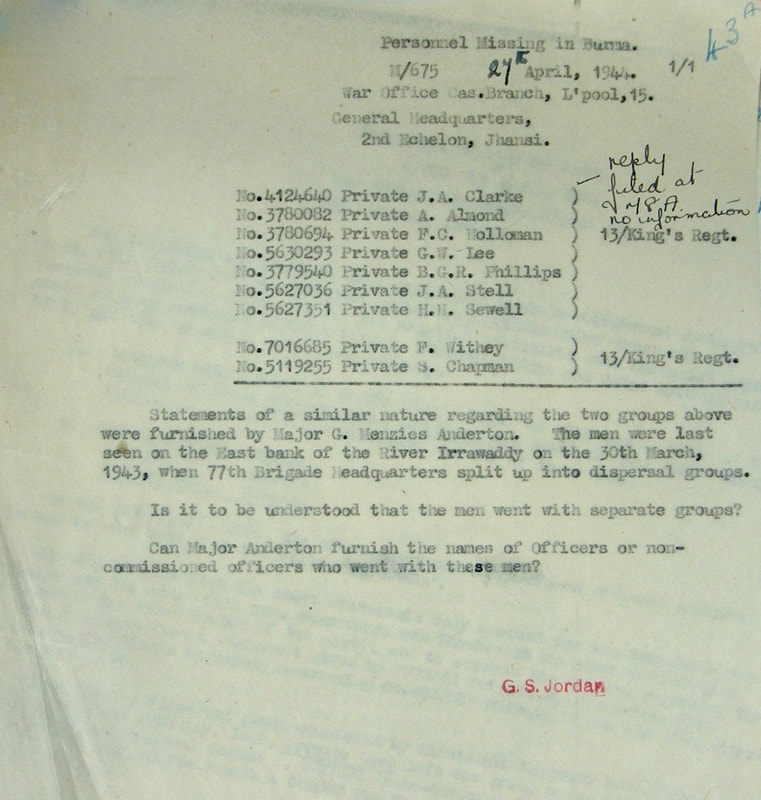

Pte. Fred Holloman

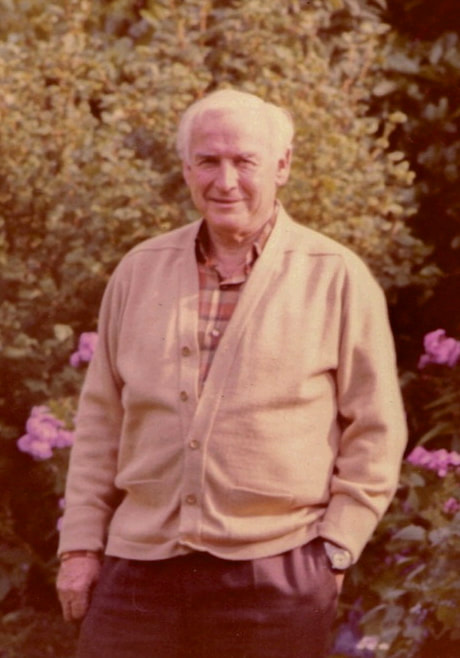

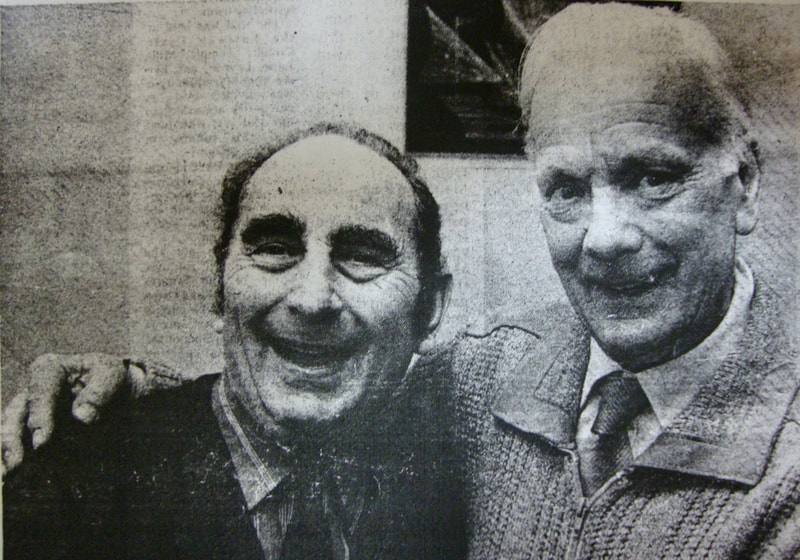

Fred Holloman in 1988.

Fred Holloman in 1988.

Turned out rice again ain't it? The story of Pte. Frederick Holloman.

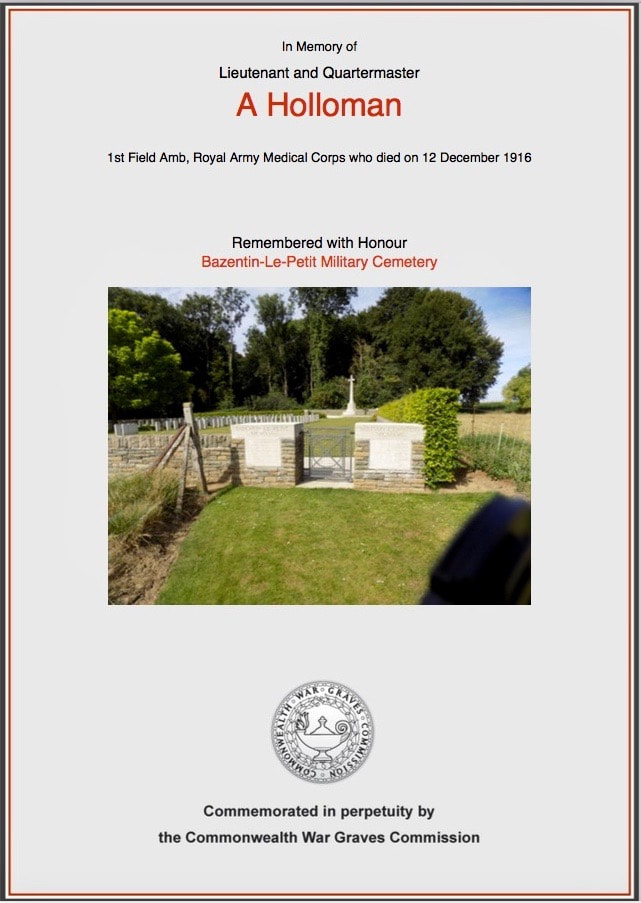

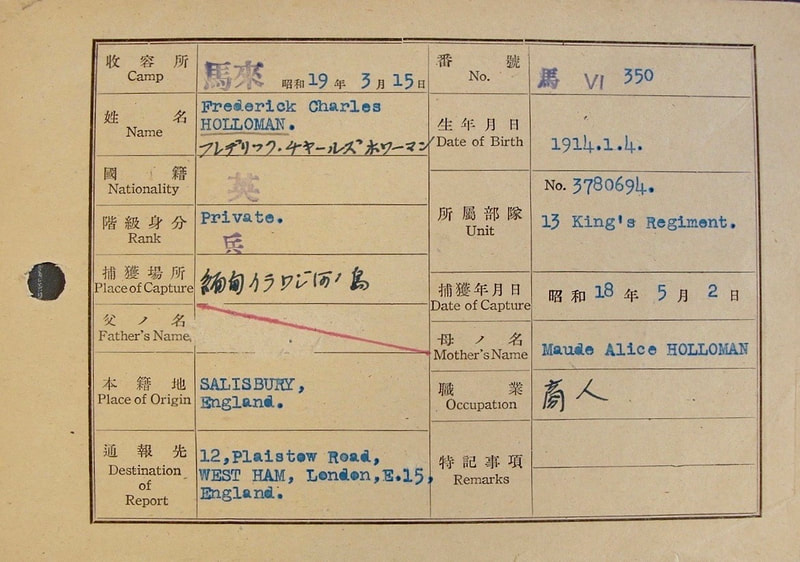

Frederick Charles Holloman was the son of Arthur and Maude Alice Holloman and was born on the 4th January 1914, at the Bulford Army Camp, Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire. His father, Lieutenant Quartermaster Arthur Holloman was killed during WW1 on the 12th December 1916, whilst serving in France with the 1st Field Ambulance of the Royal Army Medical Corps.

After the death of his father, Fred left the Army Camp at Bulford with his mother and brother and moved to the east end of London. He went to school in Plaistow, leaving at the age of fourteen to take up an apprenticeship in metal engraving. Fred did not enjoy his first job and quickly gave it up in order to work for his mother at her public house in Limehouse and later another pub in West Ham.

Fred received his call up papers in late 1940 and these came as rather a shock to the 26 year old publican's assistant. His brother was posted to the Pioneer Corps and began his Army life clearing away the bomb-blasted buildings of the London Blitz. Meanwhile, Fred had been sent to join the 13th Battalion of the King's (Liverpool) Regiment at the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow. He undertook three months of basic infantry training at Jordan Hill, before the battalion were posted to Clacton-on-Sea in Essex. Here the 13th King's performed coastal defence duties, in preparation against the expected German sea-born invasion.

Over the coming year the 13th King's moved around the the south-eastern counties of England, taking up postings at Ipswich, Colchester and Felixstowe. By the middle of 1941, the battalion were sent to Market Harborough in Leicestershire, where they carried out farming work, preparing the fields for new crops and receiving for their trouble an extra shilling per day over and above their Army wages. Working on the land had another benefit according to Fred, who remembered with great relish the grand assortment of fruit and vegetables available on the farms, which were a far cry from the Army rations the men had been used to previously.

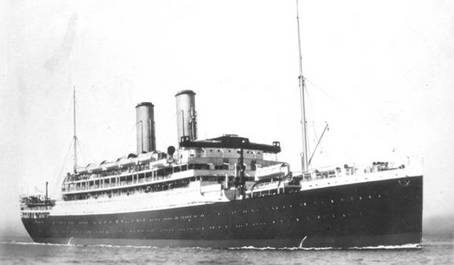

In November 1941, the 13th King's moved to an Army camp located just outside Blackburn in Lancashire. The move to Blackburn had been cloaked in secrecy and had intrigued the battalion. At the end of the month the men were told to prepare for a move to Liverpool and overseas service, destination unknown. On the 7th December, the men boarded the troopship Oronsay at the Victoria Docks in Liverpool and sailed the following day north to Greenock in Scotland. Here they formed up into convoy and moved out into the North Atlantic heading west for a few days, before dropping south towards the Azores. Fred found life below decks very claustrophobic and uncomfortable. The Other Ranks form the battalion were billeted in the lower decks of the vessel and close to the smell and noise of the ships engines. Many men including Pte. Holloman suffered with sea sickness in these early days of the voyage.

On Christmas Day 1941, the Oronsay docked just outside Freetown, Sierra Leone and the vessel was re-stocked for the onward journey. No shore-leave was granted at Freetown, but a week or so later, when the the ship docked at Durban in South Africa the men were allowed off the troopship for the first time. Many of the men including Fred, were amazed at the generosity of the local population, who met the British soldiers at the quayside and took them off to their homes and cooked the men sumptuous meals, involving food that many of the English lads had not seen or tasted for several years. Fred Holloman in his audio memoir, recorded at the Imperial War Museum in December 1996, described Durban as: the land of milk and honey.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Frederick Charles Holloman was the son of Arthur and Maude Alice Holloman and was born on the 4th January 1914, at the Bulford Army Camp, Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire. His father, Lieutenant Quartermaster Arthur Holloman was killed during WW1 on the 12th December 1916, whilst serving in France with the 1st Field Ambulance of the Royal Army Medical Corps.

After the death of his father, Fred left the Army Camp at Bulford with his mother and brother and moved to the east end of London. He went to school in Plaistow, leaving at the age of fourteen to take up an apprenticeship in metal engraving. Fred did not enjoy his first job and quickly gave it up in order to work for his mother at her public house in Limehouse and later another pub in West Ham.

Fred received his call up papers in late 1940 and these came as rather a shock to the 26 year old publican's assistant. His brother was posted to the Pioneer Corps and began his Army life clearing away the bomb-blasted buildings of the London Blitz. Meanwhile, Fred had been sent to join the 13th Battalion of the King's (Liverpool) Regiment at the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow. He undertook three months of basic infantry training at Jordan Hill, before the battalion were posted to Clacton-on-Sea in Essex. Here the 13th King's performed coastal defence duties, in preparation against the expected German sea-born invasion.

Over the coming year the 13th King's moved around the the south-eastern counties of England, taking up postings at Ipswich, Colchester and Felixstowe. By the middle of 1941, the battalion were sent to Market Harborough in Leicestershire, where they carried out farming work, preparing the fields for new crops and receiving for their trouble an extra shilling per day over and above their Army wages. Working on the land had another benefit according to Fred, who remembered with great relish the grand assortment of fruit and vegetables available on the farms, which were a far cry from the Army rations the men had been used to previously.

In November 1941, the 13th King's moved to an Army camp located just outside Blackburn in Lancashire. The move to Blackburn had been cloaked in secrecy and had intrigued the battalion. At the end of the month the men were told to prepare for a move to Liverpool and overseas service, destination unknown. On the 7th December, the men boarded the troopship Oronsay at the Victoria Docks in Liverpool and sailed the following day north to Greenock in Scotland. Here they formed up into convoy and moved out into the North Atlantic heading west for a few days, before dropping south towards the Azores. Fred found life below decks very claustrophobic and uncomfortable. The Other Ranks form the battalion were billeted in the lower decks of the vessel and close to the smell and noise of the ships engines. Many men including Pte. Holloman suffered with sea sickness in these early days of the voyage.

On Christmas Day 1941, the Oronsay docked just outside Freetown, Sierra Leone and the vessel was re-stocked for the onward journey. No shore-leave was granted at Freetown, but a week or so later, when the the ship docked at Durban in South Africa the men were allowed off the troopship for the first time. Many of the men including Fred, were amazed at the generosity of the local population, who met the British soldiers at the quayside and took them off to their homes and cooked the men sumptuous meals, involving food that many of the English lads had not seen or tasted for several years. Fred Holloman in his audio memoir, recorded at the Imperial War Museum in December 1996, described Durban as: the land of milk and honey.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The 13th King's disembarked at Bombay and were immediately taken by train to Secunderabad and their new home for the duration, Gough Barracks. The battalion settled down at Secunderabad taking on duties including internal security, policing and transportation of personnel and equipment. Fred Holloman was employed mostly as a driver, delivering stores all around the local area and occasionally further afield. The battalion remained at Secunderabad for approximately five months, until as Fred himself puts it: We had settled down pretty well at Gough Barracks, but then Wingate collared us.

The 13th King's became the British infantry element for Orde Wingate's first Chindit expedition in July 1942 and travelled to the Central Provinces of India to join the rest of 77 Brigade at the Saugor training camp. Training comprised of compass use, map reading, watercraft and swimming, living off the land and continuous marches across the arid plains and scrublands in Central India. The marches were arduous and designed to weed out the weak of mind as well as the unfit soldier. Failure to complete these long marches meant the end of your chance to take part in the forthcoming expedition. It is said that each man was offered the chance to leave the training camp if he felt he was not able to complete the extremely testing regime. Nobody took up this option of his own choosing.

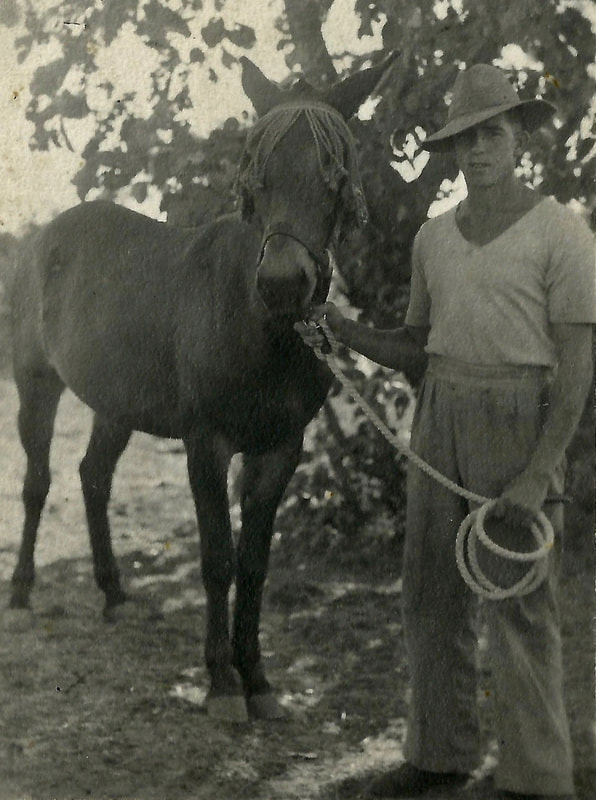

Due to Fred's recent duties in transportation, he was posted to Brigade Head Quarters and began a twelve week course in mule handling. At first he disliked this new role working with these stubborn and sometimes aggressive animals, but in time he grew to respect and admire them. Most of the mules were first class animals previously used by the Royal Signals. Fred remembered his own mule, Betty, who had the cross-flagged branding of the Royal Signals on her withers. Betty was now Fred's responsibility and the two slowly learned to love each other. Fred recalled how Betty used to nibble at his backside when ever he groomed her and how she sulked for days after being branded for a second time with her operational number.

Fred and Betty's job on Operation Longcloth was to carry the wireless set for Brigade HQ, an extraordinarily important role indeed. The set weighed approximately 60 pounds, which included not only the wireless set, but two very heavy charging batteries. Brigade HQ was made up of around 250 personnel, including a platoon of Commandos, Signallers, a Gurkha Defence platoon and an RAF section who were responsible for arranging and directing supply drops. Fred remembered losing his water bottle during the crossing of the Chindwin River and having to use a large bamboo cane cut into the shape of a flask for the following three weeks until a new bottle was delivered as part of a supply drop.

Fred worked under the leadership of Lt. Spurlock of the Royal Corps of Signals. He was offered a promotion to Corporal by Spurlock during the operation, but refused this, preferring to remain as a Private soldier. He recalled how the Signallers were always the last group to rest up for the night at column halts in the jungle. This was because their job at the end of each day was to report the Brigade's position to Rear Base and organise orders for the other columns in preparation for the following day.

At times during the long marches through the Burmese jungle, Brigadier Wingate would stand out of line and watch the column move past. On one occasion he stopped a Lance Corporal Clerk who was audibly complaining about having to carry the large stock of silver rupees held by the Brigade. On being challenged about this by Wingate, the angry soldier raised his rifle at his commander in a rather aggressive manner. Wingate had him tied to a tree for a few hours as punishment and to cool down no doubt, before having him released without further charge.

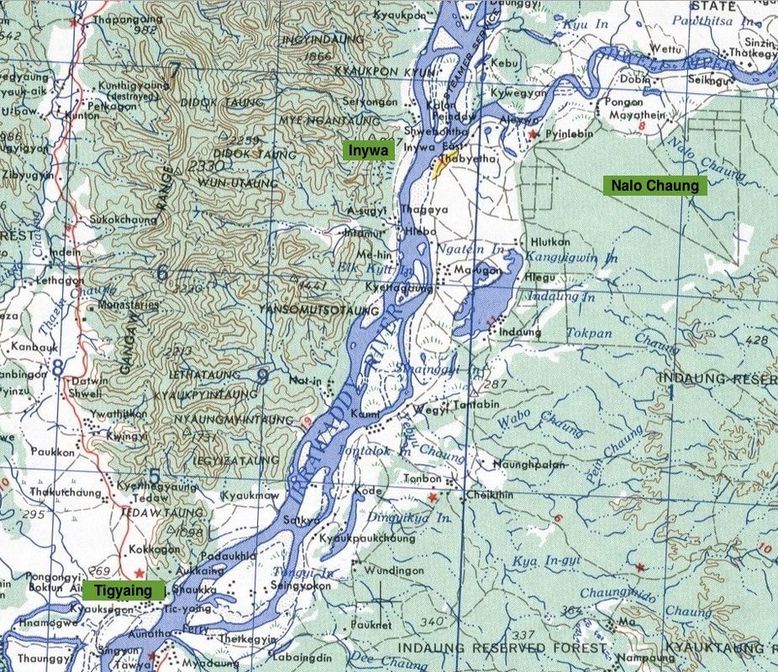

By around the 10th March, the Chindit columns were all preparing to cross over the Irrawaddy River for the first time. Brigade HQ crossed at a place called Inywa, where the Irrawaddy meets the Shweli River at their confluence. Sadly, it was at this juncture that Fred lost his beloved Betty when her tethers became entangled with those of several other mules and they were all washed away downstream and drowned.

Seen below is another gallery of images, please click on any photograph to bring it forward on the page.

The 13th King's became the British infantry element for Orde Wingate's first Chindit expedition in July 1942 and travelled to the Central Provinces of India to join the rest of 77 Brigade at the Saugor training camp. Training comprised of compass use, map reading, watercraft and swimming, living off the land and continuous marches across the arid plains and scrublands in Central India. The marches were arduous and designed to weed out the weak of mind as well as the unfit soldier. Failure to complete these long marches meant the end of your chance to take part in the forthcoming expedition. It is said that each man was offered the chance to leave the training camp if he felt he was not able to complete the extremely testing regime. Nobody took up this option of his own choosing.

Due to Fred's recent duties in transportation, he was posted to Brigade Head Quarters and began a twelve week course in mule handling. At first he disliked this new role working with these stubborn and sometimes aggressive animals, but in time he grew to respect and admire them. Most of the mules were first class animals previously used by the Royal Signals. Fred remembered his own mule, Betty, who had the cross-flagged branding of the Royal Signals on her withers. Betty was now Fred's responsibility and the two slowly learned to love each other. Fred recalled how Betty used to nibble at his backside when ever he groomed her and how she sulked for days after being branded for a second time with her operational number.

Fred and Betty's job on Operation Longcloth was to carry the wireless set for Brigade HQ, an extraordinarily important role indeed. The set weighed approximately 60 pounds, which included not only the wireless set, but two very heavy charging batteries. Brigade HQ was made up of around 250 personnel, including a platoon of Commandos, Signallers, a Gurkha Defence platoon and an RAF section who were responsible for arranging and directing supply drops. Fred remembered losing his water bottle during the crossing of the Chindwin River and having to use a large bamboo cane cut into the shape of a flask for the following three weeks until a new bottle was delivered as part of a supply drop.

Fred worked under the leadership of Lt. Spurlock of the Royal Corps of Signals. He was offered a promotion to Corporal by Spurlock during the operation, but refused this, preferring to remain as a Private soldier. He recalled how the Signallers were always the last group to rest up for the night at column halts in the jungle. This was because their job at the end of each day was to report the Brigade's position to Rear Base and organise orders for the other columns in preparation for the following day.

At times during the long marches through the Burmese jungle, Brigadier Wingate would stand out of line and watch the column move past. On one occasion he stopped a Lance Corporal Clerk who was audibly complaining about having to carry the large stock of silver rupees held by the Brigade. On being challenged about this by Wingate, the angry soldier raised his rifle at his commander in a rather aggressive manner. Wingate had him tied to a tree for a few hours as punishment and to cool down no doubt, before having him released without further charge.

By around the 10th March, the Chindit columns were all preparing to cross over the Irrawaddy River for the first time. Brigade HQ crossed at a place called Inywa, where the Irrawaddy meets the Shweli River at their confluence. Sadly, it was at this juncture that Fred lost his beloved Betty when her tethers became entangled with those of several other mules and they were all washed away downstream and drowned.

Seen below is another gallery of images, please click on any photograph to bring it forward on the page.

From the book, Beyond the Chindwin, by Bernard Fergusson commander of No. 5 Column on Operation Longcloth:

With hindsight, the decision to cross the Irrawaddy was a mistake. Our troubles arose from the fact that all seven columns eventually found themselves, in late March and early April, in a great bag formed by two wide rivers – the Irrawaddy and the Shweli – and across the mouth of this bag ran a motor road. The Japanese were able to bring up substantial reinforcements to patrol the road, to confiscate all the boats they could find on the rivers, and to occupy all the villages where we hoped to victual and many of the columns, like my own, had lost in action the wireless sets on which we depended for supplies from the air.

In the end Wingate decided to cancel the expedition on the 24th March and ordered all remaining Chindit columns to return to India. On dispersal Brigade HQ reached the Irrawaddy for a second time close to the village of Inywa. On the 29th March, the first boats set off from the east bank in order to form a bridgehead on the other side. However, a large Japanese patrol attacked these bridgehead boats, killing a great number of the Chindits contained within them. The crossing was duly abandoned and Wingate called an officers conference where it was decided to split Brigade HQ up into five dispersal parties.

Fred Holloman was placed into the dispersal group led by, Captain Graham Hosegood the Intelligence Officer and Lt. Willy' Wilding, the Brigade's Cipher Officer. Wingate's decision to break his column up at this point did not go down too well with some of the other soldiers present at the Irrawaddy. Pte. Leonard Coffin of the King's Regiment, openly remarked within earshot of the Brigadier, that he felt this was a case of the rats deserting a sinking ship. Wingate said nothing in reply and moved away with his party.

Around the beginning of April 1943, several hundred exhausted and desperate Chindits were searching for a way to cross either the Irrawaddy or Shweli Rivers. Four out of the five dispersal groups from Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters were drifting back and forth along the Irrawaddy's eastern shoreline, in the hope of finding a native boat and a safe crossing point. Very few succeeded in this quest.

Fred's party suffered more than most as they struggled to cross over this seemingly insurmountable obstacle. Lt. Wilding, in his own writings recalled those desperate weeks:

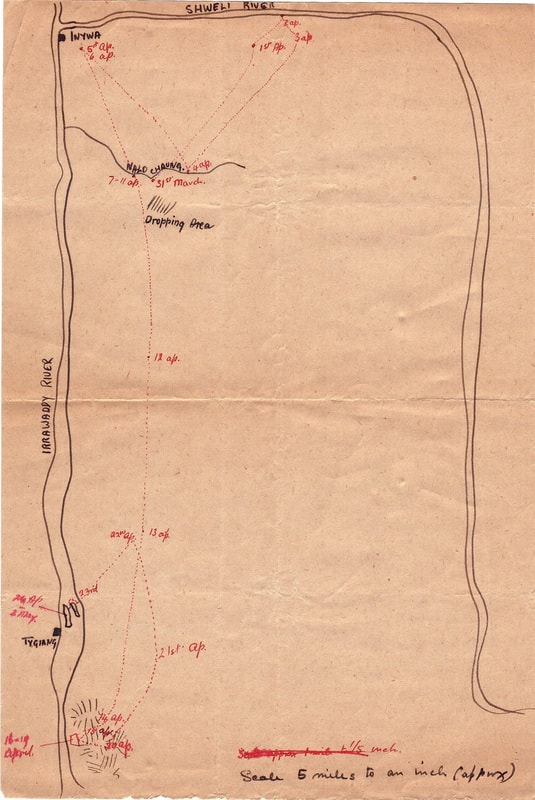

2nd April: Marched back towards Inywa village, needed water that we knew we could get from a dried up riverbed called the Nalo Chaung (see maps below). A very nasty march of 10-12 miles.

3rd April: Hoped that the Japs had abandoned Inywa, so decided to try there again today; got within a couple of miles and sent the Burma Riflemen off to make a recce. Waited all day and the next, with insufficient water.

4th April: The Burmese returned late in the day, without one soldier who had been injured and captured. Needed water, so set off again on the 5th for Nalo Chaung, only just making it.

6th April: Rations low and we still have a long way to go. 2/Lt. Pat Gordon took a party to the last ration drop in the hope of finding something, came back with 15 days rations per man. This gave us 17 days rations each, but some of the men couldn’t even carry the load. Stayed here for the 7th and 8th, intending to set out on the 9th. Planned to move southeast and make individual rafts, strong enough to carry a rifle, boots and pack and cross the Irrawaddy supported by these.

9th April: A party of men set out to get water. Returned with one man short (Simons), assumed he had got lost and would be taken captive and made to talk. Decided we could afford to wait three days, then put our plan into action. 9th, 10th and 11th April stayed put, eating slightly more than a days rations each day to reduce the load to 10 days.

12th April: Set off and covered 10 miles, found a stream, superior to the muddy pools of the Nalo Chaung. Bivouacked near here and then found we had bivouacked within 50 yards of a track much used by the Japs.

13th April: Early start to get over the road before traffic started moving, marched well clear of the road, lay up to continue our journey by night. Laid an ambush as heard bells that we thought were on the necks of elephants used by the Japs, turned out to be two buffalo out to graze.

14th April: Night marching has not proved very sensible, so marched by day.

15th April: Left thick jungle behind us and headed due west towards Tigyiang where we intended to launch the rafts. Found a good sight on a hill top with a spring and plenty of bamboo to make the rafts.

16th and 17th April: Most made rafts while a small party went to recce a route to the river. Three days rations left, enough to reach the Meza Valley, where we expected to find friendly villagers who would sell us food.

18th April: Recce party returned and said it was practicable to get to river, so raft making continued.

19th and 20th April: Struggled out of the swamp, tried to find a bit of dry land to dry our clothes. Irrawaddy idea abandoned, thought we could go east, cross the Shweli, where it was only a stream, swing north and go into Kachin country, and there sweat out the monsoon. Riflemen Tunnion and Orlando thought that their home villages would put us up for the duration. It was only 80 miles and we thought we could make it.

21st April: There was hardly any food left so first decided to raid a village, where we in fact bought food. In a change of plan, the Headman promised to put us over the Irrawaddy for a considerable price in silver rupees. He and his brother took us to the river at a racing speed; we had no idea where we were. It was night before we finally embarked, paddled around one island and then disembarked, handed over nearly all our money and set out for the hills, only to find a wide stretch of water between us and the hills. It was the main river! We had been betrayed.

NB. In his audio memoir Fred Holloman remembered these Burmese villagers and had this to say:

In relation to these villagers, I smelled a rat myself as the boatmen were speaking loudly and smoking cigars. They were far too relaxed for my liking especially as we had paid them over 100 silver rupees.

22nd - 28th April: (Wilding continues). The next six days are very confused in my mind, searched the island which was about a mile long and ½ mile wide. Finished the last of the rations on the 23rd, some villagers gave us one meal for a payment. Tried launching one decrepit boat but it sank.

29th April: Found another boat, which floated, so decided a small group would take the first trip and see what could be done, most of them were killed on reaching the other side. Decided to break into small parties and hide in the elephant grass for three days and to rendezvous at the old bivouac at sunset on the 3rd day.

NB. Fred Holloman recalled that it was Captain Hosegood who decided to break everyone up into small groups of two or three men on the 29th April. On returning to the rendezvous location three days later, Fred and his two comrades never saw Hosegood again until they all met up as prisoners of war in Rangoon Jail.

30th April - 2nd May: (Wilding continues). Very tired and hungry no food since the 23rd, had nothing to eat for six days. Thought up dozens of plans each as impracticable as the next, left with two choices, to fight or surrender. I am confident the men would fight if ordered to, but only had one working rifle between us all. The only rifle that was working was because L/Cpl. Willis had used mosquito cream as lubricant. We didn’t even have bayonets, so we had no choice, went into a village and gave ourselves up. The Japanese were away from the village searching for us. The Burmese tied us up rather cruelly with bark string and held us for many hours. It is a frightful thing to become a POW. You have failed, you have lost you liberty and you have a nagging feeling that you should have done better.

Lt. Wilding concludes:

When the Japs returned they were really quite decent, they released the tight bonds around our hands and let us sleep for 24 hours. We then were taken to Tigyaing where we stayed in the schoolhouse and were given three meals of curried chicken and rice each day. This would be the only time we were adequately fed during our captivity.

Shortly afterwards we set out for Wuntho on the railway, a village Brigade had proposed attacking only six weeks previously. Shortly afterwards we set out for Maymyo. An uncomfortable rail journey saw us pass through Sagaing and from there to the Dufferin Fort via the Ava Bridge which spanned the Irrawaddy. The bridge was still in disrepair after it had been blown to blazes by the RAF. We crossed the river in a sort of barge followed by a dreadful march to Mandalay and finally another train to Maymyo. Maymyo was the hill station for Mandalay, probably a lovely place in peacetime, but it was a hell camp for us prisoners, where we were expected to learn Japanese drill. We were put into open fronted sheds, which used to be the servants quarters for the well to do. We remained at Maymyo for about two weeks, but it seemed like an eternity.

To read more about the Maymyo Concentration Camp and the experiences of the captured Chindits during their time there, please click on the following link: Maymyo Camp

Below is a third gallery of images, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

With hindsight, the decision to cross the Irrawaddy was a mistake. Our troubles arose from the fact that all seven columns eventually found themselves, in late March and early April, in a great bag formed by two wide rivers – the Irrawaddy and the Shweli – and across the mouth of this bag ran a motor road. The Japanese were able to bring up substantial reinforcements to patrol the road, to confiscate all the boats they could find on the rivers, and to occupy all the villages where we hoped to victual and many of the columns, like my own, had lost in action the wireless sets on which we depended for supplies from the air.

In the end Wingate decided to cancel the expedition on the 24th March and ordered all remaining Chindit columns to return to India. On dispersal Brigade HQ reached the Irrawaddy for a second time close to the village of Inywa. On the 29th March, the first boats set off from the east bank in order to form a bridgehead on the other side. However, a large Japanese patrol attacked these bridgehead boats, killing a great number of the Chindits contained within them. The crossing was duly abandoned and Wingate called an officers conference where it was decided to split Brigade HQ up into five dispersal parties.

Fred Holloman was placed into the dispersal group led by, Captain Graham Hosegood the Intelligence Officer and Lt. Willy' Wilding, the Brigade's Cipher Officer. Wingate's decision to break his column up at this point did not go down too well with some of the other soldiers present at the Irrawaddy. Pte. Leonard Coffin of the King's Regiment, openly remarked within earshot of the Brigadier, that he felt this was a case of the rats deserting a sinking ship. Wingate said nothing in reply and moved away with his party.

Around the beginning of April 1943, several hundred exhausted and desperate Chindits were searching for a way to cross either the Irrawaddy or Shweli Rivers. Four out of the five dispersal groups from Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters were drifting back and forth along the Irrawaddy's eastern shoreline, in the hope of finding a native boat and a safe crossing point. Very few succeeded in this quest.

Fred's party suffered more than most as they struggled to cross over this seemingly insurmountable obstacle. Lt. Wilding, in his own writings recalled those desperate weeks:

2nd April: Marched back towards Inywa village, needed water that we knew we could get from a dried up riverbed called the Nalo Chaung (see maps below). A very nasty march of 10-12 miles.

3rd April: Hoped that the Japs had abandoned Inywa, so decided to try there again today; got within a couple of miles and sent the Burma Riflemen off to make a recce. Waited all day and the next, with insufficient water.

4th April: The Burmese returned late in the day, without one soldier who had been injured and captured. Needed water, so set off again on the 5th for Nalo Chaung, only just making it.

6th April: Rations low and we still have a long way to go. 2/Lt. Pat Gordon took a party to the last ration drop in the hope of finding something, came back with 15 days rations per man. This gave us 17 days rations each, but some of the men couldn’t even carry the load. Stayed here for the 7th and 8th, intending to set out on the 9th. Planned to move southeast and make individual rafts, strong enough to carry a rifle, boots and pack and cross the Irrawaddy supported by these.

9th April: A party of men set out to get water. Returned with one man short (Simons), assumed he had got lost and would be taken captive and made to talk. Decided we could afford to wait three days, then put our plan into action. 9th, 10th and 11th April stayed put, eating slightly more than a days rations each day to reduce the load to 10 days.

12th April: Set off and covered 10 miles, found a stream, superior to the muddy pools of the Nalo Chaung. Bivouacked near here and then found we had bivouacked within 50 yards of a track much used by the Japs.

13th April: Early start to get over the road before traffic started moving, marched well clear of the road, lay up to continue our journey by night. Laid an ambush as heard bells that we thought were on the necks of elephants used by the Japs, turned out to be two buffalo out to graze.

14th April: Night marching has not proved very sensible, so marched by day.

15th April: Left thick jungle behind us and headed due west towards Tigyiang where we intended to launch the rafts. Found a good sight on a hill top with a spring and plenty of bamboo to make the rafts.

16th and 17th April: Most made rafts while a small party went to recce a route to the river. Three days rations left, enough to reach the Meza Valley, where we expected to find friendly villagers who would sell us food.

18th April: Recce party returned and said it was practicable to get to river, so raft making continued.

19th and 20th April: Struggled out of the swamp, tried to find a bit of dry land to dry our clothes. Irrawaddy idea abandoned, thought we could go east, cross the Shweli, where it was only a stream, swing north and go into Kachin country, and there sweat out the monsoon. Riflemen Tunnion and Orlando thought that their home villages would put us up for the duration. It was only 80 miles and we thought we could make it.

21st April: There was hardly any food left so first decided to raid a village, where we in fact bought food. In a change of plan, the Headman promised to put us over the Irrawaddy for a considerable price in silver rupees. He and his brother took us to the river at a racing speed; we had no idea where we were. It was night before we finally embarked, paddled around one island and then disembarked, handed over nearly all our money and set out for the hills, only to find a wide stretch of water between us and the hills. It was the main river! We had been betrayed.

NB. In his audio memoir Fred Holloman remembered these Burmese villagers and had this to say:

In relation to these villagers, I smelled a rat myself as the boatmen were speaking loudly and smoking cigars. They were far too relaxed for my liking especially as we had paid them over 100 silver rupees.

22nd - 28th April: (Wilding continues). The next six days are very confused in my mind, searched the island which was about a mile long and ½ mile wide. Finished the last of the rations on the 23rd, some villagers gave us one meal for a payment. Tried launching one decrepit boat but it sank.

29th April: Found another boat, which floated, so decided a small group would take the first trip and see what could be done, most of them were killed on reaching the other side. Decided to break into small parties and hide in the elephant grass for three days and to rendezvous at the old bivouac at sunset on the 3rd day.

NB. Fred Holloman recalled that it was Captain Hosegood who decided to break everyone up into small groups of two or three men on the 29th April. On returning to the rendezvous location three days later, Fred and his two comrades never saw Hosegood again until they all met up as prisoners of war in Rangoon Jail.

30th April - 2nd May: (Wilding continues). Very tired and hungry no food since the 23rd, had nothing to eat for six days. Thought up dozens of plans each as impracticable as the next, left with two choices, to fight or surrender. I am confident the men would fight if ordered to, but only had one working rifle between us all. The only rifle that was working was because L/Cpl. Willis had used mosquito cream as lubricant. We didn’t even have bayonets, so we had no choice, went into a village and gave ourselves up. The Japanese were away from the village searching for us. The Burmese tied us up rather cruelly with bark string and held us for many hours. It is a frightful thing to become a POW. You have failed, you have lost you liberty and you have a nagging feeling that you should have done better.

Lt. Wilding concludes:

When the Japs returned they were really quite decent, they released the tight bonds around our hands and let us sleep for 24 hours. We then were taken to Tigyaing where we stayed in the schoolhouse and were given three meals of curried chicken and rice each day. This would be the only time we were adequately fed during our captivity.

Shortly afterwards we set out for Wuntho on the railway, a village Brigade had proposed attacking only six weeks previously. Shortly afterwards we set out for Maymyo. An uncomfortable rail journey saw us pass through Sagaing and from there to the Dufferin Fort via the Ava Bridge which spanned the Irrawaddy. The bridge was still in disrepair after it had been blown to blazes by the RAF. We crossed the river in a sort of barge followed by a dreadful march to Mandalay and finally another train to Maymyo. Maymyo was the hill station for Mandalay, probably a lovely place in peacetime, but it was a hell camp for us prisoners, where we were expected to learn Japanese drill. We were put into open fronted sheds, which used to be the servants quarters for the well to do. We remained at Maymyo for about two weeks, but it seemed like an eternity.

To read more about the Maymyo Concentration Camp and the experiences of the captured Chindits during their time there, please click on the following link: Maymyo Camp

Below is a third gallery of images, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In his memoir, Fred Holloman agrees with Lt. Wilding in relation to the treatment meted out by the Japanese soldiers who actually captured the Chindits at the Irrawaddy. He mentions another man, Pte. Timothy Campbell, who had been Captain Hosegood's batman on Operation Longcloth and how due to the fact that he had been wearing a crucifix when captured, a Japanese soldier of Catholic persuasion had noticed this and given the Chindt POW's extra rations on the journey to Maymyo.

At Maymyo, Fred remembered being treated harshly by the Japanese and Korean guards. He recalled: At Maymyo we were taught Japanese language, numbers and discipline and had to perform Shinto prayers each day in front of a shrine. Eventually we moved down from Maymyo to Rangoon Jail where we were kept in Block No. 6. We were ordered to do slave labour and paid a penny a day towards our rations. We built bomb shelters for the Japs and worked down at the docks, loading and unloading cargo from the ships.

Fred recalled the story of Corporal Hardy of the King's Regiment and his sad demise in Rangoon Jail. At one tenko, or roll call, it was noticed by the British officers that Hardy was missing, but this omission was not noticed by the Japanese guard.

Captain Hosegood was temporarily in charge of this section of the jail at that time, because the senior officer was sick in hospital. Hosegood assumed that Hardy must also be in the makeshift hospital and listed him down on the tenko sheet as having dysentery. Eventually, when Hardy could not be found anywhere inside the jail, Captain Hosegood had to come clean to the Japs and received a severe beating for his troubles. The whole block was then locked up for a week as punishment. After several days, Fred was told by one of the more friendly guards that Hardy had been found wandering around in the streets a few miles from the prison and that it was obvious that he was delirious and suffering from acute cerebral malaria. Nevertheless, as an example to all the other prisoners, Corporal Hardy was shot by a firing squad even though the Japanese knew he was a seriously ill man.

At Maymyo, Fred remembered being treated harshly by the Japanese and Korean guards. He recalled: At Maymyo we were taught Japanese language, numbers and discipline and had to perform Shinto prayers each day in front of a shrine. Eventually we moved down from Maymyo to Rangoon Jail where we were kept in Block No. 6. We were ordered to do slave labour and paid a penny a day towards our rations. We built bomb shelters for the Japs and worked down at the docks, loading and unloading cargo from the ships.

Fred recalled the story of Corporal Hardy of the King's Regiment and his sad demise in Rangoon Jail. At one tenko, or roll call, it was noticed by the British officers that Hardy was missing, but this omission was not noticed by the Japanese guard.

Captain Hosegood was temporarily in charge of this section of the jail at that time, because the senior officer was sick in hospital. Hosegood assumed that Hardy must also be in the makeshift hospital and listed him down on the tenko sheet as having dysentery. Eventually, when Hardy could not be found anywhere inside the jail, Captain Hosegood had to come clean to the Japs and received a severe beating for his troubles. The whole block was then locked up for a week as punishment. After several days, Fred was told by one of the more friendly guards that Hardy had been found wandering around in the streets a few miles from the prison and that it was obvious that he was delirious and suffering from acute cerebral malaria. Nevertheless, as an example to all the other prisoners, Corporal Hardy was shot by a firing squad even though the Japanese knew he was a seriously ill man.

Fred Holloman remembered being punched and slapped many times during his time as a prisoner of war. On most occasions this would be on the whim of an angry Japanese guard, who had deemed that a POW had committed some minor misdemeanour such as forgetting to bow in his presence. Fred also suffered from dysentery whilst in Rangoon Jail and was treated at first with burnt rice followed by a starvation diet, drinking only green tea. This sadly resulted in him losing his appetite completely and after contracting malaria as an added complication his health began to deteriorate very quickly.

During this time he had been working in Rangoon city where he manned a searchlight position, used for picking out Allied planes as they came over in bombing raids in late 1944 and early 1945. This searchlight was located close to an onion field and from which Fred stole a number of small onions, smuggling them into the jail inside his mess tin. He mixed the onions with his rice and maze rations which made these just palatable enough to get down.

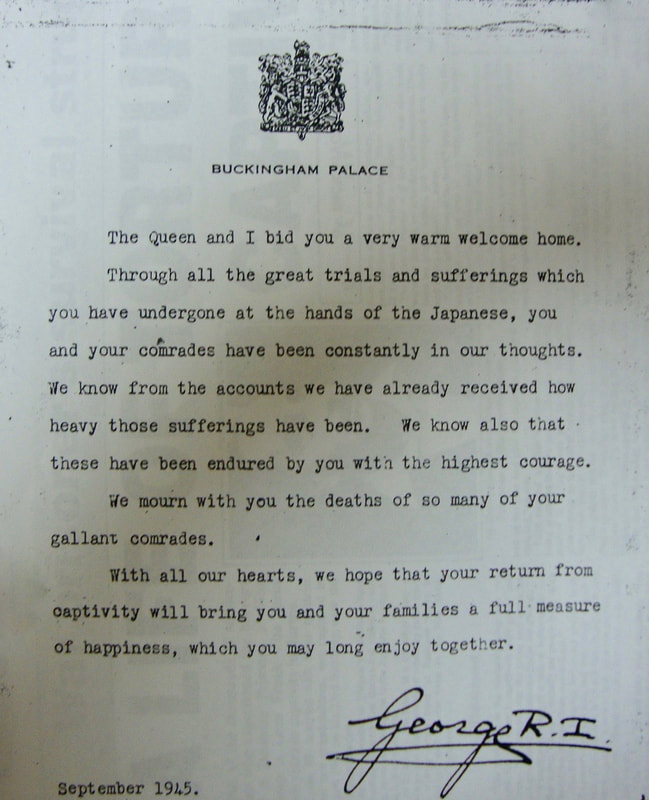

As the tide of the war began to turn against the Japanese in April 1945, they decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 men were classified as fit to march and on the 24th April were marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and ill comrades. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, the marchers were north of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge when they ran into the 14th Army. The Japanese Commandant released them in a village called Waw telling them they were free men and then disappeared with the rest of his guards. The now liberated prisoners were situated in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. That night they managed to contact some troops from the West Yorkshire Regiment and were taken to the safety of Allied held territory.

Fred recalled: On the forced march we travelled around 10 miles a day, but began to be attacked by RAF along the Pegu Road. At the village of Waw the RAF machine-gunned us when we were laid up in a wooded copse. Brigadier Hobson, our most senior officer was killed. American POW, Major Charles Lutz managed to contact Allied forces and we were liberated. I was flown out of Burma by Dakota to Comilla and went straight into hospital. Before Operation Longcloth I had been over 11 stone in weight and 5 foot 7 inches tall, by the end of April 1945, I weighed just 96 pounds.

Fred mentioned in his memoir that he felt the Japanese were a rather cruel race during the years of WW2 and that it is difficult to forgive them for their treatment of Allied prisoners of war. He reflected on whether not taking the promotion offered to him by Lt. Spurlock in March 1943, had rather guaranteed his eventual capture by the Japanese in Burma, instead of returning safely to India as part of Brigadier Wingate's dispersal group. Fred did not think much of the first Wingate expedition, saying that in his opinion it achieved very little apart from a couple of demolitions along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway and some minor disruption to Japanese plans and communications.

After the war, a strong veterans group was formed by the survivors of Rangoon Jail. This included many reunions held both in the United Kingdom and the United States. There was also a regular newsletter, The Rangoon Ramblings, organised and distributed by one of the American prisoners held in the jail from late 1944, Staff Sergeant Karnig Thomasian.

On the 5th February 1988, a local newspaper carried the following report on one of the Rangoon Jail reunions, held on this occasion in London:

Hello Again!

Two old soldiers who were held captive by the Japanese at the same prisoner-of-war camp in Burma, have been re-united more than 40 years after they were liberated. Leon Frank, from Highams Park, who is Jewish, and Fred Holloman, from Walthamstow, served in the 13th Battalion, the King's Liverpool Regiment and were part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, under the command of the then Brigadier, Orde Wingate.

Together, they crossed into Burma from India on a sabotage mission against Japanese front line troops. However, the Japanese offensive proved too strong and Leon and Fred were captured on April 21st (Leon's 23rd birthday) and the 2nd May 1943.

At first they were imprisoned in an old British leave station (Maymyo) in wooden huts, on the Burmese-Chinese border, and later transferred to a camp in Rangoon. Leon, now 67, recalled: "Out of 200 captives only 20 of us survived. I had every disease going, from malaria to dysentery and beri beri, but I was determined to survive. The big fellows died sometimes because they needed more food, but I am small and didn't need much."

Leon and Fred never gave up during their harsh ordeal and after two more years, on April 30th, 1945, they were liberated by Allied soldiers. The POW's were split up and never saw each other again, until they read a story in their local paper, appealing for soldiers to contact an organisation trying to reunite wartime comrades.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to the above narrative. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Epilogue: In later life, Fred Holloman moved from Walthamstow to the west country of England, where in October 2001 he sadly passed away whilst living in Torbay, Devon.

Epilogue: In later life, Fred Holloman moved from Walthamstow to the west country of England, where in October 2001 he sadly passed away whilst living in Torbay, Devon.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2018.