2nd Burma Rifles Roll Call

Tough cheerful little men carrying packs which seemed to be almost as big as themselves, almost every Chindit column had a section of them. The British Other Ranks had only a vague idea where they came from or what they were there to do. All they did know was that they faced the dangers and discomforts of the campaign with good humour and good heart. When there was any fighting to be done they did it with a ruthlessness and dash second to none.

They were the Burrifs, men of the Burma Rifles. The 'Free Burmese' if you like, for they came from the Kachin, the Karen and the Chin tribes of Burma. When they went into Burma they were fighting for the freedom of their own country. The British 'Tommy', often a harsh critic, soon became a lively admirer of the Burrifs. It was surprising how well the two races got on together immediately they met. This was largely due to the intelligence of the Burma Riflemen and his desire to master the English language, which he did far more than the British learnt Burmese. Perhaps his greatest skill was the Burrif's ability to find or access food, for which the Tommy had the deepest, and quite understandable admiration.

First published in 1944 by Frank Owen in the magazine, The Chindits.

This page is devoted to the men from the Burma Rifles who are mentioned with fondness and pride in the books, diaries and memoirs for Operation Longcloth, but for whom a more detailed story is unlikely to ever be uncovered. It is rare for a lower ranked soldier to be mentioned in a battalion war diary, or most official memoirs unless he has performed some act of great valour or gallantry. Featured below are mentions of men from the 2nd Battalion, the Burma Rifles who took part on Operation Longcloth and who deserve their place in the recorded history of the first Wingate expedition in 1943.

Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion were from the Kachin Hill tribes of Burma. They were posted to Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters in late autumn 1942, whilst the newly formed Chindits were training at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. By early April 1943, both men found themselves in the dispersal group commanded by Captain Graham Hosegood and Lieutenant R. A. Wilding. For most of the month of April the group moved back and forth along the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River in an attempt to gain a crossing to the west side and return to India.

From the pages of his memoirs, Lieutenant Wilding remembered this time:

We spent the next couple of weeks resting and preparing for another attempt to cross the Irrawaddy. One of the Burmese Jemadars was wounded and captured during a recce to Inywa (the nearest large town) and a British Private got lost while out searching for water and was presumed captured.

Our party made some more rafts and set out for the Irrawaddy. However we found ourselves in a mangrove swamp and could not get through. We then decided to try to go east, cross the Shweli where it was but a stream, swing north and go into the Kachin Hills and there sweat out the monsoon.

Burma Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion were from this part of Burma and hoped to lead the dispersal group to their own village in the Kachin Hills and remain there until the monsoon had ended. It was only eighty miles, but we had hardly any supplies left, so we decided to find a village and obtain some food. There was not much food to be found, but the Headman offered to put us over the river for a consideration, a very considerable consideration.

Wilding's memoir continues: That evening, the 21st April, the Headman and his "brother" took us at racing speed to the river. It was night and we were not exactly sure where we were. We embarked, paddled round one island and disembarked, handed over nearly all of our money and set out for the hills to the west. Alas we found a wide stretch of water between us and the hills; it was the main river, we had literally been sold up the river.

The next six days are very confused in my mind. We searched the island, it was about a mile long and half a mile wide. We found a village and persuaded the villagers to sell us a meal, but this only occurred once. I had two black-outs which were alarming. When travelling in a hot country beware when the sweat getting into your eyes stops stinging as this denotes that you need salt.

On the 29th April we found a boat that floated. We decided that Second Lieutenant Pat Gordon, Lance-Corporal Purdie and Signalman Belcher, with Burma Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion as paddlers, should make the first trip. They reached the other side, then we heard Pat rallying his men and a good deal of firing and then silence. Orlando and Tunnion survived but the others were all killed. I was very sad. I thought that the first boat load would have the best chance, but I was wrong.

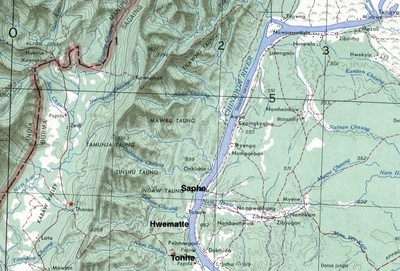

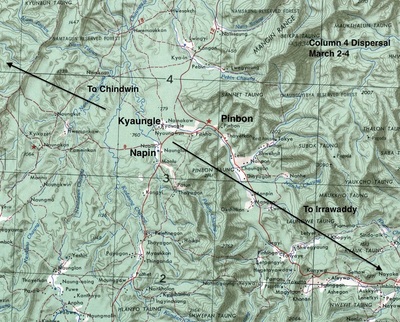

Shown below is a map of the area where Riflemen Orlando, Tunnion and the others attempted the crossing of the Irrawaddy near the village of Tigyaing. Please click on the map to bring it foreword on the page. For more details about the dispersal group led by Captain Hosegood and Lieutenant Wilding, please click on the following link: Lieutenant R.P. Gordon

They were the Burrifs, men of the Burma Rifles. The 'Free Burmese' if you like, for they came from the Kachin, the Karen and the Chin tribes of Burma. When they went into Burma they were fighting for the freedom of their own country. The British 'Tommy', often a harsh critic, soon became a lively admirer of the Burrifs. It was surprising how well the two races got on together immediately they met. This was largely due to the intelligence of the Burma Riflemen and his desire to master the English language, which he did far more than the British learnt Burmese. Perhaps his greatest skill was the Burrif's ability to find or access food, for which the Tommy had the deepest, and quite understandable admiration.

First published in 1944 by Frank Owen in the magazine, The Chindits.

This page is devoted to the men from the Burma Rifles who are mentioned with fondness and pride in the books, diaries and memoirs for Operation Longcloth, but for whom a more detailed story is unlikely to ever be uncovered. It is rare for a lower ranked soldier to be mentioned in a battalion war diary, or most official memoirs unless he has performed some act of great valour or gallantry. Featured below are mentions of men from the 2nd Battalion, the Burma Rifles who took part on Operation Longcloth and who deserve their place in the recorded history of the first Wingate expedition in 1943.

Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion were from the Kachin Hill tribes of Burma. They were posted to Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters in late autumn 1942, whilst the newly formed Chindits were training at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. By early April 1943, both men found themselves in the dispersal group commanded by Captain Graham Hosegood and Lieutenant R. A. Wilding. For most of the month of April the group moved back and forth along the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River in an attempt to gain a crossing to the west side and return to India.

From the pages of his memoirs, Lieutenant Wilding remembered this time:

We spent the next couple of weeks resting and preparing for another attempt to cross the Irrawaddy. One of the Burmese Jemadars was wounded and captured during a recce to Inywa (the nearest large town) and a British Private got lost while out searching for water and was presumed captured.

Our party made some more rafts and set out for the Irrawaddy. However we found ourselves in a mangrove swamp and could not get through. We then decided to try to go east, cross the Shweli where it was but a stream, swing north and go into the Kachin Hills and there sweat out the monsoon.

Burma Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion were from this part of Burma and hoped to lead the dispersal group to their own village in the Kachin Hills and remain there until the monsoon had ended. It was only eighty miles, but we had hardly any supplies left, so we decided to find a village and obtain some food. There was not much food to be found, but the Headman offered to put us over the river for a consideration, a very considerable consideration.

Wilding's memoir continues: That evening, the 21st April, the Headman and his "brother" took us at racing speed to the river. It was night and we were not exactly sure where we were. We embarked, paddled round one island and disembarked, handed over nearly all of our money and set out for the hills to the west. Alas we found a wide stretch of water between us and the hills; it was the main river, we had literally been sold up the river.

The next six days are very confused in my mind. We searched the island, it was about a mile long and half a mile wide. We found a village and persuaded the villagers to sell us a meal, but this only occurred once. I had two black-outs which were alarming. When travelling in a hot country beware when the sweat getting into your eyes stops stinging as this denotes that you need salt.

On the 29th April we found a boat that floated. We decided that Second Lieutenant Pat Gordon, Lance-Corporal Purdie and Signalman Belcher, with Burma Riflemen Orlando and Tunnion as paddlers, should make the first trip. They reached the other side, then we heard Pat rallying his men and a good deal of firing and then silence. Orlando and Tunnion survived but the others were all killed. I was very sad. I thought that the first boat load would have the best chance, but I was wrong.

Shown below is a map of the area where Riflemen Orlando, Tunnion and the others attempted the crossing of the Irrawaddy near the village of Tigyaing. Please click on the map to bring it foreword on the page. For more details about the dispersal group led by Captain Hosegood and Lieutenant Wilding, please click on the following link: Lieutenant R.P. Gordon

Both the Riflemen were captured by the Japanese on the 29th April and were eventually taken to the Maymyo Concentration Camp, where the enemy were collecting together all the Chindit prisoners of war. The two men worked as slave labour for their captors for a short period, before possibly being sent down to Rangoon Jail with the rest of the Chindit POW's. This is where their trail goes cold, but as no casualties by their names exist in CWGC records, it is a fair assumption that they survived their time in captivity and returned to their Kachin villages after liberation.

Jemadar 50009 Moody was also with Wingate's Brigade HQ on Operation Longcloth. In fact Moody was the Jemadar mentioned at the beginning of Lieutenant Wilding's memoir (above) as being wounded and captured by the Japanese whilst out on a recce of the riverside town of Inywa (see above map). Jemadar Moody was taken to the Maymyo Camp almost immediately and spent several weeks there before managing to escape and return to India.

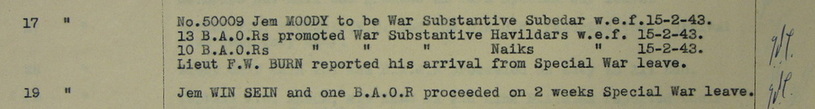

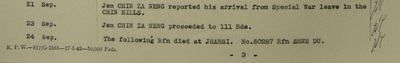

On returning to his battalion, now based at Karachi, Jemadar Moody was sent to the hill stations of northern India for a period of rest and recuperation. In August 1943 the battalion war diary recorded his retrospective promotion to Subedar, a reward for his efforts on Longcloth and for escaping captivity at Maymyo. Seen below is an extract from the battalion war diary, showing his promotion on the 17th August 1943.

Jemadar 50009 Moody was also with Wingate's Brigade HQ on Operation Longcloth. In fact Moody was the Jemadar mentioned at the beginning of Lieutenant Wilding's memoir (above) as being wounded and captured by the Japanese whilst out on a recce of the riverside town of Inywa (see above map). Jemadar Moody was taken to the Maymyo Camp almost immediately and spent several weeks there before managing to escape and return to India.

On returning to his battalion, now based at Karachi, Jemadar Moody was sent to the hill stations of northern India for a period of rest and recuperation. In August 1943 the battalion war diary recorded his retrospective promotion to Subedar, a reward for his efforts on Longcloth and for escaping captivity at Maymyo. Seen below is an extract from the battalion war diary, showing his promotion on the 17th August 1943.

Jemadar Saw Cameron was part of the Burma Rifles platoon for Chindit Column 3 on Operation Longcloth. In late March 1943, Major Calvert, the commander of 3 Column decided the time had come to break his unit down into smaller dispersal parties. Jemadar Saw Cameron was given joint leadership of one of these groups, alongside Gurkha officer, Subedar Siribhagta Gurung. These two officers led a party of around forty men, made up of the Gurkha Support platoon and a number of Gurkha muleteers.

The group led by Siribhagta and Jemadar Cameron were soon in trouble, struggling to find ways of crossing those interminable obstacles, the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. Around the first week in April the men were captured by the Japanese and were taken to the main concentration camp for captured Chindits at Maymyo. Eventually the main group of British Chindit POW's were sent down to Rangoon Jail by train, however, Siribhagta, Cameron and many of the Indian soldiers were not with this group and found themselves heading north towards Myitkhina.

Saw Cameron managed to escape from his captors in November 1943, for his efforts he was awarded a 'Mention in Despatches' and promoted to the rank of Subedar. Here are the details of his award:

Subedar Saw Cameron, 2nd Burma Rifles

This man was a member of General Wingate's expedition in 1943. He was taken prisoner by the Japanese during the withdrawal to India on the 7th April. He was sent to the Maymyo Camp, but later transferred along with other POW's to Myitkhina in September 1943. There he was employed on fatigues and on the 21st October detailed with two other prisoners to carry rations for a party of the enemy moving up to Sumprabum.

Saw Cameron and the two other POW's were left with a Japanese Propaganda Unit a little way south of Sumprabum and later received orders to return to Myitkhina. During the return journey Saw Cameron discussed plans to escape with his companions and on the 12th November 1943 they took their opportunity.

Although there is nothing outstanding about his escape, Subedar Saw Cameron brought back information of military value and was undoubtedly the leader of this party. He has already been awarded the Burma Gallantry Medal for his service with the 77th Brigade and it is now considered that he should be granted a 'Mention in Despatches' along with his two companions:

1068 Jemadar Gyanbir Thapa of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles

31334 Naik Damarbahadur Rana of the 3rd Assam Rifles.

Subedar 50005 Saw Donny was also a member of Calvert's Chindit column in 1943. He too was given the responsibility of leading a dispersal party after the unit was broken up in late March. Alongside Gurkha officer, Subedar Kum Sing Gurung he led a group made up from the column's Head Quarters section. During the operation, Donny had been invaluable to his commander, often entering villages alone in the search of information, boats or food.

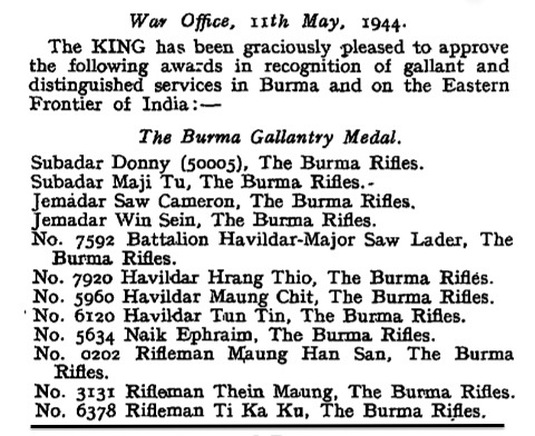

Kum Sing and Subedar Donny had both been heavily involved in 3 Column's engagement with the Japanese at a place called Pago, close to the Shweli River. The two junior officers decided to exit Burma via the Chinese Yunnan Borders and arrived back in Allied held territory sometime in June 1943. Subedar Donny was awarded the Burma Gallantry Medal for his efforts on Operation Longcloth, he later became Quartermaster General in the fledgling Burmese Army after the country's independence in 1948.

Naik Tun Tin was a member of Chindit Column 8, commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment. On dispersal, this Burma Rifleman was posted to the group led by Lieutenant Dominic Neill of the Gurkha Rifles and Lieutenant T.A.G. Sprague of 142 Commando. He was to become a pivotal member of this dispersal group, leading all reconnaissance and venturing into local villages in search of information and supplementary rations for his group.

Dominic Neill remembered Naik Tun Tin in his memoir, written after the war was over:

Lieutenant Sprague and I decided to march in a northerly direction on leaving 8 Column and to try to re-cross the vast Irrawaddy somewhere along its stretch where it flows east-west between the big villages of Bhamo and Katha. We would have to avoid Shwegu, though, as we had been told that that village contained a Japanese garrison. Every escape group had been given half-a-dozen or so soldiers from Nigel Whitehead's Platoon of 2nd Burma Riflemen. We were delighted when we found that we had Naik Tun Tin and four Riflemen attached to us. Tun Tin had always struck me as being one of Nigel's most outstanding young NCOs. He, like the rest of his small party, was a Karen. He had been educated at a mission school; not only was he very intelligent, but he spoke excellent English. Tun Tin was to prove himself to be of tremendous assistance to us. Sadly, we were to be parted from Tun Tin sooner than we would have wished.

Naik Tun Tin became separated from Neill's dispersal group around the 14th April when they were ambushed by a Japanese patrol close to the Kaukkwe Chaung and the village of Thayetta.

Another Rifleman mentioned by Lieutenant Neill as being part of his dispersal group, was Maung San. This man remained with the dispersal group after the ambush at Thayetta and continued with the group on their journey back to India.

There is no further information available in reference to Naik Tun Tin and what happened to him after the incident at the Kaukkwe Chaung. However, another Naik with the same name is recorded as being one of the men from 8 Column that was flown out of the jungle in late April 1943, when a Dakota plane managed to put down on a jungle clearing and pick up 18 sick and wounded Chindits.

It is impossible to say for sure whether Naik 3823 Tun Tin, the fortunate passenger aboard the Dakota, was the same man who had previously served with Dominic Neill's dispersal group, but, both groups had frequented the area around the Kaukkwe Chaung at that time, so it is not so unlikely. Indeed, if any man possessed the skills needed, after being separated from one group, to then successfully find his way across to another Chindit party, it was Naik Tun Tin.

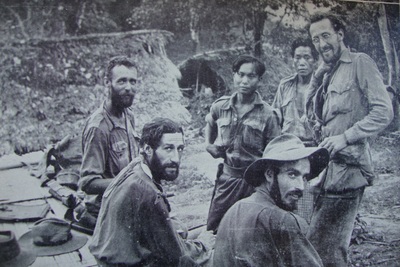

Seen below is a photograph of the sick and wounded Chindits that were airlifted to safety aboard the RAF Dakota in late April 1943. Tun Tin is the man seated in the front row wearing the headband.

The group led by Siribhagta and Jemadar Cameron were soon in trouble, struggling to find ways of crossing those interminable obstacles, the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. Around the first week in April the men were captured by the Japanese and were taken to the main concentration camp for captured Chindits at Maymyo. Eventually the main group of British Chindit POW's were sent down to Rangoon Jail by train, however, Siribhagta, Cameron and many of the Indian soldiers were not with this group and found themselves heading north towards Myitkhina.

Saw Cameron managed to escape from his captors in November 1943, for his efforts he was awarded a 'Mention in Despatches' and promoted to the rank of Subedar. Here are the details of his award:

Subedar Saw Cameron, 2nd Burma Rifles

This man was a member of General Wingate's expedition in 1943. He was taken prisoner by the Japanese during the withdrawal to India on the 7th April. He was sent to the Maymyo Camp, but later transferred along with other POW's to Myitkhina in September 1943. There he was employed on fatigues and on the 21st October detailed with two other prisoners to carry rations for a party of the enemy moving up to Sumprabum.

Saw Cameron and the two other POW's were left with a Japanese Propaganda Unit a little way south of Sumprabum and later received orders to return to Myitkhina. During the return journey Saw Cameron discussed plans to escape with his companions and on the 12th November 1943 they took their opportunity.

Although there is nothing outstanding about his escape, Subedar Saw Cameron brought back information of military value and was undoubtedly the leader of this party. He has already been awarded the Burma Gallantry Medal for his service with the 77th Brigade and it is now considered that he should be granted a 'Mention in Despatches' along with his two companions:

1068 Jemadar Gyanbir Thapa of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles

31334 Naik Damarbahadur Rana of the 3rd Assam Rifles.

Subedar 50005 Saw Donny was also a member of Calvert's Chindit column in 1943. He too was given the responsibility of leading a dispersal party after the unit was broken up in late March. Alongside Gurkha officer, Subedar Kum Sing Gurung he led a group made up from the column's Head Quarters section. During the operation, Donny had been invaluable to his commander, often entering villages alone in the search of information, boats or food.

Kum Sing and Subedar Donny had both been heavily involved in 3 Column's engagement with the Japanese at a place called Pago, close to the Shweli River. The two junior officers decided to exit Burma via the Chinese Yunnan Borders and arrived back in Allied held territory sometime in June 1943. Subedar Donny was awarded the Burma Gallantry Medal for his efforts on Operation Longcloth, he later became Quartermaster General in the fledgling Burmese Army after the country's independence in 1948.

Naik Tun Tin was a member of Chindit Column 8, commanded by Major Walter Purcell Scott of the King's Regiment. On dispersal, this Burma Rifleman was posted to the group led by Lieutenant Dominic Neill of the Gurkha Rifles and Lieutenant T.A.G. Sprague of 142 Commando. He was to become a pivotal member of this dispersal group, leading all reconnaissance and venturing into local villages in search of information and supplementary rations for his group.

Dominic Neill remembered Naik Tun Tin in his memoir, written after the war was over:

Lieutenant Sprague and I decided to march in a northerly direction on leaving 8 Column and to try to re-cross the vast Irrawaddy somewhere along its stretch where it flows east-west between the big villages of Bhamo and Katha. We would have to avoid Shwegu, though, as we had been told that that village contained a Japanese garrison. Every escape group had been given half-a-dozen or so soldiers from Nigel Whitehead's Platoon of 2nd Burma Riflemen. We were delighted when we found that we had Naik Tun Tin and four Riflemen attached to us. Tun Tin had always struck me as being one of Nigel's most outstanding young NCOs. He, like the rest of his small party, was a Karen. He had been educated at a mission school; not only was he very intelligent, but he spoke excellent English. Tun Tin was to prove himself to be of tremendous assistance to us. Sadly, we were to be parted from Tun Tin sooner than we would have wished.

Naik Tun Tin became separated from Neill's dispersal group around the 14th April when they were ambushed by a Japanese patrol close to the Kaukkwe Chaung and the village of Thayetta.

Another Rifleman mentioned by Lieutenant Neill as being part of his dispersal group, was Maung San. This man remained with the dispersal group after the ambush at Thayetta and continued with the group on their journey back to India.

There is no further information available in reference to Naik Tun Tin and what happened to him after the incident at the Kaukkwe Chaung. However, another Naik with the same name is recorded as being one of the men from 8 Column that was flown out of the jungle in late April 1943, when a Dakota plane managed to put down on a jungle clearing and pick up 18 sick and wounded Chindits.

It is impossible to say for sure whether Naik 3823 Tun Tin, the fortunate passenger aboard the Dakota, was the same man who had previously served with Dominic Neill's dispersal group, but, both groups had frequented the area around the Kaukkwe Chaung at that time, so it is not so unlikely. Indeed, if any man possessed the skills needed, after being separated from one group, to then successfully find his way across to another Chindit party, it was Naik Tun Tin.

Seen below is a photograph of the sick and wounded Chindits that were airlifted to safety aboard the RAF Dakota in late April 1943. Tun Tin is the man seated in the front row wearing the headband.

Havildar Lanval was another member of 8 Column on Operation Longcloth. On the 20th April 1943 this man assisted Major Scott in hi-jacking a Burmese junk near the village of Taukte on the southern banks of the Irrawaddy River. The men had been in bivouac close to the river in this location and were watching for a means to cross to the northern side when the large junk was spotted. From the pages of the 8 Column War diary:

The listening post on the bank reported the movements of three small country boats and one larger Burmese junk. The junk made its way over from the far side and landed on a sandbank about 100 yards from our bivouac. Major Scott, Lieutenant Borrow and Havildar Lanval made an instant decision to capture the boat and rushed across the shallow water. Three of the crew jumped overboard and tried to swim away. With Major Scott and Borrow now aboard, Havildar Lanval jumped into the water and got hold of the lead boatman forcing him back onto his craft.

Arrangements were made to ferry the column across the river and within ten minutes the first boat load of sixty men had been chosen, with swimmers hanging on the the side of the junk and non-swimmers inside. Over the following ninety minutes the whole of the column including the last remaining mule were transferred to the northern bank.

NB. The reader should know, that although clearly frightened by his experience, the captain of the junk was well rewarded in silver rupees for the use of his craft.

During Chindit training in the late summer and autumn of 1942, two very senior native officers joined Brigadier Wingate's Brigade HQ. These were Major Po and Captain Maung Aung Thin. They were both popular with the other British officers in the group, as Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding remembered in his memoirs written after his liberation from Rangoon Jail in 1945:

I got to know the other officers at Brigade Headquarters, with whom I was to work. The intelligence officer Captain Hosegood was a very nice chap who gave me lots of help. The signals officer Lieutenant Spurlock was quite brilliant at his job and also a very good chap.

There were also two delightful Burmese officers named Major Po and Captain Aung Thin. Another officer, Captain Sawba Pa was a Shan Prince and came to us as a replacement for Major Po; the Major being deemed a bit old for the trip. We called him 'Pop'. He had a ferocious orderly whom we called 'Smiler', if he thought you were not being polite to his Officer he was inclined to whip out his Dah (a sort of knife). 'Pop' was a great lad and all ranks liked him. He tried to help out with my ciphers one day but everything came out as 'paraffin'. I think ciphers were just not his thing.

Unlike Major Po, Captain Aung Thin did take part on Operation Longcloth and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his efforts in 1943. You can read more about this officer by searching for his DSO recommendation on this page: Burma Rifle Citations; Aung Thin was also given credit for coming up with the idea of calling the Brigade, 'Chinthes' after the mythical beasts that guard Burmese pagodas, this title then became corrupted through translation to the word Chindits.

Update 28/02/2024.

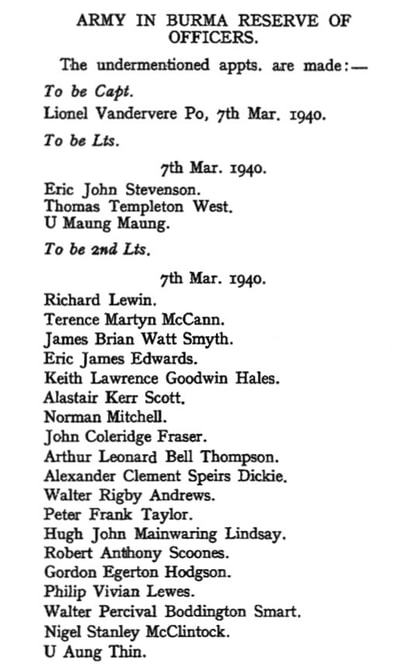

Lionel Vandevere Po was born on the 8th May 1900 in Bassein, the main town in the southern-most peninsula of the Arakan region of Burma. His father was Dr. Sir San C. Po from the Karen community, who was knighted by the British Crown. Lionel Po enlisted (probably underage) into the 1st London Fusiliers Regiment during WW1 and was awarded the British War Medal for his service. Then after spending several years in the USA, he returned to Burma.

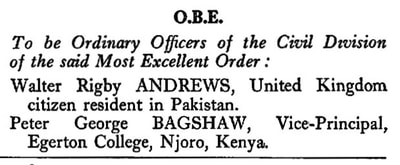

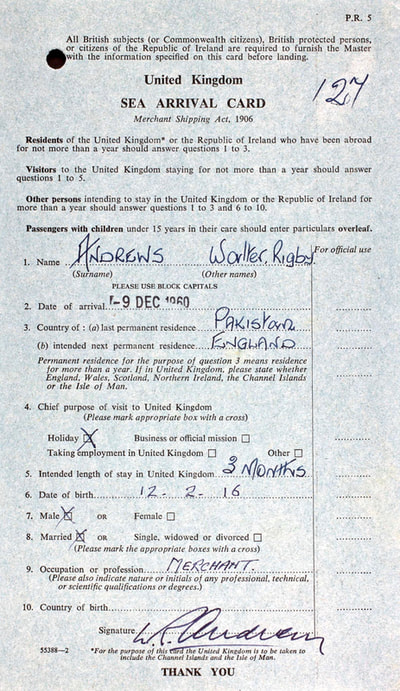

After taking a commission into the Indian Army in 1922 (resigning in 1928), he later, as a reserve officer commanded No. 5 Garrison Company (Rangoon) during 1940-41. It is suggested that he served with the 2nd Burma Rifles in 1942, before being considered for a posting with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) as a Captain (ABRO 84) in early 1943, spending just under eight months with Force 136.

As already mentioned, Lionel Po was employed for a time with the Chindits during their training period at Saugor/Jhansi and worked in close association with Captain Aung Thin. Major Po left SOE on the 16th September 1943 and returned to service with the Indian Army.

Many thanks to Fred Johnson from Ontario (Canada) and Richard Duckett for their valuable help with this update. You can visit Richard’s excellent website here: https://soeinburma.com/the-operations-of-soe-burma/

For more information about Lionel Po, including a photograph of this well decorated soldier, please also visit Richard Warren’s website by following this link: https://burmamyanmarphilately.wordpress.com

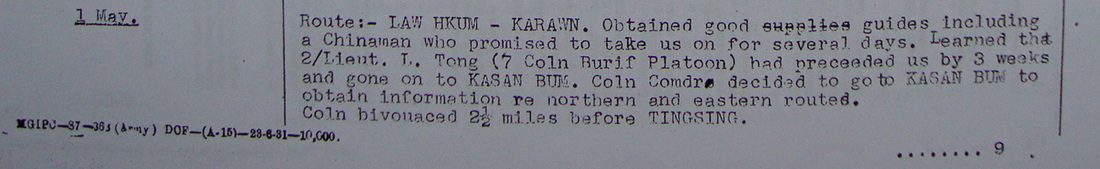

2nd Lieutenant L. Tong had been part of 7 Column's Burriff platoon on Operation Longcloth, working closely in the early stages with Lieutenants Astell and Musgrave-Wood and latterly with Captain Herring. The young subaltern is mentioned just once in the War diary pages for 7 Column, recounting his progress when leading a dispersal party out of Burma via the Chinese Yunnan Borders. Major Gilkes and 7 Column Adjutant, Leslie Cottrell remembered:

As dawn was breaking on May Day a sentry brought in what they first thought was a Japanese soldier in civilian clothes. Upon questioning it turned out he was Chinese and was very pleased to see the British officers, as he thought that the Gurkha who had apprehended him was also a Japanese soldier.

He spoke good Kachin and Gilkes asked him to accompany them to China and interpret for them. He agreed without question and for the next five days led the column along the valleys and over the hills, avoiding the main tracks and the Japanese outposts. They also heard that Second Lieutenant L. Tong from 7 Column's Burrif Platoon had preceded them by three weeks, heading for Kasan Bum. They decided to follow in his footsteps to obtain information on the northern and eastern routes.

They were now following the route Tinsing-Lung Hkat-Banlun and found the villages very hospitable. Guides would precede them to villages en route and they would find food waiting for them as they arrived. In several of the villages they found Burrifs, many of them on leave from their own platoons.

At Banlun a Burrif Subedar gave them information on other parties that had passed through. The commander of 7 Column Burma Rifles platoon, Captain Herring, together with a Jemadar and sixteen Other Ranks went through on 20th April, having given up hope of meeting up with George Dunlop and 1 Column. Captain Buchanan, three British Other Ranks and fifty-five Gurkhas and Karens went through on 26th April, and a week prior to that Lieutenant Astell and forty-five mixed Other Ranks moved through the area. Major Gilkes had also just missed another Burrif officer, Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood and his party of fifteen men by a couple of days.

Seen below is the 7 Column War diary extract mentioning 2nd Lieutenant Tong and the progress of his dispersal party in early May 1943.

Bernard Fergusson wrote many books which recount his Chindit experiences, both in 1943 and then again in 1944. In his writings he has always championed the men of the 2nd Burma Rifles, mentioning many of their brave exploits performed by officer and Rifleman alike. For this reason there are more tales about the Burrif's from 5 Column, than any other Chindit unit. The next section of the Roll Call is devoted to the Burma Riflemen that served with 5 Column, but first, let us learn what Bernard Fergusson thought of these men and how they nearly ceased to exist as a unit in 1942. From his excellent book 'The Trumpet in the Hall' :

What we would have done without the Burma Rifles I hate to think. When the Army was struggling out of Burma early in 1942, somebody at a high level in Delhi had given the idiotic order that all Burman soldiers should be paid off at Imphal and told to make their way home. We on the Planning Staff heard this too late to countermand it.

Obviously every Burman soldier would be of the greatest value when we re-invaded; and Wavell had already and characteristically given orders, long before the evacuation was complete, that studies for the re-invasion should be put in hand at once. Denis O'Callaghan, who then commanded the 2nd Burma Rifles, had the sense and the guts to ignore the order. Thanks to him and him alone, we had this one precious and excellent battalion in India; and it was allotted to Wingate, along with one Gurkha battalion and one British.

The Gurkha one was newly raised and scarcely trained, the British one had an average age far above the normal; it had been raised and sent out to India for garrison duties only. The Gurkhas were organised in four columns; the British, owing to wastage on training, into three; and the Burma Rifles were split into seven strong reconnaissance platoons, one to each column. They were our eyes and our ears, and our foragers too. My particular lot were Karens. I have often paid tribute to them before, and it is a privilege to do so once again.

Subedar Ba Than was the lead Burmese officer in 5 Column during Operation Longcloth. Bernard Fergusson described him as, "a rather solemn and conscientious man." Ba Than was from the Karen tribe and a devout christian, his family being converted by the local American Baptist Mission in the early 1930's. His brother, Jemadar Wilson also took part in the first Chindit expedition, but his column placement is unknown to me at this time, although he did successfully return to India in May 1943.

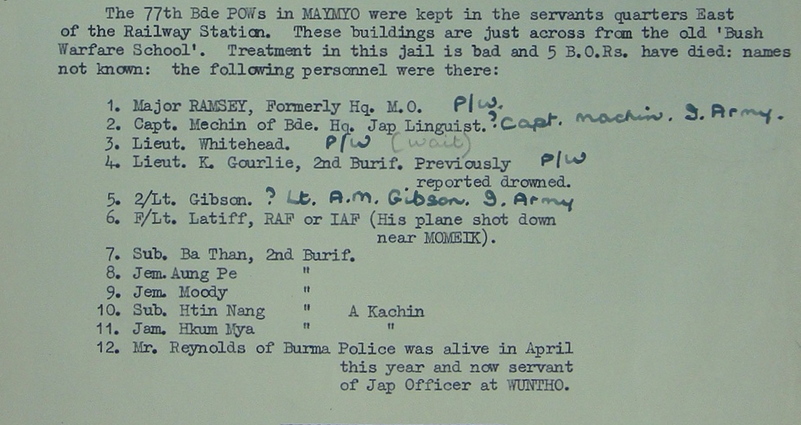

Ba Than led many recce patrols during the operation, including several communications with other columns where he and a small section of Burma Riflemen would leave 5 Column for several days at a time, in order to relay new orders or to share information. After dispersal was called in late March 1943, Subedar Ba Than was with a group that headed north towards Fort Hertz. It is not known how, but he was taken prisoner in the first week of April and sent to the POW concentration camp at Maymyo.

Most of the British Chindit POW's were eventually sent down to Rangoon in June 1943, but many of the Gurkha and Burmese prisoners were used as 'coolie' labour by their Japanese captors, usually looking after transport animals such as mules. They accompanied Japanese patrols as they marched along jungle tracks and this gave frequent opportunities for escape. It is reported that Subedar Ba Than escaped his captors in early 1944 and successfully returned to India.

Jemadar Aung Pe was also a Karen and spent much of his time working in 5 Column Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth. Although not fluent in the English language, Aung Pe struck up a close friendship with Lieutenant Duncan Campbell Menzies on the expedition and accompanied this officer on many occasions when visiting local villages in search of information about enemy numbers and dispositions. In early March 1943, when the column were preparing to demolish the railway bridge at Bonchaung, it was Aung Pe that discovered that there had been a recent outbreak of small pox in the locality, this enabled Fergusson to avoid passing through affected villages such as Peinnegon.

Aung Pe also accompanied Major Fergusson when he was ordered by Brigadier Wingate to liaise with Brigade Head Quarters near the village of Baw in late March. Fergusson left his party near a dry river bed and set out to make the rendezvous with only Naik Jameson for company, but they became hopelessly lost, spending the rest of the evening stumbling back and forth along the chaung. Both men were more than relieved when they bumped into the rest of Column 5 early next morning.

Jemadar Aung Pe eventually suffered the same fate as Ba Than in 1943 and was captured by the Japanese in the first week of April. He too was originally sent to the POW Camp at Maymyo (see image below), before being set to work as an animal driver. He escaped his captors in November 1943 and returned to India. On debrief he gave the welcome news that he had seen Lieutenant Stibbe at Maymyo in late May and that the young officer seemed to have recovered from the gunshot wound he had sustained at the engagement in the village of Hintha.

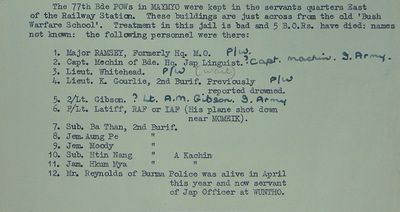

Seen below is part of a report given by a Chindit escapee in 1943. It explains the location of the Maymyo POW Camp and some of the men held there. Apart from Ba Than and Aung Pe, you might also notice the presence of Jemadar Moody on the list, his story is the third to appear on this roll.

From the pages of 'Beyond the Chindwin':

Billy, my Havildar-Major, was a tiny, wizened man, always smiling and very devout, who never went to sleep without first singing softly to himself all three verses of "Jesus loves me, this I know." He was a particular favourite among the British troops.

Havildar-Major Billy was indeed very popular with the other men of 5 Column. He would often sing well known hymns and other religious songs whilst the column marched through Burma. This brought some comfort to the British troops, reminding them of their families and home. Billy was lost to the column after the engagement with the Japanese at Hintha and ended up as a prisoner of war in 1943. Sadly, nothing more was ever heard about this brave Burma Rifleman, although some comfort can be taken in the fact that his name does not appear amongst the casualties from the battalion listed upon the Rangoon Memorial.

Naik Jameson was another favourite from amongst the men of John Fraser's platoon in 1943. Jameson, who spoke excellent English was often used by Fergusson to organise the assistance of Burmese villagers during the early weeks of Operation Longcloth, this included arranging the boats for the column's out-going crossing of the Chindwin River at Hwematte. As mentioned previously on these pages, Naik Jameson was with Major Fergusson when the two became lost on the journey to meet Wingate and the rest of Northern Group Head Quarters at the village of Baw. Fergusson recalled with some humour, how his trusted Naik became exasperated with the poor map-reading skills of his commander, but then failed in his own efforts to extract the pair from the seemingly endless and featureless chaung.

Naik Jameson was by his commander's side when they entered the village of Hintha on the 28th March and was wounded in the shoulder in the resulting battle with the Japanese. After exiting Hintha, 5 Column were again ambushed by the enemy a few hours later whilst crossing a small stream and a section of approximately 100 men were separated from the main body of the unit. Many of the Burma Riflemen were amongst this group and most decided to make for the Kachin Hills and exit Burma via the Yunnan Province of China.

It is recorded that Naik Jameson became a prisoner of war in early April 1943. As with Havildar-Major Billy, nothing more was ever heard about Jameson or his eventual fate after Operation Longcloth was closed. His name does not appear on the list of casualties for the 2nd Burma Rifles during the Burma campaign and so it must be presumed that he escaped or at least survived his captivity and was able to return home after the war.

Rifleman Maung Kyan did not speak much English, but was still an integral part of the 5 Column Burrif platoon in 1943. He was one of the few men available who could speak the majority of Burmese dialects and so was used extensivley as liaison officer when the column entered villages in areas other than those of Kachin origin. Maung Kyan was also an expert forager and had a good knowledge of which plants and fruits were edible from those found along the jungle tracks and pathways. On many occasions during the long daytime marches, British personnel would run up to the Rifleman holding up an array of exotically coloured fruits for his inspection. Often, even before they uttered a word, the diminutive Burman would simply shake his head and wave his hand as if to say, 'no no, throw it away'.

For much of his time on Operation Longcloth Maung Kyan partnered Burrif commander, Captain John Fraser, with the pair moving slightly ahead of the column in order to pre-arrange supplies and rice rations in local villages before the main unit arrived. After the column had crossed the Shweli River in early April, Maung Kyan was chosen by Lieutenant Duncan Campbell Menzies to accompany him and two British Other Ranks on a mission to seek out extra food supplies from a village called Zibyugin.

Disaster struck this small party when a Japanese patrol also entered the village, Lieutenant Menzies and L/Cpl. Gilmartin were killed, but Maung Kyan and 142 Commando, Harry Powell Stephenson escaped. After ensuring that they had not been followed, the two survivors returned to the main group and gave Major Fergusson the devastating news of Menzies and Gilmartin's demise.

Maung Kyan remained with Major Fergusson for the remainder of the operation and was consistently at the head of this dispersal group, as it made its way back to India. On the 24th April, he was, along with Lieutenant Tommy Blow, the first man to re-cross the Chindwin River near the village of Sahpe. Soon afterwards the pair made contact with a local British patrol which had been on the lookout for returning Chindits and in that moment 5 Column's incredible Burmese odyssey was at an end.

Seen below are two images in relation to Rifleman Maung Kyan and his Chindit journey in 1943. Firstly, a fairly well known photograph of Bernard Fergusson and some other 5 Column personnel, including I believe Maung Kyan himself. The other is a map of the area around Chindwin River close to the village of Sahpe. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Another Burrif NCO was wounded during 5 Column's skirmish with the Japanese at the village of Hintha on the 28th March. Naik Nay Dun had been in the thick of the action that day, but had suffered a gunshot wound to his arm. Bernard Fergusson remembered finding the majority of the Burrif platoon on the track leading out of the village, when he returned to the main mustering point for his column after the first phase of the engagement had ended. He wrote in 'Beyond the Chindwin':

Back to the T-junction I went, and found on the right of the track the Burrif platoon. They had two or three casualties from 'overs'; Jameson had one in the shoulder and so did another splendid NCO, Nay Dun, whose name always made me think of a trout fly. I told John Fraser to take them back, but he must have sent them on with Pam Heald, because John remained with me until the end of the action.

It is my guess that most of the Burrif platoon moved away from Hintha under the command of Lieutenant Pam Heald and that he, and most of these men became separated from the main body of 5 Column at the secondary ambush by the enemy a few hours later. Lieutenant Heald eventually made his way out of Burma via the Yunnan Borders, having met up with 7 Column at the Shweli River in early April 1943. It is possible that Nay Dun remained with Heald during this time, as it was confirmed by Fergusson that he succeeded in reaching India despite of his wounded arm.

Rifleman Nelson was from the Karen tribe and became Captain John Fraser's groom during Chindit training at Saugor in November 1942. Fraser's horse was famously unruly, but although the Captain struggled to handle his steed with any confidence, Rifleman Nelson forged a close bond with the animal, teaching himself to ride in the process.

In late March 1943, as 5 Column were making their inaugural crossing of the Irrawaddy at Tigyaing, Fraser's horse was startled by an enemy aircraft and bolted away into the scrub jungle close to the river. Against the better judgement of his superiors, Nelson ran back to try and retrieve the stallion. It is not clear if he succeeded in finding the animal, but Nelson did rejoin the column and cross the Irrawaddy that evening. Rifleman Nelson was taken prisoner at some point during early April and sent up to the POW Camp at Maymyo. It is reported that he escaped sometime in early 1944 and returned India.

Rifleman Pa Haw was from the Tenasserim peninsula, the long tail of Burma that leads directly into Malaya. Bernard Fergusson described him as, "a little wiry smiling chap, who in civilian life had been an 'oozy' or elephant driver." Pa Haw became Captain John Fraser's orderly and was the maker of excellent tea. As with many of the Burrif's from Column 5, he was reported missing shortly after the battle at Hintha and was never heard of again. His name does not appear amongst the list of casualties for the Burma campaign, so with any fortune he too returned home after the war.

Colour Sergeant Po Po Tou (Htoo) was one of the more educated Karen riflemen within the ranks of 5 Column on Operation Longcloth. Before the war he had been studying at the Kitchener College in Nowgong, India and was close to completing his King's Commission. He immediately returned home when the news came through that the Japanese had invaded Burma. His claim to fame, was when he played the part of an outraged Japanese officer, who had been defeated and captured by 5 Column on one of the Chindit field exercises during training. His performance was said to have been almost Shakespearean in its quality!

Po Po Tou was with Major Fergusson and Naik Jameson when the commander first entered the village of Hintha on the 28th March 1943. This was the moment that Fergusson encountered four enemy sentries, who were sitting around a fire in the main thoroughfare of the village and who he first supposed to be Burmese villagers. On realising his error and after one carefully placed grenade, the Japanese were dead and all hell was about to break loose. Po Po Tou is another of the Burrif's lost after dispersal from Hintha and of whom nothing more was heard in 1943. In fact he succeeded in making his way home after a journey of some considerable mileage and a short spell as a prisoner of war. Post war he had an eventful career in the fledgling Burmese Army after the countries independence in 1948.

Update 28/09/2021.

I was delighted to receive the following additional information about Po Po Htoo, from Alfred Dun, the son-in-law of another soldier who served with the 2nd Burma Rifles during the Wingate expeditions, Major Donald Talmadge. Alfred told me:

Grand Uncle Po Po Htoo, also known as, MacArthur Htoo was captured on the first Wingate operation towards the end of March 1943. He was held prisoner with another man, Saw Mutu with their hands tied behind their backs for several days. The Japanese were preparing to execute both men, when all of a sudden and urgent message came into the camp and the officer in charge was drawn away to study field maps on a makeshift bamboo table.

At this critical moment, the two POWs, who had been praying for a miracle were slowly able to loosen themselves from their ropes and finally broke free. Both jumped up and then dashed out into the nearby jungle in an attempt to escape. A salvo of shots rang out behind them, but they kept running and running until the sound of gunfire petered out. Both men lived to return home to their families and to tell their great escape story.

Rifleman Robert often went into villages ahead of the column dressed in his longyi to gather information about the proximity of Japanese patrols and garrisons. In 1943 he took responsibility for reconnaissance of the area between Bonchaung and the approach to Tigyaing. Near the Kunbaung Chaung he arrested a Burmese informer who was in the process of contacting the local enemy agent and disclosing 5 Column's whereabouts. Rifleman Robert is also another of the Burrif's lost after dispersal from the village of Hintha and of whom nothing more is known.

From the book, Return via Rangoon, by Philip Stibbe:

The Burma Riflemen were a cheerful crowd and mostly from the Karen area. One of them called Robert, was so striking and athletic in appearance, we all thought he could have made a fortune in Hollywood. Little did we know during training, just how much we would owe these soldiers later on.

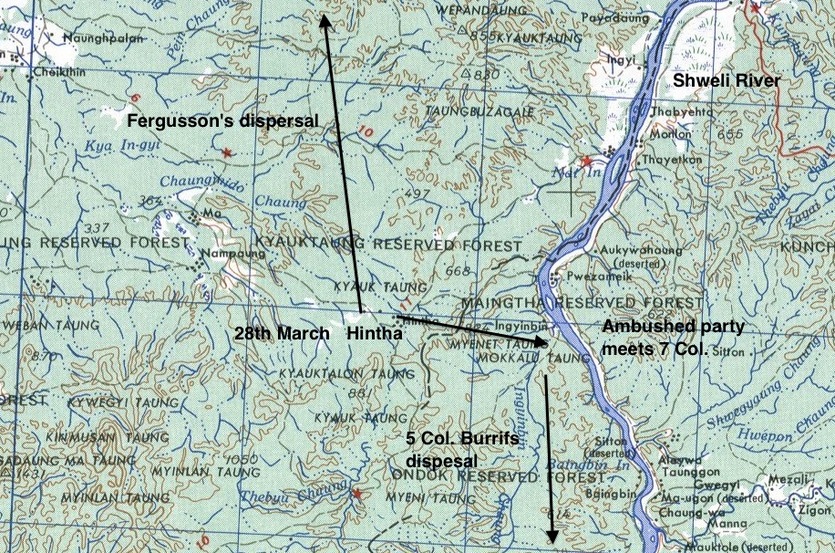

Seen below is a map of the location around the village of Hintha, the scene of 5 Column's disintegration as a complete fighting unit on the 28th March 1943. It shows the splitting of the column after the second ambush by the Japanese after the withdrawal from the village, with Fergusson and Denny Sharp moving north towards the Irrawaddy at Inywa and the ambushed party's more easterly dispersal. Originally, after meeting up with 7 Column at the Shweli, the general consensus was to turn west and make for the Irrawaddy and cross en masse.

It was at this juncture (9th April) that the Burrif's from 5 Column went missing from the amalgamation of the two Chindit columns, disrupting the plans to travel back to India. From the pages of the 7 Column War diary:

Lieutenant Heald took parties off to cross the Irrawaddy. Capt. Cottrell, Lieuts. Walker, Musgrave-Wood and Campbell-Paterson each with 20-30 personnel were to cross independently and then unite for a supply drop on the west side of the river. After just one hour's marching it was discovered the the 5 Column Burrifs were not with the column. Unable to track them, Lieut. Heald considered it advisable to abandon the project in view of there being no Burmese-speaking personnel left to assist the groups in acquiring boats, seeking food or learning about the movements of the enemy. The group turned about and followed the easterly route of Major Gilkes, catching him up near the Nam Mit Chaung.

NB. In fact Lieutenant Rex Walker's party kept faith with the original plan and pushed on westwards towards the Irrawaddy. To read more about this group, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

Back to the T-junction I went, and found on the right of the track the Burrif platoon. They had two or three casualties from 'overs'; Jameson had one in the shoulder and so did another splendid NCO, Nay Dun, whose name always made me think of a trout fly. I told John Fraser to take them back, but he must have sent them on with Pam Heald, because John remained with me until the end of the action.

It is my guess that most of the Burrif platoon moved away from Hintha under the command of Lieutenant Pam Heald and that he, and most of these men became separated from the main body of 5 Column at the secondary ambush by the enemy a few hours later. Lieutenant Heald eventually made his way out of Burma via the Yunnan Borders, having met up with 7 Column at the Shweli River in early April 1943. It is possible that Nay Dun remained with Heald during this time, as it was confirmed by Fergusson that he succeeded in reaching India despite of his wounded arm.

Rifleman Nelson was from the Karen tribe and became Captain John Fraser's groom during Chindit training at Saugor in November 1942. Fraser's horse was famously unruly, but although the Captain struggled to handle his steed with any confidence, Rifleman Nelson forged a close bond with the animal, teaching himself to ride in the process.

In late March 1943, as 5 Column were making their inaugural crossing of the Irrawaddy at Tigyaing, Fraser's horse was startled by an enemy aircraft and bolted away into the scrub jungle close to the river. Against the better judgement of his superiors, Nelson ran back to try and retrieve the stallion. It is not clear if he succeeded in finding the animal, but Nelson did rejoin the column and cross the Irrawaddy that evening. Rifleman Nelson was taken prisoner at some point during early April and sent up to the POW Camp at Maymyo. It is reported that he escaped sometime in early 1944 and returned India.

Rifleman Pa Haw was from the Tenasserim peninsula, the long tail of Burma that leads directly into Malaya. Bernard Fergusson described him as, "a little wiry smiling chap, who in civilian life had been an 'oozy' or elephant driver." Pa Haw became Captain John Fraser's orderly and was the maker of excellent tea. As with many of the Burrif's from Column 5, he was reported missing shortly after the battle at Hintha and was never heard of again. His name does not appear amongst the list of casualties for the Burma campaign, so with any fortune he too returned home after the war.

Colour Sergeant Po Po Tou (Htoo) was one of the more educated Karen riflemen within the ranks of 5 Column on Operation Longcloth. Before the war he had been studying at the Kitchener College in Nowgong, India and was close to completing his King's Commission. He immediately returned home when the news came through that the Japanese had invaded Burma. His claim to fame, was when he played the part of an outraged Japanese officer, who had been defeated and captured by 5 Column on one of the Chindit field exercises during training. His performance was said to have been almost Shakespearean in its quality!

Po Po Tou was with Major Fergusson and Naik Jameson when the commander first entered the village of Hintha on the 28th March 1943. This was the moment that Fergusson encountered four enemy sentries, who were sitting around a fire in the main thoroughfare of the village and who he first supposed to be Burmese villagers. On realising his error and after one carefully placed grenade, the Japanese were dead and all hell was about to break loose. Po Po Tou is another of the Burrif's lost after dispersal from Hintha and of whom nothing more was heard in 1943. In fact he succeeded in making his way home after a journey of some considerable mileage and a short spell as a prisoner of war. Post war he had an eventful career in the fledgling Burmese Army after the countries independence in 1948.

Update 28/09/2021.

I was delighted to receive the following additional information about Po Po Htoo, from Alfred Dun, the son-in-law of another soldier who served with the 2nd Burma Rifles during the Wingate expeditions, Major Donald Talmadge. Alfred told me:

Grand Uncle Po Po Htoo, also known as, MacArthur Htoo was captured on the first Wingate operation towards the end of March 1943. He was held prisoner with another man, Saw Mutu with their hands tied behind their backs for several days. The Japanese were preparing to execute both men, when all of a sudden and urgent message came into the camp and the officer in charge was drawn away to study field maps on a makeshift bamboo table.

At this critical moment, the two POWs, who had been praying for a miracle were slowly able to loosen themselves from their ropes and finally broke free. Both jumped up and then dashed out into the nearby jungle in an attempt to escape. A salvo of shots rang out behind them, but they kept running and running until the sound of gunfire petered out. Both men lived to return home to their families and to tell their great escape story.

Rifleman Robert often went into villages ahead of the column dressed in his longyi to gather information about the proximity of Japanese patrols and garrisons. In 1943 he took responsibility for reconnaissance of the area between Bonchaung and the approach to Tigyaing. Near the Kunbaung Chaung he arrested a Burmese informer who was in the process of contacting the local enemy agent and disclosing 5 Column's whereabouts. Rifleman Robert is also another of the Burrif's lost after dispersal from the village of Hintha and of whom nothing more is known.

From the book, Return via Rangoon, by Philip Stibbe:

The Burma Riflemen were a cheerful crowd and mostly from the Karen area. One of them called Robert, was so striking and athletic in appearance, we all thought he could have made a fortune in Hollywood. Little did we know during training, just how much we would owe these soldiers later on.

Seen below is a map of the location around the village of Hintha, the scene of 5 Column's disintegration as a complete fighting unit on the 28th March 1943. It shows the splitting of the column after the second ambush by the Japanese after the withdrawal from the village, with Fergusson and Denny Sharp moving north towards the Irrawaddy at Inywa and the ambushed party's more easterly dispersal. Originally, after meeting up with 7 Column at the Shweli, the general consensus was to turn west and make for the Irrawaddy and cross en masse.

It was at this juncture (9th April) that the Burrif's from 5 Column went missing from the amalgamation of the two Chindit columns, disrupting the plans to travel back to India. From the pages of the 7 Column War diary:

Lieutenant Heald took parties off to cross the Irrawaddy. Capt. Cottrell, Lieuts. Walker, Musgrave-Wood and Campbell-Paterson each with 20-30 personnel were to cross independently and then unite for a supply drop on the west side of the river. After just one hour's marching it was discovered the the 5 Column Burrifs were not with the column. Unable to track them, Lieut. Heald considered it advisable to abandon the project in view of there being no Burmese-speaking personnel left to assist the groups in acquiring boats, seeking food or learning about the movements of the enemy. The group turned about and followed the easterly route of Major Gilkes, catching him up near the Nam Mit Chaung.

NB. In fact Lieutenant Rex Walker's party kept faith with the original plan and pushed on westwards towards the Irrawaddy. To read more about this group, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

Jemadar San Shwe Htoo led a Burrif sub-section from Colonel Wheeler's Head Quarters and met up with Bernard Fergusson and 5 Column in late March 1943. He was responsible for scouting the areas between Hintha and Pyinlebin for 5 Column and then their crossing of the Shweli River near Tokkin on the 1st April. He was particularly involved in pro-British propaganda when visiting the villages along these routes.

Havildar Tun So Ne was captured by some members of the Burma Independence Army who were still in alliance with the Japanese in 1943. He had entered a village near the Nam Pan Chaung with another Burrif Rifleman in order to ascertain the whereabouts of enemy patrols when he was apprehended. The column had just crossed the Irrawaddy at Tigyaing and news of their progression had obviously gone before them. From the pages of 'Beyond the Chindwin':

Next day's was a dull, hot march, with no water until we reached the Nam Pan Chaung late in the evening, some eight miles above the point where I proposed to have a supply drop. We marched there dispersed in platoons, so as to make the task of anybody following up more difficult. Next day John Fraser re-joined, having regretfully given up all hope of recovering his own patrol. Further inquiries in the village had establish that the Japs had seized two Karens in plain clothes, and it seemed certain that these must be Havildar Tun So Ne and his companion. Gossip said that one of them had escaped, but had he done so he would presumably have come back to us. We were all very sad, because Tun So Ne was one of the best and most popular of all the Karens in the column.

Rifleman Anthony was another of the men captured shortly after the secondary ambush at Hintha on 28th March 1943. He spent the rest of the war inside Rangoon Jail, sharing Block 1 with some of the Chinese prisoners. He was involved in the transfer of prison gossip and news from the Burmese living outside the jail to the senior British officers inside. From the book, 'The Rats of Rangoon' written by Australian Lionel Hudson who took command of the jail after the Japanese evacuated Rangoon in late April 1945:

25th April 1945: A whispered voice from the other side of the wall had told us the story so far: The Japs were burning records, medical and otherwise, and showed other definite indications that they were about to move. The Japs were evacuating Rangoon and possibly Burma altogether. The Emperor's soldiers had put their new clothing stocks on their backs and were throwing away old clothes. And . . . 200 of our men were to be taken away from here with them. Yes, this is it for good or for bad. The ordeal is ahead for us.

A Burmese named Anthony, and an inmate of the Chinese compound, signalled with the aid of his fly swatter (sky writing) that we would be free in two days. The Indians thought we would be free by May 1st. Excited discussion followed. The pregnant position was examined from every angle. Somebody recalled that no working parties had left the gaol today and we noted that work on the roof of the cookhouse had ceased. Yes, it was evident that the Japs were 'taking a powder', but, for the life of us, we could not see how we fitted into the picture.

Once the Japanese had vacated Rangoon, the Allied POW's inside the prison led by Hudson took control of the worn torn city for a short period, eventually making contact with the advancing 14th Army and handing over the reigns to General Slim. Presumably Rifleman Anthony was repatriated to his own tribal area after completing the usual debriefing processes for recovered prisoners of war.

Lance Naik Ba U: From the pages of Beyond the Chindwin:

Some extremely gallant actions were performed by mounted men on different occasions. In February 1943, a young officer of the Burma Rifles by the name of Toye rode forty miles through hostile country from Tonmakeng to Myene to bring Wingate news of Japanese movements; and the following month a corporal in my own Column (and, I am proud to say, from my own county) undertook a hazardous ride on my call for a volunteer.

I had had several men wounded whom I had to leave, and I wanted to get hold of some Burma Riflemen to travel back to the spot (Kyaik-in) where I had left them to induce the local villagers to take them into their care. It was getting dark, and I knew that five miles along a certain track there should be a section of Burrifs. I asked for a volunteer to get on a horse, ride out along the track, which none of us knew, and try to locate this section.

We were just about to blow a bridge on the railway (Bonchaung); we had already been in action that day in the neighbourhood; another column was making trouble a few miles to the south; and all the Japs in the neighbourhood were on the qui vive. It was a job I should have hated myself; but Corporal McGhie volunteered to go, mounted a horse, and rode off into the darkness.

He found the Burrif section, and returned with Lance-Naik Ba U and two men, who went back to the scene of our fight only to find the Japs in possession. I remember thinking, as McGhie rode off, that I was witnessing a brave act, undertaken in cold blood and loneliness. Later in the campaign both McGhie and Ba U became POW's; but Ba U escaped in 1944, McGhie was found in Rangoon in 1945, and I submitted the names of both for the Military Medal. I know McGhie got his, and I hope Ba U was also lucky.

To read more about the men left at the village of Kyaik-in, please click on the following link: The Fighting Men of Kyaik-in

Rifleman Shwe Du was another member of Bernard Fergusson's column on Operation Longcloth. He succeeded in completing the expedition in 1943, travelling back with the dispersal party led by Lieutenant Pam Heald. Sadly, the journey home via the Chinese Borders must have taken its toll on the body of this brave Rifleman, as he died some weeks later on the 24th September. Shwe Du was originally buried at Jhansi in 1943, his remains were later re-interred at Kirkee War Cemetery located near the Indian town of Poona.

Seen below are images of Shwe Du's grave at Kirkee and the War diary entry recording his death. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Jemadar Ah Di was a section leader in Captain Nigel Whitehead's Burrif platoon, part of Chindit Column 8 on Operation Longcloth. When Major Scott, the commander of 8 Column decided it was time to split his unit in to dispersal groups, Ah Di found himself in a party with Captain Whitehead, Flight Officer Wheatley of the RAF and Gurkha Rifles officer, Lieutenant Stuart-Jones. 8 Column took one more supply drop together, then on the 14th April at the Nisan Chaung they waved farewell and broke up into their dispersal parties.

Captain Whitehead's group was considerably larger than most, being made up of around 60-70 men. The reason for this was that he had agreed to take with him a number of sick and wounded men from Platoon 16, many of these soldiers needed to be carried on stretchers and had been battle casualties at the village of Baw on the 23rd March. Whitehead's intention was to find a friendly Kachin village in which to leave these men and then take the rest of his party back to India. After several days of searching no suitable village was found, in fact many of the villages listed on the Captain's map no longer seemed to exist.

It was at this juncture that Lieutenant Stuart-Jones and his platoon of Gurkhas decided to break away from the main group, choosing to head north towards Fort Hertz which was known to still be in Allied hands. The Gurkhas had the good fortune to retain the services of Jemadar Ah Di, on whom they came to depend for their direction, food and most of all, water. Their original intention to head for Fort Hertz was soon compromised by the heavy presence of Japanese patrols in that area. Lieutenant Stuart-Jones decided to continue east and exit Burma via the Chinese Yunnan Borders. The dispersal party eventually reached safety on the 8th July 1943.

Stuart-Jones wrote briefly about his journey out of Burma in 1943 and recognised the valuable contribution made by Jemadar Ah Di:

Having no maps of the area in which we were travelling and only one compass, I had to rely on the knowledge and skill of my Kachin Jemadar, Ah Di of the Burma Rifles. His fluency in the various dialects made him invaluable in obtaining information from villagers. In the hills opposite the east of Bhamo I lost one Kachin and two Karen riflemen, who decided to take their chances and head home. It was also at this time that we picked up Lieutenant Smyly of 5 Column, who was in a very weak state and barely able to walk. He was left in a friendly village, with Jemadar Ah Di instructing the villagers that they would be held responsible for the officers safety.

Everyone was now in a very weak state and at this time the Gurkhas were on average, sticking at it better than the British soldiers and the Burma Rifles. Through the efforts of Ah Di, we hired a Kachin guide who had once been with the Burma Frontier Force. He led us north and entered all villages first to check for Japanese patrols and to acquire rice to supplement our meagre rations. The Kachins in this area were very poor indeed and fearful of the Japs, but on the whole extremely friendly towards us.

2nd Lieutenant V. C. Toye has already been mentioned on this page, this was in reference to his sterling work in riding through the jungles of Burma, keeping the Chindit columns in contact with each other and especially passing on information to Brigadier Wingate in mid-February 1943 when Northern Group were in the vicinity of Tonmakeng. The young officer, formerly with the 5th Mahratta Light Infantry had joined 77th Brigade almost at the last minute on Christmas Eve 1942 and was posted to 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott.

From the pages of Beyond the Chindwin:

On the evening that some of the columns were still crossing the Chindwin, Lt. Toye rode in from Tonmakeng with the news that Colonel Wheeler had arrived there alright. He had information about enemy dispositions which was of great value. Toye's ride, in which he was accompanied by a single orderly, was something of a feat. He had only just joined the Burma Rifles and knew nothing of the language; so that ride of forty odd miles through hostile country was for him no mean undertaking.

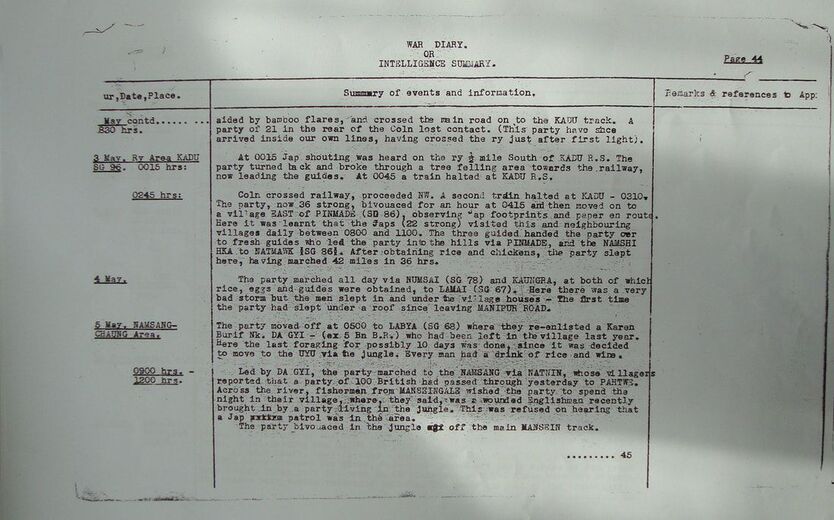

On dispersal in early April, Lieutenant Toye was present with Burma Rifles Head Quarters led by Lieutenant-Colonel Buchanan. By the first week in May this group were in the Kachin Hills and heading roughly northeast. Lieutenant Toye was reportedly, not in the best of health at this time and was mentioned twice in the battalion's War diary in this regard:

May 5th: At Hpau Yung Tingsa, men used grenades to obtain fish from pools. 2nd Lieutenant Toye is going very slowly now and was placed on to a pony.

May 8th: At Tingnan Gahtawng. A local doctor examined 2nd Lieutenant Toye today and ordered him to remain in the village for five days to rest.

It is not known how long the officer remained at Tingnan Gahtawng, but he did eventually return to India in mid-1943 and was present with the 2nd Burma Rifles at Karachi in November. However, it seems clear that he was still unwell, as he was sent to the 14th British General Hospital at Bareilly on the 19th November and then from there to Ranikhet, on India's western borders with Nepal for rest and recuperation. V.C. Toye's promotion to full Lieutenant was gazetted in December 1943, it might be presumed that he returned to his original regiment, the 5th Mahratta's after his period of recuperation ended.

Rifleman Bougyi was a Kachin guide with Chindit Column 8 in 1943 and according to fellow Chindit, Sergeant Tony Aubrey, the Burrif was a very competent and inventive cook. From the pages of 'With Wingate in Burma', Aubrey explains:

Our principal instructors in the not-so-easy art of mess-tin cookery were the men of the Burma Rifles. One of them I remember particularly well, because he was frequently attached to my platoon after we went into action inside Burma. His name was Bougyi, but it wasn't quite so difficult say as it looks, as it was pronounced, quite simply, Boogee. He was a first-class cordon bleu chef wasted, and the things he could turn out of a mess-tin with the aid of a piece of scrag end, a few onions, and some rice, were nobody's business. He also introduced us to the gentle art of making the invaluable chapatti, probably the dullest edible ever invented, but easy to make and sustaining.

Rifleman Bougyi returned safely to India with the main body of 8 Column in late April 1943, within the year he was back inside Burma with the second Chindit expedition.

Rifleman Ba Maung joined the 2nd Burma Rifles in the summer of 1942, after escaping to India during the initial Japanese advance across Burma. In civilian life he was a member of his local Fire Brigade. His Chindit Column placement is unknown.

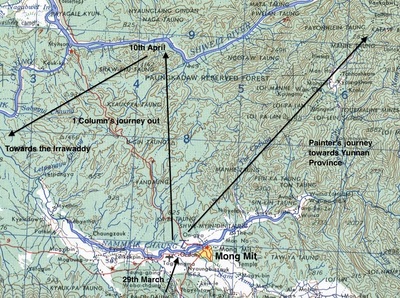

On March 29th 1943 Signals Officer Robin Painter from 1 Column was sent out on a patrol to select a suitable location for an upcoming supply drop. From his book, 'A Signal Honour', he describes his trusted Burrif guide, Havildar Aung Hla:

I had with me a Burrif Havildar (Sergeant) with whom I had worked on a number of previous patrols. His name was Aung Hla and in these circumstances I could not have asked for a better senior NCO. He was a Karen, considerably older than me at about 33 years old and a very experienced soldier who had come out of Burma during the retreat in 1942. He spoke good English and was completely loyal and supportive.

Although Aung Hla was from the Karen tribe, he also spoke jingphaw, one of the Kachin tribal dialects and this particular attribute was to prove vital as time went on. The Havildar guided his party northeast and into the area close to the town of Mong Mit where Colonel Alexander and the main body of 1 Column had hoped to receive one final supply drop, before they attempted to exit Burma via the Chinese Borders. Lieutenant Painter's patrol became separated from the main group and he turned to Aung Hla for advice.

From his book, Painter recalls:

I made the decision to head for the Yunnan Province of China after much discussion with Aung Hla. We considered all the possible options only after a very careful listing of our limited assets and supplies. The first thing I checked was the ration state. We were all in weak physical shape, but hopefully could still march through this difficult terrain.

The small party of Gurkhas with their Burrif guides moved into the Kodaung Hill Tracts, here they were helped by friendly Kachin villagers, offering food, information about the Japanese and supplying local guides to lead the Chindits on to the next village. Lieutenant Painter's health began to falter, apart from him weakening through hunger, he also suffered from bouts of malaria and dysentery. It was from this moment on, that Havildar Aung Hla effectively took command of the dispersal party and it was through his skill and good judgement over the next three weeks, that the group finally reached the Chinese town of Paoshan and the safety of Allied held lines. From Paoshan, the Chindits were taken to a USAAF base and enjoyed the luxury of being flown back to India in Dakota aircraft.

On arrival at Dibrugarh in Assam, Robin Painter and his men became separated, with the Gurkhas and Burma Riflemen being sent on to a Field Hospital at Imphal. Lieutenant Painter remembered:

Sadly, I parted company with my companions, who had been loyal and devoted comrades in times of adversity. I tried to trace them later on, but without success. I also did my utmost to ensure Havildar Aung Hla received some form of recognition for all he had done, but I heard nothing more and fear my recommendation fell on deaf ears. One thing is for sure, without him, I doubt that we would have made it.

Shown below is a photograph of Lieutenant Painter of the Royal Corps of Signals and a map of the area around the Burmese town of Mong Mit, where Aung Hla led his dispersal party away toward the Yunnan Provinces of China. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Captain Whitehead's group was considerably larger than most, being made up of around 60-70 men. The reason for this was that he had agreed to take with him a number of sick and wounded men from Platoon 16, many of these soldiers needed to be carried on stretchers and had been battle casualties at the village of Baw on the 23rd March. Whitehead's intention was to find a friendly Kachin village in which to leave these men and then take the rest of his party back to India. After several days of searching no suitable village was found, in fact many of the villages listed on the Captain's map no longer seemed to exist.

It was at this juncture that Lieutenant Stuart-Jones and his platoon of Gurkhas decided to break away from the main group, choosing to head north towards Fort Hertz which was known to still be in Allied hands. The Gurkhas had the good fortune to retain the services of Jemadar Ah Di, on whom they came to depend for their direction, food and most of all, water. Their original intention to head for Fort Hertz was soon compromised by the heavy presence of Japanese patrols in that area. Lieutenant Stuart-Jones decided to continue east and exit Burma via the Chinese Yunnan Borders. The dispersal party eventually reached safety on the 8th July 1943.

Stuart-Jones wrote briefly about his journey out of Burma in 1943 and recognised the valuable contribution made by Jemadar Ah Di:

Having no maps of the area in which we were travelling and only one compass, I had to rely on the knowledge and skill of my Kachin Jemadar, Ah Di of the Burma Rifles. His fluency in the various dialects made him invaluable in obtaining information from villagers. In the hills opposite the east of Bhamo I lost one Kachin and two Karen riflemen, who decided to take their chances and head home. It was also at this time that we picked up Lieutenant Smyly of 5 Column, who was in a very weak state and barely able to walk. He was left in a friendly village, with Jemadar Ah Di instructing the villagers that they would be held responsible for the officers safety.

Everyone was now in a very weak state and at this time the Gurkhas were on average, sticking at it better than the British soldiers and the Burma Rifles. Through the efforts of Ah Di, we hired a Kachin guide who had once been with the Burma Frontier Force. He led us north and entered all villages first to check for Japanese patrols and to acquire rice to supplement our meagre rations. The Kachins in this area were very poor indeed and fearful of the Japs, but on the whole extremely friendly towards us.

2nd Lieutenant V. C. Toye has already been mentioned on this page, this was in reference to his sterling work in riding through the jungles of Burma, keeping the Chindit columns in contact with each other and especially passing on information to Brigadier Wingate in mid-February 1943 when Northern Group were in the vicinity of Tonmakeng. The young officer, formerly with the 5th Mahratta Light Infantry had joined 77th Brigade almost at the last minute on Christmas Eve 1942 and was posted to 8 Column under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott.

From the pages of Beyond the Chindwin:

On the evening that some of the columns were still crossing the Chindwin, Lt. Toye rode in from Tonmakeng with the news that Colonel Wheeler had arrived there alright. He had information about enemy dispositions which was of great value. Toye's ride, in which he was accompanied by a single orderly, was something of a feat. He had only just joined the Burma Rifles and knew nothing of the language; so that ride of forty odd miles through hostile country was for him no mean undertaking.

On dispersal in early April, Lieutenant Toye was present with Burma Rifles Head Quarters led by Lieutenant-Colonel Buchanan. By the first week in May this group were in the Kachin Hills and heading roughly northeast. Lieutenant Toye was reportedly, not in the best of health at this time and was mentioned twice in the battalion's War diary in this regard:

May 5th: At Hpau Yung Tingsa, men used grenades to obtain fish from pools. 2nd Lieutenant Toye is going very slowly now and was placed on to a pony.

May 8th: At Tingnan Gahtawng. A local doctor examined 2nd Lieutenant Toye today and ordered him to remain in the village for five days to rest.

It is not known how long the officer remained at Tingnan Gahtawng, but he did eventually return to India in mid-1943 and was present with the 2nd Burma Rifles at Karachi in November. However, it seems clear that he was still unwell, as he was sent to the 14th British General Hospital at Bareilly on the 19th November and then from there to Ranikhet, on India's western borders with Nepal for rest and recuperation. V.C. Toye's promotion to full Lieutenant was gazetted in December 1943, it might be presumed that he returned to his original regiment, the 5th Mahratta's after his period of recuperation ended.