Chindits with Four Legs

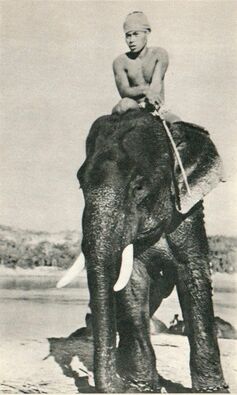

Burmese Oozy (Driver) and his Tusker.

Burmese Oozy (Driver) and his Tusker.

On many occasions during my research reading for Operation Longcloth, I have come across the description of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, as Wingate's Circus. This refers mainly to the way the the Brigade was cobbled together during the latter months of 1942, but also, I'm sure, is a reference to the array of different animals used on the expedition into Burma in 1943. Even the name, Chindit, has an animalistic connotation.

77 Brigade had previously been known simply as the Long Range Penetration Brigade, but Wingate was looking for something much shorter and more appealing, which would sum up exactly what they were out to achieve. Whilst the men rested up at Imphal in January 1943, Wingate asked Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles what the national animal of Burma was and was told that this was the peacock.

Wingate considered the peacock too passive for his requirements and so Aung Thin suggested the Chinthe, the mythical beast, half-lion, half-griffin, whose statues stand guard over the entrance to most Burmese temples and pagodas. Wingate was thrilled, especially as he recognised that the Chinthe symbolised the close link between the ground and the air, which would be necessary for the forthcoming operations against the Japanese. As with many similar cases the name quickly became corrupted by the British troops, ending up as Chindit, although this title would not become fully established until well after the first expedition had ended.

I suppose, if we wanted to push the animal connection to the fullest limit; the Chindits marched through the Burmese jungles in single-file; known by the men themselves as the column snake!

The Elephant (When size really does matter).

At the beginning of WW2, there were roughly 8000 domesticated elephants in Burma, most of which were working for the Burma Corporations involved in the teak logging business. During the course of my research into the first Chindit expedition I have read many books. As a way of broadening my knowledge of the Burma campaign, I chose to investigate the 1950's classic, Elephant Bill. This book was written by James Howard Williams, an elephant expert working for the Bombay-Burmah Trading Corporation at the time of World War 2. Through his long-standing work with elephants, Williams became involved with the 14th Army during the Burma Campaign, reaching the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, being mentioned in dispatches no fewer than three times and eventually being awarded an OBE for his wartime efforts in 1945.

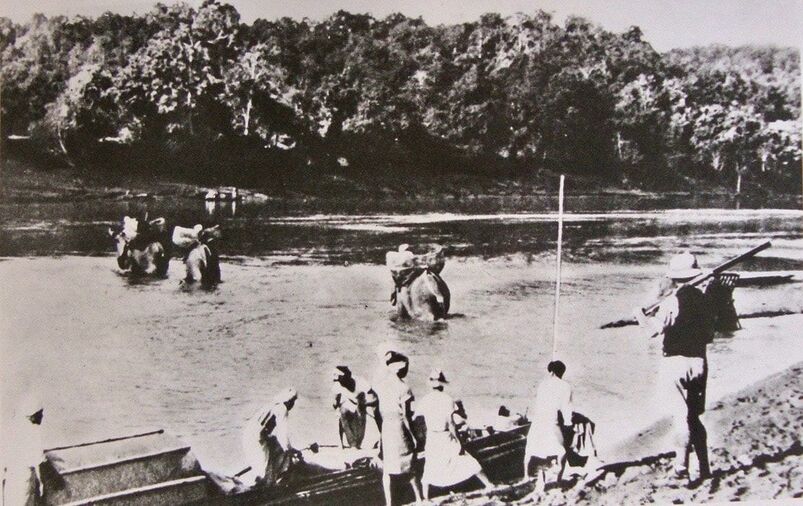

The book Elephant Bill became much more relevant to my research during the second read, when I discovered that Williams had rather reluctantly loaned some of his animals for work on Operation Longcloth. Indeed Williams' second book about his time with elephants, called Bandoola, refers to one of the animals he lent to Wingate in 1943. These animals were only supposed to assist 77 Brigade in the movement of heavy supplies up until the Chindwin River, with each tusker able to carry 800 pounds in weight. Sadly, they were ultimately used to ferry the cargo across the river and one elephant was lost.

I always like to acquire the oldest hardback edition of these sorts of books. The main reason for this is that these often contain excellent photographs and maps, which sadly seem to disappear in later editions. My copy of Elephant Bill has no dust jacket and was an ex-library book printed in 1959, but contained no less than twenty black and white photographs depicting Williams' work with elephants in the teak industry. I also discovered that Williams was great friends with one of the lesser-known officers from Operation Longcloth, Captain Denis Clive Herring, who supplied some of the photographs for the book.

To read more about Elephant Bill and view some of the photographs mentioned, please click on the following link: Elephant Bill Williams

In reference to the elephant that was lost during the transportation of the Chindit supplies across the Chindwin River in February 1943, here is a quote explaining the incident, taken from the pages of Mike Calvert's book, Prisoners of Hope:

I remember one column had an interesting experience with an elephant when they were trying to cross the Chindwin River. Eventually they chose as as their crossing place a point where a sandy spit stretched out three-quarters of the way across the river. For the rest of the journey the elephant and its mahout, carrying the column wireless and battery charger, swam casually across to the other side. This gave the column commander and idea. He was having great difficulty in getting his men and stores across, owing to the swift current and the inadequacies of the boats at his disposal.

So he recalled the elephant, loaded it up and it swam over again. This occurred two or three times more with ever increasing loads, until eventually, as the elephant stepped off into the deep water, he missed his footing and capsized. He floated downstream, the load acting as a keel, with his four legs and trunk waving idly in the air. Thankfully he could still breathe as long as he kept his mouth shut.

A Canadian officer, with great presence of mind, ran downstream, plunged into the water, sat on the creatures belly and with the elephant behaving correctly the whole time, cut the girth strap. The elephant then righted himself, spurted one long jet of water through his trunk and made quietly for the shore, where he awaited his mahout. As McKenzie, the Canadian officer passed by, the elephant gave him a wink and that was his only apparent sign of emotion.

During the second week of the expedition and after all the original elephants had been withdrawn back to India, Mike Calvert and No. 3 Column managed to acquire another animal near the Burmese village of Sinlamaung. The column had taken their first supply drop the day before and were now exploring the country around the Sinlamaung in search of enemy patrols. They reached an outpost, which had only recently been vacated by the enemy to find an elephant and its oozy, or handler waiting at the camp for the Japanese patrol's return. Calvert commandeered the elephant, which No. 3 Column named, Flossie and elephant and oozy remained with the column for several weeks.

Many Chindits learned on Operation Longcloth, that if fresh elephant droppings were encountered along a track, that this would often mean two things: firstly, the possibility of Japanese patrols in the area, as they were known to use elephants for this purpose, and secondly that if the droppings were fresh, there was a great chance that drinking water might be nearby. In fact a four-line ditty was composed on this very subject, by two officers from No. 5 Column: Lt. William Edge and Lt. Philip Stibbe:

77 Brigade had previously been known simply as the Long Range Penetration Brigade, but Wingate was looking for something much shorter and more appealing, which would sum up exactly what they were out to achieve. Whilst the men rested up at Imphal in January 1943, Wingate asked Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles what the national animal of Burma was and was told that this was the peacock.

Wingate considered the peacock too passive for his requirements and so Aung Thin suggested the Chinthe, the mythical beast, half-lion, half-griffin, whose statues stand guard over the entrance to most Burmese temples and pagodas. Wingate was thrilled, especially as he recognised that the Chinthe symbolised the close link between the ground and the air, which would be necessary for the forthcoming operations against the Japanese. As with many similar cases the name quickly became corrupted by the British troops, ending up as Chindit, although this title would not become fully established until well after the first expedition had ended.

I suppose, if we wanted to push the animal connection to the fullest limit; the Chindits marched through the Burmese jungles in single-file; known by the men themselves as the column snake!

The Elephant (When size really does matter).

At the beginning of WW2, there were roughly 8000 domesticated elephants in Burma, most of which were working for the Burma Corporations involved in the teak logging business. During the course of my research into the first Chindit expedition I have read many books. As a way of broadening my knowledge of the Burma campaign, I chose to investigate the 1950's classic, Elephant Bill. This book was written by James Howard Williams, an elephant expert working for the Bombay-Burmah Trading Corporation at the time of World War 2. Through his long-standing work with elephants, Williams became involved with the 14th Army during the Burma Campaign, reaching the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, being mentioned in dispatches no fewer than three times and eventually being awarded an OBE for his wartime efforts in 1945.

The book Elephant Bill became much more relevant to my research during the second read, when I discovered that Williams had rather reluctantly loaned some of his animals for work on Operation Longcloth. Indeed Williams' second book about his time with elephants, called Bandoola, refers to one of the animals he lent to Wingate in 1943. These animals were only supposed to assist 77 Brigade in the movement of heavy supplies up until the Chindwin River, with each tusker able to carry 800 pounds in weight. Sadly, they were ultimately used to ferry the cargo across the river and one elephant was lost.

I always like to acquire the oldest hardback edition of these sorts of books. The main reason for this is that these often contain excellent photographs and maps, which sadly seem to disappear in later editions. My copy of Elephant Bill has no dust jacket and was an ex-library book printed in 1959, but contained no less than twenty black and white photographs depicting Williams' work with elephants in the teak industry. I also discovered that Williams was great friends with one of the lesser-known officers from Operation Longcloth, Captain Denis Clive Herring, who supplied some of the photographs for the book.

To read more about Elephant Bill and view some of the photographs mentioned, please click on the following link: Elephant Bill Williams

In reference to the elephant that was lost during the transportation of the Chindit supplies across the Chindwin River in February 1943, here is a quote explaining the incident, taken from the pages of Mike Calvert's book, Prisoners of Hope:

I remember one column had an interesting experience with an elephant when they were trying to cross the Chindwin River. Eventually they chose as as their crossing place a point where a sandy spit stretched out three-quarters of the way across the river. For the rest of the journey the elephant and its mahout, carrying the column wireless and battery charger, swam casually across to the other side. This gave the column commander and idea. He was having great difficulty in getting his men and stores across, owing to the swift current and the inadequacies of the boats at his disposal.

So he recalled the elephant, loaded it up and it swam over again. This occurred two or three times more with ever increasing loads, until eventually, as the elephant stepped off into the deep water, he missed his footing and capsized. He floated downstream, the load acting as a keel, with his four legs and trunk waving idly in the air. Thankfully he could still breathe as long as he kept his mouth shut.

A Canadian officer, with great presence of mind, ran downstream, plunged into the water, sat on the creatures belly and with the elephant behaving correctly the whole time, cut the girth strap. The elephant then righted himself, spurted one long jet of water through his trunk and made quietly for the shore, where he awaited his mahout. As McKenzie, the Canadian officer passed by, the elephant gave him a wink and that was his only apparent sign of emotion.

During the second week of the expedition and after all the original elephants had been withdrawn back to India, Mike Calvert and No. 3 Column managed to acquire another animal near the Burmese village of Sinlamaung. The column had taken their first supply drop the day before and were now exploring the country around the Sinlamaung in search of enemy patrols. They reached an outpost, which had only recently been vacated by the enemy to find an elephant and its oozy, or handler waiting at the camp for the Japanese patrol's return. Calvert commandeered the elephant, which No. 3 Column named, Flossie and elephant and oozy remained with the column for several weeks.

Many Chindits learned on Operation Longcloth, that if fresh elephant droppings were encountered along a track, that this would often mean two things: firstly, the possibility of Japanese patrols in the area, as they were known to use elephants for this purpose, and secondly that if the droppings were fresh, there was a great chance that drinking water might be nearby. In fact a four-line ditty was composed on this very subject, by two officers from No. 5 Column: Lt. William Edge and Lt. Philip Stibbe:

If elephant droppings are brown and hard

Your plans for bivouac will be marred;

But if elephant droppings are soft and moist,

Then you'll find water to quench your t'oist.

Your plans for bivouac will be marred;

But if elephant droppings are soft and moist,

Then you'll find water to quench your t'oist.

In his book describing the second Chindit expedition, Wild Green Earth, Bernard Fergusson had this to say about the use of elephants:

Elephants are more vulnerable than mules to the criticism, that their feeding problems outweigh their usefulness. However, they can carry great weights and are remarkably agile in what they can tackle; they make splendid pioneers, crashing down thick jungle in a few minutes, which would have taken a gang of slashers several hours. But my knowledge of elephants is entirely hearsay and I had better not talk about them any more for fear of uttering some solecism.

Elephants are more vulnerable than mules to the criticism, that their feeding problems outweigh their usefulness. However, they can carry great weights and are remarkably agile in what they can tackle; they make splendid pioneers, crashing down thick jungle in a few minutes, which would have taken a gang of slashers several hours. But my knowledge of elephants is entirely hearsay and I had better not talk about them any more for fear of uttering some solecism.

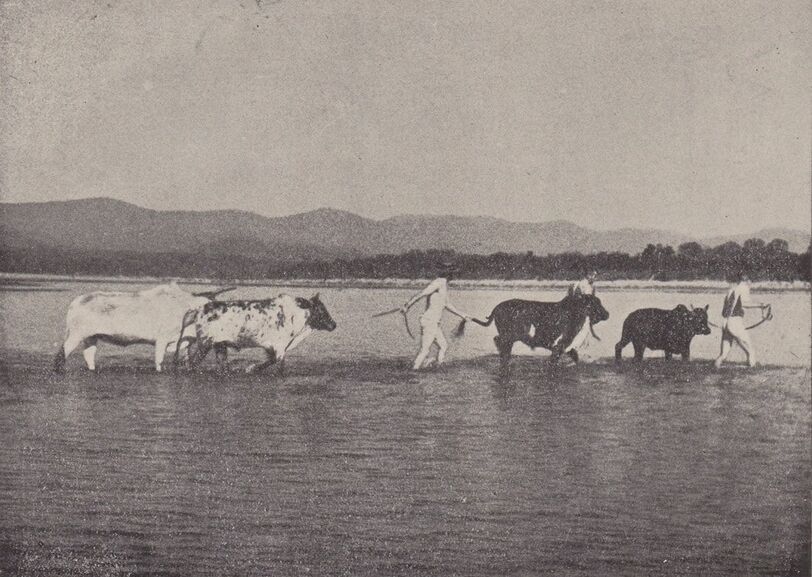

The Bullock (Meat on the hoof).

From Bernard Fergusson's Wild Green Earth:

Pack bullocks are by no means to be despised. Their great virtue lies in their independence of grooming: they take no looking after, and a bullocketeer (a horrible word which I am ashamed to admit having coined) had nothing to do but prod the animal along with a stick. They offer no forage problem, since they graze contentedly on whatever offers. They are slow movers, slower than mules; but the average speed of a column is so liable to constant checks and minor halts that they do not really impose much delay on one's movement as a whole.

They have two principal limitations: first, the extreme difficulty of fitting a saddle to them; and secondly, they cannot carry more than about thirty pounds a side, as opposed to seventy a side on a small mule and ninety on a large. But—and this is a big but—they constitute a welcome reserve of meat on the hoof, and a little beef a few hundred miles into Burma is thoroughly welcome.

In 1943, I took three pack bullocks to carry extra forage for the mules, and we ate them all before we reached the Irrawaddy on the outward journey. I felt a bit of a cad eating them after all they had done for us; but that did not deter me from giving the order. Like the Walrus, I held my pocket-handkerchief before my streaming eyes; and like the Carpenter, I kept asking for another slice. The bullocketeers felt little pity for their charges, however; they were hurt by the complete coldness shown to them by the bullocks whom they had prodded so far. The mules were quick to distinguish between their own muleteers and the other two-footed animals around them; the bullocks remained supremely indifferent, and so died unlamented.

People laughed at our bullocks, as we marched them up the Manipur Road; they seemed to think that they added the last comedy touch to a comedy farce. They were wrong. If some of the formations on that front, who proclaimed so loudly that they were bogged down by lack of mules, had tried out bullocks, they would have found them excellent substitutes. Although they would have had limitations in forward areas, they could profitably have been used to replace mules in the back areas, thus making the mules available for the front line.

The slow pace and cumbersome nature of the Chindit bullock, made this beast an unpopular responsibility for the men ordered to look after them. The soldier given the task of firstly acquiring these animals and then setting up a regime for their care and welfare, was Lieutenant James Vernon Crispin Molesworth, formerly of the Duke of Cornwall's Regiment and prior to his role as Animal Transport Officer on Operation Longcloth, a member of 142 Commando. Even before the expedition had truly began, many of the bullocks suffered some sort of illness or malaise at the Imphal camp and several had perished from this mysterious complaint.

Sergeant Tony Aubrey of No. 8 Column remembered Lieutenant Molesworth in the pages of his book, With Wingate in Burma. Aubrey recalled the build up of supplies and pack animals just before the Chindit Brigade moved off into Burma and were gathering together at Imphal in the state of Assam:

Next day, we reached Imphal, still riding in comfort, thanks to the generosity of our hosts with their transport. In Imphal, we found that one of the officers from our unit had started a bullock farm, and we parked ourselves there to give him a hand while Captain Herring went off to headquarters to make his report.

Mr. Molesworth had come up to Imphal with instructions to get together a herd of some 200 bullocks. He had been a farmer at home, and knew what he was doing. At first he had picked up the animals reasonably cheaply, but when the surrounding zemindars (Indian District landowners) got wise to the fact that he had to have them, up went the price. One or two of them in their earnest desire for profit went so far as to sell their bullocks to Mr. Molesworth, have them stolen back from him and artistically repainted, and then sell them back to him at an increased price, of course, to cover the outlay on paint.

We had some fun with these bullocks. We had to train them to wear a harness, consisting of a sort of horse-cloth with two girths, a tail strap, and saddle bags, and they didn't like it at first. In their desire to get rid of it they went through the most extraordinary gyrations, not at all suited to their bulk and dignity. But after a few days they settled down and gave no more trouble.

Pte. Frank Holland of No. 8 Column was placed in charge of his unit's bullocks in 1943, he recalled:

The powers that be then decided as I came from a farm I had better take charge of the bullocks. There were twenty seven of them, some with carts the rest with packs and they were only partly broken in to cart and pack work, so much swearing and pushing was needed to get them up the big hills. The country side changed all the time, sometimes paddy fields and then thickly clad mountains with bamboo and scrub. Some of the hills had hanging tea gardens. It was a job to take it all in as we were marching between fifteen and thirty miles each day. These various distances were between staging camps where you got fed and rested.

We arrived at Imphal and rested up for a while. This was a chance to wash clothes and bath in the river. We were given some new bullocks to break in, fine beasts from the Naga Hills, but with no desire to loose their freedom and work for us. It took a while to get them tamed down and working but their fight for freedom was foremost in their minds.

I’ve forgotten many of the stages, but one stands out very vividly, the night of the thunderstorm, the torrential rain and lightening was unbelievable, many different colours a wonderful but almost frightening sight in its intensity. We heard and saw many baboons during the day but at night it was the croak of frogs and the click of cicadas. We followed on to Tamu and then left the dirt road and took to jungle tracks. The bullocks were slower than the mules, so we had got a long way behind the column by now and had to sacrifice sleep to try and catch up.

We were now joined by four elephants and their drivers, I learned something from them that night when we stopped for a break. To boil water for tea they cut a length of bamboo, filled it with water and stood it in the fire to boil and it worked. That night was very hard, very dark and some very narrow paths along a ravine. Several times I was asked to go down and shoot horses and mules that had fallen over. It sounds strange but the lads just didn’t really know how to destroy an animal as big as a horse, but it had to be done to save it from suffering. When daylight came the track improved and we saw huts now and then. We were getting into real bamboo country. The day was easier, but the night again was bad, very dark and bad narrow paths.

To make things worse a message had been sent back, for us to press on hard and try to catch up ready to cross the Chindwin River. But it didn’t work out because things became so bad we had to call a halt and rest. We set off very early next morning and arrived at the river by four a.m. The crossing had started but the chargers and mules were refusing to cross. Major Scott our Column Commander came along and asked us to try the bullocks and elephants as soon as we had eaten.

The scene was beautiful, big sandy stretches like the seaside, but the thought of what might be waiting on the other side took some of the shine away. We stripped naked and set off to cross, the bullock liked the water so we waded out with them for about thirty yards and then the current took over, it was frightening it swept your legs away and you could only go with it. The bullocks could swim like fish so we hung on to their tails, my mate Teddy Gale was swept away, but after a while was picked up by a Burman in a dugout canoe.

The whole of that day was spent dragging mules into the water and then climbing into a dugout and been paddled across with a string of four mules swimming behind. We had got everything across by seven at night, twelve hours behind time. During the crossing one of the elephants was turned upside down by the weight of its load a Burman swam out and cut its load free and the elephant swam ashore.

Some weeks later, after an engagement with the Japanese at a place called Pinlebu, I was asked to kill the first bullock for the column to eat. I agreed but was quite taken back when told I must not shoot it as the Japs were too near, so I had to poll axe it and then skin it. Before we could eat any of the meat my section were asked to assist in putting down a road block and to help bring in some Gurkha stragglers, who had become separated. Just after dark we heard movement across the road in the jungle, so half of us went to intercept. It was a very uncomfortable as we could hear talking but it was not English. We got in close and recognised them as Gurkhas. We showed them back into their column and were asked if we would stay out there till morning. We moved back to our position the next morning but everyone had gone, so we got none of the meat.

Sergeant Tony Aubrey of No. 8 Column remembered Lieutenant Molesworth in the pages of his book, With Wingate in Burma. Aubrey recalled the build up of supplies and pack animals just before the Chindit Brigade moved off into Burma and were gathering together at Imphal in the state of Assam:

Next day, we reached Imphal, still riding in comfort, thanks to the generosity of our hosts with their transport. In Imphal, we found that one of the officers from our unit had started a bullock farm, and we parked ourselves there to give him a hand while Captain Herring went off to headquarters to make his report.

Mr. Molesworth had come up to Imphal with instructions to get together a herd of some 200 bullocks. He had been a farmer at home, and knew what he was doing. At first he had picked up the animals reasonably cheaply, but when the surrounding zemindars (Indian District landowners) got wise to the fact that he had to have them, up went the price. One or two of them in their earnest desire for profit went so far as to sell their bullocks to Mr. Molesworth, have them stolen back from him and artistically repainted, and then sell them back to him at an increased price, of course, to cover the outlay on paint.

We had some fun with these bullocks. We had to train them to wear a harness, consisting of a sort of horse-cloth with two girths, a tail strap, and saddle bags, and they didn't like it at first. In their desire to get rid of it they went through the most extraordinary gyrations, not at all suited to their bulk and dignity. But after a few days they settled down and gave no more trouble.

Pte. Frank Holland of No. 8 Column was placed in charge of his unit's bullocks in 1943, he recalled:

The powers that be then decided as I came from a farm I had better take charge of the bullocks. There were twenty seven of them, some with carts the rest with packs and they were only partly broken in to cart and pack work, so much swearing and pushing was needed to get them up the big hills. The country side changed all the time, sometimes paddy fields and then thickly clad mountains with bamboo and scrub. Some of the hills had hanging tea gardens. It was a job to take it all in as we were marching between fifteen and thirty miles each day. These various distances were between staging camps where you got fed and rested.

We arrived at Imphal and rested up for a while. This was a chance to wash clothes and bath in the river. We were given some new bullocks to break in, fine beasts from the Naga Hills, but with no desire to loose their freedom and work for us. It took a while to get them tamed down and working but their fight for freedom was foremost in their minds.

I’ve forgotten many of the stages, but one stands out very vividly, the night of the thunderstorm, the torrential rain and lightening was unbelievable, many different colours a wonderful but almost frightening sight in its intensity. We heard and saw many baboons during the day but at night it was the croak of frogs and the click of cicadas. We followed on to Tamu and then left the dirt road and took to jungle tracks. The bullocks were slower than the mules, so we had got a long way behind the column by now and had to sacrifice sleep to try and catch up.

We were now joined by four elephants and their drivers, I learned something from them that night when we stopped for a break. To boil water for tea they cut a length of bamboo, filled it with water and stood it in the fire to boil and it worked. That night was very hard, very dark and some very narrow paths along a ravine. Several times I was asked to go down and shoot horses and mules that had fallen over. It sounds strange but the lads just didn’t really know how to destroy an animal as big as a horse, but it had to be done to save it from suffering. When daylight came the track improved and we saw huts now and then. We were getting into real bamboo country. The day was easier, but the night again was bad, very dark and bad narrow paths.

To make things worse a message had been sent back, for us to press on hard and try to catch up ready to cross the Chindwin River. But it didn’t work out because things became so bad we had to call a halt and rest. We set off very early next morning and arrived at the river by four a.m. The crossing had started but the chargers and mules were refusing to cross. Major Scott our Column Commander came along and asked us to try the bullocks and elephants as soon as we had eaten.

The scene was beautiful, big sandy stretches like the seaside, but the thought of what might be waiting on the other side took some of the shine away. We stripped naked and set off to cross, the bullock liked the water so we waded out with them for about thirty yards and then the current took over, it was frightening it swept your legs away and you could only go with it. The bullocks could swim like fish so we hung on to their tails, my mate Teddy Gale was swept away, but after a while was picked up by a Burman in a dugout canoe.

The whole of that day was spent dragging mules into the water and then climbing into a dugout and been paddled across with a string of four mules swimming behind. We had got everything across by seven at night, twelve hours behind time. During the crossing one of the elephants was turned upside down by the weight of its load a Burman swam out and cut its load free and the elephant swam ashore.

Some weeks later, after an engagement with the Japanese at a place called Pinlebu, I was asked to kill the first bullock for the column to eat. I agreed but was quite taken back when told I must not shoot it as the Japs were too near, so I had to poll axe it and then skin it. Before we could eat any of the meat my section were asked to assist in putting down a road block and to help bring in some Gurkha stragglers, who had become separated. Just after dark we heard movement across the road in the jungle, so half of us went to intercept. It was a very uncomfortable as we could hear talking but it was not English. We got in close and recognised them as Gurkhas. We showed them back into their column and were asked if we would stay out there till morning. We moved back to our position the next morning but everyone had gone, so we got none of the meat.

Pte. Henry James Ackerman.

Pte. Henry James Ackerman.

In his book about the first Chindit expedition entitled, Beyond the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson remembered one of his bullockteers, namely Pte. Henry Ackerman formerly of the Royal Welch Fusiliers:

One of the bullock drivers was Akerman, a little Welshman with whom I often passed the time of day. He used to stump along with an old pipe stuck in his mouth; in accordance with the custom of my own regiment, I always allowed pipes on the line of march. Once I asked him how he was getting along with his bullock. He replied, in his sing-song Welsh voice: "Sir, I am so bewildered, I do not know now which is the bullock, myself or the bullock."

Another officer from No. 5 Column, Lieutenant Philip Stibbe, also remembered Pte. Ackerman. In his own book, Return via Rangoon, Stibbe recalls the long march from Imphal down to the banks of the Chindwin River in February 1943:

Stretched out in single file the column was over half a mile long. It was a fine sight and the men were in good heart that night. I waited until the Perimeter Platoon had gone by and then prepared to follow on a few hundred yards behind. Just at that moment I heard a musical Welsh voice indulging in a delightful flow of bad language and round the corner came Private Ackerman and his bullocks.

These bullocks were a last minute addition of Wingate's and with specially constructed carts, they proved extremely useful for carrying extra loads and eventually for eating purposes. That evening Ackerman and his band of bullockteers were finding them troublesome. They never liked going up hill and later on one of them lay down and refused to budge an inch until a fire was lit under its tail. We then had difficulty in preventing the animal from overtaking the Major!

NB. Sadly, Pte. Ackerman did not return home from Burma after the war, having died as a prisoner of war inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on 22nd August 1943. To read more about Henry Ackerman, please click on the following link: Pte. Henry James Ackerman

I will leave the last word on the subject of bullocks, to Captain Leslie Cottrell, the Adjutant for No. 7 Column during the first Chindit expedition in 1943:

At midnight on 13th February 1943 we reached the River Chindwin, where we were at once confronted with a major problem. How to get one hundred and thirty animals across a swiftly flowing river which is a quarter of a mile wide? The few bullocks with our column did the trick. The men bellowed and waved their arms about, the bullocks entered the water and the other animals, mules and horses, followed. One officer finished up hanging on to a bullock's tail for the crossing and arrived naked on the east bank as night fell. Fortunately for him, his batman turned up with his clothes about two hours later.

One of the bullock drivers was Akerman, a little Welshman with whom I often passed the time of day. He used to stump along with an old pipe stuck in his mouth; in accordance with the custom of my own regiment, I always allowed pipes on the line of march. Once I asked him how he was getting along with his bullock. He replied, in his sing-song Welsh voice: "Sir, I am so bewildered, I do not know now which is the bullock, myself or the bullock."

Another officer from No. 5 Column, Lieutenant Philip Stibbe, also remembered Pte. Ackerman. In his own book, Return via Rangoon, Stibbe recalls the long march from Imphal down to the banks of the Chindwin River in February 1943:

Stretched out in single file the column was over half a mile long. It was a fine sight and the men were in good heart that night. I waited until the Perimeter Platoon had gone by and then prepared to follow on a few hundred yards behind. Just at that moment I heard a musical Welsh voice indulging in a delightful flow of bad language and round the corner came Private Ackerman and his bullocks.

These bullocks were a last minute addition of Wingate's and with specially constructed carts, they proved extremely useful for carrying extra loads and eventually for eating purposes. That evening Ackerman and his band of bullockteers were finding them troublesome. They never liked going up hill and later on one of them lay down and refused to budge an inch until a fire was lit under its tail. We then had difficulty in preventing the animal from overtaking the Major!

NB. Sadly, Pte. Ackerman did not return home from Burma after the war, having died as a prisoner of war inside Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on 22nd August 1943. To read more about Henry Ackerman, please click on the following link: Pte. Henry James Ackerman

I will leave the last word on the subject of bullocks, to Captain Leslie Cottrell, the Adjutant for No. 7 Column during the first Chindit expedition in 1943:

At midnight on 13th February 1943 we reached the River Chindwin, where we were at once confronted with a major problem. How to get one hundred and thirty animals across a swiftly flowing river which is a quarter of a mile wide? The few bullocks with our column did the trick. The men bellowed and waved their arms about, the bullocks entered the water and the other animals, mules and horses, followed. One officer finished up hanging on to a bullock's tail for the crossing and arrived naked on the east bank as night fell. Fortunately for him, his batman turned up with his clothes about two hours later.

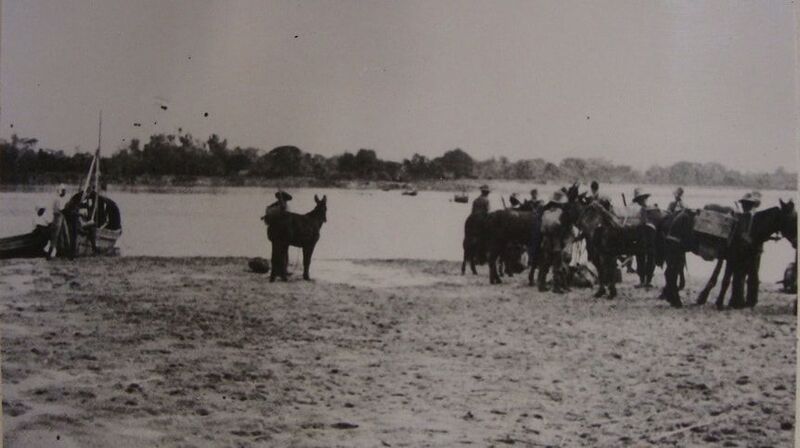

Horses and Ponies (For Officers Only).

From the book, Fighting Mad, by Mike Calvert:

Wingate always enjoyed horse riding and eventually taught me to enjoy it too. I had learned to ride at the Royal Military Academy, but the strict, and I thought, stupid methods of the instructors there had put me off. It was something I had to do to pass out, but it was nothing more for me until I took it up again in India. When we went out with Wingate our rides were exciting, interesting and instructive and the horses seemed to react to our keen mood.

Orde Wingate had learned to ride as a young man, but had really taken up the sport during his early training days with the Royal Artillery, regularly entering and often winning cross-country and point to point meetings in the Wiltshire countryside during the late 1920's. From his love and experience with these animals, Wingate insisted that all his officers during the first Chindit expedition learn to ride a charger, astride which they would enter Burma ahead of their men.

Bernard Fergusson in his book, Wild Green Earth, remembered:

Our horses and ponies eventually were used for carrying casualties in Burma. The Animal Transport Officer and his Sergeant were usually mounted and they were the only individuals who had horses as of right; others requiring them asked the ATO, who then allotted one for their immediate need. We used them to carry the packs and equipment of men who were sick, but not sick enough to ride; it was the brutal truth that many men got better more quickly if they were kept moving; and the mere reprieve from carrying one's pack was almost enough in itself to effect a cure.

Horses were also useful for intercommunication between columns. Some extremely gallant actions were performed by mounted men on different occasions. In February 1943, a young officer from the Burma Rifles by the name of Toye, rode forty miles through hostile country from Tonmakeng to Myene to bring Wingate news of Japanese movements. The following month one of my own Corporals, (McGee) undertook a hazardous ride on my call, in the aid of several wounded men whom I had to leave in a local village outside Bonchaung.

As No. 5 Column were preparing to cross the Chindwin River in mid-February, Animal Transport Officer, Lt. Bill Smyly recalled the excellent performance of his beloved charger, who he had named, Sambo:

The Chindwin was crossed without much difficulty, for we took two ropes across at night and ferried over the river, hand over hand, in Royal Engineer boats, like huge inner tubes with a canvas floor, or rafts supported by the tiny RAF boats, which float but are not much use for anything else. The mules and horses which were fit, swam across in droves, the fearful ones going across tied to our RE boats and the willing ones going over in droves of 15 to 20 at a time.

I was the last across, because the animals were my property, but, after a long and gloriously happy day, working in naked in the baking sun, I dispatched my saddle and clothes with the Groom, tied up my reins to a surcingle and rode across on Sambo’s back. He was a beautiful prancing gelding of 16 hands and a half, and was one of the finest, strongest beasts I have ever seen. He swam with his head held high and the water surged round his flanks, swirled round my legs and his long tail trailed out in his wake. We caught up and passed an RE boat and seemed to be going twice as fast.

Sadly, Bill's horse did not survive Operation Longcloth, in fact to my knowledge none of the horses or ponies taken into Burma that year ever returned to India.

Another Animal Transport Officer on Operation Longcloth was, Lt. Dominic Neill of No. 8 Column. He remembered his Section Sergeant and his own beloved charger, Red Wagon in an unpublished memoir recounting his adventures on the first Wingate expedition:

Sgt. Ormandy's knowledge of horses if not mules was complete. In the coming months he was to be of the greatest assistance to me, as he taught me so much about caring for both horses and mules, I was much in his debt during those days. He helped me with my own charger Red Wagon' a beautiful dark chestnut stallion with a white blaze across his forehead. Our commander, Major Scott of the King's Regiment had ordered Ormandy and I to ride up and down the column lines during these early marches, in order to check on the progress and behaviour of the mules, it was during these moments that I learned much about my horse. My Syce (Groom), 67892 Dalbir Thapa, who had come to us from the 6th Gurkhas, had become devoted to his charge and had re-christened him 'Rate', as he said his coat was the colour of a Nepalese Barking Deer. And so he became Rate to us both from that moment on.

In the end, as the expedition began to unravel, No. 8 Column broke up into small dispersal parties at the Irrawaddy in mid-April 1943. Column Commander, Major Scott ordered that all remaining mules and horses be turned loose at this point. With tears in his eyes, Dominic Neill attempted to leave his horse with a group of mules in a jungle clearing. For many hours, Rate continued to follow his master, and was never fully out of sight for most of the next day. Eventually, for one reason or another he stopped following the Chindit party and disappeared into the jungle, never to be seen again.

From the book, Fighting Mad, by Mike Calvert:

Wingate always enjoyed horse riding and eventually taught me to enjoy it too. I had learned to ride at the Royal Military Academy, but the strict, and I thought, stupid methods of the instructors there had put me off. It was something I had to do to pass out, but it was nothing more for me until I took it up again in India. When we went out with Wingate our rides were exciting, interesting and instructive and the horses seemed to react to our keen mood.

Orde Wingate had learned to ride as a young man, but had really taken up the sport during his early training days with the Royal Artillery, regularly entering and often winning cross-country and point to point meetings in the Wiltshire countryside during the late 1920's. From his love and experience with these animals, Wingate insisted that all his officers during the first Chindit expedition learn to ride a charger, astride which they would enter Burma ahead of their men.

Bernard Fergusson in his book, Wild Green Earth, remembered:

Our horses and ponies eventually were used for carrying casualties in Burma. The Animal Transport Officer and his Sergeant were usually mounted and they were the only individuals who had horses as of right; others requiring them asked the ATO, who then allotted one for their immediate need. We used them to carry the packs and equipment of men who were sick, but not sick enough to ride; it was the brutal truth that many men got better more quickly if they were kept moving; and the mere reprieve from carrying one's pack was almost enough in itself to effect a cure.

Horses were also useful for intercommunication between columns. Some extremely gallant actions were performed by mounted men on different occasions. In February 1943, a young officer from the Burma Rifles by the name of Toye, rode forty miles through hostile country from Tonmakeng to Myene to bring Wingate news of Japanese movements. The following month one of my own Corporals, (McGee) undertook a hazardous ride on my call, in the aid of several wounded men whom I had to leave in a local village outside Bonchaung.

As No. 5 Column were preparing to cross the Chindwin River in mid-February, Animal Transport Officer, Lt. Bill Smyly recalled the excellent performance of his beloved charger, who he had named, Sambo:

The Chindwin was crossed without much difficulty, for we took two ropes across at night and ferried over the river, hand over hand, in Royal Engineer boats, like huge inner tubes with a canvas floor, or rafts supported by the tiny RAF boats, which float but are not much use for anything else. The mules and horses which were fit, swam across in droves, the fearful ones going across tied to our RE boats and the willing ones going over in droves of 15 to 20 at a time.

I was the last across, because the animals were my property, but, after a long and gloriously happy day, working in naked in the baking sun, I dispatched my saddle and clothes with the Groom, tied up my reins to a surcingle and rode across on Sambo’s back. He was a beautiful prancing gelding of 16 hands and a half, and was one of the finest, strongest beasts I have ever seen. He swam with his head held high and the water surged round his flanks, swirled round my legs and his long tail trailed out in his wake. We caught up and passed an RE boat and seemed to be going twice as fast.

Sadly, Bill's horse did not survive Operation Longcloth, in fact to my knowledge none of the horses or ponies taken into Burma that year ever returned to India.

Another Animal Transport Officer on Operation Longcloth was, Lt. Dominic Neill of No. 8 Column. He remembered his Section Sergeant and his own beloved charger, Red Wagon in an unpublished memoir recounting his adventures on the first Wingate expedition:

Sgt. Ormandy's knowledge of horses if not mules was complete. In the coming months he was to be of the greatest assistance to me, as he taught me so much about caring for both horses and mules, I was much in his debt during those days. He helped me with my own charger Red Wagon' a beautiful dark chestnut stallion with a white blaze across his forehead. Our commander, Major Scott of the King's Regiment had ordered Ormandy and I to ride up and down the column lines during these early marches, in order to check on the progress and behaviour of the mules, it was during these moments that I learned much about my horse. My Syce (Groom), 67892 Dalbir Thapa, who had come to us from the 6th Gurkhas, had become devoted to his charge and had re-christened him 'Rate', as he said his coat was the colour of a Nepalese Barking Deer. And so he became Rate to us both from that moment on.

In the end, as the expedition began to unravel, No. 8 Column broke up into small dispersal parties at the Irrawaddy in mid-April 1943. Column Commander, Major Scott ordered that all remaining mules and horses be turned loose at this point. With tears in his eyes, Dominic Neill attempted to leave his horse with a group of mules in a jungle clearing. For many hours, Rate continued to follow his master, and was never fully out of sight for most of the next day. Eventually, for one reason or another he stopped following the Chindit party and disappeared into the jungle, never to be seen again.

The Mules (True heroes of the Chindit campaigns).

The men became passionately fond of their mules: not only the muleteers, but the whole platoon who owned them. I have seen men weeping at a mule's death who have not wept at a comrade's.

Bernard Fergusson from his book, Wild Green Earth.

The mules for Operation Longcloth did not arrive at the Chindit training camps until the latter months of 1942. They were made up of three different types of animal: the small Indian bred brown mule, which would carry smaller loads on the expedition, the much larger example from Argentina and finally the largest of all from Missouri in the United States. The last two types were used to carry the very heavy equipment into Burma, items such as the column wireless and battery charger and 3" mortars.

Many of the Column Animal Transport officers were sent to a place called Guna in the Central Provinces of India, to meet, train with and finally take possession of the mule cadre. The man in charge of basic mule training and handling, was Captain Roy McKenzie, a Gurkha Rifles officer from Ontario in Canada.

McKenzie was responsible for training all the Column ATO's in the handling and care of their animals and would himself serve as the Animal Transport Officer for No. 3 Column on Operation Longcloth. Here is a quote from the book Canadians and the Burma Campaign, 1941-45, by Robert Farquharson which gives a fair idea of McKenzie and the type of man he was:

On the first Wingate expedition, McKenzie's first task was to get the mules over the River Chindwin. Mules are good swimmers once persuaded to enter the water. 'Mac' got his mules into the river, but on reaching midstream, they all suddenly turned and headed back to the shore they knew. Eventually, with patience, persistence and some little profanity, he got the mules across. Once all his charges, 80 mules and 20 horses were over, 'Mac' himself crossed elegantly astride his own charger.

Captain McKenzie adored his animals and became extremely attached to them during those few months behind enemy lines in Burma. Although he could not bear to see the mules suffering as the privations of the expedition began to hit home, he was unable to put the creatures out of their misery himself and often passed this sad duty on to his fellow officers. Denis Gudgeon, also of No. 3 Column, told me during our discussions in 2008 that:

He (McKenzie) simply loved his mules and could never shoot a sick animal, even when he knew it was the right thing to do, it was heartbreaking to see 'Mac' march away, head bowed, after he had lost one of his mules.

Mike Calvert reminisced about one of his favourite mules, in his book Fighting Mad:

The total number of men in the first Chindit raid was about 3,000 and with us we had about 1,100 mules. During training Wingate continually stressed the importance of these tough little animals until, in the end, we really did like them and trust them; they, in turn, became our willing helpers and rarely showed their well-known stubbornness.

Apart from their main job of carrying supplies, the mules were always useful as stand-by rations if other food became short. This, of course, was a last resort but there were several occasions when it was a question of the mules or us, and we had to harden our hearts. There was, however, one exceptional mule called Mabel. It is difficult to recall just how she differed from other mules, but there was that certain something about her. I have noticed the same thing in other animals, even domestic pets. Some dogs are just dogs and that's it, others have an indefinable streak of character that sets them apart, makes them a personality, and this is often recognisable even at a first glance. The same thing goes for humans, of course.

Wingate had that inner fire and sense of mission which made him different from other people. Mabel had a soft look in her eyes which just as surely made her different from other mules. So, hungry as we all were towards the end of our stay behind the Jap lines, no one would have thought of eating Mabel. Our morale was high, even though our bellies were empty, but it would have soon slumped if Mabel had been destroyed for food. We all knew that and she became even more essential to us, a real mascot, and we took her all the way back to India.

The men became passionately fond of their mules: not only the muleteers, but the whole platoon who owned them. I have seen men weeping at a mule's death who have not wept at a comrade's.

Bernard Fergusson from his book, Wild Green Earth.

The mules for Operation Longcloth did not arrive at the Chindit training camps until the latter months of 1942. They were made up of three different types of animal: the small Indian bred brown mule, which would carry smaller loads on the expedition, the much larger example from Argentina and finally the largest of all from Missouri in the United States. The last two types were used to carry the very heavy equipment into Burma, items such as the column wireless and battery charger and 3" mortars.

Many of the Column Animal Transport officers were sent to a place called Guna in the Central Provinces of India, to meet, train with and finally take possession of the mule cadre. The man in charge of basic mule training and handling, was Captain Roy McKenzie, a Gurkha Rifles officer from Ontario in Canada.

McKenzie was responsible for training all the Column ATO's in the handling and care of their animals and would himself serve as the Animal Transport Officer for No. 3 Column on Operation Longcloth. Here is a quote from the book Canadians and the Burma Campaign, 1941-45, by Robert Farquharson which gives a fair idea of McKenzie and the type of man he was:

On the first Wingate expedition, McKenzie's first task was to get the mules over the River Chindwin. Mules are good swimmers once persuaded to enter the water. 'Mac' got his mules into the river, but on reaching midstream, they all suddenly turned and headed back to the shore they knew. Eventually, with patience, persistence and some little profanity, he got the mules across. Once all his charges, 80 mules and 20 horses were over, 'Mac' himself crossed elegantly astride his own charger.

Captain McKenzie adored his animals and became extremely attached to them during those few months behind enemy lines in Burma. Although he could not bear to see the mules suffering as the privations of the expedition began to hit home, he was unable to put the creatures out of their misery himself and often passed this sad duty on to his fellow officers. Denis Gudgeon, also of No. 3 Column, told me during our discussions in 2008 that:

He (McKenzie) simply loved his mules and could never shoot a sick animal, even when he knew it was the right thing to do, it was heartbreaking to see 'Mac' march away, head bowed, after he had lost one of his mules.

Mike Calvert reminisced about one of his favourite mules, in his book Fighting Mad:

The total number of men in the first Chindit raid was about 3,000 and with us we had about 1,100 mules. During training Wingate continually stressed the importance of these tough little animals until, in the end, we really did like them and trust them; they, in turn, became our willing helpers and rarely showed their well-known stubbornness.

Apart from their main job of carrying supplies, the mules were always useful as stand-by rations if other food became short. This, of course, was a last resort but there were several occasions when it was a question of the mules or us, and we had to harden our hearts. There was, however, one exceptional mule called Mabel. It is difficult to recall just how she differed from other mules, but there was that certain something about her. I have noticed the same thing in other animals, even domestic pets. Some dogs are just dogs and that's it, others have an indefinable streak of character that sets them apart, makes them a personality, and this is often recognisable even at a first glance. The same thing goes for humans, of course.

Wingate had that inner fire and sense of mission which made him different from other people. Mabel had a soft look in her eyes which just as surely made her different from other mules. So, hungry as we all were towards the end of our stay behind the Jap lines, no one would have thought of eating Mabel. Our morale was high, even though our bellies were empty, but it would have soon slumped if Mabel had been destroyed for food. We all knew that and she became even more essential to us, a real mascot, and we took her all the way back to India.

Pte. Fred Holloman of Brigade Head Quarter's lovingly remembered his mule, Betty:

As part of my duties in transportation, I was posted to Brigade Head Quarters and began a twelve week course in mule handling. At first I disliked this new role working with these stubborn and sometimes aggressive animals, but in time I grew to respect and admire them. Most of the mules were first class animals previously used by the Royal Signals. My own mule was called Betty, and had the cross-flagged branding of the Royal Signals on her withers. We soon learned to know what the other was thinking and Betty used to nibble my backside when ever I groomed her and she sulked for days after being branded for a second time with her Chindit operational number.

Betty's job on Operation Longcloth was to carry the wireless set for Brigade HQ, an extraordinarily important role indeed. The set weighed approximately 60 pounds, which included not only the wireless set, but two very heavy charging batteries. Brigade HQ was made up of around 250 personnel, including a platoon of Commandos, Signallers, a Gurkha Defence platoon and an RAF section who were responsible for arranging and directing supply drops. I remember having to be available at all times, in case the wireless was needed to call in to Rear Base for supplies or contacting another column in the field.

Lt. Dominic Neill was the Animal Transport Officer for No. 8 Column on the first Chindit expedition in 1943. Although he served in a column consisting mainly of British troops, his muleteers were all Gurkhas from the 10th Princess Mary's Own Gurkha Rifles. He recalled:

Our mules had become personalities and friends to my muleteers and we all suffered with them, as only a master can for his animal. One should not have favourites I suppose, but I did have one such mule; she was No. 850. She was a beautiful pale dun coloured, country-bred animal and larger than most of the Indian mules. I called her 'Blondie' and she carried the bedding for Column HQ and was led by Rifleman Harkabahadur Rai. She faired better than most during the operation, but in the end, just as we were about to re-cross the Irrawaddy we were ordered to let our mules and chargers go and drive them away from our ranks. This moment broke all of our hearts.

Sir Robert Thompson was a prolific writer on the subject of counter terrorism and insurgency across SE Asia since the end of WW2. His efforts during the two Wingate expeditions involved his skills as an RAF liaison officer, tasked to bring in the vital air supply drops that would keep the Chindits fed and watered as they marched through the Burmese jungle. Thompson was teamed on both occasions with Mike Calvert and the Chindit columns of 77 Brigade, he was often given the responsibility in leading large sections of men, not just in his role as Air Liaison, but also in aggressive actions against the enemy.

From his book, Make for the Hills, published in 1989:

My first job in 1942, detailed by Wingate as a result of my being able to ride horses, was to train and fit out thirty mountain artillery mules, all reportedly from Missouri in the United States, to carry our wireless sets, charging engines and fuel. These mules were far bigger than the Indian-bred mules which carried all the other Army equipment.

All the mule-leaders for these animals were British and we had a lot of fun working up and I certainly became a great admirer of my mules. My mule-leaders were Privates Hall, Wilkinson and Pratt of the 13th King's. The mules were called Yankee, Daisy and the third's name for some reason I cannot remember, perhaps because we eventually ate it. As every farmer knows, it is much better that meals remain anonymous.

In 1943 at the conclusion of Operation Longcloth, Thompson was given the job of leading one of the small dispersal groups of around 30-35 men. His previous experience in evading the Japanese when he walked out of Hong Kong via China in 1941, ensured that he and his group were the first party from No. 3 Column to return safely to India. Alongside him when re-crossing the Chindwin River, were his RAF Sergeant, George Morris, Ptes. Hall, Wilkinson and Pratt and Yankee the mule.

To read more about Yankee, please click on following link and scroll alphabetically down the page: Roll Call U-Z

Sadly, very few mules were able to survive Operation Longcloth, with Mabel and Yankee of No. 3 Column being the only two known to have made the long journey back to India in April 1943. Most of these animals collapsed through exhaustion in the middle weeks of the expedition, or perished from either starvation as supply drops began to dry up, or from the dreaded disease, anthrax. As mentioned by Dominic Neill, once dispersal had been called on Operation Longcloth and the heavy weaponry and wireless sets had been jettisoned, many of the mules and horses were simply let go to fend for themselves in the jungle.

Pte. John Bromley of No. 8 Column and Jack.

Pte. John Bromley of No. 8 Column and Jack.

The Dogs (Always a man's best friend).

From the pages of Wild Green Earth, written by Bernard Fergusson:

One more animal completed our menagerie on Operation Longcloth—our dog. Two months before the 1943 Expedition started, during a conference at Brigade Headquarters, Orde Wingate told every column commander to produce two men for training with Army dogs at Debra Dun. I remember the occasion well, because it produced from an officer of one of the Gurkha columns, who must have spoken without thinking, the odd remark that he didn't suppose it was any good sending Gurkhas, as the dogs presumably only understood English. I chipped in gravely to say that I didn't suppose the dogs had a very extensive vocabulary, and that in the course of two months it should be possible to train up the Gurkhas to the same linguistic standard as the dogs: which went down terribly badly with the Gurkha officers.

In due course the men went. I sent Anders and Cummings; and they came back at Christmas time with Judy, a Staffordshire bull-terrier bitch. She carried round her neck a leather satchel of the same pattern (to my amateur eye) as cavalry officers wear on their cross-belts. She was trained to run between two men. Say, for instance, that I was sending out John Kerr's platoon (as I did at Tonmakeng) on detachment, and wanted Judy to run between us: Anders would go with John, taking Judy with him, while Cummings would remain with me.

Once in position, Anders would send Judy away: she would run to Cummings where she had last seen him, at my Headquarters. Then, if Cummings sent her away, she would run back to Anders. We used her several times, working from outposts back to Column Headquarters, and she was extremely good. Nobody except Anders and Cummings, her two masters, was allowed to speak to her, feed her, pat her or take any notice of her. In the end, both her masters were killed or reported missing, and thereafter she shed her professional status and became a mascot.

She got out to India in due course with one of my dispersal groups (Denny Sharp), was embezzled by an officer, and was last heard of serving with him somewhere on the North-West Frontier. She is entitled to the 1939-45 Medal and the Burma Star, and I trust that she has been duly invested with both.

On the Scottish National War Memorial in Edinburgh Castle, not only the men and the women, but the animals are remembered, from the horses and mules of the gunners and the R.A.S.C. to the mice used by the tunnellers to test the air. That is right and proper. So do we remember the animals that shared our wanderings with us, and most of all the mules. They could not have shown more spirit or devotion, more pride in their endurance, if they had known and rejoiced in the cause in which they were working. Some are dead, some are still serving, some, no doubt, retired. May the living have good masters in their lives, and may their loads sit lightly and balanced on their willing backs; and may the dead enjoy good grazing and frequent supply-drops in the Elysian pastures.

From the pages of Wild Green Earth, written by Bernard Fergusson:

One more animal completed our menagerie on Operation Longcloth—our dog. Two months before the 1943 Expedition started, during a conference at Brigade Headquarters, Orde Wingate told every column commander to produce two men for training with Army dogs at Debra Dun. I remember the occasion well, because it produced from an officer of one of the Gurkha columns, who must have spoken without thinking, the odd remark that he didn't suppose it was any good sending Gurkhas, as the dogs presumably only understood English. I chipped in gravely to say that I didn't suppose the dogs had a very extensive vocabulary, and that in the course of two months it should be possible to train up the Gurkhas to the same linguistic standard as the dogs: which went down terribly badly with the Gurkha officers.

In due course the men went. I sent Anders and Cummings; and they came back at Christmas time with Judy, a Staffordshire bull-terrier bitch. She carried round her neck a leather satchel of the same pattern (to my amateur eye) as cavalry officers wear on their cross-belts. She was trained to run between two men. Say, for instance, that I was sending out John Kerr's platoon (as I did at Tonmakeng) on detachment, and wanted Judy to run between us: Anders would go with John, taking Judy with him, while Cummings would remain with me.

Once in position, Anders would send Judy away: she would run to Cummings where she had last seen him, at my Headquarters. Then, if Cummings sent her away, she would run back to Anders. We used her several times, working from outposts back to Column Headquarters, and she was extremely good. Nobody except Anders and Cummings, her two masters, was allowed to speak to her, feed her, pat her or take any notice of her. In the end, both her masters were killed or reported missing, and thereafter she shed her professional status and became a mascot.

She got out to India in due course with one of my dispersal groups (Denny Sharp), was embezzled by an officer, and was last heard of serving with him somewhere on the North-West Frontier. She is entitled to the 1939-45 Medal and the Burma Star, and I trust that she has been duly invested with both.

On the Scottish National War Memorial in Edinburgh Castle, not only the men and the women, but the animals are remembered, from the horses and mules of the gunners and the R.A.S.C. to the mice used by the tunnellers to test the air. That is right and proper. So do we remember the animals that shared our wanderings with us, and most of all the mules. They could not have shown more spirit or devotion, more pride in their endurance, if they had known and rejoiced in the cause in which they were working. Some are dead, some are still serving, some, no doubt, retired. May the living have good masters in their lives, and may their loads sit lightly and balanced on their willing backs; and may the dead enjoy good grazing and frequent supply-drops in the Elysian pastures.

NB1. As mentioned by Bernard Fergusson, both his dog handlers on Operation Longcloth, Pte. 3779341 William Henry Anders and Pte. 5116413 Harold Victor Cummings failed to return to India after dispersal was called. William Anders was captured by the Japanese at the Shweli River on 1st April 1943 and died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 14th March 1944. Harold Cummings was lost somewhere on the Chinese Borders in late April 1943, having dispersed with Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood of No. 7 Column after 5 Column had been ambushed at Hintha village. I am pleased to confirm that Judy did make it back to India as part of the dispersal group led by Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp.

NB2: There was a moment however, around the 3rd April 1943, when Judy might not have made it back in one piece. From the pages of Beyond the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson remembers:

On the morning of the 3rd April we left our bivouac at about 6am. We were all feeling very weak with hunger and I made a feeble joke about eating Judy the dog, quite prepared to be taken seriously. I received a mixture of answers, but most in the group were horrified highlighting the suggestion as cannibalistic.

Other dogs from Operation Longcloth that have come to my attention are:

1. Border-Collie cross, Jack, the Company Head Quarters mascot and message dog that went on to serve with Brigade Head Quarters during 1943.

2. Another animal named Judy, this time a Labrador cross served with No. 8 Column in Burma. Her two handlers were Pte. Tommy Atkins from Platoon No. 17, who was partially deaf and relied heavily on his beloved Judy for guidance in the jungle and Pte. John Gardiner, who was listed as having been captured by the Japanese in May 1943 and held at Rangoon Central Jail for the rest of war. No records exist to confirm Gardiner's POW status and neither man features on any casualty listings for Operation Longcloth and therefore, it must be presumed that both men survived the war. Sadly, the eventual fate of Judy is not known, but of all the animals taken into Burma on the first Chindit expedition, I would imagine the messenger dogs had the best chance of survival or finding themselves a new home.

Seen below is a photograph of Flight Lieutenant Denis Sharp's dispersal party, safely across the Chindwin River in late April 1943. Sitting in the centre of the front row and being petted by Sgt. Ronald Rothwell, is No. 5 Column's message dog, Judy.

NB2: There was a moment however, around the 3rd April 1943, when Judy might not have made it back in one piece. From the pages of Beyond the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson remembers:

On the morning of the 3rd April we left our bivouac at about 6am. We were all feeling very weak with hunger and I made a feeble joke about eating Judy the dog, quite prepared to be taken seriously. I received a mixture of answers, but most in the group were horrified highlighting the suggestion as cannibalistic.

Other dogs from Operation Longcloth that have come to my attention are:

1. Border-Collie cross, Jack, the Company Head Quarters mascot and message dog that went on to serve with Brigade Head Quarters during 1943.

2. Another animal named Judy, this time a Labrador cross served with No. 8 Column in Burma. Her two handlers were Pte. Tommy Atkins from Platoon No. 17, who was partially deaf and relied heavily on his beloved Judy for guidance in the jungle and Pte. John Gardiner, who was listed as having been captured by the Japanese in May 1943 and held at Rangoon Central Jail for the rest of war. No records exist to confirm Gardiner's POW status and neither man features on any casualty listings for Operation Longcloth and therefore, it must be presumed that both men survived the war. Sadly, the eventual fate of Judy is not known, but of all the animals taken into Burma on the first Chindit expedition, I would imagine the messenger dogs had the best chance of survival or finding themselves a new home.

Seen below is a photograph of Flight Lieutenant Denis Sharp's dispersal party, safely across the Chindwin River in late April 1943. Sitting in the centre of the front row and being petted by Sgt. Ronald Rothwell, is No. 5 Column's message dog, Judy.

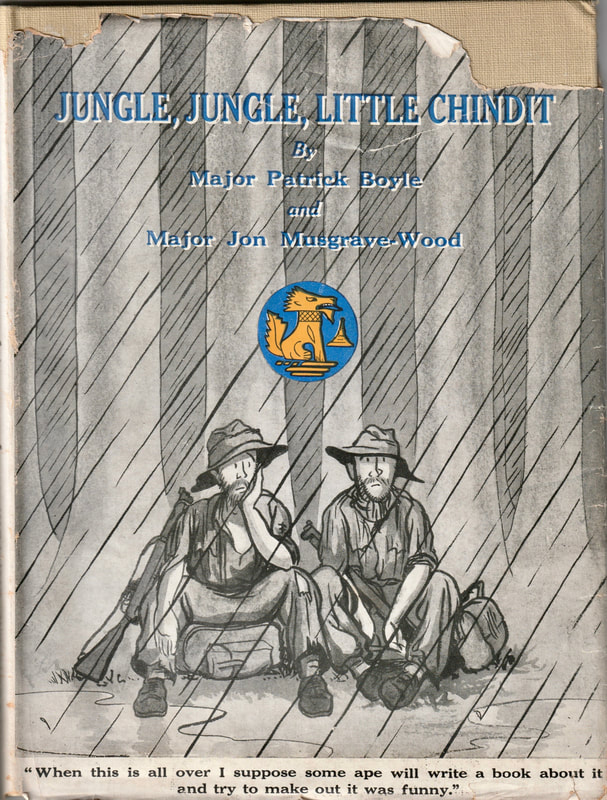

At sometime shortly after the conclusion of the second Chindit expedition, Operation Thursday in 1944, the book Jungle, Jungle, Little Chindit was compiled and published. The two authors, Major Patrick Boyle and Major Jon Musgrave-Wood had both served as Chindits, with Musgrave-Wood taking part on both Wingate operations. The book is a humorous account of what it was like to be a Chindit, with the added value of hilariously funny illustrations drawn by Musgrave-Wood, who went on to enjoy an illustrious career as cartoonist Emmwood, a regular contributor to periodicals such as Punch, Tatler & Bystander and the Daily Mail.

Chapter Four of the book is devoted to the animals used during the Chindit operations and is also entitled Chindits With Four Legs. I thought it would be apt to conclude this web page by adding the images of this chapter below. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Chapter Four of the book is devoted to the animals used during the Chindit operations and is also entitled Chindits With Four Legs. I thought it would be apt to conclude this web page by adding the images of this chapter below. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, May 2019.