Medical Services to Operation Longcloth

Insignia of the Royal Army Medical Corps.

Insignia of the Royal Army Medical Corps.

This is the story of the Medical staff, who in one form or another tended the men of 77th Indian Infantry Brigade during its existence, from the formative months in India until the last Longcloth POW was liberated from Rangoon Jail and hospitalised at the 142nd Indian General Hospital based in Calcutta.

As has already been mentioned on the pages of this website, many of the original members of the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment, those that voyaged to India aboard the troopship Oronsay in late 1941, were found wanting in fitness or health to ultimately take part on the first Wingate expedition. These men were checked over by the medical staff at the training camps at Saugor and Patharia and after assessment, sent away to take up duties in other units all over India and the wider sub-continent.

The men who survived the exacting training regime were allocated to one of the Chindit columns and from that moment came under the care of the individual column Medical Officers.

Here is what I know about the Medical Officers from 77th Brigade in 1943 and what happened to them on Operation Longcloth.

(NB. Each column was provided with one Medical Officer and 3 Medical Orderlies).

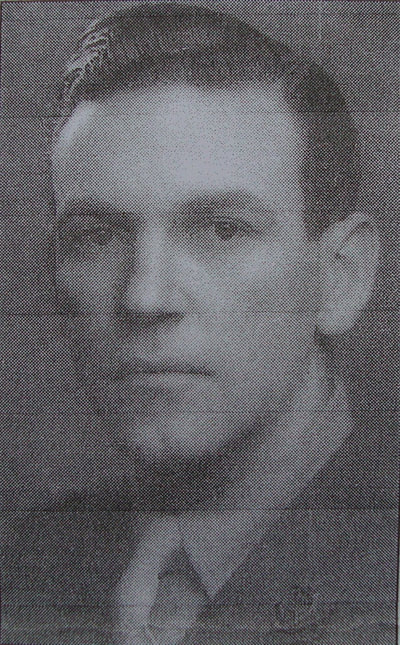

Major Raymond Ramsey, was the chief Medical officer on Operation Longcloth and served in Wingate's Head Quarters Brigade. Admired and looked up to by many of the young officers in 1943, the Major was barely 30 years old himself. He led one of the dispersal groups in an attempt to reach the safety of India in April 1943. He and Captain Arthur Moxham were taken prisoner by the Japanese on the 11th May and sent to Rangoon Jail, where Major Ramsay became the senior medical officer (an honour he shared with Colonel KP MacKenzie, who had been captured in 1942) and treated many of the sick and wounded Chindit POW's. On arrival in Rangoon he was detained in solitary confinement by the Japanese for nearly five weeks. Here is a quote from the memoirs of Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding on the same subject:

"It was a disgrace that Major Ramsay was kept in solitary for so long, whilst our men were dying at a rate of at least one a day. Words cannot convey enough praise for his work, his devotion and his gentleness towards the men. Later they gave him an MBE just as if he had been a 'Beatle'. Never was a man's work so grossly undervalued by the top Brass, though he was never undervalued by us!"

After the war Dr. Ramsay continued his career in medicine, including sterling work at St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London. Click on the link below to see Major Ramsay's MBE announcement in the London Gazette on 6th June 1946:

http://www.gazettes-online.co.uk/issues/37595/supplements/2736/page.pdf

To read more about Raymond Ramsay and his experiences in Burma, please click on the following link: Raymond Ramsay

Captain Norman Fraser Stocks. Medical Officer for No. 1Column, he is mentioned in the Column war diary written by Major George Dunlop and in the book Safer Than a Known Way, written by the Gurkha Officer Ian MacHorton. Captain Stocks also gives evidence in the Court of Enquiry into the accidental death of Lance Corporal Percy Finch, held at Jhansi on the 26th December 1942. For more details, please click on the following link: Percy Finch

To read more about Captain Stocks and his wartime experiences, please click on the following link: Norman Fraser Stocks

Captain George Ian Wilson Lusk was the Medical Officer for 2 Column. Having previously walked out of Burma in 1942, escaping the rapidly advancing Japanese invasion force, George bravely volunteered to go back in again the following year with Wingate's Chindits. Sadly this decision was to cost him his life, he was captured attempting to re-cross the Irrawaddy on dispersal on the 23rd April and died a POW just a few days later. Here are his CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2516046/george-ian-wilson-lusk/

Captain D. Rao, Medical Officer for 3 Column. Not much is known about Dr. Rao, apart from his devotion in keeping the Gurkha Rifles of 3 Column fit and well. He was part of Flight Officer Robert Thompson's dispersal group which finally exited Burma in mid-April. Here is a quote from Harold James's book, Across the Threshold of Battle, describing the Doctor:

"Our medical officer, Captain Rao came from Southern India, he was so thin that he looked as though he would snap in two at the slightest touch. In reality he was a very tough, good humoured and and excellent doctor. He had served with the British 17th Division on the retreat in 1942 and had seen the worst of that campaign. However, he would never let anything worry or depress him and he looked after our wounded with great compassion."

Update 05/12/2020.

I was delighted to find another small reference to Dr. Rao recently, contained in the written memoir of Lt. Willie Wilding, Wingate's Cipher Officer on Operation Longcloth:

In the time just before we set off into Burma, the Brigade was based at Imphal. My job at the time was bringing up supplies and materials for the expedition. On this occasion I was riding on the back of a truck, standing at the rear of the vehicle holding on to the tilt frame which holds the canvas cover. As the driver took a sharp bend I was flung to one side and dislocated my left shoulder. I had done this previously whilst playing rugger on various occasions and it was very painful.

We stopped the truck and I got out and sat sadly by the side of the road to await the arrival of a Medical Officer, who might reduce the dislocation. The journalists who were with us then came by and stopped. I was anxious not to be left behind when the Brigade went into Burma and I besought them to seek out the Brigadier and to persuade him that I was quite able to compete. Eventually a very pleasant Indian MO, Captain Rao came along. He told me that the shoulder had been out too long for it to be put back without an anaesthetic and he had a job to put me out there and then on the road. It was a wonderful relief to wake up later without serious pain.

When I arrived back at our camp, the Brigadier said I could still go in with the Brigade and that I need not carry a rifle and that for the first week and my pack could go on a mule. I was very relieved. It would have been dreadful to have been left behind.

Oddly enough I met Captain Rao who was by then a Lt-Colonel, not long before I left India for the UK in late 1945. I said something about the Chindits and he said rather stiffly that he had been a Chindit too. The penny dropped and I realised who he was and that he had kindly put my shoulder back in on the road to Tamu in February 1943. We went on to have a splendid evening.

As has already been mentioned on the pages of this website, many of the original members of the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment, those that voyaged to India aboard the troopship Oronsay in late 1941, were found wanting in fitness or health to ultimately take part on the first Wingate expedition. These men were checked over by the medical staff at the training camps at Saugor and Patharia and after assessment, sent away to take up duties in other units all over India and the wider sub-continent.

The men who survived the exacting training regime were allocated to one of the Chindit columns and from that moment came under the care of the individual column Medical Officers.

Here is what I know about the Medical Officers from 77th Brigade in 1943 and what happened to them on Operation Longcloth.

(NB. Each column was provided with one Medical Officer and 3 Medical Orderlies).

Major Raymond Ramsey, was the chief Medical officer on Operation Longcloth and served in Wingate's Head Quarters Brigade. Admired and looked up to by many of the young officers in 1943, the Major was barely 30 years old himself. He led one of the dispersal groups in an attempt to reach the safety of India in April 1943. He and Captain Arthur Moxham were taken prisoner by the Japanese on the 11th May and sent to Rangoon Jail, where Major Ramsay became the senior medical officer (an honour he shared with Colonel KP MacKenzie, who had been captured in 1942) and treated many of the sick and wounded Chindit POW's. On arrival in Rangoon he was detained in solitary confinement by the Japanese for nearly five weeks. Here is a quote from the memoirs of Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding on the same subject:

"It was a disgrace that Major Ramsay was kept in solitary for so long, whilst our men were dying at a rate of at least one a day. Words cannot convey enough praise for his work, his devotion and his gentleness towards the men. Later they gave him an MBE just as if he had been a 'Beatle'. Never was a man's work so grossly undervalued by the top Brass, though he was never undervalued by us!"

After the war Dr. Ramsay continued his career in medicine, including sterling work at St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London. Click on the link below to see Major Ramsay's MBE announcement in the London Gazette on 6th June 1946:

http://www.gazettes-online.co.uk/issues/37595/supplements/2736/page.pdf

To read more about Raymond Ramsay and his experiences in Burma, please click on the following link: Raymond Ramsay

Captain Norman Fraser Stocks. Medical Officer for No. 1Column, he is mentioned in the Column war diary written by Major George Dunlop and in the book Safer Than a Known Way, written by the Gurkha Officer Ian MacHorton. Captain Stocks also gives evidence in the Court of Enquiry into the accidental death of Lance Corporal Percy Finch, held at Jhansi on the 26th December 1942. For more details, please click on the following link: Percy Finch

To read more about Captain Stocks and his wartime experiences, please click on the following link: Norman Fraser Stocks

Captain George Ian Wilson Lusk was the Medical Officer for 2 Column. Having previously walked out of Burma in 1942, escaping the rapidly advancing Japanese invasion force, George bravely volunteered to go back in again the following year with Wingate's Chindits. Sadly this decision was to cost him his life, he was captured attempting to re-cross the Irrawaddy on dispersal on the 23rd April and died a POW just a few days later. Here are his CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2516046/george-ian-wilson-lusk/

Captain D. Rao, Medical Officer for 3 Column. Not much is known about Dr. Rao, apart from his devotion in keeping the Gurkha Rifles of 3 Column fit and well. He was part of Flight Officer Robert Thompson's dispersal group which finally exited Burma in mid-April. Here is a quote from Harold James's book, Across the Threshold of Battle, describing the Doctor:

"Our medical officer, Captain Rao came from Southern India, he was so thin that he looked as though he would snap in two at the slightest touch. In reality he was a very tough, good humoured and and excellent doctor. He had served with the British 17th Division on the retreat in 1942 and had seen the worst of that campaign. However, he would never let anything worry or depress him and he looked after our wounded with great compassion."

Update 05/12/2020.

I was delighted to find another small reference to Dr. Rao recently, contained in the written memoir of Lt. Willie Wilding, Wingate's Cipher Officer on Operation Longcloth:

In the time just before we set off into Burma, the Brigade was based at Imphal. My job at the time was bringing up supplies and materials for the expedition. On this occasion I was riding on the back of a truck, standing at the rear of the vehicle holding on to the tilt frame which holds the canvas cover. As the driver took a sharp bend I was flung to one side and dislocated my left shoulder. I had done this previously whilst playing rugger on various occasions and it was very painful.

We stopped the truck and I got out and sat sadly by the side of the road to await the arrival of a Medical Officer, who might reduce the dislocation. The journalists who were with us then came by and stopped. I was anxious not to be left behind when the Brigade went into Burma and I besought them to seek out the Brigadier and to persuade him that I was quite able to compete. Eventually a very pleasant Indian MO, Captain Rao came along. He told me that the shoulder had been out too long for it to be put back without an anaesthetic and he had a job to put me out there and then on the road. It was a wonderful relief to wake up later without serious pain.

When I arrived back at our camp, the Brigadier said I could still go in with the Brigade and that I need not carry a rifle and that for the first week and my pack could go on a mule. I was very relieved. It would have been dreadful to have been left behind.

Oddly enough I met Captain Rao who was by then a Lt-Colonel, not long before I left India for the UK in late 1945. I said something about the Chindits and he said rather stiffly that he had been a Chindit too. The penny dropped and I realised who he was and that he had kindly put my shoulder back in on the road to Tamu in February 1943. We went on to have a splendid evening.

Captain George V. Faulkner. The Medical Officer for Southern Group Head Quarters. To read more about his experiences on both Chindit expeditions, please click on the following link: George V. Faulkner

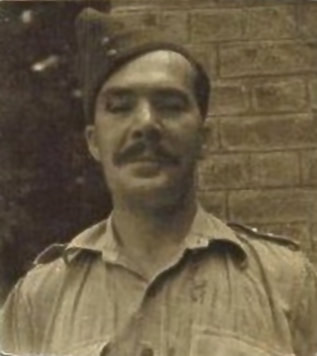

Captain William Service Aird, was the Medical Officer for 5 Column. Having begun his time with the Chindits serving with 142 Commando, William was 'poached' away from this unit by Bernard Fergusson and became 5 Column's doctor late in 1942. After agreeing to help look after a dispersal group of already ill and stricken men, William himself went down with malaria combined disastrously with a bout of severe dysentery. He was captured in late April, heartbreakingly just a few miles short of the Chindwin River and potential safety. He died less than ten days later, as the captured Chindit POW's passed through the town of Mandalay on their train journey down to Rangoon Jail.

You can read more about William Aird within these two website pages: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4 and Ted Stuart, Almost, but not Quite.

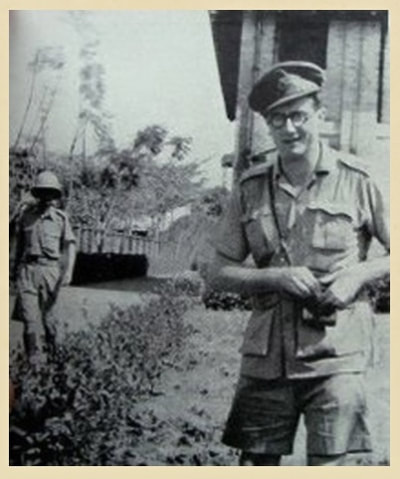

Captain Alfred Henry Snalam, was the Medical Officer for 7 Column. Alfred Snalam, affectionately known as 'Bill' is not mentioned in many of the war diaries or other paperwork in relation to Operation Longcloth. The information that follows was found on line and is taken from a short obituary written in a medical journal back in 1989.

Alfred was born on the 5th January 1914 at Ilkley in West Yorkshire. His latter schooldays were spent at Ilkley Grammar School before he chose to study medicine at Leeds University. Just before he began his studies for his degree, Alfred spent some time in Australia, travelling with William Snalam (presumably his father) to Brisbane in 1932. William and his eighteen year old son, Alfred, returned to the United Kingdom on the 22nd April 1932 aboard the SS Strathnaver. Coincidently, the Strathnaver was to play her part in WW2, serving as an Allied troopship in the 1940's and transporting troops and supplies to places such as Bombay in India.

Alfred passed his exams and achieved his Bachelor of Medicine degree in 1938. Soon after he took up a position as an Assistant General Practitioner in Reading, Berkshire.

128519 Captain Alfred Henry Snalam R.A.M.C. served his country for the majority of WW2, including the evacuation at Dunkirk in the early summer of 1940. He then travelled overseas to India and became involved with the first Wingate expedition as 7 Column's Medical Officer. In January 1943, as the Chindit Brigade was preparing to move down to Imphal and then on into Burma, Alfred was given the responsibility for Chindit Columns 7 and 2, whilst acting as Administration Officer for the train on which they were travelling. In late 1943, perhaps with the expertise and knowledge from his Chindit experiences, Alfred went on to work at Karachi General Hospital, specialising in the treatment of malaria.

After the war was over, Dr. Snalam returned to General Practice, this time as a full partner in a practice at Maidstone in Kent. Amongst other positions during this period, he was also appointed as Medical Advisor to the South East Gas Board. Sadly, Alfred passed away on the 13th May 1989. A short quote taken from the obituary mentioned above tells us more about Dr. Snalam the man:

Bill was a quiet, thoughtful man. He was a generous and knowledgeable host, and the Christmas Eve party that he and his wife, Jill, held became one of the highlights of the season. His hobbies were gardening, reading, and listening to music, but above all he was a devoted family man, and his grandchildren gave him great pleasure in his latter years. He is survived by Jill, a son, a daughter, and three grandchildren.

Captain J.D.S. Heathcote, was the Medical Officer for 8 Column. On the 15th April 1943 Captain Whitehead and his dispersal group, together with a party of wounded men on stretchers left the main body of 8 Column. Their aim was to find a 'friendly' village in which to leave the wounded men, then push on toward the Chinese borders in an attempt to reach Allied held territory. Doctor Heathcote was with this party presumably to look after the casualties until a suitable place to leave them could be found. Unfortunately this took some time, as the first few villages they tried for turned out to be deserted. On debrief after the operation, it was suggested that the medical officer should not have been allowed to go off with Whitehead's group, thus leaving the bulk of the column without a doctor.

Captain Whitehead's dispersal party was ambushed by a Japanese patrol on the way back to India and many of the men were taken prisoner. What happened to Dr. Heathcote is not definitely known, but he did not end up as a POW nor was he killed in action, so it must be assumed that he succeeded in escaping back to India in 1943.

7381858 Pte. Alan Frederick Forth, of the Royal Army Medical Corps, was one of the Medical Orderlies that served on Operation Longcloth in Burma. Sadly, Alan, a member of 7 Column, was taken ill himself around the time the Brigade began their return to India. He was allocated to the dispersal party led by Lt. Rex Walker, but died on the 9th April 1943. He is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial.

From a witness statement given by Pte. Tom Worthington of the 13th King's after his liberation from Rangoon Jail in May 1945:

This man was with 142 Company on Operation Longcloth and attached to No. 7 Column. He was a regular soldier and a medical orderly and was left in a village near the Irrawaddy River. His party under Lt. Rex Walker were informed several days later that he had died on the 9th April, suffering from appendicitis and malaria.

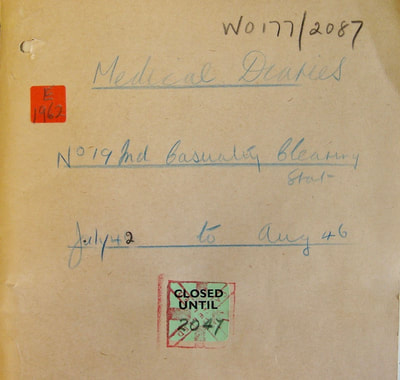

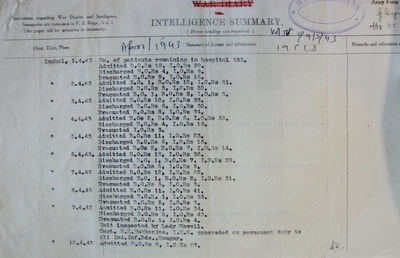

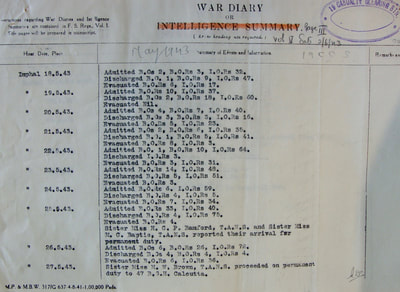

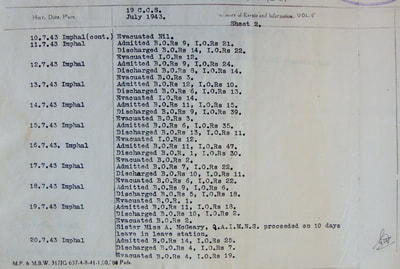

Matron Agnes McGearey (QAIMNS), was working in India at the 19th Casualty Clearing Station, based at Imphal at the time of the first Wingate expedition. The small hospital, under the command of Temporary Lt. Colonel G.G. Smith was really only a collection of roughly constructed basha type huts made from bamboo and with raffia grass roofs. The station had previously been based in Meerut, but had moved closer to the Assam/Burmese border presumably in readiness for the returning Chindits of Operation Longcloth.

Most, if not all of the returning Chindit soldiers passed through the clearing station in the months April through July 1943. Matron McGearey would become a much loved figure in hearts of the Chindit soldiers she tended in both 1943 and again in 1944. To read more about this legendary nurse, please click on the following link: Matron Agnes McGearey

Once under the medical staff at No. 19 Casualty Clearing Station, the Chindits were treated for all their ailments and wounds, shaved and de-loused and then given fresh clothing and plenty of bed rest. Matron McGearey and her staff ensured these men were well looked after, supplying them with many of the foods they had so craved during the long and arduous marches through the Burmese jungles. After a few days, each man was assessed and then either sent on to a more permanent hospital for further medical treatment, or moved north to enjoy an extended period of rest and recuperation in a more agreeable climate.

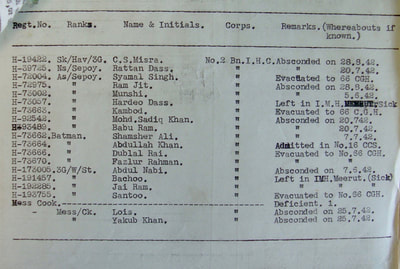

The turn over at the clearing station was extremely fast, with men coming and going during the months of April and May, almost on a daily basis. Seen in the gallery below, are pages from the War diary of No. 19 Casualty Clearing Station showing some of the months for Operation Longcloth and listing the number of casualties catered for. Please click on any image to bring on forward on the page.

In the war diary for the 13th King's, dated 2nd October 1943, there is an order written down asking for the subsequent return of all British Other Ranks from a variety of hospitals situated all over India. The list includes men recuperating at: No. 1 Indian/British Military Hospital in Karachi, BMH Jhansi, CMH Cawnpore, 126 IBGH Poona, BMH Bombay, BMH Shillong, BMH Bareilly, BMH Lahore Cantonment and 30 ICD (BT) Chaubattia. The above list shows that medical casualties from Operation Longcloth were still in the process of recuperation some four months after returning from Burma.

Many Chindits never had the benefit of receiving the excellent care delivered by Matron McGearey and her team at Imphal. Over 250 men fell into Japanese hands during the course of Operation Longcloth and then suffered many long and tortuous months as prisoners of war. Eventually, all Chindit POWs were held at Rangoon Central Jail situated close to dockland area of the capital city. Many of these men were already exhausted, malnourished and suffering from a multitude of tropical diseases when they arrived at Rangoon and were in desperate need of medical attention. Sadly, the Japanese attitude to their plight was not sympathetic.

The unsanitary conditions present in the jail, combined with the poor diet and lack of medical treatments available, guaranteed the death of many Chindit prisoners. During the early months of incarceration (June-November 1943) over seventy Chindits perished inside Rangoon Jail, mostly from conditions that could have been easily treated with very basic medicines.

The fact that some POW's did survive to achieve their liberation in April/May 1945, was down to a handful of medical officers and orderlies present in the jail and their heroic and inventive work in treating their many patients. All survivors of Rangoon Jail in one way or another, probably owed their further existence to the following men:

The unsanitary conditions present in the jail, combined with the poor diet and lack of medical treatments available, guaranteed the death of many Chindit prisoners. During the early months of incarceration (June-November 1943) over seventy Chindits perished inside Rangoon Jail, mostly from conditions that could have been easily treated with very basic medicines.

The fact that some POW's did survive to achieve their liberation in April/May 1945, was down to a handful of medical officers and orderlies present in the jail and their heroic and inventive work in treating their many patients. All survivors of Rangoon Jail in one way or another, probably owed their further existence to the following men:

Major Raymond Ramsay, Royal Army Medical Corps

Colonel Kenneth Pirie MacKenzie, Royal Army Medical Corps

Major Norman McLeod, Indian Medical Service

Captain Brahmanath Sudan, Burma Army Medical Corps

Captain Ahmed, Indian Army Medical Corps

Captain Dwgaprard Rao, Indian Army Medical Corps

Lieutenant N.S. Pillai, Indian Army Medical Corps

Lieutenant A.K. Singh, Indian Army Medical Corps

Orderly Pa Haw, Burma Army Medical Corps

Sepoy Abdullah Khan, Indian Army Medical Corps

Sepoy Man Bahadur, Indian Army Medical Corps

Sepoy Madan Singh, Burma Hospital Corps

Sepoy Vijay Singh, Indian Medical Service

Civilian K. Swamy, who assisted Captain Sudan

Colonel Kenneth Pirie MacKenzie, Royal Army Medical Corps

Major Norman McLeod, Indian Medical Service

Captain Brahmanath Sudan, Burma Army Medical Corps

Captain Ahmed, Indian Army Medical Corps

Captain Dwgaprard Rao, Indian Army Medical Corps

Lieutenant N.S. Pillai, Indian Army Medical Corps

Lieutenant A.K. Singh, Indian Army Medical Corps

Orderly Pa Haw, Burma Army Medical Corps

Sepoy Abdullah Khan, Indian Army Medical Corps

Sepoy Man Bahadur, Indian Army Medical Corps

Sepoy Madan Singh, Burma Hospital Corps

Sepoy Vijay Singh, Indian Medical Service

Civilian K. Swamy, who assisted Captain Sudan

It should also be mentioned that many non-medically trained soldiers assisted the above mentioned men in Rangoon Jail; whether that be in assisting with operations, cleaning and making surgical instruments, or simply tending and comforting the sick and the dying.

NB. In regards Major NI 65748 Norman McLeod of the Indian Medical Service (see list above), there is conflicting information about his capture during the Japanese period of ascendancy in Burma. One source suggests he was captured alongside Colonel Kenneth McKenzie after the Sittang Bridge was destroyed during the British Army's retreat from Burma in February 1942. However, another source indicates he may have been the Medical Officer for No. 4 Column on Operation Longcloth and was captured in April 1943. What we do know for sure, is that Major McLeod, who suffered himself with severe dysentery for much of his time in Rangoon, was responsible for saving many lives in the jail over the years. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this section of the story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

NB. In regards Major NI 65748 Norman McLeod of the Indian Medical Service (see list above), there is conflicting information about his capture during the Japanese period of ascendancy in Burma. One source suggests he was captured alongside Colonel Kenneth McKenzie after the Sittang Bridge was destroyed during the British Army's retreat from Burma in February 1942. However, another source indicates he may have been the Medical Officer for No. 4 Column on Operation Longcloth and was captured in April 1943. What we do know for sure, is that Major McLeod, who suffered himself with severe dysentery for much of his time in Rangoon, was responsible for saving many lives in the jail over the years. Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this section of the story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

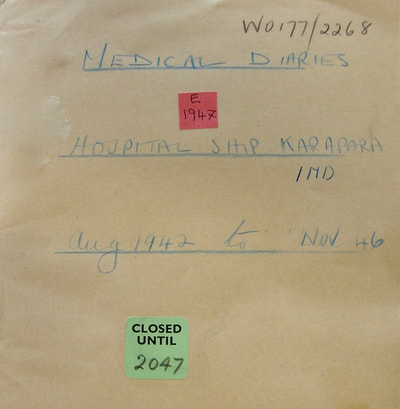

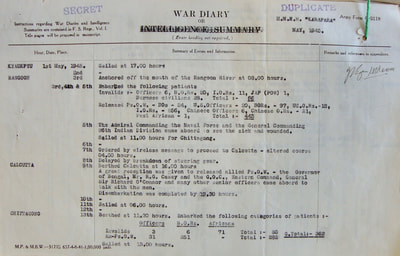

In late April 1945, 400 prisoners from Rangoon Jail were taken out of the prison by the Japanese. These men were to be used by the enemy as human shields and hostages, should the Japanese meet the advancing 14th Army along their journey southeast towards Thailand. These POW's were eventually released on the 29th April on the Pegu Road. Meanwhile, back inside the jail, those men who were not fit enough to be chosen for the Pegu march took care of themselves until they too were liberated on May 3rd. Within a few days the remainder of the POW's travelled the short journey down to the docks at Rangoon and were put aboard the hospitalship Karapara. The Karapara then pulled away from Rangoon and headed back across the Bay of Bengal to the Indian mainland and disembarked their human cargo at Calcutta and Chittagong.

To read more about the history of HMHS Karapara, please click on the following link: www.roll-of-honour.com/Ships/HMHSKarapara.html

Featured below is a short video from 1945, depicting the liberation of Rangoon Jail and the prisoners walking down to the dockside in the rain to board HMHS Karapara.

NB. The Karapara was used again in February 1948, to transport the families of Gurkha Officers and Riflemen to Singapore. These were men from the 2nd, 6th, 7th and 10th Gurkha Regiments who had decided to remain with the British Army after the partition of India and the newly formed Pakistan and would now serve in places such as Malaya, Hong Kong and Brunei.

To read more about the history of HMHS Karapara, please click on the following link: www.roll-of-honour.com/Ships/HMHSKarapara.html

Featured below is a short video from 1945, depicting the liberation of Rangoon Jail and the prisoners walking down to the dockside in the rain to board HMHS Karapara.

NB. The Karapara was used again in February 1948, to transport the families of Gurkha Officers and Riflemen to Singapore. These were men from the 2nd, 6th, 7th and 10th Gurkha Regiments who had decided to remain with the British Army after the partition of India and the newly formed Pakistan and would now serve in places such as Malaya, Hong Kong and Brunei.

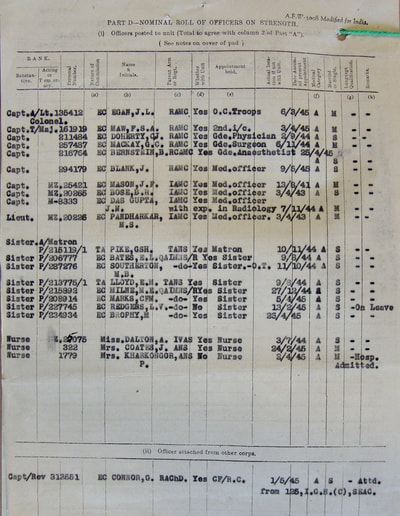

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to the liberation of Rangoon Jail and the involvement of the hospitalship Karapara. These include some pages from the ship's War diary and some more photographs of the recently liberated POW's aboard the ship. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After repatriation to the United Kingdom, many of the Chindits formerly held as prisoners of war by the Japanese, were tended by local GPs and doctors in hospitals all over the country. On behalf of the Chindits in question, I would like to belatedly thank all these medical professionals for the help and care they gave to these men.

After repatriation to the United Kingdom, many of the Chindits formerly held as prisoners of war by the Japanese, were tended by local GPs and doctors in hospitals all over the country. On behalf of the Chindits in question, I would like to belatedly thank all these medical professionals for the help and care they gave to these men.

Update 22nd March 2024.

Andrew Donald Wilson.

Dr. Andrew Wilson spent just over four years serving with the Gurkhas as part of the Indian Army during WW2. His actual placement in terms of regiment is unknown, but according to a short article found in the Brisbane Telegraph, dated 7th August 1946 (see to the left), he and the Chindits certainly did cross paths. In the article he mentions treating the wounded and sick from 77 Brigade as they crossed the Chindwin River in 1943 and also refers to a an officer who called for replacement monocle. This must of course refer to Major Bernard Fergusson, the commander of No. 5 Column.

It is known that the 3rd battalion of the 5th Gurkha Rifles were active in the area around the Chindwin at this time and were certainly involved in assisting the Chindits as they navigated the river on both the outward and return journeys. So, it is possible that Dr. Wilson was attached to this Gurkha unit at the time.

From searches online, it is known that Andrew Wilson passed his Pharmacy Board exams in December 1927 at Melbourne, Australia. He married, Violet Laurel Smith on the 5th March 1928, also at Melbourne. He undertook an Emergency Commission into the Indian Medical Services as a Lieutenant on the 10th January 1941 (London Gazette 22nd August 1941). Then was listed as Captain Andrew Donald Wilson, LRCP (Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians), LRCS (Licentiate of the Royal college of Surgeons) and LRFPS (Licentiate of the Royal Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons) as of 21st November 1941, with an antedate of five years and six months, thus confirming his seniority (Captain) since January 1937. I would like to thank Dr. Andrew Kilsby for the above information and for bringing Andrew Wilson to my attention.

Andrew Donald Wilson.

Dr. Andrew Wilson spent just over four years serving with the Gurkhas as part of the Indian Army during WW2. His actual placement in terms of regiment is unknown, but according to a short article found in the Brisbane Telegraph, dated 7th August 1946 (see to the left), he and the Chindits certainly did cross paths. In the article he mentions treating the wounded and sick from 77 Brigade as they crossed the Chindwin River in 1943 and also refers to a an officer who called for replacement monocle. This must of course refer to Major Bernard Fergusson, the commander of No. 5 Column.

It is known that the 3rd battalion of the 5th Gurkha Rifles were active in the area around the Chindwin at this time and were certainly involved in assisting the Chindits as they navigated the river on both the outward and return journeys. So, it is possible that Dr. Wilson was attached to this Gurkha unit at the time.

From searches online, it is known that Andrew Wilson passed his Pharmacy Board exams in December 1927 at Melbourne, Australia. He married, Violet Laurel Smith on the 5th March 1928, also at Melbourne. He undertook an Emergency Commission into the Indian Medical Services as a Lieutenant on the 10th January 1941 (London Gazette 22nd August 1941). Then was listed as Captain Andrew Donald Wilson, LRCP (Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians), LRCS (Licentiate of the Royal college of Surgeons) and LRFPS (Licentiate of the Royal Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons) as of 21st November 1941, with an antedate of five years and six months, thus confirming his seniority (Captain) since January 1937. I would like to thank Dr. Andrew Kilsby for the above information and for bringing Andrew Wilson to my attention.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, May 2018.