The Raising of 142 Commando

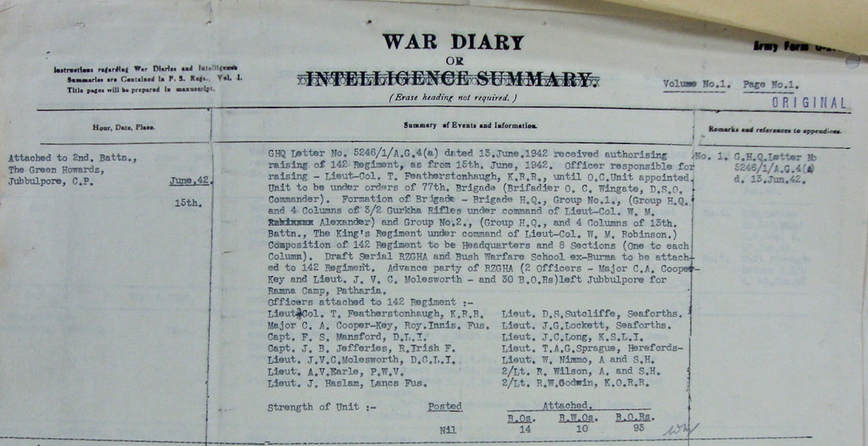

In every Chindit column there was a platoon of Commandos, known affectionately amongst their Chindit comrades as the Bangs and Flashes Brigade (quote Denis Gudgeon, March 2008). These men were given the overall working title of 142 Company R.I.A.S.C., this of course was merely a cover name for the more clandestine nature of their activities. 142 Commando was raised in mid-June 1942 and attached for a short while to the 2nd Battalion of the Green Howard's at Jubbulpore in the Central Provinces of India. Commanded in the first instance by Lieutenant-Colonel Timothy Featherstonehaugh of the King’s Royal Rifles, the group became part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in June 1942 and were handed over to Brigadier Wingate at the Ramna Camp in Patharia.

Under the draft recognition serial, RZGHA, men were gathered together to make up the strength of the newly formed Chindit Commando unit. At first it was bolstered by men mainly from the 6th and 8th Commando Regiments, who had arrived in India during the middle months of 1942; many of these men had served in the European and Middle Eastern theatres and had already taken part in several operations against the Axis alliance. On July 13th 1942, command of 142 Commando was given over to Major Mike Calvert of the Royal Engineers. The unit was then supplemented by soldiers from the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo and survivors from the 204 Chinese Military Mission. Both these former units had experience in Special Forces operations behind enemy lines and had only recently exited Burma or in the case of the 204 Mission, the Yunnan Provinces of China.

The structure of each Chindit Commando platoon was as follows:

1 Commanding Officer, usually a Lieutenant promoted to Acting/Captain.

1 2nd Lieutenant

1 Sergeant

1 Corporal

2 Lance Corporals

1 Sapper from the Royal Engineers

12-14 Privates

Under the draft recognition serial, RZGHA, men were gathered together to make up the strength of the newly formed Chindit Commando unit. At first it was bolstered by men mainly from the 6th and 8th Commando Regiments, who had arrived in India during the middle months of 1942; many of these men had served in the European and Middle Eastern theatres and had already taken part in several operations against the Axis alliance. On July 13th 1942, command of 142 Commando was given over to Major Mike Calvert of the Royal Engineers. The unit was then supplemented by soldiers from the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo and survivors from the 204 Chinese Military Mission. Both these former units had experience in Special Forces operations behind enemy lines and had only recently exited Burma or in the case of the 204 Mission, the Yunnan Provinces of China.

The structure of each Chindit Commando platoon was as follows:

1 Commanding Officer, usually a Lieutenant promoted to Acting/Captain.

1 2nd Lieutenant

1 Sergeant

1 Corporal

2 Lance Corporals

1 Sapper from the Royal Engineers

12-14 Privates

The men comprising 142 Commando had been drawn from all theatres of WW2. Most of the officers mentioned on the page featured above, had previously served in Europe and the Middle East with the more regular commando regiments. To read more about some these men, please click on any of the following links:

Lieutenant John Lindsay Watson

Major John B. Jefferies

Lieutenant James Vernon Crispin Molesworth

Albert Vivian Earle

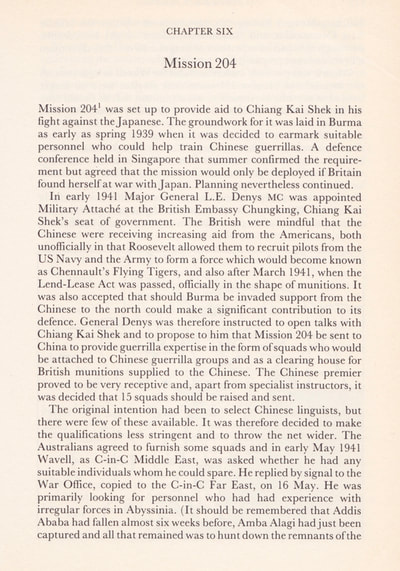

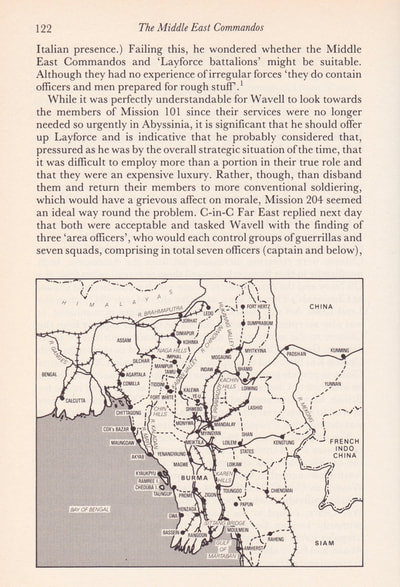

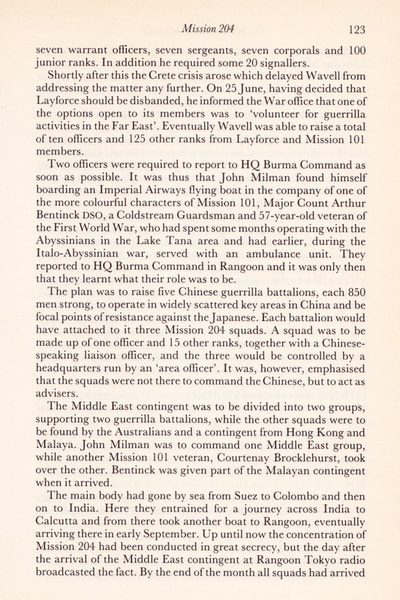

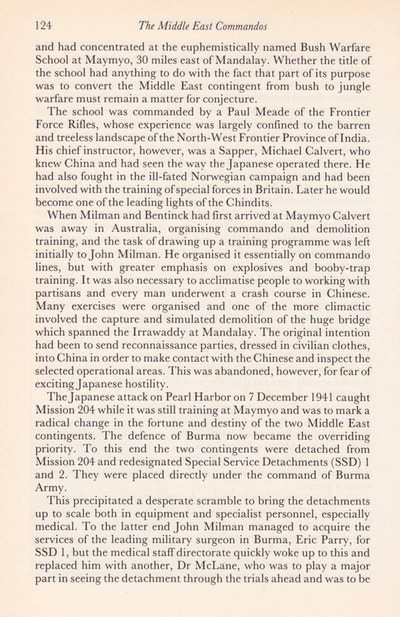

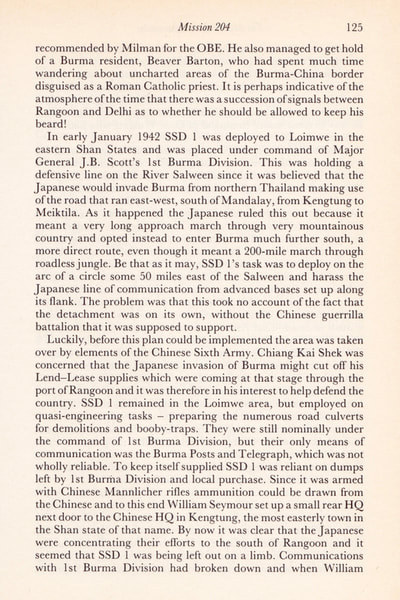

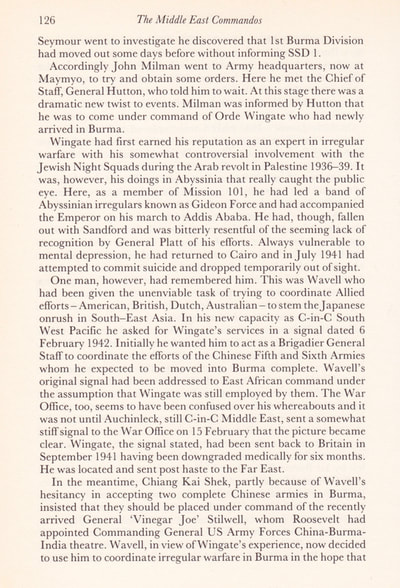

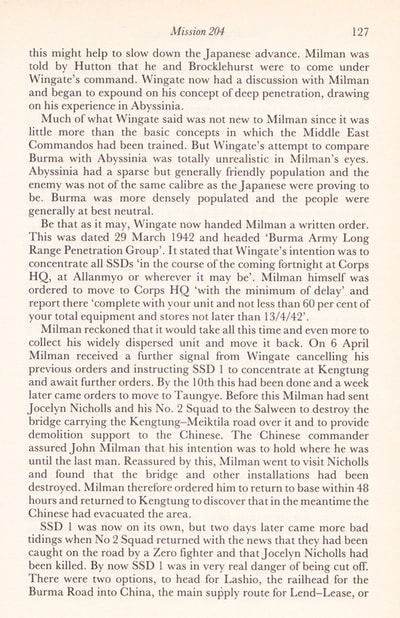

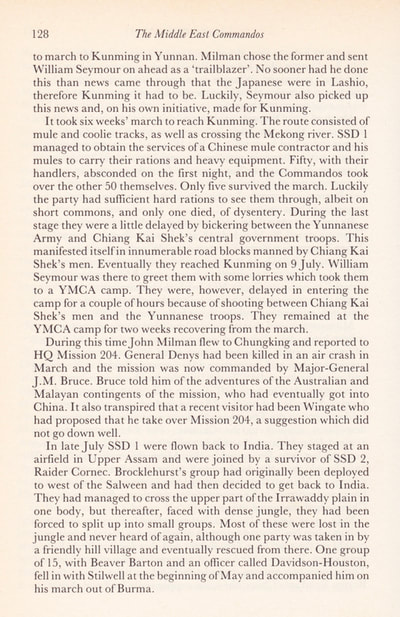

To learn more about the history of the Middle East commandos and their direct link to the Indian and Chinese theatres in 1942, please click on the images below. These pages are taken from the book, The Middle East Commnados, by Charles Messenger. (Published by Kimber & Co. Ltd. 1988).

Lieutenant John Lindsay Watson

Major John B. Jefferies

Lieutenant James Vernon Crispin Molesworth

Albert Vivian Earle

To learn more about the history of the Middle East commandos and their direct link to the Indian and Chinese theatres in 1942, please click on the images below. These pages are taken from the book, The Middle East Commnados, by Charles Messenger. (Published by Kimber & Co. Ltd. 1988).

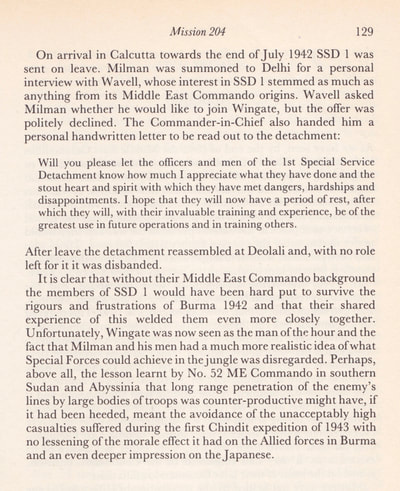

From the War diary (WO106/5012 at the National Archives) and in relation to the formation of the 204 Military Mission:

204 Military Mission, under Major L.E. Denys, consists of a guerrilla force designed and trained to operate alongside Chinese personnel in China. The organisation comprises: Main Headquarters, five area Headquarters, each with three squads or companies, making a total of fifteen companies in all. A reserve pool of some fifteen new squads is being formed. 204 Mission supply three officers, known as advisers and twenty-two NCO's and special personnel for each Company; the Chinese provide around 120 troops to each Company. The object will be to harass the Japanese lines of communication in China and to contain as many Japanese troops there as is possible.

The present position is that three battalions are currently training inside China, at the Chinese guerrilla school based at Chiyang and will be ready for operations by mid-March (1942) and a fourth battalion by April. The first three battalions will operate in areas 2 and 3 (see locations below). Preparations are also in hand for operations to commence in area No. 4. All operations in area No. 5 will be undertaken by S.O. (Special Operations) and area No. 1 will be left vacant until more squads are available.

The five operational areas are:

1. Ichang.

2&3. North of Changsha and Nanchang.

4. Chekiang.

5. Canton.

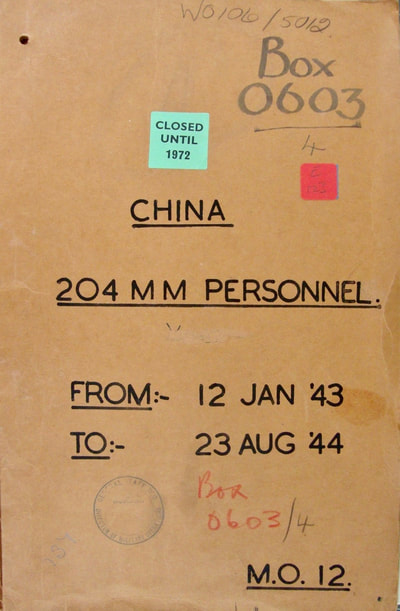

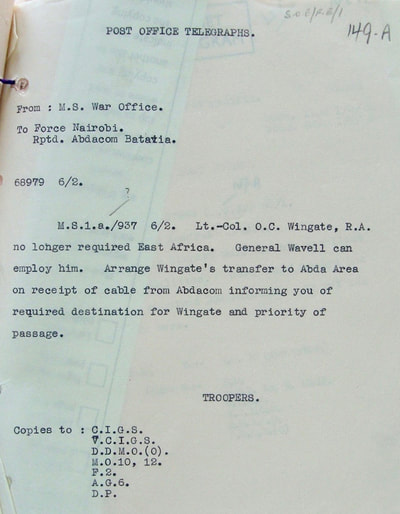

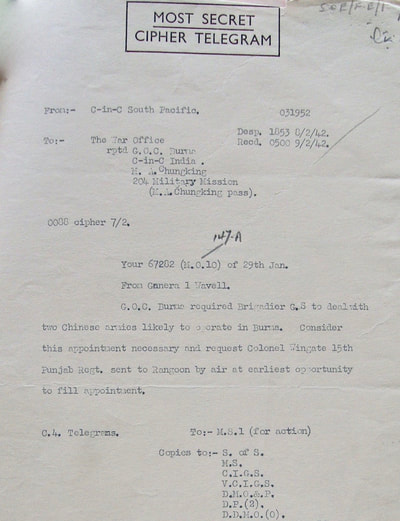

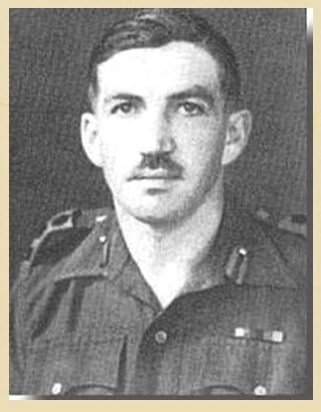

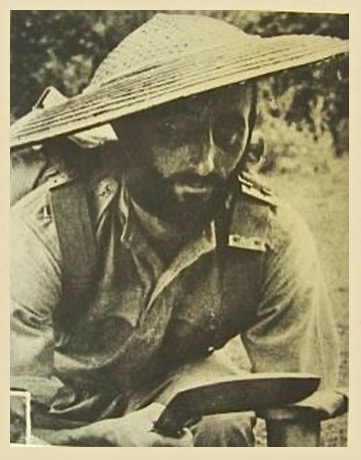

The next Gallery shows in chronological format, a sequence of letters to and from the War Office, India Command and General Wavell, in regards to the availability of the then Colonel O.C. Wingate and his possible involvement with 204 Military Mission/Bush Warfare School in Burma. It is probably true to say that his appointment was not universally welcomed by the hierarchies present in theatre at the time. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. Also shown are some of the personnel and officers mentioned so far in this narrative.

204 Military Mission, under Major L.E. Denys, consists of a guerrilla force designed and trained to operate alongside Chinese personnel in China. The organisation comprises: Main Headquarters, five area Headquarters, each with three squads or companies, making a total of fifteen companies in all. A reserve pool of some fifteen new squads is being formed. 204 Mission supply three officers, known as advisers and twenty-two NCO's and special personnel for each Company; the Chinese provide around 120 troops to each Company. The object will be to harass the Japanese lines of communication in China and to contain as many Japanese troops there as is possible.

The present position is that three battalions are currently training inside China, at the Chinese guerrilla school based at Chiyang and will be ready for operations by mid-March (1942) and a fourth battalion by April. The first three battalions will operate in areas 2 and 3 (see locations below). Preparations are also in hand for operations to commence in area No. 4. All operations in area No. 5 will be undertaken by S.O. (Special Operations) and area No. 1 will be left vacant until more squads are available.

The five operational areas are:

1. Ichang.

2&3. North of Changsha and Nanchang.

4. Chekiang.

5. Canton.

The next Gallery shows in chronological format, a sequence of letters to and from the War Office, India Command and General Wavell, in regards to the availability of the then Colonel O.C. Wingate and his possible involvement with 204 Military Mission/Bush Warfare School in Burma. It is probably true to say that his appointment was not universally welcomed by the hierarchies present in theatre at the time. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. Also shown are some of the personnel and officers mentioned so far in this narrative.

A quote from Mike Calvert's book, Fighting Mad:

"I stamped into my office and found that my visitor, a Brigadier, was sitting at my desk. Normally this would not have bothered me, but in my present weary and disgruntled mood it got under my skin.

Who are you? I said. He was quite calm and composed. Wingate, he replied. The name meant nothing to me, but this also did not seem to worry him.

Who are you? he asked in return. I was pretty filthy after the trip and it was a fair question. Calvert, I replied, and added: Excuse me, but that is my desk. He moved aside at once and let me sit down."

This was Mike Calvert's first meeting with Brigadier Wingate in spring 1942 at the Bush Warfare School and putting to one side the frosty nature of this first exchange, the pair quickly forged a very special relationship in the months leading up to the first Chindit expedition. Calvert had been running the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo over the recent past and had organised several raids into Burma during the Japanese advance, leading teams of miscellaneous troops in an attempt to disrupt the enemies lines of communication and progress across the country.

"I stamped into my office and found that my visitor, a Brigadier, was sitting at my desk. Normally this would not have bothered me, but in my present weary and disgruntled mood it got under my skin.

Who are you? I said. He was quite calm and composed. Wingate, he replied. The name meant nothing to me, but this also did not seem to worry him.

Who are you? he asked in return. I was pretty filthy after the trip and it was a fair question. Calvert, I replied, and added: Excuse me, but that is my desk. He moved aside at once and let me sit down."

This was Mike Calvert's first meeting with Brigadier Wingate in spring 1942 at the Bush Warfare School and putting to one side the frosty nature of this first exchange, the pair quickly forged a very special relationship in the months leading up to the first Chindit expedition. Calvert had been running the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo over the recent past and had organised several raids into Burma during the Japanese advance, leading teams of miscellaneous troops in an attempt to disrupt the enemies lines of communication and progress across the country.

Lt-Colonel Henry Courtney Brocklehurst.

Lt-Colonel Henry Courtney Brocklehurst.

Two other Special Forces units had also been operating inside Burma during this time, in the shape of SSD1 and SSD2 (Special Service Detachment), led by Lieutenant-Colonel John Alexander Ralph Milman and Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Courtney Brocklehurst respectively. Wingate had also touched upon these units during his time in Burma and once again first impressions had not been favourable.

Some notes in reference to Long Range Penetration, including mention of SSD1 and SSD2:

Long Range Penetration is a highly technical branch of warfare and its problems are peculiar to itself. It follows that it must be represented at its rear by appropriate staff officers who form part of the Head Quarters of any formation in the field. The officers who carry out this important work, should have at least some comprehension and previous experience of the special problems likely to occur in theatre.

At present the limited resources of 204 Mission are spread over a large focus area. This will destroy any chance of using our highly trained personnel in a war of penetration. They are being frittered away in odds and sods jobs with little focus or chance of success. The existing contingents are employed as follows:

1). Brocklehurst Contingent (SSD2). This unit has been allotted for employment under the 1st Burma Division. Already this unit has been employed in carrying out a raid into Thailand supported by a regular column. This is not the proper employment for forces of penetration. It is an example of tactical penetration or infiltration, which all regular forces should be capable of. These Contingents should be retained for the purposes for which they were created, that being, Long Range Penetration.

2). Millman Contingent (SSD1). The unit is doing nothing at present and its Commander is very anxious to be employed by the Chinese, where he feels he can build up an organisation of his own. If the very small forces we have available are allowed to disperse in this manner, we shall not be able to organise LRP going forward. This unit should be concentrated at once in the neighbourhood of Corps HQ.

3). Major Calvert, Commandant of the Bush Warfare School (Maymyo) and nearly all of his staff and instructors, have been despatched to operate under 17th Division, leaving the school, which still has an instructional function to perform, without the means to do so. It is therefore recommended that Calvert and his team return to the School as soon as possible. The instructors should be replaced in the near future with officers withdrawn from the above contingents, having gained great experience and know-how on their travels.

To read more about SSD1 and SSD2, please click on the following link to the Commando Veterans Association website:

gallery.commandoveterans.org/cdoGallery/v/WW2/Mission+204/

Some notes in reference to Long Range Penetration, including mention of SSD1 and SSD2:

Long Range Penetration is a highly technical branch of warfare and its problems are peculiar to itself. It follows that it must be represented at its rear by appropriate staff officers who form part of the Head Quarters of any formation in the field. The officers who carry out this important work, should have at least some comprehension and previous experience of the special problems likely to occur in theatre.

At present the limited resources of 204 Mission are spread over a large focus area. This will destroy any chance of using our highly trained personnel in a war of penetration. They are being frittered away in odds and sods jobs with little focus or chance of success. The existing contingents are employed as follows:

1). Brocklehurst Contingent (SSD2). This unit has been allotted for employment under the 1st Burma Division. Already this unit has been employed in carrying out a raid into Thailand supported by a regular column. This is not the proper employment for forces of penetration. It is an example of tactical penetration or infiltration, which all regular forces should be capable of. These Contingents should be retained for the purposes for which they were created, that being, Long Range Penetration.

2). Millman Contingent (SSD1). The unit is doing nothing at present and its Commander is very anxious to be employed by the Chinese, where he feels he can build up an organisation of his own. If the very small forces we have available are allowed to disperse in this manner, we shall not be able to organise LRP going forward. This unit should be concentrated at once in the neighbourhood of Corps HQ.

3). Major Calvert, Commandant of the Bush Warfare School (Maymyo) and nearly all of his staff and instructors, have been despatched to operate under 17th Division, leaving the school, which still has an instructional function to perform, without the means to do so. It is therefore recommended that Calvert and his team return to the School as soon as possible. The instructors should be replaced in the near future with officers withdrawn from the above contingents, having gained great experience and know-how on their travels.

To read more about SSD1 and SSD2, please click on the following link to the Commando Veterans Association website:

gallery.commandoveterans.org/cdoGallery/v/WW2/Mission+204/

Henry Courtney Brocklehurst pre-WW2.

Henry Courtney Brocklehurst pre-WW2.

Update 21/12/2019.

A quote illustrating the character of Henry Courtney Brocklehurst from the book, Helen of Burma, written by Helen Rodriguez the senior nurse at the main civilian hospital of Taunggyi (Shan State) during April 1942:

The next day Colonel Brocklehurst, who commanded Special Service Detachment 2 - a commando unit which had been trained at the secret Bush Warfare School under 'Mad Mike Calvert' and which specialised in the demolition of bridges, turned up at the hospital and warned me that they had been detailed to carry out an extensive programme of bridge-blowing as the Japs were quite close.

Their task was to delay the advance and thus give the retreating Army with its attendant mass of refugees as long a period of grace as possible. They had been operating quite near Taunggyi and had witnessed the horror of the first Japanese attacks. The Colonel, a tall, raw-boned man with a huge revolver strapped to his side, resembled a fictional hero from some schoolboy's adventure book. He spoke quietly with a well-bred, well-educated voice, but his tones could not disguise the tungsten strength beneath the almost nonchalant exterior. He was, I learned later, a nephew of Queen Mary, and had been big game hunting with the Duke of Windsor when he was Prince of Wales.

He had fought with Wingate in Abyssinia, and had a distinguished war record in the Middle East. He explained that time was running out for the handful of `last ditchers' who still remained in the town and soon the fuse would reach the powder keg. When his men had completed their demolition they would pull out, and he expected me to be with them. He made it sound more like an order than a request, and he was clearly a man who expected to be obeyed. I replied that, as we still had a little time, I would continue to attend to my patients, and would reconsider the situation when things got more difficult.

I could not bring myself to go through the Casablanca bit again — whether he thought me a heroine or a tiresome nuisance there would inevitably be arguments, and I had no energy to spare for such a diversion. Colonel Brocklehurst nodded curtly, as if he had no great objection to my ideas, and then added that, when and if their duties permitted, he would allocate me six men to assist in running the hospital. He was as good as his word, for the six, including a Sergeant, arrived the same day to say they had orders to help in whatever way they could, and that any instructions I issued would be obeyed.

NB. Colonel Brocklehurst died about ten weeks after his meeting with Helen Rodriguez at Taunggyi, when a raft he was aboard overturned on a fast flowing river somewhere in the Kachin Hills north of Bhamo. His body was never recovered and for this reason he is remembered upon Face 1 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

For more information about his life, please click on the following links:

longwaytotipperary.ul.ie/week-8/p41_17-2/

www.search.staffspasttrack.org.uk/Details.aspx?&ResourceID=28499&SearchType=3

A quote illustrating the character of Henry Courtney Brocklehurst from the book, Helen of Burma, written by Helen Rodriguez the senior nurse at the main civilian hospital of Taunggyi (Shan State) during April 1942:

The next day Colonel Brocklehurst, who commanded Special Service Detachment 2 - a commando unit which had been trained at the secret Bush Warfare School under 'Mad Mike Calvert' and which specialised in the demolition of bridges, turned up at the hospital and warned me that they had been detailed to carry out an extensive programme of bridge-blowing as the Japs were quite close.

Their task was to delay the advance and thus give the retreating Army with its attendant mass of refugees as long a period of grace as possible. They had been operating quite near Taunggyi and had witnessed the horror of the first Japanese attacks. The Colonel, a tall, raw-boned man with a huge revolver strapped to his side, resembled a fictional hero from some schoolboy's adventure book. He spoke quietly with a well-bred, well-educated voice, but his tones could not disguise the tungsten strength beneath the almost nonchalant exterior. He was, I learned later, a nephew of Queen Mary, and had been big game hunting with the Duke of Windsor when he was Prince of Wales.

He had fought with Wingate in Abyssinia, and had a distinguished war record in the Middle East. He explained that time was running out for the handful of `last ditchers' who still remained in the town and soon the fuse would reach the powder keg. When his men had completed their demolition they would pull out, and he expected me to be with them. He made it sound more like an order than a request, and he was clearly a man who expected to be obeyed. I replied that, as we still had a little time, I would continue to attend to my patients, and would reconsider the situation when things got more difficult.

I could not bring myself to go through the Casablanca bit again — whether he thought me a heroine or a tiresome nuisance there would inevitably be arguments, and I had no energy to spare for such a diversion. Colonel Brocklehurst nodded curtly, as if he had no great objection to my ideas, and then added that, when and if their duties permitted, he would allocate me six men to assist in running the hospital. He was as good as his word, for the six, including a Sergeant, arrived the same day to say they had orders to help in whatever way they could, and that any instructions I issued would be obeyed.

NB. Colonel Brocklehurst died about ten weeks after his meeting with Helen Rodriguez at Taunggyi, when a raft he was aboard overturned on a fast flowing river somewhere in the Kachin Hills north of Bhamo. His body was never recovered and for this reason he is remembered upon Face 1 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

For more information about his life, please click on the following links:

longwaytotipperary.ul.ie/week-8/p41_17-2/

www.search.staffspasttrack.org.uk/Details.aspx?&ResourceID=28499&SearchType=3

142 Commando and their role on Operation Longcloth

A quote from Bernard Fergusson, commander of Chindit Column No. 5 on Operation Longcloth:

I became more and more anxious to hurry to Bonchaung, and so I told Gerry (Roberts) to come on with men and animals as fast as he could, while I pushed on ahead with Peter Dorans. We got there just after five o'clock, to find everybody in position. David Whitehead, Corporal Pike, and various other sappers were sitting on the bridge with their legs swinging, working away like civvies.

I found Duncan Menzies, who told me that Jim Harman had had a bad time in the jungle, and had turned up at Bonchaung half an hour before, having got hopelessly bushed: he had now set off down the railway line towards the gorge. David hoped to have the bridge ready for blowing at half-past eight or nine; he had already laid a "hasty" demolition, which we could blow if interrupted. Until he was ready there was nothing whatever to be done, bar have a cup of tea. I had several.

Duncan had everybody ready to move at nine, mules loaded and all. David gave us five minutes warning, and told us that the big bang would be preceded by a little bang. The little bang duly went off, and there was a short delay; then ……..

The flash illumined the whole hillside. It showed the men standing tense and waiting, the muleteers with a good grip of their mules; and the brown of the path and the green of the trees preternaturally vivid. Then came the bang. The mules plunged and kicked, the hills for miles around rolled the noise of it about their hollows and flung it to their neighbours. Mike Calvert and John Fraser heard it away in their distant bivouacs; and all of us hoped that John Kerr and his little group of abandoned men, whose sacrifice had helped to make it possible, heard it also, and knew that we had accomplished that which we had come so far to do.

Four miles farther on we met Alec MacDonald's guides; and just as we were going into bivouac we heard another great explosion, and knew that Jim Harman had blown the gorge.

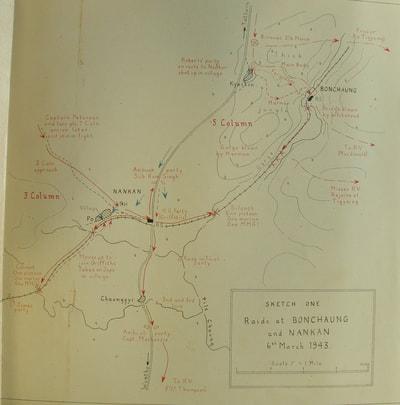

The demolitions at Bonchaung were one-half of the main objective for 142 Commando on Operation Longcloth. Responsibility for the other half belonged to 3 Column under the leadership of Major Calvert and involved applying similar destruction to the railway line slightly to the south of Bonchaung at a village called Nankan.

From the memoirs of Mike Calvert, dated 6th March 1943, the date of his 30th birthday:

I decided to drop off Corporal Day and one other man to blow a small girder bridge near our objective and left some others to blow the railway line in various places. After a very rapid march down 4 miles of line we finally found our bridge, which exceeded our expectation in size and in height. We encountered an ambush by several Japanese companies, but these were dealt with by our Gurkhas and two platoons from 7 Column led by Captain Petersen. Good work was done here by Harold James and Captain Griffiths of the Burma Rifles. The bridge was blown successfully and CSM Blain placed booby traps all along the track and abutments. It was now getting dark so I called for the column to withdraw; we were very pleased with ourselves and it had been a good birthday party for me.

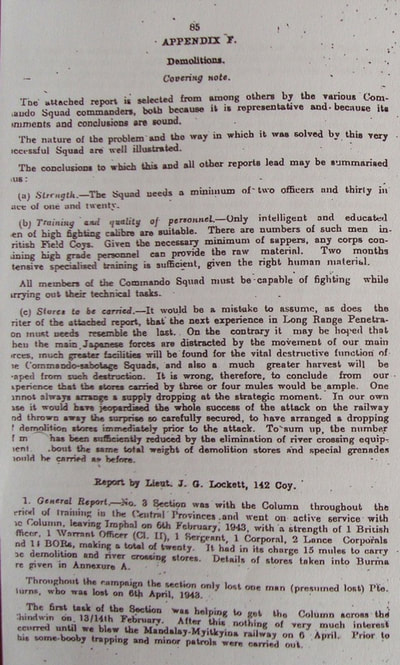

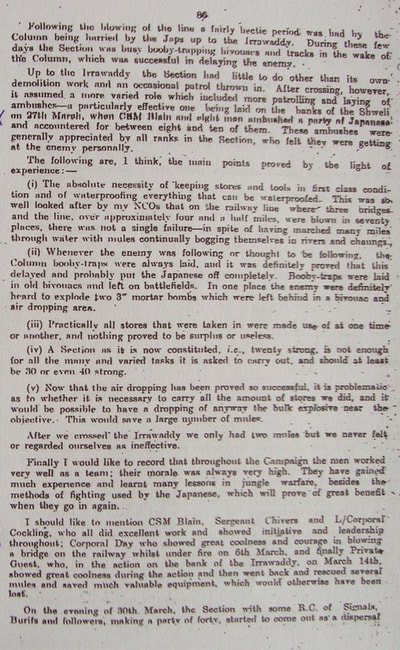

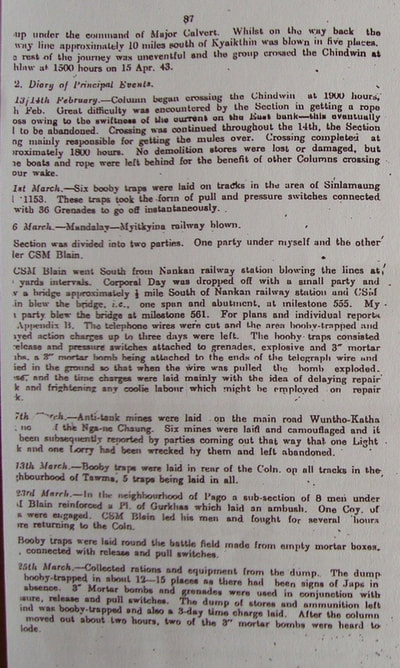

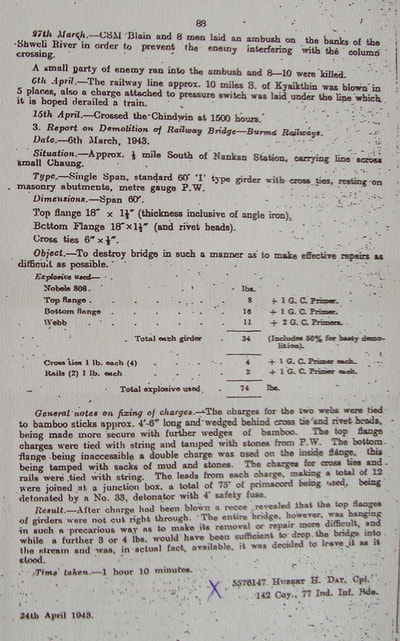

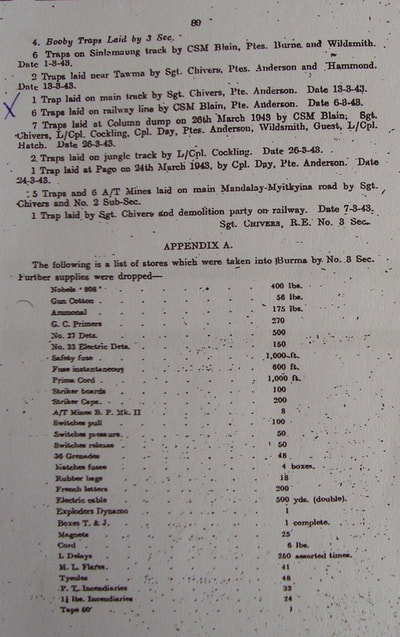

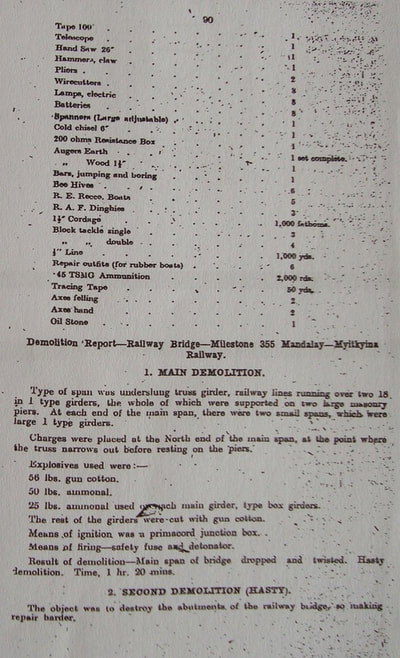

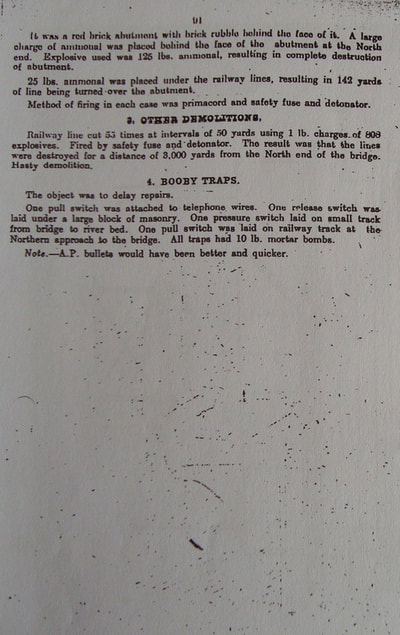

Shown in the Gallery below is a sketch map of the area around Bonchaung and Nankan and some pages from the official debrief document in relation to the first Wingate Expedition, outlining the performance of 142 Commando and the demolitions at Nankan. As you will read, demolitions were only one aspect of a commandos role during Operation Longcloth; other duties included sabotage, the laying of booby traps and leading the column in close quarter combat with the enemy. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

A quote from Bernard Fergusson, commander of Chindit Column No. 5 on Operation Longcloth:

I became more and more anxious to hurry to Bonchaung, and so I told Gerry (Roberts) to come on with men and animals as fast as he could, while I pushed on ahead with Peter Dorans. We got there just after five o'clock, to find everybody in position. David Whitehead, Corporal Pike, and various other sappers were sitting on the bridge with their legs swinging, working away like civvies.

I found Duncan Menzies, who told me that Jim Harman had had a bad time in the jungle, and had turned up at Bonchaung half an hour before, having got hopelessly bushed: he had now set off down the railway line towards the gorge. David hoped to have the bridge ready for blowing at half-past eight or nine; he had already laid a "hasty" demolition, which we could blow if interrupted. Until he was ready there was nothing whatever to be done, bar have a cup of tea. I had several.

Duncan had everybody ready to move at nine, mules loaded and all. David gave us five minutes warning, and told us that the big bang would be preceded by a little bang. The little bang duly went off, and there was a short delay; then ……..

The flash illumined the whole hillside. It showed the men standing tense and waiting, the muleteers with a good grip of their mules; and the brown of the path and the green of the trees preternaturally vivid. Then came the bang. The mules plunged and kicked, the hills for miles around rolled the noise of it about their hollows and flung it to their neighbours. Mike Calvert and John Fraser heard it away in their distant bivouacs; and all of us hoped that John Kerr and his little group of abandoned men, whose sacrifice had helped to make it possible, heard it also, and knew that we had accomplished that which we had come so far to do.

Four miles farther on we met Alec MacDonald's guides; and just as we were going into bivouac we heard another great explosion, and knew that Jim Harman had blown the gorge.

The demolitions at Bonchaung were one-half of the main objective for 142 Commando on Operation Longcloth. Responsibility for the other half belonged to 3 Column under the leadership of Major Calvert and involved applying similar destruction to the railway line slightly to the south of Bonchaung at a village called Nankan.

From the memoirs of Mike Calvert, dated 6th March 1943, the date of his 30th birthday:

I decided to drop off Corporal Day and one other man to blow a small girder bridge near our objective and left some others to blow the railway line in various places. After a very rapid march down 4 miles of line we finally found our bridge, which exceeded our expectation in size and in height. We encountered an ambush by several Japanese companies, but these were dealt with by our Gurkhas and two platoons from 7 Column led by Captain Petersen. Good work was done here by Harold James and Captain Griffiths of the Burma Rifles. The bridge was blown successfully and CSM Blain placed booby traps all along the track and abutments. It was now getting dark so I called for the column to withdraw; we were very pleased with ourselves and it had been a good birthday party for me.

Shown in the Gallery below is a sketch map of the area around Bonchaung and Nankan and some pages from the official debrief document in relation to the first Wingate Expedition, outlining the performance of 142 Commando and the demolitions at Nankan. As you will read, demolitions were only one aspect of a commandos role during Operation Longcloth; other duties included sabotage, the laying of booby traps and leading the column in close quarter combat with the enemy. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The performance of the commandos on Operation Longcloth was generally of high quality, mostly, but not exclusively, in their role in handling explosives and demolitions. The main concentration in books and debrief reports has fallen upon the men of 3 & 5 Columns, but other platoons did sterling work during their time in Burma. A good example would be the excellent work done by the commandos of 1 & 2 Columns, in not only destroying the railway line and bridge at Kyaikthin on the 2nd March 1943, but also extracting themselves successfully from the enemy ambush suffered immediately afterwards.

By their very nature, the men selected to form the Commando platoons were fitter and perhaps possessed a greater strength of character than the average infantryman on Operation Longcloth. This seems to have given those men from 142 Commando who were captured by the Japanese in 1943, a greater chance of surviving their time as a prisoner of war. Of the Commandos captured during the first Wingate expedition over 50% were liberated in May 1945. The overall figure for Chindit Other Ranks that became POW’s is much less at just 39%.

To read more about the men that made up 142 Commando, please click on any of the following links:

DLI Commandos

John William Brock

Pte. David Horne

Pte. Israel 'Jack' Medalie

Lance Corporal James Boyce

The Bricklayers of Column 4 Commando

'Young Ernie' Belcher

Jim Tomlinson Column 8 Commando

Lance Corporal Percy Finch

Pte. Daniel Burns

Ted Stuart, Almost, but not Quite

Lance Corporal Gerald Desmond

Sgt. Frank Ernest Pester

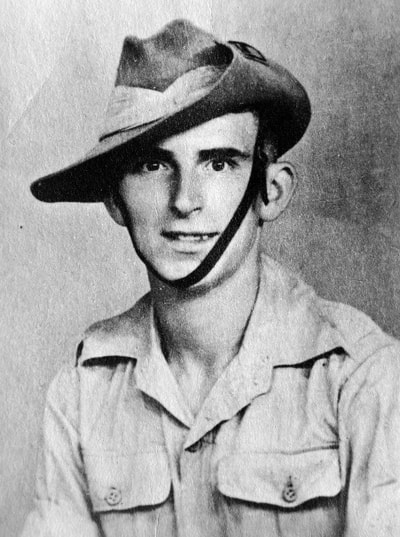

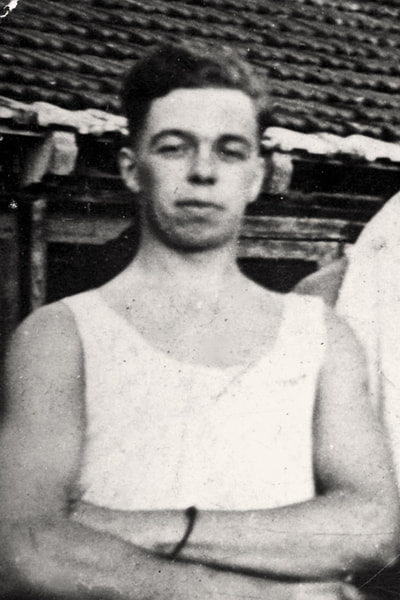

To conclude this story, seen below is a Gallery of photographs of some of the men who served as commandos on Operation Longcloth. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. This page is dedicated to the memory of Pte. Jack Whittingham, a member of No. 5 Column Commando in 1943.

From the book, Beyond the Chindwin by Bernard Fergusson:

On the 6th April I issued the last of our milk tablets and we marched off. We had eaten very little and were in a bad way. At half past eight we came to a fork in the track. John Fraser thought we should take the left track and I preferred the right. It turned out, but only by my hunch that we chose well, for the Japanese were marching along the track which we had spurned. But even more importantly, the track we were on led us to a chaung running through a paddy and there grazing peacefully were three water-buffalo.

This time I took no chance and sent Tommy Roberts and Peter Dorans, the two best shots in column to stalk the buffalos and all three fell dead. The shots seemed to awaken the world, but we cared not at all. Packs were dumped near the chaung and gangs of cutters-up were organised. Whittingham, of the commandos, was a butcher in civil life, and he took command of one buffalo, Tommy Roberts the second and the third was left in reserve. Fires had been lit, but our hunger was too savage and we gnawed at the raw flesh with horrid eagerness. From nine until five that day we cooked and ate almost without intermission, except that sometimes we would fall asleep and then wake and eat again.

By their very nature, the men selected to form the Commando platoons were fitter and perhaps possessed a greater strength of character than the average infantryman on Operation Longcloth. This seems to have given those men from 142 Commando who were captured by the Japanese in 1943, a greater chance of surviving their time as a prisoner of war. Of the Commandos captured during the first Wingate expedition over 50% were liberated in May 1945. The overall figure for Chindit Other Ranks that became POW’s is much less at just 39%.

To read more about the men that made up 142 Commando, please click on any of the following links:

DLI Commandos

John William Brock

Pte. David Horne

Pte. Israel 'Jack' Medalie

Lance Corporal James Boyce

The Bricklayers of Column 4 Commando

'Young Ernie' Belcher

Jim Tomlinson Column 8 Commando

Lance Corporal Percy Finch

Pte. Daniel Burns

Ted Stuart, Almost, but not Quite

Lance Corporal Gerald Desmond

Sgt. Frank Ernest Pester

To conclude this story, seen below is a Gallery of photographs of some of the men who served as commandos on Operation Longcloth. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. This page is dedicated to the memory of Pte. Jack Whittingham, a member of No. 5 Column Commando in 1943.

From the book, Beyond the Chindwin by Bernard Fergusson:

On the 6th April I issued the last of our milk tablets and we marched off. We had eaten very little and were in a bad way. At half past eight we came to a fork in the track. John Fraser thought we should take the left track and I preferred the right. It turned out, but only by my hunch that we chose well, for the Japanese were marching along the track which we had spurned. But even more importantly, the track we were on led us to a chaung running through a paddy and there grazing peacefully were three water-buffalo.

This time I took no chance and sent Tommy Roberts and Peter Dorans, the two best shots in column to stalk the buffalos and all three fell dead. The shots seemed to awaken the world, but we cared not at all. Packs were dumped near the chaung and gangs of cutters-up were organised. Whittingham, of the commandos, was a butcher in civil life, and he took command of one buffalo, Tommy Roberts the second and the third was left in reserve. Fires had been lit, but our hunger was too savage and we gnawed at the raw flesh with horrid eagerness. From nine until five that day we cooked and ate almost without intermission, except that sometimes we would fall asleep and then wake and eat again.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, August 2017.