Roll Call, the Gurkhas of Operation Longcloth

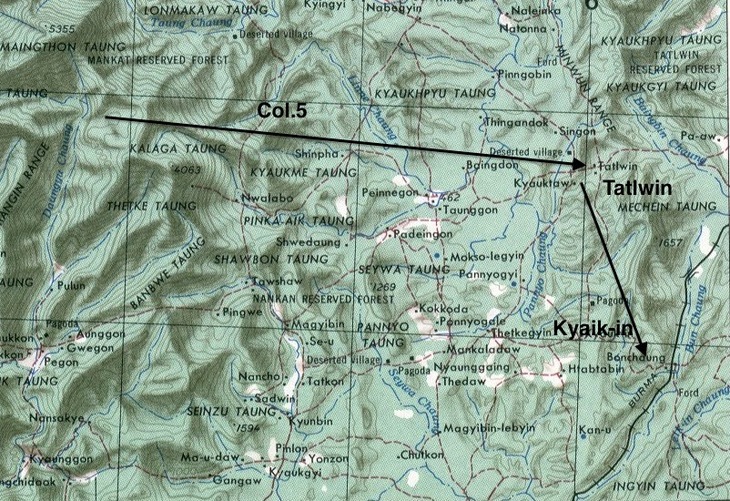

There can be no doubt that the Gurkha sections of 77th Brigade were used by Wingate as a 'feint' to confuse the Japanese about the real route to be taken by and intentions of the Northern Section and their demolition squads. Gurkha Columns 1 and 2 were sent off in a southerly direction as the operation began in February 1943, with the direct instructions to make themselves known to the enemy and the local village spies, as they moved openly toward the rail station at Kyaikthin.

Some commentators have remarked upon the callous nature in which Wingate used the Gurkhas as a diversion and suggested that he would never have dared use the 13th Kings in the same way. There is no doubt that Gurkha casualties were high from these two columns, but when you analyse the overall casualties for the operation, they do not stand out as overly exceptional, with similar numbers of British troops being lost.

The ultimate commitment and bravery of the Gurkha Rifleman on Operation Longcloth cannot be called in to question and the men of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles upheld the traditions of the regiment.

The battalion had left it's Indian base in the early summer of 1942 and joined Chindit training at Saugor. The regimental letter included a short description of the unit and it's new role:

Alexander's Battalion.

News from this Battalion is very scarce. They live in the backwoods and are immersed in the toughest possible training. A route march of 200 miles is a fairly normal occurrence for them. They have no comforts, no homes, no paper and probably no time for writing letters.

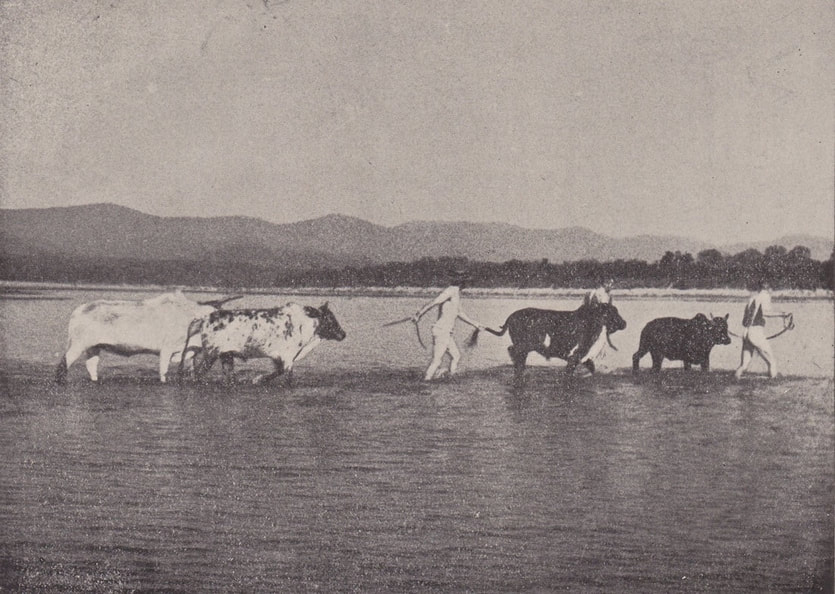

During the recent rains they were overtaken by serious floods and the battalion lost a good deal of its property. This occurred at night and I understand the battalion had to take shelter in the nearby trees. Some of the men did useful rescue work.

After months spent on mechanisation they suddenly lost their vehicles and had to adopt mules. A vast mob of untrained mules, which took some handling and breaking-in. This proved to be a complete reversal of their previous training, but the battalion has got down to it and before long we should be getting some interesting news from them.

Those who cast a gloomy eye on the present physique of Goorkha recruits, should get some comfort from the way the recruits in this battalion are standing up to what is probably the toughest training any battalion has undergone.

General MacDonald who recently saw them at work, was full of praise for these men.

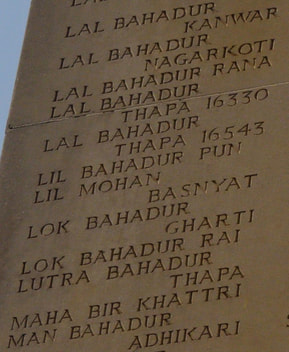

Featured below is my Roll Call for some of the men who made up the strength of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles in 1942/43. I have included all the information that is known about the soldier in question, this could literally be one sentence, but on occasion may well be more substantial in detail. I have chosen to list these men by their given name rather than the clan or tribe he represented.

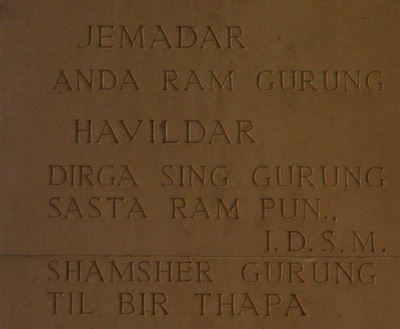

Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung. The junior commander of the Gurkha section led by Captain George Silcock in Column 3. This unsung hero of Mike Calvert's unit led his men with great commitment and passion, gaining the well-meaning nickname of 'Under Arm' from the British Gurkha officers in the column.

Lieutenant Harold James remembered him thus:

"I was glad to be given a decent job and also that 13 Platoon was to be in my charge. The platoon's Gurkha Officer was Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung. He was universally liked and affectionately called 'Under Arm'. Slim, plucky, ugly but with a transforming smile when he laughed, which was very often, he was a man I came to know well and could really trust."

Sadly, having successfully reached the safety of India with Column 3 in April, Anda Ram Gurung succumbed to a severe bout of malaria whilst at home in Nepal and died on 24th June 1943. Here are his CWGC details:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2503458/ANDA%20RAM%20GURUNG

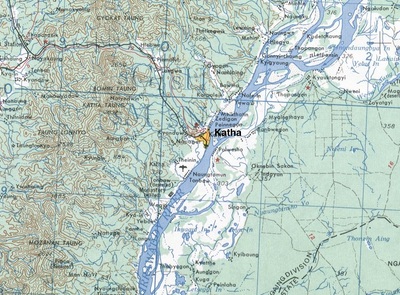

Naik Devsur Ale. This soldier was with Chindit Column 1 on Operation Longcloth. After dispersal was called in late March 1943, Column 1 found themselves further east than any other Chindit unit, their journey home would be long and arduous. Around the third week in April, the Column attempted to cross the Irrawaddy River near a village called Singyat.

Naik Devsur Ale was given the task of setting up a rearguard position to protect the men as they crossed. Subedar-Major Siblal Thapa recalled:

"The last boat with Naik Devsur Ale's platoon was only about 50 yards from our side of the river when we were attacked from all angles. The enemy fired on the boats; the only survivors were Devsur and one other Rifleman. A few men from that last platoon were left on the far side with Subedar Padanbahadur's party and did not cross the river that day."

I do not possess any more information about Devsur Ale, but it seems likely that he returned safely to India in 1943.

Naik Harka Bahadur. This NCO originally came from the 10th Gurkha Rifles as part of a draft of men sent to serve as muleteers on Operation Longcloth. He was posted to Column 8 and served under Lieutenant Dominic Fitzgerald Neill whilst in Burma. After dispersal was called in late March 1943, Lieutenant Neill and his Gurkhas made their way out westward towards India. Their journey was long and tortuous and on more than one occasion they had to fight off enemy attacks.

As they approached the final few miles of their journey back to the Chindwin River, Harka Bahadur fell ill, suffering from malaria and exhaustion. It is suggested that he may not have made it back to India and died from his illness on 15 May 1943. However, I cannot find any details for his death on the CWGC website and there is no record of his demise within Lieutenant Neill's memoir, 'One More River'. I sincerely hope that Naik Harka Bahadur made it safely home to Nepal in 1943 and went on to enjoy a long and prosperous life.

Havildar Budhiman. This Gurkha soldier was also part of Lieutenant Neill's Animal Transport Platoon in Column 8, in fact he was Neill's trusted right hand during the operation in 1943. Budhiman safely re-crossed the Chindwin River in early June 1943, leading the sick and wounded over in the first boat at the village of Sahpa, close to the town of Meine.

Here are some images relating to the above section of Gurkha stories, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Some commentators have remarked upon the callous nature in which Wingate used the Gurkhas as a diversion and suggested that he would never have dared use the 13th Kings in the same way. There is no doubt that Gurkha casualties were high from these two columns, but when you analyse the overall casualties for the operation, they do not stand out as overly exceptional, with similar numbers of British troops being lost.

The ultimate commitment and bravery of the Gurkha Rifleman on Operation Longcloth cannot be called in to question and the men of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles upheld the traditions of the regiment.

The battalion had left it's Indian base in the early summer of 1942 and joined Chindit training at Saugor. The regimental letter included a short description of the unit and it's new role:

Alexander's Battalion.

News from this Battalion is very scarce. They live in the backwoods and are immersed in the toughest possible training. A route march of 200 miles is a fairly normal occurrence for them. They have no comforts, no homes, no paper and probably no time for writing letters.

During the recent rains they were overtaken by serious floods and the battalion lost a good deal of its property. This occurred at night and I understand the battalion had to take shelter in the nearby trees. Some of the men did useful rescue work.

After months spent on mechanisation they suddenly lost their vehicles and had to adopt mules. A vast mob of untrained mules, which took some handling and breaking-in. This proved to be a complete reversal of their previous training, but the battalion has got down to it and before long we should be getting some interesting news from them.

Those who cast a gloomy eye on the present physique of Goorkha recruits, should get some comfort from the way the recruits in this battalion are standing up to what is probably the toughest training any battalion has undergone.

General MacDonald who recently saw them at work, was full of praise for these men.

Featured below is my Roll Call for some of the men who made up the strength of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles in 1942/43. I have included all the information that is known about the soldier in question, this could literally be one sentence, but on occasion may well be more substantial in detail. I have chosen to list these men by their given name rather than the clan or tribe he represented.

Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung. The junior commander of the Gurkha section led by Captain George Silcock in Column 3. This unsung hero of Mike Calvert's unit led his men with great commitment and passion, gaining the well-meaning nickname of 'Under Arm' from the British Gurkha officers in the column.

Lieutenant Harold James remembered him thus:

"I was glad to be given a decent job and also that 13 Platoon was to be in my charge. The platoon's Gurkha Officer was Jemadar Anda Ram Gurung. He was universally liked and affectionately called 'Under Arm'. Slim, plucky, ugly but with a transforming smile when he laughed, which was very often, he was a man I came to know well and could really trust."

Sadly, having successfully reached the safety of India with Column 3 in April, Anda Ram Gurung succumbed to a severe bout of malaria whilst at home in Nepal and died on 24th June 1943. Here are his CWGC details:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2503458/ANDA%20RAM%20GURUNG

Naik Devsur Ale. This soldier was with Chindit Column 1 on Operation Longcloth. After dispersal was called in late March 1943, Column 1 found themselves further east than any other Chindit unit, their journey home would be long and arduous. Around the third week in April, the Column attempted to cross the Irrawaddy River near a village called Singyat.

Naik Devsur Ale was given the task of setting up a rearguard position to protect the men as they crossed. Subedar-Major Siblal Thapa recalled:

"The last boat with Naik Devsur Ale's platoon was only about 50 yards from our side of the river when we were attacked from all angles. The enemy fired on the boats; the only survivors were Devsur and one other Rifleman. A few men from that last platoon were left on the far side with Subedar Padanbahadur's party and did not cross the river that day."

I do not possess any more information about Devsur Ale, but it seems likely that he returned safely to India in 1943.

Naik Harka Bahadur. This NCO originally came from the 10th Gurkha Rifles as part of a draft of men sent to serve as muleteers on Operation Longcloth. He was posted to Column 8 and served under Lieutenant Dominic Fitzgerald Neill whilst in Burma. After dispersal was called in late March 1943, Lieutenant Neill and his Gurkhas made their way out westward towards India. Their journey was long and tortuous and on more than one occasion they had to fight off enemy attacks.

As they approached the final few miles of their journey back to the Chindwin River, Harka Bahadur fell ill, suffering from malaria and exhaustion. It is suggested that he may not have made it back to India and died from his illness on 15 May 1943. However, I cannot find any details for his death on the CWGC website and there is no record of his demise within Lieutenant Neill's memoir, 'One More River'. I sincerely hope that Naik Harka Bahadur made it safely home to Nepal in 1943 and went on to enjoy a long and prosperous life.

Havildar Budhiman. This Gurkha soldier was also part of Lieutenant Neill's Animal Transport Platoon in Column 8, in fact he was Neill's trusted right hand during the operation in 1943. Budhiman safely re-crossed the Chindwin River in early June 1943, leading the sick and wounded over in the first boat at the village of Sahpa, close to the town of Meine.

Here are some images relating to the above section of Gurkha stories, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

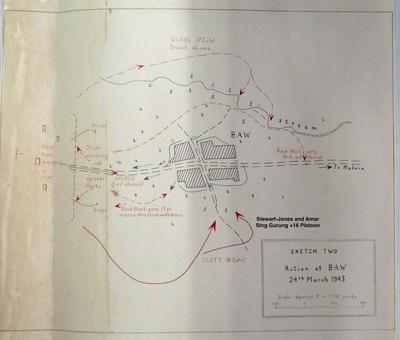

Subedar Kumba Sing Gurung IDSM. Kumba Sing was the senior Gurkha Officer in Column 3. Lieutenant Harold James described him as, "a short but broad-shouldered man, keen on smart appearance and self-discipline, he was a perfect soldier." The Subedar not only took care of the young Gurkha Riflemen from Column 3 in 1943, but the young British subalterns too.

At the battle of Nankan, Mike Calvert placed Kumba Sing in charge of blocking the main road into the rail station whilst the demolition squad went about their business. The Subedar succeeded in holding off a large patrol of Japanese for several hours and was rewarded for his endeavours with the award of an Indian Distinguished Service Medal.

After dispersal was called in late March, Calvert gave one of the dispersal parties to Kumba Sing to lead, he achieved his objective and led the group out of Burma and into the Chinese Yunnan Borders and eventual safety.

Here is the recommendation for Kumba Sing Gurung's IDSM, as put forward by Major Calvert in August 1943:

On 6th March 1943, at NANKAN Railway Station, Subadar KUM SING was detached with one section and an anti tank rifle to guard a track while demolitions were being carried out on the railway. Two lorry loads of Japanese infantry arrived and drove straight into the ambush which he had laid. The majority were killed at the outset, but the remainder were reinforced. Subadar KUM SING continued to fight the enemy for two hours, gaining complete immunity from interruption for the parties engaged in demolishing the railway. He himself shot two of the enemy, on whom 15 casualties were inflicted without loss to our own troops. During the whole of the campaign as Senior Gurkha Officer with his column he maintained the morale and discipline of his men under trying circumstances and upheld the finest tradition of the Gurkha Officer.

Naik Premsingh Gurung. The account of Premsingh Gurung's time in Burma is perhaps one of the saddest and most touching stories from Operation Longcloth. The young Gurkha NCO was a member of Column 2 in 1943 and took up the post of machine-gunner in a platoon commanded by Lieutenant Ian MacHorton. Column 2 had a difficult time in Burma and disaster befell them on the 2nd March at the railway station town of Kyaikthin, where they were ambushed by a large Japanese force.

MacHorton described the fierce nature of that battle in his book, 'Safer than a Known Way'.

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel".

After the guns fell silent that night MacHorton took stock of his situation and found he was alone with a small group of Gurkha Riflemen, one of which was Naik Premsingh Gurung. The brave Naik (Corporal) was seriously wounded and could not walk unaided. On closer inspection it was realised that his thigh bone had been badly smashed and the flesh around the wound burnt by the bullets entry into his leg. MacHorton ordered the group to retire to a small copse on top of hillock just a few yards or so from the railway.

After dressing Premsingh's leg and placing splints in support, the group settled down for the night, always wondering when the enemy might pay them an unwelcome visit. At dawn the men prepared to move out, MacHorton had decided during the night to attempt to make the previously arranged dispersal rendezvous by heading east towards the Irrawaddy River. MacHorton then remembered Premsingh's condition and knew the young Naik would never be able to make the trek to the Irrawaddy, he would have to be left behind.

I will let Lieutenant MacHorton tell the rest of this sorrowful story:

"My mind was made up now. The way ahead was clear. I would lead my little party to the rendezvous and join up with the rest of the survivors from the ambush. I stood up to call the others to their feet. It was good to be on our way again.

But was not there something else, something unpleasant, before I gave the order? Yes. There was the problem of Naik Premsingh to solve. I realised it with a sinking of spirits. I knew all too well what I had to do about Premsingh, but with someone as close as he had become during our weeks behind the Jap lines it was going to be hard.

Premsingh Gurung had come into my life as one of the Gurkhas in the same unspecified "special operation" that I volunteered for. He was from a Nepalese village on the northern slopes of the Himalayas, and his father before him had fought for the British Raj. He never had more than one ambition in life, and that was to be a soldier like his father.

As soon as he attained enlisting age (it is quite customary for the Gurkhas boys to add a year or so and join up at sixteen), he had left his village and gone to the Headquarters of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles. There he had proved himself a willing learner and was soon a tough and competent soldier.

Then he had joined the 3rd Battalion 2nd Gurkha Rifles which formed part of the 77th Independent Infantry Brigade and was sent on a machine-gun course. He came back with an excellent report and the two stripes of a Naik. Naik Premsingh was a machine-gun No.1 under my command when Brigadier Orde Wingate gave the orders for his force to set out and led them into the dangerous unknown of the Japanese-dominated jungle of Burma. And as a machine-gun No.1 he had acquitted himself stoutly at the battle of Kyaikthin.

There was no likelihood of him being able to walk before undergoing an operation and a prolonged stay in hospital. Naik Premsingh knew as well as did I, and every other Chindit, that unless a man could walk unaided he had to be left. The compassion I felt for Premsingh flooded irresistibly to my eyes and as the tears welled from mine I was conscious of the resolution hardening in his. Revulsion at the order I knew I had to give rose like bile in my throat.

Naik Premsingh Gurung, who needed only hospital treatment to restore him to full physical fighting fitness, had to be left to die at this nameless spot in this Burmese jungle. He must die because twelve lives must not be jeopardised for one. I crossed over to Premsingh and knelt beside him. I placed my hand on his arm and squeezed it hard. Feelings just could not be expressed in words. The heart of his friend was full of a yearning to save him, through thick and through thin to strive to get him back to the British lines and certain salvation. But the heart of his Commanding Officer, which was one and the same, was too well aware of the dictates of duty.

No words passed between us as I knelt there. But in that silence he knew that I, his senior by barely two years, was sentencing him to death. His eyes still holding mine, his tightly compressed lips relaxed. The shadow of a smile played around the corners of his mouth. By now the rest were standing up and adjusting their packs ready to move. I sensed they were well aware of the agony of the moment, but rightly turned their backs on it.

I squeezed Premsingh's arm again. Then I stood up. "Carry Naik Premsingh over to the railway," I ordered. "Sahib, no! May I remain here?" He smiled up at me winningly. I decided that maybe Premsingh was right. It was shadier beneath the mighty teak trees which towered majestically over the undergrowth where he lay. From here he had a commanding view and would be able to attract the attention of any passing Burmese who might turn out to be friendly. They might hide him in a village until the broken bone had knit and he was strong enough to escape back through the jungle to the British lines. Any slender chance of survival was preferable to capture by the Japs, inevitable if he were left beside the Japanese-patrolled railway.

"All right, Premsingh," I said. "Just as you like." Premsingh reached out his hand towards his tommy-gun and held it up for Kulbahadur Thapa to take. "Give me your rifle," he said softly. "You take this. It will be more useful to you." Dispassionately the two Gurkhas exchanged weapons.

Then Premsingh looked up towards me again. Now there was an almost tender look in those usually inscrutable eyes. Again that little whimsical playing around the corners of his mouth. "Goodbye, Sahib," he said softly. Our hands met in a firm clasp. Then I turned abruptly and led my men down the scrubby hillside through the undergrowth into the dried-up chaung at its foot. My eyes were hot with unshed tears. From behind us came the sound of a single shot. Naik Premsingh Gurung had been the bravest of the brave."

At the battle of Nankan, Mike Calvert placed Kumba Sing in charge of blocking the main road into the rail station whilst the demolition squad went about their business. The Subedar succeeded in holding off a large patrol of Japanese for several hours and was rewarded for his endeavours with the award of an Indian Distinguished Service Medal.

After dispersal was called in late March, Calvert gave one of the dispersal parties to Kumba Sing to lead, he achieved his objective and led the group out of Burma and into the Chinese Yunnan Borders and eventual safety.

Here is the recommendation for Kumba Sing Gurung's IDSM, as put forward by Major Calvert in August 1943:

On 6th March 1943, at NANKAN Railway Station, Subadar KUM SING was detached with one section and an anti tank rifle to guard a track while demolitions were being carried out on the railway. Two lorry loads of Japanese infantry arrived and drove straight into the ambush which he had laid. The majority were killed at the outset, but the remainder were reinforced. Subadar KUM SING continued to fight the enemy for two hours, gaining complete immunity from interruption for the parties engaged in demolishing the railway. He himself shot two of the enemy, on whom 15 casualties were inflicted without loss to our own troops. During the whole of the campaign as Senior Gurkha Officer with his column he maintained the morale and discipline of his men under trying circumstances and upheld the finest tradition of the Gurkha Officer.

Naik Premsingh Gurung. The account of Premsingh Gurung's time in Burma is perhaps one of the saddest and most touching stories from Operation Longcloth. The young Gurkha NCO was a member of Column 2 in 1943 and took up the post of machine-gunner in a platoon commanded by Lieutenant Ian MacHorton. Column 2 had a difficult time in Burma and disaster befell them on the 2nd March at the railway station town of Kyaikthin, where they were ambushed by a large Japanese force.

MacHorton described the fierce nature of that battle in his book, 'Safer than a Known Way'.

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel".

After the guns fell silent that night MacHorton took stock of his situation and found he was alone with a small group of Gurkha Riflemen, one of which was Naik Premsingh Gurung. The brave Naik (Corporal) was seriously wounded and could not walk unaided. On closer inspection it was realised that his thigh bone had been badly smashed and the flesh around the wound burnt by the bullets entry into his leg. MacHorton ordered the group to retire to a small copse on top of hillock just a few yards or so from the railway.

After dressing Premsingh's leg and placing splints in support, the group settled down for the night, always wondering when the enemy might pay them an unwelcome visit. At dawn the men prepared to move out, MacHorton had decided during the night to attempt to make the previously arranged dispersal rendezvous by heading east towards the Irrawaddy River. MacHorton then remembered Premsingh's condition and knew the young Naik would never be able to make the trek to the Irrawaddy, he would have to be left behind.

I will let Lieutenant MacHorton tell the rest of this sorrowful story:

"My mind was made up now. The way ahead was clear. I would lead my little party to the rendezvous and join up with the rest of the survivors from the ambush. I stood up to call the others to their feet. It was good to be on our way again.

But was not there something else, something unpleasant, before I gave the order? Yes. There was the problem of Naik Premsingh to solve. I realised it with a sinking of spirits. I knew all too well what I had to do about Premsingh, but with someone as close as he had become during our weeks behind the Jap lines it was going to be hard.

Premsingh Gurung had come into my life as one of the Gurkhas in the same unspecified "special operation" that I volunteered for. He was from a Nepalese village on the northern slopes of the Himalayas, and his father before him had fought for the British Raj. He never had more than one ambition in life, and that was to be a soldier like his father.

As soon as he attained enlisting age (it is quite customary for the Gurkhas boys to add a year or so and join up at sixteen), he had left his village and gone to the Headquarters of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles. There he had proved himself a willing learner and was soon a tough and competent soldier.

Then he had joined the 3rd Battalion 2nd Gurkha Rifles which formed part of the 77th Independent Infantry Brigade and was sent on a machine-gun course. He came back with an excellent report and the two stripes of a Naik. Naik Premsingh was a machine-gun No.1 under my command when Brigadier Orde Wingate gave the orders for his force to set out and led them into the dangerous unknown of the Japanese-dominated jungle of Burma. And as a machine-gun No.1 he had acquitted himself stoutly at the battle of Kyaikthin.

There was no likelihood of him being able to walk before undergoing an operation and a prolonged stay in hospital. Naik Premsingh knew as well as did I, and every other Chindit, that unless a man could walk unaided he had to be left. The compassion I felt for Premsingh flooded irresistibly to my eyes and as the tears welled from mine I was conscious of the resolution hardening in his. Revulsion at the order I knew I had to give rose like bile in my throat.

Naik Premsingh Gurung, who needed only hospital treatment to restore him to full physical fighting fitness, had to be left to die at this nameless spot in this Burmese jungle. He must die because twelve lives must not be jeopardised for one. I crossed over to Premsingh and knelt beside him. I placed my hand on his arm and squeezed it hard. Feelings just could not be expressed in words. The heart of his friend was full of a yearning to save him, through thick and through thin to strive to get him back to the British lines and certain salvation. But the heart of his Commanding Officer, which was one and the same, was too well aware of the dictates of duty.

No words passed between us as I knelt there. But in that silence he knew that I, his senior by barely two years, was sentencing him to death. His eyes still holding mine, his tightly compressed lips relaxed. The shadow of a smile played around the corners of his mouth. By now the rest were standing up and adjusting their packs ready to move. I sensed they were well aware of the agony of the moment, but rightly turned their backs on it.

I squeezed Premsingh's arm again. Then I stood up. "Carry Naik Premsingh over to the railway," I ordered. "Sahib, no! May I remain here?" He smiled up at me winningly. I decided that maybe Premsingh was right. It was shadier beneath the mighty teak trees which towered majestically over the undergrowth where he lay. From here he had a commanding view and would be able to attract the attention of any passing Burmese who might turn out to be friendly. They might hide him in a village until the broken bone had knit and he was strong enough to escape back through the jungle to the British lines. Any slender chance of survival was preferable to capture by the Japs, inevitable if he were left beside the Japanese-patrolled railway.

"All right, Premsingh," I said. "Just as you like." Premsingh reached out his hand towards his tommy-gun and held it up for Kulbahadur Thapa to take. "Give me your rifle," he said softly. "You take this. It will be more useful to you." Dispassionately the two Gurkhas exchanged weapons.

Then Premsingh looked up towards me again. Now there was an almost tender look in those usually inscrutable eyes. Again that little whimsical playing around the corners of his mouth. "Goodbye, Sahib," he said softly. Our hands met in a firm clasp. Then I turned abruptly and led my men down the scrubby hillside through the undergrowth into the dried-up chaung at its foot. My eyes were hot with unshed tears. From behind us came the sound of a single shot. Naik Premsingh Gurung had been the bravest of the brave."

Indian Order of Merit (2nd Class).

Indian Order of Merit (2nd Class).

Jemadar Man Bahadur Gurung IOM. The untried junior officer walked slowly along the rail tracks, looking occasionally at the night sky above he wondered what adventures lay ahead for him during his time behind enemy lines in Burma. He did not have to wait long as within seconds the quiet Burmese evening was turned into a chaotic inferno, as a Japanese ambush engulfed the unsuspecting Chindits of Column 2.

Acting on instinct Man Bahadur dropped down into the gravel embankment and drew his rifle forward in front of him, he called out to his platoon to do the same. Unbeknown to the Chindit column, over 800 Japanese troops had made their way up to Kyaikthin village during the day and had lay in wait for them for the last few hours. Now the Japanese attacked the Gurkhas with everything they possessed and succeeded in cutting the column down into small and disjointed units of men.

A British officer called for dispersal and the signal was given, for those who could hear and understand the instruction it had not come a moment too soon and they melted away into the nearby scrubland and headed east. Column commander Major Emmett had pre-arranged a rendezvous a few miles further east, this was set out specifically for such events as an ambush, but the Japanese had surprised the young Gurkha unit and confusion got the better of them that night.

Jemadar Man Bahadur Gurung and some of his platoon had managed to hold their small position and this had allowed many of the muleteers and other personnel to withdraw into the jungle. He now called to his men to do the same.

Once they had moved a sensible distance away from the chaos of the embankment Man Bahadur took time to assess the condition of his platoon. He found that they had faired reasonably well considering the circumstances of the engagement. The platoon was still in good fighting order, although it had lost two of it's best Riflemen in the form of Man Bir Bura and Man Bahadur Tamang. These losses saddened the young Jemadar as he reflected on his own performance that night.

Here is how the senior commander of column 2, Major A. Emmett recounted Man Bahadur's performance on the 2nd March 1943, shown in the form of his recommendation citation for the Indian Order of Merit (2nd Class), which was awarded to the young Jemadar that year:

For I.O. 1132 Jemadar Man Bahadur Gurung of the 3/2 Gurkha Rilfes, the award of the I.O.M. (2nd Class).

At KYAIKTHIN on the night of 2/3 March 1943, the column to which this officer belonged was ambushed. During the resulting confusion he displayed great coolness and courage. After the main body succeeded in breaking off the engagement and extricating itself, this officer continued to occupy the position which he had taken up and to keep the enemy engaged. Although outnumbered he continued to fight and concentrated upon himself the attention of the greater part of the enemy, thus distracting them from pursuing other dispersal groups.

Next day he continued to lead his platoon eastwards in the hope of finding other parties. After a prolonged and unsuccessful search he lead his party safely back to the Chindwin carrying several automatic weapons, additional to his own, which he had found abandoned.

London Gazette 16/12/1943.

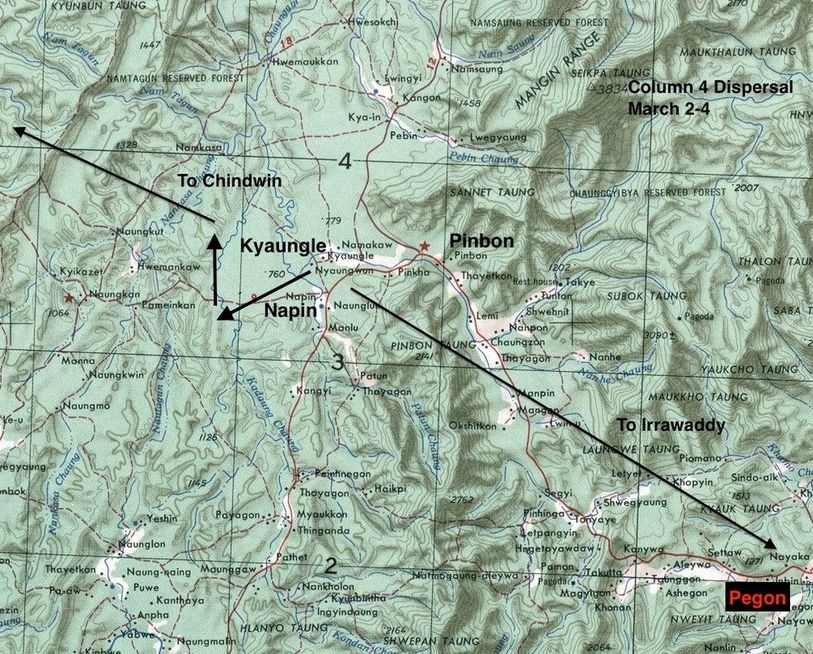

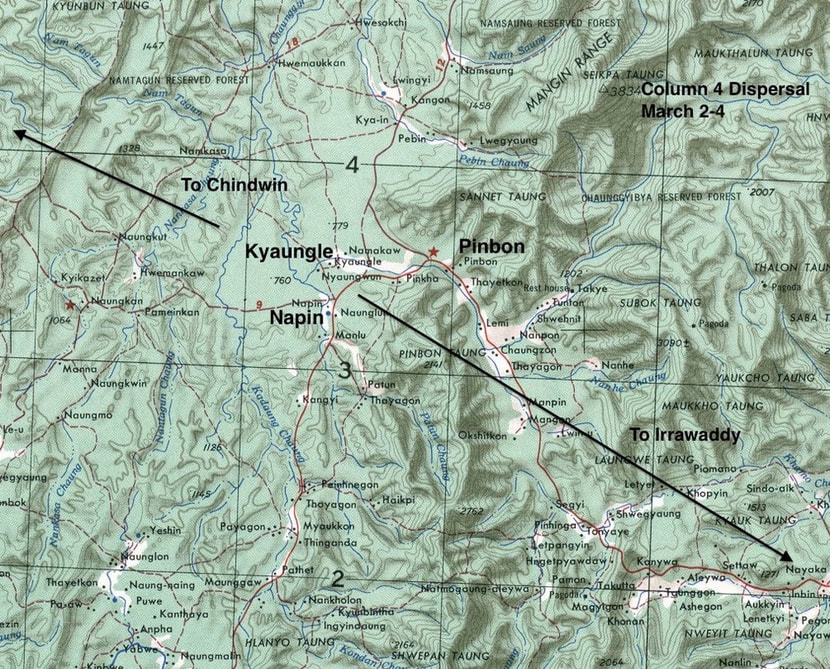

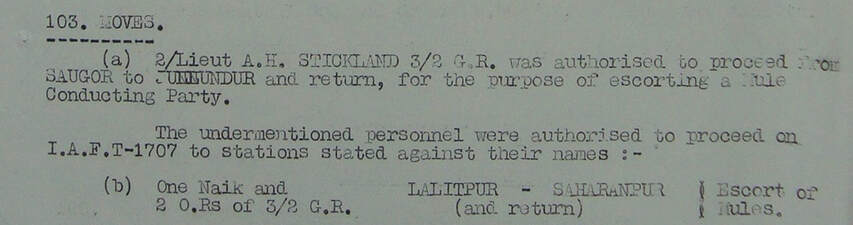

Lance Naik Jit Bahadur Rana IDSM was awarded his gallantry medal for his almost super-human effort to return to Allied territory after general dispersal was called in late March 1943. A member of Column 1 under the command of Major George Dunlop, the young Lance Corporal went through weeks of near starvation and hardship as he inched his way back toward the Assam border. Of all the columns that set out in February that year, Dunlop's unit went the furthest east into Burma, they were also the last group to turn around and head home.

For Column One every obstacle on that return journey cost somebody's life or liberty. The river crossings especially tested the strength and resolve of the men, with only the determined of mind and spirit overcoming each hurdle. Men withdrew into their deepest and sometimes darkest thoughts, focusing only on the next step forward in their desperate attempt for survival.

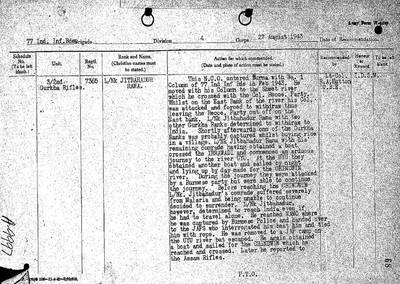

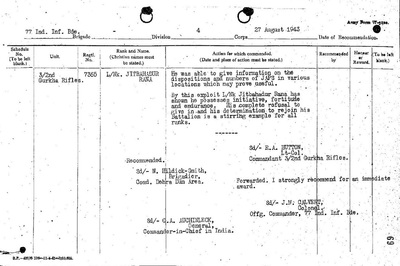

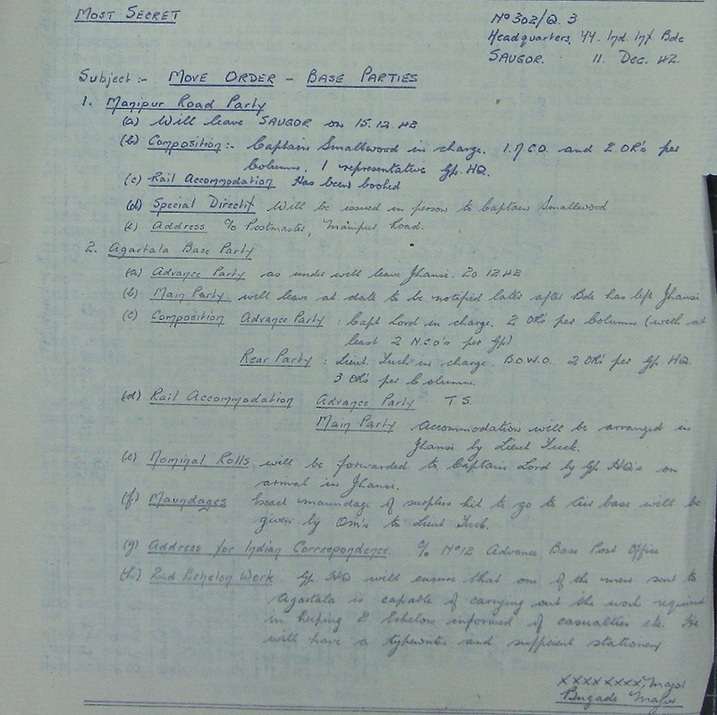

Here is Jit Bahadur's citation in full and seen in its original form, for some reason the recommendation was signed off by Mike Calvert the commander of Column 3, rather than Major Dunlop. Please click on the images to enlarge.

Acting on instinct Man Bahadur dropped down into the gravel embankment and drew his rifle forward in front of him, he called out to his platoon to do the same. Unbeknown to the Chindit column, over 800 Japanese troops had made their way up to Kyaikthin village during the day and had lay in wait for them for the last few hours. Now the Japanese attacked the Gurkhas with everything they possessed and succeeded in cutting the column down into small and disjointed units of men.

A British officer called for dispersal and the signal was given, for those who could hear and understand the instruction it had not come a moment too soon and they melted away into the nearby scrubland and headed east. Column commander Major Emmett had pre-arranged a rendezvous a few miles further east, this was set out specifically for such events as an ambush, but the Japanese had surprised the young Gurkha unit and confusion got the better of them that night.

Jemadar Man Bahadur Gurung and some of his platoon had managed to hold their small position and this had allowed many of the muleteers and other personnel to withdraw into the jungle. He now called to his men to do the same.

Once they had moved a sensible distance away from the chaos of the embankment Man Bahadur took time to assess the condition of his platoon. He found that they had faired reasonably well considering the circumstances of the engagement. The platoon was still in good fighting order, although it had lost two of it's best Riflemen in the form of Man Bir Bura and Man Bahadur Tamang. These losses saddened the young Jemadar as he reflected on his own performance that night.

Here is how the senior commander of column 2, Major A. Emmett recounted Man Bahadur's performance on the 2nd March 1943, shown in the form of his recommendation citation for the Indian Order of Merit (2nd Class), which was awarded to the young Jemadar that year:

For I.O. 1132 Jemadar Man Bahadur Gurung of the 3/2 Gurkha Rilfes, the award of the I.O.M. (2nd Class).

At KYAIKTHIN on the night of 2/3 March 1943, the column to which this officer belonged was ambushed. During the resulting confusion he displayed great coolness and courage. After the main body succeeded in breaking off the engagement and extricating itself, this officer continued to occupy the position which he had taken up and to keep the enemy engaged. Although outnumbered he continued to fight and concentrated upon himself the attention of the greater part of the enemy, thus distracting them from pursuing other dispersal groups.

Next day he continued to lead his platoon eastwards in the hope of finding other parties. After a prolonged and unsuccessful search he lead his party safely back to the Chindwin carrying several automatic weapons, additional to his own, which he had found abandoned.

London Gazette 16/12/1943.

Lance Naik Jit Bahadur Rana IDSM was awarded his gallantry medal for his almost super-human effort to return to Allied territory after general dispersal was called in late March 1943. A member of Column 1 under the command of Major George Dunlop, the young Lance Corporal went through weeks of near starvation and hardship as he inched his way back toward the Assam border. Of all the columns that set out in February that year, Dunlop's unit went the furthest east into Burma, they were also the last group to turn around and head home.

For Column One every obstacle on that return journey cost somebody's life or liberty. The river crossings especially tested the strength and resolve of the men, with only the determined of mind and spirit overcoming each hurdle. Men withdrew into their deepest and sometimes darkest thoughts, focusing only on the next step forward in their desperate attempt for survival.

Here is Jit Bahadur's citation in full and seen in its original form, for some reason the recommendation was signed off by Mike Calvert the commander of Column 3, rather than Major Dunlop. Please click on the images to enlarge.

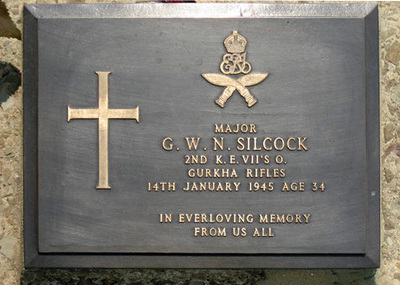

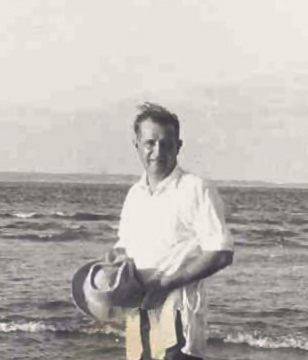

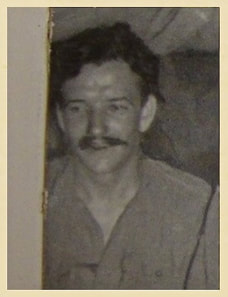

Captain George William Noel Silcock.

"A first class Gurkha Rifles Company Commander." That is how RAF Liaison Officer, Robert Thompson described George Silcock in his own writings about Operation Longcloth, it is a view held by many others who were to work with this dependable and honourable soldier during those torrid months in the Burmese jungle.

The son of George Charles (a licensed victualler by trade) and Louisa Mary Silcock of Clarence Avenue, Kingston-upon-Thames, George Silcock was born on Christmas Day 1911and then attended Cranleigh School between the years 1924 and 1930. Set apart by his dark and bushy moustache, Captain Silcock was originally the senior officer in Column 3 and had led this unit through it's initial Chindit training in 1942. Harold James described him as: "Rather tubby and short, dark with a bristling moustache, which he constantly twirled and possessing a good sense of humour. Because Calvert could not speak Gurkhali, George had to translate orders. This was difficult for him as he did not always see eye to eye with the column commander, and yet he was always honest in his translations and in supporting Calvert.'

There is no doubt that George Silcock was extremely annoyed to have to hand over the command of his unit to Mike Calvert shortly before the men went into Burma, but he remained ever the professional soldier throughout the expedition, ensuring the men fully understood their orders and backing his new C/O to the hilt.

To Calvert's credit, he then allowed Silcock his area of influence within the column and together they achieved, arguably, the best results in regard to deployment of Gurkha Riflemen on Operation Longcloth. Calvert had spotted the Gurkhas dislike and misunderstanding of the dispersal tactic during their training period and he rarely used this system when the column was on active service in Burma. He realised that breaking the unit down into smaller groups when trouble or danger threatened, went totally against the Gurkhas instincts and deep sense of loyalty to what they saw as their extended family. It was at times like these that he took advice from George Silcock and between them they led the Gurkhas with efficiency and care.

In 2008 during my visit to Burma I was fortunate to meet Lieutenant Denis Gudgeon who was also a member of Column 3 on Operation Longcloth. Denis had worked closely with George Silcock whilst in Burma with the Chindits and described him along with Senior Gurkha Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel L.A. Alexander, as, "two of the most honourable and charming gentlemen I have ever met in Army uniform, always, always putting their Gurkhas first, foremost and above everything else".

There is no doubt that Silcock put the wellbeing of his Gurkhas first and foremost, whether that be ensuring they received their correct rations from the air supply drops in 1943, or, on one excruciatingly painful occasion, having to administer a lethal dose of morphine to a suffering and dying rifleman.

Captain Silcock led a section of 142 Commando, as they went about their demolitions at the rail station near Nankan village. He was also given command of one of Column 3's dispersal groups when orders finally came through to return to India. It was at this time that he once again teamed up with Denis Gudgeon. The two officers were given command of a platoon of Gurkhas each and turned westward for home. Silcock succeeded in getting his men back across the Chindwin River, but unfortunately, although his platoon did reach the safety of Assam, Denis himself fell at this final hurdle and was taken prisoner by the Japanese. Once again the compassionate Captain Silcock took the trouble to write to Denis's parents telling them of their son's recent fate and attempted to console them during those desperately worrying times.

After the Chindits had re-grouped back in India, the now Major Silcock was heavily involved in re-organisation of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles at Dehra Dun. Amongst the gallantry awards distributed to the men of Operation Longcloth came a 'Mention in Despatches' for George Silcock. Many of the men he had led and worked with on Operation Longcloth thought that his efforts should have been recognised by a far higher decoration.

Sadly, George Silcock did not survive the war in the Far East, he died on the 14th of January 1945 at a place called Akyab in the Arakan region of Burma. Lieutenant Harold James who was a young subaltern in Chindit Column 3 remembered the last time he saw Silcock in mid-1944:

"I bumped in to George at the Grand Hotel in Calcutta, one of the most famous meeting places for officers during the war. We found to our delight that we were both bound for Darjeeling and agreed to rendezvous at the hill station, where we were able to talk about old times. Then the following year he was tragically killed in an accident at Akyab. It was a sad end for such an excellent, brave officer and a good friend."

Denis Gudgeon added more detail about the accident, telling me that Major Silcock was billeted in a house on that fateful day, after his unit had re-taken an enemy position. Possibly due to fatigue or over-tiredness the Major, whilst still asleep, fell out of the upper window of the house and broke his back.

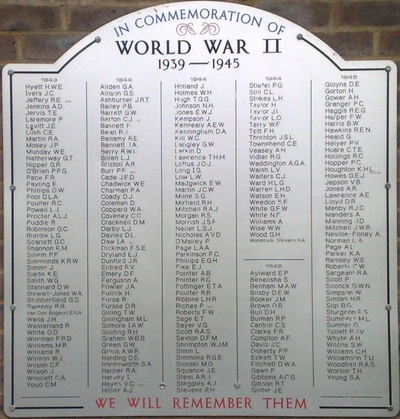

Major George Silcock was buried at Chittagong War Cemetery, now in present day Bangladesh. He is also remembered upon the Surbiton War Memorial in Surrey, close to where he and his family lived before the war. Seen below are photographs of the two memorials for George Silcock and his CWGC details.

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2181102/SILCOCK,%20GEORGE%20WILLIAM%20NOEL

"A first class Gurkha Rifles Company Commander." That is how RAF Liaison Officer, Robert Thompson described George Silcock in his own writings about Operation Longcloth, it is a view held by many others who were to work with this dependable and honourable soldier during those torrid months in the Burmese jungle.

The son of George Charles (a licensed victualler by trade) and Louisa Mary Silcock of Clarence Avenue, Kingston-upon-Thames, George Silcock was born on Christmas Day 1911and then attended Cranleigh School between the years 1924 and 1930. Set apart by his dark and bushy moustache, Captain Silcock was originally the senior officer in Column 3 and had led this unit through it's initial Chindit training in 1942. Harold James described him as: "Rather tubby and short, dark with a bristling moustache, which he constantly twirled and possessing a good sense of humour. Because Calvert could not speak Gurkhali, George had to translate orders. This was difficult for him as he did not always see eye to eye with the column commander, and yet he was always honest in his translations and in supporting Calvert.'

There is no doubt that George Silcock was extremely annoyed to have to hand over the command of his unit to Mike Calvert shortly before the men went into Burma, but he remained ever the professional soldier throughout the expedition, ensuring the men fully understood their orders and backing his new C/O to the hilt.

To Calvert's credit, he then allowed Silcock his area of influence within the column and together they achieved, arguably, the best results in regard to deployment of Gurkha Riflemen on Operation Longcloth. Calvert had spotted the Gurkhas dislike and misunderstanding of the dispersal tactic during their training period and he rarely used this system when the column was on active service in Burma. He realised that breaking the unit down into smaller groups when trouble or danger threatened, went totally against the Gurkhas instincts and deep sense of loyalty to what they saw as their extended family. It was at times like these that he took advice from George Silcock and between them they led the Gurkhas with efficiency and care.

In 2008 during my visit to Burma I was fortunate to meet Lieutenant Denis Gudgeon who was also a member of Column 3 on Operation Longcloth. Denis had worked closely with George Silcock whilst in Burma with the Chindits and described him along with Senior Gurkha Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel L.A. Alexander, as, "two of the most honourable and charming gentlemen I have ever met in Army uniform, always, always putting their Gurkhas first, foremost and above everything else".

There is no doubt that Silcock put the wellbeing of his Gurkhas first and foremost, whether that be ensuring they received their correct rations from the air supply drops in 1943, or, on one excruciatingly painful occasion, having to administer a lethal dose of morphine to a suffering and dying rifleman.

Captain Silcock led a section of 142 Commando, as they went about their demolitions at the rail station near Nankan village. He was also given command of one of Column 3's dispersal groups when orders finally came through to return to India. It was at this time that he once again teamed up with Denis Gudgeon. The two officers were given command of a platoon of Gurkhas each and turned westward for home. Silcock succeeded in getting his men back across the Chindwin River, but unfortunately, although his platoon did reach the safety of Assam, Denis himself fell at this final hurdle and was taken prisoner by the Japanese. Once again the compassionate Captain Silcock took the trouble to write to Denis's parents telling them of their son's recent fate and attempted to console them during those desperately worrying times.

After the Chindits had re-grouped back in India, the now Major Silcock was heavily involved in re-organisation of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles at Dehra Dun. Amongst the gallantry awards distributed to the men of Operation Longcloth came a 'Mention in Despatches' for George Silcock. Many of the men he had led and worked with on Operation Longcloth thought that his efforts should have been recognised by a far higher decoration.

Sadly, George Silcock did not survive the war in the Far East, he died on the 14th of January 1945 at a place called Akyab in the Arakan region of Burma. Lieutenant Harold James who was a young subaltern in Chindit Column 3 remembered the last time he saw Silcock in mid-1944:

"I bumped in to George at the Grand Hotel in Calcutta, one of the most famous meeting places for officers during the war. We found to our delight that we were both bound for Darjeeling and agreed to rendezvous at the hill station, where we were able to talk about old times. Then the following year he was tragically killed in an accident at Akyab. It was a sad end for such an excellent, brave officer and a good friend."

Denis Gudgeon added more detail about the accident, telling me that Major Silcock was billeted in a house on that fateful day, after his unit had re-taken an enemy position. Possibly due to fatigue or over-tiredness the Major, whilst still asleep, fell out of the upper window of the house and broke his back.

Major George Silcock was buried at Chittagong War Cemetery, now in present day Bangladesh. He is also remembered upon the Surbiton War Memorial in Surrey, close to where he and his family lived before the war. Seen below are photographs of the two memorials for George Silcock and his CWGC details.

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2181102/SILCOCK,%20GEORGE%20WILLIAM%20NOEL

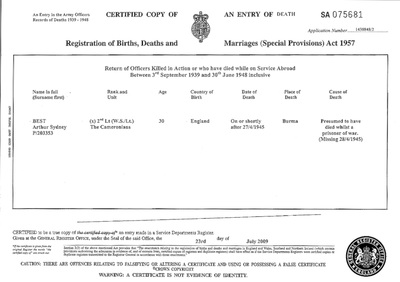

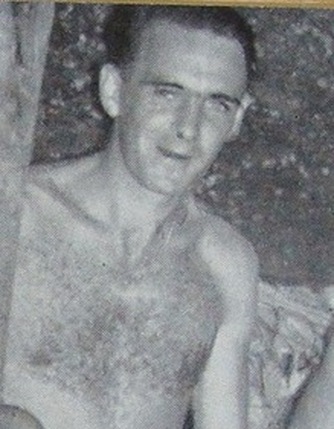

Lieutenant Arthur Sidney Best.

Arthur was the son of Thomas and Elizabeth Best from Sompting in Sussex. He was born sometime in 1916 and in civilian life was a bank clerk and lived in the Balaam area of London. In 1943 Lieutenant Best found himself the Animal Transport Officer for Chindit Column 2 and in charge of the units Gurkha muleteers. Earlier in WW2 he had been fighting with the Territorial Army Battalion of the London Rifle Brigade and had served and survived the Allied reverse at Dunkirk, before joining the 9th Gurkhas in 1941.

Aged almost 30 by the time he served with the Chindits in Burma, Arthur Best was very much looked up to by many of the younger Gurkha subalterns, men such as Ian MacHorton, Alec Gibson and Denis Gudgeon. His experience and cool head had also resulted in Lieutenant Best being asked to perform other important duties during Chindit training, he was often asked for instance to sit on review panels and on at least one occasion a Court Martial hearing.

Here is how the young and inexperienced 2nd Lieutenant, Ian MacHorton remembered his friend from those times:

"In the hot stillness of our jungle hiding place I could at that moment afford to look with affection upon Arthur, and to contemplate my happy association with him since I had joined the Chindits. He had been my instructor, confessor, and continuous companion since I had joined the column.

Though he was a few years older than I, we had discovered many mutual interests. In fact, during many hours of jungle conversation our only serious difference of opinion had been over our respective views on the works of Mr. Ivor Novello and the value of the ballet as a medium for the expression of art. Differences hardly likely to cause a rift between us as we fought our way, often side by side, through the dense jungle to fulfil our task as decoys for Wingate's main striking force. So new a soldier myself, I regarded Arthur with all the respect that a recruit should give to a veteran.

A bank clerk in civil life, Arthur Best had been a rifleman in a crack Territorial Army Battalion of the London Rifle Brigade. He had known the ferocity and carnage of war and the heat of battle in the very early days. He had been one of those battered, bewildered, exhausted, outnumbered but indomitable British soldiers who had fought the rearguard action against the Germans all the way down to the beaches of Dunkirk.

Sometimes at night, before we rolled over to sleep deep in the whispering jungle, Arthur would paint for me lurid pictures of fighting against the Germans in France. I was proud that I, even though only a schoolboy of sixteen, had played my very small part in helping with the evacuation from those famous beaches.

My father had owned a 35ft. launch which was moored in Weymouth Harbour, and I had accompanied him on the high adventure of ferrying rescued soldiers back to Weymouth and Poole, from Dover, Beachy Head, and other places where they had been put down by the little ships shuttling valiantly backwards and forwards between England and France.

To be serving now with a man who had been through the real thing was quite something. After his showing in France and at Dunkirk, Arthur Best was put forward as the right material for an officer, and was eventually commissioned into the 9th Gurkha Rifles, during 1941. He had found his work tedious at his Regimental Centre and had volunteered for "special duty" with the 77th Independent Infantry Brigade. It was only natural that, by virtue of the fact that he was a keen amateur mechanic, he should immediately have been appointed Animal Transport Officer in charge of No. 2 Column's mules when he joined the Wingate force.

All through those days now behind us, of fighting our way through bitter jungle always beneath the unrelenting blaze of the Burmese sun, Arthur had been a strong and staunch companion. He had been a stout friend to whom I could look for help and advice whenever I needed it. And now, on what was likely to be the eve of my first battle, I was more glad than ever to have him beside me."

That first battle was to come sooner than 2nd Lieutenant MacHorton might have imagined. On the 2nd of March 1943 at the railway town of Kyaikthin Chindit Column 2 were ambushed by a large Japanese force and a ferocious battle took place. Column 2 fared worse and in the carnage that night Arthur Best was fortunate indeed to lead most of his Gurkhas and their mules away from the battle field and into the nearby scrub jungle.

The next morning he met up with the Column's RAF Liaison Officer, Flight Lieutenant John Kingsley Edmonds and under his charge moved off towards the formerly agreed rendezvous point close to the western banks of the Irrawaddy River. This small group met Chindit Column 1 along the way and became part of this unit led by Major George Dunlop of the Royal Scots. Arthur Best remained with Dunlop's group for the next six weeks and was with the Major when dispersal was called and the men turned round and began the long and arduous march back to India.

It was on this return journey that things began to go wrong for the beleaguered Chindits. They struggled to find enough food and water when entering the villages they passed through and the many Burmese rivers, both large and small, proved at times almost insurmountable obstacles for the weary men. On the 2nd May, the Column were searching for food in a small village near the River Mu when they were attacked by a Japanese patrol. Enemy machine gun fire raked through the line of unsuspecting Chindits, killing many and wounding a great deal more.

Once again, I will allow Ian Machorton to describe that hellish moment:

"Slowly and methodically men everywhere got to their feet. They began to wriggle into their equipment and take anew the strain of their packs. Arthur Best was to be the advance guard for what was left of the column and with a lighthearted wave turned and was gone. Gone forever-gone amidst the sudden vicious hail of bullets which tore into us at that moment from the Jap fighting patrol who had sneaked up on us through the jungle. Gone, I was to learn years later, to be murdered as a prisoner of war by the bayonets of the brutal little Jap animals that had been sent to guard him."

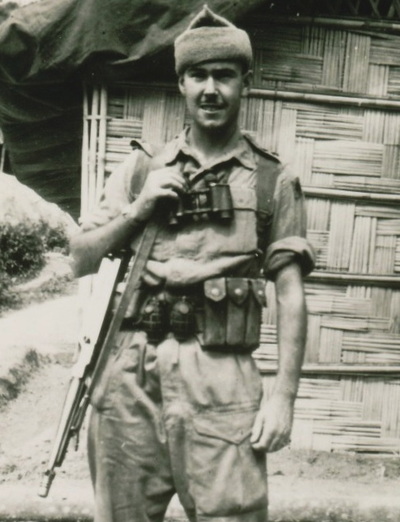

Seen below are images of Arthur Best and his young Chindit comrade 2nd Lieutenant Ian MacHorton. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Arthur was the son of Thomas and Elizabeth Best from Sompting in Sussex. He was born sometime in 1916 and in civilian life was a bank clerk and lived in the Balaam area of London. In 1943 Lieutenant Best found himself the Animal Transport Officer for Chindit Column 2 and in charge of the units Gurkha muleteers. Earlier in WW2 he had been fighting with the Territorial Army Battalion of the London Rifle Brigade and had served and survived the Allied reverse at Dunkirk, before joining the 9th Gurkhas in 1941.

Aged almost 30 by the time he served with the Chindits in Burma, Arthur Best was very much looked up to by many of the younger Gurkha subalterns, men such as Ian MacHorton, Alec Gibson and Denis Gudgeon. His experience and cool head had also resulted in Lieutenant Best being asked to perform other important duties during Chindit training, he was often asked for instance to sit on review panels and on at least one occasion a Court Martial hearing.

Here is how the young and inexperienced 2nd Lieutenant, Ian MacHorton remembered his friend from those times:

"In the hot stillness of our jungle hiding place I could at that moment afford to look with affection upon Arthur, and to contemplate my happy association with him since I had joined the Chindits. He had been my instructor, confessor, and continuous companion since I had joined the column.

Though he was a few years older than I, we had discovered many mutual interests. In fact, during many hours of jungle conversation our only serious difference of opinion had been over our respective views on the works of Mr. Ivor Novello and the value of the ballet as a medium for the expression of art. Differences hardly likely to cause a rift between us as we fought our way, often side by side, through the dense jungle to fulfil our task as decoys for Wingate's main striking force. So new a soldier myself, I regarded Arthur with all the respect that a recruit should give to a veteran.

A bank clerk in civil life, Arthur Best had been a rifleman in a crack Territorial Army Battalion of the London Rifle Brigade. He had known the ferocity and carnage of war and the heat of battle in the very early days. He had been one of those battered, bewildered, exhausted, outnumbered but indomitable British soldiers who had fought the rearguard action against the Germans all the way down to the beaches of Dunkirk.

Sometimes at night, before we rolled over to sleep deep in the whispering jungle, Arthur would paint for me lurid pictures of fighting against the Germans in France. I was proud that I, even though only a schoolboy of sixteen, had played my very small part in helping with the evacuation from those famous beaches.

My father had owned a 35ft. launch which was moored in Weymouth Harbour, and I had accompanied him on the high adventure of ferrying rescued soldiers back to Weymouth and Poole, from Dover, Beachy Head, and other places where they had been put down by the little ships shuttling valiantly backwards and forwards between England and France.

To be serving now with a man who had been through the real thing was quite something. After his showing in France and at Dunkirk, Arthur Best was put forward as the right material for an officer, and was eventually commissioned into the 9th Gurkha Rifles, during 1941. He had found his work tedious at his Regimental Centre and had volunteered for "special duty" with the 77th Independent Infantry Brigade. It was only natural that, by virtue of the fact that he was a keen amateur mechanic, he should immediately have been appointed Animal Transport Officer in charge of No. 2 Column's mules when he joined the Wingate force.

All through those days now behind us, of fighting our way through bitter jungle always beneath the unrelenting blaze of the Burmese sun, Arthur had been a strong and staunch companion. He had been a stout friend to whom I could look for help and advice whenever I needed it. And now, on what was likely to be the eve of my first battle, I was more glad than ever to have him beside me."

That first battle was to come sooner than 2nd Lieutenant MacHorton might have imagined. On the 2nd of March 1943 at the railway town of Kyaikthin Chindit Column 2 were ambushed by a large Japanese force and a ferocious battle took place. Column 2 fared worse and in the carnage that night Arthur Best was fortunate indeed to lead most of his Gurkhas and their mules away from the battle field and into the nearby scrub jungle.

The next morning he met up with the Column's RAF Liaison Officer, Flight Lieutenant John Kingsley Edmonds and under his charge moved off towards the formerly agreed rendezvous point close to the western banks of the Irrawaddy River. This small group met Chindit Column 1 along the way and became part of this unit led by Major George Dunlop of the Royal Scots. Arthur Best remained with Dunlop's group for the next six weeks and was with the Major when dispersal was called and the men turned round and began the long and arduous march back to India.

It was on this return journey that things began to go wrong for the beleaguered Chindits. They struggled to find enough food and water when entering the villages they passed through and the many Burmese rivers, both large and small, proved at times almost insurmountable obstacles for the weary men. On the 2nd May, the Column were searching for food in a small village near the River Mu when they were attacked by a Japanese patrol. Enemy machine gun fire raked through the line of unsuspecting Chindits, killing many and wounding a great deal more.

Once again, I will allow Ian Machorton to describe that hellish moment:

"Slowly and methodically men everywhere got to their feet. They began to wriggle into their equipment and take anew the strain of their packs. Arthur Best was to be the advance guard for what was left of the column and with a lighthearted wave turned and was gone. Gone forever-gone amidst the sudden vicious hail of bullets which tore into us at that moment from the Jap fighting patrol who had sneaked up on us through the jungle. Gone, I was to learn years later, to be murdered as a prisoner of war by the bayonets of the brutal little Jap animals that had been sent to guard him."

Seen below are images of Arthur Best and his young Chindit comrade 2nd Lieutenant Ian MacHorton. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

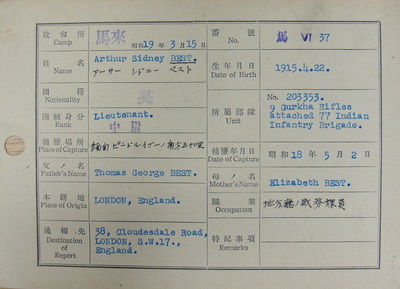

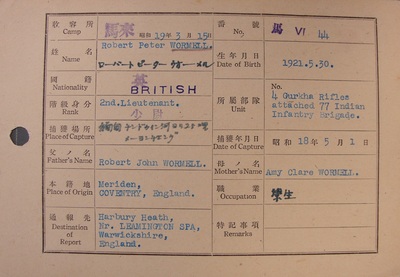

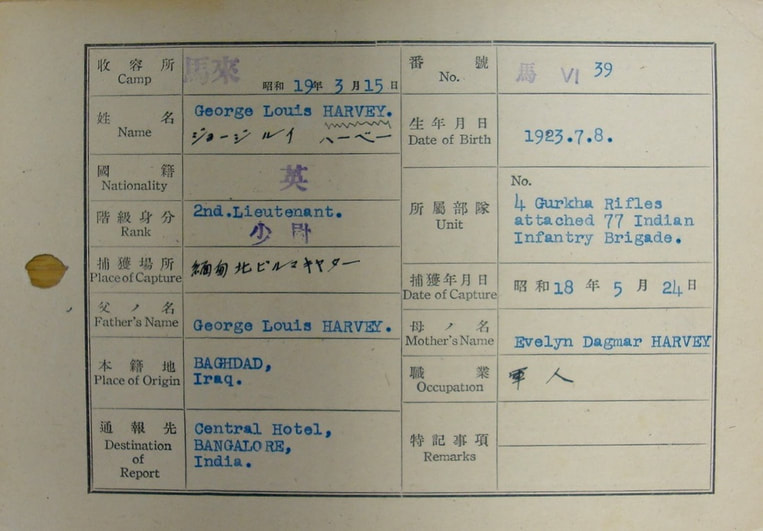

Ian MacHorton had understandably feared the worst for his friend after the attack near the River Mu, but, as he later found out, Arthur Best had in fact survived the engagement and been taken prisoner by the Japanese. On his POW records it states the 2nd of May 1943 as his date of capture.

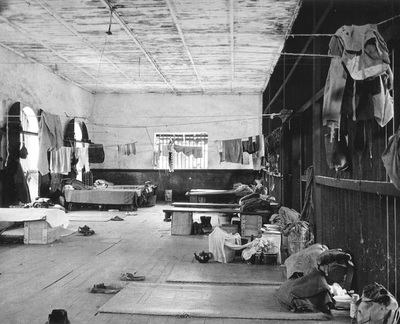

Lieutenant Best was to spend nearly two years in Rangoon Jail, sharing a large and uncomfortable cell with the other captured Chindit Officers; men such as Denis Gudgeon, Alec Gibson and Flight Lieutenant John Edmonds. He was given the POW number 37 and had to learn how to recite this number in Japanese for the morning and evening roll calls known as 'tenkos'.

In late April 1945 the Japanese guards selected 400 or so of the fittest prisoners and marched them out of Rangoon Jail. The idea was to take these men across the border and into Thailand, probably to work on the northern section of infamous Burma Railway. Within a few short days the Japanese realised that this had been a mistake and set the prisoners free close to a village called Waw near Pegu.

Sadly, Arthur Best did not enjoy the euphoria of being liberated that day. He had struggled to keep up with the line of march from the outset and suffering badly from exhaustion and fatigue, continually dropped down by the roadside to take a rest. The Japanese guards had repeatedly warned the prisoners that any man who dropped out of line and could no longer march would be dealt with in the severest manner. Arthur's Chindit pals, including Denis Gudgeon, had supported their comrade for as long as their own weary bodies would allow. Finally and in exasperation, they urged their friend to make one last effort to continue marching. Arthur waved them away, repeating that he simply needed a short rest and would catch them up at the next halt. They never saw him again.

In 2008 whilst on tour in Burma, Denis Gudgeon informed me that the Japanese guards had bayonetted Lieutenant Best where he lay and left him to die on the roadside. Denis was still clearly upset when recalling that terrible moment from April 1945. Here is a very short piece from my audio recordings with Denis, where he remembers the last conversation he had with Arthur Best.

Lieutenant Best was to spend nearly two years in Rangoon Jail, sharing a large and uncomfortable cell with the other captured Chindit Officers; men such as Denis Gudgeon, Alec Gibson and Flight Lieutenant John Edmonds. He was given the POW number 37 and had to learn how to recite this number in Japanese for the morning and evening roll calls known as 'tenkos'.

In late April 1945 the Japanese guards selected 400 or so of the fittest prisoners and marched them out of Rangoon Jail. The idea was to take these men across the border and into Thailand, probably to work on the northern section of infamous Burma Railway. Within a few short days the Japanese realised that this had been a mistake and set the prisoners free close to a village called Waw near Pegu.

Sadly, Arthur Best did not enjoy the euphoria of being liberated that day. He had struggled to keep up with the line of march from the outset and suffering badly from exhaustion and fatigue, continually dropped down by the roadside to take a rest. The Japanese guards had repeatedly warned the prisoners that any man who dropped out of line and could no longer march would be dealt with in the severest manner. Arthur's Chindit pals, including Denis Gudgeon, had supported their comrade for as long as their own weary bodies would allow. Finally and in exasperation, they urged their friend to make one last effort to continue marching. Arthur waved them away, repeating that he simply needed a short rest and would catch them up at the next halt. They never saw him again.

In 2008 whilst on tour in Burma, Denis Gudgeon informed me that the Japanese guards had bayonetted Lieutenant Best where he lay and left him to die on the roadside. Denis was still clearly upset when recalling that terrible moment from April 1945. Here is a very short piece from my audio recordings with Denis, where he remembers the last conversation he had with Arthur Best.

Arthur Best was killed by the Japanese on the 28th April 1943, just a few short hours before the other POW's were given their freedom. His body was never recovered, and so, unlike the other men who perished whilst prisoners of war in Rangoon, he is remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial and not in Rangoon War Cemetery. Here are his CWGC details:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2505162/BEST,%20ARTHUR%20SIDNEY

Seen below are some images that illustrate the story of Arthur Best and his sad demise in April 1945. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To finish this story, I will share Denis Gudgeon's thoughts about Lieutenant Arthur Sidney Best from our conversations in Burma in March 2008.

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2505162/BEST,%20ARTHUR%20SIDNEY

Seen below are some images that illustrate the story of Arthur Best and his sad demise in April 1945. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. To finish this story, I will share Denis Gudgeon's thoughts about Lieutenant Arthur Sidney Best from our conversations in Burma in March 2008.

"Arthur was a good soldier and Gurkha officer, there is no doubt; but more importantly he was a very good friend."

Update 17/10/2019.

Another account of what happened to Arthur Best on the march out from Rangoon has come to light in a book entitled: Pilot, Prisoner, Survivor, written by Harvey Besley a former pilot with the Royal Australian Air Force and erstwhile POW inside Rangoon Jail.

Besley recalled:

By the second night of the march the men were all hungry and suffering with their feet. To say the least it was a bleak outlook, but the third night was far worse. Allied planes were coming over constantly and we had to duck for cover whenever we heard them. The guards had become bad tempered and had begun to hit and push us around and generally make life hell for us. We were sick to the teeth of them and the whole show. They seemed to have to take their frustrations out on us whenever things went wrong. Several of the men dropped out; they could no longer take the marching.

One of the first to drop out was Lieutenant Best. He had been in bad health and weak back in the gaol. He should never have been allowed to come in the first place. But being an officer, he was left to decide for himself, and naturally he came along. It was thought at the time, that anyone left at the gaol would be shot as soon as the others left. Naturally, anyone who was at all able to walk, wanted to leave. As things turned out, it was the other way around. Those who stayed behind got the best of the deal, but we were not to know that at the time.

When a prisoner dropped out, a guard was left behind with him. We felt pretty sure that the guard either shot or bayonetted the prisoner as soon as we got out of hearing. It was fairly conclusive, as the guard would catch up to us within half an hour and tell us that the prisoner had been left with some natives. Three of our number suffered this fate. On one occasion, one of my group an Australian named Peter Wilson collapsed, but being with a cart we were able to go on by getting him onto the cart and giving him a rest. He was then able to manage under his own steam after this, but I've no doubt that the ride on the cart saved his life. At this stage, the men were in a desperate state and it was only the knowledge of what would happen if they dropped out which drove them on.

Another account of what happened to Arthur Best on the march out from Rangoon has come to light in a book entitled: Pilot, Prisoner, Survivor, written by Harvey Besley a former pilot with the Royal Australian Air Force and erstwhile POW inside Rangoon Jail.

Besley recalled:

By the second night of the march the men were all hungry and suffering with their feet. To say the least it was a bleak outlook, but the third night was far worse. Allied planes were coming over constantly and we had to duck for cover whenever we heard them. The guards had become bad tempered and had begun to hit and push us around and generally make life hell for us. We were sick to the teeth of them and the whole show. They seemed to have to take their frustrations out on us whenever things went wrong. Several of the men dropped out; they could no longer take the marching.

One of the first to drop out was Lieutenant Best. He had been in bad health and weak back in the gaol. He should never have been allowed to come in the first place. But being an officer, he was left to decide for himself, and naturally he came along. It was thought at the time, that anyone left at the gaol would be shot as soon as the others left. Naturally, anyone who was at all able to walk, wanted to leave. As things turned out, it was the other way around. Those who stayed behind got the best of the deal, but we were not to know that at the time.

When a prisoner dropped out, a guard was left behind with him. We felt pretty sure that the guard either shot or bayonetted the prisoner as soon as we got out of hearing. It was fairly conclusive, as the guard would catch up to us within half an hour and tell us that the prisoner had been left with some natives. Three of our number suffered this fate. On one occasion, one of my group an Australian named Peter Wilson collapsed, but being with a cart we were able to go on by getting him onto the cart and giving him a rest. He was then able to manage under his own steam after this, but I've no doubt that the ride on the cart saved his life. At this stage, the men were in a desperate state and it was only the knowledge of what would happen if they dropped out which drove them on.

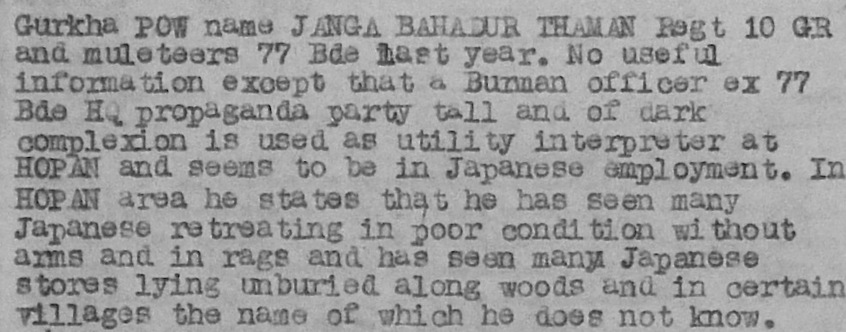

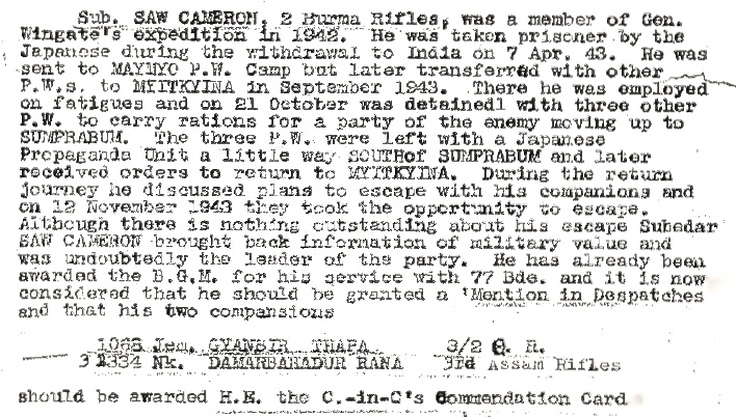

Rifleman Janga Bahadur Thaman. This soldier was originally serving with the 10th Gurkha Regiment before he was drafted into the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade as a mule driver in late 1942. It is not known which Chindit Column Janga belonged to on Operation Longcloth, but we do know that he became a prisoner of war in 1943.

The Japanese tended to keep captured Gurkha Riflemen working for them in the field, rather than sending them on to large camps such Maymyo or Rangoon Jail. Often they were used as muleteers by their captors, transporting supplies up to the front line, especially during the battles of Imphal and Kohima. So, quite often the captured Gurkhas found themselves working close to the Assam border at places like Kalaw on the eastern banks of the Chindwin River. Many used this opportunity to break for freedom and escape back to Allied held territory.

We know that Janga Bahadur Thaman was a POW because he was recovered by Chindit Column 65, part of the 14th British Infantry Brigade in July 1944 during the second Chindit operation. After giving information at his debrief interview, Janga was cleared of any collusion with the enemy and returned to the Regimental Centre for the 10th Gurkha Rifles where he re-joined his original unit.

Seen below is a copy of the war diary entry recording his liberation by Column 65 on the 16th July 1944.

The Japanese tended to keep captured Gurkha Riflemen working for them in the field, rather than sending them on to large camps such Maymyo or Rangoon Jail. Often they were used as muleteers by their captors, transporting supplies up to the front line, especially during the battles of Imphal and Kohima. So, quite often the captured Gurkhas found themselves working close to the Assam border at places like Kalaw on the eastern banks of the Chindwin River. Many used this opportunity to break for freedom and escape back to Allied held territory.

We know that Janga Bahadur Thaman was a POW because he was recovered by Chindit Column 65, part of the 14th British Infantry Brigade in July 1944 during the second Chindit operation. After giving information at his debrief interview, Janga was cleared of any collusion with the enemy and returned to the Regimental Centre for the 10th Gurkha Rifles where he re-joined his original unit.

Seen below is a copy of the war diary entry recording his liberation by Column 65 on the 16th July 1944.

Captain Hubert R. Birtwhistle. Hubert Birtwhistle was the Adjutant for Southern Group in 1942/43. It was his task to collate all the new personnel recently posted to the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles in preparation for Operation Longcloth and to allocate them to a Chindit Column. It seems that for all the young officers attached to 3/2 Gurkha in the last few weeks of 1942 and early 1943, Hubert came over as a 'larger than life' sort of character, possessing a dry, sardonic sense of humour.

After the operation was closed in mid-1943 he was also given the job of reorganising the battalion at their base in Dehra Dun. As the exhausted Gurkhas returned in small penny-packets from their exertions in Burma, Hubert also compiled the casualty and missing in action listings for the battalion, which must have been an unenviable and heart-breaking duty to perform.

Two of the young Gurkha subalterns who served on Operation Longcloth, Ian MacHorton and Harold James, both described their first meeting with Captain Birtwhistle in their respective books, 'Safer than a Known Way' and 'Across the Threshold of Battle'.

MacHorton remembered:

"The story had started for me at Jhansi, a cantonment in Indian jungle country where the Chindits had done most of their training. In the sweltering heat of the afternoon I arrived and I sensed at once the atmosphere was electric. Newly commissioned, I was joining them on the very eve of entraining for Dimapur, on the Assam-Burma border, from where the great march eastwards was to start.

Captain Birtwhistle from 3/2 Gurkha Rifles and Adjutant of No. 1 Group, was sitting at a blanket-covered trestle table in the 180-pounder tent which served as the orderly room for the battalion. I stamped in smartly to announce my arrival and the interior of the tent engulfed me in heat, like an oven.

Sweat was coursing down the Adjutant's face as he looked up sharply. It ran in rivulets down his chest, and dripped steadily from his armpits. Sweating just as liberally, I stood at ease before him, and watched him pick up his fountain pen and dry his fingers on the blanket table cover before attempting to write my name in capital letters on the pro-forma before him.

As he wrote the date, January 7th, 1943, sweat from his brow dropped on the paper and smudged the ink, so that he had to dab it with a corner of the blanket and write anew beside the smudging. "Rank, 2nd Lieutenant," he mumbled, seemingly to himself, as he began to fill in the details. "Regiment, 8th Gurkhas." He looked up: "Date of present commission?"

"The fourth of October, sir, 1942," I replied.

"Age?"

"Nineteen."

"Next of kin?"

"Father, sir."

And so, in between pauses to mop sweat from his brow and chest with a sodden handkerchief, and to blot it from the paper in a hopeless attempt to keep the pro-forma neat, he filled in all my particulars. "Right. Now you are to join No. 2 Column," he said tersely. "Major Emmett is in command. You had better report straight away, there is not a lot of time."

I took one pace to the rear and saluted. The great adventure had started."

Lieutenant Harold James, who was to be awarded a Military Cross for his efforts on Operation Longcloth was with Ian MacHorton that day; he remembered the same meeting thus:

"I was one of the several junior officers from other Gurkha and British Regiments transferred to the Brigade at almost the last hour. Only a few months earlier I had been commissioned into the 8th Gurkha Rifles and posted to the Regimental Centre at Quetta in Northern India with my friend, Ian MacHorton. Shortly afterwards we were joined by Alec Mackay Gibson.

A week or so after Christmas mysterious orders were received posting the three of us to an unspecified formation in Jhansi. Everyone in the Regimental Centre was foxed, and as it appeared to be a permanent posting we took, as was the custom in those days, all our gear in steel trunks, the usual portable gramophone and our Indian bearers.