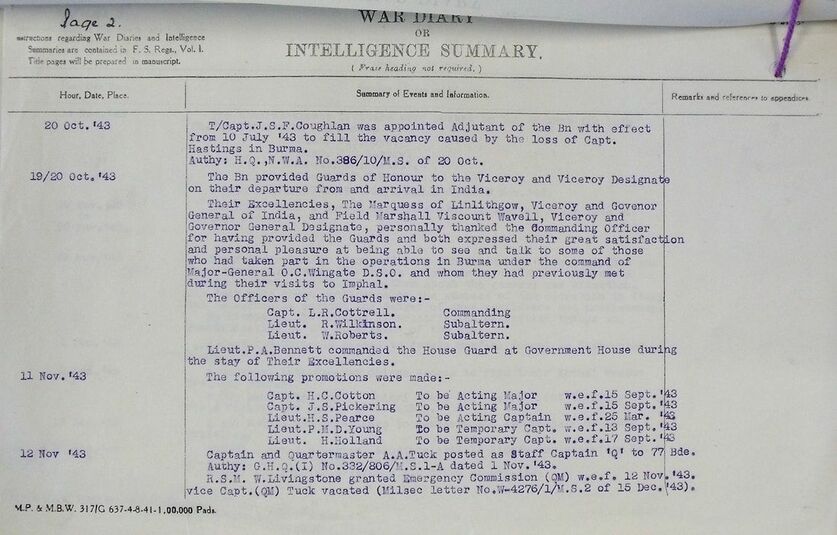

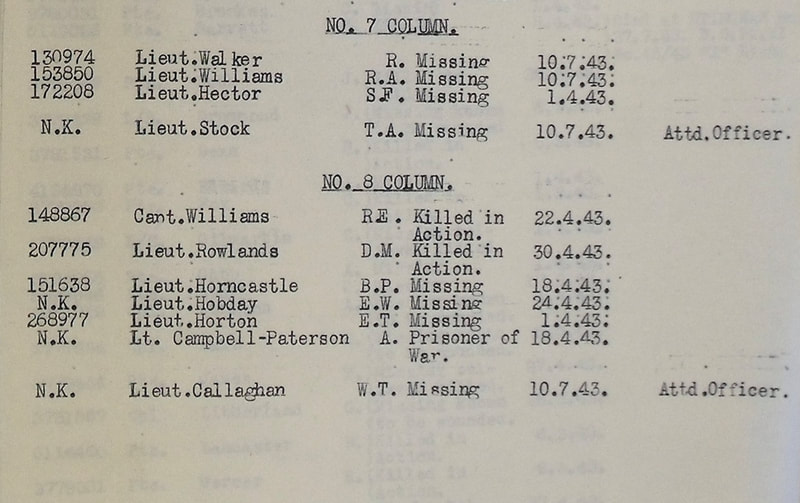

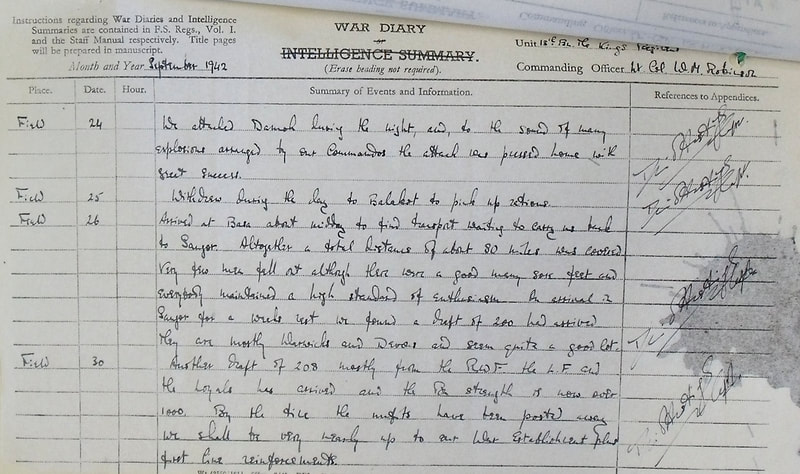

From the War diary of 8 Column dated 1st April 1943:

Recce of the River Shweli carried out during the afternoon and we have decided to cross this evening near the Wingaba Cliffs, S.N. 2563. Column moved down to the river at dusk. Rope got across the river which was flowing very fast on the near side. Captain Williams with two other officers, Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 British Other Ranks crossed the river to form a bridgehead. The next party under Sgt. Scruton got in to difficulties and drifted away down-stream. Both boats having been lost, the crossing was called off. Captain Williams and his party moved from the far bank at first light for the next agreed rendezvous. The rope across the river was withdrawn.

After the aborted crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March 1943, 8 Column led by Major W. P. Scott marched away from the other Chindit columns and headed east towards the Shweli River. As mentioned in the war diary quote above, Captain Williams' platoon were the only section of the column to cross the fast flowing Shweli River on the 1st April. After his group had crossed, a mix up occurred involving the power-rope which the column had secured across the river and no further soldiers could join Captain Williams on the far bank. In the end it was decided that his platoon should continue their march out of India under their own steam.

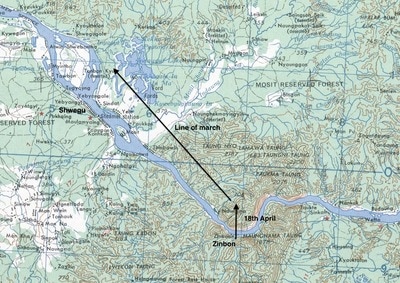

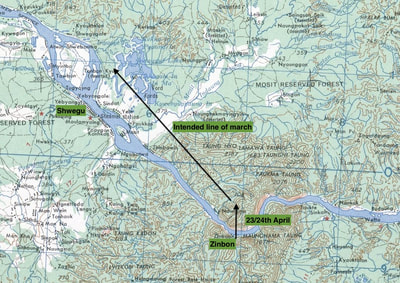

Captain Williams' platoon, of which Corporal Usher was a member, suffered great misfortune from that moment on and were ambushed by the Japanese on no fewer than three occasions over the following weeks. It was during the second ambush on the 17th April 1943 that John Usher was captured by the enemy and began his long sojourn as a prisoner of war. The platoon were approaching the Irrawaddy from the south, close to the Burmese village of Zinbon, when the Japanese surprised the Chindits causing them to disperse in all directions. Many of the men were killed, but Corporal Usher along with four other soldiers were taken prisoner. To read more about Captain Williams and his men, please click on the following link: Captain Williams and Platoon 18

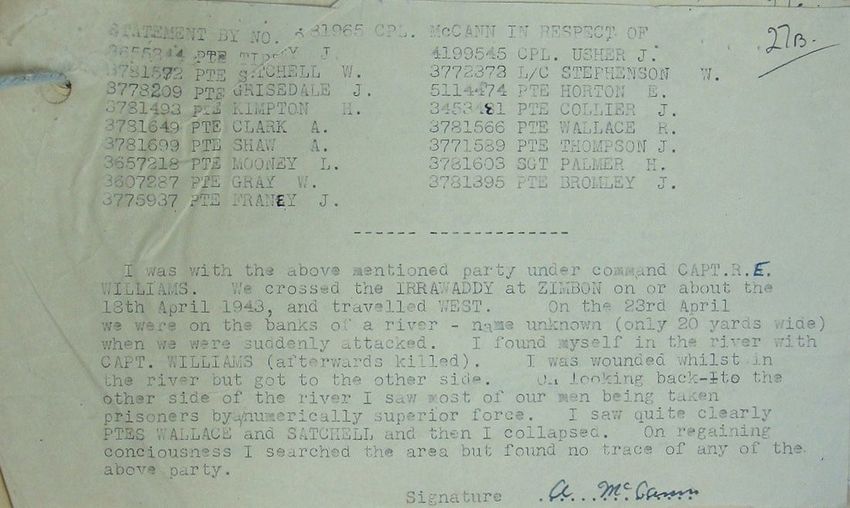

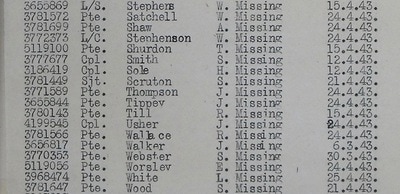

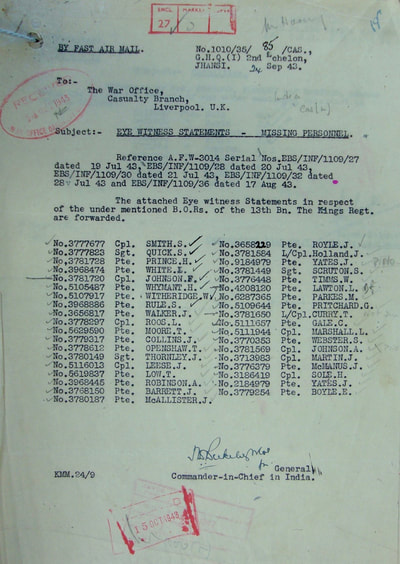

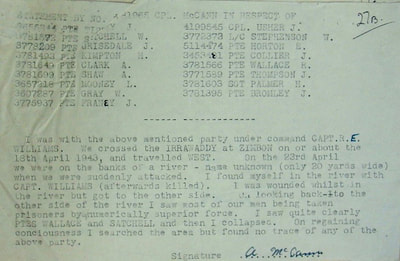

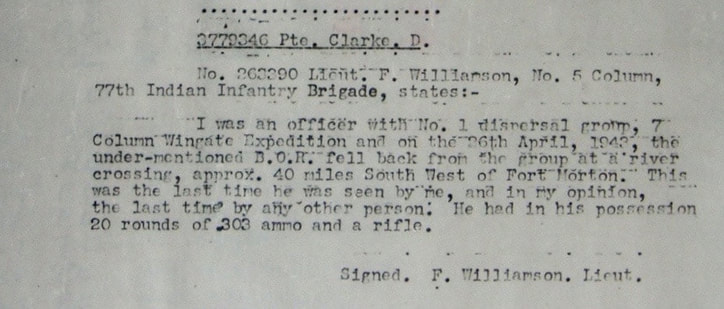

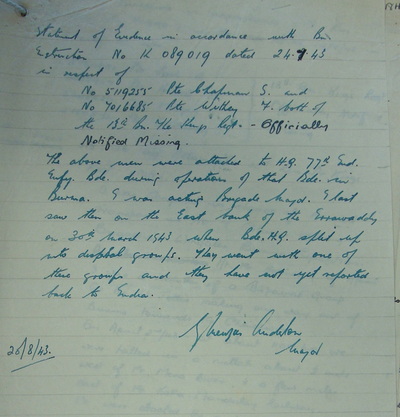

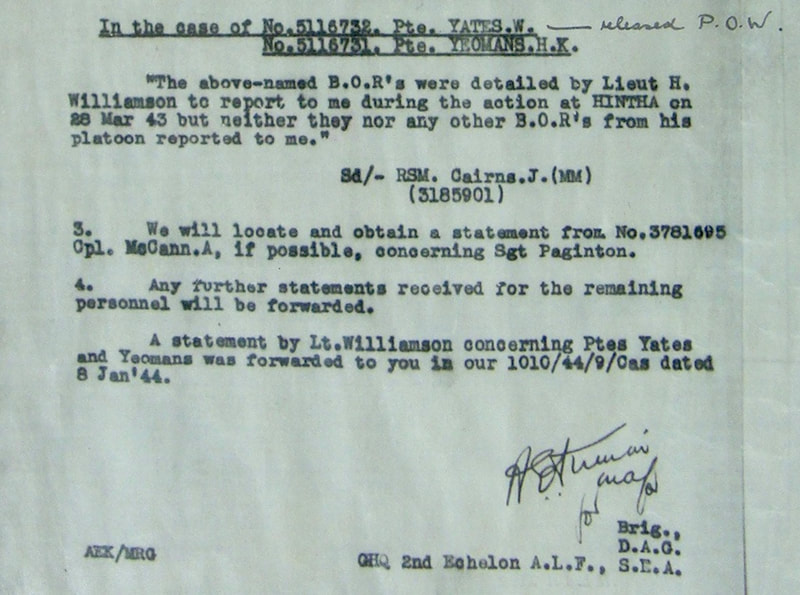

Seen below, is a witness statement with mention of John Usher and some of the other men from Captain Williams' platoon during Operation Longcloth. The account, given by Corporal A. McCann, the only man from the unit to return safely to India in 1943, describes the third ambush suffered by the platoon and the subsequent death of Captain Williams. Corporal Usher was given the official missing in action date of 24th April 1943, based on this witness account, but as we already know he had fallen into Japanese hands one week earlier.

Rank: Corporal

Service No: 4199545

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

John Albert Usher was born on the 13th March 1916 and was the son of Mary Usher, from Wrexham in North Wales. Originally a soldier with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, Corporal Usher was transferred to the 13th King's on the 30th September 1942, commencing his Chindit training at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India. He was posted to No. 18 Platoon within 8 Column, under the command of Captain Raymond Edward Williams.

From the War diary of 8 Column dated 1st April 1943:

Recce of the River Shweli carried out during the afternoon and we have decided to cross this evening near the Wingaba Cliffs, S.N. 2563. Column moved down to the river at dusk. Rope got across the river which was flowing very fast on the near side. Captain Williams with two other officers, Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 British Other Ranks crossed the river to form a bridgehead. The next party under Sgt. Scruton got in to difficulties and drifted away down-stream. Both boats having been lost, the crossing was called off. Captain Williams and his party moved from the far bank at first light for the next agreed rendezvous. The rope across the river was withdrawn.

After the aborted crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March 1943, 8 Column led by Major W. P. Scott marched away from the other Chindit columns and headed east towards the Shweli River. As mentioned in the war diary quote above, Captain Williams' platoon were the only section of the column to cross the fast flowing Shweli River on the 1st April. After his group had crossed, a mix up occurred involving the power-rope which the column had secured across the river and no further soldiers could join Captain Williams on the far bank. In the end it was decided that his platoon should continue their march out of India under their own steam.

Captain Williams' platoon, of which Corporal Usher was a member, suffered great misfortune from that moment on and were ambushed by the Japanese on no fewer than three occasions over the following weeks. It was during the second ambush on the 17th April 1943 that John Usher was captured by the enemy and began his long sojourn as a prisoner of war. The platoon were approaching the Irrawaddy from the south, close to the Burmese village of Zinbon, when the Japanese surprised the Chindits causing them to disperse in all directions. Many of the men were killed, but Corporal Usher along with four other soldiers were taken prisoner. To read more about Captain Williams and his men, please click on the following link: Captain Williams and Platoon 18

Seen below, is a witness statement with mention of John Usher and some of the other men from Captain Williams' platoon during Operation Longcloth. The account, given by Corporal A. McCann, the only man from the unit to return safely to India in 1943, describes the third ambush suffered by the platoon and the subsequent death of Captain Williams. Corporal Usher was given the official missing in action date of 24th April 1943, based on this witness account, but as we already know he had fallen into Japanese hands one week earlier.

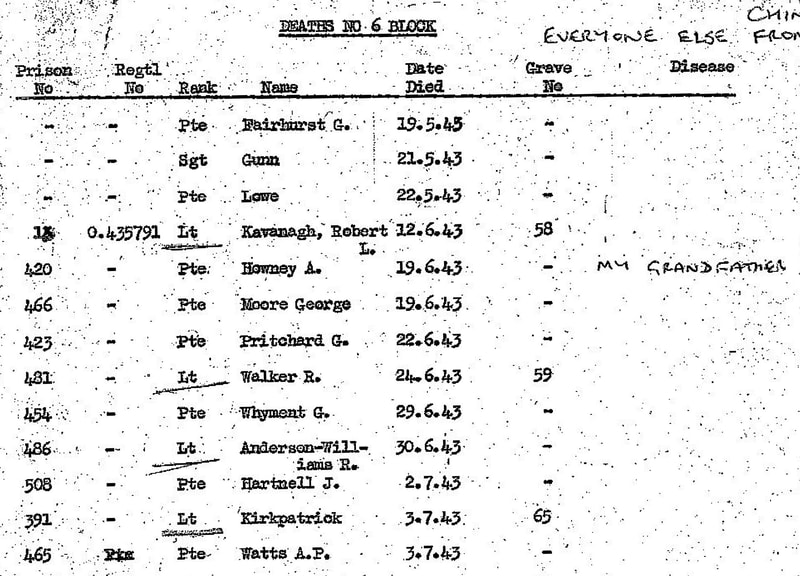

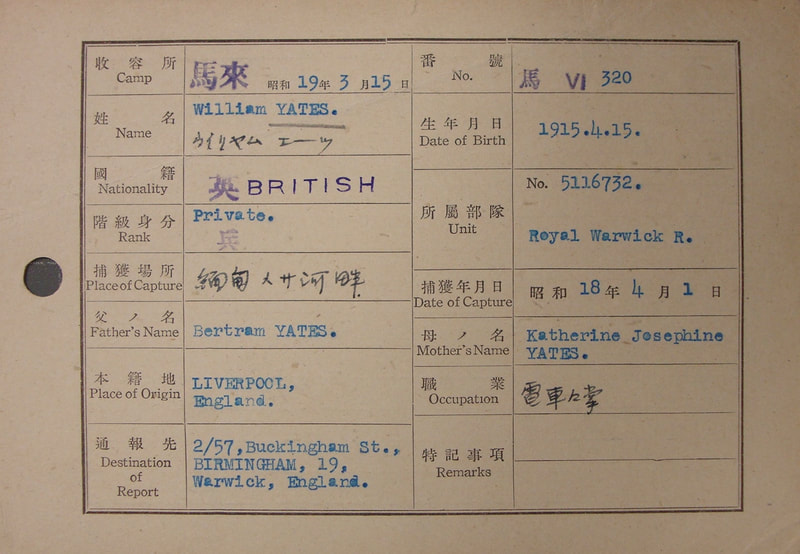

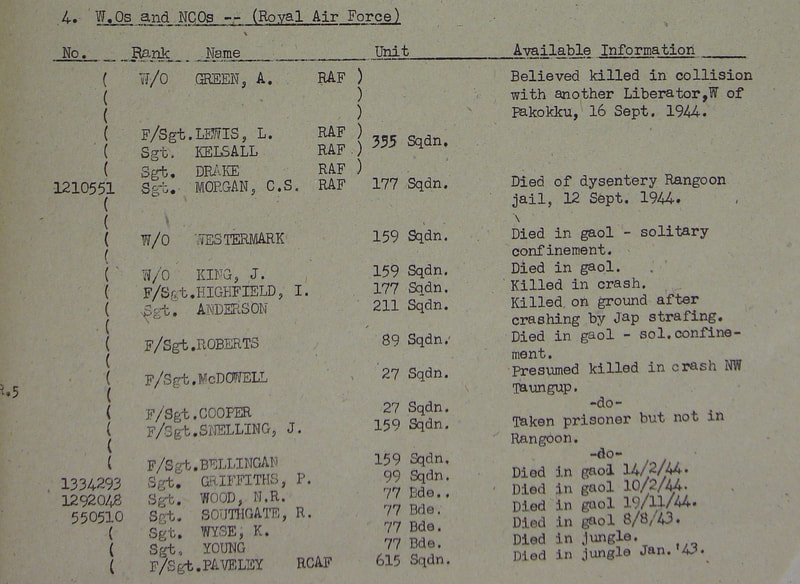

The men captured alongside Corporal Usher were taken to the Maymyo Concentration Camp where many of the Chindits were first collected together by the Japanese. There is anecdotal evidence, from the personal memoir of Sergeant Harold Palmer, that John Usher was present at the Maymyo Camp in May 1943:

After seven days, we were taken to Maymyo, where we found other POW’s from our column including the unlucky boat party. Just before the monsoons in May, 100 of us were sent to Rangoon prison, where 300 men from the 1942 campaign had already done 18 months. My God, I thought, I’ll never do that long.

At Rangoon, the Japs amputated a leg from Corporal Usher of Wrexham, and an arm from Pte. Roche from Liverpool. They took them from the cells one morning to the general hospital and brought them back again on stretchers, and were putting them into a (communal) cell again, when I suggested that another cell could be used. Our own interpreter asked the Japs and they saw the light and they opened a disused block and put the two boys in a dirty cell and gave them six bananas to eat. Because I had been doing the dirty medical work for the Japs when they dressed the wounded on the way to Maymyo, I volunteered to stay with them (Usher and Roche). Those wounds had a lousy stink, and the Japs, even with their proverbial gauze masks, had me take off the old bandages before they treated the wounds. They were very short of medical kit. Those two boys suffered terrible nerve pains and for a few nights there wasn’t much peace for them.

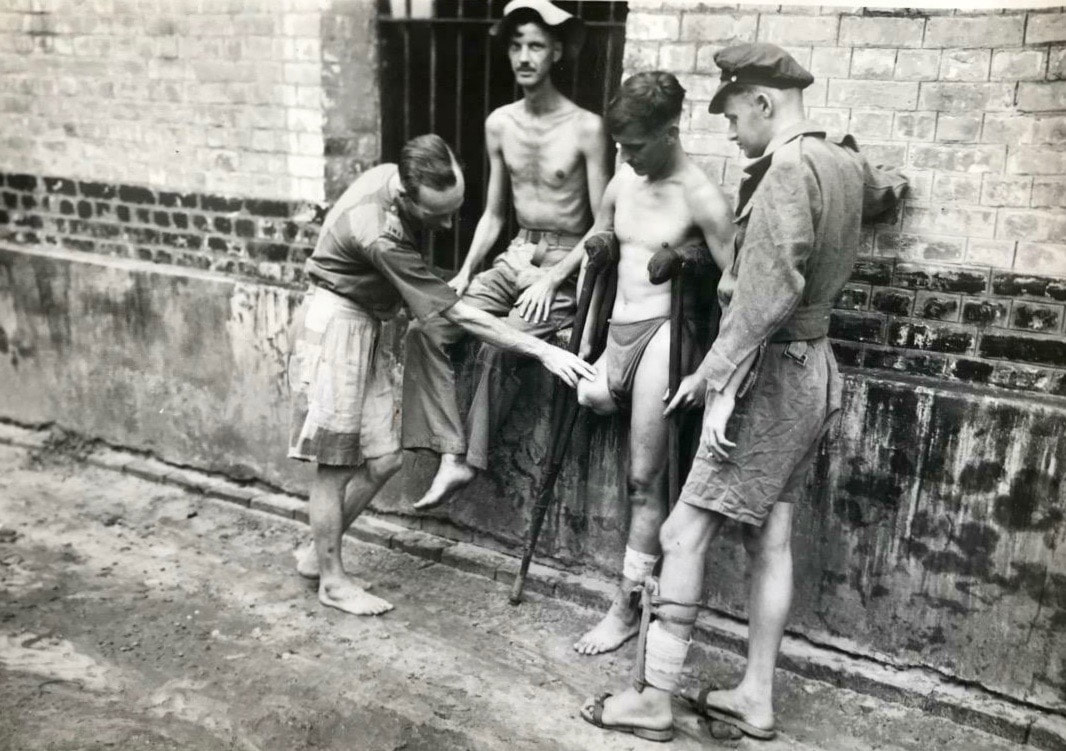

Corporal Usher had suffered with severe and infected jungle sores for several weeks before he became a prisoner of war at Zinbon. With little medical attention given by the Japanese, these had become ulcerated and it became necessary to remove his right leg from just above the knee. In the book, Operation Rangoon Jail, by Colonel K.P. Mackenzie, another of the British Army doctors present inside the jail, it is suggested that Major Norman McLeod of the Indian Medical Service performed the actual surgery on Corporal Usher:

McLeod also performed some remarkably difficult operations in Rangoon Jail. I was not present at any of these, but saw some of the results he obtained, when amputating without anaesthetics. One case in which he achieved a wonderful result was when he removed the leg of a sturdy little Welshman, Corporal J. Usher from Wrexham, just below the thigh. Thanks to the skill of McLeod, Usher made an excellent recovery and was amongst the party that was liberated when the British eventually re-entered Rangoon.

Corporal Usher spent just under two years living in cell block no. 6 with the rest of the men captured during the first Wingate expedition. He had been given the POW number 105 and had to recite this number in the Japanese language, at both morning and evening roll call. According to the information on the reverse of his POW index card, John was one of a group of men who were marched out of the jail by the Japanese guards and who were subsequently given their freedom close to the Burmese town of Pegu on the 29th April 1945. Personally, I find it difficult to believe that Corporal Usher, with his obvious disability, would have been chosen by the senior British officers, as one of the men deemed fit enough to make the march that April. It seems more probable that he would have remained at the jail with the rest of the prisoners and was liberated from this location a few days later on the 2nd May.

After liberation, the men freed from Rangoon Jail were sent back to India aboard HMHS Karapara and spent a period of time recuperating in hospital at Calcutta. Most men were then posted back to their regiment before capture, which in Corporal Usher's case would have been the 13th King's at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. John was repatriated a few weeks later, arriving back in the United Kingdom on the 17th August 1945. He then spent sometime at Calderstones Hospital in the village of Whalley near Blackburn. John Albert Usher died aged 69 in the winter of 1985, he was residing in the Blackpool area at the time.

Seen below are some more images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After seven days, we were taken to Maymyo, where we found other POW’s from our column including the unlucky boat party. Just before the monsoons in May, 100 of us were sent to Rangoon prison, where 300 men from the 1942 campaign had already done 18 months. My God, I thought, I’ll never do that long.

At Rangoon, the Japs amputated a leg from Corporal Usher of Wrexham, and an arm from Pte. Roche from Liverpool. They took them from the cells one morning to the general hospital and brought them back again on stretchers, and were putting them into a (communal) cell again, when I suggested that another cell could be used. Our own interpreter asked the Japs and they saw the light and they opened a disused block and put the two boys in a dirty cell and gave them six bananas to eat. Because I had been doing the dirty medical work for the Japs when they dressed the wounded on the way to Maymyo, I volunteered to stay with them (Usher and Roche). Those wounds had a lousy stink, and the Japs, even with their proverbial gauze masks, had me take off the old bandages before they treated the wounds. They were very short of medical kit. Those two boys suffered terrible nerve pains and for a few nights there wasn’t much peace for them.

Corporal Usher had suffered with severe and infected jungle sores for several weeks before he became a prisoner of war at Zinbon. With little medical attention given by the Japanese, these had become ulcerated and it became necessary to remove his right leg from just above the knee. In the book, Operation Rangoon Jail, by Colonel K.P. Mackenzie, another of the British Army doctors present inside the jail, it is suggested that Major Norman McLeod of the Indian Medical Service performed the actual surgery on Corporal Usher:

McLeod also performed some remarkably difficult operations in Rangoon Jail. I was not present at any of these, but saw some of the results he obtained, when amputating without anaesthetics. One case in which he achieved a wonderful result was when he removed the leg of a sturdy little Welshman, Corporal J. Usher from Wrexham, just below the thigh. Thanks to the skill of McLeod, Usher made an excellent recovery and was amongst the party that was liberated when the British eventually re-entered Rangoon.

Corporal Usher spent just under two years living in cell block no. 6 with the rest of the men captured during the first Wingate expedition. He had been given the POW number 105 and had to recite this number in the Japanese language, at both morning and evening roll call. According to the information on the reverse of his POW index card, John was one of a group of men who were marched out of the jail by the Japanese guards and who were subsequently given their freedom close to the Burmese town of Pegu on the 29th April 1945. Personally, I find it difficult to believe that Corporal Usher, with his obvious disability, would have been chosen by the senior British officers, as one of the men deemed fit enough to make the march that April. It seems more probable that he would have remained at the jail with the rest of the prisoners and was liberated from this location a few days later on the 2nd May.

After liberation, the men freed from Rangoon Jail were sent back to India aboard HMHS Karapara and spent a period of time recuperating in hospital at Calcutta. Most men were then posted back to their regiment before capture, which in Corporal Usher's case would have been the 13th King's at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. John was repatriated a few weeks later, arriving back in the United Kingdom on the 17th August 1945. He then spent sometime at Calderstones Hospital in the village of Whalley near Blackburn. John Albert Usher died aged 69 in the winter of 1985, he was residing in the Blackpool area at the time.

Seen below are some more images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 14/12/2018.

I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Michael Clayton Usher, nephew of John Usher:

Hi Stephen,

My Uncle was Corporal John Usher and I have enjoyed reading about him and the other Chindits on your website. He came from a very large family, seven brothers and four sisters, sadly all have now passed away. I have many happy memories of my uncle from when I was a youngster and will without a doubt read through more of your pages. As with so many of those returning from war, he did not ever talk about his experiences as a prisoner of war, well certainly not to his family anyway. I guess he took those painful memories to his grave when he died in 1985. Many thanks again for this fantastic website.

I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Michael Clayton Usher, nephew of John Usher:

Hi Stephen,

My Uncle was Corporal John Usher and I have enjoyed reading about him and the other Chindits on your website. He came from a very large family, seven brothers and four sisters, sadly all have now passed away. I have many happy memories of my uncle from when I was a youngster and will without a doubt read through more of your pages. As with so many of those returning from war, he did not ever talk about his experiences as a prisoner of war, well certainly not to his family anyway. I guess he took those painful memories to his grave when he died in 1985. Many thanks again for this fantastic website.

Update 20/02/2021.

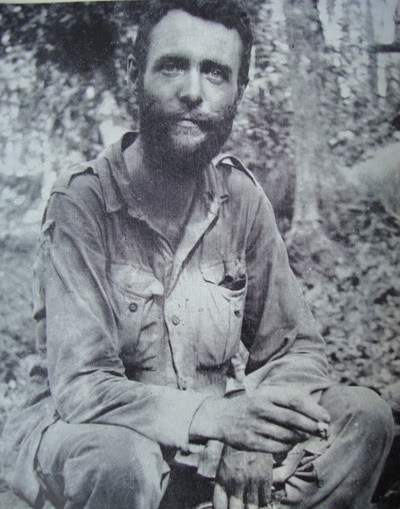

I was pleased to receive a copy of the official war photograph showing Major Norman McLeod, one of the medical officers held at Rangoon Jail during the years 1942-45, examining James Usher's leg after his amputation. This image has become one of the most well-known and iconic images in relation to the story of Rangoon Jail and the Allied prisoners held there during the war. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

I was pleased to receive a copy of the official war photograph showing Major Norman McLeod, one of the medical officers held at Rangoon Jail during the years 1942-45, examining James Usher's leg after his amputation. This image has become one of the most well-known and iconic images in relation to the story of Rangoon Jail and the Allied prisoners held there during the war. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

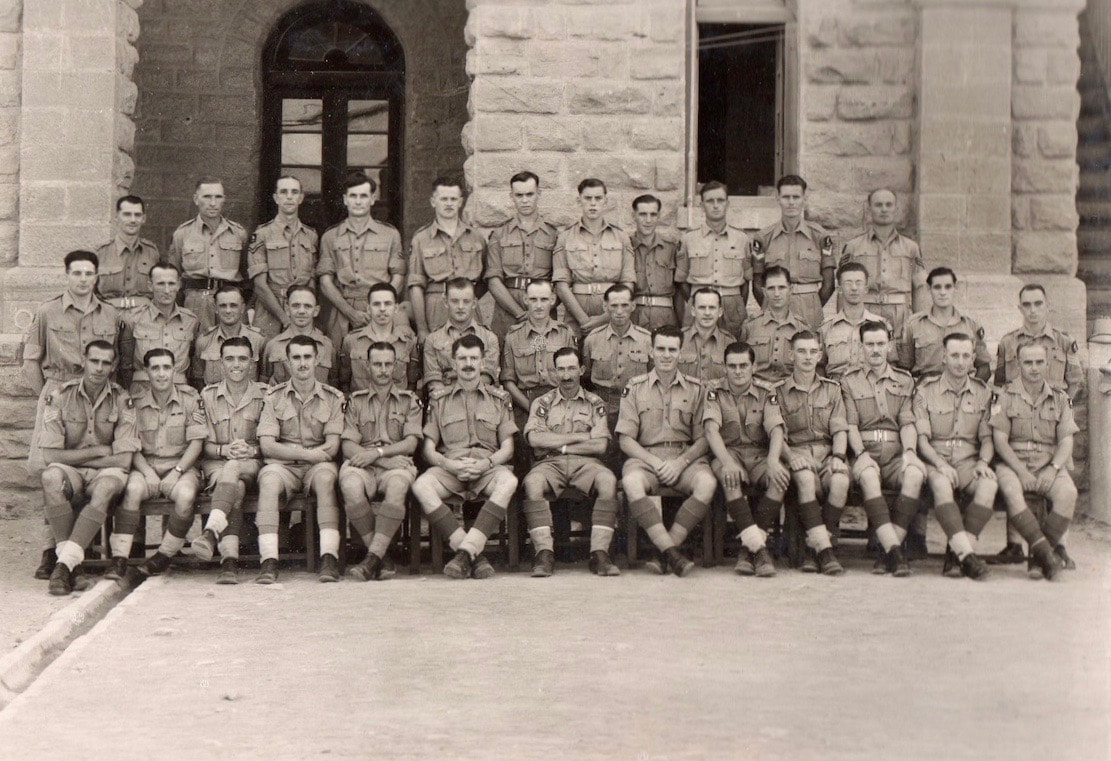

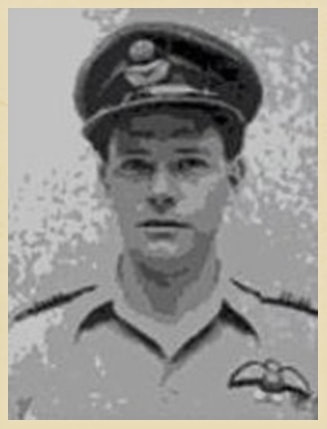

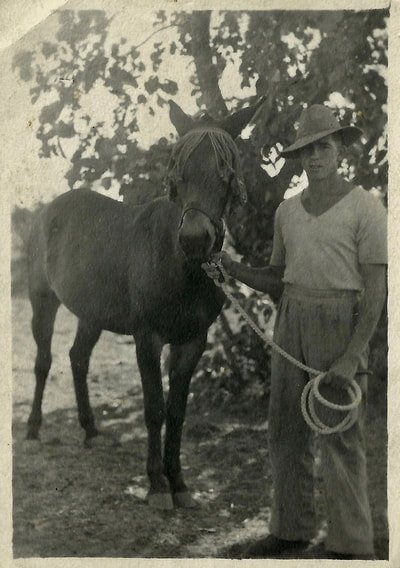

William Vandivert, India April 1943.

William Vandivert, India April 1943.

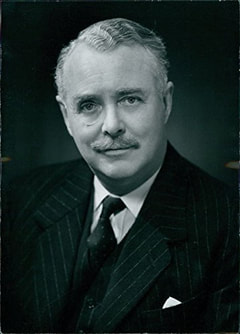

VANDIVERT, WILLIAM WILSON

Chindit Column: Honorary 8

William Wilson Vandivert was born in the U.S. state of Illinois on the 16th August 1912. He became a well known photographer for the American lifestyle magazine, Life and was renowned for his front line images from the many combat theatres of WW2.

William became involved with the Chindit story in April 1943, when he took a ride in a RAF Dakota aircraft, which was about to attempt a landing in the Burmese jungle, in order to rescue a number of sick and wounded Chindits. These men were from 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment. The photographs taken by Vandivert on that day, were to become the most recognisable photographs from the first Wingate expedition and some of the most iconic images from the Burma campaign overall. Of course, his exploits during what became known as the Piccadilly incident, resulted in Vandivert, and the pilot of the Dakota, Michael Vlasto, becoming honorary Chindits in the eyes of the men they extricated from the Burmese jungle.

To read more about the Dakota rescue at Sonpu, please click on the following link:

The Piccadilly Incident

William Vandivert, working at the time as a war correspondent for Illustrated Magazine, wrote an article about his adventure aboard the Dakota and his meeting with the beleaguered Chindits in April 1943. From the pages of Illustrated Magazine dated 10th July 1943:

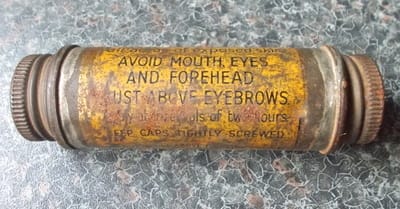

Deep Jungle Sores

The Colonel, C.O. of one of the groups, sat a step apart at the rear of the plane. Beneath his collar I could see deep, open jungle sores. I stopped beside him as he fumbled through two small packets that were all he had brought with him. From a map folder he carefully drew a folded copy of Punch, and laughed helplessly—until a fit of coughing racked it short. It was a copy we had dropped on the Sunday.

A ruptured soldier was barely holding himself together, biting his lips in agony. Man-handling machine guns through the hills, he had ripped himself in a fall. He suddenly leaned over, vomiting. A toad from a Tommy's pack hopped aimlessly until it found a quiet corner. Leaning forward to catch it, a grenade spilled from the soldier's breast pocket and rolled down the floor. The toad disappeared and the soldier fondled the grenade. Clutching his head, the Burmese crumpled up, groaning, and we cleared a place to lay him rolled in blankets. He was suffering from severe malaria.

I sat beside the Colonel, and to the punctuation of that cough, I learned the story of his column. They had been hard on the offensive until a week across the Irrawaddy. They had scored well. Then after the final supply-drop they had split up to recross the river on their return journey and for the first time they had been hunted, not hunters. They had bumped into a Japanese patrol, fought well, and headed north. Under the hill by the Irrawaddy they had camped for two days, waiting. River steamer towns above and below them were heavily garrisoned now and all river traffic operated under protection. But on the third morning they had watched three small guard boats work upstream, followed, after half an hour, by a junk creeping up the opposite shore. She had tacked across and grounded on a mudbank right below.

The troops swarmed out like pirates, took her and hauled back three of her crew who had dived over the side. Less than two hours later they were all across the toughest hurdle, even their last mule. Two days later, however, she died and the radio she carried sent one last message for our supply drop. The mule was buried in the bush. They had no rations and, foraging in a village,‘ they had found only one cup of rice per man. Japanese patrols had stripped bare the whole countryside along the river. Two days before the rendezvous the men had begun eating jungle leaves and "succulent" bamboo. They began dropping like flies with hunger. The hardest thing in this warfare had been leaving casualties in the column's track. But that was a law by which all these forces had to move. " Right here," said the colonel, "we all came very close to God."

Our supplies had saved them. Sunday's drop had turned the tide of fortune. Some stragglers had come up. With rations and unexpected rest they now were fit again for the march to India, racing against time, monsoons and impassable rivers. That was the story. The pilot then gave permission to smoke. The corporal on the end seat, Fred Nightingale, of Lancaster, handed me a battered tin, saying : "Here, have one of mine. They fly them specially from India for me." A chunk of white parachute around Nightingale's neck made him look garish. Ulcers had worn him thin. The last two days to the rendezvous had been his last effort, and he had known it; will power had just kept him moving. He had straggled back to the rear of the column and seen men dropping by the dusty jungle track. It happened quietly.

One chum, with jungle sores deeply infecting his legs, just couldn't lift them again. He had dropped, saying softly : "Well, I guess I've had it." The column had moved slowly on and dust had settled. The ruptured soldier sat silently forward, elbows on knees. I asked him about the jungle and he only said: "It's bitter cruel." He was Corporal Jimmy Walker, who had dropped two days before the rendezvous with dysentery and infected hips. It was only his great will, too, that had brought him hobbling in the day before.

Then there were the gay ones. Private Jim Suddery, of Islington, North London, for example, fumbled through his purse and held out a light Japanese rifle slug. It had entered his back, rib high, and come out, a purple spot on his belly. " Souvenir," he chuckled, adding : " but you should have seen the ones we gave out."

We crossed the Chindwin through broken cloud and the men peered out, seeing in one hour and a quarter what they had marched across in previous weeks. Landing was a let down. Dead weariness set in again. In reaction to stand and file through the door-way became another incredible effort of will. Strangely, when they were on the ground, most of them stood unconscious again of packs, talking with fighter pilots who had brought us through. Two Japanese fighters had seen us, but had not made a pass at us. Ambulances finally arrived. Flight Sergeant May and I watched them roll away. He said : " Well, I guess that's helping England." H.Q. said no more landings, and we had to agree.

To learn more about William Vandivert and to view more of his photographic portfolio, please click on the following link:

photographyandarthistory.wordpress.com/category/william-vandivert/

William Vandivert sadly died on the 1st December 1989. Shown below are some images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Chindit Column: Honorary 8

William Wilson Vandivert was born in the U.S. state of Illinois on the 16th August 1912. He became a well known photographer for the American lifestyle magazine, Life and was renowned for his front line images from the many combat theatres of WW2.

William became involved with the Chindit story in April 1943, when he took a ride in a RAF Dakota aircraft, which was about to attempt a landing in the Burmese jungle, in order to rescue a number of sick and wounded Chindits. These men were from 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment. The photographs taken by Vandivert on that day, were to become the most recognisable photographs from the first Wingate expedition and some of the most iconic images from the Burma campaign overall. Of course, his exploits during what became known as the Piccadilly incident, resulted in Vandivert, and the pilot of the Dakota, Michael Vlasto, becoming honorary Chindits in the eyes of the men they extricated from the Burmese jungle.

To read more about the Dakota rescue at Sonpu, please click on the following link:

The Piccadilly Incident

William Vandivert, working at the time as a war correspondent for Illustrated Magazine, wrote an article about his adventure aboard the Dakota and his meeting with the beleaguered Chindits in April 1943. From the pages of Illustrated Magazine dated 10th July 1943:

Deep Jungle Sores

The Colonel, C.O. of one of the groups, sat a step apart at the rear of the plane. Beneath his collar I could see deep, open jungle sores. I stopped beside him as he fumbled through two small packets that were all he had brought with him. From a map folder he carefully drew a folded copy of Punch, and laughed helplessly—until a fit of coughing racked it short. It was a copy we had dropped on the Sunday.

A ruptured soldier was barely holding himself together, biting his lips in agony. Man-handling machine guns through the hills, he had ripped himself in a fall. He suddenly leaned over, vomiting. A toad from a Tommy's pack hopped aimlessly until it found a quiet corner. Leaning forward to catch it, a grenade spilled from the soldier's breast pocket and rolled down the floor. The toad disappeared and the soldier fondled the grenade. Clutching his head, the Burmese crumpled up, groaning, and we cleared a place to lay him rolled in blankets. He was suffering from severe malaria.

I sat beside the Colonel, and to the punctuation of that cough, I learned the story of his column. They had been hard on the offensive until a week across the Irrawaddy. They had scored well. Then after the final supply-drop they had split up to recross the river on their return journey and for the first time they had been hunted, not hunters. They had bumped into a Japanese patrol, fought well, and headed north. Under the hill by the Irrawaddy they had camped for two days, waiting. River steamer towns above and below them were heavily garrisoned now and all river traffic operated under protection. But on the third morning they had watched three small guard boats work upstream, followed, after half an hour, by a junk creeping up the opposite shore. She had tacked across and grounded on a mudbank right below.

The troops swarmed out like pirates, took her and hauled back three of her crew who had dived over the side. Less than two hours later they were all across the toughest hurdle, even their last mule. Two days later, however, she died and the radio she carried sent one last message for our supply drop. The mule was buried in the bush. They had no rations and, foraging in a village,‘ they had found only one cup of rice per man. Japanese patrols had stripped bare the whole countryside along the river. Two days before the rendezvous the men had begun eating jungle leaves and "succulent" bamboo. They began dropping like flies with hunger. The hardest thing in this warfare had been leaving casualties in the column's track. But that was a law by which all these forces had to move. " Right here," said the colonel, "we all came very close to God."

Our supplies had saved them. Sunday's drop had turned the tide of fortune. Some stragglers had come up. With rations and unexpected rest they now were fit again for the march to India, racing against time, monsoons and impassable rivers. That was the story. The pilot then gave permission to smoke. The corporal on the end seat, Fred Nightingale, of Lancaster, handed me a battered tin, saying : "Here, have one of mine. They fly them specially from India for me." A chunk of white parachute around Nightingale's neck made him look garish. Ulcers had worn him thin. The last two days to the rendezvous had been his last effort, and he had known it; will power had just kept him moving. He had straggled back to the rear of the column and seen men dropping by the dusty jungle track. It happened quietly.

One chum, with jungle sores deeply infecting his legs, just couldn't lift them again. He had dropped, saying softly : "Well, I guess I've had it." The column had moved slowly on and dust had settled. The ruptured soldier sat silently forward, elbows on knees. I asked him about the jungle and he only said: "It's bitter cruel." He was Corporal Jimmy Walker, who had dropped two days before the rendezvous with dysentery and infected hips. It was only his great will, too, that had brought him hobbling in the day before.

Then there were the gay ones. Private Jim Suddery, of Islington, North London, for example, fumbled through his purse and held out a light Japanese rifle slug. It had entered his back, rib high, and come out, a purple spot on his belly. " Souvenir," he chuckled, adding : " but you should have seen the ones we gave out."

We crossed the Chindwin through broken cloud and the men peered out, seeing in one hour and a quarter what they had marched across in previous weeks. Landing was a let down. Dead weariness set in again. In reaction to stand and file through the door-way became another incredible effort of will. Strangely, when they were on the ground, most of them stood unconscious again of packs, talking with fighter pilots who had brought us through. Two Japanese fighters had seen us, but had not made a pass at us. Ambulances finally arrived. Flight Sergeant May and I watched them roll away. He said : " Well, I guess that's helping England." H.Q. said no more landings, and we had to agree.

To learn more about William Vandivert and to view more of his photographic portfolio, please click on the following link:

photographyandarthistory.wordpress.com/category/william-vandivert/

William Vandivert sadly died on the 1st December 1989. Shown below are some images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Cap badge of the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry.

Cap badge of the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry.

VAUSE, BERNARD

Rank: Private

Service No: 4691027

Regiment/Service: 2nd King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry attached The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Other details:

Bernard Vause served with the 2nd Battalion, the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry and came from Pontefract in West Yorkshire. Bernard, who survived the retreat from Burma in early 1942, is credited with scouting for Operation Longcloth prior to 77 Brigade crossing the Chindiwn River in February 1943.

Rank: Private

Service No: 4691027

Regiment/Service: 2nd King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry attached The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Other details:

Bernard Vause served with the 2nd Battalion, the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry and came from Pontefract in West Yorkshire. Bernard, who survived the retreat from Burma in early 1942, is credited with scouting for Operation Longcloth prior to 77 Brigade crossing the Chindiwn River in February 1943.

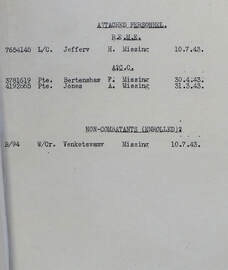

VENKETSWAMY

Rank: Private

Service No: B/94

Regiment/Service: Attached 77 Brigade

Other details:

This man was recorded as missing from the first Wingate expedition as of the 10th July 1943 and is listed as a non-combatant. There were several Indian non-combatants on Operation Longcloth, mostly serving as cooks, water-carriers and servants, but nothing else is known about Venketswamy or his disappearance in Burma. Please click on the image (left) to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: B/94

Regiment/Service: Attached 77 Brigade

Other details:

This man was recorded as missing from the first Wingate expedition as of the 10th July 1943 and is listed as a non-combatant. There were several Indian non-combatants on Operation Longcloth, mostly serving as cooks, water-carriers and servants, but nothing else is known about Venketswamy or his disappearance in Burma. Please click on the image (left) to bring it forward on the page.

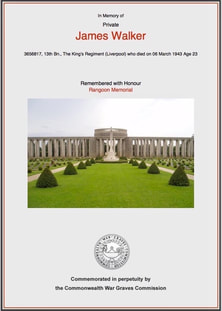

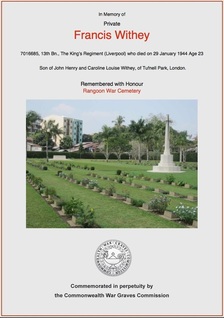

CWGC certificate for James Walker.

CWGC certificate for James Walker.

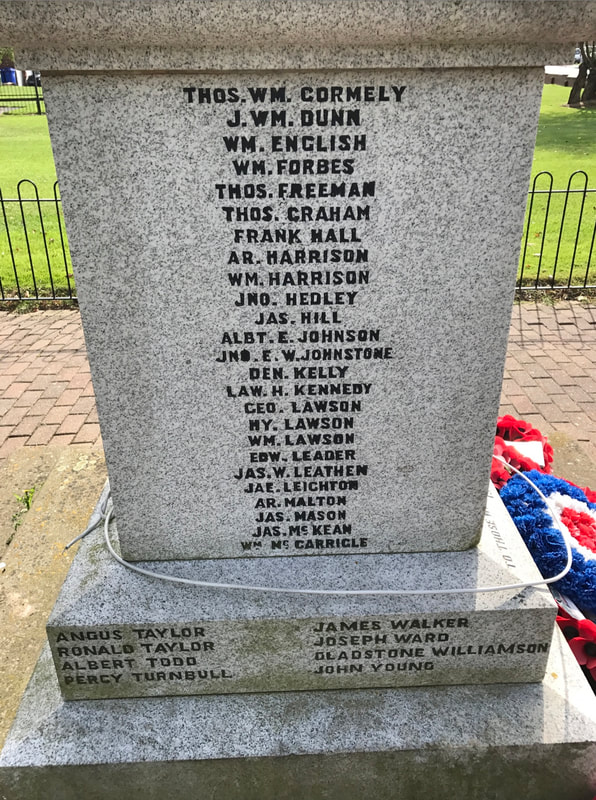

WALKER, JAMES

Rank: Private

Service No: 3656817

Date of Death: 06/03/1943

Age: 23

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2528218/walker,-james/

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

Pte. James Walker originally enlisted into the Prince of Wales Own Volunteers (South Lancashire) Regiment. He was then posted overseas to India in mid-1942 and was transferred to the King's Regiment, joining them at Saugor in the Central Provinces in late September that same year.

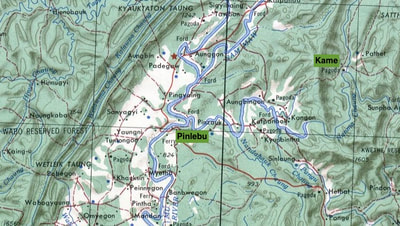

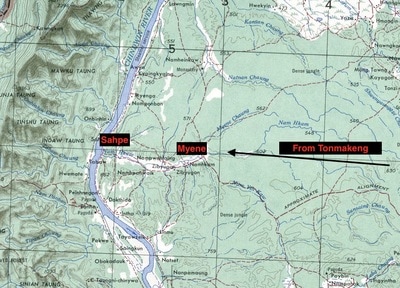

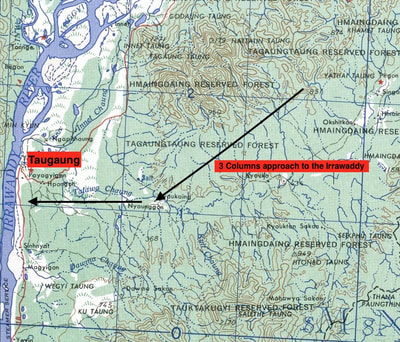

James was allocated to Chindit Column No. 8 during training and entered Burma with this unit on the 15th February 1943. His date of death, the 6th of March 1943, corresponds with the columns short battle with the Japanese along the Pinlebu/Kame Road. His entry within the missing in action reports for the 13th King's simply states that he was last seen withdrawing across a river near the village of Kame. This was most likely the Nanma Chaung (please see the map in the gallery below).

No. 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott, had been given the orders to secure and block the road out of Pinlebu on the 4th March in order to protect a large supply drop expected by the Chindits further to the east. From the column war diary:

4th and 5th March: column moved into the area around Pinlebu, there were said to be 600-1000 enemy troops in this locality. The Burma Rifle Officers had spoken to a native of the area, he turned out to be a Japanese spy and was shot. Water parties were sent out to replenish supplies, these units were engaged by enemy patrols but most managed to disengage and return to the main body.

More minor clashes with the Japanese were incurred late on 5th March, the column then moved to the agreed rendezvous on the Pinlebu-Kame Road. The party halted one mile north of Kame and settled down for the night. Their position was chosen by Major Scott and units were deployed to prevent any Japanese movement toward Pinlebu from this direction.

At first light on the 6th March, the Sabotage Squad led by Lieutenant Sprague and 16 Platoon set out toward Kame to secure the road block. At about 1100 hours Sprague’s men were attacked by the Japanese from all sides, he called dispersal in an attempt to extract his men, it was here that Lieutenant Callaghan was shot and killed. At 1600 hours the whole column moved away toward the Supply drop rendezvous area.

So as you can see the situation was very confused, with enemy troops engaging the column positions on several occasions during the three day period. It would seem likely that James was a member of Platoon 16 under Lt. Callaghan, as he does not feature in the nominal rolls for Lt. Sprague's commandos.

Another good source of information from this period can be found in the book Wingate Adventure by W.G. Burchett:

As No. 2 Group neared Pinlebu, Gilkes and Brigade HQ moved east to arrange a Supply drop zone, whilst Major Scott’s Column took up defensive positions around Pinlebu. On the 5th March, Scott occupied a village two and a half miles from Pinlebu and sent his patrols out covering all directions. The Japanese were everywhere, but usually betrayed their positions early by blazing away at the slightest movement or noise.

The minor battle lasted all day and into the night, dispersal was then called and the column moved away. Early on the 6th March, Scott set up roadblocks leading east and north out of Pinlebu, the supply drop continued unhindered. Scott had no sooner closed the roadblocks and was preparing to move off, when a Japanese patrol opened fire on one of the furthest placed groups. A brisk thirty-minute battle ensued, leaving six men killed or badly wounded. Column 8 withdrew to safer ground. For the loss of six men the column had held up the enemy for over 24 hours, covering Calvert and Fergusson’s dash to the railway and allowing HQ to secure a vital supply drop.

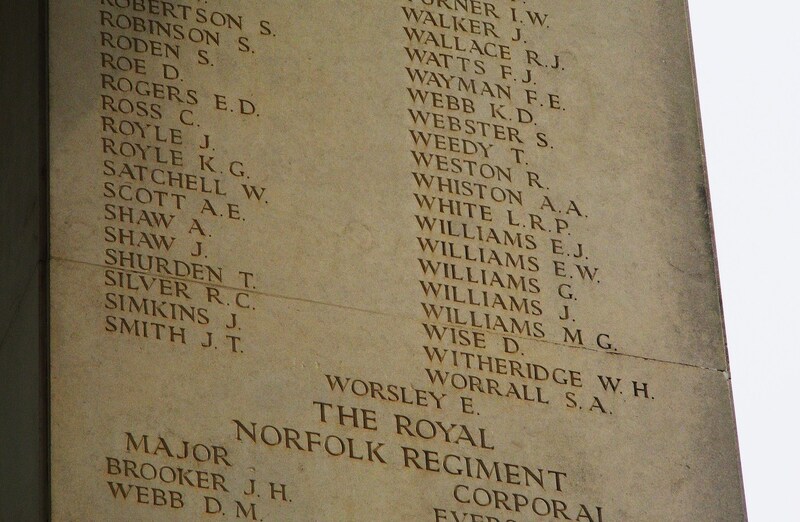

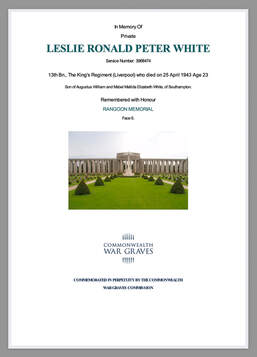

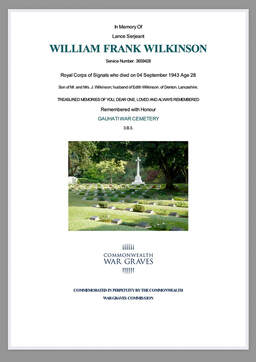

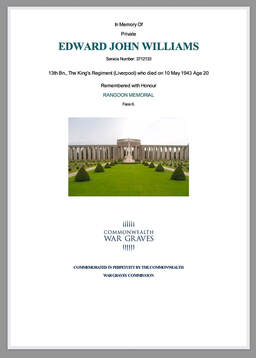

Sadly, Pte. Walker's body was never recovered after the war and for this reason he is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial in Taukkyan War Cemetery. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this short story including photographs of two other Chindits lost on the Pinlebu/Kame Road. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: 3656817

Date of Death: 06/03/1943

Age: 23

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2528218/walker,-james/

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

Pte. James Walker originally enlisted into the Prince of Wales Own Volunteers (South Lancashire) Regiment. He was then posted overseas to India in mid-1942 and was transferred to the King's Regiment, joining them at Saugor in the Central Provinces in late September that same year.

James was allocated to Chindit Column No. 8 during training and entered Burma with this unit on the 15th February 1943. His date of death, the 6th of March 1943, corresponds with the columns short battle with the Japanese along the Pinlebu/Kame Road. His entry within the missing in action reports for the 13th King's simply states that he was last seen withdrawing across a river near the village of Kame. This was most likely the Nanma Chaung (please see the map in the gallery below).

No. 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott, had been given the orders to secure and block the road out of Pinlebu on the 4th March in order to protect a large supply drop expected by the Chindits further to the east. From the column war diary:

4th and 5th March: column moved into the area around Pinlebu, there were said to be 600-1000 enemy troops in this locality. The Burma Rifle Officers had spoken to a native of the area, he turned out to be a Japanese spy and was shot. Water parties were sent out to replenish supplies, these units were engaged by enemy patrols but most managed to disengage and return to the main body.

More minor clashes with the Japanese were incurred late on 5th March, the column then moved to the agreed rendezvous on the Pinlebu-Kame Road. The party halted one mile north of Kame and settled down for the night. Their position was chosen by Major Scott and units were deployed to prevent any Japanese movement toward Pinlebu from this direction.

At first light on the 6th March, the Sabotage Squad led by Lieutenant Sprague and 16 Platoon set out toward Kame to secure the road block. At about 1100 hours Sprague’s men were attacked by the Japanese from all sides, he called dispersal in an attempt to extract his men, it was here that Lieutenant Callaghan was shot and killed. At 1600 hours the whole column moved away toward the Supply drop rendezvous area.

So as you can see the situation was very confused, with enemy troops engaging the column positions on several occasions during the three day period. It would seem likely that James was a member of Platoon 16 under Lt. Callaghan, as he does not feature in the nominal rolls for Lt. Sprague's commandos.

Another good source of information from this period can be found in the book Wingate Adventure by W.G. Burchett:

As No. 2 Group neared Pinlebu, Gilkes and Brigade HQ moved east to arrange a Supply drop zone, whilst Major Scott’s Column took up defensive positions around Pinlebu. On the 5th March, Scott occupied a village two and a half miles from Pinlebu and sent his patrols out covering all directions. The Japanese were everywhere, but usually betrayed their positions early by blazing away at the slightest movement or noise.

The minor battle lasted all day and into the night, dispersal was then called and the column moved away. Early on the 6th March, Scott set up roadblocks leading east and north out of Pinlebu, the supply drop continued unhindered. Scott had no sooner closed the roadblocks and was preparing to move off, when a Japanese patrol opened fire on one of the furthest placed groups. A brisk thirty-minute battle ensued, leaving six men killed or badly wounded. Column 8 withdrew to safer ground. For the loss of six men the column had held up the enemy for over 24 hours, covering Calvert and Fergusson’s dash to the railway and allowing HQ to secure a vital supply drop.

Sadly, Pte. Walker's body was never recovered after the war and for this reason he is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial in Taukkyan War Cemetery. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this short story including photographs of two other Chindits lost on the Pinlebu/Kame Road. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

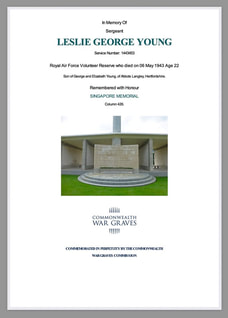

CWGC certificate for Ronald Wallace.

CWGC certificate for Ronald Wallace.

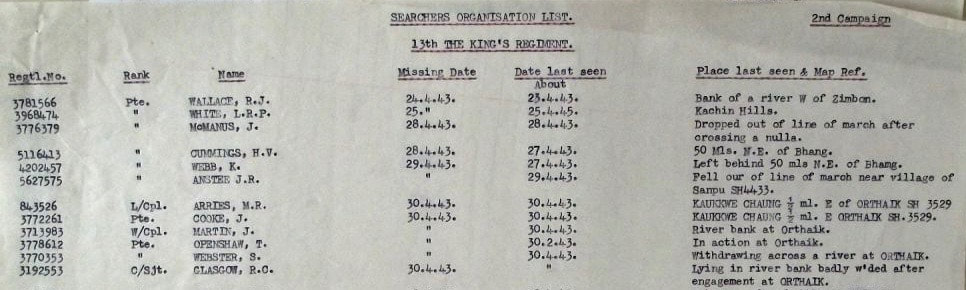

WALLACE, RONALD JOHN

Rank: Private

Service No: 3781566

Date of Death: 24/04/1943

Age: 29

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2528229/wallace,-ronald-john/

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

Pte. Ronald John Wallace was born on the 9th June 1913 and was the son of Joseph George and Alecia Wallace; and the husband of Margaret Wallace from Romiley in Cheshire. He began his Chindit training at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India in late July 1942 and was posted to No. 18 Platoon within 8 Column, under the command of Captain Raymond Edward Williams. This platoon became separated from the main body of 8 Column after approximately six weeks behind enemy lines in Burma.

From the War diary of 8 Column dated 1st April 1943:

Recce of the River Shweli carried out during the afternoon and we have decided to cross this evening near the Wingaba Cliffs, S.N. 2563. Column moved down to the river at dusk. Rope got across the river which was flowing very fast on the near side. Captain Williams with two other officers, Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 British Other Ranks crossed the river to form a bridgehead. The next party under Sgt. Scruton got in to difficulties and drifted away down-stream. Both boats having been lost, the crossing was called off. Captain Williams and his party moved from the far bank at first light for the next agreed rendezvous. The rope across the river was withdrawn.

After an aborted crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March 1943, No. 8 Column led by Major W. P. Scott marched away from the other Chindit columns and headed east towards the Shweli River. As mentioned in the war diary quote above, Captain Williams' platoon were the only section of the column to cross the fast flowing Shweli River on the 1st April. After his group had crossed, a mix up occurred involving the power-rope which the column had secured across the river and no further soldiers could join Captain Williams on the far bank. In the end it was decided that his platoon should continue their march out of India under their own steam.

Captain Williams' platoon, of which Ronald Wallace was a member, suffered great misfortune from that moment on and were ambushed by the Japanese on no fewer than three occasions over the following weeks. Transcribed below, is a witness statement with mention of Pte. Wallace and some of the other men from Captain Williams' platoon during Operation Longcloth. The account, given by Corporal A. McCann, the only man from the unit to return safely to India in 1943, describes the third ambush suffered by the platoon and the subsequent death of Captain Williams.

Ambush on the 23rd April

I was with the above mentioned party under the command of Captain R.E. Williams. We crossed the Irrawaddy at Zinbon on or about the 18th April 1943 and travelled west. On the 23rd April we were on the banks of a river, name unknown (only 20 yards wide) when we were suddenly attacked. I found myself in the river with Captain Williams (afterwards killed). I was wounded whilst in the river but got to the other side. On looking back to the other side of the river I saw most of our men being taken prisoner by a numerically superior force. I saw quite clearly Ptes. Wallace and Satchell and then I collapsed. On regaining consciousness I searched the area but found no trace of any of the above party.

Neither Ronald Wallace or William Satchell, from Clayton in Manchester were ever seen or heard of again. After the war, no graves could be found for these two Chindits and so they are remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: 3781566

Date of Death: 24/04/1943

Age: 29

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2528229/wallace,-ronald-john/

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

Pte. Ronald John Wallace was born on the 9th June 1913 and was the son of Joseph George and Alecia Wallace; and the husband of Margaret Wallace from Romiley in Cheshire. He began his Chindit training at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India in late July 1942 and was posted to No. 18 Platoon within 8 Column, under the command of Captain Raymond Edward Williams. This platoon became separated from the main body of 8 Column after approximately six weeks behind enemy lines in Burma.

From the War diary of 8 Column dated 1st April 1943:

Recce of the River Shweli carried out during the afternoon and we have decided to cross this evening near the Wingaba Cliffs, S.N. 2563. Column moved down to the river at dusk. Rope got across the river which was flowing very fast on the near side. Captain Williams with two other officers, Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 British Other Ranks crossed the river to form a bridgehead. The next party under Sgt. Scruton got in to difficulties and drifted away down-stream. Both boats having been lost, the crossing was called off. Captain Williams and his party moved from the far bank at first light for the next agreed rendezvous. The rope across the river was withdrawn.

After an aborted crossing of the Irrawaddy on the 29th March 1943, No. 8 Column led by Major W. P. Scott marched away from the other Chindit columns and headed east towards the Shweli River. As mentioned in the war diary quote above, Captain Williams' platoon were the only section of the column to cross the fast flowing Shweli River on the 1st April. After his group had crossed, a mix up occurred involving the power-rope which the column had secured across the river and no further soldiers could join Captain Williams on the far bank. In the end it was decided that his platoon should continue their march out of India under their own steam.

Captain Williams' platoon, of which Ronald Wallace was a member, suffered great misfortune from that moment on and were ambushed by the Japanese on no fewer than three occasions over the following weeks. Transcribed below, is a witness statement with mention of Pte. Wallace and some of the other men from Captain Williams' platoon during Operation Longcloth. The account, given by Corporal A. McCann, the only man from the unit to return safely to India in 1943, describes the third ambush suffered by the platoon and the subsequent death of Captain Williams.

Ambush on the 23rd April

I was with the above mentioned party under the command of Captain R.E. Williams. We crossed the Irrawaddy at Zinbon on or about the 18th April 1943 and travelled west. On the 23rd April we were on the banks of a river, name unknown (only 20 yards wide) when we were suddenly attacked. I found myself in the river with Captain Williams (afterwards killed). I was wounded whilst in the river but got to the other side. On looking back to the other side of the river I saw most of our men being taken prisoner by a numerically superior force. I saw quite clearly Ptes. Wallace and Satchell and then I collapsed. On regaining consciousness I searched the area but found no trace of any of the above party.

Neither Ronald Wallace or William Satchell, from Clayton in Manchester were ever seen or heard of again. After the war, no graves could be found for these two Chindits and so they are remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

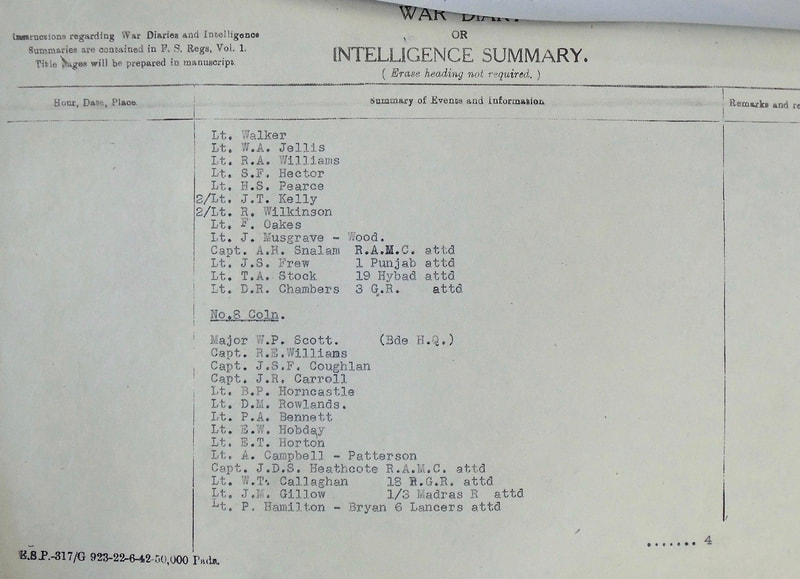

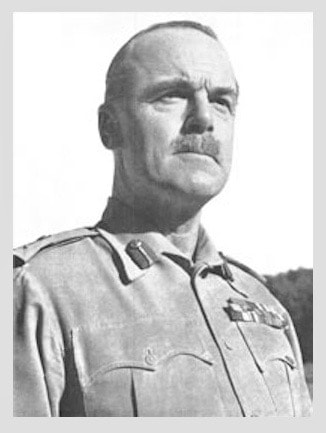

WAUGH, EDWARD RAYMOND

Rank: Captain

Service No: 130975

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

Edward Raymond Waugh was from Manchester and a typical Lancashire man with a warm-hearted nature and a knack of putting everyone he met at ease. His commission as a 2nd Lieutenant into the King's Regiment was announced in the London Gazette on the 31st May 1940 and he had joined the 13th King's while the battalion was stationed in Wales. After travelling with the battalion to India in December 1941, he settled with the King's at Secunderabad. An entry in the battalion war diary dated 3rd April 1942, states that he and another officer, Lt. Summerfield had been chosen to lead a party of 40 men on a training course at Mount Abu in Rajasthan State. Shortly after their return, the battalion was given over to Brigadier Wingate to use in his Long Range Penetration exercises in the Central Provinces of India.

Having performed well during the early weeks of Chindit training, Ted became the obvious choice to lead 5 Column when the King's moved up to Patharia and formed their base in the jungle scrub. Ted was something of a small arms expert in India and would often supplement his column's rations with game that he had shot whilst out on manoeuvres, animals including hare, peacock and monkey were regularly added to the cooking pot. One story, recounted by Lt. Leslie Cottrell, tells of an occasion when Ted shot a snake with his pistol which had reared up on top of a rock about 30 yards from where he stood.

Unfortunately, Captain Waugh became unwell a few months into Chindit training and was ultimately replaced by Bernard Fergusson as No. 5 Column commander on the 17th October 1942. In his book, Return via Rangoon, 5 Column officer Philip Stibbe recalled:

While the column was at Malthone, one change that did effect us all, was the departure of Ted Waugh, which all ranks regretted. George Borrow and I were particularly sorry, as he had been extremely good to us ever since our arrival, but he had been struggling against ill-health and it was clear that he could not go on.

It is not known where Captain Waugh went after leaving Chindit training in October 1942, presumably he joined another unit in India, possibly in an administration role, or perhaps training soldiers in the use of small arms.

In his book, Beyond the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson remembered:

After speaking with Wingate, I went to meet some of my officers who were all very pleasant and the man I had come to replace could not have been kinder. I formed a high opinion of him and at the end of that week asked him to stay on as my second in command. Understandably, he felt his position might be difficult going forward and preferred to go. I am glad we parted the very best of friends.

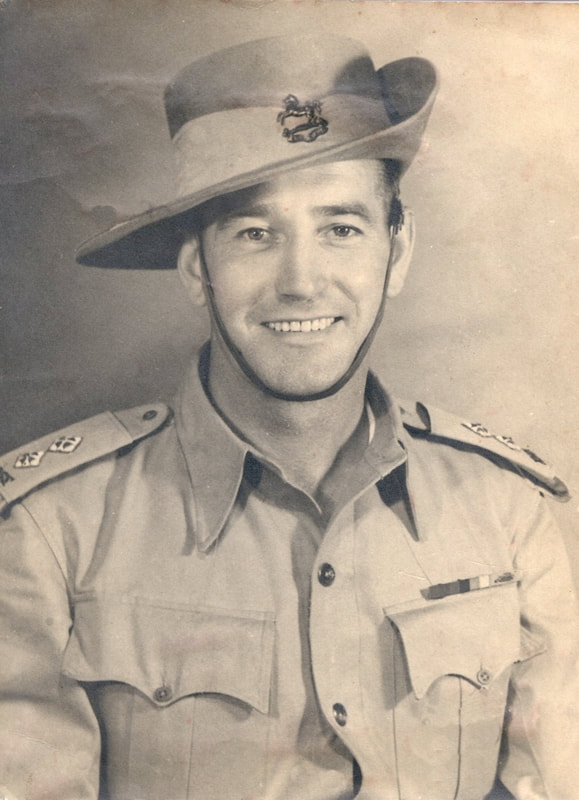

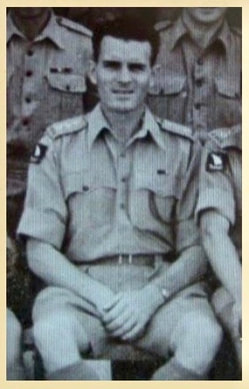

Seen below is a photograph of the officers of the 13th King's, taken at Colchester Army Barracks in 1941. Ted Waugh can be seen in the second row, third from the right as we look. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Captain

Service No: 130975

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Chindit Column: 5

Other details:

Edward Raymond Waugh was from Manchester and a typical Lancashire man with a warm-hearted nature and a knack of putting everyone he met at ease. His commission as a 2nd Lieutenant into the King's Regiment was announced in the London Gazette on the 31st May 1940 and he had joined the 13th King's while the battalion was stationed in Wales. After travelling with the battalion to India in December 1941, he settled with the King's at Secunderabad. An entry in the battalion war diary dated 3rd April 1942, states that he and another officer, Lt. Summerfield had been chosen to lead a party of 40 men on a training course at Mount Abu in Rajasthan State. Shortly after their return, the battalion was given over to Brigadier Wingate to use in his Long Range Penetration exercises in the Central Provinces of India.

Having performed well during the early weeks of Chindit training, Ted became the obvious choice to lead 5 Column when the King's moved up to Patharia and formed their base in the jungle scrub. Ted was something of a small arms expert in India and would often supplement his column's rations with game that he had shot whilst out on manoeuvres, animals including hare, peacock and monkey were regularly added to the cooking pot. One story, recounted by Lt. Leslie Cottrell, tells of an occasion when Ted shot a snake with his pistol which had reared up on top of a rock about 30 yards from where he stood.

Unfortunately, Captain Waugh became unwell a few months into Chindit training and was ultimately replaced by Bernard Fergusson as No. 5 Column commander on the 17th October 1942. In his book, Return via Rangoon, 5 Column officer Philip Stibbe recalled:

While the column was at Malthone, one change that did effect us all, was the departure of Ted Waugh, which all ranks regretted. George Borrow and I were particularly sorry, as he had been extremely good to us ever since our arrival, but he had been struggling against ill-health and it was clear that he could not go on.

It is not known where Captain Waugh went after leaving Chindit training in October 1942, presumably he joined another unit in India, possibly in an administration role, or perhaps training soldiers in the use of small arms.

In his book, Beyond the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson remembered:

After speaking with Wingate, I went to meet some of my officers who were all very pleasant and the man I had come to replace could not have been kinder. I formed a high opinion of him and at the end of that week asked him to stay on as my second in command. Understandably, he felt his position might be difficult going forward and preferred to go. I am glad we parted the very best of friends.

Seen below is a photograph of the officers of the 13th King's, taken at Colchester Army Barracks in 1941. Ted Waugh can be seen in the second row, third from the right as we look. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

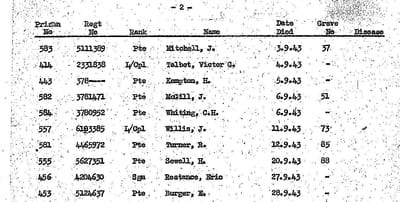

WAYMAN, FREDERICK ERNEST

Rank: Private

Service No: 5827143

Date of Death: 09/04/1943

Age: 23

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

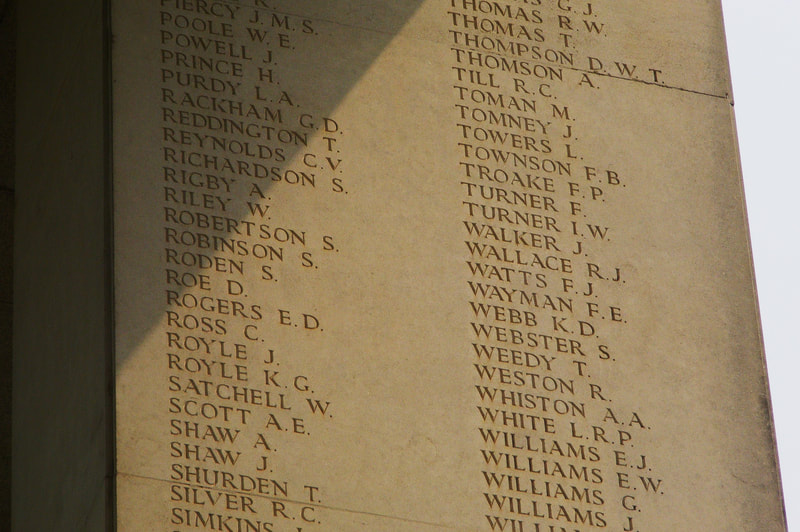

Memorial: Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2528338/frederick-ernest-wayman/

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

Frederick Wayman was the son of Smith and Gladys Wayman of Longstanton in Cambridgeshire. According to his Army service number, he was originally posted to the Suffolk Regiment before being transferred to the 142 Commando Company at Jubbulpore on the 1st July 1942. He was allocated to No. 7 Column on Operation Longcloth, but sadly no documentation exists explaining how Frederick was lost in Burma. The only information comes from the official missing lists for the expedition, stating that he was last seen on the evening of the 8th April 1943, at the Hintha Reserve Forest.

A number of men from No. 7 Column were lost around this time, after Major Gilkes the commanding officer of the column gave the order to break up the unit into smaller dispersal groups. To read more about this time and the dispersal party Frederick Wayman might have been a part of, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

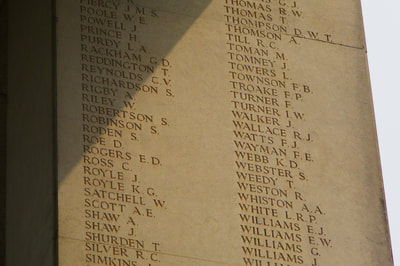

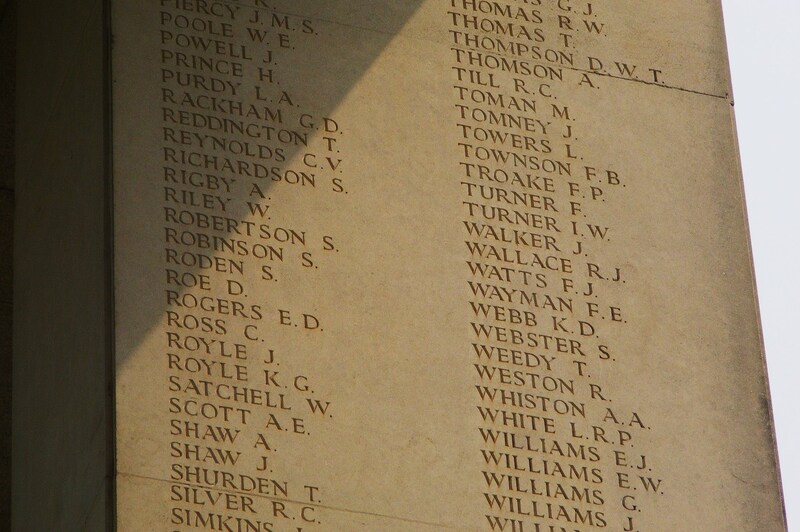

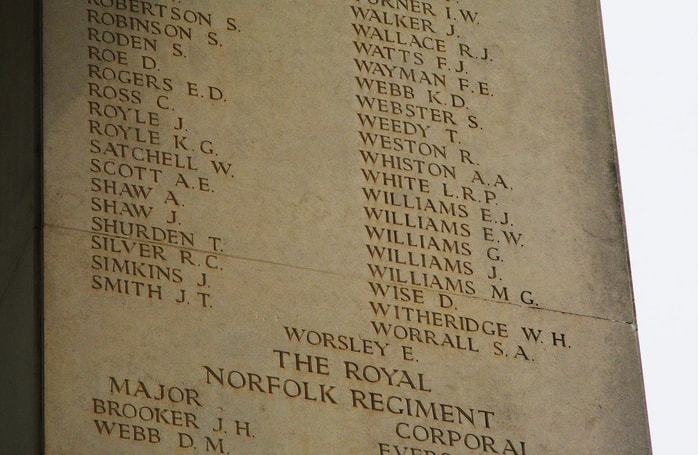

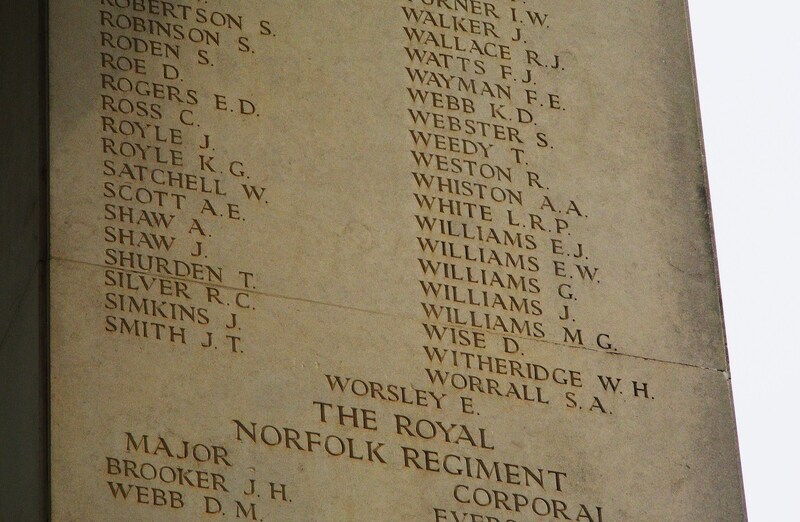

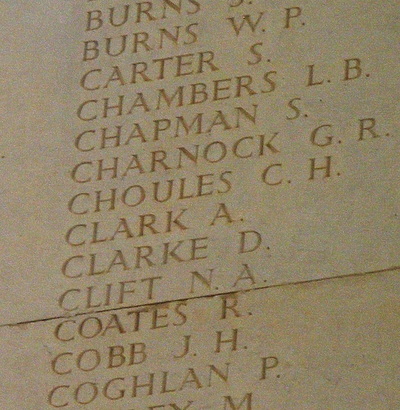

With his missing date recorded as the 9th April, it might well be that Pte. Wayman was already lost to his column, previous to the order to disperse. Sadly, we will probably never know. His grave was never found after the war and for this reason Frederick is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial located at Taukkyan War Cemetery. The memorial is the centre-piece structure at Taukkyan and commemorates the casualties from the Burma campaign that have no known grave. Frederick is also remembered on a stone tablet in All Saints Church at Longstanton alongside three other men from the local area. Seen below is a photograph of Frederick's inscription upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: 5827143

Date of Death: 09/04/1943

Age: 23

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2528338/frederick-ernest-wayman/

Chindit Column: 7

Other details:

Frederick Wayman was the son of Smith and Gladys Wayman of Longstanton in Cambridgeshire. According to his Army service number, he was originally posted to the Suffolk Regiment before being transferred to the 142 Commando Company at Jubbulpore on the 1st July 1942. He was allocated to No. 7 Column on Operation Longcloth, but sadly no documentation exists explaining how Frederick was lost in Burma. The only information comes from the official missing lists for the expedition, stating that he was last seen on the evening of the 8th April 1943, at the Hintha Reserve Forest.

A number of men from No. 7 Column were lost around this time, after Major Gilkes the commanding officer of the column gave the order to break up the unit into smaller dispersal groups. To read more about this time and the dispersal party Frederick Wayman might have been a part of, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

With his missing date recorded as the 9th April, it might well be that Pte. Wayman was already lost to his column, previous to the order to disperse. Sadly, we will probably never know. His grave was never found after the war and for this reason Frederick is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial located at Taukkyan War Cemetery. The memorial is the centre-piece structure at Taukkyan and commemorates the casualties from the Burma campaign that have no known grave. Frederick is also remembered on a stone tablet in All Saints Church at Longstanton alongside three other men from the local area. Seen below is a photograph of Frederick's inscription upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Cap badge of the Gloucestershire Regiment.

Cap badge of the Gloucestershire Regiment.

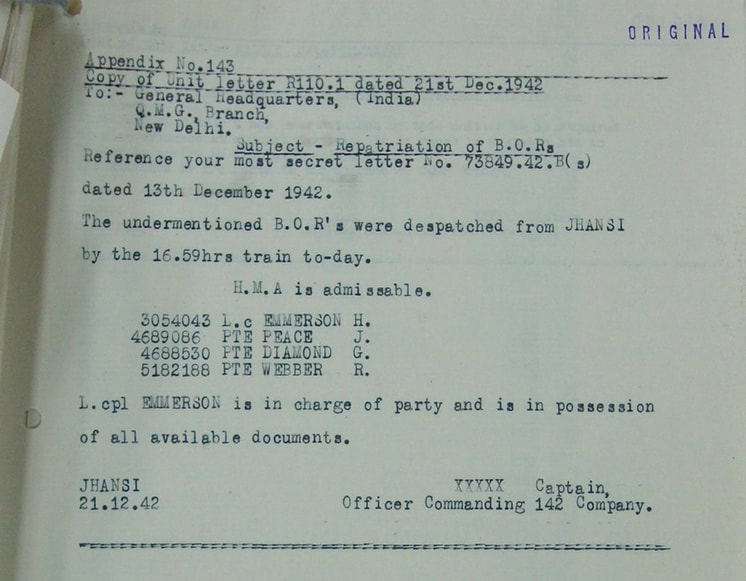

WEBBER, P.

Rank: Private

Service No: 5182188

Regiment/Service: Gloucestershire Regiment attached 142 Commando Company

Chindit Column: N/A

Other details:

Pte. Webber had trained with 142 Commando at the Saugor Camp during the autumn of 1942. It is not known which Chindit column he had been allocated to, but it is known that he had fought with the Gloucestershire Regiment against the Japanese during the retreat from Burma earlier in the year (February/March).

On the 13th December, Pte. Webber, alongside three other men was despatched from the Chindit camp at Jhansi by train to an undisclosed destination, but thought to be Bombay.

The other soldiers were:

Lance Corporal 3054043 H. Emmerson (Royal Scots)

Pte. 4689086 J. Peace

Pte. 4688530 G. Diamond

No other information is available about this movement order and none of the above mentioned men can be confirmed as having served on the first Wingate expedition in Burma. I can say that all three men had served with the 2nd Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry previously and all three had come to 142 Commando via the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo. Seen below is the written order confirming their move from Jhansi dated 13th December 1942. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: 5182188

Regiment/Service: Gloucestershire Regiment attached 142 Commando Company

Chindit Column: N/A

Other details:

Pte. Webber had trained with 142 Commando at the Saugor Camp during the autumn of 1942. It is not known which Chindit column he had been allocated to, but it is known that he had fought with the Gloucestershire Regiment against the Japanese during the retreat from Burma earlier in the year (February/March).

On the 13th December, Pte. Webber, alongside three other men was despatched from the Chindit camp at Jhansi by train to an undisclosed destination, but thought to be Bombay.

The other soldiers were:

Lance Corporal 3054043 H. Emmerson (Royal Scots)

Pte. 4689086 J. Peace

Pte. 4688530 G. Diamond

No other information is available about this movement order and none of the above mentioned men can be confirmed as having served on the first Wingate expedition in Burma. I can say that all three men had served with the 2nd Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry previously and all three had come to 142 Commando via the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo. Seen below is the written order confirming their move from Jhansi dated 13th December 1942. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

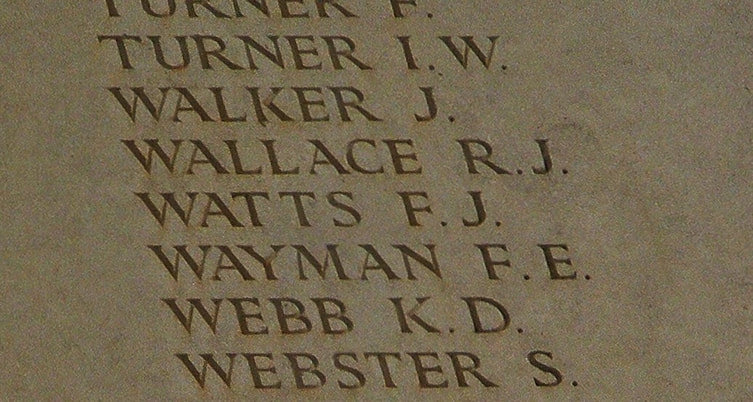

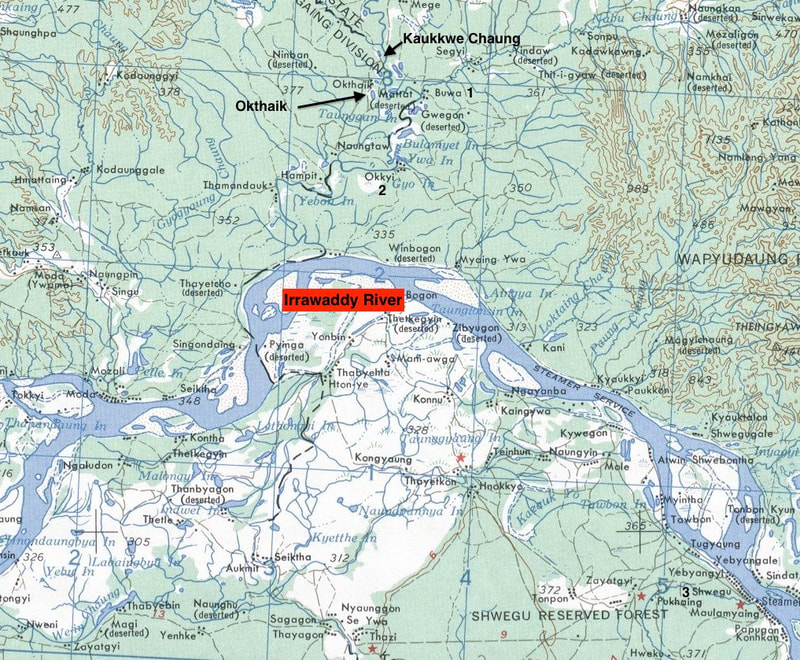

WEBSTER, SAMUEL

Rank: Private

Service No: 3770353

Date of Death: 30/04/1943

Age: 26

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2528375/webster,-samuel/

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

Samuel Webster was the son of Samuel and Mary Ellen Webster from Anthony Street in Liverpool. He enlisted into the British Army and was posted to the 5th Battalion of the King's Regiment, before travelling to India and being transferred to the 13th King's at the Saugor training camp in the Central Provinces of the country. Samuel was then allocated to No. 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott also of the King's Regiment.

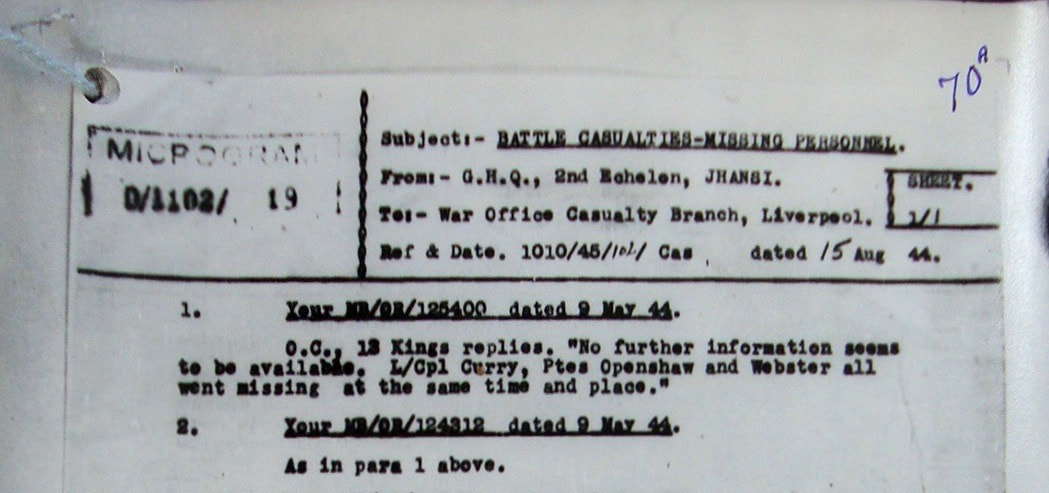

Almost nothing is known about Pte. Webster and his experiences on the first Wingate expedition in 1943. A casualty report comprised on the 9th May 1944 by the Army Investigation Bureau simply states:

Officer commanding 13th King's (Colonel S.A. Cooke) replied that no further information seems to be available for L/Cpl. Curry or Ptes. Oppenshaw and Webster, all went missing at the same time and place.

The inclusion of L/Cpl. Curry's name does give a single clue to the eventual fate of Samuel, as it is known that Curry was killed in action at the Kaukkwe Chaung on the 30th April 1943. No. 8 Column had broken up into smaller dispersal groups in mid-April and were heading back to India at the time of this action against the Japanese. Scott's men were crossing a fast flowing river (Kaukkwe Chaung) near the Burmese village of Okthaik when they were ambushed by a large Japanese patrol. As the non-swimmers were being helped across the water, several of the more experienced NCOs attempted to hold off the enemy with their machine guns and grenades. Sadly, many men were killed or wounded at this engagement. To read more about the incident at the Kaukkwe Chaung, please click on the following link: Frank Lea, Ellis Grundy and the Kaukkwe Chaung

Nothing more was ever seen or heard of Samuel Webster and his grave was never found after the war was over. For this reason he is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial. This memorial is located at Taukkyan War Cemetery located on the northern outskirts of Rangoon city and contains the names of 26,000 casualties from the Burma campaign who possess no known grave.

NB. Although Samuel was certainly a member of the 13th King's and served on Operation Longcloth in 1943, on his CWGC web page (see link above) he is incorrectly listed as being with the 1st Battalion of the King's Regiment in Burma.

Pte. Webster made his Army Will on the 8th September 1939, which states that:

After payment of my just debts and funeral expenses, I leave all my worldly belongings to my mother, Mary Ellen Webster of 90 Anthony Street, Liverpool 5.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a photograph of Samuel's name upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Rank: Private

Service No: 3770353

Date of Death: 30/04/1943

Age: 26

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2528375/webster,-samuel/

Chindit Column: 8

Other details:

Samuel Webster was the son of Samuel and Mary Ellen Webster from Anthony Street in Liverpool. He enlisted into the British Army and was posted to the 5th Battalion of the King's Regiment, before travelling to India and being transferred to the 13th King's at the Saugor training camp in the Central Provinces of the country. Samuel was then allocated to No. 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott also of the King's Regiment.

Almost nothing is known about Pte. Webster and his experiences on the first Wingate expedition in 1943. A casualty report comprised on the 9th May 1944 by the Army Investigation Bureau simply states:

Officer commanding 13th King's (Colonel S.A. Cooke) replied that no further information seems to be available for L/Cpl. Curry or Ptes. Oppenshaw and Webster, all went missing at the same time and place.

The inclusion of L/Cpl. Curry's name does give a single clue to the eventual fate of Samuel, as it is known that Curry was killed in action at the Kaukkwe Chaung on the 30th April 1943. No. 8 Column had broken up into smaller dispersal groups in mid-April and were heading back to India at the time of this action against the Japanese. Scott's men were crossing a fast flowing river (Kaukkwe Chaung) near the Burmese village of Okthaik when they were ambushed by a large Japanese patrol. As the non-swimmers were being helped across the water, several of the more experienced NCOs attempted to hold off the enemy with their machine guns and grenades. Sadly, many men were killed or wounded at this engagement. To read more about the incident at the Kaukkwe Chaung, please click on the following link: Frank Lea, Ellis Grundy and the Kaukkwe Chaung

Nothing more was ever seen or heard of Samuel Webster and his grave was never found after the war was over. For this reason he is remembered upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial. This memorial is located at Taukkyan War Cemetery located on the northern outskirts of Rangoon city and contains the names of 26,000 casualties from the Burma campaign who possess no known grave.

NB. Although Samuel was certainly a member of the 13th King's and served on Operation Longcloth in 1943, on his CWGC web page (see link above) he is incorrectly listed as being with the 1st Battalion of the King's Regiment in Burma.

Pte. Webster made his Army Will on the 8th September 1939, which states that:

After payment of my just debts and funeral expenses, I leave all my worldly belongings to my mother, Mary Ellen Webster of 90 Anthony Street, Liverpool 5.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this story, including a photograph of Samuel's name upon Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

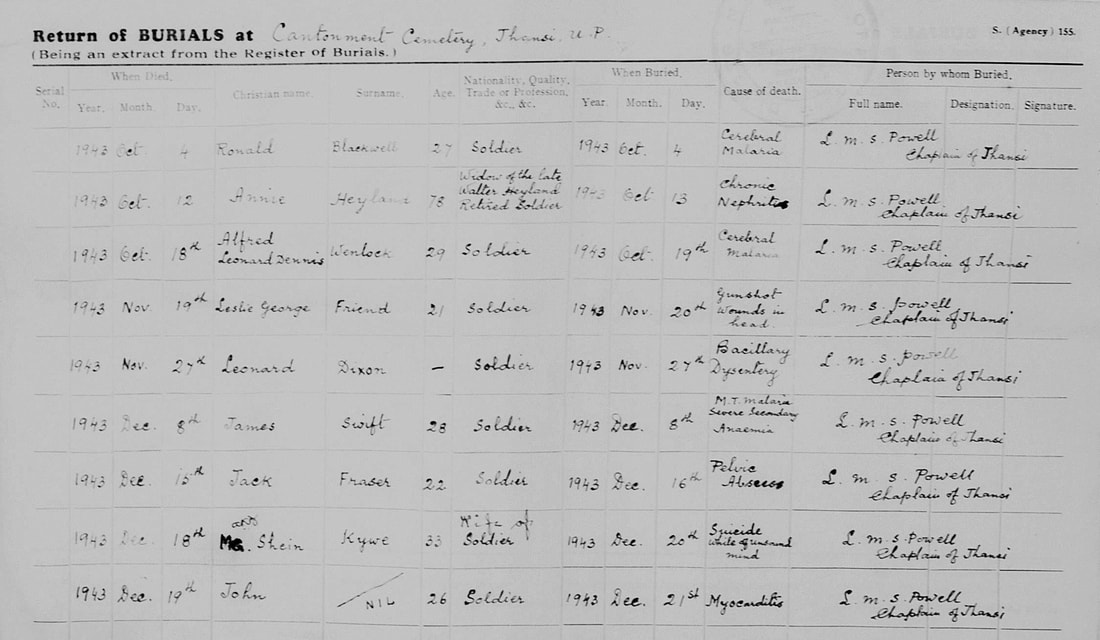

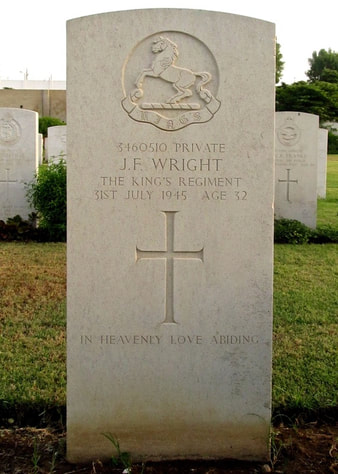

WENLOCK, ALFRED LEONARD DENNIS

Rank: Private

Service No: 4038062

Date of Death: 18/10/1943

Age: 29

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 30th Bn.

Memorial: Grave 3.B.5. Kirkee War Cemetery

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2191274/alfred-leonard-dennis-wenlock/

Chindit Column: Not known

Other details:

Alfred Wedlock was the son of Mr. and Mrs. T. Wedlock from Shrewsbury in Shropshire. According to his Army service number, he had originally enlisted into the King's Shropshire Light Infantry during WW2, before travelling to India and joining the 30th Battalion, the King's Regiment. Alfred's time and service in India is unclear. He appears in my listings for Operation Longcloth on the basis that the recoding of his regiment in India as the 30th King's Liverpool was an error and its was meant to state the 13th Battalion King's Liverpool. At this late stage in proceedings it is unlikely that we will ever know the answer to this question.

What we do know is that Alfred died on the 18th October 1943 at the Jhansi Cantonment in India, suffering from cerebral malaria. It is possible that he may have participated on the first Wingate expedition in Burma and managed to march back to the safety of Allied lines, only to perish from malaria contracted during the operation a few months later. His burial service at Jhansi was conducted by the Chaplain of Jhansi, the Reverend L.M.S. Powell. Alfred was originally buried at the Jhansi Cantonment with his remains later moved to Kirkee War Cemetery after the war.

Seen below is an image of his burial notice, recorded by LMS Powell on the 19th October 1943, the day of Alfred's funeral. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page. Alfred's family were asked to nominate an epitaph for his gravestone at Kirkee War Cemetery and decided upon the following:

Rank: Private

Service No: 4038062

Date of Death: 18/10/1943

Age: 29

Regiment/Service: The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 30th Bn.

Memorial: Grave 3.B.5. Kirkee War Cemetery

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2191274/alfred-leonard-dennis-wenlock/

Chindit Column: Not known

Other details:

Alfred Wedlock was the son of Mr. and Mrs. T. Wedlock from Shrewsbury in Shropshire. According to his Army service number, he had originally enlisted into the King's Shropshire Light Infantry during WW2, before travelling to India and joining the 30th Battalion, the King's Regiment. Alfred's time and service in India is unclear. He appears in my listings for Operation Longcloth on the basis that the recoding of his regiment in India as the 30th King's Liverpool was an error and its was meant to state the 13th Battalion King's Liverpool. At this late stage in proceedings it is unlikely that we will ever know the answer to this question.

What we do know is that Alfred died on the 18th October 1943 at the Jhansi Cantonment in India, suffering from cerebral malaria. It is possible that he may have participated on the first Wingate expedition in Burma and managed to march back to the safety of Allied lines, only to perish from malaria contracted during the operation a few months later. His burial service at Jhansi was conducted by the Chaplain of Jhansi, the Reverend L.M.S. Powell. Alfred was originally buried at the Jhansi Cantonment with his remains later moved to Kirkee War Cemetery after the war.

Seen below is an image of his burial notice, recorded by LMS Powell on the 19th October 1943, the day of Alfred's funeral. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page. Alfred's family were asked to nominate an epitaph for his gravestone at Kirkee War Cemetery and decided upon the following:

In Loving Memory. Sleep On Dear Son, Enjoy Your Rest. God Knows Best.

Cap badge of the Durham Light Infantry.

Cap badge of the Durham Light Infantry.

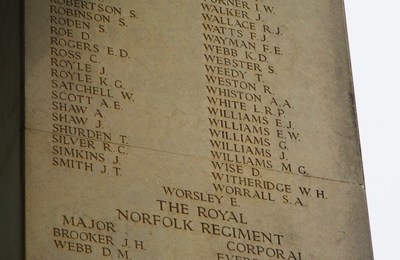

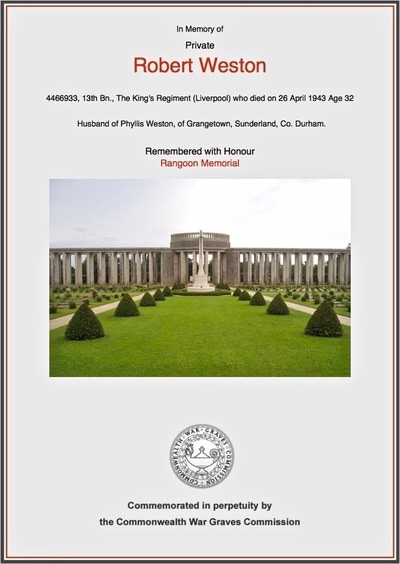

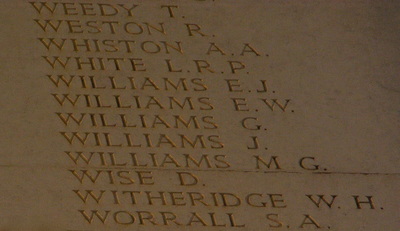

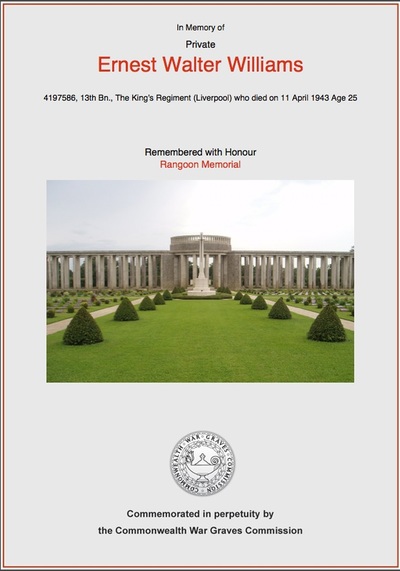

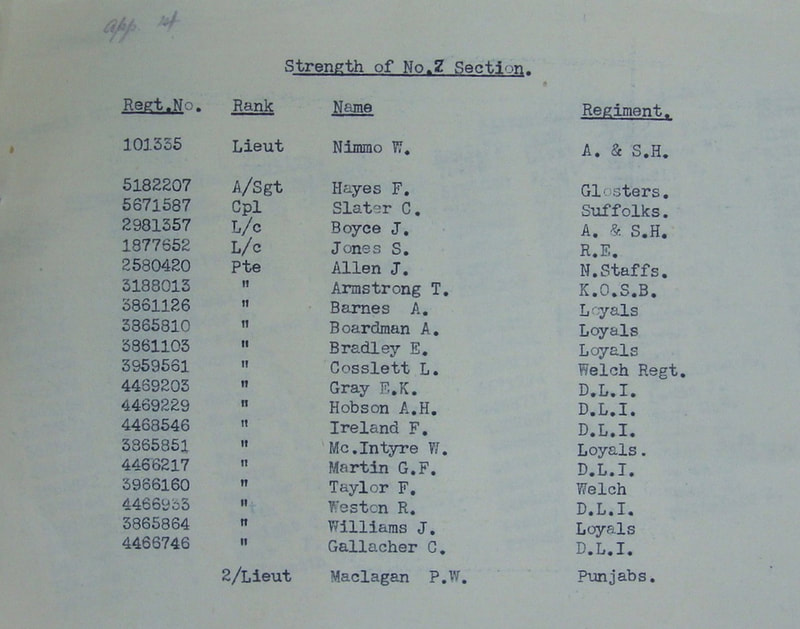

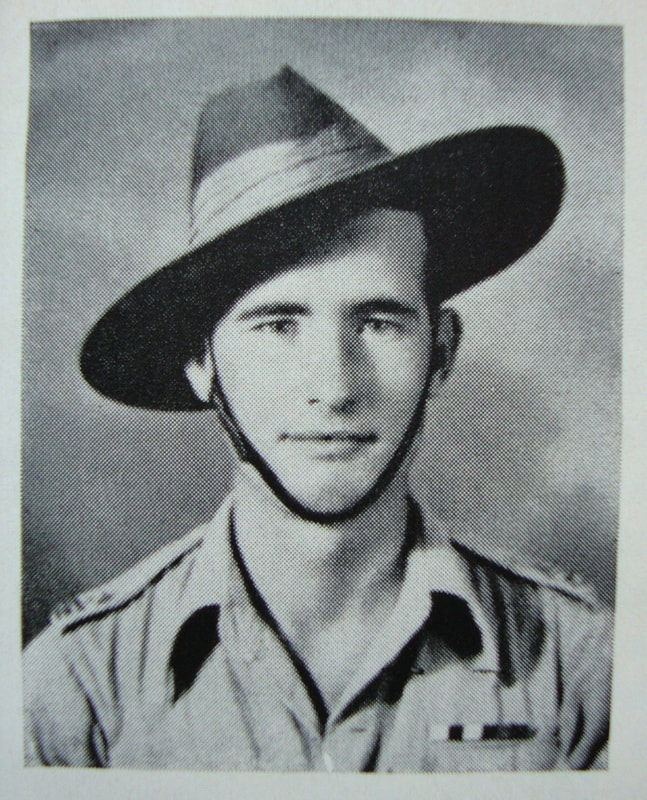

WESTON, ROBERT

Rank: Private

Service No: 4466933

Date of Death: 26/04/1943

Age: 32

Regiment/Service: Durham Light Infantry att. The King's Regiment (Liverpool) 13th Bn.

Memorial: Face 6 of the Rangoon Memorial, Taukkyan War Cemetery.

CWGC link: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2528402/WESTON,%20ROBERT

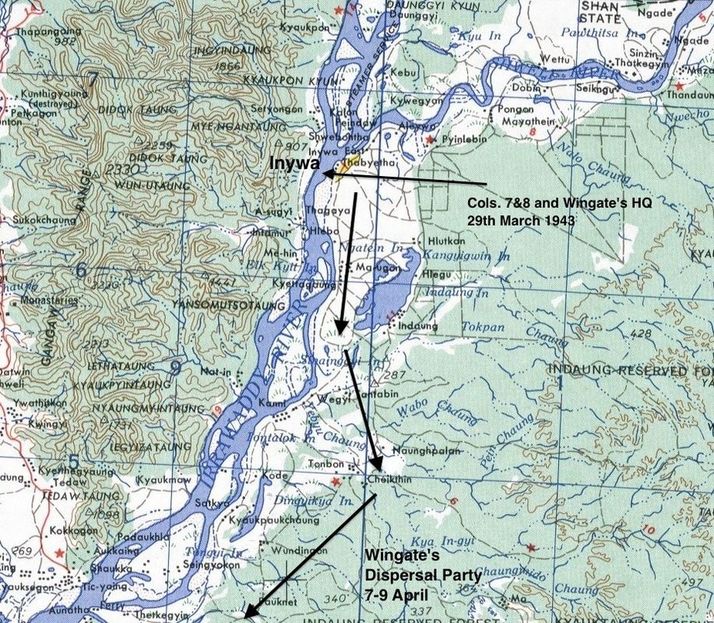

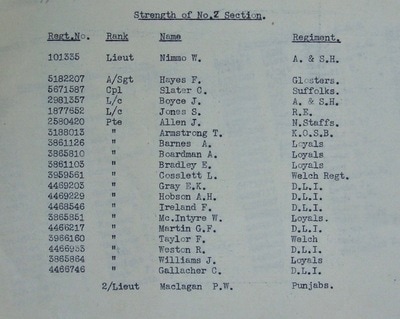

Chindit Column: Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters.

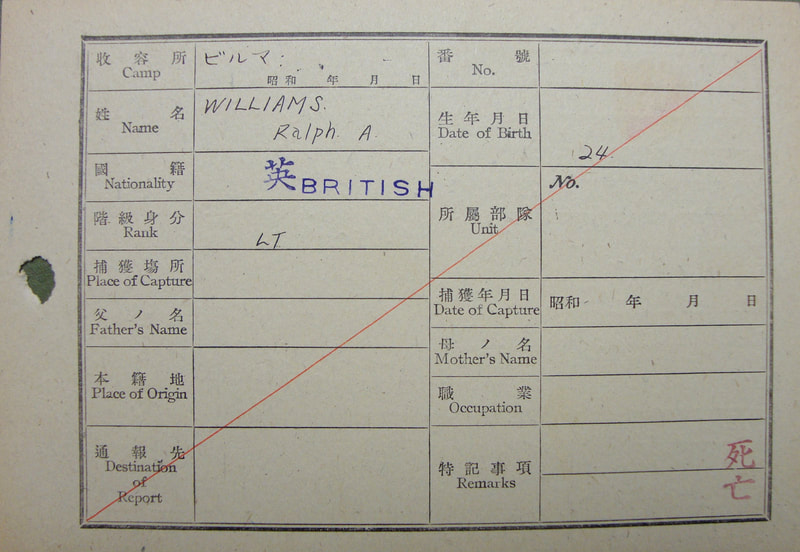

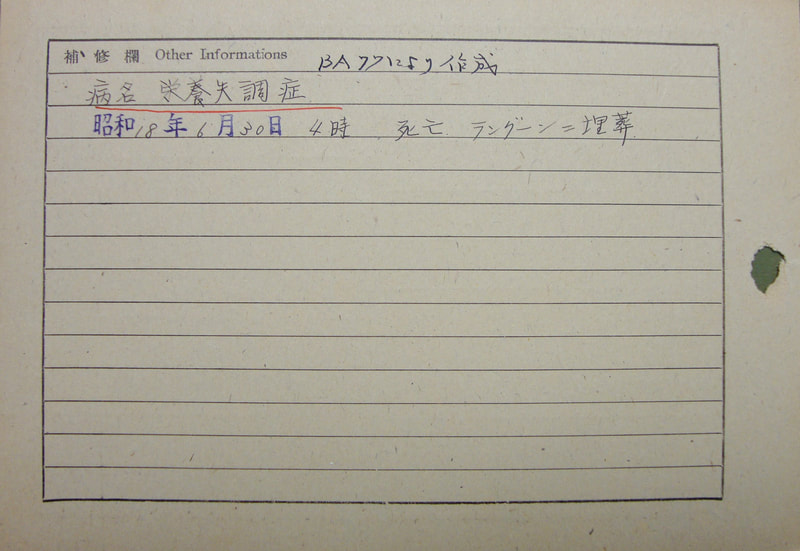

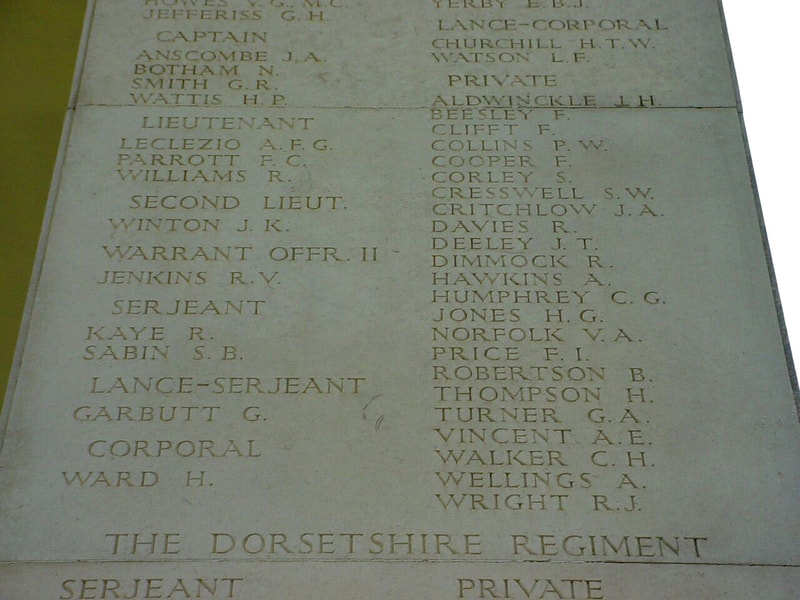

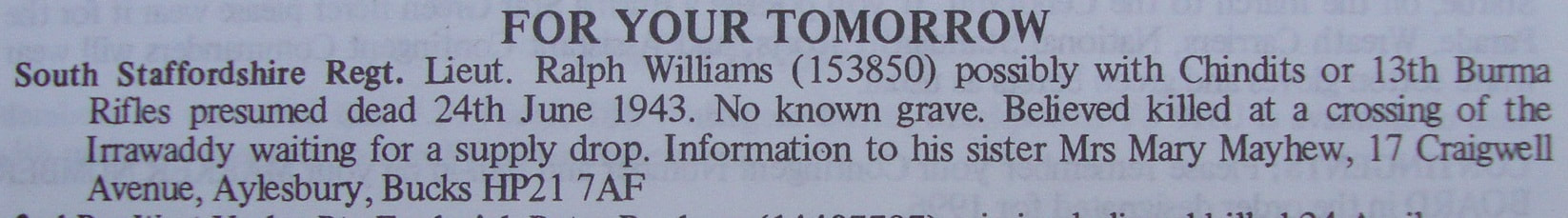

Other details: